Belemnoteuthis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Belemnotheutis'' is an extinct

The

The  The phragmocone of ''Belemnotheutis'' is short and blunt, measuring around to in length. The outer wall of the phragmocone is called the conotheca, distinct from the rostrum. It begins approximately from the tip of the phragmocone and consists of a

The phragmocone of ''Belemnotheutis'' is short and blunt, measuring around to in length. The outer wall of the phragmocone is called the conotheca, distinct from the rostrum. It begins approximately from the tip of the phragmocone and consists of a

/ref> However, it is probably a taphonomic artefact, with the protoconch being spherical like other belemnites. The long, weakly tapering structure in the dorsal (anatomy), dorsal anterior part of the internal skeleton is called the proostracum. It is striated longitudinally and often shows minute holes left by boring organisms usually less than 1 μm in diameter. The length of the proostracum is one to two times the length of the phragmocone. The proostracum was a thin, delicate structure substantially narrower than the phragmocone. Its original composition is unknown and it is always found separated from the phragmocone and the rostrum and often crushed. Whether the proostracum was connected to or derived from the phragmocone is still a subject of debate among paleontologists. Its general morphology, however, resembles that of true belemnites rather than those from other 'unusual' belemnoid coeloids with short rostra like ''

The long, weakly tapering structure in the dorsal (anatomy), dorsal anterior part of the internal skeleton is called the proostracum. It is striated longitudinally and often shows minute holes left by boring organisms usually less than 1 μm in diameter. The length of the proostracum is one to two times the length of the phragmocone. The proostracum was a thin, delicate structure substantially narrower than the phragmocone. Its original composition is unknown and it is always found separated from the phragmocone and the rostrum and often crushed. Whether the proostracum was connected to or derived from the phragmocone is still a subject of debate among paleontologists. Its general morphology, however, resembles that of true belemnites rather than those from other 'unusual' belemnoid coeloids with short rostra like ''

/ref> The head is not well preserved in known specimens. It comprised approximately 20% of the body length (excluding the arms). Brain cartilage is observed in some specimens, as well as a pair of aragonitic Statocyst, statoliths which helped the animal determine horizontal orientation when swimming. ''Belemnotheutis'', like most of the other belemnoids, had ten arms of equal length lined with two rows of inward-pointing hooks each. Each of the hooks were composed of several sections. The curved pointed tip is called the uncinus and was probably the only part of the hooks exposed. The rest of the hook (the shaft and the base) were embedded in a sheath of soft tissue below the orbicular scar, a small groove where the tissue attachment terminated. They are also believed to have been stalked and mobile, helping the animal manipulate its prey. Traces of functional suckers have been found and these constitute a single row on each arm, alternating in between the pairs of hooks. The size of the suckers decreases

/ref> The animal reached in length, including its arms. The body diameter was around 12 to 14% of the mantle length. At the center of the dorsal surface of the rostrum is a narrow V-shaped groove running about 3/5ths the length of the phragmocone from the apex, with two rounded ridges at its left and right sides. These grooves are one of the most distinctive features of the Belemnotheutidae and are theorized to have served as attachments to terminal oval or oar-shaped fins like in some modern squids. The

The ink recovered from such fossils were also used to draw fossil ichthyosaurs by

"After 150m years as a fossil, Belemnotheutis antiquus takes up its pen."

''The Sunday Times''. By mixing it with

"Scientists draw squid using its 150 million-year-old fossilised ink"

''The Telegraph''.

''Belemnotheutis'' was first described by the amateur

''Belemnotheutis'' was first described by the amateur

The Royal Societ

/ref> further inducing Pearce to protest what he viewed as erroneous descriptions of the specimens. In 1847, the ''London Geological Journal'' published a paper by Pearce of his objections to Owen's paper. At the same time the editor of the paper and another paleontologist,

A drawing of ''Belemnotheutis'' drawn in fossil ink

British Geological Survey. {{Taxonbar, from=Q147629 Jurassic cephalopods Prehistoric life of Europe Middle Jurassic genus first appearances Late Jurassic genus extinctions

coleoid

Subclass (biology), Subclass Coleoidea,

or Dibranchiata, is the grouping of cephalopods containing all the various taxa popularly thought of as "soft-bodied" or "shell-less" (i.e., octopuses, squid and cuttlefish). Unlike its extant sister group, ...

cephalopod

A cephalopod is any member of the molluscan class Cephalopoda (Greek plural , ; "head-feet") such as a squid, octopus, cuttlefish, or nautilus. These exclusively marine animals are characterized by bilateral body symmetry, a prominent head ...

genus from the middle and upper Jurassic, related to but morphologically distinct from belemnites Belemnites may refer to:

*Belemnitida

Belemnitida (or the belemnite) is an extinct order of squid-like cephalopods that existed from the Late Triassic to Late Cretaceous. Unlike squid, belemnites had an internal skeleton that made up the cone. ...

.

''Belemnotheutis'' fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

s are some of the best preserved among coleoid

Subclass (biology), Subclass Coleoidea,

or Dibranchiata, is the grouping of cephalopods containing all the various taxa popularly thought of as "soft-bodied" or "shell-less" (i.e., octopuses, squid and cuttlefish). Unlike its extant sister group, ...

s. Remains of soft tissue are well-documented in some specimens, even down to microscopic muscle tissue

Muscle tissue (or muscular tissue) is soft tissue that makes up the different types of muscles in most animals, and give the ability of muscles to contract. Muscle tissue is formed during embryonic development, in a process known as myogenesis. Mu ...

. In 2008, a group of paleontologist

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

s even recovered viable ink

Ink is a gel, sol, or solution that contains at least one colorant, such as a dye or pigment, and is used to color a surface to produce an image, text, or design. Ink is used for drawing or writing with a pen, brush, reed pen, or quill. Thi ...

from ink sac

An ink sac is an anatomical feature that is found in many cephalopod mollusks used to produce the defensive cephalopod ink. With the exception of nocturnal and very deep water cephalopods, all Coleoidea (squid, octopus and cuttlefish) which dwell ...

s found in several specimens.

This genus was the subject of a dispute between several eminent 19th century British paleontologist

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

s, notably between Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and paleontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils.

Owe ...

and Gideon Mantell

Gideon Algernon Mantell MRCS FRS (3 February 1790 – 10 November 1852) was a British obstetrician, geologist and palaeontologist. His attempts to reconstruct the structure and life of ''Iguanodon'' began the scientific study of dinosaurs: in ...

. Some authors incorrectly spell the genus ''Belemnoteuthis'' following the usual spelling ''teuthis'' (τευθίς) for 'squid'.

Description

The genus ''Belemnotheutis'' is characterized by an internal shell consisting of a conicalphragmocone

The phragmocone is the chambered portion of the shell of a cephalopod. It is divided by septa into camerae.

In most nautiloids and ammonoids, the phragmocone is a long, straight, curved, or coiled structure, in which the camarae are linked by a ...

covered apically by a thin rostrum, or guard, homologous to the bullet-shaped rostrum of true belemnites, a short forward projecting proostracum, and ten hook bearing arms of equal length.

''Belemnotheutis'' fossils are sometimes found in remarkable states of preservation, some specimens retaining permineralized

Permineralization is a process of fossilization of bones and tissues in which mineral deposits form internal casts of organisms. Carried by water, these minerals fill the spaces within organic tissue. Because of the nature of the casts, perminera ...

soft tissue. The mantle

A mantle is a piece of clothing, a type of cloak. Several other meanings are derived from that.

Mantle may refer to:

*Mantle (clothing), a cloak-like garment worn mainly by women as fashionable outerwear

**Mantle (vesture), an Eastern Orthodox ve ...

, fins, head, arms

Arms or ARMS may refer to:

*Arm or arms, the upper limbs of the body

Arm, Arms, or ARMS may also refer to:

People

* Ida A. T. Arms (1856–1931), American missionary-educator, temperance leader

Coat of arms or weapons

*Armaments or weapons

**Fi ...

, and hooks are well-documented from remains preserved in ''Lagerstätte

A Lagerstätte (, from ''Lager'' 'storage, lair' '' Stätte'' 'place'; plural ''Lagerstätten'') is a sedimentary deposit that exhibits extraordinary fossils with exceptional preservation—sometimes including preserved soft tissues. These for ...

n''. One specimen recovered from Christian Malford

Christian Malford is a village and civil parish in the county of Wiltshire, England. The village lies about northeast of the town of Chippenham. The Bristol Avon forms most of the northern and eastern boundaries of the parish. The hamlets of Tho ...

, Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

and currently displayed in the Paleontology Department of the Natural History Museum

A natural history museum or museum of natural history is a scientific institution with natural history collections that include current and historical records of animals, plants, fungi, ecosystems, geology, paleontology, climatology, and more. ...

in London is fossilized clasping a fish.

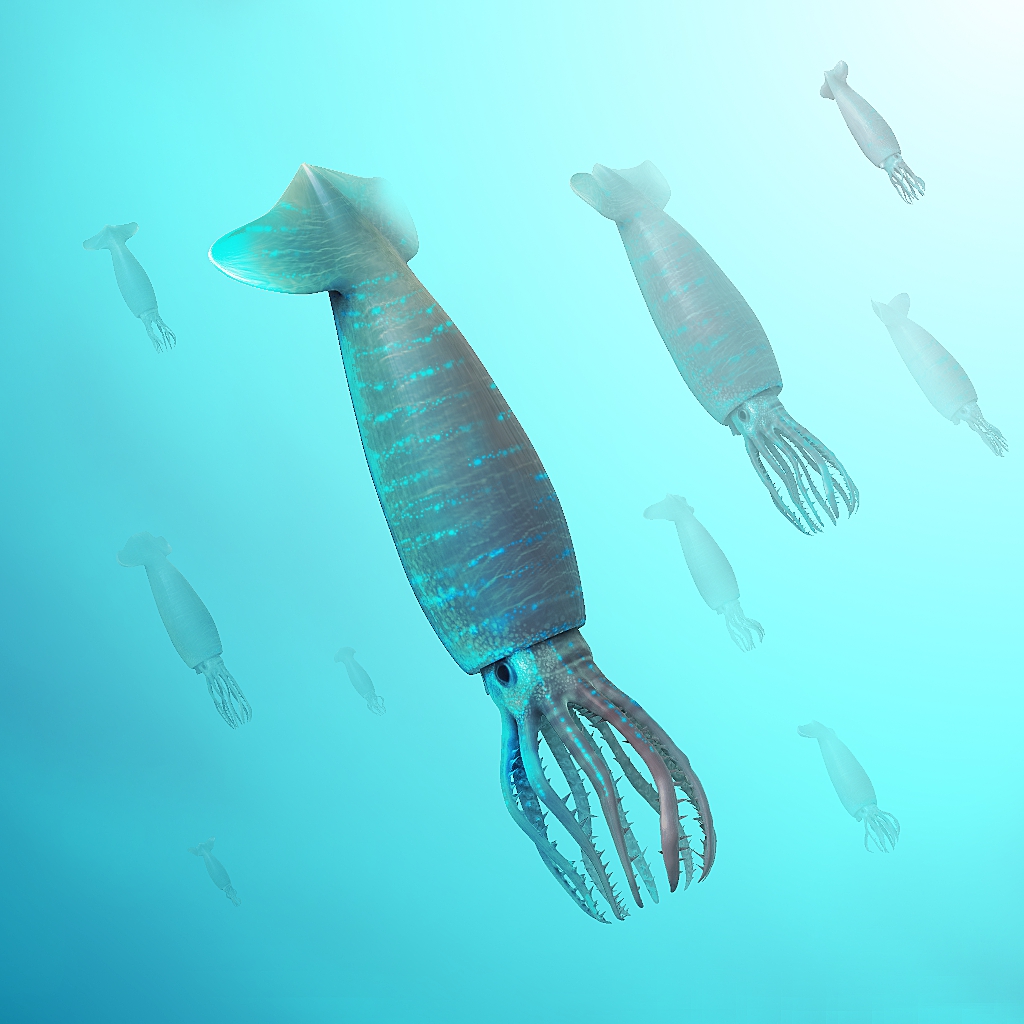

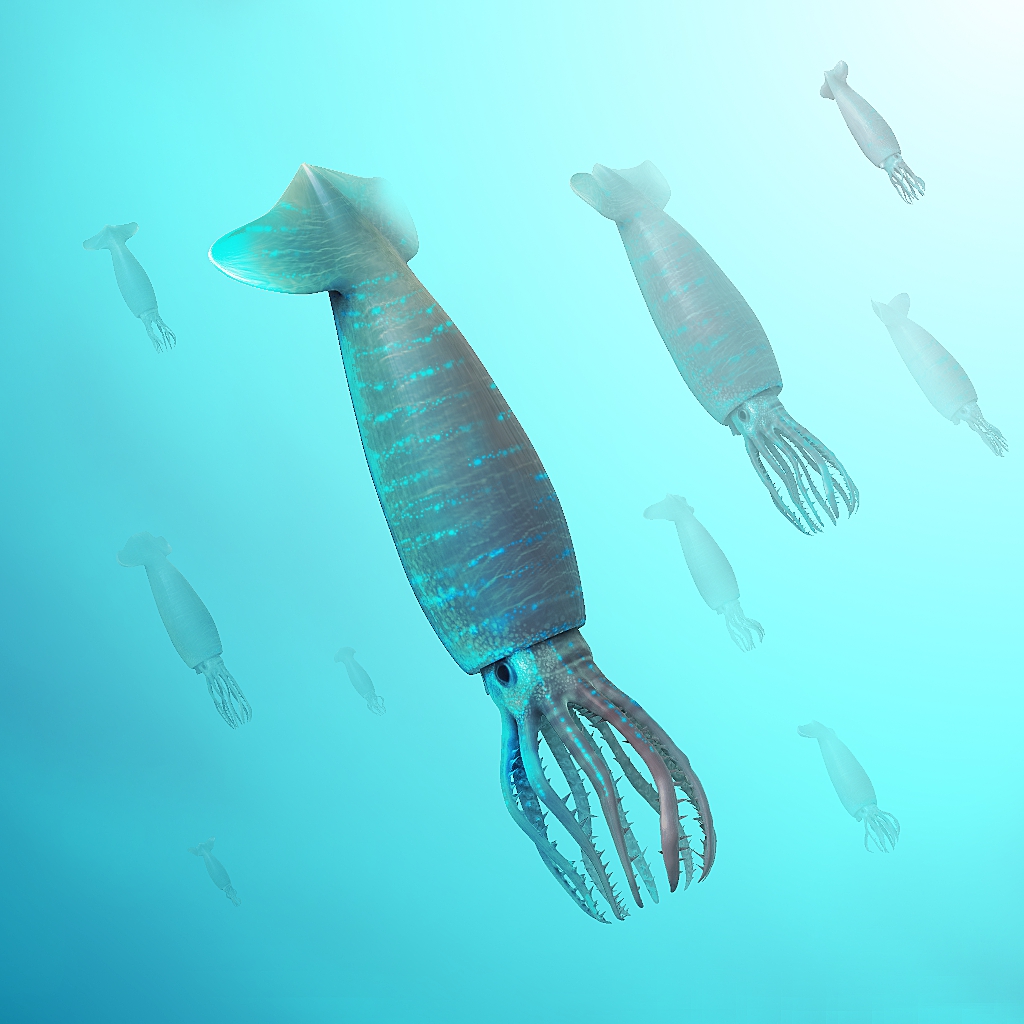

''Belemnotheutis'' is not a 'true' belemnite

Belemnitida (or the belemnite) is an extinct order of squid-like cephalopods that existed from the Late Triassic to Late Cretaceous. Unlike squid, belemnites had an internal skeleton that made up the cone. The parts are, from the arms-most to ...

(suborder

Order ( la, ordo) is one of the eight major hierarchical taxonomic ranks in Linnaean taxonomy. It is classified between family and class. In biological classification, the order is a taxonomic rank used in the classification of organisms and ...

Belemnitina

Belemnitina is a suborder of belemnites, an extinct group of cephalopods. They have been identified as the oldest of all the belemnites and are likely the stockgroup for them. They were extant from the early Jurassic to the early Cretaceous. The ...

) but a closely related coleoid. Both belemnotheutids and belemnites resembled modern squid

True squid are molluscs with an elongated soft body, large eyes, eight arms, and two tentacles in the superorder Decapodiformes, though many other molluscs within the broader Neocoleoidea are also called squid despite not strictly fitting t ...

s except that they had chambered internal skeletons called phragmocone

The phragmocone is the chambered portion of the shell of a cephalopod. It is divided by septa into camerae.

In most nautiloids and ammonoids, the phragmocone is a long, straight, curved, or coiled structure, in which the camarae are linked by a ...

s.

The

The apical

Apical means "pertaining to an apex". It may refer to:

*Apical ancestor, refers to the last common ancestor of an entire group, such as a species (biology) or a clan (anthropology)

*Apical (anatomy), an anatomical term of location for features loc ...

portion of the ''Belemnotheutis'' internal skeleton is called the rostrum (plural: rostra) or the guard. The rostrum of ''Belemnotheutis'' differs significantly from that of true belemnite

Belemnitida (or the belemnite) is an extinct order of squid-like cephalopods that existed from the Late Triassic to Late Cretaceous. Unlike squid, belemnites had an internal skeleton that made up the cone. The parts are, from the arms-most to ...

s. Unlike the bullet-shaped dense guards of belemnite

Belemnitida (or the belemnite) is an extinct order of squid-like cephalopods that existed from the Late Triassic to Late Cretaceous. Unlike squid, belemnites had an internal skeleton that made up the cone. The parts are, from the arms-most to ...

s, the rostrum of ''Belemnotheutis'' is only present as a very thin sheath. It was also composed of aragonite

Aragonite is a carbonate mineral, one of the three most common naturally occurring crystal forms of calcium carbonate, (the other forms being the minerals calcite and vaterite). It is formed by biological and physical processes, including prec ...

rather than the heavy calcite

Calcite is a Carbonate minerals, carbonate mineral and the most stable Polymorphism (materials science), polymorph of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). It is a very common mineral, particularly as a component of limestone. Calcite defines hardness 3 on ...

of belemnites. In large specimens the rostrum can reach a maximum of only in thickness near the tip. The outer surface was covered by a thin organic layer in the live animal. In true belemnites, the large dense rostra acted as a counterbalance, keeping the animal horizontally oriented when swimming. It was long assumed that ''Belemnotheutis'' were confined to shallow waters, unable to venture into deeper waters due to the absence of the heavy rostra. The discovery of cameral deposits in the phragmocones of ''Belemnotheutis'' in 1952 made it clear that they were capable of controlling buoyancy.

The phragmocone of ''Belemnotheutis'' is short and blunt, measuring around to in length. The outer wall of the phragmocone is called the conotheca, distinct from the rostrum. It begins approximately from the tip of the phragmocone and consists of a

The phragmocone of ''Belemnotheutis'' is short and blunt, measuring around to in length. The outer wall of the phragmocone is called the conotheca, distinct from the rostrum. It begins approximately from the tip of the phragmocone and consists of a nacre

Nacre ( , ), also known as mother of pearl, is an organicinorganic composite material produced by some molluscs as an inner shell layer; it is also the material of which pearls are composed. It is strong, resilient, and iridescent.

Nacre is f ...

ous outer layer and an inner lamellar layer. The outer layer gradually thins from in thickness to only about thick at about further down the shell until it eventually disappears around the opening of the phragmocone (the peristome Peristome (from the Greek ''peri'', meaning 'around' or 'about', and ''stoma'', 'mouth') is an anatomical feature that surrounds an opening to an organ or structure. Some plants, fungi, and shelled gastropods have peristomes.

In mosses

In mosses, ...

). Sometimes there is a hollow gap between the rostrum and the lamellar layer of the conotheca, indicating either organic content that have since disappeared or disintegration of the lamellar layer itself. The phragmocone

The phragmocone is the chambered portion of the shell of a cephalopod. It is divided by septa into camerae.

In most nautiloids and ammonoids, the phragmocone is a long, straight, curved, or coiled structure, in which the camarae are linked by a ...

of ''Belemnotheutis'' had about 50 chambers that were originally aragonitic

Aragonite is a carbonate mineral, one of the three most common naturally occurring crystal forms of calcium carbonate, (the other forms being the minerals calcite and vaterite). It is formed by biological and physical processes, including pre ...

, though they are usually replaced by calcium phosphate

The term calcium phosphate refers to a family of materials and minerals containing calcium ions (Ca2+) together with inorganic phosphate anions. Some so-called calcium phosphates contain oxide and hydroxide as well. Calcium phosphates are white ...

during the process of fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

ization.Donovan D.T & Crane M.D. 1992. The type material of the Jurassic cephalopod ''Belemnotheutis'', Palaeontology vol35, issue 2, pp273–296

At the very tip of the phragmocone beneath the rostrum is an embryonic shell known as the protoconch

A protoconch (meaning first or earliest or original shell) is an embryonic or larval shell which occurs in some classes of molluscs, e.g., the initial chamber of an ammonite or the larval shell of a gastropod. In older texts it is also called ...

. In ''Belemnotheutis'', like in other belemnotheutids, the protoconch is roughly cup-shaped and sealed. This was thought to be another method of distinguishing it from other belemnites which usually have ball-shaped protoconchs.Reitner, J. & Engeser,T., 1982. Phylogenetic trends in phragmocone-bearing coleoids (Belemnomorpha); Konstruktions-Morphologie, pp157–158, E. Schweizerbart'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Stuttgart/ref> However, it is probably a taphonomic artefact, with the protoconch being spherical like other belemnites.

The long, weakly tapering structure in the dorsal (anatomy), dorsal anterior part of the internal skeleton is called the proostracum. It is striated longitudinally and often shows minute holes left by boring organisms usually less than 1 μm in diameter. The length of the proostracum is one to two times the length of the phragmocone. The proostracum was a thin, delicate structure substantially narrower than the phragmocone. Its original composition is unknown and it is always found separated from the phragmocone and the rostrum and often crushed. Whether the proostracum was connected to or derived from the phragmocone is still a subject of debate among paleontologists. Its general morphology, however, resembles that of true belemnites rather than those from other 'unusual' belemnoid coeloids with short rostra like ''

The long, weakly tapering structure in the dorsal (anatomy), dorsal anterior part of the internal skeleton is called the proostracum. It is striated longitudinally and often shows minute holes left by boring organisms usually less than 1 μm in diameter. The length of the proostracum is one to two times the length of the phragmocone. The proostracum was a thin, delicate structure substantially narrower than the phragmocone. Its original composition is unknown and it is always found separated from the phragmocone and the rostrum and often crushed. Whether the proostracum was connected to or derived from the phragmocone is still a subject of debate among paleontologists. Its general morphology, however, resembles that of true belemnites rather than those from other 'unusual' belemnoid coeloids with short rostra like ''Permoteuthis

''Permoteuthis'' is a genus of belemnite, an extinct group of cephalopods.

See also

* Belemnite

* List of belemnites

This list of belemnite genera is an attempt to create a comprehensive listing of all genera that have ever been included in ...

'' and ''Phragmoteuthis

''Phragmoteuthis'' is a genus of extinct coleoid cephalopod known from the late Triassic to the lower Jurassic. Its soft tissue has been preserved; some specimens contain intact ink sacs, and others, gills. It had an internal phragmocone and unk ...

''.Jeletzky, J.A. 1966. Comparative Morphology, Phylogeny, and Classification of Fossil Coleoidea; Mollusca pp 1–162; The University of Kansas, Paleontological Contribution/ref> The head is not well preserved in known specimens. It comprised approximately 20% of the body length (excluding the arms). Brain cartilage is observed in some specimens, as well as a pair of aragonitic Statocyst, statoliths which helped the animal determine horizontal orientation when swimming. ''Belemnotheutis'', like most of the other belemnoids, had ten arms of equal length lined with two rows of inward-pointing hooks each. Each of the hooks were composed of several sections. The curved pointed tip is called the uncinus and was probably the only part of the hooks exposed. The rest of the hook (the shaft and the base) were embedded in a sheath of soft tissue below the orbicular scar, a small groove where the tissue attachment terminated. They are also believed to have been stalked and mobile, helping the animal manipulate its prey. Traces of functional suckers have been found and these constitute a single row on each arm, alternating in between the pairs of hooks. The size of the suckers decreases

distal

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously describe the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position pro ...

ly along the arms, with the largest (around in diameter) being closest to the head. The length of the arms varies with the size of the individual but may have reached in larger specimens.

''Belemnotheutis'' had a cylindriconical muscular

Skeletal muscles (commonly referred to as muscles) are organs of the vertebrate muscular system and typically are attached by tendons to bones of a skeleton. The muscle cells of skeletal muscles are much longer than in the other types of muscle ...

mantle

A mantle is a piece of clothing, a type of cloak. Several other meanings are derived from that.

Mantle may refer to:

*Mantle (clothing), a cloak-like garment worn mainly by women as fashionable outerwear

**Mantle (vesture), an Eastern Orthodox ve ...

covered by an outer and inner skin (tunic). Traces of a criss-cross pattern composed of collagen

Collagen () is the main structural protein in the extracellular matrix found in the body's various connective tissues. As the main component of connective tissue, it is the most abundant protein in mammals, making up from 25% to 35% of the whole ...

fibers have been observed in the surface of some well-preserved fossils. The cross section of the exceptionally preserved body wall of a specimen from the Oxford Clay

The Oxford Clay (or Oxford Clay Formation) is a Jurassic marine sedimentary rock formation underlying much of southeast England, from as far west as Dorset and as far north as Yorkshire. The Oxford Clay Formation dates to the Jurassic, specifical ...

formations also reveals alternating bands of concentrically and radially oriented body fibers. They imply that ''Belemnotheutis'' were powerful swimmers and agile predators, similar to modern shallow-water squid species.

Philip R. Wilby et al 2008. Preserving the unpreservable: a lost world rediscovered at Christian Malford, UK. Geology Today Vol 24(3). Blackwell Publishing Ltd/ref> The animal reached in length, including its arms. The body diameter was around 12 to 14% of the mantle length. At the center of the dorsal surface of the rostrum is a narrow V-shaped groove running about 3/5ths the length of the phragmocone from the apex, with two rounded ridges at its left and right sides. These grooves are one of the most distinctive features of the Belemnotheutidae and are theorized to have served as attachments to terminal oval or oar-shaped fins like in some modern squids. The

siphuncle

The siphuncle is a strand of tissue passing longitudinally through the shell of a cephalopod mollusk. Only cephalopods with chambered shells have siphuncles, such as the extinct ammonites and belemnites, and the living nautiluses, cuttlefish, and ...

is marginal and located ventral

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously describe the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek language, Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. Th ...

ly. Directly in front of the phragmocone was an ink sac

An ink sac is an anatomical feature that is found in many cephalopod mollusks used to produce the defensive cephalopod ink. With the exception of nocturnal and very deep water cephalopods, all Coleoidea (squid, octopus and cuttlefish) which dwell ...

that could reach long in large specimens. Intestinal casts (cololites) as well as the orientations and positions of fossilized remains reveal that the animal preyed on fish and other coleoids in life. Their great abundance in certain formations indicate that ''Belemnotheutis'' were highly gregarious animals, congregating in large monospecific or polyspecific shoals.

Distribution and geological time range

''Belemnotheutis'' existed during the lateMiddle Jurassic

The Middle Jurassic is the second epoch of the Jurassic Period. It lasted from about 174.1 to 163.5 million years ago. Fossils of land-dwelling animals, such as dinosaurs, from the Middle Jurassic are relatively rare, but geological formations co ...

to the Upper Jurassic

The Late Jurassic is the third epoch of the Jurassic Period, and it spans the geologic time from 163.5 ± 1.0 to 145.0 ± 0.8 million years ago (Ma), which is preserved in Upper Jurassic strata.Owen 1987.

In European lithostratigraphy, the name ...

epoch

In chronology and periodization, an epoch or reference epoch is an instant in time chosen as the origin of a particular calendar era. The "epoch" serves as a reference point from which time is measured.

The moment of epoch is usually decided by ...

, from the Callovian

In the geologic timescale, the Callovian is an age and stage in the Middle Jurassic, lasting between 166.1 ± 4.0 Ma (million years ago) and 163.5 ± 4.0 Ma. It is the last stage of the Middle Jurassic, following the Bathonian and preceding the ...

age

Age or AGE may refer to:

Time and its effects

* Age, the amount of time someone or something has been alive or has existed

** East Asian age reckoning, an Asian system of marking age starting at 1

* Ageing or aging, the process of becoming older ...

(166.1 to 163.5 mya) to the Kimmeridgian

In the geologic timescale, the Kimmeridgian is an age in the Late Jurassic Epoch and a stage in the Upper Jurassic Series. It spans the time between 157.3 ± 1.0 Ma and 152.1 ± 0.9 Ma (million years ago). The Kimmeridgian follows the Oxfordian ...

age (157.3 to 152.1 mya). The belemnotheutid '' Acanthoteuthis'', a close relative which is treated by some paleontologists as synonymous

A synonym is a word, morpheme, or phrase that means exactly or nearly the same as another word, morpheme, or phrase in a given language. For example, in the English language, the words ''begin'', ''start'', ''commence'', and ''initiate'' are all ...

with ''Belemnotheutis'', is known to have existed from as early as the Callovian

In the geologic timescale, the Callovian is an age and stage in the Middle Jurassic, lasting between 166.1 ± 4.0 Ma (million years ago) and 163.5 ± 4.0 Ma. It is the last stage of the Middle Jurassic, following the Bathonian and preceding the ...

age (166.1 to 163.5 mya) of the Middle Jurassic

The Middle Jurassic is the second epoch of the Jurassic Period. It lasted from about 174.1 to 163.5 million years ago. Fossils of land-dwelling animals, such as dinosaurs, from the Middle Jurassic are relatively rare, but geological formations co ...

epoch to as late as the Aptian

The Aptian is an age in the geologic timescale or a stage in the stratigraphic column. It is a subdivision of the Early or Lower Cretaceous Epoch or Series and encompasses the time from 121.4 ± 1.0 Ma to 113.0 ± 1.0 Ma (million years ago), a ...

age (125 to 112 mya) of the Lower Cretaceous

Lower may refer to:

*Lower (surname)

*Lower Township, New Jersey

*Lower Receiver (firearms)

*Lower Wick

Lower Wick is a small hamlet located in the county of Gloucestershire, England. It is situated about five miles south west of Dursley, eight ...

epoch. The earliest known possible remains of belemnotheutids (genera '' Chitinobelus'' and '' Chondroteuthis'') come from the Lower Jurassic

The Early Jurassic Epoch (in chronostratigraphy corresponding to the Lower Jurassic Series) is the earliest of three epochs of the Jurassic Period. The Early Jurassic starts immediately after the Triassic-Jurassic extinction event, 201.3 Ma ...

, from phragmocones and rostra recovered from Toarcian

The Toarcian is, in the ICS' geologic timescale, an age and stage in the Early or Lower Jurassic. It spans the time between 182.7 Ma (million years ago) and 174.1 Ma. It follows the Pliensbachian and is followed by the Aalenian.

The Toarcian ...

formations in Dumbleton

Dumbleton is a village and civil parish in the English county of Gloucestershire. The village is roughly 20 miles from the city of Gloucester. The village is known to have existed in the time of Æthelred I who granted land to Abingdon Abbey, a ...

, Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire ( abbreviated Glos) is a county in South West England. The county comprises part of the Cotswold Hills, part of the flat fertile valley of the River Severn and the entire Forest of Dean.

The county town is the city of Gl ...

, and Ilminster

Ilminster is a minster town and civil parish in the South Somerset district of Somerset, England, with a population of 5,808. Bypassed in 1988, the town now lies just east of the junction of the A303 (London to Exeter) and the A358 (Taunton to ...

, Somerset

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lord_ ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

. However, these remains seem to have possessed the typical calcitic rostra of true belemnites rather than the characteristic aragonitic rostra of belemnotheutids.

''Belemnotheutis'' serve as index fossil

Biostratigraphy is the branch of stratigraphy which focuses on correlating and assigning relative ages of rock Stratum, strata by using the fossil assemblages contained within them.Hine, Robert. “Biostratigraphy.” ''Oxford Reference: Dictiona ...

s. They are mostly found in Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The J ...

formations like the Kimmeridge Clay

The Kimmeridge Clay is a sedimentary deposit of fossiliferous marine clay which is of Late Jurassic to lowermost Cretaceous age and occurs in southern and eastern England and in the North Sea. This rock formation is the major source rock for North ...

formation, the Oxford Clay

The Oxford Clay (or Oxford Clay Formation) is a Jurassic marine sedimentary rock formation underlying much of southeast England, from as far west as Dorset and as far north as Yorkshire. The Oxford Clay Formation dates to the Jurassic, specifical ...

formation, and the Solnhofen Limestone formation. Their geographic range, thus far, is confined to Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

.

Taxonomy and nomenclature

''Belemnotheutis'' arecoleoid

Subclass (biology), Subclass Coleoidea,

or Dibranchiata, is the grouping of cephalopods containing all the various taxa popularly thought of as "soft-bodied" or "shell-less" (i.e., octopuses, squid and cuttlefish). Unlike its extant sister group, ...

s belonging to the family

Family (from la, familia) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its ...

Belemnotheutidae. ''Belemnotheutis'' and other belemnotheutids are considered by some paleontologists to be distinct from true belemnites (suborder

Order ( la, ordo) is one of the eight major hierarchical taxonomic ranks in Linnaean taxonomy. It is classified between family and class. In biological classification, the order is a taxonomic rank used in the classification of organisms and ...

Belemnitina

Belemnitina is a suborder of belemnites, an extinct group of cephalopods. They have been identified as the oldest of all the belemnites and are likely the stockgroup for them. They were extant from the early Jurassic to the early Cretaceous. The ...

). Most authorities like Jeletzky (1966), Bandel and Kulicki (1988), and Peter Doyle (1990) classify it under Belemnitida in the suborder Belemnotheutina (the classification used by this article). Others like Donovan (1977) and Engeser and Reitner (1981) classify it as a distinct order, Belemnotheutida, based on the aragonitic constitution of the rostra, the shape of the proostraca, protoconchs, and the arm crowns, among other morphological factors.

''Belemnotheutis'' has been continually spelled as ''Belemnoteuthis'' by authors who believed that Pearce had made an honest mistake in naming the specimens. In 1999, D.T. Donovan and M.D. Crane succeeded in convincing the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature

The International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) is an organization dedicated to "achieving stability and sense in the scientific naming of animals". Founded in 1895, it currently comprises 26 commissioners from 20 countries.

Orga ...

that the spelling was intentional, citing historical usage of the spelling Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

θευτίς (''theutis'') as a valid variant of the usual τευθίς (''teuthis'', 'squid'). Subsequently, the accepted spelling is now formally ''Belemnotheutis''.

Species

The following is a list of species described under the genus ''Belemnotheutis''.Engeser, T.S. and J. Reitner. 1992. Ein neues Exemplar von ''Belemnoteuthis mayri'' Engeser & Reitner, 1981 (Coleoidea, Cephalopoda) aus dem Solnhofener Plattenkalk (Untertithonium) von Wintershof, Bayern. Archaeopteryx 10:13-17. *''Belemnotheutis antiquus'' Pearce, 1842 *''Belemnotheutis polonica'' Makowski, 1952 *''Belemnotheutis mayri'' Engeser & Reitner, 1981 ''Belemnotheutis montefiorei'' has been transferred to the genus ''Phragmoteuthis

''Phragmoteuthis'' is a genus of extinct coleoid cephalopod known from the late Triassic to the lower Jurassic. Its soft tissue has been preserved; some specimens contain intact ink sacs, and others, gills. It had an internal phragmocone and unk ...

'' and ''B. rosenkrantzi'' to the genus ''Groenlandibelus

Groenlandibelidae is a family of coleoid cephalopods believed to belong to the spirulids.

Morphologically, its taxa seem to have some belemnoid characteristics, suggesting a possible intermediate relationship.

Genera

''Groenlandibelus '' Je ...

''.

Fossil ink

Fossilizedink sac

An ink sac is an anatomical feature that is found in many cephalopod mollusks used to produce the defensive cephalopod ink. With the exception of nocturnal and very deep water cephalopods, all Coleoidea (squid, octopus and cuttlefish) which dwell ...

s were first discovered in belemnites in 1826 by Mary Anning

Mary Anning (21 May 1799 – 9 March 1847) was an English fossil collector, dealer, and palaeontologist who became known around the world for the discoveries she made in Jurassic marine fossil beds in the cliffs along the English Channel ...

a famous British fossil collector and paleontologist, who along with her brother Joseph and a friend and fellow fossil collector Elizabeth Philpot

Elizabeth Philpot (1780–1857) was an early 19th-century British fossil collector, amateur palaeontologist and artist who collected fossils from the cliffs around Lyme Regis in Dorset on the southern coast of England. She is best known today fo ...

succeeded in recovering the ink

Ink is a gel, sol, or solution that contains at least one colorant, such as a dye or pigment, and is used to color a surface to produce an image, text, or design. Ink is used for drawing or writing with a pen, brush, reed pen, or quill. Thi ...

, used to illustrate ichthyosaur

Ichthyosaurs (Ancient Greek for "fish lizard" – and ) are large extinct marine reptiles. Ichthyosaurs belong to the order known as Ichthyosauria or Ichthyopterygia ('fish flippers' – a designation introduced by Sir Richard Owen in 1842, altho ...

and pterosaur

Pterosaurs (; from Greek ''pteron'' and ''sauros'', meaning "wing lizard") is an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order, Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 to ...

fossils.Woodward, Horace Bolingbroke. ''The history of the Geological Society of London'' Geological Society, London 1978, page 115Pharaoh, J.B.1837. Fossil Remains of naked Mollusks, Pens, and Ink-Bags of ''Loligo''. Madras Journal of Literature and Science vol5, issue 14. pp 403–406. Madras Literary Society, Auxiliary Royal Asiatic SocietThe ink recovered from such fossils were also used to draw fossil ichthyosaurs by

Henry De la Beche

Sir Henry Thomas De la Beche KCB, FRS (10 February 179613 April 1855) was an English geologist and palaeontologist, the first director of the Geological Survey of Great Britain, who helped pioneer early geological survey methods. He was the f ...

, a friend and supporter of Mary Anning.

In 2008, an excavation team led by the British Geological Survey

The British Geological Survey (BGS) is a partly publicly funded body which aims to advance geoscientific knowledge of the United Kingdom landmass and its continental shelf by means of systematic surveying, monitoring and research.

The BGS h ...

in Christian Malford

Christian Malford is a village and civil parish in the county of Wiltshire, England. The village lies about northeast of the town of Chippenham. The Bristol Avon forms most of the northern and eastern boundaries of the parish. The hamlets of Tho ...

recovered fossilized ink sacs from several remarkably preserved remains of ''Belemnotheutis antiquus'' in the Oxford Clay. The specimens were fossilized rapidly in apatite

Apatite is a group of phosphate minerals, usually hydroxyapatite, fluorapatite and chlorapatite, with high concentrations of OH−, F− and Cl− ions, respectively, in the crystal. The formula of the admixture of the three most common e ...

(calcium phosphate) through a process paleontologist Phil Wilby called "The Medusa Effect".De Bruxelles, Simon (August 19, 2009)"After 150m years as a fossil, Belemnotheutis antiquus takes up its pen."

''The Sunday Times''. By mixing it with

ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . A stable binary hydride, and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinct pungent smell. Biologically, it is a common nitrogenous was ...

solution, the team was able to return the ink to its liquid form. Bringing to mind the 19th century practices of the aforementioned early paleontologists, they used the ~150 million year old ink to draw a replica of the original illustration of ''Belemnotheutis'' as drawn by Joseph Pearce. Dr. Wilby called the drawing "the ultimate self-portrait".Wardrop, Murray (August 19, 2009)"Scientists draw squid using its 150 million-year-old fossilised ink"

''The Telegraph''.

History and controversy

''Belemnotheutis'' was first described by the amateur

''Belemnotheutis'' was first described by the amateur paleontologist

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

Joseph Pearce

Joseph Pearce (born February 12, 1961), is an English-born American writer, and Director of the Center for Faith and Culture at Aquinas College in Nashville, Tennessee, before which he held positions at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts in ...

in 1842 in Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

, South West England

South West England, or the South West of England, is one of nine official regions of England. It consists of the counties of Bristol, Cornwall (including the Isles of Scilly), Dorset, Devon, Gloucestershire, Somerset and Wiltshire. Cities and ...

, two years after excavations from the construction of the Great Western Railway

The Great Western Railway (GWR) was a British railway company that linked London with the southwest, west and West Midlands of England and most of Wales. It was founded in 1833, received its enabling Act of Parliament on 31 August 1835 and ran ...

uncovered parts of the Oxford Clay. It is unknown why he chose the spelling ''Belemnotheutis'' rather than ''Belemnoteuthis'' as convention would have dictated. He described his discovery to the Geological Society of London

The Geological Society of London, known commonly as the Geological Society, is a learned society based in the United Kingdom. It is the oldest national geological society in the world and the largest in Europe with more than 12,000 Fellows.

Fe ...

in the same year.

In 1843, Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and paleontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils.

Owe ...

acquired specimens of ''Belemnotheutis'' from the same locality from another paleontologist, Samuel Pratt. He formally published a paper in 1844 (''On the Belemnites'', ''Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society

''Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society'' is a scientific journal published by the Royal Society. In its earliest days, it was a private venture of the Royal Society's secretary. It was established in 1665, making it the first journa ...

''), naming the specimens ''Belemnites owenii'' Pratt, after himself and crediting Pratt with the discovery while failing to mention Pearce. He believed that the specimens were of the genus ''Belemnites Belemnites may refer to:

*Belemnitida

Belemnitida (or the belemnite) is an extinct order of squid-like cephalopods that existed from the Late Triassic to Late Cretaceous. Unlike squid, belemnites had an internal skeleton that made up the cone. ...

'' whose typically lengthy rostra simply got separated. He sent a copy of the paper to Pearce in the same year, proving that he was actually aware of Pearce's earlier description but had deliberately omitted any mention of him. Pearce responded by stating that examination by another paleontologist James Bowerbank, supported his belief that fossils did not possess the bullet-shaped guards typical of ''Belemnites'' but instead had rostra in the form of very thin sheaths. Bowerbanks confirmed this assertion but supported Owen's assignment of ''Belemnites'', saying that the presence of very short rostra did not justify the classification of ''Belemnotheutis'' as a separate genus from ''Belemnites''.

Owen received a Royal Medal

The Royal Medal, also known as The Queen's Medal and The King's Medal (depending on the gender of the monarch at the time of the award), is a silver-gilt medal, of which three are awarded each year by the Royal Society, two for "the most important ...

from the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

in 1846 for the 1844 paper,Royal archive winners Prior to 190The Royal Societ

/ref> further inducing Pearce to protest what he viewed as erroneous descriptions of the specimens. In 1847, the ''London Geological Journal'' published a paper by Pearce of his objections to Owen's paper. At the same time the editor of the paper and another paleontologist,

Edward Charlesworth

Edward Charlesworth (5 September 1813 – 28 July 1893) was an English geologist and palaeontologist.

Edward Charlesworth was the eldest son of the Rev John Charlesworth. He studied medicine but abandoned a career in this discipline in 1836 to wo ...

, published an editorial criticizing Owen for deliberately failing to credit Pearce with the discovery of ''Belemnotheutis'', as well as his apparent disregard to the opinions of less well-known paleontologists like Pearce. This was also the first time that Pearce described the specific epithet

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called nomenclature ("two-name naming system") or binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, bot ...

''antiquus'' to the fossils. Pearce died later in the same year in May 1847 taking no further part in what was to become a controversy. Shortly after his death, the same paper published the support of William Cunnington

William Cunnington FSA (1754 – 31 December 1810) was an English antiquarian and archaeologist.

Cunnington was a self-educated merchant, who developed an interest in the rich archaeological landscape around the Wiltshire village of Heytes ...

, a fossil collector

Fossil collecting (sometimes, in a non-scientific sense, fossil hunting) is the collection of fossils for scientific study, hobby, or profit. Fossil collecting, as practiced by amateurs, is the predecessor of modern paleontology and many stil ...

, for this description as opposed to Owen's conclusions.

In 1848, Gideon Mantell

Gideon Algernon Mantell MRCS FRS (3 February 1790 – 10 November 1852) was a British obstetrician, geologist and palaeontologist. His attempts to reconstruct the structure and life of ''Iguanodon'' began the scientific study of dinosaurs: in ...

read a description of ''Belemnotheutis'' specimens recovered by his son Reginald Neville Mantell to the Royal Society. His descriptions supported that of Pearce's views and held that the differences between belemnites and ''Belemnotheutis'' were enough to justify it being a separate genus. He also described the characteristic groove on the apical dorsal surface of the ''Belemnotheutis'' for the first time (structures which Owen had attributed as artifacts of crushing). He had expected Owen, who was present during the session, to support this amendment. Instead, Owen ridiculed Mantell, further aggravating the famous feud between the two.

Mantell continued to assert his position until his death in 1852, gaining supporters in other eminent paleontologists like Edward Forbes

Edward Forbes FRS, FGS (12 February 1815 – 18 November 1854) was a Manx naturalist. In 1846, he proposed that the distributions of montane plants and animals had been compressed downslope, and some oceanic islands connected to the mainlan ...

and Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known as the author of ''Principles of Geolo ...

against Owen with regards to the true morphology of ''Belemnotheutis''. By then the hostility between Owen and Mantell had escalated, Owen going so far as to oppose the awarding of the Royal Medal to Mantell for his work in 1849. Mantell did eventually receive the Royal Medal for his work on ''Iguanodon

''Iguanodon'' ( ; meaning 'iguana-tooth'), named in 1825, is a genus of iguanodontian dinosaur. While many species have been classified in the genus ''Iguanodon'', dating from the late Jurassic Period to the early Cretaceous Period of Asia, Eu ...

'' to which Owen had attempted to claim another authority much in the same way that he had named ''Belemnotheutis'' after himself.

In 1860, three years after Mantell's death, Owen eventually published an amendment to his earlier descriptions. He acknowledged that ''Belemnotheutis'' indeed had very thin rostra and was distinct from the genus ''Belemnites''. He did so only after other prominent authorities described the very similar '' Acanthoteuthis'' and were considering ''Belemnotheutis'' as its synonym

A synonym is a word, morpheme, or phrase that means exactly or nearly the same as another word, morpheme, or phrase in a given language. For example, in the English language, the words ''begin'', ''start'', ''commence'', and ''initiate'' are all ...

. However, he never recanted his earlier criticism of both Pearce and Mantell.

References

External links

A drawing of ''Belemnotheutis'' drawn in fossil ink

British Geological Survey. {{Taxonbar, from=Q147629 Jurassic cephalopods Prehistoric life of Europe Middle Jurassic genus first appearances Late Jurassic genus extinctions