Biology on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a

The earliest of roots of science, which included medicine, can be traced to ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia in around 3000 to 1200 BCE. Their contributions later entered and shaped Greek natural philosophy of

The earliest of roots of science, which included medicine, can be traced to ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia in around 3000 to 1200 BCE. Their contributions later entered and shaped Greek natural philosophy of  Serious evolutionary thinking originated with the works of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, who was the first to present a coherent theory of evolution. Gould, Stephen Jay. ''The Structure of Evolutionary Theory''. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 2002. . p. 187. He posited that evolution was the result of environmental stress on properties of animals, meaning that the more frequently and rigorously an organ was used, the more complex and efficient it would become, thus adapting the animal to its environment. Lamarck believed that these acquired traits could then be passed on to the animal's offspring, who would further develop and perfect them. Lamarck (1914) However, it was the British naturalist

Serious evolutionary thinking originated with the works of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, who was the first to present a coherent theory of evolution. Gould, Stephen Jay. ''The Structure of Evolutionary Theory''. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 2002. . p. 187. He posited that evolution was the result of environmental stress on properties of animals, meaning that the more frequently and rigorously an organ was used, the more complex and efficient it would become, thus adapting the animal to its environment. Lamarck believed that these acquired traits could then be passed on to the animal's offspring, who would further develop and perfect them. Lamarck (1914) However, it was the British naturalist

Proteins are the most diverse of the macromolecules, which include enzymes, transport proteins, large

Proteins are the most diverse of the macromolecules, which include enzymes, transport proteins, large

Every cell is enclosed within a cell membrane that separates its cytoplasm from the extracellular space. A cell membrane consists of a lipid bilayer, including cholesterols that sit between

Every cell is enclosed within a cell membrane that separates its cytoplasm from the extracellular space. A cell membrane consists of a lipid bilayer, including cholesterols that sit between  Within the cytoplasm of a cell, there are many

Within the cytoplasm of a cell, there are many

in Chapter 21 of

Molecular Biology of the Cell

'' fourth edition, edited by Bruce Alberts (2002) published by Garland Science.

The Alberts text discusses how the "cellular building blocks" move to shape developing

molecular building blocks

". In addition to biomolecules, eukaryotic cells have specialized structures called

All cells require energy to sustain cellular processes. Energy is the capacity to do work, which, in thermodynamics, can be calculated using Gibbs free energy. According to the first law of thermodynamics, energy is conserved, i.e., cannot be created or destroyed. Hence, chemical reactions in a cell do not create new energy but are involved instead in the transformation and transfer of energy. Nevertheless, all energy transfers lead to some loss of usable energy, which increases entropy (or state of disorder) as stated by the second law of thermodynamics. As a result, an organism requires continuous input of energy to maintain a low state of entropy. In cells, energy can be transferred as electrons during redox (reduction–oxidation) reactions, stored in covalent bonds, and generated by the movement of ions (e.g., hydrogen, sodium, potassium) across a membrane.

Metabolism is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main purposes of metabolism are: the conversion of food to energy to run cellular processes; the conversion of food/fuel to building blocks for proteins, lipids,

All cells require energy to sustain cellular processes. Energy is the capacity to do work, which, in thermodynamics, can be calculated using Gibbs free energy. According to the first law of thermodynamics, energy is conserved, i.e., cannot be created or destroyed. Hence, chemical reactions in a cell do not create new energy but are involved instead in the transformation and transfer of energy. Nevertheless, all energy transfers lead to some loss of usable energy, which increases entropy (or state of disorder) as stated by the second law of thermodynamics. As a result, an organism requires continuous input of energy to maintain a low state of entropy. In cells, energy can be transferred as electrons during redox (reduction–oxidation) reactions, stored in covalent bonds, and generated by the movement of ions (e.g., hydrogen, sodium, potassium) across a membrane.

Metabolism is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main purposes of metabolism are: the conversion of food to energy to run cellular processes; the conversion of food/fuel to building blocks for proteins, lipids,

Photosynthesis is a process used by plants and other organisms to convert light energy into

Photosynthesis is a process used by plants and other organisms to convert light energy into

The cell cycle is a series of events that take place in a cell that cause it to divide into two daughter cells. These events include the duplication of its DNA and some of its

The cell cycle is a series of events that take place in a cell that cause it to divide into two daughter cells. These events include the duplication of its DNA and some of its

Genetics is the scientific study of inheritance. Mendelian inheritance, specifically, is the process by which genes and traits are passed on from parents to offspring. It was formulated by Gregor Mendel, based on his work with pea plants in the mid-nineteenth century. Mendel established several principles of inheritance. The first is that genetic characteristics, which are now called alleles, are discrete and have alternate forms (e.g., purple vs. white or tall vs. dwarf), each inherited from one of two parents. Based on his law of dominance and uniformity, which states that some alleles are dominant while others are recessive; an organism with at least one dominant allele will display the phenotype of that dominant allele.Rutgers

Genetics is the scientific study of inheritance. Mendelian inheritance, specifically, is the process by which genes and traits are passed on from parents to offspring. It was formulated by Gregor Mendel, based on his work with pea plants in the mid-nineteenth century. Mendel established several principles of inheritance. The first is that genetic characteristics, which are now called alleles, are discrete and have alternate forms (e.g., purple vs. white or tall vs. dwarf), each inherited from one of two parents. Based on his law of dominance and uniformity, which states that some alleles are dominant while others are recessive; an organism with at least one dominant allele will display the phenotype of that dominant allele.Rutgers

Mendelian Principles

Exceptions to this rule include penetrance and expressivity. Mendel noted that during gamete formation, the alleles for each gene segregate from each other so that each gamete carries only one allele for each gene, which is stated by his law of segregation.

A gene is a unit of

A gene is a unit of

Gene expression is the molecular process by which a

Gene expression is the molecular process by which a

The regulation of gene expression (or gene regulation) by environmental factors and during different stages of development can occur at each step of the process such as transcription,

The regulation of gene expression (or gene regulation) by environmental factors and during different stages of development can occur at each step of the process such as transcription,

natural science

Natural science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer review and repeatab ...

with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditary information encoded in genes, which can be transmitted to future generations. Another major theme is evolution, which explains the unity and diversity of life. Energy processing is also important to life as it allows organisms to move, grow, and reproduce. Finally, all organisms are able to regulate their own internal environments.

Biologist

A biologist is a scientist who conducts research in biology. Biologists are interested in studying life on Earth, whether it is an individual cell, a multicellular organism, or a community of interacting populations. They usually speciali ...

s are able to study life at multiple levels of organization, from the molecular biology of a cell to the anatomy and physiology of plants and animals, and evolution of populations.Based on definition from: Hence, there are multiple subdisciplines within biology, each defined by the nature of their research questions and the tools that they use. Like other scientists, biologists use the scientific method to make observation

Observation is the active acquisition of information from a primary source. In living beings, observation employs the senses. In science, observation can also involve the perception and recording of data via the use of scientific instruments. The ...

s, pose questions, generate hypotheses

A hypothesis (plural hypotheses) is a proposed explanation for a phenomenon. For a hypothesis to be a scientific hypothesis, the scientific method requires that one can test it. Scientists generally base scientific hypotheses on previous obser ...

, perform experiments, and form conclusions about the world around them.

Life on Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surf ...

, which emerged more than 3.7 billion years ago, is immensely diverse. Biologists have sought to study and classify the various forms of life, from prokaryotic organisms such as archaea

Archaea ( ; singular archaeon ) is a domain of single-celled organisms. These microorganisms lack cell nuclei and are therefore prokaryotes. Archaea were initially classified as bacteria, receiving the name archaebacteria (in the Archaeb ...

and bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were am ...

to eukaryotic organisms such as protists, fungi, plants, and animals. These various organisms contribute to the biodiversity

Biodiversity or biological diversity is the variety and variability of life on Earth. Biodiversity is a measure of variation at the genetic ('' genetic variability''), species ('' species diversity''), and ecosystem ('' ecosystem diversity' ...

of an ecosystem, where they play specialized roles in the cycling of nutrient

A nutrient is a substance used by an organism to survive, grow, and reproduce. The requirement for dietary nutrient intake applies to animals, plants, fungi, and protists. Nutrients can be incorporated into cells for metabolic purposes or excret ...

s and energy through their biophysical environment

A biophysical environment is a biotic and abiotic surrounding of an organism or population, and consequently includes the factors that have an influence in their survival, development, and evolution. A biophysical environment can vary in scale f ...

.

History

The earliest of roots of science, which included medicine, can be traced to ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia in around 3000 to 1200 BCE. Their contributions later entered and shaped Greek natural philosophy of

The earliest of roots of science, which included medicine, can be traced to ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia in around 3000 to 1200 BCE. Their contributions later entered and shaped Greek natural philosophy of classical antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations ...

. Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic p ...

philosophers such as Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical Greece, Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatet ...

(384–322 BCE) contributed extensively to the development of biological knowledge. His works such as '' History of Animals'' were especially important because they revealed his naturalist leanings, and later more empirical works that focused on biological causation and the diversity of life. Aristotle's successor at the Lyceum, Theophrastus, wrote a series of books on botany that survived as the most important contribution of antiquity to the plant sciences, even into the Middle Ages.

Scholars of the medieval Islamic world

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

who wrote on biology included al-Jahiz (781–869), Al-Dīnawarī

Abū Ḥanīfa Aḥmad ibn Dāwūd Dīnawarī ( fa, ابوحنيفه دينوری; died 895) was a Persian Islamic Golden Age polymath, astronomer, agriculturist, botanist, metallurgist, geographer, mathematician, and historian.

Life

Dinawar ...

(828–896), who wrote on botany, and Rhazes (865–925) who wrote on anatomy and physiology. Medicine was especially well studied by Islamic scholars working in Greek philosopher traditions, while natural history drew heavily on Aristotelian thought, especially in upholding a fixed hierarchy of life.

Biology began to quickly develop and grow with Anton van Leeuwenhoek's dramatic improvement of the microscope. It was then that scholars discovered spermatozoa, bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were am ...

, infusoria and the diversity of microscopic life. Investigations by Jan Swammerdam led to new interest in entomology

Entomology () is the science, scientific study of insects, a branch of zoology. In the past the term "insect" was less specific, and historically the definition of entomology would also include the study of animals in other arthropod groups, such ...

and helped to develop the basic techniques of microscopic dissection

Dissection (from Latin ' "to cut to pieces"; also called anatomization) is the dismembering of the body of a deceased animal or plant to study its anatomical structure. Autopsy is used in pathology and forensic medicine to determine the cause o ...

and staining

Staining is a technique used to enhance contrast in samples, generally at the microscopic level. Stains and dyes are frequently used in histology (microscopic study of biological tissues), in cytology (microscopic study of cells), and in the ...

.

Advances in microscopy

Microscopy is the technical field of using microscopes to view objects and areas of objects that cannot be seen with the naked eye (objects that are not within the resolution range of the normal eye). There are three well-known branches of micr ...

also had a profound impact on biological thinking. In the early 19th century, a number of biologists pointed to the central importance of the cell. Then, in 1838, Schleiden and Schwann began promoting the now universal ideas that (1) the basic unit of organisms is the cell and (2) that individual cells have all the characteristics of life, although they opposed the idea that (3) all cells come from the division of other cells. However, Robert Remak and Rudolf Virchow were able to reify the third tenet, and by the 1860s most biologists accepted all three tenets which consolidated into cell theory.

Meanwhile, taxonomy and classification became the focus of natural historians. Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, ...

published a basic taxonomy for the natural world in 1735 (variations of which have been in use ever since), and in the 1750s introduced scientific names for all his species. Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, treated species as artificial categories and living forms as malleable—even suggesting the possibility of common descent

Common descent is a concept in evolutionary biology applicable when one species is the ancestor of two or more species later in time. All living beings are in fact descendants of a unique ancestor commonly referred to as the last universal comm ...

. Although he was opposed to evolution, Buffon is a key figure in the history of evolutionary thought; his work influenced the evolutionary theories of both Lamarck and Darwin

Darwin may refer to:

Common meanings

* Charles Darwin (1809–1882), English naturalist and writer, best known as the originator of the theory of biological evolution by natural selection

* Darwin, Northern Territory, a territorial capital city i ...

.

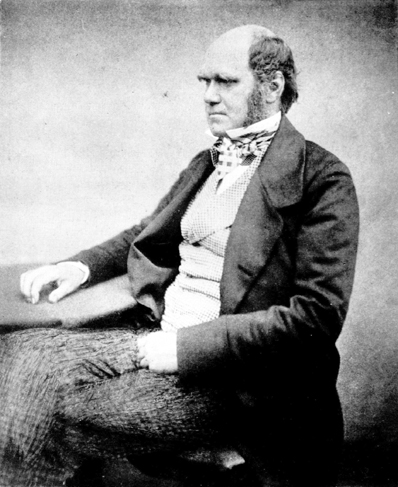

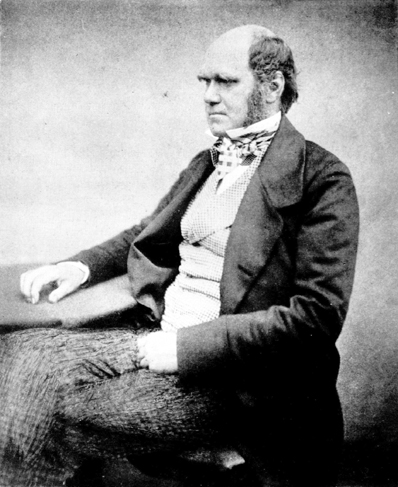

Serious evolutionary thinking originated with the works of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, who was the first to present a coherent theory of evolution. Gould, Stephen Jay. ''The Structure of Evolutionary Theory''. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 2002. . p. 187. He posited that evolution was the result of environmental stress on properties of animals, meaning that the more frequently and rigorously an organ was used, the more complex and efficient it would become, thus adapting the animal to its environment. Lamarck believed that these acquired traits could then be passed on to the animal's offspring, who would further develop and perfect them. Lamarck (1914) However, it was the British naturalist

Serious evolutionary thinking originated with the works of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, who was the first to present a coherent theory of evolution. Gould, Stephen Jay. ''The Structure of Evolutionary Theory''. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 2002. . p. 187. He posited that evolution was the result of environmental stress on properties of animals, meaning that the more frequently and rigorously an organ was used, the more complex and efficient it would become, thus adapting the animal to its environment. Lamarck believed that these acquired traits could then be passed on to the animal's offspring, who would further develop and perfect them. Lamarck (1914) However, it was the British naturalist Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

, combining the biogeographical approach of Humboldt Humboldt may refer to:

People

* Alexander von Humboldt, German natural scientist, brother of Wilhelm von Humboldt

* Wilhelm von Humboldt, German linguist, philosopher, and diplomat, brother of Alexander von Humboldt

Fictional characters

* ...

, the uniformitarian geology of Lyell, Malthus's writings on population growth, and his own morphological expertise and extensive natural observations, who forged a more successful evolutionary theory based on natural selection; similar reasoning and evidence led Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace (8 January 1823 – 7 November 1913) was a British naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator. He is best known for independently conceiving the theory of evolution through natural ...

to independently reach the same conclusions. Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection quickly spread through the scientific community and soon became a central axiom of the rapidly developing science of biology.

The basis for modern genetics began with the work of Gregor Mendel, who presented his paper, "''Versuche über Pflanzenhybriden''" (" Experiments on Plant Hybridization"), in 1865, which outlined the principles of biological inheritance, serving as the basis for modern genetics. However, the significance of his work was not realized until the early 20th century when evolution became a unified theory as the modern synthesis reconciled Darwinian evolution with classical genetics. In the 1940s and early 1950s, a series of experiments by Alfred Hershey

Alfred Day Hershey (December 4, 1908 – May 22, 1997) was an American Nobel Prize–winning bacteriologist and geneticist.

He was born in Owosso, Michigan and received his B.S. in chemistry at Michigan State University in 1930 and his Ph.D. ...

and Martha Chase pointed to DNA as the component of chromosomes that held the trait-carrying units that had become known as genes

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a ba ...

. A focus on new kinds of model organisms such as viruses and bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were am ...

, along with the discovery of the double-helical structure of DNA by James Watson

James Dewey Watson (born April 6, 1928) is an American molecular biologist, geneticist, and zoologist. In 1953, he co-authored with Francis Crick the academic paper proposing the double helix structure of the DNA molecule. Watson, Crick and ...

and Francis Crick

Francis Harry Compton Crick (8 June 1916 – 28 July 2004) was an English molecular biologist, biophysicist, and neuroscientist. He, James Watson, Rosalind Franklin, and Maurice Wilkins played crucial roles in deciphering the helical struc ...

in 1953, marked the transition to the era of molecular genetics. From the 1950s onwards, biology has been vastly extended in the molecular

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and bioche ...

domain. The genetic code was cracked by Har Gobind Khorana, Robert W. Holley and Marshall Warren Nirenberg after DNA was understood to contain codons

The genetic code is the set of rules used by living cells to translate information encoded within genetic material ( DNA or RNA sequences of nucleotide triplets, or codons) into proteins. Translation is accomplished by the ribosome, which links ...

. Finally, the Human Genome Project

The Human Genome Project (HGP) was an international scientific research project with the goal of determining the base pairs that make up human DNA, and of identifying, mapping and sequencing all of the genes of the human genome from both a ...

was launched in 1990 with the goal of mapping the general human genome. This project was essentially completed in 2003, with further analysis still being published. The Human Genome Project was the first step in a globalized effort to incorporate accumulated knowledge of biology into a functional, molecular definition of the human body and the bodies of other organisms.

Chemical basis

Atoms and molecules

All organisms are made up ofchemical element

A chemical element is a species of atoms that have a given number of protons in their nuclei, including the pure substance consisting only of that species. Unlike chemical compounds, chemical elements cannot be broken down into simpler sub ...

s; oxygen, carbon, hydrogen, and nitrogen account for 96% of all organisms, with calcium, phosphorus, sulfur

Sulfur (or sulphur in British English) is a chemical element with the symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with a chemical formula ...

, sodium, chlorine, and magnesium constituting essentially all the remainder. Different elements can combine to form compounds such as water, which is fundamental to life. Biochemistry is the study of chemical processes

A chemical substance is a form of matter having constant chemical composition and characteristic properties. Some references add that chemical substance cannot be separated into its constituent elements by physical separation methods, i.e., wi ...

within and relating to living organisms. Molecular biology is the branch of biology that seeks to understand the molecular basis of biological activity in and between cells, including molecular

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and bioche ...

synthesis, modification, mechanisms, and interactions.

Water

Life arose from the Earth's first ocean, which was formed approximately 3.8 billion years ago. Since then, water continues to be the most abundant molecule in every organism. Water is important to life because it is an effective solvent, capable of dissolving solutes such as sodium and chloride ions or other small molecules to form an aqueous solution. Once dissolved in water, these solutes are more likely to come in contact with one another and therefore take part in chemical reactions that sustain life. In terms of its molecular structure, water is a small polar molecule with a bent shape formed by the polar covalent bonds of two hydrogen (H) atoms to one oxygen (O) atom (H2O). Because the O–H bonds are polar, the oxygen atom has a slight negative charge and the two hydrogen atoms have a slight positive charge. This polar property of water allows it to attract other water molecules via hydrogen bonds, which makes watercohesive

Cohesion may refer to:

* Cohesion (chemistry), the intermolecular attraction between like-molecules

* Cohesion (computer science), a measure of how well the lines of source code within a module work together

* Cohesion (geology), the part of shear ...

. Surface tension

Surface tension is the tendency of liquid surfaces at rest to shrink into the minimum surface area possible. Surface tension is what allows objects with a higher density than water such as razor blades and insects (e.g. water striders) to f ...

results from the cohesive force due to the attraction between molecules at the surface of the liquid. Water is also adhesive

Adhesive, also known as glue, cement, mucilage, or paste, is any non-metallic substance applied to one or both surfaces of two separate items that binds them together and resists their separation.

The use of adhesives offers certain advant ...

as it is able to adhere to the surface of any polar or charged non-water molecules.

Water is denser as a liquid

A liquid is a nearly incompressible fluid that conforms to the shape of its container but retains a (nearly) constant volume independent of pressure. As such, it is one of the four fundamental states of matter (the others being solid, gas, a ...

than it is as a solid (or ice). This unique property of water allows ice to float above liquid water such as ponds, lakes, and oceans, thereby insulating the liquid below from the cold air above. The lower density of ice compared to liquid water is due to the lower number of water molecules that form the crystal lattice structure of ice, which leaves a large amount of space between water molecules. In contrast, there is no crystal lattice structure in liquid water, which allows more water molecules to occupy the same amount of volume.

Water also has the capacity to absorb energy, giving it a higher specific heat capacity than other solvents such as ethanol. Thus, a large amount of energy is needed to break the hydrogen bonds between water molecules to convert liquid water into water vapor.

As a molecule, water is not completely stable as each water molecule continuously dissociates into hydrogen and hydroxyl ions before reforming into a water molecule again. In pure water, the number of hydrogen ions balances (or equals) the number of hydroxyl ions, resulting in a pH that is neutral.

Organic compounds

Organic compounds are molecules that contain carbon bonded to another element such as hydrogen. With the exception of water, nearly all the molecules that make up each organism contain carbon. Carbon can formcovalent bond

A covalent bond is a chemical bond that involves the sharing of electrons to form electron pairs between atoms. These electron pairs are known as shared pairs or bonding pairs. The stable balance of attractive and repulsive forces between atoms ...

s with up to four other atoms, enabling it to form diverse, large, and complex molecules. For example, a single carbon atom can form four single covalent bonds such as in methane, two double covalent bonds such as in carbon dioxide (), or a triple covalent bond such as in carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide ( chemical formula CO) is a colorless, poisonous, odorless, tasteless, flammable gas that is slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the si ...

(CO). Moreover, carbon can form very long chains of interconnecting carbon–carbon bonds such as octane

Octane is a hydrocarbon and an alkane with the chemical formula , and the condensed structural formula . Octane has many structural isomers that differ by the amount and location of branching in the carbon chain. One of these isomers, 2,2,4-Tri ...

or ring-like structures such as glucose.

The simplest form of an organic molecule is the hydrocarbon, which is a large family of organic compounds that are composed of hydrogen atoms bonded to a chain of carbon atoms. A hydrocarbon backbone can be substituted by other elements such as oxygen (O), hydrogen (H), phosphorus (P), and sulfur

Sulfur (or sulphur in British English) is a chemical element with the symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with a chemical formula ...

(S), which can change the chemical behavior of that compound. Groups of atoms that contain these elements (O-, H-, P-, and S-) and are bonded to a central carbon atom or skeleton are called functional groups. There are six prominent functional groups that can be found in organisms: amino group, carboxyl group, carbonyl group, hydroxyl group

In chemistry, a hydroxy or hydroxyl group is a functional group with the chemical formula and composed of one oxygen atom covalently bonded to one hydrogen atom. In organic chemistry, alcohols and carboxylic acids contain one or more hydroxy g ...

, phosphate group, and sulfhydryl group.

In 1953, the Miller-Urey experiment showed that organic compounds could be synthesized abiotically within a closed system mimicking the conditions of early Earth, thus suggesting that complex organic molecules could have arisen spontaneously in early Earth (see abiogenesis).

Macromolecules

Macromolecule

A macromolecule is a very large molecule important to biophysical processes, such as a protein or nucleic acid. It is composed of thousands of covalently bonded atoms. Many macromolecules are polymers of smaller molecules called monomers. The ...

s are large molecules made up of smaller molecular subunits that are joined. Small molecules such as sugars, amino acids, and nucleotides can act as single repeating units called monomers to form chain-like molecules called polymers via a chemical process called condensation

Condensation is the change of the state of matter from the gas phase into the liquid phase, and is the reverse of vaporization. The word most often refers to the water cycle. It can also be defined as the change in the state of water vapor to ...

. For example, amino acids can form polypeptide

Peptides (, ) are short chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. Long chains of amino acids are called proteins. Chains of fewer than twenty amino acids are called oligopeptides, and include dipeptides, tripeptides, and tetrapeptides.

A p ...

s whereas nucleotides can form strands of nucleic acid. Polymers make up three of the four macromolecules (polysaccharide

Polysaccharides (), or polycarbohydrates, are the most abundant carbohydrates found in food. They are long chain polymeric carbohydrates composed of monosaccharide units bound together by glycosidic linkages. This carbohydrate can react with wa ...

s, lipids, proteins, and nucleic acid

Nucleic acids are biopolymers, macromolecules, essential to all known forms of life. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomers made of three components: a 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main cl ...

s) that are found in all organisms. Each of these macromolecules plays a specialized role within any given cell.

Carbohydrates (or sugar

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose, fructose, and galactose. Compound sugars, also called disaccharides or double ...

) are molecules with the molecular formula , with ''n'' being the number of carbon-hydrate groups. They include monosaccharides (monomer), oligosaccharides (small polymers), and polysaccharides (large polymers). Monosaccharides can be linked together by glycosidic linkages, a type of covalent bond. When two monosaccharides such as glucose and fructose

Fructose, or fruit sugar, is a Ketose, ketonic monosaccharide, simple sugar found in many plants, where it is often bonded to glucose to form the disaccharide sucrose. It is one of the three dietary monosaccharides, along with glucose and galacto ...

are linked together, they can form a disaccharide such as sucrose

Sucrose, a disaccharide, is a sugar composed of glucose and fructose subunits. It is produced naturally in plants and is the main constituent of white sugar. It has the molecular formula .

For human consumption, sucrose is extracted and refined ...

. When many monosaccharides are linked together, they can form an oligosaccharide or a polysaccharide, depending on the number of monosaccharides. Polysaccharides can vary in function. Monosaccharides such as glucose can be a source of energy and some polysaccharides can serve as storage material that can be hydrolyzed

Hydrolysis (; ) is any chemical reaction in which a molecule of water breaks one or more chemical bonds. The term is used broadly for substitution, elimination, and solvation reactions in which water is the nucleophile.

Biological hydrolysis ...

to provide cells with sugar.

Lipids are the only class of macromolecules that are not made up of polymers. The most biologically important lipids are steroid

A steroid is a biologically active organic compound with four rings arranged in a specific molecular configuration. Steroids have two principal biological functions: as important components of cell membranes that alter membrane fluidity; and a ...

s, phospholipid

Phospholipids, are a class of lipids whose molecule has a hydrophilic "head" containing a phosphate group and two hydrophobic "tails" derived from fatty acids, joined by an alcohol residue (usually a glycerol molecule). Marine phospholipids typ ...

s, and fats. These lipids are organic compounds that are largely nonpolar and hydrophobic. Steroids are organic compounds that consist of four fused rings. Phospholipids consist of glycerol that is linked to a phosphate group and two hydrocarbon chains (or fatty acids). The glycerol and phosphate group together constitute the polar and hydrophilic (or head) region of the molecule whereas the fatty acids make up the nonpolar and hydrophobic (or tail) region. Thus, when in water, phospholipids tend to form a phospholipid bilayer whereby the hydrophobic heads face outwards to interact with water molecules. Conversely, the hydrophobic tails face inwards towards other hydrophobic tails to avoid contact with water.

Proteins are the most diverse of the macromolecules, which include enzymes, transport proteins, large

Proteins are the most diverse of the macromolecules, which include enzymes, transport proteins, large signaling

In signal processing, a signal is a function that conveys information about a phenomenon. Any quantity that can vary over space or time can be used as a signal to share messages between observers. The ''IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing'' ...

molecules, antibodies

An antibody (Ab), also known as an immunoglobulin (Ig), is a large, Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses. The antibody recognizes a unique molecule of the ...

, and structural proteins. The basic unit (or monomer) of a protein is an amino acid, which has a central carbon atom that is covalently bonded to a hydrogen atom, an amino group, a carboxyl group, and a side chain (or R-group, "R" for residue). There are twenty amino acids that make up the building blocks of proteins, with each amino acid having its own unique side chain. The polarity and charge of the side chains affect the solubility of amino acids. An amino acid with a side chain that is polar and electrically charged is soluble as it is hydrophilic whereas an amino acid with a side chain that lacks a charged or an electronegative atom is hydrophobic and therefore tends to coalesce rather than dissolve in water. Proteins have four distinct levels of organization (primary

Primary or primaries may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Music Groups and labels

* Primary (band), from Australia

* Primary (musician), hip hop musician and record producer from South Korea

* Primary Music, Israeli record label

Works

* ...

, secondary

Secondary may refer to: Science and nature

* Secondary emission, of particles

** Secondary electrons, electrons generated as ionization products

* The secondary winding, or the electrical or electronic circuit connected to the secondary winding i ...

, tertiary, and quartenary). The primary structure consists of a unique sequence of amino acids that are covalently linked together by peptide bond

In organic chemistry, a peptide bond is an amide type of covalent chemical bond linking two consecutive alpha-amino acids from C1 (carbon number one) of one alpha-amino acid and N2 (nitrogen number two) of another, along a peptide or protein cha ...

s. The side chains of the individual amino acids can then interact with each other, giving rise to the secondary structure of a protein. The two common types of secondary structures are alpha helices and beta sheet

The beta sheet, (β-sheet) (also β-pleated sheet) is a common motif of the regular protein secondary structure. Beta sheets consist of beta strands (β-strands) connected laterally by at least two or three backbone hydrogen bonds, forming a g ...

s. The folding of alpha helices and beta sheets gives a protein its three-dimensional or tertiary structure. Finally, multiple tertiary structures can combine to form the quaternary structure of a protein.

Nucleic acids are polymers made up of monomers called nucleotides. Their function is to store, transmit, and express hereditary information. Nucleotides consist of a phosphate group, a five-carbon sugar, and a nitrogenous base. Ribonucleotides, which contain ribose as the sugar, are the monomers of ribonucleic acid (RNA). In contrast, deoxyribonucleotides contain deoxyribose as the sugar and are constitute the monomers of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). RNA and DNA also differ with respect to one of their bases. There are two types of bases: purines and pyrimidine

Pyrimidine (; ) is an aromatic, heterocyclic, organic compound similar to pyridine (). One of the three diazines (six-membered heterocyclics with two nitrogen atoms in the ring), it has nitrogen atoms at positions 1 and 3 in the ring. The other ...

s. The purines include guanine (G) and adenine (A) whereas the pyrimidines consist of cytosine (C), uracil (U), and thymine (T). Uracil is used in RNA whereas thymine is used in DNA. Taken together, when the different sugar and bases are take into consideration, there are eight distinct nucleotides that can form two types of nucleic acids: DNA (A, G, C, and T) and RNA (A, G, C, and U).

Cells

Cell theory states that cells are the fundamental units of life, that all living things are composed of one or more cells, and that all cells arise from preexisting cells through cell division. Most cells are very small, with diameters ranging from 1 to 100micrometer Micrometer can mean:

* Micrometer (device), used for accurate measurements by means of a calibrated screw

* American spelling of micrometre

The micrometre ( international spelling as used by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures; ...

s and are therefore only visible under a light or electron microscope. There are generally two types of cells: eukaryotic cells, which contain a nucleus, and prokaryotic cells, which do not. Prokaryotes are single-celled organisms such as bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were am ...

, whereas eukaryotes can be single-celled or multicellular. In multicellular organisms, every cell in the organism's body is derived ultimately from a single cell Single cell and similar can mean:

Biology

*Single-cell organism

*Single-cell protein

*Single-cell recording, a neuro-electric monitoring technique

*Single-cell sequencing

**Single cell epigenomics

*Single-cell transcriptomics

Other

* Single-cell th ...

in a fertilized egg

An egg is an organic vessel grown by an animal to carry a possibly fertilized egg cell (a zygote) and to incubate from it an embryo within the egg until the embryo has become an animal fetus that can survive on its own, at which point the a ...

.

Cell structure

phospholipid

Phospholipids, are a class of lipids whose molecule has a hydrophilic "head" containing a phosphate group and two hydrophobic "tails" derived from fatty acids, joined by an alcohol residue (usually a glycerol molecule). Marine phospholipids typ ...

s to maintain their fluidity at various temperatures. Cell membranes are semipermeable

Semipermeable membrane is a type of biological or synthetic, polymeric membrane that will allow certain molecules or ions to pass through it by osmosis. The rate of passage depends on the pressure, concentration, and temperature of the molecul ...

, allowing small molecules such as oxygen, carbon dioxide, and water to pass through while restricting the movement of larger molecules and charged particles such as ions. Cell membranes also contains membrane proteins, including integral membrane proteins that go across the membrane serving as membrane transporter

A membrane transport protein (or simply transporter) is a membrane protein involved in the movement of ions, small molecules, and macromolecules, such as another protein, across a biological membrane. Transport proteins are integral transmembrane ...

s, and peripheral proteins that loosely attach to the outer side of the cell membrane, acting as enzymes shaping the cell. Cell membranes are involved in various cellular processes such as cell adhesion

Cell adhesion is the process by which cells interact and attach to neighbouring cells through specialised molecules of the cell surface. This process can occur either through direct contact between cell surfaces such as cell junctions or indir ...

, storing electrical energy, and cell signalling

In biology, cell signaling (cell signalling in British English) or cell communication is the ability of a cell to receive, process, and transmit signals with its environment and with itself. Cell signaling is a fundamental property of all cellula ...

and serve as the attachment surface for several extracellular structures such as a cell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer surrounding some types of cells, just outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. It provides the cell with both structural support and protection, and also acts as a filtering mech ...

, glycocalyx, and cytoskeleton

The cytoskeleton is a complex, dynamic network of interlinking protein filaments present in the cytoplasm of all cells, including those of bacteria and archaea. In eukaryotes, it extends from the cell nucleus to the cell membrane and is comp ...

.

biomolecule

A biomolecule or biological molecule is a loosely used term for molecules present in organisms that are essential to one or more typically biological processes, such as cell division, morphogenesis, or development. Biomolecules include large ...

s such as proteins and nucleic acid

Nucleic acids are biopolymers, macromolecules, essential to all known forms of life. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomers made of three components: a 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main cl ...

s.Cell Movements and the Shaping of the Vertebrate Bodyin Chapter 21 of

Molecular Biology of the Cell

'' fourth edition, edited by Bruce Alberts (2002) published by Garland Science.

The Alberts text discusses how the "cellular building blocks" move to shape developing

embryo

An embryo is an initial stage of development of a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male spe ...

s. It is also common to describe small molecules such as amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha ...

s asmolecular building blocks

". In addition to biomolecules, eukaryotic cells have specialized structures called

organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as organs are to the body, hence ''organelle,'' the ...

s that have their own lipid bilayers or are spatially units. These organelles include the cell nucleus

The cell nucleus (pl. nuclei; from Latin or , meaning ''kernel'' or ''seed'') is a membrane-bound organelle found in eukaryotic cells. Eukaryotic cells usually have a single nucleus, but a few cell types, such as mammalian red blood cells ...

, which contains most of the cell's DNA, or mitochondria

A mitochondrion (; ) is an organelle found in the Cell (biology), cells of most Eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and Fungus, fungi. Mitochondria have a double lipid bilayer, membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosi ...

, which generates adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to power cellular processes. Other organelles such as endoplasmic reticulum

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is, in essence, the transportation system of the eukaryotic cell, and has many other important functions such as protein folding. It is a type of organelle made up of two subunits – rough endoplasmic reticulum ( ...

and Golgi apparatus play a role in the synthesis and packaging of proteins, respectively. Biomolecules such as proteins can be engulfed by lysosomes, another specialized organelle. Plant cell

Plant cells are the cells present in green plants, photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Their distinctive features include primary cell walls containing cellulose, hemicelluloses and pectin, the presence of plastids with the capabi ...

s have additional organelles that distinguish them from animal cells such as a cell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer surrounding some types of cells, just outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. It provides the cell with both structural support and protection, and also acts as a filtering mech ...

that provides support for the plant cell, chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant and algal cells. The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll captures the energy from sunlight, converts it, and stores it in ...

s that harvest sunlight energy to produce sugar, and vacuoles that provide storage and structural support as well as being involved in reproduction and breakdown of plant seeds. Eukaryotic cells also have cytoskeleton that is made up of microtubule

Microtubules are polymers of tubulin that form part of the cytoskeleton and provide structure and shape to eukaryotic cells. Microtubules can be as long as 50 micrometres, as wide as 23 to 27 nm and have an inner diameter between 11 an ...

s, intermediate filament

Intermediate filaments (IFs) are cytoskeletal structural components found in the cells of vertebrates, and many invertebrates. Homologues of the IF protein have been noted in an invertebrate, the cephalochordate ''Branchiostoma''.

Intermedia ...

s, and microfilaments, all of which provide support for the cell and are involved in the movement of the cell and its organelles. In terms of their structural composition, the microtubules are made up of tubulin (e.g., α-tubulin

Tubulin in molecular biology can refer either to the tubulin protein superfamily of globular proteins, or one of the member proteins of that superfamily. α- and β-tubulins polymerize into microtubules, a major component of the eukaryotic cytoske ...

and β-tubulin

Tubulin in molecular biology can refer either to the tubulin protein superfamily of globular proteins, or one of the member proteins of that superfamily. α- and β-tubulins polymerize into microtubules, a major component of the eukaryotic cytoske ...

whereas intermediate filaments are made up of fibrous proteins. Microfilaments are made up of actin

Actin is a protein family, family of Globular protein, globular multi-functional proteins that form microfilaments in the cytoskeleton, and the thin filaments in myofibril, muscle fibrils. It is found in essentially all Eukaryote, eukaryotic cel ...

molecules that interact with other strands of proteins.

Metabolism

nucleic acid

Nucleic acids are biopolymers, macromolecules, essential to all known forms of life. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomers made of three components: a 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main cl ...

s, and some carbohydrates; and the elimination of metabolic waste

Metabolic wastes or excrements are substances left over from metabolic processes (such as cellular respiration) which cannot be used by the organism (they are surplus or toxic), and must therefore be excreted. This includes nitrogen compounds, ...

s. These enzyme-catalyzed reactions allow organisms to grow and reproduce, maintain their structures, and respond to their environments. Metabolic reactions may be categorized as catabolic—the breaking down of compounds (for example, the breaking down of glucose to pyruvate by cellular respiration); or anabolic—the building up (synthesis

Synthesis or synthesize may refer to:

Science Chemistry and biochemistry

*Chemical synthesis, the execution of chemical reactions to form a more complex molecule from chemical precursors

** Organic synthesis, the chemical synthesis of organ ...

) of compounds (such as proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, and nucleic acids). Usually, catabolism releases energy, and anabolism consumes energy.

The chemical reactions of metabolism are organized into metabolic pathways, in which one chemical is transformed through a series of steps into another chemical, each step being facilitated by a specific enzyme. Enzymes are crucial to metabolism because they allow organisms to drive desirable reactions that require energy that will not occur by themselves, by coupling them to spontaneous reactions that release energy. Enzymes act as catalysts—they allow a reaction to proceed more rapidly without being consumed by it—by reducing the amount of activation energy needed to convert reactants into products. Enzymes also allow the regulation of the rate of a metabolic reaction, for example in response to changes in the cell's environment or to signals from other cells.

Cellular respiration

Cellular respiration is a set ofmetabolic

Metabolism (, from el, μεταβολή ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cell ...

reactions and processes that take place in the cells of organisms to convert chemical energy

Chemical energy is the energy of chemical substances that is released when they undergo a chemical reaction and transform into other substances. Some examples of storage media of chemical energy include batteries, Schmidt-Rohr, K. (2018). "How ...

from nutrients into adenosine triphosphate (ATP), and then release waste products. The reactions involved in respiration are catabolic reactions, which break large molecules into smaller ones, releasing energy. Respiration is one of the key ways a cell releases chemical energy to fuel cellular activity. The overall reaction occurs in a series of biochemical steps, some of which are redox reactions. Although cellular respiration is technically a combustion reaction

Combustion, or burning, is a high-temperature exothermic redox chemical reaction between a fuel (the reductant) and an oxidant, usually atmospheric oxygen, that produces oxidized, often gaseous products, in a mixture termed as smoke. Combusti ...

, it clearly does not resemble one when it occurs in a cell because of the slow, controlled release of energy from the series of reactions.

Sugar in the form of glucose is the main nutrient used by animal and plant cells in respiration. Cellular respiration involving oxygen is called aerobic respiration, which has four stages: glycolysis

Glycolysis is the metabolic pathway that converts glucose () into pyruvate (). The free energy released in this process is used to form the high-energy molecules adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH ...

, citric acid cycle (or Krebs cycle), electron transport chain

An electron transport chain (ETC) is a series of protein complexes and other molecules that transfer electrons from electron donors to electron acceptors via redox reactions (both reduction and oxidation occurring simultaneously) and couples th ...

, and oxidative phosphorylation

Oxidative phosphorylation (UK , US ) or electron transport-linked phosphorylation or terminal oxidation is the metabolic pathway in which cells use enzymes to oxidize nutrients, thereby releasing chemical energy in order to produce adenosine tri ...

. Glycolysis is a metabolic process that occurs in the cytoplasm whereby glucose is converted into two pyruvate

Pyruvic acid (CH3COCOOH) is the simplest of the alpha-keto acids, with a carboxylic acid and a ketone functional group. Pyruvate, the conjugate base, CH3COCOO−, is an intermediate in several metabolic pathways throughout the cell.

Pyruvic aci ...

s, with two net molecules of ATP being produced at the same time. Each pyruvate is then oxidized into acetyl-CoA

Acetyl-CoA (acetyl coenzyme A) is a molecule that participates in many biochemical reactions in protein, carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. Its main function is to deliver the acetyl group to the citric acid cycle (Krebs cycle) to be oxidized for ...

by the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex

Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC) is a complex of three enzymes that converts pyruvate into acetyl-CoA by a process called pyruvate decarboxylation. Acetyl-CoA may then be used in the citric acid cycle to carry out cellular respiration, and thi ...

, which also generates NADH and carbon dioxide. Acetyl-Coa enters the citric acid cycle, which takes places inside the mitochondrial matrix. At the end of the cycle, the total yield from 1 glucose (or 2 pyruvates) is 6 NADH, 2 FADH2, and 2 ATP molecules. Finally, the next stage is oxidative phosphorylation, which in eukaryotes, occurs in the mitochondrial cristae. Oxidative phosphorylation comprises the electron transport chain

An electron transport chain (ETC) is a series of protein complexes and other molecules that transfer electrons from electron donors to electron acceptors via redox reactions (both reduction and oxidation occurring simultaneously) and couples th ...

, which is a series of four protein complexes that transfer electrons from one complex to another, thereby releasing energy from NADH and FADH2 that is coupled to the pumping of protons (hydrogen ions) across the inner mitochondrial membrane ( chemiosmosis), which generates a proton motive force. Energy from the proton motive force drives the enzyme ATP synthase

ATP synthase is a protein that catalyzes the formation of the energy storage molecule adenosine triphosphate (ATP) using adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and inorganic phosphate (Pi). It is classified under ligases as it changes ADP by the formation ...

to synthesize more ATPs by phosphorylating

In chemistry, phosphorylation is the attachment of a phosphate group to a molecule or an ion. This process and its inverse, dephosphorylation, are common in biology and could be driven by natural selection. Text was copied from this source, whi ...

ADP

Adp or ADP may refer to:

Aviation

* Aéroports de Paris, airport authority for the Parisian region in France

* Aeropuertos del Perú, airport operator for airports in northern Peru

* SLAF Anuradhapura, an airport in Sri Lanka

* Ampara Air ...

s. The transfer of electrons terminates with molecular oxygen being the final electron acceptor

An electron acceptor is a chemical entity that accepts electrons transferred to it from another compound. It is an oxidizing agent that, by virtue of its accepting electrons, is itself reduced in the process. Electron acceptors are sometimes mista ...

.

If oxygen were not present, pyruvate would not be metabolized by cellular respiration but undergoes a process of fermentation

Fermentation is a metabolic process that produces chemical changes in organic substrates through the action of enzymes. In biochemistry, it is narrowly defined as the extraction of energy from carbohydrates in the absence of oxygen. In food ...

. The pyruvate is not transported into the mitochondrion but remains in the cytoplasm, where it is converted to waste products that may be removed from the cell. This serves the purpose of oxidizing the electron carriers so that they can perform glycolysis again and removing the excess pyruvate. Fermentation oxidizes NADH to NAD+ so it can be re-used in glycolysis. In the absence of oxygen, fermentation prevents the buildup of NADH in the cytoplasm and provides NAD+ for glycolysis. This waste product varies depending on the organism. In skeletal muscles, the waste product is lactic acid. This type of fermentation is called lactic acid fermentation. In strenuous exercise, when energy demands exceed energy supply, the respiratory chain cannot process all of the hydrogen atoms joined by NADH. During anaerobic glycolysis, NAD+ regenerates when pairs of hydrogen combine with pyruvate to form lactate. Lactate formation is catalyzed by lactate dehydrogenase in a reversible reaction. Lactate can also be used as an indirect precursor for liver glycogen. During recovery, when oxygen becomes available, NAD+ attaches to hydrogen from lactate to form ATP. In yeast, the waste products are ethanol and carbon dioxide. This type of fermentation is known as alcoholic or ethanol fermentation. The ATP generated in this process is made by substrate-level phosphorylation

Substrate-level phosphorylation is a metabolism reaction that results in the production of ATP or GTP by the transfer of a phosphate group from a substrate directly to ADP or GDP. Transferring from a higher energy (whether phosphate group atta ...

, which does not require oxygen.

Photosynthesis

chemical energy

Chemical energy is the energy of chemical substances that is released when they undergo a chemical reaction and transform into other substances. Some examples of storage media of chemical energy include batteries, Schmidt-Rohr, K. (2018). "How ...

that can later be released to fuel the organism's metabolic activities via cellular respiration. This chemical energy is stored in carbohydrate molecules, such as sugar

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose, fructose, and galactose. Compound sugars, also called disaccharides or double ...

s, which are synthesized from carbon dioxide and water. In most cases, oxygen is also released as a waste product. Most plants, algae

Algae (; singular alga ) is an informal term for a large and diverse group of photosynthetic eukaryotic organisms. It is a polyphyletic grouping that includes species from multiple distinct clades. Included organisms range from unicellular mic ...

, and cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria (), also known as Cyanophyta, are a phylum of gram-negative bacteria that obtain energy via photosynthesis. The name ''cyanobacteria'' refers to their color (), which similarly forms the basis of cyanobacteria's common name, blu ...

perform photosynthesis, which is largely responsible for producing and maintaining the oxygen content of the Earth's atmosphere, and supplies most of the energy necessary for life on Earth.

Photosynthesis has four stages: Light absorption, electron transport, ATP synthesis, and carbon fixation

Biological carbon fixation or сarbon assimilation is the process by which inorganic carbon (particularly in the form of carbon dioxide) is converted to organic compounds by living organisms. The compounds are then used to store energy and as ...

. Light absorption is the initial step of photosynthesis whereby light energy is absorbed by chlorophyll

Chlorophyll (also chlorophyl) is any of several related green pigments found in cyanobacteria and in the chloroplasts of algae and plants. Its name is derived from the Greek words , ("pale green") and , ("leaf"). Chlorophyll allow plants to a ...

pigments attached to proteins in the thylakoid membranes. The absorbed light energy is used to remove electrons from a donor (water) to a primary electron acceptor, a quinone

The quinones are a class of organic compounds that are formally "derived from aromatic compounds

designated as Q. In the second stage, electrons move from the quinone primary electron acceptor through a series of electron carriers until they reach a final electron acceptor, which is usually the oxidized form of NADP+, which is reduced to NADPH, a process that takes place in a protein complex called photosystem I (PSI). The transport of electrons is coupled to the movement of protons (or hydrogen) from the stroma to the thylakoid membrane, which forms a pH gradient across the membrane as hydrogen becomes more concentrated in the lumen than in the stroma. This is analogous to the proton-motive force generated across the inner mitochondrial membrane in aerobic respiration.

During the third stage of photosynthesis, the movement of protons down their concentration gradients from the thylakoid lumen to the stroma through the ATP synthase is coupled to the synthesis of ATP by that same ATP synthase. The NADPH and ATPs generated by the light-dependent reactions in the second and third stages, respectively, provide the energy and electrons to drive the synthesis of glucose by fixing atmospheric carbon dioxide into existing organic carbon compounds, such as ribulose bisphosphate (RuBP) in a sequence of light-independent (or dark) reactions called the uch as benzene or naphthalene

Uch ( pa, ;

ur, ), frequently referred to as Uch Sharīf ( pa, ;

ur, ; ''"Noble Uch"''), is a historic city in the southern part of Pakistan's Punjab province. Uch may have been founded as Alexandria on the Indus, a town founded by Alexand ...

by conversion of an even number of –CH= groups into –C(=O)– groups with any necessary rearrangement of double ...Calvin cycle

The Calvin cycle, light-independent reactions, bio synthetic phase, dark reactions, or photosynthetic carbon reduction (PCR) cycle of photosynthesis is a series of chemical reactions that convert carbon dioxide and hydrogen-carrier compounds into ...

.

Cell signaling

Cell signaling (or communication) is the ability of cells to receive, process, and transmit signals with its environment and with itself. Signals can be non-chemical such as light,electrical impulses

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter that has a property of electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as described by ...

, and heat, or chemical signals (or ligands) that interact with receptors, which can be found embedded in the cell membrane of another cell or located deep inside a cell. There are generally four types of chemical signals: autocrine, paracrine, juxtacrine, and hormones. In autocrine signaling, the ligand affects the same cell that releases it. Tumor cells, for example, can reproduce uncontrollably because they release signals that initiate their own self-division. In paracrine signaling, the ligand diffuses to nearby cells and affects them. For example, brain cells called neurons release ligands called neurotransmitter

A neurotransmitter is a signaling molecule secreted by a neuron to affect another cell across a synapse. The cell receiving the signal, any main body part or target cell, may be another neuron, but could also be a gland or muscle cell.

Neuro ...

s that diffuse across a synaptic cleft to bind with a receptor on an adjacent cell such as another neuron or muscle cell

A muscle cell is also known as a myocyte when referring to either a cardiac muscle cell (cardiomyocyte), or a smooth muscle cell as these are both small cells. A skeletal muscle cell is long and threadlike with many nuclei and is called a muscl ...

. In juxtacrine signaling, there is direct contact between the signaling and responding cells. Finally, hormones are ligands that travel through the circulatory systems of animals or vascular systems of plants to reach their target cells. Once a ligand binds with a receptor, it can influence the behavior of another cell, depending on the type of receptor. For instance, neurotransmitters that bind with an inotropic receptor can alter the excitability of a target cell. Other types of receptors include protein kinase receptors (e.g., receptor for the hormone insulin

Insulin (, from Latin ''insula'', 'island') is a peptide hormone produced by beta cells of the pancreatic islets encoded in humans by the ''INS'' gene. It is considered to be the main anabolic hormone of the body. It regulates the metabolism o ...

) and G protein-coupled receptors. Activation of G protein-coupled receptors can initiate second messenger

Second messengers are intracellular signaling molecules released by the cell in response to exposure to extracellular signaling molecules—the first messengers. (Intercellular signals, a non-local form or cell signaling, encompassing both first me ...

cascades. The process by which a chemical or physical signal is transmitted through a cell as a series of molecular events is called signal transduction

Signal transduction is the process by which a chemical or physical signal is transmitted through a cell as a series of molecular events, most commonly protein phosphorylation catalyzed by protein kinases, which ultimately results in a cellula ...

Cell cycle

organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as organs are to the body, hence ''organelle,'' the ...

s, and the subsequent partitioning of its cytoplasm into two daughter cells in a process called cell division. In eukaryote

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

s (i.e., animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Kingdom (biology), biological kingdom Animalia. With few exceptions, animals Heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, are Motilit ...

, plant, fungal, and protist cells), there are two distinct types of cell division: mitosis

In cell biology, mitosis () is a part of the cell cycle in which replicated chromosomes are separated into two new nuclei. Cell division by mitosis gives rise to genetically identical cells in which the total number of chromosomes is mainta ...

and meiosis. Mitosis is part of the cell cycle, in which replicated chromosomes are separated into two new nuclei. Cell division gives rise to genetically identical cells in which the total number of chromosomes is maintained. In general, mitosis (division of the nucleus) is preceded by the S stage of interphase (during which the DNA is replicated) and is often followed by telophase and cytokinesis; which divides the cytoplasm, organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as organs are to the body, hence ''organelle,'' the ...

s and cell membrane of one cell into two new cells

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery w ...

containing roughly equal shares of these cellular components. The different stages of mitosis all together define the mitotic phase of an animal cell cycle—the division of the mother cell into two genetically identical daughter cells. The cell cycle is a vital process by which a single-celled fertilized egg develops into a mature organism, as well as the process by which hair

Hair is a protein filament that grows from follicles found in the dermis. Hair is one of the defining characteristics of mammals.

The human body, apart from areas of glabrous skin, is covered in follicles which produce thick terminal and f ...

, skin, blood cells, and some internal organs

In biology, an organ is a collection of tissues joined in a structural unit to serve a common function. In the hierarchy of life, an organ lies between tissue and an organ system. Tissues are formed from same type cells to act together in a ...

are renewed. After cell division, each of the daughter cells begin the interphase of a new cycle. In contrast to mitosis, meiosis results in four haploid daughter cells by undergoing one round of DNA replication followed by two divisions. Homologous chromosomes are separated in the first division ( meiosis I), and sister chromatids are separated in the second division ( meiosis II). Both of these cell division cycles are used in the process of sexual reproduction at some point in their life cycle. Both are believed to be present in the last eukaryotic common ancestor.

Prokaryotes (i.e., archaea

Archaea ( ; singular archaeon ) is a domain of single-celled organisms. These microorganisms lack cell nuclei and are therefore prokaryotes. Archaea were initially classified as bacteria, receiving the name archaebacteria (in the Archaeb ...

and bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were am ...

) can also undergo cell division (or binary fission). Unlike the processes of mitosis

In cell biology, mitosis () is a part of the cell cycle in which replicated chromosomes are separated into two new nuclei. Cell division by mitosis gives rise to genetically identical cells in which the total number of chromosomes is mainta ...

and meiosis in eukaryotes, binary fission takes in prokaryotes takes place without the formation of a spindle apparatus on the cell. Before binary fission, DNA in the bacterium is tightly coiled. After it has uncoiled and duplicated, it is pulled to the separate poles of the bacterium as it increases the size to prepare for splitting. Growth of a new cell wall begins to separate the bacterium (triggered by FtsZ polymerization and "Z-ring" formation) The new cell wall (septum

In biology, a septum (Latin for ''something that encloses''; plural septa) is a wall, dividing a cavity or structure into smaller ones. A cavity or structure divided in this way may be referred to as septate.

Examples

Human anatomy

* Interatri ...

) fully develops, resulting in the complete split of the bacterium. The new daughter cells have tightly coiled DNA rods, ribosome

Ribosomes ( ) are macromolecular machines, found within all cells, that perform biological protein synthesis (mRNA translation). Ribosomes link amino acids together in the order specified by the codons of messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules to ...

s, and plasmid

A plasmid is a small, extrachromosomal DNA molecule within a cell that is physically separated from chromosomal DNA and can replicate independently. They are most commonly found as small circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in bacteria; how ...

s.

Genetics

Inheritance

Mendelian Principles

Exceptions to this rule include penetrance and expressivity. Mendel noted that during gamete formation, the alleles for each gene segregate from each other so that each gamete carries only one allele for each gene, which is stated by his law of segregation.

Heterozygotic

Zygosity (the noun, zygote, is from the Greek "yoked," from "yoke") () is the degree to which both copies of a chromosome or gene have the same genetic sequence. In other words, it is the degree of similarity of the alleles in an organism.

Mo ...

individuals produce gametes with an equal frequency of two alleles. Finally, Mendel formulated the law of independent assortment, which states that genes of different traits can segregate independently during the formation of gametes, i.e., genes are unlinked. An exception to this rule would include traits that are sex-linked

Sex linked describes the sex-specific patterns of inheritance and presentation when a gene mutation ( allele) is present on a sex chromosome (allosome) rather than a non-sex chromosome (autosome). In humans, these are termed X-linked rece ...

. Test crosses can be performed to experimentally determine the underlying genotype

The genotype of an organism is its complete set of genetic material. Genotype can also be used to refer to the alleles or variants an individual carries in a particular gene or genetic location. The number of alleles an individual can have in a ...

of an organism with a dominant phenotype. A Punnett square

The Punnett square is a square diagram that is used to predict the genotypes of a particular cross or breeding experiment. It is named after Reginald C. Punnett, who devised the approach in 1905. The diagram is used by biologists to determine ...

can be used to predict the results of a test cross. The chromosome theory of inheritance

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins are ...

, which states that genes are found on chromosomes, was supported by Thomas Morgans's experiments with fruit flies, which established the sex linkage between eye color and sex in these insects. In humans and other mammals (e.g., dogs), it is not feasible or practical to conduct test cross experiments. Instead, pedigree