The British Empire was composed of the

dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 192 ...

s,

colonies

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the '' metropolitan state'' ...

,

protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over most of its int ...

s,

mandates, and other

territories

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, particularly belonging or connected to a country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually either the total area from which a state may extract power resources or a ...

ruled or administered by the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

and its predecessor states. It began with the

overseas possessions and

trading post

A trading post, trading station, or trading house, also known as a factory, is an establishment or settlement where goods and services could be traded.

Typically the location of the trading post would allow people from one geographic area to tr ...

s established by

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

between the late 16th and early 18th centuries.

At its height it was the

largest empire in history and, for over a century, was the foremost global power. By 1913, the British Empire held sway over 412 million people, of the world population at the time, and by 1920, it covered , of the Earth's total land area. As a result, its

constitutional

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these prin ...

,

legal

Law is a set of rules that are created and are law enforcement, enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. ...

,

linguistic

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure. Linguis ...

, and

cultural legacy is widespread. At the peak of its power, it was described as "

the empire on which the sun never sets

The phrase "the empire on which the sun never sets" ( es, el imperio donde nunca se pone el sol) was used to describe certain global empires that were so extensive that it seemed as though it was always daytime in at least one part of its territ ...

", as the Sun was always shining on at least one of its territories.

During the

Age of Discovery

The Age of Discovery (or the Age of Exploration), also known as the early modern period, was a period largely overlapping with the Age of Sail, approximately from the 15th century to the 17th century in European history, during which seafarin ...

in the 15th and 16th centuries,

Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

and

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

pioneered European exploration of the globe, and in the process established large overseas empires. Envious of the great wealth these empires generated, England,

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

, and the

Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

began to establish colonies and trade networks of their own in the

Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

and

Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an are ...

. A series of wars in the 17th and 18th centuries with the Netherlands and France left England (

Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

, following the

1707 Act of Union with Scotland) the dominant

colonial power

Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing colonies and generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose their relig ...

in

North America. Britain became the dominant power in the

Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a list of the physiographic regions of the world, physiographical region in United Nations geoscheme for Asia#Southern Asia, Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian O ...

after the

East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and South ...

's

conquest

Conquest is the act of military subjugation of an enemy by force of arms.

Military history provides many examples of conquest: the Roman conquest of Britain, the Mauryan conquest of Afghanistan and of vast areas of the Indian subcontinent, t ...

of

Mughal Bengal

The Bengal Subah ( bn, সুবাহ বাংলা; fa, ), also referred to as Mughal Bengal ( bn, মোগল বাংলা), was the largest subdivision of the Mughal Empire (and later an independent state under the Nawabs of Beng ...

at the

Battle of Plassey in 1757.

The

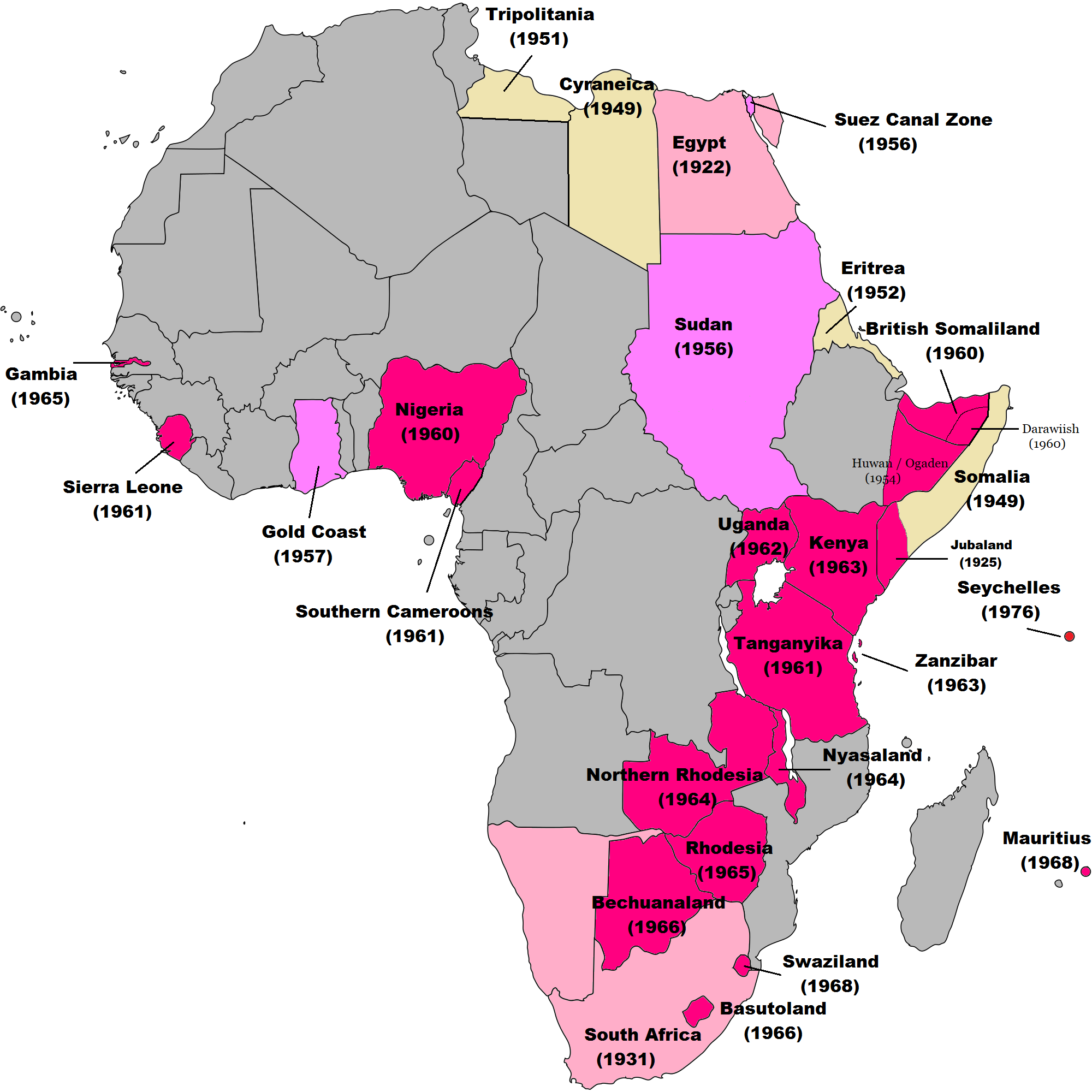

American War of Independence resulted in Britain losing some of its oldest and most populous colonies in North America by 1783. British attention then turned towards Asia,

Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

, and the

Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

. After the defeat of France in the

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

(1803–1815), Britain emerged as the principal naval and imperial power of the 19th century and expanded its imperial holdings. The period of relative peace (1815–1914) during which the British Empire became the global

hegemon

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one state over other states. In Ancient Greece (8th BC – AD 6th ), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of the ''hegemon'' city-state over other city-states. ...

was later described as ("British Peace"). Alongside the formal control that Britain exerted over its colonies, its dominance of much of world trade meant that it effectively

controlled the economies of many regions, such as Asia and

Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived f ...

.

Porter

Porter may refer to:

Companies

* Porter Airlines, Canadian regional airline based in Toronto

* Porter Chemical Company, a defunct U.S. toy manufacturer of chemistry sets

* Porter Motor Company, defunct U.S. car manufacturer

* H.K. Porter, Inc., ...

, p. 8.Marshall

Marshall may refer to:

Places

Australia

* Marshall, Victoria, a suburb of Geelong, Victoria

Canada

* Marshall, Saskatchewan

* The Marshall, a mountain in British Columbia

Liberia

* Marshall, Liberia

Marshall Islands

* Marshall Islands, an i ...

, pp. 156–57. Increasing degrees of autonomy were granted to its white

settler colonies, some of which were reclassified as

Dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 192 ...

s.

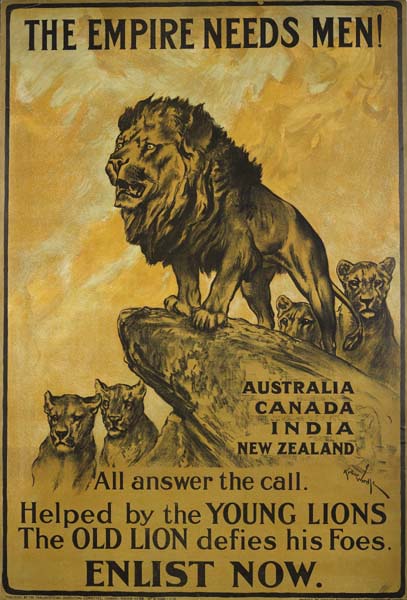

By the start of the 20th century,

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

and the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

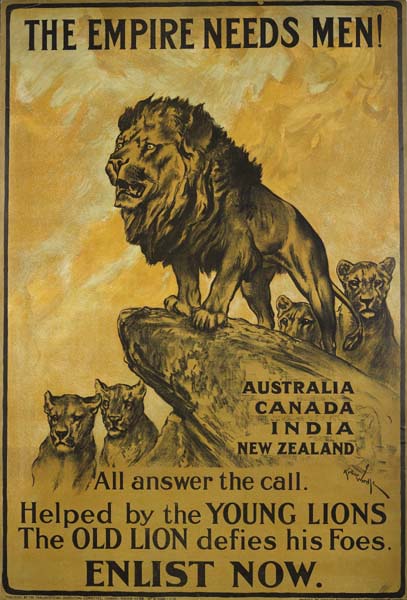

had begun to challenge Britain's economic lead. Military and economic tensions between Britain and Germany were major causes of the

First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, during which Britain relied heavily on its empire. The conflict placed enormous strain on its military, financial, and manpower resources. Although the empire achieved its largest territorial extent immediately after the First World War, Britain was no longer the world's preeminent industrial or military power. In the

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, Britain's colonies in

East Asia

East Asia is the eastern region of Asia, which is defined in both Geography, geographical and culture, ethno-cultural terms. The modern State (polity), states of East Asia include China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. ...

and

Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical south-eastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of mainlan ...

were occupied by the

Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of Japan, 1947 constitu ...

. Despite the final victory of Britain and

its allies, the damage to British prestige helped accelerate the decline of the empire.

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, Britain's most valuable and populous possession, achieved

independence

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the statu ...

in 1947 as part of a larger

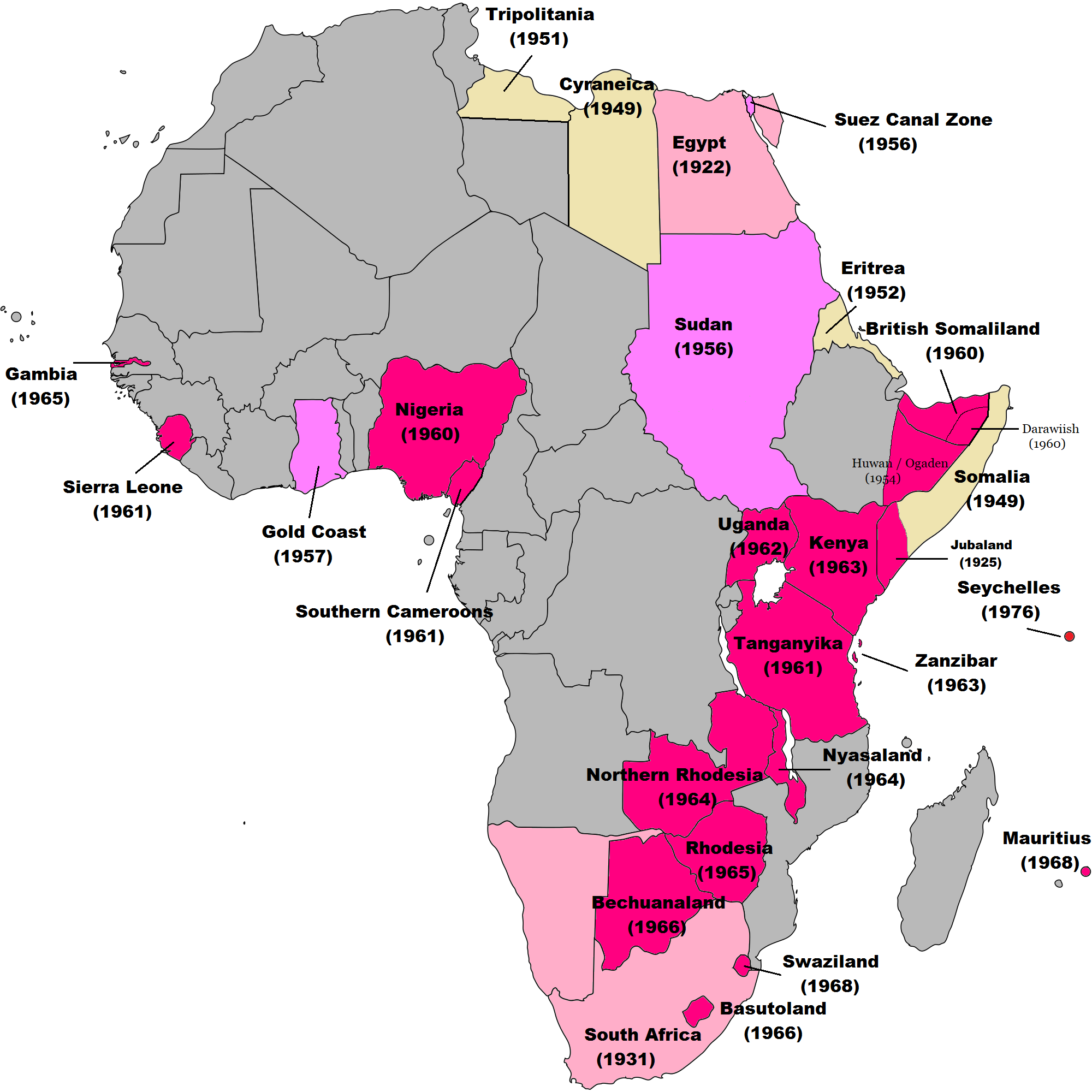

decolonisation

Decolonization or decolonisation is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. Some scholars of decolonization focus especially on independence m ...

movement, in which Britain granted independence to most territories of the empire. The

Suez Crisis of 1956 confirmed Britain's decline as a global power, and the

transfer of Hong Kong to China on 1 July 1997 marked for many the end of the British Empire.

Fourteen

overseas territories remain under British sovereignty. After independence, many former British colonies, along with most of the dominions, joined the

Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the ...

, a free association of independent states. Fifteen of these, including the United Kingdom,

retain a common monarch, currently

King Charles III

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms. He was the longest-serving heir apparent and Prince of Wales and, at age 73, became the oldest person to a ...

.

Origins (1497–1583)

The foundations of the British Empire were laid when

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

and

Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a Anglo-Scottish border, border with England to the southeast ...

were separate kingdoms. In 1496, King

Henry VII of England

Henry VII (28 January 1457 – 21 April 1509) was King of England and Lord of Ireland from his seizure of the crown on 22 August 1485 until his death in 1509. He was the first monarch of the House of Tudor.

Henry's mother, Margaret Beauf ...

, following the successes of

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

and

Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

in overseas exploration, commissioned

John Cabot to lead an expedition to discover a

northwest passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The eastern route along the Arc ...

to Asia via the North Atlantic. Cabot sailed in 1497, five years after the

first voyage of Christopher Columbus, and made landfall on the coast of

Newfoundland. He believed he had reached Asia, and there was no attempt to found a colony. Cabot led another voyage to the Americas the following year but he did not return from this voyage and it is unknown what happened to his ships.

No further attempts to establish English colonies in the Americas were made until well into the

reign of Queen Elizabeth I, during the last decades of the 16th century. In the meantime,

Henry VIII's 1533

Statute in Restraint of Appeals had declared "that this realm of England is an Empire". The

Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and ...

turned

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

and

Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

Spain into implacable enemies. In 1562, Elizabeth I encouraged the

privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

s

John Hawkins

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second ...

and

Francis Drake to engage in

slave-raiding attacks against Spanish and Portuguese ships off the coast of

West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, M ...

with the aim of establishing an

Atlantic slave trade. This effort was rebuffed and later, as the

Anglo-Spanish Wars intensified,

Elizabeth I gave her blessing to further privateering raids against Spanish ports in the Americas and shipping that was returning across the Atlantic,

laden with treasure from the

New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

. At the same time, influential writers such as

Richard Hakluyt and

John Dee (who was the first to use the term "British Empire") were beginning to press for the establishment of England's own empire. By this time, Spain had become the dominant power in the Americas and was exploring the Pacific Ocean, Portugal had established trading posts and forts from the coasts of

Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

and

Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

to

China, and France had begun to settle the

Saint Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (french: Fleuve Saint-Laurent, ) is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a (roughly) northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connectin ...

area, later to become

New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

.

Although England tended to trail behind Portugal, Spain, and France in establishing overseas colonies, it carried out its first modern colonisation, referred to as the

Ulster Plantation

The Plantation of Ulster ( gle, Plandáil Uladh; Ulster-Scots: ''Plantin o Ulstèr'') was the organised colonisation (''plantation'') of Ulstera province of Irelandby people from Great Britain during the reign of King James I. Most of the set ...

, in 16th century

Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

by settling

English Protestants

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

in

Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kin ...

. England had already colonised part of the country following the

Norman invasion of Ireland

The Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland took place during the late 12th century, when Anglo-Normans gradually conquered and acquired large swathes of land from the Irish, over which the kings of England then claimed sovereignty, all allegedly san ...

in 1169. Several people who helped establish the Ulster Plantations later played a part in the early colonisation of North America, particularly a group known as the

West Country Men

The West Country Men were a group of individuals in Elizabethan England who advocated the

English colonisation of Ireland, attacks on the Spanish Empire and other overseas colonial expansion. The group included Humphrey Gilbert, Walter Raleigh, ...

.

English overseas possessions (1583–1707)

In 1578, Elizabeth I granted a patent to

Humphrey Gilbert

Sir Humphrey Gilbert (c. 1539 – 9 September 1583) was an English adventurer, explorer, member of parliament and soldier who served during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I and was a pioneer of the English colonial empire in North America ...

for discovery and overseas exploration. That year, Gilbert sailed for the

Caribbean with the intention of engaging in

piracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

and establishing a colony in North America, but the expedition was aborted before it had crossed the Atlantic. In 1583, he embarked on a second attempt. On this occasion, he formally claimed the harbour of the island of Newfoundland, although no settlers were left behind. Gilbert did not survive the return journey to England and was succeeded by his half-brother,

Walter Raleigh

Sir Walter Raleigh (; – 29 October 1618) was an English statesman, soldier, writer and explorer. One of the most notable figures of the Elizabethan era, he played a leading part in English colonisation of North America, suppressed rebelli ...

, who was granted his own patent by Elizabeth in 1584. Later that year, Raleigh founded the

Roanoke Colony on the coast of present-day

North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and ...

, but lack of supplies caused the colony to fail.

In 1603,

James VI of Scotland ascended (as James I) to the English throne and in 1604 negotiated the

Treaty of London, ending hostilities with Spain. Now at peace with its main rival, English attention shifted from preying on other nations' colonial infrastructures to the business of establishing its own overseas colonies. The British Empire began to take shape during the early 17th century, with the

English settlement

''English Settlement'' is the fifth studio album and first double album by the English rock band XTC, released 12 February 1982 on Virgin Records. It marked a turn towards the more pastoral pop songs that would dominate later XTC releases, wit ...

of North America and the smaller islands of the Caribbean, and the establishment of

joint-stock companies

A joint-stock company is a business entity in which shares of the company's stock can be bought and sold by shareholders. Each shareholder owns company stock in proportion, evidenced by their shares (certificates of ownership). Shareholders are ...

, most notably the

East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and South ...

, to administer colonies and overseas trade. This period, until the loss of the

Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th cent ...

after the

American War of Independence towards the end of the 18th century, has been referred to by some historians as the "First British Empire".

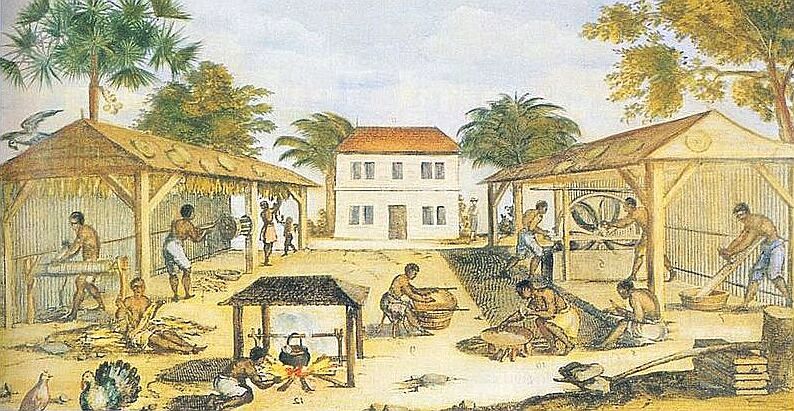

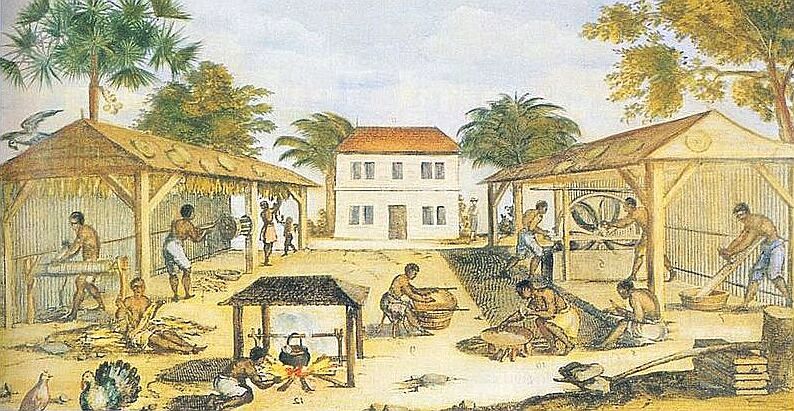

Americas, Africa and the slave trade

England's early efforts at colonisation in the Americas met with mixed success. An attempt to establish a colony in

Guiana in 1604 lasted only two years and failed in its main objective to find gold deposits. Colonies on the Caribbean islands of

St Lucia

Saint Lucia ( acf, Sent Lisi, french: Sainte-Lucie) is an island country of the West Indies in the eastern Caribbean. The island was previously called Iouanalao and later Hewanorra, names given by the native Arawaks and Caribs, two Amerindi ...

(1605) and

Grenada (1609) rapidly folded.

[ Canny, p. 221.] The first permanent English settlement in the Americas was founded in 1607 in

Jamestown by Captain

John Smith, and managed by the

Virginia Company

The Virginia Company was an English trading company chartered by King James I on 10 April 1606 with the object of colonizing the eastern coast of America. The coast was named Virginia, after Elizabeth I, and it stretched from present-day Mai ...

; the Crown took direct control of the venture in 1624, thereby founding the

Colony of Virginia.

Bermuda

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type = National song

, song = "Hail to Bermuda"

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, mapsize2 =

, map_caption2 =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name =

, es ...

was settled and claimed by England as a result of the 1609 shipwreck of the Virginia Company's

flagship, while

attempts to settle Newfoundland were largely unsuccessful. In 1620,

Plymouth was founded as a haven by

Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

religious separatists, later known as the

Pilgrim

A pilgrim (from the Latin ''peregrinus'') is a traveler (literally one who has come from afar) who is on a journey to a holy place. Typically, this is a physical journey (often on foot) to some place of special significance to the adherent of ...

s. Fleeing from

religious persecution would become the motive for many English would-be colonists to risk the arduous

trans-Atlantic voyage:

Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

was established by

English Roman Catholics

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national id ...

(1634),

Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the smallest U.S. state by area and the seventh-least populous, with slightly fewer than 1.1 million residents as of 2020, but it ...

(1636) as a colony

tolerant of all religions and Connecticut (1639) for

Congregationalists. England's North American holdings were further expanded by the annexation of the Dutch colony of

New Netherland

New Netherland ( nl, Nieuw Nederland; la, Novum Belgium or ) was a 17th-century colonial province of the Dutch Republic that was located on the east coast of what is now the United States. The claimed territories extended from the Delmarva P ...

in 1664, following the capture of

New Amsterdam, which was renamed

New York. Although less financially successful than colonies in the Caribbean, these territories had large areas of good agricultural land and attracted far greater numbers of English emigrants, who preferred their temperate climates.

The

British West Indies

The British West Indies (BWI) were colonized British territories in the West Indies: Anguilla, the Cayman Islands, Turks and Caicos Islands, Montserrat, the British Virgin Islands, Antigua and Barbuda, The Bahamas, Barbados, Dominica, Grena ...

initially provided England's most important and lucrative colonies. Settlements were successfully established in

St. Kitts (1624),

Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of the Americas, and the most easterly of the Caribbean Islands. It occupies an area of and has a population of about 287,000 (2019 estimate) ...

(1627) and

Nevis

Nevis is a small island in the Caribbean Sea that forms part of the inner arc of the Leeward Islands chain of the West Indies. Nevis and the neighbouring island of Saint Kitts constitute one country: the Federation of Saint Kitts and ...

(1628),

but struggled until the "Sugar Revolution" transformed the Caribbean economy in the mid-17th century.

Large

sugarcane plantations were first established in the 1640s on Barbados, with assistance from Dutch merchants and

Sephardic Jews

Sephardic (or Sephardi) Jews (, ; lad, Djudíos Sefardíes), also ''Sepharadim'' , Modern Hebrew: ''Sfaradim'', Tiberian: Səp̄āraddîm, also , ''Ye'hude Sepharad'', lit. "The Jews of Spain", es, Judíos sefardíes (or ), pt, Judeus sefa ...

fleeing

Portuguese Brazil

Colonial Brazil ( pt, Brasil Colonial) comprises the period from 1500, with the arrival of the Portuguese, until 1815, when Brazil was elevated to a kingdom in union with Portugal as the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves. Duri ...

. At first, sugar was grown primarily using white

indentured labour

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment, ...

, but rising costs soon led English traders to embrace the use of imported African slaves. The enormous wealth generated by slave-produced sugar made Barbados the most successful colony in the Americas, and one of the most densely populated places in the world.

This boom led to the spread of sugar cultivation across the Caribbean, financed the development of non-plantation colonies in North America, and accelerated the growth of the

Atlantic slave trade, particularly the

triangular trade

Triangular trade or triangle trade is trade between three ports or regions. Triangular trade usually evolves when a region has export commodities that are not required in the region from which its major imports come. It has been used to offset ...

of slaves, sugar and provisions between Africa, the West Indies and Europe.

To ensure that the increasingly healthy profits of colonial trade remained in English hands, Parliament

decreed

A decree is a legal proclamation, usually issued by a head of state (such as the president of a republic or a monarch), according to certain procedures (usually established in a constitution). It has the force of law. The particular term used for ...

in 1651 that only English ships would be able to ply their trade in English colonies. This led to hostilities with the

United Dutch Provinces—a series of

Anglo-Dutch Wars

The Anglo–Dutch Wars ( nl, Engels–Nederlandse Oorlogen) were a series of conflicts mainly fought between the Dutch Republic and England (later Great Britain) from mid-17th to late 18th century. The first three wars occurred in the second ...

—which would eventually strengthen England's position in the Americas at the expense of the Dutch. In 1655, England annexed the island of

Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

from the Spanish, and in 1666 succeeded in colonising the

Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to 88% of the ar ...

.

In 1670,

Charles II incorporated by royal charter the

Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC; french: Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson) is a Canadian retail business group. A fur trading business for much of its existence, HBC now owns and operates retail stores in Canada. The company's namesake business di ...

(HBC), granting it a monopoly on the

fur trade in the area known as

Rupert's Land

Rupert's Land (french: Terre de Rupert), or Prince Rupert's Land (french: Terre du Prince Rupert, link=no), was a territory in British North America which comprised the Hudson Bay drainage basin; this was further extended from Rupert's Land t ...

, which would later form a large proportion of the

Dominion of Canada. Forts and trading posts established by the HBC were frequently the subject of attacks by the French, who had established their own fur trading colony in adjacent

New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

.

[ Buckner, p. 25.]

Two years later, the

Royal African Company was granted a monopoly on the supply of slaves to the British colonies in the Caribbean. The company would transport more slaves across the Atlantic than any other, and significantly grew England's share of the trade, from 33 per cent in 1673 to 74 per cent in 1683. The removal of this monopoly between 1688 and 1712 allowed independent British slave traders to thrive, leading to a rapid escalation in the number of slaves transported. British ships carried a third of all slaves shipped across the Atlantic—approximately 3.5 million Africans—and dominated global slave trading in the 25 years preceding its abolition by Parliament in 1807 (see ). To facilitate the shipment of slaves, forts were established on the coast of West Africa, such as

James Island,

Accra and

Bunce Island

Bunce Island (also spelled "Bence," "Bense," or "Bance" at different periods) is an island in the Sierra Leone River. It is situated in Freetown Harbour, the estuary of the Rokel River and Port Loko Creek, about upriver from Sierra Leone's capi ...

. In the British Caribbean, the percentage of the population of African descent rose from 25 per cent in 1650 to around 80 per cent in 1780, and in the Thirteen Colonies from 10 per cent to 40 per cent over the same period (the majority in the southern colonies). The transatlantic slave trade played a pervasive role in British economic life, and became a major economic mainstay for western port cities. Ships registered in

Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

,

Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a populat ...

and

London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

were responsible for the bulk of British slave trading. For the transported, harsh and unhygienic conditions on the slaving ships and poor diets meant that the average

mortality rate

Mortality rate, or death rate, is a measure of the number of deaths (in general, or due to a specific cause) in a particular population, scaled to the size of that population, per unit of time. Mortality rate is typically expressed in units of d ...

during the

Middle Passage was one in seven.

Rivalry with other European empires

At the end of the 16th century, England and the

Dutch Empire began to challenge the

Portuguese Empire

The Portuguese Empire ( pt, Império Português), also known as the Portuguese Overseas (''Ultramar Português'') or the Portuguese Colonial Empire (''Império Colonial Português''), was composed of the overseas colonies, factories, and the ...

's monopoly of trade with Asia, forming private joint-stock companies to finance the voyages—the English, later British, East India Company and the

Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock ...

, chartered in 1600 and 1602 respectively. The primary aim of these companies was to tap into the lucrative

spice trade, an effort focused mainly on two regions: the

East Indies archipelago, and an important hub in the trade network, India. There, they competed for trade supremacy with Portugal and with each other. Although England eclipsed the Netherlands as a colonial power, in the short term the Netherlands' more advanced financial system and the three

Anglo-Dutch Wars

The Anglo–Dutch Wars ( nl, Engels–Nederlandse Oorlogen) were a series of conflicts mainly fought between the Dutch Republic and England (later Great Britain) from mid-17th to late 18th century. The first three wars occurred in the second ...

of the 17th century left it with a stronger position in Asia. Hostilities ceased after the

Glorious Revolution of 1688 when the Dutch

William of Orange ascended the English throne, bringing peace between the

Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands (Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiography ...

and England. A deal between the two nations left the

spice trade of the

East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies), is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The Indies refers to various lands in the East or the Eastern hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainlands found in and around ...

archipelago to the Netherlands and the

textiles industry of India to England, but textiles soon overtook spices in terms of profitability.

Peace between England and the Netherlands in 1688 meant the two countries entered the

Nine Years' War as allies, but the conflict—waged in Europe and overseas between France, Spain and the Anglo-Dutch alliance—left the English a stronger colonial power than the Dutch, who were forced to devote a larger proportion of their

military budget

A military budget (or military expenditure), also known as a defense budget, is the amount of financial resources dedicated by a state to raising and maintaining an armed forces or other methods essential for defense purposes.

Financing militar ...

to the costly land war in Europe. The death of

Charles II of Spain

Charles II of Spain (''Spanish: Carlos II,'' 6 November 1661 – 1 November 1700), known as the Bewitched (''Spanish: El Hechizado''), was the last Habsburg ruler of the Spanish Empire. Best remembered for his physical disabilities and the War ...

in 1700 and his bequeathal of Spain and its colonial empire to

Philip V of Spain

Philip V ( es, Felipe; 19 December 1683 – 9 July 1746) was King of Spain from 1 November 1700 to 14 January 1724, and again from 6 September 1724 to his death in 1746. His total reign of 45 years is the longest in the history of the Spanish mon ...

, a grandson of the

King of France, raised the prospect of the unification of France, Spain and their respective colonies, an unacceptable state of affairs for England and the other powers of Europe.

In 1701, England, Portugal and the Netherlands sided with the

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

against Spain and France in the

War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phil ...

, which lasted for thirteen years.

Scottish attempt to expand overseas

In 1695, the

Parliament of Scotland

The Parliament of Scotland ( sco, Pairlament o Scotland; gd, Pàrlamaid na h-Alba) was the legislature of the Kingdom of Scotland from the 13th century until 1707. The parliament evolved during the early 13th century from the king's council o ...

granted a charter to the

Company of Scotland, which established a settlement in 1698 on the

Isthmus of Panama. Besieged by neighbouring

Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

colonists of

New Granada, and affected by

malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

, the colony was abandoned two years later. The

Darien scheme

The Darien scheme was an unsuccessful attempt, backed largely by investors of the Kingdom of Scotland, to gain wealth and influence by establishing ''New Caledonia'', a colony on the Isthmus of Panama, in the late 1690s. The plan was for the co ...

was a financial disaster for Scotland: a quarter of Scottish capital was lost in the enterprise. The episode had major political consequences, helping to persuade the government of the

Kingdom of Scotland

The Kingdom of Scotland (; , ) was a sovereign state in northwest Europe traditionally said to have been founded in 843. Its territories expanded and shrank, but it came to occupy the northern third of the island of Great Britain, sharing a l ...

of the merits of turning the

personal union

A personal union is the combination of two or more states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, would involve the constituent states being to some extent interlink ...

with

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

into a political and economic one under the

Kingdom of Great Britain

The Kingdom of Great Britain (officially Great Britain) was a Sovereign state, sovereign country in Western Europe from 1 May 1707 to the end of 31 December 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of ...

established by the

Acts of Union 1707.

"First" British Empire (1707–1783)

The 18th century saw the

newly united Great Britain rise to be the world's dominant colonial power, with France becoming its main rival on the imperial stage. Great Britain, Portugal, the Netherlands, and the Holy Roman Empire continued the War of the Spanish Succession, which lasted until 1714 and was concluded by the

Treaty of Utrecht

The Peace of Utrecht was a series of peace treaties signed by the belligerents in the War of the Spanish Succession, in the Dutch city of Utrecht between April 1713 and February 1715. The war involved three contenders for the vacant throne ...

.

Philip V of Spain

Philip V ( es, Felipe; 19 December 1683 – 9 July 1746) was King of Spain from 1 November 1700 to 14 January 1724, and again from 6 September 1724 to his death in 1746. His total reign of 45 years is the longest in the history of the Spanish mon ...

renounced his and his descendants' claim to the French throne, and Spain lost its empire in Europe.

[ Shennan, pp. 11–17.] The British Empire was territorially enlarged: from France, Britain gained

Newfoundland and

Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the The Maritimes, Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17t ...

, and from Spain

Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

and

Menorca

Menorca or Minorca (from la, Insula Minor, , smaller island, later ''Minorica'') is one of the Balearic Islands located in the Mediterranean Sea belonging to Spain. Its name derives from its size, contrasting it with nearby Majorca. Its capi ...

. Gibraltar became a

critical naval base and allowed Britain to control the

Atlantic entry and exit point to the

Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western Europe, Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa ...

. Spain ceded the rights to the lucrative ''

asiento

The () was a monopoly contract between the Spanish Crown and various merchants for the right to provide African slaves to colonies in the Spanish Americas. The Spanish Empire rarely engaged in the trans-Atlantic slave trade directly from Afri ...

'' (permission to sell African slaves in

Spanish America

Spanish America refers to the Spanish territories in the Americas during the Spanish colonization of the Americas. The term "Spanish America" was specifically used during the territories' imperial era between 15th and 19th centuries. To the e ...

) to Britain. With the outbreak of the Anglo-Spanish

War of Jenkins' Ear

The War of Jenkins' Ear, or , was a conflict lasting from 1739 to 1748 between Britain and the Spanish Empire. The majority of the fighting took place in New Granada and the Caribbean Sea, with major operations largely ended by 1742. It is con ...

in 1739, Spanish privateers attacked British merchant shipping along the

Triangle Trade

Triangular trade or triangle trade is trade between three ports or regions. Triangular trade usually evolves when a region has export commodities that are not required in the region from which its major imports come. It has been used to offset t ...

routes. In 1746, the Spanish and British began peace talks, with the King of Spain agreeing to stop all attacks on British shipping; however, in the

Treaty of Madrid Britain lost its slave-trading rights in

Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived f ...

.

In the East Indies, British and Dutch merchants continued to compete in spices and textiles. With textiles becoming the larger trade, by 1720, in terms of sales, the British company had overtaken the Dutch. During the middle decades of the 18th century, there were

several outbreaks of military conflict on the

Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a list of the physiographic regions of the world, physiographical region in United Nations geoscheme for Asia#Southern Asia, Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian O ...

, as the English East India Company and its

French counterpart, struggled alongside local rulers to fill the vacuum that had been left by the decline of the

Mughal Empire

The Mughal Empire was an early-modern empire that controlled much of South Asia between the 16th and 19th centuries. Quote: "Although the first two Timurid emperors and many of their noblemen were recent migrants to the subcontinent, the d ...

. The

Battle of Plassey in 1757, in which the British defeated the

Nawab of Bengal and his French allies, left the British East India Company in control of

Bengal

Bengal ( ; bn, বাংলা/বঙ্গ, translit=Bānglā/Bôngô, ) is a geopolitical, cultural and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, predom ...

and as the major military and political power in India. France was left control of its

enclaves

An enclave is a territory (or a small territory apart of a larger one) that is entirely surrounded by the territory of one other state or entity. Enclaves may also exist within territorial waters. ''Enclave'' is sometimes used improperly to deno ...

but with military restrictions and an obligation to support British

client state

A client state, in international relations, is a state that is economically, politically, and/or militarily subordinate to another more powerful state (called the "controlling state"). A client state may variously be described as satellite state, ...

s, ending French hopes of controlling India. In the following decades the British East India Company gradually increased the size of the territories under its control, either ruling directly or via local rulers under the threat of force from the

Presidency Armies

The presidency armies were the armies of the three presidencies of the East India Company's rule in India, later the forces of the British Crown in India, composed primarily of Indian sepoys. The presidency armies were named after the presiden ...

, the vast majority of which was composed of Indian

sepoys, led by British officers. The British and French struggles in India became but one theatre of the global

Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (175 ...

(1756–1763) involving France, Britain, and the other major European powers.

The signing of the

Treaty of Paris of 1763

The Treaty of Paris, also known as the Treaty of 1763, was signed on 10 February 1763 by the kingdoms of Great Britain, France and Spain, with Portugal in agreement, after Great Britain and Prussia's victory over France and Spain during the S ...

had important consequences for the future of the British Empire. In North America, France's future as a colonial power effectively ended with the recognition of British claims to Rupert's Land,

and the

ceding of New France to Britain (leaving a sizeable

French-speaking population under British control) and

Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

to Spain. Spain ceded Florida to Britain. Along with its victory over France in India, the Seven Years' War therefore left Britain as the world's most powerful

maritime power

A maritime power is a nation with a very strong navy, which often is also a great power, or at least a regional power. A maritime power is able to easily control their coast, and exert influence upon both nearby and far countries. A nation that dom ...

.

[ Pagden, p. 91.]

Loss of the Thirteen American Colonies

During the 1760s and early 1770s, relations between the Thirteen Colonies and Britain became increasingly strained, primarily because of resentment of the British Parliament's attempts to govern and tax American colonists without their consent. This was summarised at the time by the slogan "

No taxation without representation

"No taxation without representation" is a political slogan that originated in the American Revolution, and which expressed one of the primary grievances of the American colonists for Great Britain. In short, many colonists believed that as they ...

", a perceived violation of the guaranteed

Rights of Englishmen

The "rights of Englishmen" are the traditional rights of English subjects and later English-speaking subjects of the British Crown. In the 18th century, some of the colonists who objected to British rule in the thirteen British North American ...

. The

American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

began with a rejection of Parliamentary authority and moves towards self-government. In response, Britain sent troops to reimpose direct rule, leading to the outbreak of war in 1775. The following year, in 1776, the

Second Continental Congress issued the

Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of th ...

proclaiming the colonies' sovereignty from the British Empire as the new

United States of America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territo ...

. The entry of

French and

Spanish forces into the war tipped the military balance in the Americans' favour and after a decisive defeat at

Yorktown in 1781, Britain began negotiating peace terms. American independence was acknowledged at the

Peace of Paris in 1783.

The loss of such a large portion of

British America, at the time Britain's most populous overseas possession, is seen by some historians as the event defining the transition between the "first" and "second" empires, in which Britain shifted its attention away from the Americas to Asia, the Pacific and later Africa.

Adam Smith's ''

Wealth of Nations

''An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations'', generally referred to by its shortened title ''The Wealth of Nations'', is the ''magnum opus'' of the Scottish economist and moral philosopher Adam Smith. First published in 1 ...

'', published in 1776, had argued that colonies were redundant, and that

free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econ ...

should replace the old

mercantilist

Mercantilism is an economic policy that is designed to maximize the exports and minimize the imports for an economy. It promotes imperialism, colonialism, tariffs and subsidies on traded goods to achieve that goal. The policy aims to reduce ...

policies that had characterised the first period of colonial expansion, dating back to the

protectionism

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulatio ...

of Spain and Portugal.

The growth of trade between the newly independent

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

and Britain after 1783 seemed to confirm Smith's view that political control was not necessary for economic success.

The war to the south influenced British policy in Canada, where between 40,000 and 100,000 defeated

Loyalists

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cro ...

had migrated from the new United States following independence. The 14,000 Loyalists who went to the

Saint John and

Saint Croix river valleys, then part of

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

, felt too far removed from the provincial government in

Halifax, so London split off

New Brunswick

New Brunswick (french: Nouveau-Brunswick, , locally ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. It is the only province with both English and ...

as a separate colony in 1784. The

Constitutional Act of 1791

The Clergy Endowments (Canada) Act 1791, commonly known as the Constitutional Act 1791 (), was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain which passed under George III. The current short title has been in use since 1896.

History

The act refor ...

created the provinces of

Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada (french: link=no, province du Haut-Canada) was a part of British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North America, formerly part of th ...

(mainly

English speaking

English is a West Germanic language of the Indo-European language family, with its earliest forms spoken by the inhabitants of early medieval England. It is named after the Angles, one of the ancient Germanic peoples that migrated to the i ...

) and

Lower Canada

The Province of Lower Canada (french: province du Bas-Canada) was a British colony on the lower Saint Lawrence River and the shores of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence (1791–1841). It covered the southern portion of the current Province of Quebec an ...

(mainly

French-speaking) to defuse tensions between the French and British communities, and implemented governmental systems similar to those employed in Britain, with the intention of asserting imperial authority and not allowing the sort of popular control of government that was perceived to have led to the American Revolution.

Tensions between Britain and the United States escalated again during the

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

, as Britain tried to cut off American trade with France and boarded American ships to

impress

The Independent Monitor for the Press (IMPRESS) is an independent press regulator in the UK. It was the first to be recognised by the Press Recognition Panel. Unlike the Independent Press Standards Organisation (IPSO), IMPRESS is fully compliant ...

men into the

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

. The

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washing ...

declared war, the

War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States, United States of America and its Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom ...

, and invaded Canadian territory. In response, Britain invaded the US, but the pre-war boundaries were reaffirmed by the 1814

Treaty of Ghent

The Treaty of Ghent () was the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812 between the United States and the United Kingdom. It took effect in February 1815. Both sides signed it on December 24, 1814, in the city of Ghent, United Netherlands (now in ...

, ensuring Canada's future would be separate from that of the United States.

Rise of the "Second" British Empire (1783–1815)

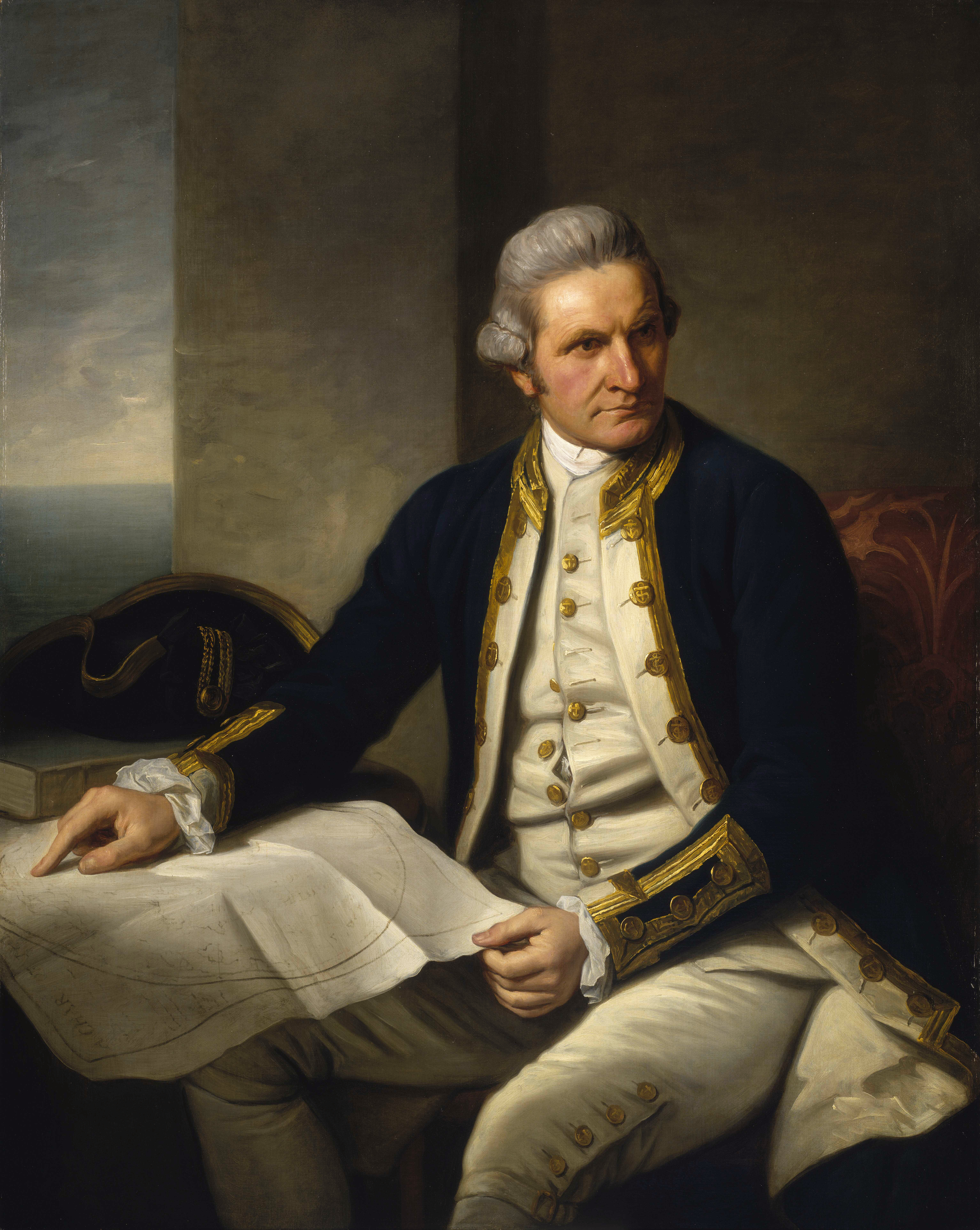

Exploration of the Pacific

Since 1718,

transportation

Transport (in British English), or transportation (in American English), is the intentional movement of humans, animals, and goods from one location to another. Modes of transport include air, land (rail and road), water, cable, pipeline, ...

to the American colonies had been a penalty for various offences in Britain, with approximately one thousand convicts transported per year. Forced to find an alternative location after the loss of the Thirteen Colonies in 1783, the British government turned to

Australia. The

coast of Australia had been discovered for Europeans by the Dutch

in 1606,

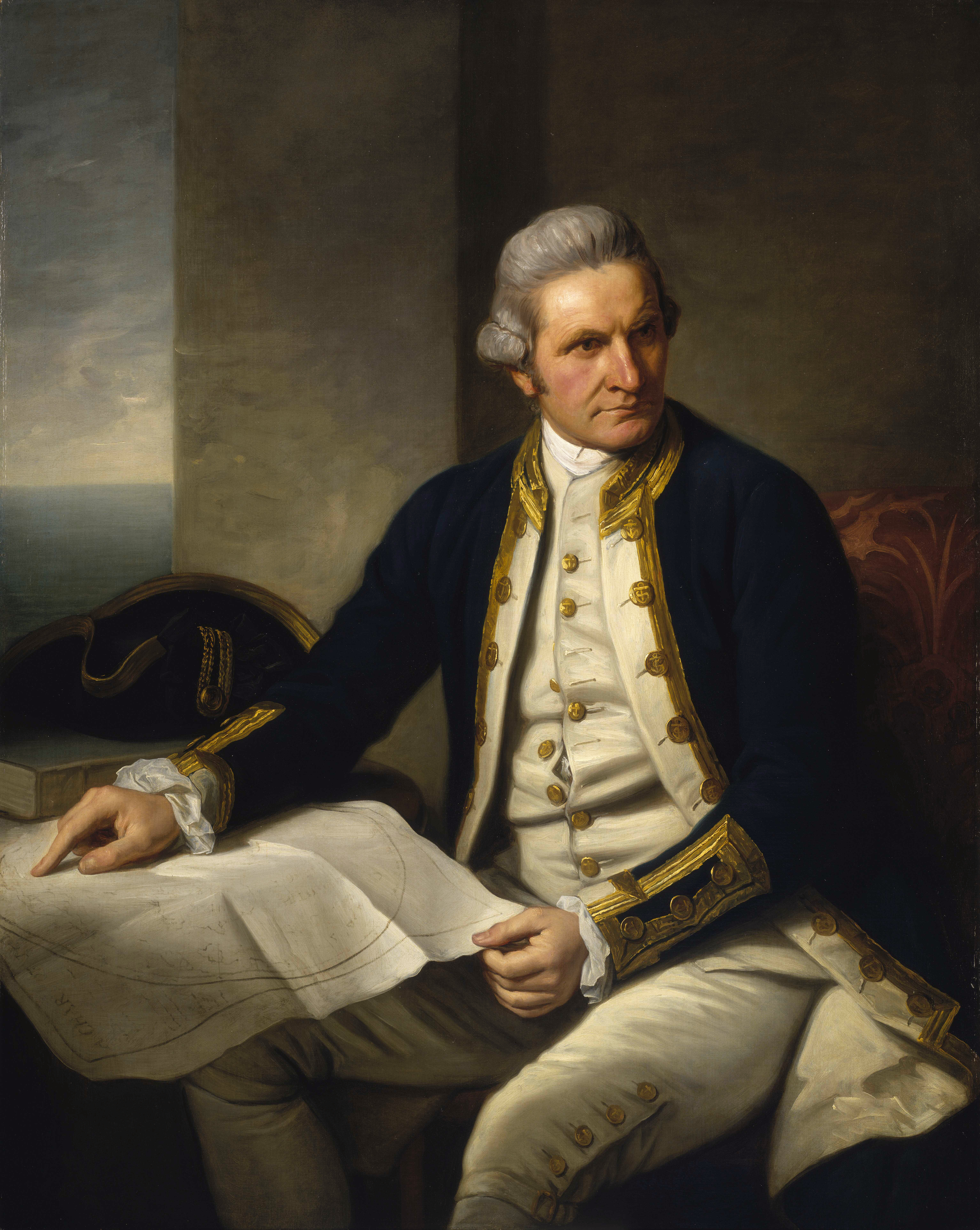

[ Mulligan & Hill, pp. 20–23.] but there was no attempt to colonise it. In 1770

James Cook charted the eastern coast while on a scientific

voyage

Voyage(s) or The Voyage may refer to:

Literature

*''Voyage : A Novel of 1896'', Sterling Hayden

* ''Voyage'' (novel), a 1996 science fiction novel by Stephen Baxter

*''The Voyage'', Murray Bail

* "The Voyage" (short story), a 1921 story by ...

, claimed the continent for Britain, and named it

New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

. In 1778,

Joseph Banks, Cook's

botanist on the voyage, presented evidence to the government on the suitability of

Botany Bay

Botany Bay (Dharawal: ''Kamay''), an open oceanic embayment, is located in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, south of the Sydney central business district. Its source is the confluence of the Georges River at Taren Point and the Cook ...

for the establishment of a

penal settlement

A penal colony or exile colony is a settlement used to exile prisoners and separate them from the general population by placing them in a remote location, often an island or distant colonial territory. Although the term can be used to refer to ...

, and in 1787 the first shipment of

convicts

A convict is "a person found guilty of a crime and sentenced by a court" or "a person serving a sentence in prison". Convicts are often also known as "prisoners" or "inmates" or by the slang term "con", while a common label for former convict ...

set sail, arriving in 1788. Unusually, Australia was claimed through proclamation.

Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians or Australian First Nations are people with familial heritage from, and membership in, the ethnic groups that lived in Australia before British colonisation. They consist of two distinct groups: the Aboriginal peoples ...

were considered too uncivilised to require treaties, and colonisation brought disease and violence that together with the deliberate dispossession of land and culture were devastating to these peoples. Britain continued to transport convicts to New South Wales until 1840, to

Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

until 1853 and to

Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to th ...

until 1868. The Australian colonies became profitable exporters of wool and gold, mainly because of the

Victorian gold rush

The Victorian gold rush was a period in the history of Victoria, Australia approximately between 1851 and the late 1860s. It led to a period of extreme prosperity for the Australian colony, and an influx of population growth and financial capit ...

, making its capital

Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

for a time the richest city in the world.

During his voyage, Cook visited

New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

, known to Europeans due to the 1642 voyage of the Dutch explorer,

Abel Tasman

Abel Janszoon Tasman (; 160310 October 1659) was a Dutch seafarer, explorer, and merchant, best known for his voyages of 1642 and 1644 in the service of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). He was the first known European explorer to reach New ...

. Cook claimed both the

North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north ...

and the

South islands for the British crown in 1769 and 1770 respectively. Initially, interaction between the indigenous

Maori population and

European settlers

European, or Europeans, or Europeneans, may refer to:

In general

* ''European'', an adjective referring to something of, from, or related to Europe

** Ethnic groups in Europe

** Demographics of Europe

** European cuisine, the cuisines of Europe ...

was limited to the trading of goods. European settlement increased through the early decades of the 19th century, with many trading stations being established, especially in the North. In 1839, the

New Zealand Company

The New Zealand Company, chartered in the United Kingdom, was a company that existed in the first half of the 19th century on a business model focused on the systematic colonisation of New Zealand. The company was formed to carry out the principl ...

announced plans to buy large tracts of land and establish colonies in New Zealand. On 6 February 1840, Captain

William Hobson

Captain William Hobson (26 September 1792 – 10 September 1842) was a British Royal Navy officer who served as the first Governor of New Zealand. He was a co-author of the Treaty of Waitangi.

Hobson was dispatched from London in July 1 ...

and around 40 Maori chiefs signed the

Treaty of Waitangi

The Treaty of Waitangi ( mi, Te Tiriti o Waitangi) is a document of central importance to the History of New Zealand, history, to the political constitution of the state, and to the national mythos of New Zealand. It has played a major role in ...

which is considered to be New Zealand's founding document despite differing interpretations of the

Maori and

English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

versions of the text being the cause of ongoing dispute.

The British also expanded their mercantile interests in the North Pacific. Spain and Britain had become rivals in the area, culminating in the

Nootka Crisis

The Nootka Crisis, also known as the Spanish Armament, was an international incident and political dispute between the Nuu-chah-nulth Nation, the Spanish Empire, the Kingdom of Great Britain, and the fledgling United States of America triggered b ...

in 1789. Both sides mobilised for war, but when France refused to support Spain it was forced to back down, leading to the

Nootka Convention

The Nootka Sound Conventions were a series of three agreements between the Kingdom of Spain and the Kingdom of Great Britain, signed in the 1790s, which averted a war between the two countries over overlapping claims to portions of the Pacific No ...

. The outcome was a humiliation for Spain, which practically renounced all sovereignty on the North Pacific coast. This opened the way to British expansion in the area, and a number of expeditions took place; firstly a

naval expedition led by

George Vancouver which explored the inlets around the Pacific North West, particularly around

Vancouver Island

Vancouver Island is an island in the northeastern Pacific Ocean and part of the Canadian province of British Columbia. The island is in length, in width at its widest point, and in total area, while are of land. The island is the largest by ...

.

On land, expeditions sought to discover a river route to the Pacific for the extension of the

North American fur trade.

Alexander Mackenzie of the

North West Company led the first, starting out in 1792, and a year a later he became the first European to reach the Pacific overland north of the

Rio Grande, reaching the ocean near present-day

Bella Coola. This preceded the

Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery Expedition, was the United States expedition to cross the newly acquired western portion of the country after the Louisiana Purchase. The Corps of Discovery was a select gr ...

by twelve years. Shortly thereafter, Mackenzie's companion,

John Finlay, founded the first permanent European settlement in

British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, ...

,

Fort St. John. The North West Company sought further exploration and backed expeditions by

David Thompson, starting in 1797, and later by

Simon Fraser. These pushed into the wilderness territories of the

Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico ...

and

Interior Plateau

The Interior Plateau comprises a large region of the Interior of British Columbia, and lies between the Cariboo and Monashee Mountains on the east, and the Hazelton Mountains, Coast Mountains and Cascade Range on the west.''Landforms of British C ...

to the

Strait of Georgia on the Pacific Coast, expanding

British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland, then further south at Roanoke and Jamestow ...

westward.

Wars with France

Britain was challenged again by France under Napoleon, in a struggle that, unlike previous wars, represented a contest of ideologies between the two nations. It was not only Britain's position on the world stage that was at risk: Napoleon threatened to invade Britain itself, just as his armies had overrun many countries of

continental Europe.

The Napoleonic Wars were therefore ones in which Britain invested large amounts of capital and resources to win. French ports were blockaded by the

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

, which won a decisive victory over a

French Imperial Navy

The French Imperial Navy () was the name given to the French Navy during the period of the Napoleonic Wars, and subsequently during the reign of Napoleon Bonaparte. The first use of the title 'Imperial Navy' was in 1804, following the Coronation ...

-

Spanish Navy

The Spanish Navy or officially, the Armada, is the maritime branch of the Spanish Armed Forces and one of the oldest active naval forces in the world. The Spanish Navy was responsible for a number of major historic achievements in navigation, ...

fleet at the

Battle of Trafalgar

The Battle of Trafalgar (21 October 1805) was a naval engagement between the British Royal Navy and the combined fleets of the French and Spanish Navies during the War of the Third Coalition (August–December 1805) of the Napoleonic Wars (180 ...