Bivalves Described In 1834 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Bivalvia (), in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a

Bivalvia (), in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a

Bivalves have

Bivalves have

Bivalves have an open

Bivalves have an open

Bivalvia (), in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a

Bivalvia (), in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a class

Class or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used differentl ...

of marine and freshwater molluscs

Mollusca is the second-largest phylum of invertebrate animals after the Arthropoda, the members of which are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 85,000 extant taxon, extant species of molluscs are recognized. The number of fossil sp ...

that have laterally compressed bodies enclosed by a shell consisting of two hinged parts. As a group, bivalves have no head

A head is the part of an organism which usually includes the ears, brain, forehead, cheeks, chin, eyes, nose, and mouth, each of which aid in various sensory functions such as sight, hearing, smell, and taste. Some very simple animals may ...

and they lack some usual molluscan organs, like the radula

The radula (, ; plural radulae or radulas) is an anatomical structure used by molluscs for feeding, sometimes compared to a tongue. It is a minutely toothed, chitinous ribbon, which is typically used for scraping or cutting food before the food ...

and the odontophore

The odontophore is part of the feeding mechanism in molluscs. It is the cartilage which underlies and supports the radula, a ribbon of teeth. The radula is found in every class of molluscs except for the bivalves.

The feeding apparatus can be exte ...

. They include the clam

Clam is a common name for several kinds of bivalve molluscs. The word is often applied only to those that are edible and live as infauna, spending most of their lives halfway buried in the sand of the seafloor or riverbeds. Clams have two she ...

s, oyster

Oyster is the common name for a number of different families of salt-water bivalve molluscs that live in marine or brackish habitats. In some species, the valves are highly calcified, and many are somewhat irregular in shape. Many, but not al ...

s, cockles, mussel

Mussel () is the common name used for members of several families of bivalve molluscs, from saltwater and Freshwater bivalve, freshwater habitats. These groups have in common a shell whose outline is elongated and asymmetrical compared with other ...

s, scallop

Scallop () is a common name that encompasses various species of marine bivalve mollusks in the taxonomic family Pectinidae, the scallops. However, the common name "scallop" is also sometimes applied to species in other closely related families ...

s, and numerous other families

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Ideall ...

that live in saltwater, as well as a number of families that live in freshwater. The majority are filter feeder

Filter feeders are a sub-group of suspension feeding animals that feed by straining suspended matter and food particles from water, typically by passing the water over a specialized filtering structure. Some animals that use this method of feedin ...

s. The gill

A gill () is a respiratory organ that many aquatic organisms use to extract dissolved oxygen from water and to excrete carbon dioxide. The gills of some species, such as hermit crabs, have adapted to allow respiration on land provided they are ...

s have evolved into ctenidia, specialised organs for feeding and breathing. Most bivalves bury themselves in sediment, where they are relatively safe from predation

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill the ...

. Others lie on the sea floor or attach themselves to rocks or other hard surfaces. Some bivalves, such as the scallops and file shell

The Limidae or file shells are members of the only family of bivalve molluscs in the order Limida. The family includes 130 living species, assigned to 10 genera. Widely distributed in all seas from shallow to deep waters, the species are usually ...

s, can swim. The shipworms

The shipworms are marine bivalve molluscs in the family Teredinidae: a group of saltwater clams with long, soft, naked bodies. They are notorious for boring into (and commonly eventually destroying) wood that is immersed in sea water, including ...

bore into wood, clay, or stone and live inside these substances.

The shell

Shell may refer to:

Architecture and design

* Shell (structure), a thin structure

** Concrete shell, a thin shell of concrete, usually with no interior columns or exterior buttresses

** Thin-shell structure

Science Biology

* Seashell, a hard ou ...

of a bivalve is composed of calcium carbonate, and consists of two, usually similar, parts called valves

A valve is a device or natural object that regulates, directs or controls the flow of a fluid (gases, liquids, fluidized solids, or slurries) by opening, closing, or partially obstructing various passageways. Valves are technically fittings ...

. These are joined together along one edge (the hinge line

A hinge line is an imaginary longitudinal line along the dorsal edge of the shell of a bivalve mollusk where the two valves hinge or articulate. The hinge line can easily be perceived in these images of a mussel shell and an ark shell.Invertebrat ...

) by a flexible ligament

A ligament is the fibrous connective tissue that connects bones to other bones. It is also known as ''articular ligament'', ''articular larua'', ''fibrous ligament'', or ''true ligament''. Other ligaments in the body include the:

* Peritoneal li ...

that, usually in conjunction with interlocking "teeth" on each of the valves, forms the hinge

A hinge is a mechanical bearing that connects two solid objects, typically allowing only a limited angle of rotation between them. Two objects connected by an ideal hinge rotate relative to each other about a fixed axis of rotation: all other ...

. This arrangement allows the shell to be opened and closed without the two halves detaching. The shell is typically bilaterally symmetrical

Symmetry in biology refers to the symmetry observed in organisms, including plants, animals, fungi, and bacteria. External symmetry can be easily seen by just looking at an organism. For example, take the face of a human being which has a pla ...

, with the hinge lying in the sagittal plane

The sagittal plane (; also known as the longitudinal plane) is an anatomical plane that divides the body into right and left sections. It is perpendicular to the transverse and coronal planes. The plane may be in the center of the body and divid ...

. Adult shell sizes of bivalves vary from fractions of a millimetre to over a metre in length, but the majority of species do not exceed 10 cm (4 in).

Bivalves have long been a part of the diet of coastal and riparian

A riparian zone or riparian area is the interface between land and a river or stream. Riparian is also the proper nomenclature for one of the terrestrial biomes of the Earth. Plant habitats and communities along the river margins and banks ar ...

human populations. Oysters were cultured

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these groups.Tylor ...

in ponds by the Romans, and mariculture

Mariculture or marine farming is a specialized branch of aquaculture (which includes freshwater aquaculture) involving the cultivation of marine organisms for food and other animal products, in enclosed sections of the open ocean ( offshore mari ...

has more recently become an important source of bivalves for food. Modern knowledge of molluscan reproductive cycles has led to the development of hatcheries and new culture techniques. A better understanding of the potential hazards

A hazard is a potential source of harm. Substances, events, or circumstances can constitute hazards when their nature would allow them, even just theoretically, to cause damage to health, life, property, or any other interest of value. The probabi ...

of eating raw or undercooked shellfish

Shellfish is a colloquial and fisheries term for exoskeleton-bearing aquatic invertebrates used as food, including various species of molluscs, crustaceans, and echinoderms. Although most kinds of shellfish are harvested from saltwater envir ...

has led to improved storage and processing. Pearl oysters

A pearl is a hard, glistening object produced within the soft tissue (specifically the mantle) of a living shelled mollusk or another animal, such as fossil conulariids. Just like the shell of a mollusk, a pearl is composed of calcium carb ...

(the common name of two very different families in salt water and fresh water) are the most common source of natural pearls

A pearl is a hard, glistening object produced within the soft tissue (specifically the mantle (mollusc), mantle) of a living animal shell, shelled mollusk or another animal, such as fossil conulariids. Just like the shell of a mollusk, a pea ...

. The shells of bivalves are used in craftwork, and the manufacture of jewellery and buttons. Bivalves have also been used in the biocontrol of pollution.

Bivalves appear in the fossil record

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved in ...

first in the early Cambrian

The Cambrian Period ( ; sometimes symbolized C with bar, Ꞓ) was the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, and of the Phanerozoic Eon. The Cambrian lasted 53.4 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran Period 538.8 million ...

more than 500 million years ago. The total number of known living species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

is about 9,200. These species are placed within 1,260 genera and 106 families. Marine bivalves (including brackish water

Brackish water, sometimes termed brack water, is water occurring in a natural environment that has more salinity than freshwater, but not as much as seawater. It may result from mixing seawater (salt water) and fresh water together, as in estua ...

and estuarine

An estuary is a partially enclosed coastal body of brackish water with one or more rivers or streams flowing into it, and with a free connection to the open sea. Estuaries form a transition zone between river environments and maritime environment ...

species) represent about 8,000 species, combined in four subclasses and 99 families with 1,100 genera. The largest recent

The Holocene ( ) is the current geological epoch. It began approximately 11,650 cal years Before Present (), after the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene together ...

marine families are the Veneridae

The Veneridae or venerids, common name: Venus clams, are a very large family of minute to large, saltwater clams, marine bivalve molluscs. Over 500 living species of venerid bivalves are known, most of which are edible, and many of which are e ...

, with more than 680 species and the Tellinidae

The Tellinidae are a family of marine bivalve molluscs of the order Cardiida. Commonly known as tellins or tellens, they live fairly deep in soft sediments in shallow seas and respire using long siphons that reach up to the surface of the sedime ...

and Lucinidae

Lucinidae, common name hatchet shells, is a family of saltwater clams, marine bivalve molluscs.

These bivalves are remarkable for their endosymbiosis with sulphide-oxidizing bacteria.

Characteristics

The members of this family have a worldwide ...

, each with over 500 species. The freshwater bivalves include seven families, the largest of which are the Unionidae

The Unionidae are a family of freshwater mussels, the largest in the order Unionida, the bivalve molluscs sometimes known as river mussels, or simply as unionids.

The range of distribution for this family is world-wide. It is at its most diverse ...

, with about 700 species.

Etymology

Thetaxonomic

Taxonomy is the practice and science of categorization or classification.

A taxonomy (or taxonomical classification) is a scheme of classification, especially a hierarchical classification, in which things are organized into groups or types. ...

term Bivalvia was first used by Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the ...

in the 10th edition

1 (one, unit, unity) is a number representing a single or the only entity. 1 is also a numerical digit and represents a single unit of counting or measurement. For example, a line segment of ''unit length'' is a line segment of length 1. I ...

of his ''Systema Naturae

' (originally in Latin written ' with the ligature æ) is one of the major works of the Swedish botanist, zoologist and physician Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) and introduced the Linnaean taxonomy. Although the system, now known as binomial nomen ...

'' in 1758 to refer to animals having shells composed of two valves

A valve is a device or natural object that regulates, directs or controls the flow of a fluid (gases, liquids, fluidized solids, or slurries) by opening, closing, or partially obstructing various passageways. Valves are technically fittings ...

. More recently, the class was known as Pelecypoda, meaning "axe

An axe ( sometimes ax in American English; see spelling differences) is an implement that has been used for millennia to shape, split and cut wood, to harvest timber, as a weapon, and as a ceremonial or heraldic symbol. The axe has many for ...

-foot" (based on the shape of the foot of the animal when extended).

The name "bivalve" is derived from the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

''bis'', meaning "two", and ''valvae'', meaning "leaves of a door". ("Leaf" is an older word for the main, movable part of a door. We normally consider this the door itself.) Paired shells have evolved independently several times among animals that are not bivalves; other animals with paired valves include certain gastropod

The gastropods (), commonly known as snails and slugs, belong to a large taxonomic class of invertebrates within the phylum Mollusca called Gastropoda ().

This class comprises snails and slugs from saltwater, from freshwater, and from land. T ...

s (small sea snail

Sea snail is a common name for slow-moving marine gastropod molluscs, usually with visible external shells, such as whelk or abalone. They share the taxonomic class Gastropoda with slugs, which are distinguished from snails primarily by the ...

s in the family Juliidae

Juliidae, common name the bivalved gastropods, is a family of minute sea snails, marine gastropod mollusks or micromollusks in the superfamily Oxynooidea, an opisthobranch group. MolluscaBase eds. (2021). MolluscaBase. Juliidae E. A. Smith, 188 ...

), members of the phylum Brachiopoda and the minute crustaceans known as ostracods

Ostracods, or ostracodes, are a class of the Crustacea (class Ostracoda), sometimes known as seed shrimp. Some 70,000 species (only 13,000 of which are extant) have been identified, grouped into several orders. They are small crustaceans, typical ...

and conchostrachans.

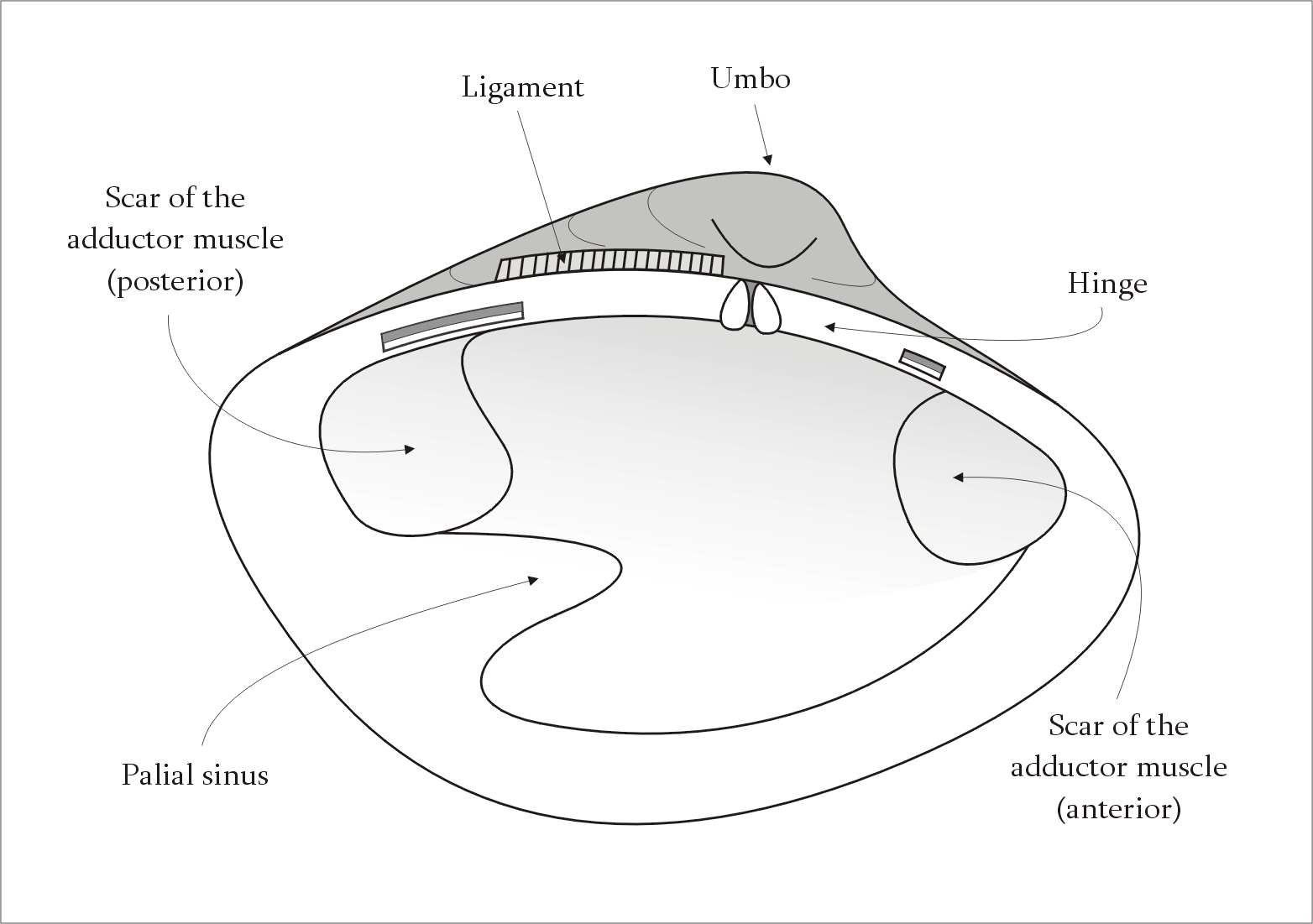

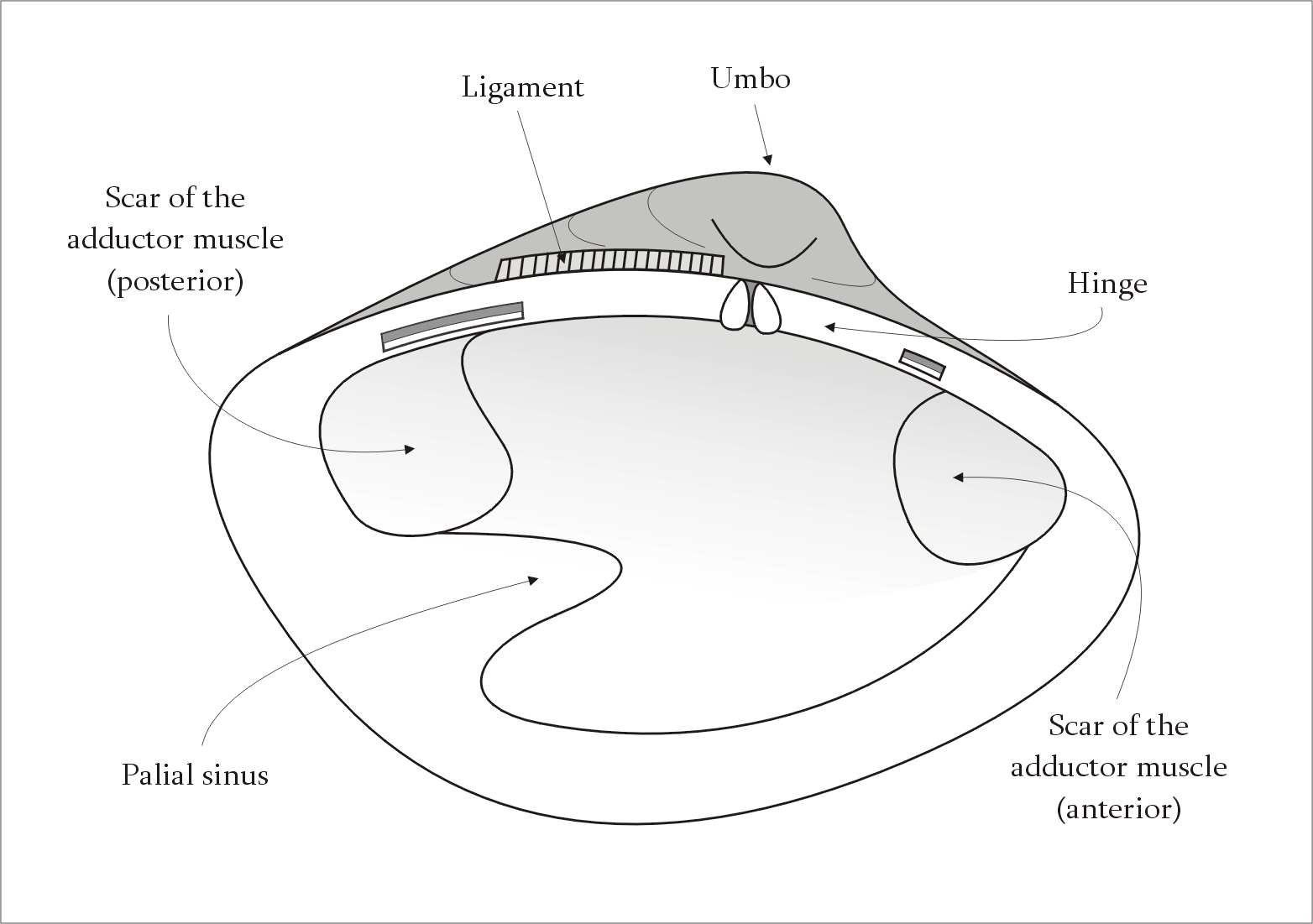

Anatomy

bilaterally symmetrical

Symmetry in biology refers to the symmetry observed in organisms, including plants, animals, fungi, and bacteria. External symmetry can be easily seen by just looking at an organism. For example, take the face of a human being which has a pla ...

and laterally flattened bodies, with a blade-shaped foot, vestigial head and no radula

The radula (, ; plural radulae or radulas) is an anatomical structure used by molluscs for feeding, sometimes compared to a tongue. It is a minutely toothed, chitinous ribbon, which is typically used for scraping or cutting food before the food ...

. At the dorsal or back region of the shell is the hinge point or line, which contain the umbo and beak

The beak, bill, or rostrum is an external anatomical structure found mostly in birds, but also in turtles, non-avian dinosaurs and a few mammals. A beak is used for eating, preening, manipulating objects, killing prey, fighting, probing for food ...

and the lower, curved margin is the ventral or back region. The anterior or front of the shell is where the byssus

A byssus () is a bundle of filaments secreted by many species of bivalve mollusc that function to attach the mollusc to a solid surface. Species from several families of clams have a byssus, including pen shells (Pinnidae), true mussels (Mytilid ...

(when present) and foot are located, and the posterior of the shell is where the siphons are located. With the hinge uppermost and with the anterior edge of the animal towards the viewer's left, the valve facing the viewer is the left valve and the opposing valve the right.

Mantle and shell

The shell is composed of twocalcareous

Calcareous () is an adjective meaning "mostly or partly composed of calcium carbonate", in other words, containing lime or being chalky. The term is used in a wide variety of scientific disciplines.

In zoology

''Calcareous'' is used as an adje ...

valves held together by a ligament. The valves are made of either calcite

Calcite is a Carbonate minerals, carbonate mineral and the most stable Polymorphism (materials science), polymorph of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). It is a very common mineral, particularly as a component of limestone. Calcite defines hardness 3 on ...

, as is the case in oysters, or both calcite and aragonite

Aragonite is a carbonate mineral, one of the three most common naturally occurring crystal forms of calcium carbonate, (the other forms being the minerals calcite and vaterite). It is formed by biological and physical processes, including prec ...

. Sometimes, the aragonite forms an inner, nacre

Nacre ( , ), also known as mother of pearl, is an organicinorganic composite material produced by some molluscs as an inner shell layer; it is also the material of which pearls are composed. It is strong, resilient, and iridescent.

Nacre is f ...

ous layer, as is the case in the order Pteriida

The Pteriida are an order of large and medium-sized marine bivalve mollusks. It includes five families, among them the Pteriidae (pearl oysters and winged oysters).

2010 taxonomy

In 2010, a new proposed classification system for the Bivalvia ...

. In other taxa

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; plural taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular nam ...

, alternate layers of calcite and aragonite are laid down. The ligament and byssus, if calcified, are composed of aragonite. The outermost layer of the shell is the periostracum

The periostracum ( ) is a thin, organic coating (or "skin") that is the outermost layer of the shell of many shelled animals, including molluscs and brachiopods. Among molluscs, it is primarily seen in snails and clams, i.e. in gastropods and ...

, a thin layer composed of horny conchiolin

Conchiolins (sometimes referred to as conchins) are complex proteins which are secreted by a mollusc's outer epithelium (the mantle).

These proteins are part of a matrix of organic macromolecules, mainly proteins and polysaccharides, that assem ...

. The periostracum is secreted by the outer mantle and is easily abraded. The outer surface of the valves is often sculpted, with clams often having concentric striations, scallops having radial ribs and oysters a latticework of irregular markings.

In all molluscs, the mantle

A mantle is a piece of clothing, a type of cloak. Several other meanings are derived from that.

Mantle may refer to:

*Mantle (clothing), a cloak-like garment worn mainly by women as fashionable outerwear

**Mantle (vesture), an Eastern Orthodox ve ...

forms a thin membrane

A membrane is a selective barrier; it allows some things to pass through but stops others. Such things may be molecules, ions, or other small particles. Membranes can be generally classified into synthetic membranes and biological membranes. B ...

that covers the animal's body and extends out from it in flaps or lobes. In bivalves, the mantle lobes secrete the valves, and the mantle crest secretes the whole hinge mechanism consisting of ligament

A ligament is the fibrous connective tissue that connects bones to other bones. It is also known as ''articular ligament'', ''articular larua'', ''fibrous ligament'', or ''true ligament''. Other ligaments in the body include the:

* Peritoneal li ...

, byssus threads (where present), and teeth

A tooth ( : teeth) is a hard, calcified structure found in the jaws (or mouths) of many vertebrates and used to break down food. Some animals, particularly carnivores and omnivores, also use teeth to help with capturing or wounding prey, tear ...

. The posterior mantle edge may have two elongated extensions known as siphons

A siphon (from grc, σίφων, síphōn, "pipe, tube", also spelled nonetymologically syphon) is any of a wide variety of devices that involve the flow of liquids through tubes. In a narrower sense, the word refers particularly to a tube in a ...

, through one of which water is inhaled, and the other expelled. The siphons retract into a cavity, known as the pallial sinus

The pallial sinus is an indentation or inward bending in the pallial line on the interior of a bivalve mollusk shell's valves that corresponds to the position of the siphons in those types of clams which have siphons (i.e. siphonate). The posit ...

.

The shell grows larger when more material is secreted by the mantle edge, and the valves themselves thicken as more material is secreted from the general mantle surface. Calcareous matter comes from both its diet and the surrounding seawater. Concentric rings on the exterior of a valve are commonly used to age bivalves. For some groups, a more precise method for determining the age of a shell is by cutting a cross section through it and examining the incremental growth bands.

The shipworm

The shipworms are marine bivalve molluscs in the family Teredinidae: a group of saltwater clams with long, soft, naked bodies. They are notorious for boring into (and commonly eventually destroying) wood that is immersed in sea water, including ...

s, in the family Teredinidae

The shipworms are marine bivalve molluscs in the family Teredinidae: a group of saltwater clams with long, soft, naked bodies. They are notorious for boring into (and commonly eventually destroying) wood that is immersed in sea water, includin ...

have greatly elongated bodies, but their shell valves are much reduced and restricted to the anterior end of the body, where they function as scraping organs that permit the animal to dig tunnels through wood.

Muscles and ligaments

The main muscular system in bivalves is the posterior and anterior adductor muscles. These muscles connect the two valves and contract to close the shell. The valves are also joined dorsally by the hingeligament

A ligament is the fibrous connective tissue that connects bones to other bones. It is also known as ''articular ligament'', ''articular larua'', ''fibrous ligament'', or ''true ligament''. Other ligaments in the body include the:

* Peritoneal li ...

, which is an extension of the periostracum. The ligament is responsible for opening the shell, and works against the adductor muscles when the animal opens and closes. Retractor muscles connect the mantle to the edge of the shell, along a line known as the pallial line

The pallial line is a mark (a line) on the interior of each valve of the shell of a bivalve mollusk. This line shows where all of the mantle

A mantle is a piece of clothing, a type of cloak. Several other meanings are derived from that.

Mantle m ...

. These muscles pull the mantle though the valves.

In sedentary or recumbent bivalves that lie on one valve, such as the oysters and scallops, the anterior adductor muscle has been lost and the posterior muscle is positioned centrally. In species that can swim by flapping their valves, a single, central adductor muscle occurs. These muscles are composed of two types of muscle fibres, striated muscle bundles for fast actions and smooth muscle bundles for maintaining a steady pull. Paired pedal protractor and retractor muscles operate the animal's foot.

Nervous system

The sedentary habits of the bivalves have meant that in general thenervous system

In biology, the nervous system is the highly complex part of an animal that coordinates its actions and sensory information by transmitting signals to and from different parts of its body. The nervous system detects environmental changes th ...

is less complex than in most other molluscs. The animals have no brain

A brain is an organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It is located in the head, usually close to the sensory organs for senses such as vision. It is the most complex organ in a v ...

; the nervous system consists of a nerve net

A nerve net consists of interconnected neurons lacking a brain or any form of cephalization. While organisms with bilateral body symmetry are normally associated with a condensation of neurons or, in more advanced forms, a central nervous syst ...

work and a series of paired ganglia

A ganglion is a group of neuron cell bodies in the peripheral nervous system. In the somatic nervous system this includes dorsal root ganglia and trigeminal ganglia among a few others. In the autonomic nervous system there are both sympatheti ...

. In all but the most primitive bivalves, two cerebropleural ganglia are on either side of the oesophagus

The esophagus (American English) or oesophagus (British English; both ), non-technically known also as the food pipe or gullet, is an organ in vertebrates through which food passes, aided by peristaltic contractions, from the pharynx to the ...

. The cerebral ganglia control the sensory organs, while the pleural ganglia supply nerves to the mantle cavity. The pedal ganglia, which control the foot, are at its base, and the visceral ganglia, which can be quite large in swimming bivalves, are under the posterior adductor muscle. These ganglia are both connected to the cerebropleural ganglia by nerve fibres

An axon (from Greek ἄξων ''áxōn'', axis), or nerve fiber (or nerve fibre: see spelling differences), is a long, slender projection of a nerve cell, or neuron, in vertebrates, that typically conducts electrical impulses known as action po ...

. Bivalves with long siphons may also have siphonal ganglia to control them.

Senses

The sensory organs of bivalves are largely located on the posterior mantle margins. The organs are usuallymechanoreceptor

A mechanoreceptor, also called mechanoceptor, is a sensory receptor that responds to mechanical pressure or distortion. Mechanoreceptors are innervated by sensory neurons that convert mechanical pressure into electrical signals that, in animals, ...

s or chemoreceptor

A chemoreceptor, also known as chemosensor, is a specialized sensory receptor which transduces a chemical substance (endogenous or induced) to generate a biological signal. This signal may be in the form of an action potential, if the chemorecept ...

s, in some cases located on short tentacle

In zoology, a tentacle is a flexible, mobile, and elongated organ present in some species of animals, most of them invertebrates. In animal anatomy, tentacles usually occur in one or more pairs. Anatomically, the tentacles of animals work main ...

s. The osphradium

The osphradium is a pigmented chemosensory epithelium patch in the mantle cavity present in six of the eight extant classes of molluscs (it is absent in the scaphopoda and monoplacophora; among cephalopoda, only the nautilus has what appears to be ...

is a patch of sensory cells located below the posterior adductor muscle that may serve to taste the water or measure its turbidity

Turbidity is the cloudiness or haziness of a fluid caused by large numbers of individual particles that are generally invisible to the naked eye, similar to smoke in air. The measurement of turbidity is a key test of water quality.

Fluids can ...

. Statocyst

The statocyst is a balance sensory receptor present in some aquatic invertebrates, including bivalves, cnidarians, ctenophorans, echinoderms, cephalopods, and crustaceans. A similar structure is also found in ''Xenoturbella''. The statocyst cons ...

s within the organism help the bivalve to sense and correct its orientation. In the order

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* Heterarchy, a system of organization wherein the elements have the potential to be ranked a number of d ...

Anomalodesmata

Anomalodesmata is an superorder of saltwater clams, marine bivalve molluscs. This grouping was formerly recognised as a taxonomic subclass. It is called a superorder in the current World Register of Marine Species, despite having no orders, to ...

, the inhalant siphon is surrounded by vibration-sensitive tentacles for detecting prey. Many bivalves have no eyes, but a few members of the Arcoidea, Limopsoidea, Mytiloidea, Anomioidea, Ostreoidea, and Limoidea have simple eyes on the margin of the mantle. These consist of a pit of photosensory cells and a lens

A lens is a transmissive optical device which focuses or disperses a light beam by means of refraction. A simple lens consists of a single piece of transparent material, while a compound lens consists of several simple lenses (''elements''), ...

. Scallop

Scallop () is a common name that encompasses various species of marine bivalve mollusks in the taxonomic family Pectinidae, the scallops. However, the common name "scallop" is also sometimes applied to species in other closely related families ...

s have more complex eyes with a lens, a two-layered retina

The retina (from la, rete "net") is the innermost, light-sensitive layer of tissue of the eye of most vertebrates and some molluscs. The optics of the eye create a focused two-dimensional image of the visual world on the retina, which then ...

, and a concave mirror. All bivalves have light-sensitive cells that can detect a shadow falling over the animal.

Circulation and respiration

Bivalves have an open

Bivalves have an open circulatory system

The blood circulatory system is a system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the entire body of a human or other vertebrate. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, tha ...

that bathes the organs in blood (hemolymph

Hemolymph, or haemolymph, is a fluid, analogous to the blood in vertebrates, that circulates in the interior of the arthropod (invertebrate) body, remaining in direct contact with the animal's tissues. It is composed of a fluid plasma in which ...

). The heart

The heart is a muscular organ in most animals. This organ pumps blood through the blood vessels of the circulatory system. The pumped blood carries oxygen and nutrients to the body, while carrying metabolic waste such as carbon dioxide t ...

has three chambers: two auricles receiving blood from the gills, and a single ventricle. The ventricle is muscular and pumps hemolymph into the aorta

The aorta ( ) is the main and largest artery in the human body, originating from the left ventricle of the heart and extending down to the abdomen, where it splits into two smaller arteries (the common iliac arteries). The aorta distributes ...

, and then to the rest of the body. Some bivalves have a single aorta, but most also have a second, usually smaller, aorta serving the hind parts of the animal. The hemolymph usually lacks any respiratory pigment. In the carnivorous genus '' Poromya'', the hemolymph has red amoebocyte An amebocyte or amoebocyte () is a mobile cell (moving like an amoeba) in the body of invertebrates including cnidaria, echinoderms, molluscs, tunicates, sponges and some chelicerates. They move by pseudopodia. Similarly to some of the white blood c ...

s containing a haemoglobin pigment.

The paired gills are located posteriorly and consist of hollow tube-like filaments with thin walls for gas exchange

Gas exchange is the physical process by which gases move passively by Diffusion#Diffusion vs. bulk flow, diffusion across a surface. For example, this surface might be the air/water interface of a water body, the surface of a gas bubble in a liqui ...

. The respiratory demands of bivalves are low, due to their relative inactivity. Some freshwater species, when exposed to the air, can gape the shell slightly and gas exchange can take place. Oysters, including the Pacific oyster

The Pacific oyster, Japanese oyster, or Miyagi oyster (''Magallana gigas''), is an oyster native to the Pacific coast of Asia. It has become an introduced species in North America, Australia, Europe, and New Zealand.

Etymology

The genus ''Mag ...

(''Magallana gigas''), are recognized as having varying metabolic responses to environmental stress, with changes in respiration rate being frequently observed.

Digestive system

Modes of feeding

Most bivalves arefilter feeder

Filter feeders are a sub-group of suspension feeding animals that feed by straining suspended matter and food particles from water, typically by passing the water over a specialized filtering structure. Some animals that use this method of feedin ...

s, using their gills to capture particulate food such as phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), meaning 'wanderer' or 'drifter'.

Ph ...

from the water. Protobranchs feed in a different way, scraping detritus from the seabed, and this may be the original mode of feeding used by all bivalves before the gills became adapted for filter feeding. These primitive bivalves hold on to the bottom with a pair of tentacles at the edge of the mouth, each of which has a single palp

Pedipalps (commonly shortened to palps or palpi) are the second pair of appendages of chelicerates – a group of arthropods including spiders, scorpions, horseshoe crabs, and sea spiders. The pedipalps are lateral to the chelicerae ("jaws") and ...

, or flap. The tentacles are covered in mucus

Mucus ( ) is a slippery aqueous secretion produced by, and covering, mucous membranes. It is typically produced from cells found in mucous glands, although it may also originate from mixed glands, which contain both serous and mucous cells. It is ...

, which traps the food, and cilia, which transport the particles back to the palps. These then sort the particles, rejecting those that are unsuitable or too large to digest, and conveying others to the mouth.

In more advanced bivalves, water is drawn into the shell from the posterior ventral

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously describe the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek language, Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. Th ...

surface of the animal, passes upwards through the gills, and doubles back to be expelled just above the intake. There may be two elongated, retractable siphons reaching up to the seabed, one each for the inhalant and exhalant streams of water. The gills of filter-feeding bivalves are known as ctenidia and have become highly modified to increase their ability to capture food. For example, the cilia

The cilium, plural cilia (), is a membrane-bound organelle found on most types of eukaryotic cell, and certain microorganisms known as ciliates. Cilia are absent in bacteria and archaea. The cilium has the shape of a slender threadlike projecti ...

on the gills, which originally served to remove unwanted sediment, have become adapted to capture food particles, and transport them in a steady stream of mucus to the mouth. The filaments of the gills are also much longer than those in more primitive bivalves, and are folded over to create a groove through which food can be transported. The structure of the gills varies considerably, and can serve as a useful means for classifying bivalves into groups.

A few bivalves, such as the granular poromya (''Poromya granulata''), are carnivorous

A carnivore , or meat-eater (Latin, ''caro'', genitive ''carnis'', meaning meat or "flesh" and ''vorare'' meaning "to devour"), is an animal or plant whose food and energy requirements derive from animal tissues (mainly muscle, fat and other sof ...

, eating much larger prey

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill the ...

than the tiny microalgae consumed by other bivalves. Muscles draw water in through the inhalant siphon which is modified into a cowl-shaped organ, sucking in prey. The siphon can be retracted quickly and inverted, bringing the prey within reach of the mouth. The gut is modified so that large food particles can be digested.

The unusual genus, '' Entovalva'', is endosymbiotic

An ''endosymbiont'' or ''endobiont'' is any organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism most often, though not always, in a mutualistic relationship.

(The term endosymbiosis is from the Greek: ἔνδον ''endon'' "within" ...

, being found only in the oesophagus of sea cucumbers

Sea cucumbers are echinoderms from the class Holothuroidea (). They are marine animals with a leathery skin and an elongated body containing a single, branched gonad. Sea cucumbers are found on the sea floor worldwide. The number of holothuria ...

. It has mantle folds that completely surround its small valves. When the sea cucumber sucks in sediment, the bivalve allows the water to pass over its gills and extracts fine organic particles. To prevent itself from being swept away, it attaches itself with byssal threads to the host

A host is a person responsible for guests at an event or for providing hospitality during it.

Host may also refer to:

Places

* Host, Pennsylvania, a village in Berks County

People

*Jim Host (born 1937), American businessman

* Michel Host ...

's throat. The sea cucumber is unharmed.

Digestive tract

The digestive tract of typical bivalves consists of anoesophagus

The esophagus (American English) or oesophagus (British English; both ), non-technically known also as the food pipe or gullet, is an organ in vertebrates through which food passes, aided by peristaltic contractions, from the pharynx to the ...

, stomach

The stomach is a muscular, hollow organ in the gastrointestinal tract of humans and many other animals, including several invertebrates. The stomach has a dilated structure and functions as a vital organ in the digestive system. The stomach i ...

, and intestine

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans ...

. Protobranch stomachs have a mere sac attached to them while filter-feeding bivalves have elongated rod of solidified mucus referred to as the "crystalline style

A style, sometimes referred to as a crystalline style (though there are no other biological kinds), is a rod made of glycoprotein located in the midgut of most bivalves and some gastropods

The gastropods (), commonly known as snails and slugs, ...

" projected into the stomach from an associated sac. Cilia in the sac cause the style to rotate, winding in a stream of food-containing mucus from the mouth, and churning the stomach contents. This constant motion propels food particles into a sorting region at the rear of the stomach, which distributes smaller particles into the digestive glands, and heavier particles into the intestine. Waste material is consolidated in the rectum and voided as pellets into the exhalent water stream through an anal pore. Feeding and digestion are synchronized with diurnal and tidal cycles.

Carnivorous bivalves generally have reduced crystalline styles and the stomach has thick, muscular walls, extensive cuticular

A cuticle (), or cuticula, is any of a variety of tough but flexible, non-mineral outer coverings of an organism, or parts of an organism, that provide protection. Various types of "cuticle" are non- homologous, differing in their origin, structu ...

linings and diminished sorting areas and gastric chamber sections.

Excretory system

The excretory organs of bivalves are a pair ofnephridia

The nephridium (plural ''nephridia'') is an invertebrate organ, found in pairs and performing a function similar to the vertebrate kidneys (which originated from the chordate nephridia). Nephridia remove metabolic wastes from an animal's body. Neph ...

. Each of these consists of a long, looped, glandular tube, which opens into the pericardium

The pericardium, also called pericardial sac, is a double-walled sac containing the heart and the roots of the great vessels. It has two layers, an outer layer made of strong connective tissue (fibrous pericardium), and an inner layer made of ...

, and a bladder

The urinary bladder, or simply bladder, is a hollow organ in humans and other vertebrates that stores urine from the kidneys before disposal by urination. In humans the bladder is a distensible organ that sits on the pelvic floor. Urine enters ...

to store urine. They also have pericardial glands either line the auricles of the heart or attach to the pericardium, and serve as extra filtration organs. Metabolic waste is voided from the bladders through a nephridiopore A nephridiopore is part of the nephridium, an excretory organ found in many organisms, such as flatworms and annelids. Polychaetes typically release their gametes into the water column using nephridiopores.

Nephridia are homologous to nephrons or ...

near the front of the upper part of the mantle cavity and excreted.

Reproduction and development

The sexes are usually separate in bivalves but somehermaphroditism

In reproductive biology, a hermaphrodite () is an organism that has both kinds of reproductive organs and can produce both gametes associated with male and female sexes.

Many taxonomic groups of animals (mostly invertebrates) do not have separ ...

is known. The gonad

A gonad, sex gland, or reproductive gland is a mixed gland that produces the gametes and sex hormones of an organism. Female reproductive cells are egg cells, and male reproductive cells are sperm. The male gonad, the testicle, produces sper ...

s and either open into the nephridia, or through a separate pore into a chamber over the gills. The ripe gonads of males and females release sperm and eggs into the water column

A water column is a conceptual column of water from the surface of a sea, river or lake to the bottom sediment.Munson, B.H., Axler, R., Hagley C., Host G., Merrick G., Richards C. (2004).Glossary. ''Water on the Web''. University of Minnesota-D ...

. Spawning

Spawn is the eggs and sperm released or deposited into water by aquatic animals. As a verb, ''to spawn'' refers to the process of releasing the eggs and sperm, and the act of both sexes is called spawning. Most aquatic animals, except for aquati ...

may take place continually or be triggered by environmental factors such as day length, water temperature, or the presence of sperm in the water. Some species are "dribble spawners", releasing gametes during protracted period that can extend for weeks. Others are mass spawners and release their gametes in batches or all at once.

Fertilization is usually external. Typically, a short stage lasts a few hours or days before the eggs hatch into trochophore

A trochophore (; also spelled trocophore) is a type of free-swimming planktonic marine larva with several bands of cilia.

By moving their cilia rapidly, they make a water eddy, to control their movement, and to bring their food closer, to captur ...

larvae. These later develop into veliger

A veliger is the planktonic larva of many kinds of sea snails and freshwater snails, as well as most bivalve molluscs (clams) and tusk shells.

Description

The veliger is the characteristic larva of the gastropod, bivalve and scaphopod ...

larvae which settle on the seabed and undergo metamorphosis

Metamorphosis is a biological process by which an animal physically develops including birth or hatching, involving a conspicuous and relatively abrupt change in the animal's body structure through cell growth and differentiation. Some inse ...

into adults. In some species, such as those in the genus ''Lasaea

Lasaea or Lasaia ( grc, Λασαία) was a city on the south coast of ancient Crete, near the roadstead of the "Fair Havens" where apostle Paul landed. This place is not mentioned by any other writer, under this name but is probably the same as ...

'', females draw water containing sperm in through their inhalant siphons and fertilization takes place inside the female. These species then brood the young inside their mantle cavity, eventually releasing them into the water column as veliger larvae or as crawl-away juveniles.

Most of the bivalve larvae that hatch from eggs in the water column feed on diatom

A diatom (Neo-Latin ''diatoma''), "a cutting through, a severance", from el, διάτομος, diátomos, "cut in half, divided equally" from el, διατέμνω, diatémno, "to cut in twain". is any member of a large group comprising sev ...

s or other phytoplankton. In temperate

In geography, the temperate climates of Earth occur in the middle latitudes (23.5° to 66.5° N/S of Equator), which span between the tropics and the polar regions of Earth. These zones generally have wider temperature ranges throughout t ...

regions, about 25% of species are lecithotrophic

Oviparous animals are animals that lay their eggs, with little or no other embryonic development within the mother. This is the reproductive method of most fish, amphibians, most reptiles, and all pterosaurs, dinosaurs (including birds), and mo ...

, depending on nutrients stored in the yolk of the egg where the main energy source is lipid

Lipids are a broad group of naturally-occurring molecules which includes fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids include ...

s. The longer the period is before the larva first feeds, the larger the egg and yolk need to be. The reproductive cost of producing these energy-rich eggs is high and they are usually smaller in number. For example, the Baltic tellin (''Macoma balthica

''Limecola balthica'', commonly called the Baltic macoma, Baltic clam or Baltic tellin,Sartori, André F. (2016)''Limecola balthica'' (Linnaeus, 1758).In: Sartori, André F. (2016). Limecola balthica (Linnaeus, 1758). In: MolluscaBase (2016). W ...

'') produces few, high-energy eggs. The larvae hatching out of these rely on the energy reserves and do not feed. After about four days, they become D-stage larvae, when they first develop hinged, D-shaped valves. These larvae have a relatively small dispersal potential before settling out. The common mussel (''Mytilus edulis

The blue mussel (''Mytilus edulis''), also known as the common mussel, is a medium-sized edible marine (ocean), marine bivalve mollusc in the family (biology), family Mytilidae, the mussels. Blue mussels are subject to commercial use and intensiv ...

'') produces 10 times as many eggs that hatch into larvae and soon need to feed to survive and grow. They can disperse more widely as they remain planktonic for a much longer time.

Freshwater bivalves have different lifecycle. Sperm is drawn into a female's gills with the inhalant water and internal fertilization takes place. The eggs hatch into glochidia

The glochidium (plural glochidia) is a microscopic larval stage of some freshwater mussels, aquatic bivalve mollusks in the families Unionidae and Margaritiferidae, the river mussels and European freshwater pearl mussels.

These larvae are ...

larvae that develop within the female's shell. Later they are released and attach themselves parasitically to the gills

A gill () is a respiratory organ that many aquatic organisms use to extract dissolved oxygen from water and to excrete carbon dioxide. The gills of some species, such as hermit crabs, have adapted to allow respiration on land provided they are ...

or fins of a fish host. After several weeks they drop off their host, undergo metamorphosis and develop into adults on the substrate.

Some of the species in the freshwater mussel family, Unionidae

The Unionidae are a family of freshwater mussels, the largest in the order Unionida, the bivalve molluscs sometimes known as river mussels, or simply as unionids.

The range of distribution for this family is world-wide. It is at its most diverse ...

, commonly known as pocketbook mussels, have evolved an unusual reproductive strategy. The female's mantle protrudes from the shell and develops into an imitation small fish, complete with fish-like markings and false eyes. This decoy moves in the current and attracts the attention of real fish. Some fish see the decoy as prey, while others see a conspecific

Biological specificity is the tendency of a characteristic such as a behavior or a biochemical variation to occur in a particular species.

Biochemist Linus Pauling stated that "Biological specificity is the set of characteristics of living organ ...

. They approach for a closer look and the mussel releases huge numbers of larvae from its gills, dousing the inquisitive fish with its tiny, parasitic young. These glochidia larvae are drawn into the fish's gills, where they attach and trigger a tissue response that forms a small cyst

A cyst is a closed sac, having a distinct envelope and cell division, division compared with the nearby Biological tissue, tissue. Hence, it is a cluster of Cell (biology), cells that have grouped together to form a sac (like the manner in which ...

around each larva. The larvae then feed by breaking down and digesting the tissue of the fish within the cysts. After a few weeks they release themselves from the cysts and fall to the stream bed as juvenile molluscs.

Comparison with brachiopods

Brachiopod

Brachiopods (), phylum Brachiopoda, are a phylum of trochozoan animals that have hard "valves" (shells) on the upper and lower surfaces, unlike the left and right arrangement in bivalve molluscs. Brachiopod valves are hinged at the rear end, w ...

s are shelled marine organisms that superficially resembled bivalves in that they are of similar size and have a hinged shell in two parts. However, brachiopods evolved from a very different ancestral line, and the resemblance to bivalves only arose because they occupy similar ecological niches

In ecology, a niche is the match of a species to a specific environmental condition.

Three variants of ecological niche are described by

It describes how an organism or population responds to the distribution of resources and competitors (for ...

. The differences between the two groups are due to their separate ancestral origins. Different initial structures have been adapted to solve the same problems, a case of convergent evolution

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last com ...

. In modern times, brachiopods are not as common as bivalves.

Both groups have a shell consisting of two valves, but the organization of the shell is quite different in the two groups. In brachiopods, the two valves are positioned on the dorsal and ventral surfaces of the body, while in bivalves, the valves are on the left and right sides of the body, and are, in most cases, mirror images of one other. Brachiopods have a lophophore

The lophophore () is a characteristic feeding organ possessed by four major groups of animals: the Brachiopoda, Bryozoa, Hyolitha, and Phoronida, which collectively constitute the protostome group Lophophorata.bryozoa

Bryozoa (also known as the Polyzoa, Ectoprocta or commonly as moss animals) are a phylum of simple, aquatic invertebrate animals, nearly all living in sedentary colonies. Typically about long, they have a special feeding structure called a l ...

ns and the phoronid

Phoronids (scientific name Phoronida, sometimes called horseshoe worms) are a small phylum of marine animals that filter-feed with a lophophore (a "crown" of tentacles), and build upright tubes of chitin to support and protect their soft bodies. ...

s. Some brachiopod shells are made of calcium phosphate

The term calcium phosphate refers to a family of materials and minerals containing calcium ions (Ca2+) together with inorganic phosphate anions. Some so-called calcium phosphates contain oxide and hydroxide as well. Calcium phosphates are white ...

but most are calcium carbonate in the form of the biomineral calcite

Calcite is a Carbonate minerals, carbonate mineral and the most stable Polymorphism (materials science), polymorph of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). It is a very common mineral, particularly as a component of limestone. Calcite defines hardness 3 on ...

, whereas bivalve shells are always composed entirely of calcium carbonate, often in the form of the biomineral aragonite

Aragonite is a carbonate mineral, one of the three most common naturally occurring crystal forms of calcium carbonate, (the other forms being the minerals calcite and vaterite). It is formed by biological and physical processes, including prec ...

.

Evolutionary history

TheCambrian explosion

The Cambrian explosion, Cambrian radiation, Cambrian diversification, or the Biological Big Bang refers to an interval of time approximately in the Cambrian Period when practically all major animal phyla started appearing in the fossil recor ...

took place around 540 to 520 million years ago (Mya). In this geologically brief period, all the major animal phyla Phyla, the plural of ''phylum'', may refer to:

* Phylum, a biological taxon between Kingdom and Class

* by analogy, in linguistics, a large division of possibly related languages, or a major language family which is not subordinate to another

Phyl ...

diverged and these included the first creatures with mineralized skeletons. Brachiopods and bivalves made their appearance at this time, and left their fossilized remains behind in the rocks.

Possible early bivalves include ''Pojetaia

''Pojetaia'' is an extinct genus of early bivalves, one of two genera in the extinct family Fordillidae. The genus is known solely from Early to Middle Cambrian fossils found in North America, Greenland, Europe, North Africa, Asia, and Australia ...

'' and ''Fordilla

''Fordilla'' is an extinct genus of early bivalves, one of two genera in the extinct family Fordillidae. The genus is known solely from Early Cambrian fossils found in North America, Greenland, Europe, the Middle East, and Asia.Tuarangia

''Tuarangia'' is a Cambrian shelly fossil interpreted as an early bivalve, though alternative classifications have been proposed and its systematic position remains controversial.Elicki, O., & Gürsu