C4 carbon fixation on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

carbon fixation or the Hatch–Slack pathway is one of three known

carbon fixation or the Hatch–Slack pathway is one of three known

plants often possess a characteristic

plants often possess a characteristic

The first step in the NADP-ME type pathway is the conversion of pyruvate (Pyr) to

The first step in the NADP-ME type pathway is the conversion of pyruvate (Pyr) to

Here, the OAA produced by PEPC is transaminated by aspartate aminotransferase to aspartate (ASP) which is the metabolite diffusing to the bundle sheath. In the bundle sheath ASP is transaminated again to OAA and then undergoes a futile reduction and oxidative decarboxylation to release . The resulting Pyruvate is transaminated to alanine, diffusing to the mesophyll. Alanine is finally transaminated to pyruvate (PYR) which can be regenerated to PEP by PPDK in the mesophyll chloroplasts. This cycle bypasses the reaction of malate dehydrogenase in the mesophyll and therefore does not transfer reducing equivalents to the bundle sheath.

Here, the OAA produced by PEPC is transaminated by aspartate aminotransferase to aspartate (ASP) which is the metabolite diffusing to the bundle sheath. In the bundle sheath ASP is transaminated again to OAA and then undergoes a futile reduction and oxidative decarboxylation to release . The resulting Pyruvate is transaminated to alanine, diffusing to the mesophyll. Alanine is finally transaminated to pyruvate (PYR) which can be regenerated to PEP by PPDK in the mesophyll chloroplasts. This cycle bypasses the reaction of malate dehydrogenase in the mesophyll and therefore does not transfer reducing equivalents to the bundle sheath.

In this variant the OAA produced by aspartate aminotransferase in the bundle sheath is decarboxylated to PEP by PEPCK. The fate of PEP is still debated. The simplest explanation is that PEP would diffuse back to the mesophyll to serve as a substrate for PEPC. Because PEPCK uses only one ATP molecule, the regeneration of PEP through PEPCK would theoretically increase photosynthetic efficiency of this subtype, however this has never been measured. An increase in relative expression of PEPCK has been observed under low light, and it has been proposed to play a role in facilitating balancing energy requirements between mesophyll and bundle sheath.

In this variant the OAA produced by aspartate aminotransferase in the bundle sheath is decarboxylated to PEP by PEPCK. The fate of PEP is still debated. The simplest explanation is that PEP would diffuse back to the mesophyll to serve as a substrate for PEPC. Because PEPCK uses only one ATP molecule, the regeneration of PEP through PEPCK would theoretically increase photosynthetic efficiency of this subtype, however this has never been measured. An increase in relative expression of PEPCK has been observed under low light, and it has been proposed to play a role in facilitating balancing energy requirements between mesophyll and bundle sheath.

Khan Academy, video lecture

{{Authority control Photosynthesis

photosynthetic

Photosynthesis is a process used by plants and other organisms to convert light energy into chemical energy that, through cellular respiration, can later be released to fuel the organism's activities. Some of this chemical energy is stored in c ...

processes of carbon fixation in plants. It owes the names to the 1960's discovery by Marshall Davidson Hatch and Charles Roger Slack that some plants, when supplied with 14, incorporate the 14C label into four-carbon molecules first.

fixation is an addition to the ancestral and more common carbon fixation. The main carboxylating enzyme in photosynthesis is called RuBisCO

Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase-oxygenase, commonly known by the abbreviations RuBisCo, rubisco, RuBPCase, or RuBPco, is an enzyme () involved in the first major step of carbon fixation, a process by which atmospheric carbon dioxide is con ...

, which catalyses two distinct reactions using either (carboxylation) or oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as wel ...

(oxygenation) as a substrate. The latter process, oxygenation, gives rise to the wasteful process of photorespiration

Photorespiration (also known as the oxidative photosynthetic carbon cycle or C2 cycle) refers to a process in plant metabolism where the enzyme RuBisCO oxygenates RuBP, wasting some of the energy produced by photosynthesis. The desired reaction ...

. photosynthesis reduces photorespiration by concentrating around RuBisCO. To ensure that RuBisCO works in an environment where there is a lot of carbon dioxide and very little oxygen, leaves generally differentiate two partially isolated compartments called mesophyll cells and bundle-sheath cells. is initially fixed in the mesophyll cells by the enzyme PEP carboxylase which reacts the three carbon phosphoenolpyruvate

Phosphoenolpyruvate (2-phosphoenolpyruvate, PEP) is the ester derived from the enol of pyruvate and phosphate. It exists as an anion. PEP is an important intermediate in biochemistry. It has the highest-energy phosphate bond found (−61.9 kJ/ ...

(PEP) with to form the four carbon oxaloacetic acid

Oxaloacetic acid (also known as oxalacetic acid or OAA) is a crystalline organic compound with the chemical formula HO2CC(O)CH2CO2H. Oxaloacetic acid, in the form of its conjugate base oxaloacetate, is a metabolic intermediate in many processes ...

(OAA). OAA can be chemically reduced to malate

Malic acid is an organic compound with the molecular formula . It is a dicarboxylic acid that is made by all living organisms, contributes to the sour taste of fruits, and is used as a food additive. Malic acid has two stereoisomeric forms (L ...

or transaminated to aspartate. These intermediates diffuse to the bundle sheath cells, where they are decarboxylated, creating a -rich environment around RuBisCO and thereby suppressing photorespiration. The resulting pyruvate (PYR), together with about half of the phosphoglycerate (PGA) produced by RuBisCO, diffuses back to the mesophyll. PGA is then chemically reduced and diffuses back to the bundle sheath to complete the reductive pentose phosphate cycle (RPP). This exchange of metabolites is essential for photosynthesis to work.

On one hand, these additional steps require more energy in the form of ATP to regenerate PEP. On the other hand, concentrating allows high rates of photosynthesis at higher temperatures. Higher concentration overcomes the reduction of gas solubility with temperature (Henry's law

In physical chemistry, Henry's law is a gas law that states that the amount of dissolved gas in a liquid is directly proportional to its partial pressure above the liquid. The proportionality factor is called Henry's law constant. It was formulat ...

). The concentrating mechanism also maintains high gradients of concentration across the stomatal pores. This means that plants have generally lower stomatal conductance Stomatal conductance, usually measured in mmol m−2 s−1 by a porometer, estimates the rate of gas exchange (i.e., carbon dioxide uptake) and transpiration (i.e., water loss as water vapor) through the leaf stomata as determined by the degree of ...

, reduced water losses and have generally higher water-use efficiency

Water-use efficiency (WUE) refers to the ratio of water used in plant metabolism to water lost by the plant through transpiration. Two types of water-use efficiency are referred to most frequently:

* photosynthetic water-use efficiency (also cal ...

. plants are also more efficient in using nitrogen, since PEP carboxylase is much cheaper to make than RuBisCO. However, since the pathway does not require extra energy for the regeneration of PEP, it is more efficient in conditions where photorespiration is limited, typically at low temperatures and in the shade.

Discovery

The first experiments indicating that some plants do not use carbon fixation but instead producemalate

Malic acid is an organic compound with the molecular formula . It is a dicarboxylic acid that is made by all living organisms, contributes to the sour taste of fruits, and is used as a food additive. Malic acid has two stereoisomeric forms (L ...

and aspartate in the first step of carbon fixation were done in the 1950s and early 1960s by Hugo Peter Kortschak and Yuri Karpilov Yuri may refer to:

People and fictional characters

Given name

*Yuri (Slavic name), the Slavic masculine form of the given name George, including a list of people with the given name Yuri, Yury, etc.

*Yuri (Japanese name), also Yūri, feminine Jap ...

. The pathway was elucidated by Marshall Davidson Hatch and Charles Roger Slack, in Australia, in 1966. While Hatch and Slack originally referred to the pathway as the "C4 dicarboxylic acid pathway", it is sometimes called the Hatch–Slack pathway.

Anatomy

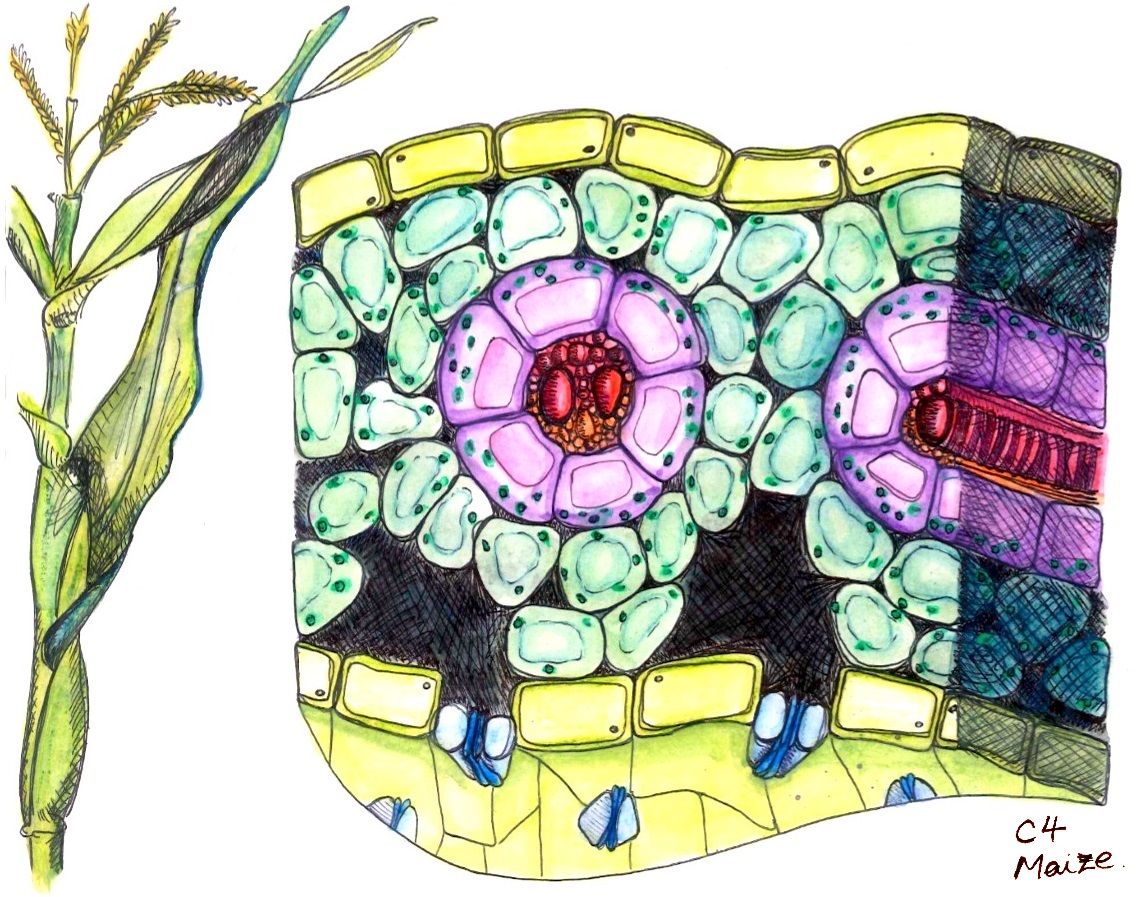

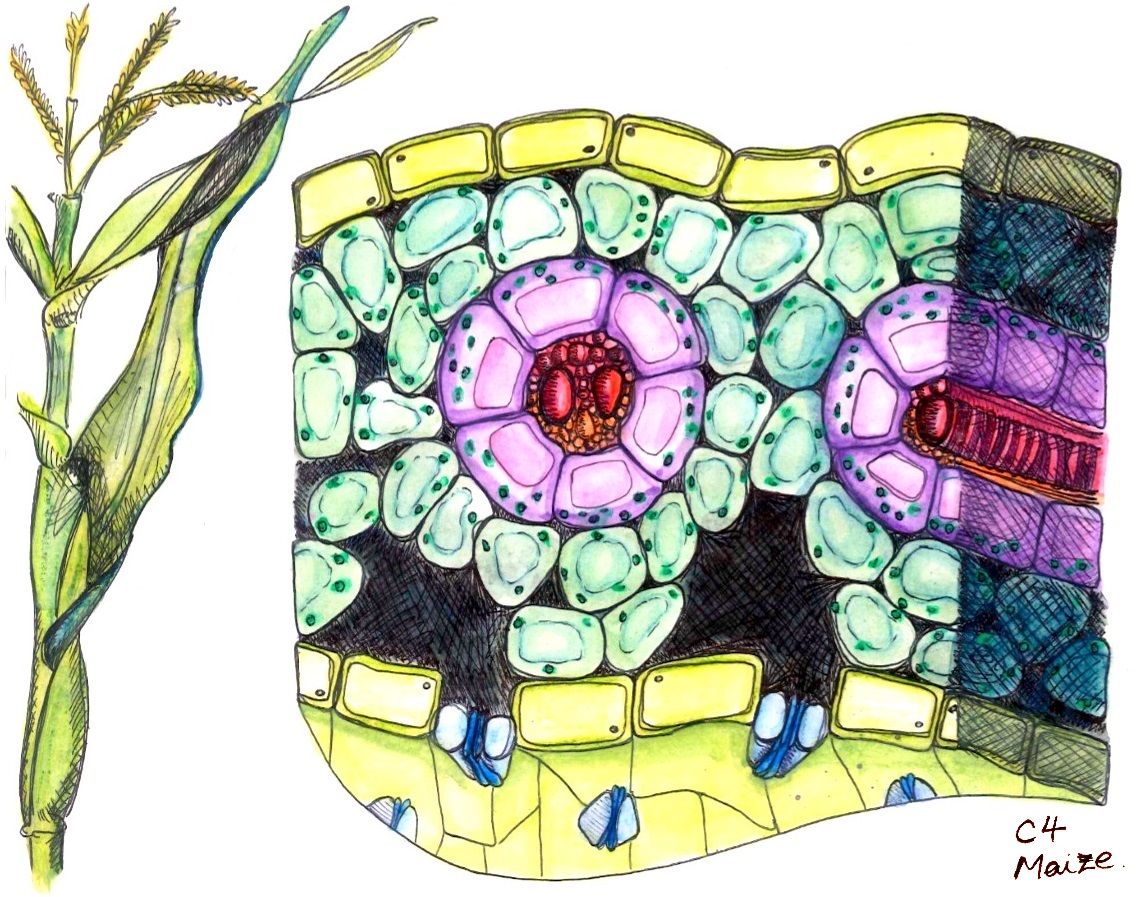

plants often possess a characteristic

plants often possess a characteristic leaf

A leaf ( : leaves) is any of the principal appendages of a vascular plant stem, usually borne laterally aboveground and specialized for photosynthesis. Leaves are collectively called foliage, as in "autumn foliage", while the leaves, ste ...

anatomy called ''kranz anatomy'', from the German word for wreath

A wreath () is an assortment of flowers, leaves, fruits, twigs, or various materials that is constructed to form a circle .

In English-speaking countries, wreaths are used typically as household ornaments, most commonly as an Advent and Chri ...

. Their vascular bundle

A vascular bundle is a part of the transport system in vascular plants. The transport itself happens in the stem, which exists in two forms: xylem and phloem. Both these tissues are present in a vascular bundle, which in addition will inclu ...

s are surrounded by two rings of cells; the inner ring, called bundle sheath cell

A vascular bundle is a part of the transport system in vascular plants. The transport itself happens in the stem, which exists in two forms: xylem and phloem. Both these tissues are present in a vascular bundle, which in addition will inclu ...

s, contains starch

Starch or amylum is a polymeric carbohydrate consisting of numerous glucose units joined by glycosidic bonds. This polysaccharide is produced by most green plants for energy storage. Worldwide, it is the most common carbohydrate in human diets ...

-rich chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant and algal cells. The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll captures the energy from sunlight, converts it, and stores it in ...

s lacking grana, which differ from those in mesophyll

A leaf ( : leaves) is any of the principal appendages of a vascular plant stem, usually borne laterally aboveground and specialized for photosynthesis. Leaves are collectively called foliage, as in "autumn foliage", while the leaves, s ...

cells present as the outer ring. Hence, the chloroplasts are called dimorphic. The primary function of kranz anatomy is to provide a site in which can be concentrated around RuBisCO, thereby avoiding photorespiration

Photorespiration (also known as the oxidative photosynthetic carbon cycle or C2 cycle) refers to a process in plant metabolism where the enzyme RuBisCO oxygenates RuBP, wasting some of the energy produced by photosynthesis. The desired reaction ...

. Mesophyll and bundle sheath cells are connected through numerous cytoplasmic sleeves called plasmodesmata

Plasmodesmata (singular: plasmodesma) are microscopic channels which traverse the cell walls of plant cells and some algal cells, enabling transport and communication between them. Plasmodesmata evolved independently in several lineages, and spec ...

whose permeability at leaf level is called bundle sheath conductance. A layer of suberin

Suberin, cutin and lignins are complex, higher plant epidermis and periderm cell-wall macromolecules, forming a protective barrier. Suberin, a complex polyester biopolymer, is lipophilic, and composed of long chain fatty acids called suberin aci ...

is often deposed at the level of the middle lamella

The middle lamella is a layer that cements together the primary cell walls of two adjoining plant cells. It is the first formed layer to be deposited at the time of cytokinesis

Cytokinesis () is the part of the cell division process during ...

(tangential interface between mesophyll and bundle sheath) in order to reduce the apoplastic diffusion of (called leakage). The carbon concentration mechanism in plants distinguishes their isotopic signature from other photosynthetic organisms.

Although most plants exhibit kranz anatomy, there are, however, a few species that operate a limited cycle without any distinct bundle sheath tissue. '' Suaeda aralocaspica'', ''Bienertia cycloptera'', ''Bienertia sinuspersici'' and ''Bienertia kavirense'' (all chenopods) are terrestrial plants that inhabit dry, salty depressions in the deserts of the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

. These plants have been shown to operate single-cell -concentrating mechanisms, which are unique among the known mechanisms. Although the cytology of both genera differs slightly, the basic principle is that fluid-filled vacuole

A vacuole () is a membrane-bound organelle which is present in plant and fungal cells and some protist, animal, and bacterial cells. Vacuoles are essentially enclosed compartments which are filled with water containing inorganic and organic mo ...

s are employed to divide the cell into two separate areas. Carboxylation enzymes in the cytosol

The cytosol, also known as cytoplasmic matrix or groundplasm, is one of the liquids found inside cells (intracellular fluid (ICF)). It is separated into compartments by membranes. For example, the mitochondrial matrix separates the mitochondri ...

are separated from decarboxylase

Carboxy-lyases, also known as decarboxylases, are carbon–carbon lyases that add or remove a carboxyl group from organic compounds. These enzymes catalyze the decarboxylation of amino acids, beta-keto acids and alpha-keto acids.

Classification a ...

enzymes and RuBisCO in the chloroplasts. A diffusive barrier is between the chloroplasts (which contain RuBisCO) and the cytosol. This enables a bundle-sheath-type area and a mesophyll-type area to be established within a single cell. Although this does allow a limited cycle to operate, it is relatively inefficient. Much leakage of from around RuBisCO occurs.

There is also evidence of inducible photosynthesis by non-kranz aquatic macrophyte ''Hydrilla verticillata

''Hydrilla'' (waterthyme) is a genus of aquatic plant, usually treated as containing just one species, ''Hydrilla verticillata'', though some botanists divide it into several species. It is native to the cool and warm waters of the Old World in ...

'' under warm conditions, although the mechanism by which leakage from around RuBisCO is minimised is currently uncertain.

Biochemistry

In plants, the first step in thelight-independent reaction

The Calvin cycle, light-independent reactions, bio synthetic phase, dark reactions, or photosynthetic carbon reduction (PCR) cycle of photosynthesis is a series of chemical reactions that convert carbon dioxide and hydrogen-carrier compounds into ...

s of photosynthesis is the fixation of by the enzyme RuBisCO

Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase-oxygenase, commonly known by the abbreviations RuBisCo, rubisco, RuBPCase, or RuBPco, is an enzyme () involved in the first major step of carbon fixation, a process by which atmospheric carbon dioxide is con ...

to form 3-phosphoglycerate. However, RuBisCo has a dual carboxylase and oxygenase

An oxygenase is any enzyme that oxidizes a substrate by transferring the oxygen from molecular oxygen O2 (as in air) to it. The oxygenases form a class of oxidoreductases; their EC number is EC 1.13 or EC 1.14.

Discoverers

Oxygenases were disco ...

activity. Oxygenation results in part of the substrate being oxidized

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or a ...

rather than carboxylated

Carboxylation is a chemical reaction in which a carboxylic acid is produced by treating a substrate with carbon dioxide. The opposite reaction is decarboxylation. In chemistry, the term carbonation is sometimes used synonymously with carboxylat ...

, resulting in loss of substrate and consumption of energy, in what is known as photorespiration

Photorespiration (also known as the oxidative photosynthetic carbon cycle or C2 cycle) refers to a process in plant metabolism where the enzyme RuBisCO oxygenates RuBP, wasting some of the energy produced by photosynthesis. The desired reaction ...

. Oxygenation and carboxylation are competitive

Competition is a rivalry where two or more parties strive for a common goal which cannot be shared: where one's gain is the other's loss (an example of which is a zero-sum game). Competition can arise between entities such as organisms, indivi ...

, meaning that the rate of the reactions depends on the relative concentration of oxygen and .

In order to reduce the rate of photorespiration

Photorespiration (also known as the oxidative photosynthetic carbon cycle or C2 cycle) refers to a process in plant metabolism where the enzyme RuBisCO oxygenates RuBP, wasting some of the energy produced by photosynthesis. The desired reaction ...

, plants increase the concentration of around RuBisCO. To do so two partially isolated compartments differentiate within leaves, the mesophyll

A leaf ( : leaves) is any of the principal appendages of a vascular plant stem, usually borne laterally aboveground and specialized for photosynthesis. Leaves are collectively called foliage, as in "autumn foliage", while the leaves, s ...

and the bundle sheath

A vascular bundle is a part of the transport system in vascular plants. The transport itself happens in the stem, which exists in two forms: xylem and phloem. Both these tissues are present in a vascular bundle, which in addition will includ ...

. Instead of direct fixation by RuBisCO, is initially incorporated into a four-carbon organic acid (either malate

Malic acid is an organic compound with the molecular formula . It is a dicarboxylic acid that is made by all living organisms, contributes to the sour taste of fruits, and is used as a food additive. Malic acid has two stereoisomeric forms (L ...

or aspartate) in the mesophyll. The organic acids then diffuse through plasmodesmata

Plasmodesmata (singular: plasmodesma) are microscopic channels which traverse the cell walls of plant cells and some algal cells, enabling transport and communication between them. Plasmodesmata evolved independently in several lineages, and spec ...

into the bundle sheath cells. There, they are decarboxylated creating a -rich environment. The chloroplasts of the bundle sheath cells convert this into carbohydrates by the conventional pathway.

There is large variability in the biochemical features of C4 assimilation, and it is generally grouped in three subtypes, differentiated by the main enzyme used for decarboxylation ( NADP-malic enzyme

Malate dehydrogenase (oxaloacetate-decarboxylating) (NADP+) () or NADP-malic enzyme (NADP-ME) is an enzyme that catalyzes the chemical reaction in the presence of a bivalent metal ion:

:(S)-malate + NADP+ \rightleftharpoons pyruvate + CO2 + NAD ...

, NADP-ME; NAD-malic enzyme

Malate dehydrogenase (decarboxylating) () or NAD-malic enzyme (NAD-ME) is an enzyme that catalyzes the chemical reaction

:(S)-malate + NAD+ \rightleftharpoons pyruvate + CO2 + NADH

Thus, the two substrates of this enzyme are (S)-malate and NA ...

, NAD-ME; and PEP carboxykinase

Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (, PEPCK) is an enzyme in the lyase family used in the metabolic pathway of gluconeogenesis. It converts oxaloacetate into phosphoenolpyruvate and carbon dioxide.

It is found in two forms, cytosolic and mitoch ...

, PEPCK). Since PEPCK is often recruited atop NADP-ME or NAD-ME it was proposed to classify the biochemical variability in two subtypes. For instance, maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. Th ...

and sugarcane

Sugarcane or sugar cane is a species of (often hybrid) tall, Perennial plant, perennial grass (in the genus ''Saccharum'', tribe Andropogoneae) that is used for sugar Sugar industry, production. The plants are 2–6 m (6–20 ft) tall with ...

use a combination of NADP-ME and PEPCK, millet

Millets () are a highly varied group of small-seeded grasses, widely grown around the world as cereal crops or grains for fodder and human food. Most species generally referred to as millets belong to the tribe Paniceae, but some millets al ...

uses preferentially NAD-ME and ''Megathyrsus maximus

''Megathyrsus maximus'', known as Guinea grass and green panic grass, is a large perennial bunch grass that is native to Africa and Yemen. It has been introduced in the tropics around the world. It has previously been called ''Urochloa maxima'' ...

'', uses preferentially PEPCK.

NADP-ME

phosphoenolpyruvate

Phosphoenolpyruvate (2-phosphoenolpyruvate, PEP) is the ester derived from the enol of pyruvate and phosphate. It exists as an anion. PEP is an important intermediate in biochemistry. It has the highest-energy phosphate bond found (−61.9 kJ/ ...

(PEP), by the enzyme Pyruvate phosphate dikinase (PPDK). This reaction requires inorganic phosphate and ATP plus pyruvate, producing PEP, AMP #REDIRECT Amp

{{Redirect category shell, {{R from other capitalisation{{R from ambiguous page ...

, and inorganic pyrophosphate

In chemistry, pyrophosphates are phosphorus oxyanions that contain two phosphorus atoms in a P–O–P linkage. A number of pyrophosphate salts exist, such as disodium pyrophosphate (Na2H2P2O7) and tetrasodium pyrophosphate (Na4P2O7), among othe ...

(PPi). The next step is the carboxylation

Carboxylation is a chemical reaction in which a carboxylic acid is produced by treating a substrate with carbon dioxide. The opposite reaction is decarboxylation. In chemistry, the term carbonation is sometimes used synonymously with carboxylatio ...

of PEP by the PEP carboxylase enzyme (PEPC) producing oxaloacetate

Oxaloacetic acid (also known as oxalacetic acid or OAA) is a crystalline organic compound with the chemical formula HO2CC(O)CH2CO2H. Oxaloacetic acid, in the form of its conjugate base oxaloacetate, is a metabolic intermediate in many processes ...

. Both of these steps occur in the mesophyll cells:

:pyruvate + Pi + ATP → PEP + AMP + PPi

:PEP + → oxaloacetate

PEPC has a low KM for — and, hence, high affinity, and is not confounded by O2 thus it will work even at low concentrations of .

The product is usually converted to malate

Malic acid is an organic compound with the molecular formula . It is a dicarboxylic acid that is made by all living organisms, contributes to the sour taste of fruits, and is used as a food additive. Malic acid has two stereoisomeric forms (L ...

(M), which diffuses to the bundle-sheath cells surrounding a nearby vein

Veins are blood vessels in humans and most other animals that carry blood towards the heart. Most veins carry deoxygenated blood from the tissues back to the heart; exceptions are the pulmonary and umbilical veins, both of which carry oxygenated b ...

. Here, it is decarboxylated by the NADP-malic enzyme

Malate dehydrogenase (oxaloacetate-decarboxylating) (NADP+) () or NADP-malic enzyme (NADP-ME) is an enzyme that catalyzes the chemical reaction in the presence of a bivalent metal ion:

:(S)-malate + NADP+ \rightleftharpoons pyruvate + CO2 + NAD ...

(NADP-ME) to produce and pyruvate. The is fixed by RuBisCo to produce phosphoglycerate (PGA) while the pyruvate is transported back to the mesophyll

A leaf ( : leaves) is any of the principal appendages of a vascular plant stem, usually borne laterally aboveground and specialized for photosynthesis. Leaves are collectively called foliage, as in "autumn foliage", while the leaves, s ...

cell, together with about half of the phosphoglycerate (PGA). This PGA is chemically reduced in the mesophyll and diffuses back to the bundle sheath where it enters the conversion phase of the Calvin cycle

The Calvin cycle, light-independent reactions, bio synthetic phase, dark reactions, or photosynthetic carbon reduction (PCR) cycle of photosynthesis is a series of chemical reactions that convert carbon dioxide and hydrogen-carrier compounds into ...

. For each molecule exported to the bundle sheath the malate shuttle transfers two electrons, and therefore reduces the demand of reducing power in the bundle sheath.

NAD-ME

PEPCK

Metabolite exchange

While in photosynthesis each chloroplast is capable of completing light reactions and dark reactions, chloroplasts differentiate in two populations, contained in the mesophyll and bundle sheath cells. The division of the photosynthetic work between two types of chloroplasts results inevitably in a prolific exchange of intermediates between them. The fluxes are large and can be up to ten times the rate of gross assimilation. The type of metabolite exchanged and the overall rate will depend on the subtype. To reduce product inhibition of photosynthetic enzymes (for instance PECP) concentration gradients need to be as low as possible. This requires increasing the conductance of metabolites between mesophyll and bundle sheath, but this would also increase the retrodiffusion of out of the bundle sheath, resulting in an inherent and inevitable trade off in the optimisation of the concentrating mechanism.Light harvesting and light reactions

To meet the NADPH and ATP demands in the mesophyll and bundle sheath, light needs to be harvested and shared between two distinct electron transfer chains. ATP may be produced in the bundle sheath mainly through cyclic electron flow around Photosystem I, or in the M mainly through linear electron flow depending on the light available in the bundle sheath or in the mesophyll. The relative requirement of ATP and NADPH in each type of cells will depend on the photosynthetic subtype. The apportioning of excitation energy between the two cell types will influence the availability of ATP and NADPH in the mesohyll and bundle sheath. For instance, green light is not strongly adsorbed by mesophyll cells and can preferentially excite bundle sheath cells, or ''vice versa'' for blue light. Because bundle sheaths are surrounded by mesophyll, light harvesting in the mesophyll will reduce the light available to reach BS cells. Also, the bundle sheath size limits the amount of light that can be harvested.Efficiency

Different formulations of efficiency are possible depending on which outputs and inputs are considered. For instance, average quantum efficiency is the ratio between gross assimilation and either absorbed or incident light intensity. Large variability of measured quantum efficiency is reported in the literature between plants grown in different conditions and classified in different subtypes but the underpinnings are still unclear. One of the components of quantum efficiency is the efficiency of dark reactions, biochemical efficiency, which is generally expressed in reciprocal terms as ATP cost of gross assimilation (ATP/GA). In photosynthesis ATP/GA depends mainly on and O2 concentration at the carboxylating sites of RuBisCO. When concentration is high and O2 concentration is low photorespiration is suppressed and assimilation is fast and efficient, with ATP/GA approaching the theoretical minimum of 3. In photosynthesis concentration at the RuBisCO carboxylating sites is mainly the result of the operation of the concentrating mechanisms, which cost circa an additional 2 ATP/GA but makes efficiency relatively insensitive of external concentration in a broad range of conditions. Biochemical efficiency depends mainly on the speed of delivery to the bundle sheath, and will generally decrease under low light when PEP carboxylation rate decreases, lowering the ratio of /O2 concentration at the carboxylating sites of RuBisCO. The key parameter defining how much efficiency will decrease under low light is bundle sheath conductance. Plants with higher bundle sheath conductance will be facilitated in the exchange of metabolites between the mesophyll and bundle sheath and will be capable of high rates of assimilation under high light. However, they will also have high rates of retrodiffusion from the bundle sheath (called leakage) which will increase photorespiration and decrease biochemical efficiency under dim light. This represents an inherent and inevitable trade off in the operation of photosynthesis. plants have an outstanding capacity to attune bundle sheath conductance. Interestingly, bundle sheath conductance is downregulated in plants grown under low light and in plants grown under high light subsequently transferred to low light as it occurs in crop canopies where older leaves are shaded by new growth.Evolution and advantages

plants have a competitive advantage over plants possessing the more common carbon fixation pathway under conditions ofdrought

A drought is defined as drier than normal conditions.Douville, H., K. Raghavan, J. Renwick, R.P. Allan, P.A. Arias, M. Barlow, R. Cerezo-Mota, A. Cherchi, T.Y. Gan, J. Gergis, D. Jiang, A. Khan, W. Pokam Mba, D. Rosenfeld, J. Tierney, an ...

, high temperature

Temperature is a physical quantity that expresses quantitatively the perceptions of hotness and coldness. Temperature is measured with a thermometer.

Thermometers are calibrated in various temperature scales that historically have relied o ...

s, and nitrogen

Nitrogen is the chemical element with the symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a nonmetal and the lightest member of group 15 of the periodic table, often called the pnictogens. It is a common element in the universe, estimated at se ...

or limitation. When grown in the same environment, at 30 °C, grasses lose approximately 833 molecules of water per molecule that is fixed, whereas grasses lose only 277. This increased water use efficiency

Water-use efficiency (WUE) refers to the ratio of water used in plant metabolism to water lost by the plant through transpiration. Two types of water-use efficiency are referred to most frequently:

* photosynthetic water-use efficiency (also cal ...

of grasses means that soil moisture is conserved, allowing them to grow for longer in arid environments.

carbon fixation has evolved

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

in up to 61 independent occasions in 19 different families of plants, making it a prime example of convergent evolution

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last com ...

. This convergence may have been facilitated by the fact that many potential evolutionary pathways to a phenotype

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology or physical form and structure, its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological proper ...

exist, many of which involve initial evolutionary steps not directly related to photosynthesis. plants arose around during the Oligocene

The Oligocene ( ) is a geologic epoch of the Paleogene Period and extends from about 33.9 million to 23 million years before the present ( to ). As with other older geologic periods, the rock beds that define the epoch are well identified but the ...

(precisely when is difficult to determine) and did not become ecologically significant until around , in the Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and means "less recen ...

. metabolism in grasses originated when their habitat migrated from the shady forest undercanopy to more open environments, where the high sunlight gave it an advantage over the pathway. Drought was not necessary for its innovation; rather, the increased parsimony in water use was a byproduct of the pathway and allowed plants to more readily colonize arid environments.

Today, plants represent about 5% of Earth's plant biomass and 3% of its known plant species. Despite this scarcity, they account for about 23% of terrestrial carbon fixation. Increasing the proportion of plants on earth could assist biosequestration

Biosequestration or biological sequestration is the capture and storage of the atmospheric greenhouse gas carbon dioxide by continual or enhanced biological processes.

This form of carbon sequestration occurs through increased rates of photosyn ...

of and represent an important climate change

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to E ...

avoidance strategy. Present-day plants are concentrated in the tropics and subtropics (below latitudes of 45 degrees) where the high air temperature increases rates of photorespiration in plants.

Plants that use carbon fixation

About 8,100 plant species use carbon fixation, which represents about 3% of all terrestrial species of plants. All these 8,100 species areangiosperm

Flowering plants are plants that bear flowers and fruits, and form the clade Angiospermae (), commonly called angiosperms. The term "angiosperm" is derived from the Greek words ('container, vessel') and ('seed'), and refers to those plants th ...

s. carbon fixation is more common in monocot

Monocotyledons (), commonly referred to as monocots, (Lilianae ''sensu'' Chase & Reveal) are grass and grass-like flowering plants (angiosperms), the seeds of which typically contain only one embryonic leaf, or cotyledon. They constitute one of ...

s compared with dicot

The dicotyledons, also known as dicots (or, more rarely, dicotyls), are one of the two groups into which all the flowering plants (angiosperms) were formerly divided. The name refers to one of the typical characteristics of the group: namely, t ...

s, with 40% of monocots using the pathway, compared with only 4.5% of dicots. Despite this, only three families

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Ideal ...

of monocots use carbon fixation compared to 15 dicot families. Of the monocot clades containing plants, the grass (Poaceae

Poaceae () or Gramineae () is a large and nearly ubiquitous family of monocotyledonous flowering plants commonly known as grasses. It includes the cereal grasses, bamboos and the grasses of natural grassland and species cultivated in lawns an ...

) species use the photosynthetic pathway most. 46% of grasses are and together account for 61% of species. has arisen independently in the grass family some twenty or more times, in various subfamilies, tribes, and genera, including the Andropogoneae

The Andropogoneae, sometimes called the sorghum tribe, are a large tribe of grasses (family Poaceae) with roughly 1,200 species in 90 genera, mainly distributed in tropical and subtropical areas. They include such important crops as maize (corn), ...

tribe which contains the food crops maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. Th ...

, sugar cane

Sugarcane or sugar cane is a species of (often hybrid) tall, perennial grass (in the genus ''Saccharum'', tribe Andropogoneae) that is used for sugar production. The plants are 2–6 m (6–20 ft) tall with stout, jointed, fibrous stalks t ...

, and sorghum

''Sorghum'' () is a genus of about 25 species of flowering plants in the grass family (Poaceae). Some of these species are grown as cereals for human consumption and some in pastures for animals. One species is grown for grain, while many othe ...

. Various kinds of millet

Millets () are a highly varied group of small-seeded grasses, widely grown around the world as cereal crops or grains for fodder and human food. Most species generally referred to as millets belong to the tribe Paniceae, but some millets al ...

are also . Of the dicot clades containing species, the order Caryophyllales

Caryophyllales ( ) is a diverse and heterogeneous order of flowering plants that includes the cacti, carnations, amaranths, ice plants, beets, and many carnivorous plants. Many members are succulent, having fleshy stems or leaves. The betalai ...

contains the most species. Of the families in the Caryophyllales, the Chenopodiaceae

Amaranthaceae is a family of flowering plants commonly known as the amaranth family, in reference to its type genus '' Amaranthus''. It includes the former goosefoot family Chenopodiaceae and contains about 165 genera and 2,040 species, making i ...

use carbon fixation the most, with 550 out of 1,400 species using it. About 250 of the 1,000 species of the related Amaranthaceae

Amaranthaceae is a family of flowering plants commonly known as the amaranth family, in reference to its type genus ''Amaranthus''. It includes the former goosefoot family Chenopodiaceae and contains about 165 genera and 2,040 species, making it ...

also use .

Members of the sedge family Cyperaceae

The Cyperaceae are a family of graminoid (grass-like), monocotyledonous flowering plants known as sedges. The family is large, with some 5,500 known species described in about 90 genera, the largest being the "true sedges" genus ''Carex'' w ...

, and members of numerous families of eudicots – including Asteraceae

The family Asteraceae, alternatively Compositae, consists of over 32,000 known species of flowering plants in over 1,900 genera within the order Asterales. Commonly referred to as the aster, daisy, composite, or sunflower family, Compositae w ...

(the daisy family), Brassicaceae

Brassicaceae () or (the older) Cruciferae () is a medium-sized and economically important family of flowering plants commonly known as the mustards, the crucifers, or the cabbage family. Most are herbaceous plants, while some are shrubs. The leav ...

(the cabbage family), and Euphorbiaceae

Euphorbiaceae, the spurge family, is a large family of flowering plants. In English, they are also commonly called euphorbias, which is also the name of a genus in the family. Most spurges, such as ''Euphorbia paralias'', are herbs, but some, e ...

(the spurge family) – also use .

There are very few trees which use . Only a handful are known: ''Paulownia

''Paulownia'' ( ) is a genus of seven to 17 species of hardwood tree (depending on taxonomic authority) in the family Paulowniaceae, the order Lamiales. They are present in much of China, south to northern Laos and Vietnam and are long cultivat ...

'', seven Hawaiian ''Euphorbia

''Euphorbia'' is a very large and diverse genus of flowering plants, commonly called spurge, in the family Euphorbiaceae. "Euphorbia" is sometimes used in ordinary English to collectively refer to all members of Euphorbiaceae (in deference to t ...

'' species and a few desert shrubs that reach the size and shape of trees with age.

Converting plants to

Given the advantages of , a group of scientists from institutions around the world are working on the Rice Project to produce a strain ofrice

Rice is the seed of the grass species ''Oryza sativa'' (Asian rice) or less commonly ''Oryza glaberrima

''Oryza glaberrima'', commonly known as African rice, is one of the two domesticated rice species. It was first domesticated and grown i ...

, naturally a plant, that uses the pathway by studying the plants maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. Th ...

and ''Brachypodium

''Brachypodium'' is a genus of plants in the grass family, widespread across much of Africa, Eurasia, and Latin America. The genus is classified in its own tribe Brachypodieae.

Flimsy upright stems form tussocks. Flowers appear in compact spi ...

''. As rice is the world's most important human food—it is the staple food for more than half the planet—having rice that is more efficient at converting sunlight into grain could have significant global benefits towards improving food security

Food security speaks to the availability of food in a country (or geography) and the ability of individuals within that country (geography) to access, afford, and source adequate foodstuffs. According to the United Nations' Committee on World F ...

. The team claim rice could produce up to 50% more grain—and be able to do it with less water and nutrients.

The researchers have already identified genes needed for photosynthesis in rice and are now looking towards developing a prototype rice plant. In 2012, the Government of the United Kingdom

ga, Rialtas a Shoilse gd, Riaghaltas a Mhòrachd

, image = HM Government logo.svg

, image_size = 220px

, image2 = Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom (HM Government).svg

, image_size2 = 180px

, caption = Royal coat of arms of t ...

along with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation provided US$14 million over three years towards the Rice Project at the International Rice Research Institute

The International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) is an international agricultural research and training organization with its headquarters in Los Baños, Laguna, in the Philippines, and offices in seventeen countries. IRRI is known for its wor ...

. In 2019, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation granted another US$15 million to the Oxford-University-led C4 Rice Project. The goal of the 5-year project is to have experimental field plots up and running in Taiwan by 2024.

See also

* C2 photosynthesis *CAM photosynthesis

Crassulacean acid metabolism, also known as CAM photosynthesis, is a carbon fixation pathway that evolved in some plants as an adaptation to arid conditions that allows a plant to photosynthesize during the day, but only exchange gases at night. ...

* photosynthesis

References

External links

Khan Academy, video lecture

{{Authority control Photosynthesis