Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an

Indian religion

Indian religions, sometimes also termed Dharmic religions or Indic religions, are the religions that originated in the Indian subcontinent. These religions, which include Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, and Sikhism,Adams, C. J."Classification of ...

or

philosophical tradition

A tradition is a belief or behavior (folk custom) passed down within a group or society with symbolic meaning or special significance with origins in the past. A component of cultural expressions and folklore, common examples include holidays o ...

based on

teachings attributed to

the Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha, was a wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism.

According to Buddhist tradition, he was born in Lu ...

. It originated in

northern India

North India is a loosely defined region consisting of the northern part of India. The dominant geographical features of North India are the Indo-Gangetic Plain and the Himalayas, which demarcate the region from the Tibetan Plateau and Central ...

as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and

gradually spread throughout much of Asia via the Silk Road. It is the

world's fourth-largest religion, with over 520 million followers (Buddhists) who comprise seven percent of the global population.

The Buddha taught the

Middle Way, a path of spiritual development that avoids both extreme

asceticism and hedonism. It aims at liberation from clinging and craving to things which are impermanent (), incapable of satisfying ('), and without a lasting essence (), ending the cycle of death and rebirth (). A summary of this path is expressed in the

Noble Eightfold Path

The Noble Eightfold Path (Pali: ; Sanskrit: ) is an early summary of the path of Buddhist practices leading to liberation from samsara, the painful cycle of rebirth, in the form of nirvana.

The Eightfold Path consists of eight practices: ...

, a

training of the mind with observance of

Buddhist ethics

Buddhist ethics are traditionally based on what Buddhists view as the enlightened perspective of the Buddha. The term for ethics or morality used in Buddhism is ''Śīla'' or ''sīla'' (Pāli). ''Śīla'' in Buddhism is one of three sections of ...

and

meditation

Meditation is a practice in which an individual uses a technique – such as mindfulness, or focusing the mind on a particular object, thought, or activity – to train attention and awareness, and achieve a mentally clear and emotionally calm ...

. Other widely observed practices include:

monasticism; "

taking refuge" in the Buddha, the , and the ; and the cultivation of perfections ().

Two major extant branches of Buddhism are generally recognized by scholars: ''

Theravāda

''Theravāda'' () ( si, ථේරවාදය, my, ထေရဝါဒ, th, เถรวาท, km, ថេរវាទ, lo, ເຖຣະວາດ, pi, , ) is the most commonly accepted name of Buddhism's oldest existing school. The school' ...

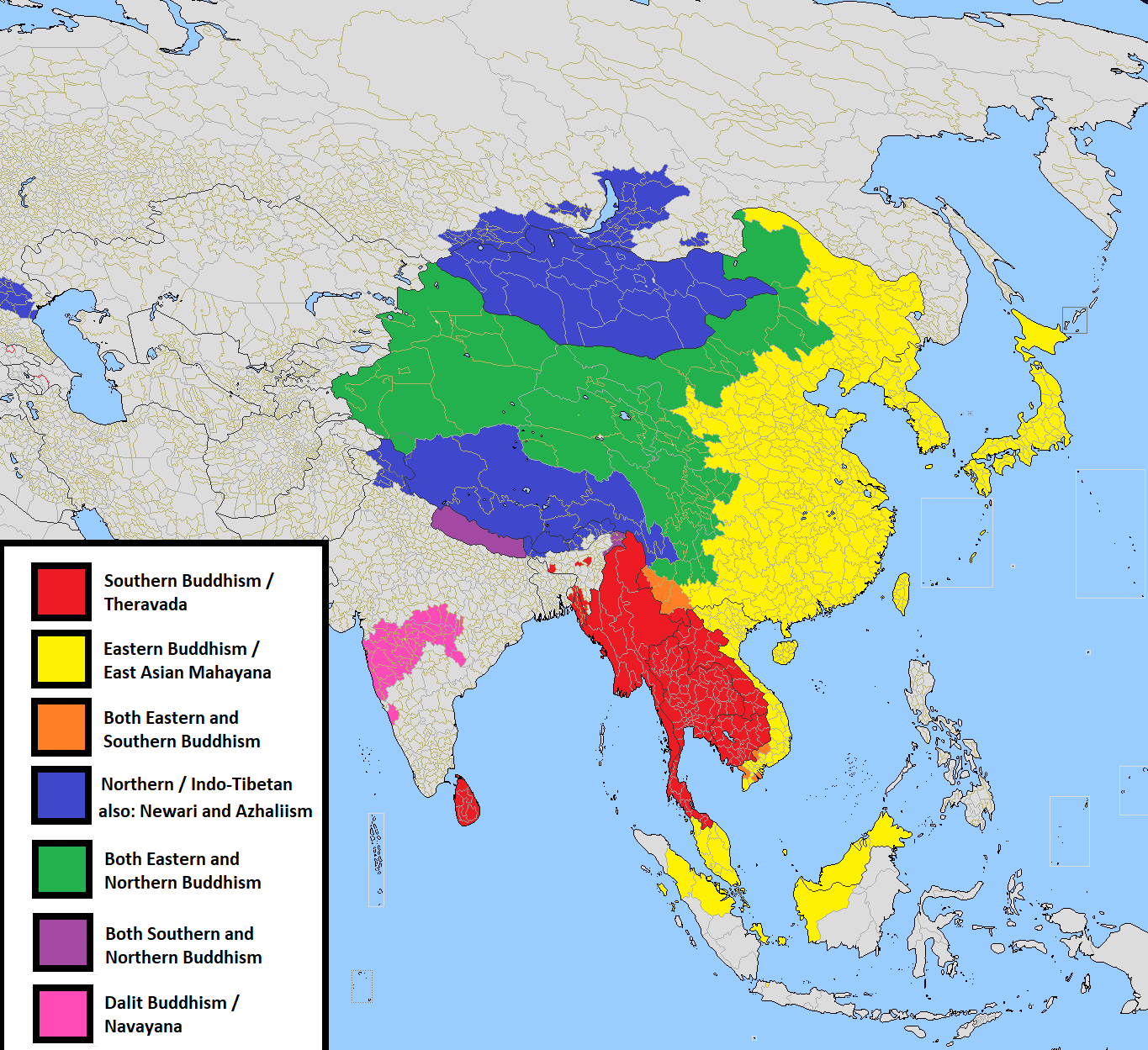

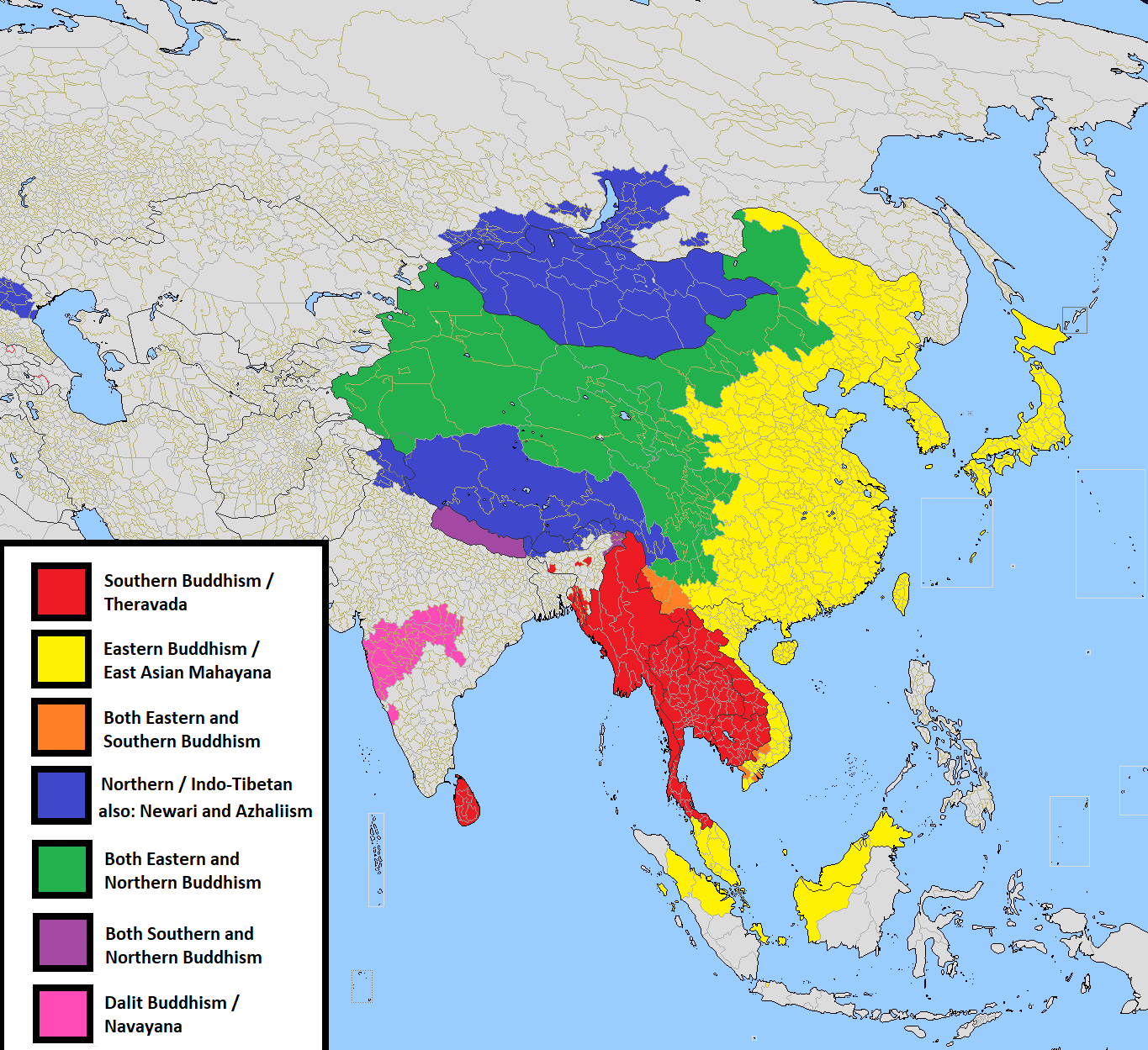

'' () and (). The ''Theravāda'' branch has a widespread following in Sri Lanka as well as in Southeast Asia (namely Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia). The ' branch—which includes the traditions of

Zen

Zen ( zh, t=禪, p=Chán; ja, text= 禅, translit=zen; ko, text=선, translit=Seon; vi, text=Thiền) is a school of Mahayana Buddhism that originated in China during the Tang dynasty, known as the Chan School (''Chánzong'' 禪宗), and ...

,

Pure Land,

Nichiren

Nichiren (16 February 1222 – 13 October 1282) was a Japanese Buddhist priest and philosopher of the Kamakura period.

Nichiren declared that the Lotus Sutra alone contains the highest truth of Buddhist teachings suited for the Third Age of ...

,

Tiantai

Tiantai or T'ien-t'ai () is an East Asian Buddhist school of Mahāyāna Buddhism that developed in 6th-century China. The school emphasizes the ''Lotus Sutra's'' doctrine of the "One Vehicle" (''Ekayāna'') as well as Mādhyamaka philosophy ...

,

Tendai

, also known as the Tendai Lotus School (天台法華宗 ''Tendai hokke shū,'' sometimes just "''hokke shū''") is a Mahāyāna Buddhist tradition (with significant esoteric elements) officially established in Japan in 806 by the Japanese m ...

, and

Shingon

Shingon monks at Mount Koya

is one of the major schools of Buddhism in Japan and one of the few surviving Vajrayana lineages in East Asia, originally spread from India to China through traveling monks such as Vajrabodhi and Amoghavajra.

Kn ...

—is predominantly practiced in Nepal, Bhutan, China, Malaysia, Vietnam, Taiwan, Korea, and Japan. Additionally, (), a body of teachings attributed to

Indian adepts, may be viewed as a separate branch or an aspect of the ' tradition.

Tibetan Buddhism

Tibetan Buddhism (also referred to as Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, Lamaism, Lamaistic Buddhism, Himalayan Buddhism, and Northern Buddhism) is the form of Buddhism practiced in Tibet and Bhutan, where it is the dominant religion. It is also in majo ...

, which preserves the teachings of eighth-century India, is practiced in the

Himalayan states

The term Himalayan states is used to group countries that straddle the Himalayas. It primarily denotes Bhutan, China, India, Nepal, and Pakistan; some definitions also include Afghanistan and Myanmar. Two countries—Bhutan and Nepal—are loc ...

as well as in Mongolia and

Russian Kalmykia. Historically, until the early 2nd millennium, Buddhism

was widely practiced in the Indian subcontinent;

it also had a foothold to some extent in other places such as Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, and the Philippines.

Buddhist schools

The schools of Buddhism are the various institutional and doctrinal divisions of Buddhism that have existed from ancient times up to the present. The classification and nature of various doctrinal, philosophical or cultural facets of the schools ...

vary in their interpretation of the paths to liberation () as well as the relative importance and canonicity assigned to various

Buddhist texts, and their specific teachings and practices. The Theravada Buddhist tradition emphasizes transcending the individual self through the attainment of (), while the Mahayana tradition emphasizes the

Bodhisattva-ideal.

Etymology

Buddhism is an Indian religion the Buddha ("the Awakened One"), a

Śramaṇa

''Śramaṇa'' (Sanskrit: श्रमण; Pali: ''samaṇa, Tamil: Samanam'') means "one who labours, toils, or exerts themselves (for some higher or religious purpose)" or "seeker, one who performs acts of austerity, ascetic".Monier Monier ...

who lived c. 5th century BCE.

Followers of Buddhism, called ''Buddhists'' in English, referred to themselves as ''Sakyan''-s or ''Sakyabhiksu'' in ancient India. Buddhist scholar Donald S. Lopez asserts they also used the term ''Bauddha'', although scholar Richard Cohen asserts that that term was used only by outsiders to describe Buddhists.

The Buddha

Details of the Buddha's life are mentioned in many

Early Buddhist Texts

Early Buddhist texts (EBTs), early Buddhist literature or early Buddhist discourses are parallel texts shared by the early Buddhist schools. The most widely studied EBT material are the first four Pali Nikayas, as well as the corresponding Chines ...

but are inconsistent. His social background and life details are difficult to prove, and the precise dates are uncertain.

Early texts have the Buddha's family name as "Gautama" (Pali: Gotama), while some texts give Siddhartha as his surname. He was born in

Lumbini

Lumbinī ( ne, लुम्बिनी, IPA=ˈlumbini , "the lovely") is a Buddhist pilgrimage site in the Rupandehi District of Lumbini Province in Nepal. It is the place where, according to Buddhist tradition, Queen Mahamayadevi gave birth ...

, present-day

Nepal

Nepal (; ne, :ne:नेपाल, नेपाल ), formerly the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal ( ne,

सङ्घीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल ), is a landlocked country in S ...

and grew up in

Kapilavastu, a town in the

Ganges Plain

The Indo-Gangetic Plain, also known as the North Indian River Plain, is a fertile plain encompassing northern regions of the Indian subcontinent, including most of northern and eastern India, around half of Pakistan, virtually all of Bangla ...

, near the modern Nepal–India border, and that he spent his life in what is now modern

Bihar

Bihar (; ) is a state in eastern India. It is the 2nd largest state by population in 2019, 12th largest by area of , and 14th largest by GDP in 2021. Bihar borders Uttar Pradesh to its west, Nepal to the north, the northern part of West ...

and

Uttar Pradesh

Uttar Pradesh (; , 'Northern Province') is a state in northern India. With over 200 million inhabitants, it is the most populated state in India as well as the most populous country subdivision in the world. It was established in 1950 ...

. Some hagiographic legends state that his father was a king named Suddhodana, his mother was Queen Maya.

Scholars such as

Richard Gombrich

Richard Francis Gombrich (; born 17 July 1937) is a British Indologist and scholar of Sanskrit, Pāli, and Buddhist studies. He was the Boden Professor of Sanskrit at the University of Oxford from 1976 to 2004. He is currently Founder-Presiden ...

consider this a dubious claim because a combination of evidence suggests he was born in the

Shakya

Shakya ( Pāḷi: ; sa, शाक्य, translit=Śākya) was an ancient eastern sub-Himalayan ethnicity and clan of north-eastern region of the Indian subcontinent, whose existence is attested during the Iron Age. The Shakyas were organised ...

community, which was governed by a

small oligarchy or republic-like council where there were no ranks but where seniority mattered instead. Some of the stories about the Buddha, his life, his teachings, and claims about the society he grew up in may have been invented and interpolated at a later time into the Buddhist texts.

According to early texts such as the Pali ''Ariyapariyesanā-sutta'' ("The discourse on the noble quest",

MN 26) and its Chinese parallel at

MĀ 204, Gautama was moved by the suffering (''

dukkha'') of life and death, and its

endless repetition due to

rebirth

Rebirth may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

Film

* ''Rebirth'' (2011 film), a 2011 Japanese drama film

* ''Rebirth'' (2016 film), a 2016 American thriller film

* ''Rebirth'', a documentary film produced by Project Rebirth

* ''The Re ...

. He thus set out on a quest to find liberation from suffering (also known as "

nirvana

( , , ; sa, निर्वाण} ''nirvāṇa'' ; Pali: ''nibbāna''; Prakrit: ''ṇivvāṇa''; literally, "blown out", as in an oil lampRichard Gombrich, ''Theravada Buddhism: A Social History from Ancient Benāres to Modern Colombo.' ...

"). Early texts and biographies state that Gautama first studied under two teachers of meditation, namely

Āḷāra Kālāma

Alara Kalama ( Pāḷi & Sanskrit ', was a hermit and a teacher of ancient meditation. He was a teacher of Śramaṇa thought and, according to the Pāli Canon scriptures, the first teacher of Gautama Buddha.

History

After Siddhartha Gautama ...

(Sanskrit: Arada Kalama) and

Uddaka Ramaputta (Sanskrit: Udraka Ramaputra), learning meditation and philosophy, particularly the meditative attainment of "the sphere of nothingness" from the former, and "the sphere of neither perception nor non-perception" from the latter.

Finding these teachings to be insufficient to attain his goal, he turned to the practice of severe

asceticism, which included a strict

fasting

Fasting is the abstention from eating and sometimes drinking. From a purely physiological context, "fasting" may refer to the metabolic status of a person who has not eaten overnight (see " Breakfast"), or to the metabolic state achieved after ...

regime and various forms of

breath control.

[Analayo (2011). ''"A Comparative Study of the Majjhima-nikāya Volume 1 (Introduction, Studies of Discourses 1 to 90),"'' p. 236.] This too fell short of attaining his goal, and then he turned to the meditative practice of ''

dhyana

Dhyana may refer to:

Meditative practices in Indian religions

* Dhyana in Buddhism (Pāli: ''jhāna'')

* Dhyana in Hinduism

* Jain Dhyāna, see Jain meditation

Other

*''Dhyana'', a work by British composer John Tavener (1944-2013)

* ''Dhyana'' ...

''. He famously sat in

meditation

Meditation is a practice in which an individual uses a technique – such as mindfulness, or focusing the mind on a particular object, thought, or activity – to train attention and awareness, and achieve a mentally clear and emotionally calm ...

under a ''

Ficus religiosa'' tree — now called the

Bodhi Tree — in the town of

Bodh Gaya and attained "Awakening" (

Bodhi).

According to various early texts like the ''Mahāsaccaka-sutta,'' and the ''

Samaññaphala Sutta

The Samaññaphala Sutta, "The Fruit of Contemplative Life," is the second discourse (Pali, ''sutta''; Skt., '' sutra'') of the Digha Nikaya.

In terms of narrative, this discourse tells the story of King Ajātasattu, son and successor of King B ...

,'' on awakening, the Buddha gained insight into the workings of karma and his former lives, as well as achieving the ending of the mental defilements (''

asava

Āsava is a Pali term (Sanskrit: Āsrava) that is used in Buddhist scripture, philosophy, and psychology, meaning "influx, canker." It refers to the mental defilements of sensual pleasures, craving for existence, and ignorance, which perpetuate ...

s''), the ending of suffering, and the end of rebirth in

saṃsāra.

This event also brought certainty about the

Middle Way as the right path of spiritual practice to end suffering. As a

fully enlightened Buddha, he attracted followers and founded a ''

Sangha

Sangha is a Sanskrit word used in many Indian languages, including Pali meaning "association", "assembly", "company" or "community"; Sangha is often used as a surname across these languages. It was historically used in a political context t ...

'' (monastic order). He spent the rest of his life teaching the

Dharma he had discovered, and then died, achieving "

final nirvana", at the age of 80 in

Kushinagar

Kushinagar ( Hindustani: or ; Pali: ; Sanskrit: ) is a town in the Kushinagar district in Uttar Pradesh, India. It is an important and popular Buddhist pilgrimage site, where Buddhists believe Gautama Buddha attained ''parinirvana''.

Etym ...

, India.

The Buddha's teachings were propagated by his followers, which in the last centuries of the 1st millennium BCE became various

Buddhist schools of thought, each with its own

basket of texts containing different interpretations and authentic teachings of the Buddha;

[ these over time evolved into many traditions of which the more well known and widespread in the modern era are ]Theravada

''Theravāda'' () ( si, ථේරවාදය, my, ထေရဝါဒ, th, เถรวาท, km, ថេរវាទ, lo, ເຖຣະວາດ, pi, , ) is the most commonly accepted name of Buddhism's oldest existing school. The school' ...

, Mahayana

''Mahāyāna'' (; "Great Vehicle") is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices. Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in India (c. 1st century BCE onwards) and is considered one of the three main existing br ...

and Vajrayana

Vajrayāna ( sa, वज्रयान, "thunderbolt vehicle", "diamond vehicle", or "indestructible vehicle"), along with Mantrayāna, Guhyamantrayāna, Tantrayāna, Secret Mantra, Tantric Buddhism, and Esoteric Buddhism, are names referring t ...

Buddhism.

Worldview

The term "Buddhism" is an occidental neologism, commonly (and "rather roughly" according to Donald S. Lopez Jr.

Donald Sewell Lopez Jr. (born 1952) is the Arthur E. Link Distinguished university professor of Buddhist and Tibetan Studies at the University of Michigan, in the Department of Asian Languages and Cultures.

Life

Lopez was born in Washington, D ...

) used as a translation for the Dharma of the Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha, was a wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism.

According to Buddhist tradition, he was born in L ...

, ''fójiào'' in Chinese, ''bukkyō'' in Japanese, ''nang pa sangs rgyas pa'i chos'' in Tibetan, ''buddhadharma'' in Sanskrit, ''buddhaśāsana'' in Pali.

Four Noble Truths – ''dukkha'' and its ending

The Four Truths express the basic orientation of Buddhism: we crave and cling to impermanent states and things, which is ''dukkha'', "incapable of satisfying" and painful. This keeps us caught in saṃsāra, the endless cycle of repeated

The Four Truths express the basic orientation of Buddhism: we crave and cling to impermanent states and things, which is ''dukkha'', "incapable of satisfying" and painful. This keeps us caught in saṃsāra, the endless cycle of repeated rebirth

Rebirth may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

Film

* ''Rebirth'' (2011 film), a 2011 Japanese drama film

* ''Rebirth'' (2016 film), a 2016 American thriller film

* ''Rebirth'', a documentary film produced by Project Rebirth

* ''The Re ...

, dukkha and dying again.

But there is a way to liberation

Liberation or liberate may refer to:

Film and television

* ''Liberation'' (film series), a 1970–1971 series about the Great Patriotic War

* "Liberation" (''The Flash''), a TV episode

* "Liberation" (''K-9''), an episode

Gaming

* '' Liberati ...

from this endless cycle to the state of nirvana

( , , ; sa, निर्वाण} ''nirvāṇa'' ; Pali: ''nibbāna''; Prakrit: ''ṇivvāṇa''; literally, "blown out", as in an oil lampRichard Gombrich, ''Theravada Buddhism: A Social History from Ancient Benāres to Modern Colombo.' ...

, namely following the Noble Eightfold Path

The Noble Eightfold Path (Pali: ; Sanskrit: ) is an early summary of the path of Buddhist practices leading to liberation from samsara, the painful cycle of rebirth, in the form of nirvana.

The Eightfold Path consists of eight practices: ...

.

The truth of '' dukkha'' is the basic insight that life in this mundane world, with its clinging and craving to impermanent states and things is ''dukkha'', and unsatisfactory.[Ajahn Sumedho, ''The First Noble Truth''](_blank)

(nb: links to index-page; click "The First Noble Truth" for correct page. "the unsatisfactory nature and the general insecurity of all conditioned phenomena"; or "painful". ''Dukkha'' is most commonly translated as "suffering", but this is inaccurate, since it refers not to episodic suffering, but to the intrinsically unsatisfactory nature of temporary states and things, including pleasant but temporary experiences. We expect happiness from states and things which are impermanent, and therefore cannot attain real happiness.

In Buddhism, dukkha is one of the three marks of existence

In Buddhism, the three marks of existence are three characteristics (Pali: tilakkhaṇa; Sanskrit: त्रिलक्षण trilakṣaṇa) of all existence and beings, namely '' aniccā'' (impermanence), '' dukkha'' (commonly translated as "su ...

, along with impermanence

Impermanence, also known as the philosophical problem of change, is a philosophical concept addressed in a variety of religions and philosophies. In Eastern philosophy it is notable for its role in the Buddhist three marks of existence. It ...

and anattā (non-self). Buddhism, like other major Indian religions, asserts that everything is impermanent (anicca), but, unlike them, also asserts that there is no permanent self or soul in living beings (''anattā'').[Anatta Buddhism]

Encyclopædia Britannica (2013)['' ]

Anatta

Encyclopædia Britannica (2013), Quote: "Anatta in Buddhism, the doctrine that there is in humans no permanent, underlying soul. The concept of anatta, or anatman, is a departure from the Hindu belief in atman ("the self").";

'' ' Steven Collins (1994), Religion and Practical Reason (Editors: Frank Reynolds, David Tracy), State Univ of New York Press, , p. 64; "Central to Buddhist soteriology

Soteriology (; el, σωτηρία ' "salvation" from σωτήρ ' "savior, preserver" and λόγος ' "study" or "word") is the study of religious doctrines of salvation. Salvation theory occupies a place of special significance in many religion ...

is the doctrine of not-self (Pali: anattā, Sanskrit: anātman, the opposed doctrine of ātman is central to Brahmanical thought). Put very briefly, this is the uddhistdoctrine that human beings have no soul, no self, no unchanging essence.";

'' ' John C. Plott et al. (2000), ''Global History of Philosophy: The Axial Age'', Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, , p. 63, Quote: "The Buddhist schools reject any Ātman concept. As we have already observed, this is the basic and ineradicable distinction between Hinduism and Buddhism";

'' ' Katie Javanaud (2013)

Is The Buddhist 'No-Self' Doctrine Compatible With Pursuing Nirvana?

Philosophy Now;

'' ' David Loy (1982), "Enlightenment in Buddhism and Advaita Vedanta: Are Nirvana and Moksha the Same?", ''International Philosophical Quarterly'', Volume 23, Issue 1, pp. 65–74 The ignorance or misperception ('' avijjā'') that anything is permanent or that there is self in any being is considered a wrong understanding, and the primary source of clinging and dukkha.

The cycle of rebirth

Saṃsāra

''Saṃsāra'' means "wandering" or "world", with the connotation of cyclic, circuitous change. It refers to the theory of rebirth and "cyclicality of all life, matter, existence", a fundamental assumption of Buddhism, as with all major Indian religions. Samsara in Buddhism is considered to be '' dukkha'', unsatisfactory and painful, perpetuated by desire and '' avidya'' (ignorance), and the resulting karma

Karma (; sa, कर्म}, ; pi, kamma, italic=yes) in Sanskrit means an action, work, or deed, and its effect or consequences. In Indian religions, the term more specifically refers to a principle of cause and effect, often descriptivel ...

. Liberation from this cycle of existence, ''nirvana'', has been the foundation and the most important historical justification of Buddhism.

Buddhist texts assert that rebirth can occur in six realms of existence, namely three good realms (heavenly, demi-god, human) and three evil realms (animal, hungry ghosts, hellish). Samsara ends if a person attains nirvana

( , , ; sa, निर्वाण} ''nirvāṇa'' ; Pali: ''nibbāna''; Prakrit: ''ṇivvāṇa''; literally, "blown out", as in an oil lampRichard Gombrich, ''Theravada Buddhism: A Social History from Ancient Benāres to Modern Colombo.' ...

, the "blowing out" of the afflictions through insight into impermanence

Impermanence, also known as the philosophical problem of change, is a philosophical concept addressed in a variety of religions and philosophies. In Eastern philosophy it is notable for its role in the Buddhist three marks of existence. It ...

and " non-self".

Rebirth

Rebirth refers to a process whereby beings go through a succession of lifetimes as one of many possible forms of sentient life, each running from conception to death. In Buddhist thought, this rebirth does not involve a

Rebirth refers to a process whereby beings go through a succession of lifetimes as one of many possible forms of sentient life, each running from conception to death. In Buddhist thought, this rebirth does not involve a soul

In many religious and philosophical traditions, there is a belief that a soul is "the immaterial aspect or essence of a human being".

Etymology

The Modern English noun '' soul'' is derived from Old English ''sāwol, sāwel''. The earliest atte ...

or any fixed substance. This is because the Buddhist doctrine of anattā (Sanskrit: ''anātman'', no-self doctrine) rejects the concepts of a permanent self or an unchanging, eternal soul found in other religions.pudgala

In Jainism, Pudgala (or ') is one of the six Dravyas, or aspects of reality that fabricate the world we live in. The six ''dravya''s include the jiva and the fivefold divisions of ajiva (non-living) category: ''dharma'' (motion), ''adharma'' ( ...

'') which migrates from one life to another. The majority of Buddhist traditions, in contrast, assert that vijñāna

''Vijñāna'' ( sa, विज्ञान) or ''viññāa'' ( pi, विञ्ञाण)As is standard in WP articles, the Pali term ''viññāa'' will be used when discussing the Pali literature, and the Sanskrit word ''vijñāna'' will be used ...

(a person's consciousness) though evolving, exists as a continuum and is the mechanistic basis of what undergoes the rebirth process. The quality of one's rebirth depends on the merit

Merit may refer to:

Religion

* Merit (Christianity)

* Merit (Buddhism)

* Punya (Hinduism)

* Imputed righteousness in Reformed Christianity

Companies and brands

* Merit (cigarette), a brand of cigarettes made by Altria

* Merit Energy Company, ...

or demerit gained by one's karma (i.e. actions), as well as that accrued on one's behalf by a family member. Buddhism also developed a complex cosmology to explain the various realms or planes of rebirth.

Karma

In Buddhism, karma

Karma (; sa, कर्म}, ; pi, kamma, italic=yes) in Sanskrit means an action, work, or deed, and its effect or consequences. In Indian religions, the term more specifically refers to a principle of cause and effect, often descriptivel ...

(from Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the late ...

: "action, work") drives '' saṃsāra'' – the endless cycle of suffering and rebirth for each being. Good, skilful deeds (Pāli: ''kusala'') and bad, unskilful deeds (Pāli: ''akusala'') produce "seeds" in the unconscious receptacle (''ālaya'') that mature later either in this life or in a subsequent rebirth

Rebirth may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

Film

* ''Rebirth'' (2011 film), a 2011 Japanese drama film

* ''Rebirth'' (2016 film), a 2016 American thriller film

* ''Rebirth'', a documentary film produced by Project Rebirth

* ''The Re ...

. The existence of karma is a core belief in Buddhism, as with all major Indian religions, and it implies neither fatalism nor that everything that happens to a person is caused by karma.

A central aspect of Buddhist theory of karma is that intent (''cetanā

Cetanā (Sanskrit, Pali; Tibetan Wylie: sems pa) is a Buddhist term commonly translated as "volition", "intention", "directionality", etc. It can be defined as a mental factor that moves or urges the mind in a particular direction, toward a specifi ...

'') matters and is essential to bring about a consequence or '' phala'' "fruit" or vipāka "result". However, good or bad karma accumulates even if there is no physical action, and just having ill or good thoughts creates karmic seeds; thus, actions of body, speech or mind all lead to karmic seeds. In the Buddhist traditions, life aspects affected by the law of karma in past and current births of a being include the form of rebirth, realm of rebirth, social class, character and major circumstances of a lifetime. It operates like the laws of physics, without external intervention, on every being in all six realms of existence including human beings and gods.

A notable aspect of the karma theory in Buddhism is merit transfer.

Liberation

The cessation of the '' kleshas'' and the attainment of

The cessation of the '' kleshas'' and the attainment of nirvana

( , , ; sa, निर्वाण} ''nirvāṇa'' ; Pali: ''nibbāna''; Prakrit: ''ṇivvāṇa''; literally, "blown out", as in an oil lampRichard Gombrich, ''Theravada Buddhism: A Social History from Ancient Benāres to Modern Colombo.' ...

(''nibbāna''), with which the cycle of rebirth ends, has been the primary and the soteriological

Soteriology (; el, wikt:σωτηρία, σωτηρία ' "salvation" from wikt:σωτήρ, σωτήρ ' "savior, preserver" and wikt:λόγος, λόγος ' "study" or "word") is the study of Doctrine, religious doctrines of salvation. Salvation ...

goal of the Buddhist path for monastic life since the time of the Buddha. The term "path" is usually taken to mean the Noble Eightfold Path

The Noble Eightfold Path (Pali: ; Sanskrit: ) is an early summary of the path of Buddhist practices leading to liberation from samsara, the painful cycle of rebirth, in the form of nirvana.

The Eightfold Path consists of eight practices: ...

, but other versions of "the path" can also be found in the Nikayas. In some passages in the Pali Canon, a distinction is being made between right knowledge or insight (''sammā-ñāṇa''), and right liberation or release (''sammā-vimutti''), as the means to attain cessation and liberation.

Nirvana literally means "blowing out, quenching, becoming extinguished".

Dependent arising

''Pratityasamutpada'', also called "dependent arising, or dependent origination", is the Buddhist theory to explain the nature and relations of being, becoming, existence and ultimate reality. Buddhism asserts that there is nothing independent, except the state of nirvana. All physical and mental states depend on and arise from other pre-existing states, and in turn from them arise other dependent states while they cease.

The 'dependent arisings' have a causal conditioning, and thus ''Pratityasamutpada'' is the Buddhist belief that causality is the basis of ontology

In metaphysics, ontology is the philosophical study of being, as well as related concepts such as existence, becoming, and reality.

Ontology addresses questions like how entities are grouped into categories and which of these entities exi ...

, not a creator God nor the ontological Vedic concept called universal Self (Brahman

In Hinduism, ''Brahman'' ( sa, ब्रह्मन्) connotes the highest universal principle, the ultimate reality in the universe.P. T. Raju (2006), ''Idealistic Thought of India'', Routledge, , page 426 and Conclusion chapter part X ...

) nor any other 'transcendent creative principle'. However, Buddhist thought does not understand causality in terms of Newtonian mechanics; rather it understands it as conditioned arising. In Buddhism, dependent arising refers to conditions created by a plurality of causes that necessarily co-originate a phenomenon within and across lifetimes, such as karma in one life creating conditions that lead to rebirth in one of the realms of existence for another lifetime.Twelve Nidānas

Twelve or 12 may refer to:

* 12 (number)

* December, the twelfth and final month of the year

Years

* 12 BC

* AD 12

* 1912

* 2012

Film

* ''Twelve'' (2010 film), based on the 2002 novel

* ''12'' (2007 film), by Russian director and actor Nikit ...

or "twelve links". It states that because Avidyā (ignorance) exists, Saṃskāras (karmic formations) exist; because Saṃskāras exist therefore Vijñāna

''Vijñāna'' ( sa, विज्ञान) or ''viññāa'' ( pi, विञ्ञाण)As is standard in WP articles, the Pali term ''viññāa'' will be used when discussing the Pali literature, and the Sanskrit word ''vijñāna'' will be used ...

(consciousness) exists; and in a similar manner it links Nāmarūpa

Nāmarūpa ( sa, नामरूप) is used in Buddhism to refer to the constituents of a living being: ''nāma'' is typically considered to refer to the mental component of the person, while ''rūpa'' refers to the physical.

''Nāmarūpa'' is ...

(the sentient body), Ṣaḍāyatana (our six senses), Sparśa

Sparśa (Sanskrit; Pali: ''phassa'') is a Sanskrit/Indian term that is translated as "contact", "touching", "sensation", "sense impression", etc. It is defined as the coming together of three factors: the sense organ, the sense object, and sen ...

(sensory stimulation), Vedanā

Vedanā ( Pāli and Sanskrit: वेदना) is an ancient term traditionally translated as either " feeling" or "sensation." In general, ''vedanā'' refers to the pleasant, unpleasant and neutral sensations that occur when our internal sense ...

(feeling), Taṇhā

(Pāli; Sanskrit: tṛ́ṣṇā तृष्णा IPA

IPA commonly refers to:

* India pale ale, a style of beer

* International Phonetic Alphabet, a system of phonetic notation

* Isopropyl alcohol, a chemical compound

IPA may also refer ...

(craving), Upādāna

''Upādāna'' is a Sanskrit and Pali word that means "fuel, material cause, substrate that is the source and means for keeping an active process energized". It is also an important Buddhist concept referring to "attachment, clinging, grasping". ...

(grasping), Bhava

The Sanskrit word bhava (भव) means being, worldly existence, becoming, birth, be, production, origin,Monier Monier-Williams (1899), Sanskrit English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, Archiveभव bhava but also habitual or emotional te ...

(becoming), Jāti

''Jāti'' is the term traditionally used to describe a cohesive group of people in the Indian subcontinent, like a tribe, community, clan, sub-clan, or a religious sect. Each Jāti typically has an association with an occupation, geography or t ...

(birth), and Jarāmaraṇa

is Sanskrit and Pāli for "old age" () and "death" ().; Quote: "death, as ending this (visible) existence, physical death". In Buddhism, jaramarana is associated with the inevitable decay and death-related suffering of all beings prior to their r ...

(old age, death, sorrow, and pain). By breaking the circuitous links of the Twelve Nidanas, Buddhism asserts that liberation from these endless cycles of rebirth and dukkha can be attained.

Not-Self and Emptiness

A related doctrine in Buddhism is that of ''anattā'' (Pali) or ''anātman'' (Sanskrit). It is the view that there is no unchanging, permanent self, soul or essence in phenomena. The Buddha and Buddhist philosophers who follow him such as Vasubandhu and Buddhaghosa, generally argue for this view by analyzing the person through the schema of the five aggregates

(Sanskrit) or (Pāḷi) means "heaps, aggregates, collections, groupings". In Buddhism, it refers to the five aggregates of clinging (), the five material and mental factors that take part in the rise of craving and clinging. They are also ...

, and then attempting to show that none of these five components of personality can be permanent or absolute. This can be seen in Buddhist discourses such as the '' Anattalakkhana Sutta''.

"Emptiness" or "voidness" (Skt'': Śūnyatā'', Pali: ''Suññatā)'', is a related concept with many different interpretations throughout the various Buddhisms. In early Buddhism, it was commonly stated that all five aggregates are void (''rittaka''), hollow (''tucchaka''), coreless (''asāraka''), for example as in the ''Pheṇapiṇḍūpama Sutta'' (SN 22:95). Similarly, in Theravada Buddhism, it often means that the five aggregates are empty of a Self.

Emptiness is a central concept in Mahāyāna Buddhism, especially in Nagarjuna

Nāgārjuna . 150 – c. 250 CE (disputed)was an Indian Mahāyāna Buddhist thinker, scholar-saint and philosopher. He is widely considered one of the most important Buddhist philosophers.Garfield, Jay L. (1995), ''The Fundamental Wisdom of ...

's Madhyamaka

Mādhyamaka ("middle way" or "centrism"; ; Tibetan: དབུ་མ་པ ; ''dbu ma pa''), otherwise known as Śūnyavāda ("the emptiness doctrine") and Niḥsvabhāvavāda ("the no ''svabhāva'' doctrine"), refers to a tradition of Buddhi ...

school, and in the '' Prajñāpāramitā sutras''. In Madhyamaka philosophy, emptiness is the view which holds that all phenomena ( ''dharmas'') are without any ''svabhava

Svabhava ( sa, स्वभाव, svabhāva; pi, सभाव, sabhāva; ; ) literally means "own-being" or "own-becoming". It is the intrinsic nature, essential nature or essence of beings.

The concept and term ''svabhāva'' are frequently enco ...

'' (literally "own-nature" or "self-nature"), and are thus without any underlying essence, and so are "empty" of being independent. This doctrine sought to refute the heterodox theories of ''svabhava'' circulating at the time.

The Three Jewels

All forms of Buddhism revere and take spiritual refuge in the "three jewels" (''triratna''): Buddha, Dharma and Sangha.

All forms of Buddhism revere and take spiritual refuge in the "three jewels" (''triratna''): Buddha, Dharma and Sangha.

Buddha

While all varieties of Buddhism revere "Buddha" and "buddhahood", they have different views on what these are. Regardless of their interpretation, the concept of Buddha is central to all forms of Buddhism.

In Theravada Buddhism, a Buddha is someone who has become awake through their own efforts and insight. They have put an end to their cycle of rebirths and have ended all unwholesome mental states which lead to bad action and thus are morally perfected.[Crosby, Kate (2013). ''"Theravada Buddhism: Continuity, Diversity, and Identity,"'' p. 16. John Wiley & Sons.] While subject to the limitations of the human body in certain ways (for example, in the early texts, the Buddha suffers from backaches), a Buddha is said to be "deep, immeasurable, hard-to-fathom as is the great ocean," and also has immense psychic powers (abhijñā

Abhijñā ( sa, अभिज्ञा; Pali pronunciation: ''abhiññā''; bo, མངོན་ཤེས ''mngon shes''; ) is a Buddhist term generally translated as "direct knowledge", "higher knowledge"Rhys Davids & Stede (1921-5), pp. 64-65. o ...

). Theravada generally sees Gautama Buddha (the historical Buddha Sakyamuni) as the only Buddha of the current era.

Mahāyāna Buddhism meanwhile, has a vastly expanded cosmology

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', and in 1731 taken up in Latin by German philosopher ...

, with various Buddhas and other holy beings (''aryas'') residing in different realms. Mahāyāna texts not only revere numerous Buddhas besides Shakyamuni, such as Amitabha and Vairocana

Vairocana (also Mahāvairocana, sa, वैरोचन) is a cosmic buddha from Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism. Vairocana is often interpreted, in texts like the ''Avatamsaka Sutra'', as the dharmakāya of the historical Gautama Buddha. In East ...

, but also see them as transcendental or supramundane (''lokuttara'') beings. Mahāyāna Buddhism holds that these other Buddhas in other realms can be contacted and are able to benefit beings in this world. In Mahāyāna, a Buddha is a kind of "spiritual king", a "protector of all creatures" with a lifetime that is countless of eons long, rather than just a human teacher who has transcended the world after death. Shakyamuni's life and death on earth is then usually understood as a "mere appearance" or "a manifestation skilfully projected into earthly life by a long-enlightened transcendent being, who is still available to teach the faithful through visionary experiences."

Dharma

The second of the three jewels is "Dharma" (Pali: Dhamma), which in Buddhism refers to the Buddha's teaching, which includes all of the main ideas outlined above. While this teaching reflects the true nature of reality, it is not a belief to be clung to, but a pragmatic teaching to be put into practice. It is likened to a raft which is "for crossing over" (to nirvana) not for holding on to. It also refers to the universal law and cosmic order which that teaching both reveals and relies upon. It is an everlasting principle which applies to all beings and worlds. In that sense it is also the ultimate truth and reality about the universe, it is thus "the way that things really are."

Sangha

The third "jewel" which Buddhists take refuge in is the "Sangha", which refers to the monastic community of monks and nuns who follow Gautama Buddha's monastic discipline which was "designed to shape the Sangha as an ideal community, with the optimum conditions for spiritual growth." The Sangha consists of those who have chosen to follow the Buddha's ideal way of life, which is one of celibate monastic renunciation with minimal material possessions (such as an alms bowl and robes).

The Sangha is seen as important because they preserve and pass down Buddha Dharma. As Gethin states "the Sangha lives the teaching, preserves the teaching as Scriptures and teaches the wider community. Without the Sangha there is no Buddhism." The Sangha also acts as a "field of merit" for laypersons, allowing them to make spiritual merit or goodness by donating to the Sangha and supporting them. In return, they keep their duty to preserve and spread the Dharma everywhere for the good of the world.

There is also a separate definition of Sangha, referring to those who have attained any stage of awakening, whether or not they are monastics. This sangha is called the ''āryasaṅgha'' "noble Sangha". All forms of Buddhism generally reveres these '' āryas'' (Pali: ''ariya'', "noble ones" or "holy ones") who are spiritually attained beings. Aryas have attained the fruits of the Buddhist path. Becoming an arya is a goal in most forms of Buddhism. The ''āryasaṅgha'' includes holy beings such as

The third "jewel" which Buddhists take refuge in is the "Sangha", which refers to the monastic community of monks and nuns who follow Gautama Buddha's monastic discipline which was "designed to shape the Sangha as an ideal community, with the optimum conditions for spiritual growth." The Sangha consists of those who have chosen to follow the Buddha's ideal way of life, which is one of celibate monastic renunciation with minimal material possessions (such as an alms bowl and robes).

The Sangha is seen as important because they preserve and pass down Buddha Dharma. As Gethin states "the Sangha lives the teaching, preserves the teaching as Scriptures and teaches the wider community. Without the Sangha there is no Buddhism." The Sangha also acts as a "field of merit" for laypersons, allowing them to make spiritual merit or goodness by donating to the Sangha and supporting them. In return, they keep their duty to preserve and spread the Dharma everywhere for the good of the world.

There is also a separate definition of Sangha, referring to those who have attained any stage of awakening, whether or not they are monastics. This sangha is called the ''āryasaṅgha'' "noble Sangha". All forms of Buddhism generally reveres these '' āryas'' (Pali: ''ariya'', "noble ones" or "holy ones") who are spiritually attained beings. Aryas have attained the fruits of the Buddhist path. Becoming an arya is a goal in most forms of Buddhism. The ''āryasaṅgha'' includes holy beings such as bodhisattva

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva ( ; sa, 𑀩𑁄𑀥𑀺𑀲𑀢𑁆𑀢𑁆𑀯 (Brahmī), translit=bodhisattva, label=Sanskrit) or bodhisatva is a person who is on the path towards bodhi ('awakening') or Buddhahood.

In the Early Buddhist schools ...

s, arhat

In Buddhism, an ''arhat'' (Sanskrit: अर्हत्) or ''arahant'' (Pali: अरहन्त्, 𑀅𑀭𑀳𑀦𑁆𑀢𑁆) is one who has gained insight into the true nature of existence and has achieved ''Nirvana'' and liberated ...

s and stream-enterers.

Other key Mahāyāna views

Mahāyāna Buddhism also differs from Theravada and the other schools of early Buddhism in promoting several unique doctrines which are contained in Mahāyāna sutras and philosophical treatises.

One of these is the unique interpretation of emptiness and dependent origination found in the Madhyamaka school. Another very influential doctrine for Mahāyāna is the main philosophical view of the Yogācāra

Yogachara ( sa, योगाचार, IAST: '; literally "yoga practice"; "one whose practice is yoga") is an influential tradition of Buddhist philosophy and psychology emphasizing the study of cognition, perception, and consciousness through t ...

school variously, termed ''Vijñaptimātratā-vāda'' ("the doctrine that there are only ideas" or "mental impressions") or ''Vijñānavāda'' ("the doctrine of consciousness"). According to Mark Siderits, what classical Yogācāra thinkers like Vasubandhu had in mind is that we are only ever aware of mental images or impressions, which may appear as external objects, but "there is actually no such thing outside the mind." There are several interpretations of this main theory, many scholars see it as a type of Idealism, others as a kind of phenomenology.

Another very influential concept unique to Mahāyāna is that of "Buddha-nature" (''buddhadhātu'') or "Tathagata-womb" (''tathāgatagarbha''). Buddha-nature is a concept found in some 1st-millennium CE Buddhist texts, such as the ''Tathāgatagarbha sūtras

The Tathāgatagarbha sūtras are a group of Mahayana sutras that present the concept of the "womb" or "embryo" (''garbha'') of the tathāgata, the buddha. Every sentient being has the possibility to attain Buddhahood because of the ''tathāgata ...

''. According to Paul Williams these Sutras suggest that 'all sentient beings contain a Tathagata' as their 'essence, core inner nature, Self'. According to Karl Brunnholzl "the earliest mahayana sutras that are based on and discuss the notion of tathāgatagarbha as the buddha potential that is innate in all sentient beings began to appear in written form in the late second and early third century." For some, the doctrine seems to conflict with the Buddhist anatta doctrine (non-Self), leading scholars to posit that the ''Tathāgatagarbha Sutras'' were written to promote Buddhism to non-Buddhists. This can be seen in texts like the ''Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra

The ''Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra'' (Sanskrit, "Discourse of the Descent into Laṅka" bo, ལང་ཀར་བཤེགས་པའི་མདོ་, Chinese:入楞伽經) is a prominent Mahayana Buddhist sūtra. This sūtra recounts a teachi ...

'', which state that Buddha-nature is taught to help those who have fear when they listen to the teaching of anatta. Buddhist texts like the ''Ratnagotravibhāga

The ''Ratnagotravibhāga'' (Sanskrit, abbreviated as RGV, meaning: ''Analysis of the Jeweled Lineage, Investigating the Jewel Disposition'') and its ''vyākhyā'' commentary (abbreviated RGVV to refer to the RGV verses along with the embedded comm ...

'' clarify that the "Self" implied in ''Tathagatagarbha'' doctrine is actually " not-self". Various interpretations of the concept have been advanced by Buddhist thinkers throughout the history of Buddhist thought and most attempt to avoid anything like the Hindu Atman doctrine.

These Indian Buddhist ideas, in various synthetic ways, form the basis of subsequent Mahāyāna philosophy in Tibetan Buddhism and East Asian Buddhism.

Paths to liberation

The '' Bodhipakkhiyādhammā'' are seven lists of qualities or factors that contribute to awakening (''bodhi''). Each list is a short summary of the Buddhist path, and the seven lists substantialy overlap. The best-known list in the West is the Noble Eightfold Path

The Noble Eightfold Path (Pali: ; Sanskrit: ) is an early summary of the path of Buddhist practices leading to liberation from samsara, the painful cycle of rebirth, in the form of nirvana.

The Eightfold Path consists of eight practices: ...

, but a wide variety of paths and models of progress have been used and described in the different Buddhist traditions. However, they generally share basic practices such as ''sila'' (ethics), ''samadhi'' (meditation, ''dhyana'') and ''prajña'' (wisdom), which are known as the three trainings. An important additional practice is a kind and compassionate attitude toward every living being and the world. Devotion

Devotion or Devotions may refer to:

Religion

* Faith, confidence or trust in a person, thing, or concept

* Anglican devotions, private prayers and practices used by Anglican Christians

* Buddhist devotion, commitment to religious observance

* Cat ...

is also important in some Buddhist traditions, and in the Tibetan traditions visualisations of deities and mandalas are important. The value of textual study is regarded differently in the various Buddhist traditions. It is central to Theravada and highly important to Tibetan Buddhism, while the Zen tradition takes an ambiguous stance.

An important guiding principle of Buddhist practice is the Middle Way (''madhyamapratipad''). It was a part of Buddha's first sermon, where he presented the Noble Eightfold Path

The Noble Eightfold Path (Pali: ; Sanskrit: ) is an early summary of the path of Buddhist practices leading to liberation from samsara, the painful cycle of rebirth, in the form of nirvana.

The Eightfold Path consists of eight practices: ...

that was a 'middle way' between the extremes of asceticism and hedonistic sense pleasures. In Buddhism, states Harvey, the doctrine of "dependent arising" (conditioned arising, ''pratītyasamutpāda'') to explain rebirth is viewed as the 'middle way' between the doctrines that a being has a "permanent soul" involved in rebirth (eternalism) and "death is final and there is no rebirth" (annihilationism).

Paths to liberation in the early texts

A common presentation style of the path (''mārga'') to liberation in the Early Buddhist Texts

Early Buddhist texts (EBTs), early Buddhist literature or early Buddhist discourses are parallel texts shared by the early Buddhist schools. The most widely studied EBT material are the first four Pali Nikayas, as well as the corresponding Chines ...

is the "graduated talk", in which the Buddha lays out a step by step training.

In the early texts, numerous different sequences of the gradual path can be found.[Bucknell, Rod, "The Buddhist Path to Liberation: An Analysis of the Listing of Stages", ''The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies'' Volume 7, Number 2, 1984] One of the most important and widely used presentations among the various Buddhist schools is The Noble Eightfold Path

The Noble Eightfold Path (Pali: ; Sanskrit: ) is an early summary of the path of Buddhist practices leading to liberation from samsara, the painful cycle of rebirth, in the form of nirvana.

The Eightfold Path consists of eight practices: ...

, or "Eightfold Path of the Noble Ones" (Skt. '''āryāṣṭāṅgamārga). This can be found in various discourses, most famously in the ''Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta

The ''Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta'' (Pali; Sanskrit: ''Dharmacakrapravartana Sūtra''; English: ''The Setting in Motion of the Wheel of the Dharma Sutta'' or ''Promulgation of the Law Sutta'') is a Buddhist text that is considered by Buddhists t ...

'' (The discourse on the turning of the Dharma wheel

The dharmachakra (Sanskrit: धर्मचक्र; Pali: ''dhammacakka'') or wheel of dharma is a widespread symbol used in Indian religions such as Hinduism, Jainism, and especially Buddhism.John C. Huntington, Dina Bangdel, ''The Circle o ...

).

Other suttas such as the ''Tevijja Sutta'', and the ''Cula-Hatthipadopama-sutta'' give a different outline of the path, though with many similar elements such as ethics and meditation.

Noble Eightfold Path

The Eightfold Path consists of a set of eight interconnected factors or conditions, that when developed together, lead to the cessation of dukkha. These eight factors are: Right View (or Right Understanding), Right Intention (or Right Thought), Right Speech, Right Action, Right Livelihood, Right Effort, Right Mindfulness, and Right Concentration.

This Eightfold Path is the fourth of the Four Noble Truths, and asserts the path to the cessation of ''dukkha'' (suffering, pain, unsatisfactoriness). The path teaches that the way of the enlightened ones stopped their craving, clinging and karmic

Karma (; sa, कर्म}, ; pi, kamma, italic=yes) in Sanskrit means an action, work, or deed, and its effect or consequences. In Indian religions, the term more specifically refers to a principle of cause and effect, often descriptively ...

accumulations, and thus ended their endless cycles of rebirth and suffering.

The Noble Eightfold Path is grouped into three basic divisions, as follows:

Common Buddhist practices

Hearing and learning the Dharma

In various suttas which present the graduated path taught by the Buddha, such as the ''Samaññaphala Sutta

The Samaññaphala Sutta, "The Fruit of Contemplative Life," is the second discourse (Pali, ''sutta''; Skt., '' sutra'') of the Digha Nikaya.

In terms of narrative, this discourse tells the story of King Ajātasattu, son and successor of King B ...

'' and the ''Cula-Hatthipadopama Sutta,'' the first step on the path is hearing the Buddha teach the Dharma. This then said to lead to the acquiring of confidence or faith in the Buddha's teachings.

Refuge

Traditionally, the first step in most Buddhist schools requires taking of the "Three Refuges", also called the Three Jewels (Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the late ...

: ''triratna'', Pali

Pali () is a Middle Indo-Aryan liturgical language native to the Indian subcontinent. It is widely studied because it is the language of the Buddhist ''Pāli Canon'' or '' Tipiṭaka'' as well as the sacred language of '' Theravāda'' Buddh ...

: ''tiratana'') as the foundation of one's religious practice. This practice may have been influenced by the Brahmanical

The historical Vedic religion (also known as Vedicism, Vedism or ancient Hinduism and subsequently Brahmanism (also spelled as Brahminism)), constituted the religious ideas and practices among some Indo-Aryan peoples of northwest Indian Subco ...

motif of the triple refuge, found in the ''Rigveda

The ''Rigveda'' or ''Rig Veda'' ( ', from ' "praise" and ' "knowledge") is an ancient Indian collection of Vedic Sanskrit hymns (''sūktas''). It is one of the four sacred canonical Hindu texts ('' śruti'') known as the Vedas. Only one ...

'' 9.97.47, ''Rigveda'' 6.46.9 and '' Chandogya Upanishad'' 2.22.3–4. Tibetan Buddhism sometimes adds a fourth refuge, in the '' lama''. The three refuges are believed by Buddhists to be protective and a form of reverence.

The ancient formula which is repeated for taking refuge affirms that "I go to the Buddha as refuge, I go to the Dhamma as refuge, I go to the Sangha as refuge." Reciting the three refuges, according to Harvey, is considered not as a place to hide, rather a thought that "purifies, uplifts and strengthens the heart".

''Śīla'' – Buddhist ethics

''Śīla'' (Sanskrit) or ''sīla'' (Pāli) is the concept of "moral virtues", that is the second group and an integral part of the Noble Eightfold Path. It generally consists of right speech, right action and right livelihood.

One of the most basic forms of ethics in Buddhism is the taking of "precepts". This includes the Five Precepts for laypeople, Eight or Ten Precepts for monastic life, as well as rules of Dhamma (''Vinaya'' or ''Patimokkha'') adopted by a monastery.

Other important elements of Buddhist ethics include giving or charity (''dāna''), Mettā (Good-Will), Heedfulness ( Appamada), 'self-respect' ( Hri) and 'regard for consequences' (

''Śīla'' (Sanskrit) or ''sīla'' (Pāli) is the concept of "moral virtues", that is the second group and an integral part of the Noble Eightfold Path. It generally consists of right speech, right action and right livelihood.

One of the most basic forms of ethics in Buddhism is the taking of "precepts". This includes the Five Precepts for laypeople, Eight or Ten Precepts for monastic life, as well as rules of Dhamma (''Vinaya'' or ''Patimokkha'') adopted by a monastery.

Other important elements of Buddhist ethics include giving or charity (''dāna''), Mettā (Good-Will), Heedfulness ( Appamada), 'self-respect' ( Hri) and 'regard for consequences' (Apatrapya

Apatrapya (Sanskrit, also ''apatrāpya''; Pali: ottappa; Tibetan Wylie: ''khrel yod pa'') is a Buddhist term translated as "decorum" or "shame". It is defined as shunning unwholesome actions so as to not be reproached by others of good character.G ...

).

Precepts

Buddhist scriptures explain the five precepts ( pi, italic=yes, pañcasīla; sa, italic=yes, pañcaśīla) as the minimal standard of Buddhist morality. It is the most important system of morality in Buddhism, together with the monastic rules

Monasticism (from Ancient Greek , , from , , 'alone'), also referred to as monachism, or monkhood, is a religious way of life in which one renounces worldly pursuits to devote oneself fully to spiritual work. Monastic life plays an important rol ...

.adultery

Adultery (from Latin ''adulterium'') is extramarital sex that is considered objectionable on social, religious, moral, or legal grounds. Although the sexual activities that constitute adultery vary, as well as the social, religious, and legal ...

, as well as rape and incest. It also applies to sex with those who are legally under the protection of a guardian. It is also interpreted in different ways in the varying Buddhist cultures.

# "I undertake the training-precept to abstain from false speech." According to Harvey this includes "any form of lying, deception or exaggeration...even non-verbal deception by gesture or other indication...or misleading statements." The precept is often also seen as including other forms of wrong speech such as "divisive speech, harsh, abusive, angry words, and even idle chatter."

# "I undertake the training-precept to abstain from alcoholic drink or drugs that are an opportunity for heedlessness." According to Harvey, intoxication is seen as a way to mask rather than face the sufferings of life. It is seen as damaging to one's mental clarity, mindfulness and ability to keep the other four precepts.

Undertaking and upholding the five precepts is based on the principle of non-harming (Pāli

Pali () is a Middle Indo-Aryan liturgical language native to the Indian subcontinent. It is widely studied because it is the language of the Buddhist ''Pāli Canon'' or '' Tipiṭaka'' as well as the sacred language of ''Theravāda'' Buddhi ...

and sa, ahiṃsa, italic=yes). The Pali Canon

The Pāli Canon is the standard collection of scriptures in the Theravada Buddhist tradition, as preserved in the Pāli language. It is the most complete extant early Buddhist canon. It derives mainly from the Tamrashatiya school.

During t ...

recommends one to compare oneself with others, and on the basis of that, not to hurt others. Compassion and a belief in karmic retribution

Karma (Sanskrit, also ''karman'', Pāli: ''kamma'') is a Sanskrit term that literally means "action" or "doing". In the Buddhist tradition, ''karma'' refers to action driven by intention (''cetanā'') which leads to future consequences. Those i ...

form the foundation of the precepts. Undertaking the five precepts is part of regular lay devotional practice, both at home and at the local temple. However, the extent to which people keep them differs per region and time. They are sometimes referred to as the ''śrāvakayāna

Śrāvakayāna ( sa, श्रावकयान; pi, सावकयान; ) is one of the three '' yānas'' known to Indian Buddhism. It translates literally as the "vehicle of listeners .e. disciples. Historically it was the most common te ...

precepts'' in the Mahāyāna

''Mahāyāna'' (; "Great Vehicle") is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices. Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in India (c. 1st century BCE onwards) and is considered one of the three main existing br ...

tradition, contrasting them with the ''bodhisattva'' precepts.

Vinaya

Vinaya is the specific code of conduct for a ''sangha'' of monks or nuns. It includes the Patimokkha, a set of 227 offences including 75 rules of decorum for monks, along with penalties for transgression, in the Theravadin tradition. The precise content of the ''

Vinaya is the specific code of conduct for a ''sangha'' of monks or nuns. It includes the Patimokkha, a set of 227 offences including 75 rules of decorum for monks, along with penalties for transgression, in the Theravadin tradition. The precise content of the ''Vinaya Pitaka

The Vinaya ( Pali & Sanskrit: विनय) is the division of the Buddhist canon ('' Tripitaka'') containing the rules and procedures that govern the Buddhist Sangha (community of like-minded ''sramanas''). Three parallel Vinaya traditions rem ...

'' (scriptures on the Vinaya) differs in different schools and tradition, and different monasteries set their own standards on its implementation. The list of ''pattimokkha'' is recited every fortnight in a ritual gathering of all monks. Buddhist text with vinaya rules for monasteries have been traced in all Buddhist traditions, with the oldest surviving being the ancient Chinese translations.

Monastic communities in the Buddhist tradition cut normal social ties to family and community, and live as "islands unto themselves". Within a monastic fraternity, a ''sangha'' has its own rules. A monk abides by these institutionalised rules, and living life as the vinaya prescribes it is not merely a means, but very nearly the end in itself. Transgressions by a monk on ''Sangha'' vinaya rules invites enforcement, which can include temporary or permanent expulsion.

Restraint and renunciation

Another important practice taught by the Buddha is the restraint of the senses (''indriyasamvara''). In the various graduated paths, this is usually presented as a practice which is taught prior to formal sitting meditation, and which supports meditation by weakening sense desires that are a hindrance to meditation.

Another important practice taught by the Buddha is the restraint of the senses (''indriyasamvara''). In the various graduated paths, this is usually presented as a practice which is taught prior to formal sitting meditation, and which supports meditation by weakening sense desires that are a hindrance to meditation.[Anālayo (2003). "Satipaṭṭhāna: The Direct Path to Realization," p. 71. Windhorse Publications.] According to Anālayo, sense restraint is when one "guards the sense doors in order to prevent sense impressions from leading to desires and discontent."[Anālayo (2003). "Satipaṭṭhāna: The Direct Path to Realization," p. 225. Windhorse Publications.] This practice is said to give rise to an inner peace and happiness which forms a basis for concentration and insight.nekkhamma

''Nekkhamma'' (Sanskrit: नैष्क्राम्य, Naiṣkrāmya) is a Pali word generally translated as "renunciation" or "the pleasure of renunciation" while also conveying more specifically "giving up the world and leading a holy life" ...

''). Generally, renunciation is the giving up of actions and desires that are seen as unwholesome on the path, such as lust for sensuality and worldly things. Renunciation can be cultivated in different ways. The practice of giving for example, is one form of cultivating renunciation. Another one is the giving up of lay life and becoming a monastic (''bhiksu'' o ''bhiksuni''). Practicing celibacy (whether for life as a monk, or temporarily) is also a form of renunciation. Many Jataka

The Jātakas (meaning "Birth Story", "related to a birth") are a voluminous body of literature native to India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, th ...

stories such as the focus on how the Buddha practiced renunciation in past lives.

One way of cultivating renunciation taught by the Buddha is the contemplation (''anupassana'') of the "dangers" (or "negative consequences") of sensual pleasure (''kāmānaṃ ādīnava''). As part of the graduated discourse, this contemplation is taught after the practice of giving and morality.

Another related practice to renunciation and sense restraint taught by the Buddha is "restraint in eating" or moderation with food, which for monks generally means not eating after noon. Devout laypersons also follow this rule during special days of religious observance (''uposatha

The Uposatha ( sa, Upavasatha) is a Buddhist day of observance, in existence from the Buddha's time (600 BCE), and still being kept today by Buddhist practitioners. The Buddha taught that the Uposatha day is for "the cleansing of the defiled mind ...

''). Observing the Uposatha also includes other practices dealing with renunciation, mainly the eight precepts.

For Buddhist monastics, renunciation can also be trained through several optional ascetic practices called '' dhutaṅga''.

In different Buddhist traditions, other related practices which focus on fasting are followed.

Mindfulness and clear comprehension

The training of the faculty called "mindfulness" (Pali: ''sati'', Sanskrit: ''smṛti,'' literally meaning "recollection, remembering") is central in Buddhism. According to Analayo, mindfulness is a full awareness of the present moment which enhances and strengthens memory. The Indian Buddhist philosopher Asanga defined mindfulness thus: "It is non-forgetting by the mind with regard to the object experienced. Its function is non-distraction."[Boin-Webb, Sara. (English trans. from Walpola Rāhula's French trans. of the Sanskrit; 2001) ''"Abhidharmasamuccaya: The Compendium of the Higher Teaching (Philosophy) by Asaṅga"'', p. 9, Asian Humanities Press.] According to Rupert Gethin, ''sati'' is also "an awareness of things in relation to things, and hence an awareness of their relative value."

There are different practices and exercises for training mindfulness in the early discourses, such as the four '' Satipaṭṭhānas'' (Sanskrit: ''smṛtyupasthāna'', "establishments of mindfulness") and ''Ānāpānasati

Ānāpānasati (Pali; Sanskrit ''ānāpānasmṛti''), meaning " mindfulness of breathing" ("sati" means mindfulness; "ānāpāna" refers to inhalation and exhalation), paying attention to the breath. It is the quintessential form of Buddhist ...

'' (Sanskrit: ''ānāpānasmṛti'', "mindfulness of breathing"'').

A closely related mental faculty, which is often mentioned side by side with mindfulness, is ''sampajañña

''Sampajañña'' (Pāli; Skt.: '' saṃprajanya,'' Tib: ''shes bzhin'') is a term of central importance for meditative practice in all Buddhist traditions. It refers to "The mental process by which one continuously monitors one's own body and ...

'' ("clear comprehension"). This faculty is the ability to comprehend what one is doing and is happening in the mind, and whether it is being influenced by unwholesome states or wholesome ones.

Meditation – ''Sama-amādhi'' and ''dhyāna''

A wide range of meditation practices has developed in the Buddhist traditions, but "meditation" primarily refers to the attainment of ''

A wide range of meditation practices has developed in the Buddhist traditions, but "meditation" primarily refers to the attainment of ''samādhi

''Samadhi'' (Pali and sa, समाधि), in Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, Sikhism and yogic schools, is a state of meditative consciousness. In Buddhism, it is the last of the eight elements of the Noble Eightfold Path. In the Ashtanga Yoga ...

'' and the practice of '' dhyāna'' (Pali: ''jhāna''). ''Samādhi'' is a calm, undistracted, unified and concentrated state of awareness. It is defined by Asanga as "one-pointedness of mind on the object to be investigated. Its function consists of giving a basis to knowledge (''jñāna'')."

Origins

The earliest evidence of yogis and their meditative tradition, states Karel Werner, is found in the Keśin

The Keśin were ascetic wanderers with mystical powers described in the Keśin Hymn (RV 10, 136) of the ''Rigveda'' (an ancient Indian sacred collection of Vedic Sanskrit hymns). Werner 1995, p. 34. The Keśin are described as homeless, traveling ...

hymn 10.136 of the Rigveda

The ''Rigveda'' or ''Rig Veda'' ( ', from ' "praise" and ' "knowledge") is an ancient Indian collection of Vedic Sanskrit hymns (''sūktas''). It is one of the four sacred canonical Hindu texts ('' śruti'') known as the Vedas. Only one ...

.meditation

Meditation is a practice in which an individual uses a technique – such as mindfulness, or focusing the mind on a particular object, thought, or activity – to train attention and awareness, and achieve a mentally clear and emotionally calm ...

was practised in the centuries preceding the Buddha, the meditative methodologies described in the Buddhist texts are some of the earliest among texts that have survived into the modern era. These methodologies likely incorporate what existed before the Buddha as well as those first developed within Buddhism.

There is no scholarly agreement on the origin and source of the practice of ''dhyāna.'' Some scholars, like Bronkhorst, see the ''four dhyānas'' as a Buddhist invention. Alexander Wynne argues that the Buddha learned ''dhyāna'' from Brahmanical teachers.

Whatever the case, the Buddha taught meditation with a new focus and interpretation, particularly through the ''four dhyānas'' methodology, in which mindfulness is maintained. Further, the focus of meditation and the underlying theory of liberation guiding the meditation has been different in Buddhism. For example, states Bronkhorst, the verse 4.4.23 of the ''Brihadaranyaka Upanishad'' with its "become calm, subdued, quiet, patiently enduring, concentrated, one sees soul in oneself" is most probably a meditative state. The Buddhist discussion of meditation is without the concept of soul and the discussion criticises both the ascetic meditation of Jainism and the "real self, soul" meditation of Hinduism.

The formless attaiments

Often grouped into the ''jhāna''-scheme are four other meditative states, referred to in the early texts as ''arupa samāpattis'' (formless attainments). These are also referred to in commentarial literature as immaterial/formless ''jhānas'' (''arūpajhānas''). The first formless attainment is a place or realm of infinite space (''ākāsānañcāyatana'') without form or colour or shape. The second is termed the realm of infinite consciousness (''viññāṇañcāyatana''); the third is the realm of nothingness (''ākiñcaññāyatana''), while the fourth is the realm of "neither perception nor non-perception".

Meditation and insight

In the Pali canon, the Buddha outlines two meditative qualities which are mutually supportive: ''

In the Pali canon, the Buddha outlines two meditative qualities which are mutually supportive: ''samatha

''Samatha'' (Pāli; sa, शमथ ''śamatha''; ), "calm," "serenity," "tranquillity of awareness," and ''vipassanā'' (Pāli; Sanskrit ''vipaśyanā''), literally "special, super (''vi-''), seeing (''-passanā'')", are two qualities of the ...

'' (Pāli; Sanskrit: ''śamatha''; "calm") and ''vipassanā

''Samatha'' ( Pāli; sa, शमथ ''śamatha''; ), "calm," "serenity," "tranquillity of awareness," and ''vipassanā'' ( Pāli; Sanskrit ''vipaśyanā''), literally "special, super (''vi-''), seeing (''-passanā'')", are two qualities of t ...

'' (Sanskrit: ''vipaśyanā'', insight). The Buddha compares these mental qualities to a "swift pair of messengers" who together help deliver the message of ''nibbana'' (SN 35.245).

The various Buddhist traditions generally see Buddhist meditation as being divided into those two main types. Samatha is also called "calming meditation", and focuses on stilling and concentrating the mind i.e. developing samadhi and the four ''dhyānas''. According to Damien Keown, ''vipassanā'' meanwhile, focuses on "the generation of penetrating and critical insight (''paññā'')".

There are numerous doctrinal positions and disagreements within the different Buddhist traditions regarding these qualities or forms of meditation. For example, in the Pali ''Four Ways to Arahantship Sutta'' (AN 4.170), it is said that one can develop calm and then insight, or insight and then calm, or both at the same time. Meanwhile, in Vasubandhu's ''Abhidharmakośakārikā'', vipaśyanā is said to be practiced once one has reached samadhi by cultivating the four foundations of mindfulness (''smṛtyupasthāna''s).

Beginning with comments by La Vallee Poussin, a series of scholars have argued that these two meditation types reflect a tension between two different ancient Buddhist traditions regarding the use of ''dhyāna,'' one which focused on insight based practice and the other which focused purely on ''dhyāna''.[Anālayo]

"A Brief Criticism of the 'Two Paths to Liberation' Theory"

JOCBS. 2016 (11): 38-51. However, other scholars such as Analayo and Rupert Gethin have disagreed with this "two paths" thesis, instead seeing both of these practices as complementary.

The ''Brahma-vihara''

The four immeasurables or four abodes, also called ''Brahma-viharas'', are virtues or directions for meditation in Buddhist traditions, which helps a person be reborn in the heavenly (Brahma) realm. These are traditionally believed to be a characteristic of the deity Brahma and the heavenly abode he resides in.

The four ''Brahma-vihara'' are:

# Loving-kindness (Pāli: '' mettā'', Sanskrit: ''maitrī'') is active good will towards all;

# Compassion (Pāli and Sanskrit: ''

The four immeasurables or four abodes, also called ''Brahma-viharas'', are virtues or directions for meditation in Buddhist traditions, which helps a person be reborn in the heavenly (Brahma) realm. These are traditionally believed to be a characteristic of the deity Brahma and the heavenly abode he resides in.

The four ''Brahma-vihara'' are:

# Loving-kindness (Pāli: '' mettā'', Sanskrit: ''maitrī'') is active good will towards all;

# Compassion (Pāli and Sanskrit: ''karuṇā

' () is generally translated as compassion or mercy and sometimes as self-compassion or spiritual longing. It is a significant spiritual concept in the Indic religions of Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, and Jainism.

Buddhism

is important in ...

'') results from ''metta''; it is identifying the suffering of others as one's own;

# Empathetic joy (Pāli and Sanskrit: ''muditā

''Muditā'' (Pāli and Sanskrit: मुदिता) means joy; especially sympathetic or vicarious joy, or the pleasure that comes from delighting in other people's well-being.

The traditional paradigmatic example of this mind-state is the att ...

''): is the feeling of joy because others are happy, even if one did not contribute to it; it is a form of sympathetic joy;

# Equanimity (Pāli: '' upekkhā'', Sanskrit: ''upekṣā''): is even-mindedness and serenity, treating everyone impartially.

Tantra, visualization and the subtle body

Some Buddhist traditions, especially those associated with Tantric Buddhism (also known as Vajrayana and Secret Mantra) use images and symbols of deities and Buddhas in meditation. This is generally done by mentally visualizing a Buddha image (or some other mental image, like a symbol, a mandala, a syllable, etc.), and using that image to cultivate calm and insight. One may also visualize and identify oneself with the imagined deity. While visualization practices have been particularly popular in Vajrayana, they may also found in Mahayana and Theravada traditions.

In Tibetan Buddhism, unique tantric techniques which include visualization (but also

Some Buddhist traditions, especially those associated with Tantric Buddhism (also known as Vajrayana and Secret Mantra) use images and symbols of deities and Buddhas in meditation. This is generally done by mentally visualizing a Buddha image (or some other mental image, like a symbol, a mandala, a syllable, etc.), and using that image to cultivate calm and insight. One may also visualize and identify oneself with the imagined deity. While visualization practices have been particularly popular in Vajrayana, they may also found in Mahayana and Theravada traditions.

In Tibetan Buddhism, unique tantric techniques which include visualization (but also mantra

A mantra ( Pali: ''manta'') or mantram (मन्त्रम्) is a sacred utterance, a numinous sound, a syllable, word or phonemes, or group of words in Sanskrit, Pali and other languages believed by practitioners to have religious, ...

recitation, mandala

A mandala ( sa, मण्डल, maṇḍala, circle, ) is a geometric configuration of symbols. In various spiritual traditions, mandalas may be employed for focusing attention of practitioners and adepts, as a spiritual guidance tool, for e ...

s, and other elements) are considered to be much more effective than non-tantric meditations and they are one of the most popular meditation methods. The methods of '' Unsurpassable Yoga Tantra'', (''anuttarayogatantra'') are in turn seen as the highest and most advanced. Anuttarayoga practice is divided into two stages, the ''Generation Stage'' and the ''Completion Stage.'' In the Generation Stage, one meditates on emptiness and visualizes oneself as a deity as well as visualizing its mandala. The focus is on developing clear appearance and divine pride (the understanding that oneself and the deity are one). This method is also known as deity yoga (''devata yoga''). There are numerous meditation deities (''yidam

''Yidam'' is a type of deity associated with tantric or Vajrayana Buddhism said to be manifestations of Buddhahood or enlightened mind. During personal meditation (''sādhana'') practice, the yogi identifies their own form, attributes and mi ...

'') used, each with a mandala, a circular symbolic map used in meditation.

Insight and knowledge

''Prajñā'' (Sanskrit) or ''paññā'' (Pāli) is wisdom

Wisdom, sapience, or sagacity is the ability to contemplate and act using knowledge, experience, understanding, common sense and insight. Wisdom is associated with attributes such as unbiased judgment, compassion, experiential self-knowle ...