Ancient South Arabian art on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ancient South Arabian art was the art of the Pre-Islamic cultures of

Ancient South Arabian art was the art of the Pre-Islamic cultures of

Old Arabian art experienced its first flourishing at the beginning of the 1st millennium BC at the time of the South Arabian classical culture, centred on the kingdoms of the Sabaeans and Minaeans in modern Yemen. The 5th century BC marked the golden age of Saba, whose main centres were

Old Arabian art experienced its first flourishing at the beginning of the 1st millennium BC at the time of the South Arabian classical culture, centred on the kingdoms of the Sabaeans and Minaeans in modern Yemen. The 5th century BC marked the golden age of Saba, whose main centres were

Unlike Mesopotamia, ancient South Arabia was dominated by stone buildings. Only in the coastal areas and the Hadhramaut capital of

Unlike Mesopotamia, ancient South Arabia was dominated by stone buildings. Only in the coastal areas and the Hadhramaut capital of

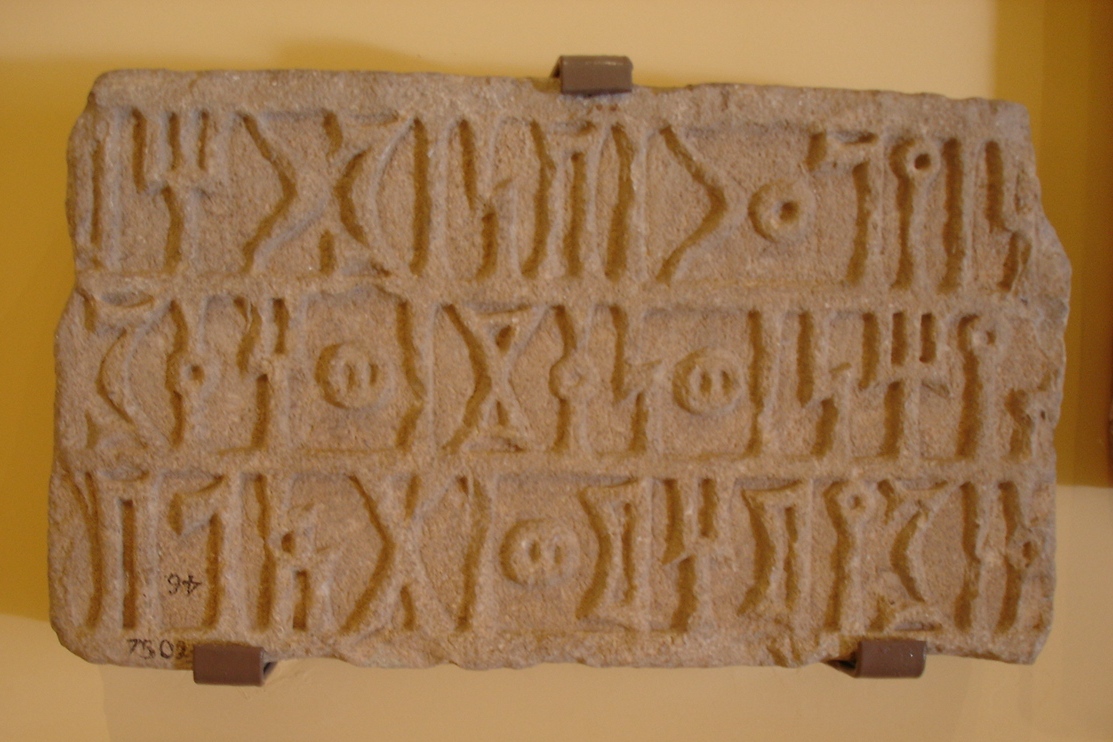

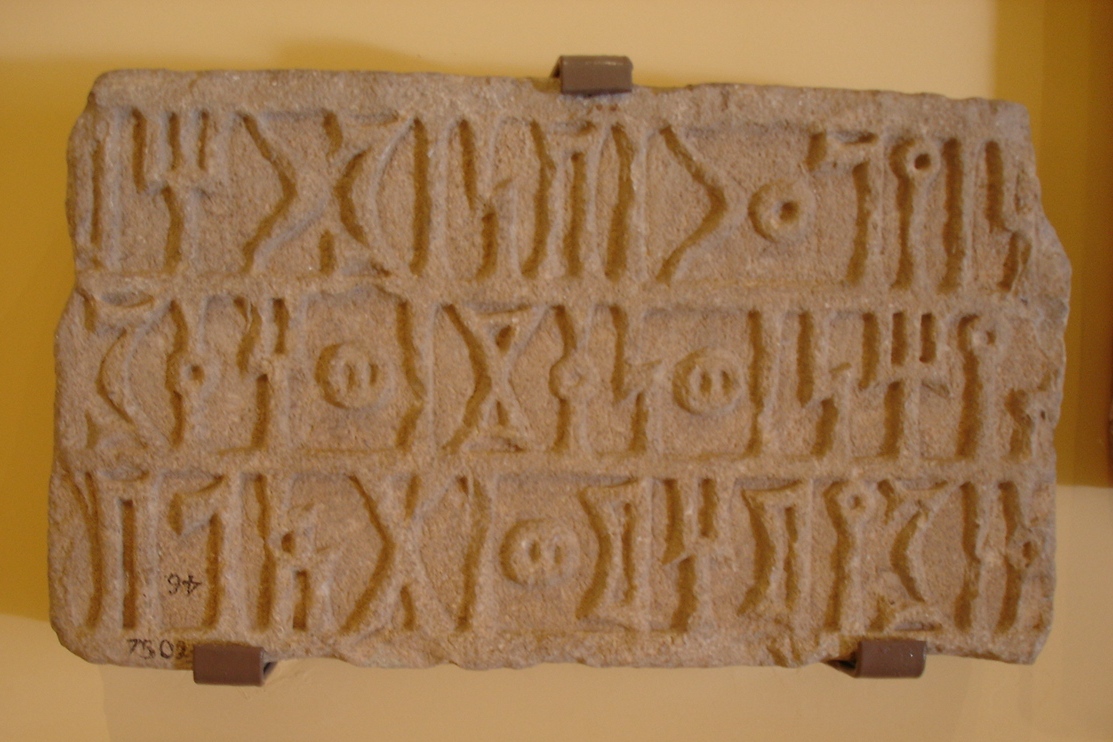

Archaeological excavations of ancient South Arabian settlements reveal a highly developed civic culture with complex irrigation techniques. For example, the Marib dam dates back to the 9th century BC and remains of it are still visible today. Substantial remains from the 6th century BC can still be seen. There were cities with public buildings made from polished limestone blocks with inscriptions naming their builders, along with city gates, fortifications, streets, temples, markets, and royal residences.

As the inscriptions show, numerous fortified cities (''hagar'') existed in pre-Islamic South Arabia. Archaeology has so far only revealed civic facilities; unfortified settlements have not yet been investigated archaeologically. The cities were often located in valleys on natural or artificial raised areas, which protected them from floods. Cities were also founded on plateaus or at the feet of mountains, as in the case of the Himyarite capital, Zafar. The majority of ancient South Arabian cities were rectangular or nearly rectangular, like Ma'rib and Shabwa. A notable example of this rectangular city plan is the Minaean capital city, Qarnawu. The rectangular plan of that city has a main street running through the centre and side streets bisecting it perpendicularly at regular intervals, which indicates central planning, either at the time of original foundation or after a destruction event. However, round and entirely irregular city plans are also found. Compared to other Near Eastern cities, the ancient South Arabian cities had a relatively small total area; the largest city of South Arabia, Ma'rib, covered only .

All cities were protected by a city wall (two consecutive walls in the case of Shabwa), with at least two gates, which could be protected by towers. The course of the walls, which was either simply structured or included bastions, had to follow the terrain, especially in mountainous regions, and this is what created irregular city plans. Sometimes cities were protected by citadels, as in Shabwa, Raidan, Qana', and the

Archaeological excavations of ancient South Arabian settlements reveal a highly developed civic culture with complex irrigation techniques. For example, the Marib dam dates back to the 9th century BC and remains of it are still visible today. Substantial remains from the 6th century BC can still be seen. There were cities with public buildings made from polished limestone blocks with inscriptions naming their builders, along with city gates, fortifications, streets, temples, markets, and royal residences.

As the inscriptions show, numerous fortified cities (''hagar'') existed in pre-Islamic South Arabia. Archaeology has so far only revealed civic facilities; unfortified settlements have not yet been investigated archaeologically. The cities were often located in valleys on natural or artificial raised areas, which protected them from floods. Cities were also founded on plateaus or at the feet of mountains, as in the case of the Himyarite capital, Zafar. The majority of ancient South Arabian cities were rectangular or nearly rectangular, like Ma'rib and Shabwa. A notable example of this rectangular city plan is the Minaean capital city, Qarnawu. The rectangular plan of that city has a main street running through the centre and side streets bisecting it perpendicularly at regular intervals, which indicates central planning, either at the time of original foundation or after a destruction event. However, round and entirely irregular city plans are also found. Compared to other Near Eastern cities, the ancient South Arabian cities had a relatively small total area; the largest city of South Arabia, Ma'rib, covered only .

All cities were protected by a city wall (two consecutive walls in the case of Shabwa), with at least two gates, which could be protected by towers. The course of the walls, which was either simply structured or included bastions, had to follow the terrain, especially in mountainous regions, and this is what created irregular city plans. Sometimes cities were protected by citadels, as in Shabwa, Raidan, Qana', and the  Due to a lack of archaeological investigation, the civic centres are so far only poorly known. In Timna in Qataban, there was a large open space inside the southern gate, from which streets ran in various directions. In addition to the normal residential buildings, fortresses, palaces and temples have been detected in various cities. Substantial excavations have only been undertaken at Khor Rori and Shabwa. At Shabwa, too, a large open space was located on the inside of the gate, with the royal palace located on one side of it. From this open space, a wide street ran directly through the city, with smaller streets crossing this main street at right angles.

In addition to civic fortifications, there are also other fortifications, which were located at important crossroads or key points in the irrigation system. Substantial ruins of such fortresses still exist, but none have been excavated. Even so, it is clear that these fortresses contained residential quarters as well as temples and water sources. To secure whole areas, barrier walls, which blocked passes and similar bottlenecks, were built, like the wall of

Due to a lack of archaeological investigation, the civic centres are so far only poorly known. In Timna in Qataban, there was a large open space inside the southern gate, from which streets ran in various directions. In addition to the normal residential buildings, fortresses, palaces and temples have been detected in various cities. Substantial excavations have only been undertaken at Khor Rori and Shabwa. At Shabwa, too, a large open space was located on the inside of the gate, with the royal palace located on one side of it. From this open space, a wide street ran directly through the city, with smaller streets crossing this main street at right angles.

In addition to civic fortifications, there are also other fortifications, which were located at important crossroads or key points in the irrigation system. Substantial ruins of such fortresses still exist, but none have been excavated. Even so, it is clear that these fortresses contained residential quarters as well as temples and water sources. To secure whole areas, barrier walls, which blocked passes and similar bottlenecks, were built, like the wall of

Compared to secular structures, temples are generally better known, so that it has been possible to develop a possible typology and history of development. In the following, the systems proposed by and (in more detail) M. Jung are described, which take into account both the floor plans and the actual appearance of the structure. Comparatively few temples have been excavated to date, so these schemas remain provisional.

The oldest south Arabian sanctuaries belong to the prehistoric period and were simple stone monoliths, sometimes surrounded by stone circles or mortarless masonry walls. In a second phase, actual temples were constructed. These temples were simple rectangular stone structures without roofs. Their interiors were initially very different from one another. Some cult buildings at Jabal Balaq al-Ausaṭ southwest of Ma'rib, which consist of a courtyard and a tripartite cella, provide a link to a temple type found only in Saba, which had a rectangular ground plan and a propylon and was divided into two parts - an inner courtyard with pillars on three sides and a tripartite cella. Schmidt includes in this type the temple of the moon god Wadd built around 700 BC between Ma'rib and Sirwah at Wadd ḏū-Masmaʿ, as well as the temple built by Yada'il Dharih I at Al-Masajid, which is surrounded by a rectangular wall. Later examples of this schema are found at Qarnawu (5th century BC) and (1st century BC). The entrance hall of the great Temple of Awwam in Ma'rib might belong to this group. This temple dates from the 9th-5th centuries BC and consisted of an oval ashlar structure which was over long and was linked to a rectangular entrance hall, which was surrounded by a peristyle consisting of 32 high monolithic pillars. Only a few traces of this structure remain today.

In the other kingdoms, this type contrasted with the

Compared to secular structures, temples are generally better known, so that it has been possible to develop a possible typology and history of development. In the following, the systems proposed by and (in more detail) M. Jung are described, which take into account both the floor plans and the actual appearance of the structure. Comparatively few temples have been excavated to date, so these schemas remain provisional.

The oldest south Arabian sanctuaries belong to the prehistoric period and were simple stone monoliths, sometimes surrounded by stone circles or mortarless masonry walls. In a second phase, actual temples were constructed. These temples were simple rectangular stone structures without roofs. Their interiors were initially very different from one another. Some cult buildings at Jabal Balaq al-Ausaṭ southwest of Ma'rib, which consist of a courtyard and a tripartite cella, provide a link to a temple type found only in Saba, which had a rectangular ground plan and a propylon and was divided into two parts - an inner courtyard with pillars on three sides and a tripartite cella. Schmidt includes in this type the temple of the moon god Wadd built around 700 BC between Ma'rib and Sirwah at Wadd ḏū-Masmaʿ, as well as the temple built by Yada'il Dharih I at Al-Masajid, which is surrounded by a rectangular wall. Later examples of this schema are found at Qarnawu (5th century BC) and (1st century BC). The entrance hall of the great Temple of Awwam in Ma'rib might belong to this group. This temple dates from the 9th-5th centuries BC and consisted of an oval ashlar structure which was over long and was linked to a rectangular entrance hall, which was surrounded by a peristyle consisting of 32 high monolithic pillars. Only a few traces of this structure remain today.

In the other kingdoms, this type contrasted with the

The most remarkable artworks aside from architecture from pre-Islamic South Arabia are sculptures. In addition to bronze (and occasionally gold and silver), limestone was a common material for sculptures, especially alabaster and marble. Typical features of ancient South Arabian sculpture are cubic base forms, a plump overall shape and very strong emphasis on the head. The rest of the body is often depicted only in a schematic and reduced fashion; often only the upper body is depicted at all. Much South Arabian art is characterised by minimal attention to realistic proportion, which manifests with large ears and a long, narrow nose. In most cases, sculpture in the round and reliefs faced directly at the viewer; in reliefs the frontal perspective typical of ancient Egyptian art, in which the head and legs are depicted from the side, but the torso from the front, is occasionally encountered. Pupils were made of coloured material which was inserted into holes in the eyes. Initially, drapery was not depicted, but later it was indicated by deep grooves or layers. There are no general characteristics in the arrangement of arms and legs.

There are very few examples of large ancient South Arabian sculptures, so the inscription on an over-life-size bronze statue of the son of the Sabaean king is of particular interest. It reveals that the statue was made by a Greek artist and his Arabian assistant. Much more common are small alabaster statues, portraits and reliefs, which generally depict people and more rarely animals or monsters (dragons and winged lions with human heads), and whole scenes in the case of flat reliefs. A particularly popular scene shows a vine bearing grapes with animals or birds nibbling at it and a man who aims a bow at an animal (or variations thereon). Scenes from life are also depicted in reliefs, such as feasts, battles, and musical performances, as well as scenes of the dead meeting with a deity.

The most remarkable artworks aside from architecture from pre-Islamic South Arabia are sculptures. In addition to bronze (and occasionally gold and silver), limestone was a common material for sculptures, especially alabaster and marble. Typical features of ancient South Arabian sculpture are cubic base forms, a plump overall shape and very strong emphasis on the head. The rest of the body is often depicted only in a schematic and reduced fashion; often only the upper body is depicted at all. Much South Arabian art is characterised by minimal attention to realistic proportion, which manifests with large ears and a long, narrow nose. In most cases, sculpture in the round and reliefs faced directly at the viewer; in reliefs the frontal perspective typical of ancient Egyptian art, in which the head and legs are depicted from the side, but the torso from the front, is occasionally encountered. Pupils were made of coloured material which was inserted into holes in the eyes. Initially, drapery was not depicted, but later it was indicated by deep grooves or layers. There are no general characteristics in the arrangement of arms and legs.

There are very few examples of large ancient South Arabian sculptures, so the inscription on an over-life-size bronze statue of the son of the Sabaean king is of particular interest. It reveals that the statue was made by a Greek artist and his Arabian assistant. Much more common are small alabaster statues, portraits and reliefs, which generally depict people and more rarely animals or monsters (dragons and winged lions with human heads), and whole scenes in the case of flat reliefs. A particularly popular scene shows a vine bearing grapes with animals or birds nibbling at it and a man who aims a bow at an animal (or variations thereon). Scenes from life are also depicted in reliefs, such as feasts, battles, and musical performances, as well as scenes of the dead meeting with a deity.

Alongside the larger artworks, ancient South Arabia also produced a whole range of different smaller artefacts. As elsewhere, ceramics were a major medium, but it has not yet been possible to arrange this material typologically or chronologically, so unlike in the rest of the Near East it does not help to date individual stratigraphic layers. Some general statements are still possible, however. The manufacture of ceramics was very simple; only part of the vessel was turned on a potter's wheel. Jugs and bowls of various sizes are common, mostly decorated with engraved or dotted motives, but painted patterns and attached bumps, prongs, or even animal heads are also found. In addition to these everyday ceramic items, some pottery figurines have also been found.

Smaller stone artefacts include bottles, oil lamps, vases, and vessels with animal heads as handles. Intaglios and imitations of Egyptian scarabs. In addition to these, there are also various friezes attached to various parts of buildings, which include zigzag patterns, tessellations, perpendicular lines, dentils, niches, small false doors, and meanders, as well as floral and figural elements, including series of ibex heads and grape vines. Other common artistic elements in buildings include rosettes and volutes, ears of corn, and pomegranates. In two excavations, wallpaintings have also been discovered: geometric paintings in the temple of al-Huqqa and figural paintings from the French excavations at Shabwat. Artefacts in wood have not survived, but stone images of furniture allow us some insight into ancient South Arabian woodworking.

Alongside the larger artworks, ancient South Arabia also produced a whole range of different smaller artefacts. As elsewhere, ceramics were a major medium, but it has not yet been possible to arrange this material typologically or chronologically, so unlike in the rest of the Near East it does not help to date individual stratigraphic layers. Some general statements are still possible, however. The manufacture of ceramics was very simple; only part of the vessel was turned on a potter's wheel. Jugs and bowls of various sizes are common, mostly decorated with engraved or dotted motives, but painted patterns and attached bumps, prongs, or even animal heads are also found. In addition to these everyday ceramic items, some pottery figurines have also been found.

Smaller stone artefacts include bottles, oil lamps, vases, and vessels with animal heads as handles. Intaglios and imitations of Egyptian scarabs. In addition to these, there are also various friezes attached to various parts of buildings, which include zigzag patterns, tessellations, perpendicular lines, dentils, niches, small false doors, and meanders, as well as floral and figural elements, including series of ibex heads and grape vines. Other common artistic elements in buildings include rosettes and volutes, ears of corn, and pomegranates. In two excavations, wallpaintings have also been discovered: geometric paintings in the temple of al-Huqqa and figural paintings from the French excavations at Shabwat. Artefacts in wood have not survived, but stone images of furniture allow us some insight into ancient South Arabian woodworking.

On the other hand, small bronze and copper artefacts are common, including vases and other chased copper or bronze vessels, lamps, handles and animal figurines. Jewellery is also common, including partially golden necklaces, gold plates with images of animals and small golden sculptures.

On the other hand, small bronze and copper artefacts are common, including vases and other chased copper or bronze vessels, lamps, handles and animal figurines. Jewellery is also common, including partially golden necklaces, gold plates with images of animals and small golden sculptures.

As in other cultures of the ancient 'periphery' which minted coinage, the ancient South Arabian coinage was modeled on ancient Greek coinage. Silver coinage is well known from South Arabia, while bronze and gold coinages are comparatively rare. The following typology generally follows that of Günther Dembski. The numbering of the coin types only partially reflects a certain chronology.

# The oldest South Arabian coinage was probably minted around 300 BC. It consists of imitations of Old style Athenian tetradrachms, with the head of Athena on the obverse and an owl, crescent moon, and olive twig on the reverse. Unlike their models, however, the South Arabian coins were marked with indications of their denomination: full units with the lett ''n'', half units with a ''g'', quarters with a ''t'', and eighths with an ''s''2.

# A somewhat later series has various monograms and/or letters on the reverse whose significance is not yet understood.

# The third, Qatabanian group has a head on both faces, with the name of the minting state, Harib in Timna, on the reverse.

# The next group is probably also Qatabanian. An owl again appears on the reverse, along with the name ''Shahr Hilal'', the letters ''ḏ'' and ''ḥ'', and the 'Yanuf-monogram'.

# Sometime in the 2nd century BC comes the following type, which imitates the New Style Athenian tetradrachms, while retaining the legends and monograms of the earlier coins.

# The sixth type is distinguished from the preceding type, since it has no inscription, only symbols or monograms.

# Perhaps in connection with the expedition of

As in other cultures of the ancient 'periphery' which minted coinage, the ancient South Arabian coinage was modeled on ancient Greek coinage. Silver coinage is well known from South Arabia, while bronze and gold coinages are comparatively rare. The following typology generally follows that of Günther Dembski. The numbering of the coin types only partially reflects a certain chronology.

# The oldest South Arabian coinage was probably minted around 300 BC. It consists of imitations of Old style Athenian tetradrachms, with the head of Athena on the obverse and an owl, crescent moon, and olive twig on the reverse. Unlike their models, however, the South Arabian coins were marked with indications of their denomination: full units with the lett ''n'', half units with a ''g'', quarters with a ''t'', and eighths with an ''s''2.

# A somewhat later series has various monograms and/or letters on the reverse whose significance is not yet understood.

# The third, Qatabanian group has a head on both faces, with the name of the minting state, Harib in Timna, on the reverse.

# The next group is probably also Qatabanian. An owl again appears on the reverse, along with the name ''Shahr Hilal'', the letters ''ḏ'' and ''ḥ'', and the 'Yanuf-monogram'.

# Sometime in the 2nd century BC comes the following type, which imitates the New Style Athenian tetradrachms, while retaining the legends and monograms of the earlier coins.

# The sixth type is distinguished from the preceding type, since it has no inscription, only symbols or monograms.

# Perhaps in connection with the expedition of

File:Alabaster head Louvre AO4746.jpg, Alabaster head ( Louvre)

File:British Museum Yemen 02.jpg, Alabaster head with inserted eyes ( British Museum)

File:Statue Ammaalay Louvre AO20282.jpg, Alabaster grave stele of ʿAmaʿalay dhu-Dharah'il (Hayd ibn Aqil, Qataban) (Louvre)

File:Stele Iglum Louvre AO1029.jpg, Sabaean alabaster grave stele of ʿIglum, son of Saʿad Illat Qaryot with two scenes of the deceased (Louvre)

File:Bm 139443.jpg, Inscribed bronze hand (British Museum)

File:Bmane2002-1-114,1.jpg, Stele, probably from Timna (British Museum)

File:BronzeManNashqum.jpg, Bronze sculpture from Nashaq (Louvre)

File:Bull statuette Louvre AO31570.jpg, Statuette of a bull (Louvre)

File:Statuette ibex Louvre AO31571.jpg, Statuette of an ibex (Louvre)

File:Bm 130880.jpg, Calcite sculpture (1st century BC) (British Museum)

File:Perfume-burner ibex Louvre DAO19.jpg, Perfume-burner with ibex (Louvre)

File:Dhamar Ali Yahbur II.jpg, A bronze statue of Dhamar Ali Yahbur II

Ancient South Arabian art was the art of the Pre-Islamic cultures of

Ancient South Arabian art was the art of the Pre-Islamic cultures of South Arabia

South Arabia () is a historical region that consists of the southern region of the Arabian Peninsula in Western Asia, mainly centered in what is now the Republic of Yemen, yet it has also historically included Najran, Jizan, Al-Bahah, and 'Asi ...

, which was produced from the 3rd millennium BC until the 7th century AD.Der Brockhaus Kunst. Künstler, Epochen, Sachbegriffe. 3rd revised and expanded edition. F. A. Brockhaus. Mannheim 2006

History and development

Old Arabian art experienced its first flourishing at the beginning of the 1st millennium BC at the time of the South Arabian classical culture, centred on the kingdoms of the Sabaeans and Minaeans in modern Yemen. The 5th century BC marked the golden age of Saba, whose main centres were

Old Arabian art experienced its first flourishing at the beginning of the 1st millennium BC at the time of the South Arabian classical culture, centred on the kingdoms of the Sabaeans and Minaeans in modern Yemen. The 5th century BC marked the golden age of Saba, whose main centres were Ma'rib

Marib ( ar, مَأْرِب, Maʾrib; Old South Arabian: 𐩣𐩧𐩨/𐩣𐩧𐩺𐩨 ''Mryb/Mrb'') is the capital city of Marib Governorate, Yemen. It was the capital of the ancient kingdom of ''Sabaʾ'' ( ar, سَبَأ), which some scholars ...

and Sirwah

Sirwah (OSA: Ṣrwḥ, ar, صرواح خولان ''Ṣirwāḥ Ḫawlān'') was, after Ma'rib, the most important economical and political center of the Kingdom of Saba at the beginning of the 1st century BC, on the Arabian Peninsula. Ṣirw� ...

. The region was known to the Romans as ' Arabia Felix' (Fortunate Arabia) as a result of its wealth.

The Geometric, stylised forms typical of ancient South Arabian art, both in sculpture and in architecture, took on smoother forms form the 5th century BC. The kingdom of the Nabataeans, established in the northern part of the Arabian peninsula in the late 4th century BC acted as an intermediary between the Arabian cultures and those of the Mediterranean.

The kings of Himyar gained control of South Arabia at the end of the 3rd century AD. With the Islamic expansion in the second half of the 6th century AD, South Arabian art was displaced by early Islamic art.

Periodisation

Since scholarship on ancient South Arabia has long concentrated on philological investigation of Old South Arabian inscriptions, the material culture of South Arabia has received little scholarly attention, so that little work has been done on the provenance of artefacts. Periodisations have only been developed for some regions and a general periodisation of South Arabian art is not yet possible. As a result, ancient South Arabian artefacts are categorised by stylistic features, not chronology. A general division of South Arabian art into three periods has been proposed byJürgen Schmidt

Jürgen Schmidt (born 11 July 1941) is a retired German speed skater. In 1964 he won three national titles, in 5000 m, 10000 m and all-around, and was selected for the 1964 Winter Olympics

The 1964 Winter Olympics, officially known as the IX ...

. According to him, the first phase sees the individual motifs begin to develop, the second sees the individual artistic forms become canonised, and in the last period there is some influence from foreign styles, particularly Greek art.

Architecture

Construction methods

Unlike Mesopotamia, ancient South Arabia was dominated by stone buildings. Only in the coastal areas and the Hadhramaut capital of

Unlike Mesopotamia, ancient South Arabia was dominated by stone buildings. Only in the coastal areas and the Hadhramaut capital of Shabwa

The ancient city of Shabwa ( Ḥaḑramitic: , romanized: , ; ar, شَبْوَة, translit=Šabwa) was the capital of the Kingdom of Hadhramaut at the South Arabian region of the Arabian Peninsula. The ruins of the city are located in the north ...

were there also large numbers of mudbrick structures. For monumental buildings, large hewn blocks of stone were used, which were fitted together without mortar and unhewn stone which required mortar. Lime mortar, mud, and asphalt were used as binding materials. In tall walls, vertical lead props and horizontal pins and brackets were inserted as well. Only the exterior face of the stones was smoothed. Larger walls were often double-shelled, with the rough sides of the stones abutting one another inside the wall. Possibly for aesthetic reasons, the walls of monumental structures were sloped, and buttresses or small bastions helped maintain the stability of the wall.

In the 5th century BC, a new kind of stoneworking appeared, in which the edges of the stones were polished, while the centre of the exposed faces were pecked. This 'marginally drafted' style changed over time, making a chronological arrangement of walls built in this style possible.

Interior walls were either plastered (sometimes featuring wall paintings) or covered with stone cladding, with paintings imitating ashlar blocks and sometimes even three-dimensional friezes. Little is known about ceiling construction, although vaulting survives in pillbox-graves - simple gabled roofs decorated with images. 3 cm thick translucent marble or alabaster sheets, sometimes with incised decoration, served as window panes.

Columns were a very important structural element. Until the 5th century BC, they were undecorated monoliths with rectangular or square cross-sections. This sort of column is found in the entrance hall of the Awwam temple and Ḥaram-Bilqīs in Ma'rib, for example. From the 5th century BC, the corners were reduced until eventually they became round columns. From the 5th century, columns also had capitals - initially simple plinths, which subsequently developed into various forms. From the 2nd century BC, these forms were significantly influenced by Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

architecture and later Sasanian influence is detectable.

Secular architecture

Citadel of Rada'a

The Citadel of Rada'a ( ar, قلعة رداع) is a historic castle in Yemen, located in the center of Rada'a District. The citadel sits at the highest point of the district, and consisted the original part of the city of Rada'a. The construction ...

.

Libna

Libna (, in older sources ''Libno'', german: Loibenberg) is a settlement in the hills immediately east of the town of Krško in eastern Slovenia. The area is part of the traditional region of Styria. It is now included with the rest of the munic ...

, which would have blocked the road from Qana' to Shabwa.

Due to the climate, irrigation systems were necessary for agriculture. The simplest elements of these systems were various kinds of well and cistern. The largest cisterns could hold up to 12,800 m³. For the efficiency of these wells and citadels, canal networks were essential. These collected and stored the water from the wadis when it rained. The most impressive example of these structures is the Dam of Ma'rib, which blocked the Wadi Dhana with a span of almost 600 m and channeled its water through two sluice gates into two "primary canals", which distributed it to the fields by means of a network of smaller canals. Such structures have been detected or attested by inscriptions elsewhere as well. In Najran

Najran ( ar, نجران '), is a city in southwestern Saudi Arabia near the border with Yemen. It is the capital of Najran Province. Designated as a new town, Najran is one of the fastest-growing cities in the kingdom; its population has risen fr ...

, aqueducts were carved into the cliffs to lead the water away.

In various places in South Arabia, especially in mountain passes (''manqal''), paved roads were built, which were sometimes many kilometres long and several metres wide.

Religious architecture

Compared to secular structures, temples are generally better known, so that it has been possible to develop a possible typology and history of development. In the following, the systems proposed by and (in more detail) M. Jung are described, which take into account both the floor plans and the actual appearance of the structure. Comparatively few temples have been excavated to date, so these schemas remain provisional.

The oldest south Arabian sanctuaries belong to the prehistoric period and were simple stone monoliths, sometimes surrounded by stone circles or mortarless masonry walls. In a second phase, actual temples were constructed. These temples were simple rectangular stone structures without roofs. Their interiors were initially very different from one another. Some cult buildings at Jabal Balaq al-Ausaṭ southwest of Ma'rib, which consist of a courtyard and a tripartite cella, provide a link to a temple type found only in Saba, which had a rectangular ground plan and a propylon and was divided into two parts - an inner courtyard with pillars on three sides and a tripartite cella. Schmidt includes in this type the temple of the moon god Wadd built around 700 BC between Ma'rib and Sirwah at Wadd ḏū-Masmaʿ, as well as the temple built by Yada'il Dharih I at Al-Masajid, which is surrounded by a rectangular wall. Later examples of this schema are found at Qarnawu (5th century BC) and (1st century BC). The entrance hall of the great Temple of Awwam in Ma'rib might belong to this group. This temple dates from the 9th-5th centuries BC and consisted of an oval ashlar structure which was over long and was linked to a rectangular entrance hall, which was surrounded by a peristyle consisting of 32 high monolithic pillars. Only a few traces of this structure remain today.

In the other kingdoms, this type contrasted with the

Compared to secular structures, temples are generally better known, so that it has been possible to develop a possible typology and history of development. In the following, the systems proposed by and (in more detail) M. Jung are described, which take into account both the floor plans and the actual appearance of the structure. Comparatively few temples have been excavated to date, so these schemas remain provisional.

The oldest south Arabian sanctuaries belong to the prehistoric period and were simple stone monoliths, sometimes surrounded by stone circles or mortarless masonry walls. In a second phase, actual temples were constructed. These temples were simple rectangular stone structures without roofs. Their interiors were initially very different from one another. Some cult buildings at Jabal Balaq al-Ausaṭ southwest of Ma'rib, which consist of a courtyard and a tripartite cella, provide a link to a temple type found only in Saba, which had a rectangular ground plan and a propylon and was divided into two parts - an inner courtyard with pillars on three sides and a tripartite cella. Schmidt includes in this type the temple of the moon god Wadd built around 700 BC between Ma'rib and Sirwah at Wadd ḏū-Masmaʿ, as well as the temple built by Yada'il Dharih I at Al-Masajid, which is surrounded by a rectangular wall. Later examples of this schema are found at Qarnawu (5th century BC) and (1st century BC). The entrance hall of the great Temple of Awwam in Ma'rib might belong to this group. This temple dates from the 9th-5th centuries BC and consisted of an oval ashlar structure which was over long and was linked to a rectangular entrance hall, which was surrounded by a peristyle consisting of 32 high monolithic pillars. Only a few traces of this structure remain today.

In the other kingdoms, this type contrasted with the hypostyle

In architecture, a hypostyle () hall has a roof which is supported by columns.

Etymology

The term ''hypostyle'' comes from the ancient Greek ὑπόστυλος ''hypóstȳlos'' meaning "under columns" (where ὑπό ''hypó'' means below or un ...

'multi-support temples' which were built with square, rectangular or even asymmetrical ground plans and were surrounded by regularly spaced columns. In contrast to the aforementioned Sabaean temples, these structures were not arranged around a cella or an altar. Initially these temple contained six or eight pillars, but later they ranged up to thirty-five. Klaus Schippmann has identified yet another type: the Hadhramite 'terrace temple', seven examples of which are known to date. All these temples are accessed by a great stairway, which leads up to an enclosed terrace, on top of which stands a cella with a podium.

It is still unclear whether there were images of deities, but the statuettes of humans which were dedicated in the sanctuary of Ma'rib demonstrate that highly developed bronze casts existed by the middle of the 1st century, on which the individual donor was recorded by means of an inscription. Stone pedestals with dedicatory inscriptions show that votive statuettes made of precious metals and bronze were created in Himyar until late antiquity. There were also alabaster statuettes - figures wearing smooth, knee-length robes, with their arms outstretched.

Sculpture

Minor arts

On the other hand, small bronze and copper artefacts are common, including vases and other chased copper or bronze vessels, lamps, handles and animal figurines. Jewellery is also common, including partially golden necklaces, gold plates with images of animals and small golden sculptures.

On the other hand, small bronze and copper artefacts are common, including vases and other chased copper or bronze vessels, lamps, handles and animal figurines. Jewellery is also common, including partially golden necklaces, gold plates with images of animals and small golden sculptures.

Numismatics

As in other cultures of the ancient 'periphery' which minted coinage, the ancient South Arabian coinage was modeled on ancient Greek coinage. Silver coinage is well known from South Arabia, while bronze and gold coinages are comparatively rare. The following typology generally follows that of Günther Dembski. The numbering of the coin types only partially reflects a certain chronology.

# The oldest South Arabian coinage was probably minted around 300 BC. It consists of imitations of Old style Athenian tetradrachms, with the head of Athena on the obverse and an owl, crescent moon, and olive twig on the reverse. Unlike their models, however, the South Arabian coins were marked with indications of their denomination: full units with the lett ''n'', half units with a ''g'', quarters with a ''t'', and eighths with an ''s''2.

# A somewhat later series has various monograms and/or letters on the reverse whose significance is not yet understood.

# The third, Qatabanian group has a head on both faces, with the name of the minting state, Harib in Timna, on the reverse.

# The next group is probably also Qatabanian. An owl again appears on the reverse, along with the name ''Shahr Hilal'', the letters ''ḏ'' and ''ḥ'', and the 'Yanuf-monogram'.

# Sometime in the 2nd century BC comes the following type, which imitates the New Style Athenian tetradrachms, while retaining the legends and monograms of the earlier coins.

# The sixth type is distinguished from the preceding type, since it has no inscription, only symbols or monograms.

# Perhaps in connection with the expedition of

As in other cultures of the ancient 'periphery' which minted coinage, the ancient South Arabian coinage was modeled on ancient Greek coinage. Silver coinage is well known from South Arabia, while bronze and gold coinages are comparatively rare. The following typology generally follows that of Günther Dembski. The numbering of the coin types only partially reflects a certain chronology.

# The oldest South Arabian coinage was probably minted around 300 BC. It consists of imitations of Old style Athenian tetradrachms, with the head of Athena on the obverse and an owl, crescent moon, and olive twig on the reverse. Unlike their models, however, the South Arabian coins were marked with indications of their denomination: full units with the lett ''n'', half units with a ''g'', quarters with a ''t'', and eighths with an ''s''2.

# A somewhat later series has various monograms and/or letters on the reverse whose significance is not yet understood.

# The third, Qatabanian group has a head on both faces, with the name of the minting state, Harib in Timna, on the reverse.

# The next group is probably also Qatabanian. An owl again appears on the reverse, along with the name ''Shahr Hilal'', the letters ''ḏ'' and ''ḥ'', and the 'Yanuf-monogram'.

# Sometime in the 2nd century BC comes the following type, which imitates the New Style Athenian tetradrachms, while retaining the legends and monograms of the earlier coins.

# The sixth type is distinguished from the preceding type, since it has no inscription, only symbols or monograms.

# Perhaps in connection with the expedition of Aelius Gallus

Gaius Aelius Gallus was a Roman prefect of Egypt from 26 to 24 BC. He is primarily known for a disastrous expedition he undertook to Arabia Felix (modern day Yemen) under orders of Augustus.

Life

Aelius Gallus was the 2nd ''praefect'' of Roman Eg ...

in 25 BC, elements of Roman coinage

Roman currency for most of Roman history consisted of gold, silver, bronze, orichalcum and copper coinage. From its introduction to the Republic, during the third century BC, well into Imperial times, Roman currency saw many changes in form, de ...

appear in this minting.

# A single Hadhramite group seems entirely different. They depict a bull labelled as the god Sin, the name of the palace ''s2qr'', a head with a radiant crown or an eagle, in various arrangements.On this type and its variants: S. C. H. Munro-Hay, "The coinage of Shabwa (Hadhramawt), and other ancient South Arabian Coinage in the National Museum, Aden," ''Syria'' 68 (1991) 393-418

# This type is particularly significant for the history of South Arabia. It bears a head on the reverse, with the name of a king and minting state (usually Raidan) and monograms.

# There are some isolated bronze coins which have a head with letters on the obverse and an eagle on the reverse. They are probably from Hadhramaut.

The end of South Arabian coinage is not certainly dated, but was probably somewhere around AD 300.

Gallery

References

Citations

Sources

* Adolf Grohmann: ''Handbuch der Altertumswissenschaft, Kulturgeschichte des Alten Orients, Dritter Abschnitt, Vierter Unterabschnitt: Arabien.'' München 1963.Further reading

* Christian Darles, "L’architecture civile à Shabwa." ''Syria. Revue d’art oriental et d’archéologie.'' 68 (1991) pp. 77 ff. * Günther Dembski, "Die Münzen der Arabia Felix." In Werner Daum (ed.), ''Jemen''. Pinguin-Verlag, Innsbruck / Umschau-Verlag, Frankfurt a. M. 1987, pp. 132–135, . * Almut Hauptmann von Gladiss, "Probleme altsüdarabischer Plastik." ''Baghdader Mitteilungen.'' 10 (1979), pp. 145–167 . * Klaus Schippmann: ''Geschichte der alt-südarabischen Reiche.'' Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1998, . *Jürgen Schmidt

Jürgen Schmidt (born 11 July 1941) is a retired German speed skater. In 1964 he won three national titles, in 5000 m, 10000 m and all-around, and was selected for the 1964 Winter Olympics

The 1964 Winter Olympics, officially known as the IX ...

, "Altsüdarabische Kultbauten." In Werner Daum (ed.), ''Jemen''. Pinguin-Verlag, Innsbruck / Umschau-Verlag, Frankfurt a. M. 1987, pp. 81–101, .

* Paul Alan Yule: ''Himyar - Spätantike im Jemen/Late Antique Yemen'', Linden Soft Verlag, Aichwald 2007, .

External links

{{Pre-Islamic Arabia Arabic art Ancient art Ancient history of Yemen Ancient Near East art and architecture South Arabia