Arthur C. Clark on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Arthur Charles Clarke (16 December 191719 March 2008) was an English science-fiction writer, science writer,

In 1986, Clarke was named a Grand Master by the

In 1986, Clarke was named a Grand Master by the

Although he and his home were unharmed by the

Although he and his home were unharmed by the

In 1948, he wrote "The Sentinel (short story), The Sentinel" for a BBC competition. Though the story was rejected, it changed the course of Clarke's career. Not only was it the basis for ''2001: A Space Odyssey'', but "The Sentinel" also introduced a more cosmic element to Clarke's work. Many of Clarke's later works feature a technologically advanced but still-prejudiced mankind being confronted by a superior alien intelligence. In the cases of ''Childhood's End'', and the ''2001'' series, this encounter produces a conceptual breakthrough that accelerates humanity into the next stage of its evolution. This also applies in the far-distant past (but our future) in ''The City and the Stars'' (and its original version, ''Against the Fall of Night'').

In Clarke's authorised biography, Neil McAleer writes: "many readers and critics still consider ''Childhood's End'' Arthur C. Clarke's best novel." But Clarke did not use Extrasensory perception, ESP in any of his later stories, saying, "I've always been interested in ESP, and of course, ''Childhood's End ''was about that. But I've grown disillusioned, partly because after all this time, they're still arguing about whether these things happen. I suspect that telepathy does happen."

A collection of early essays was published in ''The View from Serendip'' (1977), which also included one short piece of fiction, "When the Twerms Came". Clarke also wrote short stories under the pseudonyms of E. G. O'Brien and Charles Willis. Almost all of his short stories can be found in the book ''The Collected Stories of Arthur C. Clarke'' (2001).

In 1948, he wrote "The Sentinel (short story), The Sentinel" for a BBC competition. Though the story was rejected, it changed the course of Clarke's career. Not only was it the basis for ''2001: A Space Odyssey'', but "The Sentinel" also introduced a more cosmic element to Clarke's work. Many of Clarke's later works feature a technologically advanced but still-prejudiced mankind being confronted by a superior alien intelligence. In the cases of ''Childhood's End'', and the ''2001'' series, this encounter produces a conceptual breakthrough that accelerates humanity into the next stage of its evolution. This also applies in the far-distant past (but our future) in ''The City and the Stars'' (and its original version, ''Against the Fall of Night'').

In Clarke's authorised biography, Neil McAleer writes: "many readers and critics still consider ''Childhood's End'' Arthur C. Clarke's best novel." But Clarke did not use Extrasensory perception, ESP in any of his later stories, saying, "I've always been interested in ESP, and of course, ''Childhood's End ''was about that. But I've grown disillusioned, partly because after all this time, they're still arguing about whether these things happen. I suspect that telepathy does happen."

A collection of early essays was published in ''The View from Serendip'' (1977), which also included one short piece of fiction, "When the Twerms Came". Clarke also wrote short stories under the pseudonyms of E. G. O'Brien and Charles Willis. Almost all of his short stories can be found in the book ''The Collected Stories of Arthur C. Clarke'' (2001).

For much of the later 20th century, Clarke,

For much of the later 20th century, Clarke,

Clarke contributed to the popularity of the idea that

Clarke contributed to the popularity of the idea that

The Problem of Space TravelThe Rocket Motor

'', sections: ''Providing for Long Distance Communications and Safety'', and (possibly referring to the idea of relaying messages via satellite, but not that three would be optimal) ''Observing and Researching the Earth's Surface'', published in Berlin. Clarke acknowledged the earlier concept in his book ''Profiles of the Future''.

"To Mars by A-Bomb: The Secret History of Project Orion (2003)"

, IMDb.

* ''The Martians and Us'' (2006)

* ''Planetary Defense'' (2007)

* ''Vision of a Future Passed: The Prophecy of 2001'' (2007)

Arthur C. Clarke Official Website

The Arthur C. Clarke Foundation

*

Arthur C. Clarke (1917–2008)

International Astronautical Federation * * * *

Grave

* * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Clarke, Arthur C. Arthur C. Clarke, 1917 births 2008 deaths 20th-century British screenwriters 20th-century English novelists 20th-century essayists 21st-century English novelists Alumni of King's College London Articles containing video clips British anti-capitalists British emigrants to Sri Lanka British gay writers Commanders of the Order of the British Empire Critics of religions Deaths from congestive heart failure Deaths from respiratory failure Early spaceflight scientists English atheists English essayists English humanists English inventors English sceptics English science fiction writers English underwater divers Fellows of King's College London Futurologists Hugo Award-winning writers Kalinga Prize recipients Knights Bachelor LGBT screenwriters LGBT writers from England Male essayists Nebula Award winners People from Minehead People with polio Pulp fiction writers Royal Air Force officers Royal Air Force personnel of World War II Science Fiction Hall of Fame inductees Search for extraterrestrial intelligence SFWA Grand Masters Space advocates Sri Lankabhimanya Vidya Jyothi Weird fiction writers Burials in Sri Lanka Military personnel from Somerset

futurist

Futurists (also known as futurologists, prospectivists, foresight practitioners and horizon scanners) are people whose specialty or interest is futurology or the attempt to systematically explore predictions and possibilities abou ...

, inventor, undersea explorer, and television series host.

He co-wrote the screenplay for the 1968 film '' 2001: A Space Odyssey'', widely regarded as one of the most influential films of all time. Clarke was a science fiction writer, an avid populariser of space travel, and a futurist of a distinguished ability. He wrote many books and many essays for popular magazines. In 1961, he received the Kalinga Prize

The Kalinga Prize for the Popularization of Science is an award given by UNESCO for exceptional skill in presenting scientific ideas to lay people. It was created in 1952, following a donation from Biju Patnaik, Founder President of the Kalinga ...

, a UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

award for popularising science. Clarke's science and science-fiction writings earned him the moniker

A nickname is a substitute for the proper name of a familiar person, place or thing. Commonly used to express affection, a form of endearment, and sometimes amusement, it can also be used to express defamation of character. As a concept, it is ...

"Prophet of the Space Age". His science-fiction writings in particular earned him a number of Hugo

Hugo or HUGO may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Hugo'' (film), a 2011 film directed by Martin Scorsese

* Hugo Award, a science fiction and fantasy award named after Hugo Gernsback

* Hugo (franchise), a children's media franchise based on a ...

and Nebula

A nebula ('cloud' or 'fog' in Latin; pl. nebulae, nebulæ or nebulas) is a distinct luminescent part of interstellar medium, which can consist of ionized, neutral or molecular hydrogen and also cosmic dust. Nebulae are often star-forming regio ...

awards, which along with a large readership, made him one of the towering figures of the genre. For many years Clarke, Robert Heinlein

Robert Anson Heinlein (; July 7, 1907 – May 8, 1988) was an American science fiction author, aeronautical engineer, and naval officer. Sometimes called the "dean of science fiction writers", he was among the first to emphasize scientific accu ...

, and Isaac Asimov

yi, יצחק אזימאװ

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Petrovichi, Russian SFSR

, spouse =

, relatives =

, children = 2

, death_date =

, death_place = Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

, nationality = Russian (1920–1922)Soviet (192 ...

were known as the "Big Three" of science fiction.

Clarke was a lifelong proponent of space travel. In 1934, while still a teenager, he joined the BIS, British Interplanetary Society

The British Interplanetary Society (BIS), founded in Liverpool in 1933 by Philip E. Cleator, is the oldest existing space advocacy organisation in the world. Its aim is exclusively to support and promote astronautics and space exploration.

Stru ...

. In 1945, he proposed a satellite

A satellite or artificial satellite is an object intentionally placed into orbit in outer space. Except for passive satellites, most satellites have an electricity generation system for equipment on board, such as solar panels or radioisotope ...

communication system using geostationary orbit

A geostationary orbit, also referred to as a geosynchronous equatorial orbit''Geostationary orbit'' and ''Geosynchronous (equatorial) orbit'' are used somewhat interchangeably in sources. (GEO), is a circular geosynchronous orbit in altitud ...

s. He was the chairman of the British Interplanetary Society from 1946 to 1947 and again in 1951–1953.

Clarke immigrated to Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

(now Sri Lanka) in 1956, to pursue his interest in scuba diving

Scuba diving is a mode of underwater diving whereby divers use breathing equipment that is completely independent of a surface air supply. The name "scuba", an acronym for "Self-Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus", was coined by Chris ...

. That year, he discovered the underwater ruins of the ancient original Koneswaram Temple in Trincomalee

Trincomalee (; ta, திருகோணமலை, translit=Tirukōṇamalai; si, ත්රිකුණාමළය, translit= Trikuṇāmaḷaya), also known as Gokanna and Gokarna, is the administrative headquarters of the Trincomalee Dis ...

. Clarke augmented his popularity in the 1980s, as the host of television shows such as ''Arthur C. Clarke's Mysterious World

''Arthur C. Clarke's Mysterious World'' is a thirteen-part British television series looking at unexplained phenomena from around the world. It was produced by Yorkshire Television for the ITV network and first broadcast on 6 September 1980.

...

''. He lived in Sri Lanka until his death.

Clarke was appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

(CBE) in 1989 "for services to British cultural interests in Sri Lanka". He was knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the Christian denomination, church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood ...

in 1998 and was awarded Sri Lanka's highest civil honour, Sri Lankabhimanya

Sri Lankabhimanya ( si, ශ්රී ලංකාභිමාන්ය, translit=Śrī Laṃkābhimānya; ta, சிறீ லங்காபிமான்ய, translit=Ciṟī Laṅkāpimāṉya; The Pride of Sri Lanka) is the highest n ...

, in 2005.

Biography

Early years

Clarke was born inMinehead

Minehead is a coastal town and civil parish in Somerset, England. It lies on the south bank of the Bristol Channel, north-west of the county town of Taunton, from the boundary with the county of Devon and in proximity of the Exmoor National P ...

, Somerset, England, and grew up in nearby Bishops Lydeard

Bishops Lydeard () is a village and civil parish located in Somerset, England, north-west of Taunton in the district of Somerset West and Taunton. The civil parish encompasses the hamlets of East Lydeard, Terhill, and East Bagborough, and had a ...

. As a boy, he lived on a farm, where he enjoyed stargazing

Amateur astronomy is a hobby where participants enjoy observing or imaging celestial objects in the sky using the unaided eye, binoculars, or telescopes. Even though scientific research may not be their primary goal, some amateur astronomers m ...

, fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

collecting, and reading American science-fiction pulp magazine

Pulp magazines (also referred to as "the pulps") were inexpensive fiction magazines that were published from 1896 to the late 1950s. The term "pulp" derives from the cheap wood pulp paper on which the magazines were printed. In contrast, magazine ...

s. He received his secondary education at Huish school in Taunton

Taunton () is the county town of Somerset, England, with a 2011 population of 69,570. Its thousand-year history includes a 10th-century monastic foundation, Taunton Castle, which later became a priory. The Normans built a castle owned by the ...

. Some of his early influences included dinosaur cigarette cards

Cigarette cards are trading cards issued by tobacco manufacturers to stiffen cigarette packaging and advertise cigarette brands.

Between 1875 and the 1940s, cigarette companies often included collectible cards with their packages of cigarette ...

, which led to an enthusiasm for fossils starting about 1925. Clarke attributed his interest in science fiction to reading three items: the November 1928 issue of ''Amazing Stories

''Amazing Stories'' is an American science fiction magazine launched in April 1926 by Hugo Gernsback's Experimenter Publishing. It was the first magazine devoted solely to science fiction. Science fiction stories had made regular appearances i ...

'' in 1929; ''Last and First Men

''Last and First Men: A Story of the Near and Far Future'' is a "future history" science fiction novel written in 1930 by the British author Olaf Stapledon. A work of unprecedented scale in the genre, it describes the history of humanity from t ...

'' by Olaf Stapledon

William Olaf Stapledon (10 May 1886 – 6 September 1950) – known as Olaf Stapledon – was a British philosopher and author of science fiction.Andy Sawyer, " illiamOlaf Stapledon (1886-1950)", in Bould, Mark, et al, eds. ''Fifty Key Figures ...

in 1930; and ''The Conquest of Space

''The Conquest of Space'' is a 1949 speculative science book written by Willy Ley and illustrated by Chesley Bonestell. The book contains a portfolio of paintings by Bonestell depicting the possible future exploration of the Solar System, with ex ...

'' by David Lasser

David Lasser (March 20, 1902 – May 5, 1996) was an American writer and political activist. Lasser is remembered as one of the most influential figures of early science fiction writing, working closely with Hugo Gernsback. He was also heavily in ...

in 1931.

In his teens, he joined the Junior Astronomical Association and contributed to ''Urania'', the society's journal, which was edited in Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

by Marion Eadie. At Clarke's request, she added an "Astronautics" section, which featured a series of articles written by him on spacecraft and space travel. Clarke also contributed pieces to the "Debates and Discussions Corner", a counterpoint to a ''Urania'' article offering the case against space travel, and also his recollections of the Walt Disney film ''Fantasia

Fantasia International Film Festival (also known as Fantasia-fest, FanTasia, and Fant-Asia) is a film festival that has been based mainly in Montreal since its founding in 1996. Regularly held in July of each year, it is valued by both hardcore ...

''. He moved to London in 1936 and joined the Board of Education

A board of education, school committee or school board is the board of directors or board of trustees of a school, local school district or an equivalent institution.

The elected council determines the educational policy in a small regional are ...

as a pensions auditor. He and some fellow science-fiction writers shared a flat in Gray's Inn Road

Gray's Inn Road (or Grays Inn Road) is an important road in the Bloomsbury district of Central London, in the London Borough of Camden. The road begins at the City of London boundary, where it bisects High Holborn, and ends at King's Cross and ...

, where he got the nickname "Ego" because of his absorption in subjects that interested him, and later named his office filled with memorabilia as his "ego chamber".

World War II

During theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

from 1941 to 1946, he served in the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

as a radar specialist and was involved in the early-warning radar

An early-warning radar is any radar system used primarily for the long-range detection of its targets, i.e., allowing defences to be alerted as ''early'' as possible before the intruder reaches its target, giving the air defences the maximum t ...

defence system, which contributed to the RAF's success during the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defende ...

. Clarke spent most of his wartime service working on ground-controlled approach

In aviation a ground-controlled approach (GCA), is a type of service provided by air-traffic controllers whereby they guide aircraft to a safe landing, including in adverse weather conditions, based on primary radar images. Most commonly a GCA uses ...

(GCA) radar, as documented in the semiautobiographical ''Glide Path

Instrument landing system glide path, commonly referred to as a glide path (G/P) or glide slope (G/S), is "a system of vertical guidance embodied in the instrument landing system which indicates the vertical deviation of the aircraft from its o ...

'', his only non-science-fiction novel. Although GCA did not see much practical use during the war, after several years of development it proved vital to the Berlin Airlift

The Berlin Blockade (24 June 1948 – 12 May 1949) was one of the first major international crises of the Cold War. During the multinational occupation of post–World War II Germany, the Soviet Union blocked the Western Allies' railway, road ...

of 1948–1949. Clarke initially served in the ranks and was a corporal

Corporal is a military rank in use in some form by many militaries and by some police forces or other uniformed organizations. The word is derived from the medieval Italian phrase ("head of a body"). The rank is usually the lowest ranking non ...

instructor on radar at No.2 Radio School, RAF Yatesbury

RAF Yatesbury is a former Royal Air Force airfield near the village of Yatesbury, Wiltshire, England, about east of the town of Calne. It was an important training establishment in the First and Second World Wars, and until its closure in 1965. ...

in Wiltshire. He was commissioned as a pilot officer

Pilot officer (Plt Off officially in the RAF; in the RAAF and RNZAF; formerly P/O in all services, and still often used in the RAF) is the lowest commissioned rank in the Royal Air Force and the air forces of many other Commonwealth countri ...

(technical branch) on 27 May 1943. He was promoted flying officer on 27 November 1943. He was appointed chief training instructor at RAF Honiley

Royal Air Force Honiley or RAF Honiley is a former Royal Air Force station located in Wroxall, Warwickshire, southwest of Coventry, England.

The station closed in March 1958, and after being used as a motor vehicle test track, it has been sub ...

in Warwickshire and was demobilised

Demobilization or demobilisation (see spelling differences) is the process of standing down a nation's armed forces from combat-ready status. This may be as a result of victory in war, or because a crisis has been peacefully resolved and militar ...

with the rank of flight lieutenant

Flight lieutenant is a junior commissioned rank in air forces that use the Royal Air Force (RAF) system of ranks, especially in Commonwealth countries. It has a NATO rank code of OF-2. Flight lieutenant is abbreviated as Flt Lt in the India ...

.

Post-war

After the war, he attained afirst-class degree

The British undergraduate degree classification system is a grading structure for undergraduate degrees or bachelor's degrees and integrated master's degrees in the United Kingdom. The system has been applied (sometimes with significant variati ...

in mathematics and physics from King's College London

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public research university located in London, England. King's was established by royal charter in 1829 under the patronage of King George IV and the Duke of Wellington. In 1836, King's ...

. After this, he worked as assistant editor at '' Physics Abstracts''. Clarke then served as president of the British Interplanetary Society

The British Interplanetary Society (BIS), founded in Liverpool in 1933 by Philip E. Cleator, is the oldest existing space advocacy organisation in the world. Its aim is exclusively to support and promote astronautics and space exploration.

Stru ...

from 1946 to 1947 and again from 1951 to 1953.

Although he was not the originator of the concept of geostationary satellite

A geostationary orbit, also referred to as a geosynchronous equatorial orbit''Geostationary orbit'' and ''Geosynchronous (equatorial) orbit'' are used somewhat interchangeably in sources. (GEO), is a circular geosynchronous orbit in altitude ...

s, one of his most important contributions in this field was his idea that they would be ideal telecommunications relays. He advanced this idea in a paper privately circulated among the core technical members of the British Interplanetary Society in 1945. The concept was published in ''Wireless World

''Electronics World'' (''Wireless World'', founded in 1913, and in September 1984 renamed ''Electronics & Wireless World'') is a technical magazine in electronics and RF engineering aimed at professional design engineers. It is produced monthly in ...

'' in October of that year. Clarke also wrote a number of nonfiction books describing the technical details and societal implications of rocketry and space flight. The most notable of these may be '' Interplanetary Flight: An Introduction to Astronautics'' (1950), ''The Exploration of Space'' (1951), and ''The Promise of Space'' (1968). In recognition of these contributions, the geostationary orbit

A geostationary orbit, also referred to as a geosynchronous equatorial orbit''Geostationary orbit'' and ''Geosynchronous (equatorial) orbit'' are used somewhat interchangeably in sources. (GEO), is a circular geosynchronous orbit in altitud ...

above the equator is officially recognised by the International Astronomical Union

The International Astronomical Union (IAU; french: link=yes, Union astronomique internationale, UAI) is a nongovernmental organisation with the objective of advancing astronomy in all aspects, including promoting astronomical research, outreac ...

as the Clarke Orbit

A geostationary orbit, also referred to as a geosynchronous equatorial orbit''Geostationary orbit'' and ''Geosynchronous (equatorial) orbit'' are used somewhat interchangeably in sources. (GEO), is a circular geosynchronous orbit in altitude ...

.

His 1951 book, ''The Exploration of Space'', was used by the rocket pioneer Wernher von Braun

Wernher Magnus Maximilian Freiherr von Braun ( , ; 23 March 191216 June 1977) was a German and American aerospace engineer and space architect. He was a member of the Nazi Party and Allgemeine SS, as well as the leading figure in the develop ...

to convince President John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination i ...

that it was possible to go to the Moon.

Following the 1968 release of ''2001'', Clarke became much in demand as a commentator on science and technology, especially at the time of the Apollo space program. On 20 July 1969, Clarke appeared as a commentator for the CBS News

CBS News is the news division of the American television and radio service CBS. CBS News television programs include the ''CBS Evening News'', ''CBS Mornings'', news magazine programs '' CBS News Sunday Morning'', '' 60 Minutes'', and '' 48 H ...

broadcast of the Apollo 11

Apollo 11 (July 16–24, 1969) was the American spaceflight that first landed humans on the Moon. Commander Neil Armstrong and lunar module pilot Buzz Aldrin landed the Apollo Lunar Module ''Eagle'' on July 20, 1969, at 20:17 UTC, an ...

Moon landing.

Sri Lanka and diving

Clarke lived in Sri Lanka from 1956 until his death in 2008, first inUnawatuna

Unawatuna is a coastal town in Galle district of Sri Lanka. Unawatuna is a major tourist attraction in Sri Lanka and known for its beach and corals. It is a suburb of Galle, about southeast to the city center and approximately south of Colomb ...

on the south coast, and then in Colombo

Colombo ( ; si, කොළඹ, translit=Koḷam̆ba, ; ta, கொழும்பு, translit=Koḻumpu, ) is the executive and judicial capital and largest city of Sri Lanka by population. According to the Brookings Institution, Colombo me ...

. Initially, he and his friend Mike Wilson travelled around Sri Lanka, diving in the coral waters around the coast with the Beachcombers Club. In 1957, during a dive trip off Trincomalee

Trincomalee (; ta, திருகோணமலை, translit=Tirukōṇamalai; si, ත්රිකුණාමළය, translit= Trikuṇāmaḷaya), also known as Gokanna and Gokarna, is the administrative headquarters of the Trincomalee Dis ...

, Clarke discovered the underwater ruins of a temple, which subsequently made the region popular with divers. He described it in his 1957 book ''The Reefs of Taprobane''. This was his second diving book after the 1956 ''The Coast of Coral''. Though Clarke lived mostly in Colombo, he set up a small dive school and a simple dive shop near Trincomalee. He dived often at Hikkaduwa

Hikkaduwa is a small town on the south coast of Sri Lanka located in the Southern Province, about north-west of Galle and south of Colombo.

Etymology

The name Hikkaduwa is thought to have been derived from the two words ''Sip Kaduwa'', with ' ...

, Trincomalee, and Nilaveli

Nilaveli ( ta, நிலாவெளி, translit=Nilāveḷi; si, නිල්වැල්ල, translit=Nilvælla) is a coastal resort town and suburb of the Trincomalee District, Sri Lanka located 16 km northwest of the city of Trincomalee ...

.

The Sri Lankan government offered Clarke resident guest status in 1975. He was held in such high esteem that when fellow science-fiction writer Robert A. Heinlein

Robert Anson Heinlein (; July 7, 1907 – May 8, 1988) was an American science fiction author, aeronautical engineer, and naval officer. Sometimes called the "dean of science fiction writers", he was among the first to emphasize scientific accu ...

came to visit, the Sri Lanka Air Force

The Sri Lanka Air Force (SLAF) ( si, ශ්රි ලංකා ගුවන් හමුදාව, Śrī Laṃkā guwan hamudāva; ta, இலங்கை விமானப்படை, Ilaṅkai vimāṉappaṭai) is the air arm and the yo ...

provided a helicopter

A helicopter is a type of rotorcraft in which lift and thrust are supplied by horizontally spinning rotors. This allows the helicopter to take off and land vertically, to hover, and to fly forward, backward and laterally. These attributes ...

to take them around the country.

In the early 1970s, Clarke signed a three-book publishing deal, a record for a science-fiction writer at the time. The first of the three was ''Rendezvous with Rama

''Rendezvous with Rama'' is a science fiction novel by British writer Arthur C. Clarke first published in 1973. Set in the 2130s, the story involves a cylindrical alien starship that enters the Solar System. The story is told from the ...

'' in 1973, which won all the main genre awards and spawned sequels that along with the ''2001'' series formed the backbone of his later career.

In 1986, Clarke was named a Grand Master by the

In 1986, Clarke was named a Grand Master by the Science Fiction Writers of America

The Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, doing business as Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association, commonly known as SFWA ( or ) is a nonprofit 501(c)(3) organization of professional science fiction and fantasy writers. While ...

.

In 1988, he was diagnosed with post-polio syndrome

Post-polio syndrome (PPS, poliomyelitis sequelae) is a group of latent symptoms of poliomyelitis (polio), occurring at about a 25–40% rate (latest data greater than 80%). These symptoms are caused by the damaging effects of the viral infection ...

, having originally contracted polio

Poliomyelitis, commonly shortened to polio, is an infectious disease caused by the poliovirus. Approximately 70% of cases are asymptomatic; mild symptoms which can occur include sore throat and fever; in a proportion of cases more severe s ...

in 1962, and needed to use a wheelchair

A wheelchair is a chair with wheels, used when walking is difficult or impossible due to illness, injury, problems related to old age, or disability. These can include spinal cord injuries ( paraplegia, hemiplegia, and quadriplegia), cerebr ...

most of the time thereafter. Clarke was for many years a vice-patron of the British Polio Fellowship

The British Polio Fellowship is a charitable organisation supporting and empowering people in the UK living with the late effects of polio and post-polio syndrome (PPS). It provides information, welfare and support to those affected, to enable ...

.

In the 1989 Queen's Birthday Honours

The Birthday Honours, in some Commonwealth realms, mark the reigning British monarch's official birthday by granting various individuals appointment into national or dynastic orders or the award of decorations and medals. The honours are present ...

, Clarke was appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

(CBE) "for services to British cultural interests in Sri Lanka". The same year, he became the first chancellor of the International Space University

The International Space University (ISU) is dedicated to the discovery, research, and development of outer space and its applications for peaceful purposes, through international and multidisciplinary education and research programs. ISU was f ...

, serving from 1989 to 2004. He also served as chancellor of Moratuwa University in Sri Lanka from 1979 to 2002.

In 1994, Clarke appeared in a science-fiction film

Science fiction (or sci-fi) is a film genre that uses speculative, fictional science-based depictions of phenomena that are not fully accepted by mainstream science, such as extraterrestrial lifeforms, spacecraft, robots, cyborgs, interstellar ...

; he portrayed himself in the telefilm '' Without Warning'', an American production about an apocalyptic alien first-contact scenario presented in the form of a faux newscast.

Clarke also became active in promoting the protection of gorillas and became a patron of the Gorilla Organization

Gorillas are herbivorous, predominantly ground-dwelling great apes that inhabit the tropical forests of equatorial Africa. The genus ''Gorilla'' is divided into two species: the eastern gorilla and the western gorilla, and either four or fi ...

, which fights for the preservation of gorillas. When tantalum

Tantalum is a chemical element with the symbol Ta and atomic number 73. Previously known as ''tantalium'', it is named after Tantalus, a villain in Greek mythology. Tantalum is a very hard, ductile, lustrous, blue-gray transition metal that is ...

mining for mobile phone manufacture threatened the gorillas in 2001, he lent his voice to their cause. The dive shop that he set up continues to operate from Trincomalee through the Arthur C Clarke Foundation.

Television series host

In the 1980s and early 1990s, Clarke presented his television programmes ''Arthur C. Clarke's Mysterious World

''Arthur C. Clarke's Mysterious World'' is a thirteen-part British television series looking at unexplained phenomena from around the world. It was produced by Yorkshire Television for the ITV network and first broadcast on 6 September 1980.

...

'', ''Arthur C. Clarke's World of Strange Powers

''Arthur C. Clarke's World of Strange Powers'' is a thirteen-part British television series looking at strange worlds of the paranormal. It was produced by ITV Yorkshire, Yorkshire Television for the ITV (TV network), ITV network and first broad ...

'', and ''Arthur C. Clarke's Mysterious Universe

''Arthur C. Clarke's Mysterious Universe'' is a popular 26-part television series looking at unexplained phenomena across the universe. It was first broadcast in the United Kingdom by independent television network Discovery Channel. It premiere ...

''.

Personal life

On a trip to Florida in 1953, Clarke met and quickly married Marilyn Mayfield, a 22-year-old American divorcee with a young son. They separated permanently after six months, although the divorce was not finalised until 1964.McAleer, Neil. "Arthur C. Clarke: The Authorized Biography", Contemporary Books, Chicago, 1992. "The marriage was incompatible from the beginning," said Clarke. Marilyn never remarried and died in 1991. Clarke himself also never remarried, but was close to a Sri Lankan man, Leslie Ekanayake (13 July 19474July 1977), whom Clarke called his "only perfect friend of a lifetime" in the dedication to his novel ''The Fountains of Paradise

''The Fountains of Paradise'' is a 1979 science fiction novel by British writer Arthur C. Clarke. Set in the 22nd century, it describes the construction of a space elevator. This "orbital tower" is a giant structure rising from the ground ...

''. Clarke is buried with Ekanayake, who predeceased him by three decades, in Colombo's central cemetery. In his biography of Stanley Kubrick

Stanley Kubrick (; July 26, 1928 – March 7, 1999) was an American film director, producer, screenwriter, and photographer. Widely considered one of the greatest filmmakers of all time, his films, almost all of which are adaptations of nove ...

, John Baxter cites Clarke's homosexuality as a reason why he relocated, due to more tolerant laws with regard to homosexuality in Sri Lanka. In 1998, the ''Sunday Mirror

The ''Sunday Mirror'' is the Sunday sister paper of the ''Daily Mirror''. It began life in 1915 as the ''Sunday Pictorial'' and was renamed the ''Sunday Mirror'' in 1963. In 2016 it had an average weekly circulation of 620,861, dropping marke ...

'' reported that he paid Sri Lankan boys for sex, leading to the cancellation of plans for Prince Charles to knight him on a visit to the country. The accusation was subsequently found to be baseless by the Sri Lankan police. Journalists who enquired of Clarke whether he was gay were told, "No, merely mildly cheerful." However, Michael Moorcock

Michael John Moorcock (born 18 December 1939) is an English writer, best-known for science fiction and fantasy, who has published a number of well-received literary novels as well as comic thrillers, graphic novels and non-fiction. He has work ...

wrote:

In an interview in the July 1986 issue of ''Playboy'' magazine, when asked if he had had a bisexual experience, Clarke stated, "Of course. Who hasn't?" In his obituary, Clarke's friend Kerry O'Quinn

Kerry O'Quinn is a writer, magazine publisher, director and producer, most noted for the creation of ''Starlog'', ''Fangoria'', ''Cinemagic'', ''Future Life'', Rock Video, Hard Rock and ''Comics Scene'' magazines.

Career

O'Quinn was a publisher ...

wrote: "Yes, Arthur was gay ... As Isaac Asimov

yi, יצחק אזימאװ

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Petrovichi, Russian SFSR

, spouse =

, relatives =

, children = 2

, death_date =

, death_place = Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

, nationality = Russian (1920–1922)Soviet (192 ...

once told me, 'I think he simply found he preferred men.' Arthur didn't publicise his sexualitythat wasn't the focus of his lifebut if asked, he was open and honest."

Clarke accumulated a vast collection of manuscripts and personal memoirs, maintained by his brother Fred Clarke in Taunton, Somerset, England, and referred to as the "Clarkives". Clarke said some of his private diaries will not be published until 30 years after his death. When asked why they were sealed, he answered, "Well, there might be all sorts of embarrassing things in them."

Knighthood

On 26 May 2000, he was made aKnight Bachelor

The title of Knight Bachelor is the basic rank granted to a man who has been knighted by the monarch but not inducted as a member of one of the organised orders of chivalry; it is a part of the British honours system. Knights Bachelor are the ...

"for services to literature" at a ceremony in Colombo. The award of a knighthood had been announced in the 1998 New Year Honours

The New Year Honours is a part of the British honours system, with New Year's Day, 1 January, being marked by naming new members of orders of chivalry and recipients of other official honours. A number of other Commonwealth realms also mark this ...

list, but investiture with the award had been delayed, at Clarke's request, because of an accusation by the British tabloid the ''Sunday Mirror'' of paying boys for sex. The charge was subsequently found to be baseless by the Sri Lankan police. According to ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was fo ...

'', the ''Mirror'' subsequently published an apology, and Clarke chose not to sue for defamation

Defamation is the act of communicating to a third party false statements about a person, place or thing that results in damage to its reputation. It can be spoken (slander) or written (libel). It constitutes a tort or a crime. The legal defini ...

. ''The Independent

''The Independent'' is a British online newspaper. It was established in 1986 as a national morning printed paper. Nicknamed the ''Indy'', it began as a broadsheet and changed to tabloid format in 2003. The last printed edition was publis ...

'' reported that a similar story was not published, allegedly because Clarke was a friend of newspaper tycoon Rupert Murdoch

Keith Rupert Murdoch ( ; born 11 March 1931) is an Australian-born American business magnate. Through his company News Corp, he is the owner of hundreds of local, national, and international publishing outlets around the world, including ...

. Clarke himself said, "I take an extremely dim view of people mucking about with boys", and Rupert Murdoch promised him the reporters responsible would never work in Fleet Street

Fleet Street is a major street mostly in the City of London. It runs west to east from Temple Bar at the boundary with the City of Westminster to Ludgate Circus at the site of the London Wall and the River Fleet from which the street was na ...

again. Clarke was then duly knighted.

Later years

Although he and his home were unharmed by the

Although he and his home were unharmed by the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake

An earthquake and a tsunami, known as the Boxing Day Tsunami and, by the scientific community, the Sumatra–Andaman earthquake, occurred at 07:58:53 local time (UTC+7) on 26 December 2004, with an epicentre off the west coast of northern Suma ...

tsunami, his "Arthur C. Clarke Diving School" (now called "Underwater Safaris") at Hikkaduwa

Hikkaduwa is a small town on the south coast of Sri Lanka located in the Southern Province, about north-west of Galle and south of Colombo.

Etymology

The name Hikkaduwa is thought to have been derived from the two words ''Sip Kaduwa'', with ' ...

near Galle was destroyed. He made humanitarian appeals, and the Arthur C. Clarke Foundation worked towards better disaster notification systems.

Because of his post-polio deficits, which limited his ability to travel and gave him Aphasia, halting speech, most of Clarke's communications in his last years were in the form of recorded addresses. In July 2007, he provided a video address for the Heinlein Centennial, Robert A. Heinlein Centennial in which he closed his comments with a goodbye to his fans. In September 2007, he provided a video greeting for NASA's Cassini-Huygens, Cassini probe's flyby of Iapetus (moon), Iapetus (which plays an important role in the book of ''2001: A Space Odyssey (novel), 2001: A Space Odyssey''). In December 2007 on his 90th birthday, Clarke recorded a video message to his friends and fans bidding them good-bye.

Clarke died in Colombo on 19 March 2008, at the age of 90. His aide described the cause as respiratory complications and heart failure stemming from post-polio syndrome.

Just hours before Clarke's death, a major gamma-ray burst (GRB) reached Earth. Known as GRB 080319B, the burst set a new record as the farthest object that can be seen from Earth with the naked eye. It occurred about 7.5 billion years ago, the light taking that long to reach Earth. Larry Sessions, a science writer for ''Sky and Telescope'' magazine blogging on earthsky.org, suggested that the burst be named the "Clarke Event". ''American Atheist Magazine ''wrote of the idea: "It would be a fitting tribute to a man who contributed so much, and helped lift our eyes and our minds to a cosmos once thought to be province only of gods."

A few days before he died, he had reviewed the manuscript of his final work, ''The Last Theorem'', on which he had collaborated by e-mail with contemporary Frederik Pohl. The book was published after Clarke's death. Clarke was buried alongside his partner, Leslie Ekanayake, in Colombo

Colombo ( ; si, කොළඹ, translit=Koḷam̆ba, ; ta, கொழும்பு, translit=Koḻumpu, ) is the executive and judicial capital and largest city of Sri Lanka by population. According to the Brookings Institution, Colombo me ...

in traditional Sri Lankan fashion on 22 March. His younger brother, Fred Clarke, and his Sri Lankan adoptive family were among the thousands in attendance.

Clarke's papers were donated to the National Air and Space Museum in 2014.

Science-fiction writer

Beginnings

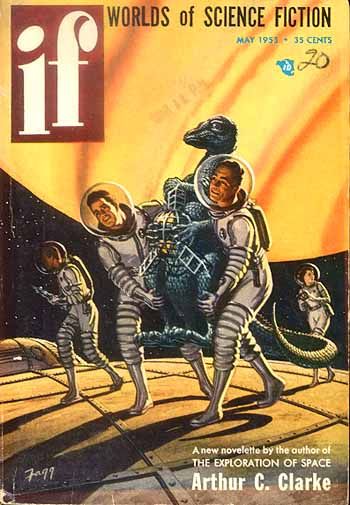

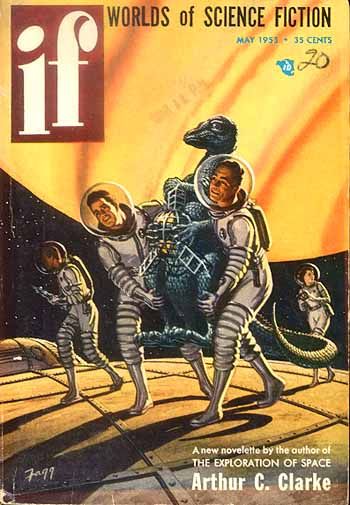

While Clarke had a few stories published in fanzines, between 1937 and 1945, his first professional sale appeared in ''Astounding Science Fiction'' in 1946: "Loophole (short story), Loophole" was published in April, while "Rescue Party (short story), Rescue Party", his first sale, was published in May. Along with his writing, Clarke briefly worked as assistant editor of ''Science Abstracts'' (1949) before devoting himself in 1951 to full-time writing. Clarke began carving out his reputation as a "scientific" science-fiction writer with his first science-fiction novel, ''Against the Fall of Night'', published as a novella in 1948. It was very popular and considered ground-breaking work for some of the concepts it contained. Clarke revised and expanded the novella into a full novel, which was published in 1953. Clarke later rewrote and expanded this work a third time to become ''The City and the Stars'' in 1956, which rapidly became a definitive must-read in the field. His third science-fiction novel, ''Childhood's End'', was also published in 1953, cementing his popularity. Clarke capped the first phase of his writing career with his sixth novel, ''A Fall of Moondust'', in 1961, which is also an acknowledged classic of the period. During this time, Clarke corresponded with C. S. Lewis in the 1940s and 1950s and they once met in an Oxford pub, Eastgate Hotel, the Eastgate, to discuss science fiction and space travel. Clarke voiced great praise for Lewis upon his death, saying the The Space Trilogy, Ransom trilogy was one of the few works of science fiction that should be considered literature."The Sentinel"

In 1948, he wrote "The Sentinel (short story), The Sentinel" for a BBC competition. Though the story was rejected, it changed the course of Clarke's career. Not only was it the basis for ''2001: A Space Odyssey'', but "The Sentinel" also introduced a more cosmic element to Clarke's work. Many of Clarke's later works feature a technologically advanced but still-prejudiced mankind being confronted by a superior alien intelligence. In the cases of ''Childhood's End'', and the ''2001'' series, this encounter produces a conceptual breakthrough that accelerates humanity into the next stage of its evolution. This also applies in the far-distant past (but our future) in ''The City and the Stars'' (and its original version, ''Against the Fall of Night'').

In Clarke's authorised biography, Neil McAleer writes: "many readers and critics still consider ''Childhood's End'' Arthur C. Clarke's best novel." But Clarke did not use Extrasensory perception, ESP in any of his later stories, saying, "I've always been interested in ESP, and of course, ''Childhood's End ''was about that. But I've grown disillusioned, partly because after all this time, they're still arguing about whether these things happen. I suspect that telepathy does happen."

A collection of early essays was published in ''The View from Serendip'' (1977), which also included one short piece of fiction, "When the Twerms Came". Clarke also wrote short stories under the pseudonyms of E. G. O'Brien and Charles Willis. Almost all of his short stories can be found in the book ''The Collected Stories of Arthur C. Clarke'' (2001).

In 1948, he wrote "The Sentinel (short story), The Sentinel" for a BBC competition. Though the story was rejected, it changed the course of Clarke's career. Not only was it the basis for ''2001: A Space Odyssey'', but "The Sentinel" also introduced a more cosmic element to Clarke's work. Many of Clarke's later works feature a technologically advanced but still-prejudiced mankind being confronted by a superior alien intelligence. In the cases of ''Childhood's End'', and the ''2001'' series, this encounter produces a conceptual breakthrough that accelerates humanity into the next stage of its evolution. This also applies in the far-distant past (but our future) in ''The City and the Stars'' (and its original version, ''Against the Fall of Night'').

In Clarke's authorised biography, Neil McAleer writes: "many readers and critics still consider ''Childhood's End'' Arthur C. Clarke's best novel." But Clarke did not use Extrasensory perception, ESP in any of his later stories, saying, "I've always been interested in ESP, and of course, ''Childhood's End ''was about that. But I've grown disillusioned, partly because after all this time, they're still arguing about whether these things happen. I suspect that telepathy does happen."

A collection of early essays was published in ''The View from Serendip'' (1977), which also included one short piece of fiction, "When the Twerms Came". Clarke also wrote short stories under the pseudonyms of E. G. O'Brien and Charles Willis. Almost all of his short stories can be found in the book ''The Collected Stories of Arthur C. Clarke'' (2001).

"Big Three"

For much of the later 20th century, Clarke,

For much of the later 20th century, Clarke, Isaac Asimov

yi, יצחק אזימאװ

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Petrovichi, Russian SFSR

, spouse =

, relatives =

, children = 2

, death_date =

, death_place = Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

, nationality = Russian (1920–1922)Soviet (192 ...

, and Robert A. Heinlein

Robert Anson Heinlein (; July 7, 1907 – May 8, 1988) was an American science fiction author, aeronautical engineer, and naval officer. Sometimes called the "dean of science fiction writers", he was among the first to emphasize scientific accu ...

were informally known as the "Big Three" of science-fiction writers. Clarke and Heinlein began writing to each other after ''The Exploration of Space'' was published in 1951, and first met in person the following year. They remained on cordial terms for many years, including during visits to the United States and Sri Lanka.

Clarke and Asimov first met in New York City in 1953, and they traded friendly insults and gibes for decades. They established an oral agreement, the "Clarke–Asimov Treaty", that when asked who was better, the two would say Clarke was the better science-fiction writer and Asimov was the better science writer. In 1972, Clarke put the "treaty" on paper in his dedication to ''Report on Planet Three and Other Speculations''.

In 1984, Clarke testified before Congress against the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI). Later, at the home of Larry Niven in California, a concerned Heinlein attacked Clarke's views on United States foreign and space policy (especially the SDI), vigorously advocating a strong defence posture. Although the two later reconciled formally, they remained distant until Heinlein's death in 1988.

''2001'' series of novels

''2001: A Space Odyssey'', Clarke's most famous work, was extended well beyond the 1968 movie as the Space Odyssey series. In 1982, Clarke wrote a sequel to ''2001'' titled ''2010: Odyssey Two'', which was 2010 (film), made into a film in 1984. Clarke wrote two further sequels which have not been adapted into motion pictures: ''2061: Odyssey Three'' (published in 1987) and ''3001: The Final Odyssey'' (published in 1997). ''2061: Odyssey Three'' involves a visit to Halley's Comet on its next plunge through the Inner Solar System and a spaceship crash on the Jovian moon Europa (moon), Europa. The whereabouts of astronaut Dave Bowman (the "Star Child"), the artificial intelligence HAL 9000, and the development of native life on Europa, protected by the alien monolith (Space Odyssey), Monolith, are revealed. Finally, in ''3001: The Final Odyssey'', Frank Poole (astronaut), astronaut Frank Poole's freeze-dried body, found by a spaceship beyond the orbit of Neptune, is revived by advanced medical science. The novel details the threat posed to humanity by the alien monoliths, whose actions are not always as their builders had intended.''2001: A Space Odyssey''

Clarke's first venture into film was '' 2001: A Space Odyssey'', directed byStanley Kubrick

Stanley Kubrick (; July 26, 1928 – March 7, 1999) was an American film director, producer, screenwriter, and photographer. Widely considered one of the greatest filmmakers of all time, his films, almost all of which are adaptations of nove ...

. Kubrick and Clarke had met in New York City in 1964 to discuss the possibility of a collaborative film project. As the idea developed, they decided to loosely base the story on Clarke's short story, "The Sentinel (short story), The Sentinel", written in 1948 as an entry in a BBC short-story competition. Originally, Clarke was going to write the screenplay for the film, but Kubrick suggested during one of their brainstorming meetings that before beginning on the actual script, they should let their imaginations soar free by writing a novel first, on which they would base the film. "This is more or less the way it worked out, though toward the end, novel and screenplay were being written simultaneously, with feedback in both directions. Thus, I rewrote some sections after seeing the movie rushesa rather expensive method of literary creation, which few other authors can have enjoyed." The novel ended up being published a few months after the release of the movie.

Due to the hectic schedule of the film's production, Kubrick and Clarke had difficulty collaborating on the book. Clarke completed a draft of the novel at the end of 1964 with the plan to publish in 1965 in advance of the film's release in 1966. After many delays, the film was released in the spring of 1968, before the book was completed. The book was credited to Clarke alone. Clarke later complained that this had the effect of making the book into a 2001: A Space Odyssey (novel), novelisation, and that Kubrick had manipulated circumstances to downplay Clarke's authorship. For these and other reasons, the details of the story differ slightly from the book to the movie. The film contains little explanation for the events taking place. Clarke, though, wrote thorough explanations of "cause and effect" for the events in the novel. James Randi later recounted that upon seeing the premiere of ''2001'', Clarke left the theatre at the intermission in tears, after having watched an eleven-minute scene (which did not make it into general release) where an astronaut is doing nothing more than jogging inside the spaceship, which was Kubrick's idea of showing the audience how boring space travels could be.

In 1972, Clarke published ''The Lost Worlds of 2001'', which included his accounts of the production, and alternative versions of key scenes. The "special edition" of the novel ''2001: A Space Odyssey (novel), A Space Odyssey'' (released in 1999) contains an introduction by Clarke in which he documents the events leading to the release of the novel and film.

''2010: Odyssey Two''

In 1982, Clarke continued the ''2001'' epic with a sequel, ''2010: Odyssey Two''. This novel was also made into a film, ''2010 (film), 2010'', directed by Peter Hyams for release in 1984. Because of the political environment in America in the 1980s, the film presents a Cold War theme, with the looming tensions of nuclear warfare not featured in the novel. The film was not considered to be as revolutionary or artistic as ''2001'', but the reviews were still positive. Clarke's email correspondence with Hyams was published in 1984. Titled ''The Odyssey File: The Making of 2010'', and co-authored with Hyams, it illustrates his fascination with the then-pioneering medium of email and its use for them to communicate on an almost daily basis at the time of planning and production of the film while living on opposite sides of the world. The book also included Clarke's personal list of the best science-fiction films ever made. Clarke appeared in the film, first as the man feeding the pigeons while Heywood R. Floyd, Dr. Heywood Floyd is engaged in a conversation in front of the White House. Later, in the hospital scene with David Bowman (Space Odyssey), David Bowman's mother, an image of the cover of ''Time (magazine), Time'' portrays Clarke as the American President and Kubrick as the Soviet Premier.''Rendezvous with Rama''

Clarke's award-winning novel ''Rendezvous with Rama

''Rendezvous with Rama'' is a science fiction novel by British writer Arthur C. Clarke first published in 1973. Set in the 2130s, the story involves a cylindrical alien starship that enters the Solar System. The story is told from the ...

'' (1973) was option (filmmaking), optioned for filmmaking in the early 21st century but this motion picture was in "development hell" . In the early 2000s, actor Morgan Freeman expressed his desire to produce a movie based on ''Rendezvous with Rama''. After a drawn-out development process, which Freeman attributed to difficulties in getting financing, it appeared in 2003 that this project might be proceeding, but this was very dubious. The film was to be produced by Freeman's production company, Revelations Entertainment, and David Fincher has been touted on Revelations' ''Rama'' web page as far back as 2001 as the film's director. After years of no progress, Fincher stated in an interview in late 2007 (in which he also opined the novel as being influential on the films ''Alien (film), Alien'' and ''Star Trek: The Motion Picture'') that he is still attached to helm. Revelations indicated that Stel Pavlou had written the adaptation.

In late 2008, Fincher stated the movie is unlikely to be made. "It looks like it's not going to happen. There's no script and as you know, Morgan Freeman's not in the best of health right now. We've been trying to do it but it's probably not going to happen." In 2010, though, the film was announced as still planned for future production and both Freeman and Fincher mentioned it as still needing a worthy script.

In late 2021, it was announced that Denis Villeneuve would direct the adaptation of ''Rendezvous with Rama'', following the successful and critically praised release of Dune (2021 film), Villeneuve's adaption of Frank Herbert's ''Dune (novel), Dune''. Freeman is listed as a producer.

Science writer

Clarke published a number of nonfiction books with essays, speeches, addresses, etc. Several of his nonfiction books are composed of chapters that can stand on their own as separate essays.Space travel

In particular, Clarke was a populariser of the concept of space travel. In 1950, he wrote ''Interplanetary Flight'', a book outlining the basics of space flight for laymen. Later books about space travel included ''The Exploration of Space'' (1951), ''The Challenge of the Spaceship'' (1959), ''Voices from the Sky'' (1965), ''The Promise of Space'' (1968, rev. ed. 1970), and ''Report on Planet Three'' (1972) along with many others.Futurism

His books on space travel usually included chapters about other aspects of science and technology, such as computers and bioengineering. He predicted telecommunication satellites (albeit serviced by astronauts in space suits, who would replace the satellite's vacuum tubes as they burned out). His many predictions culminated in 1958 when he began a series of magazine essays which eventually became ''Profiles of the Future,'' published in book form in 1962. A timetable up to the year 2100 describes inventions and ideas including such things as a "global library" for 2005. The same work also contained "Clarke's First Law" and text that became Clarke's three laws in later editions. In a 1959 essay, Clarke predicted global satellite TV broadcasts that would cross national boundaries indiscriminately and would bring hundreds of channels available anywhere in the world. He also envisioned a "personal transceiver, so small and compact that every man carries one". He wrote: "the time will come when we will be able to call a person anywhere on Earth merely by dialing a number." Such a device would also, in Clarke's vision, include means for global positioning so "no one need ever again be lost". Later, in ''Profiles of the Future'', he predicted the advent of such a device taking place in the mid-1980s. Clarke described a global computer network similar to the modern World Wide Web in a 1964 presentation for the BBC Television, BBC's ''Horizon (British TV series), Horizon'' programme, predicting that, by the 21st century, access to information and even physical tasks such as surgery could be accomplished remotely and instantaneously from anywhere in the world using internet and satellite communication. In a 1974 interview with the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, the interviewer asked Clarke how he believed the computer would change the future for the everyday person, and what life would be like in the year 2001. Clarke accurately predicted many things that became reality, including online banking, online shopping, and other now commonplace things. Responding to a question about how the interviewer's son's life would be different, Clarke responded: "He will have, in his own house, not a computer as big as this, [points to nearby computer], but at least, a console through which he can talk, through his friendly local computer and get all the information he needs, for his everyday life, like his bank statements, his theatre reservations, all the information you need in the course of living in our complex modern society, this will be in a compact form in his own house ... and he will take it as much for granted as we take the telephone." An extensive selection of Clarke's essays and book chapters (from 1934 to 1998; 110 pieces, 63 of them previously uncollected in his books) can be found in the book ''Greetings, Carbon-Based Bipeds!'' (2000), together with a new introduction and many prefatory notes. Another collection of essays, all previously collected, is ''By Space Possessed'' (1993). Clarke's technical papers, together with several essays and extensive autobiographical material, are collected in ''Ascent to Orbit: A Scientific Autobiography'' (1984).Geostationary communications satellite

Clarke contributed to the popularity of the idea that

Clarke contributed to the popularity of the idea that geostationary satellite

A geostationary orbit, also referred to as a geosynchronous equatorial orbit''Geostationary orbit'' and ''Geosynchronous (equatorial) orbit'' are used somewhat interchangeably in sources. (GEO), is a circular geosynchronous orbit in altitude ...

s would be ideal telecommunications relays. He first described this in a letter to the editor of ''Wireless World

''Electronics World'' (''Wireless World'', founded in 1913, and in September 1984 renamed ''Electronics & Wireless World'') is a technical magazine in electronics and RF engineering aimed at professional design engineers. It is produced monthly in ...

'' in February 1945 and elaborated on the concept in a paper titled ''Extra-Terrestrial RelaysCan Rocket Stations Give Worldwide Radio Coverage?'', published in ''Wireless World'' in October 1945. The geostationary orbit

A geostationary orbit, also referred to as a geosynchronous equatorial orbit''Geostationary orbit'' and ''Geosynchronous (equatorial) orbit'' are used somewhat interchangeably in sources. (GEO), is a circular geosynchronous orbit in altitud ...

is sometimes known as the Clarke Orbit or the Clarke Belt in his honour.

It is not clear that this article was actually the inspiration for the modern telecommunications satellite. According to John R. Pierce, of Bell Labs, who was involved in the Echo satellite and Telstar projects, he gave a talk upon the subject in 1954 (published in 1955), using ideas that were "in the air", but was not aware of Clarke's article at the time. In an interview given shortly before his death, Clarke was asked whether he had ever suspected that one day communications satellites would become so important; he replied: "I'm often asked why I didn't try to patent the idea of a communications satellite. My answer is always, 'A patent is really a licence to be sued.

Though different from Clarke's idea of telecom relay, the idea of communicating via satellites in geostationary orbit itself had been described earlier. For example, the concept of geostationary satellites was described in Hermann Oberth's 1923 book ''Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen'' (''The Rocket into Interplanetary Space''), and then the idea of radio communication by means of those satellites in Herman Potočnik's (written under the pseudonym Hermann Noordung) 1928 book ''Das Problem der Befahrung des Weltraumsder Raketen-MotorThe Problem of Space TravelThe Rocket Motor

'', sections: ''Providing for Long Distance Communications and Safety'', and (possibly referring to the idea of relaying messages via satellite, but not that three would be optimal) ''Observing and Researching the Earth's Surface'', published in Berlin. Clarke acknowledged the earlier concept in his book ''Profiles of the Future''.

Undersea explorer

Clarke was an avid scuba diver and a member of the Underwater Explorers Club. In addition to writing, Clarke set up several diving-related ventures with his business partner Mike Wilson. In 1956, while scuba diving, Wilson and Clarke uncovered ruined masonry, architecture, and idol images of the sunken original Koneswaram templeincluding carved columns with flower insignia, and stones in the form of elephant headsspread on the shallow surrounding seabed. Other discoveries included Chola art, Chola bronzes from the original shrine, and these discoveries were described in Clarke's 1957 book ''The Reefs of Taprobane''. In 1961, while filming off Great Basses Reef, Wilson found a Great Basses wreck, wreck and retrieved silver coins. Plans to dive on the wreck the following year were stopped when Clarke developed paralysis, ultimately diagnosed as polio. A year later, Clarke observed the salvage from the shore and the surface. The ship, ultimately identified as belonging to the Mughal Empire, Mughal Emperor, Aurangzeb, yielded fused bags of silver rupees, cannon, and other artefacts, carefully documented, became the basis for ''The Treasure of the Great Reef''. Living in Sri Lanka and learning its history also inspired the backdrop for his novel ''The Fountains of Paradise

''The Fountains of Paradise'' is a 1979 science fiction novel by British writer Arthur C. Clarke. Set in the 22nd century, it describes the construction of a space elevator. This "orbital tower" is a giant structure rising from the ground ...

'' in which he described a space elevator. This, he believed, would make rocket-based access to space obsolete, and more than geostationary satellites, would ultimately be his scientific legacy.Personal e-mail from Sir Arthur Clarke to Jerry Stone, Director of the Sir Arthur Clarke Awards, 1November 2006 In 2008, he said in an interview with IEEE Spectrum, "maybe in a generation or so the space elevator will be considered equally important" as the geostationary satellite, which was his most important technological contribution.

Views

Religion

Themes of religion and spirituality appear in much of Clarke's writing. He said: "Any path to knowledge is a path to Godor Reality, whichever word one prefers to use." He described himself as "fascinated by the concept of God". J. B. S. Haldane, J. B. S. Haldane, near the end of his life, suggested in a personal letter to Clarke that Clarke should receive a prize in theology for being one of the few people to write anything new on the subject, and went on to say that if Clarke's writings had not contained multiple contradictory theological views, he might have been a menace. When he entered the Royal Air Force, Clarke insisted that his dog tags be marked "pantheism, pantheist" rather than the default, Church of England, and in a 1991 essay entitled "Credo", described himself as a logical positivism, logical positivist from the age of 10. In 2000, Clarke told the Sri Lankan newspaper, ''The Island'', "I don't believe in God or an afterlife," and he identified himself as an atheist. He was honoured as a Humanist Laureate in the International Academy of Humanism. He has also described himself as a "crypto-Buddhist", insisting Buddhism is not a religion. He displayed little interest about religion early in his life, for example, only discovering a few months after marrying that his wife had strong Presbyterian beliefs. A famous quotation of Clarke's is often cited: "One of the great tragedies of mankind is that morality has been hijacked by religion." He was quoted in ''Popular Science'' in 2004 as saying of religion: "Most malevolent and persistent of all mind viruses. We should get rid of it as quick as we can." In a three-day "dialogue on man and his world" with Alan Watts, Clarke said he was biased against religion and could not forgive religions for what he perceived as their inability to prevent atrocities and wars over time. In his introduction to the penultimate episode of ''Mysterious World'', entitled "Strange Skies", Clarke said: "I sometimes think that the universe is a machine designed for the perpetual astonishment of astronomers," reflecting the dialogue of the episode, in which he stated this concept more broadly, referring to "mankind". Near the very end of that same episode, the last segment of which covered the Star of Bethlehem, he said his favourite theory was that it might be a pulsar. Given that pulsars were discovered in the interval between his writing the short story, "The Star (Clarke short story), The Star" (1955), and making ''Mysterious World'' (1980), and given the more recent discovery of pulsar PSR B1913+16, he said: "How romantic, if even now, we can hear the dying voice of a star, which heralded the Christian era." Despite his atheism, themes of deism are a common feature within Clarke's work. Clarke left written instructions for a funeral: "Absolutely no religious rites of any kind, relating to any religious faith, should be associated with my funeral."Politics

Regarding freedom of information Clarke believed, "In the struggle for freedom of information, technology, not politics, will be the ultimate decider." Clarke also wrote, "It is not easy to see how the more extreme forms of nationalism can long survive when men have seen the Earth in its true perspective as a single small globe against the stars." Clarke opposed claims of sovereignty over space stating "There is hopeful symbolism in the fact that flags do not wave in a vacuum." Clarke was an Anti-capitalism, anti-capitalist, stating that he did not fear automation because, "the goal of the future is full unemployment, so we can play. That's why we have to destroy the present politico-economic system."Technology

Regarding human jobs being replaced by robots, Clarke said: "Any teacher that can be replaced by a machine should be!" Clarke supported the use of renewable energy, saying: "I would like to see us kick our current addiction to oil, and adopt clean energy sources... Climate change has now added a new sense of urgency. Our civilisation depends on energy, but we can't allow oil and coal to slowly bake our planet."Intelligent life

Clarke believed:Paranormal phenomena

Early in his career, Clarke had a fascination with the paranormal and said it was part of the inspiration for his novel ''Childhood's End''. Citing the numerous promising paranormal claims that were later shown to be fraudulent, Clarke described his earlier openness to the paranormal having turned to being "an almost total sceptic" by the time of his 1992 biography. Similarly, in the prologue to the 1990 Del Rey edition of ''Childhood's End'', he writes "...after ... researching my ''Mysterious World'' and ''Strange Powers'' programmes, I am an almost total skeptic. I have seen far too many claims dissolve into thin air, far too many demonstrations exposed as fakes. It has been a long, and sometimes embarrassing, learning process."''Childhood's End'', Del Rey, New York, 1990, pp. v During interviews, both in 1993 and 2004–2005, he stated that he did not believe in reincarnation, saying there was no mechanism to make it possible, though "I'm always paraphrasing J. B. S. Haldane: 'The universe is not only stranger than we imagine, it's stranger than we ''can'' imagine.'" He described the idea of reincarnation as fascinating, but favoured a finite existence. Clarke was known for hosting several television series investigating the unusual: ''Arthur C. Clarke's Mysterious World'' (1980), ''Arthur C. Clarke's World of Strange Power'' (1985), and ''Arthur C. Clarke's Mysterious Universe'' (1994). Topics examined ranged from ancient, man-made artifacts with obscure origins (e.g., the Nazca lines or Stonehenge), to cryptids (purported animals unknown to science), or obsolete scientific theories that came to have alternate explanations (e.g., Martian canals). In ''Arthur C. Clarke's Mysterious World'', he describes three kinds of "mysteries": * Mysteries of the First Kind: Something that was once utterly baffling but is now completely understood, e.g. a rainbow. * Mysteries of the Second Kind: Something that is currently not fully understood and can be in the future. * Mysteries of the Third Kind: Something of which we have no understanding. Clarke's programmes on unusual phenomena were parodied Big Foot (Goodies episode), in a 1982 episode of the comedy series ''The Goodies (TV series), The Goodies'', in which his show is cancelled after it is claimed that he does not exist.Themes, style, and influences

Clarke's work is marked by an optimistic view of science empowering mankind's exploration of the Solar System and the world's oceans. His images of the future often feature a Utopian setting with highly developed technology, ecology, and society, based on the author's ideals. His early published stories usually featured the extrapolation of a technological innovation or scientific breakthrough into the underlying decadence of his own society. A recurring theme in Clarke's works is the notion that the evolution of an intelligent species would eventually make them something close to gods. This was explored in his 1953 novel ''Childhood's End'' and briefly touched upon in his novel ''Imperial Earth''. This idea of transcendence through evolution seems to have been influenced byOlaf Stapledon

William Olaf Stapledon (10 May 1886 – 6 September 1950) – known as Olaf Stapledon – was a British philosopher and author of science fiction.Andy Sawyer, " illiamOlaf Stapledon (1886-1950)", in Bould, Mark, et al, eds. ''Fifty Key Figures ...

, who wrote a number of books dealing with this theme. Clarke has said of Stapledon's 1930 book ''Last and First Men

''Last and First Men: A Story of the Near and Far Future'' is a "future history" science fiction novel written in 1930 by the British author Olaf Stapledon. A work of unprecedented scale in the genre, it describes the history of humanity from t ...

'' that "No other book had a greater influence on my life ... [It] and its successor ''Star Maker'' (1937) are the twin summits of [Stapledon's] literary career."

Clarke was also well known as an admirer of Irish fantasy writer Edward Plunkett, 18th Baron of Dunsany, Lord Dunsany, also having corresponded with him until Dunsany's death in 1957. He described Dunsany as "one of the greatest writers of the century".

He also listed H. G. Wells, Jules Verne, and Edgar Rice Burroughs as influences.

Awards, honours, and other recognition

Clarke won the 1963 Stuart Ballantine Medal from the Franklin Institute for the concept of satellite communications, and other honours. He won more than a dozen annual literary awards for particular works of science fiction. * In 1956, Clarke won a Hugo Award for his short story, "The Star (Clarke short story), The Star". * Clarke won theUNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

–Kalinga Prize

The Kalinga Prize for the Popularization of Science is an award given by UNESCO for exceptional skill in presenting scientific ideas to lay people. It was created in 1952, following a donation from Biju Patnaik, Founder President of the Kalinga ...

for the Popularization of Science in 1961.

* He won the Stuart Ballantine Medal in 1963.

* Shared a 1969 Academy Award nomination with Stanley Kubrick

Stanley Kubrick (; July 26, 1928 – March 7, 1999) was an American film director, producer, screenwriter, and photographer. Widely considered one of the greatest filmmakers of all time, his films, almost all of which are adaptations of nove ...

in the category Best Writing, Story and ScreenplayWritten Directly for the Screen for '' 2001: A Space Odyssey''.

* The fame of ''2001'' was enough for the Apollo command module, Command Module of the Apollo 13 craft to be named "Odyssey".

* Clarke won the Nebula

A nebula ('cloud' or 'fog' in Latin; pl. nebulae, nebulæ or nebulas) is a distinct luminescent part of interstellar medium, which can consist of ionized, neutral or molecular hydrogen and also cosmic dust. Nebulae are often star-forming regio ...

(1973) for his novella, "A Meeting with Medusa".

* Clarke won both the Nebula

A nebula ('cloud' or 'fog' in Latin; pl. nebulae, nebulæ or nebulas) is a distinct luminescent part of interstellar medium, which can consist of ionized, neutral or molecular hydrogen and also cosmic dust. Nebulae are often star-forming regio ...

(1973) and Hugo

Hugo or HUGO may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Hugo'' (film), a 2011 film directed by Martin Scorsese

* Hugo Award, a science fiction and fantasy award named after Hugo Gernsback

* Hugo (franchise), a children's media franchise based on a ...

(1974) awards for his novel, ''Rendezvous with Rama

''Rendezvous with Rama'' is a science fiction novel by British writer Arthur C. Clarke first published in 1973. Set in the 2130s, the story involves a cylindrical alien starship that enters the Solar System. The story is told from the ...

''.

* Clarke won both the Nebula