Charleston, South Carolina on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Charleston is the largest city in the

U.S. state

In the United States, a state is a constituent political entity, of which there are 50. Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its sover ...

of

South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

, the

county seat

A county seat is an administrative center, seat of government, or capital city of a county or civil parish. The term is in use in Canada, China, Hungary, Romania, Taiwan, and the United States. The equivalent term shire town is used in the US st ...

of

Charleston County

Charleston County is located in the U.S. state of South Carolina along the Atlantic coast. As of the 2020 census, its population was 408,235, making it the third most populous county in South Carolina (behind Greenville and Richland counties). ...

,

and the principal city in the

Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint of South Carolina's coastline on

Charleston Harbor

The Charleston Harbor is an inlet (8 sq mi/20.7 km²) of the Atlantic Ocean at Charleston, South Carolina. The inlet is formed by the junction of Ashley and Cooper rivers at . Morris and Sullivan's Islands shelter the entrance. Charleston H ...

, an inlet of the Atlantic Ocean formed by the confluence of the

Ashley Ashley is a place name derived from the Old English words '' æsc'' (“ash”) and '' lēah'' (“meadow”). It may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Ashley (given name), a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

...

,

Cooper

Cooper, Cooper's, Coopers and similar may refer to:

* Cooper (profession), a maker of wooden casks and other staved vessels

Arts and entertainment

* Cooper (producers), alias of Dutch producers Klubbheads

* Cooper (video game character), in ...

, and

Wando rivers. Charleston had a population of 150,277 at the

2020 census.

The 2020 population of the Charleston metropolitan area, comprising

Berkeley

Berkeley most often refers to:

*Berkeley, California, a city in the United States

**University of California, Berkeley, a public university in Berkeley, California

* George Berkeley (1685–1753), Anglo-Irish philosopher

Berkeley may also refer ...

,

Charleston

Charleston most commonly refers to:

* Charleston, South Carolina

* Charleston, West Virginia, the state capital

* Charleston (dance)

Charleston may also refer to:

Places Australia

* Charleston, South Australia

Canada

* Charleston, Newfoundlan ...

, and

Dorchester counties, was 799,636 residents,

the third-largest in the state and the 74th-largest metropolitan statistical area in the United States.

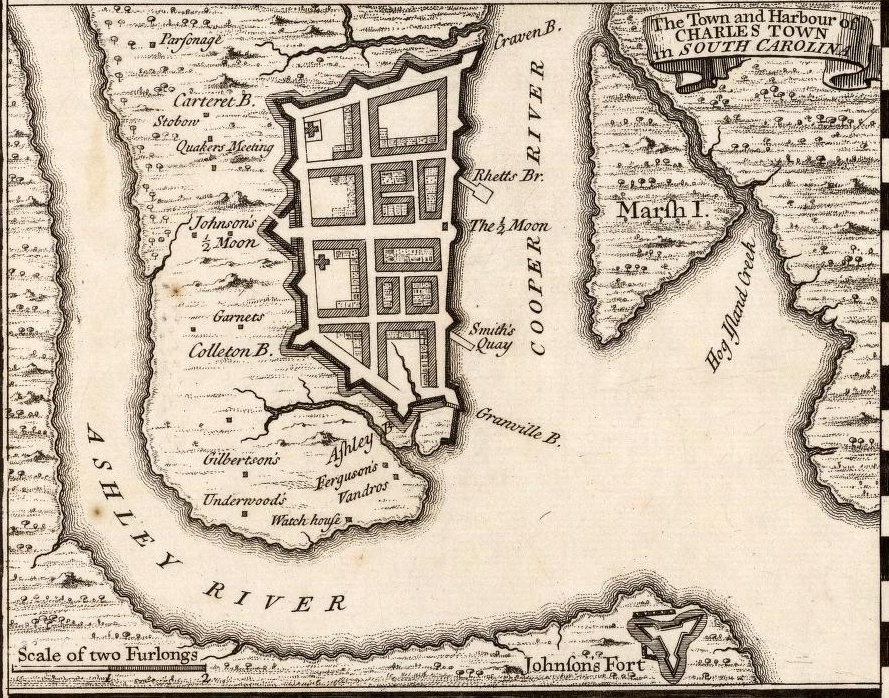

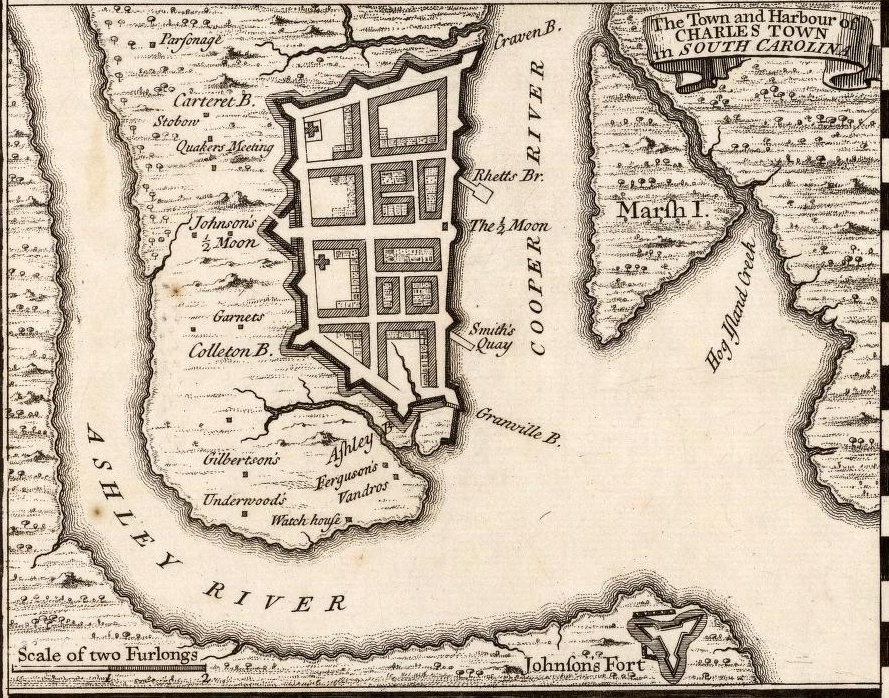

Charleston was founded in 1670 as Charles Town, honoring

King CharlesII, at Albemarle Point on the west bank of the

Ashley River

The Ashley River is a blackwater and tidal river in South Carolina, rising from the Wassamassaw and Great Cypress Swamps in western Berkeley County. It consolidates its main channel about five miles west of Summerville, widening into a ti ...

(now

Charles Towne Landing

Charles Towne Landing State Historic Site in the West Ashley area of Charleston, South Carolina preserves the original site of the first permanent English settlement in Carolina. Originally opened in 1970 to commemorate South Carolina's tricentenn ...

) but relocated in 1680 to its present site, which became the fifth-largest city in

North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

within ten years. It remained

unincorporated Unincorporated may refer to:

* Unincorporated area, land not governed by a local municipality

* Unincorporated entity, a type of organization

* Unincorporated territories of the United States, territories under U.S. jurisdiction, to which Congress ...

throughout the colonial period; its government was handled directly by a colonial legislature and a governor sent by

Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

. Election districts were organized according to

Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

parishes, and some social services were managed by Anglican

wardens and

vestries

A vestry was a committee for the local secular and ecclesiastical government for a parish in England, Wales and some English colonies which originally met in the vestry or sacristy of the parish church, and consequently became known colloquially ...

. Charleston adopted its present spelling with its incorporation as a

city

A city is a human settlement of notable size.Goodall, B. (1987) ''The Penguin Dictionary of Human Geography''. London: Penguin.Kuper, A. and Kuper, J., eds (1996) ''The Social Science Encyclopedia''. 2nd edition. London: Routledge. It can be def ...

in 1783. Population growth in the interior of South Carolina influenced the removal of the state government to

Columbia in 1788, but Charleston remained among the ten largest cities in the United States through the

1840 census

The United States census of 1840 was the sixth census of the United States. Conducted by the Census Office on June 1, 1840, it determined the resident population of the United States to be 17,069,453 – an increase of 32.7 percent over the 12, ...

.

Charleston's significance in American history is tied to its role as a major slave trading port. Charleston slave traders like

Joseph Wragg

Joseph is a common male given name, derived from the Hebrew Yosef (יוֹסֵף). "Joseph" is used, along with "Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the mo ...

were the first to break through the monopoly of the

Royal African Company

The Royal African Company (RAC) was an English mercantile (trade, trading) company set up in 1660 by the royal House of Stuart, Stuart family and City of London merchants to trade along the West Africa, west coast of Africa. It was led by the J ...

and pioneered the large-scale slave trade of the 18th century; almost one half of slaves imported to the United States arrived in Charleston. In 2018, the city formally apologized for its role in the American slave trade after CNN noted that slavery "riddles the history" of Charleston.

Geography

The city proper consists of six distinct districts.

*Downtown, or sometimes referred to as "The Peninsula", is Charleston's center city separated by the Ashley River to the west and the Cooper River to the east.

*

West Ashley

West Ashley, or more formally, west of the Ashley, is one of the six distinct areas of the city proper of Charleston, South Carolina. As of July 2022, its estimated population was 83,996. Its name is derived from the fact that the land is west of ...

, residential area to the west of Downtown bordered by the Ashley River to the east and the Stono River to the west

*

Johns Island, far western limits of Charleston, bordered by the Stono River to the east, Kiawah River to the south and

Wadmalaw Island

Wadmalaw Island is an island located in Charleston County, South Carolina, United States. It is one of the Sea Islands, a chain of tidal and barrier islands on the Atlantic Ocean.

Geography

Wadmalaw Island is located generally to the southwest o ...

to the west

*

James Island, popular residential area between Downtown and the town of

Folly Beach

Folly Beach is a public city on Folly Island in Charleston County, South Carolina, United States. The population was 2,617 at the 2010 census, up from 2,116 in 2000. Folly Beach is within the Charleston-North Charleston-Summerville metropolitan are ...

with portions of the independent town of James Island intermixed

*Cainhoy Peninsula, far eastern limits of Charleston bordered by the Wando River to the west and Nowell Creek to the east

*

Daniel Island

Daniel Island, South Carolina is a island located in the city of Charleston, South Carolina, United States. Named after its former inhabitant, the colonial governor of the Carolinas, Robert Daniell, the island is located in Berkeley County and ...

, residential area to the north of downtown, east of the Cooper River and west of the Wando River

Topography

The incorporated city fitted into as late as the

First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, but has since greatly expanded, crossing the

Ashley River

The Ashley River is a blackwater and tidal river in South Carolina, rising from the Wassamassaw and Great Cypress Swamps in western Berkeley County. It consolidates its main channel about five miles west of Summerville, widening into a ti ...

and encompassing

James Island and some of

Johns Island. The city limits also have expanded across the Cooper River, encompassing

Daniel Island

Daniel Island, South Carolina is a island located in the city of Charleston, South Carolina, United States. Named after its former inhabitant, the colonial governor of the Carolinas, Robert Daniell, the island is located in Berkeley County and ...

and the

Cainhoy

Cainhoy Historic District is a national Historic district (United States), historic district located near Huger, South Carolina, Huger, Berkeley County, South Carolina. It encompasses nine contributing buildings, which range in date from the mid- ...

area. The present city has a total area of , of which is land and is covered by water.

North Charleston

North Charleston is the third-largest city in the state of South Carolina.City Planning Department (2008-07)City of North Charleston boundary map. City of North Charleston. Retrieved January 21, 2011. On June 12, 1972, the city of North Charlest ...

blocks any expansion up the peninsula, and

Mount Pleasant occupies the land directly east of the Cooper River.

Charleston Harbor

The Charleston Harbor is an inlet (8 sq mi/20.7 km²) of the Atlantic Ocean at Charleston, South Carolina. The inlet is formed by the junction of Ashley and Cooper rivers at . Morris and Sullivan's Islands shelter the entrance. Charleston H ...

runs about southeast to the Atlantic with an average width of about , surrounded on all sides except its entrance.

Sullivan's Island lies to the north of the entrance and

Morris Island

Morris Island is an 840-acre (3.4 km²) uninhabited island in Charleston Harbor in South Carolina, accessible only by boat. The island lies in the outer reaches of the harbor and was thus a strategic location in the American Civil War. The ...

to the south. The entrance itself is about wide; it was originally only deep but began to be enlarged in the 1870s. The tidal rivers (

Wando, Cooper,

Stono

Stono, also known as Jordan's Point (pronounced "Jer-don"), is a historic home located at Lexington, Virginia. It was built about 1818, and is a cruciform shaped brick dwelling consisting of a two-story, three-bay, central section with one-stor ...

, and Ashley) are evidence of a

submergent or drowned coastline. There is a submerged river delta off the mouth of the harbor, and the Cooper River is deep.

Climate

Charleston has a

humid subtropical climate

A humid subtropical climate is a zone of climate characterized by hot and humid summers, and cool to mild winters. These climates normally lie on the southeast side of all continents (except Antarctica), generally between latitudes 25° and 40° ...

(

Köppen climate classification

The Köppen climate classification is one of the most widely used climate classification systems. It was first published by German-Russian climatologist Wladimir Köppen (1846–1940) in 1884, with several later modifications by Köppen, notabl ...

''Cfa''), with mild winters, hot humid summers, and significant rainfall all year long. Summer is the wettest season; almost half of the annual rainfall occurs from June to September in the form of

thundershower

A thunderstorm, also known as an electrical storm or a lightning storm, is a storm characterized by the presence of lightning and its acoustic effect on the Earth's atmosphere, known as thunder. Relatively weak thunderstorms are someti ...

s. Fall remains relatively warm through the middle of November. Winter is short and mild, and is characterized by occasional rain. Measurable snow (≥) has a median occurrence of only once per decade at the airport, but freezing rain is more common; a snowfall/freezing rain event on January 3, 2018, was the first such event in Charleston since December 26, 2010.

However, fell at the airport on December 23, 1989, during the

December 1989 United States cold wave

The December 1989 United States cold wave was a series of cold waves into the central and eastern United States from mid-December 1989 through Christmas. On December 21-23, a massive high pressure area pushed many areas into record lows. On the mor ...

, the largest single-day fall on record, contributing to a single-storm and seasonal record of snowfall.

Downtown Charleston's climate is considerably milder than the airport's due to stronger maritime influence. This is especially true in the winter, with the average January low in downtown being to the airport's for example.

The highest temperature recorded within city limits was on June 2, 1985, and June 24, 1944; the lowest was on

February 14, 1899. At the airport, where official records are kept, the historical range is on August 1, 1999, down to on

January 21, 1985.

Hurricanes are a major threat to the area during the summer and early fall, with several severe hurricanes hitting the area—most notably

Hurricane Hugo

Hurricane Hugo was a powerful Cape Verde tropical cyclone that inflicted widespread damage across the northeastern Caribbean and the Southeastern United States in September 1989. Across its track, Hugo affected approximately 2 million peop ...

on September 21, 1989 (a

category 4 storm). The dewpoint from June to August ranges from .

Metropolitan Statistical Area

As defined by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget, for use by the U.S. Census Bureau and other U.S. Government agencies for statistical purposes only, Charleston is included within the Charleston–North Charleston, SC Metropolitan Statistical Area and the smaller Charleston-North Charleston urban area. The

Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area consists of three counties:

Charleston

Charleston most commonly refers to:

* Charleston, South Carolina

* Charleston, West Virginia, the state capital

* Charleston (dance)

Charleston may also refer to:

Places Australia

* Charleston, South Australia

Canada

* Charleston, Newfoundlan ...

,

Berkeley

Berkeley most often refers to:

*Berkeley, California, a city in the United States

**University of California, Berkeley, a public university in Berkeley, California

* George Berkeley (1685–1753), Anglo-Irish philosopher

Berkeley may also refer ...

, and

Dorchester. As of the 2020 U.S. Census, the metropolitan statistical area had a total population of 799,636 people.

North Charleston

North Charleston is the third-largest city in the state of South Carolina.City Planning Department (2008-07)City of North Charleston boundary map. City of North Charleston. Retrieved January 21, 2011. On June 12, 1972, the city of North Charlest ...

is the second-largest city in the metro area and ranks as the third-largest city in the state;

Mount Pleasant and

Summerville are the next-largest cities. These cities combined with other incorporated and unincorporated areas along with the city of Charleston form the

Charleston-North Charleston urban area with a population of 548,404 . The metropolitan statistical area also includes a separate and much smaller urban area within Berkeley County,

Moncks Corner

Moncks Corner is a town in and the county seat of Berkeley County, South Carolina, United States. The population was 7,885 at the 2010 census. As defined by the U.S. Census Bureau, Moncks Corner is included within the Charleston-North Charleston-S ...

(with a 2000 population of 9,123).

The traditional parish system persisted until the

Reconstruction Era

The Reconstruction era was a period in American history following the American Civil War (1861–1865) and lasting until approximately the Compromise of 1877. During Reconstruction, attempts were made to rebuild the country after the bloo ...

, when counties were imposed. Nevertheless, traditional parishes still exist in various capacities, mainly as public service districts. When the city of Charleston was formed, it was defined by the limits of the Parish of St. Philip and St. Michael, now also includes parts of St. James' Parish, St. George's Parish, St. Andrew's Parish, and St. John's Parish, although the last two are mostly still incorporated rural parishes.

History

Colonial era (1670–1786)

King Charles II

King Charles II granted the

chartered Province of Carolina

Province of Carolina was a province of England (1663–1707) and Great Britain (1707–1712) that existed in North America and the Caribbean from 1663 until partitioned into North and South on January 24, 1712. It is part of present-day Alaba ...

to eight of his loyal friends, known as the

Lords Proprietors

A lord proprietor is a person granted a royal charter for the establishment and government of an English colony in the 17th century. The plural of the term is "lords proprietors" or "lords proprietary".

Origin

In the beginning of the European ...

, on March 24, 1663. In 1670,

Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

William Sayle

Captain William Sayle (c. 1590–1671) was a prominent British landholder who was Governor of Bermuda in 1643 and again in 1658. As an Independent in religion and politics, and an adherent of Oliver Cromwell, he was dissatisfied with life in Ber ...

arranged for several shiploads of settlers from

Bermuda

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type = National song

, song = " Hail to Bermuda"

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, mapsize2 =

, map_caption2 =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name =

, e ...

and

Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of the Americas, and the most easterly of the Caribbean Islands. It occupies an area of and has a population of about 287,000 (2019 estimate). ...

. These settlers established what was then called Charles Town at Albemarle Point, on the west bank of the Ashley River, a few miles northwest of the present-day city center. Charles Town became the first comprehensively planned town in the

Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of Kingdom of Great Britain, British Colony, colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Fo ...

. Its governance, settlement, and development was to follow a visionary plan known as the

Grand Model prepared for the Lords Proprietors by

John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism ...

. Because the

Carolina's Fundamental Constitutions was never ratified, however, Charles Town was never incorporated during the colonial period. Instead,

local ordinance

A local ordinance is a law issued by a local government. such as a municipality, county, parish, prefecture, or the like.

China

In Hong Kong, all laws enacted by the territory's Legislative Council remain to be known as ''Ordinances'' () af ...

s were passed by the provincial government, with day-to-day administration handled by the

wardens and

vestries

A vestry was a committee for the local secular and ecclesiastical government for a parish in England, Wales and some English colonies which originally met in the vestry or sacristy of the parish church, and consequently became known colloquially ...

of

StPhilip's and

StMichael's Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

parishes

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest, often termed a parish priest, who might be assisted by one or m ...

.

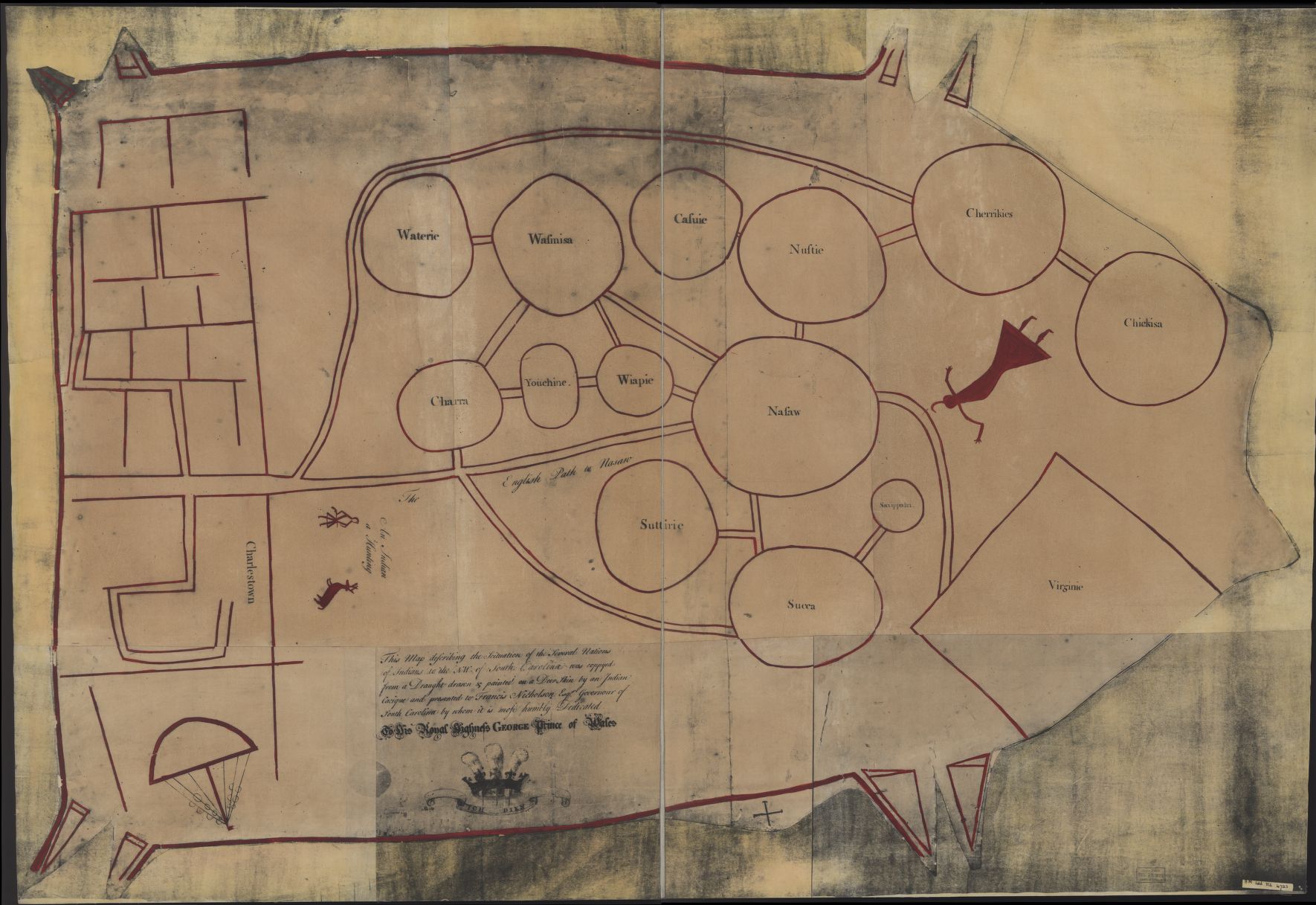

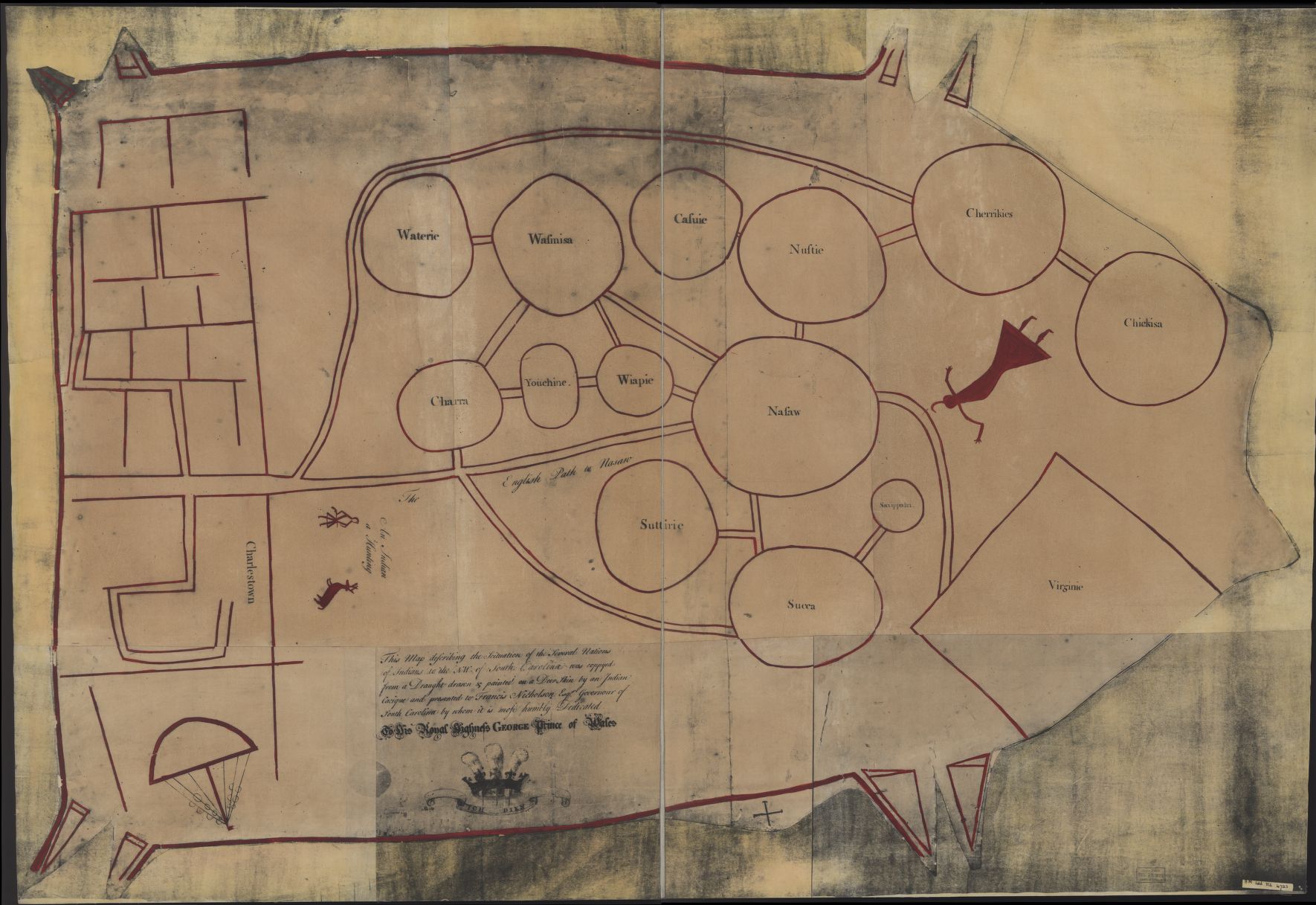

At the time of

European colonization

The historical phenomenon of colonization is one that stretches around the globe and across time. Ancient and medieval colonialism was practiced by the Phoenicians, the Greeks, the Turks, and the Arabs.

Colonialism in the modern sense began ...

, the area was inhabited by the

indigenous

Indigenous may refer to:

*Indigenous peoples

*Indigenous (ecology), presence in a region as the result of only natural processes, with no human intervention

*Indigenous (band), an American blues-rock band

*Indigenous (horse), a Hong Kong racehorse ...

Cusabo

The Cusabo or Cosabo were a group of American Indian tribes who lived along the coast of the Atlantic Ocean in what is now South Carolina, approximately between present-day Charleston and south to the Savannah River, at the time of European colon ...

, whom the settlers declared war on in October 1671. The settlers initially allied with the

Westo

The Westo were an Iroquoian Native American tribe encountered in the Southeastern U.S. by Europeans in the 17th century. They probably spoke an Iroquoian language. The Spanish called these people Chichimeco (not to be confused with Chichimeca i ...

, a northern indigenous tribe that traded in enslaved Indians. The settlers abandoned their alliance with the Westo in 1679 and allied with the Cusabo instead.

The initial settlement quickly dwindled away and disappeared while another village—established by the settlers on Oyster Point at the confluence of the Ashley and Cooper rivers around 1672—thrived. This second settlement formally replaced the original Charles Town in 1680. (The original site is now commemorated as

Charles Towne Landing

Charles Towne Landing State Historic Site in the West Ashley area of Charleston, South Carolina preserves the original site of the first permanent English settlement in Carolina. Originally opened in 1970 to commemorate South Carolina's tricentenn ...

.) The second location was more defensible and had access to a fine natural harbor. The new town had become the fifth largest in North America by 1690.

A

smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

outbreak erupted in 1698, followed by an earthquake in February 1699. The latter caused a fire that destroyed about a third of the town. During rebuilding, a

yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. In ...

outbreak killed about 15% of the remaining inhabitants. Charles Town suffered between five and eight major

yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. In ...

outbreaks over the first half of the 18th century.

It developed a reputation as one of the least healthy locations in the

Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of Kingdom of Great Britain, British Colony, colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Fo ...

for ethnic Europeans.

Malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

was endemic. Although malaria did not have such high mortality as yellow fever, it caused much illness. It was a major health problem through most of the city's history before dying out in the 1950s after use of pesticides cut down on the mosquitoes that transmitted it.

Charles Town was fortified according to a plan developed in 1704 under

Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

Nathaniel Johnson. Both

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

and

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

contested Britain's claims to the region. Various bands of

Native Americans and independent

pirates

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

also raided it.

On September 5–6, 1713 (O.S.) a violent

hurricane

A tropical cyclone is a rapidly rotating storm system characterized by a low-pressure center, a closed low-level atmospheric circulation, strong winds, and a spiral arrangement of thunderstorms that produce heavy rain and squalls. Depend ...

passed over Charles Town. The

Circular Congregational Church

The Circular Congregational Church is a historic church building at 150 Meeting Street in Charleston, South Carolina, used by a congregation established in 1681. Its parish house, the Parish House of the Circular Congregational Church, is a highly ...

manse was damaged during the storm, in which church records were lost. Much of Charles Town was flooded as "the Ashley and Cooper rivers became one." At least seventy people died in the disaster.

From the 1670s Charleston attracted pirates. The combination of a weak government and corruption made the city popular with pirates, who frequently visited and raided the city. Charles Town was besieged by the pirate

Blackbeard for several days in May 1718. Blackbeard released his hostages and left in exchange for a chest of medicine from

Governor Robert Johnson.

[D. Moore. (1997) "A General History of Blackbeard the Pirate, the Queen Anne's Revenge and the Adventure". In ;;Tributaries,;; Volume VII, 1997. pp. 31–35. (North Carolina Maritime History Council)]

Around 1719, the town's name began to be generally written as Charlestown and, excepting those fronting the Cooper River, the old walls were largely removed over the next decade. Charlestown was a center for the inland colonization of

South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

. It remained the southernmost point of the

Southern Colonies until the

Province of Georgia

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman ''provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions outs ...

was established in 1732. As noted, the first settlers primarily came from

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

,

Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of the Americas, and the most easterly of the Caribbean Islands. It occupies an area of and has a population of about 287,000 (2019 estimate). ...

and

Bermuda

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type = National song

, song = " Hail to Bermuda"

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, mapsize2 =

, map_caption2 =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name =

, e ...

. The Barbadian and Bermudan immigrants were planters who brought enslaved Africans with them, having purchased them in the

West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

.

Early immigrant groups to the city included the

Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

s,

Scottish

Scottish usually refers to something of, from, or related to Scotland, including:

*Scottish Gaelic, a Celtic Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family native to Scotland

*Scottish English

*Scottish national identity, the Scottish ide ...

,

Irish, and

Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

, as well as

hundreds of Jews, predominately

Sephardi

Sephardic (or Sephardi) Jews (, ; lad, Djudíos Sefardíes), also ''Sepharadim'' , Modern Hebrew: ''Sfaradim'', Tiberian Hebrew, Tiberian: Səp̄āraddîm, also , ''Ye'hude Sepharad'', lit. "The Jews of Spain", es, Judíos sefardíes (or ), ...

from

London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

and major cities of the

Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands (Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiography ...

, where they had been given refuge.

As late as 1830, Charleston's Jewish community was the largest and wealthiest

in North America.

[

By 1708, the majority of the colony's population were ]Black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white have o ...

Africans. They had been brought to Charlestown via the Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and i ...

, first as indentured servants and then as slaves

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

. In the early 1700s, Charleston's largest slave trader, Joseph Wragg

Joseph is a common male given name, derived from the Hebrew Yosef (יוֹסֵף). "Joseph" is used, along with "Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the mo ...

, pioneered the settlement's involvement in the slave trade. Of the estimated 400,000 captive Africans transported to North America to be sold into slavery, 40% are thought to have landed at Sullivan's Island off Charlestown. Free people of color

In the context of the history of slavery in the Americas, free people of color (French: ''gens de couleur libres''; Spanish: ''gente de color libre'') were primarily people of mixed African, European, and Native American descent who were not ...

also migrated from the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

, being descendants of white planters and their Black consorts, and unions among the working classes.[History: Gadsden's Wharf](_blank)

, International African American Museum; accessed March 29, 2018 Devoted to plantation agriculture that depended on enslaved labor, South Carolina became a slave society: it had a majority-Black population from the colonial period until after the Great Migration of the early 20th century, when many rural Blacks moved to northern and midwestern industrial cities to escape Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

.

At the foundation of the town, the principal items of commerce were

At the foundation of the town, the principal items of commerce were pine

A pine is any conifer tree or shrub in the genus ''Pinus'' () of the family Pinaceae. ''Pinus'' is the sole genus in the subfamily Pinoideae. The World Flora Online created by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and Missouri Botanical Garden accep ...

timber

Lumber is wood that has been processed into dimensional lumber, including beams and planks or boards, a stage in the process of wood production. Lumber is mainly used for construction framing, as well as finishing (floors, wall panels, wi ...

and pitch for ships

A ship is a large watercraft that travels the world's oceans and other sufficiently deep waterways, carrying cargo or passengers, or in support of specialized missions, such as defense, research, and fishing. Ships are generally distinguished ...

and tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

. The early economy developed around the deerskin trade, in which colonists used alliances with the Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

and Creek

A creek in North America and elsewhere, such as Australia, is a stream that is usually smaller than a river. In the British Isles it is a small tidal inlet.

Creek may also refer to:

People

* Creek people, also known as Muscogee, Native Americans

...

peoples to secure the raw material.

At the same time, Indians took each other as captives and slaves in warfare. From 1680 to 1720, approximately 40,000 native men, women, and children were sold through the port, principally to the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

such as (Bermuda

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type = National song

, song = " Hail to Bermuda"

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, mapsize2 =

, map_caption2 =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name =

, e ...

and the Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to ...

), but also to other Southern colonies.plantations

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. The ...

.Spanish Florida

Spanish Florida ( es, La Florida) was the first major European land claim and attempted settlement in North America during the European Age of Discovery. ''La Florida'' formed part of the Captaincy General of Cuba, the Viceroyalty of New Spain, ...

and French Louisiana in the 1700s during the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phil ...

.[ But it also provoked the ]Yamasee War

The Yamasee War (also spelled Yamassee or Yemassee) was a conflict fought in South Carolina from 1715 to 1717 between British settlers from the Province of Carolina and the Yamasee and a number of other allied Native American peoples, incl ...

of the 1710s that nearly destroyed the colony. After that, South Carolina largely abandoned the Indian slave trade.[

The area's unsuitability for growing ]tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

prompted the Lowcountry planters

Planters Nut & Chocolate Company is an American snack food company now owned by Hormel Foods. Planters is best known for its processed nuts and for the Mr. Peanut icon that symbolizes them. Mr. Peanut was created by grade schooler Antonio Gentil ...

to experiment with other cash crop

A cash crop or profit crop is an Agriculture, agricultural crop which is grown to sell for profit. It is typically purchased by parties separate from a farm. The term is used to differentiate marketed crops from staple crop (or "subsistence crop") ...

s. The profitability of growing rice led the planters to pay premiums for slaves from the "Rice Coast" who knew its cultivation; their descendants make up the ethnic Gullah who created their own culture and language in this area. Slaves imported from the Caribbean showed the planter George Lucas's daughter Eliza how to raise and use

Use may refer to:

* Use (law), an obligation on a person to whom property has been conveyed

* Use (liturgy), a special form of Roman Catholic ritual adopted for use in a particular diocese

* Use–mention distinction, the distinction between using ...

indigo

Indigo is a deep color close to the color wheel blue (a primary color in the RGB color space), as well as to some variants of ultramarine, based on the ancient dye of the same name. The word "indigo" comes from the Latin word ''indicum'', m ...

for dyeing in 1747.

Throughout this period, the slaves were sold aboard the arriving ships or at ad hoc gatherings in town's taverns.[ Runaways and minor ]slave rebellion

A slave rebellion is an armed uprising by enslaved people, as a way of fighting for their freedom. Rebellions of enslaved people have occurred in nearly all societies that practice slavery or have practiced slavery in the past. A desire for freedo ...

s prompted the 1739 Security Act, which required all white men to carry weapons at all times (even to church on Sundays). Before it had fully taken effect, the Cato or Stono Rebellion

The Stono Rebellion (also known as Cato's Conspiracy or Cato's Rebellion) was a slave revolt that began on 9 September 1739, in the colony of South Carolina. It was the largest slave rebellion in the Southern Colonies, with 25 colonists and 35 t ...

broke out. The white community had recently been decimated by a malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

outbreak, and the rebels killed about 25 white people before being stopped by the colonial militia. As a result of their fears of rebellion, whites killed a total of 35 to 50 Black people.

The planters attributed the violence to recently imported Africans and agreed to a 10-year moratorium on slave importation through Charlestown. They relied for labor upon the slave communities they already held. The 1740 Negro Act also tightened controls, requiring a ratio of one white for every ten Blacks on any plantation (which was often not achieved), and banning slaves from assembling together, growing their own food, earning money, or learning to read. Drums

A drum kit (also called a drum set, trap set, or simply drums) is a collection of drums, cymbals, and other Percussion instrument, auxiliary percussion instruments set up to be played by one person. The player (drummer) typically holds a pair o ...

were banned because Africans used them for signaling; slaves were allowed to use string and other instruments. When the moratorium expired and Charlestown reopened to the slave trade in 1750, the memory of the Stono Rebellion resulted in traders avoiding buying slaves from the Congo

Congo or The Congo may refer to either of two countries that border the Congo River in central Africa:

* Democratic Republic of the Congo, the larger country to the southeast, capital Kinshasa, formerly known as Zaire, sometimes referred to a ...

and Angola

, national_anthem = " Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordina ...

, whose populations had a reputation for independence.

By the mid-18th century, Charlestown was the hub of the Atlantic slave trade in the Southern Colonies. Even with the decade-long moratorium, its customs processed around 40% of the enslaved Africans brought to North America between 1700 and 1775,plantations

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. The ...

and the economy

An economy is an area of the production, distribution and trade, as well as consumption of goods and services. In general, it is defined as a social domain that emphasize the practices, discourses, and material expressions associated with the ...

based on them made this the wealthiest city in the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of Kingdom of Great Britain, British Colony, colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Fo ...

and the largest in population south of Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

. In 1770, the city had 11,000 inhabitants—half slaves—and was the 4th-largest port in the colonies, after Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, and Philadelphia.

The elite began to use their wealth to encourage cultural and social development. America's first theater building was constructed here in 1736; it was later replaced by today's Dock Street Theater. StMichael's was erected in 1753. Benevolent societies were formed by the Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

s, free people of color, Germans, and Jews. The Library Society was established in 1748 by well-born young men who wanted to share the financial cost to keep up with the scientific and philosophical issues of the day.

American Revolution (1776–1783)

Delegates for the

Delegates for the Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislative bodies, with some executive function, for thirteen of Britain's colonies in North America, and the newly declared United States just before, during, and after the American Revolutionary War. ...

were elected in 1774, and South Carolina declared its independence from Britain on the steps of the Exchange. Slavery was again an important factor in the city's role during the Revolutionary War. The British attacked the settlement three times, assuming that the settlement had a large base of Loyalists who would rally to their cause once given some military support. The loyalty of white Southerners towards the Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has different ...

had largely been forfeited, however, by British legal cases (such as the 1772 Somersett case

''Somerset v Stewart'' (177298 ER 499(also known as ''Somersett's case'', ''v. XX Sommersett v Steuart and the Mansfield Judgment)'' is a judgment of the English Court of King's Bench in 1772, relating to the right of an enslaved person on En ...

which marked the prohibition of slavery in England and Wales

England and Wales () is one of the three legal jurisdictions of the United Kingdom. It covers the constituent countries England and Wales and was formed by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542. The substantive law of the jurisdiction is Eng ...

; a significant milestone in the abolitionist struggle) and military tactics (such as Dunmore's Proclamation in 1775) that promised the emancipation of slaves owned by Patriot planters; these efforts did, however, unsurprisingly win the allegiance of thousands of Black Loyalists.

The Battle of Sullivan's Island saw the British fail to capture a partially constructed palmetto palisade from Col. Moultrie's militia regiment on June 28, 1776. The Liberty Flag used by Moultrie's men formed the basis of the later South Carolina flag

The flag of South Carolina is a symbol of the U.S. state of South Carolina consisting of a blue field with a white palmetto tree and white crescent. Roots of this design have existed in some form since 1775, being based on one of the first Re ...

, and the victory's anniversary continues to be commemorated as Carolina Day

The following are minor or locally celebrated holidays related to the American Revolution.

A Great Jubilee Day

A Great Jubilee Day, first organized May 26, 1783 in North Stratford, now Trumbull, Connecticut, celebrated end of major fighting in th ...

.

Making the capture of Charlestown their chief priority, the British sent Sir Henry Clinton, who laid siege to Charleston on April 1, 1780, with about 14,000 troops and 90 ships. Bombardment began on March 11, 1780. The Patriots, led by Benjamin Lincoln, had about 5,500 men and inadequate fortifications to repel the forces against them. After the British cut his supply lines and lines of retreat at the battles of Monck's Corner

Moncks Corner is a town in and the county seat of Berkeley County, South Carolina, United States. The population was 7,885 at the 2010 census. As defined by the U.S. Census Bureau, Moncks Corner is included within the Charleston-North Charleston-S ...

and Lenud's Ferry, Lincoln's surrender on May 12, 1780 became the greatest American defeat of the war.

The British continued to hold Charlestown for over a year following their defeat at Yorktown in 1781, although they alienated local planters by refusing to restore full civil government. Nathanael Greene had entered the state after Cornwallis's pyrrhic victory

A Pyrrhic victory ( ) is a victory that inflicts such a devastating toll on the victor that it is tantamount to defeat. Such a victory negates any true sense of achievement or damages long-term progress.

The phrase originates from a quote from P ...

at Guilford Courthouse

The Battle of Guilford Court House was on March 15, 1781, during the American Revolutionary War, at a site that is now in Greensboro, the seat of Guilford County, North Carolina. A 2,100-man British force under the command of Lieutenant General ...

and kept the area under a kind of siege. British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

officer Alexander Leslie

Alexander Leslie, 1st Earl of Leven (15804 April 1661) was a Scottish soldier in Swedish and Scottish service. Born illegitimate and raised as a foster child, he subsequently advanced to the rank of a Swedish Field Marshal, and in Scotland be ...

, commanding Charlestown, requested a truce in March 1782 to purchase food for his garrison and the town's inhabitants. Greene refused and formed a brigade under Mordecai Gist

Mordecai Gist (1743–1792) was a member of a prominent Maryland family who became a brigadier general in command of the Maryland Line in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War.

Life

Gist was born in Baltimore, Maryland (one ...

to counter British forays. Charlestown was finally evacuated by the British in December 1782. Greene presented the British leaders of the town with the Moultrie Flag.

Antebellum era (1783–1861)

Between the Revolutionary War and the Civil War, Charleston experienced an economic boom, at least for the top strata of society. The expansion of cotton as a cash crop in the South both led to huge wealth for a small segment of society and funded impressive architecture and culture but also escalated the importance of slaves and led to greater and greater restrictions on Black Charlestonians.

By 1783, the growth of the city had reached a point where a municipal government because desirable; therefore on August 13, 1783, an act of incorporation for the city of Charleston was ratified. The act originally specified the city's name as "Charles Ton," as opposed to the previous Charlestown, but the spelling "Charleston" quickly came to dominate.

Although Columbia had replaced it as the state capital in 1788, Charleston became even more prosperous as

Between the Revolutionary War and the Civil War, Charleston experienced an economic boom, at least for the top strata of society. The expansion of cotton as a cash crop in the South both led to huge wealth for a small segment of society and funded impressive architecture and culture but also escalated the importance of slaves and led to greater and greater restrictions on Black Charlestonians.

By 1783, the growth of the city had reached a point where a municipal government because desirable; therefore on August 13, 1783, an act of incorporation for the city of Charleston was ratified. The act originally specified the city's name as "Charles Ton," as opposed to the previous Charlestown, but the spelling "Charleston" quickly came to dominate.

Although Columbia had replaced it as the state capital in 1788, Charleston became even more prosperous as Eli Whitney

Eli Whitney Jr. (December 8, 1765January 8, 1825) was an American inventor, widely known for inventing the cotton gin, one of the key inventions of the Industrial Revolution that shaped the economy of the Antebellum South.

Although Whitney hi ...

's 1793 invention of the cotton gin

A cotton gin—meaning "cotton engine"—is a machine that quickly and easily separates cotton fibers from their seeds, enabling much greater productivity than manual cotton separation.. Reprinted by McGraw-Hill, New York and London, 1926 (); a ...

sped the processing of the crop over 50 times. Britain's Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

—initially built upon its textile industry

The textile industry is primarily concerned with the design, production and distribution of yarn, cloth and clothing. The raw material may be natural, or synthetic using products of the chemical industry.

Industry process

Cotton manufacturi ...

—took up the extra production ravenously and cotton became Charleston's major export commodity in the 19th century.

The Bank of South Carolina, the second-oldest building in the nation to be constructed as a bank, was established in 1798; branches of the First

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

and Second Bank of the United States were also located in Charleston in 1800 and 1817.

Throughout the Antebellum Period, Charleston continued to be the only major American city with a majority-slave population.[ The city widespread use of slaves as workers was a frequent subject of writers and visitors: a merchant from Liverpool noted in 1834 that "almost all the working population are Negroes, all the servants, the carmen & porters, all the people who see at the stalls in Market, and most of the Journeymen in trades".]Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and i ...

in 1794 and all importation of slaves was banned in 1808, but American merchantmen frequently refused to permit British inspection for enslaved cargo, and smuggling remained common. Much more important was the domestic slave trade, which boomed as the Deep South was developed in new cotton plantations. As a result of the trade, there was a forced migration of more than one million slaves from the Upper South to the Lower South in the antebellum years. During the early 19th century, the first dedicated slave markets were founded in Charleston, mostly near Chalmers and State streets.[ Many domestic slavers used Charleston as a port in what was called the coastwise trade, traveling to such ports as Mobile and New Orleans.

Slave ownership was the primary marker of class and even the town's freedmen and ]free people of color

In the context of the history of slavery in the Americas, free people of color (French: ''gens de couleur libres''; Spanish: ''gente de color libre'') were primarily people of mixed African, European, and Native American descent who were not ...

typically kept slaves if they had the wealth to do so. Visitors commonly remarked on the sheer number of Blacks in Charleston and their seeming freedom of movement, though in fact—mindful of the Stono Rebellion

The Stono Rebellion (also known as Cato's Conspiracy or Cato's Rebellion) was a slave revolt that began on 9 September 1739, in the colony of South Carolina. It was the largest slave rebellion in the Southern Colonies, with 25 colonists and 35 t ...

and the slave revolution that established Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

—the whites closely regulated the behavior of both slaves and free people of color. Wages and hiring practices were fixed, identifying badges were sometimes required, and even work songs were sometimes censored. Punishment was handled out of sight by the city's workhouse

In Britain, a workhouse () was an institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. (In Scotland, they were usually known as poorhouses.) The earliest known use of the term ''workhouse'' ...

, whose fees provided the municipal government with thousands a year.manumission

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing enslaved people by their enslavers. Different approaches to manumission were developed, each specific to the time and place of a particular society. Historian Verene Shepherd states that t ...

(freeing a slave) required legislative approval, effectively halting the practice.[

The effects of slavery were pronounced on white society as well. The high cost of 19th-century slaves and their high rate of return combined to institute an oligarchic society controlled by about ninety interrelated families, where 4% of the free population controlled half of the wealth, and the lower half of the free population—unable to compete with owned or rented slaves—held no wealth at all.][ The white middle class was minimal: Charlestonians generally disparaged hard work as the lot of slaves.][ ]Olmsted Olmsted may refer to:

People

* Olmsted (name)

Places

* Olmsted Air Force Base, inactive since 1969

* Olmsted, Illinois

* Olmsted County, Minnesota

* Olmsted Falls, Ohio

* Olmsted Point, a viewing area in Yosemite National Park

* Olmsted Townshi ...

considered their civic elections "entirely contests of money and personal influence" and the oligarchs dominated civic planning: the lack of public parks and amenities was noted, as was the abundance of private gardens in the wealthy's walled estates.

In the 1810s, the town's churches intensified their discrimination against their Black parishioners, culminating in Bethel Methodist's 1817 construction of a hearse house over its Black burial ground. 4,376 Black Methodists joined Morris Brown in establishing Hampstead Church

The Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, often referred to as Mother Emanuel, is a church in Charleston, South Carolina. Founded in 1817, Emanuel AME is the oldest African Methodist Episcopal church in the Southern United States. Thi ...

, the African Methodist Episcopal

The African Methodist Episcopal Church, usually called the AME Church or AME, is a predominantly African American Methodist denomination. It adheres to Wesleyan-Arminian theology and has a connexional polity. The African Methodist Episcopal ...

church now known as Mother Emanuel.[ State and city laws prohibited Black literacy, limited Black worship to daylight hours, and required a majority of any church's parishioners be white. In June 1818, 140 Black church members at ]Hampstead Church

The Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, often referred to as Mother Emanuel, is a church in Charleston, South Carolina. Founded in 1817, Emanuel AME is the oldest African Methodist Episcopal church in the Southern United States. Thi ...

were arrested and eight of its leaders given fines and ten lashes; police raided the church again in 1820 and pressured it in 1821.Denmark Vesey

Denmark Vesey (also Telemaque) ( July 2, 1822) was an early 19th century free Black and community leader in Charleston, South Carolina, who was accused and convicted of planning a major slave revolt in 1822. Although the alleged plot was dis ...

, a lay preacher[ and carpenter who had bought his freedom after winning a lottery, planned an uprising and escape to ]Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

—initially for Bastille Day—that failed when one slave revealed the plot to his master. Over the next month, the city's intendant (mayor) James Hamilton Jr.

James Hamilton Jr. (May 8, 1786 – November 15, 1857) was an American lawyer and politician. He represented South Carolina in the U.S. Congress (1822–1829) and served as its 53rd governor (1830–1832). Prior to that he achieved widespread r ...

organized a militia for regular patrols, initiated a secret and extrajudicial tribunal to investigate, and hanged 35 and exiled 35[ or 37 slaves to Spanish Cuba for their involvement.][ and erected a new arsenal. This structure later was the basis of the Citadel's first campus. The AME congregation built a new church but in 1834 the city banned it and all Black worship services, following Nat Turner's 1831 rebellion in Virginia. The estimated 10% of slaves who came to America as ]Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abraha ...

never had a separate mosque

A mosque (; from ar, مَسْجِد, masjid, ; literally "place of ritual prostration"), also called masjid, is a place of prayer for Muslims. Mosques are usually covered buildings, but can be any place where prayers ( sujud) are performed, ...

. Slaveholders sometimes provided them with beef rations in place of pork in recognition of religious traditions.

The registered tonnage

Tonnage is a measure of the cargo-carrying capacity of a ship, and is commonly used to assess fees on commercial shipping. The term derives from the taxation paid on ''tuns'' or casks of wine. In modern maritime usage, "tonnage" specifically ref ...

of Charleston shipping in 1829 was 12,410. In 1832, South Carolina passed an ordinance of nullification, a procedure by which a state could, in effect, repeal a federal law; it was directed against the most recent tariff

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and poli ...

acts. Soon, federal soldiers were dispensed to Charleston's forts, and five United States Coast Guard cutters were detached to Charleston Harbor "to take possession of any vessel arriving from a foreign port, and defend her against any attempt to dispossess the Customs Officers of her custody until all the requirements of law have been complied with." This federal action became known as the Charleston incident. The state's politicians worked on a compromise law in Washington to gradually reduce the tariffs.

Charleston's embrace of classical architecture began after a devastating fire leveled much of the city. On April 27, 1838, Charleston suffered a catastrophic fire that burned more than 1000 buildings and caused about $3 million in damage at the time. The damaged buildings amounted to about one-fourth of all the businesses in the main part of the city. When the many homes and business were rebuilt or repaired, a great cultural awakening occurred. Previous to the fire, only a few homes were styled as Greek Revival; many residents decided to construct new buildings in that style after the conflagration. This tradition continued and made Charleston one of the foremost places to view Greek Revival

The Greek Revival was an architectural movement which began in the middle of the 18th century but which particularly flourished in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, predominantly in northern Europe and the United States and Canada, but ...

architecture. The Gothic Revival

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic, neo-Gothic, or Gothick) is an architectural movement that began in the late 1740s in England. The movement gained momentum and expanded in the first half of the 19th century, as increasingly ...

also made a significant appearance in the construction of many churches after the fire that exhibited picturesque forms and reminders of devout European religion.

By 1840, the Market Hall and Sheds, where fresh meat and produce were brought daily, became a hub of commercial activity. The slave trade

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

also depended on the port of Charleston, where ships could be unloaded and the slaves bought and sold. The legal importation of African slaves had ended in 1808, although smuggling was significant. However, the domestic trade was booming. More than one million slaves were transported from the Upper South to the Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion in the Southern United States. The term was first used to describe the states most dependent on plantations and slavery prior to the American Civil War. Following the war ...

in the antebellum years, as cotton plantations were widely developed through what became known as the Black Belt

Black Belt may refer to:

Martial arts

* Black belt (martial arts), an indication of attainment of expertise in martial arts

* ''Black Belt'' (magazine), a magazine covering martial arts news, technique, and notable individuals

Places

* Black B ...

. Many slaves were transported in the coastwise slave trade

The coastwise slave trade existed along the eastern coastal areas of the United States in the antebellum years prior to 1861. Shiploads and boatloads of slaves in the domestic trade were transported from place to place on the waterways. Hundreds of ...

, with slave ships stopping at ports such as Charleston.

Civil War (1861–1865)

Charleston played a major part in the Civil War. As a pivotal city, both the Union and Confederate Armies vied for control of it. The Civil War began in

Charleston played a major part in the Civil War. As a pivotal city, both the Union and Confederate Armies vied for control of it. The Civil War began in Charleston Harbor

The Charleston Harbor is an inlet (8 sq mi/20.7 km²) of the Atlantic Ocean at Charleston, South Carolina. The inlet is formed by the junction of Ashley and Cooper rivers at . Morris and Sullivan's Islands shelter the entrance. Charleston H ...

in 1861, and ended mere months after the Union forces took control of Charleston in 1865.

Following the election

''The Election'' () is a political drama series produced by Hong Kong Television Network (HKTV). With a budget of HK$15 million, filming started in July 2014 and wrapped up on 28 October 2014. Popularly voted to be the inaugural drama of ...

of Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

, the South Carolina General Assembly

The South Carolina General Assembly, also called the South Carolina Legislature, is the state legislature of the U.S. state of South Carolina. The legislature is bicameral and consists of the lower South Carolina House of Representatives and t ...

voted on December 20, 1860, to secede from the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

. South Carolina was the first state to secede. On December 27, Castle Pinckney was surrendered by its garrison to the state militia and, on January 9, 1861, Citadel

A citadel is the core fortified area of a town or city. It may be a castle, fortress, or fortified center. The term is a diminutive of "city", meaning "little city", because it is a smaller part of the city of which it is the defensive core.

In ...

cadets opened fire on the USS'' Star of the West'' as it entered Charleston Harbor.

The first full battle of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

occurred on April 12, 1861, when shore batteries under the command of General Beauregard

Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard (May 28, 1818 - February 20, 1893) was a Confederate general officer of Louisiana Creole descent who started the American Civil War by leading the attack on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861. Today, he is commonly ...

opened fire on the held Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. After a 34-hour bombardment, Major Robert Anderson

Robert Anderson (June 14, 1805 – October 26, 1871) was a United States Army officer during the American Civil War. He was the Union commander in the first battle of the American Civil War at Battle of Fort Sumter, Fort Sumter in April 1861 whe ...

surrendered the fort.

On December 11, 1861, an enormous fire burned over of the city.

Union control of the sea permitted the repeated bombardment of the city, causing vast damage.[ Although Admiral Du Pont's naval assault on the town's forts in April 1863 failed, the Union navy's blockade shut down most commercial traffic. Over the course of the war, some ]blockade runners

A blockade runner is a merchant vessel used for evading a naval blockade of a port or strait. It is usually light and fast, using stealth and speed rather than confronting the blockaders in order to break the blockade. Blockade runners usuall ...

got through but not a single one made it into or out of the Charleston Harbor between August 1863 and March 1864.[Craig L. Symonds, ''The Civil War at Sea'' (2009) p. 57] The early submarine ''H.L. Hunley

''H. L. Hunley'', often referred to as ''Hunley'', '' CSS H. L. Hunley'', or as ''CSS Hunley'', was a submarine of the Confederate States of America that played a small part in the American Civil War. ''Hunley'' demonstrated the advantages and th ...

'' made a night attack on the on February 17, 1864.

General Gillmore's land assault in July 1864 was unsuccessful but the fall of Columbia and advance of General William T. Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman ( ; February 8, 1820February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), achieving recognition for his com ...

's army through the state prompted the Confederates to evacuate the town on February 17, 1865, burning the public buildings, cotton warehouses, and other sources of supply before their departure. Union troops moved into the city within the month. The War Department recovered what federal property remained and also confiscated the campus of the Citadel Military Academy and used it as a federal garrison for the next 17 years. The facilities were finally returned to the state and reopened as a military college in 1882 under the direction of Lawrence E. Marichak.

Postbellum (1865–1945)

Reconstruction

After the defeat of the Confederacy, federal forces remained in Charleston during Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

. The war had shattered the city's prosperity, but the African-American population surged (from 17,000 in 1860 to over 27,000 in 1880) as freedmen moved from the countryside to the major city.[Jeffrey G. Strickland, ''Ethnicity And Race In The Urban South: German Immigrants And African-Americans In Charleston, South Carolina During Reconstruction'', 2003, p. 11, Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations. Paper 1541](_blank)

Blacks quickly left the Southern Baptist Church and resumed open meetings of the African Methodist Episcopal

The African Methodist Episcopal Church, usually called the AME Church or AME, is a predominantly African American Methodist denomination. It adheres to Wesleyan-Arminian theology and has a connexional polity. The African Methodist Episcopal ...

and AME Zion #REDIRECT AME #REDIRECT AME

{{redirect category shell, {{R from other capitalisation{{R from ambiguous page ...

{{redirect category shell, {{R from other capitalisation{{R from ambiguous page ...

churches. They purchased dogs, guns, liquor, and better clothes—all previously banned—and ceased yielding the sidewalks to whites.

Despite the efforts of the state legislature to halt

manumission

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing enslaved people by their enslavers. Different approaches to manumission were developed, each specific to the time and place of a particular society. Historian Verene Shepherd states that t ...

s, Charleston had already had a large class of free people of color as well. At the onset of the war, the city had 3,785 free people of color, many of mixed race, making up about 18% of the city's black population and 8% of its total population. Many were educated and practiced skilled crafts;

they quickly became leaders of South Carolina's

Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

*Republican Party (Liberia)

* Republican Part ...

and its legislators. Men who had been free people of color before the war comprised 26% of those elected to state and federal office in South Carolina from 1868 to 1876.

By the late 1870s, industry was bringing the city and its inhabitants back to a renewed vitality; new jobs attracted new residents. As the city's commerce improved, residents worked to restore or create community institutions. In 1865, the

Avery Normal Institute was established by the

American Missionary Association