Ambulocetus New NT Small on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Ambulocetus'' (

In December 1991, Pakistani

In December 1991, Pakistani  The Kuldana Formation is constrained to sometime during the

The Kuldana Formation is constrained to sometime during the

Modern cetaceans (Neoceti) are grouped into either the parvorders

Modern cetaceans (Neoceti) are grouped into either the parvorders

Upon description, Thewissen and colleagues suggested the holotype specimen may have weighed the same as a male

Upon description, Thewissen and colleagues suggested the holotype specimen may have weighed the same as a male

Like other archaeocetes which preserve this element, the

Like other archaeocetes which preserve this element, the  Unlike modern toothed whales which only have one kind of tooth (

Unlike modern toothed whales which only have one kind of tooth (

The holotype preserved seven neck vertebrae, which are rather long at . The 16 preserved

The holotype preserved seven neck vertebrae, which are rather long at . The 16 preserved

Unlike modern cetaceans, ''Ambulocetus'' had functional legs which could support the animal's bodyweight on land. The holotype has a robust

Unlike modern cetaceans, ''Ambulocetus'' had functional legs which could support the animal's bodyweight on land. The holotype has a robust

The robustness of the cheek teeth, as well as the cusp arrangement, suggests they were involved in crushing, and the fact that both the premolars and molars were involved in crushing indicates ''Ambulocetus'' required a large area for crushing, such as when biting into large prey items. Similarly, the broad and powerful snout makes it unlikely it was pursuing small, quick prey items (which would have required a narrow snout like dolphins or

The robustness of the cheek teeth, as well as the cusp arrangement, suggests they were involved in crushing, and the fact that both the premolars and molars were involved in crushing indicates ''Ambulocetus'' required a large area for crushing, such as when biting into large prey items. Similarly, the broad and powerful snout makes it unlikely it was pursuing small, quick prey items (which would have required a narrow snout like dolphins or

Thewissen hypothesised that ''Ambulocetus'' was a drag-powered swimmer, and used its huge feet as its primary propulsion mechanism, much like modern river otters including the

Thewissen hypothesised that ''Ambulocetus'' was a drag-powered swimmer, and used its huge feet as its primary propulsion mechanism, much like modern river otters including the

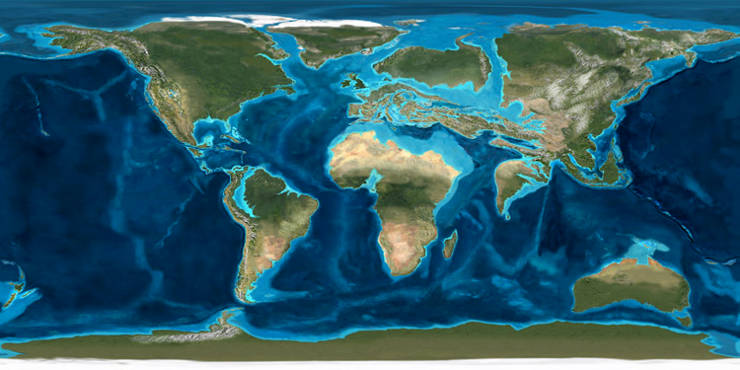

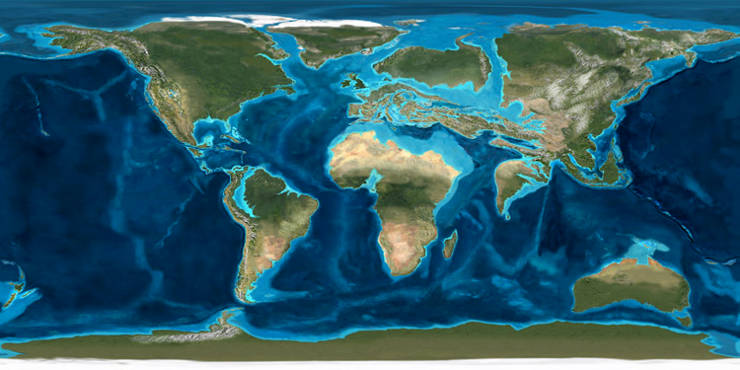

During the Eocene, the Indian subcontinent was an island just beginning its collision with Asia which would eventually lead to the uprising of the

During the Eocene, the Indian subcontinent was an island just beginning its collision with Asia which would eventually lead to the uprising of the

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

''ambulare'' "to walk" + ''cetus'' "whale") is a genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus com ...

of early amphibious cetacean

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals that includes whales, dolphins, and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively carnivorous diet. They propel them ...

from the Kuldana Formation

Kala Chitta Range (in Punjabi and ur, ''Kālā Chiṭṭā'') is a mountain range in the Attock District of Punjab, Pakistan. Kala- Chitta are Punjabi words meaning Kala the Black and Chitta means the white. The range thrusts eastward acros ...

in Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

, roughly 48 or 47 million years ago during the Early Eocene

In the geologic timescale the Ypresian is the oldest age or lowest stratigraphic stage of the Eocene. It spans the time between , is preceded by the Thanetian Age (part of the Paleocene) and is followed by the Eocene Lutetian Age. The Ypresian i ...

(Lutetian

The Lutetian is, in the geologic timescale, a stage or age in the Eocene. It spans the time between . The Lutetian is preceded by the Ypresian and is followed by the Bartonian. Together with the Bartonian it is sometimes referred to as the Midd ...

). It contains one species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

, ''Ambulocetus natans'' (Latin ''natans'' "swimming"), known solely from a single, near-complete fossil. ''Ambulocetus'' is among the best-studied of Eocene cetaceans, and serves as an instrumental find in the study of cetacean evolution and their transition from land to sea, as it was the first cetacean discovered to preserve a suite of adaptations consistent with an amphibious lifestyle. ''Ambulocetus'' is classified in the group Archaeoceti

Archaeoceti ("ancient whales"), or Zeuglodontes in older literature, is a paraphyletic group of primitive cetaceans that lived from the Early Eocene to the late Oligocene (). Representing the earliest cetacean radiation, they include the initia ...

—the ancient forerunners of modern cetaceans whose members span the transition from land to sea—and in the family

Family (from la, familia) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its ...

Ambulocetidae

Ambulocetidae is a family of early cetaceans from Pakistan. The genus ''Ambulocetus'', after which the family is named, is by far the most complete and well-known ambulocetid genus due to the excavation of an 80% complete specimen of ''Ambulocetu ...

, which includes ''Himalayacetus

''Himalayacetus'' is an extinct genus of carnivorous aquatic mammal of the family Ambulocetidae. The holotype was found in Himachal Pradesh, India, (: paleocoordinates ) in what was the remnants of the ancient Tethys Ocean during the Early Eoce ...

'' and ''Gandakasia

''Gandakasia'' is an extinct genus of ambulocetid from Pakistan, that lived in the Eocene epoch. It probably caught its prey near rivers or streams.

Just like ''Himalayacetus'', ''Gandakasia'' is only known from a single jaw fragment, making c ...

'' (also from the Eocene of the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a list of the physiographic regions of the world, physiographical region in United Nations geoscheme for Asia#Southern Asia, Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian O ...

).

''Ambulocetus'' had a narrow, streamlined body, and a long, broad snout, with eyes positioned at the very top of its head. Because of these features, it is hypothesised to have behaved much like a crocodile, waiting near the water's surface to ambush large mammals, using its powerful jaws to clamp onto and drown or thrash prey. Additionally, its ears possessed similar traits to modern cetaceans, which are specialised for hearing and detecting certain frequencies underwater, although it is unclear if ''Ambulocetus'' also used these specialised ears for hearing underwater. They may have instead been utilised for bone conduction

Bone conduction is the conduction of sound to the inner ear primarily through the bones of the skull, allowing the hearer to perceive audio content without blocking the ear canal. Bone conduction transmission occurs constantly as sound waves vibr ...

on land, or perhaps served no function for early cetaceans.

It is thought to have swum much like a modern river otter

Otters are carnivorous mammals in the subfamily Lutrinae. The 13 extant otter species are all semiaquatic, aquatic, or marine, with diets based on fish and invertebrates. Lutrinae is a branch of the Mustelidae family, which also includes wea ...

, tucking in its forelimbs while alternating its hind limbs for propulsion, as well as undulating the torso and tail. It may have had webbed feet

The webbed foot is a specialized limb with interdigital membranes (webbings) that aids in aquatic locomotion, present in a variety of tetrapod vertebrates. This adaptation is primarily found in semiaquatic species, and has convergently evolved m ...

, and unlike its modern relatives, lacked a tail fluke

A fin is a thin component or appendage attached to a larger body or structure. Fins typically function as foils that produce lift or thrust, or provide the ability to steer or stabilize motion while traveling in water, air, or other fluids. Fin ...

. On land, ''Ambulocetus'' may have walked much like a sea lion

Sea lions are pinnipeds characterized by external ear flaps, long foreflippers, the ability to walk on all fours, short and thick hair, and a big chest and belly. Together with the fur seals, they make up the family Otariidae, eared seals. ...

.

''Ambulocetus'' inhabited the Indian subcontinent during the Eocene. The area had a hot climate with tropical rainforest

Tropical rainforests are rainforests that occur in areas of tropical rainforest climate in which there is no dry season – all months have an average precipitation of at least 60 mm – and may also be referred to as ''lowland equatori ...

s and coastal mangrove

A mangrove is a shrub or tree that grows in coastal saline water, saline or brackish water. The term is also used for tropical coastal vegetation consisting of such species. Mangroves are taxonomically diverse, as a result of convergent evoluti ...

s, and ''Ambulocetus'' may have predominantly inhabited brackish

Brackish water, sometimes termed brack water, is water occurring in a natural environment that has more salinity than freshwater, but not as much as seawater. It may result from mixing seawater (salt water) and fresh water together, as in estuari ...

areas such as river mouth

A river mouth is where a river flows into a larger body of water, such as another river, a lake/reservoir, a bay/gulf, a sea, or an ocean. At the river mouth, sediments are often deposited due to the slowing of the current reducing the carrying ...

s . It lived alongside requiem shark

Requiem sharks are sharks of the family Carcharhinidae in the order Carcharhiniformes. They are migratory, live-bearing sharks of warm seas (sometimes of brackish or fresh water) and include such species as the tiger shark, bull shark, le ...

s, catfish

Catfish (or catfishes; order Siluriformes or Nematognathi) are a diverse group of ray-finned fish. Named for their prominent barbels, which resemble a cat's whiskers, catfish range in size and behavior from the three largest species alive, ...

and various other fishes, turtle

Turtles are an order of reptiles known as Testudines, characterized by a special shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Cryptodira (hidden necked tu ...

s, crocodile

Crocodiles (family (biology), family Crocodylidae) or true crocodiles are large semiaquatic reptiles that live throughout the tropics in Africa, Asia, the Americas and Australia. The term crocodile is sometimes used even more loosely to inclu ...

s, the amphibious hoofed mammal ''Anthracobune

''Anthracobune'' ("coal mound") is an extinct genus of stem perissodactyl from the middle Eocene of the Upper Kuldana Formation of Kohat, Punjab, Pakistan.

The size of a small tapir, it lived in a marshy environment and fed on soft aquatic plant ...

'', and the fellow cetaceans ''Gandakasia'', ''Attockicetus

''Attockicetus'' is an extinct genus of remingtonocetid early whale known from the Middle Eocene (Lutetian) Kuldana Formation in the Kala Chitta Hills, in the Attock District of Punjab, Pakistan.

''Attockicetus'' is described based on frag ...

'', ''Nalacetus

''Nalacetus'' is an extinct pakicetid early whale, fossils of which have been found in Lutetian red beds in Punjab, Pakistan (, paleocoordinates ).. Retrieved June 2013.. Retrieved June 2013. ''Nalacetus'' lived in a fresh water environment, w ...

'', and ''Pakicetus

''Pakicetus'' is an extinct genus of amphibious cetacean of the family Pakicetidae, which was endemic to Pakistan during the Eocene, about 50 million years ago. It was a wolf-like animal, about to long, and lived in and around water where it a ...

''.

Taxonomy

Discovery

In December 1991, Pakistani

In December 1991, Pakistani palaeontologist

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

Mohammad Arif and Dutch–American palaeontologist Hans Thewissen

Hans Thewissen is a Dutch-American paleontologist.

His field work has discovered fossils for the steps in the transition from land to water in whales: '' Ambulocetus'', '' Pakicetus'', ''Indohyus'' and '' Kutchicetus''. He now studies modern b ...

were jointly funded by Howard University

Howard University (Howard) is a private, federally chartered historically black research university in Washington, D.C. It is classified among "R2: Doctoral Universities – High research activity" and accredited by the Middle States Commissi ...

and the Geological Survey of Pakistan

Geological Survey of Pakistan (GSP) is an independent executive scientific agency to explore the natural resources of Pakistan. Main tasks GSP perform are Geological, Geophysical and Geo-chemical Mapping of Pakistan. Target of these mapping are res ...

to recover land mammal fossils in the Kala Chitta Hills of Punjab

Punjab (; Punjabi: پنجاب ; ਪੰਜਾਬ ; ; also romanised as ''Panjāb'' or ''Panj-Āb'') is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising ...

, Pakistan. On 3 January 1992, they recovered a small, thick rib

In vertebrate anatomy, ribs ( la, costae) are the long curved bones which form the rib cage, part of the axial skeleton. In most tetrapods, ribs surround the chest, enabling the lungs to expand and thus facilitate breathing by expanding the ches ...

fragment. Later in the field season, while surveying the upper Kuldana Formation

Kala Chitta Range (in Punjabi and ur, ''Kālā Chiṭṭā'') is a mountain range in the Attock District of Punjab, Pakistan. Kala- Chitta are Punjabi words meaning Kala the Black and Chitta means the white. The range thrusts eastward acros ...

, Thewissen discovered a femur

The femur (; ), or thigh bone, is the proximal bone of the hindlimb in tetrapod vertebrates. The head of the femur articulates with the acetabulum in the pelvic bone forming the hip joint, while the distal part of the femur articulates with ...

(thigh bone) and proximal portion of the tibia

The tibia (; ), also known as the shinbone or shankbone, is the larger, stronger, and anterior (frontal) of the two bones in the leg below the knee in vertebrates (the other being the fibula, behind and to the outside of the tibia); it connects ...

(upper portion of the shin) which clearly belonged to a mammal. An hour later, Arif discovered the rest of the skeleton, and the two began excavation the next day. At first, Thewissen speculated the fossils belonged to an anthracobunid

Anthracobunidae is an extinct family of stem perissodactyls that lived in the early to middle Eocene period. They were originally considered to be a paraphyletic family of primitive proboscideans possibly ancestral to the Moeritheriidae and the ...

(a large semi-aquatic mammal), until he found the teeth near the end of the field season, which were characteristically cetacea

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals that includes whales, dolphins, and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively carnivorous diet. They propel them ...

n (living cetaceans are whale

Whales are a widely distributed and diverse group of fully aquatic placental marine mammals. As an informal and colloquial grouping, they correspond to large members of the infraorder Cetacea, i.e. all cetaceans apart from dolphins and ...

s, dolphin

A dolphin is an aquatic mammal within the infraorder Cetacea. Dolphin species belong to the families Delphinidae (the oceanic dolphins), Platanistidae (the Indian river dolphins), Iniidae (the New World river dolphins), Pontoporiidae (the ...

s, and porpoise

Porpoises are a group of fully aquatic marine mammals, all of which are classified under the family Phocoenidae, parvorder Odontoceti (toothed whales). Although similar in appearance to dolphins, they are more closely related to narwhals an ...

s). Thewissen, at the time, could not afford to excavate and store everything, so he took the skull with him to the United States, while Arif kept the rest in two crates which used to hold oranges

An orange is a fruit of various citrus species in the family Rutaceae (see list of plants known as orange); it primarily refers to ''Citrus'' × ''sinensis'', which is also called sweet orange, to distinguish it from the related ''Citrus × ...

. In October 1992, Thewissen presented his research of the skull to a vertebrate palaeontology convention in Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the ancho ...

, Canada. The next year, American palaeontologist Philip D. Gingerich

Philip Dean Gingerich (born March 23, 1946) is a paleontologist and educator. He is Professor Emeritus of Geology, Biology, and Anthropology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He directed the Museums at the University of Michigan#Museum ...

paid for the rest of the skeleton to be shipped to the United States. In 1994, the formal description of the remains was published by Thewissen, mammal palaeontologist Sayed Taseer Hussain, and Arif. They identified the remains as clearly belonging to an amphibious cetacean, and so they named it ''Ambulocetus natans''. The genus name comes from Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

''ambulare'' "to walk" and ''cetus'' "whale", and the species name ''natans'' "swimming".

The Kuldana Formation is constrained to sometime during the

The Kuldana Formation is constrained to sometime during the Lutetian

The Lutetian is, in the geologic timescale, a stage or age in the Eocene. It spans the time between . The Lutetian is preceded by the Ypresian and is followed by the Bartonian. Together with the Bartonian it is sometimes referred to as the Midd ...

stage

Stage or stages may refer to:

Acting

* Stage (theatre), a space for the performance of theatrical productions

* Theatre, a branch of the performing arts, often referred to as "the stage"

* ''The Stage'', a weekly British theatre newspaper

* Sta ...

of the Early Eocene

In the geologic timescale the Ypresian is the oldest age or lowest stratigraphic stage of the Eocene. It spans the time between , is preceded by the Thanetian Age (part of the Paleocene) and is followed by the Eocene Lutetian Age. The Ypresian i ...

, and the remains may date to 48–47 million years ago. The holotype specimen

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of several ...

, HGSP 18507, is a partial skeleton initially discovered preserving an incomplete skull (missing the snout), some elements of the vertebral column

The vertebral column, also known as the backbone or spine, is part of the axial skeleton. The vertebral column is the defining characteristic of a vertebrate in which the notochord (a flexible rod of uniform composition) found in all chordata, ...

and ribs, as well as portions of the fore- and hind-limb. Other specimens initially found were HGSP 18473 (a second premolar

The premolars, also called premolar teeth, or bicuspids, are transitional teeth located between the canine and molar teeth. In humans, there are two premolars per quadrant in the permanent set of teeth, making eight premolars total in the mouth ...

), HGSP 18497 (a third premolar), HGSP 18472 (a tail vertebra), and HGSP 18476 (lower portion of a femur). The holotype was found in a silt

Silt is granular material of a size between sand and clay and composed mostly of broken grains of quartz. Silt may occur as a soil (often mixed with sand or clay) or as sediment mixed in suspension with water. Silt usually has a floury feel when ...

and mudstone

Mudstone, a type of mudrock, is a fine-grained sedimentary rock whose original constituents were clays or muds. Mudstone is distinguished from '' shale'' by its lack of fissility (parallel layering).Blatt, H., and R.J. Tracy, 1996, ''Petrology. ...

bed

A bed is an item of furniture that is used as a place to sleep, rest, and relax.

Most modern beds consist of a soft, cushioned mattress on a bed frame. The mattress rests either on a solid base, often wood slats, or a sprung base. Many beds ...

over a area. Further excavation recovered most of the holotype's skeleton—most notably the hip, sacrum

The sacrum (plural: ''sacra'' or ''sacrums''), in human anatomy, is a large, triangular bone at the base of the spine that forms by the fusing of the sacral vertebrae (S1S5) between ages 18 and 30.

The sacrum situates at the upper, back part ...

, and most of ribcage and thoracolumbar series (the spine excluding the neck, sacrum, and tail). These left the holotype about 80% complete by 2002, making it the most completely known cetacean from the time period. In 2009, some more elements of the holotype's jawbone were identified from a then-recently prepared matrix

Matrix most commonly refers to:

* ''The Matrix'' (franchise), an American media franchise

** ''The Matrix'', a 1999 science-fiction action film

** "The Matrix", a fictional setting, a virtual reality environment, within ''The Matrix'' (franchis ...

block.

Though it was known that cetaceans descended from land mammals before the discovery of ''Ambulocetus'', the only evidence of this in the fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

record was the 52-million-year-old (fully terrestrial) ''Pakicetus

''Pakicetus'' is an extinct genus of amphibious cetacean of the family Pakicetidae, which was endemic to Pakistan during the Eocene, about 50 million years ago. It was a wolf-like animal, about to long, and lived in and around water where it a ...

'' and the Paleocene

The Paleocene, ( ) or Palaeocene, is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 66 to 56 mya (unit), million years ago (mya). It is the first epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), E ...

mesonychid

Mesonychia ("middle claws") is an extinct taxon of small- to large-sized carnivorous ungulates related to artiodactyls. Mesonychids first appeared in the early Paleocene, went into a sharp decline at the end of the Eocene, and died out entirely ...

s (as there was a hypothesised link between cetaceans and mesonychids). The limbs of more aquatic Eocene cetaceans did not preserve very well. ''Ambulocetus'' demonstrated that cetaceans swam by flexing the spine up and down (undulation) before they had evolved the tail fluke

A fin is a thin component or appendage attached to a larger body or structure. Fins typically function as foils that produce lift or thrust, or provide the ability to steer or stabilize motion while traveling in water, air, or other fluids. Fin ...

, forelimb propulsion

Propulsion is the generation of force by any combination of pushing or pulling to modify the translational motion of an object, which is typically a rigid body (or an articulated rigid body) but may also concern a fluid. The term is derived from ...

evolved relatively late, and that cetaceans went through an otter

Otters are carnivorous mammals in the subfamily Lutrinae. The 13 extant otter species are all semiaquatic, aquatic, or marine, with diets based on fish and invertebrates. Lutrinae is a branch of the Mustelidae family, which also includes wea ...

-like phase with spinal undulation and hindlimb propulsion. These had already been hypothesised to have occurred in the earliest aquatic cetaceans, but were impossible to test without more complete remains. The describers noted that, "''Ambulocetus'' represents a critical intermediate between land mammals and marine cetaceans."

Classification

Modern cetaceans (Neoceti) are grouped into either the parvorders

Modern cetaceans (Neoceti) are grouped into either the parvorders Mysticeti

Baleen whales (systematic name Mysticeti), also known as whalebone whales, are a parvorder of carnivorous marine mammals of the infraorder Cetacea (whales, dolphins and porpoises) which use keratinaceous baleen plates (or "whalebone") in their ...

(baleen whales) or Odontoceti

The toothed whales (also called odontocetes, systematic name Odontoceti) are a parvorder of cetaceans that includes dolphins, porpoises, and all other whales possessing teeth, such as the beaked whales and sperm whales. Seventy-three species of ...

(toothed whales). Neoceti are descended from the ancient Archaeoceti

Archaeoceti ("ancient whales"), or Zeuglodontes in older literature, is a paraphyletic group of primitive cetaceans that lived from the Early Eocene to the late Oligocene (). Representing the earliest cetacean radiation, they include the initia ...

, whose members span the transition from terrestrial to fully aquatic. Archaeoceti are thus paraphyletic

In taxonomy (general), taxonomy, a group is paraphyletic if it consists of the group's most recent common ancestor, last common ancestor and most of its descendants, excluding a few Monophyly, monophyletic subgroups. The group is said to be pa ...

(it is a non-natural group which does not comprise both a common ancestor and all of its descendants). ''Ambulocetus'' was an archaeocete. By the time ''Ambulocetus'' was discovered, archaeocetes were classified into the families

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Ideall ...

Protocetidae

Protocetidae, the protocetids, form a diverse and heterogeneous group of extinct cetaceans known from Asia, Europe, Africa, South America, and North America.

Description

There were many genera, and some of these are very well known (e.g., ''Ro ...

(which included what are now the terrestrial Pakicetidae

Pakicetidae ("Pakistani whales") is an extinct family of Archaeoceti (early whales) that lived during the Early Eocene in Pakistan.

Description

described the first pakicetid, '' Ichthyolestes'', but at the time they did not recognize it as a ce ...

, and the rest were amphibious), Remingtonocetidae

Remingtonocetidae is a diverse family of early aquatic mammals of the order Cetacea. The family is named after paleocetologist Remington Kellogg.

Description

Remingtonocetids have long and narrow skulls with the external nare openings located ...

(amphibious), Basilosauridae

Basilosauridae is a family of extinct cetaceans. They lived during the middle to the early late Eocene and are known from all continents, including Antarctica. They were probably the first fully aquatic cetaceans.Buono M, Fordyce R.E., Marx F.G. ...

(aquatic), and Dorudontidae

Dorudontinae are a group of extinct cetaceans that are related to ''Basilosaurus''.. Retrieved July 2013.

Classification

* Subfamily Dorudontinae

** Genus ''Ancalecetus''

*** ''Ancalecetus simonsi''

** Genus ''Chrysocetus''

*** ''Chrysocetus ...

(aquatic, now a subfamily of Basilosauridae). The earliest cetaceans were thought to be the mesonychids, proposed before any firm early cetacean fossils were identified. In the original description, ''Ambulocetus'' was preliminarily placed into Protocetidae, until the further description of the holotype prompted Thewissen and colleagues to move it into its own family Ambulocetidae

Ambulocetidae is a family of early cetaceans from Pakistan. The genus ''Ambulocetus'', after which the family is named, is by far the most complete and well-known ambulocetid genus due to the excavation of an 80% complete specimen of ''Ambulocetu ...

in 1996. At the same time, they also erected the family Pakicetidae. They also proposed that some members of Pakicetidae, Protocetidae, and Ambulocetidae were the other two archaeocete families' ancestors. They suggested that mesonychids gave rise to pakicetids, which gave rise to ambulocetids, which gave rise to both protocetids and remingtonocetids.

Though middle-to-late-Eocene archaeocetes are also known from North America, Europe, and Africa, most of these are found only on the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a list of the physiographic regions of the world, physiographical region in United Nations geoscheme for Asia#Southern Asia, Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian O ...

. Therefore, it is thought cetaceans originally evolved in that region. Based on molecular data, cetaceans are most closely allied with hippo

The hippopotamus ( ; : hippopotamuses or hippopotami; ''Hippopotamus amphibius''), also called the hippo, common hippopotamus, or river hippopotamus, is a large semiaquatic mammal native to sub-Saharan Africa. It is one of only two extant ...

s (Whippomorpha

Whippomorpha or Cetancodonta is a group of animals that contains all living cetaceans (whales, dolphins, etc.) and hippopotamuses, as well as their extinct relatives, i.e. Entelodont, Entelodonts and Andrewsarchus. All Whippomorphs are descendan ...

), and they split approximately 54.9 million years ago. They are all placed in the order

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* Heterarchy, a system of organization wherein the elements have the potential to be ranked a number of d ...

Cetartiodactyla

The even-toed ungulates (Artiodactyla , ) are ungulates—hoofed animals—which bear weight equally on two (an even number) of their five toes: the third and fourth. The other three toes are either present, absent, vestigial, or pointing poster ...

alongside terrestrial even-toed ungulates (hoofed mammals). This puts mesonychids as a distant relative of cetaceans rather than an ancestor, and their somewhat similar morphology was possibly a result of convergent evolution

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last com ...

. The oldest known cetacean is the ambulocetid ''Himalayacetus

''Himalayacetus'' is an extinct genus of carnivorous aquatic mammal of the family Ambulocetidae. The holotype was found in Himachal Pradesh, India, (: paleocoordinates ) in what was the remnants of the ancient Tethys Ocean during the Early Eoce ...

'' identified in 1998 and dated to 52.5 million years ago (predating the terrestrial pakicetids), though the exact dating of ''Himalayacetus'' and ''Pakicetus'' is debated. Ambulocetidae also includes ''Gandakasia

''Gandakasia'' is an extinct genus of ambulocetid from Pakistan, that lived in the Eocene epoch. It probably caught its prey near rivers or streams.

Just like ''Himalayacetus'', ''Gandakasia'' is only known from a single jaw fragment, making c ...

''. ''Himalayacetus'' and ''Gandakasia'' are known only from partial jaw fragments. Ambulocetidae are endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found elsew ...

to the Indian subcontinent, and span the early to middle Eocene.

Description

Size

Upon description, Thewissen and colleagues suggested the holotype specimen may have weighed the same as a male

Upon description, Thewissen and colleagues suggested the holotype specimen may have weighed the same as a male South American sea lion

The South American sea lion (''Otaria flavescens'', formerly ''Otaria byronia''), also called the southern sea lion and the Patagonian sea lion, is a sea lion found on the western and southeastern coasts of South America. It is the only member ...

— about — based on the size of the vertebrae, ribs, and limbs. They also estimated a length of roughly . For comparison, the holotype of ''Pakicetus attocki'' may have been long. In 1996, they estimated weight of ''Ambulocetus'', using the cross-sections of the long bones, as . Alternatively, they estimated about by using the length of the second upper and lower molars compared to trends between this length and ungulate body mass. They obtained the same result comparing the skull size to those of similarly sized carnivores. In 1998, based on vertebral size, Gingerich estimated a body mass of , similar to modern cetaceans. In 2013, Thewissen suggested that this may be an unreliable mass determinant as the vertebrae are unusually robust in ''Ambulocetus''.

Skull

base of the skull

The base of skull, also known as the cranial base or the cranial floor, is the most inferior area of the skull. It is composed of the endocranium and the lower parts of the calvaria.

Structure

Structures found at the base of the skull are for ...

has an undulating contour, probably related to the shape of the nasal canal (and its passage to the throat) and the narrow infraorbital region (the area below the eyes). The base of the skull is wide compared to other archaeocetes, more like that of modern cetaceans. The narrow infraorbital space, made of primarily the pterygoid processes

The pterygoid processes of the sphenoid (from Greek ''pteryx'', ''pterygos'', "wing"), one on either side, descend perpendicularly from the regions where the body and the greater wings of the sphenoid bone unite.

Each process consists of a medi ...

, also occurs in ''Remingtonocetus

''Remingtonocetus'' is an extinct genus of early cetacean freshwater aquatic mammals of the family Remingtonocetidae endemic to the coastline of the ancient Tethys Ocean during the Eocene. It was named after naturalist Remington Kellogg.

History ...

'' and ''Pakicetus''. The pterygoids connect as far back as the middle ear

The middle ear is the portion of the ear medial to the eardrum, and distal to the oval window of the cochlea (of the inner ear).

The mammalian middle ear contains three ossicles, which transfer the vibrations of the eardrum into waves in the ...

, much farther than other archaeocetes including the more ancient ''Pakicetus''. Most modern cetaceans have a falcate (sickle-shaped) process which juts out prominently halfway between the hypoglossal canal

The hypoglossal canal is a foramen in the occipital bone of the skull. It is hidden medially and superiorly to each occipital condyle. It transmits the hypoglossal nerve.

Structure

The hypoglossal canal lies in the epiphyseal junction between ...

and the ear; ''Ambulocetus'' has a similar process continuous of the pterygoid Pterygoid, from the Greek for 'winglike', may refer to:

* Pterygoid bone, a bone of the palate of many vertebrates

* Pterygoid processes of the sphenoid bone

** Lateral pterygoid plate

** Medial pterygoid plate

* Lateral pterygoid muscle

* Medial ...

, but it runs alongside and behind the hypoglossal canal. Like many other archaeocetes, the pterygoids, sphenoids, and palatines

Palatines (german: Pfälzer), also known as the Palatine Dutch, are the people and princes of Palatinates ( Holy Roman principalities) of the Holy Roman Empire. The Palatine diaspora includes the Pennsylvania Dutch and New York Dutch.

In 1709 ...

form a wall lining the bottom of the nasal canal, which causes the palate

The palate () is the roof of the mouth in humans and other mammals. It separates the oral cavity from the nasal cavity.

A similar structure is found in crocodilians, but in most other tetrapods, the oral and nasal cavities are not truly sepa ...

to extend all the way to the ear. Like other cetaceans, ''Ambulocetus'' lacks the postglenoid foramen, which usually is one of the main passageways for veins into the skull in placental mammals

Placental mammals (infraclass Placentalia ) are one of the three extant subdivisions of the class Mammalia, the other two being Monotremata and Marsupialia. Placentalia contains the vast majority of extant mammals, which are partly distinguishe ...

. The ectotympanic The ectotympanic, or tympanicum, is a bony structure found in all mammals, located on the tympanic part of the temporal bone, which holds the tympanic membrane (eardrum) in place. In catarrhine primates (including humans), it takes a tube-shape. I ...

bone which supports the eardrum is similar to that of ''Pakicetus'', about as long as wide, whereas later archaeocetes have more elongate ectotympanics. The ectotympanics of all archaeocetes, nonetheless, are much different than those of terrestrial mammals. The ectotympanics of all cetaceans, including ''Ambulocetus'', possess an involucrum

An involucrum (plural involucra) is a layer of new bone growth outside existing bone.

There are two main contexts:

* In pyogenic osteomyelitis where it is a layer of living bone that has formed about dead bone. It can be identified by radiograph ...

(thickened lump of bone) at the medial lip. Unlike ''Pakicetus'', but like later archaeocetes, the tympanic made close contact with the jaw. Like later archaeocetes, ''Ambulocetus'' seems to have possessed an air sinus

Sinus may refer to:

Anatomy

* Sinus (anatomy), a sac or cavity in any organ or tissue

** Paranasal sinuses, air cavities in the cranial bones, especially those near the nose, including:

*** Maxillary sinus, is the largest of the paranasal sinuses, ...

in the pterygoids. It may have also had paranasal sinuses

Paranasal sinuses are a group of four paired air-filled spaces that surround the nasal cavity. The maxillary sinuses are located under the eyes; the frontal sinuses are above the eyes; the ethmoidal sinuses are between the eyes and the sphenoid ...

. The parietal bone

The parietal bones () are two bones in the Human skull, skull which, when joined at a fibrous joint, form the sides and roof of the Human skull, cranium. In humans, each bone is roughly quadrilateral in form, and has two surfaces, four borders, an ...

s on the braincase sides are more perpendicular than in ''Remingtonocetus'', which makes the cheeks appear less flared. Like ''Remingtonocetus'', ''Ambulocetus'' appears to have had a small brain.

The snout was quite broad, but the end of the holotype's snout is missing, so it is unclear how long it would have been. The snouts of ''Basilosaurus

''Basilosaurus'' (meaning "king lizard") is a genus of large, predatory, prehistoric archaeocete whale from the late Eocene, approximately 41.3 to 33.9 million years ago (mya). First described in 1834, it was the first archaeocete and prehistori ...

'' and ''Rodhocetus'' are short and make up about half the skull's length. Remingtonocetid snouts are quite narrow, which was clearly not the case for ''Ambulocetus''. The mandibular symphysis

In human anatomy, the facial skeleton of the skull the external surface of the mandible is marked in the median line by a faint ridge, indicating the mandibular symphysis (Latin: ''symphysis menti'') or line of junction where the two lateral halves ...

of most mammals is restricted to the midline of the jaw, but extends much farther in archaeocetes; in ''Ambulocetus'', it reaches the back end of the first premolar. Snout robustness and symphysis length suggest reinforcement of the jaw to withstand a strong bite force. Similarly, the strongest biting muscle in ''Ambulocetus'' seems to have been the temporalis muscle

In anatomy, the temporalis muscle, also known as the temporal muscle, is one of the muscles of mastication (chewing). It is a broad, fan-shaped convergent muscle on each side of the head that fills the temporal fossa, superior to the zygomati ...

involved in biting down. Like other cetaceans, there are embrasure

An embrasure (or crenel or crenelle; sometimes called gunhole in the domain of gunpowder-era architecture) is the opening in a battlement between two raised solid portions (merlons). Alternatively, an embrasure can be a space hollowed out ...

pits (a depression between the teeth), preserving the tooth positions for the fourth premolar, the first molar, and the third molar. Unlike later archaeocetes, the molars' roots do not extend to the cheek bone

In the human skull, the zygomatic bone (from grc, ζῠγόν, zugón, yoke), also called cheekbone or malar bone, is a paired irregular bone which articulates with the maxilla, the temporal bone, the sphenoid bone and the frontal bone. It is si ...

s, and the third molar is not as nosewards as in remingtonocetids. The coronoid process of the mandible

In human anatomy, the mandible's coronoid process (from Greek ''korōnē'', denoting something hooked) is a thin, triangular eminence, which is flattened from side to side and varies in shape and size. Its anterior border is convex and is continuou ...

(where the lower jaw connects with the skull) in ''Ambulocetus'' is steep. In contrast, it is low and slopes gently down in basilosaurids and later cetaceans. The mandibular foramen

The mandibular foramen is an opening on the internal surface of the ramus of the mandible. It allows for divisions of the mandibular nerve and blood vessels to pass through.

Structure

The mandibular foramen is an opening on the internal surfa ...

opens below the coronoid process, and is around midway between terrestrial mammals and toothed whales in size. Like other cetaceans, the body of the hyoid bone

The hyoid bone (lingual bone or tongue-bone) () is a horseshoe-shaped bone situated in the anterior midline of the neck between the chin and the thyroid cartilage. At rest, it lies between the base of the mandible and the third cervical vertebr ...

(the basihyoid bone) is about as long as wide. Unlike other archaeocetes, the eyes are quite large and are placed near the top of the head facing upwards.

homodont

In anatomy, a heterodont (from Greek, meaning 'different teeth') is an animal which possesses more than a single tooth morphology.

In vertebrates, heterodont pertains to animals where teeth are differentiated into different forms. For example ...

), archaeocetes are heterodont

In anatomy, a heterodont (from Greek, meaning 'different teeth') is an animal which possesses more than a single tooth morphology.

In vertebrates, heterodont pertains to animals where teeth are differentiated into different forms. For example, ...

. Judging by tooth root

Dental anatomy is a field of anatomy dedicated to the study of Tooth (human), human tooth structures. The development, appearance, and classification of teeth fall within its purview. (The function of teeth as they contact one another falls elsewh ...

size, the lower canine was larger than the incisors. The teeth are more robust than those of ''Rodhocetus'' and ''Basilosaurus''. The premolars were double rooted, whereas most archaeocetes have single-rooted first premolars. The enamel of the lower premolars is crenulated (has scalloped edges). The fourth premolar is a high triangular shape. Like other ancient cetaceans, and most pronouncedly in ambulocetids, the lower molars are shorter than the back premolars. The lower premolars are larger than those of ''Pakicetus'' and are separated by wider gaps (diastema

A diastema (plural diastemata, from Greek διάστημα, space) is a space or gap between two teeth. Many species of mammals have diastemata as a normal feature, most commonly between the incisors and molars. More colloquially, the condition ...

ta). The molars had distinct trigonid and talonid cusps (these cusps are lost in basilosaurids), and the upper molars were trituberculate like ancient archaeocetes and ancient placental mammals, meaning they had a large protocone

A cusp is a pointed, projecting, or elevated feature. In animals, it is usually used to refer to raised points on the crowns of teeth.

The concept is also used with regard to the leaflets of the four heart valves. The mitral valve, which has two ...

, distinct paracone

A paracone is a 1960s atmospheric reentry or spaceflight mission abort concept using an inflatable ballistic cone.metacone

A cusp is a pointed, projecting, or elevated feature. In animals, it is usually used to refer to raised points on the crowns of teeth.

The concept is also used with regard to the leaflets of the four heart valves. The mitral valve, which has two ...

, and no accessory cusps. Later archaeocetes developed accessory cusps.

Ribs and vertebrae

The holotype preserved seven neck vertebrae, which are rather long at . The 16 preserved

The holotype preserved seven neck vertebrae, which are rather long at . The 16 preserved thoracic vertebrae

In vertebrates, thoracic vertebrae compose the middle segment of the vertebral column, between the cervical vertebrae and the lumbar vertebrae. In humans, there are twelve thoracic vertebra (anatomy), vertebrae and they are intermediate in size b ...

have thick spinous and transverse processes (which jut upwards and obliquely from the centrum, the vertebral body), with deep depressions on both sides at the tail-end of each centrum which may have supported strong longissimus

The longissimus ( la, the longest one) is the muscle lateral to the semispinalis muscles. It is the longest subdivision of the erector spinae muscles that extends forward into the transverse processes of the posterior cervical vertebrae.

Structur ...

muscles which flex the spine. The thoracic vertebrae become longer and wider tailwards and are tallest mid-series. In front-view (anterior aspect), the centra go from heart-shaped to kidney-shaped by T8 (the eighth thoracic vertebra). The pedicals (between the centrum and a transverse process) feature deep grooves. The spinous processes project tailwards from T1–T9, straight up at T10, headwards from T11 to T12, and the rest project straight up. The spinous processes progressively increase in length and width from T11–T16. T10 seems to have been at the level of the thoracic diaphragm

The thoracic diaphragm, or simply the diaphragm ( grc, διάφραγμα, diáphragma, partition), is a sheet of internal Skeletal striated muscle, skeletal muscle in humans and other mammals that extends across the bottom of the thoracic cavit ...

. T1–T12 and T14 have capitular facets on the top margin of both the frontward and tailward side to join with the ribs. T15 and T16 have capitular facets on the headward side and lack transverse processes. T11–T15 have accessory anapophyses which jut straight up from the top border between the centrum and the transverse processes; and in T16, these are small, originate near the pedicles, and project tailwards. The width between articular processes

The articular processes or zygapophyses (Greek ζυγον = "yoke" (because it links two vertebrae) + απο = "away" + φυσις = "process") of a vertebra are projections of the vertebra that serve the purpose of fitting with an adjacent vertebr ...

(two masses of bone which jut out of each centrum to connect with the next centrum) continually increases through the thoracolumbar series. In life, it is possible it had up to 17 thoracic vertebrae.

The holotype preserves 26 ribs, though it is thought to have had 32 total in life. The cortical bone

A bone is a rigid organ that constitutes part of the skeleton in most vertebrate animals. Bones protect the various other organs of the body, produce red and white blood cells, store minerals, provide structure and support for the body, and ...

(the outermost layer) is thickest at the neck of the rib (between the joint and the costal cartilage

The costal cartilages are bars of hyaline cartilage that serve to prolong the ribs forward and contribute to the elasticity of the walls of the thorax. Costal cartilage is only found at the anterior ends of the ribs, providing medial extension.

...

), at max , and was filled with spongy bone. That is, unlike many other aquatic mammals, the ribs did not exhibit osteosclerosis

Osteosclerosis is a disorder that is characterized by abnormal hardening of bone and an elevation in bone density. It may predominantly affect the medullary portion and/or cortex of bone. Plain radiographs are a valuable tool for detecting and ...

. They did exhibit pachyostosis

Pachyostosis is a non-pathological condition in vertebrate animals in which the bones experience a thickening, generally caused by extra layers of lamellar bone. It often occurs together with bone densification (osteosclerosis), reducing inner ca ...

, and were made thicker and heavier with additional layers of lamellar bone. The ribs' shape indicates ''Ambulocetus'' had a narrow and heart-shaped thorax

The thorax or chest is a part of the anatomy of humans, mammals, and other tetrapod animals located between the neck and the abdomen. In insects, crustaceans, and the extinct trilobites, the thorax is one of the three main divisions of the cre ...

looking at it head-on. Ribs are thickest at the T8–T10 level. Ribs are broadest at the sternum

The sternum or breastbone is a long flat bone located in the central part of the chest. It connects to the ribs via cartilage and forms the front of the rib cage, thus helping to protect the heart, lungs, and major blood vessels from injury. Sh ...

, which suggests strong sternocostal joints

The sternocostal joints, also known as sternochondral joints or costosternal articulations, are synovial plane joints of the costal cartilages of the true ribs with the sternum. The only exception is the first rib, which has a synchondrosis joint ...

. The ribs have a slight S-curve in side view, with the rib heads angled headwards, and the sternocostal joints angled tailwards. The holotype preserves a central and a tailward sternum bone which are both exceedingly thick, about on the outer margins and decreasing towards the centre. The central sternum bone is longer and wider than the tailward one.

The eight preserved lumbar vertebrae at the lower back are much longer than the thoracic, and the centra and transverse processes, from L1–L7, continually increase in length and height. The short transverse processes on L8 are probably due to its proximity to the ilium on the hip. The undersides are concave. The spinous processes are long and tall, and project headward from L1–L5, and straight-up from L6–L8. The spinous processes are bulbous on the tailward side to support epaxial

In adult vertebrates, trunk muscles can be broadly divided into hypaxial muscles, which lie ventral to the horizontal septum of the vertebrae and epaxial muscles, which lie dorsal to the septum. Hypaxial muscles include some vertebral muscles, the ...

muscles. The vertebral laminae are excavated headward to support the interspinous ligament

The interspinous ligaments (interspinal ligaments) are thin and membranous ligaments, that connect adjoining spinous processes of the vertebra in the spine.

They extend from the root to the apex of each spinous process. They meet the ligamenta fla ...

s which connect the spinous processes. The vertebrae are about as robust as those of modern pinniped such as sow leopard seal

The leopard seal (''Hydrurga leptonyx''), also referred to as the sea leopard, is the second largest species of seal in the Antarctic (after the southern elephant seal). Its only natural predator is the orca. It feeds on a wide range of prey incl ...

s and bull walrus

The walrus (''Odobenus rosmarus'') is a large pinniped, flippered marine mammal with a discontinuous distribution about the North Pole in the Arctic Ocean and subarctic seas of the Northern Hemisphere. The walrus is the only living species in ...

es. The postzygapophyses (the surface where the vertebrae join with each other) is flat rather than revolute, which would have made the series more flexible than that of terrestrial relatives.

For the four preserved sacral vertebrae (at the sacrum, between the pelvic bones), the transverse processes of S1 are smaller than those of L8. There is a robust sacroiliac joint

The sacroiliac joint or SI joint (SIJ) is the joint between the sacrum and the ilium bones of the pelvis, which are connected by strong ligaments. In humans, the sacrum supports the spine and is supported in turn by an ilium on each side. The ...

with the hip. For the spinous processes, those of S1–S3 are fused. Metapophyses jut straight up from each lamina near the joint, progressively getting smaller with each vertebra.

Only five of the tail (caudal) vertebrae are preserved: a possible C1 or C2, a possible C3, a possible C4, a possible C7, and a possible C8. The more headward tail vertebrae have thick transverse processes, whereas those of the middle tail vertebrae are longer than broad. The C3 has a narrow spinous process and is mostly columnar, but the tailward side is broader. The C4 is more columnar. The C7 and C8 are columnar and taper off tailward, and the neural canal

In the developing chordate (including vertebrates), the neural tube is the embryonic precursor to the central nervous system, which is made up of the brain and spinal cord. The neural groove gradually deepens as the neural fold become elevated, a ...

where the central nervous system

The central nervous system (CNS) is the part of the nervous system consisting primarily of the brain and spinal cord. The CNS is so named because the brain integrates the received information and coordinates and influences the activity of all par ...

runs through is still present. In life, ''Ambulocetus'' possibly had upwards of 20 tail vertebrae like some mesonychians. If correct, then ''Ambulocetus'' would have had a lot fewer and a lot longer tail vertebrae than modern cetaceans.

Limbs and girdles

radius

In classical geometry, a radius ( : radii) of a circle or sphere is any of the line segments from its center to its perimeter, and in more modern usage, it is also their length. The name comes from the latin ''radius'', meaning ray but also the ...

and ulna

The ulna (''pl''. ulnae or ulnas) is a long bone found in the forearm that stretches from the elbow to the smallest finger, and when in anatomical position, is found on the medial side of the forearm. That is, the ulna is on the same side of t ...

(the forearm bones). The forearm measures in length. The head of the radius

The head of the radius has a cylindrical form, and on its upper surface is a shallow cup or fovea for articulation with the capitulum of the humerus. The circumference of the head is smooth; it is broad medially where it articulates with the radi ...

is somewhat triangular, which probably means the forearm was locked in a semi-pronated

Motion, the process of movement, is described using specific anatomical terms. Motion includes movement of organs, joints, limbs, and specific sections of the body. The terminology used describes this motion according to its direction relativ ...

position (the palms were orientated towards the ground). The olecranon

The olecranon (, ), is a large, thick, curved bony eminence of the ulna, a long bone in the forearm that projects behind the elbow. It forms the most pointed portion of the elbow and is opposite to the cubital fossa or elbow pit. The olecranon ...

, which formed part of the elbow joint, makes up about a third of the ulna's length and is inclined tailwards, which would have allowed the triceps

The triceps, or triceps brachii (Latin for "three-headed muscle of the arm"), is a large muscle on the back of the upper limb of many vertebrates. It consists of 3 parts: the medial, lateral, and long head. It is the muscle principally responsibl ...

to more forcefully flex the elbow. The wrist bones indicate a strong flexor carpi ulnaris muscle

The flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU) is a muscle of the forearm that flexes and adducts at the wrist joint.

Structure Origin

The flexor carpi ulnaris has two heads; a humeral head and ulnar head. The humeral head originates from the medial epicondyle o ...

for wrist flexion. The hand had five widely spaced digits. The first metacarpal

The first metacarpal bone or the metacarpal bone of the thumb is the first bone proximal to the thumb. It is connected to the trapezium of the carpus at the first carpometacarpal joint and to the proximal thumb phalanx at the first metacarpophal ...

(which is in the thumb) is long, the second

The second (symbol: s) is the unit of time in the International System of Units (SI), historically defined as of a day – this factor derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes and finally to 60 seconds ...

, the third

Third or 3rd may refer to:

Numbers

* 3rd, the ordinal form of the cardinal number 3

* , a fraction of one third

* Second#Sexagesimal divisions of calendar time and day, 1⁄60 of a ''second'', or 1⁄3600 of a ''minute''

Places

* 3rd Street (d ...

, the fourth , and the fifth . Like modern beaked whale

Beaked whales (systematic name Ziphiidae) are a family of cetaceans noted as being one of the least known groups of mammals because of their deep-sea habitat and apparent low abundance. Only three or four of the 24 species are reasonably well-k ...

s, the thumb is short and slender.

The ilium of the hip of ''Ambulocetus'', like remingtonocetids, features deep depressions to support the rectus femoris

The rectus femoris muscle is one of the four quadriceps muscles of the human body. The others are the vastus medialis, the vastus intermedius (deep to the rectus femoris), and the vastus lateralis. All four parts of the quadriceps muscle attach to ...

and the gluteal muscles

The gluteal muscles, often called glutes are a group of three muscles which make up the gluteal region commonly known as the buttocks: the gluteus maximus, gluteus medius and gluteus minimus. The three muscles originate from the ilium and sac ...

. Unlike terrestrial mammals and protocetids, the ischium

The ischium () form ...

is expanded dorsolaterally (from left to right, and upwards), which would have increased lever arm

In physics and mechanics, torque is the rotational equivalent of linear force. It is also referred to as the moment of force (also abbreviated to moment). It represents the capability of a force to produce change in the rotational motion of the ...

for thigh and leg retractor muscles when extended, such as while swimming. This would have also increased the surface area of the gemelli muscles

The gemelli muscles are the inferior gemellus muscle

and the superior gemellus muscle, two small accessory fasciculi to the tendon of the internal obturator muscle. The gemelli muscles belong to the lateral rotator group of six muscles of the hip ...

(hip rotators which stabilise the hip) and the tail muscles. The widening of the ischium may have also given ''Ambulocetus'' a more streamlined and hydrodynamic body. ''Ambulocetus'' had a pubic symphysis

The pubic symphysis is a secondary cartilaginous joint between the left and right superior rami of the pubis of the hip bones. It is in front of and below the urinary bladder. In males, the suspensory ligament of the penis attaches to the pubic ...

connecting the two pubic bone

In vertebrates, the pubic region ( la, pubis) is the most forward-facing (ventral and anterior) of the three main regions making up the coxal bone. The left and right pubic regions are each made up of three sections, a superior ramus, inferior ra ...

s at the base of the pelvis together, which indicates the animal could support its own weight on land. The modern cetacean pubis bone lacks this and only functions to anchor abdominal and urogenital muscles.

The leg proportions of ''Ambulocetus'' are similar to otters and seals

Seals may refer to:

* Pinniped, a diverse group of semi-aquatic marine mammals, many of which are commonly called seals, particularly:

** Earless seal, or "true seal"

** Fur seal

* Seal (emblem), a device to impress an emblem, used as a means of a ...

, and American mammalogist Alfred Brazier Howell predicted similar proportions for a transitional cetacean in 1930. The femur measures , a length similar to the presumably cursorial

A cursorial organism is one that is adapted specifically to run. An animal can be considered cursorial if it has the ability to run fast (e.g. cheetah) or if it can keep a constant speed for a long distance (high endurance). "Cursorial" is often u ...

(capable of running) mesonychid ''Pachyaena

''Pachyaena'' (literally, "thick hyena") was a genus of heavily built, relatively short-legged mesonychids, early Cenozoic mammals that evolved before the origin of either modern hoofed animals or carnivores, and combined characteristics similar t ...

''. Archaeocete femora are generally much shorter. The femoral head

The femoral head (femur head or head of the femur) is the highest part of the thigh bone (femur). It is supported by the femoral neck.

Structure

The head is globular and forms rather more than a hemisphere, is directed upward, medialward, and a l ...

is spherical and, at maximum, has a width of , similar to ''Indocetus

''Indocetus'' is a protocetid early whale known from the late early Eocene (Lutetian, ) Harudi Formation (, paleocoordinates ) in Kutch, India.

The holotype of is a partial skull in two pieces with the frontal shield and the right occiput a ...

'' but much larger than mesonychids and ''Rodhocetus''. The trochanteric fossa

In mammals including humans, the medial surface of the greater trochanter has at its base a deep depression bounded posteriorly by the intertrochanteric crest, called the trochanteric fossa. This fossa is the point of insertion of four muscles. Mov ...

, supporting the lateral rotator group

The lateral rotator group is a group of six small muscles of the hip which all externally (laterally) rotate the femur in the hip joint. It consists of the following muscles: piriformis, gemellus superior, obturator internus, gemellus inferior, q ...

at the hip, is quite deep, but other than this, the femur does not seem to have supported particularly strong extensor or flexor muscles. The femoral condyle

The lower extremity of femur (or distal extremity) is the lower end of the femur (thigh bone) in human and other animals, closer to the knee. It is larger than the upper extremity of femur, is somewhat cuboid in form, but its transverse diameter is ...

s of ''Ambulocetus'' are quite long compared to those of other archaeocetes and mesonychids, suggesting the knee was capable of hyperflexion

Motion, the process of movement, is described using specific anatomical terms. Motion includes movement of organs, joints, limbs, and specific sections of the body. The terminology used describes this motion according to its direction relative ...

(bending). The tibia is overall similar to those of mesonychids. The feet are huge, probably longer than the femur. The toes are also relatively long, with the fourth digit measuring in length. The fifth digit is slightly shorter and much less robust than the fourth. The phalanges

The phalanges (singular: ''phalanx'' ) are digital bones in the hands and feet of most vertebrates. In primates, the thumbs and big toes have two phalanges while the other digits have three phalanges. The phalanges are classed as long bones.

...

of the toes are short, and end with a convex hoof

The hoof (plural: hooves) is the tip of a toe of an ungulate mammal, which is covered and strengthened with a thick and horny keratin covering. Artiodactyls are even-toed ungulates, species whose feet have an even number of digits, yet the rumin ...

. Like seals, the phalanges of both the hands and feet are flattened, which may have streamlined them to allow for webbed feet

The webbed foot is a specialized limb with interdigital membranes (webbings) that aids in aquatic locomotion, present in a variety of tetrapod vertebrates. This adaptation is primarily found in semiaquatic species, and has convergently evolved m ...

.

Palaeobiology

Diet

The robustness of the cheek teeth, as well as the cusp arrangement, suggests they were involved in crushing, and the fact that both the premolars and molars were involved in crushing indicates ''Ambulocetus'' required a large area for crushing, such as when biting into large prey items. Similarly, the broad and powerful snout makes it unlikely it was pursuing small, quick prey items (which would have required a narrow snout like dolphins or

The robustness of the cheek teeth, as well as the cusp arrangement, suggests they were involved in crushing, and the fact that both the premolars and molars were involved in crushing indicates ''Ambulocetus'' required a large area for crushing, such as when biting into large prey items. Similarly, the broad and powerful snout makes it unlikely it was pursuing small, quick prey items (which would have required a narrow snout like dolphins or gharial

The gharial (''Gavialis gangeticus''), also known as gavial or fish-eating crocodile, is a crocodilian in the family Gavialidae and among the longest of all living crocodilians. Mature females are long, and males . Adult males have a distinct b ...

s). The snout was also long, which may have precluded the ability to crush bone because it would have had reduced structural integrity at the tip. The anatomy of the cheek teeth resembles those of Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceo ...

marine reptile

Marine reptiles are reptiles which have become secondarily adapted for an aquatic or semiaquatic life in a marine environment.

The earliest marine reptile mesosaurus (not to be confused with mosasaurus), arose in the Permian period during the ...

s which fed on armoured fish, large fish, reptiles, and ammonite

Ammonoids are a group of extinct marine mollusc animals in the subclass Ammonoidea of the class Cephalopoda. These molluscs, commonly referred to as ammonites, are more closely related to living coleoids (i.e., octopuses, squid and cuttlefish) ...

s, and the teeth may have been used to grip onto prey firmly. Therefore, Thewissen suggested ''Ambulocetus'' was most likely an ambush predator, the jaw adapted to handle struggling prey. The unusually deep pterygoids potentially functioned to dissipate force while the prey was struggling.

The eyes of ''Ambulocetus'' were placed on the top of the head, similar to crocodile

Crocodiles (family (biology), family Crocodylidae) or true crocodiles are large semiaquatic reptiles that live throughout the tropics in Africa, Asia, the Americas and Australia. The term crocodile is sometimes used even more loosely to inclu ...

s and other animals that prefer to keep most of their body submerged with the eyes peeking out of the water. The nasal canal has bony walls extending into the throat, much like in crocodiles where they keep the nasal airways open while the animal is killing prey either by drowning it or thrashing it around. Pieces of prey are subsequently torn off by forceful, thrashing head and body motions, the feet anchoring the crocodile in place. Thewissen believed ''Ambulocetus'' used a similar feeding tactic, though ''Ambulocetus'' was probably capable of chewing, unlike crocodiles. ''Ambulocetus'' may have attacked large mammals which approached the water's edge, and semi-aquatic mammals including early (possibly herbivorous) sirenia

The Sirenia (), commonly referred to as sea-cows or sirenians, are an order of fully aquatic, herbivorous mammals that inhabit swamps, rivers, estuaries, marine wetlands, and coastal marine waters. The Sirenia currently comprise two distinct f ...

ns (now manatee

Manatees (family Trichechidae, genus ''Trichechus'') are large, fully aquatic, mostly herbivorous marine mammals sometimes known as sea cows. There are three accepted living species of Trichechidae, representing three of the four living species ...

s and the dugong

The dugong (; ''Dugong dugon'') is a marine mammal. It is one of four living species of the order Sirenia, which also includes three species of manatees. It is the only living representative of the once-diverse family Dugongidae; its closest m ...

) and the probably amphibious anthracobunids. These two seem to have been rather common on the coasts of the Indian subcontinent, which could mean they were regular prey items. Since ''Ambulocetus'' was found in marine deposits (where animals would not come to drink), it is possible it hunted in river delta

A river delta is a landform shaped like a triangle, created by deposition (geology), deposition of sediment that is carried by a river and enters slower-moving or stagnant water. This occurs where a river enters an ocean, sea, estuary, lake, res ...

s which were recorded in the Kuldana Formation. ''Ambulocetus'' probably went after fish and reptiles when given the opportunity, though it may not have had the agility to commonly catch them.

Locomotion

giant otter

The giant otter or giant river otter (''Pteronura brasiliensis'') is a South American carnivorous mammal. It is the longest member of the weasel family, Mustelidae, a globally successful group of predators, reaching up to . Atypical of musteli ...

, and species in the genera ''Lontra

''Lontra'' is a genus of otters from the Americas.

Species

These species were previously included in the genus ''Lutra'', together with the Eurasian otter

The Eurasian otter (''Lutra lutra''), also known as the European otter, Eurasian river ...

'' and ''Lutra

''Lutra'' is a genus of otters, one of seven in the subfamily Lutrinae.

Taxonomy and evolution

The genus includes these species:

Extant species

Extinct species

*†''Lutra affinis''

*†''Lutra bressana ''

*†''Lutra bravardi''

*†''Lut ...

''. Based on the length of the known tail vertebrae, ''Ambulocetus'' may have had an inflexible tail, which would have made the tail an inefficient primary propulsion mechanism due to poorer lever arm (modern cetaceans have relatively short tail vertebrae). ''Ambulocetus'' therefore likely did not have a tail fluke. Nonetheless, drag powered swimmers still have powerful tails for producing lift, and the tails of river otters are 125% the size of the thoracolumbar series. So, using river otters as a model, ''Ambulocetus'' was a pelvic paddler—swimming with alternating beats of the hindlimbs (without engaging the forelimbs)—and also undulated (moved up and down) its tail while swimming. Like the sea otter

The sea otter (''Enhydra lutris'') is a marine mammal native to the coasts of the northern and eastern North Pacific Ocean. Adult sea otters typically weigh between , making them the heaviest members of the weasel family, but among the small ...

, pelvic paddling may have been done at the surface to move at slow or moderate speeds. At higher speeds fully submerged, undulation of the spine would have become more prominent, though the feet still would have acted as the primary propulsion mechanism.

Based on the pelvis and robust forelimbs, Thewissen believed ''Ambulocetus'' was capable of venturing onto land, and was more efficient at doing this than remingtonocetids and protocetids (it is unclear if the latter two were capable of bearing weight on the limbs). ''Ambulocetus'' possibly used a sprawling gait on land, similar to modern sea lion

Sea lions are pinnipeds characterized by external ear flaps, long foreflippers, the ability to walk on all fours, short and thick hair, and a big chest and belly. Together with the fur seals, they make up the family Otariidae, eared seals. ...

s. In 2016, Japanese biologists Konami Ando and Shin‐ichi Fujiwara performed a statistical test of ribcage strength among terrestrial, semi-aquatic, and fully aquatic mammals, and found that ''Ambulocetus'' clustered with fully aquatic mammals, because they assigned a very high rib density on par with fully aquatic sirenians which use their heavy, osteosclerotic ribs as ballast

Ballast is material that is used to provide stability to a vehicle or structure. Ballast, other than cargo, may be placed in a vehicle, often a ship or the gondola of a balloon or airship, to provide stability. A compartment within a boat, ship, ...

. They then concluded ''Ambulocetus'' could not walk on land, but cautioned the study was limited by a lack of information on the exact density of the bone, the location of the centre of mass

In physics, the center of mass of a distribution of mass in space (sometimes referred to as the balance point) is the unique point where the weighted relative position of the distributed mass sums to zero. This is the point to which a force may ...

, and the reliance of false rib

The rib cage, as an enclosure that comprises the ribs, vertebral column and sternum in the thorax of most vertebrates, protects vital organs such as the heart, lungs and great vessels.

The sternum, together known as the thoracic cage, is a semi ...

s for thoracic support.

Hearing

Modern cetaceans have highly specialised ear bones to hear underwater as well as to detect certain frequency ranges. Unlike most other mammals, cetacean ear bones are comparatively thick, and so preserve more reliably in the fossil record. Modern cetaceans have air sinuses surrounding the ear bones (peritympanic sinuses), which acoustically isolate the ear by reflecting sound moving through the head and interrupting both bony and fleshy connections of the ear to the skull. Like later archaeocetes, ''Ambulocetus'' had at least one such sinus between the tympanic bone and the skull base. The evolution of these sinuses also seems to have caused some restructuring of the skull base due to the development of bony walls surrounding the sinuses. The ectotympanic of all cetaceans, including ''Pakicetus'' and ''Ambulocetus'', has a bony growth (involucrum) on the medial lip speculated to aid in the detection of low-frequency sounds. All cetaceans also have a vertical crest ("sigmoid process") right in front of the ear canal, which is speculated to be related to the increasing size of themalleus

The malleus, or hammer, is a hammer-shaped small bone or ossicle of the middle ear. It connects with the incus, and is attached to the inner surface of the eardrum. The word is Latin for 'hammer' or 'mallet'. It transmits the sound vibrations fro ...

bone in the middle ear.

As for the outer ear, terrestrial mammals channel sound in via an ear canal

The ear canal (external acoustic meatus, external auditory meatus, EAM) is a pathway running from the outer ear to the middle ear. The adult human ear canal extends from the pinna to the eardrum and is about in length and in diameter.

Struc ...

, but those of modern cetaceans are either narrowed or completely plugged, the sound being picked up (at least for toothed whales) by a fat pad in the lower jaw running to the ectotympanic bone. The mandibular foramen size can determine the size of the fat pad, and that of ''Ambulocetus'' is larger than that of ''Pakicetus'' and terrestrial mammals, but is smaller than later archaeocetes and toothed whales. Nonetheless, a lot of the change to the external auditory apparatus occurred between ''Pakicetus'' and ''Ambulocetus''. These early archaeocetes may have developed such an external ear to either: better hear underwater; facilitate bone conduction