Bluntnose Stingray on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The bluntnose stingray or Say's stingray (''Hypanus say'', often misspelled ''sayi'') is a species of

The bluntnose stingray or Say's stingray (''Hypanus say'', often misspelled ''sayi'') is a species of

''say, Raja''

. Catalog of Fishes electronic version (January 15, 2010). Retrieved on February 17, 2010. Recently, there has been a push to use the correct original spelling again, though it has also been proposed that the

Biological Profiles: Bluntnose Stingray

. Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department. Retrieved on January 14, 2010. Adult bluntnose stingrays are seldom found in

The bluntnose stingray has a diamond-shaped

The bluntnose stingray has a diamond-shaped

The bluntnose stingray has generally

The bluntnose stingray has generally

"Confirmation of embryonic diapause in the bluntnose stingray ''Dasyatis say''"

Abstract from the American Elasmobranch Society 1999 Annual Meeting, State College, Pennsylvania. Including the extended period of diapause, the

''Dasyatis say'', Bluntnose stingray

a

FishBase

*

a

Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department

{{Good article

The bluntnose stingray or Say's stingray (''Hypanus say'', often misspelled ''sayi'') is a species of

The bluntnose stingray or Say's stingray (''Hypanus say'', often misspelled ''sayi'') is a species of stingray

Stingrays are a group of sea rays, which are cartilaginous fish related to sharks. They are classified in the suborder Myliobatoidei of the order Myliobatiformes and consist of eight families: Hexatrygonidae (sixgill stingray), Plesiobatidae ...

in the family

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Idea ...

Dasyatidae, native to the coastal waters of the western Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

from the U.S. state

In the United States, a state is a constituent political entity, of which there are 50. Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its sove ...

of Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

to Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in th ...

. It is a bottom-dwelling species that prefers sandy or muddy habitat

In ecology, the term habitat summarises the array of resources, physical and biotic factors that are present in an area, such as to support the survival and reproduction of a particular species. A species habitat can be seen as the physical ...

s deep, and is migratory in the northern portion of its range. Typically growing to across, the bluntnose stingray is characterized by a rhomboid pectoral fin

Fins are distinctive anatomical features composed of bony spines or rays protruding from the body of a fish. They are covered with skin and joined together either in a webbed fashion, as seen in most bony fish, or similar to a flipper, as se ...

disc with broadly rounded outer corners and an obtuse-angled snout. It has a whip-like tail with both an upper keel and a lower fin fold, and a line of small tubercle

In anatomy, a tubercle (literally 'small tuber', Latin for 'lump') is any round nodule, small eminence, or warty outgrowth found on external or internal organs of a plant or an animal.

In plants

A tubercle is generally a wart-like projection ...

s along the middle of its back.

More active at night than during the day when it is usually buried in sediment, the bluntnose stingray is a predator

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill t ...

of small benthic

The benthic zone is the ecological region at the lowest level of a body of water such as an ocean, lake, or stream, including the sediment surface and some sub-surface layers. The name comes from ancient Greek, βένθος (bénthos), meaning " ...

invertebrate

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chorda ...

s and bony fish

Osteichthyes (), popularly referred to as the bony fish, is a diverse superclass of fish that have skeletons primarily composed of bone tissue. They can be contrasted with the Chondrichthyes, which have skeletons primarily composed of cartil ...

es. This species is aplacental viviparous

Ovoviviparity, ovovivipary, ovivipary, or aplacental viviparity is a term used as a "bridging" form of reproduction between egg-laying oviparous and live-bearing viviparous reproduction. Ovoviviparous animals possess embryos that develop ins ...

, in which the unborn young are nourished initially by yolk

Among animals which produce eggs, the yolk (; also known as the vitellus) is the nutrient-bearing portion of the egg whose primary function is to supply food for the development of the embryo. Some types of egg contain no yolk, for example ...

, and later histotroph

Uterine glands or endometrial glands are tubular glands, lined by ciliated columnar epithelium, found in the functional layer of the endometrium that lines the uterus. Their appearance varies during the menstrual cycle. During the proliferative ph ...

("uterine milk") produced by their mother. Females give birth to 1–6 pups every May after a gestation period

In mammals, pregnancy is the period of reproduction during which a female carries one or more live offspring from implantation in the uterus through gestation. It begins when a fertilized zygote implants in the female's uterus, and ends once ...

of 11–12 months, most of which consists of a period of arrested embryonic development. The venom

Venom or zootoxin is a type of toxin produced by an animal that is actively delivered through a wound by means of a bite, sting, or similar action. The toxin is delivered through a specially evolved ''venom apparatus'', such as fangs or a st ...

ous tail spine of the bluntnose stingray is potentially dangerous to unwary beachgoers. The International Union for Conservation of Nature

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN; officially International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natu ...

(IUCN) has listed this species as near threatened.

Taxonomy and phylogeny

French naturalistCharles Alexandre Lesueur

Charles Alexandre Lesueur (1 January 1778 in Le Havre – 12 December 1846 in Le Havre) was a French naturalist, artist, and explorer. He was a prolific natural-history collector, gathering many type specimens in Australia, Southeast Asia, ...

originally described the bluntnose stingray from specimens collected in Little Egg Harbor

Little Egg Harbor is a brackish

Brackish water, sometimes termed brack water, is water occurring in a natural environment that has more salinity than freshwater, but not as much as seawater. It may result from mixing seawater (salt water) and ...

off the U.S. State

In the United States, a state is a constituent political entity, of which there are 50. Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its sove ...

of New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delawa ...

. He published his account in an 1819 volume of the ''Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia'', and named the new species ''Raja say'' in honor of Thomas Say

Thomas Say (June 27, 1787 – October 10, 1834) was an American entomologist, conchologist, and herpetologist. His studies of insects and shells, numerous contributions to scientific journals, and scientific expeditions to Florida, Georgia, the R ...

, one of the founding members of the Academy

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of secondary or tertiary higher learning (and generally also research or honorary membership). The name traces back to Plato's school of philosop ...

.Smith, H.M. (1907). ''The Fishes of North Carolina''. E.M. Uzzell & Co. pp. 44–45. The species was moved to the genus ''Dasyatis'' by subsequent authors. In 1841, German biologists Johannes Peter Müller

Johannes Peter Müller (14 July 1801 – 28 April 1858) was a German physiologist, comparative anatomist, ichthyologist, and herpetologist, known not only for his discoveries but also for his ability to synthesize knowledge. The paramesonephri ...

and Friedrich Gustav Jakob Henle

Friedrich Gustav Jakob Henle (; 9 July 1809 – 13 May 1885) was a German physician, pathologist, and anatomist. He is credited with the discovery of the loop of Henle in the kidney. His essay, "On Miasma and Contagia," was an early argument for ...

erroneously gave the specific epithet

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called nomenclature ("two-name naming system") or binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, bo ...

as ''sayi'' in their ''Systematische Beschreibung der Plagiostomen'', which thereafter became the typical spelling used in literature.Eschmeyer, W.N. and R. Fricke (eds)''say, Raja''

. Catalog of Fishes electronic version (January 15, 2010). Retrieved on February 17, 2010. Recently, there has been a push to use the correct original spelling again, though it has also been proposed that the

International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature

The International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) is an organization dedicated to "achieving stability and sense in the scientific naming of animals". Founded in 1895, it currently comprises 26 commissioners from 20 countries.

Orga ...

(ICZN) officially emend the spelling to ''sayi'', for consistency with previous usage.

Lisa Rosenberger's 2001 phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek φυλή/ φῦλον [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:γενετικός, γενετικός [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups ...

analysis, based on morphological characters, found that the bluntnose stingray is one of the more basal members of its genus, and that it is a sister species

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and ...

to the diamond stingray

The diamond stingray (''Dasyatis dipterura'') is a species of stingray in the family Dasyatidae. It is found in the coastal waters of the eastern Pacific Ocean from southern California to northern Chile, and around the Galápagos and Hawaiian I ...

(''D. dipterura'') of the western Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the conti ...

. The two species likely diverged before or with the formation of the Isthmus of Panama

The Isthmus of Panama ( es, Istmo de Panamá), also historically known as the Isthmus of Darien (), is the narrow strip of land that lies between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, linking North and South America. It contains the country ...

, some three million years ago.

Distribution and habitat

The bluntnose stingray is found in the westernAtlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

, from Long Island, New York

Long Island is a densely populated island in the southeastern region of the U.S. state of New York, part of the New York metropolitan area. With over 8 million people, Long Island is the most populous island in the United States and the 18t ...

southward through the Florida Keys

The Florida Keys are a coral cay archipelago located off the southern coast of Florida, forming the southernmost part of the continental United States. They begin at the southeastern coast of the Florida peninsula, about south of Miami, and e ...

, the northern Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United ...

, and the Greater and Lesser Antilles

The Lesser Antilles ( es, link=no, Antillas Menores; french: link=no, Petites Antilles; pap, Antias Menor; nl, Kleine Antillen) are a group of islands in the Caribbean Sea. Most of them are part of a long, partially volcanic island arc be ...

; on rare occasions it is found as far north as Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

, as far south as Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in th ...

, and as far west as Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

. It is absent from the southern Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean ...

coast of Central America

Central America ( es, América Central or ) is a subregion of the Americas. Its boundaries are defined as bordering the United States to the north, Colombia to the south, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. ...

. Reports of this species from off Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

and Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest ...

likely represent misidentifications of the groovebelly stingray

The groovebelly stingray (''Dasyatis hypostigma''), referred to as the butter stingray by fishery workers, is a species of stingray in the family Dasyatidae. It is found over sandy or muddy bottoms in shallow coastal waters off southern Brazil, ...

(''D. hypostigma'').

Common in coastal habitat

In ecology, the term habitat summarises the array of resources, physical and biotic factors that are present in an area, such as to support the survival and reproduction of a particular species. A species habitat can be seen as the physical ...

s such as bay

A bay is a recessed, coastal body of water that directly connects to a larger main body of water, such as an ocean, a lake, or another bay. A large bay is usually called a gulf, sea, sound, or bight. A cove is a small, circular bay with a na ...

s, lagoon

A lagoon is a shallow body of water separated from a larger body of water by a narrow landform, such as reefs, barrier islands, barrier peninsulas, or isthmuses. Lagoons are commonly divided into '' coastal lagoons'' (or ''barrier lagoons ...

s, and estuaries

An estuary is a partially enclosed coastal body of brackish water with one or more rivers or streams flowing into it, and with a free connection to the open sea. Estuaries form a transition zone between river environments and maritime environme ...

, the bluntnose stingray is a bottom-dwelling species usually found at a depth of , though it has been recorded from as deep as . It frequents sandy or muddy flats, preferring water with a salinity

Salinity () is the saltiness or amount of salt (chemistry), salt dissolved in a body of water, called saline water (see also soil salinity). It is usually measured in g/L or g/kg (grams of salt per liter/kilogram of water; the latter is dimensio ...

of 25–43 ppt and a temperature of .Collins, JBiological Profiles: Bluntnose Stingray

. Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department. Retrieved on January 14, 2010. Adult bluntnose stingrays are seldom found in

seagrass meadow

A seagrass meadow or seagrass bed is an underwater ecosystem formed by seagrasses. Seagrasses are marine (saltwater) plants found in shallow coastal waters and in the brackish waters of estuaries. Seagrasses are flowering plants with stems and ...

s or shoal

In oceanography, geomorphology, and geoscience, a shoal is a natural submerged ridge, bank, or bar that consists of, or is covered by, sand or other unconsolidated material and rises from the bed of a body of water to near the surface. It ...

s, though the latter serves as a habitat for young rays. Along the U.S. East Coast

The East Coast of the United States, also known as the Eastern Seaboard, the Atlantic Coast, and the Atlantic Seaboard, is the coastline along which the Eastern United States meets the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean. The eastern seaboard ...

, schools of bluntnose stingrays migrate long distances northward into bays and estuaries to spend the summer, and move back to southern offshore waters for winter.

Description

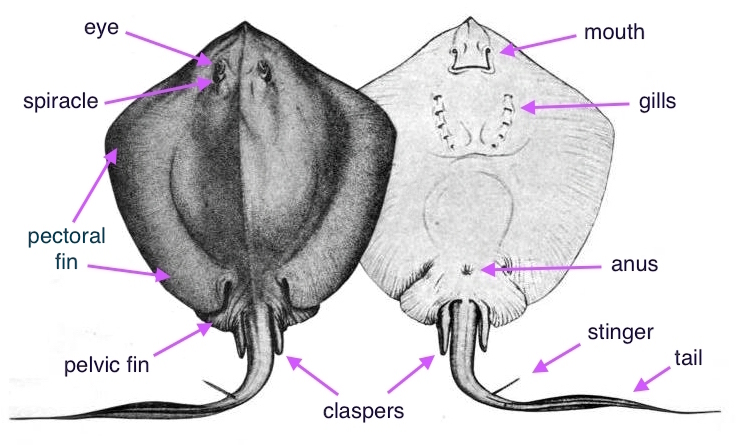

The bluntnose stingray has a diamond-shaped

The bluntnose stingray has a diamond-shaped pectoral fin

Fins are distinctive anatomical features composed of bony spines or rays protruding from the body of a fish. They are covered with skin and joined together either in a webbed fashion, as seen in most bony fish, or similar to a flipper, as se ...

disc about a sixth wider than long, with broadly rounded outer corners. The leading margins of the disc are nearly straight and converge at the tip of the snout at up to a 130° angle; the anterior disc shape distinguishes this species from the similar Atlantic stingray (''D. sabina''), which has a longer, more acute snout. The mouth is curved, with a central projection on the upper jaw that fits into an indentation on the lower jaw. There is a row of five papillae across the floor of the mouth, with the outermost pair smaller and set apart from the others. There are 36–50 upper tooth rows; the teeth have quadrangular bases and are arranged with a quincunx

A quincunx () is a geometric pattern consisting of five points arranged in a cross, with four of them forming a square or rectangle and a fifth at its center. The same pattern has other names, including "in saltire" or "in cross" in heraldry (d ...

pattern into flattened surfaces. The tooth crowns are rounded in females and juveniles, while those of males in breeding condition are triangular and pointed. The pelvic fins are triangular with rounded tips.

The whip-like tail measures over one and a half times as long as the disc and bears one or two long, serrated stinging spines on top, about a quarter of the tail length back from the base. The second spine, if present, is a replacement that periodically grows in front of the existing spine. Behind the spine, there are well-developed upper and lower fin folds, with the lower fold longer and wider than the upper. Small thorns or tubercles are found in a midline row from behind the eyes to the base of the tail spine, increasing in number with age. Adults also have prickles before and behind the eyes and on the outer parts of the disc. The dorsal coloration is grayish, reddish, or greenish brown; some individuals also possess bluish spots, are darker towards the sides and rear, or have a thin white disc margin. The ventral surface is whitish, sometimes with a dark disc margin or dark blotches. A record off French Guiana

French Guiana ( or ; french: link=no, Guyane ; gcr, label=French Guianese Creole, Lagwiyann ) is an overseas departments and regions of France, overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France on the northern Atlantic ...

gives the maximum disc width of this species as , but that specimen may have been misidentified and other sources give a maximum disc width of no more than . Females grow larger than males.

Biology and ecology

The bluntnose stingray has generally

The bluntnose stingray has generally nocturnal

Nocturnality is an animal behavior characterized by being active during the night and sleeping during the day. The common adjective is "nocturnal", versus diurnal meaning the opposite.

Nocturnal creatures generally have highly developed sens ...

habits and spends much of the day buried in the substrate. It has been known to follow the rising tide

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravity, gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide t ...

to forage in water barely deep enough to cover its body. This species preys upon small invertebrate

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chorda ...

s, including crustacean

Crustaceans (Crustacea, ) form a large, diverse arthropod taxon which includes such animals as decapods, seed shrimp, branchiopods, fish lice, krill, remipedes, isopods, barnacles, copepods, amphipods and mantis shrimp. The crustacean group ...

s, annelid worms, and bivalve

Bivalvia (), in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a class of marine and freshwater molluscs that have laterally compressed bodies enclosed by a shell consisting of two hinged parts. As a group, bival ...

and gastropod

The gastropods (), commonly known as snails and slugs, belong to a large taxonomic class of invertebrates within the phylum Mollusca called Gastropoda ().

This class comprises snails and slugs from saltwater, from freshwater, and from land. T ...

mollusc

Mollusca is the second-largest phylum of invertebrate animals after the Arthropoda, the members of which are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 85,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized. The number of fossil species is esti ...

s, and bony fish

Osteichthyes (), popularly referred to as the bony fish, is a diverse superclass of fish that have skeletons primarily composed of bone tissue. They can be contrasted with the Chondrichthyes, which have skeletons primarily composed of cartil ...

es. It mainly targets benthic and burrowing organism

In biology, an organism () is any living system that functions as an individual entity. All organisms are composed of cells (cell theory). Organisms are classified by taxonomy into groups such as multicellular animals, plants, and ...

s, but also opportunistically takes free-swimming prey. In Delaware Bay

Delaware Bay is the estuary outlet of the Delaware River on the northeast seaboard of the United States. It is approximately in area, the bay's freshwater mixes for many miles with the saltwater of the Atlantic Ocean.

The bay is bordered inlan ...

, this species feeds predominantly on the shrimp

Shrimp are crustaceans (a form of shellfish) with elongated bodies and a primarily swimming mode of locomotion – most commonly Caridea and Dendrobranchiata of the decapod order, although some crustaceans outside of this order are refer ...

'' Cragon septemspinosa'' and the blood worm ''Glycera dibranchiata

''Glycera dibranchiata'', also known as one variant of bloodworm, are segmented, red marine worms that grow up to 14-inches in length and have unique copper teeth made up of a mixture of protein, melanin and 10% copper. This copper concentratio ...

'', and its overall dietary composition is virtually identical to that of the roughtail stingray

The roughtail stingray (''Bathytoshia centroura'') is a species of stingray in the family Dasyatidae, with separate populations in coastal waters of the northwestern, eastern, and southwestern Atlantic Ocean. This bottom-dwelling species typica ...

(''D. centroura''), with which it shares the bay. The bluntnose stingray is preyed upon by larger fishes such as the bull shark

The bull shark (''Carcharhinus leucas''), also known as the Zambezi shark (informally zambi) in Africa and Lake Nicaragua shark in Nicaragua, is a species of requiem shark commonly found worldwide in warm, shallow waters along coasts and in ri ...

(''Carcharhinus leucas''). Known parasite

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson has ...

s of this species include the tapeworm

Eucestoda, commonly referred to as tapeworms, is the larger of the two subclasses of flatworms in the class Cestoda (the other subclass is Cestodaria). Larvae have six posterior hooks on the scolex (head), in contrast to the ten-hooked Cestodar ...

s ''Acanthobothrium brevissime'' and ''Kotorella pronosoma'', the monogenea

Monogeneans are a group of ectoparasitic flatworms commonly found on the skin, gills, or fins of fish. They have a direct lifecycle and do not require an intermediate host. Adults are hermaphrodites, meaning they have both male and female repro ...

n ''Listrocephalos corona'', and the trematode

Trematoda is a class of flatworms known as flukes. They are obligate internal parasites with a complex life cycle requiring at least two hosts. The intermediate host, in which asexual reproduction occurs, is usually a snail. The definitive host ...

s ''Monocotyle pricei'' and ''Multicalyx cristata''.

Like other stingrays, the bluntnose stingray is aplacental viviparous

Ovoviviparity, ovovivipary, ovivipary, or aplacental viviparity is a term used as a "bridging" form of reproduction between egg-laying oviparous and live-bearing viviparous reproduction. Ovoviviparous animals possess embryos that develop ins ...

. with the embryo

An embryo is an initial stage of development of a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male spe ...

s initially sustained by yolk

Among animals which produce eggs, the yolk (; also known as the vitellus) is the nutrient-bearing portion of the egg whose primary function is to supply food for the development of the embryo. Some types of egg contain no yolk, for example ...

. Later in development, finger-like extensions of the uterine epithelium

Epithelium or epithelial tissue is one of the four basic types of animal tissue, along with connective tissue, muscle tissue and nervous tissue. It is a thin, continuous, protective layer of compactly packed cells with a little intercellul ...

called "trophonemata" surround the embryo and deliver protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

and lipid

Lipids are a broad group of naturally-occurring molecules which includes fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids include ...

-rich histotroph

Uterine glands or endometrial glands are tubular glands, lined by ciliated columnar epithelium, found in the functional layer of the endometrium that lines the uterus. Their appearance varies during the menstrual cycle. During the proliferative ph ...

("uterine milk") produced by the mother. Only the left ovary

The ovary is an organ in the female reproductive system that produces an ovum. When released, this travels down the fallopian tube into the uterus, where it may become fertilized by a sperm. There is an ovary () found on each side of the body. ...

and uterus

The uterus (from Latin ''uterus'', plural ''uteri'') or womb () is the organ in the reproductive system of most female mammals, including humans that accommodates the embryonic and fetal development of one or more embryos until birth. The uter ...

in adult females are functional. Mating occurs during a well-defined period from April to June, peaking in May, with the males presumably using their pointed teeth to grasp the females for copulation

Sexual intercourse (or coitus or copulation) is a sexual activity typically involving the insertion and thrusting of the penis into the vagina for sexual pleasure or reproduction.Sexual intercourse most commonly means penile–vaginal penetra ...

. However, embryonic development

An embryo is an initial stage of development of a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male sperm ...

halts at the blastoderm A blastoderm ( germinal disc, blastodisc) is a single layer of embryonic epithelial tissue that makes up the blastula. It encloses the fluid filled blastocoel. Gastrulation follows blastoderm formation, where the tips of the blastoderm begins the ...

stage, shortly after the formation of the zygote

A zygote (, ) is a eukaryotic cell formed by a fertilization event between two gametes. The zygote's genome is a combination of the DNA in each gamete, and contains all of the genetic information of a new individual organism.

In multicellula ...

, and does not resume for approximately ten months. In the spring of the following year, the embryos rapidly mature over a period of 10–12 weeks. This period of embryonic diapause Embryonic diapause (from late 19th century English: dia- ‘through’ + pause- 'delay') (aka delayed implantation in mammals) is an evolutionary reproductive strategy used by several animal species across a number of kingdoms, including approximate ...

may reflect the greater availability of food in the spring.Morris, J.A., J. Wyffels, F.F. Snelson (Jr.) (1999)"Confirmation of embryonic diapause in the bluntnose stingray ''Dasyatis say''"

Abstract from the American Elasmobranch Society 1999 Annual Meeting, State College, Pennsylvania. Including the extended period of diapause, the

gestation period

In mammals, pregnancy is the period of reproduction during which a female carries one or more live offspring from implantation in the uterus through gestation. It begins when a fertilized zygote implants in the female's uterus, and ends once ...

lasts around 11–12 months, with 1–6 young being born in mid to late May. In 1941, in a shallow channel between Chincoteague Island and Cape Charles, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, several large bluntnose stingrays were observed repeatedly breaking the surface and swimming rapidly in straight lines, some with their tails thrashing in the air; others were seen rising slowly to the surface and "hanging" for several minutes. One of the rays was hooked and the shock of capture caused it to release five near-term fetus

A fetus or foetus (; plural fetuses, feti, foetuses, or foeti) is the unborn offspring that develops from an animal embryo. Following embryonic development the fetal stage of development takes place. In human prenatal development, fetal deve ...

es, suggesting that this activity may have been related to parturition

Birth is the act or process of bearing or bringing forth offspring, also referred to in technical contexts as parturition. In mammals, the process is initiated by hormones which cause the muscular walls of the uterus to contract, expelling the f ...

. The aborted young were pale with small yolk sac

The yolk sac is a membranous sac attached to an embryo, formed by cells of the hypoblast layer of the bilaminar embryonic disc. This is alternatively called the umbilical vesicle by the Terminologia Embryologica (TE), though ''yolk sac'' is ...

s, and a swelling in the place of their tail spines. Females begin ovulating a new batch of eggs immediately after giving birth, indicating that they have an annual reproductive cycle. Newborn rays measure across and weigh . Males mature sexually at disc width of and a weight of , while females mature at a disc width of and a weight of .

Human interactions

The bluntnose stingray is not aggressive, though it will defend itself if stepped on or otherwise incited. Its tail spine can inflict an excruciating injury, and can easily pierceleather

Leather is a strong, flexible and durable material obtained from the tanning, or chemical treatment, of animal skins and hides to prevent decay. The most common leathers come from cattle, sheep, goats, equine animals, buffalo, pigs and hogs, ...

or rubber

Rubber, also called India rubber, latex, Amazonian rubber, ''caucho'', or ''caoutchouc'', as initially produced, consists of polymers of the organic compound isoprene, with minor impurities of other organic compounds. Thailand, Malaysia, and ...

footwear. The paralytic

Paralysis (also known as plegia) is a loss of motor function in one or more muscles. Paralysis can also be accompanied by a loss of feeling (sensory loss) in the affected area if there is sensory damage. In the United States, roughly 1 in 50 ...

venom

Venom or zootoxin is a type of toxin produced by an animal that is actively delivered through a wound by means of a bite, sting, or similar action. The toxin is delivered through a specially evolved ''venom apparatus'', such as fangs or a st ...

delivered may have potentially life-threatening effects on those with heart or respiratory problems, and is the subject of biomedical and neurobiological

Neuroscience is the scientific study of the nervous system (the brain, spinal cord, and peripheral nervous system), its functions and disorders. It is a multidisciplinary science that combines physiology, anatomy, molecular biology, developme ...

research. This species is popular with ecotourist

Ecotourism is a form of tourism involving responsible travel (using sustainable transport) to natural areas, conserving the environment, and improving the well-being of the local people. Its purpose may be to educate the traveler, to provide fund ...

divers. Abundant and widespread, the bluntnose stingray is caught incidentally by commercial

Commercial may refer to:

* a dose of advertising conveyed through media (such as - for example - radio or television)

** Radio advertisement

** Television advertisement

* (adjective for:) commerce, a system of voluntary exchange of products and s ...

trawl

Trawling is a method of fishing that involves pulling a fishing net through the water behind one or more boats. The net used for trawling is called a trawl. This principle requires netting bags which are towed through water to catch different speci ...

and gillnet fisheries

Fishery can mean either the enterprise of raising or harvesting fish and other aquatic life; or more commonly, the site where such enterprise takes place ( a.k.a. fishing ground). Commercial fisheries include wild fisheries and fish farms, both ...

operating in nearshore U.S. waters; these activities are not a threat to its population, as most captured rays are released alive. The impact of fishing in the southern parts of its range is uncertain, but is unlikely to significantly affect the species as a whole as these activities occur outside its centers of distribution. The International Union for Conservation of Nature

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN; officially International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natu ...

has listed the bluntnose stingray as near threatened.

References

External links

''Dasyatis say'', Bluntnose stingray

a

FishBase

*

a

Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department

{{Good article

bluntnose stingray

The bluntnose stingray or Say's stingray (''Hypanus say'', often misspelled ''sayi'') is a species of stingray in the family Dasyatidae, native to the coastal waters of the western Atlantic Ocean from the U.S. state of Massachusetts to Venezue ...

Fish of the Caribbean

Fish of the Dominican Republic

Fish of the Western Atlantic

bluntnose stingray

The bluntnose stingray or Say's stingray (''Hypanus say'', often misspelled ''sayi'') is a species of stingray in the family Dasyatidae, native to the coastal waters of the western Atlantic Ocean from the U.S. state of Massachusetts to Venezue ...

Taxonomy articles created by Polbot

Taxobox binomials not recognized by IUCN