church monument on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Funerary art is any work of art forming, or placed in, a repository for the remains of the dead. The term encompasses a wide variety of forms, including cenotaphs ("empty tombs"), tomb-like monuments which do not contain human remains, and communal memorials to the dead, such as war memorials, which may or may not contain remains, and a range of prehistoric megalithic constructs. Funerary art may serve many cultural functions. It can play a role in burial rites, serve as an article for use by the dead in the afterlife, and celebrate the life and accomplishments of the dead, whether as part of kinship-centred practices of

Funerary art is any work of art forming, or placed in, a repository for the remains of the dead. The term encompasses a wide variety of forms, including cenotaphs ("empty tombs"), tomb-like monuments which do not contain human remains, and communal memorials to the dead, such as war memorials, which may or may not contain remains, and a range of prehistoric megalithic constructs. Funerary art may serve many cultural functions. It can play a role in burial rites, serve as an article for use by the dead in the afterlife, and celebrate the life and accomplishments of the dead, whether as part of kinship-centred practices of

Most of humanity's oldest known archaeological constructions are tombs. Mostly megalithic, the earliest instances date to within a few centuries of each other, yet show a wide diversity of form and purpose. Tombs in the

Most of humanity's oldest known archaeological constructions are tombs. Mostly megalithic, the earliest instances date to within a few centuries of each other, yet show a wide diversity of form and purpose. Tombs in the

Egyptian funerary art was inseparable to the religious belief that life continued after death and that "death is a mere phase of life". Aesthetic objects and images connected with this belief were partially intended to preserve material goods, wealth and status for the journey between this life and the next, and to "commemorate the life of the tomb owner ... depict performance of the burial rites, and in general present an environment that would be conducive to the tomb owner's rebirth." In this context are the Egyptian mummies encased in one or more layers of decorated coffin, and the canopic jars preserving internal organs. A special category of

Egyptian funerary art was inseparable to the religious belief that life continued after death and that "death is a mere phase of life". Aesthetic objects and images connected with this belief were partially intended to preserve material goods, wealth and status for the journey between this life and the next, and to "commemorate the life of the tomb owner ... depict performance of the burial rites, and in general present an environment that would be conducive to the tomb owner's rebirth." In this context are the Egyptian mummies encased in one or more layers of decorated coffin, and the canopic jars preserving internal organs. A special category of

The ancient Greeks did not generally leave elaborate grave goods, except for a coin to pay Charon, the ferryman to Hades, and pottery; however the ''epitaphios'' or funeral oration from which the word epitaph comes was regarded as of great importance, and

The ancient Greeks did not generally leave elaborate grave goods, except for a coin to pay Charon, the ferryman to Hades, and pottery; however the ''epitaphios'' or funeral oration from which the word epitaph comes was regarded as of great importance, and

Objects connected with death, in particular sarcophagi and cinerary urns, form the basis of much of current knowledge of the ancient

Objects connected with death, in particular sarcophagi and cinerary urns, form the basis of much of current knowledge of the ancient

The burial customs of the

The burial customs of the

Funerary art varied greatly across Chinese history. Tombs of early rulers rival the ancient Egyptians for complexity and value of grave goods, and have been similarly pillaged over the centuries by tomb robbers. For a long time, literary references to jade burial suits were regarded by scholars as fanciful myths, but a number of examples were excavated in the 20th century, and it is now believed that they were relatively common among early rulers. Knowledge of pre-dynastic Chinese culture has been expanded by spectacular discoveries at Sanxingdui and other sites. Very large tumuli could be erected, and later, mausoleums. Several special large shapes of

Funerary art varied greatly across Chinese history. Tombs of early rulers rival the ancient Egyptians for complexity and value of grave goods, and have been similarly pillaged over the centuries by tomb robbers. For a long time, literary references to jade burial suits were regarded by scholars as fanciful myths, but a number of examples were excavated in the 20th century, and it is now believed that they were relatively common among early rulers. Knowledge of pre-dynastic Chinese culture has been expanded by spectacular discoveries at Sanxingdui and other sites. Very large tumuli could be erected, and later, mausoleums. Several special large shapes of  Tang dynasty tomb figures, in "three-colour" ''

Tang dynasty tomb figures, in "three-colour" ''

Murals painted on the walls of the Goguryeo tombs are examples of Korean painting from its

Murals painted on the walls of the Goguryeo tombs are examples of Korean painting from its

The Kofun period of Japanese history, from the 3rd to 6th centuries CE, is named after '' kofun'', the often enormous keyhole-shaped Imperial mound-tombs, often on a moated island. None of these have ever been allowed to be excavated, so their possibly spectacular contents remain unknown. Late examples which have been investigated, such as the Kitora Tomb, had been robbed of most of their contents, but the Takamatsuzuka Tomb retains mural paintings. Lower down the social scale in the same period,

The Kofun period of Japanese history, from the 3rd to 6th centuries CE, is named after '' kofun'', the often enormous keyhole-shaped Imperial mound-tombs, often on a moated island. None of these have ever been allowed to be excavated, so their possibly spectacular contents remain unknown. Late examples which have been investigated, such as the Kitora Tomb, had been robbed of most of their contents, but the Takamatsuzuka Tomb retains mural paintings. Lower down the social scale in the same period,

Unlike many Western cultures, that of

Unlike many Western cultures, that of  The Jaina Island graves are noted for their abundance of clay figurines. Human remains within the roughly 1,000 excavated graves on the island (out of 20,000 total) were found to be accompanied by glassware, slateware, or pottery, as well as one or more ceramic figurines, usually resting on the occupant's chest or held in their hands. The function of these figurines is not known: due to gender and age mismatches, they are unlikely to be portraits of the grave occupants, although the later figurines are known to be representations of goddesses.

The so-called shaft tomb tradition of western Mexico is known almost exclusively from grave goods, which include hollow ceramic figures, obsidian and shell jewelry, pottery, and other items (se

The Jaina Island graves are noted for their abundance of clay figurines. Human remains within the roughly 1,000 excavated graves on the island (out of 20,000 total) were found to be accompanied by glassware, slateware, or pottery, as well as one or more ceramic figurines, usually resting on the occupant's chest or held in their hands. The function of these figurines is not known: due to gender and age mismatches, they are unlikely to be portraits of the grave occupants, although the later figurines are known to be representations of goddesses.

The so-called shaft tomb tradition of western Mexico is known almost exclusively from grave goods, which include hollow ceramic figures, obsidian and shell jewelry, pottery, and other items (se

this Flickr photo

for a reconstruction). Of particular note are the various ceramic tableaux including village scenes, for example, players engaged in a Mesoamerican ballgame. Although these tableaux may merely depict village life, it has been proposed that they instead (or also) depict the underworld. Ceramic dogs are also widely known from looted tombs, and are thought by some to represent psychopomps (soul guides), although dogs were often the major source of protein in ancient Mesoamerica. The

The  The earliest colonist graves were either unmarked, or had very simple timber headstone, with little order to their plotting, reflecting their

The earliest colonist graves were either unmarked, or had very simple timber headstone, with little order to their plotting, reflecting their

There is an enormous diversity of funeral art from traditional societies across the world, much of it in perishable materials, and some is mentioned elsewhere in the article. In traditional African societies, masks often have a specific association with death, and some types may be worn mainly or exclusively for funeral ceremonies. Akan peoples of West Africa commissioned nsodie memorial heads of royal personages. The funeral ceremonies of the

There is an enormous diversity of funeral art from traditional societies across the world, much of it in perishable materials, and some is mentioned elsewhere in the article. In traditional African societies, masks often have a specific association with death, and some types may be worn mainly or exclusively for funeral ceremonies. Akan peoples of West Africa commissioned nsodie memorial heads of royal personages. The funeral ceremonies of the

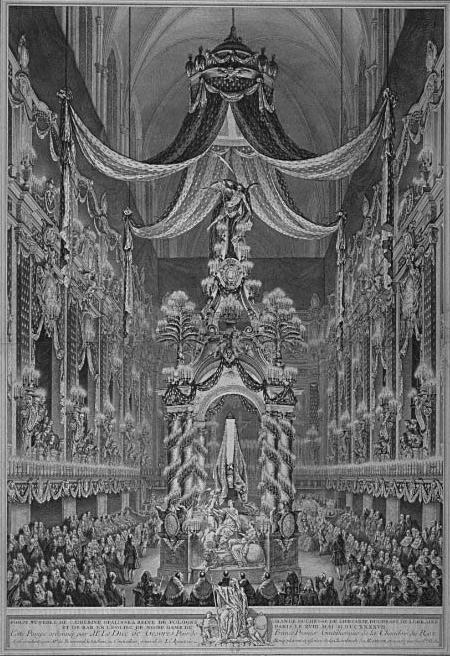

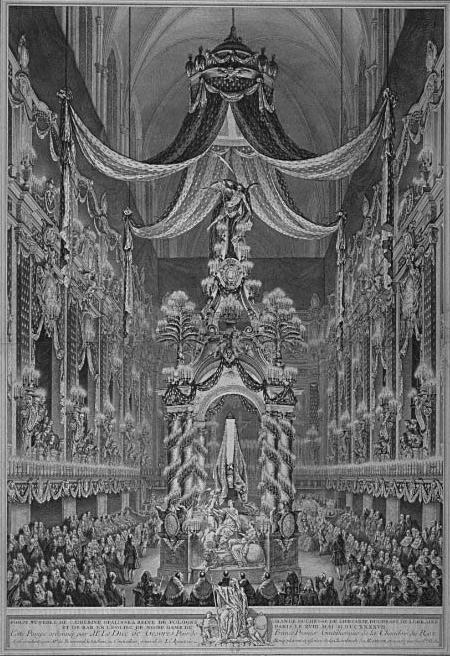

In the late Middle Ages, influenced by the Black Death and devotional writers, explicit ''

In the late Middle Ages, influenced by the Black Death and devotional writers, explicit ''

ancestor veneration

The veneration of the dead, including one's ancestors, is based on love and respect for the deceased. In some cultures, it is related to beliefs that the dead have a continued existence, and may possess the ability to influence the fortune of t ...

or as a publicly directed dynastic

A dynasty is a sequence of rulers from the same family,''Oxford English Dictionary'', "dynasty, ''n''." Oxford University Press (Oxford), 1897. usually in the context of a monarchical system, but sometimes also appearing in republics. A ...

display. It can also function as a reminder of the mortality of humankind, as an expression of cultural values and roles, and help to propitiate the spirits of the dead, maintaining their benevolence and preventing their unwelcome intrusion into the lives of the living.

The deposit of objects with an apparent aesthetic intention is found in almost all cultures – Hindu culture, which has little, is a notable exception. Many of the best-known artistic creations of past cultures – from the Egyptian pyramids

The Egyptian pyramids are ancient masonry structures located in Egypt. Sources cite at least 118 identified "Egyptian" pyramids. Approximately 80 pyramids were built within the Kingdom of Kush, now located in the modern country of Sudan. ...

and the Tutankhamun treasure, to the Terracotta Army

The Terracotta Army is a collection of terracotta sculptures depicting the armies of Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of China. It is a form of funerary art buried with the emperor in 210–209 BCE with the purpose of protecting the emperor i ...

surrounding the tomb of Qin Shi Huang

Qin Shi Huang (, ; 259–210 BC) was the founder of the Qin dynasty and the first emperor of a unified China. Rather than maintain the title of "king" ( ''wáng'') borne by the previous Shang and Zhou rulers, he ruled as the First Emperor ( ...

, the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus

The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus or Tomb of Mausolus ( grc, Μαυσωλεῖον τῆς Ἁλικαρνασσοῦ; tr, Halikarnas Mozolesi) was a tomb built between 353 and 350 BC in Halicarnassus (present Bodrum, Turkey) for Mausolus, an ...

, the Sutton Hoo

Sutton Hoo is the site of two early medieval cemeteries dating from the 6th to 7th centuries near the English town of Woodbridge. Archaeologists have been excavating the area since 1938, when a previously undisturbed ship burial containing a ...

ship burial and the Taj Mahal – are tombs or objects found in and around them. In most instances, specialized funeral art was produced for the powerful and wealthy, although the burials of ordinary people might include simple monuments and grave goods, usually from their possessions.

An important factor in the development of traditions of funerary art is the division between what was intended to be visible to visitors or the public after completion of the funeral ceremonies. The treasure of the 18th dynasty Pharaoh Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun (, egy, twt-ꜥnḫ-jmn), Egyptological pronunciation Tutankhamen () (), sometimes referred to as King Tut, was an Egyptian pharaoh who was the last of his royal family to rule during the end of the Eighteenth Dynasty (ruled ...

, for example, though exceptionally lavish, was never intended to be seen again after it was deposited, while the exterior of the pyramids was a permanent and highly effective demonstration of the power of their creators. A similar division can be seen in grand East Asian tombs. In other cultures, nearly all the art connected with the burial, except for limited grave goods, was intended for later viewing by the public or at least those admitted by the custodians. In these cultures, traditions such as the sculpted sarcophagus

A sarcophagus (plural sarcophagi or sarcophaguses) is a box-like funeral receptacle for a corpse, most commonly carved in stone, and usually displayed above ground, though it may also be buried. The word ''sarcophagus'' comes from the Gre ...

and tomb monument of the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

and Roman empires, and later the Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words '' Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρ ...

world, have flourished. The mausoleum intended for visiting was the grandest type of tomb in the classical world, and later common in Islamic culture.

Terminology

Tomb

A tomb ( grc-gre, τύμβος ''tumbos'') is a repository for the remains of the dead. It is generally any structurally enclosed interment space or burial chamber, of varying sizes. Placing a corpse into a tomb can be called ''immuremen ...

is a general term for any repository for human remains, while grave goods

Grave goods, in archaeology and anthropology, are the items buried along with the body.

They are usually personal possessions, supplies to smooth the deceased's journey into the afterlife or offerings to the gods. Grave goods may be classed as a ...

are other objects which have been placed within the tomb. Such objects may include the personal possessions of the deceased, objects specially created for the burial, or miniature versions of things believed to be needed in an afterlife. Knowledge of many non-literate cultures is drawn largely from these sources.

A tumulus

A tumulus (plural tumuli) is a mound of earth and stones raised over a grave or graves. Tumuli are also known as barrows, burial mounds or '' kurgans'', and may be found throughout much of the world. A cairn, which is a mound of stones ...

, mound, kurgan, or long barrow

Long barrows are a style of monument constructed across Western Europe in the fifth and fourth millennia BCE, during the Early Neolithic period. Typically constructed from earth and either timber or stone, those using the latter material repre ...

covered important burials in many cultures, and the body may be placed in a sarcophagus, usually of stone, or a coffin, usually of wood. A mausoleum is a building erected mainly as a tomb, taking its name from the Mausoleum of Mausolus at Halicarnassus. Stele is a term for erect stones that are often what are now called gravestones. Ship burial

A ship burial or boat grave is a burial in which a ship or boat is used either as the tomb for the dead and the grave goods, or as a part of the grave goods itself. If the ship is very small, it is called a boat grave. This style of burial was ...

s are mostly found in coastal Europe, while chariot burial

Chariot burials are tombs in which the deceased was buried together with their chariot, usually including their horses and other possessions. An instance of a person being buried with their horse (without the chariot) is called horse burial.

Fin ...

s are found widely across Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelag ...

. Catacombs

Catacombs are man-made subterranean passageways for religious practice. Any chamber used as a burial place is a catacomb, although the word is most commonly associated with the Roman Empire.

Etymology and history

The first place to be referred ...

, of which the most famous examples are those in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

and Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandr ...

, are underground cemeteries connected by tunnelled passages. A large group of burials with traces remaining above ground can be called a necropolis; if there are no such visible structures, it is a grave field. A cenotaph is a memorial without a burial.

The word "funerary" strictly means "of or pertaining to a funeral or burial", but there is a long tradition in English of applying it not only to the practices and artefacts directly associated with funeral rites, but also to a wider range of more permanent memorials to the dead. Particularly influential in this regard was John Weever's ''Ancient Funerall Monuments'' (1631), the first full-length book to be dedicated to the subject of tomb memorials and epitaphs. More recently, some scholars have challenged the usage: Phillip Lindley, for example, makes a point of referring to "tomb monuments", saying "I have avoided using the term 'funeral monuments' because funeral effigies were, in the Middle Ages, temporary products, made as substitutes for the encoffined corpse for use during the funeral ceremonies". Others, however, have found this distinction "rather pedantic".

Related genres of commemorative art for the dead take many forms, such as the '' moai'' figures of Easter Island

Easter Island ( rap, Rapa Nui; es, Isla de Pascua) is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle in Oceania. The island is most famous for its nearl ...

, apparently a type of sculpted ancestor portrait, though hardly individualized. These are common in cultures as diverse as Ancient Rome and China, in both of which they are kept in the houses of the descendants, rather than being buried. Many cultures have psychopomp figures, such as the Greek Hermes

Hermes (; grc-gre, Ἑρμῆς) is an Olympian deity in ancient Greek religion and mythology. Hermes is considered the herald of the gods. He is also considered the protector of human heralds, travellers, thieves, merchants, and orato ...

and Etruscan Charun, who help conduct the spirits of the dead into the afterlife.

History

Pre-history

Most of humanity's oldest known archaeological constructions are tombs. Mostly megalithic, the earliest instances date to within a few centuries of each other, yet show a wide diversity of form and purpose. Tombs in the

Most of humanity's oldest known archaeological constructions are tombs. Mostly megalithic, the earliest instances date to within a few centuries of each other, yet show a wide diversity of form and purpose. Tombs in the Iberian peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

have been dated through thermoluminescence

Thermoluminescence is a form of luminescence that is exhibited by certain crystalline materials, such as some minerals, when previously absorbed energy from electromagnetic radiation or other ionizing radiation is re-emitted as light upon h ...

to c. 4510 BCE, and some burials at the Carnac stones in Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica during the period o ...

also date back to the fifth millennium BCE. The commemorative value of such burial sites are indicated by the fact that, at some stage, they became elevated, and that the constructs, almost from the earliest, sought to be monumental. This effect was often achieved by encapsulating a single corpse in a basic pit, surrounded by an elaborate ditch and drain. Over-ground commemoration is thought to be tied to the concept of collective memory, and these early tombs were likely intended as a form of ancestor-worship, a development available only to communities that had advanced to the stage of settled livestock and formed social roles and relationships and specialized sectors of activity.

In Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several part ...

and Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

societies, a great variety of tombs are found, with tumulus mounds, megaliths, and pottery as recurrent elements. In Eurasia, a dolmen

A dolmen () or portal tomb is a type of single-chamber megalithic tomb, usually consisting of two or more upright megaliths supporting a large flat horizontal capstone or "table". Most date from the early Neolithic (40003000 BCE) and were so ...

is the exposed stone framework for a chamber tomb originally covered by earth to make a mound which no longer exists. Stones may be carved with geometric patterns (petroglyph

A petroglyph is an image created by removing part of a rock surface by incising, picking, carving, or abrading, as a form of rock art. Outside North America, scholars often use terms such as "carving", "engraving", or other descriptions ...

s), for example cup and ring marks. Group tombs were made, the social context of which is hard to decipher. Urn burials, where bones are buried in a pottery container, either in a more elaborate tomb, or by themselves, are widespread, by no means restricted to the Urnfield culture

The Urnfield culture ( 1300 BC – 750 BC) was a late Bronze Age culture of Central Europe, often divided into several local cultures within a broader Urnfield tradition. The name comes from the custom of cremating the dead and p ...

which is named after them, or even to Eurasia. Menhir

A menhir (from Brittonic languages: ''maen'' or ''men'', "stone" and ''hir'' or ''hîr'', "long"), standing stone, orthostat, or lith is a large human-made upright stone, typically dating from the European middle Bronze Age. They can be fou ...

s, or "standing stone

A menhir (from Brittonic languages: ''maen'' or ''men'', "stone" and ''hir'' or ''hîr'', "long"), standing stone, orthostat, or lith is a large human-made upright stone, typically dating from the European middle Bronze Age. They can be fou ...

s", seem often to mark graves or serve as memorials, while the later runestone

A runestone is typically a raised stone with a runic inscription, but the term can also be applied to inscriptions on boulders and on bedrock. The tradition began in the 4th century and lasted into the 12th century, but most of the runestones da ...

s and image stones often are cenotaphs, or memorials apart from the grave itself; these continue into the Christian period. The Senegambian stone circles are a later African form of tomb markers.

Ancient Egypt and Nubia

Egyptian funerary art was inseparable to the religious belief that life continued after death and that "death is a mere phase of life". Aesthetic objects and images connected with this belief were partially intended to preserve material goods, wealth and status for the journey between this life and the next, and to "commemorate the life of the tomb owner ... depict performance of the burial rites, and in general present an environment that would be conducive to the tomb owner's rebirth." In this context are the Egyptian mummies encased in one or more layers of decorated coffin, and the canopic jars preserving internal organs. A special category of

Egyptian funerary art was inseparable to the religious belief that life continued after death and that "death is a mere phase of life". Aesthetic objects and images connected with this belief were partially intended to preserve material goods, wealth and status for the journey between this life and the next, and to "commemorate the life of the tomb owner ... depict performance of the burial rites, and in general present an environment that would be conducive to the tomb owner's rebirth." In this context are the Egyptian mummies encased in one or more layers of decorated coffin, and the canopic jars preserving internal organs. A special category of Ancient Egyptian funerary texts

The literature that makes up the ancient Egyptian funerary texts is a collection of religious documents that were used in ancient Egypt, usually to help the spirit of the concerned person to be preserved in the afterlife.

They evolved over time, ...

clarify the purposes of the burial customs. The early mastaba type of tomb had a sealed underground burial chamber but an offering-chamber on the ground level for visits by the living, a pattern repeated in later types of tomb. A Ka statue effigy of the deceased might be walled up in a '' serdab'' connected to the offering chamber by vents that allowed the smell of incense

Incense is aromatic biotic material that releases fragrant smoke when burnt. The term is used for either the material or the aroma. Incense is used for aesthetic reasons, religious worship, aromatherapy, meditation, and ceremony. It may also ...

to reach the effigy. The walls of important tomb-chambers and offering chambers were heavily decorated with relief

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces are bonded to a solid background of the same material. The term '' relief'' is from the Latin verb ''relevo'', to raise. To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that th ...

s in stone or sometimes wood, or paintings, depicting religious scenes, portraits of the deceased, and at some periods vivid images of everyday life, depicting the afterlife. The chamber decoration usually centred on a "false door", through which only the soul of the deceased could pass, to receive the offerings left by the living.

Representational art

Representation is the use of signs that stand in for and take the place of something else.Mitchell, W. 1995, "Representation", in F Lentricchia & T McLaughlin (eds), ''Critical Terms for Literary Study'', 2nd edn, University of Chicago Press, Chica ...

, such as portraiture of the deceased, is found extremely early on and continues into the Roman period in the encaustic Faiyum funerary portraits applied to coffins. However, it is still hotly debated whether there was realistic portraiture in Ancient Egypt

Portraiture in ancient Egypt forms a conceptual attempt to portray "the subject from its own perspective rather than the viewpoint of the artist ... to communicate essential information about the object itself". Ancient Egyptian art was a religio ...

. The purpose of the life-sized reserve head

Reserve heads (also known as "Magical heads" or "Replacement heads", the latter term derived from the original German term "Ersatzköpfe") are distinctive sculptures made primarily of fine limestone that have been found in a number of non-royal to ...

s found in burial shafts or tombs of nobles of the Fourth dynasty is not well understood; they may have been a discreet method of eliding an edict by Khufu

Khufu or Cheops was an ancient Egyptian monarch who was the second pharaoh of the Fourth Dynasty, in the first half of the Old Kingdom period (26th century BC). Khufu succeeded his father Sneferu as king. He is generally accepted as having c ...

forbidding nobles from creating statues of themselves, or may have protected the deceased's spirit from harm or magically eliminated any evil in it, or perhaps functioned as alternate containers for the spirit if the body should be harmed in any way.

Architectural works such as the massive Great Pyramid and two smaller ones built during the Old Kingdom

In ancient Egyptian history, the Old Kingdom is the period spanning c. 2700–2200 BC. It is also known as the "Age of the Pyramids" or the "Age of the Pyramid Builders", as it encompasses the reigns of the great pyramid-builders of the Fourt ...

in the Giza Necropolis

The Giza pyramid complex ( ar, مجمع أهرامات الجيزة), also called the Giza necropolis, is the site on the Giza Plateau in Greater Cairo, Egypt that includes the Great Pyramid of Giza, the Pyramid of Khafre, and the Pyramid ...

and (much later, from about 1500 BCE) the tombs in the Valley of the Kings

The Valley of the Kings ( ar, وادي الملوك ; Late Coptic: ), also known as the Valley of the Gates of the Kings ( ar, وادي أبوا الملوك ), is a valley in Egypt where, for a period of nearly 500 years from the 16th to 11th ...

were built for royalty and the elite. The Theban Necropolis

The Theban Necropolis is a necropolis on the west bank of the Nile, opposite Thebes ( Luxor) in Upper Egypt. It was used for ritual burials for much of the Pharaonic period, especially during the New Kingdom.

Mortuary temples

* Deir el-Bah ...

was later an important site for mortuary temples and mastaba tombs. The Kushite kings who conquered Egypt and ruled as pharaohs during the Twenty-fifth Dynasty were greatly influenced by Egyptian funerary customs, employing mummification, canopic jars and '' ushabti'' funerary figurines. They also built the Nubian pyramids, which in both size and design more closely resemble the smaller Seventeenth dynasty pyramids at Thebes than those of the Old Kingdom near Memphis.

Lower-class citizens used common forms of funerary art—including '' shabti'' figurines (to perform any labor that might be required of the dead person in the afterlife), models of the scarab beetle and funerary texts—which they believed would protect them in the afterlife. During the Middle Kingdom, miniature wooden or clay models depicting scenes from everyday life became popular additions to tombs. In an attempt to duplicate the activities of the living in the afterlife, these models show laborers, houses, boats and even military formations which are scale representations of the ideal ancient Egyptian afterlife.

Ancient Greece

The ancient Greeks did not generally leave elaborate grave goods, except for a coin to pay Charon, the ferryman to Hades, and pottery; however the ''epitaphios'' or funeral oration from which the word epitaph comes was regarded as of great importance, and

The ancient Greeks did not generally leave elaborate grave goods, except for a coin to pay Charon, the ferryman to Hades, and pottery; however the ''epitaphios'' or funeral oration from which the word epitaph comes was regarded as of great importance, and animal sacrifice

Animal sacrifice is the ritual killing and offering of one or more animals, usually as part of a religious ritual or to appease or maintain favour with a deity. Animal sacrifices were common throughout Europe and the Ancient Near East until the sp ...

s were made. Those who could afford them erected stone monuments, which was one of the functions of '' kouros'' statues in the Archaic period before about 500 BCE. These were not intended as portraits, but during the Hellenistic period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

, realistic portraiture of the deceased was introduced and family groups were often depicted in bas-relief

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces are bonded to a solid background of the same material. The term '' relief'' is from the Latin verb ''relevo'', to raise. To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that th ...

on monuments, usually surrounded by an architectural frame. The walls of tomb chambers were often painted in fresco, although few examples have survived in as good condition as the Tomb of the Diver from southern Italy or the tombs at Vergina

Vergina ( el, Βεργίνα, ''Vergína'' ) is a small town in northern Greece, part of Veria municipality in Imathia, Central Macedonia. Vergina was established in 1922 in the aftermath of the population exchanges after the Treaty of ...

in Macedon. Almost the only surviving painted portraits in the classical Greek tradition are found in Egypt rather than Greece. The Fayum mummy portraits, from the very end of the classical period, were portrait faces, in a Graeco-Roman style, attached to mummies.

Early Greek burials were frequently marked above ground by a large piece of pottery, and remains were also buried in urns. Pottery continued to be used extensively inside tombs and graves throughout the classical period. The great majority of surviving ancient Greek pottery is recovered from tombs; some was apparently items used in life, but much of it was made specifically for placing in tombs, and the balance between the two original purposes is controversial. The '' larnax'' is a small coffin or ash-chest, usually of decorated terracotta

Terracotta, terra cotta, or terra-cotta (; ; ), in its material sense as an earthenware substrate, is a clay-based unglazed or glazed ceramic where the fired body is porous.

In applied art, craft, construction, and architecture, terracotta i ...

. The two-handled '' loutrophoros'' was primarily associated with weddings, as it was used to carry water for the nuptial bath. However, it was also placed in the tombs of the unmarried, "presumably to make up in some way for what they had missed in life." The one-handled '' lekythos'' had many household uses, but outside the household, its principal use was the decoration of tombs. Scenes of a descent to the underworld of Hades

Hades (; grc-gre, ᾍδης, Háidēs; ), in the ancient Greek religion and myth, is the god of the dead and the king of the underworld, with which his name became synonymous. Hades was the eldest son of Cronus and Rhea, although this also ...

were often painted on these, with the dead depicted beside Hermes

Hermes (; grc-gre, Ἑρμῆς) is an Olympian deity in ancient Greek religion and mythology. Hermes is considered the herald of the gods. He is also considered the protector of human heralds, travellers, thieves, merchants, and orato ...

, Charon or both—though usually only with Charon. Small pottery figurines are often found, though it is hard to decide if these were made especially for placement in tombs; in the case of the Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium i ...

Tanagra figurines, this seems probably not the case. But silverware is more often found around the fringes of the Greek world, as in the royal Macedon

Macedonia (; grc-gre, Μακεδονία), also called Macedon (), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, and later the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled b ...

ian tombs of Vergina

Vergina ( el, Βεργίνα, ''Vergína'' ) is a small town in northern Greece, part of Veria municipality in Imathia, Central Macedonia. Vergina was established in 1922 in the aftermath of the population exchanges after the Treaty of ...

, or in the neighbouring cultures such as those of Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to ...

or the Scythians

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Cent ...

.

The extension of the Greek world after the conquests of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

brought peoples with different tomb-making traditions into the Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium i ...

sphere, resulting in new formats for art in Greek styles. A generation before Alexander, Mausolus was a Hellenized satrap

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median and Achaemenid Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic empires.

The satrap served as viceroy to the king, though with cons ...

or semi-independent ruler under the Persian Empire, whose enormous tomb (begun 353 BCE) was wholly exceptional in the Greek world—together with the Pyramids it was the only tomb to be included in the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World

The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, also known as the Seven Wonders of the World or simply the Seven Wonders, is a list of seven notable structures present during classical antiquity. The first known list of seven wonders dates back to the 2 ...

. The exact form of the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus

The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus or Tomb of Mausolus ( grc, Μαυσωλεῖον τῆς Ἁλικαρνασσοῦ; tr, Halikarnas Mozolesi) was a tomb built between 353 and 350 BC in Halicarnassus (present Bodrum, Turkey) for Mausolus, an ...

, which gave the name to the form, is now unclear, and there are several alternative reconstructions that seek to reconcile the archaeological evidence with descriptions in literature. It had the size and some elements of the design of the Greek temple, but was much more vertical, with a square base and a pyramidal roof. There were quantities of large sculpture, of which most of the few surviving pieces are now in the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docume ...

. Other local rulers adapted the high-relief temple frieze

In architecture, the frieze is the wide central section part of an entablature and may be plain in the Ionic or Doric order, or decorated with bas-reliefs. Paterae are also usually used to decorate friezes. Even when neither columns nor ...

for very large sarcophagi, starting a tradition which was to exert a great influence on Western art up to 18th-century Neo-Classicism. The late 4th-century Alexander Sarcophagus was in fact made for another Hellenized Eastern ruler, one of a number of important sarcophagi found at Sidon

Sidon ( ; he, צִידוֹן, ''Ṣīḏōn'') known locally as Sayda or Saida ( ar, صيدا ''Ṣaydā''), is the third-largest city in Lebanon. It is located in the South Governorate, of which it is the capital, on the Mediterranean coast ...

in the modern Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to Lebanon–Syria border, the north and east and Israel to Blue ...

. The two long sides show Alexander's great victory at the Battle of Issus

The Battle of Issus (also Issos) occurred in southern Anatolia, on November 5, 333 BC between the Hellenic League led by Alexander the Great and the Achaemenid Empire, led by Darius III. It was the second great battle of Alexander's conquest of ...

and a lion hunt; such violent scenes were common on ostentatious classical sarcophagi from this period onwards, with a particular revival in Roman art of the 2nd century. More peaceful mythological scenes were popular on smaller sarcophagi, especially of Bacchus

In ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, myth, Dionysus (; grc, wikt:Διόνυσος, Διόνυσος ) is the god of the grape-harvest, winemaking, orchards and fruit, vegetation, fertility, insanity, ritual madness, religious ecstas ...

.

Etruscans

Objects connected with death, in particular sarcophagi and cinerary urns, form the basis of much of current knowledge of the ancient

Objects connected with death, in particular sarcophagi and cinerary urns, form the basis of much of current knowledge of the ancient Etruscan civilization

The Etruscan civilization () was developed by a people of Etruria in ancient Italy with a common language and culture who formed a federation of city-states. After conquering adjacent lands, its territory covered, at its greatest extent, roug ...

and its art, which once competed with the culture of ancient Rome

The culture of ancient Rome existed throughout the almost 1200-year history of the civilization of Ancient Rome. The term refers to the culture of the Roman Republic, later the Roman Empire, which at its peak covered an area from present-day L ...

, but was eventually absorbed into it. The sarcophagi and the lids of the urns often incorporate a reclining image of the deceased. The reclining figures in some Etruscan funerary art are shown using the '' mano cornuta'' to protect the grave.

The motif of the funerary art of the 7th and 6th centuries BCE was typically a feasting scene, sometimes with dancers and musicians, or athletic competitions. Household bowls, cups, and pitchers are sometimes found in the graves, along with food such as eggs, pomegranates, honey, grapes and olives for use in the afterlife. From the 5th century, the mood changed to more somber and gruesome scenes of parting, where the deceased are shown leaving their loved ones, often surrounded by underworld demons, and psychopomps, such as Charun or the winged female Vanth. The underworld figures are sometimes depicted as gesturing impatiently for a human to be taken away.Davies, 632 The handshake was another common motif, as the dead took leave of the living. This often took place in front of or near a closed double doorway, presumably the portal to the underworld. Evidence in some art, however, suggests that the "handshake took place at the other end of the journey, and represents the dead being greeted in the Underworld".

Ancient Rome

The burial customs of the

The burial customs of the ancient Romans

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom (753–509 B ...

were influenced by both of the first significant cultures whose territories they conquered as their state expanded, namely the Greeks of Magna Graecia

Magna Graecia (, ; , , grc, Μεγάλη Ἑλλάς, ', it, Magna Grecia) was the name given by the Romans to the coastal areas of Southern Italy in the present-day Italian regions of Calabria, Apulia, Basilicata, Campania and Sicily; the ...

and the Etruscans. The original Roman custom was cremation

Cremation is a method of final disposition of a dead body through burning.

Cremation may serve as a funeral or post-funeral rite and as an alternative to burial. In some countries, including India and Nepal, cremation on an open-air pyre ...

, after which the burnt remains were kept in a pot, ash-chest or urn, often in a '' columbarium''; pre-Roman burials around Rome often used hut-urns—little pottery houses. From about the 2nd century CE, inhumation

Burial, also known as interment or inhumation, is a method of final disposition whereby a dead body is placed into the ground, sometimes with objects. This is usually accomplished by excavating a pit or trench, placing the deceased and objec ...

(burial of unburnt remains) in sarcophagi, often elaborately carved, became more fashionable for those who could afford it. Greek-style medallion portrait sculptures on a ''stela'', or small mausoleum for the rich, housing either an urn or sarcophagus, were often placed in a location such as a roadside, where it would be very visible to the living and perpetuate the memory of the dead. Often a couple are shown, signifying a longing for reunion in the afterlife rather than a double burial (see married couple funerary reliefs

Funerary reliefs of married couples were common in Roman funerary art. They are one of the most common funerary portraits found on surviving freedmen reliefs. By the fourth century, a portrait of a couple on a sarcophagus from the empire did not ne ...

).

In later periods, life-size sculptures of the deceased reclining as though at a meal or social gathering are found, a common Etruscan style. Family tombs for the grandest late Roman families, like the Tomb of the Scipios, were large mausoleums with facilities for visits by the living, including kitchens and bedrooms. The Castel Sant'Angelo, built for Hadrian

Hadrian (; la, Caesar Trâiānus Hadriānus ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. He was born in Italica (close to modern Santiponce in Spain), a Roman '' municipium'' founded by Italic settlers in Hispan ...

, was later converted into a fortress. Compared to the Etruscans, though, there was less emphasis on provision of a lifestyle for the deceased, although paintings of useful objects or pleasant activities, like hunting, are seen. Ancestor portraits, usually in the form of wax masks, were kept in the home, apparently often in little cupboards, although grand patrician families kept theirs on display in the '' atrium''. They were worn in the funeral processions of members of the family by persons wearing appropriate costume for the figure represented, as described by Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ...

and Polybius

Polybius (; grc-gre, Πολύβιος, ; ) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work , which covered the period of 264–146 BC and the Punic Wars in detail.

Polybius is important for his analysis of the mixed ...

. Pliny also describes the custom of having a bust-portrait of an ancestor painted on a round bronze shield ('' clipeus''), and having it hung in a temple or other public place. No examples of either type have survived.

By the late Republic there was considerable competition among wealthy Romans for the best locations for tombs, which lined all the approach roads to the city up to the walls, and a variety of exotic and unusual designs sought to catch the attention of the passer-by and so perpetuate the memory of the deceased and increase the prestige of their family. Examples include the Tomb of Eurysaces the Baker, a freedman

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), emancipation (granted freedom ...

, the Pyramid of Cestius, and the Mausoleum of Caecilia Metella, all built within a few decades of the start of the Common Era

Common Era (CE) and Before the Common Era (BCE) are year notations for the Gregorian calendar (and its predecessor, the Julian calendar), the world's most widely used calendar era. Common Era and Before the Common Era are alternatives to the ...

.

In Italy, sarcophagi were mostly intended to be set against the wall of the tomb, and only decorated on three sides, in contrast to the free-standing styles of Greece and the Eastern Empire. The relief scenes of Hellenistic art became even more densely crowded in later Roman sarcophagi, as for example in the 2nd-century Portonaccio sarcophagus, and various styles and forms emerged, such as the columnar type with an "architectural background of columns and niches for its figures". A well-known Early Christian example is the Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus, used for an important new convert who died in 359. Many sarcophagi from leading centres were exported around the Empire. The Romans had already developed the expression of religious and philosophical ideas in narrative scenes from Greek mythology

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the origin and nature of the world, the lives and activities of ...

, treated allegorically; they later transferred this habit to Christian ideas, using biblical scenes.

China

Shang dynasty

The Shang dynasty (), also known as the Yin dynasty (), was a Dynasties in Chinese history, Chinese royal dynasty founded by Tang of Shang (Cheng Tang) that ruled in the Yellow River valley in the second millennium BC, traditionally suc ...

bronze ritual vessels were probably made for burial only; large numbers were buried in elite tombs, while other sets remained above ground for the family to use in making offerings in ancestor veneration rituals. The Tomb of Fu Hao (c. BCE 1200) is one of the few undisturbed royal tombs of the period to have been excavated—most funerary art has appeared on the art market without archaeological context.

The discovery in 1974 of the Terracotta army

The Terracotta Army is a collection of terracotta sculptures depicting the armies of Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of China. It is a form of funerary art buried with the emperor in 210–209 BCE with the purpose of protecting the emperor i ...

located the tomb of the First Qin Emperor (died 210 BCE), but the main tumulus, of which literary descriptions survive, has not been excavated. Remains surviving above ground from several imperial tombs of the Han dynasty

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Emperor Gaozu of Han, Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by th ...

show traditions maintained until the end of imperial rule. The tomb itself is an "underground palace" beneath a sealed tumulus surrounded by a wall, with several buildings set at some distance away down avenues for the observation of rites of veneration, and the accommodation of both permanent staff and those visiting to perform rites, as well as gateways, towers and other buildings.

Tang dynasty tomb figures, in "three-colour" ''

Tang dynasty tomb figures, in "three-colour" ''sancai

''Sancai'' ()Vainker, 75 is a versatile type of decoration on Chinese pottery using glazes or slip, predominantly in the three colours of brown (or amber), green, and a creamy off-white. It is particularly associated with the Tang Dynasty (61 ...

'' glazes or overglaze paint, show a wide range of servants, entertainers, animals and fierce tomb guardians between about 12 and 120 cm high, and were arranged around the tomb, often in niches along the sloping access path to the underground chamber.

Chinese imperial tombs are typically approached by a " spirit road", sometimes several kilometres long, lined by statues of guardian figures, based on both humans and animals. A tablet extolling the virtues of the deceased, mounted on a stone representation of Bixi in the form of a tortoise

Tortoises () are reptiles of the family Testudinidae of the order Testudines (Latin: ''tortoise''). Like other turtles, tortoises have a shell to protect from predation and other threats. The shell in tortoises is generally hard, and like ot ...

, is often the centerpiece of the ensemble. In Han tombs the guardian figures are mainly of "lions" and " chimeras"; in later periods they are much more varied. A looted tomb with fine paintings is the Empress Dowager Wenming tomb of the 5th century CE, and the many tombs of the 7th-century Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, t= ), or Tang Empire, was an imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907 AD, with an interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dynasty and followed by the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdo ...

Qianling Mausoleum group are an early example of a generally well-preserved ensemble.

The Goguryeo tombs, from a kingdom of the 5th to 7th centuries which included modern Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republi ...

, are especially rich in paintings. Only one of the Imperial Tombs of the Ming and Qing Dynasties has been excavated, in 1956, with such disastrous results for the conservation of the thousands of objects found, that subsequently the policy is to leave them undisturbed.

The Lei Cheng Uk Han Tomb Museum in Hong Kong displays a far humbler middle-class Han dynasty tomb, and the mid-2nd-century Wu Family tombs of Jiaxiang County

Jiaxiang County () is a county in the southwest of Shandong province, People's Republic of China. It is under the administration of Jining City.

The population was in 2011.

The cultural heritage site of the Carved Stones in the Tombs of the ...

, Shandong are the most important group of commoner tombs for funerary stones. The walls of both the offering and burial chambers of tombs of commoners from the Han period may be decorated with stone slabs carved or engraved in very low relief with crowded and varied scenes, which are now the main indication of the style of the lost palace frescoes of the period. A cheaper option was to use large clay tiles which were carved or impressed before firing. After the introduction of Buddhism, carved "funerary couches" featured similar scenes, now mostly religious. During the Han Dynasty, miniature ceramic models of buildings were often made to accompany the deceased in the graves; to them is owed much of what is known of ancient Chinese architecture. Later, during the Six Dynasties, sculptural miniatures depicting buildings, monuments, people and animals adorned the tops of the '' hunping'' funerary vessels.Dien, 214–15 The outsides of tombs often featured monumental brick or stone-carved pillar-gates (que 闕); an example from 121 CE appears to be the earliest surviving Chinese architectural structure standing above ground. Tombs of the Tang Dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, t= ), or Tang Empire, was an imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907 AD, with an interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dynasty and followed by the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdo ...

(618–907) are often rich in glazed pottery figurines of horses, servants and other subjects, whose forceful and free style is greatly admired today. The tomb art reached its peak in the Song and Jin periods; most spectacular tombs were built by rich commoners.

Early burial customs show a strong belief in an afterlife and a spirit path to it that needed facilitating. Funerals and memorials were also an opportunity to reaffirm such important cultural values as filial piety

In Confucianism, Chinese Buddhism, and Daoist ethics, filial piety (, ''xiào'') (Latin: pietas) is a virtue of respect for one's parents, elders, and ancestors. The Confucian '' Classic of Filial Piety'', thought to be written around the lat ...

and "the honor and respect due to seniors, the duties incumbent on juniors" The common Chinese funerary symbol of a woman in the door may represent a "basic male fantasy of an elysian afterlife with no restrictions: in all the doorways of the houses stand available women looking for newcomers to welcome into their chambers" Han Dynasty inscriptions often describe the filial mourning for their subjects.

Korea

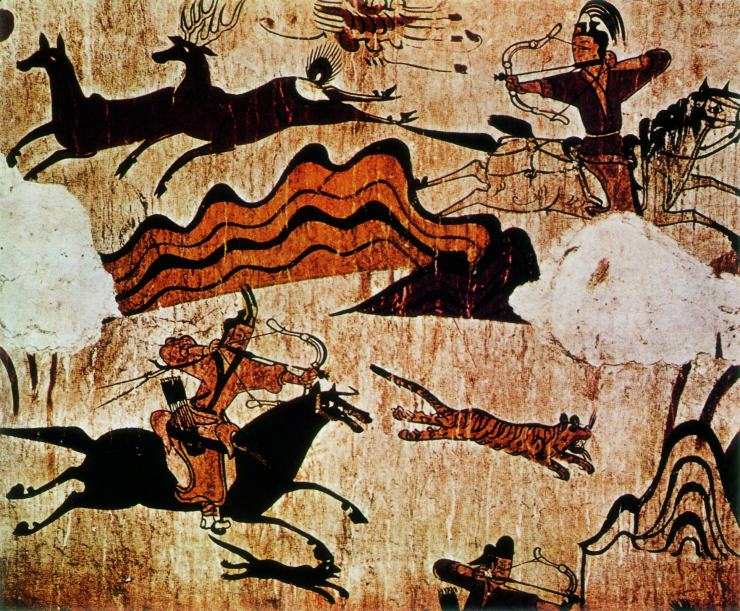

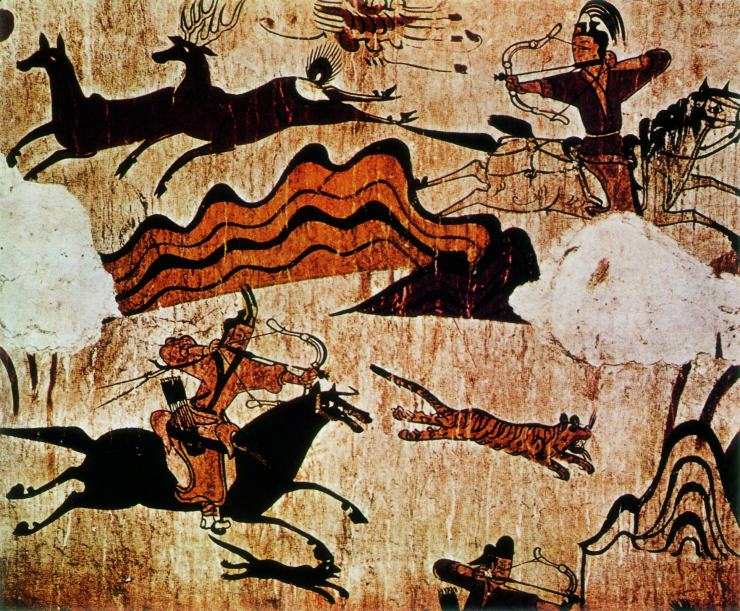

Murals painted on the walls of the Goguryeo tombs are examples of Korean painting from its

Murals painted on the walls of the Goguryeo tombs are examples of Korean painting from its Three Kingdoms

The Three Kingdoms () from 220 to 280 AD was the tripartite division of China among the dynastic states of Cao Wei, Shu Han, and Eastern Wu. The Three Kingdoms period was preceded by the Han dynasty#Eastern Han, Eastern Han dynasty and wa ...

era. Although thousands of these tombs have been found, only about 100 have murals. These tombs are often named for the dominating theme of the murals—these include the Tomb of the Dancers, the Tomb of the Hunters, the Tomb of the Four Spirits, and the Tomb of the Wrestlers. Heavenly bodies are a common motif, as are depictions of events from the lives of the royalty and nobles whose bodies had been entombed. The former include the sun, represented as a three-legged bird inside a wheel, and the various constellations, including especially the Four directional constellations: the Azure Dragon of the East, the Vermilion Bird of the South, the White Tiger of the West, and the Black Tortoise of the North.

The Royal Tombs of the Joseon Dynasty in Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republi ...

, built between 1408 and 1966, reflect a combination of Chinese and Japanese traditions, with a tomb mound, often surrounded by a screen wall of stone blocks, and sometimes with stone animal figures above ground, not unlike the Japanese ''haniwa'' figures (see below). There is usually one or more T-shaped shrine buildings some distance in front of the tomb, which is set in extensive grounds, usually with a hill behind them, and facing a view towards water and distant hills. They are still a focus for ancestor worship

The veneration of the dead, including one's ancestors, is based on love and respect for the deceased. In some cultures, it is related to beliefs that the dead have a continued existence, and may possess the ability to influence the fortune o ...

rituals. From the 15th century, they became more simple, while retaining a large landscape setting.

Japan

terracotta

Terracotta, terra cotta, or terra-cotta (; ; ), in its material sense as an earthenware substrate, is a clay-based unglazed or glazed ceramic where the fired body is porous.

In applied art, craft, construction, and architecture, terracotta i ...

''haniwa'' figures, as much as a metre high, were deposited on top of aristocratic tombs as grave markers, with others left inside, apparently representing possessions such as horses and houses for use in the afterlife. Both ''kofun'' mounds and ''haniwa'' figures appear to have been discontinued as Buddhism became the dominant Japanese religion.

Since then, Japanese tombs have been typically marked by elegant but simple rectangular vertical gravestones with inscriptions. Funerals are one of the areas in Japanese life where Buddhist customs are followed even by those who followed other traditions, such as Shinto

Shinto () is a religion from Japan. Classified as an East Asian religion by scholars of religion, its practitioners often regard it as Japan's indigenous religion and as a nature religion. Scholars sometimes call its practitioners ''Shintoist ...

. The '' bodaiji'' is a special and very common type of temple whose main purpose is as a venue for rites of ancestor worship, though it is often not the actual burial site. This was originally a custom of the feudal lords, but was adopted by other classes from about the 16th century. Each family would use a particular ''bodaiji'' over generations, and it might contain a second "grave" if the actual burial were elsewhere. Many later emperors, from the 13th to 19th centuries, are buried simply at the Imperial ''bodaiji'', the Tsuki no wa no misasagi mausoleum in the Sennyū-ji temple at Kyoto

Kyoto (; Japanese: , ''Kyōto'' ), officially , is the capital city of Kyoto Prefecture in Japan. Located in the Kansai region on the island of Honshu, Kyoto forms a part of the Keihanshin metropolitan area along with Osaka and Kobe. , the ...

.

The Americas

Unlike many Western cultures, that of

Unlike many Western cultures, that of Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area in southern North America and most of Central America. It extends from approximately central Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica. W ...

is generally lacking in sarcophagi, with a few notable exceptions such as that of Pacal the Great or the now-lost sarcophagus from the Olmec

The Olmecs () were the earliest known major Mesoamerican civilization. Following a progressive development in Soconusco, they occupied the tropical lowlands of the modern-day Mexican states of Veracruz and Tabasco. It has been speculated that ...

site of La Venta. Instead, most Mesoamerican funerary art takes the form of grave goods and, in Oaxaca

)

, population_note =

, population_rank = 10th

, timezone1 = CST

, utc_offset1 = −6

, timezone1_DST = CDT

, utc_offset1_DST = −5

, postal_code_type = Postal ...

, funerary urn

An urn is a vase, often with a cover, with a typically narrowed neck above a rounded body and a footed pedestal. Describing a vessel as an "urn", as opposed to a vase or other terms, generally reflects its use rather than any particular shape or ...

s holding the ashes of the deceased. Two well-known examples of Mesoamerican grave goods are those from Jaina Island, a Maya

Maya may refer to:

Civilizations

* Maya peoples, of southern Mexico and northern Central America

** Maya civilization, the historical civilization of the Maya peoples

** Maya language, the languages of the Maya peoples

* Maya (Ethiopia), a popu ...

site off the coast of Campeche, and those associated with the Western Mexico shaft tomb tradition

The Western Mexico shaft tomb tradition refers to a set of interlocked cultural traits found in the western Mexican states of Jalisco, Nayarit, and, to a lesser extent, Colima to its south, roughly dating to the period between 300 BCE and 400 ...

. The tombs of Mayan rulers can only normally be identified by inferences drawn from the lavishness of the grave goods and, with the possible exception of vessels made from stone rather than pottery, these appear to contain no objects specially made for the burial.

The Jaina Island graves are noted for their abundance of clay figurines. Human remains within the roughly 1,000 excavated graves on the island (out of 20,000 total) were found to be accompanied by glassware, slateware, or pottery, as well as one or more ceramic figurines, usually resting on the occupant's chest or held in their hands. The function of these figurines is not known: due to gender and age mismatches, they are unlikely to be portraits of the grave occupants, although the later figurines are known to be representations of goddesses.

The so-called shaft tomb tradition of western Mexico is known almost exclusively from grave goods, which include hollow ceramic figures, obsidian and shell jewelry, pottery, and other items (se

The Jaina Island graves are noted for their abundance of clay figurines. Human remains within the roughly 1,000 excavated graves on the island (out of 20,000 total) were found to be accompanied by glassware, slateware, or pottery, as well as one or more ceramic figurines, usually resting on the occupant's chest or held in their hands. The function of these figurines is not known: due to gender and age mismatches, they are unlikely to be portraits of the grave occupants, although the later figurines are known to be representations of goddesses.

The so-called shaft tomb tradition of western Mexico is known almost exclusively from grave goods, which include hollow ceramic figures, obsidian and shell jewelry, pottery, and other items (sethis Flickr photo

for a reconstruction). Of particular note are the various ceramic tableaux including village scenes, for example, players engaged in a Mesoamerican ballgame. Although these tableaux may merely depict village life, it has been proposed that they instead (or also) depict the underworld. Ceramic dogs are also widely known from looted tombs, and are thought by some to represent psychopomps (soul guides), although dogs were often the major source of protein in ancient Mesoamerica.

The

The Zapotec civilization

The Zapotec civilization ( "The People"; 700 BC–1521 AD) was an indigenous pre-Columbian civilization that flourished in the Valley of Oaxaca in Mesoamerica. Archaeological evidence shows that their culture originated at least 2,500 years ...

of Oaxaca is particularly known for its clay funerary urns, such as the "bat god" shown at right. Numerous types of urns have been identified. While some show deities and other supernatural beings, others seem to be portraits. Art historian George Kubler is particularly enthusiastic about the craftsmanship of this tradition:

No other American potters ever explored so completely the plastic conditions of wet clay or retained its forms so completely after firing ... heyused its wet and ductile nature for fundamental geometric modelling and cut the material, when half-dry, into smooth planes with sharp edges of an unmatched brilliance and suggestiveness of form.The Maya Naj Tunich cave tombs and other sites contain paintings, carved stelae, and grave goods in pottery,

jade

Jade is a mineral used as jewellery or for ornaments. It is typically green, although may be yellow or white. Jade can refer to either of two different silicate minerals: nephrite (a silicate of calcium and magnesium in the amphibole gro ...

and metal, including death masks. In dry areas, many ancient textiles have been found in graves from South America's Paracas culture, which wrapped its mummies tightly in several layers of elaborately patterned cloth. Elite Moche graves, containing especially fine pottery, were incorporated into large adobe

Adobe ( ; ) is a building material made from earth and organic materials. is Spanish for '' mudbrick''. In some English-speaking regions of Spanish heritage, such as the Southwestern United States, the term is used to refer to any kind of ...

structures also used for human sacrifice

Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease gods, a human ruler, an authoritative/priestly figure or spirits of dead ancestors or as a retainer sacrifice, wherei ...

s, such as the Huaca de la Luna. Andean cultures such as the Sican often practiced mummification and left grave goods in precious metals with jewels, including tumi ritual knives and gold funerary masks, as well as pottery. The Mimbres of the Mogollon culture buried their dead with bowls on top of their heads and ceremonially "killed" each bowl with a small hole in the centre so that the deceased's spirit could rise to another world. Mimbres funerary bowls show scenes of hunting, gambling, planting crops, fishing, sexual acts and births. Some of the North American mounds, such as Grave Creek Mound

The Grave Creek Mound in the Ohio River Valley in West Virginia is one of the largest conical-type burial mounds in the United States, now standing high and in diameter. The builders of the site, members of the Adena culture, moved more than ...

(c. 250–150 BCE) in West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the ...

, functioned as burial sites, while others had different purposes.

The earliest colonist graves were either unmarked, or had very simple timber headstone, with little order to their plotting, reflecting their

The earliest colonist graves were either unmarked, or had very simple timber headstone, with little order to their plotting, reflecting their Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. P ...

origins. However, a tradition of visual funerary art began to develop c. 1640, providing insights into their views of death. The lack of artistry of the earliest known headstones reflects the puritan's stern religious doctrine. Late seventeenth century examples often show a death's head; a stylized skull sometimes with wings or crossed bones, and other realistic imagery depicting humans decay into skulls, bones and dust. The style softened during the late 18th century as Unitarianism

Unitarianism (from Latin ''unitas'' "unity, oneness", from ''unus'' "one") is a nontrinitarian branch of Christian theology. Most other branches of Christianity and the major Churches accept the doctrine of the Trinity which states that there ...

and Methodism

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related Christian denomination, denominations of Protestantism, Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John W ...

became more popular.Dethlefsen; Deetz (1966) p. 508 Mid 18th century examples often show the deceased carried by the wings that would apparently take its soul to heaven.Hijiya (1983), pp. 339–63

Traditional societies

There is an enormous diversity of funeral art from traditional societies across the world, much of it in perishable materials, and some is mentioned elsewhere in the article. In traditional African societies, masks often have a specific association with death, and some types may be worn mainly or exclusively for funeral ceremonies. Akan peoples of West Africa commissioned nsodie memorial heads of royal personages. The funeral ceremonies of the

There is an enormous diversity of funeral art from traditional societies across the world, much of it in perishable materials, and some is mentioned elsewhere in the article. In traditional African societies, masks often have a specific association with death, and some types may be worn mainly or exclusively for funeral ceremonies. Akan peoples of West Africa commissioned nsodie memorial heads of royal personages. The funeral ceremonies of the Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians or Australian First Nations are people with familial heritage from, and membership in, the ethnic groups that lived in Australia before British colonisation. They consist of two distinct groups: the Aboriginal peoples o ...

typically feature body painting; the Yolngu and Tiwi people create carved '' pukumani'' burial poles from ironwood trunks, while elaborately carved burial trees have been used in south-eastern Australia. The Toraja

The Torajans are an ethnic group indigenous to a mountainous region of South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Their population is approximately 1,100,000, of whom 450,000 live in the regency of Tana Toraja ("Land of Toraja"). Most of the population is ...

people of central Sulawesi are famous for their burial practices, which include the setting-up of effigies of the dead on cliffs. The 19th- and 20th-century royal Kasubi Tombs in Uganda

}), is a landlocked country in East Africa. The country is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the south by Tanzania. The south ...

, destroyed by fire in 2010, were a circular compound of thatched buildings similar to those inhabited by the earlier Kabakas when alive, but with special characteristics.

In several cultures, goods for use in the afterlife are still interred or cremated, for example Hell bank notes in East Asian communities. In Ghana, mostly among the Ga people, elaborate figurative coffins in the shape of cars, boats or animals are made of wood. These were introduced in the 1950s by Seth Kane Kwei.

Funerary art and religion

Hinduism

Cremation

Cremation is a method of final disposition of a dead body through burning.

Cremation may serve as a funeral or post-funeral rite and as an alternative to burial. In some countries, including India and Nepal, cremation on an open-air pyre ...

is traditional among Hindus, who also believe in reincarnation

Reincarnation, also known as rebirth or transmigration, is the philosophical or religious concept that the non-physical essence of a living being begins a new life in a different physical form or body after biological death. Resurrection is ...

, and there is far less of a tradition of funerary monuments in Hinduism than in other major religions. However, there are regional, and relatively recent, traditions among royalty, and the ''samādhi mandir'' is a memorial temple for a saint. Both may be influenced by Islamic practices. The mausoleums of the kings of Orchha, from the 16th century onwards, are among the best known. Other rulers were commemorated by memorial temples of the normal type for the time and place, which like similar buildings from other cultures fall outside the scope of this article, though Angkor Wat

Angkor Wat (; km, អង្គរវត្ត, "City/Capital of Temples") is a temple complex in Cambodia and is the largest religious monument in the world, on a site measuring . Originally constructed as a Hindu temple dedicated to the g ...

in Cambodia

Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailan ...

, the most spectacular of all, must be mentioned.

Buddhism

Buddhist tombs themselves are typically simple and modest, although they may be set within temples, sometimes large complexes, built for the purpose in the then-prevailing style. According to tradition, the remains of theBuddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha, was a wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism.

According to Buddhist tradition, he was born in ...

's body after cremation

Cremation is a method of final disposition of a dead body through burning.

Cremation may serve as a funeral or post-funeral rite and as an alternative to burial. In some countries, including India and Nepal, cremation on an open-air pyre ...

were entirely divided up into relics (''cetiya

upright=1.25, Stupa">Phra Pathom Chedi, one of the biggest Chedis in Thailand; in Thai, the term Chedi (cetiya) is used interchangeably with the term Stupa

Cetiya, "reminders" or "memorials" (Sanskrit ''caitya''), are objects and places used by ...

''), which played an important part in early Buddhism. The ''stupa

A stupa ( sa, स्तूप, lit=heap, ) is a mound-like or hemispherical structure containing relics (such as '' śarīra'' – typically the remains of Buddhist monks or nuns) that is used as a place of meditation.

In Buddhism, circumam ...

'' developed as a monument enclosing deposits of relics of the Buddha from plain hemispherical mounds in the 3rd century BCE to elaborate structures such as those at Sanchi in India and Borobudur

Borobudur, also transcribed Barabudur ( id, Candi Borobudur, jv, ꦕꦤ꧀ꦝꦶꦧꦫꦧꦸꦝꦸꦂ, Candhi Barabudhur) is a 9th-century Mahayana Buddhist temple in Magelang Regency, not far from the town of Muntilan, in Central Java, Indo ...

in Java

Java (; id, Jawa, ; jv, ꦗꦮ; su, ) is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north. With a population of 151.6 million people, Java is the world's mo ...

. Regional variants such as the pagoda