Autriche Hydro-de on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of

The first record showing the name Austria is from 996, where it is written as ''

The first record showing the name Austria is from 996, where it is written as ''

During the long reign of Leopold I (1657–1705) and following the successful defence of Vienna against the Turks in 1683 (under the command of the King of Poland,

During the long reign of Leopold I (1657–1705) and following the successful defence of Vienna against the Turks in 1683 (under the command of the King of Poland,

Austria later became engaged in a war with

Austria later became engaged in a war with  The various different possibilities for a united Germany were: a

The various different possibilities for a united Germany were: a  Many Austrians of all different social circles such as

Many Austrians of all different social circles such as

On 21 October 1918, the elected German members of the ''Reichsrat'' (parliament of Imperial Austria) met in Vienna as the Provisional National Assembly for German Austria (''Provisorische Nationalversammlung für Deutschösterreich''). On 30 October the assembly founded the

On 21 October 1918, the elected German members of the ''Reichsrat'' (parliament of Imperial Austria) met in Vienna as the Provisional National Assembly for German Austria (''Provisorische Nationalversammlung für Deutschösterreich''). On 30 October the assembly founded the

His successor

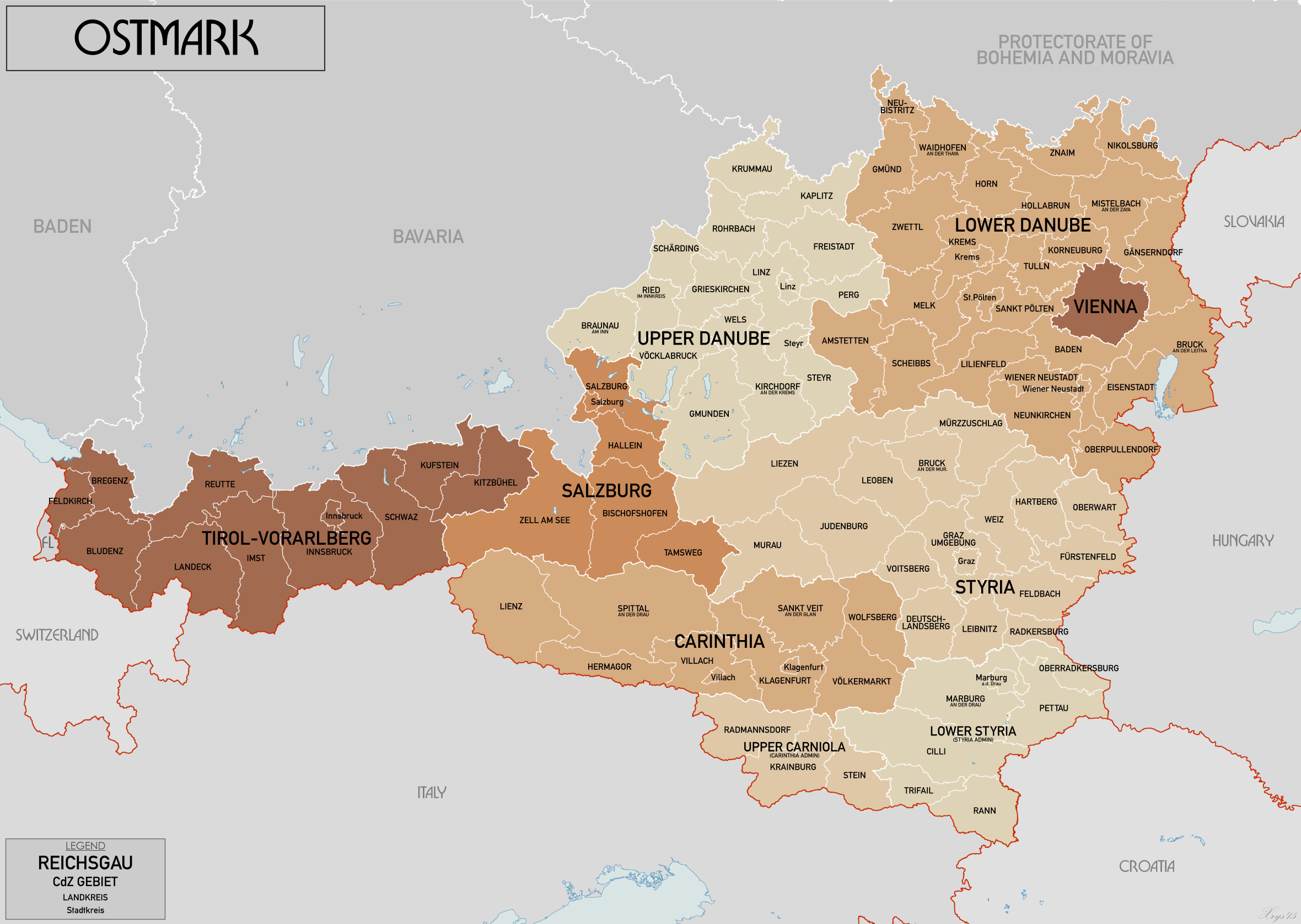

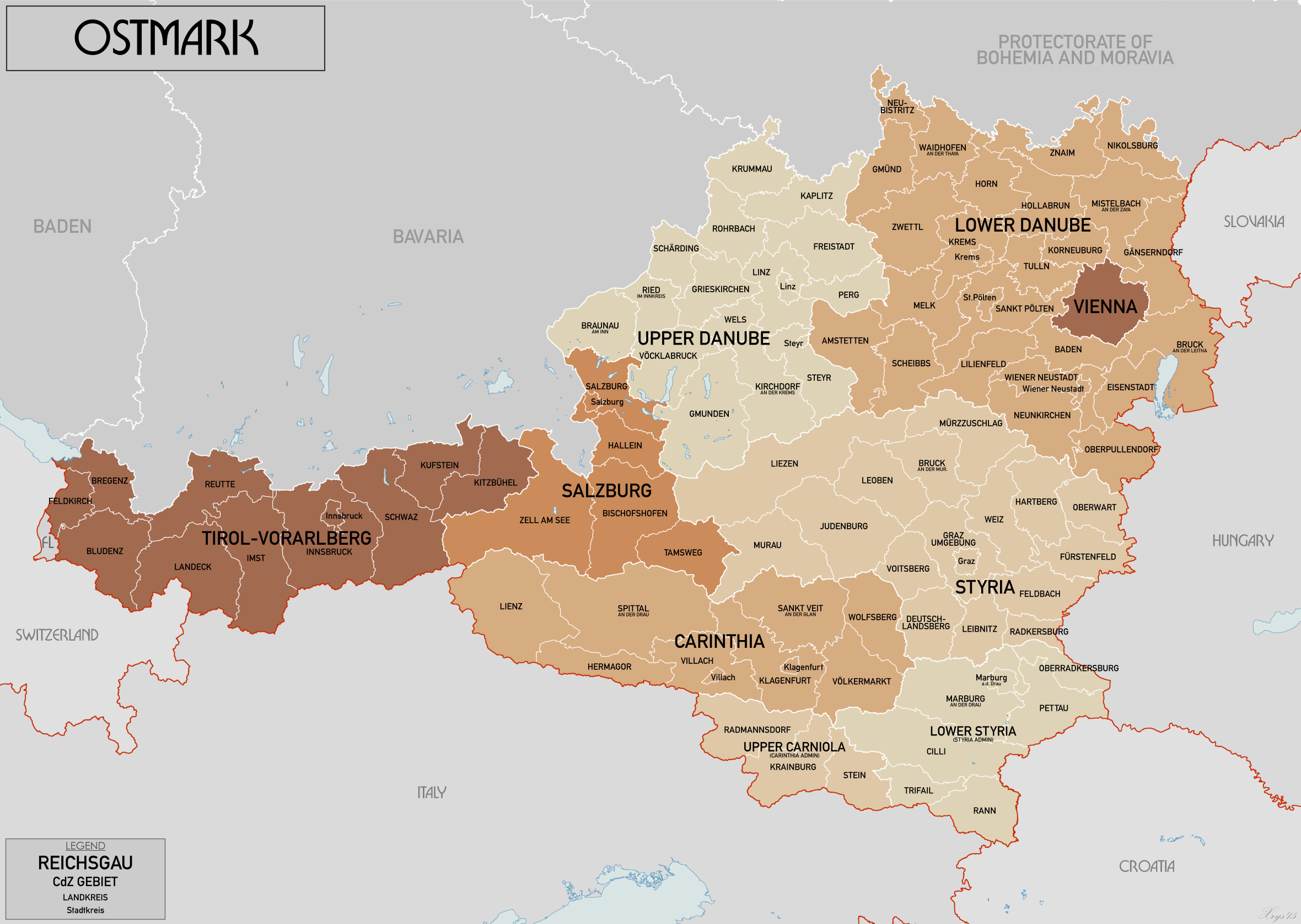

His successor  On 12 March 1938, Austria was annexed by the

On 12 March 1938, Austria was annexed by the

Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the area' ...

, lying in the Eastern Alps

Eastern Alps is the name given to the eastern half of the Alps, usually defined as the area east of a line from Lake Constance and the Alpine Rhine valley up to the Splügen Pass at the Alpine divide and down the Liro River to Lake Como in the ...

. It is a federation

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government (federalism). In a federation, the self-governin ...

of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, the most populous city and state. A landlocked country

A landlocked country is a country that does not have territory connected to an ocean or whose coastlines lie on endorheic basin, endorheic basins. There are currently 44 landlocked countries and 4 landlocked list of states with limited recogni ...

, Austria is bordered by Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

to the northwest, the Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, or simply Czechia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Historically known as Bohemia, it is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the southeast. The ...

to the north, Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the s ...

to the northeast, Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

to the east, Slovenia

Slovenia ( ; sl, Slovenija ), officially the Republic of Slovenia (Slovene: , abbr.: ''RS''), is a country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the southeast, an ...

and Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

to the south, and Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

and Liechtenstein

Liechtenstein (), officially the Principality of Liechtenstein (german: link=no, Fürstentum Liechtenstein), is a German-speaking microstate located in the Alps between Austria and Switzerland. Liechtenstein is a semi-constitutional monarchy ...

to the west. The country occupies an area of and has a population of 9 million.

Austria emerged from the remnants of the Eastern

Eastern may refer to:

Transportation

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

*Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 1926 to 1991

*Eastern Air Li ...

and Hungarian March

The Hungarian March (''Ungarische Mark'' or ''Ungarnmark'') or ''Neumark'' ("New March") was a brief frontier march established in the mid-eleventh century by the Emperor Henry III as a defence against the Kingdom of Hungary. It had only two known ...

at the end of the first millennium

File:1st millennium montage.png, From top left, clockwise: Depiction of Jesus, the central figure in Christianity; The Colosseum, a landmark of the once-mighty Roman Empire; Kaaba, the Great Mosque of Mecca, the holiest site of Islam; Chess, a n ...

. Originally a margraviate of Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

, it developed into a duchy of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

in 1156 and was later made an archduchy in 1453. In the 16th century, Vienna began serving as the empire's administrative capital and Austria thus became the heartland of the Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy (german: Habsburgermonarchie, ), also known as the Danubian monarchy (german: Donaumonarchie, ), or Habsburg Empire (german: Habsburgerreich, ), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities ...

. After the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire

The dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire occurred ''de facto'' on 6 August 1806, when the last Holy Roman Emperor, Francis II of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine, abdicated his title and released all imperial states and officials from their oaths ...

in 1806, Austria established its own empire, which became a great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power inf ...

and the dominant member of the German Confederation

The German Confederation (german: Deutscher Bund, ) was an association of 39 predominantly German-speaking sovereign states in Central Europe. It was created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 as a replacement of the former Holy Roman Empire, w ...

. The empire's defeat in the Austro-Prussian War

The Austro-Prussian War, also by many variant names such as Seven Weeks' War, German Civil War, Brothers War or Fraternal War, known in Germany as ("German War"), (; "German war of brothers") and by a variety of other names, was fought in 186 ...

of 1866 led to the end of the Confederation and paved the way for the establishment

Establishment may refer to:

* The Establishment, a dominant group or elite that controls a polity or an organization

* The Establishment (club), a 1960s club in London, England

* The Establishment (Pakistan), political terminology for the military ...

of Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

a year later.

After the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand

Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, heir presumptive to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife, Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, were assassinated on 28 June 1914 by Bosnian Serb student Gavrilo Princip. They were shot at close range whil ...

in 1914, Emperor Franz Joseph

Franz Joseph I or Francis Joseph I (german: Franz Joseph Karl, hu, Ferenc József Károly, 18 August 1830 – 21 November 1916) was Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, and the other states of the Habsburg monarchy from 2 December 1848 until his ...

declared war on Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe, Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Bas ...

, which ultimately escalated into World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. The empire's defeat and subsequent collapse led to the proclamation of the Republic of German-Austria

The Republic of German-Austria (german: Republik Deutschösterreich or ) was an unrecognised state that was created following World War I as an initial rump state for areas with a predominantly German-speaking and ethnic German population wi ...

in 1918 and the First Austrian Republic

The First Austrian Republic (german: Erste Österreichische Republik), officially the Republic of Austria, was created after the signing of the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye on 10 September 1919—the settlement after the end of World War I w ...

in 1919. During the interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days), the end of the World War I, First World War to the beginning of the World War II, Second World War. The in ...

, anti-parliamentarian sentiments culminated in the formation

Formation may refer to:

Linguistics

* Back-formation, the process of creating a new lexeme by removing or affixes

* Word formation, the creation of a new word by adding affixes

Mathematics and science

* Cave formation or speleothem, a secondar ...

of an Austrofascist dictatorship under Engelbert Dollfuss

Engelbert Dollfuß (alternatively: ''Dolfuss'', ; 4 October 1892 – 25 July 1934) was an Austrian clerical fascist politician who served as Chancellor of Austria between 1932 and 1934. Having served as Minister for Forests and Agriculture, he a ...

in 1934. A year before the outbreak of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Austria was annexed

Annexation (Latin ''ad'', to, and ''nexus'', joining), in international law, is the forcible acquisition of one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. It is generally held to be an illegal act ...

into Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

by Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

, and it became a sub-national division. After its liberation in 1945 and a decade of Allied occupation, the country regained its sovereignty and declared its perpetual neutrality in 1955.

Austria is a parliamentary

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democracy, democratic government, governance of a sovereign state, state (or subordinate entity) where the Executive (government), executive derives its democratic legitimacy ...

representative democracy

Representative democracy, also known as indirect democracy, is a type of democracy where elected people represent a group of people, in contrast to direct democracy. Nearly all modern Western-style democracies function as some type of represen ...

with a popularly elected president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

as head of state and a chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

as head of government and chief executive. Major cities

A city is a human settlement of notable size.Goodall, B. (1987) ''The Penguin Dictionary of Human Geography''. London: Penguin.Kuper, A. and Kuper, J., eds (1996) ''The Social Science Encyclopedia''. 2nd edition. London: Routledge. It can be def ...

include Vienna, Graz

Graz (; sl, Gradec) is the capital city of the Austrian state of Styria and second-largest city in Austria after Vienna. As of 1 January 2021, it had a population of 331,562 (294,236 of whom had principal-residence status). In 2018, the popul ...

, Linz

Linz ( , ; cs, Linec) is the capital of Upper Austria and third-largest city in Austria. In the north of the country, it is on the Danube south of the Czech border. In 2018, the population was 204,846.

In 2009, it was a European Capital of ...

, Salzburg

Salzburg (, ; literally "Salt-Castle"; bar, Soizbuag, label=Bavarian language, Austro-Bavarian) is the List of cities and towns in Austria, fourth-largest city in Austria. In 2020, it had a population of 156,872.

The town is on the site of the ...

, and Innsbruck

Innsbruck (; bar, Innschbruck, label=Bavarian language, Austro-Bavarian ) is the capital of Tyrol (state), Tyrol and the List of cities and towns in Austria, fifth-largest city in Austria. On the Inn (river), River Inn, at its junction with the ...

. Austria is consistently listed as one of the richest countries in the world by GDP

Gross domestic product (GDP) is a monetary measure of the market value of all the final goods and services produced and sold (not resold) in a specific time period by countries. Due to its complex and subjective nature this measure is often ...

per capita and one of the countries with the highest standard of living; it was ranked 25th in the world for its Human Development Index

The Human Development Index (HDI) is a statistic composite index of life expectancy, education (mean years of schooling completed and expected years of schooling upon entering the education system), and per capita income indicators, whi ...

in 2021.

Austria has been a member of the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

since 1955 and of the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been des ...

since 1995. It hosts the OSCE

The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) is the world's largest regional security-oriented intergovernmental organization with observer status at the United Nations. Its mandate includes issues such as arms control, prom ...

and OPEC

The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC, ) is a cartel of countries. Founded on 14 September 1960 in Baghdad by the first five members (Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela), it has, since 1965, been headquart ...

and is a founding member of the OECD

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD; french: Organisation de coopération et de développement économiques, ''OCDE'') is an intergovernmental organisation with 38 member countries, founded in 1961 to stimulate e ...

and Interpol

The International Criminal Police Organization (ICPO; french: link=no, Organisation internationale de police criminelle), commonly known as Interpol ( , ), is an international organization that facilitates worldwide police cooperation and cri ...

. It also signed the Schengen Agreement

The Schengen Agreement ( , ) is a treaty which led to the creation of Europe's Schengen Area, in which internal border checks have largely been abolished. It was signed on 14 June 1985, near the town of Schengen, Luxembourg, by five of the t ...

in 1995, and adopted the euro

The euro ( symbol: €; code: EUR) is the official currency of 19 out of the member states of the European Union (EU). This group of states is known as the eurozone or, officially, the euro area, and includes about 340 million citizens . ...

currency in 1999.

Etymology

The German name for Austria, , derives from theOld High German

Old High German (OHG; german: Althochdeutsch (Ahd.)) is the earliest stage of the German language, conventionally covering the period from around 750 to 1050.

There is no standardised or supra-regional form of German at this period, and Old High ...

, which meant "eastern realm" and which first appeared in the "Ostarrîchi document" of 996. This word is probably a translation of Medieval Latin

Medieval Latin was the form of Literary Latin used in Roman Catholic Western Europe during the Middle Ages. In this region it served as the primary written language, though local languages were also written to varying degrees. Latin functioned ...

into a local (Bavarian) dialect.

Austria was a prefecture of Bavaria created in 976. The word "Austria" is a Latinisation of the German name and was first recorded in the 12th century.

At the time, the Danube basin of Austria ( Upper and Lower Austria

Lower Austria (german: Niederösterreich; Austro-Bavarian: ''Niedaöstareich'', ''Niedaestareich'') is one of the nine states of Austria, located in the northeastern corner of the country. Since 1986, the capital of Lower Austria has been Sankt P ...

) was the easternmost extent of Bavaria.

History

The Central European land that is now Austria was settled in pre-Roman times by variousCelt

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient ...

ic tribes. The Celtic kingdom of Noricum

Noricum () is the Latin name for the Celts, Celtic kingdom or federation of tribes that included most of modern Austria and part of Slovenia. In the first century AD, it became a Roman province, province of the Roman Empire. Its borders were th ...

was later claimed by the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

and made a province. Present-day Petronell-Carnuntum

Carnuntum ( according to Ptolemy) was a Roman legionary fortress ( la, castra legionis) and headquarters of the Roman navy, Pannonian fleet from 50 AD. After the 1st century, it was capital of the Pannonia Superior province. It also became ...

in eastern Austria was an important army camp turned capital city in what became known as the Upper Pannonia province. Carnuntum was home for 50,000 people for nearly 400 years.

Middle Ages

After the fall of the Roman Empire, the area was invaded byBavarians

Bavarians ( Bavarian: ''Boarn'', Standard German: ''Baiern'') are an ethnographic group of Germans of the Bavaria region, a state within Germany. The group's dialect or speech is known as the Bavarian language, native to Altbayern ("Old Bava ...

, Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

and Avars. Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first Holy ...

, King of the Franks, conquered the area in AD 788, encouraged colonisation, and introduced Christianity.Johnson 19 As part of Eastern Francia

East Francia (Medieval Latin: ) or the Kingdom of the East Franks () was a successor state of Charlemagne's empire ruled by the Carolingian dynasty until 911. It was created through the Treaty of Verdun (843) which divided the former empire int ...

, the core areas that now encompass Austria were bequeathed to the house of Babenberg

The House of Babenberg was a noble dynasty of Austrian Dukes and Margraves. Originally from Bamberg in the Duchy of Franconia (present-day Bavaria), the Babenbergs ruled the imperial Margraviate of Austria from its creation in 976 AD until its e ...

. The area was known as the '' marchia Orientalis'' and was given to Leopold of Babenberg in 976.Johnson 20–21

Ostarrîchi

The German name of Austria, , derives from the Old High German word "eastern realm", recorded in the so-called '' Document'' of 996, applied to the Margraviate of Austria, a march, or borderland, of the Duchy of Bavaria created in 976.

The na ...

'', referring to the territory of the Babenberg March. In 1156, the Privilegium Minus

The is the denotation of a deed issued by Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa on 17 September 1156. It included the elevation of the Bavarian frontier march of Austria () to a duchy, which was given as an inheritable fief to the House of B ...

elevated Austria to the status of a duchy. In 1192, the Babenbergs also acquired the Duchy of Styria

Styria (german: Steiermark ; Serbo-Croatian and sl, ; hu, Stájerország) is a state (''Bundesland'') in the southeast of Austria. With an area of , Styria is the second largest state of Austria, after Lower Austria. Styria is bordered to ...

. With the death of Frederick II in 1246, the line of the Babenbergs was extinguished.Johnson 21

As a result, Ottokar II of Bohemia

Ottokar II ( cs, Přemysl Otakar II.; , in Městec Králové, Bohemia – 26 August 1278, in Dürnkrut, Lower Austria), the Iron and Golden King, was a member of the Přemyslid dynasty who reigned as King of Bohemia from 1253 until his deat ...

effectively assumed control of the duchies of Austria, Styria, and Carinthia

Carinthia (german: Kärnten ; sl, Koroška ) is the southernmost States of Austria, Austrian state, in the Eastern Alps, and is noted for its mountains and lakes. The main language is German language, German. Its regional dialects belong to t ...

. His reign came to an end with his defeat at Dürnkrut

The Battle on the Marchfeld (''i.e. Morava Field''; german: Schlacht auf dem Marchfeld; cs, Bitva na Moravském poli; hu, Morvamezei csata) at Dürnkrut and Jedenspeigen took place on 26 August 1278 and was a decisive event for the history ...

at the hands of Rudolph I of Germany

Rudolf I (1 May 1218 – 15 July 1291) was the first King of Germany from the House of Habsburg. The first of the count-kings of Germany, he reigned from 1273 until his death.

Rudolf's election marked the end of the Great Interregnum which h ...

in 1278. Thereafter, until World War I, Austria's history was largely that of its ruling dynasty, the Habsburgs

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

.

In the 14th and 15th centuries, the Habsburgs

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

began to accumulate other provinces in the vicinity of the Duchy of Austria. In 1438, Duke Albert V of Austria

Albert the Magnanimous KG, elected King of the Romans as Albert II (10 August 139727 October 1439) was king of the Holy Roman Empire and a member of the House of Habsburg. By inheritance he became Albert V, Duke of Austria. Through his wife ('' ...

was chosen as the successor to his father-in-law, Emperor Sigismund

Sigismund of Luxembourg (15 February 1368 – 9 December 1437) was a monarch as King of Hungary and Croatia ('' jure uxoris'') from 1387, King of Germany from 1410, King of Bohemia from 1419, and Holy Roman Emperor from 1433 until his death in ...

. Although Albert himself only reigned for a year, henceforth every emperor of the Holy Roman Empire was a Habsburg, with only one exception.

The Habsburgs began also to accumulate territory far from the hereditary lands. In 1477, Archduke Maximilian, only son of Emperor Frederick III, married the heiress Maria of Burgundy

Burgundy (; french: link=no, Bourgogne ) is a historical territory and former administrative region and province of east-central France. The province was once home to the Dukes of Burgundy from the early 11th until the late 15th century. The c ...

, thus acquiring most of the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

for the family.Lonnie Johnson 25Brook-Shepherd 11 In 1496, his son Philip the Fair

Philip IV (April–June 1268 – 29 November 1314), called Philip the Fair (french: Philippe le Bel), was King of France from 1285 to 1314. By virtue of his marriage with Joan I of Navarre, he was also King of Navarre as Philip I from 1 ...

married Joanna the Mad

Joanna (6 November 1479 – 12 April 1555), historically known as Joanna the Mad ( es, link=no, Juana la Loca), was the nominal Queen of Castile from 1504 and Queen of Aragon from 1516 to her death in 1555. She was married by arrangement to Phi ...

, the heiress of Castile and Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to sou ...

, thus acquiring Spain and its Italian, African, Asian

Asian may refer to:

* Items from or related to the continent of Asia:

** Asian people, people in or descending from Asia

** Asian culture, the culture of the people from Asia

** Asian cuisine, food based on the style of food of the people from Asi ...

and New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 3 ...

appendages for the Habsburgs.

In 1526, following the Battle of Mohács

The Battle of Mohács (; hu, mohácsi csata, tr, Mohaç Muharebesi or Mohaç Savaşı) was fought on 29 August 1526 near Mohács, Kingdom of Hungary, between the forces of the Kingdom of Hungary and its allies, led by Louis II, and thos ...

, Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

and the part of Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

not occupied by the Ottomans came under Austrian rule. Ottoman expansion into Hungary led to frequent conflicts between the two empires, particularly evident in the Long War of 1593 to 1606. The Turks made incursions into Styria

Styria (german: Steiermark ; Serbo-Croatian and sl, ; hu, Stájerország) is a state (''Bundesland'') in the southeast of Austria. With an area of , Styria is the second largest state of Austria, after Lower Austria. Styria is bordered to ...

nearly 20 times, of which some are cited as "burning, pillaging, and taking thousands of slaves". In late September 1529, Suleiman the Magnificent

Suleiman I ( ota, سليمان اول, Süleyman-ı Evvel; tr, I. Süleyman; 6 November 14946 September 1566), commonly known as Suleiman the Magnificent in the West and Suleiman the Lawgiver ( ota, قانونى سلطان سليمان, Ḳ� ...

launched the first siege of Vienna, which unsuccessfully ended, according to Ottoman historians, with the snowfalls of an early beginning winter.

17th and 18th centuries

During the long reign of Leopold I (1657–1705) and following the successful defence of Vienna against the Turks in 1683 (under the command of the King of Poland,

During the long reign of Leopold I (1657–1705) and following the successful defence of Vienna against the Turks in 1683 (under the command of the King of Poland, John III Sobieski

John III Sobieski ( pl, Jan III Sobieski; lt, Jonas III Sobieskis; la, Ioannes III Sobiscius; 17 August 1629 – 17 June 1696) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1674 until his death in 1696.

Born into Polish nobility, Sobie ...

), a series of campaigns resulted in bringing most of Hungary to Austrian control by the Treaty of Karlowitz

The Treaty of Karlowitz was signed in Karlowitz, Military Frontier of Archduchy of Austria (present-day Sremski Karlovci, Serbia), on 26 January 1699, concluding the Great Turkish War of 1683–1697 in which the Ottoman Empire was defeated by the ...

in 1699.

Emperor Charles VI

, house = Habsburg

, spouse =

, issue =

, issue-link = #Children

, issue-pipe =

, father = Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor

, mother = Eleonore Magdalene of Neuburg

, birth_date ...

relinquished many of the gains the empire made in the previous years, largely due to his apprehensions at the imminent extinction of the House of Habsburg. Charles was willing to offer concrete advantages in territory and authority in exchange for recognition of the Pragmatic Sanction

A pragmatic sanction is a sovereign's solemn decree on a matter of primary importance and has the force of fundamental law. In the late history of the Holy Roman Empire, it referred more specifically to an edict issued by the Emperor.

When used ...

that made his daughter Maria Theresa

Maria Theresa Walburga Amalia Christina (german: Maria Theresia; 13 May 1717 – 29 November 1780) was ruler of the Habsburg dominions from 1740 until her death in 1780, and the only woman to hold the position ''suo jure'' (in her own right). ...

his heir. With the rise of Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

, the Austrian–Prussian dualism began in Germany. Austria participated, together with Prussia and Russia, in the first and the third of the three Partitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland were three partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that took place toward the end of the 18th century and ended the existence of the state, resulting in the elimination of sovereign Poland and Lithuania for 12 ...

(in 1772 and 1795).

From that time, Austria became the birthplace of classical music

Classical music generally refers to the art music of the Western world, considered to be distinct from Western folk music or popular music traditions. It is sometimes distinguished as Western classical music, as the term "classical music" also ...

and played host to different composers including Ludwig van Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classical ...

, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 17565 December 1791), baptised as Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart, was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period. Despite his short life, his rapid pace of composition r ...

, Joseph Haydn

Franz Joseph Haydn ( , ; 31 March 173231 May 1809) was an Austrian composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. He was instrumental in the development of chamber music such as the string quartet and piano trio. His contributions ...

and Franz Schubert

Franz Peter Schubert (; 31 January 179719 November 1828) was an Austrian composer of the late Classical and early Romantic eras. Despite his short lifetime, Schubert left behind a vast ''oeuvre'', including more than 600 secular vocal wor ...

.

19th century

Revolutionary France

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

, at the beginning highly unsuccessfully, with successive defeats at the hands of Napoleon, meaning the end of the old Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

in 1806. Two years earlier, the Empire of Austria

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central-Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, ...

was founded. From 1792 to 1801, the Austrians had suffered 754,700 casualties. In 1814, Austria was part of the Allied forces that invaded France and brought to an end the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

.

It emerged from the Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon B ...

in 1815 as one of the continent's four dominant powers and a recognised great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power inf ...

. The same year, the German Confederation

The German Confederation (german: Deutscher Bund, ) was an association of 39 predominantly German-speaking sovereign states in Central Europe. It was created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 as a replacement of the former Holy Roman Empire, w ...

() was founded under the presidency of Austria. Because of unsolved social, political, and national conflicts, the German lands were shaken by the 1848 revolutions

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europe ...

aiming to create a unified Germany.Johnson 36

Greater Germany

Pan-Germanism (german: Pangermanismus or '), also occasionally known as Pan-Germanicism, is a pan-nationalist political idea. Pan-Germanists originally sought to unify all the German-speaking people – and possibly also Germanic-speaking ...

, or a Greater Austria or just the German Confederation without Austria at all. As Austria was not willing to relinquish its German-speaking territories to what would become the German Empire of 1848, the crown of the newly formed empire was offered to the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV

Frederick William IV (german: Friedrich Wilhelm IV.; 15 October 17952 January 1861), the eldest son and successor of Frederick William III of Prussia, reigned as King of Prussia from 7 June 1840 to his death on 2 January 1861. Also referred to ...

. In 1864, Austria and Prussia fought together against Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark

...

and secured the independence from Denmark of the duchies of Schleswig

The Duchy of Schleswig ( da, Hertugdømmet Slesvig; german: Herzogtum Schleswig; nds, Hartogdom Sleswig; frr, Härtochduum Slaswik) was a duchy in Southern Jutland () covering the area between about 60 km (35 miles) north and 70 km ...

and Holstein

Holstein (; nds, label=Northern Low Saxon, Holsteen; da, Holsten; Latin and historical en, Holsatia, italic=yes) is the region between the rivers Elbe and Eider. It is the southern half of Schleswig-Holstein, the northernmost state of German ...

. As they could not agree on how the two duchies should be administered, though, they fought the Austro-Prussian War

The Austro-Prussian War, also by many variant names such as Seven Weeks' War, German Civil War, Brothers War or Fraternal War, known in Germany as ("German War"), (; "German war of brothers") and by a variety of other names, was fought in 186 ...

in 1866. Defeated by Prussia in the Battle of Königgrätz

The Battle of Königgrätz (or Sadowa) was the decisive battle of the Austro-Prussian War in which the Kingdom of Prussia defeated the Austrian Empire. It took place on 3 July 1866, near the Bohemian city of Hradec Králové (German: Königgrä ...

, Austria had to leave the German Confederation and no longer took part in German politics.Lonnie Johnson 55

After the defeated Hungarian Revolution of 1848

The Hungarian Revolution of 1848 or fully Hungarian Civic Revolution and War of Independence of 1848–1849 () was one of many European Revolutions of 1848 and was closely linked to other revolutions of 1848 in the Habsburg areas. Although th ...

, the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867

The Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 (german: Ausgleich, hu, Kiegyezés) established the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary. The Compromise only partially re-established the former pre-1848 sovereignty and status of the Kingdom of Hungary ...

, the ''Ausgleich'', provided for a dual sovereignty, the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central-Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, ...

and the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the coronation of the first king Stephen ...

, under Franz Joseph I

Franz Joseph I or Francis Joseph I (german: Franz Joseph Karl, hu, Ferenc József Károly, 18 August 1830 – 21 November 1916) was Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, and the other states of the Habsburg monarchy from 2 December 1848 until his ...

. The Austrian-Hungarian rule of this diverse empire included various groups, including Hungarians

Hungarians, also known as Magyars ( ; hu, magyarok ), are a nation and ethnic group native to Hungary () and historical Hungarian lands who share a common culture, history, ancestry, and language. The Hungarian language belongs to the Urali ...

, Croats, Czechs, Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in Ce ...

, Rusyns

Rusyns (), also known as Carpatho-Rusyns (), or Rusnaks (), are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group from the Carpathian Rus', Eastern Carpathians in Central Europe. They speak Rusyn language, Rusyn, an East Slavic languages, East Slavi ...

, Serbs, Slovaks, Slovenes, and Ukrainians, as well as large Italian and Romanian communities.

As a result, ruling Austria-Hungary became increasingly difficult in an age of emerging nationalist movements, requiring considerable reliance on an expanded secret police. Yet, the government of Austria tried its best to be accommodating in some respects: for example, the ''Reichsgesetzblatt'', publishing the laws and ordinances of Cisleithania

Cisleithania, also ''Zisleithanien'' sl, Cislajtanija hu, Ciszlajtánia cs, Předlitavsko sk, Predlitavsko pl, Przedlitawia sh-Cyrl-Latn, Цислајтанија, Cislajtanija ro, Cisleithania uk, Цислейтанія, Tsysleitaniia it, Cislei ...

, was issued in eight languages; and all national groups were entitled to schools in their own language and to the use of their mother tongue at state offices.

Georg Ritter von Schönerer

Georg Ritter von Schönerer (17 July 1842 – 14 August 1921) was an Austrian landowner and politician of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy active in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A major exponent of pan-Germanism and German nationalism in ...

promoted strong pan-Germanism

Pan-Germanism (german: Pangermanismus or '), also occasionally known as Pan-Germanicism, is a pan-nationalist political idea. Pan-Germanists originally sought to unify all the German-speaking people – and possibly also Germanic-speaking ...

in hope of reinforcing an ethnic German identity and the annexation of Austria to Germany. Some Austrians such as Karl Lueger

Karl Lueger (; 24 October 1844 – 10 March 1910) was an Austrian politician, mayor of Vienna, and leader and founder of the Austrian Christian Social Party. He is credited with the transformation of the city of Vienna into a modern city. The pop ...

also used pan-Germanism as a form of populism to further their own political goals. Although Bismarck's policies excluded Austria and the German Austrians from Germany, many Austrian pan-Germans idolised him and wore blue cornflowers, known to be the favourite flower of German Emperor William I

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England, reigning from 1066 until his death in 1087 ...

, in their buttonholes, along with cockades in the German national colours (black, red, and yellow), although they were both temporarily banned in Austrian schools, as a way to show discontent towards the multi-ethnic empire.

Austria's exclusion from Germany caused many Austrians a problem with their national identity and prompted the Social Democratic Leader Otto Bauer

Otto Bauer (5 September 1881 – 4 July 1938) was one of the founders and leading thinkers of the left-socialist Austromarxists who sought a middle ground between social democracy and revolutionary socialism. He was a member of the Austrian Parli ...

to state that it was "the conflict between our Austrian and German character". The Austro-Hungarian Empire caused ethnic tension between the German Austrians and the other ethnic groups. Many Austrians, especially those involved with the pan-German movements, desired a reinforcement of an ethnic German identity and hoped that the empire would collapse, which would allow an annexation of Austria by Germany.

A lot of Austrian pan-German nationalists protested passionately against minister-president Kasimir Count Badeni's language decree of 1897, which made German and Czech co-official languages in Bohemia and required new government officials to be fluent in both languages. This meant in practice that the civil service would almost exclusively hire Czechs, because most middle-class Czechs spoke German but not the other way around. The support of ultramontane

Ultramontanism is a clerical political conception within the Catholic Church that places strong emphasis on the prerogatives and powers of the Pope. It contrasts with Gallicanism, the belief that popular civil authority—often represented by th ...

Catholic politicians and clergy for this reform triggered the launch of the "Away from Rome

''Away from Rome!'' (german: Los-von-Rom-Bewegung) was a religious movement founded in Austria by the Pan-German politician Georg Ritter von Schönerer aimed at conversion of all the Roman Catholic German-speaking population of Austria to Luthera ...

" (german: Los-von-Rom) movement, which was initiated by supporters of Schönerer and called on "German" Christians to leave the Roman Catholic Church.

20th century

As theSecond Constitutional Era

The Second Constitutional Era ( ota, ایكنجی مشروطیت دورى; tr, İkinci Meşrutiyet Devri) was the period of restored parliamentary rule in the Ottoman Empire between the 1908 Young Turk Revolution and the 1920 dissolution of the G ...

began in the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, Austria-Hungary took the opportunity to annex Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of south and southeast Europe, located in the Balkans. Bosnia and H ...

in 1908. The

assassination

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have ...

of Archduke Franz Ferdinand

Archduke Franz Ferdinand Carl Ludwig Joseph Maria of Austria, (18 December 1863 – 28 June 1914) was the heir presumptive to the throne of Austria-Hungary. His assassination in Sarajevo was the most immediate cause of World War I.

Fr ...

in Sarajevo

Sarajevo ( ; cyrl, Сарајево, ; ''see Names of European cities in different languages (Q–T)#S, names in other languages'') is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with a population of 275,524 in its a ...

in 1914 by Bosnian Serb Gavrilo Princip

Gavrilo Princip ( sr-Cyrl, Гаврило Принцип, ; 25 July 189428 April 1918) was a Bosnian Serb student who assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914.

Prin ...

was used by leading Austrian politicians and generals to persuade the emperor to declare war on Serbia, thereby risking and prompting the outbreak of World War I, which eventually led to the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Over one million Austro-Hungarian soldiers died in World War I.

On 21 October 1918, the elected German members of the ''Reichsrat'' (parliament of Imperial Austria) met in Vienna as the Provisional National Assembly for German Austria (''Provisorische Nationalversammlung für Deutschösterreich''). On 30 October the assembly founded the

On 21 October 1918, the elected German members of the ''Reichsrat'' (parliament of Imperial Austria) met in Vienna as the Provisional National Assembly for German Austria (''Provisorische Nationalversammlung für Deutschösterreich''). On 30 October the assembly founded the Republic of German Austria

The Republic of German-Austria (german: Republik Deutschösterreich or ) was an unrecognised state that was created following World War I as an initial rump state for areas with a predominantly German-speaking and ethnic German population wit ...

by appointing a government, called ''Staatsrat''. This new government was invited by the Emperor to take part in the decision on the planned armistice with Italy, but refrained from this business.

This left the responsibility for the end of the war, on 3 November 1918, solely to the emperor and his government. On 11 November, the emperor, advised by ministers of the old and the new governments, declared he would not take part in state business any more; on 12 November, German Austria

The Republic of German-Austria (german: Republik Deutschösterreich or ) was an unrecognised state that was created following World War I as an initial rump state for areas with a predominantly German-speaking and ethnic German population wit ...

, by law, declared itself to be a democratic republic and part of the new German republic. The constitution, renaming the ''Staatsrat'' as ''Bundesregierung'' (federal government) and ''Nationalversammlung'' as ''Nationalrat'' (national council) was passed on 10 November 1920.

The Treaty of Saint-Germain

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal perso ...

of 1919 (for Hungary the Treaty of Trianon

The Treaty of Trianon (french: Traité de Trianon, hu, Trianoni békeszerződés, it, Trattato del Trianon) was prepared at the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace Conference and was signed in the Grand Trianon château in ...

of 1920) confirmed and consolidated the new order of Central Europe which to a great extent had been established in November 1918, creating new states and altering others. The German-speaking parts of Austria which had been part of Austria-Hungary were reduced to a rump state named The Republic of German-Austria

The Republic of German-Austria (german: Republik Deutschösterreich or ) was an unrecognised state that was created following World War I as an initial rump state for areas with a predominantly German-speaking and ethnic German population wi ...

(German: ''Republik Deutschösterreich''), though excluding the predominantly German-speaking South Tyrol

it, Provincia Autonoma di Bolzano – Alto Adige lld, Provinzia Autonoma de Balsan/Bulsan – Südtirol

, settlement_type = Autonomous province

, image_skyline =

, image_alt ...

. The desire for ''Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, en, Annexation of Austria), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into the German Reich on 13 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a " Greater Germany ...

'' (annexation of Austria to Germany) was a popular opinion shared by all social circles in both Austria and Germany. On 12 November, German-Austria was declared a republic, and named Social Democrat Karl Renner

Karl Renner (14 December 1870 – 31 December 1950) was an Austrian politician and jurist of the Social Democratic Workers' Party of Austria. He is often referred to as the "Father of the Republic" because he led the first government of German-A ...

as provisional chancellor. On the same day it drafted a provisional constitution that stated that "German-Austria is a democratic republic" (Article 1) and "German-Austria is an integral part of the German reich" (Article 2). The Treaty of Saint Germain and the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

explicitly forbade union between Austria and Germany. The treaties also forced German-Austria to rename itself as "Republic of Austria" which consequently led to the first Austrian Republic

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ci ...

.

Over 3 million German-speaking Austrians found themselves living outside the new Austrian Republic as minorities in the newly formed or enlarged states of Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

, Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

, Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

, and Italy. These included the provinces of South Tyrol

it, Provincia Autonoma di Bolzano – Alto Adige lld, Provinzia Autonoma de Balsan/Bulsan – Südtirol

, settlement_type = Autonomous province

, image_skyline =

, image_alt ...

(which became part of Italy) and German Bohemia

The Province of German Bohemia (german: Provinz Deutschböhmen ; cs, Německé Čechy) was a province in Bohemia, now the Czech Republic, established for a short period of time after the First World War, as part of the Republic of German-Austria ...

(Czechoslovakia). The status of German Bohemia (Sudetenland) later played a role in sparking the Second World War.Brook-Shepherd 245

The status of South Tyrol was a lingering problem between Austria and Italy until it was officially settled by the 1980s with a great degree of autonomy being granted to it by the Italian national government.

The border between Austria and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Kraljevina Jugoslavija, Краљевина Југославија; sl, Kraljevina Jugoslavija) was a state in Southeast and Central Europe that existed from 1918 until 1941. From 1918 ...

(later Yugoslavia) was settled with the Carinthian Plebiscite

The Carinthian plebiscite (german: Kärntner Volksabstimmung, sl, Koroški plebiscit) was held on 10 October 1920 in the area in southern Carinthia predominantly settled by Carinthian Slovenes. It determined the final border between the Republi ...

in October 1920 and allocated the major part of the territory of the former Austro-Hungarian Crownland of Carinthia to Austria. This set the border on the Karawanken

The Karawanks or Karavankas or Karavanks ( sl, Karavanke; german: Karawanken, ) are a mountain range of the Southern Limestone Alps on the border between Slovenia to the south and Austria to the north. With a total length of in an east–west dir ...

mountain range, with many Slovenes remaining in Austria.

Interwar period and World War II

After the war, inflation began to devalue the Krone, which was still Austria's currency. In autumn 1922, Austria was granted an international loan supervised by theLeague of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

. The purpose of the loan was to avert bankruptcy, stabilise the currency, and improve Austria's general economic condition. The loan meant that Austria passed from an independent state to the control exercised by the League of Nations. In 1925, the ''Schilling Schilling may refer to:

* Schilling (unit), an historical unit of measurement

* Schilling (coin), the historical European coin

* Austrian schilling, the former currency of Austria

* A. Schilling & Company, an historical West Coast spice firm acquir ...

'' was introduced, replacing the Krone at a rate of 10,000:1. Later, it was nicknamed the "Alpine dollar" due to its stability. From 1925 to 1929, the economy enjoyed a short high before nearly crashing after Black Tuesday

The Wall Street Crash of 1929, also known as the Great Crash, was a major American stock market crash that occurred in the autumn of 1929. It started in September and ended late in October, when share prices on the New York Stock Exchange colla ...

.

The First Austrian Republic

The First Austrian Republic (german: Erste Österreichische Republik), officially the Republic of Austria, was created after the signing of the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye on 10 September 1919—the settlement after the end of World War I w ...

lasted until 1933, when Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss

Engelbert Dollfuß (alternatively: ''Dolfuss'', ; 4 October 1892 – 25 July 1934) was an Austrian clerical fascist politician who served as Chancellor of Austria between 1932 and 1934. Having served as Minister for Forests and Agriculture, he a ...

, using what he called "self-switch-off of Parliament", established an autocratic regime tending towards Italian fascism.Lonnie Johnson 104Brook-Shepherd 269–70 The two big parties at this time, the Social Democrats and the Conservatives, had paramilitary armies;Brook-Shepherd 261 the Social Democrats' ''Schutzbund

The Republikanischer Schutzbund (, ''Republican Protection League'') was an Austrian paramilitary organization established in 1923 by the Social Democratic Party (SDAPÖ) to secure power

in the face of rising political radicalization after World ...

'' was now declared illegal, but was still operative as civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

broke out.Johnson 107

In February 1934, several members of the ''Schutzbund'' were executed, the Social Democratic party was outlawed, and many of its members were imprisoned or emigrated. On 1 May 1934, the Austrofascists imposed a new constitution ("Maiverfassung") which cemented Dollfuss's power, but on 25 July he was assassinated in a Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

coup attempt.

His successor

His successor Kurt Schuschnigg

Kurt Alois Josef Johann von Schuschnigg (; 14 December 1897 – 18 November 1977) was an Austrian Fatherland Front politician who was the Chancellor of the Federal State of Austria from the 1934 assassination of his predecessor Engelbert Dollf ...

acknowledged the fact that Austria was a "German state" and he also believed that Austrians were "better Germans" but he wished that Austria would remain independent. He announced a referendum on 9 March 1938, to be held on 13 March, concerning Austria's independence from Germany. On 12 March 1938, Austrian Nazis took over the government, while German troops occupied the country, which prevented Schuschnigg's referendum from taking place.Lonnie Johnson 112–3 On 13 March 1938, the ''Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, en, Annexation of Austria), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into the German Reich on 13 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a " Greater Germany ...

'' of Austria was officially declared. Two days later, Austrian-born Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and then ...

announced what he called the "reunification" of his home country with the "rest of the German Reich

German ''Reich'' (lit. German Realm, German Empire, from german: Deutsches Reich, ) was the constitutional name for the German nation state that existed from 1871 to 1945. The ''Reich'' became understood as deriving its authority and sovereignty ...

" on Vienna's Heldenplatz

Heldenplatz (german: Heroes' Square) is a public space in front of the Hofburg Palace in Vienna, Austria. Located in the Innere Stadt borough, the President of Austria resides in the adjoining Hofburg wing, while the Federal Chancellery is on adj ...

. He established a plebiscite which confirmed the union with Germany in April 1938.

Parliamentary elections were held in Germany (including recently annexed Austria) on 10 April 1938. They were the final elections to the Reichstag during Nazi rule, and they took the form of a single-question referendum asking whether voters approved of a single Nazi-party list for the 813-member Reichstag, as well as the recent annexation of Austria (the Anschluss). Jews, Roma and Sinti were not allowed to vote. Turnout in the election was officially 99.5%, with 98.9% voting "yes". In the case of Austria, Adolf Hitler's native soil, 99.71% of an electorate of 4,484,475 officially went to the ballots, with a positive tally of 99.73%.1938 German election and referendum

Parliamentary elections were held in Germany (including recently annexed Austria) on 10 April 1938. Dieter Nohlen & Philip Stöver (2010) ''Elections in Europe: A data handbook'', p762 They were the final elections to the Reichstag during Naz ...

Although most Austrians favored the ''Anschluss'', in certain parts of Austria, the German soldiers were not always welcomed with flowers and joy, especially in Vienna, which had Austria's largest Jewish population. Nevertheless, despite the propaganda and the manipulation and rigging which surrounded the ballot box result, there was massive genuine support for Hitler for fulfilling the ''Anschluss'', since many Germans from both Austria and Germany saw it as completing the long overdue unification of all Germans into one state.

On 12 March 1938, Austria was annexed by the

On 12 March 1938, Austria was annexed by the Third Reich

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and it ceased to exist as an independent country. The Aryanisation

Aryanization (german: Arisierung) was the Nazi term for the seizure of property from Jews and its transfer to non-Jews, and the forced expulsion of Jews from economic life in Nazi Germany, Axis-aligned states, and their occupied territories. I ...

of the wealth of Jewish Austrians started immediately in mid-March, with a so-called "wild" (i.e. extra-legal) phase, but it was soon structured legally and bureaucratically so the assets which Jewish citizens possessed could be stripped from them. At that time, Adolf Eichmann

Otto Adolf Eichmann ( ,"Eichmann"

''

The politics of the Nazi past in Germany and Austria

'". Cambridge University Press. p. 43. In the Vienna fell on 13 April 1945, during the

Vienna fell on 13 April 1945, during the

Much like Germany, Austria was

Much like Germany, Austria was

The

The

After general elections held in October 2006, the

After general elections held in October 2006, the

The 1955

The 1955

The manpower of the Austrian Armed Forces (german: link=no, Bundesheer) mainly relies on

The manpower of the Austrian Armed Forces (german: link=no, Bundesheer) mainly relies on  In 2012, Austria's defence expenditures corresponded to approximately 0.8% of its GDP. The Army currently has about 26,000 soldiers, of whom about 12,000 are conscripts. As head of state,

In 2012, Austria's defence expenditures corresponded to approximately 0.8% of its GDP. The Army currently has about 26,000 soldiers, of whom about 12,000 are conscripts. As head of state,

Austria is a largely mountainous country because of its location in the

Austria is a largely mountainous country because of its location in the

The greater part of Austria lies in the cool/temperate

The greater part of Austria lies in the cool/temperate

Austria consistently ranks high in terms of

Austria consistently ranks high in terms of  Austria indicated on 16 November 2010 that it would withhold the December installment of its contribution to the EU bailout of Greece, citing the material worsening of the Greek debt situation and the apparent inability of Greece to collect the level of tax receipts it had previously promised.

The

Austria indicated on 16 November 2010 that it would withhold the December installment of its contribution to the EU bailout of Greece, citing the material worsening of the Greek debt situation and the apparent inability of Greece to collect the level of tax receipts it had previously promised.

The

In 1972, the country began construction of a

In 1972, the country began construction of a

Austria's population was estimated to be nearly 9 million (8.9) in 2020 by Statistik Austria. The population of the capital,

Austria's population was estimated to be nearly 9 million (8.9) in 2020 by Statistik Austria. The population of the capital,

Historically Austrians were regarded as ethnic Germans and viewed themselves as such, although this national identity was challenged by Austrian nationalism in the decades after the end of World War I and even more so after World War II. Austria was part of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation until its ending in 1806 and had been part of the

Historically Austrians were regarded as ethnic Germans and viewed themselves as such, although this national identity was challenged by Austrian nationalism in the decades after the end of World War I and even more so after World War II. Austria was part of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation until its ending in 1806 and had been part of the  The Turks in Austria, Turks are the largest single immigrant group in Austria, closely followed by the Serbs in Austria, Serbs. Serbs form one of the largest ethnic groups in Austria, numbering around 300,000 people. Historically, Serbian immigrants moved to Austria during the time of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, when Vojvodina was under Imperial control. Following

The Turks in Austria, Turks are the largest single immigrant group in Austria, closely followed by the Serbs in Austria, Serbs. Serbs form one of the largest ethnic groups in Austria, numbering around 300,000 people. Historically, Serbian immigrants moved to Austria during the time of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, when Vojvodina was under Imperial control. Following

retrieved 14 January 2015 and further increased to 22.4% (1,997,700 people) in 2021. Of the remaining people, around 340,000 were registered as members of various Muslim communities in 2001, mainly due to the influx from Turkey, Bosnia-Herzegovina and

Education in Austria is entrusted partly to the States of Austria, Austrian states (Bundesländer) and partly to the federal government. School attendance is compulsory education, compulsory for nine years, i.e. usually to the age of fifteen.

Pre-school education (called ''Kindergarten'' in German), free in most states, is provided for all children between the ages of three and six years and, whilst optional, is considered a normal part of a child's education due to its high takeup rate. Maximum class size is around 30, each class normally being cared for by one qualified teacher and one assistant.

Primary education, or Volksschule, lasts for four years, starting at age six. The maximum class size is 30, but may be as low as 15. It is generally expected that a class will be taught by one teacher for the entire four years and the stable bond between teacher and pupil is considered important for a child's well-being. The The three Rs, 3Rs (Reading, wRiting and aRithmetic) dominate lesson time, with less time allotted to project work than in the UK. Children work individually and all members of a class follow the same plan of work. There is no Streaming (education), streaming.

Standard attendance times are 8 am to 12 pm or 1 pm, with hourly five- or ten-minute breaks. Children are given homework daily from the first year. Historically there has been no lunch hour, with children returning home to eat. However, due to a rise in the number of mothers in work, primary schools are increasingly offering pre-lesson and afternoon care.

Education in Austria is entrusted partly to the States of Austria, Austrian states (Bundesländer) and partly to the federal government. School attendance is compulsory education, compulsory for nine years, i.e. usually to the age of fifteen.

Pre-school education (called ''Kindergarten'' in German), free in most states, is provided for all children between the ages of three and six years and, whilst optional, is considered a normal part of a child's education due to its high takeup rate. Maximum class size is around 30, each class normally being cared for by one qualified teacher and one assistant.

Primary education, or Volksschule, lasts for four years, starting at age six. The maximum class size is 30, but may be as low as 15. It is generally expected that a class will be taught by one teacher for the entire four years and the stable bond between teacher and pupil is considered important for a child's well-being. The The three Rs, 3Rs (Reading, wRiting and aRithmetic) dominate lesson time, with less time allotted to project work than in the UK. Children work individually and all members of a class follow the same plan of work. There is no Streaming (education), streaming.

Standard attendance times are 8 am to 12 pm or 1 pm, with hourly five- or ten-minute breaks. Children are given homework daily from the first year. Historically there has been no lunch hour, with children returning home to eat. However, due to a rise in the number of mothers in work, primary schools are increasingly offering pre-lesson and afternoon care.

As in Germany, secondary education consists of two main types of schools, attendance at which is based on a pupil's ability as determined by grades from the primary school. The Gymnasium (school), Gymnasium caters for the more able children, in the final year of which the Matura examination is taken, which is a requirement for access to university. The Hauptschule prepares pupils for vocational education but also for various types of further education (Höhere Technische Lehranstalt HTL = institution of higher technical education; HAK = commercial academy; HBLA = institution of higher education for economic business; etc.). Attendance at one of these further education institutes also leads to the Matura. Some schools aim to combine the education available at the Gymnasium and the Hauptschule, and are known as Gesamtschule#Germany, Gesamtschulen. In addition, a recognition of the importance of learning English has led some Gymnasiums to offer a bilingual stream, in which pupils deemed able in languages follow a modified curriculum, a portion of the lesson time being conducted in English.

As at primary school, lessons at Gymnasium begin at 8 am and continue with short intervals until lunchtime or early afternoon, with children returning home to a late lunch. Older pupils often attend further lessons after a break for lunch, generally eaten at school. As at primary level, all pupils follow the same plan of work. Great emphasis is placed on homework and frequent testing. Satisfactory marks in the end-of-the-year report ("Zeugnis") are a prerequisite for moving up ("aufsteigen") to the next class. Pupils who do not meet the required standard re-sit their tests at the end of the summer holidays; those whose marks are still not satisfactory are required to re-sit the year ("sitzenbleiben").

It is not uncommon for a pupil to re-sit more than one year of school. After completing the first two years, pupils choose between one of two strands, known as "Gymnasium" (slightly more emphasis on arts) or "Realgymnasium" (slightly more emphasis on science). Whilst many schools offer both strands, some do not, and as a result, some children move schools for a second time at age 12. At age 14, pupils may choose to remain in one of these two strands, or to change to a vocational course, possibly with a further change of school.

As in Germany, secondary education consists of two main types of schools, attendance at which is based on a pupil's ability as determined by grades from the primary school. The Gymnasium (school), Gymnasium caters for the more able children, in the final year of which the Matura examination is taken, which is a requirement for access to university. The Hauptschule prepares pupils for vocational education but also for various types of further education (Höhere Technische Lehranstalt HTL = institution of higher technical education; HAK = commercial academy; HBLA = institution of higher education for economic business; etc.). Attendance at one of these further education institutes also leads to the Matura. Some schools aim to combine the education available at the Gymnasium and the Hauptschule, and are known as Gesamtschule#Germany, Gesamtschulen. In addition, a recognition of the importance of learning English has led some Gymnasiums to offer a bilingual stream, in which pupils deemed able in languages follow a modified curriculum, a portion of the lesson time being conducted in English.

As at primary school, lessons at Gymnasium begin at 8 am and continue with short intervals until lunchtime or early afternoon, with children returning home to a late lunch. Older pupils often attend further lessons after a break for lunch, generally eaten at school. As at primary level, all pupils follow the same plan of work. Great emphasis is placed on homework and frequent testing. Satisfactory marks in the end-of-the-year report ("Zeugnis") are a prerequisite for moving up ("aufsteigen") to the next class. Pupils who do not meet the required standard re-sit their tests at the end of the summer holidays; those whose marks are still not satisfactory are required to re-sit the year ("sitzenbleiben").

It is not uncommon for a pupil to re-sit more than one year of school. After completing the first two years, pupils choose between one of two strands, known as "Gymnasium" (slightly more emphasis on arts) or "Realgymnasium" (slightly more emphasis on science). Whilst many schools offer both strands, some do not, and as a result, some children move schools for a second time at age 12. At age 14, pupils may choose to remain in one of these two strands, or to change to a vocational course, possibly with a further change of school.

The Austrian university system had been open to any student who passed the Matura examination until recently. A 2006 bill allowed the introduction of entrance exams for studies such as Medicine. In 2001, an obligatory tuition fee ("''Studienbeitrag''") of €363.36 per term was introduced for all public universities. Since 2008, for all EU students the studies have been free of charge, as long as a certain time-limit is not exceeded (the expected duration of the study plus usually two terms tolerance). When the time-limit is exceeded, the fee of around €363.36 per term is charged. Some further exceptions to the fee apply, e.g. for students with a year's salary of more than about €5000. In all cases, an obligatory fee of €20.20 is charged for the student union and insurance.