Buckingham Palace on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Buckingham Palace () is a

Buckingham Palace () is a

Possibly the first house erected within the site was that of Sir William Blake, around 1624. The next owner was Lord Goring, who from 1633 extended Blake's house, which came to be known as Goring House, and developed much of today's garden, then known as Goring Great Garden.Harris, p. 21. He did not, however, obtain the freehold interest in the mulberry garden. Unbeknown to Goring, in 1640 the document "failed to pass the Great Seal before

Possibly the first house erected within the site was that of Sir William Blake, around 1624. The next owner was Lord Goring, who from 1633 extended Blake's house, which came to be known as Goring House, and developed much of today's garden, then known as Goring Great Garden.Harris, p. 21. He did not, however, obtain the freehold interest in the mulberry garden. Unbeknown to Goring, in 1640 the document "failed to pass the Great Seal before

Buckingham Palace became the principal royal residence in 1837, on the accession of Queen Victoria, who was the first monarch to reside there; her predecessor William IV had died before its completion. While the state rooms were a riot of gilt and colour, the necessities of the new palace were somewhat less luxurious. It was reported the chimneys smoked so much that the fires had to be allowed to die down, and consequently the palace was often cold.Woodham-Smith, p. 249. Ventilation was so bad that the interior smelled, and when it was decided to install gas lamps, there was a serious worry about the build-up of gas on the lower floors. It was also said that the staff were lax and lazy and the palace was dirty. Following the Queen's marriage in 1840, her husband, Prince Albert, concerned himself with a reorganisation of the

Buckingham Palace became the principal royal residence in 1837, on the accession of Queen Victoria, who was the first monarch to reside there; her predecessor William IV had died before its completion. While the state rooms were a riot of gilt and colour, the necessities of the new palace were somewhat less luxurious. It was reported the chimneys smoked so much that the fires had to be allowed to die down, and consequently the palace was often cold.Woodham-Smith, p. 249. Ventilation was so bad that the interior smelled, and when it was decided to install gas lamps, there was a serious worry about the build-up of gas on the lower floors. It was also said that the staff were lax and lazy and the palace was dirty. Following the Queen's marriage in 1840, her husband, Prince Albert, concerned himself with a reorganisation of the

Many of the palace's contents are part of the Royal Collection, held in trust by

Many of the palace's contents are part of the Royal Collection, held in trust by

The front of the palace measures across, by deep, by high and contains over of floorspace. There are 775 rooms, including 188 staff bedrooms, 92 offices, 78 bathrooms, 52 principal bedrooms and 19 state rooms. It also has a

The front of the palace measures across, by deep, by high and contains over of floorspace. There are 775 rooms, including 188 staff bedrooms, 92 offices, 78 bathrooms, 52 principal bedrooms and 19 state rooms. It also has a

The principal rooms are contained on the first-floor '' piano nobile'' behind the west-facing garden façade at the rear of the palace. The centre of this ornate suite of state rooms is the Music Room, its large bow the dominant feature of the façade. Flanking the Music Room are the Blue and the White Drawing Rooms. At the centre of the suite, serving as a corridor to link the state rooms, is the Picture Gallery, which is top-lit and long.Harris, p. 41. The Gallery is hung with numerous works including some by Rembrandt,

The principal rooms are contained on the first-floor '' piano nobile'' behind the west-facing garden façade at the rear of the palace. The centre of this ornate suite of state rooms is the Music Room, its large bow the dominant feature of the façade. Flanking the Music Room are the Blue and the White Drawing Rooms. At the centre of the suite, serving as a corridor to link the state rooms, is the Picture Gallery, which is top-lit and long.Harris, p. 41. The Gallery is hung with numerous works including some by Rembrandt,

Directly underneath the state apartments are the less grand semi-state apartments. Opening from the Marble Hall, these rooms are used for less formal entertaining, such as luncheon parties and private

Directly underneath the state apartments are the less grand semi-state apartments. Opening from the Marble Hall, these rooms are used for less formal entertaining, such as luncheon parties and private

State banquets also take place in the Ballroom; these formal dinners are held on the first evening of a state visit by a foreign head of state. On these occasions, for up to 170 guests in formal "white tie and decorations", including tiaras, the dining table is laid with the Grand Service, a collection of silver-gilt plate made in 1811 for the Prince of Wales, later George IV. The largest and most formal reception at Buckingham Palace takes place every November when the King entertains members of the

State banquets also take place in the Ballroom; these formal dinners are held on the first evening of a state visit by a foreign head of state. On these occasions, for up to 170 guests in formal "white tie and decorations", including tiaras, the dining table is laid with the Grand Service, a collection of silver-gilt plate made in 1811 for the Prince of Wales, later George IV. The largest and most formal reception at Buckingham Palace takes place every November when the King entertains members of the

The boy Jones

, '' All the Year Round'', pp. 234–37. At least 12 people have managed to gain unauthorised entry into the palace or its grounds since 1914, including Michael Fagan, who broke into the palace twice in 1982 and entered Queen Elizabeth II's bedroom on the second occasion. At the time, news media reported that he had a long conversation with her while she waited for security officers to arrive, but in a 2012 interview with ''

Buckingham Palace

at the Royal Family website

Account of Buckingham Palace, with prints of Arlington House and Buckingham House

from ''Old and New London'' (1878)

Account of the acquisition of the Manor of Ebury

from ''Survey of London'' (1977)

The State Rooms, Buckingham Palace

at the

Buckingham Palace () is a

Buckingham Palace () is a London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

royal residence

A residence is a place (normally a building) used as a home or dwelling, where people reside.

Residence may more specifically refer to:

* Domicile (law), a legal term for residence

* Habitual residence, a civil law term dealing with the status ...

and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and royal hospitality. It has been a focal point for the British people

British people or Britons, also known colloquially as Brits, are the citizens of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the British Overseas Territories, and the Crown dependencies.: British nationality law governs mo ...

at times of national rejoicing and mourning.

Originally known as ''Buckingham House'', the building at the core of today's palace was a large townhouse

A townhouse, townhome, town house, or town home, is a type of terraced housing. A modern townhouse is often one with a small footprint on multiple floors. In a different British usage, the term originally referred to any type of city residence ...

built for the Duke of Buckingham

Duke of Buckingham held with Duke of Chandos, referring to Buckingham, is a title that has been created several times in the peerages of England, Great Britain, and the United Kingdom. There have also been earls and marquesses of Buckingham.

...

in 1703 on a site that had been in private ownership for at least 150 years. It was acquired by King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

in 1761 as a private residence for Queen Charlotte

Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (Sophia Charlotte; 19 May 1744 – 17 November 1818) was Queen of Great Britain and of Ireland as the wife of King George III from their marriage on 8 September 1761 until the union of the two kingdoms ...

and became known as The Queen's House. During the 19th century it was enlarged by architects John Nash and Edward Blore, who constructed three wings around a central courtyard. Buckingham Palace became the London residence of the British monarch on the accession of Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previo ...

in 1837.

The last major structural additions were made in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including the East Front, which contains the well-known balcony on which the royal family traditionally appears to greet crowds. A German bomb destroyed the palace chapel during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

; the Queen's Gallery

The Queen's Gallery is the main public art gallery of Buckingham Palace, home of the British monarch, in London. It exhibits works of art from the Royal Collection (the bulk of which works have since its opening been regularly displayed, s ...

was built on the site and opened to the public in 1962 to exhibit works of art from the Royal Collection.

The original early-19th-century interior designs, many of which survive, include widespread use of brightly coloured scagliola

Scagliola (from the Italian ''scaglia'', meaning "chips") is a type of fine plaster used in architecture and sculpture. The same term identifies the technique for producing columns, sculptures, and other architectural elements that resemble inla ...

and blue and pink lapis

Lapis lazuli (; ), or lapis for short, is a deep-blue metamorphic rock used as a semi-precious stone that has been prized since antiquity for its intense color.

As early as the 7th millennium BC, lapis lazuli was mined in the Sar-i Sang mines ...

, on the advice of Sir Charles Long. King Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910.

The second child and eldest son of Queen Victoria a ...

oversaw a partial redecoration in a Belle Époque cream and gold colour scheme. Many smaller reception rooms are furnished in the Chinese regency

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

style with furniture and fittings brought from the Royal Pavilion

The Royal Pavilion, and surrounding gardens, also known as the Brighton Pavilion, is a Grade I listed former royal residence located in Brighton, England. Beginning in 1787, it was built in three stages as a seaside retreat for George, Princ ...

at Brighton and from Carlton House

Carlton House was a mansion in Westminster, best known as the town residence of King George IV. It faced the south side of Pall Mall, and its gardens abutted St James's Park in the St James's district of London. The location of the house, no ...

. The palace has 775 rooms, and the garden is the largest private garden in London. The state rooms, used for official and state entertaining, are open to the public each year for most of August and September and on some days in winter and spring.

History

Pre-1624

In theMiddle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

, the site of the future palace formed part of the Manor of Ebury (also called Eia Eia or EIA may refer to:

Medicine

* Enzyme immunoassay

* Equine infectious anemia

* Exercise-induced anaphylaxis

* Exercise-induced asthma

* External iliac artery

Transport

* Edmonton International Airport, in Alberta, Canada

* Erbil Internation ...

). The marshy ground was watered by the river Tyburn

Tyburn was a manor (estate) in the county of Middlesex, one of two which were served by the parish of Marylebone.

The parish, probably therefore also the manor, was bounded by Roman roads to the west (modern Edgware Road) and south (modern O ...

, which still flows below the courtyard and south wing of the palace. Where the river was fordable (at Cow Ford), the village of Eye Cross grew. Ownership of the site changed hands many times; owners included Edward the Confessor and Edith of Wessex

Edith of Wessex ( 1025 – 18 December 1075) was Queen of England from her marriage to Edward the Confessor in 1045 until Edward died in 1066. Unlike most English queens in the 10th and 11th centuries, she was crowned. The principal source on h ...

in late Saxon times, and, after the Norman Conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Con ...

, William the Conqueror

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first House of Normandy, Norman List of English monarchs#House of Norman ...

. William gave the site to Geoffrey de Mandeville, who bequeathed it to the monks of Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the Unite ...

.

In 1531, Henry VIII acquired the Hospital of St James, which became St James's Palace, from Eton College

Eton College () is a public school in Eton, Berkshire, England. It was founded in 1440 by Henry VI under the name ''Kynge's College of Our Ladye of Eton besyde Windesore'',Nevill, p. 3 ff. intended as a sister institution to King's College, C ...

, and in 1536 he took the Manor of Ebury from Westminster Abbey. These transfers brought the site of Buckingham Palace back into royal hands for the first time since William the Conqueror had given it away almost 500 years earlier. Various owners leased it from royal landlords, and the freehold

Freehold may refer to:

In real estate

*Freehold (law), the tenure of property in fee simple

* Customary freehold, a form of feudal tenure of land in England

* Parson's freehold, where a Church of England rector or vicar of holds title to benefice ...

was the subject of frenzied speculation during the 17th century. By then, the old village of Eye Cross had long since fallen into decay, and the area was mostly wasteland. Needing money, James VI and I

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until ...

sold off part of the Crown freehold but retained part of the site on which he established a mulberry garden for the production of silk. (This is at the north-west corner of today's palace.) Clement Walker in ''Anarchia Anglicana'' (1649) refers to "new-erected sodoms and spintries at the Mulberry Garden at S. James's"; this suggests it may have been a place of debauchery. Eventually, in the late 17th century, the freehold was inherited from the property tycoon Sir Hugh Audley by the great heiress Mary Davies.

First houses on the site (1624–1761)

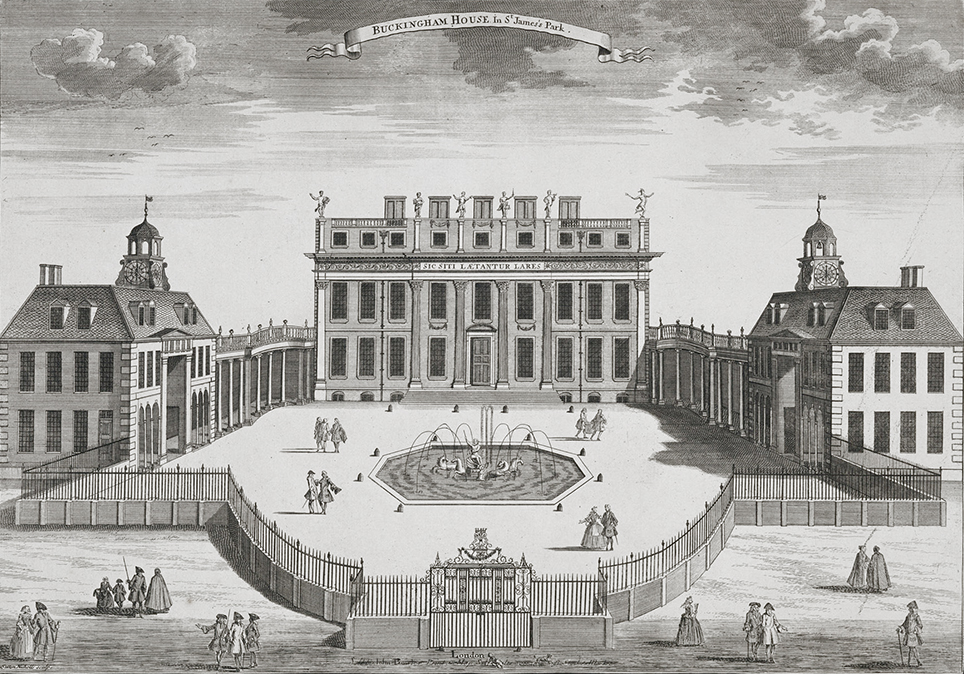

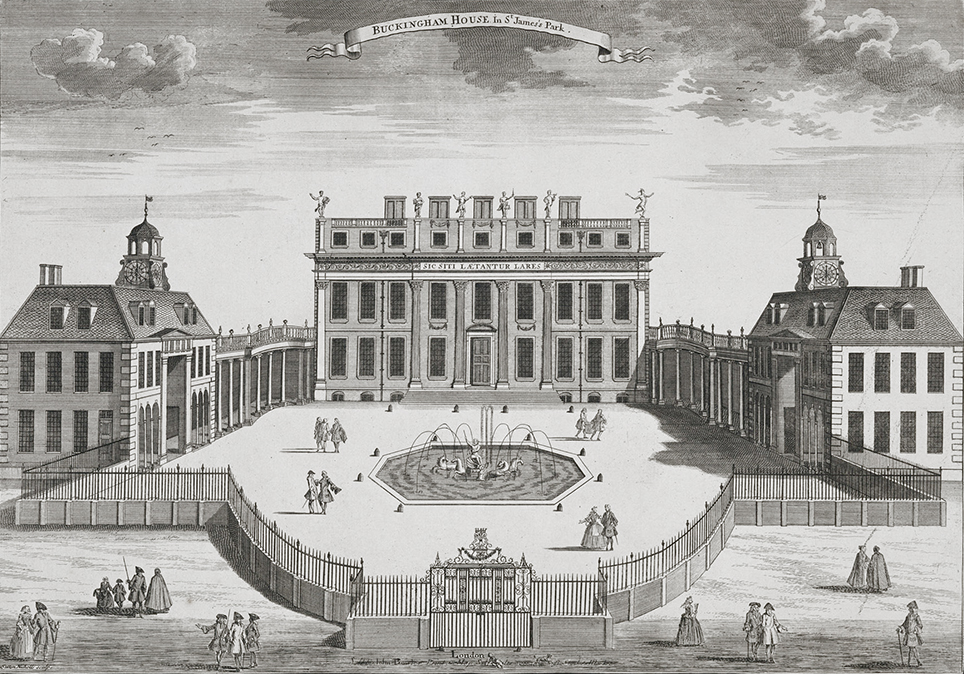

Possibly the first house erected within the site was that of Sir William Blake, around 1624. The next owner was Lord Goring, who from 1633 extended Blake's house, which came to be known as Goring House, and developed much of today's garden, then known as Goring Great Garden.Harris, p. 21. He did not, however, obtain the freehold interest in the mulberry garden. Unbeknown to Goring, in 1640 the document "failed to pass the Great Seal before

Possibly the first house erected within the site was that of Sir William Blake, around 1624. The next owner was Lord Goring, who from 1633 extended Blake's house, which came to be known as Goring House, and developed much of today's garden, then known as Goring Great Garden.Harris, p. 21. He did not, however, obtain the freehold interest in the mulberry garden. Unbeknown to Goring, in 1640 the document "failed to pass the Great Seal before Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

fled London, which it needed to do for legal execution". It was this critical omission that would help the British royal family regain the freehold under George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

. When the improvident Goring defaulted on his rents, Henry Bennet, 1st Earl of Arlington

Henry Bennet, 1st Earl of Arlington, KG, PC (1618 – 28 July 1685) was an English statesman.

Background and early life

He was the son of Sir John Bennet of Dawley, Middlesex, by Dorothy, daughter of Sir John Crofts of Little Saxham, Suf ...

was able to purchase the lease of Goring House and he was occupying it when it burned down in 1674, following which he constructed Arlington House on the site—the location of the southern wing of today's palace—the next year. In 1698, John Sheffield acquired the lease. He later became the first Duke of Buckingham and Normanby. Buckingham House was built for Sheffield in 1703 to the design of William Winde

Captain William Winde (c.1645–1722) was an English gentleman architect, whose Royalist military career, resulting in fortifications and topographical surveys but lack of preferment, and his later career, following the Glorious Revolution, as ...

. The style chosen was of a large, three-floored central block with two smaller flanking service wings.Harris, p. 22. It was eventually sold by Buckingham's illegitimate son, Sir Charles Sheffield, in 1761Robinson, p. 14. to George III for £21,000. Sheffield's leasehold

A leasehold estate is an ownership of a temporary right to hold land or property in which a lessee or a tenant holds rights of real property by some form of title from a lessor or landlord. Although a tenant does hold rights to real property, a l ...

on the mulberry garden site, the freehold of which was still owned by the royal family, was due to expire in 1774.

From Queen's House to palace (1761–1837)

Under the new royal ownership, the building was originally intended as a private retreat forQueen Charlotte

Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (Sophia Charlotte; 19 May 1744 – 17 November 1818) was Queen of Great Britain and of Ireland as the wife of King George III from their marriage on 8 September 1761 until the union of the two kingdoms ...

, and was accordingly known as The Queen's House. Remodelling of the structure began in 1762. In 1775, an Act of Parliament settled the property on Queen Charlotte, in exchange for her rights to nearby Somerset House, and 14 of her 15 children were born there. Some furnishings were transferred from Carlton House

Carlton House was a mansion in Westminster, best known as the town residence of King George IV. It faced the south side of Pall Mall, and its gardens abutted St James's Park in the St James's district of London. The location of the house, no ...

and others had been bought in France after the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

of 1789. While St James's Palace remained the official and ceremonial royal residence, the name "Buckingham-palace" was used from at least 1791. After his accession to the throne in 1820, George IV

George IV (George Augustus Frederick; 12 August 1762 – 26 June 1830) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from the death of his father, King George III, on 29 January 1820, until his own death ten y ...

continued the renovation intending to create a small, comfortable home. However, in 1826, while the work was in progress, the King decided to modify the house into a palace with the help of his architect John Nash. The external façade was designed, keeping in mind the French neoclassical influence preferred by George IV. The cost of the renovations grew dramatically, and by 1829 the extravagance of Nash's designs resulted in his removal as the architect. On the death of George IV in 1830, his younger brother William IV

William IV (William Henry; 21 August 1765 – 20 June 1837) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from 26 June 1830 until his death in 1837. The third son of George III, William succeeded h ...

hired Edward Blore to finish the work. William never moved into the palace. After the Palace of Westminster was destroyed by fire in 1834, he offered to convert Buckingham Palace into a new Houses of Parliament, but his offer was declined.

Queen Victoria (1837–1901)

Buckingham Palace became the principal royal residence in 1837, on the accession of Queen Victoria, who was the first monarch to reside there; her predecessor William IV had died before its completion. While the state rooms were a riot of gilt and colour, the necessities of the new palace were somewhat less luxurious. It was reported the chimneys smoked so much that the fires had to be allowed to die down, and consequently the palace was often cold.Woodham-Smith, p. 249. Ventilation was so bad that the interior smelled, and when it was decided to install gas lamps, there was a serious worry about the build-up of gas on the lower floors. It was also said that the staff were lax and lazy and the palace was dirty. Following the Queen's marriage in 1840, her husband, Prince Albert, concerned himself with a reorganisation of the

Buckingham Palace became the principal royal residence in 1837, on the accession of Queen Victoria, who was the first monarch to reside there; her predecessor William IV had died before its completion. While the state rooms were a riot of gilt and colour, the necessities of the new palace were somewhat less luxurious. It was reported the chimneys smoked so much that the fires had to be allowed to die down, and consequently the palace was often cold.Woodham-Smith, p. 249. Ventilation was so bad that the interior smelled, and when it was decided to install gas lamps, there was a serious worry about the build-up of gas on the lower floors. It was also said that the staff were lax and lazy and the palace was dirty. Following the Queen's marriage in 1840, her husband, Prince Albert, concerned himself with a reorganisation of the household

A household consists of two or more persons who live in the same dwelling. It may be of a single family or another type of person group. The household is the basic unit of analysis in many social, microeconomic and government models, and is i ...

offices and staff, and with addressing the design faults of the palace.Rappaport, p. 84. By the end of 1840, all the problems had been rectified. However, the builders were to return within a decade.Rappaport, p. 84.

By 1847, the couple had found the palace too small for court life and their growing family and a new wing, designed by Edward Blore, was built by Thomas Cubitt

Thomas Cubitt (25 February 1788 – 20 December 1855) was a British master builder, notable for his employment in developing many of the historic streets and squares of London, especially in Belgravia, Pimlico and Bloomsbury. His great-great-g ...

, enclosing the central quadrangle. The large East Front, facing The Mall, is today the "public face" of Buckingham Palace and contains the balcony from which the royal family acknowledge the crowds on momentous occasions and after the annual Trooping the Colour

Trooping the Colour is a ceremony performed every year in London, United Kingdom, by regiments of the British Army. Similar events are held in other countries of the Commonwealth. Trooping the Colour has been a tradition of British infantry regi ...

. The ballroom wing and a further suite of state rooms were also built in this period, designed by Nash's student Sir James Pennethorne.King, p. 217. Before Prince Albert's death, the palace was frequently the scene of musical entertainments, and the most celebrated contemporary musicians entertained at Buckingham Palace. The composer Felix Mendelssohn is known to have played there on three occasions. Johann Strauss II and his orchestra played there when in England. Under Victoria, Buckingham Palace was frequently the scene of lavish costume balls, in addition to the usual royal ceremonies, investitures and presentations.

Widowed in 1861, the grief-stricken Queen withdrew from public life and left Buckingham Palace to live at Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a royal residence at Windsor in the English county of Berkshire. It is strongly associated with the English and succeeding British royal family, and embodies almost a millennium of architectural history.

The original c ...

, Balmoral Castle and Osborne House

Osborne House is a former royal residence in East Cowes, Isle of Wight, United Kingdom. The house was built between 1845 and 1851 for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert as a summer home and rural retreat. Albert designed the house himself, in ...

. For many years the palace was seldom used, even neglected. In 1864, a note was found pinned to the fence of Buckingham Palace, saying: "These commanding premises to be let or sold, in consequence of the late occupant's declining business." Eventually, public opinion persuaded the Queen to return to London, though even then she preferred to live elsewhere whenever possible. Court functions were still held at Windsor Castle, presided over by the sombre Queen habitually dressed in mourning black, while Buckingham Palace remained shuttered for most of the year.Robinson, p. 9.

Early 20th century (1901–1945)

In 1901, the new king,Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910.

The second child and eldest son of Queen Victoria and ...

, began redecorating the palace. The King and his wife, Queen Alexandra

Alexandra of Denmark (Alexandra Caroline Marie Charlotte Louise Julia; 1 December 1844 – 20 November 1925) was List of British royal consorts, Queen of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Empress of India, from 22 January 1901 t ...

, had always been at the forefront of London high society, and their friends, known as "the Marlborough House

Marlborough House, a Grade I listed mansion in St James's, City of Westminster, London, is the headquarters of the Commonwealth of Nations and the seat of the Commonwealth Secretariat. It was built in 1711 for Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marl ...

Set", were considered to be the most eminent and fashionable of the age. Buckingham Palace—the Ballroom, Grand Entrance, Marble Hall, Grand Staircase, vestibules and galleries were redecorated in the Belle Époque cream and gold colour scheme they retain today—once again became a setting for entertaining on a majestic scale but leaving some to feel Edward's heavy redecorations were at odds with Nash's original work.

The last major building work took place during the reign of George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Qu ...

when, in 1913, Sir Aston Webb

Sir Aston Webb (22 May 1849 – 21 August 1930) was a British architect who designed the principal facade of Buckingham Palace and the main building of the Victoria and Albert Museum, among other major works around England, many of them in pa ...

redesigned Blore's 1850 East Front to resemble in part Giacomo Leoni

Giacomo Leoni (1686 – 8 June 1746), also known as James Leoni, was an Italian architect, born in Venice. He was a devotee of the work of Florentine Renaissance architect Leon Battista Alberti, who had also been an inspiration for Andrea Pallad ...

's Lyme Park

Lyme Park is a large estate south of Disley, Cheshire, England, managed by the National Trust and consisting of a mansion house surrounded by formal gardens and a deer park in the Peak District National Park. The house is the largest in Ches ...

in Cheshire. This new refaced principal façade (of Portland stone) was designed to be the backdrop to the Victoria Memorial

The Victoria Memorial is a large marble building on the Maidan in Central Kolkata, built between 1906 and 1921. It is dedicated to the memory of Queen Victoria, Empress of India from 1876 to 1901.

The largest monument to a monarch anywhere ...

, a large memorial statue of Queen Victoria created by sculptor Sir Thomas Brock

Sir Thomas Brock (1 March 184722 August 1922) was an English sculptor and medallist, notable for the creation of several large public sculptures and monuments in Britain and abroad in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

His mos ...

, erected outside the main gates on a surround constructed by architect Sir Aston Webb. George V, who had succeeded Edward VII in 1910, had a more serious personality than his father; greater emphasis was now placed on official entertainment and royal duties than on lavish parties. He arranged a series of command performances featuring jazz musicians such as the Original Dixieland Jazz Band

The Original Dixieland Jass Band (ODJB) was a Dixieland jazz band that made the first jazz recordings in early 1917. Their " Livery Stable Blues" became the first jazz record ever issued. The group composed and recorded many jazz standards, the ...

(1919; the first jazz performance for a head of state), Sidney Bechet

Sidney Bechet (May 14, 1897 – May 14, 1959) was an American jazz saxophonist, clarinetist, and composer. He was one of the first important soloists in jazz, and first recorded several months before trumpeter Louis Armstrong. His erratic temp ...

and Louis Armstrong (1932), which earned the palace a nomination in 2009 for a (Kind of) Blue Plaque by the Brecon Jazz Festival

The Brecon Jazz Festival is a music festival held annually in Brecon, Wales. Normally staged in early August, it has played host to a range of jazz musicians from across the world.

Created in 1984 by local enthusiasts – musicians, promoters a ...

as one of the venues making the greatest contribution to jazz music in the United Kingdom.

During the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, which lasted from 1914 until 1918, the palace escaped unscathed. Its more valuable contents were evacuated to Windsor, but the royal family remained in residence. The King imposed rationing

Rationing is the controlled distribution of scarce resources, goods, services, or an artificial restriction of demand. Rationing controls the size of the ration, which is one's allowed portion of the resources being distributed on a particular ...

at the palace, much to the dismay of his guests and household. To the King's later regret, David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during ...

persuaded him to go further and ostentatiously lock the wine cellars and refrain from alcohol, to set a good example to the supposedly inebriated working class. The workers continued to imbibe, and the King was left unhappy at his enforced abstinence.

George V's wife, Queen Mary, was a connoisseur of the arts and took a keen interest in the Royal Collection of furniture and art, both restoring and adding to it. Queen Mary also had many new fixtures and fittings installed, such as the pair of marble Empire-style chimneypieces by Benjamin Vulliamy

Benjamin Vulliamy (1747 – 31 December 1811), was a British clockmaker responsible for building the Regulator Clock, which, between 1780 and 1884, was the main timekeeper of the King's Observatory Kew and the official regulator of time in Londo ...

, dating from 1810, which the Queen had installed in the ground floor Bow Room, the huge low room at the centre of the garden façade. Queen Mary was also responsible for the decoration of the Blue Drawing Room. This room, long, previously known as the South Drawing Room, has a ceiling designed by Nash, coffered with huge gilt console brackets. In 1938, the northwest pavilion, designed by Nash as a conservatory, was converted into a swimming pool.

Second World War

During theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, which broke out in 1939, the palace was bombed nine times. The most serious and publicised incident destroyed the palace chapel in 1940. This event was shown in cinemas throughout the United Kingdom to show the common suffering of the rich and poor. One bomb fell in the palace quadrangle while George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death in 1952. He was also the last Emperor of I ...

and Queen Elizabeth (the future Queen Mother) were in the palace, and many windows were blown in and the chapel destroyed. Wartime coverage of such incidents was severely restricted, however. The King and Queen were filmed inspecting their bombed home; it was at this time the Queen famously declared: "I'm glad we have been bombed. Now I can look the East End in the face". The royal family were seen as sharing their subjects' hardship, as ''The Sunday Graphic

The ''Sunday Graphic'' was an English tabloid newspaper published in Fleet Street.

The newspaper was founded in 1915 as the ''Sunday Herald'' and was later renamed the ''Illustrated Sunday Herald''. In 1927 it changed its name to the ''Sunday ...

'' reported:

On 15 September 1940, known as Battle of Britain Day

Battle of Britain Day, 15 September 1940, is the day on which a large-scale aerial battle in the Battle of Britain took place.Mason 1969, p. 386.Price 1990, p. 128.

In June 1940, the '' Wehrmacht'' had conquered most of Western Europe and Sc ...

, an RAF pilot, Ray Holmes

Raymond Towers Holmes (20 August 1914 – 27 June 2005) was a British Royal Air Force fighter pilot during the Second World War who is best known for taking part in the Battle of Britain. He became famous for an apparent notable act of bravery ...

of No. 504 Squadron RAF

No. 504 (County of Nottingham) Squadron was one of the Special Reserve Squadrons of the Auxiliary Air Force, and today is a reserve force of the RAF Regiment. It was integrated into the AAF proper in 1936. Based at RAF Cottesmore, Rutland, 504 Sq ...

rammed a German Dornier Do 17

The Dornier Do 17 is a twin-engined light bomber produced by Dornier Flugzeugwerke for the German Luftwaffe during World War II. Designed in the early 1930s as a '' Schnellbomber'' ("fast bomber") intended to be fast enough to outrun opposing a ...

bomber he believed was going to bomb the Palace. Holmes had run out of ammunition and made the quick decision to ram it. Holmes bailed out and the aircraft crashed into the forecourt of London Victoria station

Victoria station, also known as London Victoria, is a London station group, central London railway terminus and connected London Underground station in Victoria, London, Victoria, in the City of Westminster, managed by Network Rail. Named after ...

. The bomber's engine was later exhibited at the Imperial War Museum in London. The British pilot became a King's Messenger

The Corps of King's Messengers (or Corps of Queen's Messengers during the reign of a female monarch) are couriers employed by the British Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO). They hand-carry secret and important documents to Br ...

after the war and died at the age of 90 in 2005. On VE Day

Victory in Europe Day is the day celebrating the formal acceptance by the Allies of World War II of Germany's unconditional surrender of its armed forces on Tuesday, 8 May 1945, marking the official end of World War II in Europe in the Easter ...

—8 May 1945—the palace was the centre of British celebrations. The King, the Queen, Princess Elizabeth (the future queen) and Princess Margaret appeared on the balcony, with the palace's blacked-out windows behind them, to cheers from a vast crowd in The Mall. The damaged Palace was carefully restored after the war by John Mowlem

Mowlem was one of the largest construction and civil engineering companies in the United Kingdom. Carillion bought the firm in 2006.

History

The firm was founded by John Mowlem in 1822, and was continued as a partnership by successive generat ...

& Co.

Mid 20th century to present day

Many of the palace's contents are part of the Royal Collection, held in trust by

Many of the palace's contents are part of the Royal Collection, held in trust by King Charles III

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms. He was the longest-serving heir apparent and Prince of Wales and, at age 73, became the oldest person to a ...

; they can, on occasion, be viewed by the public at the Queen's Gallery

The Queen's Gallery is the main public art gallery of Buckingham Palace, home of the British monarch, in London. It exhibits works of art from the Royal Collection (the bulk of which works have since its opening been regularly displayed, s ...

, near the Royal Mews. The purpose-built gallery opened in 1962 and displays a changing selection of items from the collection. It occupies the site of the chapel that was destroyed in the Second World War. The palace was designated a Grade I listed building

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern Irel ...

in 1970. Its state rooms have been open to the public during August and September and on some dates throughout the year since 1993. The money raised in entry fees was originally put towards the rebuilding of Windsor Castle after the 1992 fire devastated many of its staterooms. In the year to 31 March 2017, 580,000 people visited the palace, and 154,000 visited the gallery.

The palace used to racially segregate staff. In 1968, Charles Tryon, 2nd Baron Tryon __NOTOC__

Brigadier Charles George Vivian Tryon, 2nd Baron Tryon, (24 May 1906 – 9 November 1976) was a British peer, British Army officer, and a member of the Royal Household.

Early life and military career

Elder son of George, 1st Baron Tr ...

, acting as treasurer to Queen Elizabeth II, sought to exempt Buckingham Palace from full application of the Race Relations Act 1968

The Race Relations Act 1968 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom making it illegal to refuse housing, employment, or public services to a person on the grounds of colour, race, ethnic or national origins in Great Britain (although n ...

. He stated that the palace did not hire people of colour for clerical jobs, only as domestic servants. He arranged with Civil servants for an exemption that meant that complaints of racism against the royal household would be sent directly to the Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national s ...

and kept out of the legal system.

The palace, like Windsor Castle, is owned by the reigning monarch in right of the Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has different ...

. Occupied royal palaces are not part of the Crown Estate

The Crown Estate is a collection of lands and holdings in the United Kingdom belonging to the British monarch as a corporation sole, making it "the sovereign's public estate", which is neither government property nor part of the monarch's priv ...

, nor are they the monarch's personal property, unlike Sandringham House

Sandringham House is a country house in the parish of Sandringham, Norfolk, England. It is one of the royal residences of Charles III, whose grandfather, George VI, and great-grandfather, George V, both died there. The house stands in a estat ...

and Balmoral Castle. The Government of the United Kingdom

ga, Rialtas a Shoilse gd, Riaghaltas a Mhòrachd

, image = HM Government logo.svg

, image_size = 220px

, image2 = Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom (HM Government).svg

, image_size2 = 180px

, caption = Royal Arms

, date_es ...

is responsible for maintaining the palace in exchange for the profits made by the Crown Estate. In 2015, the State Dining Room was closed for a year and a half because its ceiling had become potentially dangerous. A 10-year schedule of maintenance work, including new plumbing, wiring, boilers and radiators, and the installation of solar panels on the roof, has been estimated to cost £369 million and was approved by the prime minister in November 2016. It will be funded by a temporary increase in the Sovereign Grant

The Sovereign Grant Act 2011 (c. 15) is the Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which introduced the Sovereign Grant, the payment which is paid annually to the monarch by the government in order to fund the monarch's official duties. It ...

paid from the income of the Crown Estate and is intended to extend the building's working life by at least 50 years. In 2017, the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

backed funding for the project by 464 votes to 56.

Buckingham Palace is a symbol and home of the British monarchy, an art gallery and a tourist attraction. Behind the gilded railings and gates that were completed by the Bromsgrove Guild

The Bromsgrove Guild of Applied Arts (1898–1966) was a company of modern artists and designers associated with the Arts and Crafts Movement, founded by Walter Gilbert. The guild worked in metal, wood, plaster, bronze, tapestry, glass and ...

in 1911, lies Webb's famous façade, which was described in a book published by the Royal Collection Trust

The Royal Collection of the British royal family is the largest private art collection in the world.

Spread among 13 occupied and historic royal residences in the United Kingdom, the collection is owned by King Charles III and overseen by the ...

as looking "like everybody's idea of a palace". It has not only been a weekday home of Elizabeth II and Prince Philip but is also the London residence of the Duke of York and the Earl

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. The title originates in the Old English word ''eorl'', meaning "a man of noble birth or rank". The word is cognate with the Scandinavian form ''jarl'', and meant "chieftain", particular ...

and Countess of Wessex

Earl of Wessex is a title that has been created twice in British history – once in the pre-Conquest Anglo-Saxon nobility of England, and once in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. In the 6th century AD the region of Wessex (the lands of the W ...

. The palace also houses their offices, as well as those of the Princess Royal

Princess Royal is a style customarily (but not automatically) awarded by a British monarch to their eldest daughter. Although purely honorary, it is the highest honour that may be given to a female member of the royal family. There have been se ...

and Princess Alexandra, and is the workplace of more than 800 people. Charles III

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms. He was the longest-serving heir apparent and Prince of Wales and, at age 73, became the oldest person t ...

lives at Clarence House

Clarence House is a royal residence on The Mall in the City of Westminster, London. It was built in 1825–1827, adjacent to St James's Palace, for the Duke of Clarence, the future king William IV.

Over the years, it has undergone much exten ...

while restoration work continues, although he conducts official business at Buckingham Palace, including weekly meetings with the Prime Minister. Every year, some 50,000 invited guests are entertained at garden parties, receptions, audiences and banquets. Three garden parties are held in the summer, usually in July. The forecourt of Buckingham Palace is used for the Changing of the Guard

Guard mounting, changing the guard, or the changing of the guard, is a formal ceremony in which sentries performing ceremonial guard duties at important institutions are relieved by a new batch of sentries. The ceremonies are often elaborate a ...

, a major ceremony and tourist attraction (daily from April to July; every other day in other months).

Interior

The front of the palace measures across, by deep, by high and contains over of floorspace. There are 775 rooms, including 188 staff bedrooms, 92 offices, 78 bathrooms, 52 principal bedrooms and 19 state rooms. It also has a

The front of the palace measures across, by deep, by high and contains over of floorspace. There are 775 rooms, including 188 staff bedrooms, 92 offices, 78 bathrooms, 52 principal bedrooms and 19 state rooms. It also has a post office

A post office is a public facility and a retailer that provides mail services, such as accepting letters and parcels, providing post office boxes, and selling postage stamps, packaging, and stationery. Post offices may offer additional serv ...

, cinema, swimming pool, doctor's surgery and jeweller's workshop. The Royal family occupy a small suite of private rooms in the north wing.

Principal rooms

The principal rooms are contained on the first-floor '' piano nobile'' behind the west-facing garden façade at the rear of the palace. The centre of this ornate suite of state rooms is the Music Room, its large bow the dominant feature of the façade. Flanking the Music Room are the Blue and the White Drawing Rooms. At the centre of the suite, serving as a corridor to link the state rooms, is the Picture Gallery, which is top-lit and long.Harris, p. 41. The Gallery is hung with numerous works including some by Rembrandt,

The principal rooms are contained on the first-floor '' piano nobile'' behind the west-facing garden façade at the rear of the palace. The centre of this ornate suite of state rooms is the Music Room, its large bow the dominant feature of the façade. Flanking the Music Room are the Blue and the White Drawing Rooms. At the centre of the suite, serving as a corridor to link the state rooms, is the Picture Gallery, which is top-lit and long.Harris, p. 41. The Gallery is hung with numerous works including some by Rembrandt, van Dyck

Sir Anthony van Dyck (, many variant spellings; 22 March 1599 – 9 December 1641) was a Brabantian Flemish Baroque artist who became the leading court painter in England after success in the Southern Netherlands and Italy.

The seventh ...

, Rubens and Vermeer

Johannes Vermeer ( , , see below; also known as Jan Vermeer; October 1632 – 15 December 1675) was a Dutch Baroque Period painter who specialized in domestic interior scenes of middle-class life. During his lifetime, he was a moderately succe ...

; other rooms leading from the Picture Gallery are the Throne Room

A throne room or throne hall is the room, often rather a hall, in the official residence of the crown, either a palace or a fortified castle, where the throne of a senior figure (usually a monarch) is set up with elaborate pomp—usually raised, ...

and the Green Drawing Room. The Green Drawing Room serves as a huge anteroom to the Throne Room, and is part of the ceremonial route to the throne from the Guard Room at the top of the Grand Staircase. The Guard Room contains white marble statues of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, in Roman costume, set in a tribune

Tribune () was the title of various elected officials in ancient Rome. The two most important were the tribunes of the plebs and the military tribunes. For most of Roman history, a college of ten tribunes of the plebs acted as a check on th ...

lined with tapestries. These very formal rooms are used only for ceremonial and official entertaining but are open to the public every summer.

Semi-state apartments

Directly underneath the state apartments are the less grand semi-state apartments. Opening from the Marble Hall, these rooms are used for less formal entertaining, such as luncheon parties and private

Directly underneath the state apartments are the less grand semi-state apartments. Opening from the Marble Hall, these rooms are used for less formal entertaining, such as luncheon parties and private audiences

An audience is a group of people who participate in a show or encounter a work of art, literature (in which they are called "readers"), theatre, music (in which they are called "listeners"), video games (in which they are called "players"), or ...

. At the centre of this floor is the Bow Room, through which thousands of guests pass annually to the monarch's garden parties

A party is a gathering of people who have been invited by a host for the purposes of socializing, conversation, recreation, or as part of a festival or other commemoration or celebration of a special occasion. A party will often feature ...

. When paying a state visit to Britain, foreign heads of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and ...

are usually entertained by the monarch at Buckingham Palace. They are allocated an extensive suite of rooms known as the Belgian Suite, situated at the foot of the Minister's Staircase, on the ground floor of the west-facing Garden Wing. Some of the rooms are named and decorated for particular visitors, such as the 1844 Room, decorated in that year for the state visit of Nicholas I of Russia

, house = Romanov-Holstein-Gottorp

, father = Paul I of Russia

, mother = Maria Feodorovna (Sophie Dorothea of Württemberg)

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Gatchina Palace, Gatchina, Russian Empire

, death_date = ...

, and the 1855 Room, in honour of the visit of Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

of France. The former is a sitting room that also serves as an audience room and is often used for personal investitures. Narrow corridors link the rooms of the suite, one of them is given extra height and perspective by saucer dome

A dome () is an architectural element similar to the hollow upper half of a sphere. There is significant overlap with the term cupola, which may also refer to a dome or a structure on top of a dome. The precise definition of a dome has been a m ...

s designed by Nash in the style of Soane.Harris, p. 82. A second corridor in the suite has Gothic-influenced cross-over vaulting. The suite was named after Leopold I of Belgium

* nl, Leopold Joris Christiaan Frederik

* en, Leopold George Christian Frederick

, image = NICAISE Leopold ANV.jpg

, caption = Portrait by Nicaise de Keyser, 1856

, reign = 21 July 1831 –

, predecessor = Erasme Lou ...

, uncle of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. In 1936, the suite briefly became the private apartments of the palace when Edward VIII occupied them. The original early-19th-century interior designs, many of which still survive, included widespread use of brightly coloured scagliola

Scagliola (from the Italian ''scaglia'', meaning "chips") is a type of fine plaster used in architecture and sculpture. The same term identifies the technique for producing columns, sculptures, and other architectural elements that resemble inla ...

and blue and pink lapis

Lapis lazuli (; ), or lapis for short, is a deep-blue metamorphic rock used as a semi-precious stone that has been prized since antiquity for its intense color.

As early as the 7th millennium BC, lapis lazuli was mined in the Sar-i Sang mines ...

, on the advice of Sir Charles Long. Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910.

The second child and eldest son of Queen Victoria and ...

oversaw a partial redecoration in a Belle Époque cream and gold colour scheme.Jones, p. 43.

East wing

Between 1847 and 1850, when Blore was building the new east wing, theBrighton Pavilion

The Royal Pavilion, and surrounding gardens, also known as the Brighton Pavilion, is a Grade I listed former royal residence located in Brighton, England. Beginning in 1787, it was built in three stages as a seaside retreat for George, Prin ...

was once again plundered of its fittings. As a result, many of the rooms in the new wing have a distinctly oriental atmosphere. The red and blue Chinese Luncheon Room is made up of parts of the Brighton Banqueting and Music Rooms with a large oriental chimneypiece designed by Robert Jones and sculpted by Richard Westmacott

Sir Richard Westmacott (15 July 17751 September 1856) was a British sculptor.

Life and career

Westmacott studied with his father, also named Richard Westmacott, at his studio in Mount Street, off Grosvenor Square in London before going t ...

.Harris, de Bellaigue & Miller, p. 87. It was formerly in the Music Room at the Brighton Pavilion. The ornate clock, known as the Kylin Clock, was made in Jingdezhen, Jiangxi Province, China, in the second half of the 18th century; it has a later movement by Benjamin Vulliamy

Benjamin Vulliamy (1747 – 31 December 1811), was a British clockmaker responsible for building the Regulator Clock, which, between 1780 and 1884, was the main timekeeper of the King's Observatory Kew and the official regulator of time in Londo ...

circa 1820. The Yellow Drawing Room has wallpaper supplied in 1817 for the Brighton Saloon, and a chimneypiece which is a European vision of how the Chinese chimney piece may appear. It has nodding mandarins in niches and fearsome winged dragons

A dragon is a reptilian legendary creature that appears in the folklore of many cultures worldwide. Beliefs about dragons vary considerably through regions, but dragons in western cultures since the High Middle Ages have often been depicted as ...

, designed by Robert Jones.

At the centre of this wing is the famous balcony with the Centre Room behind its glass doors. This is a Chinese-style saloon enhanced by Queen Mary, who, working with the designer Sir Charles Allom

Sir Charles Carrick Allom (1865–1947) was an eminent English decorator, trained as an architect and knighted for his work on Buckingham Palace. He was the grandson of architect Thomas Allom and painter Thomas Carrick. Among his American clie ...

, created a more "binding" Chinese theme in the late 1920s, although the lacquer doors were brought from Brighton in 1873. Running the length of the ''piano nobile'' of the east wing is the Great Gallery, modestly known as the Principal Corridor, which runs the length of the eastern side of the quadrangle. It has mirrored doors and mirrored cross walls reflecting porcelain

Porcelain () is a ceramic material made by heating substances, generally including materials such as kaolinite, in a kiln to temperatures between . The strength and translucence of porcelain, relative to other types of pottery, arises main ...

pagodas and other oriental furniture from Brighton. The Chinese Luncheon Room and Yellow Drawing Room are situated at each end of this gallery, with the Centre Room in between.

Court ceremonies

Investiture

Investiture (from the Latin preposition ''in'' and verb ''vestire'', "dress" from ''vestis'' "robe") is a formal installation or ceremony that a person undergoes, often related to membership in Christian religious institutes as well as Christian k ...

s, which include the conferring of knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the Gr ...

hoods by dubbing with a sword, and other awards take place in the palace's Ballroom, built in 1854. At long, wide and high, it is the largest room in the palace. It has replaced the throne room in importance and use. During investitures, the King stands on the throne dais beneath a giant, domed velvet canopy, known as a ''shamiana

A ''shamiana'' ( Bengali: শামিয়ানা, Urdu: شامیانہ ) is a South Asian ceremonial tent, shelter or awning, commonly used for outdoor parties, weddings, feasts etc. Its side walls are removable. The external fabric can ...

'' or a baldachin

A baldachin, or baldaquin (from it, baldacchino), is a canopy of state typically placed over an altar or throne. It had its beginnings as a cloth canopy, but in other cases it is a sturdy, permanent architectural feature, particularly over hi ...

, that was used at the Delhi Durbar in 1911. A military band plays in the musicians' gallery as award recipients approach the King and receive their honour

Honour (British English) or honor (American English; see spelling differences) is the idea of a bond between an individual and a society as a quality of a person that is both of social teaching and of personal ethos, that manifests itself as a ...

s, watched by their families and friends.Healey, p. 364.

State banquets also take place in the Ballroom; these formal dinners are held on the first evening of a state visit by a foreign head of state. On these occasions, for up to 170 guests in formal "white tie and decorations", including tiaras, the dining table is laid with the Grand Service, a collection of silver-gilt plate made in 1811 for the Prince of Wales, later George IV. The largest and most formal reception at Buckingham Palace takes place every November when the King entertains members of the

State banquets also take place in the Ballroom; these formal dinners are held on the first evening of a state visit by a foreign head of state. On these occasions, for up to 170 guests in formal "white tie and decorations", including tiaras, the dining table is laid with the Grand Service, a collection of silver-gilt plate made in 1811 for the Prince of Wales, later George IV. The largest and most formal reception at Buckingham Palace takes place every November when the King entertains members of the diplomatic corps

The diplomatic corps (french: corps diplomatique) is the collective body of foreign diplomats accredited to a particular country or body.

The diplomatic corps may, in certain contexts, refer to the collection of accredited heads of mission ( ...

. On this grand occasion, all the state rooms are in use, as the royal family proceed through them, beginning at the great north doors of the Picture Gallery. As Nash had envisaged, all the large, double-mirrored doors stand open, reflecting the numerous crystal chandeliers and sconces, creating a deliberate optical illusion of space and light.

Smaller ceremonies such as the reception of new ambassadors take place in the "1844 Room". Here too, the King holds small lunch parties, and often meetings of the Privy Council. Larger lunch parties often take place in the curved and domed Music Room or the State Dining Room.Healey, pp. 363–365. Since the bombing of the palace chapel in World War II, royal christenings have sometimes taken place in the Music Room. Queen Elizabeth II's first three children were all baptised there. On all formal occasions, the ceremonies are attended by the Yeomen of the Guard

The King's Body Guard of the Yeomen of the Guard is a bodyguard of the British monarch. The oldest British military corps still in existence, it was created by King Henry VII in 1485 after the Battle of Bosworth Field.

History

The king ...

, in their historic uniforms, and other officers of the court such as the Lord Chamberlain

The Lord Chamberlain of the Household is the most senior officer of the Royal Household of the United Kingdom, supervising the departments which support and provide advice to the Sovereign of the United Kingdom while also acting as the main c ...

.

Former ceremonial

Court dress

Formerly, men not wearingmilitary uniform

A military uniform is a standardised dress worn by members of the armed forces and paramilitaries of various nations.

Military dress and styles have gone through significant changes over the centuries, from colourful and elaborate, ornamented ...

wore knee breeches

Breeches ( ) are an article of clothing covering the body from the waist down, with separate coverings for each leg, usually stopping just below the knee, though in some cases reaching to the ankles. Formerly a standard item of Western men's c ...

of 18th-century design. Women's evening dress included trains and tiara

A tiara (from la, tiara, from grc, τιάρα) is a jeweled head ornament. Its origins date back to ancient Greece and Rome. In the late 18th century, the tiara came into fashion in Europe as a prestigious piece of jewelry to be worn by women ...

s or feathers in their hair (often both). The dress code governing formal court uniform and dress has progressively relaxed. After the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, when Queen Mary wished to follow fashion by raising her skirts a few inches from the ground, she requested a lady-in-waiting to shorten her own skirt first to gauge the King's reaction. King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Qu ...

disapproved, so the Queen kept her hemline unfashionably low. Following his accession in 1936, King George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death in 1952. He was also the last Emperor of I ...

and Queen Elizabeth allowed the hemline of daytime skirts to rise. Today, there is no official dress code. Most men invited to Buckingham Palace in the daytime choose to wear service uniform or lounge suits; a minority wear morning coats, and in the evening, depending on the formality of the occasion, black tie or white tie

White tie, also called full evening dress or a dress suit, is the most formal in traditional evening western dress codes. For men, it consists of a black tail coat (alternatively referred to as a dress coat, usually by tailors) worn over a wh ...

.

Court presentation of débutantes

Débutante

A debutante, also spelled débutante, ( ; from french: débutante , "female beginner") or deb is a young woman of aristocratic or upper-class family background who has reached maturity and, as a new adult, is presented to society at a formal ...

s were aristocratic young ladies making their first entrée into society through a presentation to the monarch at court. These occasions, known as "coming out", took place at the palace from the reign of Edward VII. The débutantes entered—wearing full court dress, with three ostrich feathers in their hair—curtsied, performed a backwards walk and a further curtsey, while manoeuvring a dress train of prescribed length. The ceremony, known as an evening court, corresponded to the "court drawing room

A drawing room is a room in a house where visitors may be entertained, and an alternative name for a living room. The name is derived from the 16th-century terms withdrawing room and withdrawing chamber, which remained in use through the 17th cent ...

s" of Victoria's reign. After World War II, the ceremony was replaced by less formal afternoon receptions, omitting the requirement of court evening dress. In 1958, Queen Elizabeth II abolished the presentation parties for débutantes, replacing them with Garden Parties

A party is a gathering of people who have been invited by a host for the purposes of socializing, conversation, recreation, or as part of a festival or other commemoration or celebration of a special occasion. A party will often feature ...

, for up to 8,000 invitees in the Garden. They are the largest functions of the year.

Garden and surroundings

At the rear of the palace is the large and park-like garden, which together with its lake is the largest private garden in London. There, Queen Elizabeth II hosted her annual garden parties each summer and also held large functions to celebrate royal milestones, such as jubilees. It covers and includes a helicopter landing area, a lake and a tennis court. Adjacent to the palace is theRoyal Mews

The Royal Mews is a mews, or collection of equestrian stables, of the British Royal Family. In London these stables and stable-hands' quarters have occupied two main sites in turn, being located at first on the north side of Charing Cross, and ...

, also designed by Nash, where the royal carriages, including the Gold State Coach

The Gold State Coach is an enclosed, eight-horse-drawn carriage used by the British Royal Family. Commissioned in 1760 by Francis Rawdon-Hastings, 1st Marquess of Hastings for King George III, it was built in the London workshops of Samuel Bu ...

, are housed. This rococo

Rococo (, also ), less commonly Roccoco or Late Baroque, is an exceptionally ornamental and theatrical style of architecture, art and decoration which combines asymmetry, scrolling curves, gilding, white and pastel colours, sculpted moulding, ...

gilt coach, designed by Sir William Chambers

__NOTOC__

Sir William Chambers (23 February 1723 – 10 March 1796) was a Swedish-Scottish architect, based in London. Among his best-known works are Somerset House, and the pagoda at Kew. Chambers was a founder member of the Royal Academy.

Bio ...

in 1760, has painted panels by G. B. Cipriani. It was first used for the State Opening of Parliament by George III in 1762 and has been used by the monarch for every coronation since George IV. It was last used for the Golden Jubilee of Elizabeth II

The Golden Jubilee of Elizabeth II was the international celebration held in 2002 marking the 50th anniversary of the accession of Queen Elizabeth II on 6 February 1952. It was intended by the Queen to be both a commemoration of her 50 years as ...

. Also housed in the mews are the coach horses used at royal ceremonial processions.

The Mall, a ceremonial approach route to the palace, was designed by Sir Aston Webb

Sir Aston Webb (22 May 1849 – 21 August 1930) was a British architect who designed the principal facade of Buckingham Palace and the main building of the Victoria and Albert Museum, among other major works around England, many of them in pa ...

and completed in 1911 as part of a grand memorial to Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previo ...

. It extends from Admiralty Arch

Admiralty Arch is a landmark building in London providing road and pedestrian access between The Mall, which extends to the southwest, and Trafalgar Square to the northeast. Admiralty Arch, commissioned by King Edward VII in memory of his mo ...

, across St James's Park

St James's Park is a park in the City of Westminster, central London. It is at the southernmost tip of the St James's area, which was named after a leper hospital dedicated to St James the Less. It is the most easterly of a near-continuous ch ...

to the Victoria Memorial

The Victoria Memorial is a large marble building on the Maidan in Central Kolkata, built between 1906 and 1921. It is dedicated to the memory of Queen Victoria, Empress of India from 1876 to 1901.

The largest monument to a monarch anywhere ...

. This route is used by the cavalcades and motorcades of visiting heads of state, and by the royal family on state occasions—such as the annual Trooping the Colour

Trooping the Colour is a ceremony performed every year in London, United Kingdom, by regiments of the British Army. Similar events are held in other countries of the Commonwealth. Trooping the Colour has been a tradition of British infantry regi ...

.

Security breaches

The boy Jones

Edward "the boy" Jones (1824 – 26 December 1893) was a Briton who became notorious for breaking into Buckingham Palace multiple times between 1838 and 1841.

Biography Early life

Edward Jones was the son of a tailor in Westminster.

Arrests

In ...

was an intruder who gained entry to the palace on three occasions between 1838 and 1841. Dickens, Charles (5 July 1885)The boy Jones

, '' All the Year Round'', pp. 234–37. At least 12 people have managed to gain unauthorised entry into the palace or its grounds since 1914, including Michael Fagan, who broke into the palace twice in 1982 and entered Queen Elizabeth II's bedroom on the second occasion. At the time, news media reported that he had a long conversation with her while she waited for security officers to arrive, but in a 2012 interview with ''

The Independent

''The Independent'' is a British online newspaper. It was established in 1986 as a national morning printed paper. Nicknamed the ''Indy'', it began as a broadsheet and changed to tabloid format in 2003. The last printed edition was publish ...

'', Fagan said she ran out of the room, and no conversation took place. It was only in 2007 that trespassing on the palace grounds became a specific criminal offence.

See also

*Flags at Buckingham Palace

Flags at Buckingham Palace vary according to the movements of court and tradition. The King's Flag Sergeant is responsible for all flags flown from the palace.

Tradition

Until 1997 the only flag to fly from Buckingham Palace was the Royal ...

* List of British royal residences

British royal residences are palaces, castles and houses occupied by members of the British royal family in the United Kingdom. Some, like Buckingham Palace and Windsor Castle, are owned by the Crown (ownership by the British monarch ...

* King's Guard

The King's Guard and King's Life Guard (called the Queen's Guard and the Queen's Life Guard when the reigning monarch is female) are the contingents of infantry and cavalry soldiers charged with guarding the official royal residences in the ...

Notes

References

Bibliography

* Allison, Ronald; Riddell, Sarah (1991). ''The Royal Encyclopedia''. London: Macmillan. * Blaikie, Thomas (2002). ''You Look Awfully Like the Queen: Wit and Wisdom from the House of Windsor''. London: HarperCollins. . * Goring, O. G. (1937). ''From Goring House to Buckingham Palace''. London: Ivor Nicholson & Watson. * Harris, John; de Bellaigue, Geoffrey; & Miller, Oliver (1968). ''Buckingham Palace''. London: Nelson. . * Healey, Edma (1997). ''The Queen's House: A Social History of Buckingham Palace''. London: Penguin Group. . * Hedley, Olwen (1971) ''The Pictorial History of Buckingham Palace''. Pitkin, . * * * Mackenzie, Compton (1953). ''The Queen's House''. London: Hutchinson. * Nash, Roy (1980). ''Buckingham Palace: The Place and the People''. London: Macdonald Futura. . * * * Robinson, John Martin (1999). ''Buckingham Palace''. Published by The Royal Collection, St James's Palace, London . * Williams, Neville (1971). ''Royal Homes''. The Lutterworth Press. . * Woodham-Smith, Cecil (1973). ''Queen Victoria'' ''(vol 1)'' Hamish Hamilton Ltd. * Wright, Patricia (1999; first published 1996). ''The Strange History of Buckingham Palace''. Stroud, Gloucs.: Sutton Publishing Ltd. .External links

Buckingham Palace

at the Royal Family website

Account of Buckingham Palace, with prints of Arlington House and Buckingham House

from ''Old and New London'' (1878)

Account of the acquisition of the Manor of Ebury

from ''Survey of London'' (1977)

The State Rooms, Buckingham Palace

at the

Royal Collection Trust

The Royal Collection of the British royal family is the largest private art collection in the world.

Spread among 13 occupied and historic royal residences in the United Kingdom, the collection is owned by King Charles III and overseen by the ...

*

{{Authority control, suppress=MBP

1837 establishments in England

Buildings and structures on The Mall, London

Edward Blore buildings

Edwardian architecture in London

Georgian architecture in London

Grade I listed buildings in the City of Westminster

Grade I listed palaces

Historic house museums in London

Houses completed in 1703

Houses completed in 1762

John Nash buildings

Museums in the City of Westminster

Neoclassical architecture in London

Neoclassical palaces

Palaces in London

Regency architecture in London

Royal buildings in London

Royal residences in the City of Westminster

Terminating vistas in the United Kingdom

Tourist attractions in the City of Westminster

Geographical articles missing image alternative text