''Mahāyāna'' (; "Great Vehicle") is a term for a broad group of

Buddhist

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

traditions,

texts,

philosophies

Philosophical schools of thought and philosophical movements.

A

Absurdism -

Action, philosophy of -

Actual idealism -

Actualism -

Advaita Vedanta -

Aesthetic Realism -

Aesthetics -

African philosophy -

Afrocentrism -

Agential realism - ...

, and practices. Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

(c. 1st century BCE onwards) and is considered one of the three main existing branches of Buddhism (the other being

''Theravāda'' and

Vajrayana

Vajrayāna ( sa, वज्रयान, "thunderbolt vehicle", "diamond vehicle", or "indestructible vehicle"), along with Mantrayāna, Guhyamantrayāna, Tantrayāna, Secret Mantra, Tantric Buddhism, and Esoteric Buddhism, are names referring t ...

).

[Harvey (2013), p. 189.] Mahāyāna accepts the main scriptures and teachings of

early Buddhism The term Early Buddhism can refer to at least two distinct periods in the History of Buddhism, mostly in the History of Buddhism in India:

* Pre-sectarian Buddhism, which refers to the teachings and monastic organization and structure, founded by G ...

but also recognizes various doctrines and texts that are not accepted by Theravada Buddhism as original. These include the

Mahāyāna Sūtras and their emphasis on the ''bodhisattva'' path and

''Prajñāpāramitā''. ''

Vajrayāna

Vajrayāna ( sa, वज्रयान, "thunderbolt vehicle", "diamond vehicle", or "indestructible vehicle"), along with Mantrayāna, Guhyamantrayāna, Tantrayāna, Secret Mantra, Tantric Buddhism, and Esoteric Buddhism, are names referring t ...

'' or Mantra traditions are a subset of Mahāyāna, which make use of numerous

tantric methods considered to be faster and more powerful at achieving

Buddhahood

In Buddhism, Buddha (; Pali, Sanskrit: 𑀩𑀼𑀤𑁆𑀥, बुद्ध), "awakened one", is a title for those who are awake, and have attained nirvana and Buddhahood through their own efforts and insight, without a teacher to point out ...

by Vajrayānists.

"Mahāyāna" also refers to the path of the

bodhisattva

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva ( ; sa, 𑀩𑁄𑀥𑀺𑀲𑀢𑁆𑀢𑁆𑀯 (Brahmī), translit=bodhisattva, label=Sanskrit) or bodhisatva is a person who is on the path towards bodhi ('awakening') or Buddhahood.

In the Early Buddhist schools ...

striving to become a fully awakened Buddha (''

samyaksaṃbuddha

In Buddhism, Buddha (; Pali, Sanskrit: 𑀩𑀼𑀤𑁆𑀥, बुद्ध), "awakened one", is a title for those who are awake, and have attained nirvana and Buddhahood through their own efforts and insight, without a teacher to point ou ...

'') for the benefit of all sentient beings, and is thus also called the "Bodhisattva Vehicle" (''Bodhisattvayāna'').

[ Damien Keown (2003), ]

A Dictionary of Buddhism

', Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the university press of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world, and its printing history dates back to the 1480s. Having been officially granted the legal right to print books ...

, p. 38 Mahāyāna Buddhism generally sees the goal of becoming a Buddha through the bodhisattva path as being available to all and sees the state of the

arhat

In Buddhism, an ''arhat'' (Sanskrit: अर्हत्) or ''arahant'' (Pali: अरहन्त्, 𑀅𑀭𑀳𑀦𑁆𑀢𑁆) is one who has gained insight into the true nature of existence and has achieved ''Nirvana'' and liberated ...

as incomplete. Mahāyāna also includes numerous Buddhas and bodhisattvas that are not found in Theravada (such as ''

Amitābha

Amitābha ( sa, अमिताभ, IPA: ), also known as Amitāyus, is the primary Buddha of Pure Land Buddhism. In Vajrayana Buddhism, he is known for his longevity, discernment, pure perception, purification of aggregates, and deep awarene ...

'' and

Vairocana

Vairocana (also Mahāvairocana, sa, वैरोचन) is a cosmic buddha from Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism. Vairocana is often interpreted, in texts like the ''Avatamsaka Sutra'', as the dharmakāya of the historical Gautama Buddha. In East ...

).

Mahāyāna Buddhist philosophy also promotes unique theories, such as the

Madhyamaka

Mādhyamaka ("middle way" or "centrism"; ; Tibetan: དབུ་མ་པ ; ''dbu ma pa''), otherwise known as Śūnyavāda ("the emptiness doctrine") and Niḥsvabhāvavāda ("the no ''svabhāva'' doctrine"), refers to a tradition of Buddhist ...

theory of emptiness (''

śūnyatā

''Śūnyatā'' ( sa, शून्यता, śūnyatā; pi, suññatā; ), translated most often as ''emptiness'', ''vacuity'', and sometimes ''voidness'', is an Indian philosophical concept. Within Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism and other p ...

''), the ''

Vijñānavāda'' doctrine, and the ''

Buddha-nature

Buddha-nature refers to several related Mahayana Buddhist terms, including '' tathata'' ("suchness") but most notably ''tathāgatagarbha'' and ''buddhadhātu''. ''Tathāgatagarbha'' means "the womb" or "embryo" (''garbha'') of the "thus-gone ...

'' teaching.

Although it was initially a small movement in India, Mahāyāna eventually grew to become an influential force in

Indian Buddhism

Buddhism is an ancient Indian religion, which arose in and around the ancient Kingdom of Magadha (now in Bihar, India), and is based on the teachings of Gautama Buddha who was deemed a "Buddha" ("Awakened One"), although Buddhist doctri ...

.

Large scholastic centers associated with Mahāyāna such as

Nalanda

Nalanda (, ) was a renowned ''mahavihara'' (Buddhist monastic university) in ancient Magadha (modern-day Bihar), India.[Vikramashila

Vikramashila (Sanskrit: विक्रमशिला, IAST: , Bengali:- বিক্রমশিলা, Romanisation:- Bikrômôśilā ) was one of the three most important Buddhist monasteries in India during the Pala Empire, along with N ...]

, thrived between the seventh and twelfth centuries.

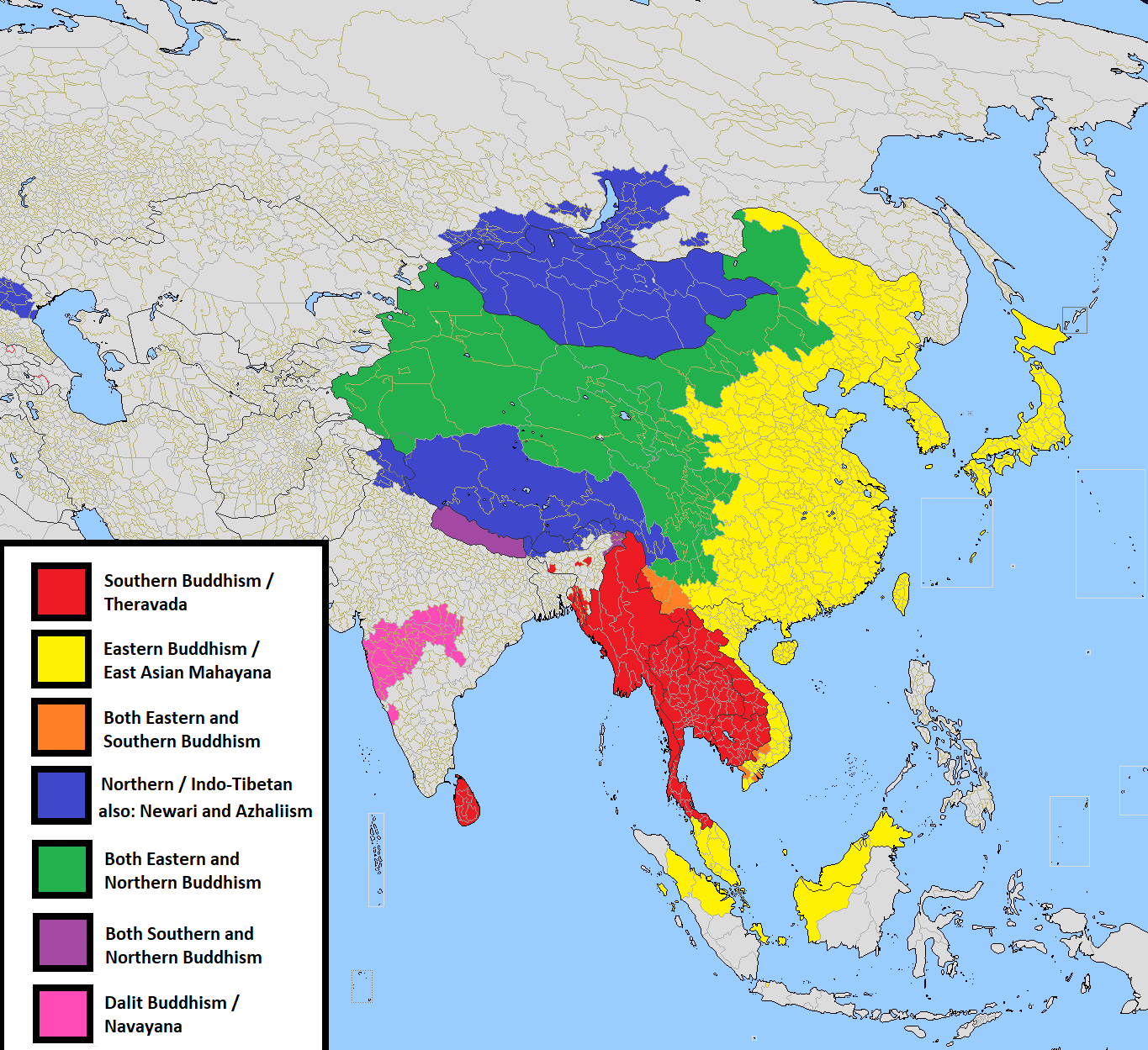

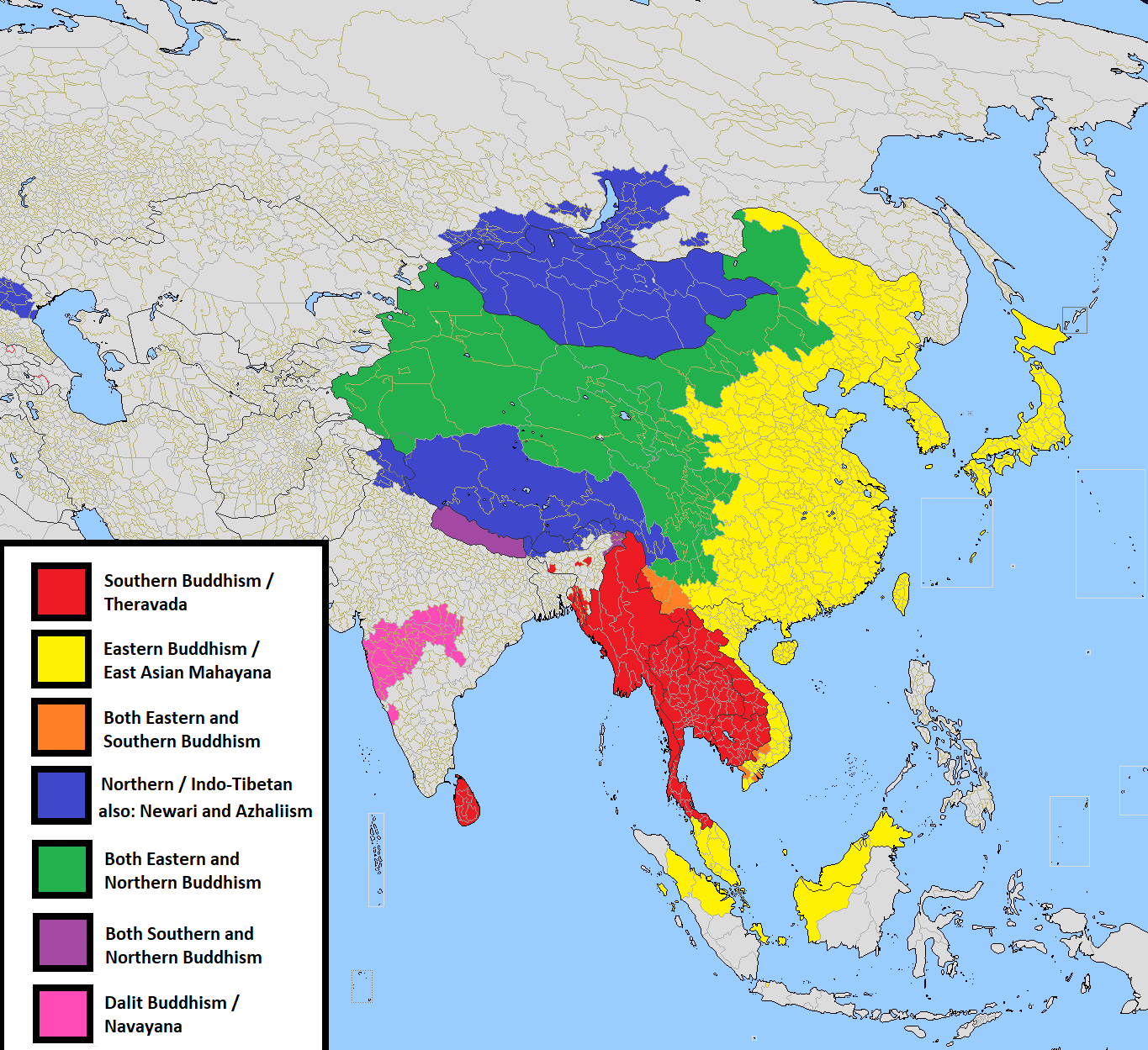

In the course of its history, Mahāyāna Buddhism spread throughout

South Asia

South Asia is the southern subregion of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The region consists of the countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.;;;;;;;; ...

,

Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t ...

,

East Asia

East Asia is the eastern region of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The modern states of East Asia include China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. China, North Korea, South Korea and ...

, and

Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, south-eastern region of Asia, consistin ...

. It remains influential today in

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

,

Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers an area of , with a population of just 3.3 million, ...

,

Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China ( abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delt ...

,

Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

,

Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

,

Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, borde ...

,

Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

, the

Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

,

Nepal

Nepal (; ne, नेपाल ), formerly the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal ( ne,

सङ्घीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल ), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is mai ...

,

Malaysia

Malaysia ( ; ) is a country in Southeast Asia. The federation, federal constitutional monarchy consists of States and federal territories of Malaysia, thirteen states and three federal territories, separated by the South China Sea into two r ...

,

Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the nort ...

, and

Bhutan

Bhutan (; dz, འབྲུག་ཡུལ་, Druk Yul ), officially the Kingdom of Bhutan,), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is situated in the Eastern Himalayas, between China in the north and India in the south. A mountainous ...

.

The Mahāyāna tradition is the largest major tradition of Buddhism existing today (with 53% of Buddhists belonging to

East Asian Mahāyāna and 6% to Vajrayāna), compared to 36% for Theravada (survey from 2010).

Etymology

Original Sanskrit

According to

Jan Nattier

Jan Nattier is an American scholar of Mahāyana Buddhism.

Early life and education

She earned her PhD in Inner Asian and Altaic Studies from Harvard University (1988), and subsequently taught at the University of Hawaii (1988-1990), Stanford Unive ...

, the term ''Mahāyāna'' ("Great Vehicle") was originally an honorary synonym for ''Bodhisattvayāna'' ("

Bodhisattva

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva ( ; sa, 𑀩𑁄𑀥𑀺𑀲𑀢𑁆𑀢𑁆𑀯 (Brahmī), translit=bodhisattva, label=Sanskrit) or bodhisatva is a person who is on the path towards bodhi ('awakening') or Buddhahood.

In the Early Buddhist schools ...

Vehicle"),

[Nattier, Jan (2003), ''A few good men: the Bodhisattva path according to the Inquiry of Ugra'': p. 174] the vehicle of a bodhisattva seeking

buddhahood

In Buddhism, Buddha (; Pali, Sanskrit: 𑀩𑀼𑀤𑁆𑀥, बुद्ध), "awakened one", is a title for those who are awake, and have attained nirvana and Buddhahood through their own efforts and insight, without a teacher to point out ...

for the benefit of all sentient beings.

The term ''Mahāyāna'' (which had earlier been used simply as an epithet for Buddhism itself) was therefore adopted at an early date as a synonym for the path and the teachings of the bodhisattvas. Since it was simply an honorary term for ''Bodhisattvayāna'', the adoption of the term ''Mahāyāna'' and its application to Bodhisattvayāna did not represent a significant turning point in the development of a Mahāyāna tradition.

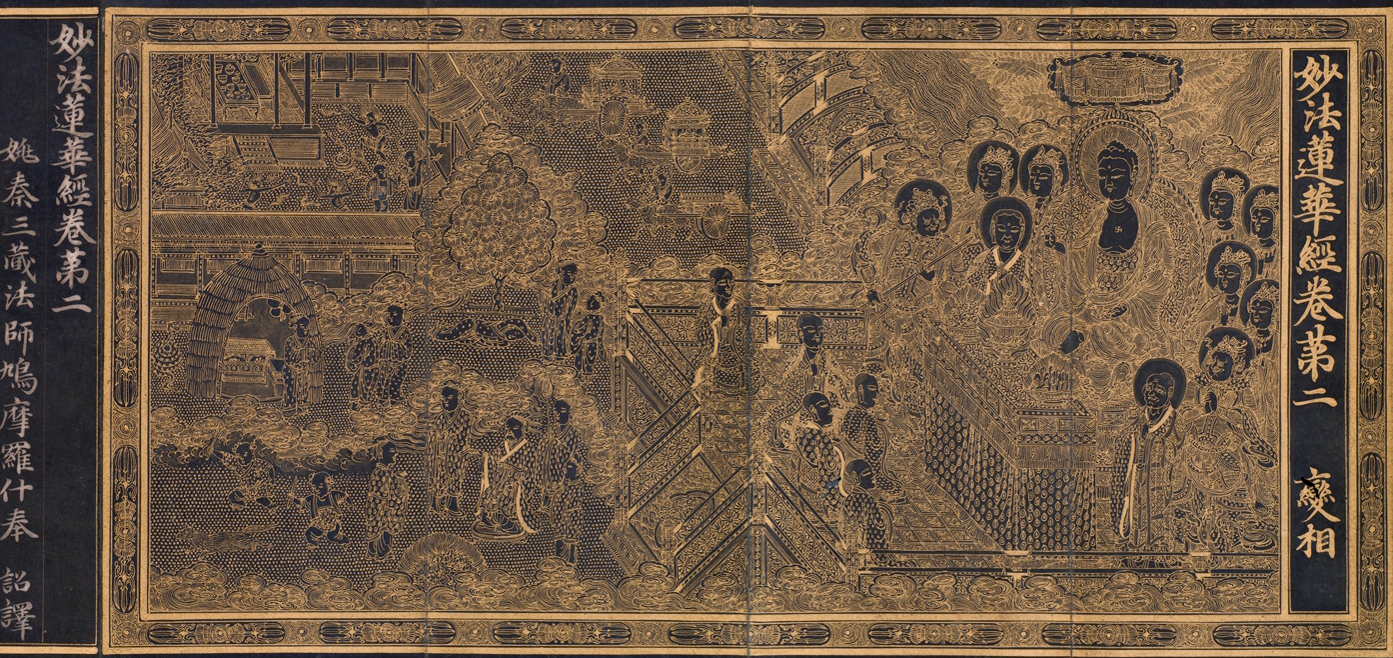

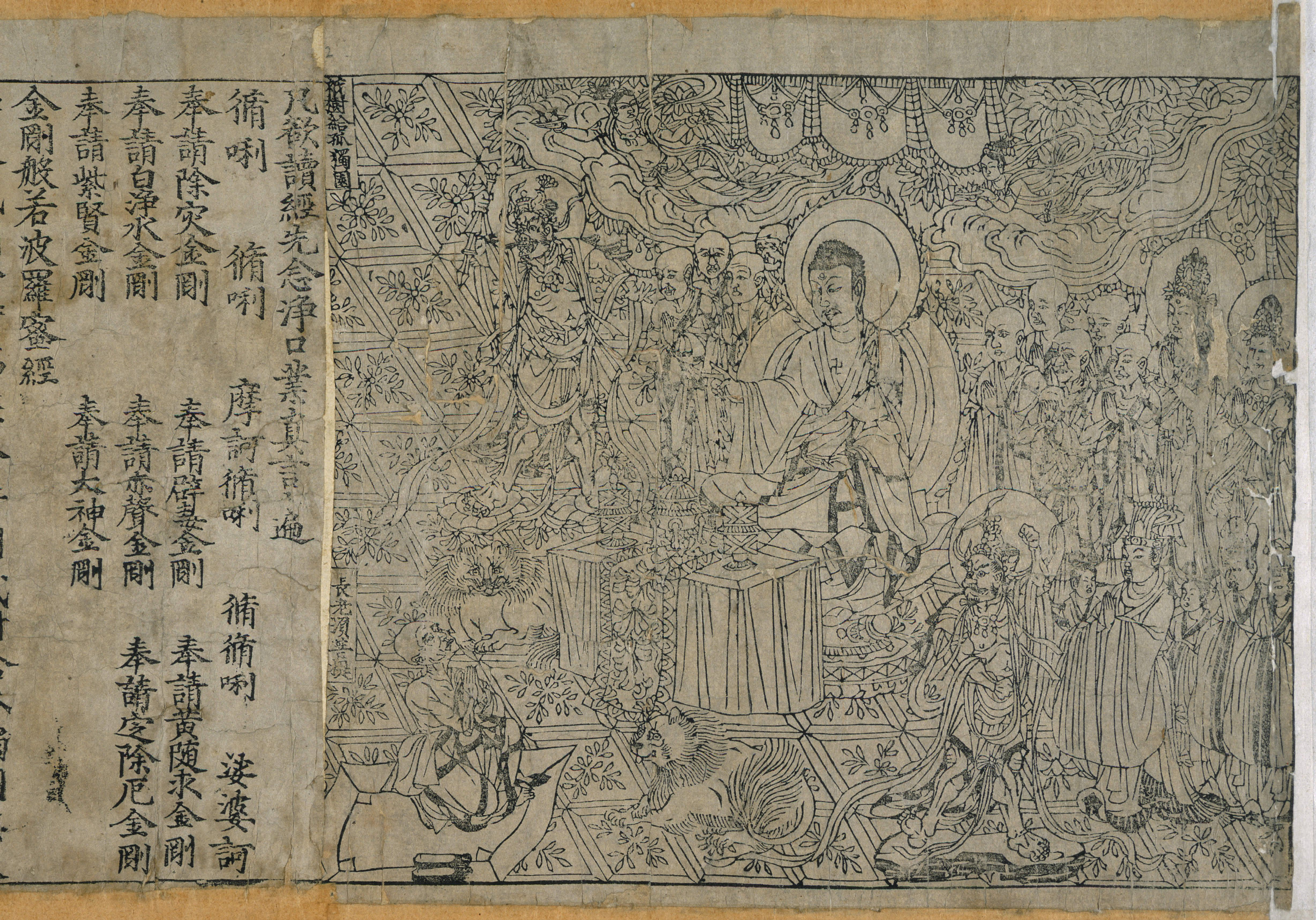

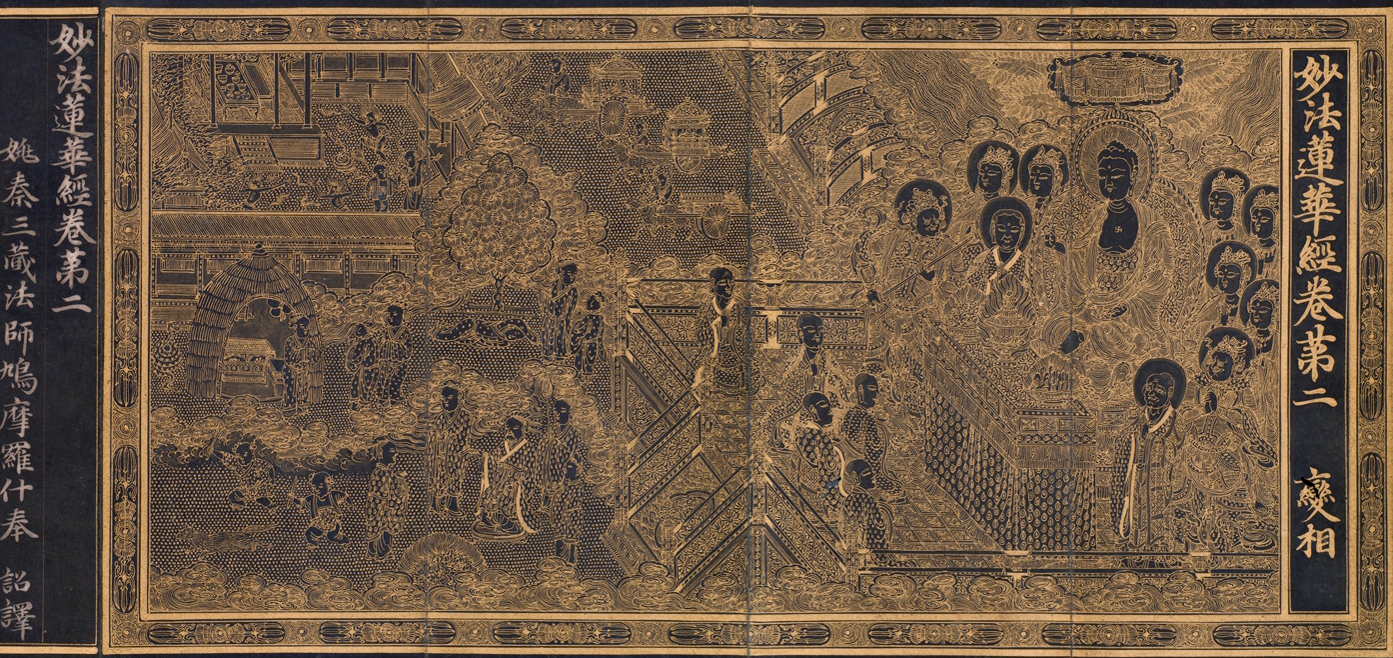

The earliest Mahāyāna texts, such as the ''

Lotus Sūtra

The ''Lotus Sūtra'' ( zh, 妙法蓮華經; sa, सद्धर्मपुण्डरीकसूत्रम्, translit=Saddharma Puṇḍarīka Sūtram, lit=Sūtra on the White Lotus of the True Dharma, italic=) is one of the most influ ...

'', often use the term ''Mahāyāna'' as a synonym for ''Bodhisattvayāna'', but the term ''

Hīnayāna'' is comparatively rare in the earliest sources. The presumed dichotomy between ''Mahāyāna'' and ''Hīnayāna'' can be deceptive, as the two terms were not actually formed in relation to one another in the same era.

Among the earliest and most important references to ''Mahāyāna'' are those that occur in the ''

Lotus Sūtra

The ''Lotus Sūtra'' ( zh, 妙法蓮華經; sa, सद्धर्मपुण्डरीकसूत्रम्, translit=Saddharma Puṇḍarīka Sūtram, lit=Sūtra on the White Lotus of the True Dharma, italic=) is one of the most influ ...

'' (Skt. ''Saddharma Puṇḍarīka Sūtra'') dating between the 1st century BCE and the 1st century CE. Seishi Karashima has suggested that the term first used in an earlier

Gandhāri Prakrit

The Prakrits (; sa, prākṛta; psu, 𑀧𑀸𑀉𑀤, ; pka, ) are a group of vernacular Middle Indo-Aryan languages that were used in the Indian subcontinent from around the 3rd century BCE to the 8th century CE. The term Prakrit is usu ...

version of the ''Lotus Sūtra'' was not the term ''mahāyāna'' but the Prakrit word ''mahājāna'' in the sense of ''mahājñāna'' (great knowing).

[Williams, Paul. ''Buddhism. Vol. 3. The origins and nature of Mahāyāna Buddhism.'' Routledge. 2004. p. 50.] At a later stage when the early Prakrit word was converted into Sanskrit, this ''mahājāna'', being phonetically ambivalent, may have been converted into ''mahāyāna'', possibly because of what may have been a double meaning in the famous

Parable of the Burning House, which talks of three vehicles or carts (Skt: ''yāna'').

[

]

Chinese translation

In Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of ...

, Mahāyāna is called (''dacheng''), which is a calque

In linguistics, a calque () or loan translation is a word or phrase borrowed from another language by literal word-for-word or root-for-root translation. When used as a verb, "to calque" means to borrow a word or phrase from another language wh ...

of ''maha'' (great ) ''yana'' (vehicle ). There is also the transliteration . The term appeared in some of the earliest Mahāyāna texts, including Emperor Ling of Han

Emperor Ling of Han (156 – 13 May 189), personal name Liu Hong, was the 12th and last powerful emperor of the Eastern Han dynasty. Born the son of a lesser marquis who descended directly from Emperor Zhang (the third Eastern Han emperor), L ...

's translation of the Lotus Sutra.[Nattier, Jan (2003), ''A few good men: the Bodhisattva path according to the Inquiry of Ugra'': pp. 193–194] It also appears in the Chinese Āgamas, though scholars like Yin Shun argue that this is a later addition. Some Chinese scholars also argue that the meaning of the term in these earlier texts is different than later ideas of Mahāyāna Buddhism.

History

Origin

The origins of Mahāyāna are still not completely understood and there are numerous competing theories.[Akira, Hirakawa (translated and edited by Paul Groner) (1993. ''A History of Indian Buddhism''. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass: p. 260.] The earliest Western views of Mahāyāna assumed that it existed as a separate school in competition with the so-called " Hīnayāna" schools. Some of the major theories about the origins of Mahāyāna include the following:

The lay origins theory was first proposed by Jean Przyluski

Jean Przyluski (17 August 1885 – 28 October 1944) was a French linguist and scholar of religion and Buddhism of Polish descent. His interests ranged widely through the structure of the Vietnamese language, the development of Buddhist myths ...

and then defended by Étienne Lamotte

Étienne Paul Marie Lamotte (21 November 1903 – 5 May 1983) was a Belgian priest and Professor of Greek at the Catholic University of Louvain, but was better known as an Indologist and the greatest authority on Buddhism in the West in his time. H ...

and Akira Hirakawa. This view states that laypersons were particularly important in the development of Mahāyāna and is partly based on some texts like the ''Vimalakirti Sūtra'', which praise lay figures at the expense of monastics. This theory is no longer widely accepted since numerous early Mahāyāna works promote monasticism and asceticism.Mahāsāṃghika

The Mahāsāṃghika (Brahmi: 𑀫𑀳𑀸𑀲𑀸𑀁𑀖𑀺𑀓, "of the Great Sangha", ) was one of the early Buddhist schools. Interest in the origins of the Mahāsāṃghika school lies in the fact that their Vinaya recension appears in se ...

tradition.[Drewes, David, ''Early Indian Mahayana Buddhism I: Recent Scholarship'', Religion Compass 4/2 (2010): 55–65, ] This is defended by scholars such as Hendrik Kern, A.K. Warder

Anthony Kennedy Warder (8 September 1924 – 8 January 2013) was a British Indologist. His best-known works are ''Introduction to Pali'' (1963), ''Indian Buddhism'' (1970), and the eight-volume ''Indian Kāvya Literature'' (1972–2011).

Life

Wa ...

and Paul Williams who argue that at least some Mahāyāna elements developed among Mahāsāṃghika communities (from the 1st century BCE onwards), possibly in the area along the Kṛṣṇa River in the Āndhra region of southern India.[Guang Xing. ''The Concept of the Buddha: Its Evolution from Early Buddhism to the Trikaya Theory.'' 2004. pp. 65–66 "Several scholars have suggested that the Prajñāpāramitā probably developed among the Mahasamghikas in Southern India, in the Andhra country, on the Krishna River."][Williams, Paul. ''Mahayana Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations 2nd edition.'' Routledge, 2009, p. 47.][Akira, Hirakawa (translated and edited by Paul Groner) (1993. ''A History of Indian Buddhism''. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass: pp. 253, 263, 268]["The south (of India) was then vigorously creative in producing Mahayana Sutras" – Warder, A.K. (3rd edn. 1999). ''Indian Buddhism'': p. 335.] The Mahāsāṃghika doctrine of the supramundane ( ''lokottara'') nature of the Buddha is sometimes seen as a precursor to Mahāyāna views of the Buddha.Nāgārjuna

Nāgārjuna . 150 – c. 250 CE (disputed)was an Indian Mahāyāna Buddhist thinker, scholar-saint and philosopher. He is widely considered one of the most important Buddhist philosophers.Garfield, Jay L. (1995), ''The Fundamental Wisdom of ...

, Dignaga, Candrakīrti

Chandrakirti (; ; , meaning "glory of the moon" in Sanskrit) or "Chandra" was a Buddhist scholar of the madhyamaka school and a noted commentator on the works of Nagarjuna () and those of his main disciple, Aryadeva. He wrote two influential w ...

, Āryadeva

Āryadeva (fl. 3rd century CE) (; , Chinese: ''Tipo pusa'' ��婆 菩薩 = Deva Bodhisattva, was a Mahayana Buddhist monk, a disciple of Nagarjuna and a Madhyamaka philosopher.Silk, Jonathan A. (ed.) (2019). ''Brill’s Encyclopedia of Budd ...

, and Bhavaviveka as having ties to the Mahāsāṃghika tradition of Āndhra. However, other scholars have also pointed to different regions as being important, such as Gandhara

Gandhāra is the name of an ancient region located in the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent, more precisely in present-day north-west Pakistan and parts of south-east Afghanistan. The region centered around the Peshawar Vall ...

and northwest India.[Karashima, 2013.]

The Mahāsāṃghika origins theory has also slowly been shown to be problematic by scholarship that revealed how certain Mahāyāna sutras show traces of having developed among other '' nikāyas'' or monastic orders (such as the Dharmaguptaka). Because of such evidence, scholars like Paul Harrison and Paul Williams argue that the movement was not sectarian and was possibly pan-buddhist.Jan Nattier

Jan Nattier is an American scholar of Mahāyana Buddhism.

Early life and education

She earned her PhD in Inner Asian and Altaic Studies from Harvard University (1988), and subsequently taught at the University of Hawaii (1988-1990), Stanford Unive ...

and Reginald Ray

Reginald Ray (born 1942) is an American Buddhist academic and teacher.

Ray studied Tibetan Buddhism, traditional shamanic wisdom, and yogic-contemplative practices with the Tibetan refugee and recognized Vajrayana traditional-wisdom holder Chög ...

. This theory is based on certain sutras like the ''Ugraparipṛcchā Sūtra

The ''Ugraparipṛcchā Sūtra'' (''The inquiry of Ugra'') is an early Indian sutra which is particularly important for understanding the beginnings of Mahayana Buddhism. It contains positive references to both the path of the bodhisattva and the p ...

'' and the ''Mahāyāna Rāṣṭrapālapaṛiprcchā'' which promote ascetic practice in the wilderness as a superior and elite path. These texts criticize monks who live in cities and denigrate the forest life.

Jan Nattier's study of the ''Ugraparipṛcchā Sūtra, A few good men'' (2003) argues that this sutra represents the earliest form of Mahāyāna, which presents the bodhisattva

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva ( ; sa, 𑀩𑁄𑀥𑀺𑀲𑀢𑁆𑀢𑁆𑀯 (Brahmī), translit=bodhisattva, label=Sanskrit) or bodhisatva is a person who is on the path towards bodhi ('awakening') or Buddhahood.

In the Early Buddhist schools ...

path as a 'supremely difficult enterprise' of elite monastic forest asceticism.Gregory Schopen

Gregory Schopen is Professor of Buddhist Studies at University of California, Los Angeles. He received his B.A. majoring in American literature from Black Hills State College, M.A. in history of religions from McMaster University in Ontario, Cana ...

, states that Mahāyāna arose among a number of loosely connected book worshiping groups of monastics, who studied, memorized, copied and revered particular Mahāyāna sūtras. Schopen thinks they were inspired by cult shrines where Mahāyāna sutras were kept.stupa

A stupa ( sa, स्तूप, lit=heap, ) is a mound-like or hemispherical structure containing relics (such as ''śarīra'' – typically the remains of Buddhist monks or nuns) that is used as a place of meditation.

In Buddhism, circumamb ...

worship, or worshiping holy relics.

David Drewes has recently argued against all of the major theories outlined above. He points out that there is no actual evidence for the existence of book shrines, that the practice of sutra veneration was pan-Buddhist and not distinctly Mahāyāna. Furthermore, Drewes argues that "Mahāyāna sutras advocate mnemic/oral/aural practices more frequently than they do written ones."pure lands

A pure land is the celestial realm of a buddha or bodhisattva in Mahayana Buddhism. The term "pure land" is particular to East Asian Buddhism () and related traditions; in Sanskrit the equivalent concept is called a buddha-field (Sanskrit ). T ...

' where one will be able to make easy and rapid progress on the bodhisattva path and attain Buddhahood after as little as one lifetime."[Drewes, David, Early Indian Mahayana Buddhism II: New Perspectives, ''Religion Compass'' 4/2 (2010): 66–74, ] Drewes points out the importance of ''dharmabhanakas'' (preachers, reciters of these sutras) in the early Mahāyāna sutras. This figure is widely praised as someone who should be respected, obeyed ('as a slave serves his lord'), and donated to, and it is thus possible these people were the primary agents of the Mahāyāna movement.

Early Mahāyāna

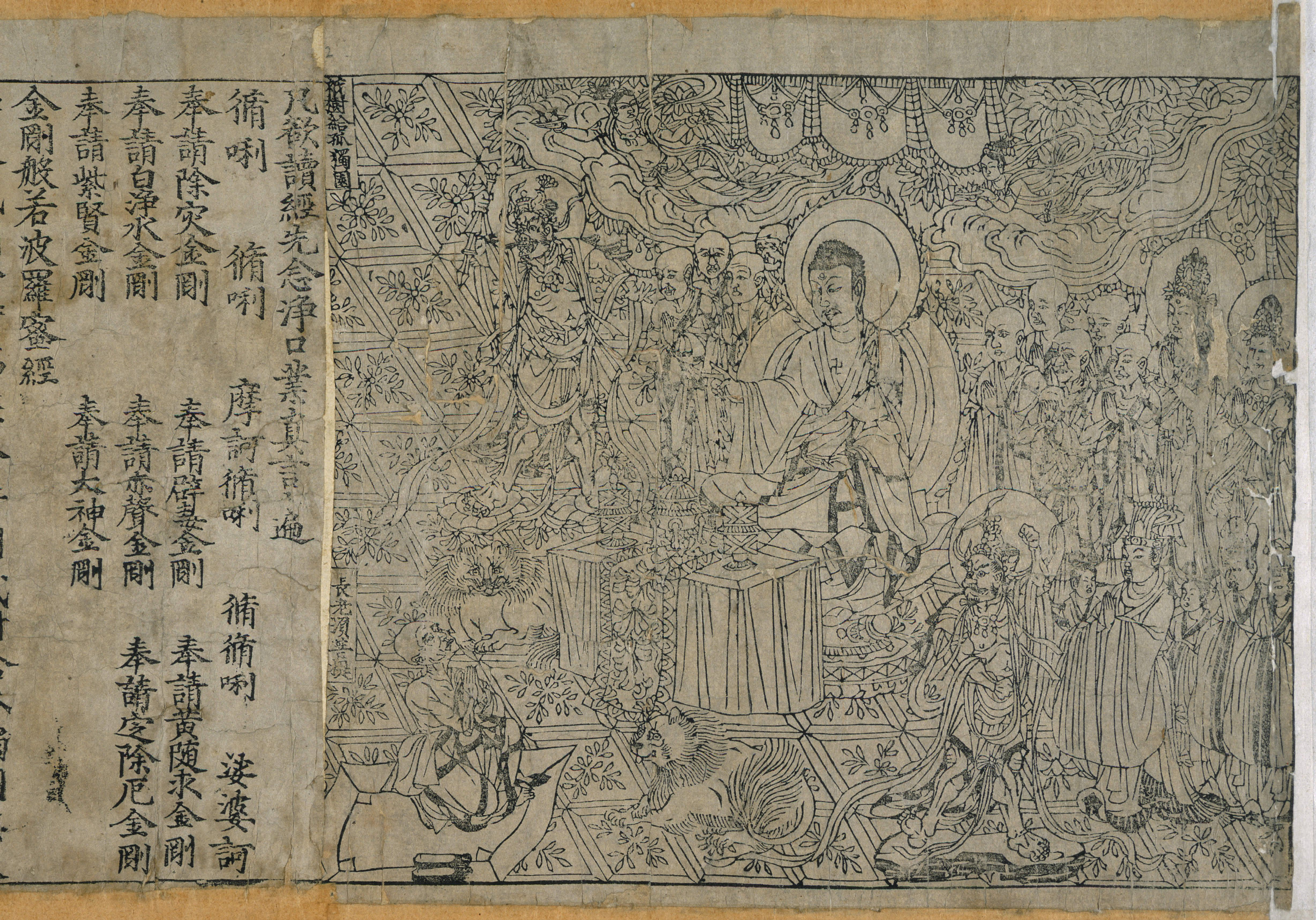

The earliest textual evidence of "Mahāyāna" comes from sūtras

''Sutra'' ( sa, सूत्र, translit=sūtra, translit-std=IAST, translation=string, thread)Monier Williams, ''Sanskrit English Dictionary'', Oxford University Press, Entry fo''sutra'' page 1241 in Indian literary traditions refers to an aph ...

("discourses", scriptures) originating around the beginning of the common era. Jan Nattier has noted that some of the earliest Mahāyāna texts, such as the '' Ugraparipṛccha Sūtra'' use the term "Mahāyāna", yet there is no doctrinal difference between Mahāyāna in this context and the early schools. Instead, Nattier writes that in the earliest sources, "Mahāyāna" referred to the rigorous emulation of Gautama Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha, was a wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism.

According to Buddhist tradition, he was born in Lu ...

's path to Buddhahood.Gandhāra

Gandhāra is the name of an ancient region located in the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent, more precisely in present-day north-west Pakistan and parts of south-east Afghanistan. The region centered around the Peshawar Val ...

. These are some of the earliest known Mahāyāna texts. Study of these texts by Paul Harrison and others show that they strongly promote monasticism

Monasticism (from Ancient Greek , , from , , 'alone'), also referred to as monachism, or monkhood, is a religious way of life in which one renounces worldly pursuits to devote oneself fully to spiritual work. Monastic life plays an important role ...

(contra the lay origin theory), acknowledge the legitimacy of arhat

In Buddhism, an ''arhat'' (Sanskrit: अर्हत्) or ''arahant'' (Pali: अरहन्त्, 𑀅𑀭𑀳𑀦𑁆𑀢𑁆) is one who has gained insight into the true nature of existence and has achieved ''Nirvana'' and liberated ...

ship, do not recommend devotion towards 'celestial' bodhisattva

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva ( ; sa, 𑀩𑁄𑀥𑀺𑀲𑀢𑁆𑀢𑁆𑀯 (Brahmī), translit=bodhisattva, label=Sanskrit) or bodhisatva is a person who is on the path towards bodhi ('awakening') or Buddhahood.

In the Early Buddhist schools ...

s and do not show any attempt to establish a new sect or order.ascetic

Asceticism (; from the el, ἄσκησις, áskesis, exercise', 'training) is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from sensual pleasures, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their p ...

practices, forest dwelling, and deep states of meditative concentration (''samadhi

''Samadhi'' (Pali and sa, समाधि), in Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, Sikhism and yogic schools, is a state of meditative consciousness. In Buddhism, it is the last of the eight elements of the Noble Eightfold Path. In the Ashtanga Yoga ...

'').

Indian Mahāyāna never had nor ever attempted to have a separate Vinaya

The Vinaya (Pali & Sanskrit: विनय) is the division of the Buddhist canon ('' Tripitaka'') containing the rules and procedures that govern the Buddhist Sangha (community of like-minded ''sramanas''). Three parallel Vinaya traditions remai ...

or ordination lineage from the early schools of Buddhism, and therefore each bhikṣu or bhikṣuṇī adhering to the Mahāyāna formally belonged to one of the early Buddhist schools. Membership in these ''nikāyas'', or monastic orders, continues today, with the Dharmaguptaka nikāya being used in East Asia, and the Mūlasarvāstivāda

The Mūlasarvāstivāda (Sanskrit: मूलसर्वास्तिवाद; ) was one of the early Buddhist schools of India. The origins of the Mūlasarvāstivāda and their relationship to the Sarvāstivāda sect still remain largely unk ...

nikāya being used in Tibetan Buddhism

Tibetan Buddhism (also referred to as Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, Lamaism, Lamaistic Buddhism, Himalayan Buddhism, and Northern Buddhism) is the form of Buddhism practiced in Tibet and Bhutan, where it is the dominant religion. It is also in majo ...

. Therefore, Mahāyāna was never a separate monastic sect outside of the early schools.

Paul Harrison clarifies that while monastic Mahāyānists belonged to a nikāya, not all members of a nikāya were Mahāyānists. From Chinese monks visiting India, we now know that both Mahāyāna and non-Mahāyāna monks in India often lived in the same monasteries side by side. It is also possible that, formally, Mahāyāna would have been understood as a group of monks or nuns within a larger monastery taking a vow together (known as a "''kriyākarma''") to memorize and study a Mahāyāna text or texts.

The earliest stone inscription containing a recognizably Mahāyāna formulation and a mention of the Buddha Amitābha

Amitābha ( sa, अमिताभ, IPA: ), also known as Amitāyus, is the primary Buddha of Pure Land Buddhism. In Vajrayana Buddhism, he is known for his longevity, discernment, pure perception, purification of aggregates, and deep awarene ...

(an important Mahāyāna figure) was found in the Indian subcontinent in Mathura

Mathura () is a city and the administrative headquarters of Mathura district in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. It is located approximately north of Agra, and south-east of Delhi; about from the town of Vrindavan, and from Govardhan. ...

, and dated to around 180 CE. Remains of a statue of a Buddha bear the Brāhmī

Brahmi (; ; ISO 15919, ISO: ''Brāhmī'') is a writing system of ancient South Asia. "Until the late nineteenth century, the script of the Aśokan (non-Kharosthi) inscriptions and its immediate derivatives was referred to by various names such ...

inscription: "Made in the year 28 of the reign of King Huviṣka, ... for the Blessed One, the Buddha Amitābha."Schøyen Collection

__NOTOC__

The Schøyen Collection is one of the largest private manuscript collections in the world, mostly located in Oslo and London. Formed in the 20th century by Martin Schøyen, it comprises manuscripts of global provenance, spanning 5,000 y ...

describes Huviṣka as having "set forth in the Mahāyāna." Evidence of the name "Mahāyāna" in Indian inscriptions in the period before the 5th century is very limited in comparison to the multiplicity of Mahāyāna writings transmitted from Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t ...

to China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

at that time.

Based on archeological

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscape ...

evidence, Gregory Schopen argues that Indian Mahāyāna remained "an extremely limited minority movement – if it remained at all – that attracted absolutely no documented public or popular support for at least two more centuries."[Walser, Joseph, ''Nagarjuna in Context: Mahayana Buddhism and Early Indian Culture,'' Columbia University Press, 2005, p. 18.] Their "embattled mentality" may have led to certain elements found in Mahāyāna texts like Lotus sutra

The ''Lotus Sūtra'' ( zh, 妙法蓮華經; sa, सद्धर्मपुण्डरीकसूत्रम्, translit=Saddharma Puṇḍarīka Sūtram, lit=Sūtra on the White Lotus of the True Dharma, italic=) is one of the most influ ...

, such as a concern with preserving texts.Thus we find one scripture (the ''Aksobhya

Akshobhya ( sa, अक्षोभ्य, ''Akṣobhya'', "Immovable One"; ) is one of the Five Wisdom Buddhas, a product of the Adibuddha, who represents consciousness as an aspect of reality. By convention he is located in the east of the ...

-vyuha'') that advocates both srávaka and bodhisattva

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva ( ; sa, 𑀩𑁄𑀥𑀺𑀲𑀢𑁆𑀢𑁆𑀯 (Brahmī), translit=bodhisattva, label=Sanskrit) or bodhisatva is a person who is on the path towards bodhi ('awakening') or Buddhahood.

In the Early Buddhist schools ...

practices, propounds the possibility of rebirth in a pure land, and enthusiastically recommends the cult of the book, yet seems to know nothing of emptiness theory, the ten bhumis, or the trikaya

The Trikāya doctrine ( sa, त्रिकाय, lit. "three bodies"; , ) is a Mahayana Buddhist teaching on both the nature of reality and the nature of Buddhahood. The doctrine says that Buddha has three ''kāyas'' or ''bodies'', the '' Dharm ...

, while another (the ''P’u-sa pen-yeh ching'') propounds the ten bhumis and focuses exclusively on the path of the bodhisattva, but never discusses the paramitas. A Madhyamika

Mādhyamaka ("middle way" or "centrism"; ; Tibetan: དབུ་མ་པ ; ''dbu ma pa''), otherwise known as Śūnyavāda ("the emptiness doctrine") and Niḥsvabhāvavāda ("the no ''svabhāva'' doctrine"), refers to a tradition of Buddhist ...

treatise ( Nagarjuna's '' Mulamadhyamika-karikas'') may enthusiastically deploy the rhetoric of emptiness

Emptiness as a human condition is a sense of generalized boredom, social alienation and apathy. Feelings of emptiness often accompany dysthymia, depression, loneliness, anhedonia,

despair, or other mental/emotional disorders, including schizoid ...

without ever mentioning the bodhisattva path, while a Yogacara

Yogachara ( sa, योगाचार, IAST: '; literally "yoga practice"; "one whose practice is yoga") is an influential tradition of Buddhist philosophy and psychology emphasizing the study of cognition, perception, and consciousness through t ...

treatise ( Vasubandhu's '' Madhyanta-vibhaga-bhasya'') may delve into the particulars of the trikaya doctrine while eschewing the doctrine of ekayana. We must be prepared, in other words, to encounter a multiplicity of Mahayanas flourishing even in India, not to mention those that developed in East Asia and Tibet.

In spite of being a minority in India, Indian Mahāyāna was an intellectually vibrant movement, which developed various schools of thought during what Jan Westerhoff has been called "The Golden Age of Indian Buddhist Philosophy" (from the beginning of the first millennium CE up to the 7th century). Some major Mahāyāna traditions are Prajñāpāramitā, Mādhyamaka

Mādhyamaka ("middle way" or "centrism"; ; Tibetan: དབུ་མ་པ ; ''dbu ma pa''), otherwise known as Śūnyavāda ("the emptiness doctrine") and Niḥsvabhāvavāda ("the no ''svabhāva'' doctrine"), refers to a tradition of Buddhist ...

, Yogācāra

Yogachara ( sa, योगाचार, IAST: '; literally "yoga practice"; "one whose practice is yoga") is an influential tradition of Buddhist philosophy and psychology emphasizing the study of cognition, perception, and consciousness through t ...

, Buddha-nature

Buddha-nature refers to several related Mahayana Buddhist terms, including '' tathata'' ("suchness") but most notably ''tathāgatagarbha'' and ''buddhadhātu''. ''Tathāgatagarbha'' means "the womb" or "embryo" (''garbha'') of the "thus-gone ...

(''Tathāgatagarbha''), and the school of Dignaga and Dharmakirti as the last and most recent. Major early figures include Nagarjuna

Nāgārjuna . 150 – c. 250 CE (disputed)was an Indian Mahāyāna Buddhist thinker, scholar-saint and philosopher. He is widely considered one of the most important Buddhist philosophers.Garfield, Jay L. (1995), ''The Fundamental Wisdom of ...

, Āryadeva

Āryadeva (fl. 3rd century CE) (; , Chinese: ''Tipo pusa'' ��婆 菩薩 = Deva Bodhisattva, was a Mahayana Buddhist monk, a disciple of Nagarjuna and a Madhyamaka philosopher.Silk, Jonathan A. (ed.) (2019). ''Brill’s Encyclopedia of Budd ...

, Aśvaghoṣa

, also transliterated Ashvaghosha, (, अश्वघोष; lit. "Having a Horse-Voice"; ; Chinese 馬鳴菩薩 pinyin: Mǎmíng púsà, litt.: 'Bodhisattva with a Horse-Voice') CE) was a Sarvāstivāda or Mahasanghika Buddhist philosopher, ...

, Asanga

Asaṅga (, ; Romaji: ''Mujaku'') ( fl. 4th century C.E.) was "one of the most important spiritual figures" of Mahayana Buddhism and the "founder of the Yogachara school".Engle, Artemus (translator), Asanga, ''The Bodhisattva Path to Unsurpassed ...

, Vasubandhu

Vasubandhu (; Tibetan: དབྱིག་གཉེན་ ; floruit, fl. 4th to 5th century CE) was an influential bhikkhu, Buddhist monk and scholar from ''Puruṣapura'' in ancient India, modern day Peshawar, Pakistan. He was a philosopher who ...

, and Dignaga. Mahāyāna Buddhists seem to have been active in the Kushan Empire

The Kushan Empire ( grc, Βασιλεία Κοσσανῶν; xbc, Κυϸανο, ; sa, कुषाण वंश; Brahmi: , '; BHS: ; xpr, 𐭊𐭅𐭔𐭍 𐭇𐭔𐭕𐭓, ; zh, 貴霜 ) was a syncretic empire, formed by the Yuezhi, i ...

(30–375 CE), a period that saw great missionary and literary activities by Buddhists. This is supported by the works of the historian Taranatha

Tāranātha (1575–1634) was a Lama of the Jonang school of Tibetan Buddhism. He is widely considered its most remarkable scholar and exponent.

Taranatha was born in Tibet, supposedly on the birthday of Padmasambhava. His original name was Kun ...

.[Dutt, Nalinaksha (1978). ''Mahāyāna Buddhism'', pp. 16-27. Delhi.]

Growth

The Mahāyāna movement (or movements) remained quite small until it experienced much growth in

The Mahāyāna movement (or movements) remained quite small until it experienced much growth in the fifth century

''The Fifth Century'' is a classical and choral studio album by Gavin Bryars, conducted by Donald Nally, and performed by The Crossing choir with the saxophone quartet PRISM. This album was released in the label ECM New Series in November 201 ...

. Very few manuscripts have been found before the fifth century (the exceptions are from Bamiyan). According to Walser, "the fifth and sixth centuries appear to have been a watershed for the production of Mahāyāna manuscripts." Likewise it is only in the 4th and 5th centuries CE that epigraphic evidence shows some kind of popular support for Mahāyāna, including some possible royal support at the kingdom of Shan shan

Shanshan (; ug, پىچان, Pichan, Piqan) was a kingdom located at the north-eastern end of the Taklamakan Desert near the great, but now mostly dry, salt lake known as Lop Nur.

The kingdom was originally an independent city-state, known in t ...

as well as in Bamiyan and Mathura

Mathura () is a city and the administrative headquarters of Mathura district in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. It is located approximately north of Agra, and south-east of Delhi; about from the town of Vrindavan, and from Govardhan. ...

.[Walser, Joseph, ''Nagarjuna in Context: Mahayana Buddhism and Early Indian Culture,'' Columbia University Press, 2005, p. 34.]

Still, even after the 5th century, the epigraphic evidence which uses the term Mahāyāna is still quite small and is notably mainly monastic, not lay.Faxian

Faxian (法顯 ; 337 CE – c. 422 CE), also referred to as Fa-Hien, Fa-hsien and Sehi, was a Chinese Buddhist monk and translator who traveled by foot from China to India to acquire Buddhist texts. Starting his arduous journey about age 60, h ...

(337–422 CE), Xuanzang

Xuanzang (, ; 602–664), born Chen Hui / Chen Yi (), also known as Hiuen Tsang, was a 7th-century Chinese Buddhist monk, scholar, traveler, and translator. He is known for the epoch-making contributions to Chinese Buddhism, the travelogue of ...

(602–664), Yijing

The ''I Ching'' or ''Yi Jing'' (, ), usually translated ''Book of Changes'' or ''Classic of Changes'', is an ancient Chinese divination text that is among the oldest of the Chinese classics. Originally a divination manual in the Western Zhou ...

(635–713 CE) were traveling to India, and their writings do describe monasteries which they label 'Mahāyāna' as well as monasteries where both Mahāyāna monks and non-Mahāyāna monks lived together.

After the fifth century, Mahāyāna Buddhism and its institutions slowly grew in influence. Some of the most influential institutions became massive monastic university complexes such as Nalanda

Nalanda (, ) was a renowned ''mahavihara'' (Buddhist monastic university) in ancient Magadha (modern-day Bihar), India.[Gupta

Gupta () is a common surname or last name of Indian origin. It is based on the Sanskrit word गोप्तृ ''goptṛ'', which means 'guardian' or 'protector'. According to historian R. C. Majumdar, the surname ''Gupta'' was adopted by se ...]

emperor, Kumaragupta I

Kumaragupta I ( Gupta script: ''Ku-ma-ra-gu-pta'', r. c. 415–455 CE) was an emperor of the Gupta Empire of Ancient India. A son of the Gupta emperor Chandragupta II and queen Dhruvadevi, he seems to have maintained control of his inherited t ...

) and Vikramashila

Vikramashila (Sanskrit: विक्रमशिला, IAST: , Bengali:- বিক্রমশিলা, Romanisation:- Bikrômôśilā ) was one of the three most important Buddhist monasteries in India during the Pala Empire, along with N ...

(established under Dharmapala

A ''dharmapāla'' (, , ja, 達磨波羅, 護法善神, 護法神, 諸天善神, 諸天鬼神, 諸天善神諸大眷屬) is a type of wrathful god in Buddhism. The name means "''dharma'' protector" in Sanskrit, and the ''dharmapālas'' are als ...

c. 783 to 820) which were centers of various branches of scholarship, including Mahāyāna philosophy. The Nalanda complex eventually became the largest and most influential Buddhist center in India for centuries. Even so, as noted by Paul Williams, "it seems that fewer than 50 percent of the monks encountered by Xuanzang (Hsüan-tsang; c. 600–664) on his visit to India actually were Mahāyānists."

Expansion outside of India

Over time Indian Mahāyāna texts and philosophy reached Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t ...

and China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

through trade routes like the Silk Road

The Silk Road () was a network of Eurasian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over 6,400 kilometers (4,000 miles), it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and reli ...

, later spreading throughout East Asia

East Asia is the eastern region of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The modern states of East Asia include China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. China, North Korea, South Korea and ...

. Over time, Central Asian Buddhism

Buddhism in Central Asia refers to the forms of Buddhism (mainly Mahayana) that existed in Central Asia, which were historically especially prevalent along the Silk Road. The history of Buddhism in Central Asia is closely related to the Silk ...

became heavily influenced by Mahāyāna and it was a major source for Chinese Buddhism. Mahāyāna works have also been found in Gandhāra

Gandhāra is the name of an ancient region located in the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent, more precisely in present-day north-west Pakistan and parts of south-east Afghanistan. The region centered around the Peshawar Val ...

, indicating the importance of this region for the spread of Mahāyāna. Central Asian Mahāyāna scholars were very important in the Silk Road Transmission of Buddhism

Buddhism entered Han China via the Silk Road, beginning in the 1st or 2nd century CE. The first documented translation efforts by Buddhist monks in China were in the 2nd century CE via the Kushan Empire into the Chinese territory bordering the ...

. They include translators like Lokakṣema (c. 167–186), Dharmarakṣa

(, J. Jiku Hōgo; K. Ch’uk Pǒphom c. 233-310) was one of the most important early translators of Mahayana sutras into Chinese. Several of his translations had profound effects on East Asian Buddhism. He is described in scriptural catalogue ...

(c. 265–313), Kumārajīva

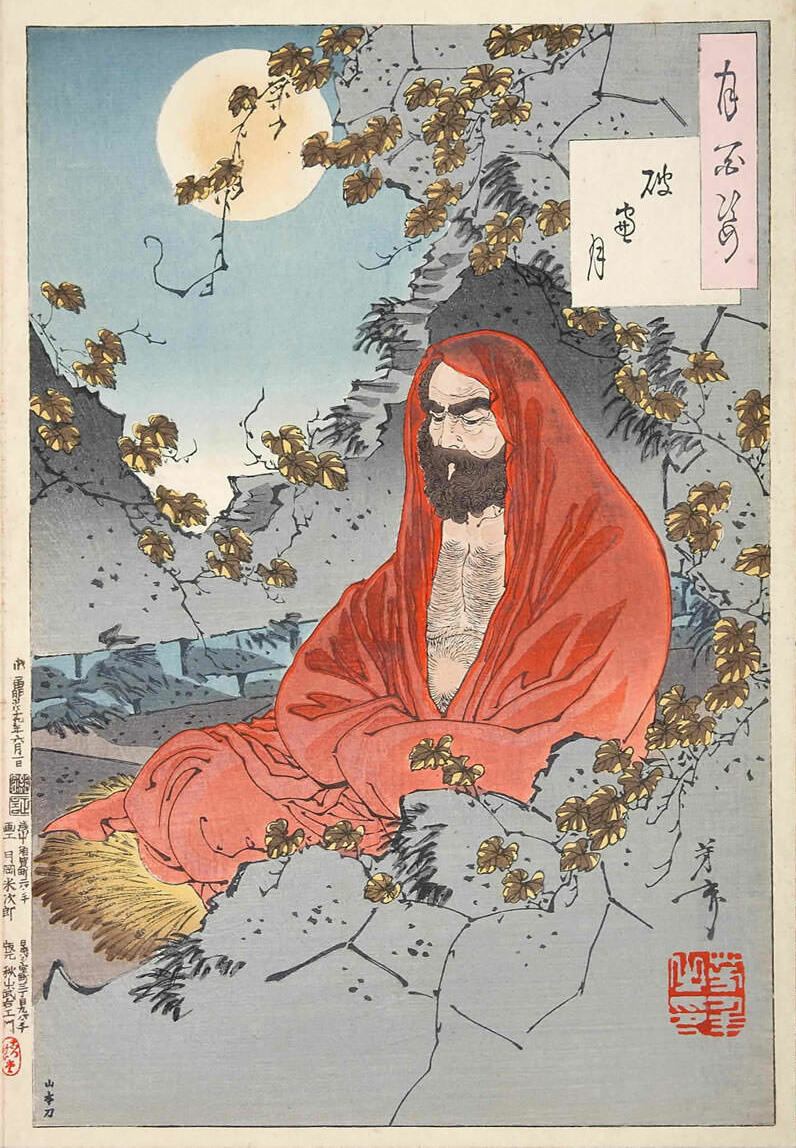

Kumārajīva (Sanskrit: कुमारजीव; , 344–413 CE) was a Buddhist monk, scholar, missionary and translator from the Kingdom of Kucha (present-day Aksu Prefecture, Xinjiang, China). Kumārajīva is seen as one of the greatest ...

(c. 401), and Dharmakṣema (धर्मक्षेम, transliterated 曇無讖 (), translated 竺法豐 (); 385–433 CE) was a Buddhist monk, originally from Magadha in India, who went to China after studying and teaching in Kashmir and Kucha. He had been residing in ...

(385–433). The site of Dunhuang

Dunhuang () is a county-level city in Northwestern Gansu Province, Western China. According to the 2010 Chinese census, the city has a population of 186,027, though 2019 estimates put the city's population at about 191,800. Dunhuang was a major ...

seems to have been a particularly important place for the study of Mahāyāna Buddhism.Faxian

Faxian (法顯 ; 337 CE – c. 422 CE), also referred to as Fa-Hien, Fa-hsien and Sehi, was a Chinese Buddhist monk and translator who traveled by foot from China to India to acquire Buddhist texts. Starting his arduous journey about age 60, h ...

(c. 337–422 CE) had also begun to travel to India (now dominated by the Guptas) to bring back Buddhist teachings, especially Mahāyāna works. These figures also wrote about their experiences in India and their work remains invaluable for understanding Indian Buddhism. In some cases Indian Mahāyāna traditions were directly transplanted, as with the case of the East Asian Madhymaka (by Kumārajīva

Kumārajīva (Sanskrit: कुमारजीव; , 344–413 CE) was a Buddhist monk, scholar, missionary and translator from the Kingdom of Kucha (present-day Aksu Prefecture, Xinjiang, China). Kumārajīva is seen as one of the greatest ...

) and East Asian Yogacara (especially by Xuanzang

Xuanzang (, ; 602–664), born Chen Hui / Chen Yi (), also known as Hiuen Tsang, was a 7th-century Chinese Buddhist monk, scholar, traveler, and translator. He is known for the epoch-making contributions to Chinese Buddhism, the travelogue of ...

). Later, new developments in Chinese Mahāyāna led to new Chinese Buddhist traditions like Tiantai

Tiantai or T'ien-t'ai () is an East Asian Buddhist school of Mahāyāna Buddhism that developed in 6th-century China. The school emphasizes the ''Lotus Sutra's'' doctrine of the "One Vehicle" (''Ekayāna'') as well as Mādhyamaka philosophy, ...

, Huayen

The Huayan or Flower Garland school of Buddhism (, from sa, अवतंसक, Avataṃsaka) is a tradition of Mahayana Buddhist philosophy that first flourished in China during the Tang dynasty (618-907). The Huayan worldview is based prima ...

, Pure Land

A pure land is the celestial realm of a buddha or bodhisattva in Mahayana Buddhism. The term "pure land" is particular to East Asian Buddhism () and related traditions; in Sanskrit the equivalent concept is called a buddha-field (Sanskrit ). Th ...

and Chan Buddhism

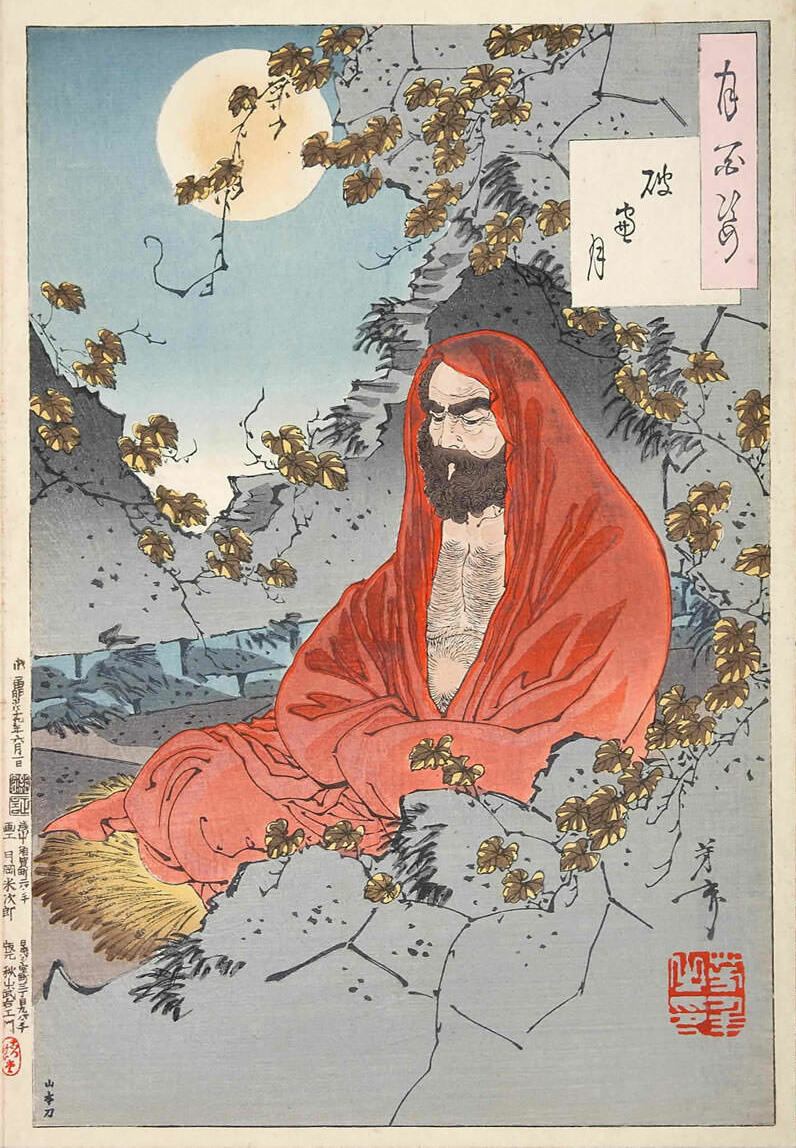

Chan (; of ), from Sanskrit '' dhyāna'' (meaning "meditation" or "meditative state"), is a Chinese school of Mahāyāna Buddhism. It developed in China from the 6th century CE onwards, becoming especially popular during the Tang and So ...

(Zen). These traditions would then spread to Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

, Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

and Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

.

Forms of Mahāyāna Buddhism which are mainly based on the doctrines of Indian Mahāyāna sutras are still popular in East Asian Buddhism

East Asian Buddhism or East Asian Mahayana is a collective term for the schools of Mahāyāna Buddhism that developed across East Asia which follow the Chinese Buddhist canon. These include the various forms of Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Vi ...

, which is mostly dominated by various branches of Mahāyāna Buddhism. Paul Williams has noted that in this tradition in the Far East, primacy has always been given to the study of the Mahāyāna sūtras.[Williams, Paul (1989). ''Mahayana Buddhism'': p. 103]

Later developments

Beginning during the

Beginning during the Gupta

Gupta () is a common surname or last name of Indian origin. It is based on the Sanskrit word गोप्तृ ''goptṛ'', which means 'guardian' or 'protector'. According to historian R. C. Majumdar, the surname ''Gupta'' was adopted by se ...

(c. 3rd century CE–575 CE) period a new movement began to develop which drew on previous Mahāyāna doctrine as well as new Pan-Indian tantric ideas. This came to be known by various names such as Vajrayāna

Vajrayāna ( sa, वज्रयान, "thunderbolt vehicle", "diamond vehicle", or "indestructible vehicle"), along with Mantrayāna, Guhyamantrayāna, Tantrayāna, Secret Mantra, Tantric Buddhism, and Esoteric Buddhism, are names referring t ...

(Tibetan: ''rdo rje theg pa''), Mantrayāna, and Esoteric Buddhism or "Secret Mantra" (''Guhyamantra''). This new movement continued into the Pala era (8th century–12th century CE), during which it grew to dominate Indian Buddhism. Possibly led by groups of wandering tantric yogis named mahasiddha

Mahasiddha (Sanskrit: ''mahāsiddha'' "great adept; ) is a term for someone who embodies and cultivates the " siddhi of perfection". A siddha is an individual who, through the practice of sādhanā, attains the realization of siddhis, psychic ...

s, this movement developed new tantric spiritual practices and also promoted new texts called the Buddhist Tantras

The Buddhist Tantras are a varied group of Indian and Tibetan texts which outline unique views and practices of the Buddhist tantra religious systems.

Overview

Buddhist Tantric texts began appearing in the Gupta Empire period, though there are ...

. Philosophically, Vajrayāna Buddhist thought remained grounded in the Mahāyāna Buddhist ideas of Madhyamaka, Yogacara

Yogachara ( sa, योगाचार, IAST: '; literally "yoga practice"; "one whose practice is yoga") is an influential tradition of Buddhist philosophy and psychology emphasizing the study of cognition, perception, and consciousness through t ...

and Buddha-nature. Tantric Buddhism generally deals with new forms of meditation and ritual which often makes use of the visualization of Buddhist deities (including Buddhas, bodhisattvas, dakini

A ḍākinī ( sa, डाकिनी; ; mn, хандарма; ; alternatively 荼枳尼, ; 荼吉尼, ; or 吒枳尼, ; Japanese: 荼枳尼 / 吒枳尼 / 荼吉尼, ''dakini'') is a type of female spirit, goddess, or demon in Hinduism and Bud ...

s, and fierce deities

In Buddhism, wrathful deities or fierce deities are the fierce, wrathful or forceful (Tibetan: ''trowo'', Sanskrit: ''krodha'') forms (or "aspects", "manifestations") of enlightened Buddhas, Bodhisattvas or Devas (divine beings); normally the sam ...

) and the use of mantras. Most of these practices are esoteric and require ritual initiation or introduction by a tantric master (''vajracarya'') or guru

Guru ( sa, गुरु, IAST: ''guru;'' Pali'': garu'') is a Sanskrit term for a "mentor, guide, expert, or master" of certain knowledge or field. In pan-Indian traditions, a guru is more than a teacher: traditionally, the guru is a reverentia ...

.

The source and early origins of Vajrayāna

Vajrayāna ( sa, वज्रयान, "thunderbolt vehicle", "diamond vehicle", or "indestructible vehicle"), along with Mantrayāna, Guhyamantrayāna, Tantrayāna, Secret Mantra, Tantric Buddhism, and Esoteric Buddhism, are names referring t ...

remain a subject of debate among scholars. Some scholars like Alexis Sanderson

Alexis G. J. S. Sanderson (born 1948) is an indologist and Emeritus Fellow of All Souls College at the University of Oxford.

Early life

After taking undergraduate degrees in Classics and Sanskrit at Balliol College from 1968 to 1971, Alexis Sande ...

argue that Vajrayāna derives its tantric content from Shaivism

Shaivism (; sa, शैवसम्प्रदायः, Śaivasampradāyaḥ) is one of the major Hindu traditions, which worships Shiva as the Supreme Being. One of the largest Hindu denominations, it incorporates many sub-traditions rangi ...

and that it developed as a result of royal courts sponsoring both Buddhism and Saivism

Shaivism (; sa, शैवसम्प्रदायः, Śaivasampradāyaḥ) is one of the major Hindu traditions, which worships Shiva as the Supreme Being. One of the largest Hindu denominations, it incorporates many sub-traditions rangin ...

. Sanderson argues that Vajrayāna works like the Samvara

''Samvara'' (''saṃvara'') is one of the '' tattva'' or the fundamental reality of the world as per the Jain philosophy. It means stoppage—the stoppage of the influx of the material karmas into the soul consciousness. The karmic process in ...

and Guhyasamaja texts show direct borrowing from Shaiva tantric literature. However, other scholars such as Ronald M. Davidson question the idea that Indian tantrism

Tantra (; sa, तन्त्र, lit=loom, weave, warp) are the esoteric traditions of Hinduism and Buddhism that developed on the Indian subcontinent from the middle of the 1st millennium CE onwards. The term ''tantra'', in the Indian ...

developed in Shaivism first and that it was then adopted into Buddhism. Davidson points to the difficulties of establishing a chronology for the Shaiva tantric literature and argues that both traditions developed side by side, drawing on each other as well as on local Indian tribal religion.

Whatever the case, this new tantric form of Mahāyāna Buddhism became extremely influential in India, especially in Kashmir

Kashmir () is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, the term encompas ...

and in the lands of the Pala Empire

The Pāla Empire (r. 750-1161 CE) was an imperial power during the post-classical period in the Indian subcontinent, which originated in the region of Bengal. It is named after its ruling dynasty, whose rulers bore names ending with the suffi ...

. It eventually also spread north into Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t ...

, the Tibetan plateau

The Tibetan Plateau (, also known as the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau or the Qing–Zang Plateau () or as the Himalayan Plateau in India, is a vast elevated plateau located at the intersection of Central, South and East Asia covering most of the Ti ...

and to East Asia. Vajrayāna remains the dominant form of Buddhism in Tibet

Tibetan Buddhism (also referred to as Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, Lamaism, Lamaistic Buddhism, Himalayan Buddhism, and Northern Buddhism) is the form of Buddhism practiced in Tibet and Bhutan, where it is the dominant religion. It is also in majo ...

, in surrounding regions like Bhutan

Bhutan (; dz, འབྲུག་ཡུལ་, Druk Yul ), officially the Kingdom of Bhutan,), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is situated in the Eastern Himalayas, between China in the north and India in the south. A mountainous ...

and in Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers an area of , with a population of just 3.3 million, ...

. Esoteric elements are also an important part of East Asian Buddhism where it is referred to by various terms. These include: '' Zhēnyán'' (Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of ...

: 真言, literally "true word", referring to mantra), ''Mìjiao'' (Chinese: 密教; Esoteric Teaching), ''Mìzōng'' (密宗; "Esoteric Tradition") or ''Tángmì'' (唐密; "Tang (Dynasty) Esoterica") in Chinese and Shingon

file:Koyasan (Mount Koya) monks.jpg, Shingon monks at Mount Koya

is one of the major schools of Buddhism in Japan and one of the few surviving Vajrayana lineages in East Asia, originally spread from India to China through traveling monks suc ...

, Tomitsu, Mikkyo, and Taimitsu in Japanese.

Worldview

Few things can be said with certainty about Mahāyāna Buddhism in general other than that the Buddhism practiced in

Few things can be said with certainty about Mahāyāna Buddhism in general other than that the Buddhism practiced in China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guine ...

, Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

, Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

, Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa people, ...

, Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers an area of , with a population of just 3.3 million, ...

and Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

is Mahāyāna Buddhism. Mahāyāna can be described as a loosely bound collection of many teachings and practices (some of which are seemingly contradictory). Mahāyāna constitutes an inclusive and broad set of traditions characterized by plurality and the adoption of a vast number of new sutras

''Sutra'' ( sa, सूत्र, translit=sūtra, translit-std=IAST, translation=string, thread)Monier Williams, ''Sanskrit English Dictionary'', Oxford University Press, Entry fo''sutra'' page 1241 in Indian literary traditions refers to an aph ...

, ideas and philosophical treatises in addition to the earlier Buddhist texts.

Broadly speaking, Mahāyāna Buddhists accept the classic Buddhist doctrines found in early Buddhism (i.e. the ''Nikāya

''Nikāya'' () is a Pāli word meaning "volume". It is often used like the Sanskrit word '' āgama'' () to mean "collection", "assemblage", "class" or "group" in both Pāḷi and Sanskrit. It is most commonly used in reference to the Pali Buddhist ...

'' and Āgamas), such as the Middle Way

The Middle Way ( pi, ; sa, ) as well as "teaching the Dharma by the middle" (''majjhena dhammaṃ deseti'') are common Buddhist terms used to refer to two major aspects of the Dharma, that is, the teaching of the Buddha.; my, အလယ်� ...

, Dependent origination

A dependant is a person who relies on another as a primary source of income. A common-law spouse who is financially supported by their partner may also be included in this definition. In some jurisdictions, supporting a dependant may enabl ...

, the Four Noble Truths

In Buddhism, the Four Noble Truths (Sanskrit: ; pi, cattāri ariyasaccāni; "The four Arya satyas") are "the truths of the Noble Ones", the truths or realities for the "spiritually worthy ones".[aFour Noble Truths: BUDDHIST PHILOSOPHY Encycl ...

, the Noble Eightfold Path, the Refuge (Buddhism), Three Jewels, the Three marks of existence and the ''Bodhipakkhiyādhammā, bodhipakṣadharmas'' (aids to awakening). Mahāyāna Buddhism further accepts some of the ideas found in Buddhist Abhidharma thought. However, Mahāyāna also adds numerous Mahāyāna texts and doctrines, which are seen as definitive and in some cases superior teachings.

The Buddhas

Buddhahood, Buddhas and

Buddhahood, Buddhas and bodhisattva

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva ( ; sa, 𑀩𑁄𑀥𑀺𑀲𑀢𑁆𑀢𑁆𑀯 (Brahmī), translit=bodhisattva, label=Sanskrit) or bodhisatva is a person who is on the path towards bodhi ('awakening') or Buddhahood.

In the Early Buddhist schools ...

s (beings on their way to Buddhahood) are central elements of Mahāyāna. Mahāyāna has a vastly expanded Buddhist cosmology, cosmology and Buddhist deities, theology, with various Buddhas and powerful bodhisattvas residing in different worlds and buddha-fields (''buddha kshetra'').[Williams, Paul, ''Mahayana Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations,'' Routledge, 2008, p. 21.] Buddhas unique to Mahāyāna include the Buddhas Amitābha

Amitābha ( sa, अमिताभ, IPA: ), also known as Amitāyus, is the primary Buddha of Pure Land Buddhism. In Vajrayana Buddhism, he is known for his longevity, discernment, pure perception, purification of aggregates, and deep awarene ...

("Infinite Light"), Five Wisdom Buddhas, Akṣobhya ("the Imperturbable"), Bhaisajyaguru, Bhaiṣajyaguru ("Medicine guru") and Vairocana

Vairocana (also Mahāvairocana, sa, वैरोचन) is a cosmic buddha from Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism. Vairocana is often interpreted, in texts like the ''Avatamsaka Sutra'', as the dharmakāya of the historical Gautama Buddha. In East ...

("the Illuminator"). In Mahāyāna, a Buddha is seen as a being that has achieved the highest kind of awakening due to his superior compassion and wish to help all beings.

An important feature of Mahāyāna is the way that it understands the nature of a Buddha, which differs from non-Mahāyāna understandings. Mahāyāna texts not only often depict numerous Buddhas besides Gautama Buddha, Sakyamuni, but see them as transcendental or supramundane (''lokuttara'') beings with great powers and huge lifetimes. The ''Lotus Sutra, White Lotus Sutra'' famously describes the lifespan of the Buddha as immeasurable and states that he actually achieved Buddhahood countless of eons (''kalpas'') ago and has been teaching the Dharma through his numerous avatars for an unimaginable period of time.

Furthermore, Buddhas are active in the world, constantly devising ways to teach and help all sentient beings. According to Paul Williams, in Mahāyāna, a Buddha is often seen as "a spiritual king, relating to and caring for the world", rather than simply a teacher who after his death "has completely 'gone beyond' the world and its cares".[Williams, Paul, ''Mahayana Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations,'' Routledge, 2008, p. 27.] Gautama Buddha, Buddha Sakyamuni's life and death on earth are then usually understood Docetism, docetically as a "mere appearance", his death is a show, while in actuality he remains out of compassion to help all sentient beings.emptiness

Emptiness as a human condition is a sense of generalized boredom, social alienation and apathy. Feelings of emptiness often accompany dysthymia, depression, loneliness, anhedonia,

despair, or other mental/emotional disorders, including schizoid ...

or ''Tathātā, Thusness''.

The Bodhisattvas

The Mahāyāna bodhisattva path (''mārga'') or vehicle (''Yana (Buddhism), yāna'') is seen as being the superior Spirituality, spiritual path by Mahāyānists, over and above the paths of those who seek

The Mahāyāna bodhisattva path (''mārga'') or vehicle (''Yana (Buddhism), yāna'') is seen as being the superior Spirituality, spiritual path by Mahāyānists, over and above the paths of those who seek arhat

In Buddhism, an ''arhat'' (Sanskrit: अर्हत्) or ''arahant'' (Pali: अरहन्त्, 𑀅𑀭𑀳𑀦𑁆𑀢𑁆) is one who has gained insight into the true nature of existence and has achieved ''Nirvana'' and liberated ...

ship or "solitary buddhahood" for their own sake (''Śrāvakayāna'' and ''Pratyekabuddhayāna''). Mahāyāna Buddhists generally hold that pursuing only the personal release from suffering i.e. Nirvana (Buddhism), nirvāṇa is a smaller or inferior aspiration (called "''hinayana''"), because it lacks the wish and resolve to liberate all other sentient beings from saṃsāra (the round of Rebirth (Buddhism), rebirth) by becoming a Buddha.''[Williams (2008), pp. 27-30, 46.][Conze, Edward]

The Perfection of Wisdom in eight thousand lines and its verse summary

/ref>''

This wish to help others is called ''bodhicitta''. One who engages in this path to complete buddhahood is called a bodhisattva

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva ( ; sa, 𑀩𑁄𑀥𑀺𑀲𑀢𑁆𑀢𑁆𑀯 (Brahmī), translit=bodhisattva, label=Sanskrit) or bodhisatva is a person who is on the path towards bodhi ('awakening') or Buddhahood.

In the Early Buddhist schools ...

. High level bodhisattvas are seen as extremely powerful supramundane beings which are objects of devotion and prayer throughout Mahāyāna lands.[Williams and Tribe (2002), pp. 188-189.] Popular bodhisattvas which are revered across Mahāyāna include Avalokiteśvara, Avalokiteshvara, Manjushri, Tara (Buddhism), Tara and Maitreya. Bodhisattvas could reach the personal nirvana of the arhat

In Buddhism, an ''arhat'' (Sanskrit: अर्हत्) or ''arahant'' (Pali: अरहन्त्, 𑀅𑀭𑀳𑀦𑁆𑀢𑁆) is one who has gained insight into the true nature of existence and has achieved ''Nirvana'' and liberated ...

s, but they reject this goal and remain in saṃsāra to help others out of compassion.[Williams, Paul, ''Mahayana Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations,'' Routledge, 2008, p. 60.][Williams, Paul, ''Mahayana Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations,'' Routledge, 2008, p. 55.] According to Paul Williams, a Mahāyāna bodhisattva is best defined as:that being who has taken the vow to be reborn, no matter how many times this may be necessary, in order to attain the highest possible goal, that of Complete and Perfect Buddhahood. This is for the benefit of all sentient beings.

There are two models for the nature of the bodhisattvas, which are seen in the various Mahāyāna texts. One is the idea that a bodhisattva must postpone their awakening until Buddhahood is attained. This could take Kalpa (eon), eons and in the meantime, they will help countless beings. After reaching Buddhahood, they do pass on to nirvāṇa. The second model is the idea that there are two kinds of nirvāṇa, the nirvāṇa of an arhat and a superior type of nirvāṇa called ''apratiṣṭhita'' (non-abiding, not-established) that allows a Buddha to remain forever engaged in the world. As noted by Paul Williams, the idea of ''apratiṣṭhita nirvāṇa'' may have taken some time to develop and is not obvious in some of the early Mahāyāna literature.

The Bodhisattva Path

In most classic Mahāyāna sources (as well as in non-Mahāyāna sources on the topic), the bodhisattva path is said to take three or four Asaṃkhyeya, ''asaṃkheyyas'' ("incalculable eons"), requiring a huge number of lifetimes of practice.[Drewes, David, ]

Mahāyāna Sūtras and Opening of the Bodhisattva Path

', Paper presented at the XVIII the IABS Congress, Toronto 2017, Updated 2019.

[Williams and Tribe (2002), p. 176.] However, certain practices are sometimes held to provide shortcuts to Buddhahood (these vary widely by tradition). According to the ''Bodhipathapradīpa'' (''A Lamp for the Path to Awakening'') by the Indian master Atiśa, the central defining feature of a bodhisattva's path is the universal aspiration to end suffering for themselves and all other beings, i.e. ''bodhicitta''.[Williams, Paul, ''Mahayana Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations,'' Routledge, 2008, pp. 195–196.]

The bodhisattva's spiritual path is traditionally held to begin with the revolutionary event called the "arising of the Awakening Mind" (''bodhicittotpāda''), which is the wish to become a Buddha in order to help all beings.[Williams and Tribe (2002), pp. 177-178.] According to the Indian philosopher Shantideva, when great compassion and bodhicitta arises in a person's heart, they cease to be an ordinary person and become a "son or daughter of the Buddhas".bodhisattva

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva ( ; sa, 𑀩𑁄𑀥𑀺𑀲𑀢𑁆𑀢𑁆𑀯 (Brahmī), translit=bodhisattva, label=Sanskrit) or bodhisatva is a person who is on the path towards bodhi ('awakening') or Buddhahood.

In the Early Buddhist schools ...

is not unique to Mahāyāna Buddhism and it is found in Theravada and other early Buddhist schools. However, these schools held that becoming a bodhisattva required a prediction of one's future Buddhahood in the presence of a living Buddha.[Drewes, David, ''Mahayana Sutras'', forthcoming in Blackwell Companion to South and Southeast Asian Buddhism, Updated 2016] In Mahāyāna a bodhisattva is applicable to any person from the moment they intend to become a Buddha (i.e. the arising of bodhicitta) and without the requirement of a living Buddha.[Williams, Paul, ''Mahayana Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations,'' Routledge, 2008, pp. 29, 36, 43.]

The generation of bodhicitta may then be followed by the taking of the bodhisattva vows to "lead to Nirvana the whole immeasurable world of beings" as the ''Prajñaparamita'' ''sutras'' state. This compassionate commitment to help others is the central characteristic of the Mahāyāna bodhisattva.[Williams, Paul, ''Mahayana Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations,'' Routledge, 2008, p. 56, 200.] These vows may be accompanied by certain ethical guidelines or Bodhisattva Precepts, bodhisattva precepts. Numerous sutras also state that a key part of the bodhisattva path is the practice of a set of virtues called Pāramitā, ''pāramitās'' (transcendent or supreme virtues). Sometimes six are outlined: giving, ethical discipline, patient endurance, diligence, meditation and transcendent wisdom.[Nagarjuna, B. Dharmamitra (trans), ''Nagarjuna on the Six Perfections'', Kalavinka Press, 2009.]emptiness

Emptiness as a human condition is a sense of generalized boredom, social alienation and apathy. Feelings of emptiness often accompany dysthymia, depression, loneliness, anhedonia,

despair, or other mental/emotional disorders, including schizoid ...

of all phenomena, arising from study, deep consideration and meditation.

Bodhisattva levels

Various texts associate the beginning of the bodhisattva practice with what is called the "path of accumulation" or equipment (''saṃbhāra-mārga''), which is the first path of the classic Bhūmi (Buddhism)#Five Paths, five paths schema.[Williams, Paul, ''Mahayana Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations,'' Routledge, 2008, pp. 200–201.]

The ''Ten Stages Sutra, Daśabhūmika Sūtra'' as well as other texts also outline a series of bodhisattva levels or spiritual stages (Bhūmi (Buddhism), ''bhūmis'' ) on the path to Buddhahood. The various texts disagree on the number of stages however, the ''Daśabhūmika'' giving ten for example (and mapping each one to the ten paramitas), the ''Yogacarabhumi-sastra, Bodhisattvabhūmi'' giving seven and thirteen and the ''Avatamsaka Sutra, Avatamsaka'' outlining 40 stages.Tibetan Buddhism

Tibetan Buddhism (also referred to as Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, Lamaism, Lamaistic Buddhism, Himalayan Buddhism, and Northern Buddhism) is the form of Buddhism practiced in Tibet and Bhutan, where it is the dominant religion. It is also in majo ...

. According to Paul Williams, in these systems, the first Bhūmi (Buddhism), ''bhūmi'' is reached once one attains "direct, nonconceptual and nondual insight into emptiness in meditative absorption", which is associated with the path of seeing (''darśana-mārga'').

Skillful means and the One Vehicle

Skillful means or Expedient techniques (Skt. ''Upaya, upāya'') is another important virtue and doctrine in Mahāyāna Buddhism. The idea is most famously expounded in the ''Lotus Sutra, White Lotus Sutra'', and refers to any effective method or technique that is conducive to spiritual growth and leads beings to awakening and nirvana. This doctrine states that the Buddha adapts his teaching to whoever he is teaching to out of compassion. Because of this, it is possible that the Buddha may teach seemingly contradictory things to different people. This idea is also used to explain the vast textual corpus found in Mahāyāna.[Williams and Tribe (2002), p. 169.]

A closely related teaching is the doctrine of the One Vehicle (''ekayāna''). This teaching states that even though the Buddha is said to have taught three vehicles (the śrāvakayāna, disciples' vehicle, pratyekabuddhayāna, the vehicle of solitary Buddhas and the bodhisattva vehicle, which are accepted by all early Buddhist schools), these actually are all skillful means which lead to the same place: Buddhahood. Therefore, there really are not three vehicles in an ultimate sense, but one vehicle, the supreme vehicle of the Buddhas, which is taught in different ways depending on the faculties of individuals. Even those beings who think they have finished the path (i.e. the arhat

In Buddhism, an ''arhat'' (Sanskrit: अर्हत्) or ''arahant'' (Pali: अरहन्त्, 𑀅𑀭𑀳𑀦𑁆𑀢𑁆) is one who has gained insight into the true nature of existence and has achieved ''Nirvana'' and liberated ...

s) are actually not done, and they will eventually reach Buddhahood.

Prajñāpāramitā (Transcendent Knowledge)

Some of the key Mahāyāna teachings are found in the '' Prajñāpāramitā'' ("Transcendent Knowledge" or "Perfection of Wisdom") texts, which are some of the earliest Mahāyāna works. Prajñāpāramitā is a deep knowledge of reality which Buddhas and bodhisattvas attain. It is a transcendent, non-conceptual and Nondualism, non-dual kind of knowledge into the true nature of things. This wisdom is also associated with insight into the

Some of the key Mahāyāna teachings are found in the '' Prajñāpāramitā'' ("Transcendent Knowledge" or "Perfection of Wisdom") texts, which are some of the earliest Mahāyāna works. Prajñāpāramitā is a deep knowledge of reality which Buddhas and bodhisattvas attain. It is a transcendent, non-conceptual and Nondualism, non-dual kind of knowledge into the true nature of things. This wisdom is also associated with insight into the emptiness

Emptiness as a human condition is a sense of generalized boredom, social alienation and apathy. Feelings of emptiness often accompany dysthymia, depression, loneliness, anhedonia,

despair, or other mental/emotional disorders, including schizoid ...

(''śūnyatā'') of dharmas (phenomena) and their illusory nature (''Maya (religion), māyā''). This amounts to the idea that all phenomena (Dharma theory, ''dharmas'') without exception have "no essential unchanging core" (i.e. they lack ''Svabhava, svabhāva,'' an essence or inherent nature), and therefore have "no fundamentally real existence." These empty phenomena are also said to be conceptual constructions.[Williams and Tribe (2002), p. 135.]

Because of this, all ''dharmas'' (things, phenomena), even the Buddha's Teaching, the Buddha himself, Nirvana, Nirvāṇa and all living beings, are like "illusions" or "magic" (''māyā'') and "dreams" (''Swapna (philosophy), svapna'').

Madhyamaka (Centrism)

The Mahāyāna philosophical school termed

The Mahāyāna philosophical school termed Madhyamaka

Mādhyamaka ("middle way" or "centrism"; ; Tibetan: དབུ་མ་པ ; ''dbu ma pa''), otherwise known as Śūnyavāda ("the emptiness doctrine") and Niḥsvabhāvavāda ("the no ''svabhāva'' doctrine"), refers to a tradition of Buddhist ...

(Middle theory or Centrism, also known as ''śūnyavāda,'' 'the emptiness theory') was founded by the second-century figure of Nagarjuna

Nāgārjuna . 150 – c. 250 CE (disputed)was an Indian Mahāyāna Buddhist thinker, scholar-saint and philosopher. He is widely considered one of the most important Buddhist philosophers.Garfield, Jay L. (1995), ''The Fundamental Wisdom of ...

. This philosophical tradition focuses on refuting all theories which posit any kind of substance, inherent existence or intrinsic nature (''Svabhava, svabhāva'').

In his writings, Nagarjuna attempts to show that any theory of intrinsic nature is contradicted by the Buddha's theory of Pratītyasamutpāda, dependent origination, since anything that has an independent existence cannot be dependently originated. The ''śūnyavāda'' philosophers were adamant that their denial of Svabhava, ''svabhāva'' is not a kind of nihilism (against protestations to the contrary by their opponents).[Williams and Tribe (2002), pp. 70, 141.]