American War of 1812 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It began when the United States declared war on 18 June 1812 and, although peace terms were agreed upon in the December 1814 Treaty of Ghent, did not officially end until the peace treaty was ratified by Congress on 17 February 1815.

Tensions originated in long-standing differences over territorial expansion in

Whether the annexation of Canada was a primary American war objective has been debated by historians. Some argue it was an outcome of the failure to change British policy through economic coercion or negotiation, leaving invasion as the only way for the US to place pressure on Britain. This view was summarised by Secretary of State James Monroe, who said " might be necessary to invade Canada, not as an object of the war but as a means to bring it to a satisfactory conclusion". Occupation would also disrupt supplies to colonies in the British West Indies and Royal Navy, and prevent the British arming their allies among the Indian nations of the

Whether the annexation of Canada was a primary American war objective has been debated by historians. Some argue it was an outcome of the failure to change British policy through economic coercion or negotiation, leaving invasion as the only way for the US to place pressure on Britain. This view was summarised by Secretary of State James Monroe, who said " might be necessary to invade Canada, not as an object of the war but as a means to bring it to a satisfactory conclusion". Occupation would also disrupt supplies to colonies in the British West Indies and Royal Navy, and prevent the British arming their allies among the Indian nations of the

The

The  The policies adopted by Harrison meant low-level conflict between local tribes and American settlers quickly escalated post-1803. In 1805, a Shawnee leader named Tenskwatawa launched a nativist religious movement that rejected American culture and values, while his elder brother

The policies adopted by Harrison meant low-level conflict between local tribes and American settlers quickly escalated post-1803. In 1805, a Shawnee leader named Tenskwatawa launched a nativist religious movement that rejected American culture and values, while his elder brother

The United States was in a period of significant political conflict between the

The United States was in a period of significant political conflict between the

The United States was only a secondary concern to Britain, so long as the war continued with France. In 1813, France had 80 ships-of-the-line and was building another 35. Containing the French fleet was the main British naval concern, leaving only the ships on the North American and Jamaica Stations immediately available. In Upper Canada, the British had the Provincial Marine. While largely unarmed, they were essential for keeping the army supplied since the roads were abysmal in Upper Canada. At the onset of war the Provincial Marine had four small armed vessels on Lake Ontario, three on Lake Erie and one on Lake Champlain. The Provincial Marine greatly outnumbered anything the Americans could bring to bear on the Great Lakes.

When the war broke out, the British Army in North America numbered 9,777 men in regular units and fencibles. While the British Army was engaged in the Peninsular War, few reinforcements were available. Although the British were outnumbered, the long-serving regulars and fencibles were better trained and more professional than the hastily expanded United States Army. The militias of Upper Canada and Lower Canada were initially far less effective, but substantial numbers of full-time militia were raised during the war and played pivotal roles in several engagements, including the Battle of the Chateauguay which caused the Americans to abandon the Saint Lawrence River theatre.

The United States was only a secondary concern to Britain, so long as the war continued with France. In 1813, France had 80 ships-of-the-line and was building another 35. Containing the French fleet was the main British naval concern, leaving only the ships on the North American and Jamaica Stations immediately available. In Upper Canada, the British had the Provincial Marine. While largely unarmed, they were essential for keeping the army supplied since the roads were abysmal in Upper Canada. At the onset of war the Provincial Marine had four small armed vessels on Lake Ontario, three on Lake Erie and one on Lake Champlain. The Provincial Marine greatly outnumbered anything the Americans could bring to bear on the Great Lakes.

When the war broke out, the British Army in North America numbered 9,777 men in regular units and fencibles. While the British Army was engaged in the Peninsular War, few reinforcements were available. Although the British were outnumbered, the long-serving regulars and fencibles were better trained and more professional than the hastily expanded United States Army. The militias of Upper Canada and Lower Canada were initially far less effective, but substantial numbers of full-time militia were raised during the war and played pivotal roles in several engagements, including the Battle of the Chateauguay which caused the Americans to abandon the Saint Lawrence River theatre.

The war had been preceded by years of diplomatic dispute, yet neither side was ready for war when it came. Britain was heavily engaged in the Napoleonic Wars, most of the British Army was deployed in the Peninsular War in Portugal and Spain, and the Royal Navy was blockading most of the coast of Europe. The number of British regular troops present in Canada in July 1812 was officially 6,034, supported by additional Canadian militia. Throughout the war, the British War Secretary was Earl Bathurst, who had few troops to spare for reinforcing North America defences during the first two years of the war. He urged Lieutenant General George Prévost to maintain a defensive strategy. Prévost, who had the trust of the Canadians, followed these instructions and concentrated on defending Lower Canada at the expense of Upper Canada, which was more vulnerable to American attacks and allowed few offensive actions. Unlike campaigns along the east coast, Prevost had to operate with no support from the Royal Navy.

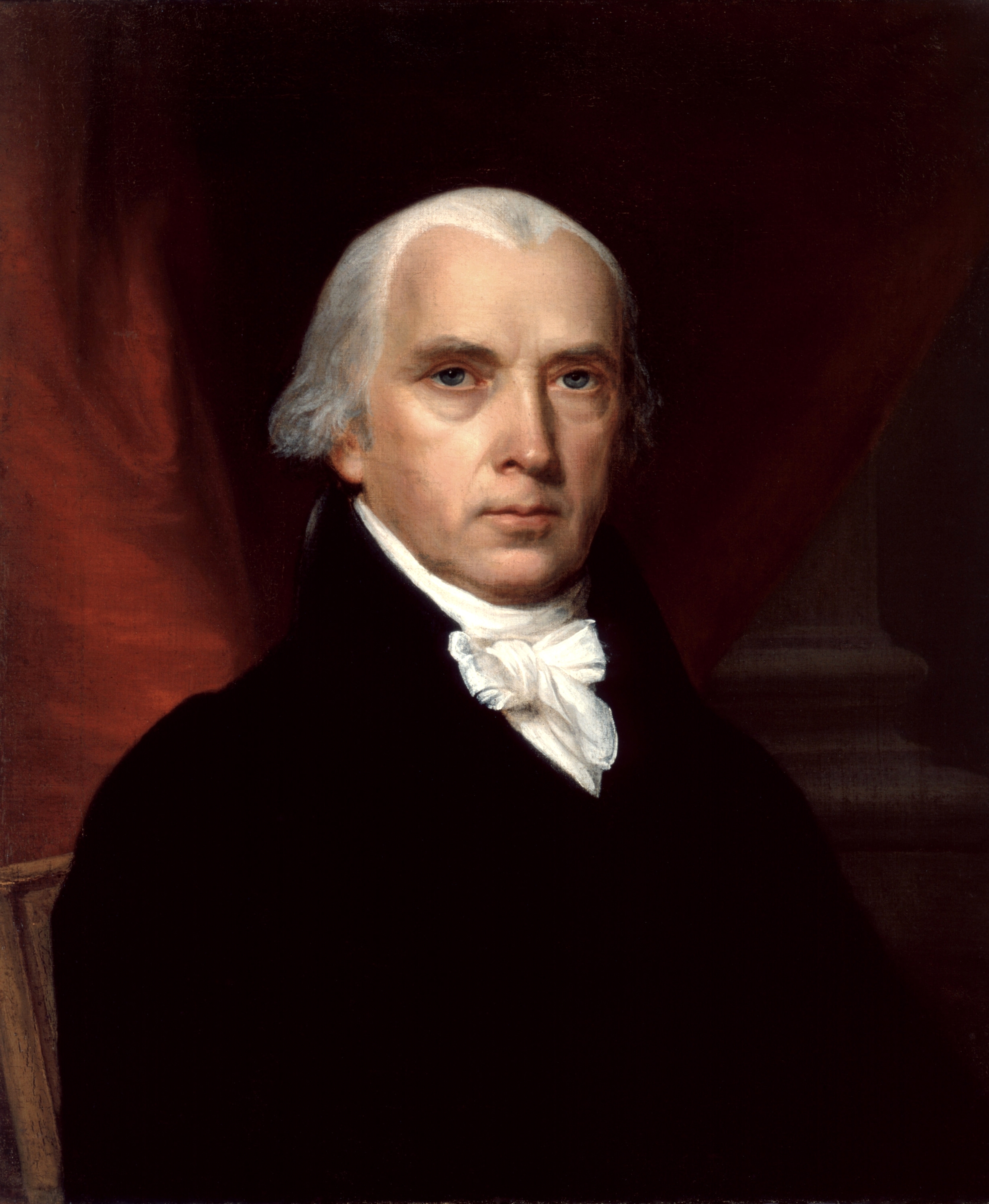

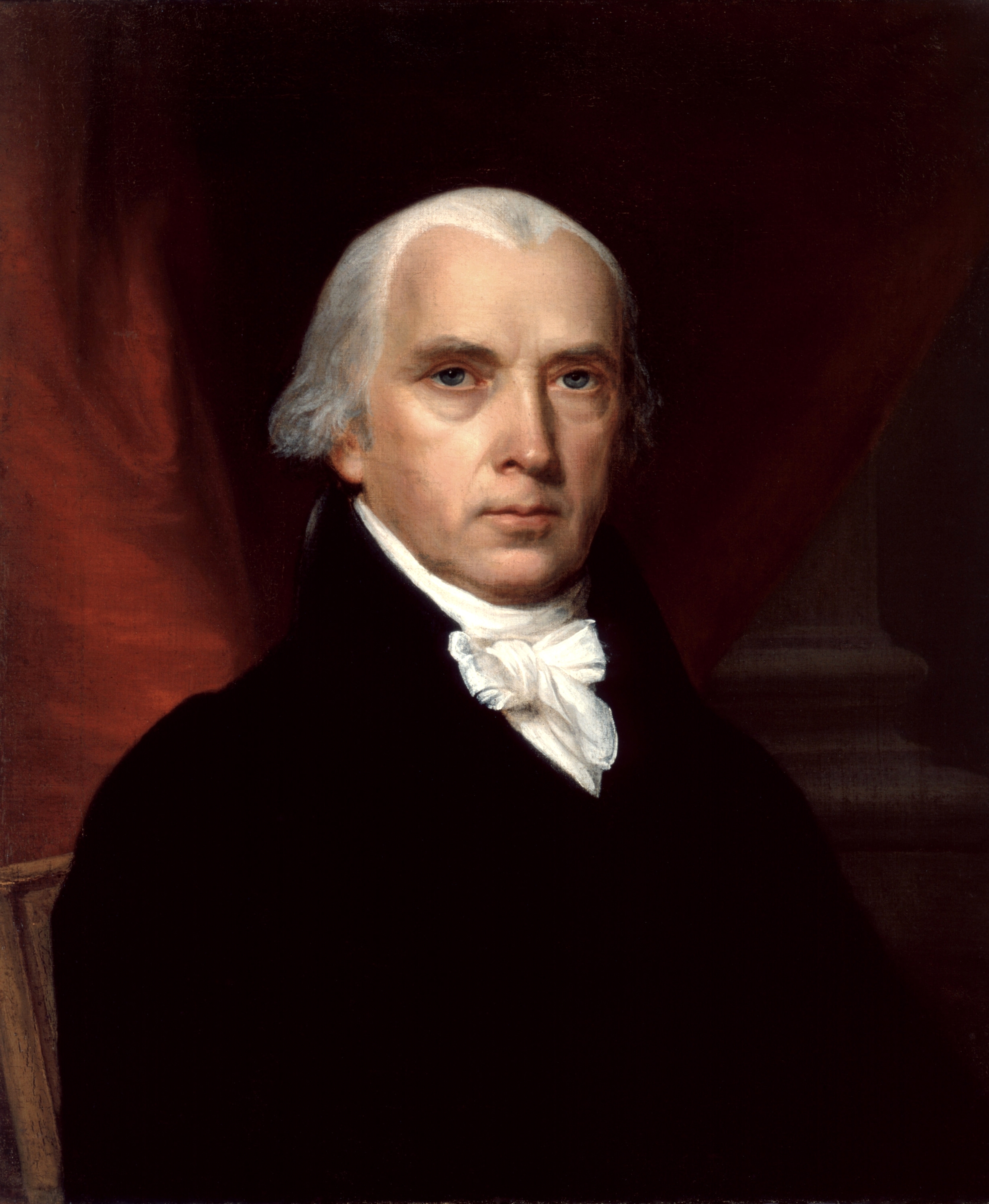

The United States was also not prepared for war. Madison had assumed that the state militias would easily seize Canada and that negotiations would follow. In 1812, the regular army consisted of fewer than 12,000 men. Congress authorized the expansion of the army to 35,000 men, but the service was voluntary and unpopular; it paid poorly and there were initially few trained and experienced officers. The militia objected to serving outside their home states, they were undisciplined and performed poorly against British forces when called upon to fight in unfamiliar territory. Multiple militia refused orders to cross the border and fight on Canadian soil.

American prosecution of the war suffered from its unpopularity, especially in New England where anti-war speakers were vocal. Massachusetts Congressmen

The war had been preceded by years of diplomatic dispute, yet neither side was ready for war when it came. Britain was heavily engaged in the Napoleonic Wars, most of the British Army was deployed in the Peninsular War in Portugal and Spain, and the Royal Navy was blockading most of the coast of Europe. The number of British regular troops present in Canada in July 1812 was officially 6,034, supported by additional Canadian militia. Throughout the war, the British War Secretary was Earl Bathurst, who had few troops to spare for reinforcing North America defences during the first two years of the war. He urged Lieutenant General George Prévost to maintain a defensive strategy. Prévost, who had the trust of the Canadians, followed these instructions and concentrated on defending Lower Canada at the expense of Upper Canada, which was more vulnerable to American attacks and allowed few offensive actions. Unlike campaigns along the east coast, Prevost had to operate with no support from the Royal Navy.

The United States was also not prepared for war. Madison had assumed that the state militias would easily seize Canada and that negotiations would follow. In 1812, the regular army consisted of fewer than 12,000 men. Congress authorized the expansion of the army to 35,000 men, but the service was voluntary and unpopular; it paid poorly and there were initially few trained and experienced officers. The militia objected to serving outside their home states, they were undisciplined and performed poorly against British forces when called upon to fight in unfamiliar territory. Multiple militia refused orders to cross the border and fight on Canadian soil.

American prosecution of the war suffered from its unpopularity, especially in New England where anti-war speakers were vocal. Massachusetts Congressmen

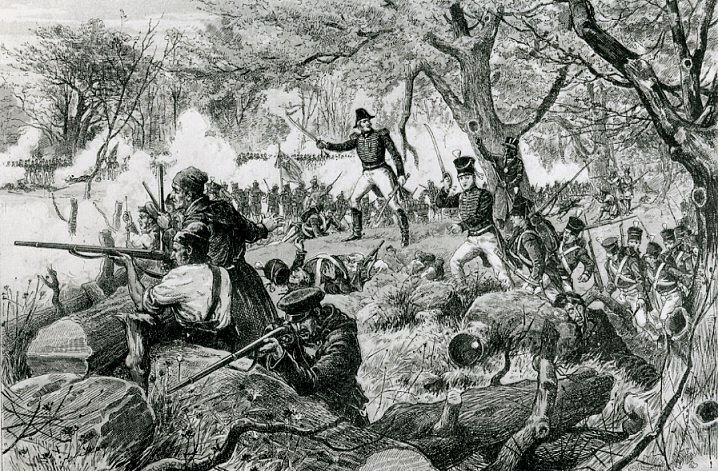

An American army commanded by William Hull invaded Upper Canada on July 12, arriving at Sandwich ( Windsor, Ontario) after crossing the Detroit River. His forces were chiefly composed of untrained and ill-disciplined militiamen. Hull issued a proclamation ordering all British subjects to surrender, or "the horrors, and calamities of war will stalk before you". The proclamation said that Hull wanted to free them from the "tyranny" of Great Britain, giving them the liberty, security, and wealth that his own country enjoyed—unless they preferred "war, slavery and destruction". He also threatened to kill any British soldier caught fighting alongside indigenous fighters. Hull's proclamation only helped to stiffen resistance to the American attacks as he lacked artillery and supplies. Hull also had to fight just to maintain his own lines of communication.

Hull withdrew to the American side of the river on 7 August 1812 after receiving news of a Shawnee ambush on Major

An American army commanded by William Hull invaded Upper Canada on July 12, arriving at Sandwich ( Windsor, Ontario) after crossing the Detroit River. His forces were chiefly composed of untrained and ill-disciplined militiamen. Hull issued a proclamation ordering all British subjects to surrender, or "the horrors, and calamities of war will stalk before you". The proclamation said that Hull wanted to free them from the "tyranny" of Great Britain, giving them the liberty, security, and wealth that his own country enjoyed—unless they preferred "war, slavery and destruction". He also threatened to kill any British soldier caught fighting alongside indigenous fighters. Hull's proclamation only helped to stiffen resistance to the American attacks as he lacked artillery and supplies. Hull also had to fight just to maintain his own lines of communication.

Hull withdrew to the American side of the river on 7 August 1812 after receiving news of a Shawnee ambush on Major  Major General Isaac Brock believed that he should take bold measures to calm the settler population in Canada and to convince the tribes that Britain was strong. He moved to Amherstburg near the western end of Lake Erie with reinforcements and attacked Detroit, using

Major General Isaac Brock believed that he should take bold measures to calm the settler population in Canada and to convince the tribes that Britain was strong. He moved to Amherstburg near the western end of Lake Erie with reinforcements and attacked Detroit, using

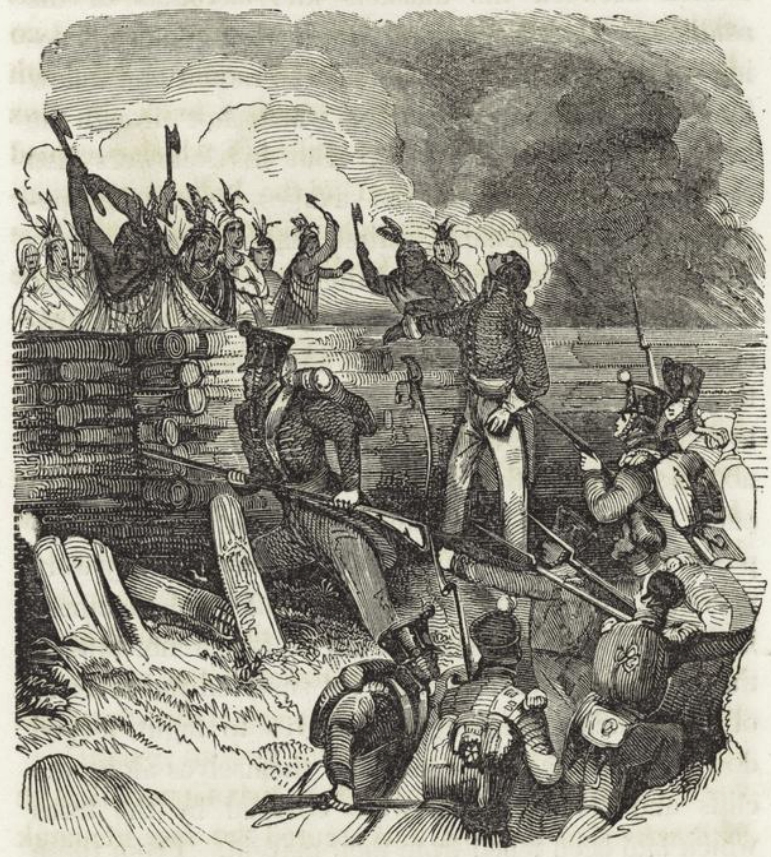

After Hull surrendered Detroit, General William Henry Harrison took command of the American Army of the Northwest. He set out to retake the city, which was now defended by Colonel

After Hull surrendered Detroit, General William Henry Harrison took command of the American Army of the Northwest. He set out to retake the city, which was now defended by Colonel

The American victory on Lake Erie and the recapture of Detroit isolated the British on Lake Huron. In the winter a Canadian party under Lieutenant Colonel Robert McDouall established a new supply line from York to Nottawasaga Bay on Georgian Bay. He arrived at Fort Mackinac on 18 May with supplies and more than 400 militia and Indians, then sent an expedition which successfully besieged and recaptured the key trading post of Prairie du Chien, on the Upper Mississippi. The Americans dispatched a substantial expedition to relieve the fort, but Sauk, Fox, and Kickapoo warriors under Black Hawk ambushed it and forced it to withdraw with heavy losses in the Battle of Rock Island Rapids. In September 1814, the Sauk, Fox, and Kickapoo, supported by part of Prairie du Chien's British garrison, repulsed a second American force led by Major Zachary Taylor in the

The American victory on Lake Erie and the recapture of Detroit isolated the British on Lake Huron. In the winter a Canadian party under Lieutenant Colonel Robert McDouall established a new supply line from York to Nottawasaga Bay on Georgian Bay. He arrived at Fort Mackinac on 18 May with supplies and more than 400 militia and Indians, then sent an expedition which successfully besieged and recaptured the key trading post of Prairie du Chien, on the Upper Mississippi. The Americans dispatched a substantial expedition to relieve the fort, but Sauk, Fox, and Kickapoo warriors under Black Hawk ambushed it and forced it to withdraw with heavy losses in the Battle of Rock Island Rapids. In September 1814, the Sauk, Fox, and Kickapoo, supported by part of Prairie du Chien's British garrison, repulsed a second American force led by Major Zachary Taylor in the

Both sides placed great importance on gaining control of the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River because of the difficulties of land-based communication. The British already had a small squadron of warships on Lake Ontario when the war began and had the initial advantage. The Americans established a Navy yard at Sackett's Harbor, New York, a port on Lake Ontario. Commodore Isaac Chauncey took charge of the thousands of sailors and

Both sides placed great importance on gaining control of the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River because of the difficulties of land-based communication. The British already had a small squadron of warships on Lake Ontario when the war began and had the initial advantage. The Americans established a Navy yard at Sackett's Harbor, New York, a port on Lake Ontario. Commodore Isaac Chauncey took charge of the thousands of sailors and  An American force surrendered on 24 June to a smaller British force due to advance warning by Laura Secord at the Battle of Beaver Dams, marking the end of the American offensive into Upper Canada. British Major General Francis de Rottenburg did not have the strength to retake Fort George, so he instituted a blockade, hoping to starve the Americans into surrender. Meanwhile, Commodore James Lucas Yeo had taken charge of the British ships on the lake and mounted a counterattack, which the Americans repulsed at the

An American force surrendered on 24 June to a smaller British force due to advance warning by Laura Secord at the Battle of Beaver Dams, marking the end of the American offensive into Upper Canada. British Major General Francis de Rottenburg did not have the strength to retake Fort George, so he instituted a blockade, hoping to starve the Americans into surrender. Meanwhile, Commodore James Lucas Yeo had taken charge of the British ships on the lake and mounted a counterattack, which the Americans repulsed at the

The Americans made two more thrusts against Montreal in 1813. Major General Wade Hampton was to march north from Lake Champlain and join a force under General

The Americans made two more thrusts against Montreal in 1813. Major General Wade Hampton was to march north from Lake Champlain and join a force under General

The Americans again invaded the Niagara frontier. They had occupied southwestern Upper Canada after they defeated Colonel Henry Procter at Moraviantown in October and believed that taking the rest of the province would force the British to cede it to them. The end of the war with Napoleon in Europe in April 1814 meant that the British could deploy their army to North America, so the Americans wanted to secure Upper Canada to negotiate from a position of strength. They planned to invade via the Niagara frontier while sending another force to recapture Mackinac. They captured Fort Erie on 3 July 1814. Unaware of Fort Erie's fall or of the size of the American force, the British general Phineas Riall engaged with Winfield Scott, who won against a British force at the

The Americans again invaded the Niagara frontier. They had occupied southwestern Upper Canada after they defeated Colonel Henry Procter at Moraviantown in October and believed that taking the rest of the province would force the British to cede it to them. The end of the war with Napoleon in Europe in April 1814 meant that the British could deploy their army to North America, so the Americans wanted to secure Upper Canada to negotiate from a position of strength. They planned to invade via the Niagara frontier while sending another force to recapture Mackinac. They captured Fort Erie on 3 July 1814. Unaware of Fort Erie's fall or of the size of the American force, the British general Phineas Riall engaged with Winfield Scott, who won against a British force at the  Meanwhile, 15,000 British troops were sent to North America under four of Wellington's ablest brigade commanders after Napoleon abdicated. Fewer than half were veterans of the Peninsula and the rest came from garrisons. Prévost was ordered to neutralize American power on the lakes by burning Sackett's Harbor to gain naval control of Lake Erie, Lake Ontario, and the Upper Lakes as well as to defend Lower Canada from attack. He did defend Lower Canada but otherwise failed to achieve his objectives, so he decided to invade New York State. His army outnumbered the American defenders of

Meanwhile, 15,000 British troops were sent to North America under four of Wellington's ablest brigade commanders after Napoleon abdicated. Fewer than half were veterans of the Peninsula and the rest came from garrisons. Prévost was ordered to neutralize American power on the lakes by burning Sackett's Harbor to gain naval control of Lake Erie, Lake Ontario, and the Upper Lakes as well as to defend Lower Canada from attack. He did defend Lower Canada but otherwise failed to achieve his objectives, so he decided to invade New York State. His army outnumbered the American defenders of  The Americans now had control of Lake Champlain; Theodore Roosevelt later termed it "the greatest naval battle of the war". General Alexander Macomb led the successful land defence. Prévost then turned back, to the astonishment of his senior officers, saying that it was too hazardous to remain on enemy territory after the loss of naval supremacy. He was recalled to London, where a naval court-martial decided that defeat had been caused principally by Prévost urging the squadron into premature action and then failing to afford the promised support from the land forces. He died suddenly, just before his court-martial was to convene. His reputation sank to a new low as Canadians claimed that their militia under Brock did the job but Prévost failed. However, recent historians have been kinder. Peter Burroughs argues that his preparations were energetic, well-conceived, and comprehensive for defending the Canadas with limited means and that he achieved the primary objective of preventing an American conquest.

The Americans now had control of Lake Champlain; Theodore Roosevelt later termed it "the greatest naval battle of the war". General Alexander Macomb led the successful land defence. Prévost then turned back, to the astonishment of his senior officers, saying that it was too hazardous to remain on enemy territory after the loss of naval supremacy. He was recalled to London, where a naval court-martial decided that defeat had been caused principally by Prévost urging the squadron into premature action and then failing to afford the promised support from the land forces. He died suddenly, just before his court-martial was to convene. His reputation sank to a new low as Canadians claimed that their militia under Brock did the job but Prévost failed. However, recent historians have been kinder. Peter Burroughs argues that his preparations were energetic, well-conceived, and comprehensive for defending the Canadas with limited means and that he achieved the primary objective of preventing an American conquest.

The strategic location of the Chesapeake Bay near the Potomac River made it a prime target for the British. Rear Admiral George Cockburn arrived there in March 1813 and was joined by Admiral Warren who took command of operations ten days later. Starting in March a squadron under Rear Admiral George Cockburn started a blockade of the mouth of the Bay at

The strategic location of the Chesapeake Bay near the Potomac River made it a prime target for the British. Rear Admiral George Cockburn arrived there in March 1813 and was joined by Admiral Warren who took command of operations ten days later. Starting in March a squadron under Rear Admiral George Cockburn started a blockade of the mouth of the Bay at

After taking some munitions from the Washington Munitions depot, the British, boarded their ships and moved on to their major target, the heavily fortified major city of Baltimore. Because some of their ships were held up in the

After taking some munitions from the Washington Munitions depot, the British, boarded their ships and moved on to their major target, the heavily fortified major city of Baltimore. Because some of their ships were held up in the

Before 1813, the war between the Creeks, or Muscogee, had been largely an internal affair sparked by the ideas of Tecumseh farther north in the Mississippi Valley. A faction known as the

Before 1813, the war between the Creeks, or Muscogee, had been largely an internal affair sparked by the ideas of Tecumseh farther north in the Mississippi Valley. A faction known as the  Jackson's force increased in numbers with the arrival of United States Army soldiers and a second draft of Tennessee state militia, Cherokee, and pro-American Creek swelled his army to around 5,000. In March 1814, they moved south to attack the Red Sticks. On 27 March, Jackson decisively defeated a force of about a thousand Red Sticks at Horseshoe Bend, killing 800 of them at a cost of 49 killed and 154 wounded.

Jackson then moved his army to Fort Jackson on the Alabama River. He promptly turned on the pro-American Creek who had fought with him and compelled their chieftains, along with a single Red Stick chieftain, to sign the Treaty of Fort Jackson, which forced the Creek tribe as a whole to cede most of western Georgia and part of Alabama to the U.S. Both Hawkins and the pro-American Creek strongly opposed the treaty, which they regarded as deeply unjust. The treaty also demanded that the Creek cease communicating with the British and Spanish and trade only with United States-approved agents.

British aid to the Red Sticks arrived after the end of the Napoleonic Wars in April 1814 and after Admiral Alexander Cochrane assumed command from Admiral Warren in March. Captain Hugh Pigot arrived with two ships to arm the Red Sticks. He thought that some 6,600 warriors could be armed and recruited. It was overly optimistic at best. The Red Sticks were in the process of being destroyed as a military force. In April 1814, the British established an outpost on the

Jackson's force increased in numbers with the arrival of United States Army soldiers and a second draft of Tennessee state militia, Cherokee, and pro-American Creek swelled his army to around 5,000. In March 1814, they moved south to attack the Red Sticks. On 27 March, Jackson decisively defeated a force of about a thousand Red Sticks at Horseshoe Bend, killing 800 of them at a cost of 49 killed and 154 wounded.

Jackson then moved his army to Fort Jackson on the Alabama River. He promptly turned on the pro-American Creek who had fought with him and compelled their chieftains, along with a single Red Stick chieftain, to sign the Treaty of Fort Jackson, which forced the Creek tribe as a whole to cede most of western Georgia and part of Alabama to the U.S. Both Hawkins and the pro-American Creek strongly opposed the treaty, which they regarded as deeply unjust. The treaty also demanded that the Creek cease communicating with the British and Spanish and trade only with United States-approved agents.

British aid to the Red Sticks arrived after the end of the Napoleonic Wars in April 1814 and after Admiral Alexander Cochrane assumed command from Admiral Warren in March. Captain Hugh Pigot arrived with two ships to arm the Red Sticks. He thought that some 6,600 warriors could be armed and recruited. It was overly optimistic at best. The Red Sticks were in the process of being destroyed as a military force. In April 1814, the British established an outpost on the

The British had the objective of gaining control of the entrance of the Mississippi, and to challenge the legality of the Louisiana Purchase. To this end, an expeditionary force of 8,000 troops under General Edward Pakenham attacked Jackson's prepared defences in New Orleans on 8 January 1815. The Battle of New Orleans was an American victory, as the British failed to take the fortifications on the East Bank. The British attack force suffered high casualties, including 291 dead, 1,262 wounded and 484 captured or missing whereas American casualties were light with 13 dead, 39 wounded and 19 missing, according to the respective official casualty returns. This battle was hailed as a great victory across the United States, making Jackson a national hero and eventually propelling him to the presidency. In January 1815 Fort St. Philip endured ten days of bombardment from two bomb vessels of the Royal Navy. Remini believes this was preventing the British moving their fleet up the Mississippi in support of the land attack. Roosevelt does not share Remini's theory. He observes that the British disengaged once the fort's mortar was resupplied and was able to return fire on 17 January 1815, the engagement being described as 'unsuccessfully bombarding' the fort by the British.

After deciding further attacks would be too costly and unlikely to succeed; the British fleet withdrew from the Mississippi River on 18 January. However, it was not until 27 January 1815 that the land forces rejoined the fleet, allowing for its final departure. After New Orleans, the British moved to take Mobile as a base for further operations. In preparation, General John Lambert laid siege to Fort Bowyer taking it on 12 February 1815. However HMS '' Brazen'' brought news of the Treaty of Ghent the next day and the British abandoned the Gulf Coast. This ending of the war prevented the capture of Mobile, and any renewed attacks on New Orleans.

Meanwhile, in January 1815, Admiral Cockburn succeeded in blockading the southeastern coast of Georgia by occupying Camden County. The British quickly took Cumberland Island, Fort Point Peter and Fort St. Tammany in a decisive victory. Under the orders of his commanding officers, Cockburn's forces relocated many refugee slaves, capturing St. Simons Island as well to do so. He had orders to recruit as many runaway slaves into the Corps of Colonial Marines as possible and use them to conduct raids in Georgia and the Carolinas. Cockburn also provided thousands of muskets and carbines and a huge quantity of ammunition to the Creeks and Seminole Indians for the same purpose. During the invasion of the Georgia coast, an estimated 1,485 people chose to relocate to British territories or join the British military.

However, by mid-March, several days after being informed of the Treaty of Ghent, British ships left the area.

The British did not recognize the West Florida territory as being legally American, as it had been seized from the Spanish during the war. The British also did not recognize the Louisiana Purchase because they and Spain voided all land deals and treaties made by Napoleon, especially the 1800–1804 transfer of Louisiana from Spain to France to the United States. Owsley is of the opinion this appeared to be compelling evidence that Britain had no intention of returning the region, had it completed capture of the territory, without new American concessions, referencing a letter from Thomas Shields to Daniel Patterson, dated January 25, 1815. This is contradicted by the content of Bathurst's correspondence, and disputed by Latimer, with specific reference to correspondence from the Prime Minister to the

The British had the objective of gaining control of the entrance of the Mississippi, and to challenge the legality of the Louisiana Purchase. To this end, an expeditionary force of 8,000 troops under General Edward Pakenham attacked Jackson's prepared defences in New Orleans on 8 January 1815. The Battle of New Orleans was an American victory, as the British failed to take the fortifications on the East Bank. The British attack force suffered high casualties, including 291 dead, 1,262 wounded and 484 captured or missing whereas American casualties were light with 13 dead, 39 wounded and 19 missing, according to the respective official casualty returns. This battle was hailed as a great victory across the United States, making Jackson a national hero and eventually propelling him to the presidency. In January 1815 Fort St. Philip endured ten days of bombardment from two bomb vessels of the Royal Navy. Remini believes this was preventing the British moving their fleet up the Mississippi in support of the land attack. Roosevelt does not share Remini's theory. He observes that the British disengaged once the fort's mortar was resupplied and was able to return fire on 17 January 1815, the engagement being described as 'unsuccessfully bombarding' the fort by the British.

After deciding further attacks would be too costly and unlikely to succeed; the British fleet withdrew from the Mississippi River on 18 January. However, it was not until 27 January 1815 that the land forces rejoined the fleet, allowing for its final departure. After New Orleans, the British moved to take Mobile as a base for further operations. In preparation, General John Lambert laid siege to Fort Bowyer taking it on 12 February 1815. However HMS '' Brazen'' brought news of the Treaty of Ghent the next day and the British abandoned the Gulf Coast. This ending of the war prevented the capture of Mobile, and any renewed attacks on New Orleans.

Meanwhile, in January 1815, Admiral Cockburn succeeded in blockading the southeastern coast of Georgia by occupying Camden County. The British quickly took Cumberland Island, Fort Point Peter and Fort St. Tammany in a decisive victory. Under the orders of his commanding officers, Cockburn's forces relocated many refugee slaves, capturing St. Simons Island as well to do so. He had orders to recruit as many runaway slaves into the Corps of Colonial Marines as possible and use them to conduct raids in Georgia and the Carolinas. Cockburn also provided thousands of muskets and carbines and a huge quantity of ammunition to the Creeks and Seminole Indians for the same purpose. During the invasion of the Georgia coast, an estimated 1,485 people chose to relocate to British territories or join the British military.

However, by mid-March, several days after being informed of the Treaty of Ghent, British ships left the area.

The British did not recognize the West Florida territory as being legally American, as it had been seized from the Spanish during the war. The British also did not recognize the Louisiana Purchase because they and Spain voided all land deals and treaties made by Napoleon, especially the 1800–1804 transfer of Louisiana from Spain to France to the United States. Owsley is of the opinion this appeared to be compelling evidence that Britain had no intention of returning the region, had it completed capture of the territory, without new American concessions, referencing a letter from Thomas Shields to Daniel Patterson, dated January 25, 1815. This is contradicted by the content of Bathurst's correspondence, and disputed by Latimer, with specific reference to correspondence from the Prime Minister to the

Because of their numerical inferiority, the American strategy was to cause disruption through hit-and-run tactics such as the capturing prizes and engaging Royal Navy vessels only under favourable circumstances. Days after the formal declaration of war, the United States put out two small squadrons, including the frigate ''President'' and the sloop under Commodore John Rodgers and the frigates ''United States'' and , with the brig under Captain

North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

and British support for Native American tribes who opposed US colonial settlement in the Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolutionary War. Established in 1 ...

. These escalated in 1807 after the Royal Navy began enforcing tighter restrictions on American trade with France and press-ganged

Impressment, colloquially "the press" or the "press gang", is the taking of men into a military or naval force by compulsion, with or without notice. European navies of several nations used forced recruitment by various means. The large size of ...

men they claimed as British subjects, even those with American citizenship certificates. Opinion in the US was split on how to respond, and although majorities in both the House

A house is a single-unit residential building. It may range in complexity from a rudimentary hut to a complex structure of wood, masonry, concrete or other material, outfitted with plumbing, electrical, and heating, ventilation, and air condi ...

and Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

voted for war, they divided along strict party lines, with the Democratic-Republican Party in favour and the Federalist Party

The Federalist Party was a Conservatism in the United States, conservative political party which was the first political party in the United States. As such, under Alexander Hamilton, it dominated the national government from 1789 to 1801.

De ...

against. News of British concessions made in an attempt to avoid war did not reach the US until late July, by which time the conflict was already underway.

At sea, the far larger Royal Navy imposed an effective blockade on U.S. maritime trade, while between 1812 to 1814 British regulars and colonial militia defeated a series of American attacks on Upper Canada. This was balanced by the US winning control of the Northwest Territory with victories at Lake Erie and the Thames in 1813. The abdication of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

in early 1814 allowed the British to send additional troops to North America and the Royal Navy to reinforce their blockade, crippling the American economy. In August 1814, negotiations began in Ghent, with both sides wanting peace; the British economy had been severely impacted by the trade embargo, while the Federalists convened the Hartford Convention in December to formalise their opposition to the war.

In August 1814, British troops burned Washington, before American victories at Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore was d ...

and Plattsburgh

Plattsburgh ( moh, Tsi ietsénhtha) is a city in, and the seat of, Clinton County, New York, United States, situated on the north-western shore of Lake Champlain. The population was 19,841 at the 2020 census. The population of the surrounding ...

in September ended fighting in the north. Fighting continued in the Southeastern United States, where in late 1813 a civil war had broken out between a Creek

A creek in North America and elsewhere, such as Australia, is a stream that is usually smaller than a river. In the British Isles it is a small tidal inlet.

Creek may also refer to:

People

* Creek people, also known as Muscogee, Native Americans

...

faction supported by Spanish and British traders and those backed by the US. Supported by US militia under General Andrew Jackson, the American backed Creeks won a series of victories, culminating in the capture of Pensacola in November 1814. In early 1815, Jackson defeated a British attack on New Orleans, catapulting him to national celebrity and later victory in the 1828 United States presidential election

The 1828 United States presidential election was the 11th quadrennial presidential election. It was held from Friday, October 31 to Tuesday, December 2, 1828. It featured a repetition of the 1824 election, as President John Quincy Adams of the ...

. News of this success arrived in Washington at the same time as that of the signing of the Treaty of Ghent, which essentially restored the position to that prevailing before the war. While Britain insisted this included lands belonging to their Native American allies prior to 1811, Congress did not recognize them as independent nations and neither side sought to enforce this requirement.

Origin

Since the conclusion of the War of 1812, historians have long debated the relative weight of the multiple reasons underlying its origins. During the nineteenth century, historians generally concluded that war was declared largely over national honour, neutral maritime rights and the British seizure of neutral ships and their cargoes on the high seas. This theme was the basis of President James Madison's war message to Congress on June 1, 1812. At the turn of the 20th century, much of the contemporary scholarship re-evaluated this explanation and began to focus more on non-maritime factors as significant contributing causes as well. However, historian Warren H. Goodman warns that too much focus on these ideas can be equally misleading. Historian Richard Maass argues that theexpansionist

Expansionism refers to states obtaining greater territory through military empire-building or colonialism.

In the classical age of conquest moral justification for territorial expansion at the direct expense of another established polity (who ...

theme is a myth that goes against the "relative consensus among experts that the primary American objective was the repeal of British maritime restrictions". He says that scholars agree that the United States went to war "because six years of economic sanctions had failed to bring Britain to the negotiating table, and threatening the Royal Navy's Canadian supply base was their last hope". Maass agrees that expansionism might have tempted Americans on a theoretical level, but he finds that "leaders feared the domestic political consequences of doing so", particularly because such expansion "focused on sparsely populated western lands rather than the more populous eastern settlements". To what extent that American leaders considered the question of pursuing territory in Canada, those questions "arose as a result of the war rather than as a driving cause." However, Maass accepts that many historians continue to believe that expansionism was a cause.

Reginald Horsman sees expansionism as a secondary cause after maritime issues, noting that many historians have mistakenly rejected expansionism as a cause for the war. He notes that it was considered key to maintaining sectional balance between free and slave states thrown off by American settlement of the Louisiana Territory and widely supported by dozens of War Hawk congressmen such as Henry Clay

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American attorney and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. He was the seventh House speaker as well as the ninth secretary of state, al ...

, Felix Grundy, John Adams Harper

John Adams Harper (November 2, 1779 – June 18, 1816) was an American politician and a United States Representative from New Hampshire.

Early life

Born in Derryfield, New Hampshire, Harper attended Phillips Exeter Academy in 1794. He studied ...

and Richard Mentor Johnson, who voted for war with expansion as a key aim. However, Horsman states that in his view "the desire for Canada did not cause the War of 1812" and that "The United States did not declare war because it wanted to obtain Canada, but the acquisition of Canada was viewed as a major collateral benefit of the conflict".

However, other historians believe that a desire to permanently annex Canada was a direct cause of the war. Carl Benn notes that the War Hawks' desire to annex the Canadas was similar to the enthusiasm for the annexation of Spanish Florida

Spanish Florida ( es, La Florida) was the first major European land claim and attempted settlement in North America during the European Age of Discovery. ''La Florida'' formed part of the Captaincy General of Cuba, the Viceroyalty of New Spain, ...

by inhabitants of the American South as both expected war to facilitate expansion into long-desired lands and end support for hostile tribes ( Tecumseh's Confederacy in the North and the Creek

A creek in North America and elsewhere, such as Australia, is a stream that is usually smaller than a river. In the British Isles it is a small tidal inlet.

Creek may also refer to:

People

* Creek people, also known as Muscogee, Native Americans

...

in the South).

Alan Taylor says that many Democratic-Republican congressmen such as John Adams Harper, Richard Mentor Johnson and Peter Buell Porter "longed to oust the British from the continent and to annex Canada". A few Southerners opposed this, fearing an imbalance of free and slave states if Canada was annexed. Anti-Catholicism

Anti-Catholicism is hostility towards Catholics or opposition to the Catholic Church, its clergy, and/or its adherents. At various points after the Reformation, some majority Protestant states, including England, Prussia, Scotland, and the Uni ...

also caused many to oppose annexing the mainly Catholic Lower Canada, believing its French-speaking inhabitants unfit "for republican citizenship". Even major figures such as Henry Clay and James Monroe expected to keep at least Upper Canada in an easy conquest. Notable American generals such as William Hull issued proclamations to Canadians during the war promising republican liberation through incorporation into the United States. General Alexander Smyth

Alexander Smyth (1765April 17, 1830) was an American lawyer, soldier, and politician from Virginia. Smyth served in the Virginia Senate, Virginia House of Delegates, United States House of Representatives and as a general during the War of 1812 ...

similarly declared to his troops when they invaded Canada that "you will enter a country that is to become one of the United States. You will arrive among a people who are to become your fellow-citizens". However, a lack of clarity about American intentions undercut these appeals.

David and Jeanne Heidler argue that "most historians agree that the War of 1812 was not caused by expansionism but instead reflected a real concern of American patriots to defend United States' neutral rights from the overbearing tyranny of the British Navy. That is not to say that expansionist aims would not potentially result from the war". However, they also argue otherwise, saying that "acquiring Canada would satisfy America's expansionist desires", also describing it as a key goal of western expansionists who, they argue, believed that "eliminating the British presence in Canada would best accomplish" their goal of halting British support for tribal raids. They argue that the "enduring debate" is over the relative importance of expansionism as a factor, and whether "expansionism played a greater role in causing the War of 1812 than American concern about protecting neutral maritime rights".

In the 1960s, the work of Norman K. Risjord

Norman K. Risjord (November 25, 1931 – January 1, 2019) was an American professor, historian and author of early American history and the early history of the northern Midwest states. Risjord was a teacher at the University of Wisconsin for mor ...

, Reginald Horsman, Bradford Perkins and Roger Brown established a new eastern maritime consensus. While these authors approached the origins of the war from many perspectives, they all conceded that British maritime policy was the principal cause of the war.

Honour and the "second war of independence"

As historianNorman K. Risjord

Norman K. Risjord (November 25, 1931 – January 1, 2019) was an American professor, historian and author of early American history and the early history of the northern Midwest states. Risjord was a teacher at the University of Wisconsin for mor ...

notes, a powerful motivation for the Americans was their threatened sense of independence and the desire to uphold national honour in the face of what they considered British aggression and insults such as the ''Chesapeake''–''Leopard'' affair. H. W. Brands

Henry William Brands Jr. (born August 7, 1953) is an American historian. He holds the Jack S. Blanton Sr. Chair in History at the University of Texas at Austin, where he earned his PhD in history in 1985. He has authored 30 books on U.S. histor ...

writes: "The other war hawks spoke of the struggle with Britain as a second war of independence; ndrewJackson, who still bore scars from the first war of independence, held that view with special conviction. The approaching conflict was about violations of American rights, but it was also about vindication of American identity". Some Americans at the time and some historians since have called it a "Second War of Independence" for the United States.

The young republic had been involved in several struggles to uphold what it regarded as its rights, and honour, as an independent nation. The First Barbary War had resulted in an apparent victory but with the continued payment of ransoms. The Quasi-War against the French had involved single ship naval clashes over trade rights similar to the ones about to occur with Britain. Upholding national honour and being able to protect American rights was part of the background to the US political and diplomatic attitudes towards Britain in the early 1800s.

At the same time, the British public were offended by what they considered insults, such as the ''Little Belt'' affair. This gave them a particular interest in capturing the American flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

'' President'', an act that they successfully realized in 1815. They were also keen to maintain what they saw as their rights to stop and search neutral vessels as part of their war with France, and further ensure that their own commercial interests were protected.

Impressment, trade, and naval actions

Britain was the largest trading partner of the United States, receiving 80 percent of American cotton and 50 percent of all other American exports. The British public and press resented the growingmercantile

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

An early form of trade, barter, saw the direct exchan ...

and commercial competition.

Historian Reginald Horsman states that "a large section of influential British opinion ..thought that the United States presented a threat to British maritime supremacy".

During the Seven Years' War, Britain introduced rules governing trade with their enemies. The Rule of 1756, which the US had temporarily agreed to when signing the Jay Treaty, stated that a neutral nation could not conduct trade with an enemy, if that trade was closed to them before hostilities had commenced. Since the beginning of Britain's war with France in 1793, the US merchant marine had been making a fortune continuing trading with both nations, America's share of trans-Atlantic trade growing from 250 thousand tons in 1790 to 981 thousand tons in 1810, in the process. Of particular concern to the British was the transport of goods from the French West Indies to France, something the US would have been unable to do, due to French rules, during times of peace. The United States' view was that the treaty they had signed violated its right to trade with others, and in order to circumvent the Rule of 1756, American ships would stop at a neutral port to unload and reload their cargo before continuing to France. These actions were challenged in the ''Essex'' case of 1805.

In 1806, with parts of the Jay Treaty due to expire, a new agreement was sought. The Monroe–Pinkney Treaty offered the US preferential trading rights, and would have settled most its issues with Britain but did not moderate the Rule of 1756 and only offered to exercise "extreme caution" and "immediate and prompt redress" with regard to impressment of Americans. Jefferson, who had specifically asked for these two points to be extirpated, refused to put the treaty before the senate.

Later, in 1806, Napoleon's Berlin Decree declared a blockade of the British Isles, forbade neutral vessels harbour in British ports and declared all British made goods carried on neutral ships lawful prizes of war. The British responded in 1807 with Orders in Council which similarly forbade any shipping to France. By 1807, when Napoleon introduced his Milan Decree

The Milan Decree was issued on 17 December 1807 by Napoleon I of France to enforce the 1806 Berlin Decree, which had initiated the Continental System, the basis for his plan to defeat the British by waging economic warfare.

The Milan Decree s ...

, declaring all ships touching at British ports to be legitimate prizes of war, it had become almost impossible for the US to remain neutral. Between 1804 and 1807, 731 American ships were seized by Britain or France for violation of one of the blockades, roughly two thirds by Britain. Since the Jay Treaty, France had also adopted an aggressive attitude to American neutrality.

Whereas Britain, through a process known as pre-emption, compensated American ship owners for their losses, France did not. French frigates burned American grain ships heading for Britain and treated American sailors as prisoners of war. US–French relations had soured so much, that by 1812, Madison was also considering war with France.

As a result of these increasing trade volumes during the Napoleonic Wars the United States Merchant Marine became the world's largest neutral shipping fleet. Between 1802 and 1810, it nearly doubled, which meant that there were insufficient experienced sailors in the United States to man it. To overcome this shortfall, British seamen were recruited, who were attracted by the better pay and conditions. It was estimated that 30% (23,000) of the 70,000 men employed on American ships were British. During the Napoleonic Wars, the British Royal Navy expanded to 600 ships, requiring 140,000 sailors. The Royal Navy could man its ships with volunteers in peacetime, but in wartime, competing with merchant shipping and privateers for the pool of experienced sailors, it turned to impressment from ashore and at sea. Since 1795 the Quota System had been in use to feed men to the navy but it was not alone sufficient. Though most saw it as necessary, the practice of impressment was detested by most Britons. It was illegal under British law to impress foreign sailors; but it was the accepted practice of the era for nations to retrieve seamen of their own nationality from foreign navies during times of war. However, in the nineteen years Britain was at war with France prior to the war of 1812 some ten thousand American citizens were impressed into the British navy.

The American ambassador in London, James Monroe, under President Thomas Jefferson, protested to the British Foreign Office that more than fifteen thousand Americans had been impressed into the Royal Navy since March 1803. When asked for a list however, the Madison administration was only able to produce one based on hearsay, with 6,257 names, many of which were duplicated, and included those that had legitimately volunteered to serve. By 1804 the incidents of impressment of Americans had sharply increased. Underlying the dispute was the issue that Britain and the United States viewed nationality differently. The United States believed that British seamen, including naval deserters, had a right to become American citizens. In reality few actually went through the formal process. Regardless Britain did not recognize a right for a British subject to relinquish his citizenship and become a citizen of another country. The Royal Navy therefore considered any American citizen subject to impressment if he was born British. American reluctance to issue formal naturalization

Naturalization (or naturalisation) is the legal act or process by which a non-citizen of a country may acquire citizenship or nationality of that country. It may be done automatically by a statute, i.e., without any effort on the part of the in ...

papers and the widespread use of unofficial or forged identity or protection papers among sailors made it difficult for the Royal Navy to tell native born-Americans from naturalized-Americans and even non-Americans, and led it to impress some American sailors who had never been British. Though Britain was willing to release from service anyone who could establish their American citizenship, the process often took years while the men in question remained impressed in the British Navy. However, from 1793 to 1812 up to 15,000 Americans had been impressed while many appeals for release were simply ignored or dismissed for other reasons. There were also cases when the United States Navy also impressed British sailors. Once impressed, any seaman, regardless of citizenship, could accept a recruitment bounty and was then no longer considered impressed but a "volunteer", further complicating matters.

American anger with Britain grew when Royal Navy frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and ...

s were stationed just outside American harbours in view of American shores to search ships for goods bound to France and impress men within the United States territorial waters. Well-publicized events outraged the American public such as the ''Leander'' affair and the ''Chesapeake''–''Leopard'' affair.

The British public were outraged in their turn by the ''Little Belt'' affair in which the larger USS ''President'' in search of HMS ''Guerriere'' instead clashed with a small British sloop

A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast typically having only one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft of (behind) the mast. Such an arrangement is called a fore-and-aft rig, and can be rigged as a Bermuda rig with triangular sa ...

, resulting in the deaths of 11 British sailors. While both sides claimed that the other fired first, the British public particularly blamed the United States for attacking a smaller vessel, with calls in some newspapers for revenge. ''President'' had sighted and chased HMS ''Little Belt'' trying to determine her identity throughout the afternoon. The first shot took place after an exchange of hails had still failed to identify either ship to the other in the growing dusk. After 45 minutes of battle, taking place in darkness, ''Little Belt'' had received much damage, with several holes to her hull near the water-line and her rigging "cut to pieces". ''President''s Captain Rodgers claimed ''Little Belt'' had fired first; but he did not ascertain her size or country of origin until dawn. After sending over a boat, Rodgers expressed regret and apologized for the 'unfortunate affair'. ''Little Belt''s Captain Bingham claimed the opposite: ''President'' had fired first and had been manoeuvering in such a way as to make him think she was planning an attack. Historian Jonathon Hooks echoes the view of Alfred T. Mahan

Alfred Thayer Mahan (; September 27, 1840 – December 1, 1914) was a United States naval officer and historian, whom John Keegan called "the most important American strategist of the nineteenth century." His book '' The Influence of Sea Power ...

and several other historians, that it is impossible to determine who fired the first shot. Both sides held inquiries which upheld their captain's actions and version of events. Meanwhile, the American public regarded the incident as just retribution for the Chesapeake–Leopard affair and were encouraged by their victory over the Royal Navy, while the British regarded it as unprovoked aggression.

Canada and the US

Whether the annexation of Canada was a primary American war objective has been debated by historians. Some argue it was an outcome of the failure to change British policy through economic coercion or negotiation, leaving invasion as the only way for the US to place pressure on Britain. This view was summarised by Secretary of State James Monroe, who said " might be necessary to invade Canada, not as an object of the war but as a means to bring it to a satisfactory conclusion". Occupation would also disrupt supplies to colonies in the British West Indies and Royal Navy, and prevent the British arming their allies among the Indian nations of the

Whether the annexation of Canada was a primary American war objective has been debated by historians. Some argue it was an outcome of the failure to change British policy through economic coercion or negotiation, leaving invasion as the only way for the US to place pressure on Britain. This view was summarised by Secretary of State James Monroe, who said " might be necessary to invade Canada, not as an object of the war but as a means to bring it to a satisfactory conclusion". Occupation would also disrupt supplies to colonies in the British West Indies and Royal Navy, and prevent the British arming their allies among the Indian nations of the Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolutionary War. Established in 1 ...

.

Nevertheless, even though President Madison claimed permanent annexation was not an objective, he recognised once acquired it would be "difficult to relinquish". A large faction in Congress actively advocated this policy, including Richard Mentor Johnson, who stated "I shall never die content until I see England's expulsion from North America and her territories incorporated into the United States". John Adams Harper

John Adams Harper (November 2, 1779 – June 18, 1816) was an American politician and a United States Representative from New Hampshire.

Early life

Born in Derryfield, New Hampshire, Harper attended Phillips Exeter Academy in 1794. He studied ...

claimed "the Author of Nature Himself had marked our limits in the south, by the Gulf of Mexico, and on the north, by the regions of eternal frost". Both saw the war as part of a divine plan to unify the US and Canada, Johnson being its leading exponent.

Others considered annexation a matter of domestic economic and political necessity. Tennessee Congressman Felix Grundy was one of many who saw it as essential to preserve the balance between slave states and free states that might be disrupted by the incorporation of territories in the Southeast acquired in the 1803 Louisiana Purchase. Control of the St. Lawrence River, the major outlet for trade between Europe and the Great Lakes region, was a long-standing American ambition, going back to the early years of the Revolutionary War, and supported by powerful economic interests in the North-West. Madison also viewed it as a way to prevent American smugglers using the river as a conduit for undercutting his trade policies.

All these groups assumed American troops would be greeted as liberators, guaranteeing an easy conquest. Thomas Jefferson believed taking "...Canada this year, as far as... Quebec, will be a mere matter of marching, and will give us the experience for the attack on Halifax, the next and final expulsion of England from the American continent". In 1812, Canada had around 525,000 inhabitants, two thirds of whom were French-speakers living in Quebec. Upper Canada, now southern Ontario, had a population of less than 75,000, primarily Loyalist

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cro ...

exiles and recent immigrants from the Northeastern United States

The Northeastern United States, also referred to as the Northeast, the East Coast, or the American Northeast, is a geographic region of the United States. It is located on the Atlantic coast of North America, with Canada to its north, the Southe ...

. The former were implacably hostile to the United States; the latter largely uninterested in politics and their loyalties unknown; unlike the Texas annexation in 1845, they were too few to provide a critical mass of pro-American support, while many followed their Loyalist neighbours and joined Canadian militia. Absence of local backing prevented American forces from establishing a foothold in the area, and of ten attempts to invade Upper Canada between 1812 and 1814, the vast majority ended in failure.

US policy in the Northwest Territory

The

The Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolutionary War. Established in 1 ...

, a region between the Great Lakes, the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

, Appalachians, and Mississippi, was a long-standing source of conflict in 18th and early 19th-century North America. This arose when settlers from the Thirteen Colonies moved onto lands owned by the indigenous inhabitants, a collection of Algonquian and Iroquoian-speaking peoples, chiefly the Shawnee, Wyandot, Lenape

The Lenape (, , or Lenape , del, Lënapeyok) also called the Leni Lenape, Lenni Lenape and Delaware people, are an indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands, who live in the United States and Canada. Their historical territory includ ...

, Miami, Potawatomi

The Potawatomi , also spelled Pottawatomi and Pottawatomie (among many variations), are a Native American people of the western Great Lakes region, upper Mississippi River and Great Plains. They traditionally speak the Potawatomi language, a m ...

, Kickapoo

Kickapoo may refer to:

People

* Kickapoo people, a Native American nation

** Kickapoo language, spoken by that people

** Kickapoo Tribe of Kansas, a federally recognized tribe of Kickapoo people

** Kickapoo Tribe of Oklahoma, a federally recog ...

, Menominee and Odawa

The Odawa (also Ottawa or Odaawaa ), said to mean "traders", are an Indigenous American ethnic group who primarily inhabit land in the Eastern Woodlands region, commonly known as the northeastern United States and southeastern Canada. They ha ...

. When Pontiac's Rebellion was defeated in 1766, they generally accepted British sovereignty but retained ownership of their lands, while the Proclamation of 1763 prohibited colonial settlement west of the Appalachians, a grievance that contributed to the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War.

The territory was ceded in 1783 to the new American government, who encouraged its citizens to settle in the region and ignored the rights of local inhabitants. In response, the tribes formed the Northwestern Confederacy which from 1786 to 1795 fought against the US in the Northwest Indian War

The Northwest Indian War (1786–1795), also known by other names, was an armed conflict for control of the Northwest Territory fought between the United States and a united group of Native American nations known today as the Northwestern ...

, with military support provided by British forts along the Maumee River

The Maumee River (pronounced ) ( sjw, Hotaawathiipi; mia, Taawaawa siipiiwi) is a river running in the United States Midwest from northeastern Indiana into northwestern Ohio and Lake Erie. It is formed at the confluence of the St. Joseph and ...

. After the 1794 Jay Treaty, the British handed over these strongpoints to the US, most notably Fort Detroit, and abandoned their indigenous allies, who signed the 1795 Treaty of Greenville with the American government. Under the treaty, they ceded most of what is now the state of Ohio but granted title to the rest of their lands in perpetuity, a commitment the US government had already secretly agreed to ignore.

A key factor in this policy was the acquisition by France of the Louisiana Territory in 1800, which meant the US faced an expansionist power on its northwestern border, rather than a weak Spain. To ensure control of the Upper Mississippi River, President Thomas Jefferson incorporated the region into the Indiana Territory, which originally contained the modern states of Indiana, Illinois, Michigan and Wisconsin. He appointed William Henry Harrison as governor, ordering him to acquire as much land as possible beyond the Greenville line, using deception if needed. In doing so, Harrison was helped by vague and competing claims, since tribes whose title to the lands was either limited or disputed were happy to sign them away in return for bribes. Although the December 1803 Louisiana Purchase ended the French threat, between 1803 and 1805 he obtained extensive territorial cessions in the treaties of Fort Wayne (1803), St Louis, Vincennes and Grouseland.

Tecumseh

Tecumseh ( ; October 5, 1813) was a Shawnee chief and warrior who promoted resistance to the expansion of the United States onto Native American lands. A persuasive orator, Tecumseh traveled widely, forming a Native American confederacy and ...

organized a new confederacy to defend their territory against settler encroachment. They established a community at Prophetstown in 1808, gaining support from young warriors and traditional chiefs including the Wyandot leader Roundhead and Main Poc from the Potawatomi. The Sioux

The Sioux or Oceti Sakowin (; Dakota language, Dakota: Help:IPA, /otʃʰeːtʰi ʃakoːwĩ/) are groups of Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribes and First Nations in Canada, First Nations peoples in North America. The ...

, Sauk, Meskwaki and Ojibwe peoples, who lived along the Upper Mississippi and Western Great Lakes, initially rejected Tenskwatawa's message because of their dependence on the fur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the mos ...

, but continued settler incursions into their lands meant they too became hostile to the U.S.

Britain traditionally maintained good relations with the local people by handing out gifts, including arms and ammunition; after 1795, they ended this policy and advised the tribes to live peacefully with the American government. Their position changed following the 1808 Chesapeake-Leopard Affair, when the Northwest came to be seen as a buffer against an American attack on Upper Canada. They re-started the distribution of gifts and offered the tribes a defensive alliance if war broke out with the US, while urging them to refrain from aggressive action in the meantime. The situation worsened after the 1809 Treaty of Fort Wayne; negotiated primarily with the Lenape, it included lands claimed by the Shawnee and Tecumseh insisted it was invalid without the consent of all the tribes.

Alarmed at the threat posed by Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa, in 1811 Harrison secured permission to attack them. Taking advantage of Tecumseh's absence, he marched on Prophetstown with an army of nearly 1,000 men; in the ensuing Battle of Tippecanoe, the Americans first repulsed an attack by forces under Tenskwatawa, then destroyed Prophetstown. Fighting along the frontier escalated, while Tecumseh reconstituted his confederacy and allied with the British. This action strengthened American hostility against Britain in the run up to the War of 1812, with many blaming them for unrest on the frontier, rather than government policy. in the ensuing conflict, most of the Northwest nations supported the British, including the previously neutral tribes of the Upper Mississippi.

Internal American political conflict

The United States was in a period of significant political conflict between the

The United States was in a period of significant political conflict between the Federalist Party

The Federalist Party was a Conservatism in the United States, conservative political party which was the first political party in the United States. As such, under Alexander Hamilton, it dominated the national government from 1789 to 1801.

De ...

(based mainly in the Northeast) and the Democratic-Republican Party (with its greatest power base in the South and West). The Federalists, who sympathized with Britain and their struggle with Napoleonic France, were criticized by the Democratic-Republicans for being too close to Britain, while the Federalists countered that the Democratic-Republicans were allied to France, a country headed by Napoleon, who was seen as a dictator. The Federalist Party favoured a strong central government and closer ties to Britain while the Democratic-Republican Party favoured a smaller central government, preservation of states' rights (including slavery), westward expansion and a stronger break with Britain. By 1812, the Republicans believed that the Federalists in New England were conspiring with the British who were forming alliances with the various Indian tribes while recruiting "late Loyalists" in Canada, to break up the union. Instead, the war served to alienate the Federalists who were ready to trade and even smuggle with the British rather than to fight them. By 1812, the Federalist Party had weakened considerably and the Republicans were in a strong position, with James Madison completing his first term of office and control of Congress.

Support for the American cause was weak in Federalist areas of the Northeast throughout the war as fewer men volunteered to serve and the banks avoided financing the war. The negativism of the Federalists ruined the party's reputation post-war, as exemplified by the Hartford Convention of 1814–1815, and the party survived only in scattered areas. By 1815, after the victory at the Battle of New Orleans, there was broad support for the war from all parts of the country. This allowed the triumphant Democratic-Republicans to adopt some Federalist policies, such as the national bank, which Madison re-established in 1816.

Forces

American

During the years 1810–1812, American naval ships were divided into two major squadrons, with the "northern division", based at New York, commanded by Commodore John Rodgers, and the "southern division", based at Norfolk, commanded by Commodore Stephen Decatur. Although not much of a threat to Canada in 1812, the United States Navy was a well-trained and professional force comprising over 5,000 sailors and marines. It had 14 ocean-going warships with three of its five "super-frigates" non-operational at the onset of the war. Its principal problem was lack of funding, as many in Congress did not see the need for a strong navy. The biggest ships in the American navy were frigates and there were no ships-of-the-line capable of engaging in a fleet action with the Royal Navy. On the high seas, the Americans pursued a strategy of commerce raiding, capturing or sinking British merchantmen with their frigates and privateers. The Navy was largely concentrated on the Atlantic coast before the war as it had only two gunboats on Lake Champlain, onebrig

A brig is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: two masts which are both square rig, square-rigged. Brigs originated in the second half of the 18th century and were a common type of smaller merchant vessel or warship from then until the ...

on Lake Ontario and another brig in Lake Erie when the war began.

The United States Army was initially much larger than the British Army in North America. Many men carried their own long rifle

The long rifle, also known as the longrifle, Kentucky rifle, Pennsylvania rifle, or American longrifle, a muzzle-loading firearm used for hunting and warfare, was one of the first commonly-used rifles. The American rifle was characterized by a ...

s while the British were issued musket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket gradually d ...

s, except for one unit of 500 riflemen. Leadership was inconsistent in the American officer corps as some officers proved themselves to be outstanding, but many others were inept, owing their positions to political favours. Congress was hostile to a standing army

A standing army is a permanent, often professional, army. It is composed of full-time soldiers who may be either career soldiers or conscripts. It differs from army reserves, who are enrolled for the long term, but activated only during wars or n ...

and the government called out 450,000 men from the state militias during the war. The state militias were poorly trained, armed, and led. The failed invasion of Lake Champlain led by General Dearborn illustrates this. The British Army soundly defeated the Maryland and Virginia militias at the Battle of Bladensburg in 1814 and President Madison commented "I could never have believed so great a difference existed between regular troops and a militia force, if I had not witnessed the scenes of this day".

British

The United States was only a secondary concern to Britain, so long as the war continued with France. In 1813, France had 80 ships-of-the-line and was building another 35. Containing the French fleet was the main British naval concern, leaving only the ships on the North American and Jamaica Stations immediately available. In Upper Canada, the British had the Provincial Marine. While largely unarmed, they were essential for keeping the army supplied since the roads were abysmal in Upper Canada. At the onset of war the Provincial Marine had four small armed vessels on Lake Ontario, three on Lake Erie and one on Lake Champlain. The Provincial Marine greatly outnumbered anything the Americans could bring to bear on the Great Lakes.

When the war broke out, the British Army in North America numbered 9,777 men in regular units and fencibles. While the British Army was engaged in the Peninsular War, few reinforcements were available. Although the British were outnumbered, the long-serving regulars and fencibles were better trained and more professional than the hastily expanded United States Army. The militias of Upper Canada and Lower Canada were initially far less effective, but substantial numbers of full-time militia were raised during the war and played pivotal roles in several engagements, including the Battle of the Chateauguay which caused the Americans to abandon the Saint Lawrence River theatre.

The United States was only a secondary concern to Britain, so long as the war continued with France. In 1813, France had 80 ships-of-the-line and was building another 35. Containing the French fleet was the main British naval concern, leaving only the ships on the North American and Jamaica Stations immediately available. In Upper Canada, the British had the Provincial Marine. While largely unarmed, they were essential for keeping the army supplied since the roads were abysmal in Upper Canada. At the onset of war the Provincial Marine had four small armed vessels on Lake Ontario, three on Lake Erie and one on Lake Champlain. The Provincial Marine greatly outnumbered anything the Americans could bring to bear on the Great Lakes.

When the war broke out, the British Army in North America numbered 9,777 men in regular units and fencibles. While the British Army was engaged in the Peninsular War, few reinforcements were available. Although the British were outnumbered, the long-serving regulars and fencibles were better trained and more professional than the hastily expanded United States Army. The militias of Upper Canada and Lower Canada were initially far less effective, but substantial numbers of full-time militia were raised during the war and played pivotal roles in several engagements, including the Battle of the Chateauguay which caused the Americans to abandon the Saint Lawrence River theatre.

Indigenous peoples