Constantinian Walls on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Walls of Constantinople ( el, Τείχη της Κωνσταντινουπόλεως) are a series of defensive stone walls that have surrounded and protected the city of

The Walls of Constantinople ( el, Τείχη της Κωνσταντινουπόλεως) are a series of defensive stone walls that have surrounded and protected the city of

75.10–14

, the city held out against Severan forces for three years, until 196, with its inhabitants resorting even to throwing bronze statues at the besiegers when they ran out of other projectiles. Severus punished the city harshly: the strong walls were demolished and the city was deprived of its civic status, being reduced to a mere village dependent on

The double Theodosian Walls ( el, τεῖχος Θεοδοσιακόν, ''teichos Theodosiakon''), located about 2 km to the west of the old Constantinian Wall, were erected during the reign of Emperor

The double Theodosian Walls ( el, τεῖχος Θεοδοσιακόν, ''teichos Theodosiakon''), located about 2 km to the west of the old Constantinian Wall, were erected during the reign of Emperor

The Theodosian Walls consist of the main inner wall (μέγα τεῖχος, ''mega teichos'', "great wall"), separated from the lower outer wall (, ''exō teichos'' or μικρὸν τεῖχος, ''mikron teichos'', "small wall") by a terrace, the ''peribolos'' (περίβολος). Between the outer wall and the moat (, ''souda'') there stretched an outer terrace, the ''parateichion'' (), while a low breastwork crowned the moat's eastern escarpment. Access to both terraces was possible through

The Theodosian Walls consist of the main inner wall (μέγα τεῖχος, ''mega teichos'', "great wall"), separated from the lower outer wall (, ''exō teichos'' or μικρὸν τεῖχος, ''mikron teichos'', "small wall") by a terrace, the ''peribolos'' (περίβολος). Between the outer wall and the moat (, ''souda'') there stretched an outer terrace, the ''parateichion'' (), while a low breastwork crowned the moat's eastern escarpment. Access to both terraces was possible through  The outer wall was 2 m thick at its base, and featured arched chambers on the level of the ''peribolos'', crowned with a battlemented walkway, reaching a height of 8.5–9 m. Access to the outer wall from the city was provided either through the main gates or through small

The outer wall was 2 m thick at its base, and featured arched chambers on the level of the ''peribolos'', crowned with a battlemented walkway, reaching a height of 8.5–9 m. Access to the outer wall from the city was provided either through the main gates or through small

Following the walls from south to north, the Golden Gate ( el, Χρυσεία Πύλη, links=no, ''Chryseia Pylē''; la, Porta Aurea, links=no; tr, Altınkapı or Yaldızlıkapı, links=no), is the first gate to be encountered. It was the main ceremonial entrance into the capital, used especially for the occasions of a

Following the walls from south to north, the Golden Gate ( el, Χρυσεία Πύλη, links=no, ''Chryseia Pylē''; la, Porta Aurea, links=no; tr, Altınkapı or Yaldızlıkapı, links=no), is the first gate to be encountered. It was the main ceremonial entrance into the capital, used especially for the occasions of a  The gate, built of large square blocks of polished white

The gate, built of large square blocks of polished white  The main gate itself was covered by an outer wall, pierced by a single gate, which in later centuries was flanked by an ensemble of reused marble reliefs. According to descriptions of

The main gate itself was covered by an outer wall, pierced by a single gate, which in later centuries was flanked by an ensemble of reused marble reliefs. According to descriptions of

After his

After his

The Xylokerkos or Xerokerkos Gate (), now known as the

The Xylokerkos or Xerokerkos Gate (), now known as the

The Gate of the Spring or Pēgē Gate ( in Greek) was named after a popular monastery outside the Walls, the '' Zōodochos Pēgē'' ("

The Gate of the Spring or Pēgē Gate ( in Greek) was named after a popular monastery outside the Walls, the '' Zōodochos Pēgē'' ("

The Gate of Char ius (), named after the nearby early Byzantine monastery founded by a ''

The Gate of Char ius (), named after the nearby early Byzantine monastery founded by a ''

The Walls of Blachernae connect the

The Walls of Blachernae connect the

The seaward walls ( el, τείχη παράλια, links=no, ''teichē paralia'') enclosed the city on the sides of the Sea of Marmara (Propontis) and the gulf of the

The seaward walls ( el, τείχη παράλια, links=no, ''teichē paralia'') enclosed the city on the sides of the Sea of Marmara (Propontis) and the gulf of the  The Sea Walls were architecturally similar to the Theodosian Walls, but of simpler construction. They were formed by a single wall, considerably lower than the land walls, with inner circuits in the locations of the harbours. Enemy access to the walls facing the Golden Horn was prevented by the presence of a heavy chain or boom, installed by Emperor Leo III (r. 717–741), supported by floating barrels and stretching across the mouth of the inlet. One end of this chain was fastened to the Tower of Eugenius, in the modern suburb of

The Sea Walls were architecturally similar to the Theodosian Walls, but of simpler construction. They were formed by a single wall, considerably lower than the land walls, with inner circuits in the locations of the harbours. Enemy access to the walls facing the Golden Horn was prevented by the presence of a heavy chain or boom, installed by Emperor Leo III (r. 717–741), supported by floating barrels and stretching across the mouth of the inlet. One end of this chain was fastened to the Tower of Eugenius, in the modern suburb of  During the siege of the city by the Fourth Crusade, the sea walls nonetheless proved to be a weak point in the city's defences, as the Venetians managed to storm them. Following this experience,

During the siege of the city by the Fourth Crusade, the sea walls nonetheless proved to be a weak point in the city's defences, as the Venetians managed to storm them. Following this experience,

Further down the coast was the gate known in Turkish as ''Balat Kapı'' ("Palace Gate"), preceded in close order by three large archways, which served either as gates to the shore or to a harbour that serviced the imperial palace of Blachernae. Two gates are known to have existed in the vicinity in Byzantine times: the Kynegos Gate (, ''Pylē tou Kynēgou/tōn Kynēgōn'', "Gate of the Hunter(s)"), whence the quarter behind it was named ''Kynegion'', and the Gate of St. John the Forerunner and Baptist (, ''Porta tou hagiou Prodromou kai Baptistou''), though it is not clear whether the latter was distinct from the Kynegos Gate. The ''Balat Kapı'' has been variously identified as one of them, and as one of the three gates on the Golden Horn known as the Imperial Gate (, ''Pylē Basilikē'').

Further south was the Gate of the Phanarion (, ''Pylē tou Phanariou''), Turkish ''Fener Kapısı'', named after the local light-tower (''phanarion'' in Greek), which also gave its name to the local

Further down the coast was the gate known in Turkish as ''Balat Kapı'' ("Palace Gate"), preceded in close order by three large archways, which served either as gates to the shore or to a harbour that serviced the imperial palace of Blachernae. Two gates are known to have existed in the vicinity in Byzantine times: the Kynegos Gate (, ''Pylē tou Kynēgou/tōn Kynēgōn'', "Gate of the Hunter(s)"), whence the quarter behind it was named ''Kynegion'', and the Gate of St. John the Forerunner and Baptist (, ''Porta tou hagiou Prodromou kai Baptistou''), though it is not clear whether the latter was distinct from the Kynegos Gate. The ''Balat Kapı'' has been variously identified as one of them, and as one of the three gates on the Golden Horn known as the Imperial Gate (, ''Pylē Basilikē'').

Further south was the Gate of the Phanarion (, ''Pylē tou Phanariou''), Turkish ''Fener Kapısı'', named after the local light-tower (''phanarion'' in Greek), which also gave its name to the local

The wall of the Propontis was built almost at the shoreline, with the exception of harbours and quays, and had a height of 12–15 metres, with thirteen gates, and 188 towers. and a total length of almost 8,460 metres, with further 1,080 metres comprising the inner wall of the Vlanga harbour. Several sections of the wall were damaged during the construction of the ''

The wall of the Propontis was built almost at the shoreline, with the exception of harbours and quays, and had a height of 12–15 metres, with thirteen gates, and 188 towers. and a total length of almost 8,460 metres, with further 1,080 metres comprising the inner wall of the Vlanga harbour. Several sections of the wall were damaged during the construction of the ''

File:Istanbul Marble Tower 3473.jpg, Marble Tower to Right

File:Istanbul Marble Tower 3474.jpg, Marble Tower from South

File:Istanbul Marble Tower 3476.jpg, Marble Tower Connecting structure

File:Istanbul Marble Tower 3477.jpg, Marble Tower Connecting structure

File:Istanbul Marble Tower 3479.jpg, Marble Tower from Kennedy Caddesi

The first gate, now demolished, was the Eastern Gate (, ''Heōa Pylē'') or Gate of  Further south, at the point where the shore turns westwards, are two further gates, the ''Balıkhane Kapısı'' ("Gate of the Fish-House") and ''Ahırkapısı'' ("Stable Gate"). Their names derive from the buildings inside the Topkapı Palace they led to. Their Byzantine names are unknown. The next gate, on the southeastern corner of the city, was the gate of the imperial

Further south, at the point where the shore turns westwards, are two further gates, the ''Balıkhane Kapısı'' ("Gate of the Fish-House") and ''Ahırkapısı'' ("Stable Gate"). Their names derive from the buildings inside the Topkapı Palace they led to. Their Byzantine names are unknown. The next gate, on the southeastern corner of the city, was the gate of the imperial

Several fortifications were built at various periods in the vicinity of Constantinople, forming part of its defensive system. The first and greatest of these is the 56 km long Anastasian Wall (Gk. , ''teichos Anastasiakon'') or Long Wall (, ''makron teichos'', or , ''megalē Souda''), built in the mid-5th century as an outer defence to Constantinople, some 65 km westwards of the city. It was 3.30 m thick and over 5 m high, but its effectiveness was apparently limited, and it was abandoned at some time in the 7th century for want of resources to maintain and men to garrison it. For centuries thereafter, its materials were used in local buildings, but several parts, especially in the remoter central and northern sections, are still extant.

In addition, between the Anastasian Wall and the city itself, there were several small towns and fortresses like Selymbria, Region or the great suburb of ''Hebdomon'' ("Seventh", modern

Several fortifications were built at various periods in the vicinity of Constantinople, forming part of its defensive system. The first and greatest of these is the 56 km long Anastasian Wall (Gk. , ''teichos Anastasiakon'') or Long Wall (, ''makron teichos'', or , ''megalē Souda''), built in the mid-5th century as an outer defence to Constantinople, some 65 km westwards of the city. It was 3.30 m thick and over 5 m high, but its effectiveness was apparently limited, and it was abandoned at some time in the 7th century for want of resources to maintain and men to garrison it. For centuries thereafter, its materials were used in local buildings, but several parts, especially in the remoter central and northern sections, are still extant.

In addition, between the Anastasian Wall and the city itself, there were several small towns and fortresses like Selymbria, Region or the great suburb of ''Hebdomon'' ("Seventh", modern

Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism article on the city during the Byzantine period

After the Ottoman conquest, the walls were maintained until the 1870s, when most were demolished to facilitate the expansion of the city. Today only the Galata Tower, visible from most of historical Constantinople, remains intact, along with several smaller fragments.

The twin forts of

The twin forts of

Age of spirituality: late antique and early Christian art, third to seventh century

', no. 335, 1979,

3D reconstruction of the Theodosian Walls at the ''Byzantium 1200'' project

* ttp://www.byzantium1200.com/oldgate.html 3D reconstruction of the Old Golden Gate at the ''Byzantium 1200'' project

3D reconstruction of the Golden Gate at the ''Byzantium 1200'' project

Site of the Yedikule Fortress Museum

Cross-section of the Theodosian Walls

Diagram detailing the course of the Land Walls

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Walls Of Constantinople Buildings and structures completed in the 5th century Byzantine architecture in Istanbul

The Walls of Constantinople ( el, Τείχη της Κωνσταντινουπόλεως) are a series of defensive stone walls that have surrounded and protected the city of

The Walls of Constantinople ( el, Τείχη της Κωνσταντινουπόλεως) are a series of defensive stone walls that have surrounded and protected the city of Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

(today Istanbul

Istanbul ( , ; tr, İstanbul ), formerly known as Constantinople ( grc-gre, Κωνσταντινούπολις; la, Constantinopolis), is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, serving as the country's economic, ...

in Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

) since its founding as the new capital of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

by Constantine the Great

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to Constantine the Great and Christianity, convert to Christiani ...

. With numerous additions and modifications during their history, they were the last great fortification

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

system of antiquity, and one of the most complex and elaborate systems ever built.

Initially built by Constantine the Great, the walls surrounded the new city on all sides, protecting it against attack from both sea and land. As the city grew, the famous double line of the Theodosian Walls was built in the 5th century. Although the other sections of the walls were less elaborate, they were, when well-manned, almost impregnable for any medieval besieger. They saved the city, and the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

with it, during sieges by the Avar-Sassanian coalition, Arabs

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Wester ...

, Rus', and Bulgars

The Bulgars (also Bulghars, Bulgari, Bolgars, Bolghars, Bolgari, Proto-Bulgarians) were Turkic semi-nomadic warrior tribes that flourished in the Pontic–Caspian steppe and the Volga region during the 7th century. They became known as nomad ...

, among others. The advent of gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). ...

siege cannons rendered the fortifications vulnerable, but cannon technology was not sufficiently advanced to capture the city on its own, and the walls could be repaired between reloading. Ultimately, the city fell from the sheer weight of numbers of the Ottoman forces on 29 May 1453 after a two-month siege.

The walls were largely maintained intact during most of the Ottoman period until sections began to be dismantled in the 19th century, as the city outgrew its medieval boundaries. Despite lack of maintenance, many parts of the walls survived and are still standing today. A large-scale restoration program has been underway since the 1980s.

Land Walls

Walls of Greek and Roman Byzantium

According to tradition, the city was founded asByzantium

Byzantium () or Byzantion ( grc, Βυζάντιον) was an ancient Greek city in classical antiquity that became known as Constantinople in late antiquity and Istanbul today. The Greek name ''Byzantion'' and its Latinization ''Byzantium'' cont ...

by Greek colonists from Megara

Megara (; el, Μέγαρα, ) is a historic town and a municipality in West Attica, Greece. It lies in the northern section of the Isthmus of Corinth opposite the island of Salamis Island, Salamis, which belonged to Megara in archaic times, befo ...

, led by the eponymous Byzas

Byzas (Ancient Greek: Βύζας, ''Býzas'') was the legendary founder of Byzantium (Ancient Greek: Βυζάντιον, ''Byzántion''), the city later known as Constantinople and then Istanbul.

Background

The legendary history of the founding ...

, around 658 BC. At the time the city consisted of a small region around an acropolis

An acropolis was the settlement of an upper part of an ancient Greek city, especially a citadel, and frequently a hill with precipitous sides, mainly chosen for purposes of defense. The term is typically used to refer to the Acropolis of Athens, ...

located on the easternmost hill (corresponding to the modern site of the Topkapı Palace

The Topkapı Palace ( tr, Topkapı Sarayı; ota, طوپقپو سرايى, ṭopḳapu sarāyı, lit=cannon gate palace), or the Seraglio

A seraglio, serail, seray or saray (from fa, سرای, sarāy, palace, via Turkish and Italian) i ...

). According to the late Byzantine ''Patria of Constantinople The ''Patria'' of Constantinople ( el, Πάτρια Κωνσταντινουπόλεως), also regularly referred to by the Latin name ''Scriptores originum Constantinopolitarum'' ("writers on the origins of Constantinople"), are a Byzantine collec ...

'', ancient Byzantium was enclosed by a small wall which began on the northern edge of the acropolis, extended west to the Tower of Eugenios, then went south and west towards the Strategion and the Baths of Achilles

Bath may refer to:

* Bathing, immersion in a fluid

** Bathtub, a large open container for water, in which a person may wash their body

** Public bathing, a public place where people bathe

* Thermae, ancient Roman public bathing facilities

Plac ...

, continued south to the area known in Byzantine times as Chalkoprateia, and then turned, in the area of the Hagia Sophia

Hagia Sophia ( 'Holy Wisdom'; ; ; ), officially the Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque ( tr, Ayasofya-i Kebir Cami-i Şerifi), is a mosque and major cultural and historical site in Istanbul, Turkey. The cathedral was originally built as a Greek Ortho ...

, in a loop towards the northeast, crossed the regions known as Topoi and Arcadianae and reached the sea at the later quarter of Mangana. This wall was protected by 27 towers and had at least two landward gates, one which survived to become known as the Arch of Urbicius, and one where the Milion

The Milion ( grc-gre, Μίλιον or , ''Míllion''; tr, Milyon taşı) was a monument erected in the early 4th century AD in Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul, Turkey). It was the Byzantine zero-mile marker, the starting-place for the measu ...

monument was later located. On the seaward side, the wall was much lower. Although the author of the ''Patria'' asserts that this wall dated to the time of Byzas, the French researcher Raymond Janin

Raymond Janin, A.A. (31 August 1882 – 12 July 1972) was a French Byzantinist. An Assumptionist priest, he was also the author of several significant works on Byzantine studies

Byzantine studies is an interdisciplinary branch of the humanitie ...

thinks it more likely that it reflects the situation after the city was rebuilt by the Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referre ...

n general Pausanias Pausanias ( el, Παυσανίας) may refer to:

*Pausanias of Athens, lover of the poet Agathon and a character in Plato's ''Symposium''

*Pausanias the Regent, Spartan general and regent of the 5th century BC

* Pausanias of Sicily, physician of t ...

, who conquered the city in 479 BC. This wall is known to have been repaired, using tombstones, under the leadership of a certain Leo in 340 BC, against an attack by Philip II of Macedon

Philip II of Macedon ( grc-gre, Φίλιππος ; 382 – 21 October 336 BC) was the king ('' basileus'') of the ancient kingdom of Macedonia from 359 BC until his death in 336 BC. He was a member of the Argead dynasty, founders of the ...

.

Byzantium was relatively unimportant during the early Roman period. Contemporaries described it as wealthy, well peopled and well fortified, but this affluence came to an end due to its support for Pescennius Niger

Gaius Pescennius Niger (c. 135 – 194) was Roman Emperor from 193 to 194 during the Year of the Five Emperors. He claimed the imperial throne in response to the murder of Pertinax and the elevation of Didius Julianus, but was defeated by a riva ...

(r. 193–194) in his war against Septimius Severus

Lucius Septimius Severus (; 11 April 145 – 4 February 211) was Roman emperor from 193 to 211. He was born in Leptis Magna (present-day Al-Khums, Libya) in the Roman province of Africa (Roman province), Africa. As a young man he advanced thro ...

(r. 193–211). According to the account of Cassius Dio

Lucius Cassius Dio (), also known as Dio Cassius ( ), was a Roman historian and senator of maternal Greek origin. He published 80 volumes of the history on ancient Rome, beginning with the arrival of Aeneas in Italy. The volumes documented the ...

(''Roman History''75.10–14

, the city held out against Severan forces for three years, until 196, with its inhabitants resorting even to throwing bronze statues at the besiegers when they ran out of other projectiles. Severus punished the city harshly: the strong walls were demolished and the city was deprived of its civic status, being reduced to a mere village dependent on

Heraclea Perinthus

Perinthus or Perinthos ( grc, ἡ Πέρινθος) was a great and flourishing town of ancient Thrace, situated on the Propontis. According to John Tzetzes, it bore at an early period the name of Mygdonia (Μυγδονία). It lay 22 miles west ...

. However, appreciating the city's strategic importance, Severus eventually rebuilt it and endowed it with many monuments, including a Hippodrome

The hippodrome ( el, ἱππόδρομος) was an ancient Greek stadium for horse racing and chariot racing. The name is derived from the Greek words ''hippos'' (ἵππος; "horse") and ''dromos'' (δρόμος; "course"). The term is used i ...

and the Baths of Zeuxippus

The Baths of Zeuxippus were popular public baths in the city of Constantinople. They took their name because they were built on a site previously occupied by a temple of Zeus,Gilles, P. p. 70 on the earlier Greek Acropolis in Byzantion. Constructe ...

, as well as a new set of walls, located some 300–400 m to the west of the old ones. Little is known of the Severan Wall save for a short description of its course by Zosimus Zosimus, Zosimos, Zosima or Zosimas may refer to:

People

*

* Rufus and Zosimus (died 107), Christian saints

* Zosimus (martyr) (died 110), Christian martyr who was executed in Umbria, Italy

* Zosimos of Panopolis, also known as ''Zosimus Alchem ...

(''New History'', II.30.2–4) and that its main gate was located at the end of a portico

A portico is a porch leading to the entrance of a building, or extended as a colonnade, with a roof structure over a walkway, supported by columns or enclosed by walls. This idea was widely used in ancient Greece and has influenced many cult ...

ed avenue (the first part of the later '' Mese'') and shortly before the entrance of the later Forum of Constantine

The Forum of Constantine ( el, Φόρος Κωνσταντίνου, Fóros Konstantínou; la, Forum Constantini) was built at the foundation of Constantinople immediately outside the old city walls of Byzantium. It marked the centre of the new c ...

. The wall seems to have extended from near the modern Galata Bridge

The Galata Bridge ( tr, Galata Köprüsü, ) is a bridge that spans the Golden Horn in Istanbul, Turkey. From the end of the 19th century in particular, the bridge has featured in Turkish literature, theater, poetry and novels. The current Galata ...

in the Eminönü

Eminönü is a predominantly commercial waterfront area of Istanbul within the Fatih district near the confluence of the Golden Horn with the southern entrance of the Bosphorus strait and the Sea of Marmara. It is connected to Karaköy (historic G ...

quarter south through the vicinity of the Nuruosmaniye Mosque

The Nuruosmaniye Mosque ( tr, Nuruosmaniye Camii) is an 18th-century Ottoman mosque located in the Çemberlitaş neighbourhood of Fatih district in Istanbul, Turkey. In 2016 it was inscribed in the Tentative list of World Heritage Sites in Turke ...

to curve around the southern wall of the Hippodrome, and then going northeast to meet the old walls near the Bosporus. The ''Patria'' also mention the existence of another wall during the siege of Byzantium by Constantine the Great

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to Constantine the Great and Christianity, convert to Christiani ...

(r. 306–337) during the latter's conflict with Licinius

Valerius Licinianus Licinius (c. 265 – 325) was Roman emperor from 308 to 324. For most of his reign he was the colleague and rival of Constantine I, with whom he co-authored the Edict of Milan, AD 313, that granted official toleration to C ...

(r. 308–324), in 324. The text mentions that a fore-wall ('' proteichisma'') ran near the Philadephion, located at about the middle of the later, Constantinian city, suggesting the expansion of the city beyond the Severan Wall by this time.

Constantinian Walls

Like Severus before him, Constantine began to punish the city for siding with his defeated rival, but soon he too realized the advantages of Byzantium's location. During 324–336 the city was thoroughly rebuilt and inaugurated on 11 May 330 under the name of “New Rome” or “Second Rome”. Eventually, the city would most commonly be referred to as Constantinople, the "City of Constantine", in dedication to its founder (Gk. Κωνσταντινούπολις, ''Konstantinoupolis''). New Rome was protected by a new wall about 2.8 km (15 ''stadia

Stadia may refer to:

* One of the plurals of stadium, along with "stadiums"

* The plural of stadion, an ancient Greek unit of distance, which equals to 600 Greek feet (''podes'').

* Stadia (Caria), a town of ancient Caria, now in Turkey

* Stadi ...

'') west of the Severan wall. Constantine's fortification consisted of a single wall, reinforced with towers at regular distances, which began to be constructed in 324 and was completed under his son Constantius II

Constantius II (Latin: ''Flavius Julius Constantius''; grc-gre, Κωνστάντιος; 7 August 317 – 3 November 361) was Roman emperor from 337 to 361. His reign saw constant warfare on the borders against the Sasanian Empire and Germani ...

(r. 337–361). Only the approximate course of the wall is known: it began at the Church of St. Anthony at the Golden Horn, near the modern Atatürk Bridge

Atatürk Bridge ( tr, Atatürk Köprüsü) is a road bridge across the Golden Horn in Istanbul, Turkey. It is named after Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder and first President of the Republic of Turkey but is sometimes called the Unkapanı Bridg ...

, ran southwest and then southwards, passed east of the great open cisterns of Mocius and of Aspar, and ended near the Church of the Theotokos

''Theotokos'' (Greek: ) is a title of Mary, mother of Jesus, used especially in Eastern Christianity. The usual Latin translations are ''Dei Genitrix'' or ''Deipara'' (approximately "parent (fem.) of God"). Familiar English translations are " ...

of the Rhabdos on the Propontis coast, somewhere between the later sea gates of St. Aemilianus and Psamathos.

Already by the early 5th century, Constantinople had expanded outside the Constantinian Wall in the extramural area known as the ''Exokionion'' or ''Exakionion Exakionion ( gr, Ἑξακιώνιον) or Exokionion () was an area in Byzantine Empire, Byzantine Constantinople. Its exact location and extent vary considerably in the sources.

Name

The name is given in various forms (Ἑξακιώνιον, Ἑ� ...

''. The wall survived during much of the Byzantine period, even though it was replaced by the Theodosian Walls as the city's primary defense. An ambiguous passage refers to extensive damage to the city's "inner wall" from an earthquake on 25 September 478, which likely refers to the Constantinian wall. When repairs were being undertaken, to prevent an invasion by Atilla

Attila (, ; ), frequently called Attila the Hun, was the ruler of the Huns from 434 until his death in March 453. He was also the leader of a tribal empire consisting of Huns, Ostrogoths, Alans, and Bulgars, among others, in Central and ...

, the Blues and Greens, the supporters of chariot-racing teams, supplied 16,000 men between them for the building effort.

Theophanes the Confessor

Theophanes the Confessor ( el, Θεοφάνης Ὁμολογητής; c. 758/760 – 12 March 817/818) was a member of the Byzantine aristocracy who became a monk and chronicler. He served in the court of Emperor Leo IV the Khazar before taking u ...

reports renewed earthquake damage in 557. It appears that large parts survived relatively intact until the 9th century: the 11th-century historian Kedrenos

George Kedrenos, Cedrenus or Cedrinos ( el, Γεώργιος Κεδρηνός, fl. 11th century) was a Byzantine Greek historian. In the 1050s he compiled ''Synopsis historion'' (also known as ''A concise history of the world''), which spanned the ...

records that the "wall at Exokionion", likely a portion of the Constantinian wall, collapsed in an earthquake in 867. Only traces of the wall appear to have survived in later ages, although Van Millingen states that some parts survived in the region of the ''İsakapı'' until the early 19th century. The recent construction of Yenikapı Transfer Center

Yenikapı Transfer Center ( tr, Yenikapı Aktarma Merkezi), referred to as Yenikapı, is an underground transportation complex in Istanbul. It is located in south-central Fatih in the neighborhood of Yenikapı, hence the name of the hub. The co ...

has unearthed a section of the foundation of the wall of Constantine.

Gates

The names of a number of gates of the Constantinian Wall survive, but scholars debate their identity and exact location. The Old Golden Gate ( la, Porta Aurea, links=no, grc, Χρυσεία Πύλη, links=no), known also as the Xerolophos Gate and the Gate of Saturninus, is mentioned in the ''Notitia Urbis Constantinopolitanae

The ''Notitia Urbis Constantinopolitanae'' is an ancient "regionary", i.e., a list of monuments, public buildings and civil officials in Constantinople during the mid-5th century (between 425 and the 440s), during the reign of the emperor Theodosi ...

'', which further states that the city wall itself in the region around it was "ornately decorated". The gate stood somewhere on the southern slopes of the Seventh Hill. Its construction is often attributed to Constantine, but is in fact of uncertain age. It survived until the 14th century, when the Byzantine scholar Manuel Chrysoloras

Manuel (or Emmanuel) Chrysoloras ( el, Μανουὴλ Χρυσολωρᾶς; c. 1350 – 15 April 1415) was a Byzantine Greek classical scholar, humanist, philosopher, professor, and translator of ancient Greek texts during the Renaissance. Se ...

described it as being built of "wide marble blocks with a lofty opening", and crowned by a kind of stoa

A stoa (; plural, stoas,"stoa", ''Oxford English Dictionary'', 2nd Ed., 1989 stoai, or stoae ), in ancient Greek architecture, is a covered walkway or portico, commonly for public use. Early stoas were open at the entrance with columns, usually ...

. In late Byzantine times, a painting of the Crucifixion

Crucifixion is a method of capital punishment in which the victim is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross or beam and left to hang until eventual death from exhaustion and asphyxiation. It was used as a punishment by the Persians, Carthagin ...

was allegedly placed on the gate, leading to its later Ottoman name, ''İsakapı'' ("Gate of Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

"). It was destroyed by an earthquake in 1509, but its approximate location is known through the presence of the nearby '' İsakapı Mescidi'' mosque.

The identity and location of the Gate of At los (, ''Porta At lou'') are unclear. Cyril Mango identifies it with the Old Golden Gate; van Millingen places it on the Seventh Hill, at a height probably corresponding to one of the later gates of the Theodosian Wall in that area; and Raymond Janin places it further north, across the Lycus and near the point where the river passed under the wall. In earlier centuries, it was decorated with many statues, including one of Constantine, which fell down in an earthquake in 740.

The only gate whose location is known with certainty, aside from the Old Golden Gate, is the Gate of Saint Aemilianus (, ''Porta tou hagiou Aimilianou''), named in Turkish ''Davutpaşa Kapısı''. It lay at the juncture with the sea walls

A seawall (or sea wall) is a form of Coastal management, coastal defense constructed where the sea, and associated coastal processes, impact directly upon the landforms of the coast. The purpose of a seawall is to protect areas of human habit ...

, and served the communication with the coast. According to the ''Chronicon Paschale

''Chronicon Paschale'' (the ''Paschal'' or ''Easter Chronicle''), also called ''Chronicum Alexandrinum'', ''Constantinopolitanum'' or ''Fasti Siculi'', is the conventional name of a 7th-century Greek Christian chronicle of the world. Its name com ...

'', the Church of St Mary of Rhabdos, where the rod of Moses

Moses hbo, מֹשֶׁה, Mōše; also known as Moshe or Moshe Rabbeinu (Mishnaic Hebrew: מֹשֶׁה רַבֵּינוּ, ); syr, ܡܘܫܐ, Mūše; ar, موسى, Mūsā; grc, Mωϋσῆς, Mōÿsēs () is considered the most important pro ...

was kept, stood next to the gate.

The Old Gate of the Prodromos (, ''Palaia Porta tou Prodromou''), named after the nearby Church of St John the Baptist (called ''Prodromos'', "the Forerunner", in Greek), is another unclear case. Van Millingen identifies it with the Old Golden Gate, while Janin considers it to have been located on the northern slope of the Seventh Hill.

The last known gate is the Gate of Melantias (, ''Porta tēs Melantiados''), whose location is also debated. Van Millingen considered it to be a gate of the Theodosian Wall (the Pege Gate), while more recently, Janin and Mango have rebutted this, suggesting that it was located on the Constantinian Wall. While Mango identifies it with the Gate of the Prodromos, Janin considers the name to have been a corruption of the ''ta Meltiadou'' quarter, and places the gate to the west of the Mocius cistern. Other authors identified it with the Gate of Adrianople (A. M. Schneider) or with the Gate of Rhesios (A. J. Mordtmann).

Theodosian Walls

Theodosius II

Theodosius II ( grc-gre, Θεοδόσιος, Theodosios; 10 April 401 – 28 July 450) was Roman emperor for most of his life, proclaimed ''Augustus (title), augustus'' as an infant in 402 and ruling as the eastern Empire's sole emperor after ...

(r. 402–450), after whom they were named. The work was carried out in two phases, with the first phase erected during Theodosius' minority under the direction of Anthemius

Procopius Anthemius (died 11 July 472) was western Roman emperor from 467 to 472.

Perhaps the last capable Western Roman Emperor, Anthemius attempted to solve the two primary military challenges facing the remains of the Western Roman Empire: ...

, the praetorian prefect of the East

The praetorian prefecture of the East, or of the Orient ( la, praefectura praetorio Orientis, el, ἐπαρχότης/ὑπαρχία τῶν πραιτωρίων τῆς ἀνατολῆς) was one of four large praetorian prefectures into whic ...

, and was finished in 413 according to a law in the ''Codex Theodosianus

The ''Codex Theodosianus'' (Eng. Theodosian Code) was a compilation of the laws of the Roman Empire under the Christian emperors since 312. A commission was established by Emperor Theodosius II and his co-emperor Valentinian III on 26 March 429 a ...

''. An inscription discovered in 1993 however records that the work lasted for nine years, indicating that construction had already begun ca. 404/405, in the reign of Emperor Arcadius

Arcadius ( grc-gre, Ἀρκάδιος ; 377 – 1 May 408) was Roman emperor from 383 to 408. He was the eldest son of the ''Augustus'' Theodosius I () and his first wife Aelia Flaccilla, and the brother of Honorius (). Arcadius ruled the ea ...

(r. 383–408). This initial construction consisted of a single curtain wall with towers, which now forms the inner circuit of the Theodosian Walls.

Both the Constantinian and the original Theodosian walls were severely damaged in two earthquakes, on 25 September 437 and 6 November 447. The latter was especially powerful, and destroyed large parts of the wall, including 57 towers. Subsequent earthquakes, including another major one in January 448, compounded the damage. Theodosius II ordered the praetorian prefect Constantine

Constantine most often refers to:

* Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from 306 to 337, also known as Constantine I

*Constantine, Algeria, a city in Algeria

Constantine may also refer to:

People

* Constantine (name), a masculine given name ...

to supervise the repairs, made all the more urgent as the city was threatened by the presence of Attila the Hun

Attila (, ; ), frequently called Attila the Hun, was the ruler of the Huns from 434 until his death in March 453. He was also the leader of a tribal empire consisting of Huns, Ostrogoths, Alans, and Bulgars, among others, in Central and Ea ...

in the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

. Employing the city's "Circus

A circus is a company of performers who put on diverse entertainment shows that may include clowns, acrobats, trained animals, trapeze acts, musicians, dancers, hoopers, tightrope walkers, jugglers, magicians, ventriloquists, and unicyclist ...

factions" in the work, the walls were restored in a record 60 days, according to the Byzantine chroniclers and three inscriptions found ''in situ''.; ; It is at this date that the majority of scholars believe the second, outer wall to have been added, as well as a wide moat

A moat is a deep, broad ditch, either dry or filled with water, that is dug and surrounds a castle, fortification, building or town, historically to provide it with a preliminary line of defence. In some places moats evolved into more extensive ...

opened in front of the walls, but the validity of this interpretation is questionable; the outer wall was possibly an integral part of the original fortification concept.

Throughout their history, the walls were damaged by earthquakes and floods of the Lycus river

Lycus (Lykos, Lycos ,) may refer to:

Mythology

* Lycus (mythology), the name of numerous people in Greek mythology, including

** Lycus (brother of Nycteus), a ruler of the ancient city of Ancient Thebes

** Lycus (descendant of Lycus), son of Lyc ...

. Repairs were undertaken on numerous occasions, as testified by the numerous inscriptions commemorating the emperors or their servants who undertook to restore them. The responsibility for these repairs rested on an official variously known as the Domestic of the Walls or the Count of the Walls (, ''Domestikos/Komēs tōn teicheōn''), who employed the services of the city's populace in this task. After the Latin conquest of 1204, the walls fell increasingly into disrepair, and the revived post-1261 Byzantine state lacked the resources to maintain them, except in times of direct threat.

Course and topography

In their present state, the Theodosian Walls stretch for about 5.7 km from south to north, from the "Marble Tower" ( tr, Mermer Kule), also known as the "Tower ofBasil

Basil (, ; ''Ocimum basilicum'' , also called great basil, is a culinary herb of the family Lamiaceae (mints). It is a tender plant, and is used in cuisines worldwide. In Western cuisine, the generic term "basil" refers to the variety also kno ...

and Constantine

Constantine most often refers to:

* Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from 306 to 337, also known as Constantine I

*Constantine, Algeria, a city in Algeria

Constantine may also refer to:

People

* Constantine (name), a masculine given name ...

" (Gk. ''Pyrgos Basileiou kai Kōnstantinou'') on the Propontis

The Sea of Marmara,; grc, Προποντίς, Προποντίδα, Propontís, Propontída also known as the Marmara Sea, is an inland sea located entirely within the borders of Turkey. It connects the Black Sea to the Aegean Sea via the ...

coast to the area of the Palace of the Porphyrogenitus (Tr. ''Tekfur Sarayı'') in the Blachernae

Blachernae ( gkm, Βλαχέρναι) was a suburb in the northwestern section of Constantinople, the capital city of the Byzantine Empire. It is the site of a water source and a number of prominent churches were built there, most notably the great ...

quarter. The outer wall and the moat terminate even earlier, at the height of the Gate of Adrianople. The section between the Blachernae and the Golden Horn does not survive, since the line of the walls was later brought forward to cover the suburb of Blachernae, and its original course is impossible to ascertain as it lies buried beneath the modern city.

From the Sea of Marmara, the wall turns sharply to the northeast, until it reaches the Golden Gate, at about 14 m above sea level. From there and until the Gate of Rhegion the wall follows a more or less straight line to the north, climbing the city's Seventh Hill. From there the wall turns sharply to the northeast, climbing up to the Gate of St. Romanus, located near the peak of the Seventh Hill at some 68 m above sea level. From there the wall descends into the valley of the river Lycus, where it reaches its lowest point at 35 m above sea level. Climbing the slope of the Sixth Hill, the wall then rises up to the Gate of Charisius or Gate of Adrianople, at some 76 m height. From the Gate of Adrianople to the Blachernae, the walls fall to a level of some 60 m. From there the later walls of Blachernae project sharply to the west, reaching the coastal plain at the Golden Horn near the so-called Prisons of Anemas.

Construction

postern

A postern is a secondary door or gate in a fortification such as a city wall or castle curtain wall. Posterns were often located in a concealed location which allowed the occupants to come and go inconspicuously. In the event of a siege, a postern ...

s on the sides of the walls' towers.

The inner wall is a solid structure, 4.5–6 m thick and 12 m high. It is faced with carefully cut limestone blocks, while its core is filled with mortar made of lime and crushed bricks. Between seven and eleven bands of brick

A brick is a type of block used to build walls, pavements and other elements in masonry construction. Properly, the term ''brick'' denotes a block composed of dried clay, but is now also used informally to denote other chemically cured cons ...

, approximately 40 cm thick, traverse the structure, not only as a form of decoration, but also strengthening the cohesion of the structure by bonding the stone façade with the mortar core, and increasing endurance to earthquake

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the Earth's lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, from ...

s. The wall was strengthened with 96 towers, mainly square but also a few octagonal ones, three hexagonal and a single pentagonal one. They were 15–20 m tall and 10–12 m wide, and placed at irregular distances, according to the rise of the terrain: the intervals vary between 21 and 77 m, although most curtain wall sections measure between 40 and 60 meters. Each tower had a battlemented terrace on the top. Its interior was usually divided by a floor into two chambers, which did not communicate with each other. The lower chamber, which opened through the main wall to the city, was used for storage, while the upper one could be entered from the wall's walkway, and had windows for view and for firing projectiles. Access to the wall was provided by large ramps along their side. The lower floor could also be accessed from the ''peribolos'' by small posterns. Generally speaking, most of the surviving towers of the main wall have been rebuilt either in Byzantine or in Ottoman times, and only the foundations of some are of original Theodosian construction. Furthermore, while until the Komnenian period

The Byzantine Empire was ruled by emperors of the Komnenos dynasty for a period of 104 years, from 1081 to about 1185. The ''Komnenian'' (also spelled ''Comnenian'') period comprises the reigns of five emperors, Alexios I, John II, Manuel I, A ...

the reconstructions largely remained true to the original model, later modifications ignored the windows and embrasures on the upper store and focused on the tower terrace as the sole fighting platform

A fighting platform or terraceKaufmann, J.E. and Kaufmann, H.W (2001). ''The Medieval Fortress'', Cambridge, Massachusetts, Da Capo, p. 29. . is the uppermost defensive platform of an ancient or medieval gateway, tower (such as the fighting platfor ...

.

The outer wall was 2 m thick at its base, and featured arched chambers on the level of the ''peribolos'', crowned with a battlemented walkway, reaching a height of 8.5–9 m. Access to the outer wall from the city was provided either through the main gates or through small

The outer wall was 2 m thick at its base, and featured arched chambers on the level of the ''peribolos'', crowned with a battlemented walkway, reaching a height of 8.5–9 m. Access to the outer wall from the city was provided either through the main gates or through small postern

A postern is a secondary door or gate in a fortification such as a city wall or castle curtain wall. Posterns were often located in a concealed location which allowed the occupants to come and go inconspicuously. In the event of a siege, a postern ...

s on the base of the inner wall's towers. The outer wall likewise had towers, situated approximately midway between the inner wall's towers, and acting in supporting role to them. They are spaced at 48–78 m, with an average distance of 50–66 m. Only 62 of the outer wall's towers survive. With few exceptions, they are square or crescent-shaped, 12–14 m tall and 4 m wide. They featured a room with windows on the level of the ''peribolos'', crowned by a battlemented terrace, while their lower portions were either solid or featured small posterns, which allowed access to the outer terrace. The outer wall was a formidable defensive edifice in its own right: in the sieges of 1422 and 1453, the Byzantines and their allies, being too few to hold both lines of wall, concentrated on the defence of the outer wall.

The moat was situated at a distance of about 20 m from the outer wall. The moat itself was over 20 m wide and as much as 10 m deep, featuring a 1.5 m tall crenellated

A battlement in defensive architecture, such as that of city walls or castles, comprises a parapet (i.e., a defensive low wall between chest-height and head-height), in which gaps or indentations, which are often rectangular, occur at interva ...

wall on the inner side, serving as a first line of defence. Transverse walls cross the moat, tapering towards the top so as not to be used as bridges. Some of them have been shown to contain pipes carrying water into the city from the hill country to the city's north and west. Their role has therefore been interpreted as that of aqueducts for filling the moat and as dams dividing it into compartments and allowing the water to be retained over the course of the walls. According to Alexander van Millingen

Prof Alexander van Millingen DD (1840–1915) was a scholar in the field of Byzantine architecture, and a professor of history at Robert College, Istanbul between 1879 and 1915. His works are now public domain in many jurisdictions.

Life

He was b ...

, there is little direct evidence in the accounts of the city's sieges to suggest that the moat was ever actually flooded. In the sections north of the Gate of St. Romanus, the steepness of the slopes of the Lycus valley made the construction maintenance of the moat problematic; it is probable therefore that the moat ended at the Gate of St. Romanus, and did not resume until after the Gate of Adrianople.

The weakest section of the wall was the so-called ''Mesoteichion'' (Μεσοτείχιον, "Middle Wall"). Modern scholars are not in agreement over the extent of this portion of the wall, which has been variously defined from as narrowly as the stretch between the Gate of St. Romanus and the Fifth Military Gate (A.M. Schneider) to as broad as from the Gate of Rhegion to the Fifth Military Gate (B. Tsangadas) or from the Gate of St. Romanus to the Gate of Adrianople (A. van Millingen).

The walls survived the entire Ottoman period and appeared in travelogues of foreign visitors to Constantinople/Istanbul. A 16th century Chinese geographical treatises, for example, recorded that "Its city has two walls. a sovereign prince lives in the city ..."

Gates

The wall contained nine main gates, which pierced both the inner and the outer walls, and a number of smallerpostern

A postern is a secondary door or gate in a fortification such as a city wall or castle curtain wall. Posterns were often located in a concealed location which allowed the occupants to come and go inconspicuously. In the event of a siege, a postern ...

s. The exact identification of several gates is debatable for a number of reasons. The Byzantine chroniclers provide more names than the number of the gates, the original Greek names fell mostly out of use during the Ottoman period, and literary and archaeological sources provide often contradictory information. Only three gates, the Golden Gate, the Gate of Rhegion and the Gate of Charisius, can be established directly from the literary evidence.

In the traditional nomenclature, established by Philipp Anton Dethier in 1873, the gates are distinguished into the "Public Gates" and the "Military Gates", which alternated over the course of the walls. According to Dethier's theory, the former were given names and were open to civilian traffic, leading across the moat on bridges, while the latter were known by numbers, restricted to military use, and only led to the outer sections of the walls. Today this division is, if at all, retained only as a historiographical convention. First, there is sufficient reason to believe that several of the "Military Gates" were also used by civilian traffic. In addition, a number of them have proper names, and the established sequence of numbering them, based on their perceived correspondence with the names of certain city quarters lying between the Constantinian and Theodosian walls which have numerical origins, has been shown to be erroneous: for instance, the ''Deuteron'', the "Second" quarter, was not located in the southwest behind the Gate of the ''Deuteron'' or "Second Military Gate" as would be expected, but in the northwestern part of the city.

=First Military Gate

= The gate is a small postern, which lies at the first tower of the land walls, at the junction with the sea wall. It features a wreathed '' Chi-Rhō''Christogram

A Christogram ( la, Monogramma Christi) is a monogram or combination of letters that forms an abbreviation for the name of Jesus Christ, traditionally used as a Christian symbolism, religious symbol within the Christian Church.

One of the oldes ...

above it. It was known in late Ottoman times as the ''Tabak Kapı''.

=Golden Gate

= Following the walls from south to north, the Golden Gate ( el, Χρυσεία Πύλη, links=no, ''Chryseia Pylē''; la, Porta Aurea, links=no; tr, Altınkapı or Yaldızlıkapı, links=no), is the first gate to be encountered. It was the main ceremonial entrance into the capital, used especially for the occasions of a

Following the walls from south to north, the Golden Gate ( el, Χρυσεία Πύλη, links=no, ''Chryseia Pylē''; la, Porta Aurea, links=no; tr, Altınkapı or Yaldızlıkapı, links=no), is the first gate to be encountered. It was the main ceremonial entrance into the capital, used especially for the occasions of a triumph

The Roman triumph (Latin triumphus) was a celebration for a victorious military commander in ancient Rome. For later imitations, in life or in art, see Trionfo. Numerous later uses of the term, up to the present, are derived directly or indirectl ...

al entry of an emperor into the capital on the occasion of military victories or other state occasions such as coronations. On rare occasions, as a mark of honor, the entry through the gate was allowed to non-imperial visitors: papal legate

300px, A woodcut showing Henry II of England greeting the pope's legate.

A papal legate or apostolic legate (from the ancient Roman title ''legatus'') is a personal representative of the pope to foreign nations, or to some part of the Catholic ...

s (in 519 and 868) and, in 710, to Pope Constantine. The Gate was used for triumphal entries until the Komnenian period

The Byzantine Empire was ruled by emperors of the Komnenos dynasty for a period of 104 years, from 1081 to about 1185. The ''Komnenian'' (also spelled ''Comnenian'') period comprises the reigns of five emperors, Alexios I, John II, Manuel I, A ...

; thereafter, the only such occasion was the entry of Michael VIII Palaiologos

Michael VIII Palaiologos or Palaeologus ( el, Μιχαὴλ Δούκας Ἄγγελος Κομνηνὸς Παλαιολόγος, Mikhaēl Doukas Angelos Komnēnos Palaiologos; 1224 – 11 December 1282) reigned as the co-emperor of the Empire ...

into the city on 15 August 1261, after its reconquest from the Latins

The Latins were originally an Italic tribe in ancient central Italy from Latium. As Roman power and colonization spread Latin culture during the Roman Republic.

Latins culturally "Romanized" or "Latinized" the rest of Italy, and the word Latin ...

. With the progressive decline in Byzantium's military fortunes, the gates were walled up and reduced in size in the later Palaiologan period

The Byzantine Empire was ruled by the Palaiologos dynasty in the period between 1261 and 1453, from the restoration of Byzantine rule to Constantinople by the usurper Michael VIII Palaiologos following its recapture from the Latin Empire, founde ...

, and the complex converted into a citadel and refuge. The Golden Gate was emulated elsewhere, with several cities naming their principal entrance thus, for instance Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area, and the capi ...

(also known as the Vardar Gate) or Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου, ''Antiókheia hē epì Oróntou'', Learned ; also Syrian Antioch) grc-koi, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου; or Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπ� ...

(the Gate of Daphne), as well as the Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rusʹ, also known as Kyivan Rusʹ ( orv, , Rusĭ, or , , ; Old Norse: ''Garðaríki''), was a state in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical Atlas of ...

, who built monumental "Golden Gates" at Kiev

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the List of European cities by populat ...

and Vladimir

Vladimir may refer to:

Names

* Vladimir (name) for the Bulgarian, Croatian, Czech, Macedonian, Romanian, Russian, Serbian, Slovak and Slovenian spellings of a Slavic name

* Uladzimir for the Belarusian version of the name

* Volodymyr for the Ukr ...

. The entrance to San Francisco Bay in California was similarly named the Golden Gate

The Golden Gate is a strait on the west coast of North America that connects San Francisco Bay to the Pacific Ocean. It is defined by the headlands of the San Francisco Peninsula and the Marin Peninsula, and, since 1937, has been spanned by th ...

in the middle of the nineteenth century, in a distant historical tribute to Byzantium.

The date of the gate's construction is uncertain, with scholars divided between Theodosius I

Theodosius I ( grc-gre, Θεοδόσιος ; 11 January 347 – 17 January 395), also called Theodosius the Great, was Roman emperor from 379 to 395. During his reign, he succeeded in a crucial war against the Goths, as well as in two ...

and Theodosius II

Theodosius II ( grc-gre, Θεοδόσιος, Theodosios; 10 April 401 – 28 July 450) was Roman emperor for most of his life, proclaimed ''Augustus (title), augustus'' as an infant in 402 and ruling as the eastern Empire's sole emperor after ...

. Earlier scholars favored the former, but the current majority view tends to the latter, meaning that the gate was constructed as an integral part of the Theodosian Walls. The debate has been carried over to a Latin inscription in metal letters, now lost, which stood above the doors and commemorated their gilding in celebration of the defeat of an unnamed usurper:

(English translation)

Curiously, while the legend has not been reported by any known Byzantine author, an investigation of the surviving holes wherein the metal letters were riveted verified its accuracy. It also showed that the first line stood on the western face of the arch, while the second on the eastern. According to the current view, this refers to the usurper Joannes

Joannes or John ( la, Iohannes; died 425) was western Roman emperor from 423 to 425.

On the death of the Emperor Honorius (15 August 423), Theodosius II, the remaining ruler of the House of Theodosius, hesitated in announcing his uncle's d ...

(r. 423–425), while according to the supporters of the traditional view, it indicates the gate's construction as a free-standing triumphal arch

A triumphal arch is a free-standing monumental structure in the shape of an archway with one or more arched passageways, often designed to span a road. In its simplest form a triumphal arch consists of two massive piers connected by an arch, crow ...

in 388–391 to commemorate the defeat of the usurper Magnus Maximus

Magnus Maximus (; cy, Macsen Wledig ; died 8 August 388) was Roman emperor of the Western Roman Empire from 383 to 388. He usurped the throne from emperor Gratian in 383 through negotiation with emperor Theodosius I.

He was made emperor in B ...

(r. 383–388), and which was only later incorporated into the Theodosian Walls.

The gate, built of large square blocks of polished white

The gate, built of large square blocks of polished white marble

Marble is a metamorphic rock composed of recrystallized carbonate minerals, most commonly calcite or Dolomite (mineral), dolomite. Marble is typically not Foliation (geology), foliated (layered), although there are exceptions. In geology, the ...

fitted together without cement, has the form of a triumphal arch with three arched gates, the middle one larger than the two others. The gate is flanked by large square towers, which form the 9th and 10th towers of the inner Theodosian wall. With the exception of the central portal, the gate remained open to everyday traffic. The structure was richly decorated with numerous statues, including a statue of Theodosius I on an elephant-drawn quadriga

A () is a car or chariot drawn by four horses abreast and favoured for chariot racing in Classical Antiquity and the Roman Empire until the Late Middle Ages. The word derives from the Latin contraction of , from ': four, and ': yoke.

The four- ...

on top, echoing the ''Porta Triumphalis'' of Rome, which survived until it fell down in the 740 Constantinople earthquake

The 740 Constantinople earthquake took place on 26 October, 740, in the vicinity of Constantinople and the Sea of Marmara. Antonopoulos, 1980

In Constantinople, the earthquake caused the collapse of many public buildings. The Walls of Constantinop ...

. Other sculptures were a large cross, which fell in an earthquake in 561 or 562; a Victory

The term victory (from Latin ''victoria'') originally applied to warfare, and denotes success achieved in personal Duel, combat, after military operations in general or, by extension, in any competition. Success in a military campaign constitu ...

, which was cast down in the reign of Michael III

Michael III ( grc-gre, Μιχαήλ; 9 January 840 – 24 September 867), also known as Michael the Drunkard, was Byzantine Emperor from 842 to 867. Michael III was the third and traditionally last member of the Amorian (or Phrygian) dynasty. ...

; and a crowned Fortune

Fortune may refer to:

General

* Fortuna or Fortune, the Roman goddess of luck

* Luck

* Wealth

* Fortune, a prediction made in fortune-telling

* Fortune, in a fortune cookie

Arts and entertainment Film and television

* ''The Fortune'' (1931 film) ...

of the city. In 965, Nikephoros II Phokas

Nikephoros II Phokas (; – 11 December 969), Latinized Nicephorus II Phocas, was Byzantine emperor from 963 to 969. His career, not uniformly successful in matters of statecraft or of war, nonetheless included brilliant military exploits whi ...

installed the captured bronze city gates of Mopsuestia

Mopsuestia and Mopsuhestia ( grc, Μοψουεστία and Μόψου ἑστία, Mopsou(h)estia and Μόψου ''Mopsou'' and Μόψου πόλις and Μόψος; Byzantine Greek: ''Mamista'', ''Manistra'', ''Mampsista''; Arabic: ''al-Maṣ� ...

in the place of the original ones.

Pierre Gilles

Petrus Gyllius or Gillius (or Pierre Gilles) (1490–1555) was a French natural scientist, topographer and translator.

Gilles was born in Albi, southern France. A great traveller, he studied the Mediterranean and Orient, producing such works as ...

and English travelers from the 17th century, these reliefs were arranged in two tiers, and featured mythological scenes, including the Labours of Hercules

The Labours of Hercules or Labours of Heracles ( grc-gre, οἱ Ἡρακλέους ἆθλοι, ) are a series of episodes concerning a penance carried out by Heracles, the greatest of the Greek heroes, whose name was later romanised ...

. These reliefs, lost since the 17th century with the exception of some fragments now in the Istanbul Archaeological Museum, were probably put in place in the 9th or 10th centuries to form the appearance of a triumphal gate. According to other descriptions, the outer gate was also topped by a statue of Victory

The term victory (from Latin ''victoria'') originally applied to warfare, and denotes success achieved in personal Duel, combat, after military operations in general or, by extension, in any competition. Success in a military campaign constitu ...

, holding a crown.

Despite its ceremonial role, the Golden Gate was one of the stronger positions along the walls of the city, withstanding several attacks during the various sieges. With the addition of transverse walls on the ''peribolos'' between the inner and outer walls, it formed a virtually separate fortress. Its military value was recognized by John VI Kantakouzenos

John VI Kantakouzenos or Cantacuzene ( el, , ''Iōánnēs Ángelos Palaiológos Kantakouzēnós''; la, Johannes Cantacuzenus; – 15 June 1383) was a Byzantine Greek nobleman, statesman, and general. He served as grand domestic under An ...

(r. 1347–1354), who records that it was virtually impregnable, capable of holding provisions for three years and defying the whole city if need be. He repaired the marble towers and garrisoned the fort, but had to surrender it to John V Palaiologos

John V Palaiologos or Palaeologus ( el, Ἰωάννης Παλαιολόγος, ''Iōánnēs Palaiológos''; 18 June 1332 – 16 February 1391) was Byzantine emperor from 1341 to 1391, with interruptions.

Biography

John V was the son of E ...

(r. 1341–1391) when he abdicated in 1354. John V undid Kantakouzenos' repairs and left it unguarded, but in 1389–90 he too rebuilt and expanded the fortress, erecting two towers behind the gate and extending a wall some 350 m to the sea walls, thus forming a separate fortified enceinte

Enceinte (from Latin incinctus: girdled, surrounded) is a French term that refers to the "main defensive enclosure of a fortification". For a castle, this is the main defensive line of wall towers and curtain walls enclosing the position. Fo ...

inside the city to serve as a final refuge. In the event, John V was soon after forced to flee there from a coup led by his grandson, John VII. The fort held out successfully in the subsequent siege that lasted several months, and in which cannons were possibly employed. In 1391 John V was compelled to raze the fort by Sultan Bayezid I

Bayezid I ( ota, بايزيد اول, tr, I. Bayezid), also known as Bayezid the Thunderbolt ( ota, link=no, یلدیرم بايزيد, tr, Yıldırım Bayezid, link=no; – 8 March 1403) was the Ottoman Sultan from 1389 to 1402. He adopted ...

(r. 1389–1402), who otherwise threatened to blind his son Manuel, whom he held captive. Emperor John VIII Palaiologos

John VIII Palaiologos or Palaeologus ( gr, Ἰωάννης Παλαιολόγος, Iōánnēs Palaiológos; 18 December 1392 – 31 October 1448) was the penultimate Byzantine emperor, ruling from 1425 to 1448.

Biography

John VIII was ...

(r. 1425–1448) attempted to rebuild it in 1434, but was thwarted by Sultan Murad II

Murad II ( ota, مراد ثانى, Murād-ı sānī, tr, II. Murad, 16 June 1404 – 3 February 1451) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1421 to 1444 and again from 1446 to 1451.

Murad II's reign was a period of important economic deve ...

.

According to one of the many Greek legends about the Constantinople's fall to the Ottomans, when the Turks entered the city, an angel rescued the emperor Constantine XI Palaiologos

Constantine XI Dragases Palaiologos or Dragaš Palaeologus ( el, Κωνσταντῖνος Δραγάσης Παλαιολόγος, ''Kōnstantînos Dragásēs Palaiológos''; 8 February 1405 – 29 May 1453) was the last List of Byzantine em ...

, turned him into marble and placed him in a cave under the earth near the Golden Gate, where he waits to be brought to life again to conquer the city back for Christians. The legend explained the later walling up of the gate as a Turkish precaution against this prophecy.

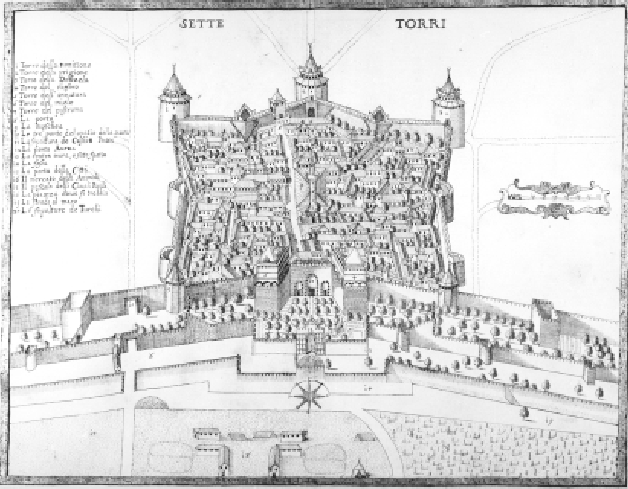

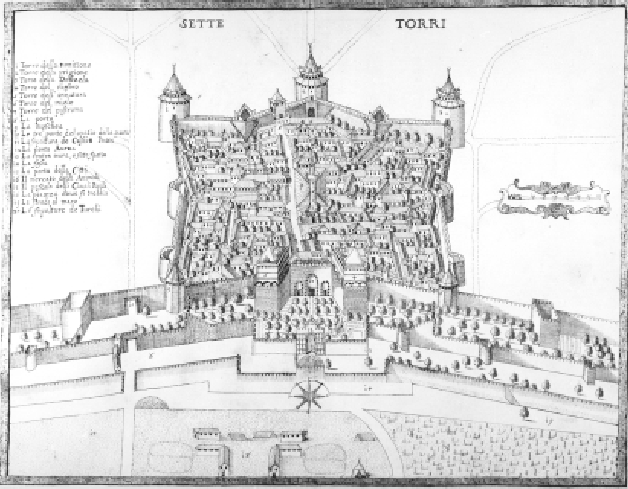

= Yedikule Fortress

= After his

After his conquest of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city fell on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 53-day siege which had begun o ...

in 1453, Sultan Mehmed II

Mehmed II ( ota, محمد ثانى, translit=Meḥmed-i s̱ānī; tr, II. Mehmed, ; 30 March 14323 May 1481), commonly known as Mehmed the Conqueror ( ota, ابو الفتح, Ebū'l-fetḥ, lit=the Father of Conquest, links=no; tr, Fâtih Su ...

built a new fort in 1458. By adding three larger towers to the four pre-existing ones (towers 8 to 11) on the inner Theodosian wall, he formed the Fortress of the Seven Towers ( tr, Yedikule Hisarı or ''Zindanları''). It lost its function as a gate, and for much of the Ottoman era, it was used as a treasury, archive, and state prison. It eventually became a museum in 1895.

=Xylokerkos Gate

= The Xylokerkos or Xerokerkos Gate (), now known as the

The Xylokerkos or Xerokerkos Gate (), now known as the Belgrade

Belgrade ( , ;, ; Names of European cities in different languages: B, names in other languages) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city in Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers a ...

Gate (''Belgrat Kapısı''), lies between towers 22 and 23. Alexander van Millingen identified it with the Second Military Gate, which is located further north. Its name derives from the fact that it led to a wooden ''circus'' (amphitheatre

An amphitheatre (British English) or amphitheater (American English; both ) is an open-air venue used for entertainment, performances, and sports. The term derives from the ancient Greek ('), from ('), meaning "on both sides" or "around" and ...

) outside the walls. The gate complex is approximately 12 m wide and almost 20 m high, while the gate itself spans 5 m.

According to a story related by Niketas Choniates, in 1189 the gate was walled off by Emperor Isaac II Angelos

Isaac II Angelos or Angelus ( grc-gre, Ἰσαάκιος Κομνηνός Ἄγγελος, ; September 1156 – January 1204) was Byzantine Emperor from 1185 to 1195, and again from 1203 to 1204.

His father Andronikos Doukas Angelos was a ...

, because according to a prophecy, it was this gate that Western Emperor Frederick Barbarossa

Frederick Barbarossa (December 1122 – 10 June 1190), also known as Frederick I (german: link=no, Friedrich I, it, Federico I), was the Holy Roman Emperor from 1155 until his death 35 years later. He was elected King of Germany in Frankfurt on ...

would enter the city through. It was re-opened in 1346, but closed again before the siege of 1453 and remained closed until 1886, leading to its early Ottoman name, ''Kapalı Kapı'' ("Closed Gate").

=Second Military Gate

= The gate () is located between towers 30 and 31, little remains of the original gate, and the modern reconstruction may not be accurate.=Gate of the Spring

= The Gate of the Spring or Pēgē Gate ( in Greek) was named after a popular monastery outside the Walls, the '' Zōodochos Pēgē'' ("

The Gate of the Spring or Pēgē Gate ( in Greek) was named after a popular monastery outside the Walls, the '' Zōodochos Pēgē'' ("Life-giving Spring

The Mother of God of the Life-giving Spring or Life-giving Font (Greek: ''Ζωοδόχος Πηγή,'' ''Zoodochos Pigi'', Russian: ''Живоносный Источник'') is an epithet of the Holy Theotokos that originated with her revelation ...

") in the modern suburb of Balıklı.

Its modern Turkish name, Gate of Selymbria

Selymbria ( gr, Σηλυμβρία),Demosthenes, '' de Rhod. lib.'', p. 198, ed. Reiske. or Selybria (Σηλυβρία), or Selybrie (Σηλυβρίη), was a town of ancient Thrace on the Propontis, 22 Roman miles east from Perinthus, and 44 Rom ...

(Tr. ''Silivri Kapısı'' or ''Silivrikapı'', Gk. ), appeared in Byzantine sources shortly before 1453. It lies between the heptagonal towers 35 and 36, which were extensively rebuilt in later Byzantine times: its southern tower bears an inscription dated to 1439 commemorating repairs carried out under John VIII Palaiologos

John VIII Palaiologos or Palaeologus ( gr, Ἰωάννης Παλαιολόγος, Iōánnēs Palaiológos; 18 December 1392 – 31 October 1448) was the penultimate Byzantine emperor, ruling from 1425 to 1448.

Biography

John VIII was ...

. The gate arch was replaced in the Ottoman period. In addition, in 1998 a subterranean basement with 4th/5th century reliefs and tombs was discovered underneath the gate.

Van Millingen identifies this gate with the early Byzantine Gate of Melantias (Πόρτα Μελαντιάδος), but more recent scholars have proposed the identification of the latter with one of the gates

Gates is the plural of gate, a point of entry to a space which is enclosed by walls. It may also refer to:

People

* Gates (surname), various people with the last name

* Gates Brown (1939-2013), American Major League Baseball player

* Gates McFadde ...

of the city's original Constantinian Wall (see above).

It was through this gate that the forces of the Empire of Nicaea

The Empire of Nicaea or the Nicene Empire is the conventional historiographic name for the largest of the three Byzantine Greek''A Short history of Greece from early times to 1964'' by W. A. Heurtley, H. C. Darby, C. W. Crawley, C. M. Woodhouse ...

, under General Alexios Strategopoulos

Alexios Komnenos Strategopoulos ( gr, Ἀλέξιος Κομνηνὸς Στρατηγόπουλος) was a Byzantine aristocrat and general who rose to the rank of '' megas domestikos'' and ''Caesar''. Distantly related to the Komnenian dynasty ...

, entered and retook the city from the Latins

The Latins were originally an Italic tribe in ancient central Italy from Latium. As Roman power and colonization spread Latin culture during the Roman Republic.

Latins culturally "Romanized" or "Latinized" the rest of Italy, and the word Latin ...

on 25 July 1261.

=Third Military Gate

= The Third Military Gate (), named after the quarter of the ''Triton'' ("the Third") that lies behind it, is situated shortly after the Pege Gate, exactly before the C-shaped section of the walls known as the "''Sigma

Sigma (; uppercase Σ, lowercase σ, lowercase in word-final position ς; grc-gre, σίγμα) is the eighteenth letter of the Greek alphabet. In the system of Greek numerals, it has a value of 200. In general mathematics, uppercase Σ is used as ...

''", between towers 39 and 40. It has no Turkish name, and is of middle or late Byzantine construction. The corresponding gate in the outer wall was preserved until the early 20th century, but has since disappeared. It is very likely that this gate is to be identified with the Gate of Kalagros ().

=Gate of Rhegion

= Modern ''Yeni Mevlevihane Kapısı'', located between towers 50 and 51 is commonly referred to as the Gate of Rhegion () in early modern texts, allegedly named after the suburb of Rhegion (modernKüçükçekmece

Küçükçekmece (; meaning “small-drawer”, from much earlier ''Rhagion'' and ''Küçükçökmece as “little breakdown''" or “''little depression''”, in more ancient times just as Bathonea), is a suburb and district of Istanbul, Turke ...

), or as the Gate of Rhousios () after the hippodrome faction of the Reds (, ''rhousioi'') which was supposed to have taken part in its repair. From Byzantine texts it appears that the correct form is Gate of Rhesios (), named according to the 10th-century ''Suda

The ''Suda'' or ''Souda'' (; grc-x-medieval, Σοῦδα, Soûda; la, Suidae Lexicon) is a large 10th-century Byzantine encyclopedia of the ancient Mediterranean world, formerly attributed to an author called Soudas (Σούδας) or Souidas ...

'' lexicon after an ancient general of Greek Byzantium

Byzantium () or Byzantion ( grc, Βυζάντιον) was an ancient Greek city in classical antiquity that became known as Constantinople in late antiquity and Istanbul today. The Greek name ''Byzantion'' and its Latinization ''Byzantium'' cont ...

. A.M. Schneider also identifies it with the Gate of Myriandr n or Polyandrion ("Place of Many Men"), possibly a reference to its proximity to a cemetery. It is the best-preserved of the gates, and retains substantially unaltered from its original, 5th-century appearance.

=Fourth Military Gate

= The so-called Fourth Military Gate stands between towers 59 and 60, and is currently walled up. Recently, it has been suggested that this gate is actually the Gate of St. Romanus, but the evidence is uncertain.= Gate of St. Romanus

= The Gate of St. Romanus () was named so after a nearby church and lies between towers 65 and 66. It is known in Turkish as ''Topkapı'', the "Cannon Gate", after the great Ottoman cannon, the " Basilic", that was placed opposite it during the 1453 siege. With a gatehouse of 26.5 m, it is the second-largest gate after the Golden Gate. According to conventional wisdom, it is here thatConstantine XI Palaiologos

Constantine XI Dragases Palaiologos or Dragaš Palaeologus ( el, Κωνσταντῖνος Δραγάσης Παλαιολόγος, ''Kōnstantînos Dragásēs Palaiológos''; 8 February 1405 – 29 May 1453) was the last List of Byzantine em ...

, the last Byzantine emperor, was killed on 29 May 1453.

This is not the "Topkapı". This website clarifies this:

https://istanbulsurlari.ku.edu.tr/en/