In

mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

, the axiom of choice, or AC, is an

axiom

An axiom, postulate, or assumption is a statement that is taken to be true, to serve as a premise or starting point for further reasoning and arguments. The word comes from the Ancient Greek word (), meaning 'that which is thought worthy or f ...

of

set theory equivalent to the statement that ''a

Cartesian product

In mathematics, specifically set theory, the Cartesian product of two sets ''A'' and ''B'', denoted ''A''×''B'', is the set of all ordered pairs where ''a'' is in ''A'' and ''b'' is in ''B''. In terms of set-builder notation, that is

: A\ti ...

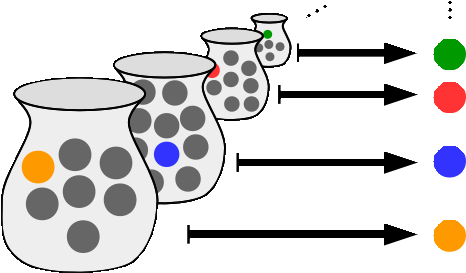

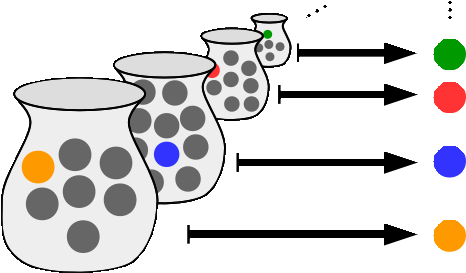

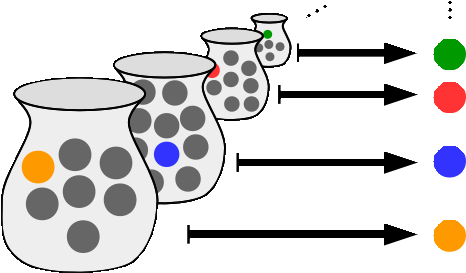

of a collection of non-empty sets is non-empty''. Informally put, the axiom of choice says that given any collection of sets, each containing at least one element, it is possible to construct a new set by arbitrarily choosing one element from each set, even if the collection is

infinite. Formally, it states that for every

indexed family of

nonempty sets, there exists an indexed set

such that

for every

. The axiom of choice was formulated in 1904 by

Ernst Zermelo in order to formalize his proof of the

well-ordering theorem.

In many cases, a set arising from choosing elements arbitrarily can be made without invoking the axiom of choice; this is, in particular, the case if the number of sets from which to choose the elements is finite, or if a canonical rule on how to choose the elements is available – some distinguishing property that happens to hold for exactly one element in each set. An illustrative example is sets picked from the natural numbers. From such sets, one may always select the smallest number, e.g. given the sets

the set containing each smallest element is . In this case, "select the smallest number" is a

choice function. Even if infinitely many sets were collected from the natural numbers, it will always be possible to choose the smallest element from each set to produce a set. That is, the choice function provides the set of chosen elements. However, no definite choice function is known for the collection of all non-empty subsets of the real numbers (if there are

non-constructible reals). In that case, the axiom of choice must be invoked.

Bertrand Russell coined an analogy: for any (even infinite) collection of pairs of shoes, one can pick out the left shoe from each pair to obtain an appropriate collection (i.e. set) of shoes; this makes it possible to define a choice function directly. For an ''infinite'' collection of pairs of socks (assumed to have no distinguishing features), there is no obvious way to make a function that forms a set out of selecting one sock from each pair, without invoking the axiom of choice.

Although originally controversial, the axiom of choice is now used without reservation by most mathematicians, and it is included in the standard form of

axiomatic set theory

Set theory is the branch of mathematical logic that studies Set (mathematics), sets, which can be informally described as collections of objects. Although objects of any kind can be collected into a set, set theory, as a branch of mathematics, ...

, Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory with the axiom of choice (

ZFC). One motivation for this use is that a number of generally accepted mathematical results, such as

Tychonoff's theorem, require the axiom of choice for their proofs. Contemporary set theorists also study axioms that are not compatible with the axiom of choice, such as the

axiom of determinacy. The axiom of choice is avoided in some varieties of

constructive mathematics, although there are varieties of constructive mathematics in which the axiom of choice is embraced.

Statement

A

choice function (also called selector or selection) is a function ''f'', defined on a collection ''X'' of nonempty sets, such that for every set ''A'' in ''X'', ''f''(''A'') is an element of ''A''. With this concept, the axiom can be stated:

Formally, this may be expressed as follows:

:

Thus, the

negation

In logic, negation, also called the logical complement, is an operation that takes a proposition P to another proposition "not P", written \neg P, \mathord P or \overline. It is interpreted intuitively as being true when P is false, and false ...

of the axiom of choice states that there exists a collection of nonempty sets that has no choice function. (

In

In  In

In