Battle Of The Bismarck Sea on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

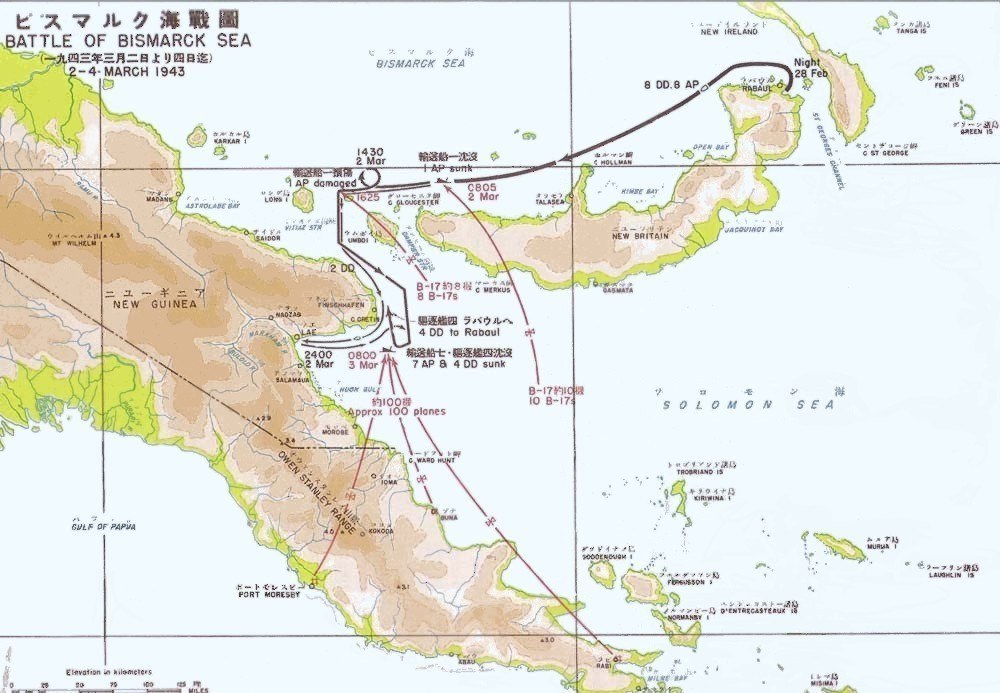

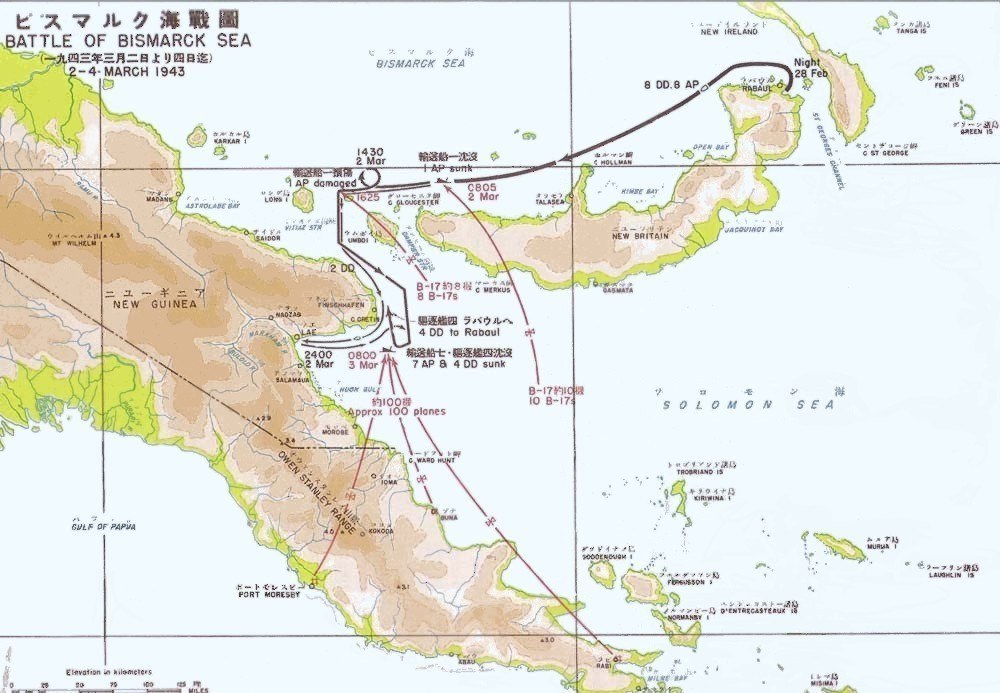

The Battle of the Bismarck Sea (2–4 March 1943) took place in the

On 5 January 1943, the convoy, which consisted of five destroyers and five troop transports carrying Okabe's force, set out for Lae from Rabaul. Forewarned by

On 5 January 1943, the convoy, which consisted of five destroyers and five troop transports carrying Okabe's force, set out for Lae from Rabaul. Forewarned by

The destroyers carried 958 troops while the transports took 5,954. All the ships were combat loaded to expedite unloading at Lae. The commander of the Japanese XVIII Army – Lieutenant General Hatazō Adachi – travelled on the destroyer , while that of the 51st Division – Lieutenant General

The destroyers carried 958 troops while the transports took 5,954. All the ships were combat loaded to expedite unloading at Lae. The commander of the Japanese XVIII Army – Lieutenant General Hatazō Adachi – travelled on the destroyer , while that of the 51st Division – Lieutenant General

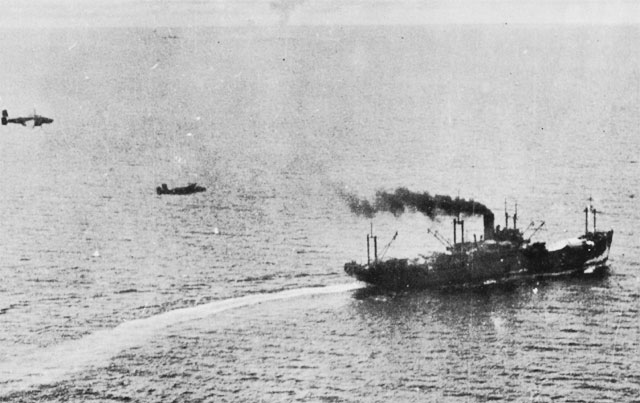

The 13 Beaufighters from No. 30 Squadron RAAF approached the convoy at low level to give the impression they were Beauforts making a torpedo attack. The ships turned to face them, the standard procedure to present a smaller target to torpedo bombers, allowing the Beaufighters to maximise the damage they inflicted on the ships' anti-aircraft guns, bridges and crews in

The 13 Beaufighters from No. 30 Squadron RAAF approached the convoy at low level to give the impression they were Beauforts making a torpedo attack. The ships turned to face them, the standard procedure to present a smaller target to torpedo bombers, allowing the Beaufighters to maximise the damage they inflicted on the ships' anti-aircraft guns, bridges and crews in  Fourteen B-25s returned that afternoon, reportedly claiming 17 hits or near misses. By this time, a third of the transports were sunk or sinking. As the Beaufighters and B-25s had expended their munitions, some USAAF A-20 Havocs of the 3rd Attack Group joined in. Another five hits were claimed by B-17s of the 43rd Bombardment Group from higher altitudes. During the afternoon, further attacks from USAAF B-25s and Bostons of No. 22 Squadron RAAF followed.

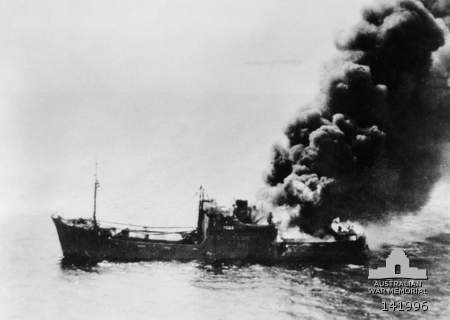

All seven of the transports were hit and most were burning or sinking about south east of

Fourteen B-25s returned that afternoon, reportedly claiming 17 hits or near misses. By this time, a third of the transports were sunk or sinking. As the Beaufighters and B-25s had expended their munitions, some USAAF A-20 Havocs of the 3rd Attack Group joined in. Another five hits were claimed by B-17s of the 43rd Bombardment Group from higher altitudes. During the afternoon, further attacks from USAAF B-25s and Bostons of No. 22 Squadron RAAF followed.

All seven of the transports were hit and most were burning or sinking about south east of  Some 2,700 survivors were taken to Rabaul by the destroyers. On 4 March, another 1,000 or so survivors were adrift on rafts. On the evenings of 3–5 March, PT boats and planes attacked Japanese rescue vessels, as well as the survivors from the sunken vessels on life rafts and swimming or floating in the sea. This was later justified on the grounds that rescued servicemen would have been rapidly landed at their military destination and promptly returned to active service, as well as being retaliation for the Japanese fighter planes attacking survivors of the downed B-17 bomber. While many of the Allied aircrew accepted these attacks as being necessary, others were sickened. On 6 March, the Japanese submarines and picked up 170 survivors. Two days later, ''I-26'' found another 54 and put them ashore at Lae. Hundreds made their way to various islands. One band of 18 survivors landed on

Some 2,700 survivors were taken to Rabaul by the destroyers. On 4 March, another 1,000 or so survivors were adrift on rafts. On the evenings of 3–5 March, PT boats and planes attacked Japanese rescue vessels, as well as the survivors from the sunken vessels on life rafts and swimming or floating in the sea. This was later justified on the grounds that rescued servicemen would have been rapidly landed at their military destination and promptly returned to active service, as well as being retaliation for the Japanese fighter planes attacking survivors of the downed B-17 bomber. While many of the Allied aircrew accepted these attacks as being necessary, others were sickened. On 6 March, the Japanese submarines and picked up 170 survivors. Two days later, ''I-26'' found another 54 and put them ashore at Lae. Hundreds made their way to various islands. One band of 18 survivors landed on

Imamura's chief of staff flew to Imperial General Headquarters to report on the disaster. It was decided that there would be no more attempts to land troops at Lae. The losses incurred in the Bismarck Sea caused grave concern for the security of Lae and Rabaul and resulted in a change of strategy. On 25 March a joint Army-Navy Central Agreement on South West Area Operations gave operations in New Guinea priority over those in the

Imamura's chief of staff flew to Imperial General Headquarters to report on the disaster. It was decided that there would be no more attempts to land troops at Lae. The losses incurred in the Bismarck Sea caused grave concern for the security of Lae and Rabaul and resulted in a change of strategy. On 25 March a joint Army-Navy Central Agreement on South West Area Operations gave operations in New Guinea priority over those in the

Bismarck Convoy Smashed!

Incorporates footage of the battle taken by Damien Parer. {{DEFAULTSORT:Bismarck Sea, Battle of 1943 in Papua New Guinea Battles and operations of World War II involving Papua New Guinea Territory of New Guinea Bismarck Sea Conflicts in 1943 Naval battles of World War II involving Australia Naval battles of World War II involving Japan Naval battles of World War II involving the United States South West Pacific theatre of World War II World War II aerial operations and battles of the Pacific theatre March 1943 events

South West Pacific Area

South West Pacific Area (SWPA) was the name given to the Allied supreme military command in the South West Pacific Theatre of World War II. It was one of four major Allied commands in the Pacific War. SWPA included the Philippines, Borneo, the ...

(SWPA) during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

when aircraft of the U.S. Fifth Air Force

The Fifth Air Force (5 AF) is a numbered air force of the United States Air Force Pacific Air Forces (PACAF). It is headquartered at Yokota Air Base, Japan. It is the U.S. Air Force's oldest continuously serving Numbered Air Force. The organiza ...

and the Royal Australian Air Force

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries = RAAF Anniversary Commemoration ...

(RAAF) attacked a Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

convoy

A convoy is a group of vehicles, typically motor vehicles or ships, traveling together for mutual support and protection. Often, a convoy is organized with armed defensive support and can help maintain cohesion within a unit. It may also be used ...

carrying troops to Lae

Lae () is the capital of Morobe Province and is the second-largest city in Papua New Guinea. It is located near the delta of the Markham River and at the start of the Highlands Highway, which is the main land transport corridor between the Highl ...

, New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu

Hiri Motu, also known as Police Motu, Pidgin Motu, or just Hiri, is a language of Papua New Guinea, which is spoken in surrounding areas of Port Moresby (Capital of Papua New Guinea).

It is a simplified version of ...

. Most of the Japanese task force was destroyed, and Japanese troop losses were heavy.

The Japanese convoy was a result of a Japanese Imperial General Headquarters decision in December 1942 to reinforce their position in the South West Pacific

Oceania (, , ) is a geographical region that includes Australasia, Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Spanning the Eastern and Western hemispheres, Oceania is estimated to have a land area of and a population of around 44.5 million as of ...

. A plan was devised to move some 6,900 troops from Rabaul

Rabaul () is a township in the East New Britain province of Papua New Guinea, on the island of New Britain. It lies about 600 kilometres to the east of the island of New Guinea. Rabaul was the provincial capital and most important settlement in ...

directly to Lae. The plan was understood to be risky, because Allied air power in the area was strong, but it was decided to proceed because otherwise the troops would have to be landed a considerable distance away and march through inhospitable swamp, mountain and jungle terrain without roads before reaching their destination. On 28 February 1943, the convoy – comprising eight destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

s and eight troop transport

A troopship (also troop ship or troop transport or trooper) is a ship used to carry soldiers, either in peacetime or wartime. Troopships were often drafted from commercial shipping fleets, and were unable land troops directly on shore, typicall ...

s with an escort of approximately 100 fighter aircraft

Fighter aircraft are fixed-wing military aircraft designed primarily for air-to-air combat. In military conflict, the role of fighter aircraft is to establish air superiority of the battlespace. Domination of the airspace above a battlefield ...

– set out from Simpson Harbour

Simpson Harbour is a sheltered harbour of Blanche Bay, on the Gazelle Peninsula in the extreme north of New Britain. The harbour is named after Captain Cortland Simpson, who surveyed the bay while in command of in 1872.

The former capital city ...

in Rabaul.

The Allies had detected preparations for the convoy, and naval codebreakers

Cryptanalysis (from the Greek language, Greek ''kryptós'', "hidden", and ''analýein'', "to analyze") refers to the process of analyzing information systems in order to understand hidden aspects of the systems. Cryptanalysis is used to breach C ...

in Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

(FRUMEL Fleet Radio Unit, Melbourne (FRUMEL) was a United States–Australian–British signals intelligence unit, founded in Melbourne, Australia, during World War II. It was one of two major Allied signals intelligence units called Fleet Radio Units in t ...

) and Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, had decrypted and translated messages indicating the convoy's intended destination and date of arrival. The Allied Air Forces had developed new techniques, such as skip bombing

Skip bombing was a low-level bombing technique independently developed by several of the combatant nations in World War II, notably Italy, Australia, Britain, Soviet Union and the United States. It allows an aircraft to attack shipping by skippi ...

, that they hoped would improve the chances of successful air attack on ships. They detected and shadowed the convoy, which came under sustained air attack on 2–3 March 1943. Follow-up attacks by PT boat

A PT boat (short for patrol torpedo boat) was a motor torpedo boat used by the United States Navy in World War II. It was small, fast, and inexpensive to build, valued for its maneuverability and speed but hampered at the beginning of the wa ...

s and aircraft were made on 4 March on life boats and rafts. All eight transports and four of the escorting destroyers were sunk. Of 6,900 troops who were badly needed in New Guinea, only about 1,200 made it to Lae. Another 2,700 were rescued by destroyers and submarines and returned to Rabaul. The Japanese made no further attempts to reinforce Lae by ship, greatly hindering their ultimately unsuccessful efforts to stop Allied offensives in New Guinea.

Background

Allied offensives

Six months after Imperial Japanattacked Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii, j ...

in December 1941, the United States won a strategic victory at the Battle of Midway

The Battle of Midway was a major naval battle in the Pacific Theater of World War II that took place on 4–7 June 1942, six months after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor and one month after the Battle of the Coral Sea. The U.S. Navy under ...

in June 1942. Seizing the strategic initiative, the United States and its Allies landed on Guadalcanal in the southern Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands is an island country consisting of six major islands and over 900 smaller islands in Oceania, to the east of Papua New Guinea and north-west of Vanuatu. It has a land area of , and a population of approx. 700,000. Its capita ...

in August 1942, beginning the Solomon Islands Campaign

The Solomon Islands campaign was a major campaign of the Pacific War of World War II. The campaign began with Japanese landings and occupation of several areas in the British Solomon Islands and Bougainville, in the Territory of New Guinea, du ...

. The battle for Guadalcanal ended in victory for the Allies with the withdrawal of Japanese forces from the island in early February 1943. At the same time, Australian and American forces in New Guinea repelled the Japanese land offensive along the Kokoda Track. Going on the offensive, the Allied forces captured Buna–Gona, destroying Japanese forces in that area.

The ultimate goal of the Allied counter-offensives in New Guinea and the Solomons was to capture the main Japanese base at Rabaul

Rabaul () is a township in the East New Britain province of Papua New Guinea, on the island of New Britain. It lies about 600 kilometres to the east of the island of New Guinea. Rabaul was the provincial capital and most important settlement in ...

on New Britain

New Britain ( tpi, Niu Briten) is the largest island in the Bismarck Archipelago, part of the Islands Region of Papua New Guinea. It is separated from New Guinea by a northwest corner of the Solomon Sea (or with an island hop of Umboi the Dam ...

, later codified as Operation Cartwheel

Operation Cartwheel (1943–1944) was a major military operation for the Allies in the Pacific theatre of World War II. Cartwheel was an operation aimed at neutralising the major Japanese base at Rabaul. The operation was directed by the ...

, and clear the way for the eventual reconquest of the Philippines. Recognising the threat, the Japanese continued to send land, naval, and aerial reinforcements to the area in an attempt to check the Allied advances.

Japanese plans

Reviewing the progress of the Battle of Guadalcanal and theBattle of Buna–Gona

The battle of Buna–Gona was part of the New Guinea campaign in the Pacific Theatre during World War II. It followed the conclusion of the Kokoda Track campaign and lasted from 16 November 1942 until 22 January 1943. The battle was fought by ...

in December 1942, the Japanese faced the prospect that neither could be held. Accordingly, Imperial General Headquarters decided to take steps to strengthen the Japanese position in the South West Pacific

Oceania (, , ) is a geographical region that includes Australasia, Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Spanning the Eastern and Western hemispheres, Oceania is estimated to have a land area of and a population of around 44.5 million as of ...

by sending Lieutenant General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

Jusei Aoki's 20th Division from Korea to Guadalcanal

Guadalcanal (; indigenous name: ''Isatabu'') is the principal island in Guadalcanal Province of Solomon Islands, located in the south-western Pacific, northeast of Australia. It is the largest island in the Solomon Islands by area, and the seco ...

and Lieutenant General Heisuke Abe's 41st Division from China to Rabaul. Lieutenant General Hitoshi Imamura

was a Japanese general who served in the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II, and was subsequently convicted of war crimes.

Early career

A native of Sendai city, Miyagi Prefecture, Imamura's father was a judge. Imamura graduated from t ...

, the commander of the Japanese Eighth Area Army

The was a field army of the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II.

History

The Japanese 8th Area Army was formed on November 16, 1942 under the Southern Expeditionary Army Group for the specific task of opposing landings by Allied forces i ...

at Rabaul, ordered Lieutenant General Hatazō Adachi

was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II.

Early career

Adachi was born into an impoverished family, originally descended from samurai, in Ishikawa Prefecture in 1890 (the 23rd year of the reign of Emperor Meiji, which i ...

's XVIII Army to secure Madang

Madang (old German name: ''Friedrich-Wilhelmshafen'') is the capital of Madang Province and is a town with a population of 27,420 (in 2005) on the north coast of Papua New Guinea. It was first settled by the Germans in the 19th century.

Histor ...

, Wewak

Wewak is the capital of the East Sepik province of Papua New Guinea. It is on the northern coast of the island of New Guinea. It is the largest town between Madang and Jayapura. It is the see city (seat) of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Wewak. ...

and Tuluvu in New Guinea. On 29 December, Adachi ordered the 102nd Infantry Regiment and other units under the command of Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Toru Okabe

was a major general in the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II.Toru Okabe

www.generals.dk

, the commander of the infantry group of the 51st Division, to move from Rabaul to www.generals.dk

...

Lae

Lae () is the capital of Morobe Province and is the second-largest city in Papua New Guinea. It is located near the delta of the Markham River and at the start of the Highlands Highway, which is the main land transport corridor between the Highl ...

and advance inland to capture Wau. After deciding to evacuate Guadalcanal on 4 January, the Japanese switched priorities from the Solomon Island

Solomon Islands is an island country consisting of six major islands and over 900 smaller islands in Oceania, to the east of Papua New Guinea and north-west of Vanuatu. It has a land area of , and a population of approx. 700,000. Its capita ...

s to New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu

Hiri Motu, also known as Police Motu, Pidgin Motu, or just Hiri, is a language of Papua New Guinea, which is spoken in surrounding areas of Port Moresby (Capital of Papua New Guinea).

It is a simplified version of ...

, and opted to send the 20th and 41st Divisions to Wewak.

On 5 January 1943, the convoy, which consisted of five destroyers and five troop transports carrying Okabe's force, set out for Lae from Rabaul. Forewarned by

On 5 January 1943, the convoy, which consisted of five destroyers and five troop transports carrying Okabe's force, set out for Lae from Rabaul. Forewarned by Ultra

adopted by British military intelligence in June 1941 for wartime signals intelligence obtained by breaking high-level encrypted enemy radio and teleprinter communications at the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park. '' ...

, United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

(USAAF) and Royal Australian Air Force

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries = RAAF Anniversary Commemoration ...

(RAAF) aircraft spotted, shadowed and attacked the convoy, which was shielded by low clouds and Japanese fighters. The Allies claimed to have shot down 69 Japanese aircraft for the loss of 10 of their own. An RAAF Consolidated PBY Catalina

The Consolidated PBY Catalina is a flying boat and amphibious aircraft that was produced in the 1930s and 1940s. In Canadian service it was known as the Canso. It was one of the most widely used seaplanes of World War II. Catalinas served w ...

sank the transport . Although destroyers rescued 739 of the 1,100 troops on board, the ship took with it all of Okabe's medical supplies. Another transport, , was so badly damaged at Lae by USAAF North American B-25 Mitchell

The North American B-25 Mitchell is an American medium bomber that was introduced in 1941 and named in honor of Major General William "Billy" Mitchell, a pioneer of U.S. military aviation. Used by many Allied air forces, the B-25 served in ...

s that it had to be beached. Nonetheless, the convoy succeeded in reaching Lae on 7 January and landing its troops, but Okabe was defeated in the Battle of Wau

The Battle of Wau, 29 January – 4 February 1943, was a battle in the New Guinea campaign of World War II. Forces of the Empire of Japan sailed from Rabaul and crossed the Solomon Sea and, despite Allied air attacks, successfully reached Lae, ...

.

Most of the 20th Division was landed at Wewak from naval high speed transport

High-speed transports were converted destroyers and destroyer escorts used in US Navy amphibious operations in World War II and afterward. They received the US Hull classification symbol APD; "AP" for transport and "D" for destroyer. In 1969, the ...

s on 19 January 1943. The bulk of the 41st Division followed on 12 February. Imamura and Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa

was a vice-admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) during World War II. Mikawa was the commander of a heavy cruiser force that won a spectacular IJN victory over the U.S. Navy and the Royal Australian Navy at the Battle of Savo Island in I ...

, the commander of the South East Area Fleet, developed a plan to move the command post of the headquarters of the Japanese XVIII Army and the main body of the 51st Division from Rabaul to Lae on 3 March, followed by moving the remainder of the 20th Division to Madang on 10 March. This plan was acknowledged to be risky because Allied air power in the area was strong. The XVIII Army staff held war games

A wargame is a strategy game in which two or more players command opposing armed forces in a realistic simulation of an armed conflict. Wargaming may be played for recreation, to train military officers in the art of strategic thinking, or to s ...

that predicted losses of four out of ten transports, and between 30 and 40 aircraft. They gave the operation only a 50–50 chance of success. On the other hand, if the troops were landed at Madang, they faced a march of more than over inhospitable swamp, mountain and jungle terrain without roads. To augment the three naval and two army fighter groups

A group is a number of persons or things that are located, gathered, or classed together.

Groups of people

* Cultural group, a group whose members share the same cultural identity

* Ethnic group, a group whose members share the same ethnic ide ...

in the area assigned to protect the convoy, the Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrender ...

temporarily detached 18 fighters from the aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

's fighter group from Truk to Kavieng

Kavieng is the capital of the Papua New Guinean province of New Ireland and the largest town on the island of the same name. The town is located at Balgai Bay, on the northern tip of the island. As of 2009, it had a population of 17,248.

Kavi ...

.

Allied intelligence

The Allies soon began detecting signs of preparations for a new convoy. A Japanesefloatplane

A floatplane is a type of seaplane with one or more slender floats mounted under the fuselage to provide buoyancy. By contrast, a flying boat uses its fuselage for buoyancy. Either type of seaplane may also have landing gear suitable for land, ...

of the type normally used for anti-submarine patrols in advance of convoys was sighted on 7 February 1943. The Allied Air Forces South West Pacific Area commander – Lieutenant General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

George Kenney

George Churchill Kenney (August 6, 1889 – August 9, 1977) was a United States Army general during World War II. He is best known as the commander of the Allied Air Forces in the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA), a position he held between Augu ...

– ordered an increase in reconnaissance

In military operations, reconnaissance or scouting is the exploration of an area by military forces to obtain information about enemy forces, terrain, and other activities.

Examples of reconnaissance include patrolling by troops (skirmisher ...

patrols over Rabaul. On 14 February, aerial photographs were taken that showed 79 vessels in port, including 45 merchant ships and six transports. It was clear that another convoy was being prepared, but its destination was unknown. On 16 February, naval codebreakers

Cryptanalysis (from the Greek language, Greek ''kryptós'', "hidden", and ''analýein'', "to analyze") refers to the process of analyzing information systems in order to understand hidden aspects of the systems. Cryptanalysis is used to breach C ...

in Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

(FRUMEL Fleet Radio Unit, Melbourne (FRUMEL) was a United States–Australian–British signals intelligence unit, founded in Melbourne, Australia, during World War II. It was one of two major Allied signals intelligence units called Fleet Radio Units in t ...

) and Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

finished decrypting and translating a coded message revealing the Japanese intention to land convoys at Wewak, Madang and Lae. Subsequently, codebreakers decrypted a message from the Japanese 11th Air Fleet to the effect that destroyers and six transports would reach Lae about 5 March. Another report indicated that they would reach Lae by 12 March. On 22 February, reconnaissance aircraft reported 59 merchant vessels in the harbour at Rabaul.

Kenney read this Ultra intelligence in the office of the Supreme Allied Commander, South West Pacific Area – General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of highest military ranks, high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers t ...

Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American military leader who served as General of the Army for the United States, as well as a field marshal to the Philippine Army. He had served with distinction in World War I, was C ...

– on 25 February. The prospect of an additional 6,900 Japanese troops in the Lae area greatly disturbed MacArthur, as they might seriously affect his plans to capture and develop the area. Kenney wrote out orders, which were sent by courier, for Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

Ennis Whitehead

Ennis Clement Whitehead (September 3, 1895 – October 12, 1964) was an early United States Army aviator and a United States Army Air Forces general during World War II. Whitehead joined the U. S. Army after the United States entered World War I ...

, the deputy commander of the Fifth Air Force

The Fifth Air Force (5 AF) is a numbered air force of the United States Air Force Pacific Air Forces (PACAF). It is headquartered at Yokota Air Base, Japan. It is the U.S. Air Force's oldest continuously serving Numbered Air Force. The organiza ...

, and the commander of its Advance Echelon (ADVON) in New Guinea. Under the Fifth Air Force's unusual command arrangements, Whitehead controlled the Allied Air Forces units of all types in New Guinea. This included the RAAF units there, which were grouped as No. 9 Operational Group RAAF, under the command of Air Commodore Joe Hewitt.

Kenney informed Whitehead of the proposed convoy date, and warned him about the usual Japanese pre-convoy air attack. He also urged that flying hours be cut back so as to allow for a large strike on the convoy, and instructed him to move forward as many aircraft as possible so that they could be close to the nearby captured airfields around Dobodura, where they would not be subject to the vagaries of weather over the Owen Stanley Range. Kenney flew up to Port Moresby

(; Tok Pisin: ''Pot Mosbi''), also referred to as Pom City or simply Moresby, is the capital and largest city of Papua New Guinea. It is one of the largest cities in the southwestern Pacific (along with Jayapura) outside of Australia and New Z ...

on 26 February, where he met with Whitehead. The two generals inspected fighter and bomber units in the area, and agreed to attack the Japanese convoy in the Vitiaz Strait

Vitiaz Strait is a strait between New Britain and the Huon Peninsula, northern New Guinea.

The Vitiaz Strait was so named by Nicholai Nicholaievich Mikluho-Maklai to commemorate the Russian corvette '' Vitiaz'' in which he sailed from Octobe ...

. Kenney returned to Brisbane

Brisbane ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the states and territories of Australia, Australian state of Queensland, and the list of cities in Australia by population, third-most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a populati ...

on 28 February.

Allied tactics

In the South West Pacific, a conventional strategic bombing campaign was out of the question, as industrial targets in Japan were well beyond the range of even the largest strategic bombers operating from bases in Australia and New Guinea. Therefore, the primary mission of the Allied bomber force wasinterdiction Interdiction is a military term for the act of delaying, disrupting, or destroying enemy forces or supplies en route to the battle area. A distinction is often made between strategic and tactical interdiction. The former refers to operations whose ...

of Japanese supply lines, especially the sea lanes. The results of the effort against the Japanese convoy in January were very disappointing; some 416 sorties had been flown with only two ships sunk and three damaged; clearly, a change of tactics was in order. Group Captain

Group captain is a senior commissioned rank in the Royal Air Force, where it originated, as well as the air forces of many countries that have historical British influence. It is sometimes used as the English translation of an equivalent rank i ...

Bill Garing, an RAAF officer on Kenney's staff with considerable experience in air-sea operations, including a tour of duty in Europe, recommended that Japanese convoys be subjected to simultaneous attack from different altitudes and directions.

The Allied Air Forces adopted some innovative tactics. In February 1942, the RAAF began experimenting with skip bombing

Skip bombing was a low-level bombing technique independently developed by several of the combatant nations in World War II, notably Italy, Australia, Britain, Soviet Union and the United States. It allows an aircraft to attack shipping by skippi ...

, an anti-shipping technique used by the British and Germans. Flying only a few dozen feet above the sea toward their targets, bombers would release their bombs which would then, ideally, ricochet

A ricochet ( ; ) is a rebound, bounce, or skip off a surface, particularly in the case of a projectile. Most ricochets are caused by accident and while the force of the deflection decelerates the projectile, it can still be energetic and almost ...

across the surface of the water and explode at the side of the target ship, under it, or just over it. A similar technique was mast-height bombing, in which bombers would approach the target at low altitude, , at about , and then drop down to mast height, at about from the target. They would release their bombs at around , aiming directly at the side of the ship. The Battle of the Bismarck Sea would demonstrate that this was the more successful of the two tactics. The two techniques were not mutually exclusive: a bomber could drop two bombs, skipping the first and launching the second at mast height. In addition, as regular bomb fuses were designed to detonate immediately on impact, which would catch the attacking aircraft in its own bomb blast at low altitude attacks, crews developed a delayed-action fuse. Practice missions were carried out against the wreck of the , a liner that had run aground in 1923.

In order for bombers to conduct skip or mast-height bombing, the target ship's antiaircraft artillery would first have to be neutralized by strafing runs. For the latter task, Major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

Paul I. "Pappy" Gunn and his men at the 81st Depot Repair Squadron in Townsville, Queensland

Townsville is a city on the north-eastern coast of Queensland, Australia. With a population of 180,820 as of June 2018, it is the largest settlement in North Queensland; it is unofficially considered its capital. Estimated resident population, 3 ...

, modified some USAAF Douglas A-20 Havoc

The Douglas A-20 Havoc (company designation DB-7) is an American medium bomber, attack aircraft, night intruder, night fighter, and reconnaissance aircraft of World War II.

Designed to meet an Army Air Corps requirement for a bomber, it was o ...

light bombers by installing four machine gun

A machine gun is a fully automatic, rifled autoloading firearm designed for sustained direct fire with rifle cartridges. Other automatic firearms such as automatic shotguns and automatic rifles (including assault rifles and battle rifles) a ...

s in their noses in September 1942. Two fuel tanks were added, giving the aircraft more range. An attempt was then made in December 1942 to create a longer range attack aircraft by doing the same thing to a B-25 medium bomber

A medium bomber is a military bomber Fixed-wing aircraft, aircraft designed to operate with medium-sized Aerial bomb, bombloads over medium Range (aeronautics), range distances; the name serves to distinguish this type from larger heavy bombe ...

to convert it to a "commerce destroyer", but this proved to be somewhat more difficult. The resulting aircraft was nose-heavy despite added lead ballast in the tail, and the vibrations caused by firing the machine guns were enough to make rivets pop out of the skin of the aircraft. The tail guns and belly turrets were removed, the latter being of little use if the aircraft was flying low. The new tactic of having the B-25 strafe ships would be tried in this battle.

The Fifth Air Force had two heavy bomber

Heavy bombers are bomber aircraft capable of delivering the largest payload of air-to-ground weaponry (usually bombs) and longest range (takeoff to landing) of their era. Archetypal heavy bombers have therefore usually been among the larges ...

groups. The 43rd Bombardment Group

The 43rd Air Mobility Operations Group is an active duty air mobility unit at Pope Field (formerly Pope AFB), Fort Bragg, North Carolina and is part of the Air Mobility Command (AMC) under the USAF Expeditionary Center. The unit is composed of f ...

was equipped with about 55 Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress

The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress is a four-engined heavy bomber developed in the 1930s for the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC). Relatively fast and high-flying for a bomber of its era, the B-17 was used primarily in the European Theater ...

es. Most of these had seen hard war service over the previous six months and the availability rate was low. The recently arrived 90th Bombardment Group was equipped with Consolidated B-24 Liberator

The Consolidated B-24 Liberator is an American heavy bomber, designed by Consolidated Aircraft of San Diego, California. It was known within the company as the Model 32, and some initial production aircraft were laid down as export models des ...

s, but they too had maintenance problems. There were two medium groups: the 38th Bombardment Group, equipped with B-25 Mitchells, and the 22nd Bombardment Group

The 22nd Operations Group is the operational flying component of the United States Air Force 22nd Air Refueling Wing. It is stationed at McConnell Air Force Base, Kansas, and is part of Air Mobility Command (AMC)'s Eighteenth Air Force.

The ...

, equipped with Martin B-26 Marauder

The Martin B-26 Marauder is an American twin-engined medium bomber that saw extensive service during World War II. The B-26 was built at two locations: Baltimore, Maryland, and Omaha, Nebraska, by the Glenn L. Martin Company.

First used in t ...

s, but two of the former's four squadrons had been diverted to the South Pacific Area

The South Pacific Area (SOPAC) was a multinational U.S.-led military command active during World War II. It was a part of the U.S. Pacific Ocean Areas under Admiral Chester Nimitz.

The delineation and establishment of the Pacific Ocean Areas was ...

, and the latter had taken so many losses that it had been withdrawn to Australia to be rebuilt.

There was also a light group, the 3rd Attack Group, equipped with a mixture of Douglas A-20 Havocs and B-25 Mitchells. This group was not just short of aircraft; it was critically short of aircrew as well. To make up the numbers the USAAF turned to the RAAF for help. Australian aircrew were assigned to most of the group's aircraft, serving in every role except aircraft commander. In addition to the RAAF aircrew with the USAAF squadrons, there were RAAF units in the Port Moresby area. No. 30 Squadron RAAF

No. 30 (City of Sale) Squadron is a squadron of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). Raised in 1942 as a long-range fighter unit, the squadron saw action in the Second World War, serving in the South West Pacific Area against the Japanese and ...

, which had arrived in Port Moresby in September 1942, was equipped with the Bristol Beaufighter. Both the aircraft and the squadron proved adept at low level attacks. Also in the Port Moresby area were the 35th and 49th Fighter Group

The 49th Fighter Group was a fighter aircraft unit of the Fifth Air Force that was located in the Asiatic-Pacific Theater during World War II.

Activation and training

The group was constituted as 49th Pursuit Group (Interceptor) on 20 November 194 ...

s, both equipped with Bell P-39, Curtiss P-40 Warhawk

The Curtiss P-40 Warhawk is an American single-engined, single-seat, all-metal fighter and ground-attack aircraft that first flew in 1938. The P-40 design was a modification of the previous Curtiss P-36 Hawk which reduced development time an ...

and Lockheed P-38 Lightning

The Lockheed P-38 Lightning is an American single-seat, twin piston-engined fighter aircraft that was used during World War II. Developed for the United States Army Air Corps by the Lockheed Corporation, the P-38 incorporated a distinctive twi ...

fighters, but only the last were suitable for long range escort missions.

Battle

Order of battle

seeBattle of the Bismarck Sea order of battle

The Battle of the Bismarck Sea (2–4 March 1943) took place in the South West Pacific Area (SWPA) during World War II.

At midnight 28 February 1942, eight transports carrying about 6,900 troops of the Imperial Japanese Army, escorted by eight des ...

First attacks

The Japanese convoy – comprising eightdestroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

s and eight troop transport

A troopship (also troop ship or troop transport or trooper) is a ship used to carry soldiers, either in peacetime or wartime. Troopships were often drafted from commercial shipping fleets, and were unable land troops directly on shore, typicall ...

s with an escort of approximately 100 fighters

Fighter(s) or The Fighter(s) may refer to:

Combat and warfare

* Combatant, an individual legally entitled to engage in hostilities during an international armed conflict

* Fighter aircraft, a warplane designed to destroy or damage enemy warplan ...

– assembled and departed from Simpson Harbour

Simpson Harbour is a sheltered harbour of Blanche Bay, on the Gazelle Peninsula in the extreme north of New Britain. The harbour is named after Captain Cortland Simpson, who surveyed the bay while in command of in 1872.

The former capital city ...

in Rabaul on 28 February. During the January operation, a course was followed that hugged the south coast of New Britain. This had made it easy to provide air cover, but being close to the airfields also made it possible for the Allied Air Forces to attack both the convoy and the airfields at the same time. This time, a route was chosen along the north coast, in the hope that the Allies would be deceived into thinking that the convoy's objective was Madang. Allied air attacks on the convoy at this point would have to fly over New Britain, allowing interdiction from Japanese air bases there, but the final leg of the voyage would be particularly dangerous, because the convoy would have to negotiate the restricted waters of the Vitiaz Strait. The Japanese named the convoy "Operation 81."

The destroyers carried 958 troops while the transports took 5,954. All the ships were combat loaded to expedite unloading at Lae. The commander of the Japanese XVIII Army – Lieutenant General Hatazō Adachi – travelled on the destroyer , while that of the 51st Division – Lieutenant General

The destroyers carried 958 troops while the transports took 5,954. All the ships were combat loaded to expedite unloading at Lae. The commander of the Japanese XVIII Army – Lieutenant General Hatazō Adachi – travelled on the destroyer , while that of the 51st Division – Lieutenant General Hidemitsu Nakano

was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army, commanding Japanese ground forces in the Southwest Pacific during the closing months of the war.

Biography

Nakano was born in Saga Prefecture, where his father was a former samurai retainer to Saga ...

– was on board the destroyer . The escort commander – Rear Admiral Masatomi Kimura

, was an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy during World War II.

Biography

Although born into the Kondō family of Shizuoka city Shizuoka Prefecture, Kimura was adopted by a family in Tottori city, Tottori prefecture soon after birth, and c ...

of the 3rd Destroyer Flotilla – flew his flag from the destroyer . The other five destroyers were , , , and . They escorted seven Army transports: (2,716 gross register tons), (950 tons), (5,493 tons), (6,494 tons), (3,793 tons), (2,883 tons) and (6,870 tons). Rounding out the force was the lone Navy transport (8,125 tons). All the ships carried troops, equipment and ammunition, except for the ''Kembu Maru'', which carried 1,000 drums of avgas

Avgas (aviation gasoline, also known as aviation spirit in the UK) is an aviation fuel used in aircraft with spark-ignited internal combustion engines. ''Avgas'' is distinguished from conventional gasoline (petrol) used in motor vehicles, w ...

and 650 drums of other fuel.

The convoy, moving at , was not detected for some time, because of two tropical storm

A tropical cyclone is a rapidly rotating storm system characterized by a low-pressure center, a closed low-level atmospheric circulation, strong winds, and a spiral arrangement of thunderstorms that produce heavy rain and squalls. Depend ...

s that struck the Solomon

Solomon (; , ),, ; ar, سُلَيْمَان, ', , ; el, Σολομών, ; la, Salomon also called Jedidiah (Hebrew language, Hebrew: , Modern Hebrew, Modern: , Tiberian Hebrew, Tiberian: ''Yăḏīḏăyāh'', "beloved of Yahweh, Yah"), ...

and Bismarck Sea

The Bismarck Sea (, ) lies in the southwestern Pacific Ocean within the nation of Papua New Guinea. It is located northeast of the island of New Guinea and south of the Bismarck Archipelago. It has coastlines in districts of the Islands Regi ...

s between 27 February and 1 March, but at about 15:00 on 1 March, the crew of a patrolling B-24 Liberator heavy bomber spotted the convoy. Eight B-17 Flying Fortresses were sent to the location but failed to locate the ships.

At dawn on 2 March, a force of six RAAF A-20 Bostons attacked Lae to reduce its ability to provide support. At about 10:00, another Liberator found the convoy. Eight B-17s took off to attack the ships, followed an hour later by another 20. The B-17s were planned to rendezvous with P-38 fighters from the 9th Fighter Squadron, however the B-17s arrived early and faced the Japanese fighters on their own for the initial air battle until the P-38s arrived. They found the convoy and attacked with bombs from . They claimed to have sunk up to three merchant ships. ''Kyokusei Maru'' had sunk carrying 1,200 army troops, and two other transports, ''Teiyo Maru'' and ''Nojima'', were damaged. Eight Japanese fighters were destroyed and 13 damaged in the day's action, while nine B-17s were damaged.

The destroyers ''Yukikaze'' and ''Asagumo'' plucked 950 survivors of ''Kyokusei Maru'' from the water. These two destroyers, being faster than the convoy since its speed was dictated by the slower transports, broke away from the group to disembark the survivors at Lae. The destroyers resumed their escort duties the next day. The convoy – without the troop transport and two destroyers – was attacked again on the evening of 2 March by 11 B-17s, with minor damage to one transport. During the night, PBY Catalina flying boat

A flying boat is a type of fixed-winged seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in that a flying boat's fuselage is purpose-designed for floatation and contains a hull, while floatplanes rely on fusela ...

s from No. 11 Squadron RAAF took over the task of shadowing the convoy.

Further attacks

By 3 March, the convoy was within range of the air base at Milne Bay, and eightBristol Beaufort

The Bristol Beaufort (manufacturer designation Type 152) is a British twin-engined torpedo bomber designed by the Bristol Aeroplane Company, and developed from experience gained designing and building the earlier Blenheim light bomber. At l ...

torpedo bomber

A torpedo bomber is a military aircraft designed primarily to attack ships with aerial torpedoes. Torpedo bombers came into existence just before the First World War almost as soon as aircraft were built that were capable of carrying the weight ...

s from No. 100 Squadron RAAF took off from there. Because of bad weather only two found the convoy, and neither scored any hits, but the weather cleared after they rounded the Huon Peninsula. A force of 90 Allied aircraft took off from Port Moresby, and headed for Cape Ward Hunt, while 22 A-20 Bostons of No. 22 Squadron RAAF

No. 22 (City of Sydney) Squadron is a Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) mixed Permanent and Reserve squadron that provides support for the RAAF in the Sydney region. Formed in 1936, the squadron served in Papua New Guinea during the Second Wor ...

attacked the Japanese fighter base at Lae, reducing the convoy's air cover. Attacks on the base continued throughout the day.

At 10:00, 13 B-17s reached the convoy and bombed from medium altitude of 7,000 feet, causing the ships to maneuver, which dispersed the convoy formation and reduced their concentrated anti-aircraft firepower. The B-17s attracted Mitsubishi A6M Zero

The Mitsubishi A6M "Zero" is a long-range carrier-based fighter aircraft formerly manufactured by Mitsubishi Aircraft Company, a part of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, and was operated by the Imperial Japanese Navy from 1940 to 1945. The A6M w ...

fighters, which were in turn attacked by the P-38 Lightning escorts. A B-17 broke up in the air, and its crew took to their parachutes. Japanese fighter pilots machine-gunned some of the B-17 crew members as they descended and attacked others in the water after they landed. Five of the Japanese fighters strafing the B-17 aircrew were promptly engaged and shot down by three P-38s which were also lost. The Allied fighter pilots claimed 15 Zeros destroyed, while the B-17 crews claimed five more. Actual Japanese fighter losses for the day were seven destroyed and three damaged. B-25s arrived shortly afterward and released their 500-pound bombs between 3,000 and 6,000 feet, reportedly causing two Japanese vessels to collide. The result of the B-17 and B-25 sorties scored few hits but left the convoy ships separated making them vulnerable to strafers and masthead bombers, and with the Japanese anti-aircraft fire being focused on the medium-altitude bombers this left an opening for minimum altitude attacks.

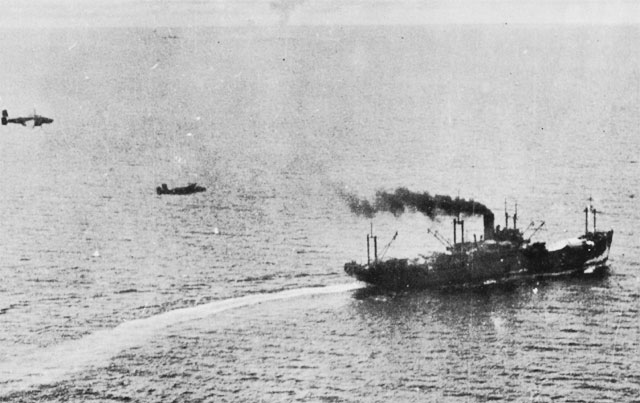

The 13 Beaufighters from No. 30 Squadron RAAF approached the convoy at low level to give the impression they were Beauforts making a torpedo attack. The ships turned to face them, the standard procedure to present a smaller target to torpedo bombers, allowing the Beaufighters to maximise the damage they inflicted on the ships' anti-aircraft guns, bridges and crews in

The 13 Beaufighters from No. 30 Squadron RAAF approached the convoy at low level to give the impression they were Beauforts making a torpedo attack. The ships turned to face them, the standard procedure to present a smaller target to torpedo bombers, allowing the Beaufighters to maximise the damage they inflicted on the ships' anti-aircraft guns, bridges and crews in strafing

Strafing is the military practice of attacking ground targets from low-flying aircraft using aircraft-mounted automatic weapons.

Less commonly, the term is used by extension to describe high-speed firing runs by any land or naval craft such ...

runs with their four nose cannons

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder dur ...

and six wing-mounted machine guns. On board one of the Beaufighters was cameraman Damien Parer

Damien Peter Parer (1 August 1912 – 17 September 1944) was an Australian war photographer. He became famous for his war photography of the Second World War, and was killed by Japanese machine-gun fire at Peleliu, Palau. He was cinematographer ...

, who shot dramatic footage of the battle; it was later published in ''The Bismarck Convoy Smashed

''Bismark Convoy Smashed!'', also known as ''Battle of the Bismark Sea,'' is a World War II, Second World War 1943 Australian documentary newsreel film about the Battle of the Bismarck Sea on 2–3 March, an engagement which resulted in the claime ...

''. Immediately afterward, seven B-25s of the 38th Bombardment Group's 71st Bombardment Squadron bombed from about , while six from the 405th Bombardment Squadron attacked at mast height.

According to the official RAAF release on the Beaufighter attack, "enemy crews were slain beside their guns, deck cargo burst into flame, superstructures toppled and burned". Garrett Middlebrook, a co-pilot in one of the B-25s, described the ferocity of the strafing attacks:

''Shirayuki'' was the first ship to be hit, by a combination of strafing and bombing attacks. Almost all the men on the bridge became casualties, including Kimura, who was wounded. One bomb hit started a magazine

A magazine is a periodical publication, generally published on a regular schedule (often weekly or monthly), containing a variety of content. They are generally financed by advertising, purchase price, prepaid subscriptions, or by a combinatio ...

explosion that caused the stern to break off, and the ship to sink. Her crew was transferred to ''Shikinami'', and ''Shirayuki'' was scuttled

Scuttling is the deliberate sinking of a ship. Scuttling may be performed to dispose of an abandoned, old, or captured vessel; to prevent the vessel from becoming a navigation hazard; as an act of self-destruction to prevent the ship from being ...

. The destroyer ''Tokitsukaze'' was also hit and fatally damaged. Its crew was taken off by ''Yukikaze''. The destroyer ''Arashio'' was hit, and collided with the transport ''Nojima'', disabling her. Both the destroyer and the transport were abandoned, and ''Nojima'' was later sunk by an air attack.

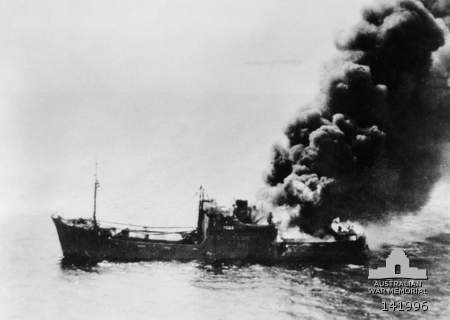

Fourteen B-25s returned that afternoon, reportedly claiming 17 hits or near misses. By this time, a third of the transports were sunk or sinking. As the Beaufighters and B-25s had expended their munitions, some USAAF A-20 Havocs of the 3rd Attack Group joined in. Another five hits were claimed by B-17s of the 43rd Bombardment Group from higher altitudes. During the afternoon, further attacks from USAAF B-25s and Bostons of No. 22 Squadron RAAF followed.

All seven of the transports were hit and most were burning or sinking about south east of

Fourteen B-25s returned that afternoon, reportedly claiming 17 hits or near misses. By this time, a third of the transports were sunk or sinking. As the Beaufighters and B-25s had expended their munitions, some USAAF A-20 Havocs of the 3rd Attack Group joined in. Another five hits were claimed by B-17s of the 43rd Bombardment Group from higher altitudes. During the afternoon, further attacks from USAAF B-25s and Bostons of No. 22 Squadron RAAF followed.

All seven of the transports were hit and most were burning or sinking about south east of Finschhafen

Finschhafen is a town east of Lae on the Huon Peninsula in Morobe Province of Papua New Guinea. The town is commonly misspelt as Finschafen or Finschaven. During World War II, the town was also referred to as Fitch Haven in the logs of some U.S ...

, along with the destroyers ''Shirayuki'', ''Tokitsukaze'' and ''Arashio''. Four of the destroyers – ''Shikinami'', ''Yukikaze'', ''Uranami'' and ''Asagumo'' – picked up as many survivors as possible and then retired to Rabaul, accompanied by the destroyer , which had come from Rabaul to assist. That night, a force of ten U.S. Navy PT boat

A PT boat (short for patrol torpedo boat) was a motor torpedo boat used by the United States Navy in World War II. It was small, fast, and inexpensive to build, valued for its maneuverability and speed but hampered at the beginning of the wa ...

s – under the command of Lieutenant Commander

Lieutenant commander (also hyphenated lieutenant-commander and abbreviated Lt Cdr, LtCdr. or LCDR) is a commissioned officer rank in many navies. The rank is superior to a lieutenant and subordinate to a commander. The corresponding rank i ...

Barry Atkins – set out to attack the convoy. Two boats struck submerged debris and were forced to return. The other eight arrived off Lae in the early hours of 4 March. Atkins spotted a fire that turned out to be the transport ''Oigawa Maru''. '' PT-143'' and ''PT-150'' fired torpedoes at it, sinking the crippled vessel. In the morning, a fourth destroyer – ''Asashio'' – was sunk when a B-17 hit her with a bomb while she was picking up survivors from ''Arashio''. Only one destroyer, ''Yukikaze'', was undamaged among the four surviving destroyers.

Some 2,700 survivors were taken to Rabaul by the destroyers. On 4 March, another 1,000 or so survivors were adrift on rafts. On the evenings of 3–5 March, PT boats and planes attacked Japanese rescue vessels, as well as the survivors from the sunken vessels on life rafts and swimming or floating in the sea. This was later justified on the grounds that rescued servicemen would have been rapidly landed at their military destination and promptly returned to active service, as well as being retaliation for the Japanese fighter planes attacking survivors of the downed B-17 bomber. While many of the Allied aircrew accepted these attacks as being necessary, others were sickened. On 6 March, the Japanese submarines and picked up 170 survivors. Two days later, ''I-26'' found another 54 and put them ashore at Lae. Hundreds made their way to various islands. One band of 18 survivors landed on

Some 2,700 survivors were taken to Rabaul by the destroyers. On 4 March, another 1,000 or so survivors were adrift on rafts. On the evenings of 3–5 March, PT boats and planes attacked Japanese rescue vessels, as well as the survivors from the sunken vessels on life rafts and swimming or floating in the sea. This was later justified on the grounds that rescued servicemen would have been rapidly landed at their military destination and promptly returned to active service, as well as being retaliation for the Japanese fighter planes attacking survivors of the downed B-17 bomber. While many of the Allied aircrew accepted these attacks as being necessary, others were sickened. On 6 March, the Japanese submarines and picked up 170 survivors. Two days later, ''I-26'' found another 54 and put them ashore at Lae. Hundreds made their way to various islands. One band of 18 survivors landed on Kiriwina

Kiriwina is the largest of the Trobriand Islands, with an area of 290.5 km². It is part of the Milne Bay Province of Papua New Guinea. Most of the 12,000 people who live in the Trobriands live on Kiriwina. The Kilivila language, also known ...

, where they were captured by ''PT-114''. Another made its way to Guadalcanal, only to be killed by an American patrol.

On 4 March the Japanese mounted a retaliatory raid on the Buna airfield, the site of a base that the Allies had captured back in January, though the fighters did little damage. Kenney wrote in his memoir that the Japanese reprisal occurred "after the horse had been stolen from the barn. It was a good thing that the Nip

''Nip'' is an ethnic slur against people of Japanese descent and origin. The word ''Nip'' is an abbreviation from ''Nippon'' (日本), the Japanese name for Japan.

History

The earliest recorded occurrence of the slur seems to be in the ''Time' ...

air commander was stupid. Those hundred airplanes would have made our job awfully hard if they had taken part in the big fight over the convoy on March 3rd."

On Goodenough Island

Goodenough Island in the Solomon Sea, also known as Nidula Island, is the westernmost of the three large islands of the D'Entrecasteaux Islands in Milne Bay Province of Papua New Guinea. It lies to the east of mainland New Guinea and southwest ...

, between 8 and 14 March 1943, Australian patrols from the 47th Infantry Battalion found and killed 72 Japanese, captured 42 and found another nine dead on a raft. One patrol killed eight Japanese who had landed in two flat-bottomed boats, in which were found some documents in sealed tins. On translation by the Allied Translator and Interpreter Section The Allied Translator and Interpreter Section (ATIS), also known as the Allied Translator and Interpreter Service or Allied Translator and Intelligence Service, was a joint Australian/ American World War II intelligence agency which served as a cent ...

, one document turned out to be a copy of the Japanese Army List, with the names and postings of every officer in the Japanese Army. It therefore provided a complete order of battle of the Japanese Army, including many units that had never before been reported. A mention of any Japanese officer could now be correlated with his unit. Copies were made available to intelligence units in every theatre of war against Japan.

Aftermath

The battle was a disaster for the Japanese. Out of 6,900 troops who were badly needed in New Guinea, only about 1,200 made it to Lae. Another 2,700 were saved by destroyers and submarines and returned to Rabaul. About 2,890 Japanese soldiers and sailors were killed. The Allies lost 13 aircrew, 10 of whom were lost in combat while three others died in an accident. There were also eight wounded. Aircraft losses were one B-17 and three P-38s in combat, and one B-25 and one Beaufighter in accidents. MacArthur issued a communiqué on 7 March stating that 22 ships, including twelve transports, three cruisers and seven destroyers, had been sunk along with 12,792 troops. Army Air Force Headquarters in Washington, D.C. looked into the matter in mid-1943 and concluded that there were only 16 ships involved, but GHQ SWPA considered the original account accurate. The victory was a propaganda boon for the Allies, with one United States newsreel claiming the Japanese had lost 22 ships, 15,000 troops, and 102 aircraft. The New York Times, on its front page on March 4, 1943, cited the loss by the Japanese of 22 ships, 15,000 troops and 55 aircraft. The Allied Air Forces had used 233,847 rounds of ammunition, and dropped two-hundred and sixty-one 500-pound and two-hundred and fifty-three 1,000-pound bombs. They claimed 19 hits and 42 near misses with the former and 59 hits and 39 near misses from the latter. Of the 137 bombs dropped in low level attacks, 48 (35 percent) were claimed to have hit but only 29 (7.5 percent) of the 387 bombs dropped from medium altitude. This compared favourably with efforts in August and September 1942 when only 3 percent of bombs dropped were claimed to have scored hits. It was noted that the high and medium altitude attacks scored few hits but dispersed the convoy, while the strafing runs from the Beaufighters had knocked out many of the ships' anti-aircraft defences. Aircraft attacking from several directions at once had confused and overwhelmed the Japanese defences, resulting in lower casualties and more accurate bombing. The results therefore vindicated not just the tactics of mast height attack but of mounting coordinated attacks from several directions. The Japanese estimated that at least 29 bombs had hit a ship during the battle. This was a big improvement over theBattle of Wau

The Battle of Wau, 29 January – 4 February 1943, was a battle in the New Guinea campaign of World War II. Forces of the Empire of Japan sailed from Rabaul and crossed the Solomon Sea and, despite Allied air attacks, successfully reached Lae, ...

back in January, when Allied aircraft attacked a Japanese convoy consisting of five destroyers and five troop transports travelling from Rabaul to Lae, but managed to sink just one transport and beach another.

Imamura's chief of staff flew to Imperial General Headquarters to report on the disaster. It was decided that there would be no more attempts to land troops at Lae. The losses incurred in the Bismarck Sea caused grave concern for the security of Lae and Rabaul and resulted in a change of strategy. On 25 March a joint Army-Navy Central Agreement on South West Area Operations gave operations in New Guinea priority over those in the

Imamura's chief of staff flew to Imperial General Headquarters to report on the disaster. It was decided that there would be no more attempts to land troops at Lae. The losses incurred in the Bismarck Sea caused grave concern for the security of Lae and Rabaul and resulted in a change of strategy. On 25 March a joint Army-Navy Central Agreement on South West Area Operations gave operations in New Guinea priority over those in the Solomon Islands campaign

The Solomon Islands campaign was a major campaign of the Pacific War of World War II. The campaign began with Japanese landings and occupation of several areas in the British Solomon Islands and Bougainville, in the Territory of New Guinea, du ...

. The XVIII Army was allocated additional shipping, ordnance and anti-aircraft units, which were sent to Wewak or Hansa Bay. Of the defeat, Rabaul staff officer Masatake Okumiya said, "Our losses for this single battle were fantastic. Not during the entire savage fighting at Guadalcanal did we suffer a single comparable blow. We knew we could no longer run cargo ships or even fast destroyer transports to any front on the north coast of New Guinea, east of Wewak".

The planned movement of the 20th Division to Madang was revised in the light of events in the Bismarck Sea. The operation was postponed for two days, and the destination was altered from Madang to Hansa Bay

Hansa Bay is a bay located on the north coast of Papua New Guinea, in Madang Province, between Madang and Wewak, northeast of Bogia.

World War II history

During the New Guinea campaign, Hansa Bay was a major Japanese naval base and transit ...

further west. To reduce the Allied air threat, the Allied airfield at Wau was bombed on 9 March and that at Dobodura on 11 March. Three Allied aircraft were destroyed on the ground and one P-40 was lost in the air but Allied fighters claimed nine Japanese aircraft. The transports reached Hansa Bay unscathed on 12 March and the troops made their way down to Madang on foot or in barges. The 20th Division then became involved in an attempt to construct a road from Madang to Lae through the Ramu

The Ramu River is a major river in northern Papua New Guinea. The headwaters of the river are formed in the Kratke Range from where it then travels about northwest to the Bismarck Sea.

Along the Ramu's course, it receives numerous tributaries ...

and Markham Valley

The Markham Valley is a geographical area in Papua New Guinea. The name "Markham" commemorates Sir Clements Markham, Secretary of the British Royal Geographical Society - Captain John Moresby of the Royal Navy named the Markham River after Sir Cl ...

s. It toiled on the road for the next few months but its efforts were ultimately frustrated by the New Guinea weather and the rugged terrain of the Finisterre Range

The Finisterre Range is a mountain range in north-eastern Papua New Guinea. The highest point is ranked 41st in the world by prominence with an elevation of 4,150 m. Although the range's high point is not named on official maps, the name "Mount ...

.

Some submarines were made available for supply runs to Lae but they did not have the capacity to support the troops there by themselves. An operation was carried out on 29 March in which four destroyers delivered 800 troops to Finschhafen but the growing threat from Allied aircraft led to the development of routes along the coast of New Guinea from Madang to Finschhafen and along the north and south coasts of New Britain to Finschhafen, thence to Lae using Army landing craft

Landing craft are small and medium seagoing watercraft, such as boats and barges, used to convey a landing force (infantry and vehicles) from the sea to the shore during an amphibious assault. The term excludes landing ships, which are larger. Pr ...

. It was by this means that the remainder of the 51st Division finally made the trip to Lae in May. The necessity of delivering troops and supplies to the front in this manner caused immense difficulties for the Japanese in their attempts to halt further Allied advances. After the war, Japanese officers at Rabaul estimated that around 20,000 troops were lost in transit to New Guinea from Rabaul, a significant factor in Japan's ultimate defeat in the New Guinea campaign.

In April, Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

Isoroku Yamamoto

was a Marshal Admiral of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) and the commander-in-chief of the Combined Fleet during World War II until he was killed.

Yamamoto held several important posts in the IJN, and undertook many of its changes and reor ...

used the additional air resources allocated to Rabaul in Operation I-Go

was an aerial counter-offensive launched by Imperial Japanese forces against Allied forces during the Solomon Islands and New Guinea Campaigns in the Pacific Theater of World War II. Taking place from 1–16 April 1943, during the operation, ...

, an air offensive designed to redress the situation by destroying Allied ships and aircraft in New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. The operation was indecisive and Yamamoto became a casualty of Allied intelligence and air power in the Solomon Islands on 18 April 1943.

Game theory

In 1954, O. G. Haywood Jr., wrote an article in the ''Journal of the Operations Research Society of America

''Operations Research'' is a bimonthly peer-reviewed academic journal covering operations research that is published by the Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences. It was established in 1952 as the ''Journal of the Operation ...

'' in which game theory

Game theory is the study of mathematical models of strategic interactions among rational agents. Myerson, Roger B. (1991). ''Game Theory: Analysis of Conflict,'' Harvard University Press, p.&nbs1 Chapter-preview links, ppvii–xi It has appli ...

was used to model the decision-making in the battle. Since then, the name of the battle has been applied to this particular type of two-person zero-sum game

Zero-sum game is a mathematical representation in game theory and economic theory of a situation which involves two sides, where the result is an advantage for one side and an equivalent loss for the other. In other words, player one's gain is e ...

.

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * *External links

Bismarck Convoy Smashed!

Incorporates footage of the battle taken by Damien Parer. {{DEFAULTSORT:Bismarck Sea, Battle of 1943 in Papua New Guinea Battles and operations of World War II involving Papua New Guinea Territory of New Guinea Bismarck Sea Conflicts in 1943 Naval battles of World War II involving Australia Naval battles of World War II involving Japan Naval battles of World War II involving the United States South West Pacific theatre of World War II World War II aerial operations and battles of the Pacific theatre March 1943 events