This article covers the history and bibliography of

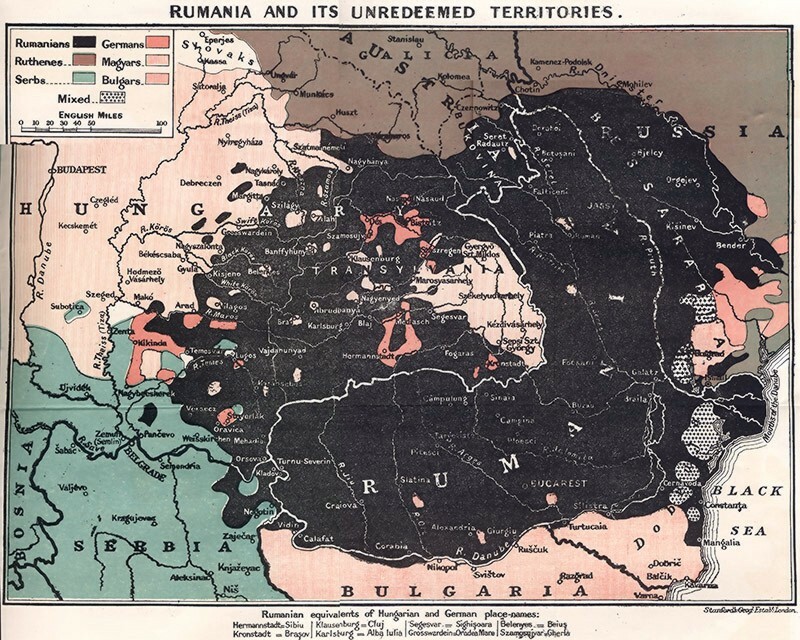

Romania

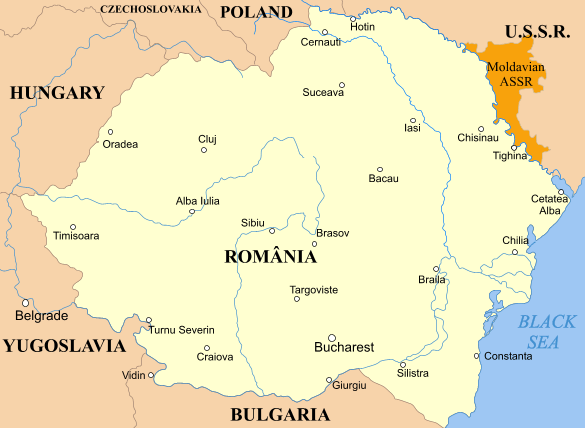

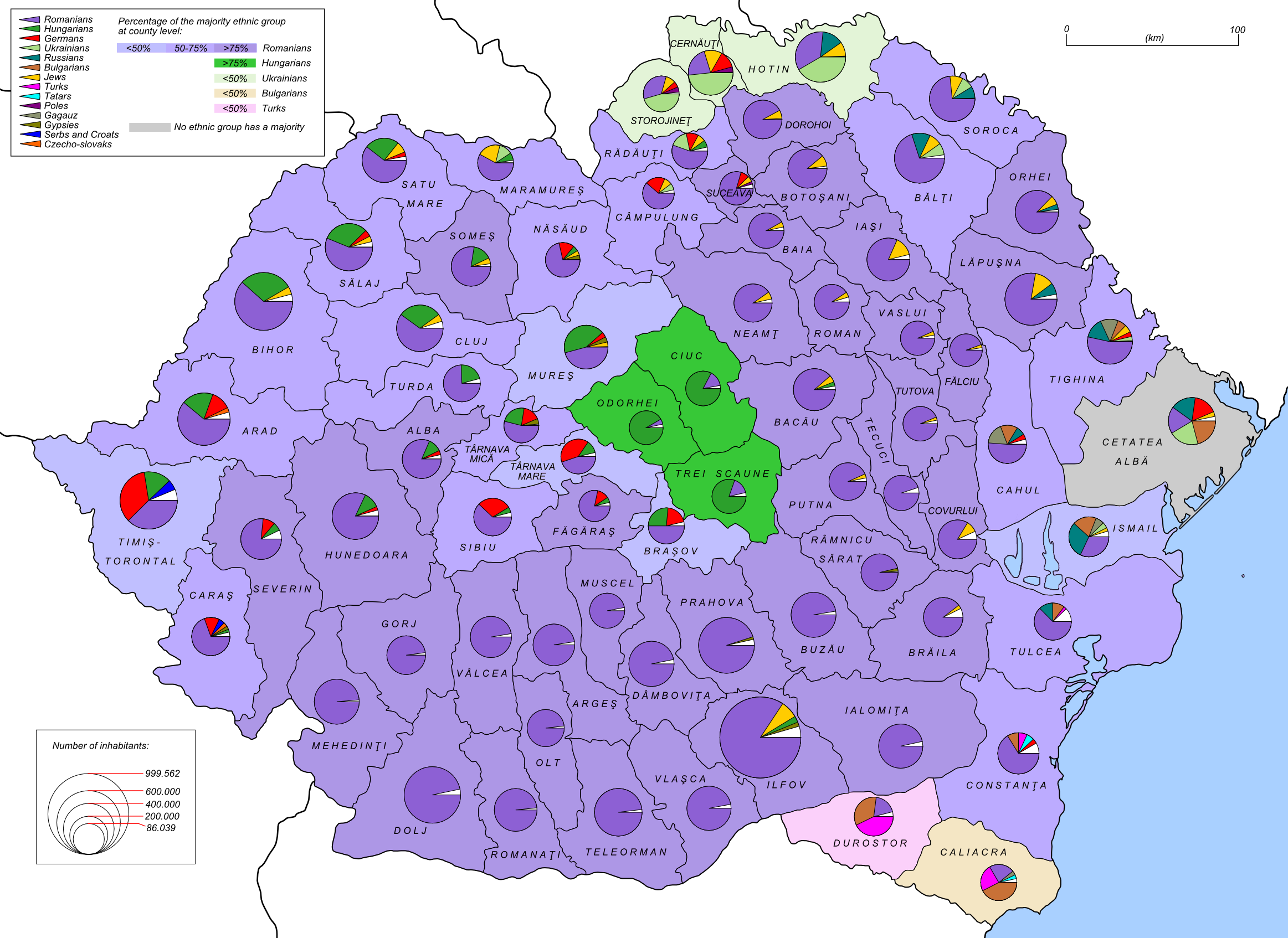

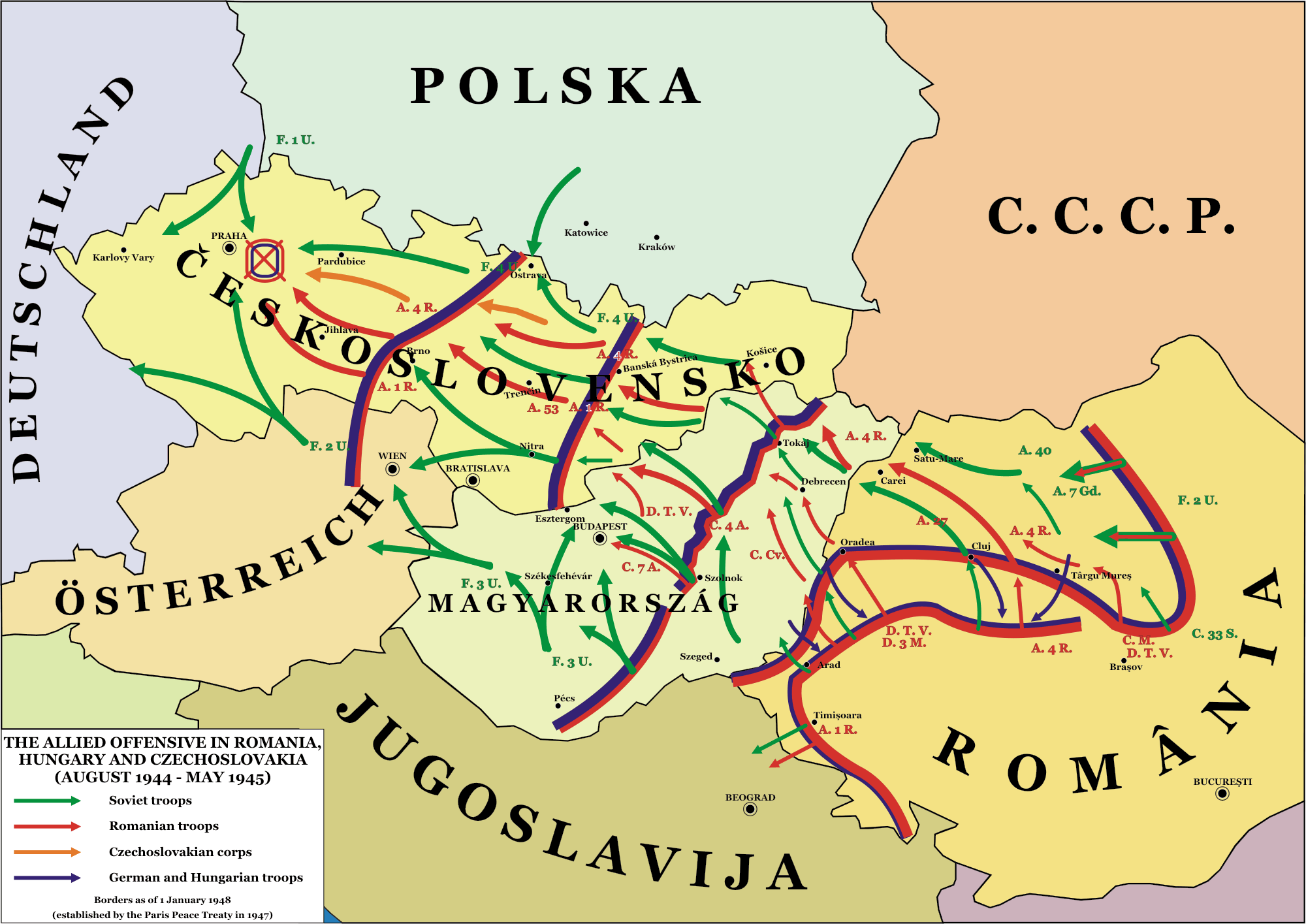

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

and links to specialized articles.

Prehistory

34,950-year-old remains of

modern humans with a possible

Neanderthal

Neanderthals (, also ''Homo neanderthalensis'' and erroneously ''Homo sapiens neanderthalensis''), also written as Neandertals, are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans who lived in Eurasia until about 40,000 years ago. While th ...

ian trait were discovered in present-day Romania when the ''

Peștera cu Oase

Peștera cu Oase (, meaning "The Cave with Bones") is a system of 12 karstic galleries and chambers located near the city Anina, in the Caraș-Severin county, southwestern Romania, where some of the oldest European early modern human (EEMH) rem ...

'' ("Cave with Bones") was uncovered in 2002. In 2011, older modern human remains were identified in the UK (

Kents Cavern

Kents Cavern is a cave system in Torquay, Devon, England. It is notable for its archaeological and geological features. The cave system is open to the public and has been a geological Site of Special Scientific Interest since 1952 and a Schedule ...

41,500 to 44,200 years old) and Italy (

Grotta del Cavallo 43,000 to 45,000 years old) but the Romanian fossils are still among the oldest remains of ''

Homo sapiens

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, ...

'' in Europe, so they may be representative of the first such people to have entered Europe.

The remains present a mixture of archaic, early modern human and Neanderthal morphological features.

[Jonathan Amos]

"Human fossils set European record"

''BBC News

BBC News is an operational business division of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) responsible for the gathering and broadcasting of news and current affairs in the UK and around the world. The department is the world's largest broadca ...

'', 22 September 2003

The Neolithic-Age Cucuteni

Cucuteni () is a commune in Iași County, Western Moldavia, Romania, with a population of 1,446 as of 2002. The commune is composed of four villages: Băiceni, Bărbătești, Cucuteni, and Săcărești.

It is located from the city of Iași an ...

area in northeastern Romania was the western region of one of the earliest European civilizations, known as the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture. The earliest-known salt works is at Poiana Slatinei

Poiana may refer to:

Geography Italy

* Pojana Maggiore (Poiana Maggiore), a town in the province of Vicenza, Veneto, Italy

* Villa Pojana, or Poiana, a patrician villa in Pojana Maggiore, a UNESCO World Heritage site

Moldova

* Poiana, Șold� ...

near the village of Lunca; it was first used in the early Neolithic around 6050 BC by the Starčevo culture and later by the Cucuteni-Trypillia culture in the pre-Cucuteni

Cucuteni () is a commune in Iași County, Western Moldavia, Romania, with a population of 1,446 as of 2002. The commune is composed of four villages: Băiceni, Bărbătești, Cucuteni, and Săcărești.

It is located from the city of Iași an ...

period. Evidence from this and other sites indicates the Cucuteni-Trypillia culture extracted salt from salt-laden spring water through the process of briquetage.

Dacia

The

The Dacians

The Dacians (; la, Daci ; grc-gre, Δάκοι, Δάοι, Δάκαι) were the ancient Indo-European inhabitants of the cultural region of Dacia, located in the area near the Carpathian Mountains and west of the Black Sea. They are often consid ...

, who are widely accepted to be the same people as the Getae

The Getae ( ) or Gets ( ; grc, Γέται, singular ) were a Thracian-related tribe that once inhabited the regions to either side of the Lower Danube, in what is today northern Bulgaria and southern Romania. Both the singular form ''Get'' an ...

, with Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

sources predominantly using the name Dacian and Greek sources predominantly using the name Getae, were a branch of Thracians

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European languages, Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. ...

who inhabited Dacia

Dacia (, ; ) was the land inhabited by the Dacians, its core in Transylvania, stretching to the Danube in the south, the Black Sea in the east, and the Tisza in the west. The Carpathian Mountains were located in the middle of Dacia. It thus r ...

, which corresponds with modern Romania, Moldova

Moldova ( , ; ), officially the Republic of Moldova ( ro, Republica Moldova), is a Landlocked country, landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Romania to the west and Ukraine to the north, east, and south. The List of states ...

, northern Bulgaria, south-western Ukraine, Hungary east of the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

river and West Banat in Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe, Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Bas ...

.

The earliest written evidence of people living in the territory of present-day Romania comes from Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria ( Italy). He is known f ...

in Book IV of his ''Histories

Histories or, in Latin, Historiae may refer to:

* the plural of history

* ''Histories'' (Herodotus), by Herodotus

* ''The Histories'', by Timaeus

* ''The Histories'' (Polybius), by Polybius

* ''Histories'' by Gaius Sallustius Crispus (Sallust), ...

'', which was written in 440 BC; He writes that the tribal union/confederation of the Getae

The Getae ( ) or Gets ( ; grc, Γέται, singular ) were a Thracian-related tribe that once inhabited the regions to either side of the Lower Danube, in what is today northern Bulgaria and southern Romania. Both the singular form ''Get'' an ...

were defeated by the Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

Emperor Darius the Great

Darius I ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his d ...

during his campaign against the Scythians

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an Ancient Iranian peoples, ancient Eastern Iranian languages, Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved f ...

, and describes the Dacians as the bravest and most law-abiding of the Thracians.

The Dacians spoke a dialect of the Thracian language but were influenced culturally by the neighbouring Scythians in the east and by the Celtic invaders of Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the Ap ...

in the 4th century.

Due to the fluctuating nature of the Dacian states, especially before the time of Burebista and before the 1st century AD, the Dacians would often be split into different kingdoms thus having different rulers, known rulers of the Dacians include: Charnabon, king of the Getae as mentioned by Sophocles in Triptolemus in the 5th century BC, Cothelas

Cothelas ( grc, Κοθήλας), also known as Gudila ( fl. 4th century B.C.), was a king of the Getae who ruled an area near the Black Sea, between northern Thrace and the Danube. His polity also included the important port of Odessos. Around 34 ...

, father of Meda of Odessa Meda of Odessos ( grc, Μήδα, Mḗda), died 336 BC, was a Thracian princess, daughter of the king Cothelas a Getae, and wife of king Philip II of Macedon. Philip married her after Olympias.

According to N. G. L. Hammond, when Philip died, M ...

in the 4th century BC, Rex Histrianorum, ruler in Histria, mentioned by Trogus Pompeius and Justinus in 339 BC, Dual in the 3rd century BC, Moskon

Moskon was a Getic king who ruled in the 3rd century BC the northern parts of Dobruja, probably being the head of a local tribal union, which had close relations with the local Greek colonies and adopted the Greek style of administration.

His exis ...

in the 3rd century BC, Dromichaetes

Dromichaetes ( grc, Δρομιχαίτης, Dromichaites) was king of the Getae on both sides of the lower Danube (present day Romania and Bulgaria) around 300 BC.

Background

The Getae had been federated in the Odrysian kingdom in the 5th ce ...

in the 3rd century BC, Zalmodegicus around year 200 BC, Rhemaxos

Rhemaxos was an ancient king who ruled to the north of Danube around 200 BC and who was the protector of the Greek colonies in Dobruja, receiving a tribute from them in exchange of protection against outside attacks. It appears that the links with ...

also around year 200 BC, Rubobostes Rubobostes was a Dacian king in Transylvania, during the 2nd century BC.

He was mentioned in Gnaeus Pompeius Trogus's ''Prolegomena''. Trogus wrote that during his rule, the Dacians' power increased, as they defeated the Celts

The Celts ( ...

before 168 BC, Zoltes

Zoltes was a chief of the southern Thracians, living in the Haemus mountains area. Leading small groups, he often made incursions into the Pontic cities and within their territories. He attacked the city of Histria, calling off the siege only a ...

after 168 BC,Oroles

Oroles was a Dacian king during the first half of the 2nd century BC.

He successfully opposed the Bastarnae, blocking their invasion into Transylvania.

The Roman historian Trogus Pompeius wrote about king Oroles punishing his soldiers into sleepi ...

in the 2nd century BC, Dicomes in the 1st century BC, Rholes in the 1st century BC, Dapyx in the 1st century BC, Zyraxes

Zyraxes was a Getae king who ruled the northern part of what is today Dobrogea in the 1st century BC. He was mentioned in relation with the campaigns of Marcus Licinius Crassus (grandson of the triumvir). His capital, Genucla, was besieged by ...

in the 1st century BC, Burebista

Burebista ( grc, Βυρεβίστας, Βοιρεβίστας) was the king of the Getae and Dacian tribes from 82/61BC to 45/44BC. He was the first king who successfully unified the tribes of the Dacian kingdom, which comprised the area locat ...

between 82 BC – 44 BC, Deceneus

Deceneus or Decaeneus (Greek: Δεκαίνεος, ''Dekaineos'') was a priest of Dacia during the reign of Burebista (82/61–45/44 BC). He is mentioned in the near-contemporary Greek ''Geographica'' of Strabo and in the 6th-century Latin ''Getica' ...

between 44 BC and around 27 BC, Thiamarkos between 1st century BC and 1st century AD, Dacian king (inscription "Basileys Thiamarkos epoiei"), Cotiso

Cotiso, Cotish or Cotison (flourished c. 30 BC) was a Dacian king who apparently ruled the mountains between Banat and Oltenia (modern-day Romania). Horace calls him king of the Dacians.John T. White, D.D. Oxon, ''The first (-fourth) book of the ...

between c. 40 BC and c.9 BC, Comosicus

Comosicus was a Dacian king and high priest who lived in the 1st century BC. The only reference to Comosicus is a passage in the writings of the Roman historian Jordanes.

Sources

Jordanes refers to Burebista as king of Dacia, but then goes on to ...

between 9 BC and 30 AD,[Dacia: Landscape, Colonization and Romanization by Ioana A Oltean, 2007, page 72, "At least two of his successors Comosicus and Scorillo/Corilus/Scoriscus became high priests and eventually Dacian kings"] Scorilo between c. 30 AD and 70 ADCoson

The Kosons are the only gold coins that have been minted by the Dacians, named after the Greek alphabet inscription "ΚΟΣΩΝ" on them.Bogdan Constantinescu et al,Archaeometallurgical Characterization Of Ancient Gold Artifacts From Romanian Museu ...

in the 1st century AD,[Dacia: Landscape, Colonization and Romanization by Ioana A Oltean, 2007, page 47, "Kings Coson (who minted his own coins) and Duras"] Duras between c. 69 AD to 87 AD,Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

in 106 AD, conquered by Emperor Trajan

Trajan ( ; la, Caesar Nerva Traianus; 18 September 539/11 August 117) was Roman emperor from 98 to 117. Officially declared ''optimus princeps'' ("best ruler") by the senate, Trajan is remembered as a successful soldier-emperor who presi ...

, however the Free Dacians outside of the Roman Empire remain independent, Pieporus

The Costoboci (; lat, Costoboci, Costobocae, Castabocae, Coisstoboci, grc, Κοστωβῶκοι, Κοστουβῶκοι or Κοιστοβῶκοι) were a Dacian tribe located, during the Roman imperial era, between the Carpathian Mountains an ...

, king of Dacian Costoboci

The Costoboci (; lat, Costoboci, Costobocae, Castabocae, Coisstoboci, grc, Κοστωβῶκοι, Κοστουβῶκοι or Κοιστοβῶκοι) were a Dacian tribe located, during the Roman imperial era, between the Carpathian Mountains an ...

in the 2nd century AD (inscription), possibly Tarbus in the 2nd century AD as Dio Cassius

Lucius Cassius Dio (), also known as Dio Cassius ( ), was a Roman historian and senator of maternal Greek origin. He published 80 volumes of the history on ancient Rome, beginning with the arrival of Aeneas in Italy. The volumes documented the ...

mentioned him without specifying his origin, some authors consider a possible Dacian ethnicity.

The Dacia of King Burebista

Burebista ( grc, Βυρεβίστας, Βοιρεβίστας) was the king of the Getae and Dacian tribes from 82/61BC to 45/44BC. He was the first king who successfully unified the tribes of the Dacian kingdom, which comprised the area locat ...

(82–44 BC) stretched from the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Roma ...

to the source of the river Tisa and from the Balkan Mountains

The Balkan mountain range (, , known locally also as Stara planina) is a mountain range in the eastern part of the Balkan Peninsula in Southeastern Europe. The range is conventionally taken to begin at the peak of Vrashka Chuka on the border betw ...

to Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

.Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

stated that the lands of the Dacians started on the eastern edge of the Hercynian Forest (Black Forest). After Burebista's death, his kingdom split in four states, later five.

Geto-Dacians inhabited both sides of the Tisa river prior to the rise of the Celtic Boii

The Boii (Latin plural, singular ''Boius''; grc, Βόιοι) were a Celtic tribe of the later Iron Age, attested at various times in Cisalpine Gaul (Northern Italy), Pannonia (Hungary), parts of Bavaria, in and around Bohemia (after whom the ...

and again after the latter were defeated by the Dacians under the king Burebista. It seems likely that the Dacian state arose as a tribal confederacy, which was united only by charismatic leadership in both military-political and ideological-religious domains. At the beginning of the 2nd century BC (before 168 BC), under the rule of king Rubobostes Rubobostes was a Dacian king in Transylvania, during the 2nd century BC.

He was mentioned in Gnaeus Pompeius Trogus's ''Prolegomena''. Trogus wrote that during his rule, the Dacians' power increased, as they defeated the Celts

The Celts ( ...

, a Dacian king in present-day Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the Ap ...

, the Dacians' power in the Carpathian basin increased after they defeated the Celts

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancien ...

, who held power in the region since the Celtic invasion of Transylvania in the 4th century BC.

A kingdom of Dacia also existed as early as the first half of the 2nd century BC under King Oroles

Oroles was a Dacian king during the first half of the 2nd century BC.

He successfully opposed the Bastarnae, blocking their invasion into Transylvania.

The Roman historian Trogus Pompeius wrote about king Oroles punishing his soldiers into sleepi ...

. Conflicts with the Bastarnae and the Romans (112–109 BC, 74 BC), against whom they had assisted the Scordisci

The Scordisci ( el, Σκορδίσκοι) were a Celtic Iron Age cultural group centered in the territory of present-day Serbia, at the confluence of the Savus (Sava), Dravus (Drava), Margus (Morava) and Danube rivers. They were historically no ...

and Dardani

The Dardani (; grc, Δαρδάνιοι, Δάρδανοι; la, Dardani) or Dardanians were a Paleo-Balkan people, who lived in a region that was named Dardania after their settlement there. They were among the oldest Balkan peoples, and their ...

, greatly weakened the resources of the Dacians. The Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

historian Trogus Pompeius wrote about king Oroles punishing his soldiers into sleeping at their wives' feet and doing the household chores, because of their initial failure in defeating the invaders. Subsequently, the now "highly motivated" Dacian army defeated the Bastarnae and king Oroles lifted all sanctions.

Burebista

Burebista ( grc, Βυρεβίστας, Βοιρεβίστας) was the king of the Getae and Dacian tribes from 82/61BC to 45/44BC. He was the first king who successfully unified the tribes of the Dacian kingdom, which comprised the area locat ...

(Boerebista), a contemporary of Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

, ruled Geto-Dacian tribes between 82 BC and 44 BC. He thoroughly reorganised the army and attempted to raise the moral standard and obedience of the people by persuading them to cut their vines and give up drinking wine.[Strabo, ''Geography'', VII:3.11] During his reign, the limits of the Dacian Kingdom were extended to their maximum. The Bastarnae and Boii

The Boii (Latin plural, singular ''Boius''; grc, Βόιοι) were a Celtic tribe of the later Iron Age, attested at various times in Cisalpine Gaul (Northern Italy), Pannonia (Hungary), parts of Bavaria, in and around Bohemia (after whom the ...

were conquered, and even the Greek towns of Olbia

Olbia (, ; sc, Terranoa; sdn, Tarranoa) is a city and commune of 60,346 inhabitants (May 2018) in the Italian insular province of Sassari in northeastern Sardinia, Italy, in the historical region of Gallura. Called ''Olbia'' in the Roman age, ...

and Apollonia on the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Roma ...

(''Pontus Euxinus'') recognized Burebista

Burebista ( grc, Βυρεβίστας, Βοιρεβίστας) was the king of the Getae and Dacian tribes from 82/61BC to 45/44BC. He was the first king who successfully unified the tribes of the Dacian kingdom, which comprised the area locat ...

's authority. In 53 BC, Caesar stated that the Dacian territory was on the eastern border of the Hercynian Forest.

Burebista suppressed the indigenous minting of coinages by four major tribal groups, adopting imported or copied Roman denarii as a monetary standard. During his reign, Burebista transferred Geto-Dacians capital from Argedava

Argedava (''Argedauon'', ''Sargedava'', ''Sargedauon'', ''Zargedava'', ''Zargedauon'', grc, Αργεδαυον, Σαργεδαυον) was an important Dacian town mentioned in the Decree of Dionysopolis (48 BC), and potentially located ...

to Sarmizegetusa Regia

Sarmizegetusa Regia, also Sarmisegetusa, Sarmisegethusa, Sarmisegethuza, Ζαρμιζεγεθούσα (''Zarmizegethoúsa'') or Ζερμιζεγεθούση (''Zermizegethoúsē''), was the capital and the most important military, religious an ...

. For at least one and a half centuries, Sarmizegetusa was the Dacians' capital and reached its peak under King Decebalus. The Dacians appeared so formidable that Caesar contemplated an expedition against them, which his death in 44 BC prevented. In the same year, Burebista was murdered, and the kingdom was divided into four (later five) parts under separate rulers.

One of these entities was Cotiso

Cotiso, Cotish or Cotison (flourished c. 30 BC) was a Dacian king who apparently ruled the mountains between Banat and Oltenia (modern-day Romania). Horace calls him king of the Dacians.John T. White, D.D. Oxon, ''The first (-fourth) book of the ...

's state, to whom Augustus betrothed his own five-year-old daughter Julia. He is well known from the line in Horace

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (; 8 December 65 – 27 November 8 BC), known in the English-speaking world as Horace (), was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus (also known as Octavian). The rhetorician Quintilian regarded his ' ...

(''Occidit Daci Cotisonis agmen'', Odes, III. 8. 18).

The Dacians are often mentioned under Augustus, according to whom they were compelled to recognize Roman supremacy. However they were by no means subdued, and in later times to maintain their independence they seized every opportunity to cross the frozen Danube during the winter and ravaging the Roman cities in the province of Moesia

Moesia (; Latin: ''Moesia''; el, Μοισία, Moisía) was an ancient region and later Roman province situated in the Balkans south of the Danube River, which included most of the territory of modern eastern Serbia, Kosovo, north-eastern Alban ...

, which was under Roman occupation.

In fact, this occurred because Burebista

Burebista ( grc, Βυρεβίστας, Βοιρεβίστας) was the king of the Getae and Dacian tribes from 82/61BC to 45/44BC. He was the first king who successfully unified the tribes of the Dacian kingdom, which comprised the area locat ...

's empire split after his death into four and later five smaller states, as Strabo explains, "only recently, when Augustus Caesar

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pri ...

sent an expedition against them, the number of parts into which the empire had been divided was five, though at the time of the insurrection it had been four. Such divisions, to be sure, are only temporary and vary with the times".

During the War of Actium, King Cotiso found himself courted by the two Roman antagonists, Octavian and Mark Antony. Cotiso was in a strong position to dictate terms of any alliance to either of the conflicting parties. Octavian/Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pri ...

worried about the frontier and possible alliance between Mark Antony

Marcus Antonius (14 January 1 August 30 BC), commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic from a constitutional republic into the autoc ...

and the Dacians, and plotted an expedition against Dacia around 35 BC. Despite several small conflicts, no serious campaigns were mounted. King Cotiso chose to ally himself with Mark Antony. According to Alban Dewes Winspear and Lenore Kramp Geweke he "proposed that the war should be fought in Macedonia rather than Epirus. Had his proposal been accepted, the subjection of Antonius might have been less easily accomplished."

According to

According to Appian

Appian of Alexandria (; grc-gre, Ἀππιανὸς Ἀλεξανδρεύς ''Appianòs Alexandreús''; la, Appianus Alexandrinus; ) was a Greek historian with Roman citizenship who flourished during the reigns of Emperors of Rome Trajan, Hadr ...

, Mark Antony is responsible for the statement that Augustus sought to secure the goodwill of Cotiso, king of the Getae (Dacians) by giving him his daughter, and he himself marrying a daughter of Cotiso. According to Suetonius

Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus (), commonly referred to as Suetonius ( ; c. AD 69 – after AD 122), was a Roman historian who wrote during the early Imperial era of the Roman Empire.

His most important surviving work is a set of biographies ...

, Cotiso refused the alliance and joined the party of Mark Antony.[Monumentum ancyranum: the deeds of Augustus, Volume 5, Issue 2, Augustus (Emperor of Rome) The Department of History of the University of Pennsylvania, 1898, page 73] Suetonius

Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus (), commonly referred to as Suetonius ( ; c. AD 69 – after AD 122), was a Roman historian who wrote during the early Imperial era of the Roman Empire.

His most important surviving work is a set of biographies ...

(LXIII, ''Life of Augustus'') says Mark Antony wrote that Augustus betrothed his daughter Julia to marry Cotiso (''M. Antonius scribit primum eum Antonio filio suo despondisse Iuliam, dein Cotisoni Getarum regi'') to create an alliance between the two men. This failed when Cotiso betrayed Augustus. Julia ended up marrying her cousin Marcus Claudius Marcellus. According to Cassius Dio

Lucius Cassius Dio (), also known as Dio Cassius ( ), was a Roman historian and senator of maternal Greek origin. He published 80 volumes of the history on ancient Rome, beginning with the arrival of Aeneas in Italy. The volumes documented the ...

, the story about the proposed marriages is hardly credible and may have been invented by Mark Antony as propaganda to offset his own alliance with Cleopatra.Horace

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (; 8 December 65 – 27 November 8 BC), known in the English-speaking world as Horace (), was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus (also known as Octavian). The rhetorician Quintilian regarded his ' ...

advises him not to worry about Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

's safety, because Cotiso's army has been crushed. In his account of his achievements as emperor, the '' Res Gestae'', Augustus claimed that the Dacians had been subdued. This was not entirely true, because Dacian troops frequently crossed the Danube to ravage parts of Pannonia and Moesia. He may have survived until the campaign of Marcus Vinicius in the Dacian area c.9 BC. Vinicius was the first Roman commander to cross the Danube and invade Dacia itself. Ioana A. Oltean argues that Cotiso probably died at some point during this campaign. He may have been killed in the war.[Ioana A. Oltean, ''Dacia: Landscape, Colonization and Romanization'', Routledge, 7 Aug 2007, p49.] According to Jordanes

Jordanes (), also written as Jordanis or Jornandes, was a 6th-century Eastern Roman bureaucrat widely believed to be of Goths, Gothic descent who became a historian later in life. Late in life he wrote two works, one on Roman history (''Romana ...

Cotiso was succeeded by Comosicus

Comosicus was a Dacian king and high priest who lived in the 1st century BC. The only reference to Comosicus is a passage in the writings of the Roman historian Jordanes.

Sources

Jordanes refers to Burebista as king of Dacia, but then goes on to ...

, about whom nothing is known beyond the name.Marcus Junius Brutus

Marcus Junius Brutus (; ; 85 BC – 23 October 42 BC), often referred to simply as Brutus, was a Roman politician, orator, and the most famous of the assassins of Julius Caesar. After being adopted by a relative, he used the name Quintus Serv ...

. The coins bore the name "Coson" or "Koson" written in Greek lettering. Theodor Mommsen

Christian Matthias Theodor Mommsen (; 30 November 1817 – 1 November 1903) was a German classical scholar, historian, jurist, journalist, politician and archaeologist. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest classicists of the 19th cent ...

argued that Koson was probably a Dacian ally of Brutus, since the imagery was taken from Brutus's coins. Recent scholars have argued that he is very likely to be identical to Cotiso, since "Cotiso is an easy transcription error for Coson. Horace always spells the name with an "n" at the end. Ioana A. Oltean, however, argues that Coson and Cotiso are different people, suggesting that Cotiso was Coson's successor.Burebista

Burebista ( grc, Βυρεβίστας, Βοιρεβίστας) was the king of the Getae and Dacian tribes from 82/61BC to 45/44BC. He was the first king who successfully unified the tribes of the Dacian kingdom, which comprised the area locat ...

as king of Dacia

Dacia (, ; ) was the land inhabited by the Dacians, its core in Transylvania, stretching to the Danube in the south, the Black Sea in the east, and the Tisza in the west. The Carpathian Mountains were located in the middle of Dacia. It thus r ...

, but then goes on to discuss a high priest called Dicineus

Deceneus or Decaeneus (Greek: Δεκαίνεος, ''Dekaineos'') was a priest of Dacia during the reign of Burebista (82/61–45/44 BC). He is mentioned in the near-contemporary Greek '' Geographica'' of Strabo and in the 6th-century Latin ''Getic ...

who taught the Dacians astronomy and whose wisdom was revered. He then says that "after the death of Dicienus, they held Comosicus in almost equal honour, because he was not inferior in knowledge. By reason of his wisdom he was accounted their priest and king, and he judged the people with the greatest uprightness. When he too had departed Coryllus ascended the throne as king of the Goths etae

Sukree Etae ( th, สุกรี อีแต, , born 22 January 1986 in Thailand) is a professional footballer from Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southea ...

and for forty years ruled his people in Dacia."

King Scorilo was Comosicus

Comosicus was a Dacian king and high priest who lived in the 1st century BC. The only reference to Comosicus is a passage in the writings of the Roman historian Jordanes.

Sources

Jordanes refers to Burebista as king of Dacia, but then goes on to ...

' successor and may have been the father of Decebalus. The Roman historian Jordanes

Jordanes (), also written as Jordanis or Jornandes, was a 6th-century Eastern Roman bureaucrat widely believed to be of Goths, Gothic descent who became a historian later in life. Late in life he wrote two works, one on Roman history (''Romana ...

lists a series of Dacian kings before Decebalus, placing a ruler called "Coryllus" between Comosicus

Comosicus was a Dacian king and high priest who lived in the 1st century BC. The only reference to Comosicus is a passage in the writings of the Roman historian Jordanes.

Sources

Jordanes refers to Burebista as king of Dacia, but then goes on to ...

and the independently attested Duras, who preceded Decebalus as king. Coryllus is supposed to have presided over a long peaceful 40-year rule, however, the name Coryllus is not mentioned by any other historian, and it has been argued that it "is a misspelling of Scorilo, a relatively common Dacian name". On this basis, Coryllus has been equated with the Scorilo named on an ancient Dacian pot bearing the words “Decebalus per Scorilo”. Though far from certain, this has also been translated as "Decebalus son of Scorilo". If so, this might mean that Decebalus was the son of Scorilo, with Duras possibly being either an older son or a brother of Scorilo. A Dacian king (''dux Dacorum'') called Scorilo is also mentioned by Frontinus, who says he was in power during a period of turmoil in Rome.[Bǎrbulescu, Mihai, et al, ''The History of Transylvania: (Until 1541)'', Romanian Cultural Institute, 2005, pp.87–9.] From this evidence and references to Dacian kings elsewhere, it is suggested that Scorilo probably ruled from the 30s or 40s AD through to 69–70.Moesia

Moesia (; Latin: ''Moesia''; el, Μοισία, Moisía) was an ancient region and later Roman province situated in the Balkans south of the Danube River, which included most of the territory of modern eastern Serbia, Kosovo, north-eastern Alban ...

. The emperors Tiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus (; 16 November 42 BC – 16 March AD 37) was the second Roman emperor. He reigned from AD 14 until 37, succeeding his stepfather, the first Roman emperor Augustus. Tiberius was born in Rome in 42 BC. His father ...

and Caligula

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (31 August 12 – 24 January 41), better known by his nickname Caligula (), was the third Roman emperor, ruling from 37 until his assassination in 41. He was the son of the popular Roman general Germanicu ...

solved this problem by paying protection money to the Dacians in the form of annual subsidies. This policy appears to have coincided with the reign of King Scorilo. Scorilo's brother was apparently held captive for a period in Rome, but was released in exchange for a promise that the Dacians would not intervene in Rome's volatile power-politics.[Ion Grumeza, ''Dacia: Land of Transylvania, Cornerstone of Ancient Eastern Europe'', University Press of America, 2009, p.154-5.] During the reign of Emperor Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), was the fifth Roman emperor and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 un ...

, troops were withdrawn from the Dacian border, leaving the empire vulnerable. When Nero was overthrown in 69, the empire was plunged into turmoil in the Year of Four Emperors

A year or annus is the orbital period of a planetary body, for example, the Earth, moving in its orbit around the Sun. Due to the Earth's axial tilt, the course of a year sees the passing of the seasons, marked by change in weather, the hour ...

. The Dacians appear to have tried to take advantage of the situation to launch an invasion of Moesia in alliance with the Sarmatian Roxolani

The Roxolani or Rhoxolāni ( grc, Ροξολανοι , ; la, Rhoxolānī) were a Sarmatian people documented between the 2nd century BC and the 4th century AD, first east of the Borysthenes (Dnieper) on the coast of Lake Maeotis (Sea of Azov), a ...

. The invasion was ill-timed. Licinius Mucianus, a supporter of Vespasian

Vespasian (; la, Vespasianus ; 17 November AD 9 – 23/24 June 79) was a Roman emperor who reigned from AD 69 to 79. The fourth and last emperor who reigned in the Year of the Four Emperors, he founded the Flavian dynasty that ruled the Empi ...

, was advancing with an army through Moesia towards Rome to overthrow Vitellius. The Dacians unexpectedly encountered his forces and were pushed back, suffering a major defeat. Scorilo appears to have died around this time, perhaps during the campaign.

King Duras ruled between the years AD 69 and 87, during the time that

King Duras ruled between the years AD 69 and 87, during the time that Domitian

Domitian (; la, Domitianus; 24 October 51 – 18 September 96) was a Roman emperor who reigned from 81 to 96. The son of Vespasian and the younger brother of Titus, his two predecessors on the throne, he was the last member of the Flavi ...

ruled the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

. He was one of a series of rulers following the Great King Burebista

Burebista ( grc, Βυρεβίστας, Βοιρεβίστας) was the king of the Getae and Dacian tribes from 82/61BC to 45/44BC. He was the first king who successfully unified the tribes of the Dacian kingdom, which comprised the area locat ...

. Duras' immediate successor was Decebalus. Duras may be identical to the "Diurpaneus" (or "Dorpaneus") identified in Roman sources as the Dacian leader who, in the winter of 85, ravaged the southern banks of the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

, which the Romans defended for many years. Many authors refer to him as "Duras-Diurpaneus". Other scholars argue that Duras and Diurpaneus are different individuals, or that Diurpaneus is identical to Decebalus.

The Roman governor of Moesia, Oppius Sabinus

Gaius Oppius Sabinus (died AD 85) was a Roman Senator who held at least one office in the emperor's service. He was ordinary consul in the year 84 as the colleague of emperor Domitian.

Sabinus was probably the son or nephew of Spurius Oppius, ...

, raised an army and went to war with the Dacians following the Dacian (Getae) raids into Roman territory.[Brian W. Jones, ''The Emperor Domitian'', Routledge, London, 1992, p.138] Diurpaneus and his people defeated and decapitated Oppius Sabinus. When news of the defeat reached Rome, the citizens became fearful that the conquering enemy would invade and spread destruction further into the Empire. Because of this fear, Domitian was obliged to move with his entire army into Illyria

In classical antiquity, Illyria (; grc, Ἰλλυρία, ''Illyría'' or , ''Illyrís''; la, Illyria, ''Illyricum'') was a region in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula inhabited by numerous tribes of people collectively known as the Illyr ...

and Moesia

Moesia (; Latin: ''Moesia''; el, Μοισία, Moisía) was an ancient region and later Roman province situated in the Balkans south of the Danube River, which included most of the territory of modern eastern Serbia, Kosovo, north-eastern Alban ...

, the latter of which was now split into Upper and Lower regions. He ordered his commander Cornelius Fuscus to cross the Danube.Trajan

Trajan ( ; la, Caesar Nerva Traianus; 18 September 539/11 August 117) was Roman emperor from 98 to 117. Officially declared ''optimus princeps'' ("best ruler") by the senate, Trajan is remembered as a successful soldier-emperor who presi ...

turned his attention to Dacia, it had been on the Roman agenda since before the days of Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

when a Roman army had been beaten at the Battle of Histria

The Battle of Histria, c. 62–61 B.C., was fought between the Bastarnae peoples of Scythia Minor and the Roman Consul (63 B.C.) Gaius Antonius Hybrida. The Bastarnae emerged victorious from the battle after successfully launching a surprise atta ...

.

From AD 85 to 89, the Dacians under Decebalus were engaged in two wars with the Romans.

In AD 85, the Dacians had swarmed over the Danube and pillaged Moesia. In AD 87, the Roman troops sent by the Emperor Domitian against them under Cornelius Fuscus, were defeated and Cornelius Fuscus was killed by the Dacians by authority of their ruler, Diurpaneus. After this victory, Diurpaneus took the name of ''Decebalus'', but the Romans were victorious in the Battle of Tapae in AD 88 and a truce was drawn up .

From AD 85 to 89, the Dacians under Decebalus were engaged in two wars with the Romans.

In AD 85, the Dacians had swarmed over the Danube and pillaged Moesia. In AD 87, the Roman troops sent by the Emperor Domitian against them under Cornelius Fuscus, were defeated and Cornelius Fuscus was killed by the Dacians by authority of their ruler, Diurpaneus. After this victory, Diurpaneus took the name of ''Decebalus'', but the Romans were victorious in the Battle of Tapae in AD 88 and a truce was drawn up .Tettius Julianus

Lucius Tettius Julianus was a Roman general who held a number of imperial appointments during the Flavian dynasty. He was suffect consul for the '' nundinium'' of May–June 83 with Terentius Strabo Erucius Homullus as his colleague.

He may be ...

, gained a significant advantage, but were obligated to make a humiliating peace following the defeat of Domitian

Domitian (; la, Domitianus; 24 October 51 – 18 September 96) was a Roman emperor who reigned from 81 to 96. The son of Vespasian and the younger brother of Titus, his two predecessors on the throne, he was the last member of the Flavi ...

by the Marcomanni

The Marcomanni were a Germanic people

*

*

*

that established a powerful kingdom north of the Danube, somewhere near modern Bohemia, during the peak of power of the nearby Roman Empire. According to Tacitus and Strabo, they were Suebian.

Origin

...

, leaving the Dacians effectively independent. Decebalus was given the status of "king client to Rome", receiving military instructors, craftsmen and money from Rome.

To increase the glory of his reign, restore the finances of Rome, and end a treaty perceived as humiliating, Trajan resolved on the conquest of Dacia, the capture of the famous Treasure of Decebalus, and control over the Dacian gold mines of Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the Ap ...

. The result of his first campaign (101–102) was the siege of the Dacian capital Sarmizegethusa and the occupation of part of the country. Emperor Trajan recommenced hostilities against Dacia and, following an uncertain number of battles, and with Trajan's troops pressing towards the Dacian capital Sarmizegethusa

Sarmizegetusa Regia, also Sarmisegetusa, Sarmisegethusa, Sarmisegethuza, Ζαρμιζεγεθούσα (''Zarmizegethoúsa'') or Ζερμιζεγεθούση (''Zermizegethoúsē''), was the capital and the most important military, religious an ...

, Decebalus once more sought terms.

Decebalus rebuilt his power over the following years and attacked Roman garrisons again in AD 105. In response Trajan again marched into Dacia, attacking the Dacian capital in the Siege of Sarmizegethusa

The Battle of Sarmizegetusa (also spelled ''Sarmizegethuza'') was a siege of Sarmizegetusa, the capital of Dacia, fought in 106 between the army of the Roman Emperor Trajan, and the Dacians led by King Decebalus.

Background

Because of the th ...

, and razing it to the ground, the defeated Dacian king Decebalus committed suicide to avoid capture. In the following years, a new city was built on the ruins of the Dacian capital named Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa

Colonia Ulpia Traiana Augusta Dacica Sarmizegetusa was the capital and the largest city of Roman Dacia, later named ''Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa'' after the former Dacian capital, located some 40 km away. Built on the ground of a camp of t ...

. With part of Dacia quelled as the Roman province

The Roman provinces (Latin: ''provincia'', pl. ''provinciae'') were the administrative regions of Ancient Rome outside Roman Italy that were controlled by the Romans under the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire. Each province was rule ...

Dacia Traiana. Trajan subsequently invaded the Parthian empire to the east. His conquests brought the Roman Empire to its greatest extent. Rome's borders in the east were governed indirectly in this period, through a system of client states, which led to less direct campaigning than in the west.

The weapon most associated with the Dacian forces that fought against Trajan's army during his invasions of Dacia was the falx, a single-edged scythe-like weapon. The falx was able to inflict horrible wounds on opponents, easily disabling or killing the heavily armored Roman legionaries that they faced. This weapon, more so than any other single factor, forced the Roman army to adopt previously unused or modified equipment to suit the conditions on the Dacian battlefield.

Some of the history of the war is given by Cassius Dio

Lucius Cassius Dio (), also known as Dio Cassius ( ), was a Roman historian and senator of maternal Greek origin. He published 80 volumes of the history on ancient Rome, beginning with the arrival of Aeneas in Italy. The volumes documented the ...

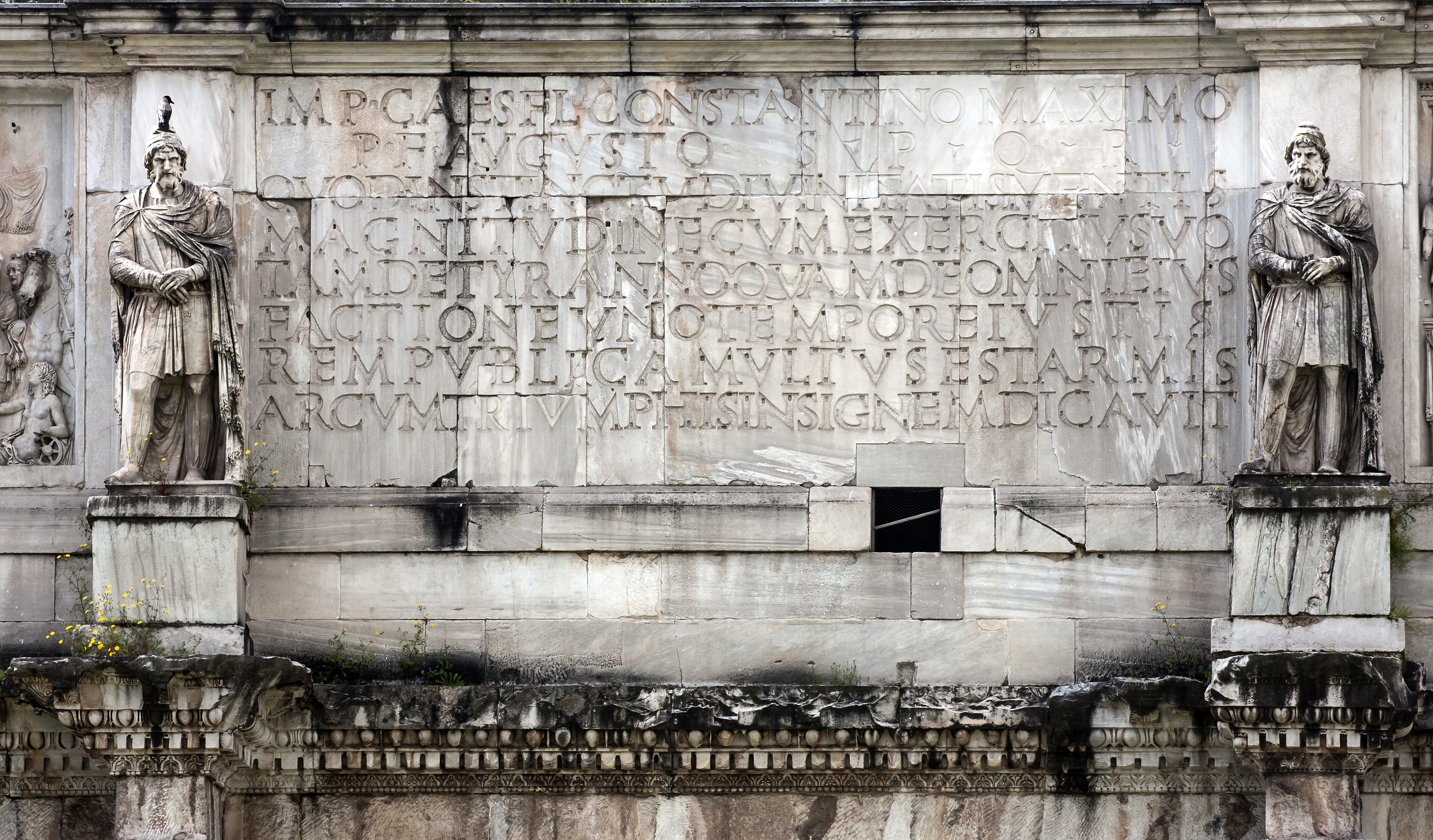

. Trajan erected the Column of Trajan

Trajan's Column ( it, Colonna Traiana, la, Columna Traiani) is a Roman triumphal column in Rome, Italy, that commemorates Roman emperor Trajan's victory in the Trajan's Dacian Wars, Dacian Wars. It was probably constructed under the supervision o ...

in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

to commemorate his victory.

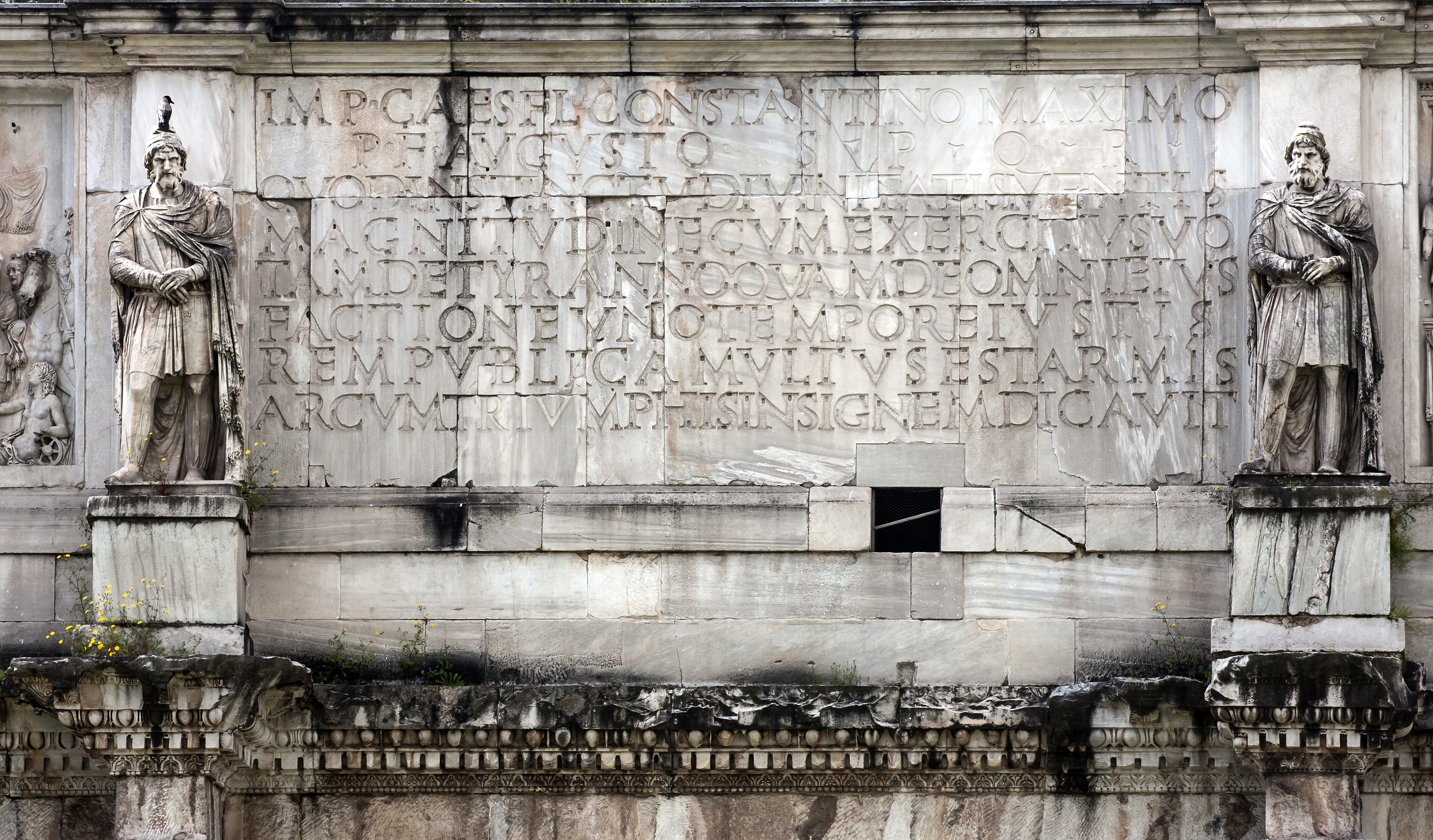

Roman Dacia (106–275 AD)

Roman Dacia, also known as Dacia Felix, was organized as an

Roman Dacia, also known as Dacia Felix, was organized as an imperial province

An imperial province was a Roman province during the Principate where the Roman Emperor had the sole right to appoint the governor (''legatus Augusti pro praetore''). These provinces were often the strategically located border provinces.

The pro ...

on the borders of the empire. It is estimated that the population of Roman Dacia ranged from 650,000 to 1,200,000. The area was the focus of a massive Roman colonization. New mines were opened and ore extraction intensified, while agriculture, stock breeding, and commerce flourished in the province. Roman Dacia was of great importance to the military stationed throughout the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

and became an urban province, with about ten cities known and all of them originating from old military camps

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

. Eight of these held the highest rank of '' colonia''. Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa

Colonia Ulpia Traiana Augusta Dacica Sarmizegetusa was the capital and the largest city of Roman Dacia, later named ''Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa'' after the former Dacian capital, located some 40 km away. Built on the ground of a camp of t ...

was the financial, religious, and legislative center and where the imperial ''procurator'' (finance officer) had his seat, while Apulum was Roman Dacia's military center. The region was soon was settled by the retired veterans who had served in the Dacian Wars, principally the Fifth (''Macedonia''), Ninth (''Claudia''), and Fourteenth (''Gemina'') legions.

While it is certain that colonists in large numbers were imported from all over the empire to settle in Roman Dacia, this appears to be true for the newly created Roman towns only. The lack of epigraphic evidence for native Dacian names in the towns suggests an urban–rural split between Roman multi-ethnic urban centres and the native Dacian rural population. On at least two occasions the Dacians rebelled against Roman authority: first in 117 AD, which caused the return of Trajan from the east, and in 158 AD when they were put down by Marcus Statius Priscus.

Some scholars have used the lack of '' civitates peregrinae'' in Roman Dacia, where indigenous peoples were organised into native townships, as evidence for the Roman depopulation of Dacia. Prior to its incorporation into the empire, Dacia was a kingdom ruled by one king, and did not possess a regional tribal structure that could easily be turned into the Roman ''civitas'' system as used successfully in other provinces of the empire.

As per usual Roman practice, Dacian males were recruited into auxiliary units and dispatched across the empire, from the eastern provinces to

As per usual Roman practice, Dacian males were recruited into auxiliary units and dispatched across the empire, from the eastern provinces to Britannia

Britannia () is the national personification of Britain as a helmeted female warrior holding a trident and shield. An image first used in classical antiquity, the Latin ''Britannia'' was the name variously applied to the British Isles, Great ...

. The ''Vexillation Dacorum Parthica'' accompanied the emperor Septimius Severus during his Parthia

Parthia ( peo, 𐎱𐎼𐎰𐎺 ''Parθava''; xpr, 𐭐𐭓𐭕𐭅 ''Parθaw''; pal, 𐭯𐭫𐭮𐭥𐭡𐭥 ''Pahlaw'') is a historical region located in northeastern Greater Iran. It was conquered and subjugated by the empire of the Med ...

n expedition, while the ''cohort I Ulpia Dacorum'' was posted to Cappadocia

Cappadocia or Capadocia (; tr, Kapadokya), is a historical region in Central Anatolia, Turkey. It largely is in the provinces Nevşehir, Kayseri, Aksaray, Kırşehir, Sivas and Niğde.

According to Herodotus, in the time of the Ionian Revo ...

. Others included the ''II Aurelia Dacorum'' in Pannonia Superior

Pannonia Superior, lit. Upper Pannonia, was a province of the Roman Empire. Its capital was Carnuntum. It was one on the border provinces on the Danube. It was formed in the year 103 AD by Emperor Trajan who divided the former province of Pannon ...

, the ''cohort I Aelia Dacorum'' in Roman Britain, and the ''II Augusta Dacorum milliaria'' in Moesia Inferior. There are a number of preserved relics originating from ''cohort I Aelia Dacorum'', with one inscription describing the '' sica'', a distinctive Dacian weapon. In inscriptions the Dacian soldiers are described as ''natione Dacus''. These could refer to individuals who were native Dacians, Romanized Dacians, colonists who had moved to Dacia, or their descendants. Numerous Roman military diplomas issued for Dacian soldiers discovered after 1990 indicate that veterans preferred to return to their place of origin; per usual Roman practice, these veterans were given Roman citizenship upon their discharge.

In an attempt to fill the cities, cultivate the fields, and mine the ore, a large-scale attempt at colonization took place with colonists coming in "from all over the Roman world". The colonists were a heterogeneous mix: of the some 3,000 names preserved in inscriptions found by the 1990s, 74% (c. 2,200) were Latin, 14% (c. 420) were Greek, 4% (c. 120) were Illyrian, 2.3% (c. 70) were Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

* Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Fo ...

, 2% (c. 60) were Thraco-Dacian

The linguistic classification of the ancient Thracian language has long been a matter of contention and uncertainty, and there are widely varying hypotheses regarding its position among other Paleo-Balkan languages. It is not contested, however, t ...

, and another 2% (c. 60) were Semites from Syria. Regardless of their place of origin, the settlers and colonists were a physical manifestation of Roman civilisation and imperial culture, bringing with them the most effective Romanizing mechanism: the use of Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

as the new ''lingua franca

A lingua franca (; ; for plurals see ), also known as a bridge language, common language, trade language, auxiliary language, vehicular language, or link language, is a language systematically used to make communication possible between groups ...

''.

The first settlement at Sarmizegetusa was made up of Roman citizens who had retired from their legions. Based upon the location of names scattered throughout the province, it has been argued that, although places of origin are hardly ever noted in epigraphs, a large percentage of colonists originated from Noricum and western Pannonia. Specialist miners (the Pirusti tribesmen) were brought in from Dalmatia.

Although the Romans conquered and destroyed the ancient Kingdom of Dacia, a large remainder of the land remained outside of Roman Imperial authority. Additionally, the conquest changed the balance of power in the region and was the catalyst for a renewed alliance of Germanic and Celtic tribes and kingdoms against the Roman Empire. However, the material advantages of the Roman Imperial system was attractive to the surviving aristocracy. Afterwards, many of the Dacians became Romanised (see also

Although the Romans conquered and destroyed the ancient Kingdom of Dacia, a large remainder of the land remained outside of Roman Imperial authority. Additionally, the conquest changed the balance of power in the region and was the catalyst for a renewed alliance of Germanic and Celtic tribes and kingdoms against the Roman Empire. However, the material advantages of the Roman Imperial system was attractive to the surviving aristocracy. Afterwards, many of the Dacians became Romanised (see also Origin of Romanians

Several theories address the issue of the origin of the Romanians. The Romanian language descends from the Vulgar Latin dialects spoken in the Roman provinces north of the "Jireček Line" (a proposed notional line separating the predominantly ...

). In AD 183, war broke out in Dacia: few details are available, but it appears two future contenders for the throne of emperor Commodus

Commodus (; 31 August 161 – 31 December 192) was a Roman emperor who ruled from 177 to 192. He served jointly with his father Marcus Aurelius from 176 until the latter's death in 180, and thereafter he reigned alone until his assassination. ...

, Clodius Albinus

Decimus Clodius Albinus ( 150 – 19 February 197) was a Roman imperial pretender between 193 and 197. He was proclaimed emperor by the legions in Britain and Hispania (the Iberian Peninsula, comprising modern Spain and Portugal) after the murder ...

and Pescennius Niger

Gaius Pescennius Niger (c. 135 – 194) was Roman Emperor from 193 to 194 during the Year of the Five Emperors. He claimed the imperial throne in response to the murder of Pertinax and the elevation of Didius Julianus, but was defeated by a riva ...

, both distinguished themselves in the campaign.

According to Lactantius

Lucius Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius (c. 250 – c. 325) was an early Christian author who became an advisor to Roman emperor, Constantine I, guiding his Christian religious policy in its initial stages of emergence, and a tutor to his son Cr ...

, the Roman emperor Decius

Gaius Messius Quintus Traianus Decius ( 201 ADJune 251 AD), sometimes translated as Trajan Decius or Decius, was the emperor of the Roman Empire from 249 to 251.

A distinguished politician during the reign of Philip the Arab, Decius was procla ...

(AD 249–251) had to restore Roman Dacia from the Carpo-Dacians

The Carpi or Carpiani were a Dacian tribe that resided in the eastern parts of modern Romania in the historical region of Moldavia from no later than c. AD 140 and until at least AD 318.

The ethnic affiliation of the Carpi remains disputed, as ...

of Zosimus Zosimus, Zosimos, Zosima or Zosimas may refer to:

People

*

* Rufus and Zosimus (died 107), Christian saints

* Zosimus (martyr) (died 110), Christian martyr who was executed in Umbria, Italy

* Zosimos of Panopolis, also known as ''Zosimus Alchemi ...

"having undertaken an expedition against the Carpi, who had then possessed themselves of Dacia and Moesia".

Even so, the Germanic and Celtic kingdoms, particularly the Gothic tribes

The Goths ( got, 𐌲𐌿𐍄𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰, translit=''Gutþiuda''; la, Gothi, grc-gre, Γότθοι, Gótthoi) were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Europe. ...

, slowly moved toward the Dacian borders, and within a generation were making assaults on the province. Ultimately, the Goths

The Goths ( got, 𐌲𐌿𐍄𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰, translit=''Gutþiuda''; la, Gothi, grc-gre, Γότθοι, Gótthoi) were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Europe ...

succeeded in dislodging the Romans and restoring the "independence" of Dacia following Emperor Aurelian

Aurelian ( la, Lucius Domitius Aurelianus; 9 September 214 October 275) was a Roman emperor, who reigned during the Crisis of the Third Century, from 270 to 275. As emperor, he won an unprecedented series of military victories which reunited t ...

's withdrawal, in 275.

In AD 268–269, at Naissus, Claudius II (Gothicus Maximus) obtained a decisive victory over the Goths. Since at that time Romans were still occupying Roman Dacia

Roman Dacia ( ; also known as Dacia Traiana, ; or Dacia Felix, 'Fertile/Happy Dacia') was a province of the Roman Empire from 106 to 271–275 AD. Its territory consisted of what are now the regions of Oltenia, Transylvania and Banat (today ...

it is assumed that the Goths didn't cross the Danube from the Roman province. The Goths who survived their defeat didn't even attempt to escape through Dacia, but through Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to t ...

. At the boundaries of Roman Dacia

Roman Dacia ( ; also known as Dacia Traiana, ; or Dacia Felix, 'Fertile/Happy Dacia') was a province of the Roman Empire from 106 to 271–275 AD. Its territory consisted of what are now the regions of Oltenia, Transylvania and Banat (today ...

, Carpi

Carpi may refer to:

Places

* Carpi, Emilia-Romagna, a large town in the province of Modena, central Italy

* Carpi (Africa), a city and former diocese of Roman Africa, now a Latin Catholic titular bishopric

People

* Carpi (people), an ancie ...

(Free Dacians

The so-called Free Dacians ( ro, Daci liberi) is the name given by some modern historians to those Dacians who putatively remained outside, or emigrated from, the Roman Empire after the emperor Trajan's Dacian Wars (AD 101-6). Dio Cassius named th ...

) were still strong enough to sustain five battles in eight years against the Romans from AD 301–308. Roman Dacia was left in AD 275 by the Romans, to the Carpi again, and not to the Goths. There were still Dacians in AD 336, against whom Constantine the Great

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to Constantine the Great and Christianity, convert to Christiani ...

fought.

The province was abandoned by Roman troops, and, according to the ''Breviarium historiae Romanae'' by Eutropius, Roman citizens "from the towns and lands of Dacia" were resettled to the interior of Moesia. Under Diocletian

Diocletian (; la, Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus, grc, Διοκλητιανός, Diokletianós; c. 242/245 – 311/312), nicknamed ''Iovius'', was Roman emperor from 284 until his abdication in 305. He was born Gaius Valerius Diocles ...

, c. AD 296, in order to defend the Roman border, fortifications were erected by the Romans on both banks of the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

.

Constantinian reconquest of Dacia

In 328 the emperor

In 328 the emperor Constantine the Great

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to Constantine the Great and Christianity, convert to Christiani ...

inaugurated the Constantine's Bridge (Danube) at Sucidava, (today Celei in Romania) in hopes of reconquering Dacia

Dacia (, ; ) was the land inhabited by the Dacians, its core in Transylvania, stretching to the Danube in the south, the Black Sea in the east, and the Tisza in the west. The Carpathian Mountains were located in the middle of Dacia. It thus r ...

, a province that had been abandoned under Aurelian. In the late winter of 332, Constantine campaigned with the Sarmatians against the Goths

The Goths ( got, 𐌲𐌿𐍄𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰, translit=''Gutþiuda''; la, Gothi, grc-gre, Γότθοι, Gótthoi) were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Europe ...

. The weather and lack of food cost the Goths dearly: reportedly, nearly one hundred thousand died before they submitted to Rome. In celebration of this victory Constantine took the title ''Gothicus Maximus'' and claimed the subjugated territory as the new province of Gothia. In 334, after Sarmatian commoners had overthrown their leaders, Constantine led a campaign against the tribe. He won a victory in the war and extended his control over the region, as remains of camps and fortifications in the region indicate. Constantine resettled some Sarmatian exiles as farmers in Illyrian and Roman districts, and conscripted the rest into the army. The new frontier in Dacia was along the Brazda lui Novac

Brazda lui Novac is a Roman ''limes'' in present-day Romania, known also as Constantine's Wall. It is believed by some historians like Alexandru Madgearu to border Ripa Gothica.

The vallum of Brazda lui Novac starts from Drobeta, nowadays it is ...

line supported by Castra of Hinova

The castra of Hinova was a Late Roman fort built north of the Lower Danube in the 3rd or 4th century AD.

The fort was destroyed for the first time between 378 - 379 AD. In the beginning of 5th century the fort was destroyed by Huns and fina ...

, Rusidava

Rusidava (or Zusidava) was a Dacian town mentioned in Tabula Peutingeriana between Acidava and Pons Aluti, today's Drăgășani, Vâlcea County, Romania.

See also

* Dacian davae

* List of ancient cities in Thrace and Dacia

* Dacia

* Roman Da ...

and Castra of Pietroasele

The castra of Pietroasele was one of the castra, forts erected by Emperor Constantine the Great on the north bank of the river Danube after his victory over the Goths in 328. It was abandoned in the same century. The ruins of the ''castra'' are lo ...

. The limes passed to the north of Castra of Tirighina-Bărboși

It was a fort in the Roman province of Moesia. Here were found coins dating from the rule of Augustus (63 BC – 14 AD) through to Nero (37 AD – 68 AD).

See also

*List of castra

Castra (Latin, singular castrum) were military forts of vari ...

and ended at Sasyk Lagoon

__NOTOC__

Sasyk, or Kunduk ( uk, Сасик, Кундук – transcribed as previous, ro, Limanul Sasic, Conduc, tr, Sasık Gölü, Kunduk Gölü), is a lagoon or liman in southern Ukraine, near the Danube Delta. It is a Ramsar listed wetland ...

near the Dniester

The Dniester, ; rus, Дне́стр, links=1, Dnéstr, ˈdⁿʲestr; ro, Nistru; grc, Τύρᾱς, Tyrās, ; la, Tyrās, la, Danaster, label=none, ) ( ,) is a transboundary river in Eastern Europe. It runs first through Ukraine and th ...

River. Constantine took the title ''Dacicus maximus'' in 336. Some Roman territories north of the Danube resisted until Justinian

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovat ...

.

Victohali The Victohali were a people of Late Antiquity who lived north of the Lower Danube. In Greek their name is ''Biktoa'' or ''Biktoloi''. They were possibly a Germanic people, and it has been suggested that they were one of the tribes of the Vandals.

T ...

, Taifals, and Thervingians are tribes mentioned for inhabiting Dacia in 350, after the Romans left. Archeological evidence suggests that Gepids

The Gepids, ( la, Gepidae, Gipedae, grc, Γήπαιδες) were an East Germanic tribe who lived in the area of modern Romania, Hungary and Serbia, roughly between the Tisza, Sava and Carpathian Mountains. They were said to share the religion a ...

were disputing Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the Ap ...

with Taifals and Tervingians. Taifals, once independent from Gothia became federati of the Romans, from whom they obtained the right to settle Oltenia

Oltenia (, also called Lesser Wallachia in antiquated versions, with the alternative Latin names ''Wallachia Minor'', ''Wallachia Alutana'', ''Wallachia Caesarea'' between 1718 and 1739) is a historical province and geographical region of Romania ...

.

In 376 the region was conquered by Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

, who kept it until the death of Attila

Attila (, ; ), frequently called Attila the Hun, was the ruler of the Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European traditio ...

in 453. The Gepid tribe, ruled by Ardaric, used it as their base, until in 566 it was destroyed by Lombards

The Lombards () or Langobards ( la, Langobardi) were a Germanic people who ruled most of the Italian Peninsula from 568 to 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the ''History of the Lombards'' (written between 787 and ...

. Lombards abandoned the country and the Avars (second half of the 6th century) dominated the region for 230 years, until their kingdom was destroyed by Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first Holy ...

in 791. At the same time, Slavic people

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

arrived.

The ''Hellenic chronicle'' could possibly qualify to the first testimony of Romanians in Pannonia and Eastern Europe during the time of Attila, implying that the formation of Proto-Romanian (or Common Romanian) from Vulgar Latin started in the 5th century. The poem '' Nibelungenlied'' from the early 1200s mentions one "duke Ramunc of Wallachia" in the retinue of Attila the Hun

Attila (, ; ), frequently called Attila the Hun, was the ruler of the Huns from 434 until his death in March 453. He was also the leader of a tribal empire consisting of Huns, Ostrogoths, Alans, and Bulgars, among others, in Central and Ea ...

. The words ''"torna, torna fratre"'' (return, return brother) recorded in connection with a Roman campaign across the Balkan Mountains by Theophylact Simocatta and Theophanes the Confessor

Theophanes the Confessor ( el, Θεοφάνης Ὁμολογητής; c. 758/760 – 12 March 817/818) was a member of the Byzantine aristocracy who became a monk and chronicler. He served in the court of Emperor Leo IV the Khazar before taking u ...

evidence the development of a Romance language in the late 6th century. The words were shouted "in native parlance" by a local soldier in 587 or 588. The 11th-century Persian writer, Gardizi, wrote about a Christian people "from the Roman Empire" called ''N.n.d.r'', inhabiting the lands along the Danube. He describes them as "more numerous than the Hungarians, but weaker". Historian Adolf Armbruster identified this people as the Romanians. Hungarian historiography identifies this people as the Bulgarians

Bulgarians ( bg, българи, Bǎlgari, ) are a nation and South Slavic ethnic group native to Bulgaria and the rest of Southeast Europe.

Etymology

Bulgarians derive their ethnonym from the Bulgars. Their name is not completely understo ...

.

Name

The Dacians were known as ''Geta'' (plural ''Getae'') in Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

writings, and as ''Dacus'' (plural ''Daci'') or ''Getae'' in Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

documents, but also as ''Dagae'' and ''Gaete'' as depicted on the late Roman map '' Tabula Peutingeriana''. It was Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria ( Italy). He is known f ...

who first used the ethnonym

An ethnonym () is a name applied to a given ethnic group. Ethnonyms can be divided into two categories: exonyms (whose name of the ethnic group has been created by another group of people) and autonyms, or endonyms (whose name is created and used ...

''Getae'' in his ''Histories

Histories or, in Latin, Historiae may refer to:

* the plural of history

* ''Histories'' (Herodotus), by Herodotus

* ''The Histories'', by Timaeus

* ''The Histories'' (Polybius), by Polybius

* ''Histories'' by Gaius Sallustius Crispus (Sallust), ...

''. In Greek and Latin, in the writings of Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

, Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

, and Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic '' ...

, the people became known as 'the Dacians'. Getae and Dacians were interchangeable terms, or used with some confusion by the Greeks. Latin poets often used the name ''Getae''. Vergil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: th ...

called them ''Getae'' four times, and ''Daci'' once, Lucian

Lucian of Samosata, '; la, Lucianus Samosatensis ( 125 – after 180) was a Hellenized Syrian satirist, rhetorician and pamphleteer

Pamphleteer is a historical term for someone who creates or distributes pamphlets, unbound (and therefore ...

''Getae'' three times and ''Daci'' twice, Horace

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (; 8 December 65 – 27 November 8 BC), known in the English-speaking world as Horace (), was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus (also known as Octavian). The rhetorician Quintilian regarded his ' ...

named them ''Getae'' twice and ''Daci'' five times, while Juvenal

Decimus Junius Juvenalis (), known in English as Juvenal ( ), was a Roman poet active in the late first and early second century CE. He is the author of the collection of satirical poems known as the ''Satires''. The details of Juvenal's life ...

one time ''Getae'' and two times ''Daci''. In AD 113, Hadrian

Hadrian (; la, Caesar Trâiānus Hadriānus ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. He was born in Italica (close to modern Santiponce in Spain), a Roman ''municipium'' founded by Italic settlers in Hispania B ...

used the poetic term ''Getae'' for the Dacians. Modern historians prefer to use the name ''Geto-Dacians''. Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

describes the Getae and Dacians as distinct but cognate tribes. This distinction refers to the regions they occupied. Strabo and Pliny the Elder also state that Getae and Dacians spoke the same language.

By contrast, the name of ''Dacians'', whatever the origin of the name, was used by the more western tribes who adjoined the Pannonians and therefore first became known to the Romans. According to Strabo's ''Geographica

The ''Geographica'' (Ancient Greek: Γεωγραφικά ''Geōgraphiká''), or ''Geography'', is an encyclopedia of geographical knowledge, consisting of 17 'books', written in Ancient Greek, Greek and attributed to Strabo, an educated citizen ...

'', the original name of the Dacians was "''Daoi''". The name Daoi (one of the ancient Geto-Dacian tribes) was certainly adopted by foreign observers to designate all the inhabitants of the countries north of Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

that had not yet been conquered by Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

or Rome.

The ethnographic name ''Daci'' is found under various forms within ancient sources. Greeks used the forms "''Dakoi''" (Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

, Dio Cassius