Cinnamoyl-CoA Reductase on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Cinnamoyl-CoA reductase (), systematically named cinnamaldehyde:NADP+ oxidoreductase (CoA-cinnamoylating) but commonly referred to by the acronym CCR, is an

The

The

CCR is especially important because it acts as a final control point for regulation of metabolic flux toward the monolignols and therefore toward lignin as well; prior to this reduction step, the cinnamoyl-CoA's can still enter into other expansive specialized metabolic pathways. For example, feruloyl-CoA is a precursor of the

CCR is especially important because it acts as a final control point for regulation of metabolic flux toward the monolignols and therefore toward lignin as well; prior to this reduction step, the cinnamoyl-CoA's can still enter into other expansive specialized metabolic pathways. For example, feruloyl-CoA is a precursor of the

enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products. A ...

that catalyzes the reduction of a substituted cinnamoyl-CoA

Cinnamoyl-Coenzyme A is an intermediate in the phenylpropanoids metabolic pathway.

Enzymes using Cinnamoyl-Coenzyme A

* Cinnamoyl-CoA reductase, an enzyme that catalyzes the chemical reaction cinnamaldehyde + CoA + NADP+ → cinnamoyl-CoA + NADP ...

to its corresponding cinnamaldehyde

Cinnamaldehyde is an organic compound with the formula(C9H8O) C6H5CH=CHCHO. Occurring naturally as predominantly the ''trans'' (''E'') isomer, it gives cinnamon its flavor and odor. It is a phenylpropanoid that is naturally synthesized by the shik ...

, utilizing NADPH

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, abbreviated NADP or, in older notation, TPN (triphosphopyridine nucleotide), is a cofactor used in anabolic reactions, such as the Calvin cycle and lipid and nucleic acid syntheses, which require NAD ...

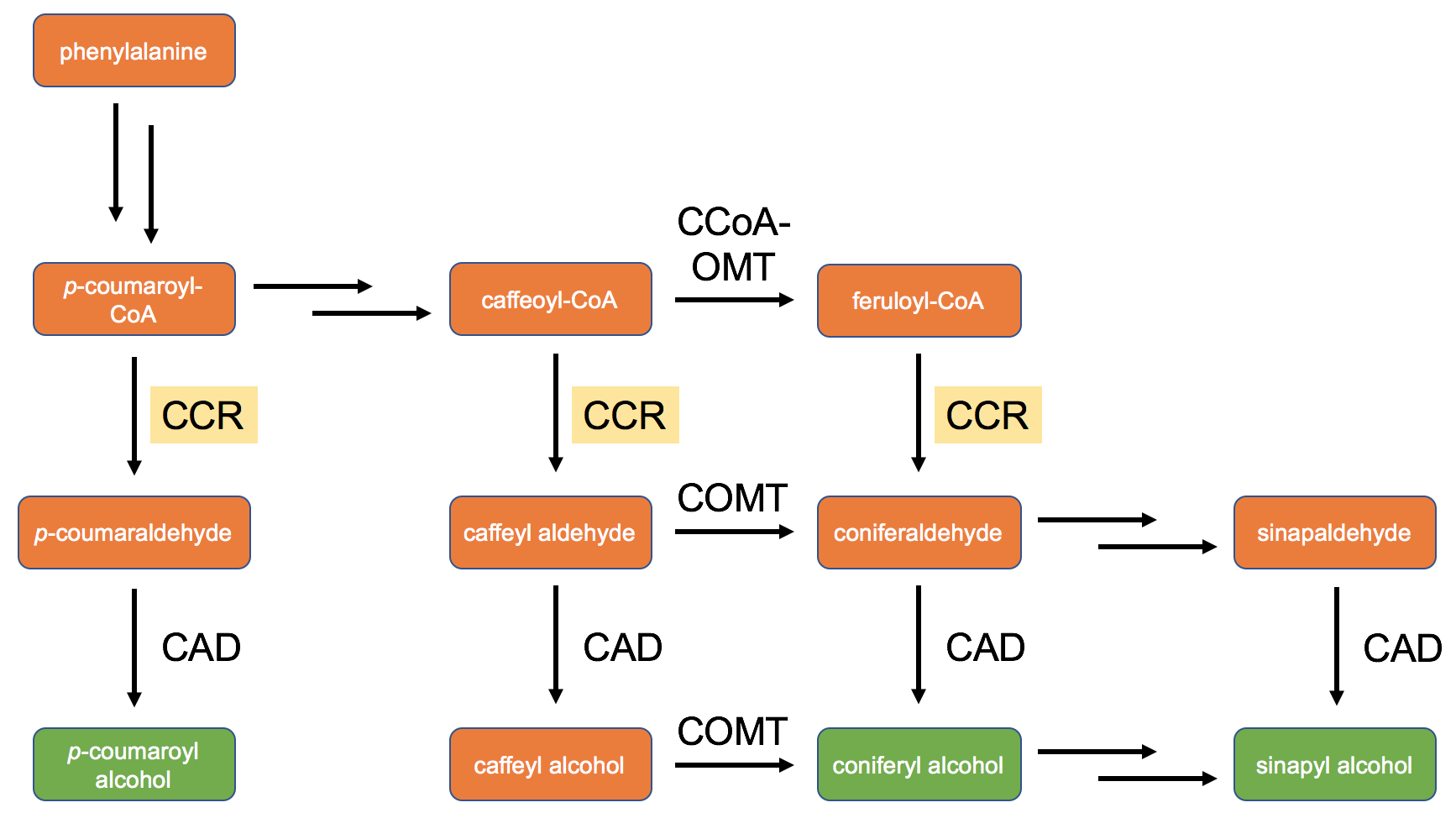

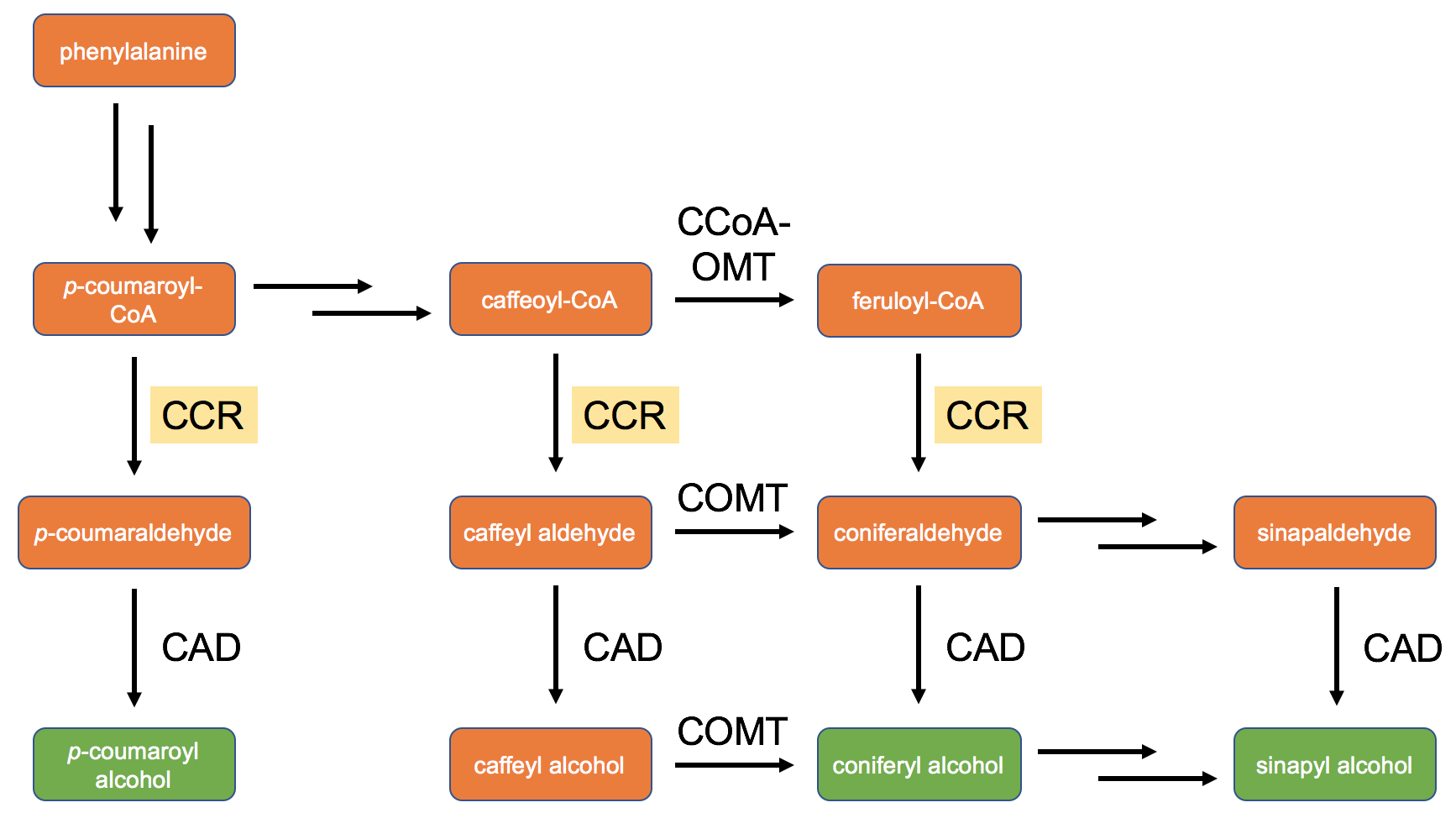

and H+ and releasing free CoA and NADP+ in the process. Common biologically relevant cinnamoyl-CoA substrates for CCR include ''p''-coumaroyl-CoA and feruloyl-CoA, which are converted into ''p''-coumaraldehyde and coniferaldehyde

Coniferyl aldehyde is an organic compound with the formula HO(CH3O)C6H3CH=CHCHO. It is a derivative of cinnamaldehyde, featuring 4-hydroxy and 3-methoxy substituents. It is a major precursor to lignin.

Biosynthetic role

In sweetgum (''Liquidambar ...

, respectively, though most CCRs show activity toward a variety of other substituted cinnamoyl-CoA's as well. Catalyzing the first committed step in monolignol

Monolignols, also called lignols, are the source materials for biosynthesis of both lignans and lignin and consist mainly of paracoumaryl alcohol (H), coniferyl alcohol (G) and sinapyl alcohol (S). These monolignols differ in their degree of meth ...

biosynthesis

Biosynthesis is a multi-step, enzyme-catalyzed process where substrates are converted into more complex products in living organisms. In biosynthesis, simple compounds are modified, converted into other compounds, or joined to form macromolecules. ...

, this enzyme plays a critical role in lignin formation, a process important in plants both for structural development and defense response.

Structure

The first confirmed CCR was isolated fromsoybean

The soybean, soy bean, or soya bean (''Glycine max'') is a species of legume native to East Asia, widely grown for its edible bean, which has numerous uses.

Traditional unfermented food uses of soybeans include soy milk, from which tofu an ...

(''Glycine max'') in 1976. However, crystal structures

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituents (such as atoms, molecules, or ions) are arranged in a highly ordered microscopic structure, forming a crystal lattice that extends in all directions. In addition, macrosc ...

have so far been reported for just three CCR homologs

A couple of homologous chromosomes, or homologs, are a set of one maternal and one paternal chromosome that pair up with each other inside a cell during fertilization. Homologs have the same genes in the same locus (genetics), loci where they pr ...

: '' Petunia x hybrida'' CCR1, ''Medicago truncatula

''Medicago truncatula'', the barrelclover, strong-spined medick, barrel medic, or barrel medick, is a small annual legume native to the Mediterranean region that is used in genomic research. It is a low-growing, clover-like plant tall with trifol ...

'' CCR2, and ''Sorghum bicolor

''Sorghum bicolor'', commonly called sorghum () and also known as great millet, broomcorn, guinea corn, durra, imphee, jowar, or milo, is a Poaceae, grass species cultivated for its grain, which is used for food for humans, animal feed, and ethan ...

'' CCR1. While the enzyme crystallizes as an asymmetric dimer, it is thought to exist as a monomer

In chemistry, a monomer ( ; ''mono-'', "one" + '' -mer'', "part") is a molecule that can react together with other monomer molecules to form a larger polymer chain or three-dimensional network in a process called polymerization.

Classification

Mo ...

in the cytoplasm, with each individual protein having a bilobal structure consisting of two domains surrounding a large, empty inner cleft for substrate binding. Typical CCRs have a molecular weight

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and bioch ...

of around 36-38 kDa.

The domain containing the enzyme's N-terminus

The N-terminus (also known as the amino-terminus, NH2-terminus, N-terminal end or amine-terminus) is the start of a protein or polypeptide, referring to the free amine group (-NH2) located at the end of a polypeptide. Within a peptide, the ami ...

consists of several alpha helices

The alpha helix (α-helix) is a common motif in the secondary structure of proteins and is a right hand-helix conformation in which every backbone N−H group hydrogen bonds to the backbone C=O group of the amino acid located four residues ear ...

and six beta strands that, in addition to a seventh strand connected to the C-terminus

The C-terminus (also known as the carboxyl-terminus, carboxy-terminus, C-terminal tail, C-terminal end, or COOH-terminus) is the end of an amino acid chain (protein or polypeptide), terminated by a free carboxyl group (-COOH). When the protein is ...

side of the enzyme, form a parallel beta sheet

The beta sheet, (β-sheet) (also β-pleated sheet) is a common motif of the regular protein secondary structure. Beta sheets consist of beta strands (β-strands) connected laterally by at least two or three backbone hydrogen bonds, forming a g ...

structure known as a Rossmann fold

The Rossmann fold is a tertiary fold found in proteins that bind nucleotides, such as enzyme cofactors FAD, NAD+, and NADP+. This fold is composed of alternating beta strands and alpha helical segments where the beta strands are hydrogen bonded ...

. In CCR, this fold structure, a common motif amongst proteins, serves as a binding domain for NADPH. The second domain, which consists of several alpha helices, beta strands, and extended loops, is responsible for binding the cinnamoyl-CoA substrate. These two domains are situated in such a way that the binding site

In biochemistry and molecular biology, a binding site is a region on a macromolecule such as a protein that binds to another molecule with specificity. The binding partner of the macromolecule is often referred to as a ligand. Ligands may inclu ...

s for NADPH and cinnamoyl-CoA are positioned closely to one another at the lobes' interface.

Though attempts to cocrystallize the enzyme with a bound cinnamoyl-CoA have thus far been unsuccessful, molecular docking studies indicate that the CoA segment of these molecules folds around to bind along the outer part of the inter-domain cleft, while the phenyl

In organic chemistry, the phenyl group, or phenyl ring, is a cyclic group of atoms with the formula C6 H5, and is often represented by the symbol Ph. Phenyl group is closely related to benzene and can be viewed as a benzene ring, minus a hydrogen ...

-containing portion of these substrates likely binds in the deepest part of the cleft. This inner part of the pocket contains several amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha am ...

s with nonpolar

In chemistry, polarity is a separation of electric charge leading to a molecule or its chemical groups having an electric dipole moment, with a negatively charged end and a positively charged end.

Polar molecules must contain one or more polar ...

side chain

In organic chemistry and biochemistry, a side chain is a chemical group that is attached to a core part of the molecule called the "main chain" or backbone. The side chain is a hydrocarbon branching element of a molecule that is attached to a l ...

s necessary for stabilization of the hydrophobic

In chemistry, hydrophobicity is the physical property of a molecule that is seemingly repelled from a mass of water (known as a hydrophobe). In contrast, hydrophiles are attracted to water.

Hydrophobic molecules tend to be nonpolar and, th ...

phenyl ring in addition to a tyrosine

-Tyrosine or tyrosine (symbol Tyr or Y) or 4-hydroxyphenylalanine is one of the 20 standard amino acids that are used by cells to synthesize proteins. It is a non-essential amino acid with a polar side group. The word "tyrosine" is from the Gr ...

residue important for hydrogen bond

In chemistry, a hydrogen bond (or H-bond) is a primarily electrostatic force of attraction between a hydrogen (H) atom which is covalently bound to a more electronegative "donor" atom or group (Dn), and another electronegative atom bearing a ...

formation with the ring's 4-hydroxyl

In chemistry, a hydroxy or hydroxyl group is a functional group with the chemical formula and composed of one oxygen atom covalently bonded to one hydrogen atom. In organic chemistry, alcohols and carboxylic acids contain one or more hydroxy ...

group. The particular identities of the nonpolar residues are believed to play a critical role in determining substrate specificity.

Mechanism

The

The mechanism

Mechanism may refer to:

* Mechanism (engineering), rigid bodies connected by joints in order to accomplish a desired force and/or motion transmission

*Mechanism (biology), explaining how a feature is created

*Mechanism (philosophy), a theory that ...

for the reduction of the CoA thioester

In organic chemistry, thioesters are organosulfur compounds with the functional group . They are analogous to carboxylate esters () with the sulfur in the thioester playing the role of the linking oxygen in the carboxylate ester, as implied by t ...

to the aldehyde involves a hydride

In chemistry, a hydride is formally the anion of hydrogen( H−). The term is applied loosely. At one extreme, all compounds containing covalently bound H atoms are called hydrides: water (H2O) is a hydride of oxygen, ammonia is a hydride of ...

transfer to the carbonyl

In organic chemistry, a carbonyl group is a functional group composed of a carbon atom double-bonded to an oxygen atom: C=O. It is common to several classes of organic compounds, as part of many larger functional groups. A compound containing a ...

carbon from NADPH, forming a tetrahedral intermediate with a formal negative charge on the oxygen atom. This negative charge is thought to be stabilized partially via hydrogen bonding with the hydrogen atoms of nearby tyrosine and serine

Serine (symbol Ser or S) is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated − form under biological conditions), a carboxyl group (which is in the deprotonated − form un ...

side chains. The serine and tyrosine residues are conserved across all CCRs as part of a catalytic triad along with lysine

Lysine (symbol Lys or K) is an α-amino acid that is a precursor to many proteins. It contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated form under biological conditions), an α-carboxylic acid group (which is in the deprotonated −C ...

, which is thought to control the pKa of the tyrosine via electrostatic

Electrostatics is a branch of physics that studies electric charges at rest (static electricity).

Since classical times, it has been known that some materials, such as amber, attract lightweight particles after rubbing. The Greek word for amber ...

interactions with the ribose group of the NADPH.

The tetrahedral intermediate then collapses, kicking out the CoA and forming an aldehyde

In organic chemistry, an aldehyde () is an organic compound containing a functional group with the structure . The functional group itself (without the "R" side chain) can be referred to as an aldehyde but can also be classified as a formyl grou ...

as the final product. The thiolate

In organic chemistry, a thiol (; ), or thiol derivative, is any organosulfur compound of the form , where R represents an alkyl or other organic substituent. The functional group itself is referred to as either a thiol group or a sulfhydryl grou ...

of the CoA is protonated

In chemistry, protonation (or hydronation) is the adding of a proton (or hydron, or hydrogen cation), (H+) to an atom, molecule, or ion, forming a conjugate acid. (The complementary process, when a proton is removed from a Brønsted–Lowry acid, ...

either as it leaves by a nearby residue or after it is free from the binding pocket and out of the enzyme all-together; the exact mechanism is currently unclear, but evidence suggests that a cysteine

Cysteine (symbol Cys or C; ) is a semiessential proteinogenic amino acid with the formula . The thiol side chain in cysteine often participates in enzymatic reactions as a nucleophile.

When present as a deprotonated catalytic residue, sometime ...

residue may play the role of thiolate proton donor.

Biological Function

Phylogenomic

Phylogenomics is the intersection of the fields of evolution and genomics. The term has been used in multiple ways to refer to analysis that involves genome data and evolutionary reconstructions. It is a group of techniques within the larger fields ...

analysis indicates that enzymes with true CCR activity first evolved

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation t ...

in the of land plants

The Embryophyta (), or land plants, are the most familiar group of green plants that comprise vegetation on Earth. Embryophytes () have a common ancestor with green algae, having emerged within the Phragmoplastophyta clade of green algae as siste ...

. Most if not all modern land plants and all vascular plant

Vascular plants (), also called tracheophytes () or collectively Tracheophyta (), form a large group of land plants ( accepted known species) that have lignified tissues (the xylem) for conducting water and minerals throughout the plant. They al ...

s are believed to have at least one functional CCR, an absolute requirement for any plant species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

with lignified tissues. Most CCR homologs are highly expressed during development, especially in stem

Stem or STEM may refer to:

Plant structures

* Plant stem, a plant's aboveground axis, made of vascular tissue, off which leaves and flowers hang

* Stipe (botany), a stalk to support some other structure

* Stipe (mycology), the stem of a mushro ...

, root

In vascular plants, the roots are the organs of a plant that are modified to provide anchorage for the plant and take in water and nutrients into the plant body, which allows plants to grow taller and faster. They are most often below the sur ...

, and xylem

Xylem is one of the two types of transport tissue in vascular plants, the other being phloem. The basic function of xylem is to transport water from roots to stems and leaves, but it also transports nutrients. The word ''xylem'' is derived from ...

cells which require the enhanced structural support provided by lignin. However, certain CCRs are not constitutively expressed throughout development and are only up-regulated during enhanced lignification in response to stressors such as pathogen

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a germ ...

attack.  CCR is especially important because it acts as a final control point for regulation of metabolic flux toward the monolignols and therefore toward lignin as well; prior to this reduction step, the cinnamoyl-CoA's can still enter into other expansive specialized metabolic pathways. For example, feruloyl-CoA is a precursor of the

CCR is especially important because it acts as a final control point for regulation of metabolic flux toward the monolignols and therefore toward lignin as well; prior to this reduction step, the cinnamoyl-CoA's can still enter into other expansive specialized metabolic pathways. For example, feruloyl-CoA is a precursor of the coumarin

Coumarin () or 2''H''-chromen-2-one is an aromatic organic chemical compound with formula . Its molecule can be described as a benzene molecule with two adjacent hydrogen atoms replaced by a lactone-like chain , forming a second six-membered h ...

scopoletin

Scopoletin is a coumarin. It found in the root of plants in the genus ''Scopolia'' such as ''Scopolia carniolica'' and ''Scopolia japonica'', in chicory, in '' Artemisia scoparia'', in the roots and leaves of stinging nettle (''Urtica dioica''), i ...

, a compound believed to play an important role in plant pathogen response. CCR also plays a role in determining lignin composition by regulating levels of the different monomers according to its specific activity toward particular cinnamoyl-CoA's. Monocots

Monocotyledons (), commonly referred to as monocots, (Lilianae ''sensu'' Chase & Reveal) are grass and grass-like flowering plants (angiosperms), the seeds of which typically contain only one embryonic leaf, or cotyledon. They constitute one of t ...

and dicots, for example, tend to have very different lignin patterns: lignin found in monocots typically has a higher percentage of ''p''-coumaroyl alcohol-derived subunits, while lignin found in dicots is typically composed of almost entirely coniferyl alcohol

Coniferyl alcohol is an organic compound with the formula HO(CH3O)C6H3CH=CHCH2OH. A colourless or white solid, it is one of the monolignols, produced via the phenylpropanoid biochemical pathway. When copolymerized with related aromatic compounds, ...

and sinapyl alcohol

Sinapyl alcohol is an organic compound structurally related to cinnamic acid. It is biosynthetized via the phenylpropanoid biochemical pathway, its immediate precursor being sinapaldehyde. This phytochemical is one of the monolignols, which are ...

subunits. As can be seen in the diagram shown to the right, these monolignols are derived directly from their corresponding aldehydes, except in the case of sinapyl alcohol - while several CCR homologs have been shown to act on sinapoyl-CoA ''in vitro

''In vitro'' (meaning in glass, or ''in the glass'') studies are performed with microorganisms, cells, or biological molecules outside their normal biological context. Colloquially called "test-tube experiments", these studies in biology an ...

'', it is unclear whether this activity is biologically relevant and most current models of the lignin pathway do not include this reaction as a valid step.

Recent studies indicate that many plant species have two distinct homologs of CCR with differential activity ''in planta''. In some plants the two homologs vary primarily by substrate specificity. For example, CCR1 of the model legume

A legume () is a plant in the family Fabaceae (or Leguminosae), or the fruit or seed of such a plant. When used as a dry grain, the seed is also called a pulse. Legumes are grown agriculturally, primarily for human consumption, for livestock f ...

''Medicago truncatula'' shows strong preference toward feruloyl-CoA (typical of most CCRs), while the plant's CCR2 exhibits a clear preference for both ''p''-coumaroyl- and caffeoyl-CoA. This second CCR, which is allosterically

In biochemistry, allosteric regulation (or allosteric control) is the regulation of an enzyme by binding an effector molecule at a site other than the enzyme's active site.

The site to which the effector binds is termed the ''allosteric sit ...

activated by its preferred substrates but inhibited by feruloyl-CoA, is thought to act as part of a shunt pathway toward coniferaldehyde that enhances the pathway's overall flexibility and robustness in different conditions. In other cases though, the two homologs vary primarily by expression pattern. In the model plant ''Arabidopsis thaliana

''Arabidopsis thaliana'', the thale cress, mouse-ear cress or arabidopsis, is a small flowering plant native to Eurasia and Africa. ''A. thaliana'' is considered a weed; it is found along the shoulders of roads and in disturbed land.

A winter a ...

'', for instance, the CCR1 and CCR2 homologs both display higher activity toward feruloyl-CoA than other substrates, but CCR2 is only expressed transiently during bacterial infection

Pathogenic bacteria are bacteria that can cause disease. This article focuses on the bacteria that are pathogenic to humans. Most species of bacteria are harmless and are often beneficial but others can cause infectious diseases. The number of ...

. The homolog pair in switchgrass

''Panicum virgatum'', commonly known as switchgrass, is a perennial warm season bunchgrass native to North America, where it occurs naturally from 55°N latitude in Canada southwards into the United States and Mexico. Switchgrass is one of the ...

(''Panicum virgatum'') differs in both ways: CCR2 prefers ''p''-coumaroyl- and caffeoyl-CoA and is only expressed under specifically induced conditions, while CCR1 prefers feruloyl-CoA and is expressed constitutively in lignifying tissue.

Regulation of CCR expression is thought to occur primarily at the transcriptional level. In ''Arabidopsis thaliana'', several of the required transcription factor

In molecular biology, a transcription factor (TF) (or sequence-specific DNA-binding factor) is a protein that controls the rate of transcription of genetic information from DNA to messenger RNA, by binding to a specific DNA sequence. The fu ...

s for CCR expression have actually been identified, including MYB58 and MYB63, both of which are implicated generally in secondary cell wall formation. It has been shown that over-expression of these two transcription factors results in a 2- to 3-fold increase in CCR mRNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of Protein biosynthesis, synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is ...

transcripts, though intriguingly, the up-regulation of genes further upstream in the monolignol pathway is even greater. Non-transcriptional regulation of CCR, however, can be important as well. In rice (''Oryza sativa

''Oryza sativa'', commonly known as Asian rice or indica rice, is the plant species most commonly referred to in English as ''rice''. It is the type of farmed rice whose cultivars are most common globally, and was first domesticated in the Yan ...

''), for example, evidence suggests that the CCR1 homolog is an effector

Effector may refer to:

*Effector (biology), a molecule that binds to a protein and thereby alters the activity of that protein

* ''Effector'' (album), a music album by the Experimental Techno group Download

* ''EFFector'', a publication of the El ...

of Rac1, a small GTPase

GTPases are a large family of hydrolase enzymes that bind to the nucleotide guanosine triphosphate (GTP) and hydrolyze it to guanosine diphosphate (GDP). The GTP binding and hydrolysis takes place in the highly conserved P-loop "G domain", a pro ...

important for plant defense response. In this case, the Rac1 protein is proposed to activate CCR upon binding, leading to enhanced monolignol biosynthesis. Because Rac1 also activates NADPH oxidase

NADPH oxidase (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase) is a membrane-bound enzyme complex that faces the extracellular space. It can be found in the plasma membrane as well as in the membranes of phagosomes used by neutrophil white ...

, which produces peroxide

In chemistry, peroxides are a group of compounds with the structure , where R = any element. The group in a peroxide is called the peroxide group or peroxo group. The nomenclature is somewhat variable.

The most common peroxide is hydrogen p ...

s critical for monolignol polymerization

In polymer chemistry, polymerization (American English), or polymerisation (British English), is a process of reacting monomer, monomer molecules together in a chemical reaction to form polymer chains or three-dimensional networks. There are ...

, overall lignin biosynthesis is enhanced as well.

Biotechnological significance

Efforts to engineer plantcell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer surrounding some types of cells, just outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. It provides the cell with both structural support and protection, and also acts as a filtering mech ...

formation for enhanced biofuel

Biofuel is a fuel that is produced over a short time span from biomass, rather than by the very slow natural processes involved in the formation of fossil fuels, such as oil. According to the United States Energy Information Administration (E ...

production commonly target lignin biosynthesis in order to reduce lignin content and thereby improve yields of ethanol

Ethanol (abbr. EtOH; also called ethyl alcohol, grain alcohol, drinking alcohol, or simply alcohol) is an organic compound. It is an Alcohol (chemistry), alcohol with the chemical formula . Its formula can be also written as or (an ethyl ...

from cellulose

Cellulose is an organic compound with the formula , a polysaccharide consisting of a linear chain of several hundred to many thousands of β(1→4) linked D-glucose units. Cellulose is an important structural component of the primary cell wall ...

, a complex polysaccharide

Polysaccharides (), or polycarbohydrates, are the most abundant carbohydrates found in food. They are long chain polymeric carbohydrates composed of monosaccharide units bound together by glycosidic linkages. This carbohydrate can react with wa ...

important for cell wall structure. Lignin is troublesome for biofuel production because it is the main contributor to plant biomass

Biomass is plant-based material used as a fuel for heat or electricity production. It can be in the form of wood, wood residues, energy crops, agricultural residues, and waste from industry, farms, and households. Some people use the terms bi ...

recalcitrance due to its toughness and heterogeneity

Homogeneity and heterogeneity are concepts often used in the sciences and statistics relating to the uniformity of a substance or organism. A material or image that is homogeneous is uniform in composition or character (i.e. color, shape, siz ...

. By reducing lignin content, the cellulose is more easily accessible to the chemical and biological reagent

In chemistry, a reagent ( ) or analytical reagent is a substance or compound added to a system to cause a chemical reaction, or test if one occurs. The terms ''reactant'' and ''reagent'' are often used interchangeably, but reactant specifies a ...

s used to break it down. Lowering the expression level of CCR in particular has emerged as a common strategy for accomplishing this goal, and this strategy has resulted in successful lignin content reduction and increased ethanol production from several plant species including tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

(''Nicotiana tabacum'') and poplar (''Populus tremula x Populus alba''). Challenges with this strategy include the wide variation in expression levels associated with current plant genetic transformation technologies in addition to the dramatic decrease in overall growth and biomass that typically accompanies low lignin production. However, it has been shown that by targeting CCR down-regulation to specific tissue types or coupling it to down-regulation of cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase (CAD), the latter challenge at least can be somewhat mitigated.

References

{{Portal bar, Biology, border=no EC 1.2.1 NADPH-dependent enzymes Enzymes of unknown structure