Alexander of Greece (king) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Alexander ( el, Αλέξανδρος, ''Aléxandros''; 1 August 189325 October 1920) was

Alexander's early life alternated between the

Alexander's early life alternated between the

During World War I, Constantine I followed a formal policy of neutrality, yet he was openly benevolent towards

During World War I, Constantine I followed a formal policy of neutrality, yet he was openly benevolent towards

Alexander swore the oath of loyalty to the

Alexander swore the oath of loyalty to the

On 26 June 1917, the king was forced to name Eleftherios Venizelos as head of the government. Despite promises given by the Entente on Constantine's departure, the previous prime minister, Zaimis, was effectively forced to resign as Venizelos returned to Athens. Alexander immediately opposed his new prime minister's views and, annoyed by the king's rebuffs, Venizelos threatened to remove him and set up a regency council in the name of Alexander's brother Prince Paul, then still a minor. The Entente powers intervened and asked Venizelos to back down, allowing Alexander to retain the crown. Spied on day and night by the prime minister's supporters, the monarch quickly became a prisoner in his own palace, and his orders went ignored.

Alexander had no experience in affairs of state. However, he was determined to make the best of a difficult situation and represent his father as best he could. Adopting an air of cool indifference to the government, he rarely made the effort to read official documents before he rubber-stamped them. His functions were limited, and amounted to visiting the

On 26 June 1917, the king was forced to name Eleftherios Venizelos as head of the government. Despite promises given by the Entente on Constantine's departure, the previous prime minister, Zaimis, was effectively forced to resign as Venizelos returned to Athens. Alexander immediately opposed his new prime minister's views and, annoyed by the king's rebuffs, Venizelos threatened to remove him and set up a regency council in the name of Alexander's brother Prince Paul, then still a minor. The Entente powers intervened and asked Venizelos to back down, allowing Alexander to retain the crown. Spied on day and night by the prime minister's supporters, the monarch quickly became a prisoner in his own palace, and his orders went ignored.

Alexander had no experience in affairs of state. However, he was determined to make the best of a difficult situation and represent his father as best he could. Adopting an air of cool indifference to the government, he rarely made the effort to read official documents before he rubber-stamped them. His functions were limited, and amounted to visiting the

By the end of World War I, Greece had grown beyond its 1914 borders, and the treaties of Neuilly (1919) and

By the end of World War I, Greece had grown beyond its 1914 borders, and the treaties of Neuilly (1919) and

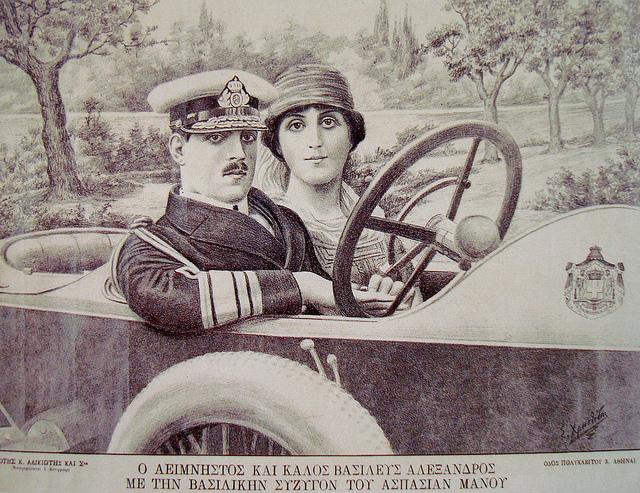

With the help of Aspasia's brother-in-law, Christo Zalocostas, and after three unsuccessful attempts, the couple eventually married in secret before a royal chaplain,

With the help of Aspasia's brother-in-law, Christo Zalocostas, and after three unsuccessful attempts, the couple eventually married in secret before a royal chaplain,

On 2 October 1920, Alexander was injured while walking through the grounds of the Tatoi estate. A domestic

On 2 October 1920, Alexander was injured while walking through the grounds of the Tatoi estate. A domestic

Alexander's death raised questions about the succession to the throne as well as the nature of the Greek regime. As the king had contracted an unequal marriage, his descendants were not in the line of succession. The

Alexander's death raised questions about the succession to the throne as well as the nature of the Greek regime. As the king had contracted an unequal marriage, his descendants were not in the line of succession. The

Film of King Alexander's funeral

British Pathé {{DEFAULTSORT:Alexander of Greece 1893 births 1920 deaths 19th-century Greek people 20th-century Greek monarchs Kings of Greece Greek princes Danish princes House of Glücksburg (Greece) Eastern Orthodox monarchs Grand Croix of the Légion d'honneur Honorary Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Greek people of World War I Greek generals Eastern Orthodox Christians from Greece Politicians from Athens 1920 in Greece Deaths due to animal attacks Deaths from sepsis Burials at Tatoi Palace Royal Cemetery Sons of kings

King of Greece

The Kingdom of Greece was ruled by the House of Wittelsbach between 1832 and 1862 and by the House of Glücksburg from 1863 to 1924, temporarily abolished during the Second Hellenic Republic, and from 1935 to 1973, when it was once more abolishe ...

from 11 June 1917 until his death three years later, at the age of 27, from the effects of a monkey bite.

The second son of King Constantine I

Constantine I ( el, Κωνσταντίνος Αʹ, ''Konstantínos I''; – 11 January 1923) was King of Greece from 18 March 1913 to 11 June 1917 and from 19 December 1920 to 27 September 1922. He was commander-in-chief of the Hellenic Army ...

, Alexander was born in the summer palace of Tatoi

Tatoi ( el, Τατόι, ) was the summer palace and estate of the former Greek royal family. The area is a densely wooded southeast-facing slope of Mount Parnitha, and its ancient and current official name is Dekeleia. It is located from t ...

on the outskirts of Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

. He succeeded his father in 1917, during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, after the Entente Powers

The Triple Entente (from French '' entente'' meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as well a ...

and the followers of Eleftherios Venizelos

Eleftherios Kyriakou Venizelos ( el, Ελευθέριος Κυριάκου Βενιζέλος, translit=Elefthérios Kyriákou Venizélos, ; – 18 March 1936) was a Greek statesman and a prominent leader of the Greek national liberation movem ...

pushed Constantine I, and his eldest son Crown Prince George, into exile. Having no real political experience, the new king was stripped of his powers by the Venizelists and effectively imprisoned in his own palace. Venizelos, as prime minister, was the effective ruler with the support of the Entente. Though reduced to the status of a puppet king

A puppet monarch is a majority figurehead who is installed or patronized by an imperial power to provide the appearance of local authority but to allow political and economic control to remain among the dominating nation.

A figurehead monarch ...

, Alexander supported Greek troops during their war against the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

and Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

. Under his reign, the territorial extent of Greece considerably increased, following the victory of the Entente and their Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

in the First World War and the early stages of the Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922.

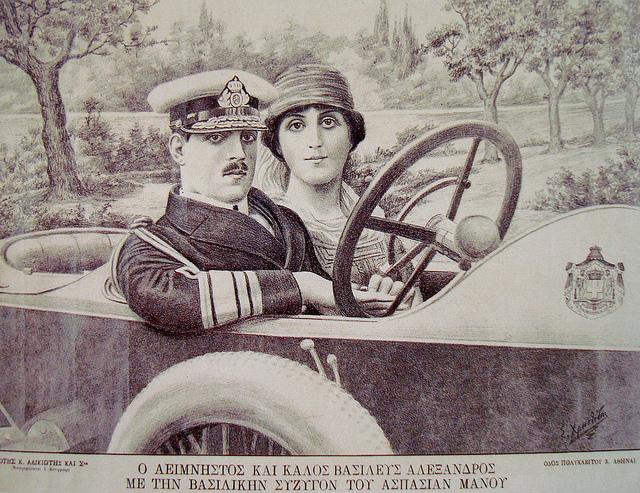

Alexander controversially married the commoner Aspasia Manos

Princess Aspasia of Greece and Denmark (born Aspasia Manos el, Ασπασία Μάνου; 4 September 1896 – 7 August 1972) was a Greek aristocrat who became the wife of Alexander I, King of Greece. Due to the controversy over her marriage, ...

in 1919, provoking a major scandal that forced the couple to leave Greece for several months. Soon after returning to Greece with his wife, Alexander was bitten by a domestic Barbary macaque

The Barbary macaque (''Macaca sylvanus''), also known as Barbary ape, is a macaque species native to the Atlas Mountains of Algeria, Libya, Tunisia and Morocco, along with a small introduced population in Gibraltar.

It is the type species of the ...

and died of sepsis

Sepsis, formerly known as septicemia (septicaemia in British English) or blood poisoning, is a life-threatening condition that arises when the body's response to infection causes injury to its own tissues and organs. This initial stage is follo ...

. The sudden death of the sovereign led to questions over the monarchy's survival and contributed to the fall of the Venizelist regime. After a general election

A general election is a political voting election where generally all or most members of a given political body are chosen. These are usually held for a nation, state, or territory's primary legislative body, and are different from by-elections ( ...

and a referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

, Constantine I was restored to the throne.

Early life

Alexander was born atTatoi Palace

Tatoi ( el, Τατόι, ) was the summer palace and estate of the former Greek royal family. The area is a densely wooded southeast-facing slope of Mount Parnitha, and its ancient and current official name is Dekeleia. It is located from t ...

on 1 August 1893 (20 July in the Julian calendar

The Julian calendar, proposed by Roman consul Julius Caesar in 46 BC, was a reform of the Roman calendar. It took effect on , by edict. It was designed with the aid of Greek mathematicians and astronomers such as Sosigenes of Alexandr ...

), the second son of Crown Prince Constantine of Greece of the House of Glücksburg

The House of Glücksburg (also spelled ''Glücksborg'' or ''Lyksborg''), shortened from House of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, is a collateral branch of the German House of Oldenburg, members of which have reigned at various times ...

and his wife Princess Sophia of Prussia

Sophia of Prussia (Sophie Dorothea Ulrike Alice, el, Σοφία; 14 June 1870 – 13 January 1932) was Queen consort of the Hellenes from 1913–1917, and also from 1920–1922.

A member of the House of Hohenzollern and child of Frederick III, ...

. He was related to royalty throughout Europe. His father was the eldest son and heir apparent of King George I of Greece

George I (Greek language, Greek: Γεώργιος Α΄, ''Geórgios I''; 24 December 1845 – 18 March 1913) was List of kings of Greece, King of Greece from 30 March 1863 until his assassination in 1913.

Originally a Danish prince, he was bor ...

by his wife Grand Duchess Olga Constantinovna of Russia

Olga Constantinovna of Russia ( el, Όλγα; 18 June 1926) was queen consort of Greece as the wife of King George I. She was briefly the regent of Greece in 1920.

A member of the Romanov dynasty, she was the oldest daughter of Grand Duke Co ...

; his mother was the daughter of Emperor Frederick III of Germany and his wife Victoria, Princess Royal of the United Kingdom.Montgomery-Massingberd, p. 327. Constantine was a grandson of King Christian IX of Denmark

Christian IX (8 April 181829 January 1906) was King of Denmark from 1863 until his death in 1906. From 1863 to 1864, he was concurrently Duke of Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenburg.

A younger son of Frederick William, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein- ...

and a cousin of both King George V of the United Kingdom

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Que ...

and Emperor Nicholas II of Russia

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov; spelled in pre-revolutionary script. ( 186817 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,. was the last Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Pola ...

. Sophia was the sister of Emperor Wilhelm II of Germany, and was also a cousin of King George V through her grandmother, Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

.

Alexander's early life alternated between the

Alexander's early life alternated between the Royal Palace

This is a list of royal palaces, sorted by continent.

Africa

* Abdin Palace, Cairo

* Al-Gawhara Palace, Cairo

* Koubbeh Palace, Cairo

* Tahra Palace, Cairo

* Menelik Palace

* Jubilee Palace

* Guenete Leul Palace

* Imperial Palace- Massa ...

in Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

, and Tatoi Palace in the city's suburbs. With his parents he undertook several trips abroad and regularly visited Schloss Friedrichshof

Schlosshotel Kronberg (Castle Hotel Kronberg) in Kronberg im Taunus, Hesse, near Frankfurt am Main, was built between 1889 and 1893 for the dowager German Empress Victoria and originally named Schloss Friedrichshof in honour of her late hus ...

, the home of his maternal grandmother, who had a particular affection for her Greek grandson.Van der Kiste, p. 62.

Though he was very close to his younger sister, Princess Helen, Alexander was less warm towards his elder brother George

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd Presiden ...

, with whom he had little in common.Sáinz de Medrano, p. 174. While his elder brother was a serious and thoughtful child, Alexander was mischievous and extroverted; he smoked cigarettes made from blotting paper, set fire to the games room in the palace, and recklessly lost control of a toy cart in which he and his younger brother Paul

Paul may refer to:

*Paul (given name), a given name (includes a list of people with that name)

*Paul (surname), a list of people

People

Christianity

*Paul the Apostle (AD c.5–c.64/65), also known as Saul of Tarsus or Saint Paul, early Chris ...

were rolling down a hill, tipping his toddler brother a distance of six feet into brambles.

Military career

As his father's second son, Alexander was third in line to the throne, after his father and elder brother, George. His education was expensive and carefully planned, but while George spent part of his military training in Germany, Alexander was educated in Greece. He joined the prestigiousHellenic Military Academy

The Hellenic Army Academy ( el, Στρατιωτική Σχολή Ευελπίδων), commonly known as the Evelpidon, is a military academy. It is the Officer cadet school of the Greek Army and the oldest third-level educational institution in G ...

, where several of his uncles had previously studied and where he made himself known more for his mechanical skills than for his intellectual capacity. He was passionate about cars and motors, and was one of the first Greeks to acquire an automobile.Van der Kiste, p. 113.

He distinguished himself in combat during the Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars refers to a series of two conflicts that took place in the Balkan States in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan States of Greece, Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria declared war upon the Ottoman Empire and defe ...

of 1912–13. As a young officer, he was stationed, along with his elder brother, in the field staff of his father; and he accompanied the latter at the head of the Army of Thessaly during the capture of Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area, and the capi ...

in 1912. King George I was assassinated in Thessaloniki soon afterwards on 18 March 1913, and Alexander's father ascended the throne as Constantine I.

Courtship of Aspasia Manos

In 1915, at a party held in Athens by court marshal TheodoreYpsilantis

The House of Ypsilantis ( el, Υψηλάντης; ro, Ipsilanti) was a Greek Phanariote family which grew into prominence and power in Constantinople during the last centuries of Ottoman Empire and gave several short-reign '' hospodars'' to the ...

, Alexander became re-acquainted with one of his childhood friends, Aspasia Manos

Princess Aspasia of Greece and Denmark (born Aspasia Manos el, Ασπασία Μάνου; 4 September 1896 – 7 August 1972) was a Greek aristocrat who became the wife of Alexander I, King of Greece. Due to the controversy over her marriage, ...

. She had just returned from education in France and Switzerland, and was reckoned as very beautiful by her acquaintances.Sáinz de Medrano, p. 176. She was the daughter of Constantine's Master of the Horse

Master of the Horse is an official position in several European nations. It was more common when most countries in Europe were monarchies, and is of varying prominence today.

(Ancient Rome)

The original Master of the Horse ( la, Magister Equitu ...

,Van der Kiste, p. 117. Colonel Petros Manos, and his wife Maria Argyropoulos. The 21-year-old Alexander was smitten, and was so determined to seduce her that he followed her to the island of Spetses

Spetses ( el, Σπέτσες, grc, Πιτυούσσα "Pityussa", Arvanitika: Πετσε̱) is an upscale affluent island in Attica, Greece. It is included as one of the Saronic Islands. Until 1948, it was part of the old prefecture of Argolis ...

where she holidayed that year. Initially, Aspasia was resistant to his charm; although considered very handsome by his contemporaries, Alexander had a reputation as a ladies' man from numerous past liaisons. Despite this, he finally won her over, and the couple were engaged in secret. However, for King Constantine I, Queen Sophia and much of European society of the time, it was inconceivable for a royal prince to marry someone of a different social rank.Sáinz de Medrano, p. 177.

World War I

During World War I, Constantine I followed a formal policy of neutrality, yet he was openly benevolent towards

During World War I, Constantine I followed a formal policy of neutrality, yet he was openly benevolent towards Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, which was fighting alongside Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

and the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

against the Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French '' entente'' meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as well a ...

of Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

. Constantine was the brother-in-law of Kaiser Wilhelm II, and had also become something of a Germanophile

A Germanophile, Teutonophile, or Teutophile is a person who is fond of German culture, German people and Germany in general, or who exhibits German patriotism in spite of not being either an ethnic German or a German citizen. The love of the ''Ge ...

following his military training in Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

. His pro-German attitude provoked a split between the monarch and the prime minister, Eleftherios Venizelos

Eleftherios Kyriakou Venizelos ( el, Ελευθέριος Κυριάκου Βενιζέλος, translit=Elefthérios Kyriákou Venizélos, ; – 18 March 1936) was a Greek statesman and a prominent leader of the Greek national liberation movem ...

, who wanted to support the Entente in the hope of expanding Greek territory to incorporate the Greek minorities in the Ottoman Empire and the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

. Protected by the countries of the Entente, particularly France, in 1916 Venizelos formed a parallel government to that of the king.

Parts of Greece were occupied by the Allied Entente forces, but Constantine I refused to modify his policy and faced increasingly open opposition from the Entente and the Venizelists. In July 1916, an arson attack ravaged Tatoi Palace and the royal family barely escaped the flames; Alexander was not injured but his mother narrowly saved Princess Katherine by carrying her through the woods for more than two kilometers. Among the palace personnel and firefighters who arrived to deal with the blaze, sixteen people were killed.

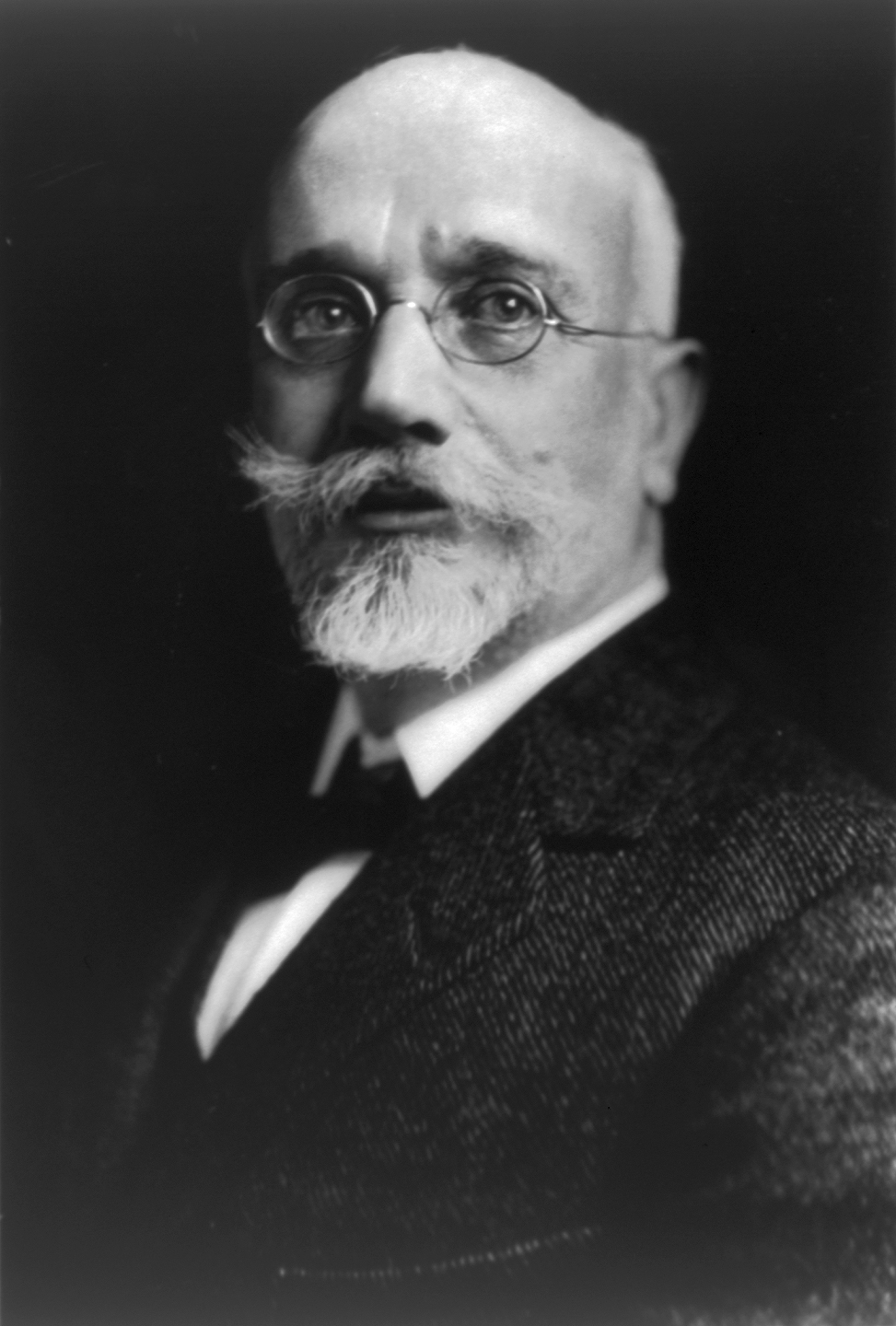

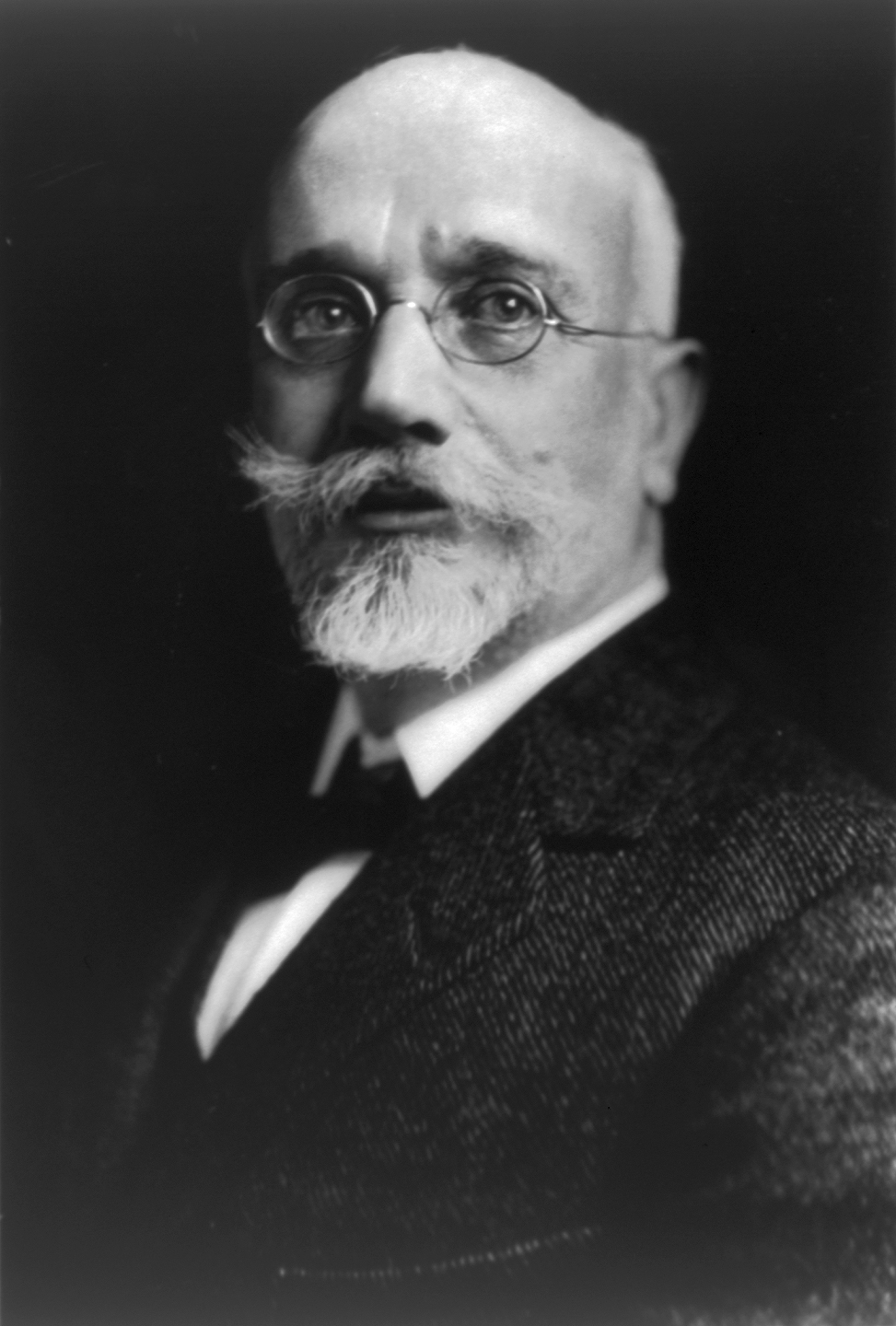

Finally on 10 June 1917, Charles Jonnart

Charles Célestin Auguste Jonnart (27 December 1857 – 30 December 1927) was a French politician.

Early years

Born into a bourgeois family in Fléchin, Pas-de-Calais, Charles Jonnart was educated at Saint-Omer, then in Paris. Interested in th ...

, the Entente's High Commissioner in Greece, ordered King Constantine to give up his power. On the threat of Entente forces landing in Piraeus

Piraeus ( ; el, Πειραιάς ; grc, Πειραιεύς ) is a port city within the Athens urban area ("Greater Athens"), in the Attica region of Greece. It is located southwest of Athens' city centre, along the east coast of the Saronic ...

, the king conceded and agreed to go into self-exile, though without officially abdicating his crown. The Allies, while determined to be rid of Constantine, did not wish to create a Greek republic, and sought to replace the king with another member of the royal family. Crown Prince George, who was the natural heir, was ruled out by the Allies because they thought him too pro-German, like his father.Van der Kiste, p. 107. Instead, they considered installing Constantine's brother (and Alexander's uncle), Prince George, but he had tired of public life during his difficult tenure as High Commissioner of Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, and ...

between 1901 and 1905; above all, he sought to remain loyal to his brother, and categorically refused to take the throne. As a result, Constantine's second son, Prince Alexander, was chosen to become the new monarch.

Reign

Accession

The dismissal of Constantine was not unanimously supported by the Entente powers; while France and Britain did nothing to stop Jonnart's actions, theRussian provisional government

The Russian Provisional Government ( rus, Временное правительство России, Vremennoye pravitel'stvo Rossii) was a provisional government of the Russian Republic, announced two days before and established immediately ...

officially protested to Paris. Petrograd

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

demanded that Alexander should not receive the title of king but only that of regent so as to preserve the rights of the deposed sovereign and the Crown Prince. Russia's protests were brushed aside, and Alexander ascended the Greek throne.

Alexander swore the oath of loyalty to the

Alexander swore the oath of loyalty to the Greek constitution

The Constitution of Greece ( el, Σύνταγμα της Ελλάδας, Syntagma tis Elladas) was created by the Fifth Revisionary Parliament of the Hellenes in 1974, after the fall of the Greek military junta and the start of the Third Hellen ...

on the afternoon of 11 June 1917 in the ballroom of the Royal Palace. Apart from the Archbishop of Athens

The Archbishopric of Athens ( el, Ιερά Αρχιεπισκοπή Αθηνών) is a Greek Orthodox archiepiscopal see based in the city of Athens, Greece. It is the senior see of Greece, and the seat of the autocephalous Church of Greece. Its ...

, Theocletus I, who administered the oath, only King Constantine I, Crown Prince George and the king's prime minister, Alexandros Zaimis

Alexandros Zaimis ( el, Αλέξανδρος Ζαΐμης; 9 November 1855 – 15 September 1936) was a Greek politician who served as Greece's Prime Minister, Minister of the Interior, Minister of Justice, and High Commissioner of Crete. He serve ...

, attended.Van der Kiste, pp. 107–108. There were no festivities. The 23-year-old Alexander had a broken voice and tears in his eyes as he made the solemn declaration. He knew that the Entente and the Venizelists would hold real power and that neither his father nor his brother had renounced their claims to the throne. Constantine had informed his son that he should consider himself a regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

, rather than a true monarch.

In the evening, after the ceremony, the royal family decided to leave their palace in Athens for Tatoi

Tatoi ( el, Τατόι, ) was the summer palace and estate of the former Greek royal family. The area is a densely wooded southeast-facing slope of Mount Parnitha, and its ancient and current official name is Dekeleia. It is located from t ...

, but city residents opposed the exile of their sovereign and crowds formed outside the palace to prevent Constantine and his family from leaving. On 12 June, the former king and his family escaped undetected from their residence by feigning departure from one gate while exiting through another. At Tatoi, Constantine again impressed upon Alexander that he held the crown in trust only. It was the last time that Alexander would be in direct contact with his family. The next day, Constantine, Sophia and all of their children except Alexander arrived at the small port of Oropos

Oropos ( el, Ωρωπός) is a small town and a municipality in East Attica, Greece.

The village of Skala Oropou, within the bounds of the municipality, was the site an important ancient Greek city, Oropus, and the famous nearby sanctuary of Am ...

and set off into exile.

Puppet king

With his parents and siblings in exile, Alexander found himself isolated. The royals remained unpopular with the Venizelists, and Entente representatives advised the king's aunts and uncles, particularlyPrince Nicholas

Nicholas Teo () is a Malaysian Chinese singer under Good Tengz Entertainment Sdn Bhd. (Malaysia)

Career

Pre debut

Before returning to Malaysia, Nicholas was studying in Taiwan, where he won the Best Singer in a competition among all the Tai ...

, to leave. Eventually, they all followed Constantine into exile. Royal household staff were gradually replaced by enemies of the former king, and Alexander's allies were either imprisoned or distanced from him. Portraits of the royal family were removed from public buildings, and Alexander's new ministers openly called him the "son of a traitor".Van der Kiste, p. 112.

On 26 June 1917, the king was forced to name Eleftherios Venizelos as head of the government. Despite promises given by the Entente on Constantine's departure, the previous prime minister, Zaimis, was effectively forced to resign as Venizelos returned to Athens. Alexander immediately opposed his new prime minister's views and, annoyed by the king's rebuffs, Venizelos threatened to remove him and set up a regency council in the name of Alexander's brother Prince Paul, then still a minor. The Entente powers intervened and asked Venizelos to back down, allowing Alexander to retain the crown. Spied on day and night by the prime minister's supporters, the monarch quickly became a prisoner in his own palace, and his orders went ignored.

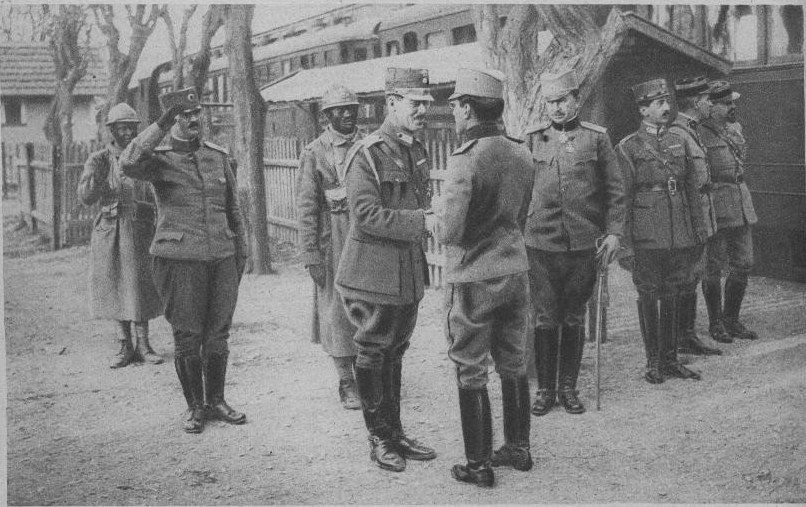

Alexander had no experience in affairs of state. However, he was determined to make the best of a difficult situation and represent his father as best he could. Adopting an air of cool indifference to the government, he rarely made the effort to read official documents before he rubber-stamped them. His functions were limited, and amounted to visiting the

On 26 June 1917, the king was forced to name Eleftherios Venizelos as head of the government. Despite promises given by the Entente on Constantine's departure, the previous prime minister, Zaimis, was effectively forced to resign as Venizelos returned to Athens. Alexander immediately opposed his new prime minister's views and, annoyed by the king's rebuffs, Venizelos threatened to remove him and set up a regency council in the name of Alexander's brother Prince Paul, then still a minor. The Entente powers intervened and asked Venizelos to back down, allowing Alexander to retain the crown. Spied on day and night by the prime minister's supporters, the monarch quickly became a prisoner in his own palace, and his orders went ignored.

Alexander had no experience in affairs of state. However, he was determined to make the best of a difficult situation and represent his father as best he could. Adopting an air of cool indifference to the government, he rarely made the effort to read official documents before he rubber-stamped them. His functions were limited, and amounted to visiting the Macedonian front

The Macedonian front, also known as the Salonica front (after Thessaloniki), was a military theatre of World War I formed as a result of an attempt by the Allied Powers to aid Serbia, in the autumn of 1915, against the combined attack of German ...

to support the morale of the Greek and Allied troops. Since Venizelos's return to power, Athens was at war with the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

, and Greek soldiers battled those of Bulgaria in the north.Van der Kiste, p. 119.

Greek expansion

By the end of World War I, Greece had grown beyond its 1914 borders, and the treaties of Neuilly (1919) and

By the end of World War I, Greece had grown beyond its 1914 borders, and the treaties of Neuilly (1919) and Sèvres

Sèvres (, ) is a commune in the southwestern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located from the centre of Paris, in the Hauts-de-Seine department, Île-de-France region. The commune, which had a population of 23,251 as of 2018, is known for i ...

(1920) confirmed the Greek territorial conquests. The majority of Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to t ...

(previously split between Bulgaria and Turkey) and several Aegean Islands (such as Imbros

Imbros or İmroz Adası, officially Gökçeada (lit. ''Heavenly Island'') since 29 July 1970,Alexis Alexandris, "The Identity Issue of The Minorities in Greece And Turkey", in Hirschon, Renée (ed.), ''Crossing the Aegean: An Appraisal of the 1 ...

and Tenedos

Tenedos (, ''Tenedhos'', ), or Bozcaada in Turkish language, Turkish, is an island of Turkey in the northeastern part of the Aegean Sea. Administratively, the island constitutes the Bozcaada, Çanakkale, Bozcaada district of Çanakkale Provinc ...

) became part of Greece, and the region of Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

, in Ionia

Ionia () was an ancient region on the western coast of Anatolia, to the south of present-day Izmir. It consisted of the northernmost territories of the Ionian League of Greek settlements. Never a unified state, it was named after the Ionian ...

, was placed under Greek mandate

Mandate most often refers to:

* League of Nations mandates, quasi-colonial territories established under Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations, 28 June 1919

* Mandate (politics), the power granted by an electorate

Mandate may also ...

. Alexander's kingdom increased in size by around a third. In Paris, Venizelos took part in the peace negotiations

A peace treaty is an agreement between two or more hostile parties, usually countries or governments, which formally ends a state of war between the parties. It is different from an armistice, which is an agreement to stop hostilities; a surre ...

with the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria. Upon his return to Greece in August 1920, Venizelos received a laurel crown from the king for his work in support of panhellenism

Greek nationalism (or Hellenic nationalism) refers to the nationalism of Greeks and Greek culture.. As an ideology, Greek nationalism originated and evolved in pre-modern times. It became a major political movement beginning in the 18th century, ...

.

Despite their territorial gains following the Paris Peace Conference, the Greeks still hoped to achieve the ''Megali Idea

The Megali Idea ( el, Μεγάλη Ιδέα, Megáli Idéa, Great Idea) is a nationalist and irredentist concept that expresses the goal of reviving the Byzantine Empire, by establishing a Greek state, which would include the large Greek popul ...

'' and annex Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

and larger areas of Ottoman Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

; they invaded Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

beyond Smyrna and sought to take Ankara

Ankara ( , ; ), historically known as Ancyra and Angora, is the capital of Turkey. Located in the central part of Anatolia, the city has a population of 5.1 million in its urban center and over 5.7 million in Ankara Province, maki ...

, with the aim of destroying the Turkish resistance led by Mustafa Kemal

Mustafa ( ar, مصطفى

, Muṣṭafā) is one of the names of Prophet Muhammad, and the name means "chosen, selected, appointed, preferred", used as an Arabic given name and surname. Mustafa is a common name in the Muslim world.

Given name Mo ...

(later known as Atatürk). Thus began the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922)

The Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922, ota, گرب جابهاسی, Garb Cebhesi) in Turkey, and the Asia Minor Campaign ( el, Μικρασιατική Εκστρατεία, Mikrasiatikí Ekstrateía) or the Asia Minor Catastrophe ( el, Μικ ...

. Although Alexander's reign saw success after success for the Greek armies, it was eventually Atatürk's revolutionary forces that obtained victory in 1922, negating the gains made under Alexander.

Marriage

Controversy

On 12 June 1917, the day after his accession, Alexander revealed his liaison with Aspasia Manos to his father and asked for his permission to marry her. Constantine was reluctant to let his son marry a non-royal, and demanded that Alexander wait until the end of the war before considering the engagement, to which Alexander agreed. In the intervening months, Alexander increasingly resented his separation from his family. His regular letters to his parents were intercepted by the government and confiscated. Alexander's only source of comfort was Aspasia, and he decided to marry her despite his father's request. The ruling dynasty of Greece (theHouse of Glücksburg

The House of Glücksburg (also spelled ''Glücksborg'' or ''Lyksborg''), shortened from House of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, is a collateral branch of the German House of Oldenburg, members of which have reigned at various times ...

) was of German-Danish origin, and Constantine and Sophia were seen as far too German by the Venizelists, but even though the marriage of the king to a Greek presented an opportunity to Hellenize the royal family, and counter criticisms that it was a foreign institution, both Venizelists and Constantinists opposed the match. The Venizelists feared it would give Alexander a means to communicate with his exiled family through Colonel Manos and both sides of the political divide were unhappy at the king marrying a commoner.Llewellyn Smith, p. 136. Although Venizelos was a friend of Petros Manos, the prime minister warned the king that marrying her would be unpopular in the eyes of the people.Van der Kiste, p. 118.

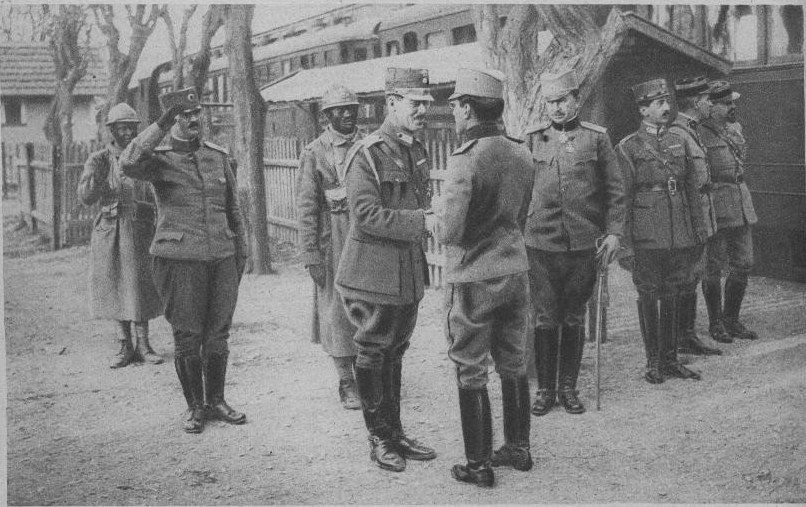

When Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn

Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn (Arthur William Patrick Albert; 1 May 185016 January 1942), was the seventh child and third son of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom and Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. He served as Gov ...

, visited Athens in March 1918, to confer the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I of Great Britain, George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate medieval ceremony for appointing a knight, which involved Bathing#Medieval ...

upon the king, Alexander feared that a marriage between him and Princess Mary of the United Kingdom would be discussed as part of an attempt to consolidate the relationship between Greece and Britain. To Alexander's relief, Arthur asked to meet Aspasia, and declared that, if he were younger, he would have sought to marry her himself. For the foreign powers, and particularly the British ambassador, the marriage was seen as positive. The British authorities feared that Alexander would abdicate in order to marry Aspasia if the wedding was blocked, and they wanted to avoid Greece becoming a republic in case it led to instability or an increase in French influence at their expense.

Alexander's parents were not so happy about the match. Sophia disapproved of her son marrying a commoner, while Constantine wanted a delay but was prepared to be his son's best man if Alexander would be patient. Alexander visited Paris at the end of 1918, raising hopes among his family that they would be able to contact him once he was outside Greece. When Queen Sophia attempted to telephone her son in his Parisian hotel, a minister intercepted the call and informed her that "His Majesty is sorry, but he cannot respond to the telephone". He was not even informed that she had called.

Public scandal

With the help of Aspasia's brother-in-law, Christo Zalocostas, and after three unsuccessful attempts, the couple eventually married in secret before a royal chaplain,

With the help of Aspasia's brother-in-law, Christo Zalocostas, and after three unsuccessful attempts, the couple eventually married in secret before a royal chaplain, Archimandrite

The title archimandrite ( gr, ἀρχιμανδρίτης, archimandritēs), used in Eastern Christianity, originally referred to a superior abbot (''hegumenos'', gr, ἡγούμενος, present participle of the verb meaning "to lead") who ...

Zacharistas, on the evening of 17 November 1919. After the ceremony, the archimandrite was sworn to silence but soon broke his promise by confessing to the Archbishop of Athens, Meletios Metaxakis. According to the Greek constitution, members of the royal family had to obtain permission to marry from both the sovereign and the head of the Greek Orthodox Church

The term Greek Orthodox Church (Greek: Ἑλληνορθόδοξη Ἐκκλησία, ''Ellinorthódoxi Ekklisía'', ) has two meanings. The broader meaning designates "the entire body of Orthodox (Chalcedonian) Christianity, sometimes also call ...

. By marrying Aspasia without the permission of the Archbishop, Alexander caused a major scandal.

Despite his disapproval of the union, Venizelos allowed Aspasia and her mother to move into the Royal Palace on condition that the marriage remain secret. The information leaked, however, and to escape public opprobrium Aspasia was forced to leave Greece. She fled to Rome, and then to Paris, where Alexander was allowed to join her, six months later, on condition that they did not attend official functions together. On their Parisian honeymoon, while motoring near Fontainebleau

Fontainebleau (; ) is a commune in the metropolitan area of Paris, France. It is located south-southeast of the centre of Paris. Fontainebleau is a sub-prefecture of the Seine-et-Marne department, and it is the seat of the ''arrondissement ...

, the couple witnessed a serious car crash in which Count de Kergariou's chauffeur lost control of his master's vehicle. Alexander avoided the count's car, which swerved and hit a tree. The king drove the injured to hospital in his own car, while Aspasia, who had trained as a nurse during World War I, rendered first aid. The count was seriously injured and died shortly afterward, after having both legs amputated.

The government allowed the couple to return to Greece in mid-1920. Although their marriage was legalized, Aspasia was not recognized as queen, but was instead known as "Madame Manos". At first, she stayed at her sister's house in the Greek capital before transferring to Tatoi, and it was during this period that she became pregnant with Alexander's child.

Alexander visited the newly acquired territories of West Thrace

Western Thrace or West Thrace ( el, �υτικήΘράκη, '' ytikíThráki'' ; tr, Batı Trakya; bg, Западна/Беломорска Тракия, ''Zapadna/Belomorska Trakiya''), also known as Greek Thrace, is a geographic and historica ...

, and on 8 July 1920 the new name for the region's main town—Alexandroupoli

Alexandroupolis ( el, Αλεξανδρούπολη, ), Alexandroupoli, or Alexandrople is a city in Greece and the capital of the Evros regional unit. It is the largest city in Western Thrace and the region of Eastern Macedonia and Thrace. It h ...

(meaning "city of Alexander" in Greek)—was announced in the king's presence. The city's previous name of Dedeagatch was considered too Turkish. On 7 September, Venizelos, counting on a surge of support in the wake of the signing of the Treaty of Sèvres and the expansion of Greek territory, announced a general election for early November.

Death

On 2 October 1920, Alexander was injured while walking through the grounds of the Tatoi estate. A domestic

On 2 October 1920, Alexander was injured while walking through the grounds of the Tatoi estate. A domestic Barbary macaque

The Barbary macaque (''Macaca sylvanus''), also known as Barbary ape, is a macaque species native to the Atlas Mountains of Algeria, Libya, Tunisia and Morocco, along with a small introduced population in Gibraltar.

It is the type species of the ...

belonging to the steward of the palace's grapevines attacked or was attacked by the king's German Shepherd Dog

The German Shepherd or Alsatian is a German breed of working dog of medium to large size. The breed was developed by Max von Stephanitz using various traditional German herding dogs from 1899.

It was originally bred as a herding dog, for he ...

, Fritz, and Alexander attempted to separate the two animals. As he did so, another monkey attacked Alexander and bit him deeply on the leg and torso. Eventually servants arrived and chased away the monkeys, and the king's wounds were promptly cleaned and dressed but not cauterize

Cauterization (or cauterisation, or cautery) is a medical practice or technique of burning a part of a body to remove or close off a part of it. It destroys some tissue in an attempt to mitigate bleeding and damage, remove an undesired growth, o ...

d. He did not consider the incident serious and asked that it not be publicized.

That evening, his wounds became infected; he suffered a strong fever and sepsis

Sepsis, formerly known as septicemia (septicaemia in British English) or blood poisoning, is a life-threatening condition that arises when the body's response to infection causes injury to its own tissues and organs. This initial stage is follo ...

set in. His doctors considered amputating his leg, but none wished to take responsibility for so drastic an act. On 19 October, he became delirious and called out for his mother, but the Greek government refused to allow her to re-enter the country from exile in Switzerland, despite her own protestations. Finally, the queen dowager

A queen dowager or dowager queen (compare: princess dowager or dowager princess) is a title or status generally held by the widow of a king. In the case of the widow of an emperor, the title of empress dowager is used. Its full meaning is clear ...

, Olga, George I's widow and Alexander's grandmother, was allowed to return alone to Athens to tend to the king. She was delayed by rough waters, however, and by the time she arrived, Alexander had already died of sepsis

Sepsis, formerly known as septicemia (septicaemia in British English) or blood poisoning, is a life-threatening condition that arises when the body's response to infection causes injury to its own tissues and organs. This initial stage is follo ...

twelve hours previously at a little after 4 p.m. on 25 October 1920. The other members of the royal family received the news by telegram that night.

Two days later, Alexander's body was conveyed to Athens Cathedral, where it lay in state until his funeral on 29 October. Once again, the royal family were refused permission to return to Greece, and Queen Olga was the only member who attended. Foreign powers were represented by the Prince Regent of Serbia with his sister Princess Helen wife of John Constantinovich of Russia, the Crown Prince of Sweden

This page is a list of heirs to the Swedish throne. The list includes all individuals who were considered to inherit the throne of the Kingdom of Sweden, either as heir apparent or as heir presumptive, since the accession of the House of Holstei ...

with his uncle Prince Eugene, Duke of Nericia, and Rear-Admirals Sir George Hope of Britain and Dumesnil of France, as well as members of the Athens diplomatic corps.

After the cathedral service, Alexander's body was interred on the grounds of the royal estate at Tatoi.Van der Kiste, p. 125. The Greek royal family never regarded Alexander's reign as fully legitimate. In the royal cemetery, while other monarchs are given the inscription "King of the Hellenes, Prince of Denmark", Alexander's reads "Alexander, son of the King of the Hellenes, Prince of Denmark. He ruled in the place of his father from 14 June 1917 to 25 October 1920." According to Alexander's favorite sister, Queen Helen of Romania, this feeling of illegitimacy was also shared by Alexander himself, a sentiment that helps explain his mésalliance with Aspasia Manos.

Legacy

Alexander's death raised questions about the succession to the throne as well as the nature of the Greek regime. As the king had contracted an unequal marriage, his descendants were not in the line of succession. The

Alexander's death raised questions about the succession to the throne as well as the nature of the Greek regime. As the king had contracted an unequal marriage, his descendants were not in the line of succession. The Hellenic Parliament

The Hellenic Parliament ( el, Ελληνικό Κοινοβούλιο, Elliniko Kinovoulio; formally titled el, Βουλή των Ελλήνων, Voulí ton Ellínon, Boule (ancient Greece), Boule of the Greeks, Hellenes, label=none), also kno ...

demanded that Constantine I and Crown Prince George be excluded from the succession but sought to preserve the monarchy by selecting another member of the royal house as the new sovereign. On 29 October 1920, the Greek minister in Berne, acting under the direction of the Greek authorities, offered the throne to Alexander's younger brother, Prince Paul. Paul, however, refused to become king while his father and elder brother were alive, insisting that neither of them had renounced their rights to the throne and that he therefore could never legitimately wear the crown.

The throne remained vacant and the legislative elections of 1920 turned into an open conflict between the Venizelists, who favored republicanism, and the supporters of the ex-King Constantine. On 14 November 1920, with the war with Turkey dragging on, the monarchists won, and Dimitrios Rallis

Dimitrios Rallis (Greek: Δημήτριος Ράλλης; 1844–1921) was a Greek politician.

He was born in Athens in 1844. He was descended from an old Greek political family. Before Greek independence, his grandfather, Alexander Rallis, ...

became prime minister; Venizelos (who lost his own parliamentary seat) chose to leave Greece in self-exile. Rallis asked Queen Olga to become regent until Constantine's return.

Under the restored King Constantine I, whose return was endorsed overwhelmingly in a referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

, Greece went on to lose the Greco–Turkish War with heavy military and civilian casualties. The territory gained on the Turkish mainland during Alexander's reign was lost. Alexander's death in the midst of an election campaign helped destabilize the Venizelos regime, and the resultant loss of Allied support contributed to the failure of Greece's territorial ambitions. Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

wrote, "it is perhaps no exaggeration to remark that a quarter of a million persons died of this monkey's bite."

Issue

Alexander's daughter by Aspasia Manos,Alexandra

Alexandra () is the feminine form of the given name Alexander (, ). Etymologically, the name is a compound of the Greek verb (; meaning 'to defend') and (; GEN , ; meaning 'man'). Thus it may be roughly translated as "defender of man" or "prot ...

(1921–1993), was born five months after his death. Initially, the government took the line that since Alexander had married Aspasia without the permission of his father or the church, his marriage was illegal and his posthumous daughter was illegitimate. However, in July 1922, Parliament passed a law which allowed the King to recognize royal marriages retroactively on a non-dynastic basis. That September, Constantine—at Sophia's insistence—recognized his son's marriage to Aspasia and granted her the style of "Princess Alexander". Her daughter (Constantine I's granddaughter) was legitimized as a princess of Greece and Denmark, and later married King Peter II of Yugoslavia

Peter II ( sr-Cyrl, Петар II Карађорђевић, Petar II Karađorđević; 6 September 1923 – 3 November 1970) was the last king of Yugoslavia, reigning from October 1934 until his deposition in November 1945. He was the last r ...

in London in 1944. They had one child: Alexander, Crown Prince of Yugoslavia

Alexander, Crown Prince of Yugoslavia ( sr, Александар Карађорђевић, Престолонаследник Југославије; born 17 July 1945 in London), is the head of the House of Karađorđević, the former royal h ...

.Montgomery-Massingberd, pp. 327, 536, 544.

Ancestry

Footnotes and references

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* *External links

Film of King Alexander's funeral

British Pathé {{DEFAULTSORT:Alexander of Greece 1893 births 1920 deaths 19th-century Greek people 20th-century Greek monarchs Kings of Greece Greek princes Danish princes House of Glücksburg (Greece) Eastern Orthodox monarchs Grand Croix of the Légion d'honneur Honorary Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Greek people of World War I Greek generals Eastern Orthodox Christians from Greece Politicians from Athens 1920 in Greece Deaths due to animal attacks Deaths from sepsis Burials at Tatoi Palace Royal Cemetery Sons of kings