Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th

president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal gove ...

from 2009 to 2017. A member of the

Democratic Party, Obama was the first African-American president of the United States.

He previously served as a

U.S. senator

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and power ...

from

Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rock ...

from 2005 to 2008 and as an

Illinois state senator

The Illinois Senate is the upper chamber of the Illinois General Assembly, the legislative branch of the government of the State of Illinois in the United States. The body was created by the first state constitution adopted in 1818. Under the I ...

from 1997 to 2004, and previously worked as a civil rights lawyer before entering politics.

Obama was born in

Honolulu

Honolulu (; ) is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, which is in the Pacific Ocean. It is an unincorporated county seat of the consolidated City and County of Honolulu, situated along the southeast coast of the isla ...

, Hawaii. After graduating from

Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

in 1983, he worked as a

community organizer

Community organizing is a process where people who live in proximity to each other or share some common problem come together into an organization that acts in their shared self-interest.

Unlike those who promote more-consensual community bui ...

in Chicago. In 1988, he enrolled in

Harvard Law School

Harvard Law School (Harvard Law or HLS) is the law school of Harvard University, a private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1817, it is the oldest continuously operating law school in the United States.

Each c ...

, where he was the first black president of the ''

Harvard Law Review

The ''Harvard Law Review'' is a law review published by an independent student group at Harvard Law School. According to the ''Journal Citation Reports'', the ''Harvard Law Review''s 2015 impact factor of 4.979 placed the journal first out of 143 ...

''. After graduating, he became a civil rights attorney and an academic, teaching constitutional law at the

University of Chicago Law School

The University of Chicago Law School is the law school of the University of Chicago, a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. It is consistently ranked among the best and most prestigious law schools in the world, and has many dis ...

from 1992 to 2004. Turning to elective politics, he

represented the 13th district in the

Illinois Senate

The Illinois Senate is the upper chamber of the Illinois General Assembly, the legislative branch of the government of the State of Illinois in the United States. The body was created by the first state constitution adopted in 1818. Under the ...

from 1997 until 2004, when he

ran for the U.S. Senate. Obama received national attention in 2004 with his March Senate primary win, his well-received July

Democratic National Convention

The Democratic National Convention (DNC) is a series of presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1832 by the United States Democratic Party. They have been administered by the Democratic National Committee since the 18 ...

keynote address

A keynote in public speaking is a talk that establishes a main underlying theme. In corporate or commercial settings, greater importance is attached to the delivery of a keynote speech or keynote address. The keynote establishes the framework f ...

, and his landslide November election to the Senate. In 2008, after

a close primary campaign against

Hillary Clinton

Hillary Diane Rodham Clinton ( Rodham; born October 26, 1947) is an American politician, diplomat, and former lawyer who served as the 67th United States Secretary of State for President Barack Obama from 2009 to 2013, as a United States sen ...

, he was nominated by the Democratic Party for president and chose

Joe Biden as his running mate. Obama was elected over

Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

nominee

John McCain

John Sidney McCain III (August 29, 1936 – August 25, 2018) was an American politician and United States Navy officer who served as a United States senator from Arizona from 1987 until his death in 2018. He previously served two te ...

in the

presidential election

A presidential election is the election of any head of state whose official title is President.

Elections by country

Albania

The president of Albania is elected by the Assembly of Albania who are elected by the Albanian public.

Chile

The p ...

and was

inaugurated

In government and politics, inauguration is the process of swearing a person into office and thus making that person the incumbent. Such an inauguration commonly occurs through a formal ceremony or special event, which may also include an inaugur ...

on January 20, 2009. Nine months later, he was named the

2009 Nobel Peace Prize laureate, a decision that drew a mixture of praise and criticism.

Obama's first-term actions addressed the

global financial crisis

Global means of or referring to a globe and may also refer to:

Entertainment

* ''Global'' (Paul van Dyk album), 2003

* ''Global'' (Bunji Garlin album), 2007

* ''Global'' (Humanoid album), 1989

* ''Global'' (Todd Rundgren album), 2015

* Bruno ...

and included a

major stimulus package, a partial extension of

George W. Bush's

tax cuts

A tax cut represents a decrease in the amount of money taken from taxpayers to go towards government revenue. Tax cuts decrease the revenue of the government and increase the disposable income of taxpayers. Tax cuts usually refer to reductions in ...

, legislation to

reform health care, a major

financial regulation reform bill, and the end of a major US

military presence in

Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

. Obama also appointed

Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

Justices

Sonia Sotomayor

Sonia Maria Sotomayor (, ; born June 25, 1954) is an American lawyer and jurist who serves as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. She was nominated by President Barack Obama on May 26, 2009, and has served since ...

and

Elena Kagan

Elena Kagan ( ; born April 28, 1960) is an American lawyer who serves as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. She was Elena Kagan Supreme Court nomination ...

, the former being the first

Hispanic American

Hispanic and Latino Americans ( es, Estadounidenses hispanos y latinos; pt, Estadunidenses hispânicos e latinos) are Americans of Spanish and/or Latin American ancestry. More broadly, these demographics include all Americans who identify a ...

on the Supreme Court. He ordered

the counterterrorism raid which killed

Osama bin Laden

Osama bin Mohammed bin Awad bin Laden (10 March 1957 – 2 May 2011) was a Saudi-born extremist militant who founded al-Qaeda and served as its leader from 1988 until his death in 2011. Ideologically a pan-Islamist, his group is designated ...

and downplayed Bush's counterinsurgency model, expanding air strikes and making extensive use of special forces while encouraging greater reliance on host-government militaries.

After winning

re-election

The incumbent is the current holder of an office or position, usually in relation to an election. In an election for president, the incumbent is the person holding or acting in the office of president before the election, whether seeking re-ele ...

by defeating Republican opponent

Mitt Romney

Willard Mitt Romney (born March 12, 1947) is an American politician, businessman, and lawyer serving as the junior United States senator from Utah since January 2019, succeeding Orrin Hatch. He served as the 70th governor of Massachusetts ...

, Obama was

sworn in for a second term on January 20, 2013. In his second term, Obama took steps to

combat climate change, signing a major

international climate agreement and an

executive order

In the United States, an executive order is a directive by the president of the United States that manages operations of the federal government. The legal or constitutional basis for executive orders has multiple sources. Article Two of t ...

to limit

carbon emission

Greenhouse gas emissions from human activities strengthen the greenhouse effect, contributing to climate change. Most is carbon dioxide from burning fossil fuels: coal, oil, and natural gas. The largest emitters include coal in China and larg ...

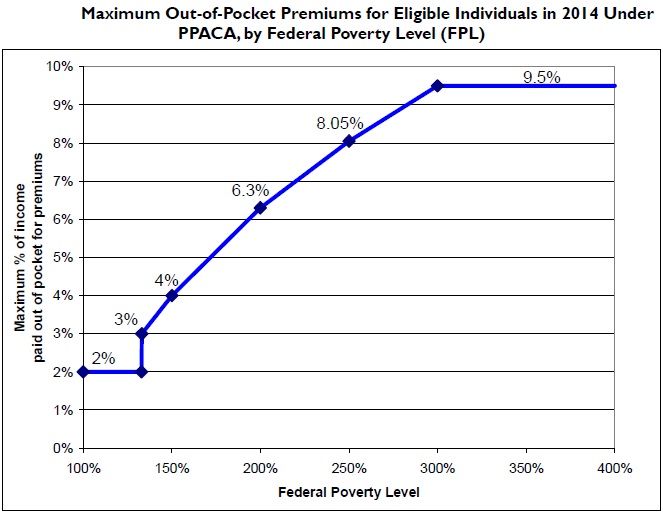

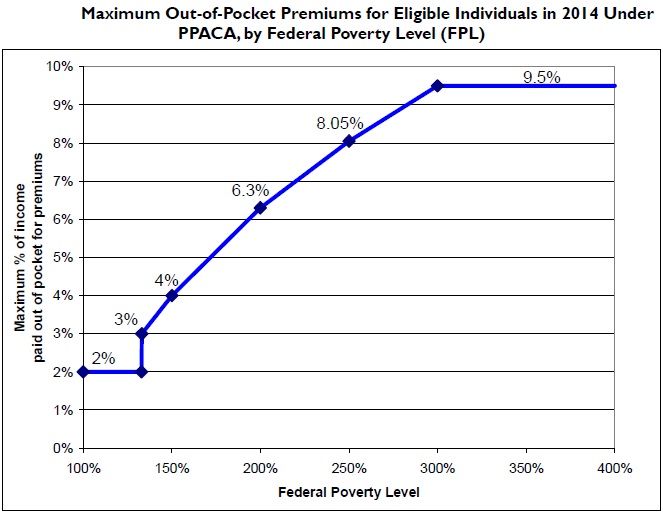

s. Obama also presided over the implementation of the

Affordable Care Act

The Affordable Care Act (ACA), formally known as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and colloquially known as Obamacare, is a landmark U.S. federal statute enacted by the 111th United States Congress and signed into law by Pres ...

and other legislation passed in his first term, and he negotiated a

nuclear agreement with Iran and

normalized relations with Cuba. The number of

American soldiers in

Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is borde ...

fell dramatically during Obama's second term, though U.S. soldiers remained in Afghanistan throughout

Obama's presidency

Barack Obama's tenure as the 44th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 2009, and ended on January 20, 2017. A Democrat from Illinois, Obama took office following a decisive victory over Republic ...

. Obama left office on January 20, 2017, and continues to reside in

Washington, D.C. His

presidential library

A presidential library, presidential center, or presidential museum is a facility either created in honor of a former president and containing their papers, or affiliated with a country's presidency.

In the United States

* The presidential libr ...

in Chicago began construction in 2021.

During Obama's terms as president, the United States'

reputation abroad and the American

economy

An economy is an area of the production, distribution and trade, as well as consumption of goods and services. In general, it is defined as a social domain that emphasize the practices, discourses, and material expressions associated with th ...

improved significantly, although the country experienced high levels of partisan divide. As the first person of color elected president, Obama faced

racist sentiments and was the target of

numerous conspiracy theories. Since leaving office, Obama has remained active in Democratic politics, including campaigning for candidates in various American elections. Outside of politics, Obama has published three

bestselling books

This page provides lists of best-selling individual books and book series to date and in any language. ''"Best-selling"'' refers to the estimated number of copies sold of each book, rather than the number of books printed or currently owned. Com ...

: ''

Dreams from My Father'' (1995)'',

The Audacity of Hope'' (2006) and ''

A Promised Land'' (2020).

Rankings by scholars and historians, in which he has been featured since 2010, view his presidency favorably and place him among the upper tier of American presidents.

Early life and career

Obama was born on August 4, 1961,

at

Kapiolani Medical Center for Women and Children

Kapiolani Medical Center for Women and Children is part of Hawaii Pacific Health's network of hospitals. It is located in Honolulu, Hawaii, within the residential inner-city district of Makiki. Kapiolani Medical Center is Hawaii's only children ...

in

Honolulu

Honolulu (; ) is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, which is in the Pacific Ocean. It is an unincorporated county seat of the consolidated City and County of Honolulu, situated along the southeast coast of the isla ...

,

Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only stat ...

.

He is the only president born outside the

contiguous 48 states.

He was born to an American mother and a Kenyan father. His mother,

Ann Dunham

Stanley Ann Dunham (November 29, 1942 – November 7, 1995) was an American anthropologist who specialized in the economic anthropology and rural development of Indonesia. She is the mother of Barack Obama, the 44th president of the Uni ...

(1942–1995), was born in

Wichita, Kansas

Wichita ( ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Kansas and the county seat of Sedgwick County. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 397,532. The Wichita metro area had a population of 647,610 in 2020. It is located in ...

and was mostly of English descent, though in 2007 it was discovered her great-great-grandfather Falmouth Kearney emigrated from the village of

Moneygall, Ireland to the US in 1850. In July 2012,

Ancestry.com found a strong likelihood that Dunham was descended from

John Punch, an enslaved African man who lived in the

Colony of Virginia

The Colony of Virginia, chartered in 1606 and settled in 1607, was the first enduring English colony in North America, following failed attempts at settlement on Newfoundland by Sir Humphrey GilbertGilbert (Saunders Family), Sir Humphrey" (histor ...

during the seventeenth century.

["Ancestry.com Discovers Ph Suggests"](_blank)

, ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

''. July 30, 2012. Obama's father,

Barack Obama Sr. (1934–1982), was a married

from

Nyang'oma Kogelo

Nyang'oma Kogelo, also known as Kogelo, is a village in Siaya County, Kenya. It is located near the equator, 60 kilometres (37 mi) west-northwest of Kisumu, the former Nyanza provincial capital. The population of Nyangoma-Kogelo is 3,648 ...

.

Obama's parents met in 1960 in a

Russian language

Russian (russian: русский язык, russkij jazyk, link=no, ) is an East Slavic language mainly spoken in Russia. It is the native language of the Russians, and belongs to the Indo-European language family. It is one of four living E ...

class at the

University of Hawaii at Manoa

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States, th ...

, where his father was a foreign student on a scholarship.

[Obama (1995, 2004), pp. 9–10.

* Scott (2011), pp. 80–86.

* Jacobs (2011), pp. 115–118.

* Maraniss (2012), pp. 154–160.] The couple married in

Wailuku, Hawaii

Wailuku is a census-designated place (CDP) in and county seat of Maui County, Hawaii, United States. The population was 17,697 at the 2020 census.

Wailuku is located just west of Kahului, at the mouth of the Iao Valley. In the early 20th cent ...

, on February 2, 1961, six months before Obama was born.

In late August 1961, a few weeks after he was born, Barack and his mother moved to the

University of Washington

The University of Washington (UW, simply Washington, or informally U-Dub) is a public research university in Seattle, Washington.

Founded in 1861, Washington is one of the oldest universities on the West Coast; it was established in Seatt ...

in

Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest region o ...

, where they lived for a year. During that time, Barack's father completed his undergraduate degree in

economics

Economics () is the social science that studies the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interactions of economic agents and how economies work. Microeconomics anal ...

in Hawaii, graduating in June 1962. He left to attend graduate school on a scholarship at

Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of highe ...

, where he earned an

M.A.

A Master of Arts ( la, Magister Artium or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA, M.A., AM, or A.M.) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Tho ...

in economics. Obama's parents divorced in March 1964. Obama Sr. returned to Kenya in 1964, where he married for a third time and worked for the Kenyan government as the Senior Economic Analyst in the Ministry of Finance. He visited his son in Hawaii only once, at Christmas 1971, before he was killed in an automobile accident in 1982, when Obama was 21 years old. Recalling his early childhood, Obama said: "That my father looked nothing like the people around me—that he was black as pitch, my mother white as milk—barely registered in my mind."

He described his struggles as a young adult to reconcile social perceptions of his multiracial heritage.

In 1963, Dunham met

Lolo Soetoro

Lolo Soetoro ( EYD: Lolo Sutoro; ; 2 January 1935 Google Translate'sEnglish translationLolo studied geography at Gadjah Mada University and got a scholarship from the Indonesian Army Topographic Service. After working for the Indonesian Army Topo ...

at the

University of Hawaii

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States, th ...

; he was an

Indonesian East–West Center

The East–West Center (EWC), or the Center for Cultural and Technical Interchange Between East and West, is an education and research organization established by the U.S. Congress in 1960 to strengthen relations and understanding among the peop ...

graduate student

Postgraduate or graduate education refers to academic or professional degrees, certificates, diplomas, or other qualifications pursued by post-secondary students who have earned an undergraduate (bachelor's) degree.

The organization and s ...

in

geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, an ...

. The couple married on

Molokai

Molokai , or Molokai (), is the fifth most populated of the eight major islands that make up the Hawaiian Islands archipelago in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. It is 38 by 10 miles (61 by 16 km) at its greatest length and width with a us ...

on March 15, 1965. After two one-year extensions of his

J-1 visa

A J-1 visa is a non-immigrant visa issued by the United States to research scholars, professors and exchange visitors participating in programs that promote cultural exchange, especially to obtain medical or business training within the U.S. All ...

, Lolo returned to

Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Gui ...

in 1966. His wife and stepson followed sixteen months later in 1967. The family initially lived in the Menteng Dalam neighborhood in the

Tebet district of

South Jakarta

South Jakarta ( id, Jakarta Selatan; bew, Jakarte Beludik ), colloquially known as ''Jaksel'', is one of the five administrative cities which form the Special Capital Region of Jakarta, Indonesia. South Jakarta is not self-governed and does not ...

. From 1970, they lived in a wealthier neighborhood in the

Menteng district of

Central Jakarta

Central Jakarta ( id, Jakarta Pusat) is one of the five administrative cities () which form the Special Capital Region of Jakarta. It had 902,973 inhabitants according to the 2010 censusBiro Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2011. and 1,056,896 at the ...

.

Education

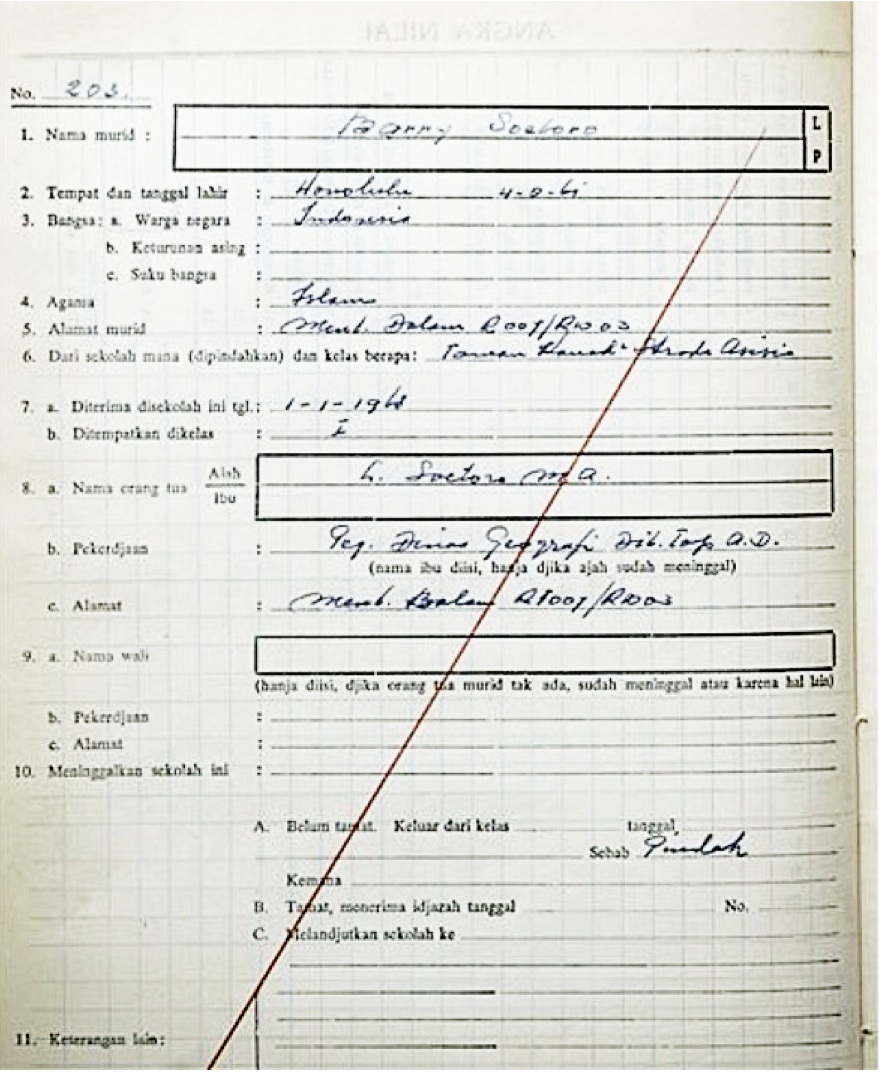

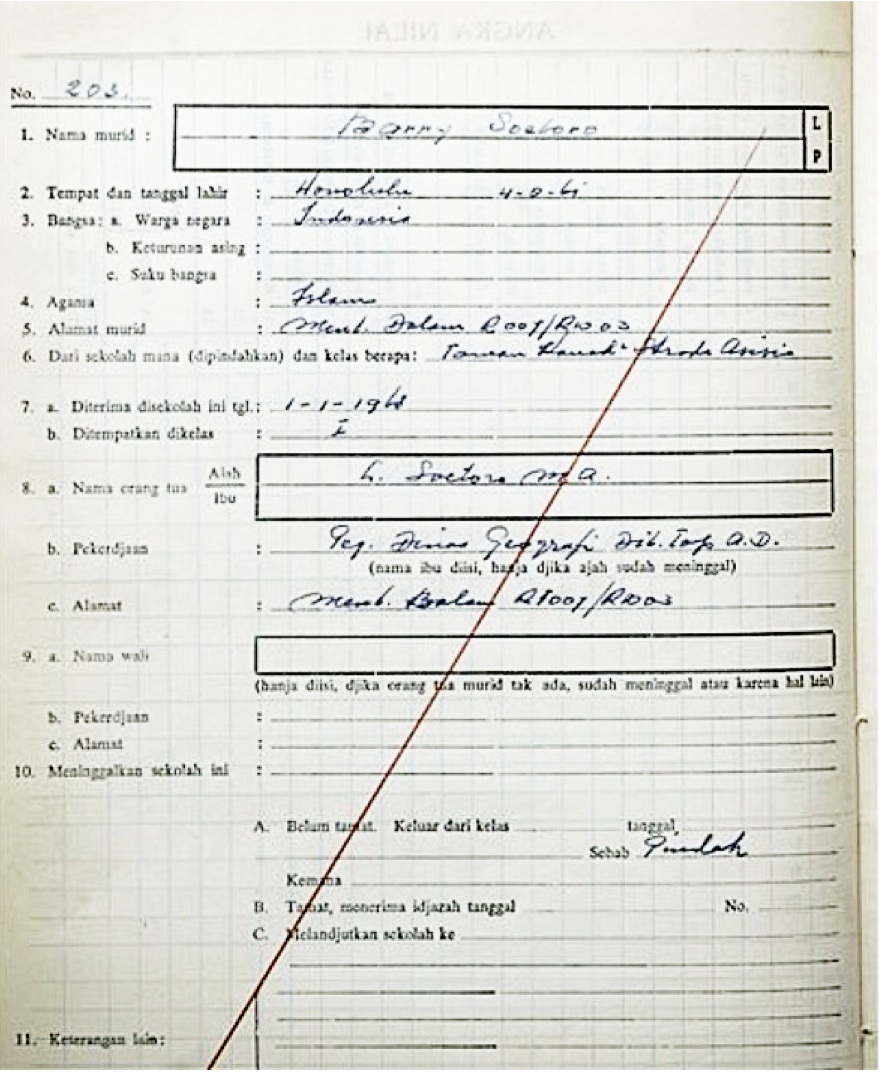

At the age of six, Obama and his mother had moved to Indonesia to join his stepfather. From age six to ten, he attended local

Indonesian-language schools: ''Sekolah Dasar Katolik Santo Fransiskus Asisi'' (St. Francis of Assisi Catholic Elementary School) for two years and

''Sekolah Dasar Negeri Menteng 01'' (State Elementary School Menteng 01) for one and a half years, supplemented by English-language

Calvert School

Calvert School, founded in 1897, is an independent, non-sectarian, co-educational lower and middle school located in Baltimore, Maryland.

Calvert School is a member of the National Association of Independent Schools (NAIS) as well as the Ass ...

homeschooling by his mother. As a result of his four years in

Jakarta

Jakarta (; , bew, Jakarte), officially the Special Capital Region of Jakarta ( id, Daerah Khusus Ibukota Jakarta) is the capital city, capital and list of Indonesian cities by population, largest city of Indonesia. Lying on the northwest coa ...

, he was able to speak

Indonesian fluently as a child.

During his time in Indonesia, Obama's stepfather taught him to be resilient and gave him "a pretty hardheaded assessment of how the world works."

In 1971, Obama returned to

Honolulu

Honolulu (; ) is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, which is in the Pacific Ocean. It is an unincorporated county seat of the consolidated City and County of Honolulu, situated along the southeast coast of the isla ...

to live with his maternal grandparents,

Madelyn and

Stanley Dunham. He attended

Punahou School

Punahou School (known as Oahu College until 1934) is a private, co-educational, college preparatory school in Honolulu, Hawaii. More than 3,700 students attend the school from kindergarten through 12th grade. Protestant missionaries establis ...

—a private

college preparatory school

A college-preparatory school (usually shortened to preparatory school or prep school) is a type of secondary school. The term refers to public, private independent or parochial schools primarily designed to prepare students for higher educat ...

—with the aid of a scholarship from fifth grade until he graduated from high school in 1979. In his youth, Obama went by the nickname "Barry." Obama lived with his mother and half-sister,

Maya Soetoro, in Hawaii for three years from 1972 to 1975 while his mother was a graduate student in

anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including past human species. Social anthropology studies patterns of be ...

at the

University of Hawaii

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States, th ...

. Obama chose to stay in Hawaii when his mother and half-sister returned to Indonesia in 1975, so his mother could begin anthropology field work. His mother spent most of the next two decades in Indonesia, divorcing Lolo in 1980 and earning a

PhD PHD or PhD may refer to:

* Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), an academic qualification

Entertainment

* '' PhD: Phantasy Degree'', a Korean comic series

* '' Piled Higher and Deeper'', a web comic

* Ph.D. (band), a 1980s British group

** Ph.D. (Ph.D. al ...

degree in 1992, before dying in 1995 in Hawaii following unsuccessful treatment for

ovarian and

uterine cancer

Uterine cancer, also known as womb cancer, includes two types of cancer that develop from the tissues of the uterus. Endometrial cancer forms from the lining of the uterus, and uterine sarcoma forms from the muscles or support tissue of the ut ...

.

Of his years in Honolulu, Obama wrote: "The opportunity that Hawaii offered — to experience a variety of cultures in a climate of mutual respect — became an integral part of my world view, and a basis for the values that I hold most dear." Obama has also written and talked about using

alcohol

Alcohol most commonly refers to:

* Alcohol (chemistry), an organic compound in which a hydroxyl group is bound to a carbon atom

* Alcohol (drug), an intoxicant found in alcoholic drinks

Alcohol may also refer to:

Chemicals

* Ethanol, one of sev ...

,

marijuana

Cannabis, also known as marijuana among other names, is a psychoactive drug from the cannabis plant. Native to Central or South Asia, the cannabis plant has been used as a drug for both recreational and entheogenic purposes and in various t ...

, and

cocaine

Cocaine (from , from , ultimately from Quechua: ''kúka'') is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant mainly used recreationally for its euphoric effects. It is primarily obtained from the leaves of two Coca species native to South Am ...

during his teenage years to "push questions of who I was out of my mind." Obama was also a member of the "choom gang", a self-named group of friends who spent time together and occasionally smoked marijuana.

College and research jobs

After graduating from high school in 1979, Obama moved to

Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world ...

to attend

Occidental College

Occidental College (informally Oxy) is a private liberal arts college in Los Angeles, California. Founded in 1887 as a coeducational college by clergy and members of the Presbyterian Church, it became non-sectarian in 1910. It is one of the oldes ...

on a full scholarship. In February 1981, Obama made his first public speech, calling for Occidental to participate in the

disinvestment from South Africa

Disinvestment (or divestment) from South Africa was first advocated in the 1960s, in protest against South Africa's system of apartheid, but was not implemented on a significant scale until the mid-1980s. The disinvestment campaign, after bein ...

in response to that nation's policy of

apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

.

In mid-1981, Obama traveled to Indonesia to visit his mother and half-sister Maya, and visited the families of college friends in

Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

for three weeks.

Later in 1981, he

transferred to

Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

in

New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

as a

junior, where he majored in

political science

Political science is the scientific study of politics. It is a social science dealing with systems of governance and power, and the analysis of political activities, political thought, political behavior, and associated constitutions and ...

with a specialty in

international relations

International relations (IR), sometimes referred to as international studies and international affairs, is the scientific study of interactions between sovereign states. In a broader sense, it concerns all activities between states—such ...

and in

English literature

English literature is literature written in the English language from United Kingdom, its crown dependencies, the Republic of Ireland, the United States, and the countries of the former British Empire. ''The Encyclopaedia Britannica'' defines E ...

and lived off-campus on West 109th Street. He graduated with a

Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four yea ...

degree in 1983 and a 3.7

GPA. After graduating, Obama worked for about a year at the

Business International Corporation

Business International Corporation (BI) was a publishing and advisory firm dedicated to assisting American companies in operating abroad. It was founded in 1953. It organized conferences, and worked with major corporations. Former president Barack ...

, where he was a financial researcher and writer, then as a project coordinator for the

New York Public Interest Research Group

The New York Public Interest Research Group (NYPIRG) is a New York statewide student-directed, non-partisan, not for profit political organization. It has existed since 1973. Its current executive director is Blair Horner and its founding directo ...

on the

City College of New York

The City College of the City University of New York (also known as the City College of New York, or simply City College or CCNY) is a public university within the City University of New York (CUNY) system in New York City. Founded in 1847, Cit ...

campus for three months in 1985.

Community organizer and Harvard Law School

Two years after graduating from Columbia, Obama moved from New York to Chicago when he was hired as director of the

Developing Communities Project

The Developing Communities Project (DCP) is a faith-based organization in Chicago, Illinois. DCP was organized in 1984 as a branch of the Calumet Community Religious Conference (CCRC) in response to lay-offs and plant closings in Southeast Chica ...

, a church-based community organization originally comprising eight Catholic parishes in

Roseland,

West Pullman, and

Riverdale on Chicago's

South Side. He worked there as a community organizer from June 1985 to May 1988.

He helped set up a job training program, a college preparatory tutoring program, and a tenants' rights organization in

Altgeld Gardens

Riverdale is one of the 77 official community areas of Chicago, Illinois and is located

on the city's far south side.

As originally designated by the Social Science Research Committee at the University of Chicago and officially adopted by the ...

.

[

* ] Obama also worked as a consultant and instructor for the

Gamaliel Foundation

Gamaliel Foundation provides training and consultation and develops national strategy for its affiliated congregation-based community organizations. As of 2013, Gamaliel has 45 affiliates in 17 U.S. states, the United Kingdom, and South Africa, ...

, a community organizing institute. In mid-1988, he traveled for the first time in Europe for three weeks and then for five weeks in Kenya, where he met many of his

paternal relatives for the first time.

Despite being offered a full scholarship to

Northwestern University School of Law

Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law is the law school of Northwestern University, a private research university. It is located on the university's Chicago campus. Northwestern Law has been ranked among the top 14, or "T14" law scho ...

, Obama enrolled at

Harvard Law School

Harvard Law School (Harvard Law or HLS) is the law school of Harvard University, a private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1817, it is the oldest continuously operating law school in the United States.

Each c ...

in the fall of 1988, living in nearby

Somerville, Massachusetts

Somerville ( ) is a city located directly to the northwest of Boston, and north of Cambridge, in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. As of the 2020 United States Census, the city had a total population of 81,045 people. With an area ...

. He was selected as an editor of the ''

Harvard Law Review

The ''Harvard Law Review'' is a law review published by an independent student group at Harvard Law School. According to the ''Journal Citation Reports'', the ''Harvard Law Review''s 2015 impact factor of 4.979 placed the journal first out of 143 ...

'' at the end of his first year,

[

*

*

* Mendell (2007), pp. 80–92.] president of the journal in his second year,

[

*

*

*

* ] and research assistant to the constitutional scholar

Laurence Tribe

Laurence Henry Tribe (born October 10, 1941) is an American legal scholar who is a University Professor Emeritus at Harvard University. He previously served as the Carl M. Loeb University Professor at Harvard Law School.

A constitutional law sc ...

while at Harvard. During his summers, he returned to Chicago, where he worked as a

summer associate at the law firms of

Sidley Austin

Sidley Austin LLP is an American multinational law firm with approximately 2,000 lawyers in 20 offices worldwide. The firm's headquarters is at One South Dearborn in Chicago's Loop. The firm specializes in a variety of areas in both litigati ...

in 1989 and

Hopkins & Sutter in 1990. Obama's election as the

first black president of the ''Harvard Law Review'' gained national media attention

and led to a publishing contract and advance for a book about race relations,

[

* Obama (1995, 2004), pp. xiii–xvii.] which evolved into a personal memoir. The manuscript was published in mid-1995 as ''

Dreams from My Father''.

Obama graduated from Harvard Law in 1991 with a

Juris Doctor

The Juris Doctor (J.D. or JD), also known as Doctor of Jurisprudence (J.D., JD, D.Jur., or DJur), is a graduate-entry professional degree in law

and one of several Doctor of Law degrees. The J.D. is the standard degree obtained to practice l ...

''

magna cum laude

Latin honors are a system of Latin phrases used in some colleges and universities to indicate the level of distinction with which an academic degree has been earned. The system is primarily used in the United States. It is also used in some Sou ...

''.

University of Chicago Law School

In 1991, Obama accepted a two-year position as Visiting Law and Government Fellow at the

University of Chicago Law School

The University of Chicago Law School is the law school of the University of Chicago, a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. It is consistently ranked among the best and most prestigious law schools in the world, and has many dis ...

to work on his first book.

He then taught

constitutional law

Constitutional law is a body of law which defines the role, powers, and structure of different entities within a state, namely, the executive, the parliament or legislature, and the judiciary; as well as the basic rights of citizens and, in fe ...

at the University of Chicago Law School for twelve years, first as a

lecturer

Lecturer is an academic rank within many universities, though the meaning of the term varies somewhat from country to country. It generally denotes an academic expert who is hired to teach on a full- or part-time basis. They may also conduct re ...

from 1992 to 1996, and then as a senior lecturer from 1996 to 2004.

From April to October 1992, Obama directed Illinois's

Project Vote

Project Vote (and Voting for America, Inc.) was a national nonpartisan, nonprofit 501(c)(3) organization that worked to mobilize marginalized and under-represented voters until it ceased operations on May 31, 2017. Project Vote's efforts to engage ...

, a

voter registration campaign with ten staffers and seven hundred volunteer registrars; it achieved its goal of registering 150,000 of 400,000 unregistered African Americans in the state, leading ''

Crain's Chicago Business

''Crain's Chicago Business'' is a weekly business newspaper in Chicago, Illinois, IL. It is owned by Detroit-based Crain Communications Inc., Crain Communications, a privately held publishing company with more than 30 magazines, including ''Adve ...

'' to name Obama to its 1993 list of "40 under Forty" powers to be.

Family and personal life

In a 2006 interview, Obama highlighted the diversity of

his extended family: "It's like a little mini-United Nations," he said. "I've got relatives who look like

Bernie Mac

Bernard Jeffrey McCullough (October 5, 1957 – August 9, 2008), better known by his stage name Bernie Mac, was an American comedian and actor. Born and raised on Chicago's South Side, Mac gained popularity as a stand-up comedian. He joined fell ...

, and I've got relatives who look like

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. She was the first female British prime ...

." Obama has a half-sister with whom he was raised (

Maya Soetoro-Ng

Maya Kasandra Soetoro-Ng (; ; born August 15, 1970) is an Indonesian-American academic, who is a faculty specialist at the Spark M. Matsunaga Institute for Peace and Conflict Resolution, based in the College of Social Sciences at the University ...

) and seven other half-siblings from his Kenyan father's family—six of them living. Obama's mother was survived by her Kansas-born mother,

Madelyn Dunham

Madelyn Lee Payne Dunham ( ; October 26, 1922 – November 2, 2008) was the American maternal grandmother of Barack Obama, the 44th president of the United States. She and her husband Stanley Armour Dunham raised Obama from age ten in their ...

, until her death on November 2, 2008, two days before his election to the presidency. Obama also has roots in Ireland; he met with his Irish cousins in

Moneygall

Moneygall () is a small village on the border of counties Offaly and Tipperary, in Ireland. It is situated on the R445 road between Dublin and Limerick. There were 313 people living in the village as of the 2016 census. Moneygall has a Catholic ...

in May 2011. In ''Dreams from My Father'', Obama ties his mother's family history to possible Native American ancestors and distant relatives of

Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as ...

,

President of the Confederate States of America

The president of the Confederate States was the head of state and head of government of the Confederate States. The president was the chief executive of the federal government and was the commander-in-chief of the Confederate Army and the Conf ...

during the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

. He also shares distant ancestors in common with

George W. Bush and

Dick Cheney

Richard Bruce Cheney ( ; born January 30, 1941) is an American politician and businessman who served as the 46th vice president of the United States from 2001 to 2009 under President George W. Bush. He is currently the oldest living former ...

, among others.

Obama lived with anthropologist

Sheila Miyoshi Jager

Sheila Miyoshi Jager (born 1963) is an American historian. She is a Professor of East Asian Studies at Oberlin College, author of two books on Korea, co-editor of a third book on Asian nations in the post-Cold War era, and a forthcoming book on gr ...

while he was a community organizer in Chicago in the 1980s.

He proposed to her twice, but both Jager and her parents turned him down.

The relationship was not made public until May 2017, several months after his presidency had ended.

In June 1989, Obama met

Michelle Robinson when he was employed as a summer associate at the Chicago law firm of

Sidley Austin

Sidley Austin LLP is an American multinational law firm with approximately 2,000 lawyers in 20 offices worldwide. The firm's headquarters is at One South Dearborn in Chicago's Loop. The firm specializes in a variety of areas in both litigati ...

. Robinson was assigned for three months as Obama's adviser at the firm, and she joined him at several group social functions but declined his initial requests to date. They began dating later that summer, became engaged in 1991, and were married on October 3, 1992. After suffering a miscarriage, Michelle underwent

in vitro fertilization to conceive their children. The couple's first daughter, Malia Ann, was born in 1998, followed by a second daughter, Natasha ("Sasha"), in 2001. The Obama daughters attended the

University of Chicago Laboratory Schools

The University of Chicago Laboratory Schools (also known as Lab or Lab Schools and abbreviated as UCLS though the high school is nicknamed U-High) is a private, co-educational day Pre-K and K-12 school in Chicago, Illinois. It is affiliated w ...

. When they moved to Washington, D.C., in January 2009, the girls started at the

Sidwell Friends School

Sidwell Friends School is a Quaker school located in Bethesda, Maryland and Washington, D.C., offering pre-kindergarten through high school classes. Founded in 1883 by Thomas W. Sidwell, its motto is ' ( en, Let the light shine out from all), a ...

. The Obamas had two

Portuguese Water Dog

The Portuguese Water Dog originated from the Algarve region of Portugal. From there the breed expanded to all around Portugal's coast, where they were taught to herd fish into fishermen's nets, retrieve lost tackle or broken nets, and act as ...

s; the first, a male named

Bo, was a gift from Senator

Ted Kennedy

Edward Moore Kennedy (February 22, 1932 – August 25, 2009) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a United States senator from Massachusetts for almost 47 years, from 1962 until his death in 2009. A member of the Democratic ...

. In 2013, Bo was joined by

Sunny, a female.

Bo died of cancer on May 8, 2021.

Obama is a supporter of the

Chicago White Sox

The Chicago White Sox are an American professional baseball team based in Chicago. The White Sox compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the American League (AL) Central division. The team is owned by Jerry Reinsdorf, and ...

, and he threw out the first pitch at the

2005 ALCS when he was still a senator. In 2009, he threw out the ceremonial first pitch at the

All-Star Game

An all-star game is an exhibition game that purports to showcase the best players (the "stars") of a sports league. The exhibition is between two teams organized solely for the event, usually representing the league's teams based on region or d ...

while wearing a White Sox jacket. He is also primarily a

Chicago Bears

The Chicago Bears are a professional American football team based in Chicago. The Bears compete in the National Football League (NFL) as a member club of the league's National Football Conference (NFC) North division. The Bears have won nine ...

football fan in the

NFL, but in his childhood and adolescence was a

fan of the Pittsburgh Steelers, and rooted for them ahead of their victory in

Super Bowl XLIII

Super Bowl XLIII was an American football game between the American Football Conference (AFC) champions Pittsburgh Steelers and the National Football Conference (NFC) champions Arizona Cardinals to decide the National Football League (NFL) champ ...

12 days after he took office as president.

In 2011, Obama invited the

1985 Chicago Bears

The year 1985 was designated as the International Youth Year by the United Nations.

Events January

* January 1

** The Internet's Domain Name System is created.

** Greenland withdraws from the European Economic Community as a result of a ...

to the White House; the team had not visited the White House after their

Super Bowl win in 1986 due to the

Space Shuttle Challenger disaster

On January 28, 1986, the broke apart 73 seconds into its flight, killing all seven crew members aboard. The spacecraft disintegrated above the Atlantic Ocean, off the coast of Cape Canaveral, Florida, at 11:39a.m. EST (16:39 UTC). It w ...

. He plays basketball, a sport he participated in as a member of his high school's varsity team, and he is left-handed.

In 2005, the Obama family applied the proceeds of a book deal and moved from a

Hyde Park, Chicago

Hyde Park is the 41st of the 77 community areas of Chicago. It is located on the South Side, near the shore of Lake Michigan south of the Loop.

Hyde Park's official boundaries are 51st Street/Hyde Park Boulevard on the north, the Midway Pl ...

condominium to a $1.6million house (equivalent to $million in ) in neighboring

Kenwood, Chicago

Kenwood, one of Chicago's 77 community areas, is on the shore of Lake Michigan on the South Side of the city. Its boundaries are 43rd Street, 51st Street, Cottage Grove Avenue, and the lake. Kenwood was originally part of Hyde Park Township, ...

. The purchase of an adjacent lot—and sale of part of it to Obama by the wife of developer, campaign donor and friend

Tony Rezko—attracted media attention because of Rezko's subsequent indictment and conviction on political corruption charges that were unrelated to Obama.

In December 2007, ''

Money Magazine

''Money'' is an American personal finance brand and website owned by Ad Practitioners LLC and formerly also a monthly magazine, first published by Time Inc. (1972–2018) and later by Meredith Corporation (2018–2019). Its articles cover the g ...

'' estimated Obama's net worth at $1.3million (equivalent to $million in ). Their 2009 tax return showed a household income of $5.5million—up from about $4.2million in 2007 and $1.6million in 2005—mostly from sales of his books. On his 2010 income of $1.7million, he gave 14 percent to non-profit organizations, including $131,000 to

Fisher House Foundation

Fisher House Foundation is a charity and foundation that builds comfort homes where military & veterans families can stay free of charge, while a loved one is in the hospital. Fisher Houses are located at major military and VA medical centers n ...

, a charity assisting wounded veterans' families, allowing them to reside near where the veteran is receiving medical treatments. Per his 2012 financial disclosure, Obama may be worth as much as $10million.

Last name

Obama's last name originates from

Luo people

The Luo of Kenya and Tanzania are a Nilotic ethnic group native to western Kenya and the Mara Region of northern Tanzania in East Africa. The Luo are the fourth-largest ethnic group (10.65%) in Kenya, after the Kikuyu (17.13%), the Luhya ( ...

. In Luo language, it means "bent over" or "limping".

Religious views

Obama is a

Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

Christian whose religious views developed in his adult life.

He wrote in ''

The Audacity of Hope'' that he "was not raised in a religious household." He described his mother, raised by non-religious parents, as being detached from religion, yet "in many ways the most spiritually awakened person... I have ever known", and "a lonely witness for

secular humanism

Secular humanism is a philosophy, belief system or life stance that embraces human reason, secular ethics, and philosophical naturalism while specifically rejecting religious dogma, supernaturalism, and superstition as the basis of morality ...

." He described his father as a "confirmed

atheist

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

" by the time his parents met, and his stepfather as "a man who saw religion as not particularly useful." Obama explained how, through working with

black church

The black church (sometimes termed Black Christianity or African American Christianity) is the faith and body of Christian congregations and denominations in the United States that minister predominantly to African Americans, as well as their ...

es as a

community organizer

Community organizing is a process where people who live in proximity to each other or share some common problem come together into an organization that acts in their shared self-interest.

Unlike those who promote more-consensual community bui ...

while in his twenties, he came to understand "the power of the African-American religious tradition to spur social change."

In January 2008, Obama told ''

Christianity Today

''Christianity Today'' is an evangelical Christian media magazine founded in 1956 by Billy Graham. It is published by Christianity Today International based in Carol Stream, Illinois. ''The Washington Post'' calls ''Christianity Today'' "evan ...

'': "I am a Christian, and I am a devout Christian. I believe in the

redemptive death and

resurrection of Jesus Christ

The resurrection of Jesus ( grc-x-biblical, ἀνάστασις τοῦ Ἰησοῦ) is the Christian belief that God raised Jesus on the third day after his crucifixion, starting – or restoring – his exalted life as Christ and L ...

. I believe that faith gives me a path to be cleansed of sin and have eternal life." On September 27, 2010, Obama released a statement commenting on his religious views, saying:

Obama met

Trinity United Church of Christ

Trinity United Church of Christ is a predominantly African-American church with more than 8,500 members. It is located in the Washington Heights community on the South Side of Chicago. It is the largest church affiliated with the United Chur ...

pastor

Jeremiah Wright

Jeremiah Alvesta Wright Jr. (born September 22, 1941) is a pastor emeritus of Trinity United Church of Christ in Chicago, a congregation he led for 36 years, during which its membership grew to over 8,000 parishioners. Following retirement, his be ...

in October 1987 and became a member of Trinity in 1992.

During Obama's first presidential campaign in May 2008, he resigned from Trinity after

some of Wright's statements were criticized. Since moving to Washington, D.C., in 2009, the Obama family has attended several Protestant churches, including

Shiloh Baptist Church and

St. John's Episcopal Church, as well as Evergreen Chapel at

Camp David

Camp David is the country retreat for the president of the United States of America. It is located in the wooded hills of Catoctin Mountain Park, in Frederick County, Maryland, near the towns of Thurmont and Emmitsburg, about north-northwest ...

, but the members of the family do not attend church on a regular basis.

In 2016, he said that he gets inspiration from a few items that remind him "of all the different people I've met along the way", adding: "I carry these around all the time. I'm not that superstitious, so it's not like I think I necessarily have to have them on me at all times." The items, "a whole bowl full", include rosary beads given to him by

Pope Francis

Pope Francis ( la, Franciscus; it, Francesco; es, link=, Francisco; born Jorge Mario Bergoglio, 17 December 1936) is the head of the Catholic Church. He has been the bishop of Rome and sovereign of the Vatican City State since 13 March 2013 ...

, a figurine of the Hindu deity

Hanuman

Hanuman (; sa, हनुमान, ), also called Anjaneya (), is a Hindu god and a divine '' vanara'' companion of the god Rama. Hanuman is one of the central characters of the Hindu epic ''Ramayana''. He is an ardent devotee of Rama and on ...

, a

Coptic cross

The Coptic cross refers to a number of Christian cross variants associated in some way with Coptic Christians.

Typical form

The typical form of the "Coptic cross" used in the Coptic Church is made up of two bold lines of equal length that in ...

from Ethiopia, a small

Buddha statue

Much Buddhist art uses depictions of the historical Buddha, Gautama Buddha, which are known as Buddharūpa (literally, "Form of the Awakened One") in Sanskrit and Pali. These may be statues or other images such as paintings. The main figure i ...

given by a monk, and a metal poker chip that used to be the lucky charm of a motorcyclist in Iowa.

Legal career

Civil Rights attorney

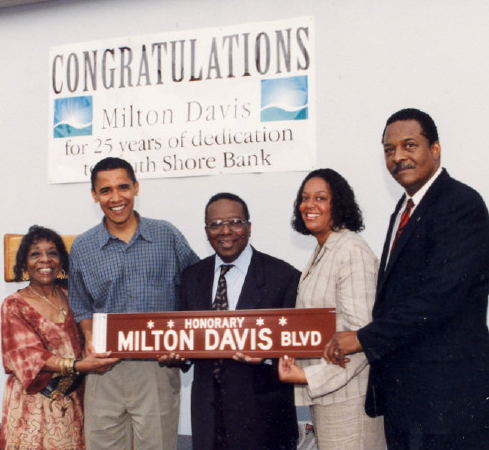

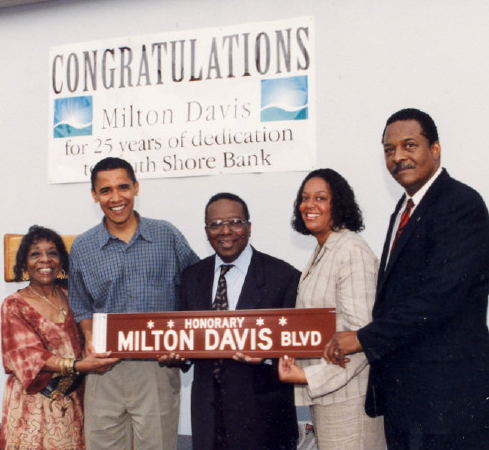

He joined Davis, Miner, Barnhill & Galland, a 13-attorney law firm specializing in civil rights litigation and neighborhood economic development, where he was an

associate for three years from 1993 to 1996, then

of counsel from 1996 to 2004. In 1994, he was listed as one of the lawyers in ''Buycks-Roberson v. Citibank Fed. Sav. Bank'', 94 C 4094 (N.D. Ill.). This

class action lawsuit

A class action, also known as a class-action lawsuit, class suit, or representative action, is a type of lawsuit where one of the parties is a group of people who are represented collectively by a member or members of that group. The class actio ...

was filed in 1994 with Selma Buycks-Roberson as lead plaintiff and alleged that Citibank Federal Savings Bank had engaged in practices forbidden under the

Equal Credit Opportunity Act

The Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA) is a United States law (codified at et seq.), enacted 28 October 1974, that makes it unlawful for any creditor to discriminate against any applicant, with respect to any aspect of a credit transaction, on ...

and the

Fair Housing Act

The Civil Rights Act of 1968 () is a landmark law in the United States signed into law by United States President Lyndon B. Johnson during the King assassination riots.

Titles II through VII comprise the Indian Civil Rights Act, which appl ...

. The case was settled out of court. Final judgment was issued on May 13, 1998, with Citibank Federal Savings Bank agreeing to pay attorney fees.

From 1994 to 2002, Obama served on the boards of directors of the

Woods Fund of Chicago—which in 1985 had been the first foundation to fund the Developing Communities Project—and of the

Joyce Foundation

The Joyce Foundation is a non-operating private foundation based in Chicago, Illinois. As of 2021, it had assets of approximately $1.1 billion and distributes $50 million in grants per year and primarily funds organizations in the Great Lakes re ...

.

He served on the board of directors of the

Chicago Annenberg Challenge

The Chicago Annenberg Challenge (CAC) was a Chicago public school reform project from 1995 to 2001 that worked with half of Chicago's public schools and was funded by a $49.2 million, 2-to-1 matching challenge grant over five years from the Annenbe ...

from 1995 to 2002, as founding president and chairman of the board of directors from 1995 to 1999.

Obama's law license became inactive in 2007.

Legislative career

Illinois Senate (1997–2004)

Obama was elected to the

Illinois Senate

The Illinois Senate is the upper chamber of the Illinois General Assembly, the legislative branch of the government of the State of Illinois in the United States. The body was created by the first state constitution adopted in 1818. Under the ...

in 1996, succeeding Democratic State Senator

Alice Palmer from Illinois's 13th District, which, at that time, spanned Chicago South Side neighborhoods from

Hyde Park–

Kenwood south to

South Shore and west to

Chicago Lawn. Once elected, Obama gained bipartisan support for legislation that reformed ethics and health care laws. He sponsored a law that increased

tax credit

A tax credit is a tax incentive which allows certain taxpayers to subtract the amount of the credit they have accrued from the total they owe the state. It may also be a credit granted in recognition of taxes already paid or a form of state "dis ...

s for low-income workers, negotiated

welfare reform, and promoted increased subsidies for childcare.

In 2001, as co-chairman of the bipartisan Joint Committee on Administrative Rules, Obama supported Republican Governor Ryan's

payday loan

A payday loan (also called a payday advance, salary loan, payroll loan, small dollar loan, short term, or cash advance loan) is a short-term unsecured loan, often characterized by high interest rates.

The term "payday" in payday loan refers to ...

regulations and

predatory mortgage lending Predatory lending refers to unethical practices conducted by lending organizations during a loan origination process that are unfair, deceptive, or fraudulent. While there are no internationally agreed legal definitions for predatory lending, a 2006 ...

regulations aimed at averting home

foreclosure

Foreclosure is a legal process in which a lender attempts to recover the balance of a loan from a borrower who has stopped making payments to the lender by forcing the sale of the asset used as the collateral for the loan.

Formally, a mort ...

s.

He was reelected to the Illinois Senate in 1998, defeating Republican Yesse Yehudah in the general election, and was re-elected again in 2002. In 2000, he lost a

Democratic primary race for

Illinois's 1st congressional district

Illinois's first congressional district is a congressional district in the U.S. state of Illinois. Based in Cook County, the district includes much of the South Side of Chicago, and continues southwest to Joliet.

From 2003 to early 2013 it ext ...

in the

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

to four-term incumbent

Bobby Rush

Bobby Lee Rush (born November 23, 1946) is an American politician, activist and pastor who served as the U.S. representative for for three decades. A civil rights activist during the 1960s, Rush co-founded the Illinois chapter of the Black Pant ...

by a margin of two to one.

In January 2003, Obama became chairman of the Illinois Senate's Health and Human Services Committee when Democrats, after a decade in the minority, regained a majority. He sponsored and led unanimous, bipartisan passage of legislation to monitor

racial profiling

Racial profiling or ethnic profiling is the act of suspecting, targeting or discriminating against a person on the basis of their ethnicity, religion or nationality, rather than on individual suspicion or available evidence. Racial profiling involv ...

by requiring police to record the race of drivers they detained, and legislation making Illinois the first state to mandate videotaping of homicide interrogations.

During his 2004 general election campaign for the U.S. Senate, police representatives credited Obama for his active engagement with police organizations in enacting

death penalty

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that ...

reforms. Obama resigned from the Illinois Senate in November 2004 following his election to the U.S. Senate.

2004 U.S. Senate campaign

In May 2002, Obama commissioned a poll to assess his prospects in a 2004 U.S. Senate race. He created a campaign committee, began raising funds, and lined up political media consultant

David Axelrod by August 2002. Obama formally announced his candidacy in January 2003.

Obama was an early opponent of the

George W. Bush administration's

2003 invasion of Iraq

The 2003 invasion of Iraq was a United States-led invasion of the Republic of Iraq and the first stage of the Iraq War. The invasion phase began on 19 March 2003 (air) and 20 March 2003 (ground) and lasted just over one month, including ...

. On October 2, 2002, the day President Bush and Congress agreed on the

joint resolution

In the United States Congress, a joint resolution is a legislative measure that requires passage by the Senate and the House of Representatives and is presented to the President for their approval or disapproval. Generally, there is no legal diff ...

authorizing the

Iraq War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Iraq War {{Nobold, {{lang, ar, حرب العراق (Arabic) {{Nobold, {{lang, ku, شەڕی عێراق (Kurdish languages, Kurdish)

, partof = the Iraq conflict (2003–present), I ...

,

Obama addressed the first high-profile Chicago

anti-Iraq War rally,

and spoke out against the war.

He addressed another anti-war rally in March 2003 and told the crowd "it's not too late" to stop the war.

Decisions by Republican incumbent

Peter Fitzgerald and his Democratic predecessor

Carol Moseley Braun

Carol Elizabeth Moseley Braun, also sometimes Moseley-Braun (born August 16, 1947), is a former U.S. Senator, an American diplomat, politician, and lawyer who represented Illinois in the United States Senate from 1993 to 1999. Prior to her Senate ...

to not participate in the election resulted in wide-open Democratic and Republican primary contests involving 15 candidates. In the March 2004 primary election, Obama won in an unexpected landslide—which overnight made him a rising star within the

national Democratic Party, started speculation about a presidential future, and led to the reissue of his memoir, ''Dreams from My Father''.

In July 2004, Obama delivered the keynote address at the

2004 Democratic National Convention

The 2004 Democratic National Convention convened from July 26 to 29, 2004 at the FleetCenter (now the TD Garden) in Boston, Massachusetts, and nominated Senator John Kerry from Massachusetts for president and Senator John Edwards from North ...

, seen by nine million viewers. His speech was well received and elevated his status within the Democratic Party.

Obama's expected opponent in the general election, Republican primary winner

Jack Ryan, withdrew from the race in June 2004. Six weeks later,

Alan Keyes

Alan Lee Keyes (born August 7, 1950) is an American politician, political activist, author, and perennial candidate who served as the Assistant Secretary of State for International Organization Affairs from 1985 to 1987. A member of the Repub ...

accepted the Republican nomination to replace Ryan. In the

November 2004 general election, Obama won with 70 percent of the vote, the largest margin of victory for a Senate candidate in Illinois history.

He took 92 of the state's 102 counties, including several where Democrats traditionally do not do well.

U.S. Senate (2005–2008)

Obama was sworn in as a senator on January 3, 2005, becoming the only Senate member of the

Congressional Black Caucus

The Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) is a caucus made up of most African-American members of the United States Congress. Representative Karen Bass from California chaired the caucus from 2019 to 2021; she was succeeded by Representative Joyce B ...

. He introduced two initiatives that bore his name: Lugar–Obama, which expanded the

Nunn–Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction

As the collapse of the Soviet Union appeared imminent, the United States and their NATO allies grew concerned of the risk of nuclear weapons held in the Soviet republics falling into enemy hands. The Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR) program was ...

concept to conventional weapons; and the

Federal Funding Accountability and Transparency Act of 2006

The Federal Funding Accountability and Transparency Act of 2006 (S. 2590) is an Act of Congress that requires the full disclosure to the public of all entities or organizations receiving federal funds beginning in fiscal year (FY) 2007. The websit ...

, which authorized the establishment of USAspending.gov, a web search engine on federal spending. On June 3, 2008, Senator Obama—along with Senators

Tom Carper

Thomas Richard Carper (born January 23, 1947) is an American politician and former military officer serving as the senior United States senator from Delaware, having held the seat since 2001. A member of the Democratic Party, Carper served i ...

,

Tom Coburn

Thomas Allen Coburn (March 14, 1948 – March 28, 2020) was an American politician and physician who served as a United States senator for Oklahoma from 2005, until his resignation in 2015. A Republican, he previously served as a United St ...

, and

John McCain

John Sidney McCain III (August 29, 1936 – August 25, 2018) was an American politician and United States Navy officer who served as a United States senator from Arizona from 1987 until his death in 2018. He previously served two te ...

—introduced follow-up legislation: Strengthening Transparency and Accountability in Federal Spending Act of 2008. He also

cosponsored the

Secure America and Orderly Immigration Act

Secure America and Orderly Immigration Act ("McCain-Kennedy Bill," ) was an immigration reform bill introduced in the United States Senate on May 12, 2005 by Senators John McCain and Ted Kennedy. It was the first of its kind since the early 2000s ...

.

In December 2006, President Bush signed into law the

Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (french: République démocratique du Congo (RDC), colloquially "La RDC" ), informally Congo-Kinshasa, DR Congo, the DRC, the DROC, or the Congo, and formerly and also colloquially Zaire, is a country in ...

Relief, Security, and Democracy Promotion Act, marking the first federal legislation to be enacted with Obama as its primary sponsor. In January 2007, Obama and Senator Feingold introduced a corporate jet provision to the

Honest Leadership and Open Government Act

The Honest Leadership and Open Government Act of 2007 () is a law of the United States federal government that amended parts of the Lobbying Disclosure Act of 1995. It strengthens public disclosure requirements concerning lobbying activity an ...

, which was signed into law in September 2007.

Later in 2007, Obama sponsored an amendment to the Defense Authorization Act to add safeguards for personality-disorder military discharges. This amendment passed the full Senate in the spring of 2008. He sponsored the

Iran Sanctions Enabling Act supporting divestment of state pension funds from Iran's oil and gas industry, which was never enacted but later incorporated in the

; and co-sponsored legislation to reduce risks of nuclear terrorism.

Obama also sponsored a Senate amendment to the

State Children's Health Insurance Program

The Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP) – formerly known as the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) – is a program administered by the United States Department of Health and Human Services that provides matching funds to ...

, providing one year of job protection for family members caring for soldiers with combat-related injuries.

Obama held assignments on the Senate Committees for

Foreign Relations

A state's foreign policy or external policy (as opposed to internal or domestic policy) is its objectives and activities in relation to its interactions with other states, unions, and other political entities, whether bilaterally or through m ...

,

Environment and Public Works and

Veterans' Affairs

Veterans' affairs is an area of public policy concerned with relations between a government and its communities of military veterans. Some jurisdictions have a designated government agency or department, a Department of Veterans' Affairs, Minist ...

through December 2006. In January 2007, he left the Environment and Public Works committee and took additional assignments with

Health, Education, Labor and Pensions and

Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs. He also became Chairman of the Senate's subcommittee on

European Affairs

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

. As a member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Obama made official trips to Eastern Europe, the Middle East, Central Asia and Africa. He met with

Mahmoud Abbas

Mahmoud Abbas ( ar, مَحْمُود عَبَّاس, Maḥmūd ʿAbbās; born 15 November 1935), also known by the kunya Abu Mazen ( ar, أَبُو مَازِن, links=no, ), is the president of the State of Palestine and the Palestinian Nati ...

before Abbas became

President of the Palestinian National Authority

The president of the Palestinian National Authority ( ar, رئيس السلطة الوطنية الفلسطينية) is the highest-ranking political position (equivalent to head of state) in the Palestinian National Authority (PNA). The presiden ...

, and gave a speech at the

University of Nairobi

The University of Nairobi (uonbi or UoN; ) is a collegiate research university based in Nairobi. It is the largest university in Kenya. Although its history as an educational institution dates back to 1956, it did not become an independent univer ...

in which he condemned corruption within the Kenyan government.

Obama

resigned his Senate seat on November 16, 2008, to focus on his transition period for the presidency.

Presidential campaigns

2008

On February 10, 2007, Obama announced his candidacy for President of the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

in front of the

Old State Capitol building in

Springfield, Illinois

Springfield is the capital of the U.S. state of Illinois and the county seat and largest city of Sangamon County. The city's population was 114,394 at the 2020 census, which makes it the state's seventh most-populous city, the second largest ...

.

The choice of the announcement site was viewed as symbolic, as it was also where

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

delivered his

"House Divided" speech in 1858.

Obama emphasized issues of rapidly ending the

Iraq War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Iraq War {{Nobold, {{lang, ar, حرب العراق (Arabic) {{Nobold, {{lang, ku, شەڕی عێراق (Kurdish languages, Kurdish)

, partof = the Iraq conflict (2003–present), I ...

, increasing

energy independence, and

reforming the health care system.

Numerous candidates entered the

Democratic Party presidential primaries

This is a list of Democratic Party presidential primaries.

1912

This was the first time that candidates were chosen through primaries. New Jersey Governor Woodrow Wilson ran to become the nominee, and faced the opposition of Speaker of the Unit ...

. The field narrowed to Obama and Senator

Hillary Clinton

Hillary Diane Rodham Clinton ( Rodham; born October 26, 1947) is an American politician, diplomat, and former lawyer who served as the 67th United States Secretary of State for President Barack Obama from 2009 to 2013, as a United States sen ...

after early contests, with the race remaining close throughout the primary process, but with Obama gaining a steady lead in pledged

delegates due to better long-range planning, superior fundraising, dominant organizing in

caucus

A caucus is a meeting of supporters or members of a specific political party or movement. The exact definition varies between different countries and political cultures.

The term originated in the United States, where it can refer to a meeting ...

states, and better exploitation of delegate allocation rules.

On June 2, 2008, Obama had received enough votes to clinch his election. After an initial hesitation to concede, on June 7, Clinton ended her campaign and endorsed Obama.

On August 23, 2008, Obama announced his

selection

Selection may refer to:

Science

* Selection (biology), also called natural selection, selection in evolution

** Sex selection, in genetics

** Mate selection, in mating

** Sexual selection in humans, in human sexuality

** Human mating strateg ...

of

Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent ...

Senator

Joe Biden as his vice presidential running mate.

Obama selected Biden from a field speculated to include former Indiana Governor and Senator

Evan Bayh

Birch Evans Bayh III ( ; born December 26, 1955) is an American lawyer, lobbyist, and Democratic Party politician who served as a United States senator from Indiana from 1999 to 2011 and the 46th governor of Indiana from 1989 to 1997.

Bayh ...

and Virginia Governor

Tim Kaine

Timothy Michael Kaine (; born February 26, 1958) is an American lawyer and politician serving as the junior United States senator from Virginia since 2013. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as the 38th lieutenant governor of Virgi ...

.

At the

Democratic National Convention

The Democratic National Convention (DNC) is a series of presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1832 by the United States Democratic Party. They have been administered by the Democratic National Committee since the 18 ...

in

Denver