Book of Leviticus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

translations:

The book of Leviticus (, from grc, Λευιτικόν, ; he, וַיִּקְרָא, , "And He called") is the third book of the

] called."

Chapters 1–5 describe the various sacrifices from the sacrificers' point of view, although the priests are essential for handling the blood. Chapters 6–7 go over much the same ground, but from the point of view of the priest, who, as the one actually carrying out the sacrifice and dividing the "portions", needs to know how to do it. Sacrifices are between God, the priest, and the offerers, although in some cases the entire sacrifice is a single portion to God—i.e., burnt to ashes.

Chapters 8–10 describe how

Chapters 1–5 describe the various sacrifices from the sacrificers' point of view, although the priests are essential for handling the blood. Chapters 6–7 go over much the same ground, but from the point of view of the priest, who, as the one actually carrying out the sacrifice and dividing the "portions", needs to know how to do it. Sacrifices are between God, the priest, and the offerers, although in some cases the entire sacrifice is a single portion to God—i.e., burnt to ashes.

Chapters 8–10 describe how

Through sacrifice, the priest "makes atonement" for sin and the offeror receives forgiveness (but only if Yahweh accepts the sacrifice). Atonement rituals involve the pouring or sprinkling of blood as the symbol of the life of the victim: the blood has the power to wipe out or absorb the sin.Houston, p. 107 The two-part division of the book structurally reflects the role of atonement: chapters 1–16 call for the establishment of the institution for atonement, and chapters 17–27 call for the life of the atoned community in holiness.

Through sacrifice, the priest "makes atonement" for sin and the offeror receives forgiveness (but only if Yahweh accepts the sacrifice). Atonement rituals involve the pouring or sprinkling of blood as the symbol of the life of the victim: the blood has the power to wipe out or absorb the sin.Houston, p. 107 The two-part division of the book structurally reflects the role of atonement: chapters 1–16 call for the establishment of the institution for atonement, and chapters 17–27 call for the life of the atoned community in holiness.

Leviticus, as part of the Torah, became the law book of Jerusalem's

Leviticus, as part of the Torah, became the law book of Jerusalem's

For detailed contents, see:

* ''

For detailed contents, see:

* ''

Leviticus

at Bible gateway

Leviticus at Mechon-Mamre

(Jewish Publication Society translation) *

Leviticus (The Living Torah)

Rabbi

Vayikra–Levitichius (Judaica Press)

translation ith_Rashi's_commentary.html"_;"title="Rashi.html"_;"title="ith_Rashi">ith_Rashi's_commentary">Rashi.html"_;"title="ith_Rashi">ith_Rashi's_commentaryat_Chabad.org *

ויקרא__''Vayikra''–Leviticus

(

ויקרא ''Vayikra''–Leviticus

(Hebrew language">Hebrew Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

–English at Mechon-Mamre.org)

* Christianity">Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...Torah

The Torah (; hbo, ''Tōrā'', "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In that sense, Torah means the ...

(the Pentateuch) and of the Old Testament, also known as the Third Book of Moses. Scholars generally agree that it developed over a long period of time, reaching its present form during the Persian Period

Yehud, also known as Yehud Medinata or Yehud Medinta (), was an administrative province of the Achaemenid Persian Empire in the region of Judea that functioned as a self-governing region under its local Jewish population. The province was a part ...

, from 538–332 BC.

Most of its chapters (1–7, 11–27) consist of Yahweh

Yahweh *''Yahwe'', was the national god of ancient Israel and Judah. The origins of his worship reach at least to the early Iron Age, and likely to the Late Bronze Age if not somewhat earlier, and in the oldest biblical literature he poss ...

s' speeches to Moses

Moses hbo, מֹשֶׁה, Mōše; also known as Moshe or Moshe Rabbeinu (Mishnaic Hebrew: מֹשֶׁה רַבֵּינוּ, ); syr, ܡܘܫܐ, Mūše; ar, موسى, Mūsā; grc, Mωϋσῆς, Mōÿsēs () is considered the most important pro ...

, which Yahweh tells Moses to repeat to the Israelites. This takes place within the story of the Israelites' Exodus

Exodus or the Exodus may refer to:

Religion

* Book of Exodus, second book of the Hebrew Torah and the Christian Bible

* The Exodus, the biblical story of the migration of the ancient Israelites from Egypt into Canaan

Historical events

* Ex ...

after they escaped Egypt and reached Mount Sinai

Mount Sinai ( he , הר סיני ''Har Sinai''; Aramaic: ܛܘܪܐ ܕܣܝܢܝ ''Ṭūrāʾ Dsyny''), traditionally known as Jabal Musa ( ar, جَبَل مُوسَىٰ, translation: Mount Moses), is a mountain on the Sinai Peninsula of Egypt. It is ...

(Exodus 19:1). The Book of Exodus

The Book of Exodus (from grc, Ἔξοδος, translit=Éxodos; he, שְׁמוֹת ''Šəmōṯ'', "Names") is the second book of the Bible. It narrates the story of the Exodus, in which the Israelites leave slavery in Biblical Egypt through ...

narrates how Moses led the Israelites in building the Tabernacle

According to the Hebrew Bible, the tabernacle ( he, מִשְׁכַּן, mīškān, residence, dwelling place), also known as the Tent of the Congregation ( he, link=no, אֹהֶל מוֹעֵד, ’ōhel mō‘ēḏ, also Tent of Meeting, etc.), ...

(Exodus 35–40) with God's instructions (Exodus 25–31). In Leviticus, God tells the Israelites and their priests, Aaron and his sons, how to make offerings in the Tabernacle and how to conduct themselves while camped around the holy tent sanctuary. Leviticus takes place during the month or month-and-a-half between the completion of the Tabernacle (Exodus 40:17) and the Israelites' departure from Sinai (Numbers 1:1, 10:11).

The instructions of Leviticus emphasize ritual, legal, and moral practices rather than beliefs. Nevertheless, they reflect the world view of the creation story in Genesis 1 that God wishes to live with humans. The book teaches that faithful performance of the sanctuary rituals can make that possible, so long as the people avoid sin

In a religious context, sin is a transgression against divine law. Each culture has its own interpretation of what it means to commit a sin. While sins are generally considered actions, any thought, word, or act considered immoral, selfish, s ...

and impurity whenever possible. The rituals, especially the sin and guilt offerings, provide the means to gain forgiveness for sins (Leviticus 4–5) and purification from impurities (Leviticus 11–16) so that God can continue to live in the Tabernacle in the midst of the people.

Name

The English name Leviticus comes from the Latin , which is in turn from the grc, Λευιτικόν (), referring to the priestly tribe of the Israelites, "Levi

Levi (; ) was, according to the Book of Genesis, the third of the six sons of Jacob and Leah (Jacob's third son), and the founder of the Israelite Tribe of Levi (the Levites, including the Kohanim) and the great-grandfather of Aaron, Moses and ...

". The Greek expression is in turn a variant of the rabbi

A rabbi () is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi – known as ''semikha'' – following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form of ...

nic Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

, "law of priests", as many of its laws relate to priests.

In Hebrew the book is called ( he, וַיִּקְרָא), from the opening of the book, "And He God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

Structure

The outlines from commentaries are similar, though not identical; compare those of Wenham, Hartley, Milgrom, and Watts. *I. Laws on sacrifice (1:1–7:38) **A. Instructions for the laity on bringing offerings (1:1–6:7) ***1–5. The types of offering: burnt, cereal, peace, purification, reparation (or sin) offerings (chapters 1–5) **B. Instructions for the priests (6:1–7:38) ***1–6. The various offerings, with the addition of the priests' cereal offering (6:1–7:36) ***7. Summary (7:37–38) *II. Institution of the priesthood (8:1–10:20) **A. Ordination of Aaron and his sons (chapter 8) **B. Aaron makes the first sacrifices (chapter 9) **C. Judgement onNadab and Abihu

In the biblical books Exodus, Leviticus and Numbers, Nadab () and Abihu () were the two oldest sons of Aaron. According to Leviticus 10, they offered a sacrifice with "foreign fire" before the , disobeying his instructions, and were immediate ...

(chapter 10)

*III. Uncleanliness and its treatment (11:1–15:33)

**A. Unclean animals (chapter 11)

**B. Childbirth as a source of uncleanliness (chapter 12)

**C. Unclean diseases (chapter 13)

**D. Cleansing of diseases (chapter 14)

**E. Unclean discharges (chapter 15)

*IV. Day of Atonement: purification of the tabernacle from the effects of uncleanliness and sin (chapter 16)

*V. Prescriptions for practical holiness (the Holiness Code

The Holiness code is used in biblical criticism to refer to Leviticus chapters 17–26, and sometimes passages in other books of the Pentateuch, especially Numbers and Exodus. It is so called due to its highly repeated use of the word ''holy ...

, chapters 17–26)

**A. Sacrifice and food (chapter 17)

**B. Sexual behaviour (chapter 18)

**C. Neighbourliness (chapter 19)

**D. Grave crimes (chapter 20)

**E. Rules for priests (chapter 21)

**F. Rules for eating sacrifices (chapter 22)

**G. Festivals (chapter 23)

**H. Rules for the tabernacle (chapter 24:1–9)

**I. Blasphemy (chapter 24:10–23)

**J. Sabbatical and Jubilee years (chapter 25)

**K. Exhortation to obey the law: blessing and curse (chapter 26)

*VI. Redemption of votive gifts (chapter 27)

Summary

Chapters 1–5 describe the various sacrifices from the sacrificers' point of view, although the priests are essential for handling the blood. Chapters 6–7 go over much the same ground, but from the point of view of the priest, who, as the one actually carrying out the sacrifice and dividing the "portions", needs to know how to do it. Sacrifices are between God, the priest, and the offerers, although in some cases the entire sacrifice is a single portion to God—i.e., burnt to ashes.

Chapters 8–10 describe how

Chapters 1–5 describe the various sacrifices from the sacrificers' point of view, although the priests are essential for handling the blood. Chapters 6–7 go over much the same ground, but from the point of view of the priest, who, as the one actually carrying out the sacrifice and dividing the "portions", needs to know how to do it. Sacrifices are between God, the priest, and the offerers, although in some cases the entire sacrifice is a single portion to God—i.e., burnt to ashes.

Chapters 8–10 describe how Moses

Moses hbo, מֹשֶׁה, Mōše; also known as Moshe or Moshe Rabbeinu (Mishnaic Hebrew: מֹשֶׁה רַבֵּינוּ, ); syr, ܡܘܫܐ, Mūše; ar, موسى, Mūsā; grc, Mωϋσῆς, Mōÿsēs () is considered the most important pro ...

consecrates Aaron and his sons as the first priests, the first sacrifices, and God's destruction of two of Aaron's sons for ritual offenses. The purpose is to underline the character of altar priesthood (i.e., those priests with power to offer sacrifices to God) as an Aaronite privilege, and the responsibilities and dangers of their position.Kugler, Hartin, p. 82

With sacrifice and priesthood established, chapters 11–15 instruct the lay people on purity (or cleanliness). Eating certain animals produces uncleanliness, as does giving birth; certain skin diseases (but not all) are unclean, as are certain conditions affecting walls and clothing (mildew and similar conditions); and genital discharges, including female menses and male gonorrhea, are unclean. The reasoning behind the food rules are obscure; for the rest the guiding principle seems to be that all these conditions involve a loss of "life force", usually but not always blood.

Leviticus 16 concerns the Day of Atonement

Yom Kippur (; he, יוֹם כִּפּוּר, , , ) is the holiest day in Judaism and Samaritanism. It occurs annually on the 10th of Tishrei, the first month of the Hebrew calendar. Primarily centered on atonement and repentance, the day's o ...

(though that phrase appears first in 23:27). This is the only day on which the High Priest is to enter the holiest part of the sanctuary, the holy of holies. He is to sacrifice a bull for the sins of the priests, and a goat for the sins of the laypeople. The priest is to send a second goat into the desert to "Azazel

In the Bible, the name Azazel (; he, עֲזָאזֵל ''ʿAzāʾzēl''; ar, عزازيل, ʿAzāzīl) appears in association with the scapegoat rite; the name represents a desolate place where a scapegoat bearing the sins of the Jews during ...

", bearing the sins of the whole people. Azazel may be a wilderness-demon, but its identity is mysterious.

Chapters 17–26 are the Holiness code

The Holiness code is used in biblical criticism to refer to Leviticus chapters 17–26, and sometimes passages in other books of the Pentateuch, especially Numbers and Exodus. It is so called due to its highly repeated use of the word ''holy ...

. It begins with a prohibition on all slaughter of animals outside the Temple, even for food, and then prohibits a long list of sexual contacts and also child sacrifice. The "holiness" injunctions which give the code its name begin with the next section: there are penalties for the worship of Molech

Moloch (; ''Mōleḵ'' or הַמֹּלֶךְ ''hamMōleḵ''; grc, Μόλοχ, la, Moloch; also Molech or Molek) is a name or a term which appears in the Hebrew Bible several times, primarily in the book of Leviticus. The Bible strongly co ...

, consulting mediums and wizards, cursing one's parents and engaging in unlawful sex. Priests receive instruction on mourning rituals and acceptable bodily defects. The punishment for blasphemy is death, and there is the setting of rules for eating sacrifices; there is an explanation of the calendar, and there are rules for sabbatical and Jubilee

A jubilee is a particular anniversary of an event, usually denoting the 25th, 40th, 50th, 60th, and the 70th anniversary. The term is often now used to denote the celebrations associated with the reign of a monarch after a milestone number of y ...

years; there are rules for oil lamps and bread in the sanctuary; and there are rules for slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

. The code ends by telling the Israelites they must choose between the law and prosperity on the one hand, or, on the other, horrible punishments, the worst of which will be expulsion from the land.

Chapter 27 is a disparate and probably late addition telling about persons and things serving as dedication to the Lord and how one can redeem, instead of fulfill, vows.

Composition

The majority of scholars have concluded that the Pentateuch received its final form during the Persian period (538–332 BC). Nevertheless, Leviticus had a long period of growth before reaching that form.Grabbe (1998), p. 92 The entire composition of the book of Leviticus is Priestly literature. Most scholars see chapters 1–16 (thePriestly code

The Priestly Code (in Hebrew ''Torat Kohanim'', תורת כהנים) is the name given, by academia,The book of Leviticus: composition and reception - Page 55 Rolf Rendtorff, Robert A. Kugler, Sarah Smith Bartel - 2003 "Research agrees that its r ...

) and chapters 17–26 (the Holiness code

The Holiness code is used in biblical criticism to refer to Leviticus chapters 17–26, and sometimes passages in other books of the Pentateuch, especially Numbers and Exodus. It is so called due to its highly repeated use of the word ''holy ...

) as the work of two related schools, but while the Holiness material employs the same technical terms as the Priestly code, it broadens their meaning from pure ritual to the theological and moral, turning the ritual of the Priestly code into a model for the relationship of Israel to Yahweh: as the tabernacle, which is apart from uncleanliness, becomes holy by the presence of Yahweh, so he will dwell among Israel when Israel receives purification (becomes holy) and separates from other peoples. The ritual instructions in the Priestly code apparently grew from priests giving instruction and answering questions about ritual matters; the Holiness code (or H) used to be a separate document, later becoming part of Leviticus, but it seems better to think of the Holiness authors as editors who worked with the Priestly code and actually produced Leviticus as is now extant.

Themes

Sacrifice and ritual

Many scholars argue that the rituals of Leviticus have a theological meaning concerning Israel's relationship with its God.Jacob Milgrom

Jacob Milgrom (February 1, 1923 – June 5, 2010) was a prominent American Jewish Bible scholar and Conservative rabbi. Milgrom's major contribution to biblical research was in the field of cult and worship. Although he accepted the documentar ...

was especially influential in spreading this view. He maintained that the priestly regulations in Leviticus expressed a rational system of theological thought. The writers expected them to be put into practice in Israel's temple, so the rituals would express this theology as well, as well as ethical concern for the poor. Milgrom also argued that the book's purity regulations (chapters 11–15) have a basis in ethical thinking. Many other interpreters have followed Milgrom in exploring the theological and ethical implications of Leviticus's regulations (e.g., Marx, Balentine), though some have questioned how systematic they really are. Ritual, therefore, is not taking a series of actions for their own sake, but a means of maintaining the relationship between God, the world, and humankind.

Kehuna (Jewish priesthood)

The main function of the priests is service at the altar, and only the sons of Aaron are priests in the full sense. (Ezekiel also distinguishes between altar-priests and lower Levites, but in Ezekiel the altar-priests are sons of Zadok instead of sons of Aaron; many scholars see this as a remnant of struggles between different priestly factions in First Temple times, finding resolution by the Second Temple into a hierarchy of Aaronite altar-priests and lower-level Levites, including singers, gatekeepers and the like). In chapter 10, God killsNadab and Abihu

In the biblical books Exodus, Leviticus and Numbers, Nadab () and Abihu () were the two oldest sons of Aaron. According to Leviticus 10, they offered a sacrifice with "foreign fire" before the , disobeying his instructions, and were immediate ...

, the oldest sons of Aaron, for offering "strange incense". Aaron has two sons left. Commentators have read various messages in the incident: a reflection of struggles between priestly factions in the post–Exilic period (Gerstenberger); or a warning against offering incense outside the Temple, where there might be the risk of invoking strange gods (Milgrom). In any case, there has been a pollution of the sanctuary by the bodies of the two dead priests, leading into the next theme, holiness.

Uncleanliness and purity

Ritual purity is essential for an Israelite to be able to approach Yahweh and remain part of the community. Uncleanliness threatens holiness; Chapters 11–15 review the various causes of uncleanliness and describe the rituals which will restore cleanliness; one is to maintain cleanliness through observation of the rules on sexual behaviour, family relations, land ownership, worship, sacrifice, and observance of holy days.Balentine (2002), p. 8Yahweh

Yahweh *''Yahwe'', was the national god of ancient Israel and Judah. The origins of his worship reach at least to the early Iron Age, and likely to the Late Bronze Age if not somewhat earlier, and in the oldest biblical literature he poss ...

dwells with Israel in the holy of holies. All of the priestly ritual focuses on Yahweh and the construction and maintenance of a holy space, but sin generates impurity, as do everyday events such as childbirth and menstruation; impurity pollutes the holy dwelling place. Failure to purify the sacred space ritually could result in God's leaving, which would be disastrous.

Infectious diseases in chapter 13

In chapter 13, God instructs Moses and Aaron on how to identify infectious diseases and deal with them accordingly. The translators and interpreters of the Hebrew Bible in various languages have never reached a consensus on these infectious diseases, or (Hebrew ), and the translation and interpretation of the scriptures are not known for certain. The most common translation is that these infectious diseases areleprosy

Leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease (HD), is a long-term infection by the bacteria ''Mycobacterium leprae'' or ''Mycobacterium lepromatosis''. Infection can lead to damage of the nerves, respiratory tract, skin, and eyes. This nerve damag ...

, however, what is described in chapter 13 does not represent a typical manifestation of leprosy. Modern dermatology shows that many of the infectious diseases in chapter 13 were likely dermatophytoses, a group of highly contagious skin diseases.

The infectious disease of the chin described in verses 29–37 seems to be Tinea barbae

Tinea barbae is a fungal infection of the hair. Tinea barbae is due to a dermatophytic infection around the bearded area of men. Generally, the infection occurs as a follicular inflammation, or as a cutaneous granulomatous lesion, i.e. a chronic i ...

in men or Tinea faciei

Tinea faciei is a fungal infection of the skin of the face. It generally appears as a photosensitive painless red rash with small bumps and a raised edge appearing to grow outwards, usually over eyebrows or one side of the face. It may feel wet or ...

in women; the infectious disease described in verses 29–37 (as resulting in hair loss and eventual baldness) seems to be Tinea capitis

Tinea capitis (also known as "herpes tonsurans", "ringworm of the hair", "ringworm of the scalp", "scalp ringworm", and "tinea tonsurans") is a cutaneous fungal infection (dermatophytosis) of the scalp. The disease is primarily caused by dermato ...

(Favus

Favus (Latin for " honeycomb") or tinea favosa is the severe form of tinea capitis, a skin infectious disease caused by the dermatophyte fungus ''Trichophyton schoenleinii.'' Typically the species affects the scalp, but occasionally occurs as ...

). Verses 1–17 seem to describe Tinea corporis

Tinea corporis is a fungal infection of the body, similar to other forms of tinea. Specifically, it is a type of dermatophytosis (or ringworm) that appears on the arms and legs, especially on glabrous skin; however, it may occur on any superficial ...

.

The Hebrew word in verses 38–39 is translated as tetter or freckles

Freckles are clusters of concentrated melaninized cells which are most easily visible on people with a fair complexion. Freckles do not have an increased number of the melanin-producing cells, or melanocytes, but instead have melanocytes that ...

, likely because translators did not know what it meant at the time, and thus, translated it incorrectly. Later translations identify it as talking about vitiligo

Vitiligo is a disorder that causes the skin to lose its color. Specific causes are unknown but studies suggest a link to immune system changes.

Signs and symptoms

The only sign of vitiligo is the presence of pale patchy areas of depigmen ...

; however, vitiligo is not an infectious disease. The disease, described as healing itself and leaving white patches after infection, is likely to be pityriasis versicolor

Pityriasis commonly refers to flaking (or scaling) of the skin. The word comes from the Greek πίτυρον "bran".

Classification

Types include:

* Pityriasis alba

* Pityriasis lichenoides chronica

* Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis ac ...

(tinea versicolor). ''Tetter'' originally referred to an outbreak, which later evolved meaning ringworm-like lesions. Therefore, a common name for Tinea pedis

Dermatophytosis, also known as ringworm, is a fungal infection of the skin. Typically it results in a red, itchy, scaly, circular rash. Hair loss may occur in the area affected. Symptoms begin four to fourteen days after exposure. Multiple a ...

(athlete's foot) was Cantlie's foot tetter. In addition, verses 18–23 describe infections after scald The structured computer-aided logic design (SCALD) software was a computer aided design system developed for building the S-1 computer. It used the Stanford University Drawing System (SUDS), and it was developed by Thomas M. McWilliams and Lawrence ...

, and verses 24–28 describe infections after burn

A burn is an injury to skin, or other tissues, caused by heat, cold, electricity, chemicals, friction, or ultraviolet radiation (like sunburn). Most burns are due to heat from hot liquids (called scalding), solids, or fire. Burns occur ma ...

.

Atonement

Through sacrifice, the priest "makes atonement" for sin and the offeror receives forgiveness (but only if Yahweh accepts the sacrifice). Atonement rituals involve the pouring or sprinkling of blood as the symbol of the life of the victim: the blood has the power to wipe out or absorb the sin.Houston, p. 107 The two-part division of the book structurally reflects the role of atonement: chapters 1–16 call for the establishment of the institution for atonement, and chapters 17–27 call for the life of the atoned community in holiness.

Through sacrifice, the priest "makes atonement" for sin and the offeror receives forgiveness (but only if Yahweh accepts the sacrifice). Atonement rituals involve the pouring or sprinkling of blood as the symbol of the life of the victim: the blood has the power to wipe out or absorb the sin.Houston, p. 107 The two-part division of the book structurally reflects the role of atonement: chapters 1–16 call for the establishment of the institution for atonement, and chapters 17–27 call for the life of the atoned community in holiness.

Holiness

The consistent theme of chapters 17–26 is in the repetition of the phrase, "Be holy, for I the Lord your God am holy." Holiness in ancient Israel and the Hebrew Bible had a different meaning than in contemporary usage: it might have been regarded as the essence of Yahweh, an invisible but physical and potentially dangerous force. Specific objects, or even days, can be holy, but they derive holiness from being connected with Yahweh—the seventh day, the tabernacle, and the priests all derive their holiness from him. As a result, Israel had to maintain its own holiness in order to live safely alongside God. The need for holiness is for the possession of the Promised Land (Canaan

Canaan (; Phoenician: 𐤊𐤍𐤏𐤍 – ; he, כְּנַעַן – , in pausa – ; grc-bib, Χανααν – ;The current scholarly edition of the Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus T ...

), where the Jews will become a holy people: "You shall not do as they do in the land of Egypt where you dwelt, and you shall not do as they do in the land of Canaan to which I am bringing you...You shall do my ordinances and keep my statutes...I am the Lord, your God." (Leviticus 18:3).

Subsequent tradition

Leviticus, as part of the Torah, became the law book of Jerusalem's

Leviticus, as part of the Torah, became the law book of Jerusalem's Second Temple

The Second Temple (, , ), later known as Herod's Temple, was the reconstructed Temple in Jerusalem between and 70 CE. It replaced Solomon's Temple, which had been built at the same location in the United Kingdom of Israel before being inherited ...

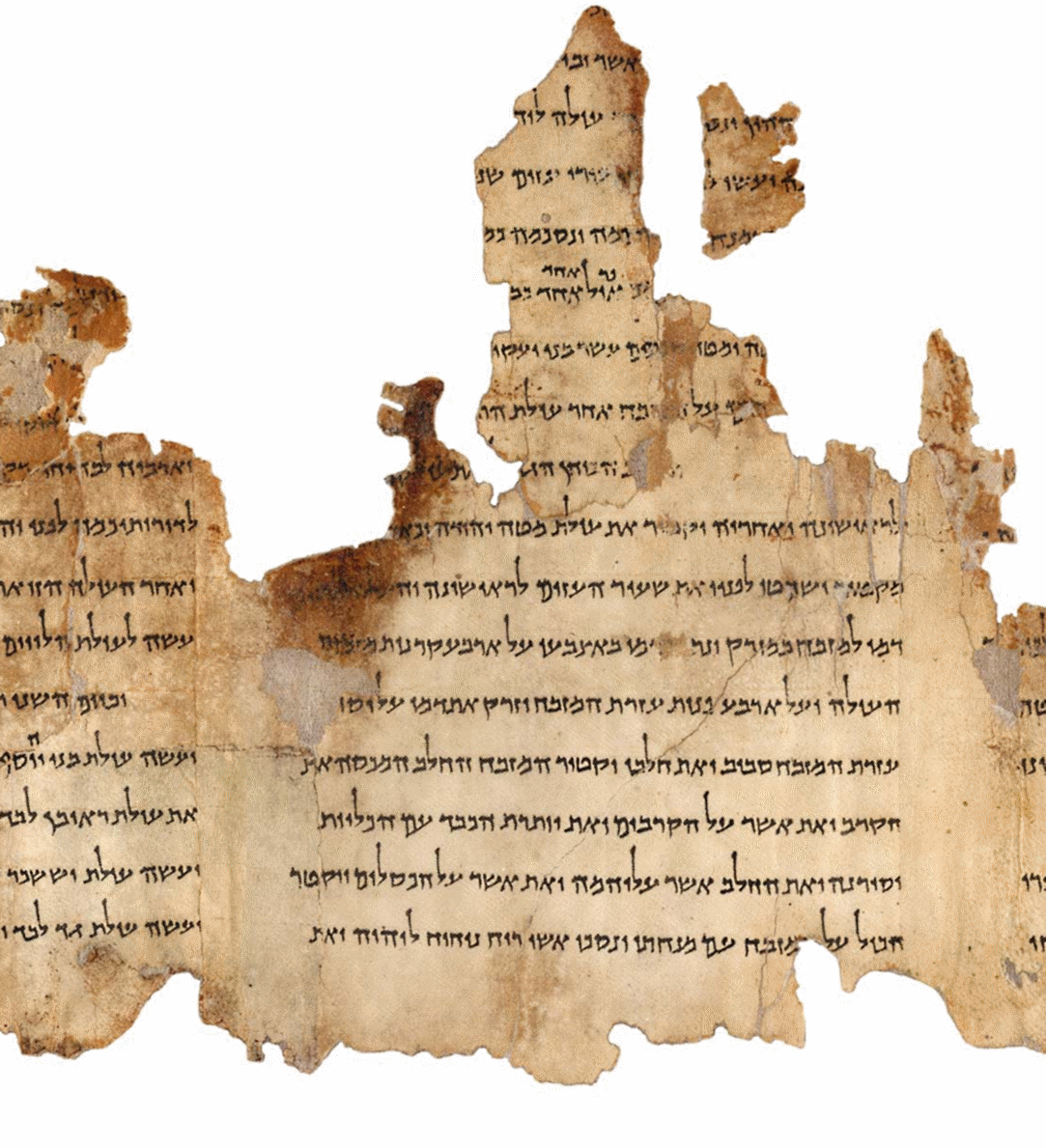

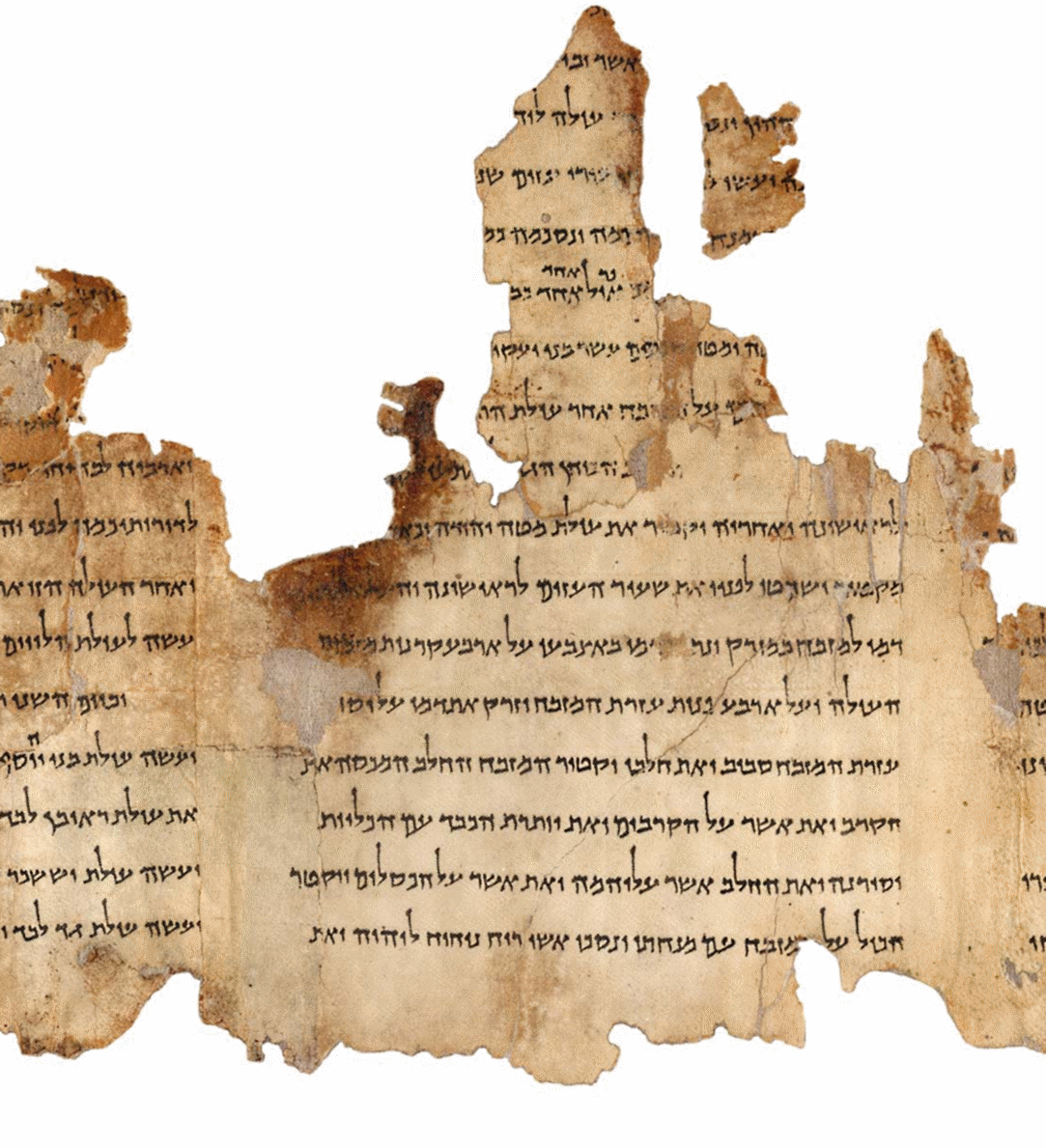

as well as of the Samaritan temple. Its influence is evident among the Dead Sea Scrolls

The Dead Sea Scrolls (also the Qumran Caves Scrolls) are ancient Jewish and Hebrew religious manuscripts discovered between 1946 and 1956 at the Qumran Caves in what was then Mandatory Palestine, near Ein Feshkha in the West Bank, on the ...

, which included fragments of seventeen manuscripts of Leviticus dating from the 3rd to the 1st centuries BC. Many other Qumran scrolls cite the book, especially the Temple Scroll

The Temple Scroll ( he, מגילת המקדש) is the longest of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Among the discoveries at Qumran it is designated: 11QTemple Scrolla (11Q19 1QTa. It describes a Jewish temple, along with extensive detailed regulations about s ...

and 4QMMT.

Jews and Christians have not observed Leviticus's instructions for animal offerings since the 1st century AD, following the destruction of the Second Temple

The siege of Jerusalem of 70 CE was the decisive event of the First Jewish–Roman War (66–73 CE), in which the Roman army led by future emperor Titus besieged Jerusalem, the center of Jewish rebel resistance in the Roman province of Ju ...

in Jerusalem in 70 AD. As there was no longer a Temple at which to offer animal sacrifices, Judaism pivoted towards prayer and the study of the Torah, eventually giving rise to Rabbinic Judaism

Rabbinic Judaism ( he, יהדות רבנית, Yahadut Rabanit), also called Rabbinism, Rabbinicism, or Judaism espoused by the Rabbanites, has been the mainstream form of Judaism since the 6th century CE, after the codification of the Babylonia ...

. Nevertheless, Leviticus constitutes a major source of Jewish law and is traditionally the first book children learn in the Rabbinic system of education. There are two main Midrash

''Midrash'' (;"midrash"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. he, מִדְרָשׁ; ...

im on Leviticus—the halakhic one (Sifra) and a more ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. he, מִדְרָשׁ; ...

aggadic

Aggadah ( he, ''ʾAggāḏā'' or ''Haggāḏā''; Jewish Babylonian Aramaic: אַגָּדְתָא ''ʾAggāḏəṯāʾ''; "tales, fairytale, lore") is the non-legalistic exegesis which appears in the classical rabbinic literature of Judaism ...

one (Vayikra Rabbah

Leviticus Rabbah, Vayikrah Rabbah, or Wayiqra Rabbah is a homiletic midrash to the Biblical book of Leviticus (''Vayikrah'' in Hebrew). It is referred to by Nathan ben Jehiel (c. 1035–1106) in his ''Arukh'' as well as by Rashi (1040–1105) ...

).

The New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christ ...

, particularly the Epistle to the Hebrews

The Epistle to the Hebrews ( grc, Πρὸς Ἑβραίους, Pros Hebraious, to the Hebrews) is one of the books of the New Testament.

The text does not mention the name of its author, but was traditionally attributed to Paul the Apostle. Most ...

, uses ideas and images from Leviticus to describe Christ as the high priest who offers his own blood as a sin offering

A sin offering ( he, קָרְבַּן חַטָּאת, ''korban ḥatat'', , lit: "purification offering") is a sacrificial offering described and commanded in the Torah (Lev. 4.1-35); it could be fine flour or a proper animal.Leviticus 5:11 A sin ...

. Therefore, Christians do not make animal offerings either, because as Gordon Wenham summarized: "With the death of Christ the only sufficient 'burnt offering' was offered once and for all, and therefore the animal sacrifices which foreshadowed Christ's sacrifice were made obsolete."

Christians generally have the view that the New Covenant

The New Covenant (Hebrew '; Greek ''diatheke kaine'') is a biblical interpretation which was originally derived from a phrase which is contained in the Book of Jeremiah ( Jeremiah 31:31-34), in the Hebrew Bible (or the Old Testament of the C ...

supersedes the Old Testament's ritual laws, which includes many of the rules in Leviticus. Christians, therefore, do not usually follow Leviticus' rules regarding diet, purity, and agriculture. Christian teachings have differed, however, as to where to draw the line between ritual and moral regulations. In ''Homilies on Leviticus'', the third century theologian, Origen

Origen of Alexandria, ''Ōrigénēs''; Origen's Greek name ''Ōrigénēs'' () probably means "child of Horus" (from , "Horus", and , "born"). ( 185 – 253), also known as Origen Adamantius, was an Early Christianity, early Christian scholar, ...

, expounded on the qualities of priests as models for Christians to be perfect in everything, strict, wise and to examine themselves individually, forgive sins, and convert sin

In a religious context, sin is a transgression against divine law. Each culture has its own interpretation of what it means to commit a sin. While sins are generally considered actions, any thought, word, or act considered immoral, selfish, s ...

ners (by words and by doctrine).

Judaism's weekly Torah portions in the Book of Leviticus

Vayikra

The book of Leviticus (, from grc, Λευιτικόν, ; he, וַיִּקְרָא, , "And He called") is the third book of the Torah (the Pentateuch) and of the Old Testament, also known as the Third Book of Moses. Scholars generally agree ...

'', on Leviticus 1–5: Laws of the sacrifices

* ''Tzav

Tzav, Tsav, Zav, Sav, or Ṣaw ( — Hebrew for "command," the sixth word, and the first distinctive word, in the parashah) is the 25th weekly Torah portion (, ''parashah'') in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the second in the Book of ...

'', on Leviticus 6–8: Sacrifices, ordination of the priests

* '' Shemini'', on Leviticus 9–11: Concecration of tabernacle, alien fire, dietary laws

* ''Tazria

Tazria, Thazria, Thazri'a, Sazria, or Ki Tazria (—Hebrew for "childbirth", the 13th word, and the first distinctive word, in the ''parashah'', where the root word means "seed") is the 27th weekly Torah portion (, ''parashah'') in the annual Jew ...

'', on Leviticus 12–13: Childbirth, skin disease, clothing

* '' Metzora'', on Leviticus 14–15: Skin disease, unclean houses, genital discharges

* ''Acharei Mot

Acharei Mot (also Aharei Mot, Aharei Moth, or Acharei Mos) (, Hebrew for "after the death") is the 29th weekly Torah portion in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading. It is the sixth weekly portion (, ''parashah'') in the Book of Leviticus, c ...

'', on Leviticus 16– 18: Yom Kippur, centralized offerings, sexual practices

* ''Kedoshim

Kedoshim, K'doshim, or Qedoshim ( — Hebrew for "holy ones," the 14th word, and the first distinctive word, in the parashah) is the 30th weekly Torah portion (, ''parashah'') in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the seventh in the Book ...

'', on Leviticus 19

Leviticus 19 is the nineteenth chapter of the Book of Leviticus in the Hebrew Bible or the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. It contains laws on a variety of topics, and is attributed by tradition to Moses.See page 239 in Carmichael, Calum M. ...

–20: Holiness, penalties for transgressions

* ''Emor

Emor ( he, אֱמֹר — Hebrew for "speak," the fifth word, and the first distinctive word, in the parashah) is the 31st weekly Torah portion ( he, פָּרָשָׁה, ''parashah'') in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the eighth in ...

'', on Leviticus 21–24: Rules for priests, holy days, lights and bread, a blasphemer

* ''Behar

Behar, BeHar, Be-har, or B'har ( — Hebrew language, Hebrew for "on the mount," the fifth word, and the Incipit, first distinctive word, in the parashah) is the 32nd weekly Torah portion (, ''parashah'') in the annual Judaism, Jewish cycle of Tor ...

'', on Leviticus 25–25: Sabbatical year, debt servitude limited

* ''Bechukotai Bechukotai, Bechukosai, or Bəḥuqothai (Biblical) ( ''bəḥuqqōṯay'' — Hebrew for "by my decrees," the second word, and the first distinctive word, in the parashah) is the 33rd weekly Torah portion (, ''parashah'') in the annual Jewish cycl ...

'', on Leviticus 26–27: Blessings and curses, payment of vows

See also

* 613 commandments *En-Gedi Scroll

The En-Gedi Scroll is an ancient Hebrew parchment found in 1970 at Ein Gedi, Israel. Radiocarbon testing dates the scroll to the third or fourth century CE (210–390 CE), although paleographical considerations suggest that the scrolls may date b ...

* Paleo-Hebrew Leviticus scroll

Paleo-Hebrew Leviticus Scroll, known also as 11QpaleoLev, is an ancient text preserved in one of the Qumran group of caves, and which provides a rare glimpse of the script used formerly by the nation of Israel in writing Torah scrolls during its ...

* Liberty Bell – inscribed with a quotation from Leviticus

References

Bibliography

Translations of Leviticus

Leviticus

at Bible gateway

Commentaries on Leviticus

* * Bamberger, Bernard Jacob The Torah: A Modern Commentary (1981), * * * * * * * * * * *General

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Online versions of Leviticus: *Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

:

*Leviticus at Mechon-Mamre

(Jewish Publication Society translation) *

Leviticus (The Living Torah)

Rabbi

Aryeh Kaplan

Aryeh Moshe Eliyahu Kaplan ( he, אריה משה אליהו קפלן; October 23, 1934 – January 28, 1983) was an American Orthodox rabbi, author, and translator, best known for his Living Torah edition of the Torah. He became well known as ...

's translation and commentary at Ort.org

*Vayikra–Levitichius (Judaica Press)

translation ith_Rashi's_commentary.html"_;"title="Rashi.html"_;"title="ith_Rashi">ith_Rashi's_commentary">Rashi.html"_;"title="ith_Rashi">ith_Rashi's_commentaryat_Chabad.org *

(

ith_Rashi's_commentary.html"_;"title="Rashi.html"_;"title="ith_Rashi">ith_Rashi's_commentary">Rashi.html"_;"title="ith_Rashi">ith_Rashi's_commentaryat_Chabad.org

*

ויקרא__''Vayikra''–Leviticus

(Hebrew_language">Hebrew_

Hebrew_(;_;_)_is_a__Northwest_Semitic_language_of_the_Afroasiatic_language_family._Historically,_it_is_one_of_the_spoken_languages_of_the_Israelites_and_their_longest-surviving_descendants,_the_Jews_and__Samaritans._It_was_largely_preserved__...

–English_at_Mechon-Mamre.org)

*_Christianity.html" "title="Hebrew_language.html" "title="Rashi">ith_Rashi's_commentary.html" ;"title="Rashi.html" ;"title="ith Rashi">ith Rashi's commentary">Rashi.html" ;"title="ith Rashi">ith Rashi's commentaryat Chabad.org

*(Hebrew_language">Hebrew

ויקרא ''Vayikra''–Leviticus

(Hebrew language">Hebrew Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

The Book of Leviticus, Douay Rheims Version, with Bishop Challoner Commentaries

''Online Bible'' at GospelHall.org

(

King James Version

The King James Version (KJV), also the King James Bible (KJB) and the Authorized Version, is an Bible translations into English, English translation of the Christian Bible for the Church of England, which was commissioned in 1604 and publis ...

)

''Online Audio and Classic Bible'' at Bible-Book.org

(

King James Version

The King James Version (KJV), also the King James Bible (KJB) and the Authorized Version, is an Bible translations into English, English translation of the Christian Bible for the Church of England, which was commissioned in 1604 and publis ...

)

*''oremus Bible Browser''

(

New Revised Standard Version

The New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) is an English translation of the Bible published in 1989 by the National Council of Churches.''oremus Bible Browser''

(''Anglicized''

(''Anglicized''

New Revised Standard Version

The New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) is an English translation of the Bible published in 1989 by the National Council of Churches.Book of Leviticus article

(Jewish Encyclopedia)

The Literary Structure of Leviticus

(chaver.com) Brief introduction

Leviticus

{{DEFAULTSORT:Book Of Leviticus 7th-century BC books 6th-century BC books 5th-century BC books 4th-century BC books Tabernacle and Temples in Jerusalem 3 The Exodus

(Jewish Encyclopedia)

The Literary Structure of Leviticus

(chaver.com) Brief introduction

Leviticus

{{DEFAULTSORT:Book Of Leviticus 7th-century BC books 6th-century BC books 5th-century BC books 4th-century BC books Tabernacle and Temples in Jerusalem 3 The Exodus