Bolesław Bierut on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Bolesław Bierut (; 18 April 1892 – 12 March 1956) was a

Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, w ...

communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

activist and politician, leader of the Polish People's Republic

The Polish People's Republic ( pl, Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa, PRL) was a country in Central Europe that existed from 1947 to 1989 as the predecessor of the modern Republic of Poland. With a population of approximately 37.9 million nea ...

from 1947 until 1956. He was President of the State National Council

Krajowa Rada Narodowa in Polish (translated as State National Council or Homeland National Council, abbreviated to KRN) was a parliament-like political body created during the later stages of World War II in German-occupied Warsaw, Poland. It wa ...

from 1944 to 1947, President of Poland

The president of Poland ( pl, Prezydent RP), officially the president of the Republic of Poland ( pl, Prezydent Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej), is the head of state of Poland. Their rights and obligations are determined in the Constitution of Polan ...

from 1947 to 1952, General Secretary

Secretary is a title often used in organizations to indicate a person having a certain amount of authority, power, or importance in the organization. Secretaries announce important events and communicate to the organization. The term is derived ...

of the Central Committee

Central committee is the common designation of a standing administrative body of Communist party, communist parties, analogous to a board of directors, of both ruling and nonruling parties of former and existing socialist states. In such party org ...

of the Polish United Workers' Party

The Polish United Workers' Party ( pl, Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza; ), commonly abbreviated to PZPR, was the communist party which ruled the Polish People's Republic as a one-party state from 1948 to 1989. The PZPR had led two other lega ...

from 1948 to 1956, and Prime Minister of Poland

The President of the Council of Ministers ( pl, Prezes Rady Ministrów, lit=Chairman of the Council of Ministers), colloquially referred to as the prime minister (), is the head of the cabinet and the head of government of Poland. The responsibi ...

from 1952 to 1954. Bierut was a self-educated person. He implemented aspects of the Stalinist

Stalinism is the means of governing and Marxist-Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union from 1927 to 1953 by Joseph Stalin. It included the creation of a one-party totalitarian police state, rapid industrialization, the theory o ...

system in Poland.Jerzy Eisler, ''Siedmiu wspaniałych. Poczet pierwszych sekretarzy KC PZPR'' he Magnificent Seven: first secretaries of the PZPR pp. 32–35. Wydawnictwo Czerwone i Czarne, Warszawa 2014, . Together with Władysław Gomułka

Władysław Gomułka (; 6 February 1905 – 1 September 1982) was a Polish communist politician. He was the ''de facto'' leader of post-war Poland from 1947 until 1948. Following the Polish October he became leader again from 1956 to 1970. Go ...

, his main rival, Bierut is chiefly responsible for the historic changes that Poland underwent in the aftermath of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. Unlike any of his communist successors, Bierut led Poland until his death.

Born in Congress Poland

Congress Poland, Congress Kingdom of Poland, or Russian Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. It w ...

on the outskirts of Lublin

Lublin is the ninth-largest city in Poland and the second-largest city of historical Lesser Poland. It is the capital and the center of Lublin Voivodeship with a population of 336,339 (December 2021). Lublin is the largest Polish city east of t ...

, Bierut entered politics in 1912 by joining the Polish Socialist Party

The Polish Socialist Party ( pl, Polska Partia Socjalistyczna, PPS) is a socialist political party in Poland.

It was one of the most important parties in Poland from its inception in 1892 until its merger with the communist Polish Workers' P ...

. Later he became a member of the Communist Party of Poland

The interwar Communist Party of Poland ( pl, Komunistyczna Partia Polski, KPP) was a communist party active in Poland during the Second Polish Republic. It resulted from a December 1918 merger of the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland a ...

and spent some years in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, where he functioned as an agent of the Comintern

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet Union, Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to ...

, educated at the Soviet International Lenin School

The International Lenin School (ILS) was an official training school operated in Moscow, Soviet Union, by the Communist International from May 1926 to 1938. It was resumed after the Second World War and run by the Communist Party of the Soviet Unio ...

and similar institutions elsewhere in Europe. He was sentenced to a prison term in 1935 for conducting illegal labor activity in Poland by the anti-communist Sanation

Sanation ( pl, Sanacja, ) was a Polish political movement that was created in the interwar period, prior to Józef Piłsudski's May 1926 ''Coup d'État'', and came to power in the wake of that coup. In 1928 its political activists would go on ...

government. Having only attended an elementary school for several years before being expelled, he later developed an interest in economics and took some cooperative courses at the Warsaw School of Economics

SGH Warsaw School of Economics ( pl, Szkoła Główna Handlowa w Warszawie, ''SGH''cooperative

A cooperative (also known as co-operative, co-op, or coop) is "an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democratically-control ...

movement in his youth. After his release from prison in 1938, he was employed as an accountant for Społem

PSS Społem is a Polish consumers' co-operative of local grocery stores founded in 1868.

Each of the branches of PSS Społem during the Partitions of Poland were formed via different conditions in law, economy and politics. The common character ...

until the outbreak of the war.

During the war, Bierut was an activist of the newly founded Polish Workers' Party

The Polish Workers' Party ( pl, Polska Partia Robotnicza, PPR) was a communist party in Poland from 1942 to 1948. It was founded as a reconstitution of the Communist Party of Poland (KPP) and merged with the Polish Socialist Party (PPS) in 1948 ...

(PPR) and subsequently the chairman of the State National Council (KRN), established by the PPR. As the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

pushed the Nazi Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previous ...

from eastern Poland, liberated Lublin was made the temporary headquarters of the Polish Committee of National Liberation

The Polish Committee of National Liberation (Polish: ''Polski Komitet Wyzwolenia Narodowego'', ''PKWN''), also known as the Lublin Committee, was an executive governing authority established by the Soviet-backed communists in Poland at the lat ...

at his initiative. Trusted by Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

, Bierut participated in the Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference (german: Potsdamer Konferenz) was held at Potsdam in the Soviet occupation zone from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to allow the three leading Allies to plan the postwar peace, while avoiding the mistakes of the Paris Pe ...

, where he successfully lobbied for the establishment of Poland's western border at the Oder–Neisse line

The Oder–Neisse line (german: Oder-Neiße-Grenze, pl, granica na Odrze i Nysie Łużyckiej) is the basis of most of the international border between Germany and Poland from 1990. It runs mainly along the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers a ...

. The conference thus granted Poland the post-German "Recovered Territories

The Recovered Territories or Regained Lands ( pl, Ziemie Odzyskane), also known as Western Borderlands ( pl, Kresy Zachodnie), and previously as Western and Northern Territories ( pl, Ziemie Zachodnie i Północne), Postulated Territories ( pl, Z ...

" at their maximum possible extent.

After the 1947 Polish legislative election

Parliamentary elections were held in Poland on 19 January 1947, Dieter Nohlen & Philip Stöver (2010) ''Elections in Europe: A data handbook'', p1491 the first since World War II. According to the official results, the Democratic Bloc (''Blok De ...

, marked by electoral fraud, Bierut was made the first post-war President of Poland. In 1952, the new Constitution of the Polish People's Republic

The Constitution of the Polish People's Republic (also known as the July Constitution or the Constitution of 1952) was a supreme law passed in communist-ruled Poland on 22 July 1952. It superseded the post-World War II provisional Small Cons ...

(until then known as the Republic of Poland) abolished the position of president and a Marxist–Leninist

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialect ...

government was officially imposed. Bierut supported the radical Stalinist policies as well as the systematic introduction of socialist realism

Socialist realism is a style of idealized realistic art that was developed in the Soviet Union and was the official style in that country between 1932 and 1988, as well as in other socialist countries after World War II. Socialist realism is ch ...

in Poland. His regime was marked by a silent terror – he presided over the hunting down of armed opposition members and their eventual murder at the hands of the Ministry of Public Security (UB), including some former members of the Home Army

The Home Army ( pl, Armia Krajowa, abbreviated AK; ) was the dominant resistance movement in German-occupied Poland during World War II. The Home Army was formed in February 1942 from the earlier Związek Walki Zbrojnej (Armed Resistance) esta ...

. Under Bierut's supervision, the UB evolved into a notorious secret police

Secret police (or political police) are intelligence, security or police agencies that engage in covert operations against a government's political, religious, or social opponents and dissidents. Secret police organizations are characteristic of a ...

which was, according to some sources, responsible for the execution of six thousand people between 1944 and 1956 according to the Hoover Institution

The Hoover Institution (officially The Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace; abbreviated as Hoover) is an American public policy think tank and research institution that promotes personal and economic liberty, free enterprise, and ...

."Jakub Berman’s Papers Received at the Hoover Institution Archives"Stanford University

Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies , among the largest in the United States, and enrolls over 17,000 students. Stanford is consider ...

Hoover Institution

The Hoover Institution (officially The Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace; abbreviated as Hoover) is an American public policy think tank and research institution that promotes personal and economic liberty, free enterprise, and ...

, August 11, 2008 As Poland's ''de facto'' leader, he resided in the Belweder

Belweder (; from the Italian language, Italian ''belvedere'', "beautiful view") is a Neoclassical architecture, neoclassical palace in Warsaw, Poland. Erected in 1660 and remodelled in the early 1800s, it is one of several official residences u ...

Palace and headed the Polish United Workers' Party from the party headquarters at New World Street

New is an adjective referring to something recently made, discovered, or created.

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

Albums and EPs

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator, ...

in central Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officia ...

, known as ''Dom Partii''. He was also the chief proponent for the reconstruction of Warsaw (rebuilding of the historic district

A historic district or heritage district is a section of a city which contains older buildings considered valuable for historical or architectural reasons. In some countries or jurisdictions, historic districts receive legal protection from c ...

) and the erection of the Palace of Culture and Science

A palace is a grand residence, especially a royal residence, or the home of a head of state or some other high-ranking dignitary, such as a bishop or archbishop. The word is derived from the Latin name palātium, for Palatine Hill in Rome which ...

.

Bolesław Bierut died of a heart attack on 12 March 1956 in Moscow, after attending the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was held during the period 14–25 February 1956. It is known especially for First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev's "Secret Speech", which denounced the personality cult and dictatorship ...

. His death was sudden, and many theories arose questioning the circumstances in which he died. His body was brought back to Poland and buried with honours in a monumental tomb at the Powązki Military Cemetery

Powązki Military Cemetery (; pl, Cmentarz Wojskowy na Powązkach) is an old military cemetery located in the Żoliborz district, western part of Warsaw, Poland. The cemetery is often confused with the older Powązki Cemetery, known colloquial ...

.

Career

Youth and early career

Bierut was born in Rury,Congress Poland

Congress Poland, Congress Kingdom of Poland, or Russian Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. It w ...

(then part of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

), now a part of Lublin

Lublin is the ninth-largest city in Poland and the second-largest city of historical Lesser Poland. It is the capital and the center of Lublin Voivodeship with a population of 336,339 (December 2021). Lublin is the largest Polish city east of t ...

, to Wojciech and Marianna Salomea (Wolska) Bierut, peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasants ...

s from the Tarnobrzeg

Tarnobrzeg is a city in south-eastern Poland (historic Lesser Poland), on the east bank of the river Vistula, with 49,419 inhabitants, as of 31 December 2009. Situated in the Subcarpathian Voivodeship (Polish: ''Województwo podkarpackie'') since ...

area, the youngest of their six children. In 1900, he attended an elementary school in Lublin. In 1905, he was removed from the school for instigating anti-Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

protests. From the age of fourteen he was employed in various trades, but obtained further education through self-studies. Influenced by the leftist

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

intellectual Jan Hempel, who in 1910 arrived in Lublin, before World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

Bierut joined the Polish Socialist Party – Left

Polish Socialist Party – Left ( pl, Polska Partia Socjalistyczna – Lewica, PPS–L), also known as the Young Faction ( pl, Młodzi, links=no), was one of two factions into which Polish Socialist Party divided itself in 1906. Its primary goal ...

(''PPS – Lewica'').Jerzy Eisler, ''Siedmiu wspaniałych. Poczet pierwszych sekretarzy KC PZPR'' he Magnificent Seven: first secretaries of the PZPR pp. 38–41.

From 1915, Bierut was active in the cooperative

A cooperative (also known as co-operative, co-op, or coop) is "an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democratically-control ...

movement. In 1916, he became trade manager of the Lublin Food Cooperative, and from 1918 was its top leader, declaring the cooperative's "class

Class or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used differentl ...

-socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

" character. During World War I, he stayed at times at Hempel's apartment in Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officia ...

and took trade

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

An early form of trade, barter, saw the direct excha ...

and cooperative courses at the Warsaw School of Economics

SGH Warsaw School of Economics ( pl, Szkoła Główna Handlowa w Warszawie, ''SGH'' In Warsaw, he established contacts with

In 1922–25, Bierut was a member of the Cooperative Department of the KPRP

In 1922–25, Bierut was a member of the Cooperative Department of the KPRP  In 1930–31, Bierut was sent by the

In 1930–31, Bierut was sent by the

Continuing as the KRN president, from August 1944 Bierut was secretly a member of the newly created

Continuing as the KRN president, from August 1944 Bierut was secretly a member of the newly created  A military department of the PPR Central Committee was created on 31 October 1944 and included Bierut and Gomułka, in addition to three generals. Its goal was to politicize the armed forces, currently fighting the war, and to establish a politically reliable officer corps. According to Eisler, Bierut and Gomułka are both responsible for the post-war persecution of many former

A military department of the PPR Central Committee was created on 31 October 1944 and included Bierut and Gomułka, in addition to three generals. Its goal was to politicize the armed forces, currently fighting the war, and to establish a politically reliable officer corps. According to Eisler, Bierut and Gomułka are both responsible for the post-war persecution of many former

On 30 June 1946, the Polish people's referendum took place. It was done in preparation for the

On 30 June 1946, the Polish people's referendum took place. It was done in preparation for the  On 16 November 1947, during the opening ceremony of the

On 16 November 1947, during the opening ceremony of the

Gomułka, general secretary of the PPR (and until that time the principal figure in post-war Polish communist establishment), was accused of a "right-wing nationalistic deviation" and removed from his position during a plenary meeting of the Central Committee in August 1948. The move was Stalin-orchestrated and Stalin's choice to fill the vacated job was President Bierut, who had thus become both the top party leader and top state official.

The historic PPS was practically taken over by the PPR at the Unification Congress, held in Warsaw in December 1948. The resulting "

Gomułka, general secretary of the PPR (and until that time the principal figure in post-war Polish communist establishment), was accused of a "right-wing nationalistic deviation" and removed from his position during a plenary meeting of the Central Committee in August 1948. The move was Stalin-orchestrated and Stalin's choice to fill the vacated job was President Bierut, who had thus become both the top party leader and top state official.

The historic PPS was practically taken over by the PPR at the Unification Congress, held in Warsaw in December 1948. The resulting " In early August 1951, Bierut had his main rival Gomułka and his wife arrested. Gomułka, though imprisoned, refused to cooperate with his accusers and displayed remarkable ability to defend himself, while Bierut's people bungled the prosecution. According to

In early August 1951, Bierut had his main rival Gomułka and his wife arrested. Gomułka, though imprisoned, refused to cooperate with his accusers and displayed remarkable ability to defend himself, while Bierut's people bungled the prosecution. According to

The apogee of Bierut's

The apogee of Bierut's

In March 1953, Bierut led the Polish delegation for Stalin's funeral in Moscow.Jerzy Eisler, ''Siedmiu wspaniałych. Poczet pierwszych sekretarzy KC PZPR'' he Magnificent Seven: first secretaries of the PZPR pp. 85–88.

The regime's relations with the

In March 1953, Bierut led the Polish delegation for Stalin's funeral in Moscow.Jerzy Eisler, ''Siedmiu wspaniałych. Poczet pierwszych sekretarzy KC PZPR'' he Magnificent Seven: first secretaries of the PZPR pp. 85–88.

The regime's relations with the

The

The  The deceased leader was given a splendid funeral in Warsaw. A period of national mourning was declared. Catholic bishops conceded to the demand that church bells ring all over the country on the day of the funeral.

In a radio address on 14 March, Helena Jaworska, chairperson of the board of the

The deceased leader was given a splendid funeral in Warsaw. A period of national mourning was declared. Catholic bishops conceded to the demand that church bells ring all over the country on the day of the funeral.

In a radio address on 14 March, Helena Jaworska, chairperson of the board of the

On 1 June 1987, a factory in

On 1 June 1987, a factory in

Partisan Cross

*

Partisan Cross

*

Medal for Warsaw 1939–1945

Medal for Warsaw 1939–1945

Maria Koszutska

Maria Karolina Sabina Koszutska (pseudonym ''Wera Kostrzewa'') (2 February 1876, Główczyn – 9 July 1939, Moscow) was a leader and theoretician of the Polish Socialist Party "Left" faction ''(Polska Partia Socialistyczna, PPS — Lewic ...

and in December 1918 some form of association with the newly created Communist Workers' Party of Poland (KPRP), from which, according to his later testimony, he withdrew in fall 1919. Bierut kept assuming ever higher offices in the cooperative movement. In 1919 he and Hempel went to Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

, where they represented the Polish cooperatives at the congress of their Czechoslovak

Czechoslovak may refer to:

*A demonym or adjective pertaining to Czechoslovakia (1918–93)

**First Czechoslovak Republic (1918–38)

**Second Czechoslovak Republic (1938–39)

**Third Czechoslovak Republic (1948–60)

**Fourth Czechoslovak Repub ...

counterparts. Bierut's increasingly radical views, however, eventually hindered his cooperative career and caused his departure from the leadership of the movement, beginning in 1921. From 1921, he officially functioned as a member of the KPRP.

In July 1921 Bierut married Janina Górzyńska, a preschool teacher who had helped him a great deal when his illegal activities forced him to hide from the police. They were married by a priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particu ...

at the Lublin Cathedral, even though the priest, according to Janina, excused them from the confession

A confession is a statement – made by a person or by a group of persons – acknowledging some personal fact that the person (or the group) would ostensibly prefer to keep hidden. The term presumes that the speaker is providing information th ...

requirement. In February 1923 their daughter Krystyna was born, followed by son Jan in January 1925.

Communist party activism until 1939

In 1922–25, Bierut was a member of the Cooperative Department of the KPRP

In 1922–25, Bierut was a member of the Cooperative Department of the KPRP Central Committee

Central committee is the common designation of a standing administrative body of Communist party, communist parties, analogous to a board of directors, of both ruling and nonruling parties of former and existing socialist states. In such party org ...

. He worked as an accountant and was active in Warsaw at the Polish Association of Freethinkers

Polish Association of Freethinkers (PAF) ( pl, Stowarzyszenie Wolnomyślicieli Polskich; SWP) is a secular movement established in 1907 in Warsaw. Polish Association of Freethinkers was the first such organization in the Polish lands.

History

...

. In August 1923, he was sent for party work in the Dąbrowa Basin

The Dąbrowa Basin (also, Dąbrowa Coal Basin) or Zagłębie Dąbrowskie () is a geographical and historical region in southern Poland. It forms western part of Lesser Poland, though it shares some cultural and historical features with the neighbo ...

, to manage the Workers' Food Cooperative. He lived in Sosnowiec

Sosnowiec is an industrial city county in the Dąbrowa Basin of southern Poland, in the Silesian Voivodeship, which is also part of the Silesian Metropolis municipal association.—— Located in the eastern part of the Upper Silesian Industria ...

, where he brought his wife and daughter and where he experienced the first of his many arrests. Detained repeatedly in various parts of the country, in October 1924 he moved to Warsaw. He had become a full-time conspiratorial party activist and in 1925 was a member of the Temporary Secretariat of the Central Committee and then the head of the Cooperative Department there.Jerzy Eisler, ''Siedmiu wspaniałych. Poczet pierwszych sekretarzy KC PZPR'' he Magnificent Seven: first secretaries of the PZPR pp. 41–48.

Already trusted by the Soviets

Soviet people ( rus, сове́тский наро́д, r=sovyétsky naród), or citizens of the USSR ( rus, гра́ждане СССР, grázhdanye SSSR), was an umbrella demonym for the population of the Soviet Union.

Nationality policy in th ...

and knowing the Russian language

Russian (russian: русский язык, russkij jazyk, link=no, ) is an East Slavic languages, East Slavic language mainly spoken in Russia. It is the First language, native language of the Russians, and belongs to the Indo-European langua ...

well, from October 1925 to June 1926 Bierut was in the Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

area, sent there for training at the secret school of the Communist International

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by a ...

.

Arrested in Warsaw in January 1927, he was released on 30 April, based on personal assurances issued on his behalf by Stanisław Szwalbe and Zygmunt Zaremba

Zygmunt Witalis Zaremba (born 1895, Piotrków, Poland – died 5 October 1967, Sceaux, France), pseudonyms ''Andrzej Czarski'' (''Czerski''), ''Wit Smrek'', was a Polish socialist activist and publicist.

Biography

Zaremba was a member of ...

. During the Fourth Congress of the Communist Party of Poland

The interwar Communist Party of Poland ( pl, Komunistyczna Partia Polski, KPP) was a communist party active in Poland during the Second Polish Republic. It resulted from a December 1918 merger of the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland a ...

(KPP, the new name of the KPRP), which took place from 22 May to 9 August 1927, Bierut became a member of the Temporary Secretariat of the Central Committee again. In November, the party sent him to the International Lenin School

The International Lenin School (ILS) was an official training school operated in Moscow, Soviet Union, by the Communist International from May 1926 to 1938. It was resumed after the Second World War and run by the Communist Party of the Soviet Unio ...

in Moscow. He received positive evaluations there, except for not being entirely free of ideological right-wing

Right-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that view certain social orders and hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position on the basis of natural law, economics, authorit ...

errors, characteristic, in the school's opinion, of the Polish communist party.

In 1930–31, Bierut was sent by the

In 1930–31, Bierut was sent by the Comintern

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet Union, Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to ...

to Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

and Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

. Many details of his activities are not reliably known, but from 1 October 1930 he was an instructor at the Executive Committee of the Comintern. He later claimed having lived in Moscow in 1927–32, except for a nine-month period in 1931, and having been enrolled at the Lenin School until 1930. Jerzy Eisler

Jerzy Krzysztof Eisler (born 12 June 1952 in Warsaw) is a Polish historian, focusing mostly on the history of Poland during the communist era. He is a professor at the History Institute of the Polish Academy of Sciences, and member of the Institut ...

wrote: "... in light of the Soviet archival materials, in 1927–32 Bierut was a member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

"Hymn of the Bolshevik Party"

, headquarters = 4 Staraya Square, Moscow

, general_secretary = Vladimir Lenin (first) Mikhail Gorbachev (last)

, founded =

, banned =

, founder = Vladimir Lenin

, newspaper ...

(Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

), with his party seniority counted from 1921, the moment he formally joined the Polish communist party." In Moscow he met Małgorzata Fornalska, a KPP activist. They became romantically involved and had a daughter, named Aleksandra, born in June 1932. Soon afterwards Bierut left for Poland, leaving in Moscow for the time being also his legal family, whom he had brought there.

For several months Bierut was district secretary of the KPP organization in Łódź

Łódź, also rendered in English as Lodz, is a city in central Poland and a former industrial centre. It is the capital of Łódź Voivodeship, and is located approximately south-west of Warsaw. The city's coat of arms is an example of canti ...

. After the regional organization was demolished by arrests, in 1933 he became secretary of the Central Committee of the Polish section of the International Red Aid

International Red Aid (also commonly known by its Russian acronym MOPR ( ru , МОПР, for: ''Междунаро́дная организа́ция по́мощи борца́м револю́ции'' - Mezhdunarodnaya organizatsiya pomoshchi bor ...

. On 18 December 1933, Bierut was arrested and in 1935 sentenced to seven years in prison. In 1936, while imprisoned, he was excluded ''in absentia'' from the KPP for an "unworthy of a communist behavior during the investigation and the court trial". The decision was invalidated and reversed by the Comintern on 7 September 1940 (even though the KPP by that time no longer existed). Bierut was found to have been a member of the moderate "majority" faction of the KPP, and the factional infighting in which he participated was determined not to amount to acting against the party.

He was released from prison on 20 December 1938, based on an earlier amnesty. He lived with his wife and children and worked in Warsaw cooperatives until the outbreak of war. The "Sanation

Sanation ( pl, Sanacja, ) was a Polish political movement that was created in the interwar period, prior to Józef Piłsudski's May 1926 ''Coup d'État'', and came to power in the wake of that coup. In 1928 its political activists would go on ...

" prison may have saved his life: while he was incarcerated, the KPP was disbanded by the Comintern and most of its leaders murdered in Stalin's purges.

In the Soviet Union

On 1 September 1939,Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

attacked Poland. On 6 September the Polish military command issued a radio appeal for all able-bodied men to head east;

Bierut left Warsaw for Lublin, from where he proceeded to Kovel

Kovel (, ; pl, Kowel; yi, קאוולע / קאוולי ) is a city in Volyn Oblast (province), in northwestern Ukraine. It serves as the administrative center of Kovel Raion (district). Population:

Kovel gives its name to one of the oldest runi ...

. Eastern Poland was soon occupied by the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

and Bierut was about to spend a part of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

. Form early October, he was employed by the Soviets in political capacities, including vice-chairmanship of a regional election commission before the Elections to the People's Assemblies of Western Ukraine and Western Belorussia. The two assemblies, once established, voted for the incorporation of the previously Polish territories into the respective Soviet republics.Jerzy Eisler, ''Siedmiu wspaniałych. Poczet pierwszych sekretarzy KC PZPR'' he Magnificent Seven: first secretaries of the PZPR pp. 48–56.

Bierut spent the rest of 1939, 1940 and the first part of 1941 in the Soviet Union, in Kiev

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the List of European cities by populat ...

and Moscow, working, making efforts to sanitize his record as a communist and searching for Fornalska, whom he met in Moscow in July 1940 and again in May 1941 in Białystok

Białystok is the largest city in northeastern Poland and the capital of the Podlaskie Voivodeship. It is the tenth-largest city in Poland, second in terms of population density, and thirteenth in area.

Białystok is located in the Białystok Up ...

, where she had moved with Aleksandra. The mother and daughter were evacuated to Yershov in the Soviet Union after the June 1941 outbreak of the Soviet-German war

The Eastern Front of World War II was a theatre of conflict between the European Axis powers against the Soviet Union (USSR), Poland and other Allies, which encompassed Central Europe, Eastern Europe, Northeast Europe (Baltics), and Sou ...

, but Bierut ended up in Minsk

Minsk ( be, Мінск ; russian: Минск) is the capital and the largest city of Belarus, located on the Svislach and the now subterranean Niamiha rivers. As the capital, Minsk has a special administrative status in Belarus and is the admi ...

. From November 1941, he was employed there by the German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

occupation authorities as a manager in the trade and food distribution department of the city government. In the summer of 1943, Bierut arrived in Nazi-occupied Poland, likely dispatched there as a trusted Soviet operative. He came to join the leadership of the Polish Workers' Party

The Polish Workers' Party ( pl, Polska Partia Robotnicza, PPR) was a communist party in Poland from 1942 to 1948. It was founded as a reconstitution of the Communist Party of Poland (KPP) and merged with the Polish Socialist Party (PPS) in 1948 ...

(PPR), a new communist party founded in January 1942. He may have been recommended for the job by Fornalska; parachuted into the General Government

The General Government (german: Generalgouvernement, pl, Generalne Gubernatorstwo, uk, Генеральна губернія), also referred to as the General Governorate for the Occupied Polish Region (german: Generalgouvernement für die be ...

in the spring of 1942, she was in charge of the PPR's radio communications with Moscow. Bierut became a member of the party Secretariat on 23 November 1943.

While there are many accounts and stories relating to Bierut during the 1939–1943 period, not much is known with certainty about his activities and the accounts are often speculative or amount to hearsay.

In occupied Poland from 1943

Upon his arrival in Warsaw, Bierut became a member of the Central Committee of the PPR, which comprised several individuals. The Secretariat had three members: General SecretaryPaweł Finder

Paweł Finder (; born as ''Pinkus Finder''; pseudonyms: ''Paul Finder'', ''Paul Reynot''; 19 September 1904 – 26 July 1944) was a Polish Communist leader and First Secretary of the Polish Workers' Party (PPR) from 1943 to 1944.Dia–pozytywPa ...

, Franciszek Jóźwiak and Władysław Gomułka

Władysław Gomułka (; 6 February 1905 – 1 September 1982) was a Polish communist politician. He was the ''de facto'' leader of post-war Poland from 1947 until 1948. Following the Polish October he became leader again from 1956 to 1970. Go ...

, whom Bierut did not know, but who quickly became his principal rival. Bierut lost his first confrontation over the management of ''Trybuna Wolności'' ('The Tribune of Freedom'), the party's press organ.Jerzy Eisler, ''Siedmiu wspaniałych. Poczet pierwszych sekretarzy KC PZPR'' he Magnificent Seven: first secretaries of the PZPR pp. 56–59.

In a major blow to the re-emergent Polish communist party, Finder and Fornalska were arrested by the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one organi ...

on 14 November 1943. They were executed in July 1944. They were the only people with the knowledge of radio codes needed to communicate with Moscow and such communications were indeed interrupted for several months. On 23 November 1943, the PPR chose Gomułka as its general secretary.

However, on 31 December 1943, Bierut also assumed an important (as it turned out) office: chairmanship of the State National Council

Krajowa Rada Narodowa in Polish (translated as State National Council or Homeland National Council, abbreviated to KRN) was a parliament-like political body created during the later stages of World War II in German-occupied Warsaw, Poland. It wa ...

(''Krajowa Rada Narodowa'', KRN), a communist-led body established by Gomułka and the PPR. The KRN was declared to be a wartime parliament of Poland and some splinter socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

and agrarian activists were co-opted. Starting with the KRN post, with Gomułka and others, Bierut would play a leading role in the establishment of communist Poland.Jerzy Eisler

Jerzy Krzysztof Eisler (born 12 June 1952 in Warsaw) is a Polish historian, focusing mostly on the history of Poland during the communist era. He is a professor at the History Institute of the Polish Academy of Sciences, and member of the Institut ...

, ''Siedmiu wspaniałych. Poczet pierwszych sekretarzy KC PZPR'' he Magnificent Seven: first secretaries of the PZPR pp. 17, 48–82.

In May 1944, the KRN delegation flew into Moscow. They were officially received at the Kremlin

The Kremlin ( rus, Московский Кремль, r=Moskovskiy Kreml', p=ˈmɐˈskofskʲɪj krʲemlʲ, t=Moscow Kremlin) is a fortified complex in the center of Moscow founded by the Rurik dynasty, Rurik dynasty. It is the best known of th ...

by Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

; supremacy of the KRN was recognized by the Union of Polish Patriots

Union of Polish Patriots (''Society of Polish Patriots'', pl, Związek Patriotów Polskich, ZPP, russian: Союз Польских Патриотов, СПП) was a political body created by Polish communists in the Soviet Union in 1943. The ...

, which operated in the Soviet Union under communist leadership.

In June 1944 Bierut wrote a letter, meant for the Soviet leadership and addressed to Georgi Dimitrov

Georgi Dimitrov Mihaylov (; bg, Гео̀рги Димитро̀в Миха̀йлов), also known as Georgiy Mihaylovich Dimitrov (russian: Гео́ргий Миха́йлович Дими́тров; 18 June 1882 – 2 July 1949), was a Bulgarian ...

in Moscow. He accused his Polish communist rival Gomułka of dictatorial tendencies and numerous offenses contrary to communist orthodoxy; if taken seriously, the accusations could have cost Gomułka his life. But they were not and Gomułka did not find out about the letter until 1948, when it was used against him in Poland.

In July 1944, the Polish Committee of National Liberation

The Polish Committee of National Liberation (Polish: ''Polski Komitet Wyzwolenia Narodowego'', ''PKWN''), also known as the Lublin Committee, was an executive governing authority established by the Soviet-backed communists in Poland at the lat ...

(PKWN) was established in liberated Lublin province. Just before the outbreak of the Warsaw Uprising

The Warsaw Uprising ( pl, powstanie warszawskie; german: Warschauer Aufstand) was a major World War II operation by the Polish resistance movement in World War II, Polish underground resistance to liberate Warsaw from German occupation. It occ ...

, on 31 July 1944, Bierut came to Świder. The next day he crossed the front line and arrived in Lublin, the seat of the PKWN.

In Soviet-dominated Poland

Continuing as the KRN president, from August 1944 Bierut was secretly a member of the newly created

Continuing as the KRN president, from August 1944 Bierut was secretly a member of the newly created Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the executive committee for communist parties. It is present in most former and existing communist states.

Names

The term "politburo" in English comes from the Russian ''Politbyuro'' (), itself a contraction ...

of the PPR; he was officially presented to the public as a nonpartisan

Nonpartisanism is a lack of affiliation with, and a lack of bias towards, a political party.

While an Oxford English Dictionary definition of ''partisan'' includes adherents of a party, cause, person, etc., in most cases, nonpartisan refers sp ...

politician.Jerzy Eisler, ''Siedmiu wspaniałych. Poczet pierwszych sekretarzy KC PZPR'' he Magnificent Seven: first secretaries of the PZPR pp. 59–71.

After the outbreak of the Warsaw Uprising, Bierut arrived in Moscow. On 6–7 August 1944, together with Wanda Wasilewska

ukr, Ванда Львівна Василевська rus, Ванда Львовна Василевская

, native_name_lang =

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Kraków, Austria-Hungary

, death_date =

, death_place ...

and Michał Rola-Żymierski

Michał Rola-Żymierski (; 4 September 189015 October 1989) was a Polish high-ranking Communist Party leader, communist military commander and NKVD secret agent. He was appointed as Marshal of Poland by Joseph Stalin, and served in this position ...

, he conducted negotiations with Prime Minister Stanisław Mikołajczyk

Stanisław Mikołajczyk (18 July 1901 – 13 December 1966; ) was a Polish politician. He was a Prime Minister of the Polish government in exile during World War II, and later Deputy Prime Minister in post-war Poland until 1947.

Biography Back ...

of the Polish government-in-exile

The Polish government-in-exile, officially known as the Government of the Republic of Poland in exile ( pl, Rząd Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej na uchodźstwie), was the government in exile of Poland formed in the aftermath of the Invasion of Pola ...

. Mikołajczyk refused their offer of the job of prime minister in a coalition government, which otherwise would be dominated by the communists.Czesław Brzoza, Andrzej Leon Sowa, ''Historia Polski 1918–1945'' istory of Poland: 1918–1945 pp. 545–546. Kraków 2009, Wydawnictwo Literackie

Wydawnictwo Literackie (abbreviated WL, lit. "Literary Press") is a Kraków-based Polish publishing house, which has been referred to as one of Poland's "most respected".

Company history

Since its foundation in 1953, Wydawnictwo Literackie has ...

, . Bierut's daughter Krystyna participated in the uprising as a soldier of ''Armia Ludowa

People's Army (Polish: ''Armia Ludowa'' , abbriv.: AL) was a communist Soviet-backed partisan force set up by the communist Polish Workers' Party ('PR) during World War II. It was created on the order of the Polish State National Council on 1 Ja ...

'' and was gravely wounded.

A KRN and PKWN delegation, led by Bierut, was summoned to Moscow, where it stayed from 28 September to 3 October. Stalin, assisted by Wasilewska, had two meetings with the leaders from Poland, during which he lectured them on a number of issues, but was especially displeased by the lack of progress in implementing the land reform

Land reform is a form of agrarian reform involving the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution, generally of agricultural ...

decree passed by the PKWN on 6 September. Stalin urged them to proceed forcefully with the agrarian revolution and to eliminate the great land owners class without further delay or undue legal concerns; Bierut felt that the remarks were addressed to him in particular.

On 12 October, the anniversary of the Battle of Lenino

The Battle of Lenino was a tactical World War II engagement that took place on 12 and 13 October 1943, north of the village of Lenino in the Mogilev region of Byelorussia. The battle itself was a part of a larger Soviet Spas-Demensk offensi ...

, the KRN for the first time deliberated in Lublin. The proceedings were interrupted to allow the deputies (including Bierut), together with officials of the PKWN and Nikolai Bulganin

Nikolai Alexandrovich Bulganin (russian: Никола́й Алекса́ндрович Булга́нин; – 24 February 1975) was a Soviet politician who served as Minister of Defense (1953–1955) and Premier of the Soviet Union (1955–1 ...

representing the Soviet Union, to participate in a field mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different elementar ...

celebrated for the occasion and in the military parade that followed. Such participation in religious ceremonies by leading communist politicians continued for a while; it was one of the manifestations of the officially proclaimed after the war democratic and pluralistic policies, which included preservation of religious freedoms. Marshal Rola-Żymierski recalled kneeling together with Bierut before the altar at another field mass in May 1946, on the first anniversary of World War II victory. In conversations with Stanisław Łukasiewicz, his press secretary, Bierut expressed his support for moderate and liberal policies. His personal views were anti-clerical

Anti-clericalism is opposition to religious authority, typically in social or political matters. Historical anti-clericalism has mainly been opposed to the influence of Roman Catholicism. Anti-clericalism is related to secularism, which seeks to ...

and he thought the reform proposals put forward by Mikołajczyk's Polish People's Party

The Polish People's Party ( pl, Polskie Stronnictwo Ludowe, PSL) is an agrarian political party in Poland. It is currently led by Władysław Kosiniak-Kamysz.

Its history traces back to 1895, when it held the name People's Party, although it ...

(PSL), the legally existing opposition, would be abandoned in the event of PSL victory.

A military department of the PPR Central Committee was created on 31 October 1944 and included Bierut and Gomułka, in addition to three generals. Its goal was to politicize the armed forces, currently fighting the war, and to establish a politically reliable officer corps. According to Eisler, Bierut and Gomułka are both responsible for the post-war persecution of many former

A military department of the PPR Central Committee was created on 31 October 1944 and included Bierut and Gomułka, in addition to three generals. Its goal was to politicize the armed forces, currently fighting the war, and to establish a politically reliable officer corps. According to Eisler, Bierut and Gomułka are both responsible for the post-war persecution of many former Home Army

The Home Army ( pl, Armia Krajowa, abbreviated AK; ) was the dominant resistance movement in German-occupied Poland during World War II. The Home Army was formed in February 1942 from the earlier Związek Walki Zbrojnej (Armed Resistance) esta ...

soldiers and other groups and individuals. The terror policies, particularly brutal in the 1944–48 period, were directed against declared opponents of the regime, including the legally functioning PSL, and had nor yet involved society as a whole.Jerzy Eisler, ''Siedmiu wspaniałych. Poczet pierwszych sekretarzy KC PZPR'' he Magnificent Seven: first secretaries of the PZPR pp. 75–82.

In February 1945, the Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference (codenamed Argonaut), also known as the Crimea Conference, held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the post ...

took place in Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a pop ...

. At that time Bierut, together with the PPR leadership and government departments, moved to the capital city of Warsaw. The city was in ruins and its rebuilding and expansion became a major concern and preoccupation for Bierut during the years that followed.

In June 1945, the Provisional Government of National Unity

The Provisional Government of National Unity ( pl, Tymczasowy Rząd Jedności Narodowej - TRJN) was a puppet government formed by the decree of the State National Council () on 28 June 1945 as a result of reshuffling the Soviet-backed Provisional ...

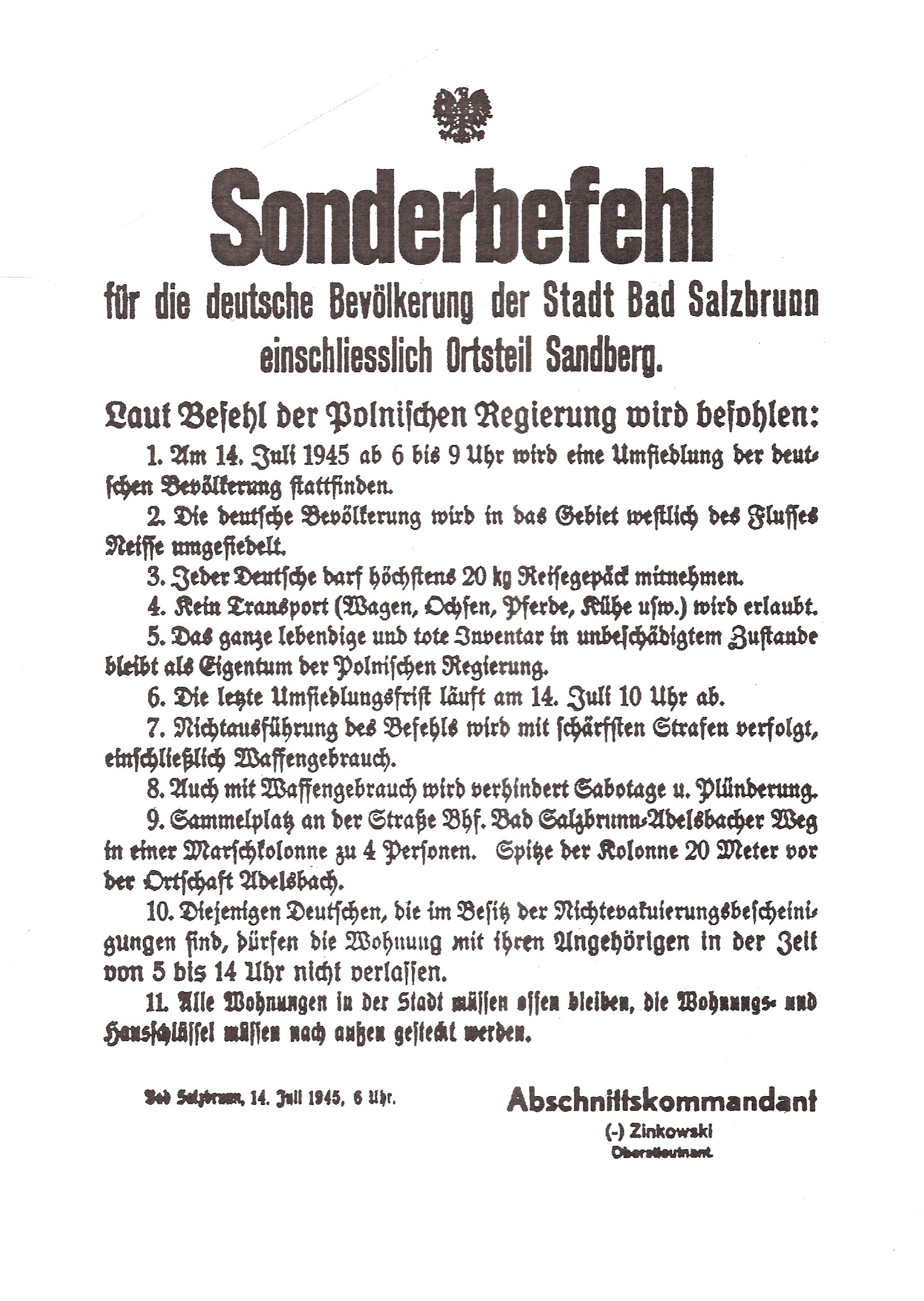

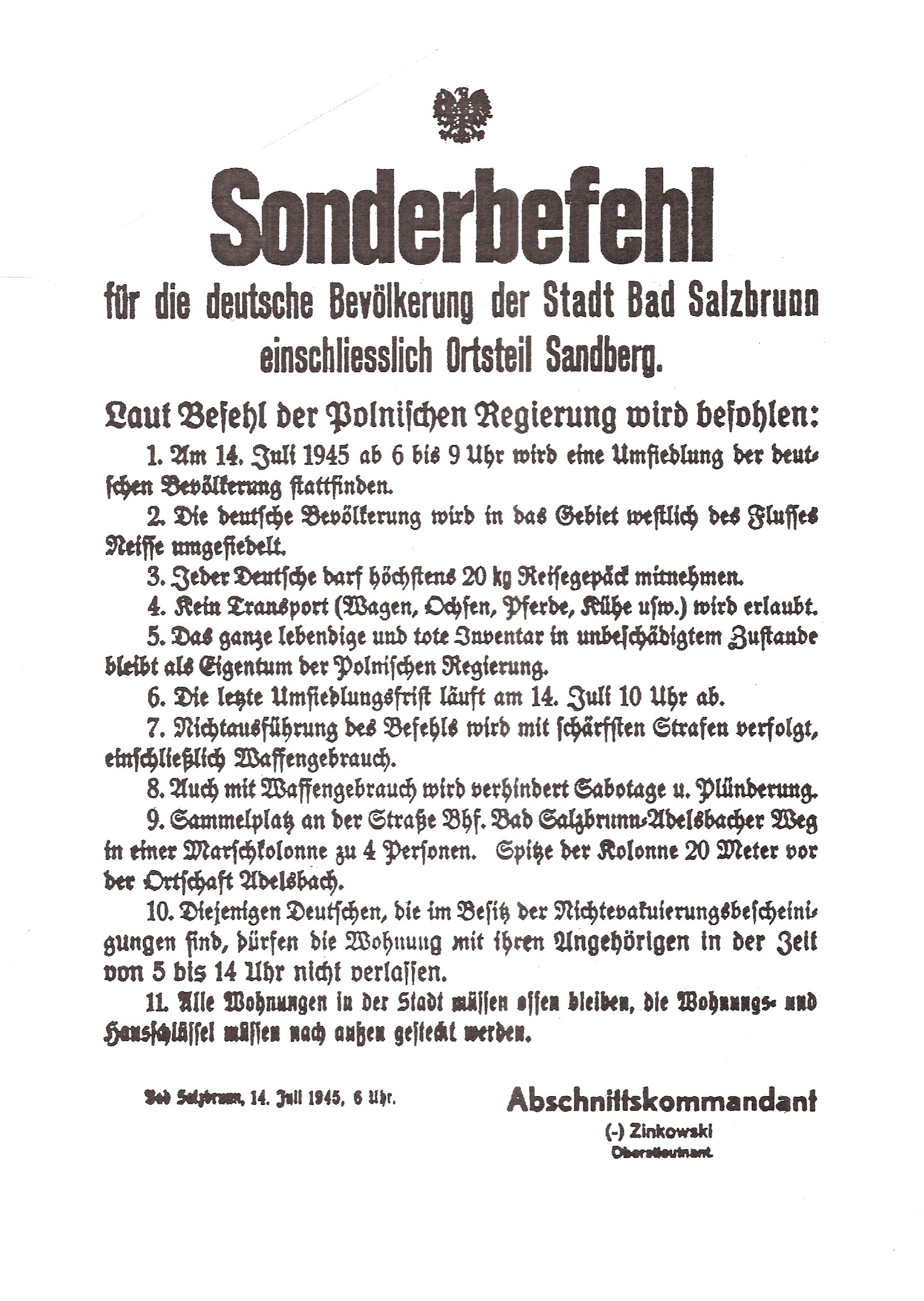

was established in Moscow. In July, Bierut and other Polish leaders participated in the Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference (german: Potsdamer Konferenz) was held at Potsdam in the Soviet occupation zone from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to allow the three leading Allies to plan the postwar peace, while avoiding the mistakes of the Paris Pe ...

, where, together with Stalin, they successfully lobbied for the establishment of Poland's western border at the Oder–Neisse line

The Oder–Neisse line (german: Oder-Neiße-Grenze, pl, granica na Odrze i Nysie Łużyckiej) is the basis of most of the international border between Germany and Poland from 1990. It runs mainly along the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers a ...

. The Polish administration in the formerly German lands was to continue until the final delimitation of the frontier in the (future) peace settlement.Halik Kochanski

Halik Kochanski (born 19 April 1962) is a British historian and writer of Polish origin.

Life

Kochanski was educated at Downside School and at Balliol College, Oxford, where she was awarded an M.A. in Modern History. She obtained her Ph.D from ...

(2012). The Eagle Unbowed: Poland and the Poles in the Second World War, pp. 537–541. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. . Poland's newly acquired "Recovered Territories

The Recovered Territories or Regained Lands ( pl, Ziemie Odzyskane), also known as Western Borderlands ( pl, Kresy Zachodnie), and previously as Western and Northern Territories ( pl, Ziemie Zachodnie i Północne), Postulated Territories ( pl, Z ...

" had thus reached their maximum attainable size.

Referendum and election, Bierut's presidency

On 30 June 1946, the Polish people's referendum took place. It was done in preparation for the

On 30 June 1946, the Polish people's referendum took place. It was done in preparation for the Yalta

Yalta (: Я́лта) is a resort city on the south coast of the Crimean Peninsula surrounded by the Black Sea. It serves as the administrative center of Yalta Municipality, one of the regions within Crimea. Yalta, along with the rest of Crimea ...

-mandated national elections; affirmative answers to the three questions given were supposed to demonstrate public support for the issues promoted by the communists. The results were falsified.Jerzy Eisler, ''Siedmiu wspaniałych. Poczet pierwszych sekretarzy KC PZPR'' he Magnificent Seven: first secretaries of the PZPR pp. 71–75.

On 22 September 1946, the KRN passed the electoral rules and in November set the date; the delayed legislative elections

A general election is a political voting election where generally all or most members of a given political body are chosen. These are usually held for a nation, state, or territory's primary legislative body, and are different from by-elections ( ...

were held on 19 January 1947. The PPR-led coalition, running as the Democratic Bloc, was opposed by Mikołajczyk's PSL. The campaign was conducted in an atmosphere of terror and intimidation. Over 80% of the vote was falsely reported to have been cast for the Democratic Bloc and the PSL was practically eliminated as the legal opposition.

The newly elected ''Sejm

The Sejm (English: , Polish: ), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland (Polish: ''Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), is the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of t ...

'' convened on 4 February 1947 and on the following day it elected Bierut President of the Republic of Poland

The president of Poland ( pl, Prezydent RP), officially the president of the Republic of Poland ( pl, Prezydent Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej), is the head of state of Poland. Their rights and obligations are determined in the Constitution of Polan ...

. The installation ceremony was done in a traditional format and ended with the new president uttering the words "so help me God".

Polish Radio

Polskie Radio Spółka Akcyjna (PR S.A.; English: Polish Radio) is Poland's national public-service radio broadcasting organization owned by the State Treasury of Poland.

History

Polskie Radio was founded on 18 August 1925 and began making ...

broadcasting station in Wrocław

Wrocław (; german: Breslau, or . ; Silesian German: ''Brassel'') is a city in southwestern Poland and the largest city in the historical region of Silesia. It lies on the banks of the River Oder in the Silesian Lowlands of Central Europe, rou ...

, President Bierut made a speech entitled ''For the dissemination of culture''. "The artistic and cultural creative process should reflect the great breakthrough that the nation is experiencing. It should, but so far it isn't", he said. Bierut called for greater centralization and planning in culture and art, which, according to him, should form, educate and engross society. The speech was a harbinger of the upcoming norm of socialist realism

Socialist realism is a style of idealized realistic art that was developed in the Soviet Union and was the official style in that country between 1932 and 1988, as well as in other socialist countries after World War II. Socialist realism is ch ...

in Poland.

Sometimes, Bierut on his own undertook special interventions with Stalin. He repeatedly and at different times asked Stalin and Lavrentiy Beria

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria (; rus, Лавре́нтий Па́влович Бе́рия, Lavréntiy Pávlovich Bériya, p=ˈbʲerʲiə; ka, ლავრენტი ბერია, tr, ; – 23 December 1953) was a Georgian Bolshevik ...

about the whereabouts of the missing Polish communists (former members of the disbanded KPP), many of whom were murdered in the Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Nikolay Yezhov, Yezhov'), was General ...

in the 1930s, but others may have survived. He also kept looking for the missing family of Fornalska.Lucyna Tychowa and Andrzej Romanowski, ''Tak, jestem córką Jakuba Bermana'' es, I'm the Daughter of Jakub Berman pp. 64–65. UNIVERSITAS, Kraków 2016, . While Stalin and Beria discouraged and ridiculed Bierut's efforts, in some cases his exertions brought positive results. Besides the communists, mostly surviving women, Bierut was able to bring back to Poland many other Poles, including former Home Army soldiers exiled in the Soviet Union.Lucyna Tychowa and Andrzej Romanowski, ''Tak, jestem córką Jakuba Bermana'' es, I'm the Daughter of Jakub Berman pp. 115–117.

Bierut was a gallant man, well-liked by women. His wife Janina did not live with him and was not known to many of his associates. She occasionally visited him in his offices and seemed intimidated by the surroundings and her husband's position. On the other hand, his son and two daughters had seen Bierut frequently; they spent with him holidays and vacations and he appeared to genuinely enjoy their company. Bierut's actual female partner, after Fornalska's arrest, was Wanda Górska. She worked as his secretary and in other capacities, controlled access to him and visitors often thought of her as Bierut's wife.

Top leader of Stalinist Poland

Gomułka, general secretary of the PPR (and until that time the principal figure in post-war Polish communist establishment), was accused of a "right-wing nationalistic deviation" and removed from his position during a plenary meeting of the Central Committee in August 1948. The move was Stalin-orchestrated and Stalin's choice to fill the vacated job was President Bierut, who had thus become both the top party leader and top state official.

The historic PPS was practically taken over by the PPR at the Unification Congress, held in Warsaw in December 1948. The resulting "

Gomułka, general secretary of the PPR (and until that time the principal figure in post-war Polish communist establishment), was accused of a "right-wing nationalistic deviation" and removed from his position during a plenary meeting of the Central Committee in August 1948. The move was Stalin-orchestrated and Stalin's choice to fill the vacated job was President Bierut, who had thus become both the top party leader and top state official.

The historic PPS was practically taken over by the PPR at the Unification Congress, held in Warsaw in December 1948. The resulting "Marxist–Leninist

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialect ...

" Polish United Workers' Party

The Polish United Workers' Party ( pl, Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza; ), commonly abbreviated to PZPR, was the communist party which ruled the Polish People's Republic as a one-party state from 1948 to 1989. The PZPR had led two other lega ...

(PZPR) was nearly synonymous with the state and Bierut became its first general secretary. The Three-Year Plan

The Plan of Reconstructing the Economy ( pl, Plan Odbudowy Gospodarki), commonly known as the Three-Year Plan ( pl, plan trzyletni) was a central planning, centralized Soviet plan, plan created by the Polish communist government to rebuild History ...

of post-war rebuilding and economic consolidation ended in 1949 and was followed by the Six-Year Plan, which intensified the industrialisation

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econo ...

process and brought extensive urbanization

Urbanization (or urbanisation) refers to the population shift from rural to urban areas, the corresponding decrease in the proportion of people living in rural areas, and the ways in which societies adapt to this change. It is predominantly t ...

of Poland.

In November 1949, Bierut asked the Soviet government to make available Marshal Konstantin Rokossovsky

Konstantin Konstantinovich (Xaverevich) Rokossovsky (Russian: Константин Константинович Рокоссовский; pl, Konstanty Rokossowski; 21 December 1896 – 3 August 1968) was a Soviet and Polish officer who becam ...

, a Polish-Soviet politician and famous World War II commander, for service in the government of Poland. Rokossovsky subsequently became a Marshal of Poland

Marshal of Poland ( pl, Marszałek Polski) is the highest rank in the Polish Army. It has been granted to only six officers. At present, Marshal is equivalent to a Field Marshal or General of the Army (OF-10) in other NATO armies.

History

To ...

and Minister of National Defense

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in som ...

.

In early August 1951, Bierut had his main rival Gomułka and his wife arrested. Gomułka, though imprisoned, refused to cooperate with his accusers and displayed remarkable ability to defend himself, while Bierut's people bungled the prosecution. According to

In early August 1951, Bierut had his main rival Gomułka and his wife arrested. Gomułka, though imprisoned, refused to cooperate with his accusers and displayed remarkable ability to defend himself, while Bierut's people bungled the prosecution. According to Edward Ochab

Edward Ochab (; 16 August 1906 – 1 May 1989) was a Polish communist politician and top leader of Poland between March and October 1956.

As a member of the Communist Party of Poland from 1929, he was repeatedly imprisoned for his activities u ...

, though, Stalin and Beria ordered the arrest and trial of Gomułka, while Bierut and Jakub Berman

Jakub Berman (23 December 1901 – 10 April 1984) was a Polish communist politician. Was born in Jewish family, son of Iser and Guta. An activist during the Second Polish Republic, in post-war communist Poland he was a member of the Politburo ...

tried to protect him and caused delays in the proceedings.Jerzy Eisler, ''Siedmiu wspaniałych. Poczet pierwszych sekretarzy KC PZPR'' he Magnificent Seven: first secretaries of the PZPR pp. 115–116. Informal political reforms, slow to take hold after Stalin's death, eventually materialized and in December 1954 Gomułka was released.

During the lifetime of Stalin, Bierut was strictly subservient to the Soviet leader. Bierut routinely received instructions from Stalin over the telephone or was summoned to Moscow for consultations.Jerzy Eisler, ''Siedmiu wspaniałych. Poczet pierwszych sekretarzy KC PZPR'' he Magnificent Seven: first secretaries of the PZPR pp. 24–25. Bierut still had far more power in Poland than any of his successors as First Secretary of the PZPR. He ruled jointly with his two closest associates, Berman and Hilary Minc

Hilary Minc (24 August 1905, Kazimierz Dolny – 26 November 1974, Warsaw) was a Polish economist and communist politician prominent in Stalinist Poland.

Minc was born into a middle class Jewish family; his parents were Oskar Minc and Stefa ...

.Jerzy Eisler, ''Siedmiu wspaniałych. Poczet pierwszych sekretarzy KC PZPR'' he Magnificent Seven: first secretaries of the PZPR pp. 31–38. Security issues, including the widespread persecution of opposition, he also consulted with Stanisław Radkiewicz

Stanisław Radkiewicz (; 19 January 1903 – 13 December 1987) was a Poles, Polish communist activist with Soviet Union, Soviet citizenship, a member of the pre-war Communist Party of Poland and of the post-war Polish United Workers' Party (PZP ...

, head of the Ministry of Public Security.

Bierut's 60th birthday, constitution of the Polish People's Republic

The apogee of Bierut's

The apogee of Bierut's cult

In modern English, ''cult'' is usually a pejorative term for a social group that is defined by its unusual religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs and rituals, or its common interest in a particular personality, object, or goal. This ...

, promoted by the authorities over a number of years, was the celebration of his sixtieth birthday on 18 April 1952. It included various industrial and other production or accomplishment commitments undertaken by institutions and individuals. The University of Wrocław

, ''Schlesische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Breslau'' (before 1945)

, free_label = Specialty programs

, free =

, colors = Blue

, website uni.wroc.pl

The University of Wrocław ( pl, Uniwersytet Wrocławski, U ...

and some state enterprises were named in his honor. The History Department of the party's Central Committee prepared a special book about Bierut and his life, while Polish poets, including some notable ones, generated a book of poems dedicated to the leader. Many postage stamp

A postage stamp is a small piece of paper issued by a post office, postal administration, or other authorized vendors to customers who pay postage (the cost involved in moving, insuring, or registering mail), who then affix the stamp to the fa ...

s dedicated to Bierut were issued.Jerzy Eisler, ''Siedmiu wspaniałych. Poczet pierwszych sekretarzy KC PZPR'' he Magnificent Seven: first secretaries of the PZPR pp. 82–85.

As the PZPR leadership felt ready to sanction its rule in a fundamental legal document, a new constitution was being worked on. On 26 May 1951, the ''Sejm'' passed a statute concerning the preparation and passing of the constitution. The Constitutional Committee, led by Bierut, commenced its deliberations on 19 September. In the fall of 1951, a Russian translation of the draft constitution was examined by Stalin, who inserted dozens of corrections, subsequently implemented in the Polish text by Bierut. The officially proclaimed national public discussion resulted in hundreds of other proposed changes. After all the delays and the necessary extension of the term of the ''Sejm'', the Constitution of the Polish People's Republic

The Constitution of the Polish People's Republic (also known as the July Constitution or the Constitution of 1952) was a supreme law passed in communist-ruled Poland on 22 July 1952. It superseded the post-World War II provisional Small Cons ...

was officially proclaimed on 22 July 1952.

The Polish People's Republic

The Polish People's Republic ( pl, Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa, PRL) was a country in Central Europe that existed from 1947 to 1989 as the predecessor of the modern Republic of Poland. With a population of approximately 37.9 million nea ...

(''Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa'') was the new name of the state. The ''Sejm'' was designated as the highest national authority; it represented "the working people of towns and villages". The office of the president was eliminated and replaced with the collegial Council of State

A Council of State is a governmental body in a country, or a subdivision of a country, with a function that varies by jurisdiction. It may be the formal name for the cabinet or it may refer to a non-executive advisory body associated with a head o ...

, elected by the ''Sejm'' from its members. The first chairman of the new council was Aleksander Zawadzki. Bierut replaced Józef Cyrankiewicz

Józef Adam Zygmunt Cyrankiewicz (; 23 April 1911 – 20 January 1989) was a Polish Socialist (PPS) and after 1948 Communist politician. He served as premier of the Polish People's Republic between 1947 and 1952, and again for 16 years between ...

as prime minister in November 1952. The constitution, amended many times, remained in force until a new Constitution of Poland

The current Constitution of Poland was founded on 2 April 1997. Formally known as the Constitution of the Republic of Poland ( pl, Konstytucja Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej), it replaced the Small Constitution of 1992, the last amended version of ...

came into effect in October 1997, in what was then the Republic of Poland.

Bierut's last years

In March 1953, Bierut led the Polish delegation for Stalin's funeral in Moscow.Jerzy Eisler, ''Siedmiu wspaniałych. Poczet pierwszych sekretarzy KC PZPR'' he Magnificent Seven: first secretaries of the PZPR pp. 85–88.

The regime's relations with the

In March 1953, Bierut led the Polish delegation for Stalin's funeral in Moscow.Jerzy Eisler, ''Siedmiu wspaniałych. Poczet pierwszych sekretarzy KC PZPR'' he Magnificent Seven: first secretaries of the PZPR pp. 85–88.

The regime's relations with the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

kept deteriorating. The authorities imprisoned Bishop Czesław Kaczmarek and interned Poland's primate

Primates are a diverse order of mammals. They are divided into the strepsirrhines, which include the lemurs, galagos, and lorisids, and the haplorhines, which include the tarsiers and the simians (monkeys and apes, the latter including huma ...

, Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński

Stefan Wyszyński (3 August 1901 – 28 May 1981) was a Polish prelate of the Catholic Church. He served as the bishop of Lublin from 1946 to 1948, archbishop of Warsaw and archbishop of Gniezno from 1948 to 1981. He was created a cardinal on ...

.

In the Soviet Union, changes were initiated by the new leader of the communist party, Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

. The "collective leadership" concept, promoted first in the Soviet Union, made its way to other communist countries, including Poland. It meant, among other things, giving top party and state functions to different officials.

The Second Congress of the PZPR deliberated from 10 to 17 March 1954 in Warsaw. Bierut's party chief's title was changed from general secretary to first secretary. Because of the separation of functions requirement, Bierut remained only a party secretary and Cyrankiewicz returned to the post of prime minister. The Six-Year Plan was modified and some of the heavy industrial investment resources were shifted toward production of consumer articles.

When Khrushchev, a guest at the congress, inquired about the reasons for the continuing imprisonment of Gomułka, Bierut professed his own ignorance on that issue.

Death and funeral

The

The 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was held during the period 14–25 February 1956. It is known especially for First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev's "Secret Speech", which denounced the personality cult and dictatorship ...

deliberated on 14–25 February 1956. Afterwards, Bierut did not return to Poland with the rest of the Polish delegation, but remained in Moscow, hospitalized with bad influenza

Influenza, commonly known as "the flu", is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These symptoms ...

, which turned into pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severity ...

and heart complications.Jerzy Eisler, ''Siedmiu wspaniałych. Poczet pierwszych sekretarzy KC PZPR'' he Magnificent Seven: first secretaries of the PZPR pp. 88–93.