Battle Of Meligalas on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Battle of Meligalas ( el, Μάχη του Μελιγαλά, Machi tou Meligala) took place at

In the meantime, after the

In the meantime, after the  In 1943, the German commanders in Greece concluded that their own forces were insufficient to suppress ELAS. As a result, and in order to "spare German blood", the decision was taken to recruit the anti-communist elements of Greek society to fight EAM. Apart from the "

In 1943, the German commanders in Greece concluded that their own forces were insufficient to suppress ELAS. As a result, and in order to "spare German blood", the decision was taken to recruit the anti-communist elements of Greek society to fight EAM. Apart from the " After suffering some early blows, ELAS managed to recover its influence, and from 1944 conducted constant sabotage on the supply routes used by the German army. In April 1944, ELAS for the first time attacked a town held by a German garrison at Meligalas, but the assault was beaten back. In the same month, EAM leader

After suffering some early blows, ELAS managed to recover its influence, and from 1944 conducted constant sabotage on the supply routes used by the German army. In April 1944, ELAS for the first time attacked a town held by a German garrison at Meligalas, but the assault was beaten back. In the same month, EAM leader

During the last months of the German occupation, Walter Blume, the head of the German security police ( SD) developed the so-called "chaos thesis", involving not only a thorough

During the last months of the German occupation, Walter Blume, the head of the German security police ( SD) developed the so-called "chaos thesis", involving not only a thorough

The end of the battle was followed by the invasion of Meligalas by civilians, and an unchecked plunder and massacre. According to a contemporary report preserved in the archives of the Communist Party of Greece (KKE), these were inhabitants of the village of Skala, which had been torched by the German army. Among the captive Battalionists held in the bedesten, Velouchiotis—who arrived at Meligalas shortly after the end of the battle with his personal escort—recognized a gendarme whom he had previously arrested and then released, and ordered his execution. The first reprisal wave, tacitly encouraged by ELAS through the deliberately loose guarding of its captives, was followed by a series of organized executions.

A partisan court martial was set up in the town, headed by the lawyers

The end of the battle was followed by the invasion of Meligalas by civilians, and an unchecked plunder and massacre. According to a contemporary report preserved in the archives of the Communist Party of Greece (KKE), these were inhabitants of the village of Skala, which had been torched by the German army. Among the captive Battalionists held in the bedesten, Velouchiotis—who arrived at Meligalas shortly after the end of the battle with his personal escort—recognized a gendarme whom he had previously arrested and then released, and ordered his execution. The first reprisal wave, tacitly encouraged by ELAS through the deliberately loose guarding of its captives, was followed by a series of organized executions.

A partisan court martial was set up in the town, headed by the lawyers

In an ELAS communique of 26 September 1944, Major General

In an ELAS communique of 26 September 1944, Major General

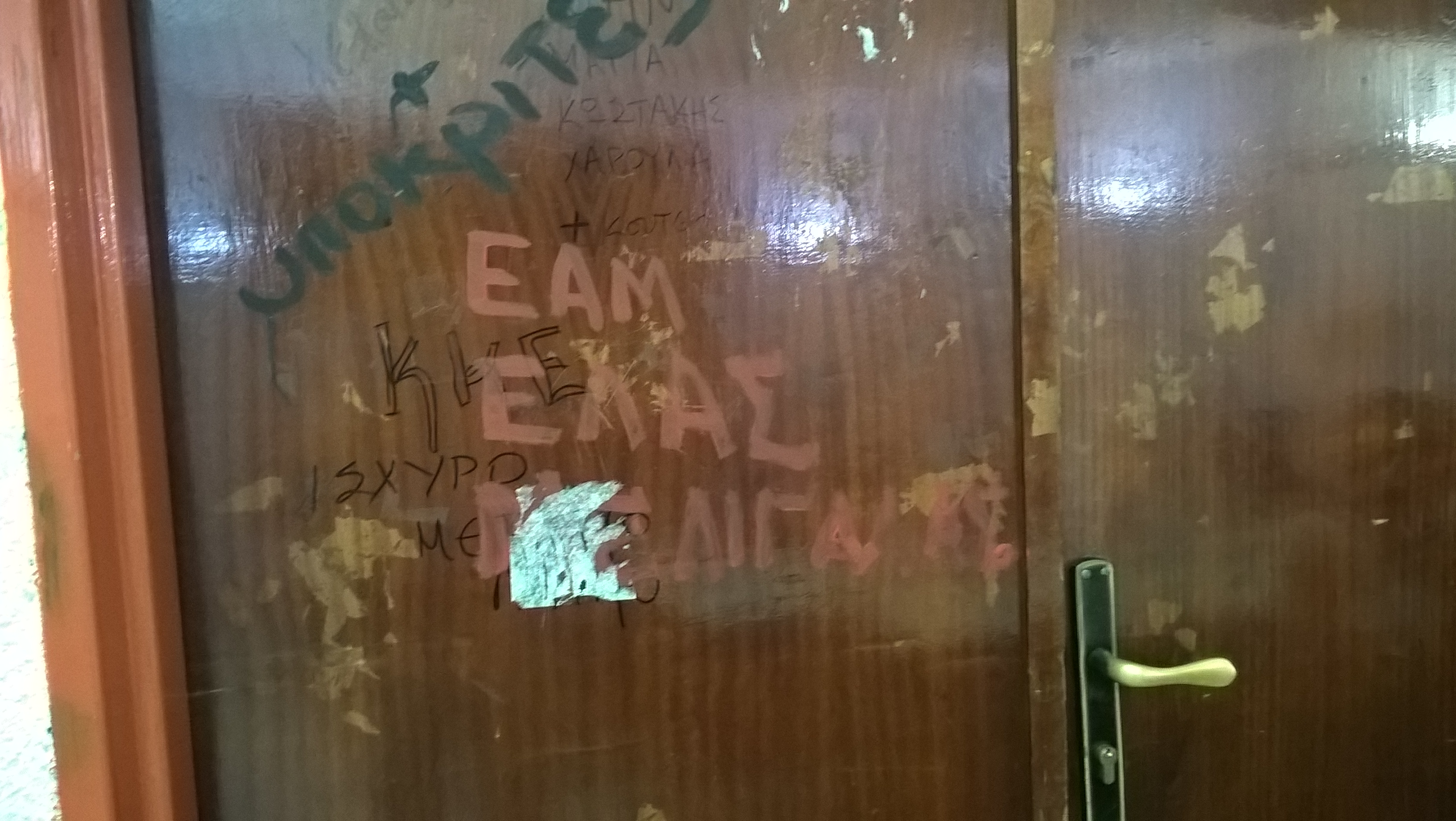

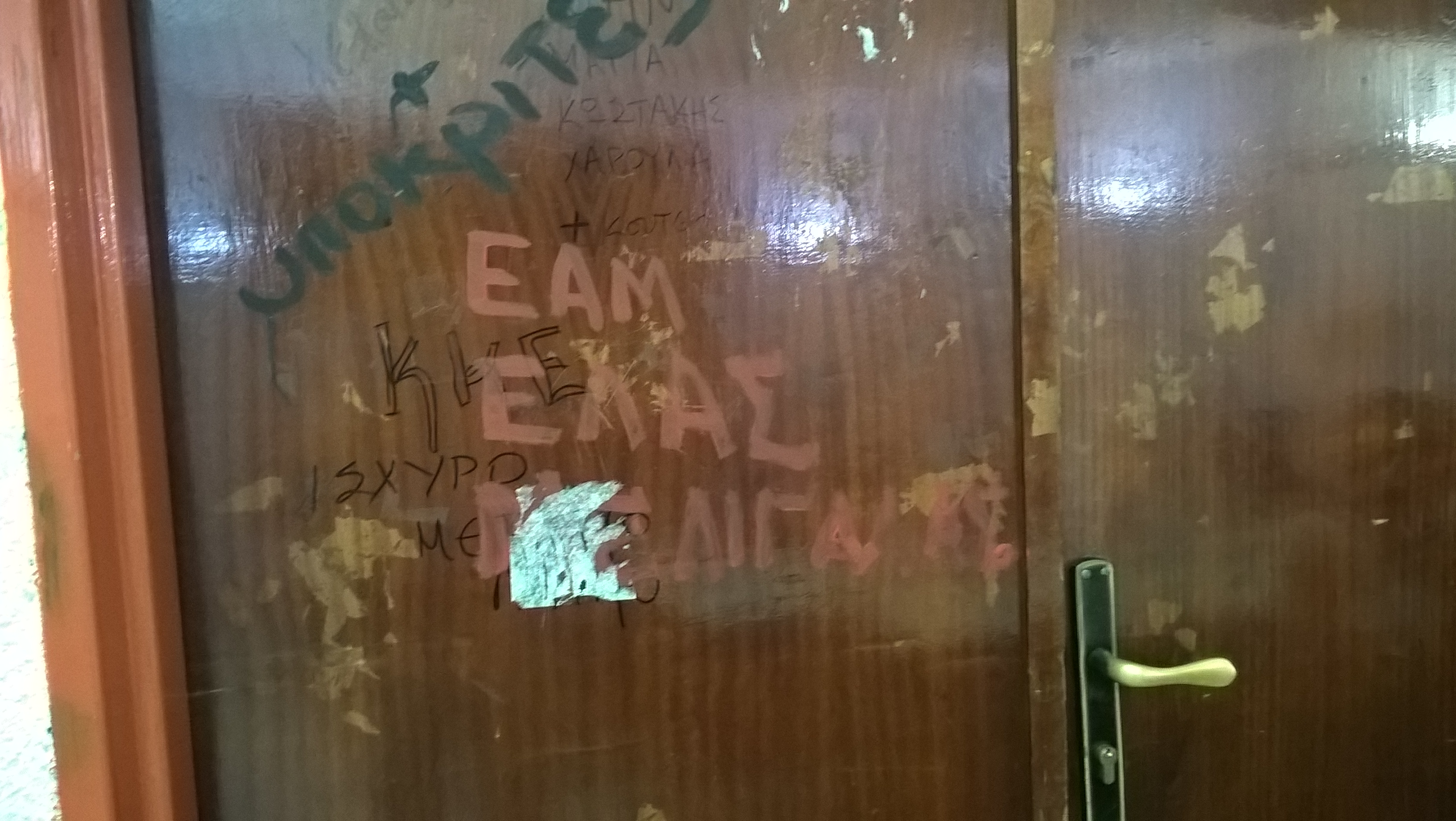

In the early 1980s, the Meligalas events became a point of reference in confrontations between university students close to the and the Leftist Clusters on the one side and the right-wing ONNED youth organization and its student wing, DAP-NDFK. After the PASOK government officially recognized EAM's contribution in the Greek Resistance in 1982, "Rigas Feraios" members coined the slogan "EAM-ELAS-Meligalas" ("ΕΑΜ-ΕΛΑΣ-Μελιγαλάς") as a counter to the positive portrayal of the Battalionists by the right-wing groups. The slogan remained current in the university students' conference of 1992, following Civil War-era and anti-communist slogans used by DAP. In the late 2000s, when the political slogans and rhetoric of the 1940s increasingly resurfaced in Greek political discourse, and with Golden Dawn's entry into the

In the early 1980s, the Meligalas events became a point of reference in confrontations between university students close to the and the Leftist Clusters on the one side and the right-wing ONNED youth organization and its student wing, DAP-NDFK. After the PASOK government officially recognized EAM's contribution in the Greek Resistance in 1982, "Rigas Feraios" members coined the slogan "EAM-ELAS-Meligalas" ("ΕΑΜ-ΕΛΑΣ-Μελιγαλάς") as a counter to the positive portrayal of the Battalionists by the right-wing groups. The slogan remained current in the university students' conference of 1992, following Civil War-era and anti-communist slogans used by DAP. In the late 2000s, when the political slogans and rhetoric of the 1940s increasingly resurfaced in Greek political discourse, and with Golden Dawn's entry into the

Meligalas

Meligalas ( el, Μελιγαλάς) is a town and former municipality in Messenia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Oichalia, of which it is a municipal unit. The municipal unit has an are ...

in Messenia

Messenia or Messinia ( ; el, Μεσσηνία ) is a regional unit (''perifereiaki enotita'') in the southwestern part of the Peloponnese region, in Greece. Until the implementation of the Kallikratis plan on 1 January 2011, Messenia was a ...

in southwestern Greece, on 13–15 September 1944, between the Greek Resistance forces of the Greek People's Liberation Army

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

(ELAS) and the collaborationist Security Battalions

The Security Battalions ( el, Τάγματα Ασφαλείας, Tagmata Asfaleias, derisively known as ''Germanotsoliades'' (Γερμανοτσολιάδες) or ''Tagmatasfalites'' (Ταγματασφαλίτες)) were Greek Collaboration with ...

.

During the Axis occupation of Greece, ELAS partisan

Partisan may refer to:

Military

* Partisan (weapon), a pole weapon

* Partisan (military), paramilitary forces engaged behind the front line

Films

* ''Partisan'' (film), a 2015 Australian film

* ''Hell River'', a 1974 Yugoslavian film also know ...

forces began operating in the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic regions of Greece, geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmu ...

from 1942, and in 1943 began to establish their control over the area. To confront them, the German occupation authorities formed the Security Battalions, which took part not only in anti-guerrilla operations but also in mass reprisals against the local civilian population. With the liberation of Greece drawing near in 1944, the Security Battalions were increasingly targeted by ELAS.

Following the withdrawal of German forces from the Peloponnese in September 1944, a part of the collaborationist forces in Kalamata

Kalamáta ( el, Καλαμάτα ) is the second most populous city of the Peloponnese peninsula, after Patras, in southern Greece and the largest city of the homonymous administrative region. As the capital and chief port of the Messenia reg ...

withdrew to Meligalas, where a force of about 1,000 Battalionists gathered. There they were quickly surrounded by ELAS detachments, some 1,200 strong. After a three-day battle, the ELAS partisans broke through the fortifications and entered the town. The ELAS victory was followed by a massacre, during which prisoners and civilians were executed near a well. The number of executed people is variously estimated at between 700 and 1,100 on different counts. After news of the massacre spread, the leadership of ELAS and of its political parent group, the National Liberation Front (EAM) took steps to ensure a peaceful transition of power

A peaceful transition or transfer of power is a concept important to democratic governments in which the leadership of a government peacefully hands over control of government to a newly-elected leadership. This may be after elections or during t ...

in most of the country, limiting reprisal occurrences.

During the post-war period and following the Greek Civil War

The Greek Civil War ( el, ο Eμφύλιος �όλεμος ''o Emfýlios'' 'Pólemos'' "the Civil War") took place from 1946 to 1949. It was mainly fought against the established Kingdom of Greece, which was supported by the United Kingdom ...

, the ruling right-wing establishment immortalized the Meligalas massacre as evidence of communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

brutality, and memorialized the victims as patriotic heroes. Following the ''Metapolitefsi

The Metapolitefsi ( el, Μεταπολίτευση, , " regime change") was a period in modern Greek history from the fall of the Ioaniddes military junta of 1973–74 to the transition period shortly after the 1974 legislative elections.

The m ...

'', the official support of this commemoration ceased. The massacre continues to be commemorated by the descendants and ideological sympathizers of the Security Battalions, and remains a point of reference and a rallying cry both for the far right

Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are political beliefs and actions further to the right of the left–right political spectrum than the standard political right, particularly in terms of being ...

and the left

Left may refer to:

Music

* ''Left'' (Hope of the States album), 2006

* ''Left'' (Monkey House album), 2016

* "Left", a song by Nickelback from the album ''Curb'', 1996

Direction

* Left (direction), the relative direction opposite of right

* L ...

in Greece.

Political and military background

Emergence of the Resistance in occupied Messenia

Following theGerman invasion of Greece

The German invasion of Greece, also known as the Battle of Greece or Operation Marita ( de , Unternehmen Marita, links = no), was the attack of Greece by Italy and Germany during World War II. The Italian invasion in October 1940, which is usu ...

in April 1941, Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

desired to quickly extricate German forces for the impending invasion

An invasion is a military offensive in which large numbers of combatants of one geopolitical entity aggressively enter territory owned by another such entity, generally with the objective of either: conquering; liberating or re-establishing con ...

of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

. As a result, the largest portion of the occupied country, including the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic regions of Greece, geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmu ...

, came under Italian military control. Western Thrace

Western Thrace or West Thrace ( el, �υτικήΘράκη, '' ytikíThráki'' ; tr, Batı Trakya; bg, Западна/Беломорска Тракия, ''Zapadna/Belomorska Trakiya''), also known as Greek Thrace, is a Geography, geograp ...

and eastern Macedonia came under Bulgarian control, and various strategically important areas (notably Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

and Piraeus

Piraeus ( ; el, Πειραιάς ; grc, Πειραιεύς ) is a port city within the Athens urban area ("Greater Athens"), in the Attica region of Greece. It is located southwest of Athens' city centre, along the east coast of the Saronic ...

, Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, and ...

, and Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area, and the capi ...

with Central Macedonia

Central Macedonia ( el, Κεντρική Μακεδονία, Kentrikí Makedonía, ) is one of the thirteen administrative regions of Greece, consisting of the central part of the geographical and historical region of Macedonia. With a populat ...

) remained under German control.

In the Kalamata Province

Kalamáta ( el, Καλαμάτα ) is the second most populous city of the Peloponnese peninsula, after Patras, in southern Greece and the largest city of the homonymous administrative region. As the capital and chief port of the Messenia reg ...

, the nascent communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

-led National Liberation Front (EAM) began its activity in 1942, promoting passive resistance

Nonviolent resistance (NVR), or nonviolent action, sometimes called civil resistance, is the practice of achieving goals such as social change through symbolic protests, civil disobedience, economic or political noncooperation, satyagraha, const ...

to the unpopular confiscation of crops by the Italian military authorities, and began the first steps to form partisan

Partisan may refer to:

Military

* Partisan (weapon), a pole weapon

* Partisan (military), paramilitary forces engaged behind the front line

Films

* ''Partisan'' (film), a 2015 Australian film

* ''Hell River'', a 1974 Yugoslavian film also know ...

troops. The first left-wing groups formed across the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic regions of Greece, geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmu ...

; their engagements were limited to skirmishes with the Greek Gendarmerie

The Hellenic Gendarmerie (, ''Elliniki Chorofylaki'') was the national gendarmerie and military police (until 1951) force of Greece.

History

19th century

The Greek Gendarmerie was established after the enthronement of King Otto in 1833 as the ...

and the Italian Army, and by late 1942 they were almost all either destroyed or forced to evacuate to Central Greece

Continental Greece ( el, Στερεά Ελλάδα, Stereá Elláda; formerly , ''Chérsos Ellás''), colloquially known as Roúmeli (Ρούμελη), is a traditional geographic region of Greece. In English, the area is usually called Central ...

. In April 1943, when the Peloponnese was considered "partisan-free" by the occupation authorities, the wing commander

Wing commander (Wg Cdr in the RAF, the IAF, and the PAF, WGCDR in the RNZAF and RAAF, formerly sometimes W/C in all services) is a senior commissioned rank in the British Royal Air Force and air forces of many countries which have historical ...

Dimitris Michas Dimitris (Δημήτρης) is the Modern Greek form of the older forms Demetrios, Dimitrios (Δημήτριος, usually Latinized as Demetrius) and may refer to:

*Dimitris Arvanitis (born 1980), Greek professional football defender who plays for ...

, who had previously been imprisoned by the Italians, formed a new partisan group on orders from EAM. Following his first successes, and with the arrival of reinforcements requested from the mainland, the group grew and began openly attacking Italian soldiers and their Greek informants. By June 1943, the number of Greek People's Liberation Army

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

(ELAS) partisans in the Peloponnese reached about 500 men in total. Due to the lack of a central command and the difficulties of communication, they were dispersed and operated as quasi-autonomous groups. In August 1943, according to a German intelligence report, partisan activity spiked in the mountainous areas of Messenia, where 800 men under Kostas Kanellopoulos operated.

In early 1943, the "Hellenic Army

The Hellenic Army ( el, Ελληνικός Στρατός, Ellinikós Stratós, sometimes abbreviated as ΕΣ), formed in 1828, is the land force of Greece. The term ''Hellenic'' is the endogenous synonym for ''Greek''. The Hellenic Army is the ...

" (ES), formed by mostly royalist former officers, was established as a Resistance group and formed its own small armed groups, which clashed with the Italians. Initially it declared itself a politically independent and neutral force, but after forging ties with royalist networks chiefly in the area and in Athens, it shifted to an anti-EAM stance by July. The British made efforts to unify the local Resistance groups in the Peloponnese, but these failed, and in August 1943 ES clashed with ELAS, while some of its most prominent leaders, such as and possibly also Tilemachos Vrettakos, respectively sought collaboration with the Italian and German occupation authorities against ELAS. However, the apparent delay of German assistance, the losses suffered by Vrettakos' men in a clash with a German force at , and the cessation of Allied air drops to both ES and ELAS, resulted in the defeat and dissolution of the former at the hands of the latter in October. This left EAM/ELAS as the sole organized Resistance force in the Peloponnese.

German takeover and the establishment of the Security Battalions

In the meantime, after the

In the meantime, after the Italian capitulation

The Armistice of Cassibile was an armistice signed on 3 September 1943 and made public on 8 September between the Kingdom of Italy and the Allies during World War II.

It was signed by Major General Walter Bedell Smith for the Allies and Brig ...

in September 1943, the overall command of anti-partisan operations in the southern Peloponnese fell to the German major general Karl von Le Suire __NOTOC__

Karl Hans Maximilian von Le Suire (8 November 1898 – 18 June 1954) was a German general during World War II who commanded the XXXXIX Mountain Corps. He was responsible for the Massacre of Kalavryta, in Greece.

Life and career

Karl von ...

, commander of the 117th Jäger Division, which had been moved to the area in July. In October, Le Suire was named the sole military commander in the Peloponnese. The town of Meligalas

Meligalas ( el, Μελιγαλάς) is a town and former municipality in Messenia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Oichalia, of which it is a municipal unit. The municipal unit has an are ...

in northern Messenia, which under Italian occupation had housed a Carabinieri

The Carabinieri (, also , ; formally ''Arma dei Carabinieri'', "Arm of Carabineers"; previously ''Corpo dei Carabinieri Reali'', "Royal Carabineers Corps") are the national gendarmerie of Italy who primarily carry out domestic and foreign polic ...

station, now became the seat of two German infantry companies. The Italian capitulation led to the immediate and considerable reinforcement of ELAS in morale, personnel, and materiel, and with British support ELAS forces began attacking German targets. In the mountainous districts of the Peloponnese, representatives of EAM/ELAS translated their monopoly of armed resistance into the exercise of authority, but faced difficulties with the mostly conservative and royalist local population. Peasant disaffection was further fuelled by the requirement to feed the partisans amidst conditions of malnourishment and a general disruption of the agricultural production caused by the mounting hyperinflation

In economics, hyperinflation is a very high and typically accelerating inflation. It quickly erodes the real value of the local currency, as the prices of all goods increase. This causes people to minimize their holdings in that currency as t ...

and by the large-scale German anti-partisan sweeps (''Säuberungen''). These operations involved reprisals against the civilian population, following a July order of the commander of the LXVIII Corps, Hellmuth Felmy

Hellmuth Felmy (28 May 1885 – 14 December 1965) was a German general and war criminal during World War II, commanding forces in occupied Greece and Yugoslavia. A high-ranking Luftwaffe officer, Felmy was tried and convicted in the 1948 Hostag ...

. In the Peloponnese, Le Suire carried these orders out with particular ruthlessness, particularly as the partisan threat mounted, resulting in the Kalavryta massacre

The Kalavryta massacre ( el, Σφαγή των Καλαβρύτων), or the Holocaust of Kalavryta (), was the near-extermination of the male population and the total destruction of the town of Kalavryta, Axis-occupied Greece, by the 117th J ...

in December.

In 1943, the German commanders in Greece concluded that their own forces were insufficient to suppress ELAS. As a result, and in order to "spare German blood", the decision was taken to recruit the anti-communist elements of Greek society to fight EAM. Apart from the "

In 1943, the German commanders in Greece concluded that their own forces were insufficient to suppress ELAS. As a result, and in order to "spare German blood", the decision was taken to recruit the anti-communist elements of Greek society to fight EAM. Apart from the "Evzone

The Evzones or Evzonoi ( el, Εύζωνες, Εύζωνοι, ) were several historical elite light infantry and mountain units of the Greek Army. Today, they are the members of the Presidential Guard ( el, Προεδρική Φρουρά , transl ...

Battalions" (Ευζωνικά Τάγματα) established by the collaborationist government of Ioannis Rallis

Ioannis Rallis ( el, Ιωάννης Δ. Ράλλης; 1878 – 26 October 1946) was the third and last collaborationist prime minister of Greece during the Axis occupation of Greece during World War II, holding office from 7 April 1943 to 12 Oct ...

, in late 1943 independent "Security Battalions

The Security Battalions ( el, Τάγματα Ασφαλείας, Tagmata Asfaleias, derisively known as ''Germanotsoliades'' (Γερμανοτσολιάδες) or ''Tagmatasfalites'' (Ταγματασφαλίτες)) were Greek Collaboration with ...

" (Τάγματα Ασφαλείας, ΤΑ) began being raised, particularly in the Peloponnese, where the political affiliations of a large part of the population and the violent dissolution of ES provided a broad recruitment pool of anti-communists. By early 1944, five battalions were formed and placed under the overall command of Papadongonas. One of them was the Kalamata Security Battalion (Τάγμα Ασφαλείας Καλαμών), based at Meligalas, which controlled the road from Kalamata

Kalamáta ( el, Καλαμάτα ) is the second most populous city of the Peloponnese peninsula, after Patras, in southern Greece and the largest city of the homonymous administrative region. As the capital and chief port of the Messenia reg ...

to Tripolis and the entire area of the south. The Security Battalions were subordinated to the Higher SS and Police Leader in Greece, Walter Schimana

Walter Schimana (12 March 1898 – 12 September 1948) was an Austrian functionary in the German SS during the Nazi era. He was SS and Police Leader in the occupied Soviet Union in 1942 and Higher SS and Police Leader in occupied Greece from Oc ...

, but the development of relations of trust between the individual battalion commands and the local German authorities led to them enjoying a relative freedom of movement. The Security Battalions served as garrisons in towns across the Peloponnese, but also increasingly participated in German anti-partisan operations; they chose those that would be executed among prisoners and themselves executed hostages as reprisals for partisan attacks on German targets (as happened after the execution of Major General Franz Krech Major General (''Generalmajor'') Franz Krech (died 27 April 1944) was the German commander of the 41st Fortress Division of the Wehrmacht during the World War II Axis occupation of Greece. He was ambushed and killed by a platoon of the Greek Peopl ...

by ELAS in April 1944), gaining a reputation for lack of discipline and brutality.

After suffering some early blows, ELAS managed to recover its influence, and from 1944 conducted constant sabotage on the supply routes used by the German army. In April 1944, ELAS for the first time attacked a town held by a German garrison at Meligalas, but the assault was beaten back. In the same month, EAM leader

After suffering some early blows, ELAS managed to recover its influence, and from 1944 conducted constant sabotage on the supply routes used by the German army. In April 1944, ELAS for the first time attacked a town held by a German garrison at Meligalas, but the assault was beaten back. In the same month, EAM leader Georgios Siantos

Georgios Siantos (nicknames: ''Geros'' "Old man", ''Theios'' "Uncle"; el, Γεώργιος "Γιώργης" Σιάντος; 1890 – 20 May 1947) was a prominent figure of the Communist Party of Greece ( el, links=no, Κομμουνιστικό � ...

, following reports of indiscipline among the partisan forces in the Peloponnese, sent there Aris Velouchiotis

Athanasios Klaras ( el, Αθανάσιος Κλάρας; August 27, 1905 – June 15, 1945), better known by the ''nom de guerre'' Aris Velouchiotis ( el, Άρης Βελουχιώτης), was a Greek journalist, politician, member of the Commun ...

as representative of the Political Committee of National Liberation

The Political Committee of National Liberation ( el, Πολιτική Επιτροπή Εθνικής Απελευθέρωσης, ''Politiki Epitropi Ethnikis Apeleftherosis'', PEEA), commonly known as the "Mountain Government" ( el, Κυβέρ ...

(PEEA), EAM's newly established parallel government. Velouchiotis' task was to reorganize the 3rd ELAS Division

Third or 3rd may refer to:

Numbers

* 3rd, the ordinal form of the cardinal number 3

* , a fraction of one third

* 1⁄60 of a ''second'', or 1⁄3600 of a ''minute''

Places

* 3rd Street (disambiguation)

* Third Avenue (disambiguation)

* Hig ...

, with a total strength of some 6,000 men. Velouchiotis quickly imposed strict discipline, managing to reverse the decline in partisan numbers and increase the number of their attacks on enemy targets. The deterioration of the military situation led Felmy to declare the Peloponnese as a combat zone in May, which allowed Le Suire to in turn declare martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

, limiting the civilian population's freedom of movement and assembly. Nevertheless, the sweeps and reprisals by the Germans and their collaborators were not enough to reverse ELAS penetration of the countryside in Messenia and neighbouring Laconia

Laconia or Lakonia ( el, Λακωνία, , ) is a historical and administrative region of Greece located on the southeastern part of the Peloponnese peninsula. Its administrative capital is Sparta. The word ''laconic''—to speak in a blunt, c ...

. In the area of Kalamata, where during the occupation thousands of homes were torched and about 1,500 people had been executed, the reprisals of the Security Battalions continued until late summer. In late August, while clashes between the ELAS and the Germans had decreased, those between ELAS and the Security Battalions increased steadily.

Position of the Greek collaborators

In November 1943, the Moscow Conference issued a joint "Statement on Atrocities" by theAllied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

leaders Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

and Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

, concerning the prosecution and trial of those Germans responsible for war crimes against occupied nations. This also served as the basis for the condemnation of Axis collaborators in the occupied countries. In the spirit of this declaration, the Greek government in exile

The Greek government-in-exile was formed in 1941, in the aftermath of the Battle of Greece and the subsequent occupation of Greece by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. The government-in-exile was based in Cairo, Egypt, and hence it is also referr ...

announced the revocation of Greek nationality from the members of the collaborationist governments, while PEEA issued a legal act proscribing the death penalty

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

for high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

to those who collaborated with the occupation authorities, including the members of the Security Battalions. However, the burgeoning confrontation between EAM and the government in exile and its British backers, who at least since 1943 began to view EAM as an obstacle to their own plans for Britain's post-war role in Greece, led the British to consider the possibility of using the Security Battalions as part of the planned post-war national Greek army, or at least as a means of applying pressure and getting EAM to agree to support a national unity government

A national unity government, government of national unity (GNU), or national union government is a broad coalition government consisting of all parties (or all major parties) in the legislature, usually formed during a time of war or other nati ...

. Thus, during negotiations on forming a new government, Georgios Papandreou

Georgios Papandreou ( ''Geórgios Papandréou''; 13 February 1888 – 1 November 1968) was a Greek politician, the founder of the Papandreou political dynasty. He served three terms as prime minister of Greece (1944–1945, 1963, 1964–196 ...

, head of the government in exile, resisted the pressure of the PEEA delegates to publicly condemn the Security Battalions, arguing that this had already been done in the Lebanon Conference

The Lebanon conference ( el, Συνέδριο του Λιβάνου) was held on May 17–20, 1944, between representatives of the Greek government in exile, the pre-war Greek political parties, and the major Greek Resistance organizations, with ...

in May 1944, and in June he caused the Allied propaganda against the Security Battalions, both through the dropping of leaflets and through radio emissions, to be suspended.

With the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

advancing in the Eastern Front and the invasion of Romania, on 23 August 1944 the German command decided to withdraw the 117th Division from the Peloponnese. Three days later the complete evacuation of German forces from mainland Greece was decided. The British desired the maintenance of the status quo until the arrival of their forces and the Papandreou government, and above all wanted to avoid German arms and equipment from falling into the hands of the partisans. On the other hand, EAM/ELAS and its supporters were eager for revenge on the remnants of the collaborationist Gendarmerie and the Security Battalions. After the German troops withdrew from the Peloponnese, the position of their former allies became highly precarious, and fears of ELAS reprisals spread. On 3 September, the military head of ELAS, Stefanos Sarafis

Stefanos Sarafis ( el, Στέφανος Σαράφης, 23 October 1890 – 31 May 1957) was an officer of the Hellenic Army and Major General in EAM-ELAS), who played an important role during the Greek Resistance.

Early life and career

Saraf ...

, issued a proclamation calling upon the members of the Security Battalions to surrender with their weapons, in order to safeguard their lives. On the same day the British lieutenant general Ronald Scobie

Lieutenant-General Sir Ronald MacKenzie Scobie, (8 June 1893 – 23 February 1969) was a senior British Army officer who fought in both the First and Second World Wars, where he commanded the 70th Infantry Division and later III Corps. He was ...

, appointed joint commander-in-chief of all Greek forces, issued an order to his deputy in Athens, the Greek lieutenant general Panagiotis Spiliotopoulos, to recommend to the Security Battalions personnel to either desert or to surrender themselves to him, with the promise that they would be treated as regular prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held Captivity, captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold priso ...

. This order, however, either did not apply to the Security Battalions in the Peloponnese or was in the event ignored by them. As EAM had joined the Papandreou government on 15 August, on 6 September a formal declaration of the new national unity government was issued, in which the members of the Security Battalions were designated as criminals against the fatherland, and called upon to "immediately abandon" their positions and join the Allies. At the same time, the declaration called on the Resistance forces to stop any acts of reprisal, insisting that dispensing justice was a right reserved by the state and not of "organizations and individuals", while promising that "the national nemesis will be implacable".

German withdrawal and aftermath

During the last months of the German occupation, Walter Blume, the head of the German security police ( SD) developed the so-called "chaos thesis", involving not only a thorough

During the last months of the German occupation, Walter Blume, the head of the German security police ( SD) developed the so-called "chaos thesis", involving not only a thorough scorched earth

A scorched-earth policy is a military strategy that aims to destroy anything that might be useful to the enemy. Any assets that could be used by the enemy may be targeted, which usually includes obvious weapons, transport vehicles, communi ...

policy, but also encouraging the slide of Greece into civil war and chaos. While Blume's more radical proposals concerning the elimination of the (mostly anti-communist and pro-British) pre-war political leadership were halted by more sober elements in the German leadership, as they withdrew from the Peloponnese in early September, the Germans destroyed bridges and railway lines and left weapons and ammunition to the Security Battalions, laying the groundwork for a civil war with ELAS.

Based on the denunciation of the Security Battalions by the national unity government, ELAS considered the Security Battalions as enemy formations. At Pyrgos, the capital of Elis Prefecture

Elis or Ilia ( el, Ηλεία, ''Ileia'') is a historic region in the western part of the Peloponnese peninsula of Greece. It is administered as a regional unit of the modern region of Western Greece. Its capital is Pyrgos. Until 2011 it was ...

, the commander of the local battalion, Georgios Kokkonis, announced that he placed his unit under the command of the exiled king George II George II or 2 may refer to:

People

* George II of Antioch (seventh century AD)

* George II of Armenia (late ninth century)

* George II of Abkhazia (916–960)

* Patriarch George II of Alexandria (1021–1051)

* George II of Georgia (1072–1089)

* ...

and the national government. Kokkonis conducted negotiations with ELAS, trying to prevent its entry into the city before the arrival of an official government representative, while ELAS demanded the immediate disarmament of the unit. In the end, ELAS attacked on 9 September and after a bloody struggle seized the city on the next day. At Tripolis, the negotiations between Colonel Papadongonas and 3rd ELAS Division quickly broke down. As the partisans surrounded the city, mining the roads and cutting off its water supply, and their own ammunition began to run out, the Battalionists descended into panic. Some defected, but the remainder installed a regime of terror in the city: anyone even suspected of ties to the partisans was imprisoned and Papadongonas threatened to blow them up if ELAS attacked, while his men mined the city and executed people on the streets. Nevertheless, Papadongonas was able to hold out until the end of September, when he surrendered to a British unit.

Events in Messenia

At Kalamata, the Germans departed on 5 September, leaving the Gendarmerie as the sole official armed force in the city. Using representatives of the Allied Middle East Headquarters as intermediaries, ELAS approached the prefect of Messenia, Dimitrios Perrotis, proposing the disarmament of the local Security Battalions and their confinement as prisoners until the arrival of the exiled national government. After the proposal was rejected, ELAS attacked the city at dawn of 9 September. As the partisans overcame the Battalionists' resistance, large numbers of local civilians began arriving in the city to take revenge on them. About 100–120 Battalionists, under the command of 2nd Lieutenant Nikos Theofanous and Perrotis, managed to escape the city via the unguarded railway line and sought refuge at Meligalas. A strong force of Security Battalion men was already ensconced there, and was further reinforced by another 100–120 men who arrived fromKopanaki

Kopanaki ( el, Κοπανάκι) is a town in northwestern Messenia, Peloponnese, Greece. It was the seat of the former municipality of Aetos and now it belongs to the municipality of Trifylia. Agriculture, specifically olive farming, is the ma ...

on 11 September.

Consequently, the capture of Meligalas assumed a major importance for ELAS in its bid to secure its control over the Peloponnese. The archimandrite

The title archimandrite ( gr, ἀρχιμανδρίτης, archimandritēs), used in Eastern Christianity, originally referred to a superior abbot (''hegumenos'', gr, ἡγούμενος, present participle of the verb meaning "to lead") who ...

along with two British officers, went to the town to deliver a proposal for the disarmament of the Battalionists and their transfer to a secure prisoner camp until the arrival of the government, in order to secure life and property for themselves and their families, but Perrotis rejected it. Pleas by relatives of the Battalionists who arrived from nearby villages had a similar fate.

Battle of Meligalas

The Battalionists installed a heavy machine gun in the clock tower of the main church in Meligalas, Agios Ilias, and distributed the light machine guns they possessed in houses around the church and in semi-circular ramparts around the paddock of Meligalas. ELAS forces, numbering men from the 8th and 9th Regiments, launched their attack on the morning of 13 September. The attack followed a plan laid down with the participation of (''nom de guerre

A pseudonym (; ) or alias () is a fictitious name that a person or group assumes for a particular purpose, which differs from their original or true name (orthonym). This also differs from a new name that entirely or legally replaces an individua ...

'' "Orion") from the staff of the 9th ELAS Brigade: 2/9 Battalion assumed the sector between the Meligalas– Anthousa and Meligalas–Neochori roads, 1/9 Battalion assumed the sector northeast of Profitis Ilias height, 3/9 Battalion the northern sector up to the road towards Meropi

Meropi ( el, Μερόπη) is a village and a community in the municipality of Oichalia, in Messenia, Greece. It is located in the plains of northern Messenia, west of the Taygetus mountains. It is near a major highway linking Kalamata and Corinth ...

, and 1/8 Battalion the eastern plain until the road to Skala

Skala may refer to:

Places Greece

* Skala, Patmos, the main port on the island of Patmos in Greece

* Skala, Laconia, a municipality in southern Greece

* Skala, Xanthi, a settlement in north-eastern Greece

* Skala, Cephalonia, a resort in the ...

. At the Skala heights, ELAS also positioned its sole 10.5 cm gun (lacking a gun carriage

A gun carriage is a frame and mount that supports the gun barrel of an artillery piece, allowing it to be maneuvered and fired. These platforms often had wheels so that the artillery pieces could be moved more easily. Gun carriages are also used ...

), commanded by the artillery captain Kostas Kalogeropoulos. The ELAS plan aimed at the rapid advance of 2/9 Battalion, under Captain Tasos Anastasopoulos ("Kolopilalas") from the edge of the settlement to the main square, so that the Agios Ilias fort could be attacked on two sides.

The attackers, however, encountered a minefield of improvised mines (boxes with dynamite) planted by the Battalionists the previous afternoon and evening, during the negotiations with ELAS. A new plan was made, aiming at the storming of Agios Ilias by a company of 2/9 Battalion under . This new assault forced the Battalionists to dismount the heavy machine gun from the clock tower, while the attack of 1/8 Battalion forced the garrison of the railway station to retreat to the bedesten

A bedesten (variants: bezistan, bezisten, bedestan) is a type of covered market or market hall which was historically found in the cities of the Ottoman Empire. It was typically the central building of the commercial district of an Ottoman town or ...

, where a number of EAM sympathizers were being held hostage. From the afternoon to nightfall, the lines of the combatants remained the same, but the losses suffered by the Battalionists led to a fall in their morale and unwillingness to continue the battle. Their commander, Major Dionysios Papadopulos, sent a delegation to request aid from Panagiotis Stoupas

Panagiotis or Panayiotis ( el, Παναγιώτης, ), "Παν" (all) "άγιος" (holy or saint) suffix "-της" (which can mean "of the"), is a common male Greek name. It derives from the Greek epithet Panagia or ''Panayia'' ("All-Holy") for ...

in nearby Gargalianoi

Gargalianoi ( el, Γαργαλιάνοι) is a town and a former municipality in Messenia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Trifylia, of which it is a municipal unit. The municipal unit has ...

, but the delegates abandoned their mission as soon as they left Meligalas.

At noon of 14 September, a group of 30 partisans attacked by throwing German Teller mine

The Teller mine (german: Tellermine) was a German-made antitank mine common in World War II. With explosives sealed inside a sheet metal casing and fitted with a pressure-actuated fuze, Teller mines had a built-in carrying handle on the side. As t ...

s on the barbed wire protecting Agios Ilias, but was repulsed amidst a hail of fire by the Battalionists. A squad under Basakidis managed to breach the barricades of the defenders, but left without support, they were thrown back in a counterattack led by the sergeant major Panagiotis Benos. The sight of wounded ELAS fighters, and news of a murder committed by Battalionists, heightened the hostile mood among the civilians observing the battle.

On the morning of 15 September, the leaders of the Security Battalions met in council. Major Papadopoulos proposed attempting a breakthrough in the direction of Gargalianoi, but the council was abruptly interrupted when the house was hit by a mortar bomb. In addition, rumours of the breakthrough plan were spread by Perrotis' men, panicking the wounded Battalionists, but also the imprisoned EAM sympathizers. The council was terminated following a new ELAS attack on Agios Ilias, during which Basakidis' men, using hand grenades and submachine guns, managed to push the Battalionists back. From their new positions, four ELAS partisans began firing with their light machine guns into the interior of the town, while on the sector of 1/8 Battalion, Battalionists began raising white flags in surrender. A few dozen Battalionists under Major Kazakos tried to escape to the south and thence to Derveni, but suffered heavy casualties from the Reserve ELAS, the ' (Velouchiotis' personal guard), and a squad of 11th ELAS Regiment at the heights near Anthousa.

Reprisals and executions

The end of the battle was followed by the invasion of Meligalas by civilians, and an unchecked plunder and massacre. According to a contemporary report preserved in the archives of the Communist Party of Greece (KKE), these were inhabitants of the village of Skala, which had been torched by the German army. Among the captive Battalionists held in the bedesten, Velouchiotis—who arrived at Meligalas shortly after the end of the battle with his personal escort—recognized a gendarme whom he had previously arrested and then released, and ordered his execution. The first reprisal wave, tacitly encouraged by ELAS through the deliberately loose guarding of its captives, was followed by a series of organized executions.

A partisan court martial was set up in the town, headed by the lawyers

The end of the battle was followed by the invasion of Meligalas by civilians, and an unchecked plunder and massacre. According to a contemporary report preserved in the archives of the Communist Party of Greece (KKE), these were inhabitants of the village of Skala, which had been torched by the German army. Among the captive Battalionists held in the bedesten, Velouchiotis—who arrived at Meligalas shortly after the end of the battle with his personal escort—recognized a gendarme whom he had previously arrested and then released, and ordered his execution. The first reprisal wave, tacitly encouraged by ELAS through the deliberately loose guarding of its captives, was followed by a series of organized executions.

A partisan court martial was set up in the town, headed by the lawyers Vasilis Bravos Vassilios or Vassileios, also transliterated Vasileios, Vasilios, Vassilis or Vasilis ( el, Βασίλειος or Βασίλης), is a Greek given name, the origin of Basil. In ancient/medieval/Byzantine context, it is also transliterated as Basile ...

and . This court summarily condemned not only the officers and other leaders of the Battalions—lists with their names had been provided by local EAM cells—but also many others, including for reasons having more to do with personal differences rather than any crime committed. The executions took place at an abandoned well ("πηγάδα") outside the town. According to usual practice, to avoid the executioners being recognized, the executions were carried out by an ELAS detachment from a different area, most likely a squad of 8th Regiment, whose men were from the area of Kosmas

Cosmas or Kosmas is a Greek name ( grc-gre, Κοσμᾶς), from Ancient Greek Κοσμᾶς (Kosmâs), associated with the noun κόσμος (kósmos), meaning "universe", and the verb κοσμέω (to order, govern, adorn) linked to propriet ...

and Tsitalia in Arcadia

Arcadia may refer to:

Places Australia

* Arcadia, New South Wales, a suburb of Sydney

* Arcadia, Queensland

* Arcadia, Victoria

Greece

* Arcadia (region), a region in the central Peloponnese

* Arcadia (regional unit), a modern administrative un ...

.

On 17 September, Velouchiotis moved to Kalamata, where Perrotis and other collaborationist officials were also brought. At the central square of the city, the enraged crowd broke the ranks of the ELAS militia and lynched some of the prisoners, while twelve of them were hanged from lampposts.

Casualty estimates

In an ELAS communique of 26 September 1944, Major General

In an ELAS communique of 26 September 1944, Major General Emmanouil Mantakas

Emmanouil or Manolis Mantakas ( el, Μανώλης Μάντακας, Lakkoi, 1891 - Athens, 1968) was a Greek Army officer who rose to the rank of Major General, and who became a leader in the Greek Resistance and a politician.

Biography

He ...

reported that "800 ''Rallides'' [the derogatory nickname for the Battalionists, after the collaborationist PM Ioannis Rallis

Ioannis Rallis ( el, Ιωάννης Δ. Ράλλης; 1878 – 26 October 1946) was the third and last collaborationist prime minister of Greece during the Axis occupation of Greece during World War II, holding office from 7 April 1943 to 12 Oct ...

] were killed", a number repeated by Stefanos Sarafis in his own book on ELAS. A Red Cross report, which generally tried to be as objective as possible, stated that the number of dead "exceeded 1,000", while a year later, the team of the noted Greek coroner reported that it recovered 708 corpses from Meligalas.

The post-war right-wing establishment insisted on a considerably higher tally, with estimates ranging from 1,110 to over 2,500 victims. Thus the National Radical Union

The National Radical Union ( el, Ἐθνικὴ Ῥιζοσπαστικὴ Ἕνωσις (ΕΡΕ), ''Ethnikī́ Rizospastikī́ Énōsis'' (ERE)) was a Greek political party formed in 1956 by Konstantinos Karamanlis, mostly out of the Greek Rall ...

politician Kosmas Antonopoulos, whose father had been executed by ELAS, wrote about 2,100 executed people at Meligalas, although he cites data for 699 people. In contrast, authors sympathetic to EAM reduce the number of executions considerably: the most detailed account calculates 120 killed in action and 280–350 executed. Ilias Theodoropoulos, whose brother was killed in Meligalas, in his book (distributed by the "Society of Victims of the Meligalas Well") mentions from 1,500 to over 2,000 dead, and provides a list with 1,144 names (of whom 108 from Meligalas) of those killed in action and those executed by ELAS (including some of those lynched in Kalamata, such as Perrotis). Among the victims are 18 elderly, 22 women and 9 adolescents (8 boys and a girl), while all the rest—with some exceptions where age is not mentioned—are men of fighting age.

Aftermath

The events at Meligalas and Kalamata were detrimental to EAM, whose leadership initially denied that any massacre had taken place, only to be forced to acknowledge it later and issue a condemnation. The more moderate leaders of EAM,Alexandros Svolos

Alexandros Svolos ( el, Αλέξανδρος Σβώλος; 1892, Kruševo, Manastir Vilayet, Ottoman Empire – 22 February 1956, Athens, Greece) was a prominent Greek legal expert, who also served as president of the Political Committee of Natio ...

and Sarafis, insisted that they faithfully carried out the orders of the national unity government, and issued orders to "stop all executions".

These events demonstrated the willingness of ELAS to suffer significant losses in order to gain control before the arrival of British forces, and its ability to succeed in this goal led to a shift in British policy: the British liaison officers in the Peloponnese, who until then were under orders not to get involved in events, were now directed to intervene to secure the surrender, safekeeping, and delivery of the Security Battalions' weapons to British forces, to avoid them falling in the hands of ELAS. As a result, due to the mediation of British liaisons, the Red Cross, representatives of the Papandreou government, or even the local EAM authorities, in many towns of Central Greece and the Peloponnese the Security Battalions surrendered without resistance or bloodshed. There were nevertheless several cases where Battalionists, having surrendered, were killed, either by ELAS partisans, or by civilian mobs and relatives of Battalionist victims, as at Pylos or in some places in northern Greece. This was mainly the result of the widespread desire for vengeance among the population, but some cases involved the co-operation or even instigation of EAM cadres. The social polarization between EAM and its opponents, both Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

and nationalist anti-communists, resulted in the adoption of a sort of double speak

Doublespeak is language that deliberately obscures, disguises, distorts, or reverses the meaning of words. Doublespeak may take the form of euphemisms (e.g., "downsizing" for layoffs and "servicing the target" for bombing), in which case it ...

. EAM proclaimed that it supported order and the restoration of government authority, while at the same time launching a large-scale bloody extrajudicial purge, in order to secure its political domination before the arrival of the British forces, improve its negotiating position within the government, and satisfy the popular demand for revenge, so as to then demonstrate self-restraint and respect before the law. EAM's rivals on the other hand guaranteed its participation in the government while simultaneously trying to preserve the lives of the collaborationists.

In general, however, in the power vacuum in the wake of the German withdrawal, the EAM/ELAS officials who assumed control tried to impose order, preventing rioting and looting, and resisting calls for revenge by the populace. According to Mark Mazower

Mark Mazower (; born 20 February 1958) is a British historian. His expertise are Greece, the Balkans and, more generally, 20th-century Europe. He is Ira D. Wallach Professor of History at Columbia University in New York City

Early life

Mazowe ...

, "ELAS rule was as orderly as was to be expected in the extraordinary circumstances that prevailed. Passions ran high, and intense suspicions were mingled with euphoria". Furthermore, EAM/ELAS was not a monolithic or tightly controlled organization, and its representatives displayed a variety of behaviour; as British observers noted, in some areas ELAS maintained order "fairly and impartially", while abusing their power in others. When British forces landed in the Peloponnese, they found the National Civil Guard

The National Civil Guard ( el, Εθνική Πολιτοφυλακή, ''Ethniki Politophylaki'') was the security force of the Political Committee of National Liberation (PEEA), the government that the National Liberation Front (EAM) had establish ...

, created by EAM in late summer to assume policing duties from the partisans and replace the discredited collaborationist Gendarmerie, maintained control and order. In Patras

)

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 =

, demographics1_info2 =

, timezone1 = EET

, utc_offset1 = +2

, ...

, for example, joint patrols of British soldiers and Civil Guard men were carried out until November 1944. Reprisals were also a common phenomenon in other European countries that suffered under Nazi occupation, from the mass expulsion of the Germans in eastern Europe to mass executions of collaborationists: over 10,000 in France, and between 12,000 and 20,000 in Italy.

On 26 September 1944, the Caserta Agreement

The Caserta Agreement was signed on 26 September 1944, between the Greek exiled government (under Georgios Papandreou), the British Command in the Middle East, National Liberation Front (Greece), EAM/Greek People's Liberation Army, ELAS and EDES i ...

was signed by Papandreou, EDES

The National Republican Greek League ( el, Εθνικός Δημοκρατικός Ελληνικός Σύνδεσμος (ΕΔΕΣ), ''Ethnikós Dimokratikós Ellinikós Sýndesmos'' (EDES)) was one of the major resistance groups formed during t ...

leader Napoleon Zervas

Napoleon Zervas ( el, Ναπολέων Ζέρβας; May 17, 1891 – December 10, 1957) was a Hellenic Army officer and resistance leader during World War II. He organized and led the National Republican Greek League (EDES), the second most signi ...

, Sarafis on behalf of ELAS, and Scobie. The agreement placed ELAS and EDES under Scobie's overall command, and designated the Security Battalions as "instruments of the enemy", ordering that they were to be treated as hostile forces if they did not surrender. After the agreement was signed, Scobie ordered his officers to intervene in order to protect the Battalionists, disarming them and confining them under guard.

Following the Liberation of Greece in October 1944, in some occasions the families of Meligalas victims received pensions based on the collaborationist government's law 927/1943 on military and civil officials murdered "by anarchist elements" during the execution of their duties, a law which was retained by the post-war governments.

Commemoration

Since September 1945, an annual memorial service for the victims has taken place. It is organized by the local authorities and has official representation, including government members during theGreek military junta

The Greek junta or Regime of the Colonels, . Also known within Greece as just the Junta ( el, η Χούντα, i Choúnta, links=no, ), the Dictatorship ( el, η Δικτατορία, i Diktatoría, links=no, ) or the Seven Years ( el, η Ε ...

.

The Meligalas events were utilized politically and ideologically. The right-wing establishment after the Greek Civil War

The Greek Civil War ( el, ο Eμφύλιος �όλεμος ''o Emfýlios'' 'Pólemos'' "the Civil War") took place from 1946 to 1949. It was mainly fought against the established Kingdom of Greece, which was supported by the United Kingdom ...

represented Meligalas as a symbol of "communist barbarity", while the Battalionists were commemorated exclusively as opponents or victims of the communists, since the post-war Greek state drew its legitimacy not from the collaborationist government, but from the government in exile. In newspaper announcements for the annual service and the speeches held there, every mention of the victims' membership in the Security Battalions was omitted; instead, they were referred to as "murdered ''ethnikofrones'' ational-minded persons or "patriots".

In 1982, following the electoral victory of the socialist PASOK

The Panhellenic Socialist Movement ( el, Πανελλήνιο Σοσιαλιστικό Κίνημα, Panellínio Sosialistikó Kínima, ), known mostly by its acronym PASOK, (; , ) is a social-democratic political party in Greece. Until 2012, it ...

the previous year, the Ministry of the Interior

An interior ministry (sometimes called a ministry of internal affairs or ministry of home affairs) is a government department that is responsible for internal affairs.

Lists of current ministries of internal affairs

Named "ministry"

* Ministry ...

declared that these commemorations were promoting intolerance and for 40 years had been promoting division, and decided the cessation of official authorities' attendance at the memorial service. Its organization henceforth was undertaken by the "Society of Victims of the Meligalas Well" (Σύλλογος Θυμάτων Πηγάδας Μελιγαλά), established in 1980. The relative marginalization of the memorial service was accompanied by the transformation of the speeches from celebratory to apologetic for the victims' role in the Security Battalions. In recent times, the service is attended by relatives of the victims and by far-right or even neo-Nazi

Neo-Nazism comprises the post–World War II militant, social, and political movements that seek to revive and reinstate Nazism, Nazi ideology. Neo-Nazis employ their ideology to promote hatred and Supremacism#Racial, racial supremacy (ofte ...

groupings such as Golden Dawn.

In the early 1980s, the Meligalas events became a point of reference in confrontations between university students close to the and the Leftist Clusters on the one side and the right-wing ONNED youth organization and its student wing, DAP-NDFK. After the PASOK government officially recognized EAM's contribution in the Greek Resistance in 1982, "Rigas Feraios" members coined the slogan "EAM-ELAS-Meligalas" ("ΕΑΜ-ΕΛΑΣ-Μελιγαλάς") as a counter to the positive portrayal of the Battalionists by the right-wing groups. The slogan remained current in the university students' conference of 1992, following Civil War-era and anti-communist slogans used by DAP. In the late 2000s, when the political slogans and rhetoric of the 1940s increasingly resurfaced in Greek political discourse, and with Golden Dawn's entry into the

In the early 1980s, the Meligalas events became a point of reference in confrontations between university students close to the and the Leftist Clusters on the one side and the right-wing ONNED youth organization and its student wing, DAP-NDFK. After the PASOK government officially recognized EAM's contribution in the Greek Resistance in 1982, "Rigas Feraios" members coined the slogan "EAM-ELAS-Meligalas" ("ΕΑΜ-ΕΛΑΣ-Μελιγαλάς") as a counter to the positive portrayal of the Battalionists by the right-wing groups. The slogan remained current in the university students' conference of 1992, following Civil War-era and anti-communist slogans used by DAP. In the late 2000s, when the political slogans and rhetoric of the 1940s increasingly resurfaced in Greek political discourse, and with Golden Dawn's entry into the Greek Parliament

The Hellenic Parliament ( el, Ελληνικό Κοινοβούλιο, Elliniko Kinovoulio; formally titled el, Βουλή των Ελλήνων, Voulí ton Ellínon, Boule of the Hellenes, label=none), also known as the Parliament of the Hel ...

in 2012

File:2012 Events Collage V3.png, From left, clockwise: The passenger cruise ship Costa Concordia lies capsized after the Costa Concordia disaster; Damage to Casino Pier in Seaside Heights, New Jersey as a result of Hurricane Sandy; People gather ...

, the Meligalas events were re-evaluated in a positive light by the Greek left as an example of militant anti-fascist action. Reference to them is now commonly combined with typically anti-authoritarian

Anti-authoritarianism is opposition to authoritarianism, which is defined as "a form of social organisation characterised by submission to authority", "favoring complete obedience or subjection to authority as opposed to individual freedom" and ...

slogans.

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Meligalas Battle 1944 in Greece Conflicts in 1944 Battles and operations involving the Greek People's Liberation Army History of Messenia Massacres in Greece during World War II September 1944 events War crimes in Greece Politicides World War II prisoner of war massacres Peloponnese in World War II Mass murder in 1944