Battle Of Valcour on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Battle of Valcour Island, also known as the Battle of Valcour Bay, was a naval engagement that took place on October 11, 1776, on

The

The  The American-held strongholds of

The American-held strongholds of

Carleton's fleet, commanded by Captain Thomas Pringle and including 50 unarmed support vessels, sailed onto Lake Champlain on October 9. Stanley (1973), p. 137 They cautiously advanced southward, searching for signs of Arnold's fleet. On the night of October 10, the fleet anchored about to the north of Arnold's position, still unaware of his location. The next day, they continued to sail south, assisted by favorable winds. After they passed the northern tip of Valcour Island, Arnold sent out ''Congress'' and ''Royal Savage'' to draw the attention of the British. Following an inconsequential exchange of fire with the British, the two ships tried to return to Arnold's crescent-shaped firing line. However, ''Royal Savage'' was unable to fight the headwinds, and ran aground on the southern tip of Valcour Island. Miller (1974), p. 173 Some of the British gunboats swarmed toward her, as Captain Hawley and his men hastily abandoned ship. Men from ''Loyal Convert'' boarded her, capturing 20 men in the process, but were then forced to abandon her under heavy fire from the Americans. Bratten (2002), pp. 60–61 Many of Arnold's papers were lost with the destruction of ''Royal Savage'', which was burned by the British. Stanley (1973), p. 142

Carleton's fleet, commanded by Captain Thomas Pringle and including 50 unarmed support vessels, sailed onto Lake Champlain on October 9. Stanley (1973), p. 137 They cautiously advanced southward, searching for signs of Arnold's fleet. On the night of October 10, the fleet anchored about to the north of Arnold's position, still unaware of his location. The next day, they continued to sail south, assisted by favorable winds. After they passed the northern tip of Valcour Island, Arnold sent out ''Congress'' and ''Royal Savage'' to draw the attention of the British. Following an inconsequential exchange of fire with the British, the two ships tried to return to Arnold's crescent-shaped firing line. However, ''Royal Savage'' was unable to fight the headwinds, and ran aground on the southern tip of Valcour Island. Miller (1974), p. 173 Some of the British gunboats swarmed toward her, as Captain Hawley and his men hastily abandoned ship. Men from ''Loyal Convert'' boarded her, capturing 20 men in the process, but were then forced to abandon her under heavy fire from the Americans. Bratten (2002), pp. 60–61 Many of Arnold's papers were lost with the destruction of ''Royal Savage'', which was burned by the British. Stanley (1973), p. 142

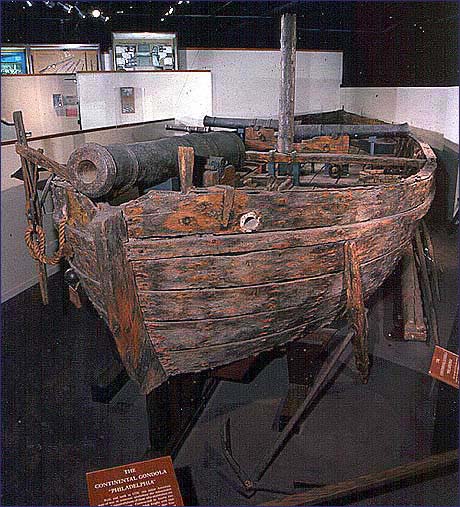

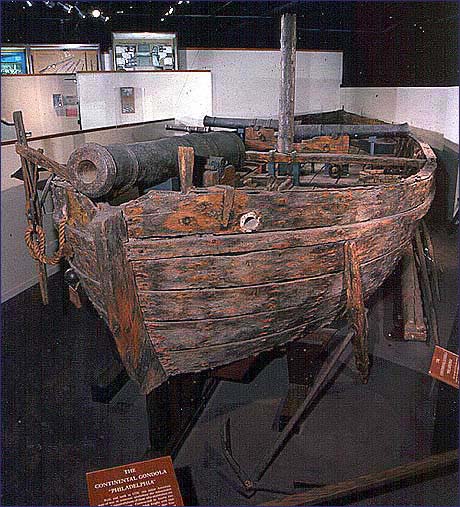

The British gunboats and ''Carleton'' then maneuvered within range of the American line. ''Thunderer'' and ''Maria'' were unable to make headway against the winds, and did not participate in the battle, while ''Inflexible'' eventually came far enough up the strait to participate in the action. Around 12:30 pm, the battle began in earnest, with both sides firing broadsides and cannonades at each other, and continued all afternoon. ''Revenge'' was heavily hit; ''Philadelphia'' was also heavily damaged and eventually sank around 6:30 pm. ''Carleton'', whose guns wrought havoc against the smaller American gundalows, became a focus of attention. A lucky shot eventually snapped the line holding her broadside in position, and she was seriously damaged before she could be towed out of range of the American line. Her casualties were significant; eight men were killed and another eight wounded. Miller (1974), p. 174 The young

The British gunboats and ''Carleton'' then maneuvered within range of the American line. ''Thunderer'' and ''Maria'' were unable to make headway against the winds, and did not participate in the battle, while ''Inflexible'' eventually came far enough up the strait to participate in the action. Around 12:30 pm, the battle began in earnest, with both sides firing broadsides and cannonades at each other, and continued all afternoon. ''Revenge'' was heavily hit; ''Philadelphia'' was also heavily damaged and eventually sank around 6:30 pm. ''Carleton'', whose guns wrought havoc against the smaller American gundalows, became a focus of attention. A lucky shot eventually snapped the line holding her broadside in position, and she was seriously damaged before she could be towed out of range of the American line. Her casualties were significant; eight men were killed and another eight wounded. Miller (1974), p. 174 The young

Arnold then led many of the remaining smaller craft into a small bay on the Vermont shore now named Arnold's Bay 2 miles south of

Arnold then led many of the remaining smaller craft into a small bay on the Vermont shore now named Arnold's Bay 2 miles south of

In the 1930s, Lorenzo Hagglund, a veteran of

In the 1930s, Lorenzo Hagglund, a veteran of "Arnold's Flagship Raised On Old Tar Drums"

''Popular Mechanics'', June 1935 Stored for more than fifty years, the remains were sold by his son to the

Other maritime landmarks

from the National Park Service

** ttps://web.archive.org/web/20131020150159/http://www.historiclakes.org/Valcour/Valcour.html Battle of Valcour Island with pictures*

The Story of Lake Champlain's Valcour Island

of th

{{DEFAULTSORT:Valcour Island, Battle of 1776 in the United States Barges Clinton County, New York Conflicts in 1776 Naval battles of the American Revolutionary War Naval battles of the American Revolutionary War involving the United States Valcour Island Lake Champlain 1776 in New York (state) Valcour Island

Lake Champlain

, native_name_lang =

, image = Champlainmap.svg

, caption = Lake Champlain-River Richelieu watershed

, image_bathymetry =

, caption_bathymetry =

, location = New York/Vermont in the United States; and Quebec in Canada

, coords =

, type =

, ...

. The main action took place in Valcour Bay

Valcour Bay is actually a strait or sound, located between Valcour Island and the west side of Lake Champlain, four miles south of Plattsburgh, New York. It was the site of the Battle of Valcour Island during the American Revolutionary War. It ...

, a narrow strait

A strait is an oceanic landform connecting two seas or two other large areas of water. The surface water generally flows at the same elevation on both sides and through the strait in either direction. Most commonly, it is a narrow ocean channe ...

between the New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

mainland and Valcour Island. The battle is generally regarded as one of the first naval battle

Naval warfare is combat in and on the sea, the ocean, or any other battlespace involving a major body of water such as a large lake or wide river. Mankind has fought battles on the sea for more than 3,000 years. Even in the interior of large lan ...

s of the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, and one of the first fought by the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

. Most of the ships in the American fleet under the command of Benedict Arnold

Benedict Arnold ( Brandt (1994), p. 4June 14, 1801) was an American military officer who served during the Revolutionary War. He fought with distinction for the American Continental Army and rose to the rank of major general before defect ...

were captured or destroyed by a British force under the overall direction of General Guy Carleton. However, the American defense of Lake Champlain stalled British plans to reach the upper Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between N ...

valley.

The Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

had retreated from Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

to Fort Ticonderoga and Fort Crown Point

Fort Crown Point was built by the combined efforts of both British and provincial troops (from New York and the New England Colonies) in North America in 1759 at a narrows on Lake Champlain on what later became the border between New York and Vermo ...

in June 1776 after British forces were massively reinforced. They spent the summer of 1776 fortifying those forts and building additional ships to augment the small American fleet already on the lake. General Carleton had a 9,000 man army at Fort Saint-Jean, but needed to build a fleet to carry it on the lake. The Americans, during their retreat, had either taken or destroyed most of the ships on the lake. By early October, the British fleet, which significantly outgunned the American fleet, was ready for launch.

On October 11, Arnold drew the British fleet to a position he had carefully chosen to limit their advantages. In the battle that followed, many of the American ships were damaged or destroyed. That night, Arnold sneaked the American fleet past the British one, beginning a retreat toward Crown Point and Ticonderoga. Unfavorable weather hampered the American retreat, and more of the fleet was either captured or grounded and burned before it could reach Crown Point. Upon reaching Crown Point Arnold had the fort's buildings burned and retreated to Ticonderoga.

The British fleet included four officers who later became admirals in the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

: Thomas Pringle, James Dacres, Edward Pellew

Admiral Edward Pellew, 1st Viscount Exmouth, GCB (19 April 1757 – 23 January 1833) was a British naval officer. He fought during the American War of Independence, the French Revolutionary Wars, and the Napoleonic Wars. His younger brother ...

, and John Schank. Valcour Bay, the site of the battle, is now a National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the United States government for its outstanding historical significance. Only some 2,500 (~3%) of over 90,000 places listed ...

, as is , which sank shortly after the October 11 battle, and was raised in 1935. The underwater site of , located in 1997, is on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic v ...

.

Background

The

The American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, which began in April 1775 with the Battles of Lexington and Concord

The Battles of Lexington and Concord were the first military engagements of the American Revolutionary War. The battles were fought on April 19, 1775, in Middlesex County, Province of Massachusetts Bay, within the towns of Lexington, Concord ...

, widened in September 1775 when the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

embarked on an invasion of the British Province of Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirteen p ...

. The province was viewed by the Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress was a late-18th-century meeting of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolutionary War. The Congress was creating a new country it first named "United Colonies" and in 1 ...

as a potential avenue for British forces to attack and divide the rebellious colonies and was at the time lightly defended. The invasion reached a peak on December 31, 1775, when the Battle of Quebec ended in disaster for the Americans. In the spring of 1776, 10,000 British and German troops arrived in Quebec, and General Guy Carleton, the provincial governor, drove the Continental Army out of Quebec and back to Fort Ticonderoga.For detailed treatment of the background, see e.g. Stanley (1973) or Morrissey (2003).

Carleton then launched his own offensive intended to reach the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between N ...

, whose navigable length begins south of Lake Champlain and extends down to New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

. Control of the upper Hudson would enable the British to link their forces in Quebec with those in New York, recently captured in the New York campaign by Major General William Howe. This strategy would separate the American colonies of New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

from those farther south and potentially quash the rebellion. Hamilton (1964) pp. 17–18 Lake Champlain, a long and relatively narrow lake formed by the action of glaciers during the last ice age, separates the Green Mountains

The Green Mountains are a mountain range in the U.S. state of Vermont. The range runs primarily south to north and extends approximately from the border with Massachusetts to the border with Quebec, Canada. The part of the same range that is in ...

of Vermont

Vermont () is a state in the northeast New England region of the United States. Vermont is bordered by the states of Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, and New York to the west, and the Canadian province of Quebec to ...

from the Adirondack Mountains

The Adirondack Mountains (; a-də-RÄN-dak) form a massif in northeastern New York with boundaries that correspond roughly to those of Adirondack Park. They cover about 5,000 square miles (13,000 km2). The mountains form a roughly circular ...

of New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

. Its length and maximum width creates more than of shoreline, with many bays, inlets, and promontories. More than 70 islands dot the surface, although during periods of low and high water, these numbers can change. The lake is relatively shallow, with an average depth of . Flowing south to north, the lake empties into the Richelieu River, where waterfalls at Saint-Jean in Quebec mark the northernmost point of navigation.

The American-held strongholds of

The American-held strongholds of Fort Crown Point

Fort Crown Point was built by the combined efforts of both British and provincial troops (from New York and the New England Colonies) in North America in 1759 at a narrows on Lake Champlain on what later became the border between New York and Vermo ...

and Fort Ticonderoga near the lake's southern end protected access to the uppermost navigable reaches of the Hudson River. Elimination of these defenses required the transportation of troops and supplies from the British-controlled St. Lawrence Valley

The St. Lawrence River (french: Fleuve Saint-Laurent, ) is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a (roughly) northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connecting t ...

to the north. Roads were either difficult or nonexistent, making water transport on the lake the best option. Hamilton (1964), pp. 7,8,18 The only ships on the lake after the American retreat from Quebec were a small fleet of lightly armed ships that Benedict Arnold had assembled following the capture of Fort Ticonderoga

The capture of Fort Ticonderoga occurred during the American Revolutionary War on May 10, 1775, when a small force of Green Mountain Boys led by Ethan Allen and Colonel Benedict Arnold surprised and captured the fort's small British garrison. T ...

in May 1775. This fleet, even if it had been in British hands, was too small to transport the large British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

to Fort Ticonderoga. Malcolmson (2001), p. 26

Prelude

During their retreat from Quebec, the Americans carefully took or destroyed all ships on Lake Champlain that might prove useful to the British. When Arnold and his troops, making up the rear guard of the army, abandoned Fort Saint-Jean, they burned or sank all the boats they could not use, and set fire to the sawmill and the fort. These actions effectively denied the British any hope of immediately moving onto the lake. Stanley (1973), pp. 131–132 The two sides set about building fleets: the British at Saint-Jean and the Americans at the other end of the lake in Skenesborough (present-day Whitehall, New York). While planning Quebec's defenses in 1775, General Carleton had anticipated the problem of transportation on Lake Champlain, and had requested the provisioning of prefabricated ships from Europe. By the time Carleton's army reached Saint-Jean, ten such ships had arrived. These ships and more were assembled by skilled shipwrights on the upper Richelieu River. Also assembled there was the ''Inflexible'', a 180-ton warship they disassembled at Quebec City and transported upriver in pieces. Silverstone (2006), p. 15 Stanley (1973), pp. 133–136 In total, the British fleet (25 armed vessels) had more firepower than the Americans' 15 vessels, with more than 80 guns outweighing the 74 smaller American guns. Silverstone (2006), pp. 15–16 Stanley (1973), pp. 137–138 Two of Carleton's ships, ''Inflexible'' (18 12-pounders) and ''Thunderer'' (six 24-pound guns, six 12-pound guns, and two howitzers), by themselves outgunned the combined firepower of the American fleet. Miller (1974), p. 170 In addition to ''Inflexible'' and ''Thunderer'', the fleet included theschooner

A schooner () is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. A common variant, the topsail schoon ...

s , (14 guns), (12 guns), and ''Loyal Convert'' (6 guns), and 20 single-masted gunboats each armed with two cannons.

The American generals leading their shipbuilding effort encountered a variety of challenges. Shipwright

Shipbuilding is the construction of ships and other floating vessels. It normally takes place in a specialized facility known as a shipyard. Shipbuilders, also called shipwrights, follow a specialized occupation that traces its roots to befor ...

was not a common occupation in the relative wilderness of upstate New York, and the Continental Navy

The Continental Navy was the navy of the United States during the American Revolutionary War and was founded October 13, 1775. The fleet cumulatively became relatively substantial through the efforts of the Continental Navy's patron John Adams ...

had to pay extremely high wages to lure skilled craftsmen away from the coast. The carpenters hired to build boats on Lake Champlain were the best-paid employees of the navy, excepting only the Navy's Commodore, Esek Hopkins

Esek Hopkins (April 26, 1718February 26, 1802) was an American naval officer, merchant captain, and privateer. Achieving the rank of Commodore, Hopkins was the only Commander in Chief of the Continental Navy during the American Revolutionary War ...

. Nelson (2006), p. 231 By the end of July there were more than 200 shipwrights at Skenesborough. Nelson (2006), p. 241 In addition to skilled help, materials and supplies specific to maritime use needed to be brought to Skenesborough, where the ships were constructed, or Fort Ticonderoga, where they were fitted out for use. Nelson (2006), p. 239

The shipbuilding at Skenesborough was overseen by Hermanus Schuyler (possibly a relation of Major General Philip Schuyler), and the outfitting was managed by military engineer Jeduthan Baldwin. Schuyler began work in April to produce boats larger and more suitable for combat than the small shallow-draft boats known as bateaux that were used for transport on the lake. The process eventually came to involve General Arnold, who was an experienced ship's captain, and David Waterbury, a Connecticut militia leader with maritime experience. Major General Horatio Gates

Horatio Lloyd Gates (July 26, 1727April 10, 1806) was a British-born American army officer who served as a general in the Continental Army during the early years of the Revolutionary War. He took credit for the American victory in the Battles ...

, in charge of the entire shipbuilding effort, eventually asked Arnold to take more responsibility in the effort, because "I am intirely uninform'd as to Marine Affairs." Nelson (2006), p. 243

Arnold took up the task with relish, and Gates rewarded him with command of the fleet, writing that " rnoldhas a perfect knowledge in maritime affairs, and is, besides, a most gallant and deserving officer." Nelson (2006), p. 245 Arnold's appointment was not without trouble; Jacobus Wynkoop, who had been in command of the fleet, refused to accept that Gates had authority over him and had to be arrested. Nelson (2006), p. 261 The shipbuilding was significantly slowed in mid-August by an outbreak of disease among the shipwrights. Although the army leadership had been scrupulous about keeping smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

sufferers segregated from others, the disease that slowed the shipbuilding for several weeks was some kind of fever. Nelson (2006), pp. 252–253

While both sides busied themselves with shipbuilding, the growing American fleet patrolled the waters of Lake Champlain. At one point in August, Arnold sailed part of the fleet to the northernmost end of the lake, within of Saint-Jean, and formed a battle line. A British outpost, well out of range, fired a few shots at the line without effect. On September 30, expecting the British to sail soon, Arnold retreated to the shelter of Valcour Island. Miller (1974), p. 171 During his patrols of the lake Arnold had commanded the fleet from the schooner

A schooner () is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. A common variant, the topsail schoon ...

, carrying 12 guns and captained by David Hawley

David Hawley (1741–1807) was a captain in the Continental Navy and a privateer during the American Revolutionary War. He commanded in the 1776 Battle of Valcour Island, which is generally regarded as one of the first naval battles of the Amer ...

. When it came time for the battle, Arnold transferred his flag to , a row galley

A row galley was a term used by the early United States Navy for an armed watercraft that used oars rather than sails as a means of propulsion. During the age of sail row galleys had the advantage of propulsion while ships of sail might be stopped ...

. Other ships in the fleet included and , also two-masted schooners carrying 8 guns, as well as , a sloop

A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast typically having only one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft of (behind) the mast. Such an arrangement is called a fore-and-aft rig, and can be rigged as a Bermuda rig with triangular sa ...

(12 guns), and 8 gundalows outfitted as gunboats (each with three guns): , , , , , ''Connecticut'', ''Jersey'', , the cutter ''Lee'', and the row galleys and . ''Liberty'' was not present at the battle, having been sent to Ticonderoga for provisions. Malcolmson (2001), pp. 29–33 Miller (1974), pp. 169, 172 Bratten (2002), p. 57

Arnold, whose business activities before the war had included sailing ships to Europe and the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

, carefully chose the site where he wanted to meet the British fleet. Miller (1974), pp. 166,171 Reliable intelligence he received on October 1 indicated that the British had a force significantly more powerful than his. Bratten (2002), p. 56 Because his force was inferior, he chose the narrow, rocky body of water between the western shore of Lake Champlain and Valcour Island (near modern Plattsburgh, New York

Plattsburgh ( moh, Tsi ietsénhtha) is a city in, and the seat of, Clinton County, New York, United States, situated on the north-western shore of Lake Champlain. The population was 19,841 at the 2020 census. The population of the surrounding ...

), where the British fleet would have difficulty bringing its superior firepower to bear, and where the inferior seamanship of his relatively unskilled sailors would have a minimal negative effect. Stanley (1973), p. 141 Some of Arnold's captains wanted to fight in open waters where they might be able to retreat to the shelter of Fort Crown Point, but Arnold argued that the primary purpose of the fleet was not survival but the delay of a British advance on Crown Point and Ticonderoga until the following spring. Miller (1974), p. 172

Battle

Carleton's fleet, commanded by Captain Thomas Pringle and including 50 unarmed support vessels, sailed onto Lake Champlain on October 9. Stanley (1973), p. 137 They cautiously advanced southward, searching for signs of Arnold's fleet. On the night of October 10, the fleet anchored about to the north of Arnold's position, still unaware of his location. The next day, they continued to sail south, assisted by favorable winds. After they passed the northern tip of Valcour Island, Arnold sent out ''Congress'' and ''Royal Savage'' to draw the attention of the British. Following an inconsequential exchange of fire with the British, the two ships tried to return to Arnold's crescent-shaped firing line. However, ''Royal Savage'' was unable to fight the headwinds, and ran aground on the southern tip of Valcour Island. Miller (1974), p. 173 Some of the British gunboats swarmed toward her, as Captain Hawley and his men hastily abandoned ship. Men from ''Loyal Convert'' boarded her, capturing 20 men in the process, but were then forced to abandon her under heavy fire from the Americans. Bratten (2002), pp. 60–61 Many of Arnold's papers were lost with the destruction of ''Royal Savage'', which was burned by the British. Stanley (1973), p. 142

Carleton's fleet, commanded by Captain Thomas Pringle and including 50 unarmed support vessels, sailed onto Lake Champlain on October 9. Stanley (1973), p. 137 They cautiously advanced southward, searching for signs of Arnold's fleet. On the night of October 10, the fleet anchored about to the north of Arnold's position, still unaware of his location. The next day, they continued to sail south, assisted by favorable winds. After they passed the northern tip of Valcour Island, Arnold sent out ''Congress'' and ''Royal Savage'' to draw the attention of the British. Following an inconsequential exchange of fire with the British, the two ships tried to return to Arnold's crescent-shaped firing line. However, ''Royal Savage'' was unable to fight the headwinds, and ran aground on the southern tip of Valcour Island. Miller (1974), p. 173 Some of the British gunboats swarmed toward her, as Captain Hawley and his men hastily abandoned ship. Men from ''Loyal Convert'' boarded her, capturing 20 men in the process, but were then forced to abandon her under heavy fire from the Americans. Bratten (2002), pp. 60–61 Many of Arnold's papers were lost with the destruction of ''Royal Savage'', which was burned by the British. Stanley (1973), p. 142

The British gunboats and ''Carleton'' then maneuvered within range of the American line. ''Thunderer'' and ''Maria'' were unable to make headway against the winds, and did not participate in the battle, while ''Inflexible'' eventually came far enough up the strait to participate in the action. Around 12:30 pm, the battle began in earnest, with both sides firing broadsides and cannonades at each other, and continued all afternoon. ''Revenge'' was heavily hit; ''Philadelphia'' was also heavily damaged and eventually sank around 6:30 pm. ''Carleton'', whose guns wrought havoc against the smaller American gundalows, became a focus of attention. A lucky shot eventually snapped the line holding her broadside in position, and she was seriously damaged before she could be towed out of range of the American line. Her casualties were significant; eight men were killed and another eight wounded. Miller (1974), p. 174 The young

The British gunboats and ''Carleton'' then maneuvered within range of the American line. ''Thunderer'' and ''Maria'' were unable to make headway against the winds, and did not participate in the battle, while ''Inflexible'' eventually came far enough up the strait to participate in the action. Around 12:30 pm, the battle began in earnest, with both sides firing broadsides and cannonades at each other, and continued all afternoon. ''Revenge'' was heavily hit; ''Philadelphia'' was also heavily damaged and eventually sank around 6:30 pm. ''Carleton'', whose guns wrought havoc against the smaller American gundalows, became a focus of attention. A lucky shot eventually snapped the line holding her broadside in position, and she was seriously damaged before she could be towed out of range of the American line. Her casualties were significant; eight men were killed and another eight wounded. Miller (1974), p. 174 The young Edward Pellew

Admiral Edward Pellew, 1st Viscount Exmouth, GCB (19 April 1757 – 23 January 1833) was a British naval officer. He fought during the American War of Independence, the French Revolutionary Wars, and the Napoleonic Wars. His younger brother ...

, serving as a midshipman

A midshipman is an officer of the lowest rank, in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Canada (Naval Cadet), Australia, Bangladesh, Namibia, New Zealand, South Afr ...

aboard ''Carleton'', distinguished himself by ably commanding the vessel to safety when its senior officers, including its captain, Lieutenant James Dacres, were injured. Hamilton (1964), p. 157 Another lucky American shot hit a British gunboat's magazine and the vessel exploded. Miller (1974), p. 175

Toward sunset, ''Inflexible'' finally reached the action. Her big guns quickly silenced most of Arnold's fleet. The British also began landing Native allies on both Valcour Island and the lakeshore, in order to deny the Americans the possibility of retreating to land. As darkness fell, the American fleet retreated, and the British called off the attack, in part because some boats had run out of ammunition. Lieutenant James Hadden, commanding one of the British gunboats, noted that "little more than one third of the British Fleet" saw much action that day.

Retreat

When the sun set on October 11, the battle had clearly gone against the Americans. Most of the American ships were damaged or sinking, and the crews reported around 60 casualties. The British reported around 40 casualties on their ships. Aware that he could not defeat the British fleet, Arnold decided to try reaching the cover of Fort Crown Point, about to the south. Under the cover of a dark and foggy night, the fleet, with muffled oars and minimal illumination, threaded its way through a gap about one mile (1.6 km) wide between the British ships and the western shore, where Indian campfires burned. Nelson (2006), pp. 307–309 By morning, they had reachedSchuyler Island

Schuyler Island, also known as Schuylers Island or Whitney Island, is a uninhabited island in Lake Champlain. It is a part of the Chesterfield, New York, Town of Chesterfield in Essex County, New York, Essex County, New York (state), New York, loc ...

, about south. Carleton, upset that the Americans had escaped him, immediately sent his fleet around Valcour Island to find them. Realizing the Americans were not there, he regrouped his fleet and sent scouts to find Arnold. Miller (1974), p. 176

Adverse winds as well as damaged and leaky boats slowed the American fleet's progress. At Schuyler Island, ''Providence'' and ''Jersey'' were sunk or burned, and crude repairs were effected to other vessels. The cutter ''Lee'' was also abandoned on the western shore and eventually taken by the British. Bratten (2002), p. 67 Around 2:00 pm, the fleet sailed again, trying to make headway against biting winds, rain, and sleet. By the following morning, the ships were still more than from Crown Point, and the British fleet's masts were visible on the horizon. When the wind finally changed, the British had its advantage first. They closed once again, opening fire on ''Congress'' and ''Washington'', which were in the rear of the American fleet. Arnold first decided to attempt grounding the slower gunboats at Split Rock, short of Crown Point. ''Washington'', however, was too badly damaged and too slow to make it, and she was forced to strike her colors and surrender; 110 men were taken prisoner. Miller (1974), p. 177

Arnold then led many of the remaining smaller craft into a small bay on the Vermont shore now named Arnold's Bay 2 miles south of

Arnold then led many of the remaining smaller craft into a small bay on the Vermont shore now named Arnold's Bay 2 miles south of Buttonmold Bay

Button Bay, previously known as Button Mould Bay or Buttonmold Bay, is an area of shallow water on the east shore of Lake Champlain. It is located in the town of Ferrisburgh (near Vergennes), in Addison County. It is situated between the Green ...

, where the waters were too shallow for the larger British vessels to follow. These boats were then run aground, stripped, and set on fire, with their flags still flying. Arnold, the last to land, personally torched his flagship ''Congress''. Bratten (2002), p. 69 The surviving ships' crews, numbering about 200, then made their way overland to Crown Point, narrowly escaping an Indian ambush. There they found ''Trumbull'', ''New York'', ''Enterprise'', and ''Revenge'', all of which had escaped the British fleet, as well as ''Liberty'', which had just arrived with supplies from Ticonderoga. Bratten (2002), p. 70

Aftermath

Arnold, convinced that Crown Point was no longer viable as a point of defense against the large British force, destroyed and abandoned the fort, moving the forces stationed there to Ticonderoga. General Carleton, rather than shipping his prisoners back to Quebec, returned them to Ticonderoga under a flag of truce. On their arrival, the released men were so effusive in their praise of Carleton that they were sent home to prevent the desertion of other troops. With control of the lake, the British landed troops and occupied Crown Point the next day. They remained for two weeks, pushing scouting parties to within three miles (4.8 km) of Ticonderoga. Stanley (1973), p. 144 The battle-season was getting late as the first snow began to fall on October 20 and his supply line would be difficult to manage in winter, so Carleton decided to withdraw north to winter quarters; Arnold's plan of delay had succeeded. Baron Riedesel, commanding the Hessians in Carleton's army, noted that, "If we could have begun our expedition four weeks earlier, I am satisfied that everything could have ended this year." Miller (1974), p. 179 The 1777 British campaign, led by General John Burgoyne, was halted by Continental forces, some led with vigor by General Arnold, in theBattles of Saratoga

The Battles of Saratoga (September 19 and October 7, 1777) marked the climax of the Saratoga campaign, giving a decisive victory to the Americans over the British in the American Revolutionary War. British General John Burgoyne led an invasion ...

. Burgoyne's subsequent surrender paved the way for the entry of France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

into the war as an American ally.

The captains of ''Maria'', ''Inflexible'', and ''Loyal Convert'' wrote a letter criticizing Captain Pringle for making Arnold's escape possible by failing to properly blockade the channel, and for not being more aggressive in directing the battle. Apparently the letter did not cause any career problems for Pringle or its authors; he and John Schank, captain of ''Inflexible'', became admirals, as did midshipman Pellew and Lieutenant Dacres. Hamilton (1964), p. 160 Carleton was awarded the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I of Great Britain, George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate medieval ceremony for appointing a knight, which involved Bathing#Medieval ...

by King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

for his success at Valcour Island. On December 31, 1776, one year after the Battle of Quebec, a mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different elementar ...

was held in celebration of the British success, and Carleton threw a grand ball.

The loss of Benedict Arnold's papers aboard ''Royal Savage'' was to have important consequences later in his career. For a variety of reasons, Congress ordered an inquiry into his conduct of the Quebec campaign, which included a detailed look at his claims for compensation. The inquiry took place in late 1779, when Arnold was in military command of Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

and recuperating from serious wounds received at Saratoga. Congress found that he owed it money since he could not produce receipts for expenses he claimed to have paid from his own funds. Although Arnold had already been secretly negotiating with the British over a change of allegiance since May 1779, this news contributed to his decision to resign the command of Philadelphia. His next command was West Point, which he sought with the intention of facilitating its surrender to the British. His plot was however exposed in September 1780, at which time he fled to the British in New York City.

Legacy

In the 1930s, Lorenzo Hagglund, a veteran of

In the 1930s, Lorenzo Hagglund, a veteran of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and a history buff, began searching the strait for remains of the battle. In 1932 he found the remains of ''Royal Savage''s hull, which he successfully raised in 1934. Bratten (2002), p. 75''Popular Mechanics'', June 1935 Stored for more than fifty years, the remains were sold by his son to the

National Civil War Museum

The National Civil War Museum, located at One Lincoln Circle at Reservoir Park in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, is a permanent, nonprofit educational institution created to promote the preservation of material culture and sources of information t ...

. Bratten (2002), p. 76 As of March 2009, the remains were in a city garage in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

Harrisburg is the capital city of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Dauphin County. With a population of 50,135 as of the 2021 census, Harrisburg is the 9th largest city and 15th largest municipality in Pe ...

. The city of Plattsburgh, New York

Plattsburgh ( moh, Tsi ietsénhtha) is a city in, and the seat of, Clinton County, New York, United States, situated on the north-western shore of Lake Champlain. The population was 19,841 at the 2020 census. The population of the surrounding ...

, has claimed ownership of the remains and would like them returned to upstate New York. "War Ship Remains Piled in City Garage"

In 1935 Hagglund followed up his discovery of ''Royal Savage'' with the discovery of ''Philadelphia''s remains, sitting upright on the lake bottom. Bratten (2002), p. 77 He raised her that year; she is now on display at the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

's National Museum of American History

The National Museum of American History: Kenneth E. Behring Center collects, preserves, and displays the heritage of the United States in the areas of social, political, cultural, scientific, and military history. Among the items on display is t ...

in Washington, D.C., and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic v ...

and is designated a National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the United States government for its outstanding historical significance. Only some 2,500 (~3%) of over 90,000 places listed ...

. NHL Description of USS Philadelphia The site of the battle, Valcour Bay

Valcour Bay is actually a strait or sound, located between Valcour Island and the west side of Lake Champlain, four miles south of Plattsburgh, New York. It was the site of the Battle of Valcour Island during the American Revolutionary War. It ...

, was declared a National Historic Landmark on January 1, 1961, and added to the National Register on October 15, 1966. A small stone monument commemorating the battle sits on the mainland along U.S. Route 9

U.S. Route 9 (US 9) is a north–south United States highway in the states of Delaware, New Jersey, and New York in the Northeastern United States. It is one of only two U.S. Highways with a ferry connection (the Cape May–Lewes Ferry, between ...

overlooking Valcour Island.National Register Information System

The National Register Information System (NRIS) is a database of properties that have been listed on the United States National Register of Historic Places. The database includes more than 84,000 entries of historic sites that are currently listed ...

NHL Description of Valcour Bay

In 1997 another pristine underwater wreck was located during a survey by the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum

The Lake Champlain Maritime Museum (LCMM) is a non-profit museum located in Vergennes, Vermont, US. It preserves and shares the history and archaeology of Lake Champlain. As a maritime museum practicing archaeology, LCMM studies the shipwrecks ...

. Two years later it was conclusively identified as the gundalow ''Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire is a British single-seat fighter aircraft used by the Royal Air Force and other Allied countries before, during, and after World War II. Many variants of the Spitfire were built, from the Mk 1 to the Rolls-Royce Griff ...

''; this site was listed on the National Register in 2008, and it has been named as part of the U.S. government's Save America's Treasures program. Shipwrecks of Lake Champlain: Gunboat Spitfire

Order of battle

See also

* List of American Revolutionary War battles * American Revolutionary War §Early Engagements. The Battle of Valcour Island placed in sequence and strategic context.Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * (This book is primarily about Arnold's service on the American side in the Revolution, giving overviews of the periods before the war and after he changes sides.) * * (This work contains detailed specifications for most of the watercraft used in this action, as well as copies of draft documents for some of them.) * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

*External links

*Other maritime landmarks

from the National Park Service

** ttps://web.archive.org/web/20131020150159/http://www.historiclakes.org/Valcour/Valcour.html Battle of Valcour Island with pictures*

The Story of Lake Champlain's Valcour Island

of th

{{DEFAULTSORT:Valcour Island, Battle of 1776 in the United States Barges Clinton County, New York Conflicts in 1776 Naval battles of the American Revolutionary War Naval battles of the American Revolutionary War involving the United States Valcour Island Lake Champlain 1776 in New York (state) Valcour Island