Bletchley Park on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Bletchley Park is an

Admiral Hugh Sinclair was the founder and head of GC&CS between 1919 and 1938 with Commander Alastair Denniston being operational head of the organization from 1919 to 1942, beginning with its formation from the Admiralty's Room 40 (NID25) and the

Admiral Hugh Sinclair was the founder and head of GC&CS between 1919 and 1938 with Commander Alastair Denniston being operational head of the organization from 1919 to 1942, beginning with its formation from the Admiralty's Room 40 (NID25) and the

The first personnel of the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) moved to Bletchley Park on 15 August 1939. The Naval, Military, and Air Sections were on the ground floor of the mansion, together with a telephone exchange, teleprinter room, kitchen, and dining room; the top floor was allocated to MI6. Construction of the wooden huts began in late 1939, and Elmers School, a neighbouring boys' boarding school in a Victorian Gothic redbrick building by a church, was acquired for the Commercial and Diplomatic Sections.

After the

The first personnel of the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) moved to Bletchley Park on 15 August 1939. The Naval, Military, and Air Sections were on the ground floor of the mansion, together with a telephone exchange, teleprinter room, kitchen, and dining room; the top floor was allocated to MI6. Construction of the wooden huts began in late 1939, and Elmers School, a neighbouring boys' boarding school in a Victorian Gothic redbrick building by a church, was acquired for the Commercial and Diplomatic Sections.

After the

Initially, when only a very limited amount of Enigma traffic was being read, deciphered non-Naval Enigma messages were sent from Hut 6 to Hut 3 which handled their translation and onward transmission. Subsequently, under Group Captain Eric Jones, Hut 3 expanded to become the heart of Bletchley Park's intelligence effort, with input from decrypts of " Tunny" (Lorenz SZ42) traffic and many other sources. Early in 1942 it moved into Block D, but its functions were still referred to as Hut 3.

Hut 3 contained a number of sections: Air Section "3A", Military Section "3M", a small Naval Section "3N", a multi-service Research Section "3G" and a large liaison section "3L". It also housed the Traffic Analysis Section, SIXTA. An important function that allowed the synthesis of raw messages into valuable

Initially, when only a very limited amount of Enigma traffic was being read, deciphered non-Naval Enigma messages were sent from Hut 6 to Hut 3 which handled their translation and onward transmission. Subsequently, under Group Captain Eric Jones, Hut 3 expanded to become the heart of Bletchley Park's intelligence effort, with input from decrypts of " Tunny" (Lorenz SZ42) traffic and many other sources. Early in 1942 it moved into Block D, but its functions were still referred to as Hut 3.

Hut 3 contained a number of sections: Air Section "3A", Military Section "3M", a small Naval Section "3N", a multi-service Research Section "3G" and a large liaison section "3L". It also housed the Traffic Analysis Section, SIXTA. An important function that allowed the synthesis of raw messages into valuable

Often a hut's number became so strongly associated with the work performed inside that even when the work was moved to another building it was still referred to by the original "Hut" designation.

* ''Hut 1'': The first hut, built in 1939 used to house the Wireless Station for a short time, later administrative functions such as transport, typing, and Bombe maintenance. The first Bombe, "Victory", was initially housed here.

* ''Hut 2'': A recreational hut for "beer, tea, and relaxation".

* '' Hut 3'': Intelligence: translation and analysis of Army and Air Force decrypts

* '' Hut 4'': Naval intelligence: analysis of Naval Enigma and

Often a hut's number became so strongly associated with the work performed inside that even when the work was moved to another building it was still referred to by the original "Hut" designation.

* ''Hut 1'': The first hut, built in 1939 used to house the Wireless Station for a short time, later administrative functions such as transport, typing, and Bombe maintenance. The first Bombe, "Victory", was initially housed here.

* ''Hut 2'': A recreational hut for "beer, tea, and relaxation".

* '' Hut 3'': Intelligence: translation and analysis of Army and Air Force decrypts

* '' Hut 4'': Naval intelligence: analysis of Naval Enigma and

Most German messages decrypted at Bletchley were produced by one or another version of the Enigma cipher machine, but an important minority were produced by the even more complicated twelve-rotor Lorenz SZ42 on-line teleprinter cipher machine.

Five weeks before the outbreak of war, Warsaw's Cipher Bureau revealed its achievements in breaking Enigma to astonished French and British personnel. The British used the Poles' information and techniques, and the Enigma clone sent to them in August 1939, which greatly increased their (previously very limited) success in decrypting Enigma messages.

Most German messages decrypted at Bletchley were produced by one or another version of the Enigma cipher machine, but an important minority were produced by the even more complicated twelve-rotor Lorenz SZ42 on-line teleprinter cipher machine.

Five weeks before the outbreak of war, Warsaw's Cipher Bureau revealed its achievements in breaking Enigma to astonished French and British personnel. The British used the Poles' information and techniques, and the Enigma clone sent to them in August 1939, which greatly increased their (previously very limited) success in decrypting Enigma messages.

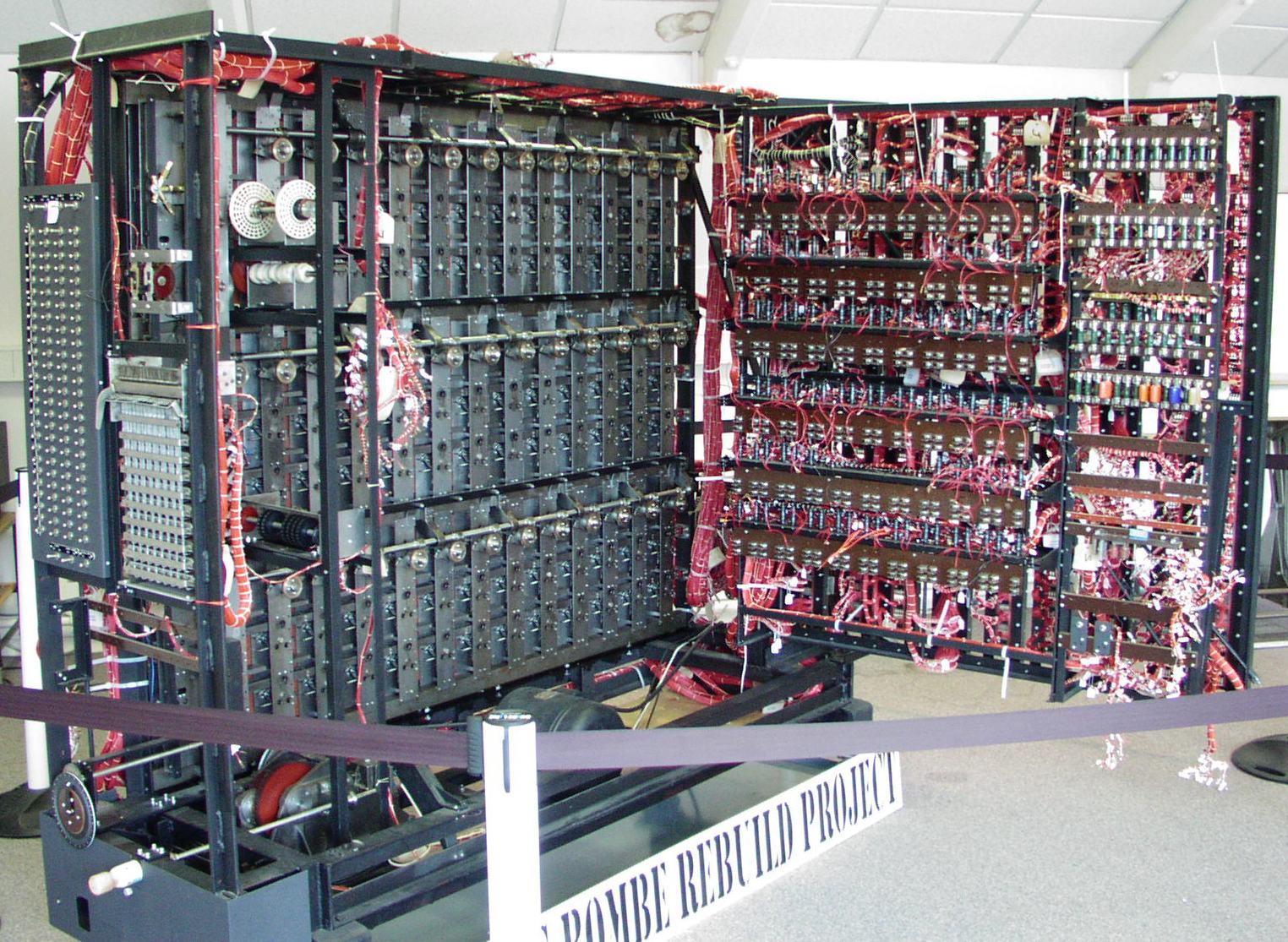

The bombe was an electromechanical device whose function was to discover some of the daily settings of the Enigma machines on the various German military networks. Its pioneering design was developed by

The bombe was an electromechanical device whose function was to discover some of the daily settings of the Enigma machines on the various German military networks. Its pioneering design was developed by  The Lorenz messages were codenamed ''Tunny'' at Bletchley Park. They were only sent in quantity from mid-1942. The Tunny networks were used for high-level messages between German High Command and field commanders. With the help of German operator errors, the cryptanalysts in the Testery (named after

The Lorenz messages were codenamed ''Tunny'' at Bletchley Park. They were only sent in quantity from mid-1942. The Tunny networks were used for high-level messages between German High Command and field commanders. With the help of German operator errors, the cryptanalysts in the Testery (named after

, Faculty of Classics, Cambridge University

June 2014 saw the completion of an £8 million restoration project by museum design specialist,

June 2014 saw the completion of an £8 million restoration project by museum design specialist,

* Block C Visitor Centre

** Secrets Revealed introduction

** The Road to Bletchley Park. Codebreaking in World War One.

** Intel Security Cybersecurity exhibition. Online security and privacy in the 21st Century.

* Block B

** Lorenz Cipher

** Alan Turing

** Enigma machines

** Japanese codes

** Home Front exhibition. How people lived in WW2

* The Mansion

** Office of Alistair Denniston

** Library. Dressed as a World War II naval intelligence office

** The Imitation Game exhibition

** Gordon Welchman: Architect of Ultra Intelligence exhibition

* Huts 3 and 6. Codebreaking offices as they would have looked during World War II.

* Hut 8.

** Interactive exhibitions explaining codebreaking

** Alan Turing's office

** Pigeon exhibition. The use of pigeons in World War II.

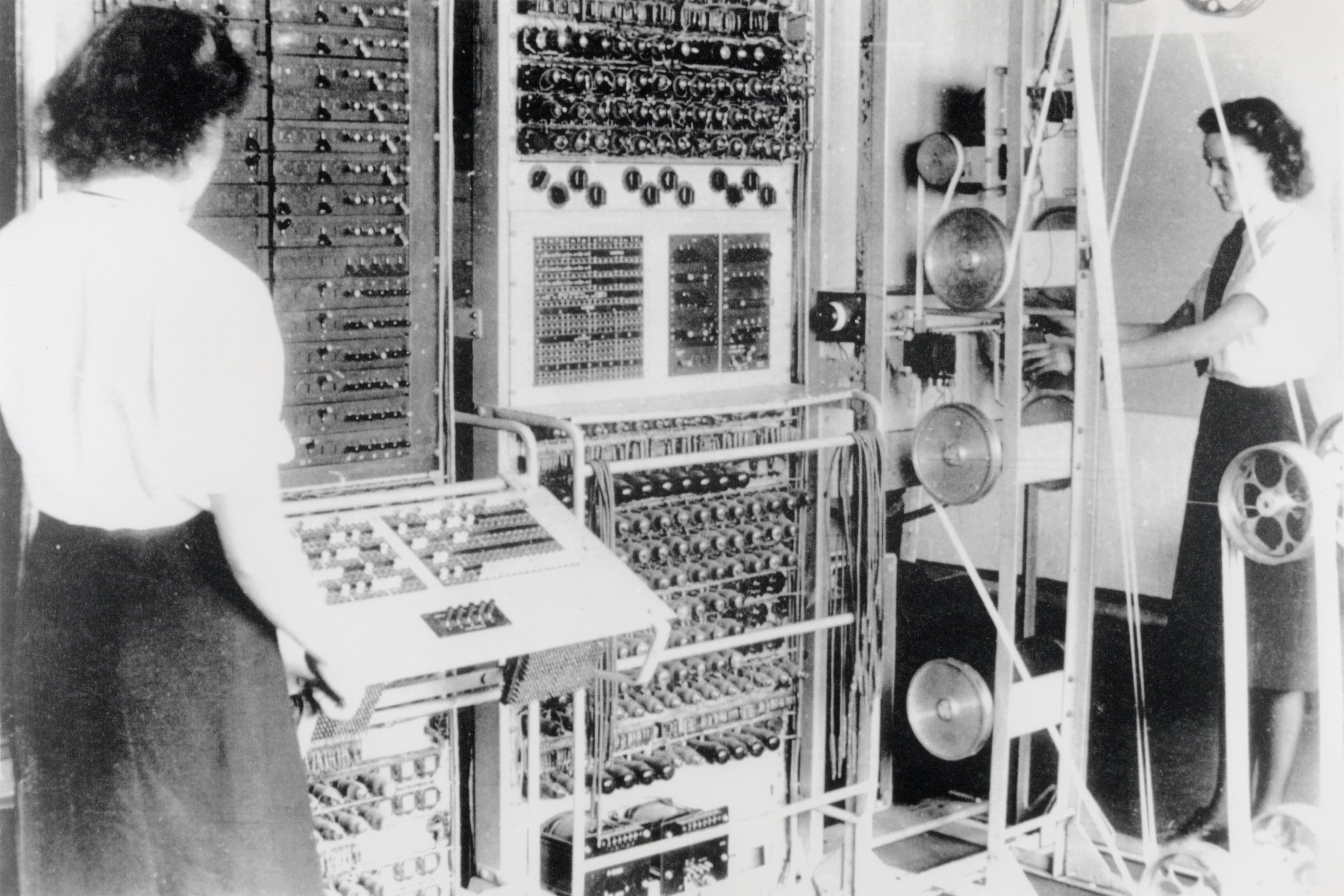

* Hut 11. Life as a WRNS Bombe operator

* Hut 12. Bletchley Park: Rescued and Restored. Items found during the restoration work.

* Wartime garages

* Hut 19. 2366 Bletchley Park Air Training Corp Squadron

* Block C Visitor Centre

** Secrets Revealed introduction

** The Road to Bletchley Park. Codebreaking in World War One.

** Intel Security Cybersecurity exhibition. Online security and privacy in the 21st Century.

* Block B

** Lorenz Cipher

** Alan Turing

** Enigma machines

** Japanese codes

** Home Front exhibition. How people lived in WW2

* The Mansion

** Office of Alistair Denniston

** Library. Dressed as a World War II naval intelligence office

** The Imitation Game exhibition

** Gordon Welchman: Architect of Ultra Intelligence exhibition

* Huts 3 and 6. Codebreaking offices as they would have looked during World War II.

* Hut 8.

** Interactive exhibitions explaining codebreaking

** Alan Turing's office

** Pigeon exhibition. The use of pigeons in World War II.

* Hut 11. Life as a WRNS Bombe operator

* Hut 12. Bletchley Park: Rescued and Restored. Items found during the restoration work.

* Wartime garages

* Hut 19. 2366 Bletchley Park Air Training Corp Squadron

The Bletchley Park Learning Department offers educational group visits with active learning activities for schools and universities. Visits can be booked in advance during term time, where students can engage with the history of Bletchley Park and understand its wider relevance for computer history and national security. Their workshops cover introductions to codebreaking, cyber security and the story of Enigma and

The Bletchley Park Learning Department offers educational group visits with active learning activities for schools and universities. Visits can be booked in advance during term time, where students can engage with the history of Bletchley Park and understand its wider relevance for computer history and national security. Their workshops cover introductions to codebreaking, cyber security and the story of Enigma and

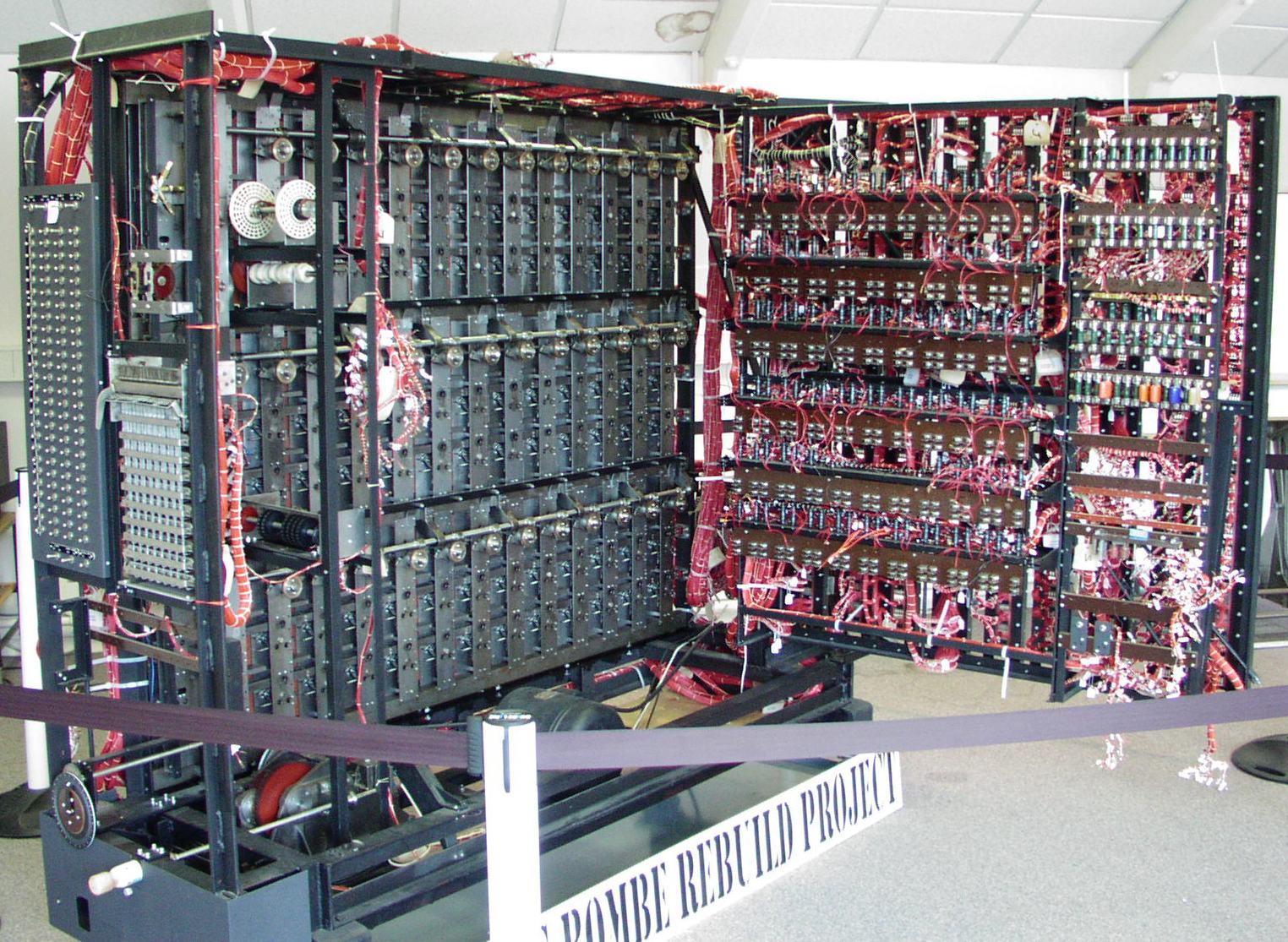

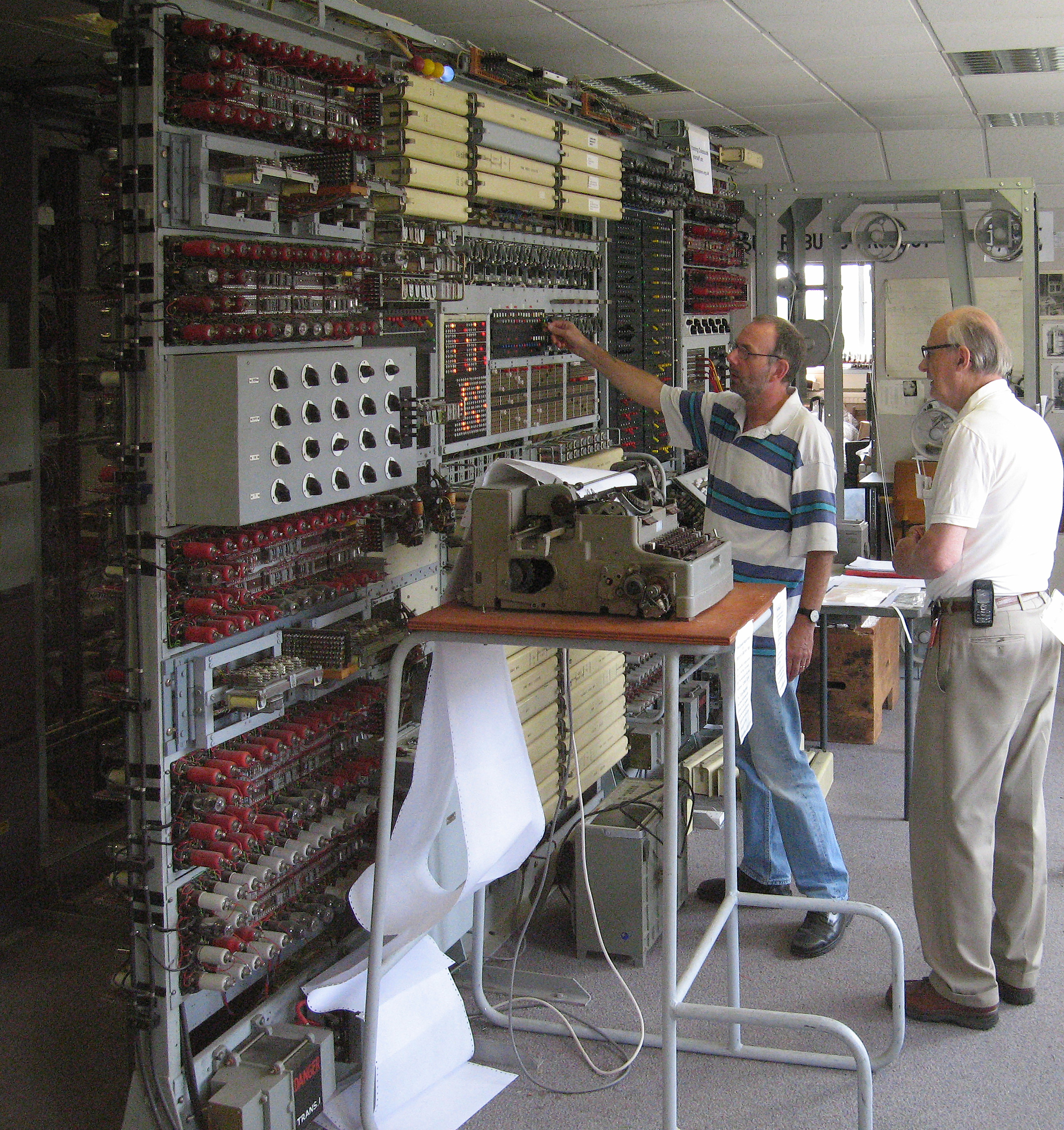

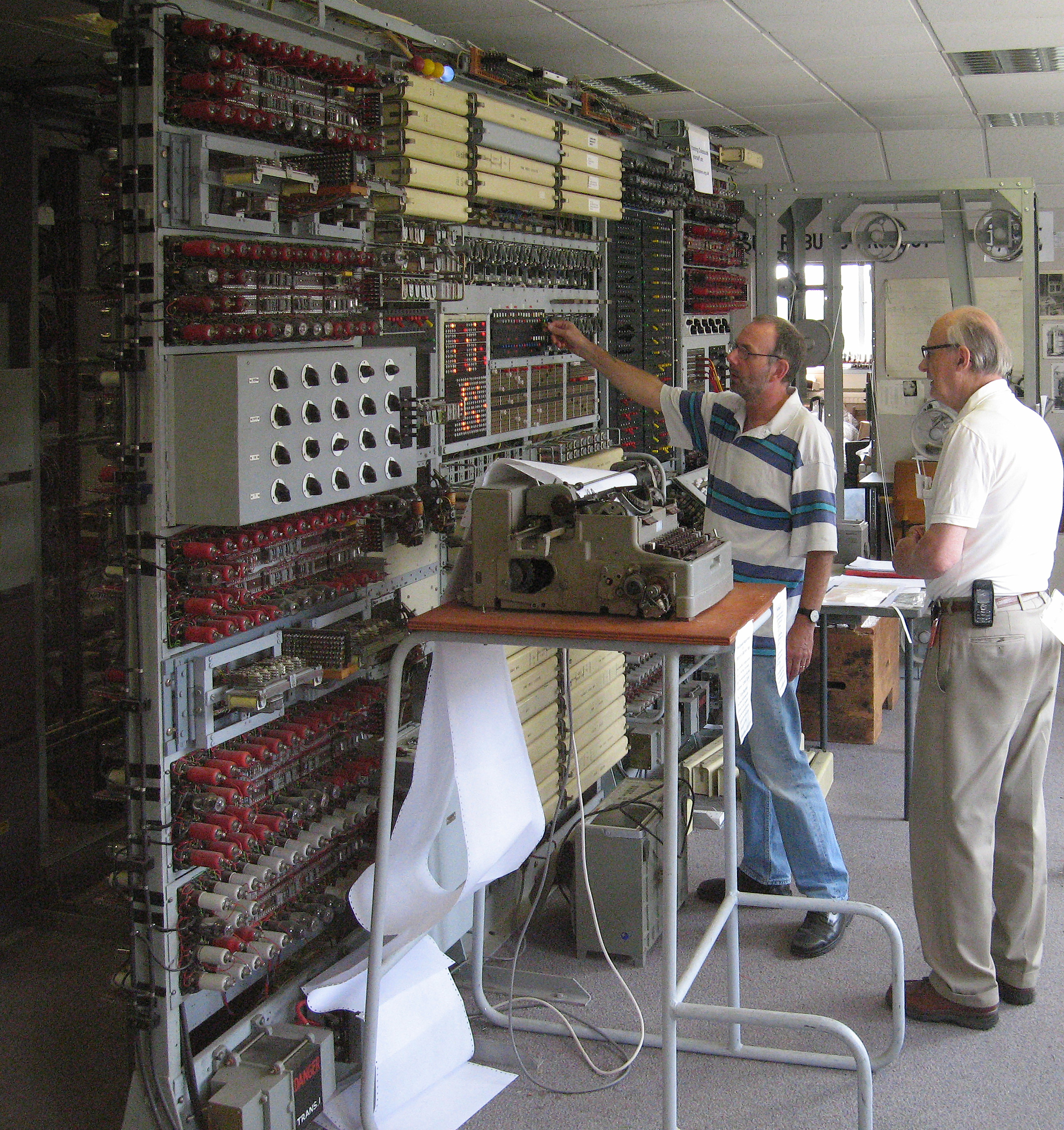

The National Museum of Computing is housed in Block H, which is rented from the Bletchley Park Trust. Its Colossus and Tunny galleries tell an important part of allied breaking of German codes during World War II. There is a working reconstruction of a Bombe and a rebuilt Colossus computer which was used on the high-level Lorenz cipher, codenamed ''Tunny'' by the British.

The museum, which opened in 2007, is an independent voluntary organisation that is governed by its own board of trustees. Its aim is "To collect and restore computer systems particularly those developed in Britain and to enable people to explore that collection for inspiration, learning and enjoyment." Through its many exhibits, the museum displays the story of computing through the mainframes of the 1960s and 1970s, and the rise of personal computing in the 1980s. It has a policy of having as many of the exhibits as possible in full working order.

The National Museum of Computing is housed in Block H, which is rented from the Bletchley Park Trust. Its Colossus and Tunny galleries tell an important part of allied breaking of German codes during World War II. There is a working reconstruction of a Bombe and a rebuilt Colossus computer which was used on the high-level Lorenz cipher, codenamed ''Tunny'' by the British.

The museum, which opened in 2007, is an independent voluntary organisation that is governed by its own board of trustees. Its aim is "To collect and restore computer systems particularly those developed in Britain and to enable people to explore that collection for inspiration, learning and enjoyment." Through its many exhibits, the museum displays the story of computing through the mainframes of the 1960s and 1970s, and the rise of personal computing in the 1980s. It has a policy of having as many of the exhibits as possible in full working order.

* The film '' Enigma'' (2001), which was based upon Robert Harris' book and starred

* The film '' Enigma'' (2001), which was based upon Robert Harris' book and starred

A Century of Mathematics in America: Part 1

; ). * Transcript of a lecture given on Tuesday 19 October 1993 at Cambridge University * * * * * * in * * * * * in * in * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * in * * in * * * in * * in * New edition with addendum by Welchman correcting his misapprehensions in the 1982 edition.

Bletchley Park Trust

*

Bletchley Park—Virtual Tour

by Tony Sale

The National Museum of Computing (based at Bletchley Park)

The RSGB National Radio Centre (based at Bletchley Park)

* (''

Boffoonery! Comedy Benefit For Bletchley Park

Comedians and computing professionals stage comedy show in aid of Bletchley Park

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20170925063249/http://www.shedblog.co.uk/2009/09/19/bletchley-park-is-the-official-charity-for-shed-week-2010-bpark-shedweek/ Bletchley Park is official charity of Shed Week 2010]—in recognition of the work done in th

Huts

Saving Bletchley Park

blog by Sue Black * with Sue Black by

C4 Station X 1999 on DVD here

How Alan Turing Cracked The Enigma Code

Imperial War Museums

The Bletchley Park Podcast

on Audioboom

Bletchley Park Paperwork at The ICL Computer Museum

{{Authority control 1993 establishments in England Biographical museums in Buckinghamshire British Telecom buildings and structures Country houses in Buckinghamshire Cryptography organizations Enigma machine Foreign Office during World War II Historic house museums in Buckinghamshire History museums in Buckinghamshire Locations in the history of espionage Military and war museums in England Milton Keynes Museums established in 1993 Museums in Buckinghamshire Signals intelligence of World War II Telecommunications museums in the United Kingdom Tourist attractions in Buckinghamshire Toy museums in England World War II museums in the United Kingdom World War II sites in England Buildings and structures in Milton Keynes

English country house

An English country house is a large house or mansion in the English countryside. Such houses were often owned by individuals who also owned a town house. This allowed them to spend time in the country and in the city—hence, for these peopl ...

and estate in Bletchley, Milton Keynes (Buckinghamshire

Buckinghamshire (), abbreviated Bucks, is a ceremonial county in South East England that borders Greater London to the south-east, Berkshire to the south, Oxfordshire to the west, Northamptonshire to the north, Bedfordshire to the north-eas ...

) that became the principal centre of Allied code-breaking during the Second World War. The mansion was constructed during the years following 1883 for the financier and politician Sir Herbert Leon

Sir Herbert Samuel Leon, 1st Baronet (11 February 1850 – 23 July 1926) was an English financier and Liberal Party politician, now best known as the main figure in the development of the Bletchley Park estate in Buckinghamshire.

Life

He was t ...

in the Victorian Gothic, Tudor, and Dutch Baroque styles, on the site of older buildings of the same name.

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, the estate housed the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS), which regularly penetrated the secret communications of the Axis Powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

most importantly the German Enigma and Lorenz

Lorenz is an originally German name derived from the Roman surname Laurentius, which means "from Laurentum".

Given name

People with the given name Lorenz include:

* Prince Lorenz of Belgium (born 1955), member of the Belgian royal family by hi ...

ciphers. The GC&CS team of codebreakers included Alan Turing

Alan Mathison Turing (; 23 June 1912 – 7 June 1954) was an English mathematician, computer scientist, logician, cryptanalyst, philosopher, and theoretical biologist. Turing was highly influential in the development of theoretical c ...

, Gordon Welchman, Hugh Alexander, Bill Tutte, and Stuart Milner-Barry. The nature of the work at Bletchley remained secret until many years after the war.

According to the official historian of British Intelligence

The Government of the United Kingdom maintains intelligence agencies within three government departments, the Foreign Office, the Home Office and the Ministry of Defence. These agencies are responsible for collecting and analysing foreign and ...

, the "Ultra

adopted by British military intelligence in June 1941 for wartime signals intelligence obtained by breaking high-level encrypted enemy radio and teleprinter communications at the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park ...

" intelligence produced at Bletchley shortened the war by two to four years, and without it the outcome of the war would have been uncertain. The team at Bletchley Park devised automatic machinery to help with decryption, culminating in the development of Colossus, the world's first programmable digital electronic computer. Codebreaking operations at Bletchley Park came to an end in 1946 and all information about the wartime operations was classified until the mid-1970s.

After the war it had various uses including as a teacher-training college and local GPO headquarters. By 1990 the huts in which the codebreakers worked were being considered for demolition and redevelopment. The Bletchley Park Trust was formed in February 1992 to save large portions of the site from development.

More recently, Bletchley Park has been open to the public, featuring interpretive exhibits and huts that have been rebuilt to appear as they did during their wartime operations. It receives hundreds of thousands of visitors annually. The separate National Museum of Computing, which includes a working replica Bombe machine and a rebuilt Colossus computer, is housed in Block H on the site.

History

The site appears in theDomesday Book

Domesday Book () – the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book" – is a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 by order of King William I, known as William the Conqueror. The manusc ...

of 1086 as part of the Manor of Eaton. Browne Willis built a mansion there in 1711, but after Thomas Harrison purchased the property in 1793 this was pulled down. It was first known as Bletchley Park after its purchase by the architect Samuel Lipscomb Seckham in 1877, who built a house there. The estate of was bought in 1883 by Sir Herbert Samuel Leon

Sir Herbert Samuel Leon, 1st Baronet (11 February 1850 – 23 July 1926) was an English financier and Liberal Party politician, now best known as the main figure in the development of the Bletchley Park estate in Buckinghamshire.

Life

He was ...

, who expanded the then-existing house into what architect Landis Gores called a "maudlin and monstrous pile" combining Victorian Gothic, Tudor, and Dutch Baroque styles. At his Christmas family gatherings there was a fox hunting

Fox hunting is an activity involving the tracking, chase and, if caught, the killing of a fox, traditionally a red fox, by trained foxhounds or other scent hounds. A group of unarmed followers, led by a "master of foxhounds" (or "master of h ...

meet on Boxing Day with glasses of sloe gin from the butler, and the house was always "humming with servants". With 40 gardeners, a flower bed of yellow daffodil

''Narcissus'' is a genus of predominantly spring flowering perennial plants of the amaryllis family, Amaryllidaceae. Various common names including daffodil,The word "daffodil" is also applied to related genera such as ''Sternbergia'', '' I ...

s could become a sea of red tulip

Tulips (''Tulipa'') are a genus of spring-blooming perennial herbaceous bulbiferous geophytes (having bulbs as storage organs). The flowers are usually large, showy and brightly coloured, generally red, pink, yellow, or white (usually in war ...

s overnight. After the death of Herbert Leon in 1926, the estate continued to be occupied by his widow Fanny Leon (née Higham) until her death in 1937.

In 1938, the mansion and much of the site was bought by a builder for a housing estate, but in May 1938 Admiral Sir Hugh Sinclair, head of the Secret Intelligence Service

The Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), commonly known as MI6 ( Military Intelligence, Section 6), is the foreign intelligence service of the United Kingdom, tasked mainly with the covert overseas collection and analysis of human intellige ...

(SIS or MI6), bought the mansion and of land for £6,000 (£ today) for use by GC&CS and SIS in the event of war. He used his own money as the Government said they did not have the budget to do so.

A key advantage seen by Sinclair and his colleagues (inspecting the site under the cover of "Captain Ridley's shooting party") was Bletchley's geographical centrality. It was almost immediately adjacent to Bletchley railway station, where the " Varsity Line" between Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the Un ...

and Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge beca ...

whose universities were expected to supply many of the code-breakersmet the main West Coast railway line connecting London, Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

, Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of City of Salford, Salford to ...

, Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

, Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated pop ...

and Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

. Watling Street

Watling Street is a historic route in England that crosses the River Thames at London and which was used in Classical Antiquity, Late Antiquity, and throughout the Middle Ages. It was used by the ancient Britons and paved as one of the main ...

, the main road linking London to the north-west (subsequently the A5) was close by, and high-volume communication links were available at the telegraph and telephone repeater station in nearby Fenny Stratford.

Bletchley Park was known as "B.P." to those who worked there.

" Station X" (X = Roman numeral

Roman numerals are a numeral system that originated in ancient Rome and remained the usual way of writing numbers throughout Europe well into the Late Middle Ages. Numbers are written with combinations of letters from the Latin alphabet, eac ...

ten), "London Signals Intelligence Centre", and "Government Communications Headquarters

Government Communications Headquarters, commonly known as GCHQ, is an intelligence and security organisation responsible for providing signals intelligence (SIGINT) and information assurance (IA) to the government and armed forces of the ...

" were all cover names used during the war.

The formal posting of the many "Wrens"members of the Women's Royal Naval Serviceworking there, was to HMS Pembroke V

RAF Eastcote, also known over time as RAF Lime Grove, HMS ''Pembroke V'' and Outstation Eastcote, was a UK Ministry of Defence (United Kingdom), Ministry of Defence site in Eastcote, Middlesex.

The British government first used the site during ...

. Royal Air Force names of Bletchley Park and its outstations included RAF Eastcote, RAF Lime Grove and RAF Church Green. The postal address that staff had to use was "Room 47, Foreign Office".

After the war, the Government Code & Cypher School became the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), moving to Eastcote in 1946 and to Cheltenham in the 1950s. The site was used by various government agencies, including the GPO and the Civil Aviation Authority

A civil aviation authority (CAA) is a national or supranational statutory authority that oversees the regulation of civil aviation, including the maintenance of an aircraft register.

Role

Due to the inherent dangers in the use of flight vehicles ...

. One large building, block F, was demolished in 1987 by which time the site was being run down with tenants leaving.

In 1990 the site was at risk of being sold for housing development. However, Milton Keynes Council made it into a conservation area. Bletchley Park Trust was set up in 1991 by a group of people who recognised the site's importance. The initial trustees included Roger Bristow, Ted Enever, Peter Wescombe, Dr Peter Jarvis of the Bletchley Archaeological & Historical Society, and Tony Sale who in 1994 became the first director of the Bletchley Park Museums.

Personnel

Admiral Hugh Sinclair was the founder and head of GC&CS between 1919 and 1938 with Commander Alastair Denniston being operational head of the organization from 1919 to 1942, beginning with its formation from the Admiralty's Room 40 (NID25) and the

Admiral Hugh Sinclair was the founder and head of GC&CS between 1919 and 1938 with Commander Alastair Denniston being operational head of the organization from 1919 to 1942, beginning with its formation from the Admiralty's Room 40 (NID25) and the War Office

The War Office was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, when its functions were transferred to the new Ministry of Defence (United Kingdom), Ministry of Defence (MoD ...

's MI1b. Key GC&CS cryptanalysts who moved from London to Bletchley Park included John Tiltman, Dillwyn "Dilly" Knox, Josh Cooper, Oliver Strachey and Nigel de Grey. These people had a variety of backgroundslinguists and chess champions were common, and Knox's field was papyrology

Papyrology is the study of manuscripts of ancient literature, correspondence, legal archives, etc., preserved on portable media from antiquity, the most common form of which is papyrus, the principal writing material in the ancient civilizations ...

. The British War Office recruited top solvers of cryptic crossword puzzles, as these individuals had strong lateral thinking skills.

On the day Britain declared war on Germany, Denniston wrote to the Foreign Office

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* United S ...

about recruiting "men of the professor type". Personal networking drove early recruitments, particularly of men from the universities of Cambridge and Oxford. Trustworthy women were similarly recruited for administrative and clerical jobs. In one 1941 recruiting stratagem, ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was f ...

'' was asked to organise a crossword competition, after which promising contestants were discreetly approached about "a particular type of work as a contribution to the war effort".

Denniston recognised, however, that the enemy's use of electromechanical cipher machines meant that formally trained mathematicians would also be needed; Oxford's Peter Twinn joined GC&CS in February 1939; Cambridge's Alan Turing

Alan Mathison Turing (; 23 June 1912 – 7 June 1954) was an English mathematician, computer scientist, logician, cryptanalyst, philosopher, and theoretical biologist. Turing was highly influential in the development of theoretical c ...

and Gordon Welchman began training in 1938 and reported to Bletchley the day after war was declared, along with John Jeffreys. Later-recruited cryptanalysts included the mathematicians Derek Taunt

Derek Roy Taunt (16 November 1917 (Note 1) – 15 July 2004) was a British mathematician who worked as a codebreaker during World War II at Bletchley Park.

Taunt attended Enfield Grammar, then the City of London School. He studied mathe ...

, Jack Good, Bill Tutte, and Max Newman

Maxwell Herman Alexander Newman, FRS, (7 February 1897 – 22 February 1984), generally known as Max Newman, was a British mathematician and codebreaker. His work in World War II led to the construction of Colossus, the world's first operatio ...

; historian Harry Hinsley, and chess champions Hugh Alexander and Stuart Milner-Barry. Joan Clarke was one of the few women employed at Bletchley as a full-fledged cryptanalyst.

When seeking to recruit more suitably advanced linguists, John Tiltman turned to Patrick Wilkinson

Patrick Wilkinson (born May 19, 1999) is an American professional soccer player who plays for the Saint Louis Billikens.

Career

Wilkinson signed with United Soccer League side Swope Park Rangers on August 18, 2016. He made his debut on August ...

of the Italian section for advice, and he suggested asking Lord Lindsay of Birker

Alexander Dunlop Lindsay, 1st Baron Lindsay of Birker (14 May 1879 - 18 March 1952),

known as Sandie Lindsay, ...

, of Balliol College, Oxford, S. W. Grose, and Martin Charlesworth, of known as Sandie Lindsay, ...

St John's College, Cambridge

St John's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge founded by the Tudor matriarch Lady Margaret Beaufort. In constitutional terms, the college is a charitable corporation established by a charter dated 9 April 1511. Th ...

, to recommend classical scholars or applicants to their colleges.

This eclectic staff of " Boffins and Debs" (scientists and debutantes, young women of high society) caused GC&CS to be whimsically dubbed the "Golf, Cheese and Chess Society".

During a September 1941 morale-boosting visit, Winston Churchill reportedly remarked to Denniston: "I told you to leave no stone unturned to get staff, but I had no idea you had taken me so literally." Six weeks later, having failed to get sufficient typing and unskilled staff to achieve the productivity that was possible, Turing, Welchman, Alexander and Milner-Barry wrote directly to Churchill. His response was "Action this day make sure they have all they want on extreme priority and report to me that this has been done." The Army CIGS Alan Brooke wrote that on 16 April 1942 "Took lunch in car and went to see the organization for breaking down ciphers – a wonderful set of professors and genii! I marvel at the work they succeed in doing."

After initial training at the Inter-Service Special Intelligence School set up by John Tiltman (initially at an RAF depot in Buckingham and later in Bedford

Bedford is a market town in Bedfordshire, England. At the 2011 Census, the population of the Bedford built-up area (including Biddenham and Kempston) was 106,940, making it the second-largest settlement in Bedfordshire, behind Luton, whilst ...

where it was known locally as "the Spy School") staff worked a six-day week, rotating through three shifts: 4p.m. to midnight, midnight to 8a.m. (the most disliked shift), and 8a.m. to 4p.m., each with a half-hour meal break. At the end of the third week, a worker went off at 8a.m. and came back at 4p.m., thus putting in 16 hours on that last day. The irregular hours affected workers' health and social life, as well as the routines of the nearby homes at which most staff lodged. The work was tedious and demanded intense concentration; staff got one week's leave four times a year, but some "girls" collapsed and required extended rest. Recruitment took place to combat a shortage of experts in Morse code and German.

In January 1945, at the peak of codebreaking efforts, nearly 10,000 personnel were working at Bletchley and its outstations. About three-quarters of these were women. Many of the women came from middle-class backgrounds and held degrees in the areas of mathematics, physics and engineering; they were given chance due to the lack of men, who had been sent to war. They performed calculations and coding and hence were integral to the computing processes. Among them were Eleanor Ireland

Eleanor D. L. Ireland (née Outlaw, born 7 August 1926) was an early British computer scientist and member of the Women's Royal Naval Service.

Early life

Eleanor Ireland was born on 7 August 1926 in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire, England.Copeland, ...

who worked on the Colossus computers and Ruth Briggs, a German scholar, who worked within the Naval Section.

The female staff in Dilwyn Knox's section were sometimes termed "Dilly's Fillies". Knox's methods enabled Mavis Lever

Mavis Lilian Batey, MBE (née Lever; 5 May 1921 – 12 November 2013), was a British code-breaker during World War II. She was one of the leading female codebreakers at Bletchley Park.

She later became a historian of gardening who campaigne ...

(who married mathematician and fellow code-breaker Keith Batey) and Margaret Rock

Margaret Rock (7 July 1903 – 26 August 1983) was one of the 8000 women mathematicians who worked in Bletchley Park during World War II. With her maths skills and education, Rock was able to decode the Enigma Machine against the German Army. H ...

to solve a German code, the Abwehr

The ''Abwehr'' ( German for ''resistance'' or ''defence'', but the word usually means ''counterintelligence'' in a military context; ) was the German military-intelligence service for the '' Reichswehr'' and the ''Wehrmacht'' from 1920 to 1944. ...

cipher.

Many of the women had backgrounds in languages, particularly French, German and Italian. Among them were Rozanne Colchester

Rozanne Felicity Hastings Colchester (née Medhurst, 10 November 1922 – 17 November 2016) worked in British intelligence in the 1940s.

Early life

She met Mussolini and Hitler before the Second World War.

Career

In 1941 she joined Bletchley ...

, a translator who worked mainly for the Italian air forces Section, and Cicely Mayhew, recruited straight from university, who worked in Hut 8, translating decoded German Navy signals.

For a long time, the British Government failed to acknowledge the contributions the personnel at Bletchley Park had made. Their work achieved official recognition only in 2009.

Secrecy

Properly used, the German Enigma and Lorenz ciphers should have been virtually unbreakable, but flaws in German cryptographic procedures, and poor discipline among the personnel carrying them out, created vulnerabilities that made Bletchley's attacks just barely feasible. These vulnerabilities, however, could have been remedied by relatively simple improvements in enemy procedures, and such changes would certainly have been implemented had Germany had any hint of Bletchley's success. Thus the intelligence Bletchley produced was considered wartime Britain's "Ultra

adopted by British military intelligence in June 1941 for wartime signals intelligence obtained by breaking high-level encrypted enemy radio and teleprinter communications at the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park ...

secret"higher even than the normally highest classification and security was paramount.

All staff signed the Official Secrets Act (1939) and a 1942 security warning emphasised the importance of discretion even within Bletchley itself: "Do not talk at meals. Do not talk in the transport. Do not talk travelling. Do not talk in the billet. Do not talk by your own fireside. Be careful even in your Hut..."

Nevertheless, there were security leaks. Jock Colville, the Assistant Private Secretary to Winston Churchill, recorded in his diary on 31 July 1941, that the newspaper proprietor Lord Camrose had discovered Ultra and that security leaks "increase in number and seriousness". Without doubt, the most serious of these was that Bletchley Park had been infiltrated by John Cairncross, the notorious Soviet mole and member of the Cambridge Spy Ring, who leaked Ultra material to Moscow.

Despite the high degree of secrecy surrounding Bletchley Park during the Second World War, unique and hitherto unknown amateur film footage of the outstation at nearby Whaddon Hall came to light in 2020, after being anonymously donated to the Bletchley Park Trust. A spokesman for the Trust noted the film's existence was all the more incredible because it was "very, very rare even to have still photographs" of the park and its associated sites.

Early work

The first personnel of the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) moved to Bletchley Park on 15 August 1939. The Naval, Military, and Air Sections were on the ground floor of the mansion, together with a telephone exchange, teleprinter room, kitchen, and dining room; the top floor was allocated to MI6. Construction of the wooden huts began in late 1939, and Elmers School, a neighbouring boys' boarding school in a Victorian Gothic redbrick building by a church, was acquired for the Commercial and Diplomatic Sections.

After the

The first personnel of the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) moved to Bletchley Park on 15 August 1939. The Naval, Military, and Air Sections were on the ground floor of the mansion, together with a telephone exchange, teleprinter room, kitchen, and dining room; the top floor was allocated to MI6. Construction of the wooden huts began in late 1939, and Elmers School, a neighbouring boys' boarding school in a Victorian Gothic redbrick building by a church, was acquired for the Commercial and Diplomatic Sections.

After the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

joined World War II, a number of American cryptographer

Cryptography, or cryptology (from grc, , translit=kryptós "hidden, secret"; and ''graphein'', "to write", or '' -logia'', "study", respectively), is the practice and study of techniques for secure communication in the presence of adv ...

s were posted to Hut 3, and from May 1943 onwards there was close co-operation between British and American intelligence. (See 1943 BRUSA Agreement

The 1943 BRUSA Agreements (Britain–United States of America agreement) Ralph Erskine, ' Birch, Francis Lyall (1889–1956)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 was an agreement between the British and US ...

.) In contrast, the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

was never officially told of Bletchley Park and its activities a reflection of Churchill's distrust of the Soviets even during the US-UK-USSR alliance imposed by the Nazi threat.

The only direct enemy damage to the site was done 2021 November 1940 by three bombs probably intended for Bletchley railway station; Hut4, shifted two feet off its foundation, was winched back into place as

work inside continued.

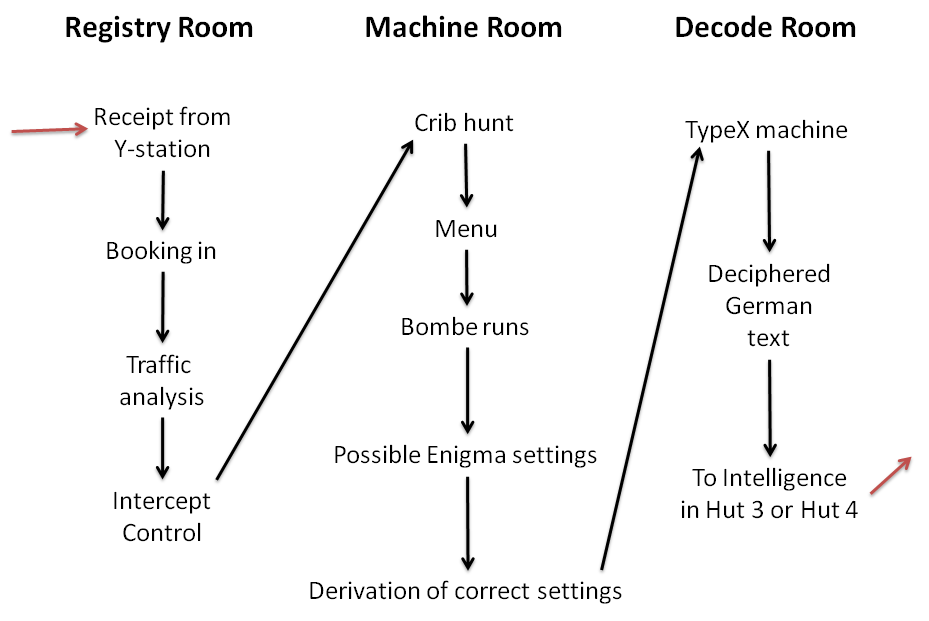

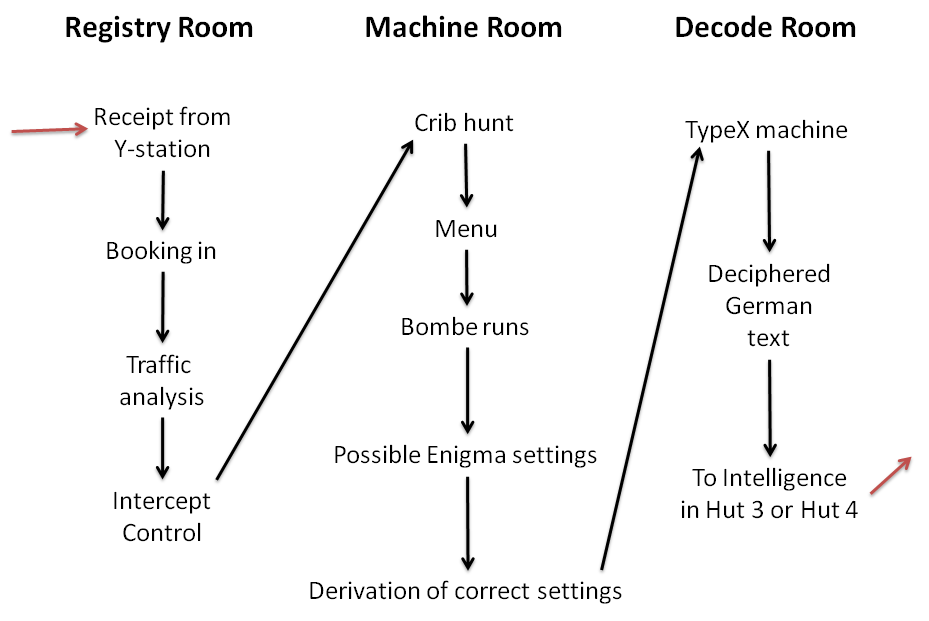

Intelligence reporting

Initially, when only a very limited amount of Enigma traffic was being read, deciphered non-Naval Enigma messages were sent from Hut 6 to Hut 3 which handled their translation and onward transmission. Subsequently, under Group Captain Eric Jones, Hut 3 expanded to become the heart of Bletchley Park's intelligence effort, with input from decrypts of " Tunny" (Lorenz SZ42) traffic and many other sources. Early in 1942 it moved into Block D, but its functions were still referred to as Hut 3.

Hut 3 contained a number of sections: Air Section "3A", Military Section "3M", a small Naval Section "3N", a multi-service Research Section "3G" and a large liaison section "3L". It also housed the Traffic Analysis Section, SIXTA. An important function that allowed the synthesis of raw messages into valuable

Initially, when only a very limited amount of Enigma traffic was being read, deciphered non-Naval Enigma messages were sent from Hut 6 to Hut 3 which handled their translation and onward transmission. Subsequently, under Group Captain Eric Jones, Hut 3 expanded to become the heart of Bletchley Park's intelligence effort, with input from decrypts of " Tunny" (Lorenz SZ42) traffic and many other sources. Early in 1942 it moved into Block D, but its functions were still referred to as Hut 3.

Hut 3 contained a number of sections: Air Section "3A", Military Section "3M", a small Naval Section "3N", a multi-service Research Section "3G" and a large liaison section "3L". It also housed the Traffic Analysis Section, SIXTA. An important function that allowed the synthesis of raw messages into valuable Military intelligence

Military intelligence is a military discipline that uses information collection and analysis approaches to provide guidance and direction to assist commanders in their decisions. This aim is achieved by providing an assessment of data from ...

was the indexing and cross-referencing of information in a number of different filing systems. Intelligence reports were sent out to the Secret Intelligence Service, the intelligence chiefs in the relevant ministries, and later on to high-level commanders in the field.

Naval Enigma deciphering was in Hut 8, with translation in Hut 4. Verbatim translations were sent to the Naval Intelligence Division (NID) of the Admiralty's Operational Intelligence Centre (OIC), supplemented by information from indexes as to the meaning of technical terms and cross-references from a knowledge store of German naval technology. Where relevant to non-naval matters, they would also be passed to Hut 3. Hut 4 also decoded a manual system known as the dockyard cipher, which sometimes carried messages that were also sent on an Enigma network. Feeding these back to Hut8 provided excellent "cribs" for Known-plaintext attacks on the daily naval Enigma key.

Listening stations

Initially, awireless

Wireless communication (or just wireless, when the context allows) is the transfer of information between two or more points without the use of an electrical conductor, optical fiber or other continuous guided medium for the transfer. The mos ...

room was established at Bletchley Park.

It was set up in the mansion's water tower under the code name "Station X", a term now sometimes applied to the codebreaking efforts at Bletchley as a whole. The "X" is the Roman numeral

Roman numerals are a numeral system that originated in ancient Rome and remained the usual way of writing numbers throughout Europe well into the Late Middle Ages. Numbers are written with combinations of letters from the Latin alphabet, eac ...

"ten", this being the Secret Intelligence Service's tenth such station. Due to the long radio aerials stretching from the wireless room, the radio station was moved from Bletchley Park to nearby Whaddon Hall to avoid drawing attention to the site.

Subsequently, other listening stationsthe Y-stations, such as the ones at Chicksands in Bedfordshire, Beaumanor Hall, Leicestershire (where the headquarters of the War Office "Y" Group was located) and Beeston Hill Y Station

Beeston Hill Y Station was a secret listening station located on the summit of Beeston Hill, Sheringham in the English county of Norfolk. The chain of Y stations were the front line of the War Office's Bletchley Park, which had the code name ...

in Norfolkgathered raw signals for processing at Bletchley. Coded messages were taken down by hand and sent to Bletchley on paper by motorcycle despatch riders or (later) by teleprinter.

Additional buildings

The wartime needs required the building of additional accommodation.Huts

Hagelin Hagelin may refer to:

* Albert Viljam Hagelin (1881–1946), Norwegian World War II collaborationist and minister

* Bobbie Hagelin (born 1984), Swedish hockey player

* Boris Hagelin (1892–1983), Swedish businessman and inventor of a cryptography ...

decrypts

* ''Hut 5'': Military intelligence including Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese ciphers and German police codes.

* '' Hut 6'': Cryptanalysis of Army and Air Force Enigma

* ''Hut 7

Hut 7 was a wartime section of the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park tasked with the solution of Japanese naval codes such as JN4, JN11, JN40, and JN-25. The hut was headed by Hugh Foss who reported to Frank Birch, the he ...

'': Cryptanalysis of Japanese naval codes

The vulnerability of Japanese naval codes and ciphers was crucial to the conduct of World War II, and had an important influence on foreign relations between Japan and the west in the years leading up to the war as well. Every Japanese code was e ...

and intelligence.

* '' Hut 8'': Cryptanalysis of Naval Enigma.

* ''Hut 9'': ISOS (Intelligence Section Oliver Strachey).

* ''Hut 10'': Secret Intelligence Service

The Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), commonly known as MI6 ( Military Intelligence, Section 6), is the foreign intelligence service of the United Kingdom, tasked mainly with the covert overseas collection and analysis of human intellige ...

(SIS or MI6) codes, Air and Meteorological sections.

* ''Hut 11'': Bombe building.

* ''Hut 14'': Communications centre.

* ''Hut 15'': SIXTA (Signals Intelligence and Traffic Analysis).

* ''Hut 16'': ISK (Intelligence Service Knox) Abwehr

The ''Abwehr'' ( German for ''resistance'' or ''defence'', but the word usually means ''counterintelligence'' in a military context; ) was the German military-intelligence service for the '' Reichswehr'' and the ''Wehrmacht'' from 1920 to 1944. ...

ciphers.

* ''Hut 18'': ISOS (Intelligence Section Oliver Strachey).

* ''Hut 23'': Primarily used to house the engineering department. After February 1943, Hut 3 was renamed Hut 23.

Blocks

In addition to the wooden huts, there were a number of brick-built "blocks". * ''Block A'': Naval Intelligence. * ''Block B'': Italian Air and Naval, and Japanese code breaking. * ''Block C'': Stored the substantial punch-card indexes. * ''Block D'': From February 1943 it housed those from Hut 3, who synthesised intelligence from multiple sources, Huts 6 and 8 and SIXTA. * ''Block E'': Incoming and outgoing Radio Transmission and TypeX. * ''Block F'': Included the Newmanry and Testery, and Japanese Military Air Section. It has since been demolished. * ''Block G'': Traffic analysis and deception operations. * ''Block H'': ''Tunny'' and Colossus (now The National Museum of Computing).Work on specific countries' signals

German signals

Most German messages decrypted at Bletchley were produced by one or another version of the Enigma cipher machine, but an important minority were produced by the even more complicated twelve-rotor Lorenz SZ42 on-line teleprinter cipher machine.

Five weeks before the outbreak of war, Warsaw's Cipher Bureau revealed its achievements in breaking Enigma to astonished French and British personnel. The British used the Poles' information and techniques, and the Enigma clone sent to them in August 1939, which greatly increased their (previously very limited) success in decrypting Enigma messages.

Most German messages decrypted at Bletchley were produced by one or another version of the Enigma cipher machine, but an important minority were produced by the even more complicated twelve-rotor Lorenz SZ42 on-line teleprinter cipher machine.

Five weeks before the outbreak of war, Warsaw's Cipher Bureau revealed its achievements in breaking Enigma to astonished French and British personnel. The British used the Poles' information and techniques, and the Enigma clone sent to them in August 1939, which greatly increased their (previously very limited) success in decrypting Enigma messages.

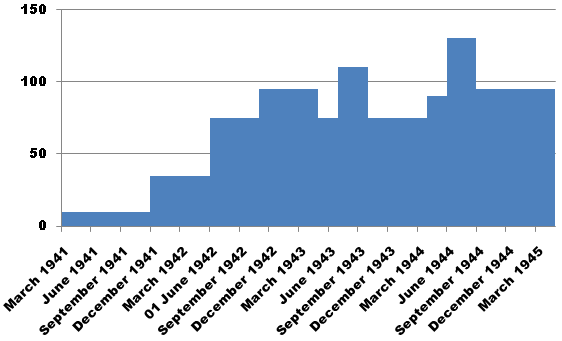

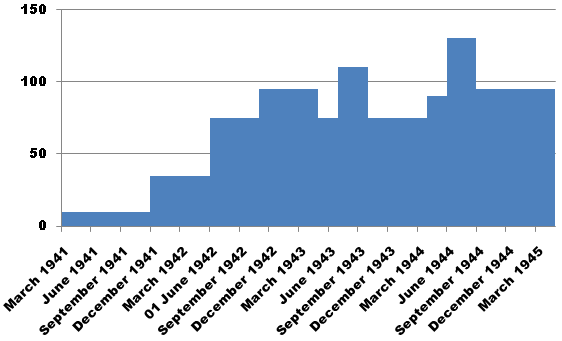

The bombe was an electromechanical device whose function was to discover some of the daily settings of the Enigma machines on the various German military networks. Its pioneering design was developed by

The bombe was an electromechanical device whose function was to discover some of the daily settings of the Enigma machines on the various German military networks. Its pioneering design was developed by Alan Turing

Alan Mathison Turing (; 23 June 1912 – 7 June 1954) was an English mathematician, computer scientist, logician, cryptanalyst, philosopher, and theoretical biologist. Turing was highly influential in the development of theoretical c ...

(with an important contribution from Gordon Welchman) and the machine was engineered by Harold 'Doc' Keen

Harold Hall "Doc" Keen (1894–1973) was a British engineer who produced the engineering design, and oversaw the construction of, the British bombe, a codebreaking machine used in World War II to read German messages sent using the Enigma machin ...

of the British Tabulating Machine Company. Each machine was about high and wide, deep and weighed about a ton.

At its peak, GC&CS was reading approximately 4,000 messages per day. As a hedge against enemy attack most bombes were dispersed to installations at Adstock

''For the municipality in Quebec, see Adstock, Quebec''

Adstock is a village and civil parish about northwest of Winslow and southeast of Buckingham in the Aylesbury Vale district of Buckinghamshire. The 2001 Census recorded a parish populatio ...

and Wavendon (both later supplanted by installations at Stanmore

Stanmore is part of the London Borough of Harrow in London. It is centred northwest of Charing Cross, lies on the outskirts of the London urban area and includes Stanmore Hill, one of the highest points of London, at high. The district, whi ...

and Eastcote), and Gayhurst

Gayhurst is a village and civil parish in the unitary authority area of the City of Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire, England. It is about two and a half miles NNW of Newport Pagnell.

The village name is an Old English language word meanin ...

.

Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German '' Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the '' Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabt ...

messages were the first to be read in quantity. The German navy had much tighter procedures, and the capture of code books was needed before they could be broken. When, in February 1942, the German navy introduced the four-rotor Enigma for communications with its Atlantic U-boats, this traffic became unreadable for a period of ten months. Britain produced modified bombes, but it was the success of the US Navy Bombe

The bombe () was an Electromechanics, electro-mechanical device used by British cryptologists to help decipher German Enigma machine, Enigma-machine-encrypted secret messages during World War II. The United States Navy, US Navy and United Sta ...

that was the main source of reading messages from this version of Enigma for the rest of the war. Messages were sent to and fro across the Atlantic by enciphered teleprinter links.

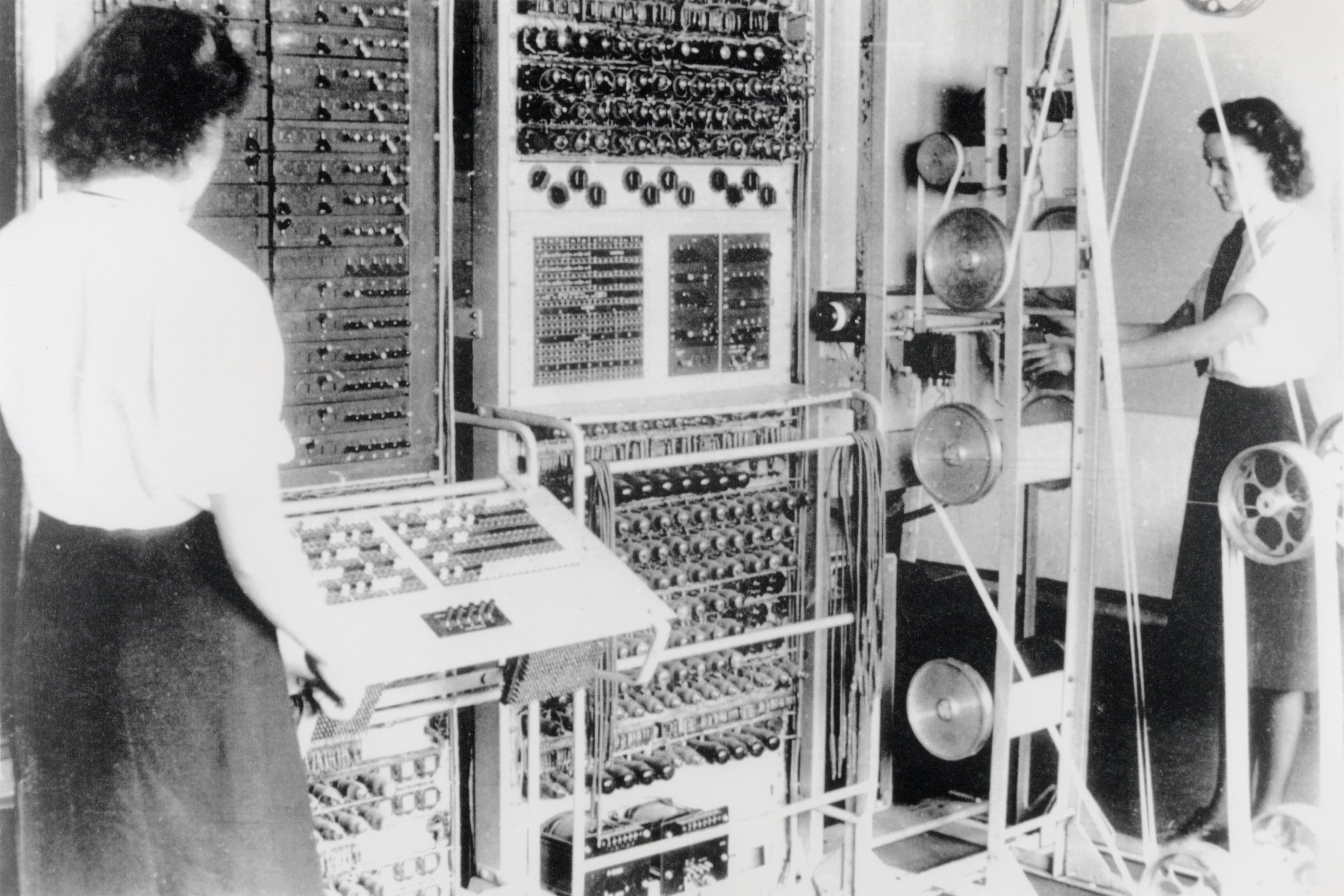

The Lorenz messages were codenamed ''Tunny'' at Bletchley Park. They were only sent in quantity from mid-1942. The Tunny networks were used for high-level messages between German High Command and field commanders. With the help of German operator errors, the cryptanalysts in the Testery (named after

The Lorenz messages were codenamed ''Tunny'' at Bletchley Park. They were only sent in quantity from mid-1942. The Tunny networks were used for high-level messages between German High Command and field commanders. With the help of German operator errors, the cryptanalysts in the Testery (named after Ralph Tester

Ralph Paterson Tester (2 June 1902 – May 1998) was an administrator at Bletchley Park, the British codebreaking station during World War II. He founded and supervised a section named the '' Testery'' for breaking Tunny (a Fish cipher).

Back ...

, its head) worked out the logical structure of the machine despite not knowing its physical form. They devised automatic machinery to help with decryption, which culminated in Colossus, the world's first programmable digital electronic computer. This was designed and built by Tommy Flowers

Thomas Harold Flowers MBE (22 December 1905 – 28 October 1998) was an English engineer with the British General Post Office. During World War II, Flowers designed and built Colossus, the world's first programmable electronic computer, to hel ...

and his team at the Post Office Research Station at Dollis Hill. The prototype first worked in December 1943, was delivered to Bletchley Park in January and first worked operationally on 5 February 1944. Enhancements were developed for the Mark 2 Colossus, the first of which was working at Bletchley Park on the morning of 1 June in time for D-day. Flowers then produced one Colossus a month for the rest of the war, making a total of ten with an eleventh part-built. The machines were operated mainly by Wrens in a section named the Newmanry after its head Max Newman

Maxwell Herman Alexander Newman, FRS, (7 February 1897 – 22 February 1984), generally known as Max Newman, was a British mathematician and codebreaker. His work in World War II led to the construction of Colossus, the world's first operatio ...

.

Bletchley's work was essential to defeating the U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare ro ...

s in the Battle of the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic, the longest continuous military campaign in World War II, ran from 1939 to the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, covering a major part of the naval history of World War II. At its core was the Allied naval blocka ...

, and to the British naval victories in the Battle of Cape Matapan and the Battle of North Cape. In 1941, Ultra exerted a powerful effect on the North African desert campaign against German forces under General Erwin Rommel. General Sir Claude Auchinleck

Field Marshal Sir Claude John Eyre Auchinleck, (21 June 1884 – 23 March 1981), was a British Army commander during the Second World War. He was a career soldier who spent much of his military career in India, where he rose to become Command ...

wrote that were it not for Ultra, "Rommel would have certainly got through to Cairo". While not changing the events, "Ultra

adopted by British military intelligence in June 1941 for wartime signals intelligence obtained by breaking high-level encrypted enemy radio and teleprinter communications at the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park ...

" decrypts featured prominently in the story of Operation SALAM, László Almásy's mission across the desert behind Allied lines in 1942. Prior to the Normandy landings

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on Tuesday, 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during World War II. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as ...

on D-Day in June 1944, the Allies knew the locations of all but two of Germany's fifty-eight Western-front divisions.

Italian signals

Italian signals had been of interest since Italy's attack on Abyssinia in 1935. During theSpanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlism, Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebeli ...

the Italian Navy used the K model of the commercial Enigma without a plugboard; this was solved by Knox in 1937.

When Italy entered the war in 1940 an improved version of the machine was used, though little traffic was sent by it and there were "wholesale changes" in Italian codes and cyphers.

Knox was given a new section for work on Enigma variations, which he staffed with women ("Dilly's girls"), who included Margaret Rock

Margaret Rock (7 July 1903 – 26 August 1983) was one of the 8000 women mathematicians who worked in Bletchley Park during World War II. With her maths skills and education, Rock was able to decode the Enigma Machine against the German Army. H ...

, Jean Perrin, Clare Harding, Rachel Ronald, Elisabeth Granger; and Mavis Lever

Mavis Lilian Batey, MBE (née Lever; 5 May 1921 – 12 November 2013), was a British code-breaker during World War II. She was one of the leading female codebreakers at Bletchley Park.

She later became a historian of gardening who campaigne ...

.

Mavis Lever solved the signals revealing the Italian Navy's operational plans before the Battle of Cape Matapan in 1941, leading to a British victory. in

Although most Bletchley staff did not know the results of their work, Admiral Cunningham visited Bletchley in person a few weeks later to congratulate them.

On entering World War II in June 1940, the Italians

, flag =

, flag_caption = Flag of Italy, The national flag of Italy

, population =

, regions = Italy 55,551,000

, region1 = Brazil

, pop1 = 25–33 million

, ref1 =

, ...

were using book codes for most of their military messages. The exception was the Italian Navy, which after the Battle of Cape Matapan started using the C-38 version of the Boris Hagelin

Boris Caesar Wilhelm Hagelin (2 July 1892 – 7 September 1983) was a Swedish businessman and inventor of encryption machines.

Biography

Born of Swedish parents in Adshikent, Russian Empire, Hagelin attended Lundsberg boarding school and late ...

rotor-based cipher machine

In cryptography, a cipher (or cypher) is an algorithm for performing encryption or decryption—a series of well-defined steps that can be followed as a procedure. An alternative, less common term is ''encipherment''. To encipher or enco ...

, particularly to route their navy and merchant marine convoys to the conflict in North Africa. As a consequence, JRM Butler recruited his former student Bernard Willson to join a team with two others in Hut4. In June 1941, Willson became the first of the team to decode the Hagelin system, thus enabling military commanders to direct the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by Kingdom of England, English and Kingdom of Scotland, Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were foug ...

and Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

to sink enemy ships carrying supplies from Europe to Rommel's Afrika Korps

The Afrika Korps or German Africa Corps (, }; DAK) was the German expeditionary force in Africa during the North African Campaign of World War II. First sent as a holding force to shore up the Italian defense of its African colonies, the ...

. This led to increased shipping losses and, from reading the intercepted traffic, the team learnt that between May and September 1941 the stock of fuel for the Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German '' Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the '' Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabt ...

in North Africa reduced by 90 percent.

After an intensive language course, in March 1944 Willson switched to Japanese language-based codes.

A Middle East Intelligence Centre (MEIC) was set up in Cairo in 1939. When Italy entered the war in June 1940, delays in forwarding intercepts to Bletchley via congested radio links resulted in cryptanalysts being sent to Cairo. A Combined Bureau Middle East (CBME) was set up in November, though the Middle East authorities made "increasingly bitter complaints" that GC&CS was giving too little priority to work on Italian cyphers. However, the principle of concentrating high-grade cryptanalysis at Bletchley was maintained. John Chadwick started cryptanalysis work in 1942 on Italian signals at the naval base 'HMS Nile' in Alexandria. Later, he was with GC&CS; in the Heliopolis Museum, Cairo and then in the Villa Laurens, Alexandria."Life of John Chadwick : 1920 - 1998 : Classical Philologist, Lexicographer and Co-decipherer of Linear B", Faculty of Classics, Cambridge University

Soviet signals

Soviet signals had been studied since the 1920s. In 193940, John Tiltman (who had worked on Russian Army traffic from 1930) set up two Russian sections at Wavendon (a country house near Bletchley) and at Sarafand in Palestine. Two Russian high-grade army and navy systems were broken early in 1940. Tiltman spent two weeks in Finland, where he obtained Russian traffic from Finland and Estonia in exchange for radio equipment. In June 1941, when the Soviet Union became an ally, Churchill ordered a halt to intelligence operations against it. In December 1941, the Russian section was closed down, but in late summer 1943 or late 1944, a small GC&CS Russian cypher section was set up in London overlooking Park Lane, then in Sloane Square.Japanese signals

An outpost of the Government Code and Cypher School had been set up in Hong Kong in 1935, the Far East Combined Bureau (FECB). The FECB naval staff moved in 1940 to Singapore, thenColombo

Colombo ( ; si, කොළඹ, translit=Koḷam̆ba, ; ta, கொழும்பு, translit=Koḻumpu, ) is the executive and judicial capital and largest city of Sri Lanka by population. According to the Brookings Institution, Colombo me ...

, Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

, then Kilindini, Mombasa

Mombasa ( ; ) is a coastal city in southeastern Kenya along the Indian Ocean. It was the first capital of the British East Africa, before Nairobi was elevated to capital city status. It now serves as the capital of Mombasa County. The town is ...

, Kenya. They succeeded in deciphering Japanese codes with a mixture of skill and good fortune. The Army and Air Force staff went from Singapore to the Wireless Experimental Centre at Delhi

Delhi, officially the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi, is a city and a union territory of India containing New Delhi, the capital of India. Straddling the Yamuna river, primarily its western or right bank, Delhi shares borders wi ...

, India.

In early 1942, a six-month crash course in Japanese, for 20 undergraduates from Oxford and Cambridge, was started by the Inter-Services Special Intelligence School in Bedford, in a building across from the main Post Office. This course was repeated every six months until war's end. Most of those completing these courses worked on decoding Japanese naval messages in Hut 7, under John Tiltman.

By mid-1945, well over 100 personnel were involved with this operation, which co-operated closely with the FECB and the US Signal intelligence Service at Arlington Hall, Virginia. In 1999, Michael Smith wrote that: "Only now are the British codebreakers (like John Tiltman, Hugh Foss, and Eric Nave) beginning to receive the recognition they deserve for breaking Japanese codes and cyphers".

Postwar

Continued secrecy

After the War, the secrecy imposed on Bletchley staff remained in force, so that most relatives never knew more than that a child, spouse, or parent had done some kind of secret war work. Churchill referred to the Bletchley staff as "the geese that laid the golden eggs and never cackled". That said, occasional mentions of the work performed at Bletchley Park slipped the censor's net and appeared in print. With the publication of F.W. Winterbotham's ''The Ultra Secret'' (1974) public discussion of Bletchley Park's work finally became possible, although even today some former staff still consider themselves bound to silence. Professor Brian Randell was researching the history of computer science in Britain in 1975-76 for a conference on the history of computing held at theLos Alamos National Laboratory

Los Alamos National Laboratory (often shortened as Los Alamos and LANL) is one of the sixteen research and development laboratories of the United States Department of Energy (DOE), located a short distance northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico, i ...

, New Mexico on 10-15 June 1976, and received permission to present a paper on wartime development of the COLOSSI at the Post Office Research Station, Dollis Hill. (In October 1975 the British Government had released a series of captioned photographs from the Public Record Office.) The interest in the “revelations” in his paper resulted in a special evening meeting when Randell and Cooombs answered further questions. Coombs later wrote that "no member of our team could ever forget the fellowship, the sense of purpose and, above all, the breathless excitement of those days". In 1977 Randell published an article "The First Electronic Computer" in several journals.

In July 2009 the British government announced that Bletchley personnel would be recognised with a commemorative badge.

Site

After the war, the site passed through a succession of hands and saw a number of uses, including as a teacher-training college and local GPO headquarters. By 1991, the site was nearly empty and the buildings were at risk of demolition for redevelopment. In February 1992, theMilton Keynes Borough Council

Milton Keynes City Council is the local authority of the City of Milton Keynes in Buckinghamshire, England. It is a unitary authority, having the powers of a non-metropolitan county and district council combined. It has both borough status a ...

declared most of the Park a conservation area, and the Bletchley Park Trust was formed to maintain the site as a museum. The site opened to visitors in 1993, and was formally inaugurated by the Duke of Kent as Chief Patron in July 1994. In 1999 the land owners, the Property Advisors to the Civil Estate

The Office of Government Commerce (OGC) was a UK Government Office established as part of HM Treasury in 2000. It was moved into the Efficiency and Reform Group of the Cabinet Office in 2010, before being closed in 2011.

Overview

A ''Review of ...

and BT, granted a lease to the Trust giving it control over most of the site.

Heritage attraction

June 2014 saw the completion of an £8 million restoration project by museum design specialist,

June 2014 saw the completion of an £8 million restoration project by museum design specialist, Event Communications

Event Communications, or Event, is one of Europe's longest-established and largest museum and visitor attraction design firms; it is headquartered in London.

History

The firm was founded in 1986 by businesswoman Celestine ("Cel") Phelan and de ...

, which was marked by a visit from Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge. The Duchess' paternal grandmother, Valerie, and Valerie's twin sister, Mary (''née'' Glassborow), both worked at Bletchley Park during the war. The twin sisters worked as Foreign Office Civilians in Hut 6, where they managed the interception of enemy and neutral diplomatic signals for decryption. Valerie married Catherine's grandfather, Captain Peter Middleton. A memorial

A memorial is an object or place which serves as a focus for the memory or the commemoration of something, usually an influential, deceased person or a historical, tragic event. Popular forms of memorials include landmark objects or works of ...

at Bletchley Park commemorates Mary and Valerie Middleton's work as code-breakers.

Exhibitions

* Block C Visitor Centre

** Secrets Revealed introduction

** The Road to Bletchley Park. Codebreaking in World War One.

** Intel Security Cybersecurity exhibition. Online security and privacy in the 21st Century.

* Block B

** Lorenz Cipher

** Alan Turing

** Enigma machines

** Japanese codes

** Home Front exhibition. How people lived in WW2

* The Mansion

** Office of Alistair Denniston

** Library. Dressed as a World War II naval intelligence office

** The Imitation Game exhibition

** Gordon Welchman: Architect of Ultra Intelligence exhibition

* Huts 3 and 6. Codebreaking offices as they would have looked during World War II.

* Hut 8.

** Interactive exhibitions explaining codebreaking

** Alan Turing's office

** Pigeon exhibition. The use of pigeons in World War II.

* Hut 11. Life as a WRNS Bombe operator

* Hut 12. Bletchley Park: Rescued and Restored. Items found during the restoration work.

* Wartime garages

* Hut 19. 2366 Bletchley Park Air Training Corp Squadron

* Block C Visitor Centre

** Secrets Revealed introduction

** The Road to Bletchley Park. Codebreaking in World War One.

** Intel Security Cybersecurity exhibition. Online security and privacy in the 21st Century.

* Block B

** Lorenz Cipher

** Alan Turing

** Enigma machines

** Japanese codes

** Home Front exhibition. How people lived in WW2

* The Mansion

** Office of Alistair Denniston

** Library. Dressed as a World War II naval intelligence office

** The Imitation Game exhibition

** Gordon Welchman: Architect of Ultra Intelligence exhibition

* Huts 3 and 6. Codebreaking offices as they would have looked during World War II.

* Hut 8.

** Interactive exhibitions explaining codebreaking

** Alan Turing's office

** Pigeon exhibition. The use of pigeons in World War II.

* Hut 11. Life as a WRNS Bombe operator

* Hut 12. Bletchley Park: Rescued and Restored. Items found during the restoration work.

* Wartime garages

* Hut 19. 2366 Bletchley Park Air Training Corp Squadron

Learning Department

The Bletchley Park Learning Department offers educational group visits with active learning activities for schools and universities. Visits can be booked in advance during term time, where students can engage with the history of Bletchley Park and understand its wider relevance for computer history and national security. Their workshops cover introductions to codebreaking, cyber security and the story of Enigma and

The Bletchley Park Learning Department offers educational group visits with active learning activities for schools and universities. Visits can be booked in advance during term time, where students can engage with the history of Bletchley Park and understand its wider relevance for computer history and national security. Their workshops cover introductions to codebreaking, cyber security and the story of Enigma and Lorenz

Lorenz is an originally German name derived from the Roman surname Laurentius, which means "from Laurentum".

Given name

People with the given name Lorenz include:

* Prince Lorenz of Belgium (born 1955), member of the Belgian royal family by hi ...

.

Funding

In October 2005, American billionaire Sidney Frank donated £500,000 to Bletchley Park Trust to fund a new Science Centre dedicated toAlan Turing

Alan Mathison Turing (; 23 June 1912 – 7 June 1954) was an English mathematician, computer scientist, logician, cryptanalyst, philosopher, and theoretical biologist. Turing was highly influential in the development of theoretical c ...

. Simon Greenish joined as Director in 2006 to lead the fund-raising effort in a post he held until 2012 when Iain Standen took over the leadership role. In July 2008, a letter to ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ...

'' from more than a hundred academics condemned the neglect of the site. In September 2008, PGP, IBM, and other technology firms announced a fund-raising campaign to repair the facility. On 6 November 2008 it was announced that English Heritage

English Heritage (officially the English Heritage Trust) is a charity that manages over 400 historic monuments, buildings and places. These include prehistoric sites, medieval castles, Roman forts and country houses.

The charity states that i ...

would donate £300,000 to help maintain the buildings at Bletchley Park, and that they were in discussions regarding the donation of a further £600,000.

In October 2011, the Bletchley Park Trust received a £4.6m Heritage Lottery Fund grant to be used "to complete the restoration of the site, and to tell its story to the highest modern standards" on the condition that £1.7m of 'match funding' is raised by the Bletchley Park Trust. Just weeks later, Google contributed £550k and by June 2012 the trust had successfully raised £2.4m to unlock the grants to restore Huts 3 and 6, as well as develop its exhibition centre in Block C.

Additional income is raised by renting Block H to the National Museum of Computing, and some office space in various parts of the park to private firms.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic, also known as the coronavirus pandemic, is an ongoing global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The novel virus was first identified ...

the Trust expected to lose more than £2m in 2020 and be required to cut a third of its workforce. Former MP John Leech asked tech giants Amazon

Amazon most often refers to:

* Amazons, a tribe of female warriors in Greek mythology

* Amazon rainforest, a rainforest covering most of the Amazon basin

* Amazon River, in South America

* Amazon (company), an American multinational technolog ...

, Apple

An apple is an edible fruit produced by an apple tree (''Malus domestica''). Apple trees are cultivated worldwide and are the most widely grown species in the genus '' Malus''. The tree originated in Central Asia, where its wild ances ...

, Google

Google LLC () is an American Multinational corporation, multinational technology company focusing on Search Engine, search engine technology, online advertising, cloud computing, software, computer software, quantum computing, e-commerce, ar ...

, Facebook

Facebook is an online social media and social networking service owned by American company Meta Platforms. Founded in 2004 by Mark Zuckerberg with fellow Harvard College students and roommates Eduardo Saverin, Andrew McCollum, Dustin ...

and Microsoft

Microsoft Corporation is an American multinational corporation, multinational technology company, technology corporation producing Software, computer software, consumer electronics, personal computers, and related services headquartered at th ...

to donate £400,000 each to secure the future of the Trust. Leech had led the successful campaign to pardon Alan Turing

Alan Mathison Turing (; 23 June 1912 – 7 June 1954) was an English mathematician, computer scientist, logician, cryptanalyst, philosopher, and theoretical biologist. Turing was highly influential in the development of theoretical c ...

and implement Turing's Law.

Other organisations sharing the campus

The National Museum of Computing

The National Museum of Computing is housed in Block H, which is rented from the Bletchley Park Trust. Its Colossus and Tunny galleries tell an important part of allied breaking of German codes during World War II. There is a working reconstruction of a Bombe and a rebuilt Colossus computer which was used on the high-level Lorenz cipher, codenamed ''Tunny'' by the British.

The museum, which opened in 2007, is an independent voluntary organisation that is governed by its own board of trustees. Its aim is "To collect and restore computer systems particularly those developed in Britain and to enable people to explore that collection for inspiration, learning and enjoyment." Through its many exhibits, the museum displays the story of computing through the mainframes of the 1960s and 1970s, and the rise of personal computing in the 1980s. It has a policy of having as many of the exhibits as possible in full working order.