Benjamin Silliman on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

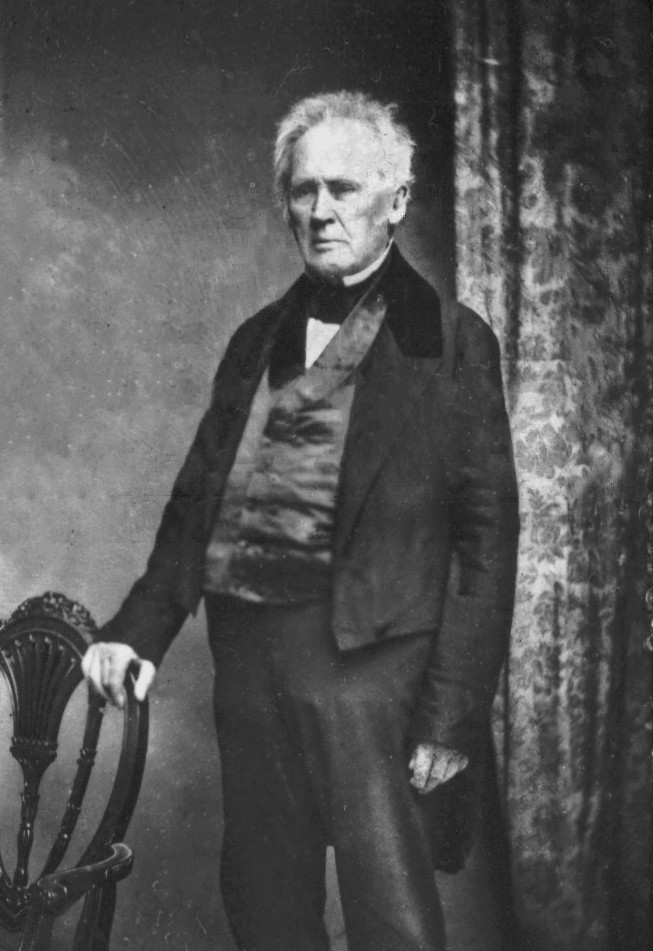

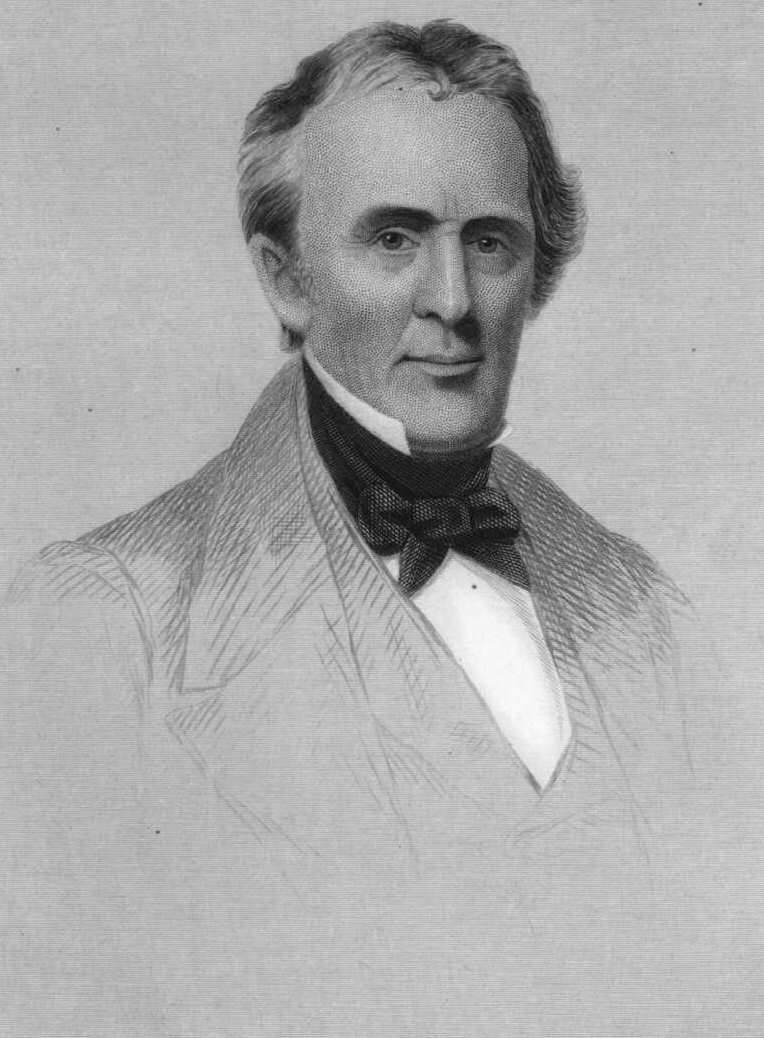

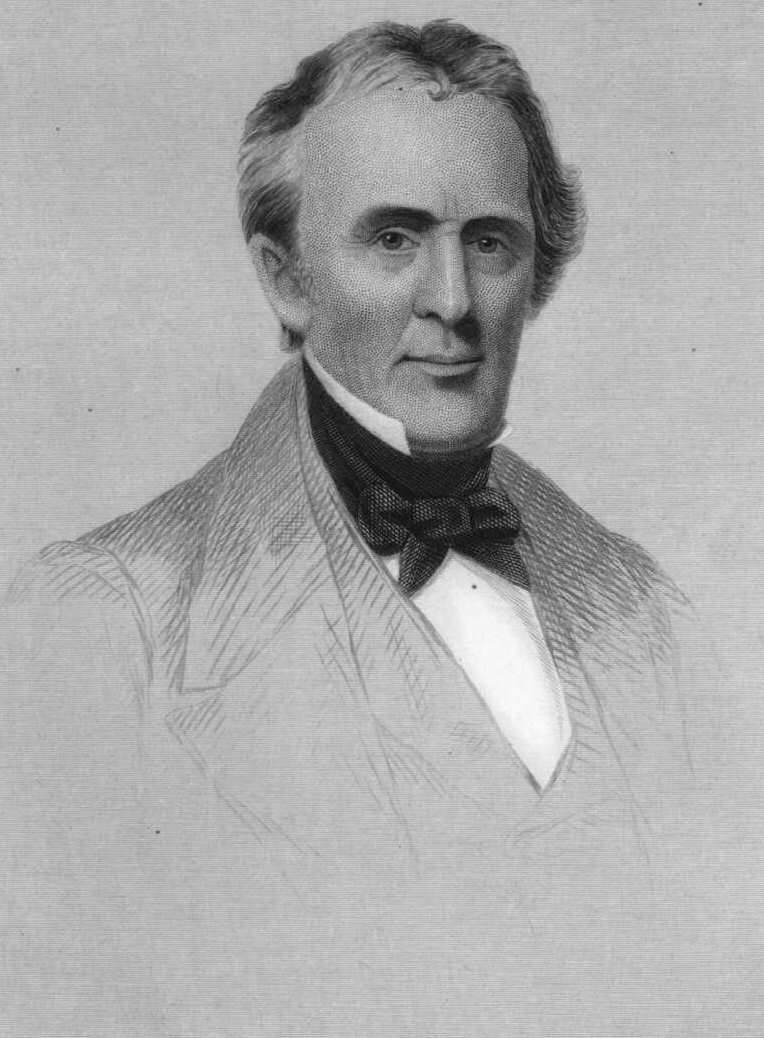

Benjamin Silliman (August 8, 1779 – November 24, 1864) was an early American

Silliman was born in a tavern in North Stratford, now

Silliman was born in a tavern in North Stratford, now

Returning to

Returning to

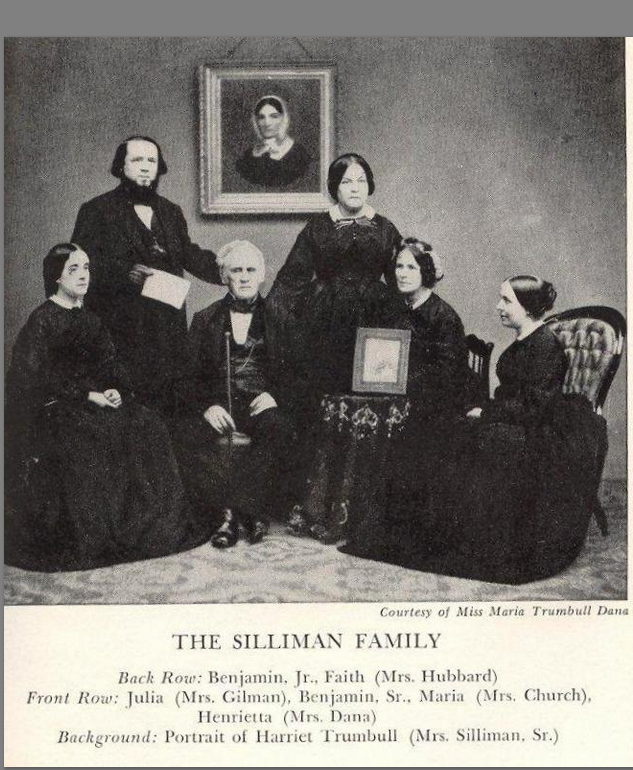

His first marriage was on September 17, 1809, to Harriet Trumbull, daughter of Connecticut governor

His first marriage was on September 17, 1809, to Harriet Trumbull, daughter of Connecticut governor

American Antiquarian Society Members Directory

/ref> and an Associate Fellow of the

Yale University on Silliman

The Yale Standard on SillimanSillimanite

{{DEFAULTSORT:Silliman, Benjamin 1779 births 1864 deaths Alumni of the University of Edinburgh American chemists American mineralogists Burials at Grove Street Cemetery Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Members of the American Antiquarian Society Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences Yale University alumni Yale University faculty People from Trumbull, Connecticut Silliman family

chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties. Chemists carefully describe ...

and science educator

Science education is the teaching and learning of science to school children, college students, or adults within the general public. The field of science education includes work in science content, science process (the scientific method), some ...

. He was one of the first American professors of science, at Yale College

Yale College is the undergraduate college of Yale University. Founded in 1701, it is the original school of the university. Although other Yale schools were founded as early as 1810, all of Yale was officially known as Yale College until 1887, ...

, the first person to use the process of fractional distillation

Fractional distillation is the separation of a mixture into its component parts, or fractions. Chemical compounds are separated by heating them to a temperature at which one or more fractions of the mixture will vaporize. It uses distillation to ...

in America, and a founder of the ''American Journal of Science

The ''American Journal of Science'' (''AJS'') is the United States of America's longest-running scientific journal, having been published continuously since its conception in 1818 by Professor Benjamin Silliman, who edited and financed it himsel ...

'', the oldest continuously published scientific journal in the United States.

Early life

Silliman was born in a tavern in North Stratford, now

Silliman was born in a tavern in North Stratford, now Trumbull Trumbull may refer to:

Places United States

* Trumbull County, Ohio

** Trumbull Township, Ashtabula County, Ohio

* Trumbull, Connecticut

* Trumbull, Nebraska

* Fort Trumbull, Connecticut

* Mount Trumbull Wilderness in Arizona

People Surname

* ...

, Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its cap ...

, to Mary (Fish) Silliman (widow of John Noyes) and General Gold Selleck Silliman. He was born in August 1779, several months after British forces took his father prisoner and his mother had fled their home in Fairfield, Connecticut, to escape 2,000 British troops who burned Fairfield center to the ground.

Silliman was educated at Yale, receiving a B.A. degree in 1796 and a M.A. in 1799. He studied law with Simeon Baldwin

Simeon Baldwin (December 14, 1761 – May 26, 1851) was son-in-law of Roger Sherman, father of Connecticut Governor and US Senator Roger Sherman Baldwin, grandfather of Connecticut Governor & Chief Justice Simeon Eben Baldwin and great-grand ...

from 1798 to 1799 and became a tutor at Yale from 1799 to 1802. He was admitted to the bar in 1802. That same year he was hired by Yale President Timothy Dwight IV as a professor of chemistry and natural history. Silliman, who had never studied chemistry, prepared for the job by studying chemistry with Professor James Woodhouse at the University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (also known as Penn or UPenn) is a private research university in Philadelphia. It is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and is ranked among the highest-regarded universit ...

in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

. In 1804, he delivered his first lectures in chemistry, which were also the first science lectures ever given at Yale. In 1805, he traveled to University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

for further study.

Career

Returning to

Returning to New Haven

New Haven is a city in the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is located on New Haven Harbor on the northern shore of Long Island Sound in New Haven County, Connecticut and is part of the New York City metropolitan area. With a population of 134,023 ...

, he studied its geology

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Ea ...

. His chemical analysis of a meteorite

A meteorite is a solid piece of debris from an object, such as a comet, asteroid, or meteoroid, that originates in outer space and survives its passage through the atmosphere to reach the surface of a planet or moon. When the original object en ...

that fell in 1807 near Weston, Connecticut, was the first published scientific account of an American meteorite. He lectured publicly at New Haven in 1808 and came to discover many of the constituent elements of many mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid chemical compound with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. ...

s. Some time around 1818, Ephraim Lane took some samples of rocks he found at an area called Saganawamps, now a part of the Old Mine Park Archeological Site

The Old Mine Park Archaeological Site is a historic site in the Long Hill section of Trumbull, Connecticut, United States. It was mined from 1828 to 1920 and during 1942-1946, and has been incorporated in a municipal park. It was added to the N ...

in Trumbull, Connecticut, to Silliman for identification. Silliman reported in his new ''American Journal of Science

The ''American Journal of Science'' (''AJS'') is the United States of America's longest-running scientific journal, having been published continuously since its conception in 1818 by Professor Benjamin Silliman, who edited and financed it himsel ...

'', a publication covering all the natural sciences but with an emphasis on geology, that he had identified tungsten

Tungsten, or wolfram, is a chemical element with the symbol W and atomic number 74. Tungsten is a rare metal found naturally on Earth almost exclusively as compounds with other elements. It was identified as a new element in 1781 and first isol ...

, tellurium

Tellurium is a chemical element with the symbol Te and atomic number 52. It is a brittle, mildly toxic, rare, silver-white metalloid. Tellurium is chemically related to selenium and sulfur, all three of which are chalcogens. It is occasionally fo ...

, topaz

Topaz is a silicate mineral of aluminium and fluorine with the chemical formula Al Si O( F, OH). It is used as a gemstone in jewelry and other adornments. Common topaz in its natural state is colorless, though trace element impurities can ma ...

and fluorite

Fluorite (also called fluorspar) is the mineral form of calcium fluoride, CaF2. It belongs to the halide minerals. It crystallizes in isometric cubic habit, although octahedral and more complex isometric forms are not uncommon.

The Mohs sca ...

in the rocks. He played a major role in the discoveries of the first fossil fishes found in the United States. In 1837, the first (and at the time only) prismatic barite ore of tungsten

Tungsten, or wolfram, is a chemical element with the symbol W and atomic number 74. Tungsten is a rare metal found naturally on Earth almost exclusively as compounds with other elements. It was identified as a new element in 1781 and first isol ...

in the United States was discovered at the mine. The mineral sillimanite

Sillimanite is an aluminosilicate mineral with the chemical formula Al2SiO5. Sillimanite is named after the American chemist Benjamin Silliman (1779–1864). It was first described in 1824 for an occurrence in Chester, Connecticut.

Occurrence ...

was named after Silliman in 1850. Upon the founding of the Medical School

A medical school is a tertiary educational institution, or part of such an institution, that teaches medicine, and awards a professional degree for physicians. Such medical degrees include the Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS, MB ...

, he also taught there as one of the founding faculty members.

In 1833 he discussed the relationship of Flood geology

Flood geology (also creation geology or diluvial geology) is a pseudoscientific attempt to interpret and reconcile geological features of the Earth in accordance with a literal belief in the global flood described in Genesis 6–8. In the ...

to the Genesis account, and also wrote about this topic in 1840.

Silliman was an early supporter of coeducation in the Ivy League. Although Yale wouldn't admit women as students until over 100 years later, he allowed young women into his lecture classes. His efforts convinced Frederick Barnard, later President of Columbia College, that women ought to be admitted as students. "The elder Silliman, during the entire period of his distinguished career as a Professor of Chemistry, Geology and Mineralogy in Yale College, was accustomed every year to admit to his lecture-courses classes of young women from the schools of New Haven. In that institution the undersigned had an opportunity to observe, as a student, the effect of the practice, similar to that which he afterward created for himself in Alabama, as a teacher. The results in both instances, so far as they went, were good; and they went far enough to make it evident that if the presence of young women in college, instead of being occasional, should be constant, they would be better."

American historian David McCullough

David Gaub McCullough (; July 7, 1933 – August 7, 2022) was an American popular historian. He was a two-time winner of the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. In 2006, he was given the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the United Stat ...

mentions in his book about early 19th century Americans in Paris that in 1825 Professor Benjamin Silliman while on a tour of Europe conferring with other scientists encountered his former Yale science student Samuel F. B. Morse in the Louvre

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is the world's most-visited museum, and an historic landmark in Paris, France. It is the home of some of the best-known works of art, including the ''Mona Lisa'' and the ''Venus de Milo''. A central l ...

. McCullough also relates that Silliman would later become president of the college.

As professor emeritus, he delivered lectures at Yale on geology until 1855; Benjamin Silliman Sr had been the first person to use the process of fractional distillation

Fractional distillation is the separation of a mixture into its component parts, or fractions. Chemical compounds are separated by heating them to a temperature at which one or more fractions of the mixture will vaporize. It uses distillation to ...

, and, in 1854, Benjamin Silliman Jr became the first person to fractionate petroleum

Petroleum, also known as crude oil, or simply oil, is a naturally occurring yellowish-black liquid mixture of mainly hydrocarbons, and is found in geological formations. The name ''petroleum'' covers both naturally occurring unprocessed crude ...

by distillation.

In 1864, Silliman noted oil seeps in the Ojai, California area. In 1866, this led to the start of oil exploration and development in the Ojai Basin.

Like his son-in-law James Dana, Silliman was a Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words '' Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρ ...

. In an address delivered before the ''Association of American Geologists'' he spoke in favor of old-earth creationism, stating:

In the same line of thought, he posed arguments against atheism and materialism.

1807 meteor

At 6:30 in the morning of December 14, 1807, a blazing fireball about two-thirds the apparent size of the moon in the sky, was seen traveling southwards by early risers in Vermont and Massachusetts. Three loud explosions were heard over the town of Weston in Fairfield County, Connecticut. Stone fragments fell in at least 6 places. The largest and only unbroken stone of the Weston fall, which weighed 36.5 pounds (16.5 kilograms), was found some days after Silliman and Kingsley had spent several fruitless hours hunting for it. The owner, aTrumbull Trumbull may refer to:

Places United States

* Trumbull County, Ohio

** Trumbull Township, Ashtabula County, Ohio

* Trumbull, Connecticut

* Trumbull, Nebraska

* Fort Trumbull, Connecticut

* Mount Trumbull Wilderness in Arizona

People Surname

* ...

farmer named Elijah Seeley, was urged to present it to Yale by local people who had met the professors during their investigation, but he insisted on putting it up for sale. It was purchased by Colonel George Gibbs for his large and famous collection of minerals; when the collection became the property of Yale in 1825, Silliman finally acquired this stone; the only specimen of the Weston meteorite that remains in the Yale Peabody Museum collection today.

Personal life

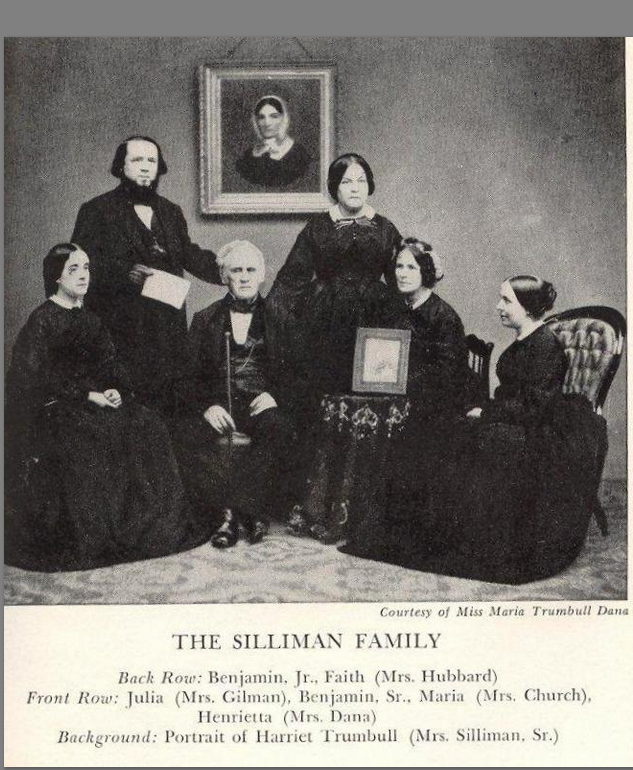

His first marriage was on September 17, 1809, to Harriet Trumbull, daughter of Connecticut governor

His first marriage was on September 17, 1809, to Harriet Trumbull, daughter of Connecticut governor Jonathan Trumbull, Jr.

Jonathan Trumbull Jr. (March 26, 1740 – August 7, 1809) was an American politician who served as the 20th governor of Connecticut, the second speaker of the United States House of Representatives, and the 24th Lieutenant Governor of Connecticu ...

, who was the son of Governor Jonathan Trumbull, Sr.

Jonathan Trumbull Sr. (October 12, 1710August 17, 1785) was an American politician and statesman who served as Governor of Connecticut during the American Revolution. Trumbull and Nicholas Cooke of Rhode Island were the only men to serve as gov ...

of Connecticut, a hero of the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolu ...

. Silliman and his wife had four children: one daughter married Professor Oliver P. Hubbard, another married Professor James Dwight Dana

James Dwight Dana FRS FRSE (February 12, 1813 – April 14, 1895) was an American geologist, mineralogist, volcanologist, and zoologist. He made pioneering studies of mountain-building, volcanic activity, and the origin and structure of contine ...

(Silliman's doctoral student until 1833 and assistant from 1836 to 1837); and youngest daughter Julia married Edward Whiting Gilman, brother of Yale graduate and educator Daniel Coit Gilman

Daniel Coit Gilman (; July 6, 1831 – October 13, 1908) was an American educator and academic. Gilman was instrumental in founding the Sheffield Scientific School at Yale College, and subsequently served as the second president of the University ...

. His son Benjamin Silliman Jr., also a professor of chemistry at Yale, wrote a report that convinced investors to back George Bissell's seminal search for oil. His second marriage was in 1851 to Mrs. Sarah Isabella (McClellan) Webb, daughter of John McClellan. Silliman died at New Haven and is buried in Grove Street Cemetery

Grove Street Cemetery or Grove Street Burial Ground is a cemetery in New Haven, Connecticut, that is surrounded by the Yale University campus. It was organized in 1796 as the New Haven Burying Ground and incorporated in October 1797 to replace the ...

.

Legacy

Silliman deemedslavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

an "enormous evil". He favored colonization

Colonization, or colonisation, constitutes large-scale population movements wherein migrants maintain strong links with their, or their ancestors', former country – by such links, gain advantage over other inhabitants of the territory. When ...

of free African Americans in Liberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to its northwest, Guinea to its north, Ivory Coast to its east, and the Atlantic Ocean to its south and southwest. It ...

, serving as a board member of the Connecticut Colonization Society

The American Colonization Society (ACS), initially the Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America until 1837, was an American organization founded in 1816 by Robert Finley to encourage and support the migration of freebor ...

between 1828 and 1835. He was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society

The American Antiquarian Society (AAS), located in Worcester, Massachusetts, is both a learned society and a national research library of pre-twentieth-century American history and culture. Founded in 1812, it is the oldest historical society in ...

in 1813,/ref> and an Associate Fellow of the

American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, ...

in 1815. Silliman founded and edited the ''American Journal of Science

The ''American Journal of Science'' (''AJS'') is the United States of America's longest-running scientific journal, having been published continuously since its conception in 1818 by Professor Benjamin Silliman, who edited and financed it himsel ...

'', and was appointed one of the corporate members of the National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nat ...

by the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washi ...

. He was also a member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science

The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) is an American international non-profit organization with the stated goals of promoting cooperation among scientists, defending scientific freedom, encouraging scientific responsi ...

.

Things named for him

Silliman College, one of Yale's residential colleges, is named for him, as is the mineralSillimanite

Sillimanite is an aluminosilicate mineral with the chemical formula Al2SiO5. Sillimanite is named after the American chemist Benjamin Silliman (1779–1864). It was first described in 1824 for an occurrence in Chester, Connecticut.

Occurrence ...

.

In Sequoia National Park

Sequoia National Park is an American national park in the southern Sierra Nevada east of Visalia, California. The park was established on September 25, 1890, and today protects of forested mountainous terrain. Encompassing a vertical relief of ...

, Mount Silliman is named for him, as is Silliman Pass, a creek

A creek in North America and elsewhere, such as Australia, is a stream that is usually smaller than a river. In the British Isles it is a small tidal inlet.

Creek may also refer to:

People

* Creek people, also known as Muscogee, Native Americans

...

and two lakes below the summit of Mount Silliman.

See also

* Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences *Petroleum

Petroleum, also known as crude oil, or simply oil, is a naturally occurring yellowish-black liquid mixture of mainly hydrocarbons, and is found in geological formations. The name ''petroleum'' covers both naturally occurring unprocessed crude ...

Notes

References

Further reading

* * * * * *External links

*Yale University on Silliman

The Yale Standard on Silliman

{{DEFAULTSORT:Silliman, Benjamin 1779 births 1864 deaths Alumni of the University of Edinburgh American chemists American mineralogists Burials at Grove Street Cemetery Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Members of the American Antiquarian Society Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences Yale University alumni Yale University faculty People from Trumbull, Connecticut Silliman family