The Alhambra (, ; ar, الْحَمْرَاء, Al-Ḥamrāʾ, , ) is a palace and fortress complex located in

Granada

Granada (,, DIN 31635, DIN: ; grc, Ἐλιβύργη, Elibýrgē; la, Illiberis or . ) is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the fo ...

,

Andalusia

Andalusia (, ; es, Andalucía ) is the southernmost Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Peninsular Spain. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomous community in the country. It is officially recognised as a ...

,

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

. It is one of the most famous monuments of

Islamic architecture

Islamic architecture comprises the architectural styles of buildings associated with Islam. It encompasses both secular and religious styles from the early history of Islam to the present day. The Islamic world encompasses a wide geographic ar ...

and one of the best-preserved palaces of the historic

Islamic world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. In ...

, in addition to containing notable examples of Spanish

Renaissance architecture

Renaissance architecture is the European architecture of the period between the early 15th and early 16th centuries in different regions, demonstrating a conscious revival and development of certain elements of Ancient Greece, ancient Greek and ...

.

The complex was begun in 1238 by

Muhammad I Ibn al-Ahmar, the first

Nasrid emir and founder of the

Emirate of Granada

)

, common_languages = Official language: Classical ArabicOther languages: Andalusi Arabic, Mozarabic, Berber, Ladino

, capital = Granada

, religion = Majority religion: Sunni IslamMinority religions: Ro ...

, the last Muslim state of

Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus DIN 31635, translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label=Berber languages, Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, ...

.

It was built on the Sabika hill, an outcrop of the

Sierra Nevada

The Sierra Nevada () is a mountain range in the Western United States, between the Central Valley of California and the Great Basin. The vast majority of the range lies in the state of California, although the Carson Range spur lies primarily ...

which had been the site of earlier fortresses and of the 11th-century palace of

Samuel ibn Naghrillah.

Later Nasrid rulers continuously modified the site. The most significant construction campaigns, which gave the royal palaces much of their definitive character, took place in the 14th century during the reigns of

Yusuf I

Abu al-Hajjaj Yusuf ibn Ismail ( ar, أبو الحجاج يوسف بن إسماعيل; 29 June 131819 October 1354), known by the regnal name al-Muayyad billah (, "He who is aided by God"), was the seventh Nasrid ruler of the Emirate of Gran ...

and

Muhammad V. After the conclusion of the Christian

Reconquista

The ' (Spanish, Portuguese and Galician for "reconquest") is a historiographical construction describing the 781-year period in the history of the Iberian Peninsula between the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in 711 and the fall of the Nasrid ...

in 1492, the site became the Royal Court of

Ferdinand and Isabella

The Catholic Monarchs were Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon, whose marriage and joint rule marked the ''de facto'' unification of Spain. They were both from the House of Trastámara and were second cousins, being both ...

(where

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

received royal endorsement for his expedition), and the palaces were partially altered. In 1526,

Charles V Charles V may refer to:

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

* Charles V, Duke of Lorraine (1643–1690)

* Infan ...

commissioned a new

Renaissance-style palace in direct juxtaposition with the Nasrid palaces, but it was left uncompleted in the early 17th century. After being allowed to fall into disrepair for centuries, with its buildings occupied by

squatters

Squatting is the action of occupying an abandoned or unoccupied area of land or a building, usually residential, that the squatter does not own, rent or otherwise have lawful permission to use. The United Nations estimated in 2003 that there ...

, the Alhambra was rediscovered following the defeat of

Napoleon I

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

, whose troops destroyed parts of the site. The rediscoverers were first British intellectuals and then other American and northern European

Romantic travelers. The most influential of them was

Washington Irving

Washington Irving (April 3, 1783 – November 28, 1859) was an American short-story writer, essayist, biographer, historian, and diplomat of the early 19th century. He is best known for his short stories "Rip Van Winkle" (1819) and " The Legen ...

, whose ''

Tales of the Alhambra

''Tales of the Alhambra'' (1832) is a collection of essays, verbal sketches and stories by American author Washington Irving (1783–1859) inspired by, and partly written during, his 1828 visit to the palace/fortress complex known as the Alhambr ...

'' (1832) brought international attention to the site. The Alhambra was one of the first Islamic monuments to become the object of modern scientific study and has been the subject of numerous restorations since the 19th century. It is now one of Spain's major tourist attractions and a

UNESCO World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for h ...

.

During the Nasrid era, the Alhambra was a self-contained city separate from the rest of Granada below. It contained most of the amenities of a Muslim city such as a

Friday mosque

A congregational mosque or Friday mosque (, ''masjid jāmi‘'', or simply: , ''jāmi‘''; ), or sometimes great mosque or grand mosque (, ''jāmi‘ kabir''; ), is a mosque for hosting the Friday noon prayers known as ''jumu'ah''.*

*

*

*

*

*

*

...

,

hammams (public baths), roads, houses, artisan workshops, a

tannery

Tanning may refer to:

*Tanning (leather), treating animal skins to produce leather

*Sun tanning, using the sun to darken pale skin

**Indoor tanning, the use of artificial light in place of the sun

**Sunless tanning, application of a stain or dye t ...

, and a sophisticated water supply system. As a royal city and citadel, it contained at least six major palaces, most of them located along the northern edge where they commanded views over the

Albaicín

The Albaicín (), also known as Albayzín (from ar, ٱلْبَيّازِينْ, translit=al-Bayyāzīn), is a district of Granada, in the autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. It is centered around a hill on the north side of the Darro Rive ...

quarter. The most famous and best-preserved are the

Mexuar

The Mexuar (; ) is a section of the Nasrid palace complex in the Alhambra of Granada, Spain. It served as the entrance wing of the Comares Palace, the official palace of the sultan and the state, and it housed various administrative functions. Af ...

, the

Comares Palace, the

Palace of the Lions, and the

Partal Palace

Partal Palace () is a palatial structure inside the Alhambra fortress complex located in Granada, Spain. It was originally built in the early 14th century by the Nasrid ruler Muhammad III, making it the oldest surviving palatial structure in ...

, which form the main attraction to visitors today. The other palaces are known from historical sources and from modern excavations. At the Alhambra's western tip is the

Alcazaba fortress. Multiple smaller towers and fortified gates are also located along the Alhambra's walls. Outside the Alhambra walls and located nearby to the east is the

Generalife

The Generalife (; ar, جَنَّة الْعَرِيف, translit=Jannat al-‘Arīf) was a summer palace and country estate of the Nasrid rulers of the Emirate of Granada in Al-Andalus. It is located directly east of and uphill from the Alham ...

, a former Nasrid country estate and summer palace accompanied by historic

orchards

An orchard is an intentional plantation of trees or shrubs that is maintained for food production. Orchards comprise fruit- or nut-producing trees which are generally grown for commercial production. Orchards are also sometimes a feature of lar ...

and modern landscaped gardens.

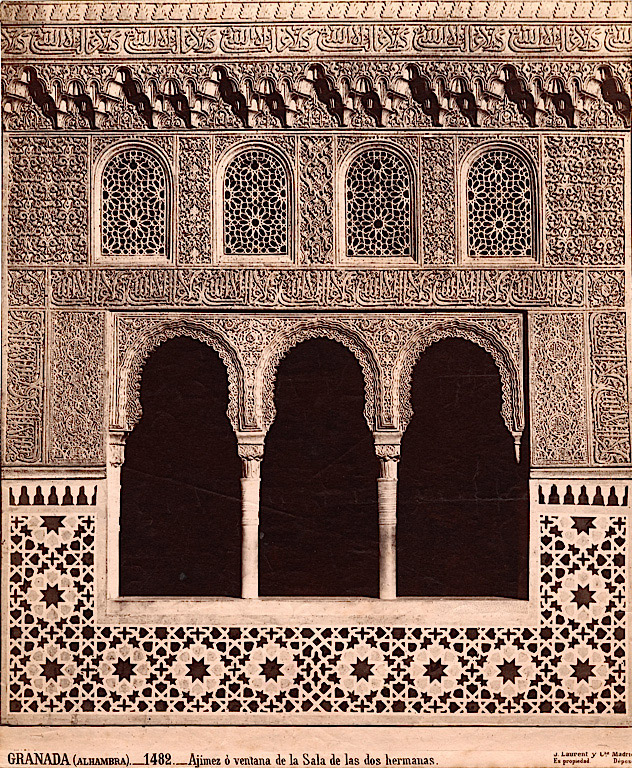

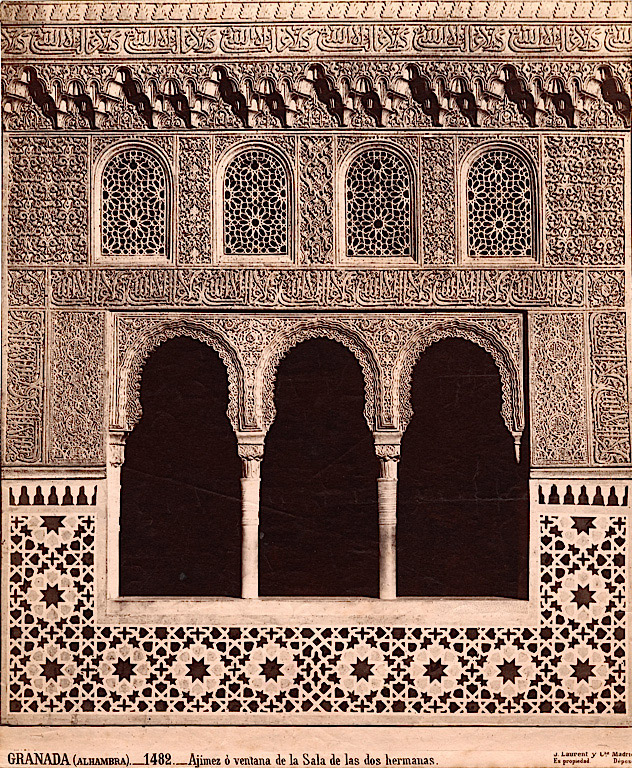

The architecture of the Nasrid palaces reflects the tradition of

Moorish architecture

Moorish architecture is a style within Islamic architecture which developed in the western Islamic world, including al-Andalus (on the Iberian peninsula) and what is now Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia (part of the Maghreb). The term "Moorish" com ...

developed over previous centuries. It is characterized by the use of the

courtyard

A courtyard or court is a circumscribed area, often surrounded by a building or complex, that is open to the sky.

Courtyards are common elements in both Western and Eastern building patterns and have been used by both ancient and contemporary ...

as a central space and basic unit around which other halls and rooms were organized. Courtyards typically had water features at their center, such as a

reflective pool or a fountain. Decoration was focused on the inside of the building and was executed primarily with

tile mosaics on lower walls and carved

stucco

Stucco or render is a construction material made of aggregates, a binder, and water. Stucco is applied wet and hardens to a very dense solid. It is used as a decorative coating for walls and ceilings, exterior walls, and as a sculptural and a ...

on the upper walls.

Geometric patterns

A pattern is a regularity in the world, in human-made design, or in abstract ideas. As such, the elements of a pattern repeat in a predictable manner. A geometric pattern is a kind of pattern formed of geometric shapes and typically repeated l ...

,

vegetal motifs, and

Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

inscriptions were the main types of decorative motifs. Additionally, "stalactite"-like sculpting, known as ''

muqarnas

Muqarnas ( ar, مقرنص; fa, مقرنس), also known in Iranian architecture as Ahoopāy ( fa, آهوپای) and in Iberian architecture as Mocárabe, is a form of ornamented vaulting in Islamic architecture. It is the archetypal form of I ...

'', was used for three-dimensional features like

vaulted

In architecture, a vault (French ''voûte'', from Italian ''volta'') is a self-supporting arched form, usually of stone or brick, serving to cover a space with a ceiling or roof. As in building an arch, a temporary support is needed while ring ...

ceilings.

Etymology

''Alhambra'' derives from the Arabic '' (f.)'', meaning "the red one", the complete form of which was ' "the red fortress (

qalat)".

The "Al-" in "Alhambra" means "the" in Arabic, but this is ignored in general usage in both English and Spanish, where the name is normally given the definite article. The reference to the colour "red" in the name is due to the reddish colour of its walls, which were constructed of

rammed earth

Rammed earth is a technique for constructing foundations, floors, and walls using compacted natural raw materials such as earth, chalk, lime, or gravel. It is an ancient method that has been revived recently as a sustainable building method.

...

. The reddish colour comes from the

iron oxide

Iron oxides are chemical compounds composed of iron and oxygen. Several iron oxides are recognized. All are black magnetic solids. Often they are non-stoichiometric. Oxyhydroxides are a related class of compounds, perhaps the best known of whic ...

in the local

clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4).

Clays develop plasticity when wet, due to a molecular film of water surrounding the clay par ...

used for this type of construction.

History

Origins and early history

The evidence for a Roman presence is unclear but archeologists have found remains of ancient foundations on the Sabika hill. A fortress or citadel, probably dating from the Visigothic period, existed on the hill in the 9th century.

The first reference to the ''Qal‘at al-Ḥamra'' was during the battles between the Arabs and the

Muladies during the rule of

‘Abdallah ibn Muhammad (r. 888–912). According to surviving documents from the era, the red castle was quite small, and its walls were not capable of deterring an army intent on conquering. The first reference to ' came in lines of poetry attached to an arrow shot over the ramparts, recorded by

Ibn Hayyan

Abū Marwān Ḥayyān ibn Khalaf ibn Ḥusayn ibn Ḥayyān al-Qurṭubī () (987–1075), usually known as Ibn Hayyan, was a Muslim historian from Al-Andalus.

Born at Córdoba, his father was an important official at the court of the Andalusi ...

(d. 1076):

"Deserted and roofless are the houses of our enemies;

Invaded by the autumnal rains, traversed by impetuous winds;

Let them within the red castle (Kalat al hamra) hold their mischievous councils;

Perdition and woe surround them on every side."

At the beginning of the 11th century, the region of Granada was dominated by the Zirids, a

Sanhaja

The Sanhaja ( ber, Aẓnag, pl. Iẓnagen, and also Aẓnaj, pl. Iẓnajen; ar, صنهاجة, ''Ṣanhaja'' or زناگة ''Znaga'') were once one of the largest Berber tribal confederations, along with the Zanata and Masmuda confederations. Ma ...

Berber group and offshoot of the

Zirids

The Zirid dynasty ( ar, الزيريون, translit=az-zīriyyūn), Banu Ziri ( ar, بنو زيري, translit=banū zīrī), or the Zirid state ( ar, الدولة الزيرية, translit=ad-dawla az-zīriyya) was a Sanhaja Berber dynasty from ...

who ruled parts of

North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

. When the

Caliphate of Córdoba

The Caliphate of Córdoba ( ar, خلافة قرطبة; transliterated ''Khilāfat Qurṭuba''), also known as the Cordoban Caliphate was an Islamic state ruled by the Umayyad dynasty from 929 to 1031. Its territory comprised Iberia and parts o ...

collapsed after 1009 and the

Fitna (civil war) began, the Zirid leader

Zawi ben Ziri

Zawi ibn Ziri as-Sanhaji or Al-Mansur Zawi ibn Ziri ibn Manad as-Sanhaji ( ar, المنصور زاوي بن زيري بن مناد الصنهاجي), was a chief in the Berber Sanhaja tribe. He arrived in Spain in 1000 (391) during the reign of A ...

established an independent kingdom for himself, the

Taifa of Granada

The Taifa of Granada ( ar, طائفة غرناطة, rtl=yes, , es, Taifa de Granada) or Zirid Kingdom of Granada was a Berber Muslim kingdom which was formed in al-Andalus in 1013, following the deposition of Caliph Hisham II in 1009. The king ...

.

The Zirids built their citadel and palace, known as the ''al-Qaṣaba al-Qadīma'' ("Old Citadel" or "Old Palace"), on the hill now occupied by the

Albaicín

The Albaicín (), also known as Albayzín (from ar, ٱلْبَيّازِينْ, translit=al-Bayyāzīn), is a district of Granada, in the autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. It is centered around a hill on the north side of the Darro Rive ...

neighborhood.

It was connected to two other fortresses on the Sabika and Mauror hills to the south.

On the

Darro River

The Darro is a river of the province of Granada, Spain. It is a tributary of the Genil. The river was originally named after the Roman word for gold (aurus) because people used to pan for gold on its banks. This name was then changed by the Arab ...

, between the Zirid citadel and the Sabika hill, was a

sluice gate

Sluice ( ) is a word for a channel controlled at its head by a movable gate which is called a sluice gate. A sluice gate is traditionally a wood or metal barrier sliding in grooves that are set in the sides of the waterway and can be considered ...

called ''Bāb al-Difāf'' ("Gate of the Tambourines"), which could be closed to retain water if needed. This gate was part of the fortification connecting the Zirid citadel with the fortress on the Sabika hill and it also formed part of a ''coracha'' (from Arabic ''qawraja''), a type of fortification allowing soldiers from the fortress to access the river and bring back water even during times of siege. The Sabika hill fortress, also known as ''al-Qasaba al-Jadida'' ("the New Citadel"), was later used for the foundations of the current

Alcazaba of the Alhambra.

Under the Zirid kings

Habbus ibn Maksan and

Badis, the most powerful figure in the kingdom was the

Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

administrator known as

Samuel ha-Nagid

Samuel ibn Naghrillah (, ''Sh'muel HaLevi ben Yosef HaNagid''; ''ʾAbū ʾIsḥāq ʾIsmāʿīl bin an-Naghrīlah''), also known as Samuel HaNagid (, ''Shmuel HaNagid'', lit. ''Samuel the Prince'') and Isma’il ibn Naghrilla (born 993; died 1056 ...

(in

Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

) or Isma'il ibn Nagrilla (in

Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

).

Samuel built his own palace on the Sabika hill, possibly on the site of the current palaces, although nothing remains of it. It reportedly included gardens and water features.

Nasrid period

The period of the

Taifa kingdoms

The ''taifas'' (singular ''taifa'', from ar, طائفة ''ṭā'ifa'', plural طوائف ''ṭawā'if'', a party, band or faction) were the independent Muslim principalities and kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula (modern Portugal and Spain), re ...

, during which the Zirids ruled, came to an end with the conquest of

al-Andalus

Al-Andalus DIN 31635, translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label=Berber languages, Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, ...

by the

Almoravids

The Almoravid dynasty ( ar, المرابطون, translit=Al-Murābiṭūn, lit=those from the ribats) was an imperial Berber Muslim dynasty centered in the territory of present-day Morocco. It established an empire in the 11th century that ...

from North Africa during the late 11th century. In the mid-12th century they were followed by the

Almohads

The Almohad Caliphate (; ar, خِلَافَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِينَ or or from ar, ٱلْمُوَحِّدُونَ, translit=al-Muwaḥḥidūn, lit=those who profess the unity of God) was a North African Berber Muslim empire fo ...

. After 1228 Almohad rule collapsed and local rulers and factions emerged again across the territory of Al-Andalus. With the ''

Reconquista

The ' (Spanish, Portuguese and Galician for "reconquest") is a historiographical construction describing the 781-year period in the history of the Iberian Peninsula between the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in 711 and the fall of the Nasrid ...

'' in full swing, the Christian kingdoms of

Castile and

Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to sou ...

– under kings

Ferdinand III and

James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

, respectively – made major conquests across al-Andalus. Castile captured

Cordoba in 1236 and

Seville in 1248. Meanwhile,

Ibn al-Ahmar (Muhammad I) established what became the last and longest reigning

Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

dynasty in the Iberian peninsula, the

Nasrids, who ruled the

Emirate of Granada

)

, common_languages = Official language: Classical ArabicOther languages: Andalusi Arabic, Mozarabic, Berber, Ladino

, capital = Granada

, religion = Majority religion: Sunni IslamMinority religions: Ro ...

.

Ibn al-Ahmar was a relatively new political player in the region and likely came from a modest background, but he was able to win the support and consent of multiple Muslim settlements under threat from the Castilian advance. Upon settling in Granada in 1238, Ibn al-Ahmar initially resided in the old citadel of the Zirids on the Albaicin hill, but that same year he began construction of the Alhambra as a new residence and citadel.

According to an Arabic manuscript since published as the ''Anónimo de Madrid y Copenhague'',

During the reign of the Nasrid Dynasty, the Alhambra was transformed into a palatine city, complete with an irrigation system composed of

aqueducts

Aqueduct may refer to:

Structures

*Aqueduct (bridge), a bridge to convey water over an obstacle, such as a ravine or valley

*Navigable aqueduct, or water bridge, a structure to carry navigable waterway canals over other rivers, valleys, railw ...

and water channels that provided water for the complex and for other nearby countryside palaces such as the

Generalife

The Generalife (; ar, جَنَّة الْعَرِيف, translit=Jannat al-‘Arīf) was a summer palace and country estate of the Nasrid rulers of the Emirate of Granada in Al-Andalus. It is located directly east of and uphill from the Alham ...

.

Previously, the old fortresses on the hill had been dependent on rainwater collected from the cistern near the Alcazaba and on what could be brought up from the Darro River below.

The creation of the Sultan's Canal (), which brought water from the mountains to the east, solidified the identity of the Alhambra as a palace-city rather than a defensive and

ascetic

Asceticism (; from the el, ἄσκησις, áskesis, exercise', 'training) is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from sensual pleasures, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their p ...

structure. This first hydraulic system was expanded afterwards and included two long water channels and several sophisticated elevation devices to bring water onto the plateau.

Later Nasrid rulers after Ibn al-Ahmar continuously modified the site. Along with the fragile materials themselves, which needed regular repairs, this makes the exact chronology of its development difficult to determine. The only elements preserved from the time of Ibn al-Ahmar are some of the fortification walls, particularly the Alcazaba at the western end of the complex. Ibn al-Ahmar did not have time to complete any major new palaces and he may have initially lived in one of the towers of the Alcazaba, before later moving to a modest house on the site of the current

Palace of Charles V

The Palace of Charles V is a Renaissance building in Granada, southern Spain, inside the Alhambra, a former Nasrid palace complex on top of the Sabika hill. Construction began in 1527 but dragged on and was left unfinished after 1637. The building ...

. The oldest major palace for which some remains have been preserved is the structure known as the ''

Palacio del Partal Alto

The ''Palacio del Partal Alto'' ("Upper Partal Palace" in Spanish), also known as the ''Palacio de Yusuf III'' ("Palace of Yusuf III") or the ''Palacio del Conde del Tendilla'' ("Palace of the Count of Tendilla"), is a former palace in the Alham ...

'', in an elevated location near the center of the complex, which probably dates from the reign of Ibn al-Ahmar's son,

Muhammad II (r. 1273–1302).' To the south was the Palace of the Abencerrajes, and to the east was another private palace, known as the

Palace of the Convent of San Francisco

The Palace of the Convent of San Francisco () or Palace of the ex-Convent of San Francisco () is a former medieval Nasrid palace in the Alhambra of Granada, Spain, which was transformed into a Franciscan convent after the Spanish conquest of Gra ...

'','' both of which were probably also originally constructed during the time of Muhammad II''.''

Muhammad III (r. 1302–1309) erected the

Partal Palace

Partal Palace () is a palatial structure inside the Alhambra fortress complex located in Granada, Spain. It was originally built in the early 14th century by the Nasrid ruler Muhammad III, making it the oldest surviving palatial structure in ...

, parts of which are still standing today, as well as the Alhambra's main (

congregational

Congregational churches (also Congregationalist churches or Congregationalism) are Protestant churches in the Calvinist tradition practising congregationalist church governance, in which each congregation independently and autonomously runs its ...

) mosque (on the site of the current Church of Santa Maria de la Alhambra).' The Partal Palace is the earliest known palace to be built along the northern walls of the complex, with views onto the city below.' It is also the oldest Nasrid palace still standing today.

Isma'il I

Ismail I ( fa, اسماعیل, Esmāʿīl, ; July 17, 1487 – May 23, 1524), also known as Shah Ismail (), was the founder of the Safavid dynasty of Iran, ruling as its King of Kings (''Shahanshah'') from 1501 to 1524. His reign is often ...

(r. 1314–1325) undertook a significant remodeling of the Alhambra. His reign marked the beginning of the "classical" period of Nasrid architecture, during which many major monuments in the Alhambra were begun and decorative styles were consolidated.

Isma'il decided to build a new palace complex just east of the Alcazaba to serve as the official palace of the sultan and the state, known as the ''Qaṣr al-Sultan'' or ''Dār al-Mulk''. The core of this complex was the

Comares Palace, while another wing of the palace, the

Mexuar

The Mexuar (; ) is a section of the Nasrid palace complex in the Alhambra of Granada, Spain. It served as the entrance wing of the Comares Palace, the official palace of the sultan and the state, and it housed various administrative functions. Af ...

, extended to the west. The Comares Baths are the best-preserved element from this initial construction, as the rest of the palace was further modified by his successors. Near the main mosque Isma'il I also created the ''Rawda'', the dynastic mausoleum of the Nasrids, of which only partial remains are preserved.'

Yusuf I

Abu al-Hajjaj Yusuf ibn Ismail ( ar, أبو الحجاج يوسف بن إسماعيل; 29 June 131819 October 1354), known by the regnal name al-Muayyad billah (, "He who is aided by God"), was the seventh Nasrid ruler of the Emirate of Gran ...

(r. 1333–1354) carried out further work on the Comares Palace, including the construction of the Hall of Ambassadors and other works around the current Mexuar. He also built the Alhambra's main gate, the ''Puerta de la Justicia'', and the ''

Torre de la Cautiva

The Torre de la Cautiva () is a tower in the walls of the Alhambra in Granada, Spain. It is one of several towers along the Alhambra's northern wall which were converted into a small palatial residence in the 14th century. It is considered an ex ...

'', one of several small towers with richly-decorated rooms along the northern walls.'

Muhammad V's reign (1354–1391, with interruptions) marked the political and cultural apogee of the Nasrid emirate as well as the apogee of Nasrid architecture. Particularly during his second reign (after 1362), there was a stylistic shift towards more innovative architectural layouts and an extensive use of complex ''

muqarnas

Muqarnas ( ar, مقرنص; fa, مقرنس), also known in Iranian architecture as Ahoopāy ( fa, آهوپای) and in Iberian architecture as Mocárabe, is a form of ornamented vaulting in Islamic architecture. It is the archetypal form of I ...

'' vaulting. His most significant contribution to the Alhambra was the construction of the

Palace of the Lions to the east of the Comares Palace in an area previously occupied by gardens. He also remodeled the Mexuar, created the highly-decorated "Comares Façade" in the ''Patio del Cuarto Dorado'', and redecorated the Court of the Myrtles, giving these areas much of their final appearance.' After Muhammad V, relatively little major construction work occurred in the Alhambra. One exception is the ''Torre de las Infantas'', which dates from the time of

Muhammad VII (1392–1408).' The 15th century saw the Nasrid dynasty in decline and in turmoil, with few significant construction projects and a more repetitive, less innovative style of architecture.'

''Reconquista'' and Christian Spanish period

The last Nasrid sultan,

Muhammad XII of Granada

Abu Abdallah Muhammad XII ( ar, أبو عبد الله محمد الثاني عشر, Abū ʿAbdi-llāh Muḥammad ath-thānī ʿashar) (c. 1460–1533), known in Europe as Boabdil (a Spanish rendering of the name ''Abu Abdallah''), was the ...

, surrendered the Emirate of Granada in January 1492, without the Alhambra itself being attacked, when the forces of the

Catholic Monarchs

The Catholic Monarchs were Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon, whose marriage and joint rule marked the ''de facto'' unification of Spain. They were both from the House of Trastámara and were second cousins, being bot ...

, King

Ferdinand II of Aragon

Ferdinand II ( an, Ferrando; ca, Ferran; eu, Errando; it, Ferdinando; la, Ferdinandus; es, Fernando; 10 March 1452 – 23 January 1516), also called Ferdinand the Catholic (Spanish: ''el Católico''), was King of Aragon and Sardinia from ...

and Queen

Isabella I of Castile

Isabella I ( es, Isabel I; 22 April 1451 – 26 November 1504), also called Isabella the Catholic (Spanish: ''la Católica''), was Queen of Castile from 1474 until her death in 1504, as well as List of Aragonese royal consorts, Queen consort ...

, took the surrounding territory with a force of overwhelming numbers. Muhammad XII moved the remains of his ancestors from the complex, as was verified by

Leopoldo Torres Balbás Leopoldo Torres Balbás (23 May 1888, in Madrid – 21 November 1960, in Madrid) was a Spanish scholar, architect, and restorer. He was an important figure in the early 20th century conservation and restoration of monuments. Much of his work focused ...

in 1925, when he found seventy empty tombs. The remains are now likely to be located in Mondújar in the principality of

Lecrín.

After the conquest, the Alhambra became a royal palace and property of the

Spanish Crown

, coatofarms = File:Coat_of_Arms_of_Spanish_Monarch.svg

, coatofarms_article = Coat of arms of the King of Spain

, image = Felipe_VI_in_2020_(cropped).jpg

, incumbent = Felipe VI

, incumbentsince = 19 Ju ...

. Isabella and Ferdinand initially took up residence here and stayed in Granada for several months, up until 25 May 1492. It was during this stay that two major events happened. On 31 March the monarchs signed the

Alhambra Decree

The Alhambra Decree (also known as the Edict of Expulsion; Spanish: ''Decreto de la Alhambra'', ''Edicto de Granada'') was an edict issued on 31 March 1492, by the joint Catholic Monarchs of Spain ( Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Arag ...

, which ordered the

expulsion of all Jews in Spain who refused to convert.

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

, who had also been present to witness the surrender of Granada, presented his plans for an

expedition across the Atlantic to the monarchs in the Hall of Ambassadors and on 17 April they signed the contract which set the terms for the expedition which landed in the

Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

later that year.

The new Christian rulers began to make additions and alterations to the palace complex. The governorship of the Alhambra was entrusted to the Tendilla family, who were given one of the Nasrid palaces, the ''Palacio del Partal Alto'' (near the Partal Palace), to use as family residence.

Iñigo López de Mendoza y Quiñones (d. 1515), the second

Count

Count (feminine: countess) is a historical title of nobility in certain European countries, varying in relative status, generally of middling rank in the hierarchy of nobility. Pine, L. G. ''Titles: How the King Became His Majesty''. New York: ...

of

Tendilla

Tendilla is a municipality located in the province of Guadalajara, Castile-La Mancha, Spain. According to the 2004 census (INE

INE, Ine or ine may refer to:

Institutions

* Institut für Nukleare Entsorgung, a German nuclear research center

* ...

, was present in Ferdinand II's entourage when Muhammad XII surrendered the keys to the Alhambra and he became the Alhambra's first Spanish governor. For almost 24 years after the conquest he made repairs and modifications to its fortifications in order to better protect it against

gunpowder artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during sieges, ...

attacks. Multiple towers and fortifications – such as the ''Torre de Siete Suelos'', the ''Torre de las Cabezas'', and the ''Torres Bermejas'' – were built or reinforced in this period, as seen by the addition of semi-round

bastions. In 1512 the Count was also awarded the property of

Mondéjar and subsequently passed on the title of

Marquis

A marquess (; french: marquis ), es, marqués, pt, marquês. is a nobleman of high hereditary rank in various European peerages and in those of some of their former colonies. The German language equivalent is Markgraf (margrave). A woman wi ...

of Mondéjar to his descendants.

Charles V Charles V may refer to:

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

* Charles V, Duke of Lorraine (1643–1690)

* Infan ...

(r. 1516–1556) visited the Alhambra in 1526 with his wife

Isabella of Portugal

Isabella of Portugal (24 October 1503 – 1 May 1539) was the empress consort and queen consort of her cousin Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, King of Spain, Archduke of Austria, and Duke of Burgundy. She was Queen of Spain and Germany, and La ...

and decided to convert it into a royal residence for his use. He rebuilt or modified portions of the Nasrid palaces to serve as royal apartments, a process which began in 1528 and was completed in 1537. He also demolished a part of the Comares Palace to make way for a monumental new palace, known the Palace of Charles V, designed in the

Renaissance style

Renaissance architecture is the European architecture of the period between the early 15th and early 16th centuries in different regions, demonstrating a conscious revival and development of certain elements of ancient Greek and Roman thought a ...

of the period. Construction of the palace began in 1527 but it was eventually left unfinished after 1637.

The governorship of the Tendilla-Mondéjar family came to an end in 1717–1718, when

Philip V Philip V may refer to:

* Philip V of Macedon (221–179 BC)

* Philip V of France (1293–1322)

* Philip II of Spain, also Philip V, Duke of Burgundy (1526–1598)

* Philip V of Spain

Philip V ( es, Felipe; 19 December 1683 – 9 July 1746) was ...

confiscated the family's properties in the Alhambra and dismissed the Marquis of Mondéjar, José de Mendoza Ibáñez de Segovia (1657–1734), from his position as mayor (''alcaide'') of the Alhambra, in retaliation for the Marquis opposing him in the

War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phil ...

. The departure of the Tendilla-Mondéjar family marked the beginning of the Alhambra's most severe period of decline. During this period the Spanish state dedicated few resources to it and its management was taken over by self-interested local governors who lived with their families inside the neglected palaces.

Over subsequent years the Alhambra was further damaged. Between 1810 and 1812 Granada was occupied by

Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

's army during the

Peninsular War

The Peninsular War (1807–1814) was the military conflict fought in the Iberian Peninsula by Spain, Portugal, and the United Kingdom against the invading and occupying forces of the First French Empire during the Napoleonic Wars. In Spain ...

. The French troops, under the command of

Count Sebastiani,

occupied the Alhambra as a fortified position and caused significant damage to the monument. Upon evacuating the city, they attempted to dynamite the whole complex to prevent it from being re-used as a fortified position. They successfully blew up eight towers before the remaining fuses were disabled by Spanish soldier José Garcia, whose actions saved what remains today. In 1821, an earthquake caused further damage.

Recovery and modern restorations

Restoration work was undertaken in 1828 by the architect José Contreras, endowed in 1830 by

Ferdinand VII

, house = Bourbon-Anjou

, father = Charles IV of Spain

, mother = Maria Luisa of Parma

, birth_date = 14 October 1784

, birth_place = El Escorial, Spain

, death_date =

, death_place = Madrid, Spain

, burial_plac ...

. After the death of Contreras in 1847, it was continued by his son Rafael (died 1890) and his grandson Mariano Contreras (died 1912).

In 1830

Washington Irving

Washington Irving (April 3, 1783 – November 28, 1859) was an American short-story writer, essayist, biographer, historian, and diplomat of the early 19th century. He is best known for his short stories "Rip Van Winkle" (1819) and " The Legen ...

lived in Granada and wrote his ''

Tales of the Alhambra

''Tales of the Alhambra'' (1832) is a collection of essays, verbal sketches and stories by American author Washington Irving (1783–1859) inspired by, and partly written during, his 1828 visit to the palace/fortress complex known as the Alhambr ...

'', first published in 1832, which spurred international interest in southern Spain and in its Islamic-era monuments like the Alhambra (an apartment of which he decorated in New England style). Other artists and intellectuals, such as

John Frederick Lewis

John Frederick Lewis (1804–1876) was an English Orientalist painter. He specialized in Oriental and Mediterranean scenes in detailed watercolour or oils, very often repeating the same composition in a version in each medium. He lived for ...

and

Owen Jones

Owen Jones (born 8 August 1984) is a British newspaper columnist, political commentator, journalist, author, and left-wing activist. He writes a column for ''The Guardian'' and contributes to the ''New Statesman'' and '' Tribune.'' He has two ...

, helped make the Alhambra into an icon of the era with their writings and illustrations during the 19th century.

The Contreras family members continued to be the most important architects and conservators of the Alhambra up until 1907. During this period they generally followed a theory of "stylistic restoration", which favoured the construction and addition of elements to make a monument "complete" but not necessarily corresponding to any historical reality. They added elements which they deemed to be representative of what they thought was an "Arabic style", emphasizing the Alhambra's purported "

Oriental

The Orient is a term for the East in relation to Europe, traditionally comprising anything belonging to the Eastern world. It is the antonym of ''Occident'', the Western World. In English, it is largely a metonym for, and coterminous with, the ...

" character. For example, in 1858–1859 Rafael Contreras and Juan Pugnaire added Persian-looking spherical domes to the Court of the Lions and to the northern

portico

A portico is a porch leading to the entrance of a building, or extended as a colonnade, with a roof structure over a walkway, supported by columns or enclosed by walls. This idea was widely used in ancient Greece and has influenced many cult ...

of the Court of the Myrtles, even though these had nothing to do with Nasrid architecture.

In 1868 a

revolution deposed Isabella II and the government seized the properties of the Spanish monarchy, including the Alhambra. In 1870 the Alhambra was declared a

National Monument

A national monument is a monument constructed in order to commemorate something of importance to national heritage, such as a country's founding, independence, war, or the life and death of a historical figure.

The term may also refer to a spec ...

of Spain and the state allocated a budget for its conservation, overseen by the Provincial Commission of Monuments. Mariano Contreras, the last of the Contreras architects to serve as director of conservation of the Alhambra, was appointed as architectural curator in April 1890. His tenure was controversial and his conservation strategy attracted criticism from other authorities.

In September 1890 a fire destroyed a large part of the ''Sala de la Barca'' in the Comares Palace, which highlighted the site's vulnerability.

A report was commissioned in 1903 which resulted in the creation of a "Special Commission" in 1905 whose task was to oversee conservation and restoration of the Alhambra, but the commission ultimately failed to exercise control due to friction with Contreras.

In 1907 Mariano Contreras was replaced with Modesto Cendoya, whose work was also criticized. Cendoya began many excavations in search of new artifacts but often left these works unfinished. He restored some important elements of the site, like the water supply system, but neglected others.

Due to continued friction with Cendoya, the Special Commission was dissolved in 1913 and replaced with the Council (''Patronato'') of the Alhambra in 1914, which was charged again with overseeing the site's conservation and Cendoya's work. In 1915 it was linked directly to the Directorate-General of Fine Arts of the Ministry of Public Education (later the Ministry of National Education).

Like Mariano Contreras before him, Cendoya continued to clash with the supervisory body and to obstruct their control. He was eventually dismissed from his post in 1923.

After Cendoya,

Leopoldo Torres Balbás Leopoldo Torres Balbás (23 May 1888, in Madrid – 21 November 1960, in Madrid) was a Spanish scholar, architect, and restorer. He was an important figure in the early 20th century conservation and restoration of monuments. Much of his work focused ...

was appointed as chief architect from 1923 to 1936. The appointment of Torres Balbás, a trained

archeologist

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts ...

and

art historian

Art history is the study of aesthetic objects and visual expression in historical and stylistic context. Traditionally, the discipline of art history emphasized painting, drawing, sculpture, architecture, ceramics and decorative arts; yet today ...

, marked a definitive shift to a more scientific and systematic approach to the Alhambra's conservation.

He endorsed the principles of the 1931

Athens Charter for the Restoration of Monuments, which emphasized regular maintenance, respect for the work of the past, legal protection for heritage monuments, and the legitimacy of modern techniques and materials in restoration so long as these were visually recognizable. Many of the buildings in the Alhambra were affected by his work. Some of the inaccurate changes and additions made by the Contreras architects were reversed. The young architect "opened arcades that had been walled up, re-excavated filled-in pools, replaced missing tiles, completed inscriptions that lacked portions of their stuccoed lettering, and installed a ceiling in the still unfinished palace of Charles V". He also carried out systematic archeological excavations in various parts of the Alhambra, unearthing lost Nasrid structures such as the ''Palacio del Partal Alto'' and the Palace of the Abencerrajes which provided deeper insight into the former palace-city as a whole.

The work of Torres Balbás was continued by his assistant, Francisco Prieto Moreno, who was the chief architectural curator from 1936 to 1970. In 1940 a new Council of the Alhambra was created to oversee the site, which has remained in charge ever since. In 1984 the central government in

Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

transferred responsibility for the site to the

Regional Government of Andalusia

The Regional Government of Andalusia ( es, Junta de Andalucía) is the government of the Autonomous Community of Andalusia. It consists of the Parliament, the President of the Regional Government and the Government Council. The 2011 budget was 31. ...

and in 1986 new statutes and documents were developed to regulate the planning and protection of the site. In 1984 the Alhambra and Generalife were also listed as a

UNESCO World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for h ...

.

The Alhambra is now one of the most popular tourist destinations in Spain. Research, archeological investigations, and restoration works have also remained ongoing into the 21st century.

Layout

The Alhambra site is about in length and about at its greatest width.

It extends from west-northwest to east-southeast and covers an area of about or 35 acres.

It stands on a narrow promontory overlooking the ''Vega'' or Plain of Granada and carved by the river

Darro on its north side as it descends from the

Sierra Nevada

The Sierra Nevada () is a mountain range in the Western United States, between the Central Valley of California and the Great Basin. The vast majority of the range lies in the state of California, although the Carson Range spur lies primarily ...

. The red earth from which the fortress is constructed is a granular aggregate held together by a medium of red clay which gives the resulting layered brick- and stone- reinforced construction (''tapial calicastrado'') its characteristic hue and is at the root of the name of 'the Red Hill'.

The Alhambra's most westerly feature is the Alcazaba, a large fortress overlooking the city. Due to touristic demand, modern access runs contrary to the original sequence which began from a principal access via the ''Puerta de la Justicia'' (Gate of Justice) onto a large

souq or public market square facing the Alcazaba, now subdivided and obscured by later Christian-era development.

From the ''Puerta del Vino'' (Wine Gate) ran the ''Calle Real'' (Royal Street) dividing the Alhambra along its axial spine into a southern residential quarter, with

mosque

A mosque (; from ar, مَسْجِد, masjid, ; literally "place of ritual prostration"), also called masjid, is a place of prayer for Muslims. Mosques are usually covered buildings, but can be any place where prayers ( sujud) are performed, ...

s,

hamams (bathhouses) and diverse functional establishments,

and a greater northern portion, occupied by several palaces of the nobility with extensive landscaped gardens commanding views over the Albaicín. All of this was subservient to the great Tower of the Ambassadors in the ''Palacio Comares'' (Comares Palace), which acted as the royal audience chamber and throne room with its three arched windows dominating the city. The private, internalised universe of the ''Palacio de Los Leones'' (Palace of the Lions) adjoins the public spaces at right angles (see Plan illustration) but was originally connected only by the function of the Comares Baths (or Royal Baths), the ''Mirador de Lindaraja'' serving as the exquisitely decorated focus of meditation and authority overlooking the refined garden courtyard of ''Lindaraja/Daraxa'' toward the city.

The rest of the plateau comprises a number of earlier and later Moorish palaces, enclosed by a

fortified wall

A defensive wall is a fortification usually used to protect a city, town or other settlement from potential aggressors. The walls can range from simple palisades or earthworks to extensive military fortifications with towers, bastions and gates ...

, with thirteen defensive towers, some such as the ''Torre de la Infanta'' and ''Torre de la'' ''Cautiva'' containing elaborate vertical palaces in miniature.

The river Darro passes through a ravine on the north and divides the plateau from the Albaicín district of Granada. Similarly, the Sabika Valley, containing the Alhambra Park, lies on the west and south, and, beyond this valley, the almost parallel ridge of Monte Mauror separates it from the Antequeruela district. Another ravine separates it from the Generalife, the summer pleasure gardens of the emir. Salmerón Escobar notes that the later planting of deciduous elms obscures the overall perception of the layout, so a better reading of the original landscape is given in winter when the trees are bare.

Architecture

General design

The design and decoration of the Nasrid palaces are a continuation of

Moorish (western Islamic) architecture from earlier centuries but developed their own characteristics. The combination of carefully-proportioned courtyards, water features, gardens, arches on slender columns, and intricately-sculpted

stucco

Stucco or render is a construction material made of aggregates, a binder, and water. Stucco is applied wet and hardens to a very dense solid. It is used as a decorative coating for walls and ceilings, exterior walls, and as a sculptural and a ...

and

tile

Tiles are usually thin, square or rectangular coverings manufactured from hard-wearing material such as ceramic, stone, metal, baked clay, or even glass. They are generally fixed in place in an array to cover roofs, floors, walls, edges, or o ...

decoration gives Nasrid architecture qualities that are described as ethereal and intimate.

Walls were built mostly in

rammed earth

Rammed earth is a technique for constructing foundations, floors, and walls using compacted natural raw materials such as earth, chalk, lime, or gravel. It is an ancient method that has been revived recently as a sustainable building method.

...

,

lime concrete, or

brick

A brick is a type of block used to build walls, pavements and other elements in masonry construction. Properly, the term ''brick'' denotes a block composed of dried clay, but is now also used informally to denote other chemically cured cons ...

and then covered with

plaster

Plaster is a building material used for the protective or decorative coating of walls and ceilings and for Molding (decorative), moulding and casting decorative elements. In English, "plaster" usually means a material used for the interiors of ...

, while wood (mostly

pine

A pine is any conifer tree or shrub in the genus ''Pinus'' () of the family Pinaceae. ''Pinus'' is the sole genus in the subfamily Pinoideae. The World Flora Online created by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and Missouri Botanical Garden accep ...

) was used for roofs, ceilings, doors, and window shutters.

Buildings were designed to be seen from within, with their decoration focused on the inside. The basic unit of Nasrid palace architecture was a rectangular

courtyard

A courtyard or court is a circumscribed area, often surrounded by a building or complex, that is open to the sky.

Courtyards are common elements in both Western and Eastern building patterns and have been used by both ancient and contemporary ...

with a pool, fountain, or water channel at its center. Courtyards were flanked on two or four sides by halls, often preceded by

arcaded porticoes. Many of these structures featured a ''

mirador'', a room projecting from the exterior commanding scenic views of gardens or of the city.

Buildings were designed with a mathematical proportional system that gives them a harmonious visual quality. The layout of the courtyards, the distribution of windows, and the use of water features were designed with the climate in mind, cooling and ventilating the environment in summer while minimizing cold drafts and maximizing sunlight in winter. Upper-floor rooms were smaller and more enclosed, making them more suited for use during the winter. Courtyards were usually aligned in a north-south direction which allows the main halls to receive direct sunlight at midday during the winter, while during the summer the higher midday sun is blocked by the position and depth of the porticos fronting these halls.

Architects and poets

Little is known about the architects and craftsmen who built the Alhambra, but more is known about the ''Dīwān al-Ins͟hā, or

chancery. This institution seems to have played an increasingly important role in the design of buildings, probably because inscriptions came to feature so prominently in their decoration. The head of the chancery was often also the

vizier

A vizier (; ar, وزير, wazīr; fa, وزیر, vazīr), or wazir, is a high-ranking political advisor or minister in the near east. The Abbasid caliphs gave the title ''wazir'' to a minister formerly called ''katib'' (secretary), who was a ...

(prime minister) of the sultan. Although not exactly architects, the terms of office of many individuals in these positions coincide with the major phases of construction in the Alhambra, which suggests that they played a role in leading construction projects. The most important figures who held these positions, such as

Ibn al-Jayyab Ibn al-Jayyāb al-Gharnāṭī (); Abū al-Ḥasan ‘Alī b. Muḥammad b. Suleiman b. ‘Alī b. Suleiman b. Ḥassān al-Anṣārī al-Gharnāṭī (); Spanish var., Ibn al-Ŷayyab, (1274–1349 AD/673–749 AH); he was an Andalusian wri ...

,

Ibn al-Khatib

Lisan ad-Din Ibn al-Khatib ( ar, لسان الدين ابن الخطيب, Lisān ad-Dīn Ibn al-Khaṭīb) (Born 16 November 1313, Loja– died 1374, Fes; full name in ar, محمد بن عبد الله بن سعيد بن عبد الله بن � ...

, and

Ibn Zamrak

Ibn Zamrak () (also Zumruk) or Abu Abduallah Muhammad ibn Yusuf ibn Muhammad ibn Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Yusuf al-Surayhi, (1333–1393) was an Arab Andalusian poet and statesman from Granada, Al-Andalus. Some his poems still decorate the foun ...

, also composed much of the poetry that adorns the walls of the Alhambra. Ibn al-Jayyab served as head of the chancery at various times between 1295 and 1349 under six sultans from Muhammad II to Yusuf I. Ibn al-Khatib served as both head of the chancery and as vizier for various periods between 1332 and 1371, under the sultans Yusuf I and Muhammad V. Ibn Zamrak served as vizier and head of the chancery for periods between 1354 and 1393, under Muhammad V and Muhammad VII.

Decoration

Carved stucco (or ''yesería'' in Spanish) and mosaic tilework (

''zilīj'' or ''zellij'' in

Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

; ''alicatado'' in Spanish

) was used for wall decoration, while ceilings were generally made in wood, which could be carved and painted in turn. Tile mosaics and wooden ceilings often feature

geometric motifs. Tilework was generally used for lower walls or for floors, while stucco was used for upper zones. Stucco was typically carved with vegetal

arabesque

The arabesque is a form of artistic decoration consisting of "surface decorations based on rhythmic linear patterns of scrolling and interlacing foliage, tendrils" or plain lines, often combined with other elements. Another definition is "Foli ...

motifs (''ataurique'' in Spanish, from ), epigraphic motifs, geometric motifs, or ''

sebka

''Sebka'' () refers to a type of decorative motif used in western Islamic ("Moorish") architecture and Mudéjar architecture.

History and description

Various types of interlacing rhombus-like motifs are heavily featured on the surfaces of ...

'' motifs.

It could be further sculpted into three-dimensional ''muqarnas'' (''mocárabes'' in Spanish). Arabic inscriptions, a feature especially characteristic of the Alhambra, were carved along the walls and included

Qur'anic

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , sing.: ...

excerpts, poetry by Nasrid court poets, and the repetition of the Nasrid motto "''wa la ghalib illa-llah''" ().

White marble quarried from

Macael (in

Almeria province) was also used to make fountains and slender columns. The

capitals of columns typically consisted of a lower cylindrical section sculpted with stylized

acanthus leaves, an upper cubic section with vegetal or geometric motifs, and inscriptions (like the Nasrid motto) running along the base or the top edge.

While the stucco decoration, wooden ceilings, and marble capitals of the Alhambra often appear colourless or monochrome today, they were originally painted in bright colours.

Primary colours

A set of primary colors or primary colours (see spelling differences) consists of colorants or colored lights that can be mixed in varying amounts to produce a gamut of colors. This is the essential method used to create the perception of a b ...

– red, blue, and (in place of yellow) gold – were the most prominent and were juxtaposed to achieve a certain aesthetic balance, while other colours were used in more nuanced ways in the background.

Inscriptions

The Alhambra features various styles of the

Arabic epigraphy that developed under the Nasrid dynasty, and particularly under Yusuf I and Muhammad V.

compares the walls of the Alhambra to the pages of a manuscript, drawing similarities between the ''zilīj''-covered

dados and the geometric manuscript illuminations, and the epigraphical forms in the palace to calligraphic motifs in contemporary Arabic manuscripts.

Inscriptions typically ran in vertical or horizontal bands or they were set inside cartouches of round or rectangular shape.

Most major inscriptions in the Alhambra use the

''Naskhi'' or cursive script, which was the most common script used in writing after the early Islamic period. ''

Thuluth

''Thuluth'' ( ar, ثُلُث, ' or ar, خَطُّ الثُّلُثِ, '; fa, ثلث, ''Sols''; Turkish: ''Sülüs'', from ' "one-third") is a script variety of Islamic calligraphy. The straight angular forms of Kufic were replaced in the new s ...

'' was a derivation of the cursive script often used for more pompous or formal contexts; favoured, for example, in the preambles of documents prepared by the Nasrid chancery. Many inscriptions in the Alhambra were composed in a mixed ''Naskhi-Thuluth'' script.

Bands of cursive script often alternated with friezes or cartouches of Kufic script. Kufic is the oldest form of Arabic calligraphy, but by the 13th century Kufic scripts in the western Islamic world became increasingly stylized in architectural contexts and could be nearly illegible. In the Alhambra, there are many examples of "Knotted" Kufic, a particularly elaborate style where the letters tie together in intricate knots.

The extensions of these letters could turn into strips that continued and formed more abstract motifs, or sometimes formed the edges of a cartouche encompassing the rest of the inscription.

The texts of the Alhambra include "devout, regal, votive, and Qur'anic phrases and sentences," formed into arabesques, carved into wood and marble, and glazed onto tiles.

Poets of the Nasrid court, including Ibn al-Khatīb and Ibn Zamrak, composed poems for the palace.

The inscriptions of the Alhambra are also unique for their frequent self-referential nature and use of

personification

Personification occurs when a thing or abstraction is represented as a person, in literature or art, as a type of anthropomorphic metaphor. The type of personification discussed here excludes passing literary effects such as "Shadows hold their b ...

. Some inscribed poems, such as those in the Palace of the Lions, talk about the palace or room in which they're situated and are written in the first person, as if the room itself was speaking to the reader. Most of the poetry is inscribed in Nasrid cursive script, while foliate and floral Kufic inscriptions—often formed into arches, columns, enjambments, and "architectural calligrams"—are generally used as decorative elements.

Kufic

calligrams

A calligram is text arranged in such a way that it forms a thematically related image. It can be a poem, a phrase, a portion of scripture, or a single word; the visual arrangement can rely on certain use of the typeface, calligraphy or handwr ...

, particularly of the words "blessing" ( ''baraka'') and "felicity" ( ''yumn''), are used as decorative motifs in arabesque throughout the palace.

Like the rest of the original stucco decoration, many inscriptions were originally painted and enhanced with colours. Studies indicate that the letters were often painted in gold or silver, or in white with black outlines, which would have made them stand out on the decorated backgrounds that were often painted in red, blue, or turquoise (with other colours mixed into the details).

Main structures

Entrance gates

The main gate of the Alhambra is the ''Puerta de la Justicia'' (Gate of Justice), known in Arabic as ''Bab al-Shari'a'' (), a massive gate that served as the main entrance on the south side of the walled complex, built in 1348 during the reign of Yusuf I. The gate consists of a large horseshoe arch leading to a steep ramp passing through a

bent passage. The passage turns 90 degrees to the left and then 90 degrees to the right, with an opening above where defenders could throw projectiles onto any attackers below. The image of a hand, whose five fingers symbolized the

Five Pillars of Islam

The Five Pillars of Islam (' ; also ' "pillars of the religion") are fundamental practices in Islam, considered to be obligatory acts of worship for all Muslims. They are summarized in the famous hadith of Gabriel. The Sunni and Shia agree on ...

, is carved above this gate on the exterior, while the image of a key, another symbol of faith, is carved on the corresponding place on the inner side. A Christian-era sculpture of the

Virgin

Virginity is the state of a person who has never engaged in sexual intercourse. The term ''virgin'' originally only referred to sexually inexperienced women, but has evolved to encompass a range of definitions, as found in traditional, modern ...

and

Christ Child was inserted later into another niche just inside the gate. Near the outside of the gate is the ''Pilar de Carlos V'', a Renaissance-style fountain built in 1524 with some further alterations in 1624.

At the end of the passage coming from the ''Puerta de la Justicia'' is the ''Plaza de los Aljibes'' ('Place of the Cisterns'), a broad open space which divides the Alcazaba from the Nasrid Palaces. The plaza is named after a large cistern dating to around 1494, commissioned by Iñigo López de Mondoza y Quiñones. The cistern was one of the first works carried out in the Alhambra after the 1492 conquest and it filled what was previously a gully between the Alcazaba and the palaces. On the east side of the square is the ''Puerta del Vino'' (Wine Gate) which leads to Palace of Charles V and to the former residential neighbourhoods (the ''medina'') of the Alhambra. The gate's construction is attributed to the reign of Muhammad III, although the decoration dates from different periods. Both sides of the gate are embellished with ceramic decoration in the spandrels of the arches and stucco decoration above. On the western side of the gate is the carving of a key symbol like the one on the ''Puerta de la Justicia''.

The other main gate of the Alhambra was the ''Puerta de las Armas'' ('Gate of Arms'), located on the north side of the Alcazaba, from which a walled ramp leads towards the ''Plaza de los Aljibes'' and the Nasrid Palaces. This was originally the main access point to the complex for the regular residents of the city, since it was accessible from the Albaicín side, but after the Christian conquest the ''Puerta de la Justicia'' was favoured by Ferdinand and Isabella. The gate, one of the earliest structures built in the Alhambra in the 13th century, is one of the Alhambra structures that bears the most resemblance to the Almohad architectural tradition that preceded the Nasrids. The exterior façade of the gate is decorated with a polylobed moulding with glazed tiles inside a rectangular ''

alfiz The alfiz (, from Andalusi Arabic ''alḥíz'', from Standard Arabic ''alḥáyyiz'', meaning 'the container';Al ...

'' frame. Inside the gate's passage is a dome that is painted to simulate the appearance of red brick, a decorative feature characteristic of the Nasrid period.

Two other exterior gates existed, both located further east. On the north side is the ''Puerta del Arrabal'' ('Arrabal Gate'), which opens onto the ''Cuesta de los Chinos'' ('Slope of the Pebbles'), the ravine between the Alhambra and the Generalife. It was probably created under Muhammad II and served the first palaces of the Alhambra which were built in this area during his reign. It underwent numerous modifications in the later Christian era of the Alhambra. On the south side is the ''Puerta de los Siete Suelos'' ('Gate of Seven Floors'), which was almost entirely destroyed by the explosions set off by the departing French troops in 1812. The present gate was reconstructed in the 1970s with help of remaining fragments and of multiple old

engravings

Engraving is the practice of incising a design onto a hard, usually flat surface by cutting grooves into it with a burin. The result may be a decorated object in itself, as when silver, gold, steel, or glass are engraved, or may provide an in ...

that illustrate the former gate. The original gate was probably built in the mid-14th century and its original Arabic name was ''Bab al-Gudur''. It would have been the main entrance serving the ''medina'', the area occupied by industries and regular houses inside the Alhambra. It was also through here that the Catholic Monarchs first entered the Alhambra on January 2, 1492.

Alcazaba

The Alcazaba or citadel is the oldest part of the Alhambra today. It was the centerpiece of the complicated system of fortifications that protected the area. Its tallest tower, the high ''Torre del Homenaje'' ('Tower of Homage'), was the

keep

A keep (from the Middle English ''kype'') is a type of fortified tower built within castles during the Middle Ages by European nobility. Scholars have debated the scope of the word ''keep'', but usually consider it to refer to large towers in c ...

and military command post of the complex. It may have also been the first residence of Ibn al-Ahmar inside the Alhambra while the complex was being constructed. The westernmost tower, the high ''Torre de la Vela'', acted as a watch tower. The flag of Ferdinand and Isabella was first raised above it as a symbol of the Spanish conquest of Granada on 2 January 1492.

A bell was added on the tower soon afterward and for centuries it was rung at regular times every day and on special occasions. In 1843 the tower became part of the city's coat of arms. Inside the enclosure of the inner fortress was a residential district that housed the elite guards of the Alhambra. It contained urban amenities like a communal kitchen, a

hammam

A hammam ( ar, حمّام, translit=ḥammām, tr, hamam) or Turkish bath is a type of steam bath or a place of public bathing associated with the Islamic world. It is a prominent feature in the culture of the Muslim world and was inherited f ...

, and a water supply cistern, as well as multiple subterranean chambers which served as

dungeons

A dungeon is a room or cell in which prisoners are held, especially underground. Dungeons are generally associated with medieval castles, though their association with torture probably belongs more to the Renaissance period. An oubliette (from ...

and

silos.

Nasrid palaces

The royal palace complex consists of three main parts, from west to east: the Mexuar, the Comares Palace, and the Palace of the Lions. Collectively, these palaces are also known as the ''Casa Real Vieja'' ('Old Royal Palace'), to distinguish them from the newer palaces erected next to them during the Christian Spanish period.

Mexuar

The Mexuar is the westernmost part of the palace complex. It was analogous to the ''

mashwar''s (or ''mechouar''s) of royal palaces in North Africa. It was first built as part of the larger complex begun by Isma'il I which included the Comares Palace. It housed many of the administrative and more public functions of the palace, such as the chancery and the treasury. Its layout consisted of two consecutive courtyards followed by a main hall, all aligned along a central axis from west to east. Little remains of the two western courtyards of the Mexuar today, except for their foundations, a portico, and the water basin of a fountain. The main hall, known as the ''Sala del Mexuar'' or Council Hall, served as a throne hall where the sultan received and judged petitions. This area also granted access to the Comares Palace via the ''Cuarto Dorado'' section on the east side of the Council Hall. Multiple parts of the Mexuar were significantly modified in the post-''Reconquista'' period; notably, the ''Sala del Mexuar'' was converted into a Christian

chapel

A chapel is a Christian place of prayer and worship that is usually relatively small. The term has several meanings. Firstly, smaller spaces inside a church that have their own altar are often called chapels; the Lady chapel is a common ty ...

and additions were made to the ''Cuarto Dorado'' to convert it into a residence. Many of these additions were later removed during modern restorations in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Comares Palace

The Comares Palace was the core of a large palace complex begun by Isma'il I in the early 13th century and subsequently modified and refurbished by Yusuf I and Muhammad V over the course of the same century. This new palace complex served as the official palace of the sultan and the state, known in Arabic as the ''Qaṣr al-Sultan'' or ''Dār al-Mulk''. The Comares Palace was accessed from the west through the Mexuar. An internal façade, known as the Comares Façade, stands on the south side of the ''Patio de Cuarto Dorado'' ('Courtyard of the Gilded Room') at the east edge of the Mexuar. This highly-decorated symmetrical façade, with two doors, was the entrance to the palace and likely served in some ceremonial functions.

The Comares Palace itself is centered around the ''Patio de los Arrayanes'' ('Court of the Myrtles'), a courtyard measuring 23 to 23.5 metres wide and 36.6 metres long, with its long axis aligned roughly north-to-south. At the middle, aligned with the main axis of the court, is a wide

reflective pool. The pool measures 34 metres long and 7,10 meters wide. The myrtle bushes that are the court's namesake grow in hedges along either side of this pool. Two ornate porticos are situated at the north and south ends of the court, leading to further halls and rooms behind them. The court's decoration contained 11

''qasā'id'' by

Ibn Zamrak

Ibn Zamrak () (also Zumruk) or Abu Abduallah Muhammad ibn Yusuf ibn Muhammad ibn Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Yusuf al-Surayhi, (1333–1393) was an Arab Andalusian poet and statesman from Granada, Al-Andalus. Some his poems still decorate the foun ...

, 8 of which remain.

Annexed to the east side of the palace are the Comares Baths, a royal hammam that is exceptionally well-preserved.

On the north side of the Court of the Myrtles, inside the massive Comares Tower, is the ''Salón de los Embajadores'' ('Hall of the Ambassadors'), the largest room in the Alhambra. It is accessed by passing through the ''Sala de la Barca'', a wide rectangular hall behind the northern portico of the court. The Hall of the Ambassadors is a square chamber measuring 11.3 meters per side and rising to a height of 18.2 metres. This was the throne room or audience chamber of the sultan. The sultan's throne was placed opposite the entrance in front of a recessed double-arched window at the back of the hall. In addition to the extensive tile and stucco decoration of the walls, the interior culminates in a large domed ceiling. The ceiling is made of 8017 interlinked pieces of wood that form an abstract geometric representation of the

seven heavens. The hall and its tower project from the walls of the palace, with windows providing views in three directions. In this sense, it was an enlarged version of a ''mirador'', a room from which the palace's inhabitants could gaze outward to the surrounding landscape.

Palace of the Lions

The Palace of the Lions is one of the most famous palaces in

Islamic architecture

Islamic architecture comprises the architectural styles of buildings associated with Islam. It encompasses both secular and religious styles from the early history of Islam to the present day. The Islamic world encompasses a wide geographic ar ...