Alawites in Lebanon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lebanese Shia Muslims ( ar, المسلمون الشيعة اللبنانيين), historically known as ''matāwila'' ( ar, متاولة, plural of ''mutawālin'' ebanese pronounced as ''metouali'' refers to

/ref> Most of its adherents live in the northern and western area of the

Historical Accounts

The territories of present-day Lebanon register less than neighboring regions in the historical accounts from the Abbasid and Fatimid eras. Persian traveler

Historical Accounts

The territories of present-day Lebanon register less than neighboring regions in the historical accounts from the Abbasid and Fatimid eras. Persian traveler

The three Shia principalities underwent different historical trajectories. The Harfush initially did not challenge the new Ottoman authority, but in 1518 the Ottomans executed an anonymous Ibn Harfush, governor of Baalbek, along with the Bedouin Emir Ibn al-Hanash for acting against the state. At their high-point, Harfush domains extended from the Beqaa valley into

The three Shia principalities underwent different historical trajectories. The Harfush initially did not challenge the new Ottoman authority, but in 1518 the Ottomans executed an anonymous Ibn Harfush, governor of Baalbek, along with the Bedouin Emir Ibn al-Hanash for acting against the state. At their high-point, Harfush domains extended from the Beqaa valley into  In 1781, Shia autonomy diminished under

In 1781, Shia autonomy diminished under

On the other hand, Shia cleric Abdul Husayn Sharafeddine had organized and lead

On the other hand, Shia cleric Abdul Husayn Sharafeddine had organized and lead

From late 1940s onward, many Shias moved to the

From late 1940s onward, many Shias moved to the

Shia Twelvers in Lebanon refers to the Shia Islam, Shia Muslim

Shia Twelvers in Lebanon refers to the Shia Islam, Shia Muslim

There are an estimated 100,000Riad Yazbeck.

There are an estimated 100,000Riad Yazbeck.

Return of the Pink Panthers?

'. Mideast Monitor. Vol. 3, No. 2, August 2008

/ref> of Lebanon's population."Lebanon: people and society"

/ref>

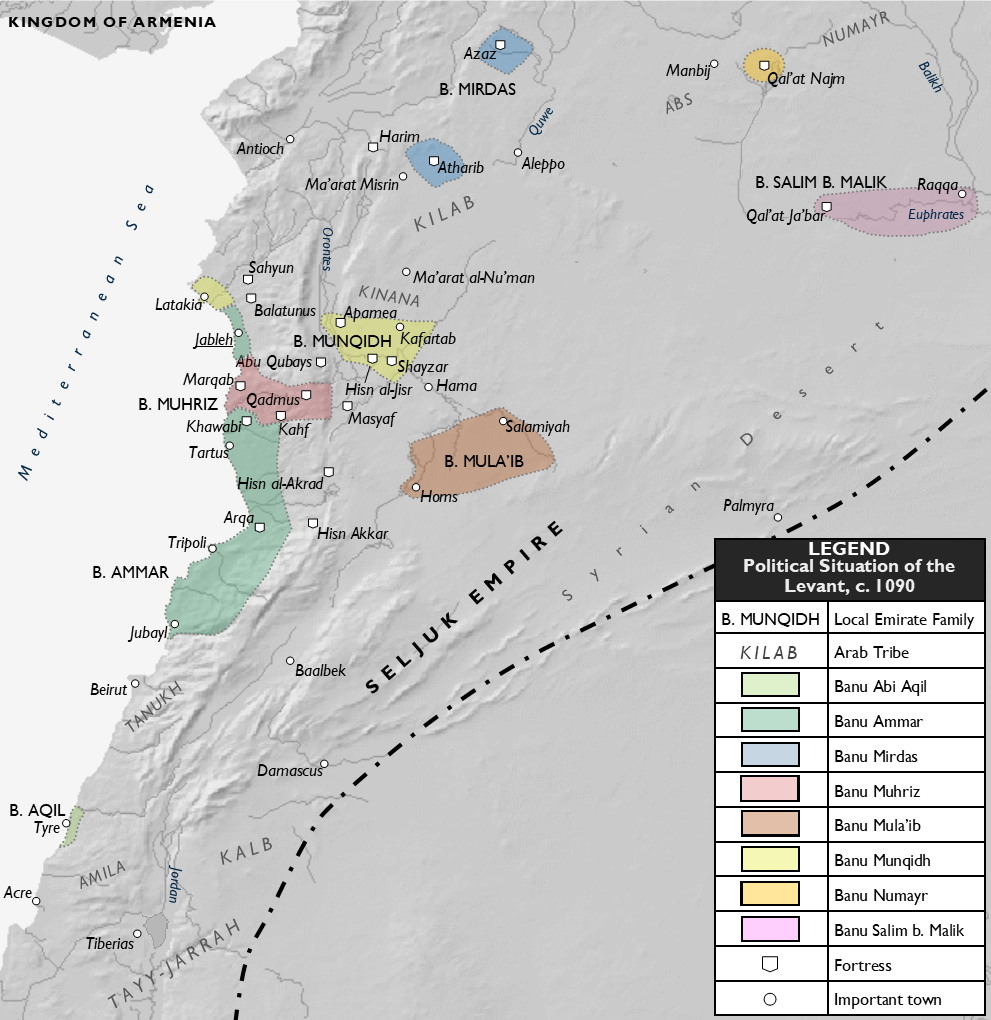

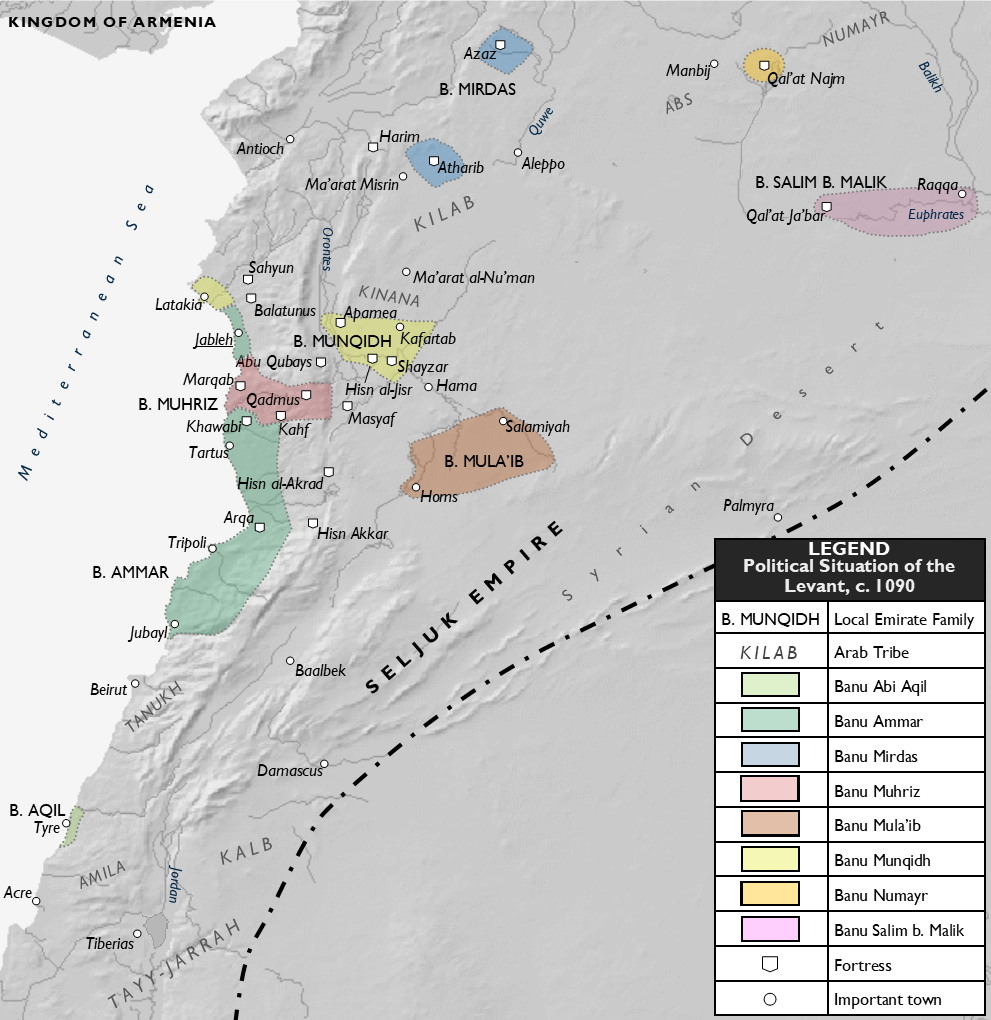

The Shia Rulers of Banu Ammar, Banu Mardas and the Mazidi

{{Lebanese people by religious background Lebanese Shia Muslims, Shia Islam in Lebanon,

Lebanese people

The Lebanese people ( ar, الشعب اللبناني / ALA-LC: ', ) are the people inhabiting or originating from Lebanon. The term may also include those who had inhabited Mount Lebanon and the Anti-Lebanon Mountains prior to the creation ...

who are adherents of the Shia branch of Islam in Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus li ...

, which plays a major role along Lebanon's main Sunni, Maronite and Druze sects. Shia Islam in Lebanon has a history of more than a millennium. According to the ''CIA World Factbook

''The World Factbook'', also known as the ''CIA World Factbook'', is a reference resource produced by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) with almanac-style information about the countries of the world. The official print version is available ...

'', Shia Muslims constituted an estimated 28% of Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus li ...

's population in 2018."Lebanon: people and society"/ref> Most of its adherents live in the northern and western area of the

Beqaa Valley

The Beqaa Valley ( ar, links=no, وادي البقاع, ', Lebanese ), also transliterated as Bekaa, Biqâ, and Becaa and known in classical antiquity as Coele-Syria, is a fertile valley in eastern Lebanon. It is Lebanon's most important ...

, Southern Lebanon

Southern Lebanon () is the area of Lebanon comprising the South Governorate and the Nabatiye Governorate. The two entities were divided from the same province in the early 1990s. The Rashaya and Western Beqaa Districts, the southernmost distric ...

and Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

. The great majority of Shia Muslims in Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus li ...

are Twelver

Twelver Shīʿīsm ( ar, ٱثْنَا عَشَرِيَّة; '), also known as Imāmīyyah ( ar, إِمَامِيَّة), is the largest branch of Shīʿa Islam, comprising about 85 percent of all Shīʿa Muslims. The term ''Twelver'' refers t ...

s. However, a small minority of them are Alawites

The Alawis, Alawites ( ar, علوية ''Alawīyah''), or pejoratively Nusayris ( ar, نصيرية ''Nuṣayrīyah'') are an ethnoreligious group that lives primarily in Levant and follows Alawism, a sect of Islam that originated from Shia Isla ...

and Ismaili

Isma'ilism ( ar, الإسماعيلية, al-ʾIsmāʿīlīyah) is a branch or sub-sect of Shia Islam. The Isma'ili () get their name from their acceptance of Imam Isma'il ibn Jafar as the appointed spiritual successor (imām) to Ja'far al-Sa ...

.

Under the terms of an unwritten agreement known as the National Pact

The National Pact ( ar, الميثاق الوطني, translit-std=DIN, translit=al Mithaq al Watani) is an unwritten agreement that laid the foundation of Lebanon as a multiconfessional state following negotiations between the Shia, Sunni, and Ma ...

between the various political and religious leaders of Lebanon, Shias are the only sect eligible for the post of Speaker of Parliament

The speaker of a deliberative assembly, especially a legislative body, is its presiding officer, or the chair. The title was first used in 1377 in England.

Usage

The title was first recorded in 1377 to describe the role of Thomas de Hungerf ...

.

History

Origins

The cultural and linguistic heritage of theLebanese people

The Lebanese people ( ar, الشعب اللبناني / ALA-LC: ', ) are the people inhabiting or originating from Lebanon. The term may also include those who had inhabited Mount Lebanon and the Anti-Lebanon Mountains prior to the creation ...

is a blend of both indigenous elements and the foreign cultures that have come to rule the land and its people over the course of thousands of years. In a 2013 interview the lead investigator, Pierre Zalloua

Pierre Zalloua ( ar, بيار زلّوعة) is a Lebanese biologist. His contributions to biology include numerous researches in genetic predisposition to diseases such as type 1 diabetes and β-thalassemia. He is most noted for taking part in ...

, pointed out that genetic variation preceded religious variation and divisions: "Lebanon already had well-differentiated communities with their own genetic peculiarities, but not significant differences, and religions came as layers of paint on top. There is no distinct pattern that shows that one community carries significantly more Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

n than another."

Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus li ...

throughout its history was home of many historic peoples who inhabited the region. The Lebanese coast was mainly inhabited by Phoenician Canaanites throughout the Bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals, such as phosphorus, or metalloids such ...

and Iron

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in f ...

ages, who built the cities of Tyre, Sidon

Sidon ( ; he, צִידוֹן, ''Ṣīḏōn'') known locally as Sayda or Saida ( ar, صيدا ''Ṣaydā''), is the third-largest city in Lebanon. It is located in the South Governorate, of which it is the capital, on the Mediterranean coast. ...

, Byblos

Byblos ( ; gr, Βύβλος), also known as Jbeil or Jubayl ( ar, جُبَيْل, Jubayl, locally ; phn, 𐤂𐤁𐤋, , probably ), is a city in the Keserwan-Jbeil Governorate of Lebanon. It is believed to have been first occupied between 880 ...

and Tripoli

Tripoli or Tripolis may refer to:

Cities and other geographic units Greece

*Tripoli, Greece, the capital of Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (region of Arcadia), a district in ancient Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (Larisaia), an ancient Greek city in ...

, which was founded as a center of a confederation between Aradians

Arwad, the classical Aradus ( ar, أرواد), is a town in Syria on an eponymous island in the Mediterranean Sea. It is the administrative center of the Arwad Subdistrict (''nahiyah''), of which it is the only locality.Bekaa valley

The Beqaa Valley ( ar, links=no, وادي البقاع, ', Lebanese ), also transliterated as Bekaa, Biqâ, and Becaa and known in classical antiquity as Coele-Syria, is a fertile valley in eastern Lebanon. It is Lebanon's most important ...

was known as ''Amqu

The Amqu (also Amka, Amki, Amq) is a region (now in eastern Lebanon), equivalent to the Beqaa Valley region, named in the 1350– 1335 BC Amarna letters corpus.

In the Amarna letters, two other associated regions appear to be east(?) and north(?) ...

'' in the Bronze Age, and was part of Amorite

The Amorites (; sux, 𒈥𒌅, MAR.TU; Akkadian: 𒀀𒈬𒊒𒌝 or 𒋾𒀉𒉡𒌝/𒊎 ; he, אֱמוֹרִי, 'Ĕmōrī; grc, Ἀμορραῖοι) were an ancient Northwest Semitic-speaking people from the Levant who also occupied lar ...

kingdom of Qatna

Qatna (modern: ar, تل المشرفة, Tell al-Mishrifeh) (also Tell Misrife or Tell Mishrifeh) was an ancient city located in Homs Governorate, Syria. Its remains constitute a tell situated about northeast of Homs near the village of al-M ...

and later Amurru kingdom Amurru may refer to:

* Amurru kingdom, roughly current day western Syria and northern Lebanon

* Amorite, ancient Syrian people

* Amurru (god)

Amurru, also known under the Sumerian name Martu, was a Mesopotamian god who served as the divine perso ...

, and had local city-states such as Enišasi

Enišasi, was a city, or city-state located in the Beqaa Valley-(called ''Amqu'', or ''Amka'') of Lebanon, during the 1350- 1335 BC Amarna letters correspondence. Of the 382–Amarna letters, Enišasi is only referenced in two letters. Eniša ...

. During the Iron Age, the Bekaa was dominated by the Aramaeans

The Arameans ( oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; syc, ܐܪ̈ܡܝܐ, Ārāmāyē) were an ancient Semitic-speaking people in the Near East, first recorded in historical sources from the late 12th century BCE. The Aramean ...

, who formed kingdoms nearby in Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

and Hamath

, timezone = EET

, utc_offset = +2

, timezone_DST = EEST

, utc_offset_DST = +3

, postal_code_type =

, postal_code =

, ar ...

, and established the kingdom of Aram-Zobah

Zobah or Aram-Zobah ( ʾ''Ărām-Ṣōḇāʾ'') was an early Aramean state mentioned in the Hebrew Bible, which extended north-east of biblical King David's realm.

A. F. Kirkpatrick, in the Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges (1896), plac ...

where Hazael

Hazael (; he, חֲזָאֵל, translit=Ḥazaʾēl, or , romanized as: ; oar, 𐡇𐡆𐡀𐡋, translit= , from the triliteral Semitic root ''h-z-y'', "to see"; his full name meaning, " El/God has seen"; akk, 𒄩𒍝𒀪𒀭, Ḫa-za-’- il ...

might have been born, and was later also settled by Itureans, who were likely Arabs

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Wester ...

themselves. These Itureans inhabited the hills above Tyre in Southern Lebanon

Southern Lebanon () is the area of Lebanon comprising the South Governorate and the Nabatiye Governorate. The two entities were divided from the same province in the early 1990s. The Rashaya and Western Beqaa Districts, the southernmost distric ...

, historically known as Jabal Amel

Jabal Amil ( ar, جبل عامل, Jabal ʿĀmil), also spelled Jabal Amel and historically known as Jabal Amila, is a cultural and geographic region in Southern Lebanon largely associated with its long-established, predominantly Twelver Shia Musl ...

, since at least the times of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

, who fought them after they blocked his army's access to wood supply.

During Roman rule, Aramaic

The Aramaic languages, short Aramaic ( syc, ܐܪܡܝܐ, Arāmāyā; oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; tmr, אֲרָמִית), are a language family containing many varieties (languages and dialects) that originated in ...

became the lingua franca

A lingua franca (; ; for plurals see ), also known as a bridge language, common language, trade language, auxiliary language, vehicular language, or link language, is a language systematically used to make communication possible between groups ...

of the entire Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

and Lebanon, replacing spoken Phoenician on the coast, while Greek was used as language of administration, education and trading. It is important to note that most villages and towns in Lebanon today have Aramaic names, reflecting this heritage. However, Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

became the only fully Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

speaking city in the whole east. The Iturean Kingdom of Chalcis

Chalcis was a small ancient Iturean majority kingdom situated in the Beqaa Valley, named for and originally based from the city of the same name. The ancient city of Chalcis (a.k.a. Chalcis sub Libanum, Chalcis of Coele-Syria was located midway be ...

became vassal state of the Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

s after they consolidated their rule over most of the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

in 64 BC, and at their peak they managed to impose control on much of the Phoenician coast and Galilee including southern Lebanon, until the Romans fully incorporated them in 92 CE. On the coast, Tyre prospered under the Romans and was allowed to keep much of its independence as a "civitas foederata A ''civitas foederata'', meaning "allied state/community", was the most elevated type of autonomous cities and local communities under Roman rule.

Each Roman province comprised a number of communities of different status. Alongside Roman colonies o ...

". On the other hand, Jabal Amel was inhabited by Banu Amilah, its namesake, who have particular importance for the Lebanese Shia for adopting and nurturing Shi'ism in the southern population. The Banu Amilah were part of the Nabataean

The Nabataeans or Nabateans (; Nabataean Aramaic: , , vocalized as ; Arabic: , , singular , ; compare grc, Ναβαταῖος, translit=Nabataîos; la, Nabataeus) were an ancient Arab people who inhabited northern Arabia and the southern Lev ...

Arab ''foederati

''Foederati'' (, singular: ''foederatus'' ) were peoples and cities bound by a treaty, known as ''foedus'', with Rome. During the Roman Republic, the term identified the ''socii'', but during the Roman Empire, it was used to describe foreign stat ...

'' of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

, and they were connected to other pre-Islamic Arabs such as Judham

The Judham ( ar, بنو جذام, ') was an Arab tribe that inhabited the southern Levant and northwestern Arabia during the Byzantine and early Islamic eras (5th–8th centuries). Under the Byzantines, the tribe was nominally Christian and fough ...

and Balqayn, whose presence in the region likely dates back to Biblical times according to Irfan Shahîd

Irfan Arif Shahîd ( ar, عرفان عارف شهيد ; Nazareth, Mandatory Palestine, January 15, 1926 – Washington, D.C., November 9, 2016), born as Erfan Arif Qa'war (), was a scholar in the field of Oriental studies. He was from 1982 unti ...

. As the Muslim conquest of the Levant

The Muslim conquest of the Levant ( ar, فَتْحُ الشَّام, translit=Feth eş-Şâm), also known as the Rashidun conquest of Syria, occurred in the first half of the 7th century, shortly after the rise of Islam."Syria." Encyclopædia Br ...

reached Lebanon, these Arab tribes received the most power which encouraged the non-Arabic-speaking population to adopt Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

as the main language.

Early Islamic period

In historian Jaafar al-Muhajir's assessment, the spread of Shia Islam inLebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus li ...

and the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

was a complex, multi-layered process throughout history. Accordingly, the presence of pro-Alid tribes such as Hamdan and Madh'hij

Madhḥij ( ar, مَذْحِج) is a large Qahtanite Arab tribal confederation. It is located in south and central Arabia. This confederation participated in the early Muslim conquests and was a major factor in the conquest of the Persian empire ...

in the region, possibly after the Hasan–Muawiya treaty

The Hasan–Mu'awiya treaty was a political peace treaty signed in 661 between Caliph Hasan ibn Ali and Mu'awiya I () to bring the First Fitna (656–661) to a close. Under this treaty, Hasan ceded the caliphate to Mu'awiya on the condition tha ...

in 661 CE, likely acted as a vector that facilitated the spread of Shi'ism among segments of the local populations living among them in Jabal Amel

Jabal Amil ( ar, جبل عامل, Jabal ʿĀmil), also spelled Jabal Amel and historically known as Jabal Amila, is a cultural and geographic region in Southern Lebanon largely associated with its long-established, predominantly Twelver Shia Musl ...

, Galilee, Beqaa valley

The Beqaa Valley ( ar, links=no, وادي البقاع, ', Lebanese ), also transliterated as Bekaa, Biqâ, and Becaa and known in classical antiquity as Coele-Syria, is a fertile valley in eastern Lebanon. It is Lebanon's most important ...

, Tyre and Tripoli

Tripoli or Tripolis may refer to:

Cities and other geographic units Greece

*Tripoli, Greece, the capital of Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (region of Arcadia), a district in ancient Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (Larisaia), an ancient Greek city in ...

, where anti-state sentiment was common due to the discrimination and ongoing marginalization of the region under the Abbasids

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

. Among the locals were Banu Amilah, an Arab tribe that inhabited Jabal Amel in the 7th century CE. According to Husayn Muruwwa

''Husayn Muruwwa'' (also spelt ''Hussein Mroue'' or ''Mroueh'') (1908/1910-February 17, 1987) was a Lebanese Marxist intellectual, journalist, author, and literary critic. His longest and most famous work, "Materialist Tendencies in Arabic-Islami ...

, Shiism was one option among many for the communities of Jabal Amel, but for them, a positive and inviting dialectical relationship between the theological construct of Imamism

Twelver Shīʿīsm ( ar, ٱثْنَا عَشَرِيَّة; '), also known as Imāmīyyah ( ar, إِمَامِيَّة), is the largest branch of Shīʿa Islam, comprising about 85 percent of all Shīʿa Muslims. The term ''Twelver'' refers t ...

and its social milieu gave precedence to the Shiite possibility. Such a transformation may have been attested in Homs

Homs ( , , , ; ar, حِمْص / ALA-LC: ; Levantine Arabic: / ''Ḥomṣ'' ), known in pre-Islamic Syria as Emesa ( ; grc, Ἔμεσα, Émesa), is a city in western Syria and the capital of the Homs Governorate. It is Metres above sea level ...

whereby according to Yaqut al-Hamawi

Yāqūt Shihāb al-Dīn ibn-ʿAbdullāh al-Rūmī al-Ḥamawī (1179–1229) ( ar, ياقوت الحموي الرومي) was a Muslim scholar of Byzantine Greek ancestry active during the late Abbasid period (12th-13th centuries). He is known fo ...

, the people of the city were strong supporters of the Umayyads, but became adamant, ghulat

The ( ar, غلاة, 'exaggerators', 'extremists', 'transgressors', singular ) were a branch of early Shi'i Muslims thus named by other Shi'i and Sunni Muslims for their purportedly 'exaggerated' veneration of the prophet Muhammad (–632) and his ...

Shiites after their demise in 750. Prominent Emesene Shiites figure in the late 8th century, including Abd al-Salam al-Homsi (777–850 CE), a notable Shia poet who never left his native Homs.

Millenialist expectations increased upon the deep crisis of the Abbasid dynasty during the decade-long Anarchy at Samarra

The Anarchy at Samarra () was a period of extreme internal instability from 861 to 870 in the history of the Abbasid Caliphate, marked by the violent succession of four caliphs, who became puppets in the hands of powerful rival military groups.

T ...

(c. 861–870), the rise of breakaway and autonomous regimes in the provinces, the large-scale Zanj Rebellion

The Zanj Rebellion ( ar, ثورة الزنج ) was a major revolt against the Abbasid Caliphate, which took place from 869 until 883. Begun near the city of Basra in present-day southern Iraq and led by one Ali ibn Muhammad, the insurrection invol ...

(c. 869–883), all of which increased the appeal to Isma'ilism

Isma'ilism ( ar, الإسماعيلية, al-ʾIsmāʿīlīyah) is a branch or sub-sect of Shia Islam. The Isma'ili () get their name from their acceptance of Imam Isma'il ibn Jafar as the appointed spiritual successor (imām) to Ja'far al-Sa ...

, and moreover the establishment of Qarmatian

The Qarmatians ( ar, قرامطة, Qarāmiṭa; ) were a militant Isma'ili Shia movement centred in al-Hasa in Eastern Arabia, where they established a religious-utopian socialist state in 899 CE. Its members were part of a movement that adhe ...

Isma'ilis in 899 in Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, and the rise of the Twelver Shiite Hamdanids

The Hamdanid dynasty ( ar, الحمدانيون, al-Ḥamdāniyyūn) was a Twelver Shia Arab dynasty of Northern Mesopotamia and Syria (890–1004). They descended from the ancient Banu Taghlib Christian tribe of Mesopotamia and Eastern A ...

in 890 which further elevated Twelver prestige and following.

Historical Accounts

The territories of present-day Lebanon register less than neighboring regions in the historical accounts from the Abbasid and Fatimid eras. Persian traveler

Historical Accounts

The territories of present-day Lebanon register less than neighboring regions in the historical accounts from the Abbasid and Fatimid eras. Persian traveler Nasir Khusraw

Abu Mo’in Hamid ad-Din Nasir ibn Khusraw al-Qubadiani or Nāsir Khusraw Qubādiyānī Balkhi ( fa, ناصر خسرو قبادیانی, Nasir Khusraw Qubadiani) also spelled as ''Nasir Khusrow'' and ''Naser Khosrow'' (1004 – after 1070 CE) w ...

's presents a unique account of Tyre and Tripoli during his visit in 1040s, describing them as being majority Shia Muslim with dedicated Shia shrines on the outskirts. Several Tyrian Shiite figures are mentioned more than a century earlier; these include Muhammad bin Ibrahim as-Souri (fl. 883 CE) and Abbasid-era poet Abdul Muhsin as-Souri (b. 950 CE), a student of Al-Shaykh Al-Mufid

Abu 'Abd Allah Muhammad ibn Muhammad ibn al-Nu'man al-'Ukbari al-Baghdadi, known as al-Shaykh al-Mufid () and Ibn al-Mu'allim (c.9481022 CE), was a prominent Twelver Shia theologian. His father was a teacher (''mu'allim''), hence the name Ibn ...

.

Some of the earlier accounts for inner Jabal Amel

Jabal Amil ( ar, جبل عامل, Jabal ʿĀmil), also spelled Jabal Amel and historically known as Jabal Amila, is a cultural and geographic region in Southern Lebanon largely associated with its long-established, predominantly Twelver Shia Musl ...

are given by Al-Maqdisi

Shams al-Dīn Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ibn Abī Bakr al-Maqdisī ( ar, شَمْس ٱلدِّيْن أَبُو عَبْد ٱلله مُحَمَّد ابْن أَحْمَد ابْن أَبِي بَكْر ٱلْمَقْدِسِي), ...

(c. 966–985), who mentions that half of Hunin

Hunin ( ar, هونين) was a Palestinian Arab village in the Galilee Panhandle part of Mandatory Palestine close to the Lebanese border. It was the second largest village in the district of Safed, but was depopulated in 1948.Gelber, 2006, p. ...

and Qadas

Qadas (also Cadasa; ar, قدس) was a Palestinian village located 17 kilometers northeast of Safad that was depopulated during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. One of seven Shia Muslim villages, called ''Metawalis'', that fell within the boundaries of ...

inhabitants were Shia Muslims. Al-Maqdisi also relays important accounts regarding the predominance of Shiite Muslims in Tiberias, which lay within historical Jabal Amel. Tiberias was the home of Alid

The Alids are those who claim descent from the '' rāshidūn'' caliph and Imam ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib (656–661)—cousin, son-in-law, and companion of the Islamic prophet Muhammad—through all his wives. The main branches are the (inc ...

families during the 10th century and also home to the Ash'ari tribe of Madh'hij

Madhḥij ( ar, مَذْحِج) is a large Qahtanite Arab tribal confederation. It is located in south and central Arabia. This confederation participated in the early Muslim conquests and was a major factor in the conquest of the Persian empire ...

who founded Qom, one of the holy cities of Shia Islam, in 703, as al-Ya'qubi

ʾAbū l-ʿAbbās ʾAḥmad bin ʾAbī Yaʿqūb bin Ǧaʿfar bin Wahb bin Waḍīḥ al-Yaʿqūbī (died 897/8), commonly referred to simply by his nisba al-Yaʿqūbī, was an Arab Muslim geographer and perhaps the first historian of world cult ...

notes during his travels in the 880s; Tiberias was also the home of a prominent Alid figure who was killed by al-Ikhshid on the charge of being sympathetic with the Qarmatians in 903. Shiites also reportedly formed half of the population of Nablus

Nablus ( ; ar, نابلس, Nābulus ; he, שכם, Šəḵem, ISO 259-3: ; Samaritan Hebrew: , romanized: ; el, Νεάπολις, Νeápolis) is a Palestinian city in the West Bank, located approximately north of Jerusalem, with a populati ...

and most of Amman

Amman (; ar, عَمَّان, ' ; Ammonite language, Ammonite: 𐤓𐤁𐤕 𐤏𐤌𐤍 ''Rabat ʻAmān'') is the capital and largest city of Jordan, and the country's economic, political, and cultural center. With a population of 4,061,150 a ...

's population per al-Maqdisi.

On the other hand, further east in the Bekaa valley

The Beqaa Valley ( ar, links=no, وادي البقاع, ', Lebanese ), also transliterated as Bekaa, Biqâ, and Becaa and known in classical antiquity as Coele-Syria, is a fertile valley in eastern Lebanon. It is Lebanon's most important ...

, sources regarding the area are scarce and generally uninformative. According to al-Muhajir, Yaman-affiliated tribes which lived in the surroundings of Baalbek

Baalbek (; ar, بَعْلَبَكّ, Baʿlabakk, Syriac-Aramaic: ܒܥܠܒܟ) is a city located east of the Litani River in Lebanon's Beqaa Valley, about northeast of Beirut. It is the capital of Baalbek-Hermel Governorate. In Greek and Roman ...

before 872, such as Banu Kalb

The Banu Kalb ( ar, بنو كلب) was an Arab tribe which mainly dwelt in the desert between northwestern Arabia and central Syria. The Kalb was involved in the tribal politics of the eastern frontiers of the Byzantine Empire, possibly as early ...

and Banu Hamdan

Banu Hamdan ( ar, بَنُو هَمْدَان; Musnad: 𐩠𐩣𐩵𐩬) is an ancient, large, and prominent Arab tribe in northern Yemen.

Origins and location

The Hamdan stemmed from the eponymous progenitor Awsala (nickname Hamdan) whose desce ...

that were aligned with Alid sentiments at the time, likely played a role in spreading Shia Islam in the Bekaa and anti-Lebanon mountains. Qarmatian influence may have played a role as well, after gaining foothold in neighboring Homs before the Abbasids kicked them out in 903. In 912, Ibn al-Rida, a descendant of the 10th Imam Ali al-Hadi

ʿAlī ibn Muḥammad al-Hādī ( ar, عَلِيّ ٱبْن مُحَمَّد ٱلْهَادِي; 828 – 868 CE) was a descendant of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and the tenth of the Twelve Imams, succeeding his father, Muhammad al-Jawad. He ...

, started a rebellion in the nearby Damascene countryside against the Abbasid governor of Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

in an attempt to establish Hashemite

The Hashemites ( ar, الهاشميون, al-Hāshimīyūn), also House of Hashim, are the royal family of Jordan, which they have ruled since 1921, and were the royal family of the kingdoms of Hejaz (1916–1925), Syria (1920), and Iraq (1921� ...

authority in the area; Ibn al-Rida was subsequently defeated and killed in battle near Damascus and his head was paraded in Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

. According to al-Muhajir, Shiite presence in the Bekaa valley was further reinforced by migrants from Mount Lebanon

Mount Lebanon ( ar, جَبَل لُبْنَان, ''jabal lubnān'', ; syr, ܛܘܪ ܠܒ݂ܢܢ, ', , ''ṭūr lewnōn'' french: Mont Liban) is a mountain range in Lebanon. It averages above in elevation, with its peak at .

Geography

The Mount Le ...

in 1305 and Ottoman period

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, and migrants from the Shias villages in Anti-Lebanon Mountains

The Anti-Lebanon Mountains ( ar, جبال لبنان الشرقية, Jibāl Lubnān ash-Sharqiyyah, Eastern Mountains of Lebanon; Lebanese Arabic: , , "Eastern Mountains") are a southwest–northeast-trending mountain range that forms most of th ...

.

Slightly later, the Hamdanids

The Hamdanid dynasty ( ar, الحمدانيون, al-Ḥamdāniyyūn) was a Twelver Shia Arab dynasty of Northern Mesopotamia and Syria (890–1004). They descended from the ancient Banu Taghlib Christian tribe of Mesopotamia and Eastern A ...

in Aleppo were the first dynasty of Twelver

Twelver Shīʿīsm ( ar, ٱثْنَا عَشَرِيَّة; '), also known as Imāmīyyah ( ar, إِمَامِيَّة), is the largest branch of Shīʿa Islam, comprising about 85 percent of all Shīʿa Muslims. The term ''Twelver'' refers t ...

Shia Muslims to break away from the centralized rule of Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

. They emerged in Mosul

Mosul ( ar, الموصل, al-Mawṣil, ku, مووسڵ, translit=Mûsil, Turkish: ''Musul'', syr, ܡܘܨܠ, Māwṣil) is a major city in northern Iraq, serving as the capital of Nineveh Governorate. The city is considered the second large ...

and took control of Aleppo

)), is an adjective which means "white-colored mixed with black".

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize =

, map_caption =

, image_map1 =

...

and most of northern Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

by 944, further expanding their territory into Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, defeating the Byzantines on several occasions and further elevating Twelver prestige. Aleppo gradually became a hub of Shiite religious seminaries (hawza

A hawza ( ar, حوزة) or ḥawzah ʿilmīyah ( ar, حوزة علمیة) is a seminary where Shi'a Muslim scholars are educated.

The word ''ḥawzah'' is found in Arabic as well as the Persian language. In Arabic, the word means "to hold so ...

s), linking Aleppo to Shia-populated Tripoli and Tyre in Lebanon.

Fatimid Domination

In 970, the Isma'ili Shia Fatimids

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Isma'ilism, Ismaili Shia Islam, Shi'a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries AD. Spanning a large area of North Africa, it ranged from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the ea ...

initiated their conquest of the Levant. The Fatimids patronized Isma'ili Shiism and set the ground for it to flourish in several regions and towns, including the Syrian coastal mountain region. While they embraced their Shia identity, The Fatimids quarrelled with local Shia dynasties. The Hamdanids initially refused to accept Fatimid hegemony, but were defeated by 1003. During these events, rebels in Tyre drove out the Fatimids for two years until the revolt was suppressed in 998. A decade later, the Twelver Shia Salih ibn Mirdas

Abu Ali Salih ibn Mirdas ( ar, ابو علي صالح بن مرداس, Abū ʿAlī Ṣāliḥ ibn Mirdās), also known by his ''laqab'' (honorific epithet) Asad al-Dawla ('Lion of the State'), was the founder of the Mirdasid dynasty and emir of ...

rose against the Fatimids and by 1025 managed to conquer most of Syria, western Iraq and parts of Lebanon. In similar action, the Shia dynasty of Banu Ammar

The Banu Ammar ( ar, بنو عمار, Banū ʿAmmār, Sons of Ammar) were a family of Shia Muslim magistrates (''qadi''s) who ruled the city of Tripoli in what is now Lebanon from c.1065 until 1109.

History

Accounts vary regarding the origin o ...

declared the independence of Tripoli in 1070, expanding their borders to the land between Jableh

)

, settlement_type = City

, motto =

, image_skyline = Jableh Collage.jpg

, imagesize = 250px

, image_caption = General view of city and port • Roman Amphitheater• Al ...

in the north and Jbeil in the south. Banu Ammar were avid lovers of sciences, literature and poetry, and built the library of Dar al-'ilm, one of the significant libraries of the medieval Islamic world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. In ...

, in 1069.

Under Crusader rule and Mongol invasions

Upon the arrival of theFirst Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Islamic ru ...

, Tripoli and Tyre resisted crusader attempts to seize the two cities. Tripoli was subject to a 4-year long siege which culminated with its fall in 1109. On the other hand, Tyre successfully broke a major siege in 1112 with the help of Toghtekin

Toghtekin or Tughtekin (Modern tr, Tuğtekin; Arabicised epithet: ''Zahir ad-Din Tughtikin''; died February 12, 1128), also spelled Tughtegin, was a Turkic military leader, who was ''atabeg'' of Damascus from 1104 to 1128. He was the founder o ...

, but fell to the Venetian Crusade

The Venetian Crusade of 1122–1124 was an expedition to the Holy Land launched by the Republic of Venice that succeeded in capturing Tyre.

It was an important victory at the start of a period when the Kingdom of Jerusalem would expand to its ...

in 1124.

In social terms, Tripoli and Tyre experienced a drastic upheaval with the crusader conquests. Many Muslims, seemingly predominantly Shiites, were killed or departed for the interior, who were replaced by tens of thousands of Franks through several decades.

The years-long siege of Tripoli and the brutal aftermath of its fall caused an influx outside of Tripoli. Such influx either inaugurated the Shia community of Keserwan or inflated a previously established rural Shiite community there. According to al-Muhajir, a similar thing would have happened in Jabal Amel

Jabal Amil ( ar, جبل عامل, Jabal ʿĀmil), also spelled Jabal Amel and historically known as Jabal Amila, is a cultural and geographic region in Southern Lebanon largely associated with its long-established, predominantly Twelver Shia Musl ...

which received a population influx from the Shia-populated urban centers at the time, most notably Tyre and Tiberias, as well as Amman

Amman (; ar, عَمَّان, ' ; Ammonite language, Ammonite: 𐤓𐤁𐤕 𐤏𐤌𐤍 ''Rabat ʻAmān'') is the capital and largest city of Jordan, and the country's economic, political, and cultural center. With a population of 4,061,150 a ...

, Nablus

Nablus ( ; ar, نابلس, Nābulus ; he, שכם, Šəḵem, ISO 259-3: ; Samaritan Hebrew: , romanized: ; el, Νεάπολις, Νeápolis) is a Palestinian city in the West Bank, located approximately north of Jerusalem, with a populati ...

and the surrounding countryside. Shias in the Bekaa valley remained under Muslim rule and were on good terms with Bahramshah

Al-Malik al-Amjad Bahramshah was the Ayyubid emir of Baalbek between 1182–1230 (578–627 AH).

Reign

Bahramshah succeeded his father Farrukhshah as ruler of the minor emirate of Baalbek and had an unusually long reign for an Ayyubid ruler. Ba ...

(1182–1230), who welcomed a prominent Shia scholar from Homs in the city in 1210s, a gesture that "gave morale to the Shiites living in the nahiyah

A nāḥiyah ( ar, , plural ''nawāḥī'' ), also nahiya or nahia, is a regional or local type of administrative division that usually consists of a number of villages or sometimes smaller towns. In Tajikistan, it is a second-level division w ...

(of Baalbek)". In northern Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, the Shia qadi

A qāḍī ( ar, قاضي, Qāḍī; otherwise transliterated as qazi, cadi, kadi, or kazi) is the magistrate or judge of a '' sharīʿa'' court, who also exercises extrajudicial functions such as mediation, guardianship over orphans and mino ...

of Aleppo Ibn al-Khashshab

Abu'l-Faḍl (Abu'l-Hasan) ibn al-Khashshab ( ar, أبوالفضل (أبوالحسن) بن الخشاب; died 1125) was the Shi'i ''qadi'' and ''rais'' of Aleppo during the rule of the Seljuk emir Radwan.

His family, the Banu'l-Khashshab, were w ...

was one of the first to preach jihad

Jihad (; ar, جهاد, jihād ) is an Arabic word which literally means "striving" or "struggling", especially with a praiseworthy aim. In an Islamic context, it can refer to almost any effort to make personal and social life conform with Go ...

against the crusaders, and personally commanded and lead Aleppian troops in Battle of Ager Sanguinis

In the Battle of ''Ager Sanguinis'', also known as the Battle of the Field of Blood, the Battle of Sarmada, or the Battle of Balat, Roger of Salerno's Crusader army of the Principality of Antioch was annihilated by the army of Ilghazi of Mardin, ...

and Siege of Aleppo.

Most of Jabal Amel regained its autonomy under Husam ad-Din Bechara, a presumably local Shiite officer of Saladin

Yusuf ibn Ayyub ibn Shadi () ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known by the epithet Saladin,, ; ku, سهلاحهدین, ; was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from an ethnic Kurdish family, he was the first of both Egypt and ...

who participated in the Battle of Hattin

The Battle of Hattin took place on 4 July 1187, between the Crusader states of the Levant and the forces of the Ayyubid sultan Saladin. It is also known as the Battle of the Horns of Hattin, due to the shape of the nearby extinct volcano of t ...

and the capture of Jabal Amel and became its lord from 1187 until 1200.

Between 1187 and 1291, the Shiites of Jabal Amel were divided between the newly autonomous hills and a coast still subject to the Franks. Shias from the newly autonomous areas of Jabal Amel soon became essential participants in blocking Frankish

Frankish may refer to:

* Franks, a Germanic tribe and their culture

** Frankish language or its modern descendants, Franconian languages

* Francia, a post-Roman state in France and Germany

* East Francia, the successor state to Francia in Germany ...

raids and sieges. During Saladin

Yusuf ibn Ayyub ibn Shadi () ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known by the epithet Saladin,, ; ku, سهلاحهدین, ; was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from an ethnic Kurdish family, he was the first of both Egypt and ...

's siege of Beaufort castle Beaufort Castle can refer to several places:

* Beaufort Castle, Florennes, Belgium

* Beaufort Castle, France, in the historical region of Auvergne

* Beaufort Castle in Huy, Belgium

* Beaufort Castle, Greece, a Frankish castle in Laconia

* Beaufor ...

, military units from Jabal Amel, likely those of Husam ad-Din Bishara, came to his aid and replaced his forces as he marched to repel a crusader invasion of Acre. Once again in 1195, Husam ad-Din and his forces fought off a Frankish siege of Toron

Toron, now Tibnin or Tebnine in southern Lebanon, was a major Crusader castle, built in the Lebanon mountains on the road from Tyre to Damascus. The castle was the centre of the Lordship of Toron, a seigneury within the Kingdom of Jerusalem ...

.

In 1217, the local archers annihilated a Hungarian contingent attacking Jezzine in 1217. In 1240, the local appointees in Beaufort castle refused the orders of Ayyubid

The Ayyubid dynasty ( ar, الأيوبيون '; ) was the founding dynasty of the medieval Sultan of Egypt, Sultanate of Egypt established by Saladin in 1171, following his abolition of the Fatimid Caliphate, Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt. A Sunni ...

emir Al-Salih Ismail to surrender their castle to crusader forces, leading to their siege and execution.

When the Mongols

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal membe ...

took Baalbek in 1260, many local Shias refused to surrender to Mongol forces. Najmeddine ibn Malli al-Baalbeki (b. 1221), one of Baalbek

Baalbek (; ar, بَعْلَبَكّ, Baʿlabakk, Syriac-Aramaic: ܒܥܠܒܟ) is a city located east of the Litani River in Lebanon's Beqaa Valley, about northeast of Beirut. It is the capital of Baalbek-Hermel Governorate. In Greek and Roman ...

's few Shia scholars at the time, took the initiative and retreated to the slopes of Mount Lebanon

Mount Lebanon ( ar, جَبَل لُبْنَان, ''jabal lubnān'', ; syr, ܛܘܪ ܠܒ݂ܢܢ, ', , ''ṭūr lewnōn'' french: Mont Liban) is a mountain range in Lebanon. It averages above in elevation, with its peak at .

Geography

The Mount Le ...

, where he was joined by thousands of volunteer guerilla

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run tact ...

fighters. According to contemporary chronicler al-Yunini, these guerillas would kidnap and ambush Mongols at night, and would often disguise and adopt pseudonyms to conceal their identities. For example, Najmeddine adopted the pseudonym "the bald king".

Mamluk period and 1305 campaign

By the early 14th century, Jabal Amel was becoming the Twelver Shia center of the Levant. With Shiism losing ground inAleppo

)), is an adjective which means "white-colored mixed with black".

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize =

, map_caption =

, image_map1 =

...

due to Ayyubid

The Ayyubid dynasty ( ar, الأيوبيون '; ) was the founding dynasty of the medieval Sultan of Egypt, Sultanate of Egypt established by Saladin in 1171, following his abolition of the Fatimid Caliphate, Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt. A Sunni ...

and now Mamluk

Mamluk ( ar, مملوك, mamlūk (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural), translated as "one who is owned", meaning " slave", also transliterated as ''Mameluke'', ''mamluq'', ''mamluke'', ''mameluk'', ''mameluke'', ''mamaluke'', or ''marmeluke'') ...

takeover, a stream of scholars shifted to Jabal Amel, and the area probably received migrants from there as it provided refuge from Sunni rigor.

In Muharram

Muḥarram ( ar, ٱلْمُحَرَّم) (fully known as Muharram ul Haram) is the first month of the Islamic calendar. It is one of the four sacred months of the year when warfare is forbidden. It is held to be the second holiest month after R ...

1305, the Mamluk army under the command of Aqqush al-Afram Jamal al-Din Aqqush al-Afram al-Mansuri (died 1336) was a high-ranking Mamluk emir and defector, who served as the Mamluk viceroy of Damascus and later the Ilkhanid governor of Hamadan.

Mamluk emir

Aqqush al-Afram was an ethnic Circassian and beg ...

devastated the mountain-dwelling Shia community of Keserwan. The Mamluks had previously attempted to subjugate the community through several unsuccessful military campaigns in the 1290s, and launched the last campaign after a band of Keserwanis attacked their retreating army after the Battle of Wadi al-Khaznadar. Aqqush led an army of around 50,000 troops which advanced and encircled the Mountain through from four sides, against defending Shiite forces of an estimated 4,000 infantrymen. The region fell after 11 days of brutal fighting, driving an influx of Shiites toward the Beqaa valley

The Beqaa Valley ( ar, links=no, وادي البقاع, ', Lebanese ), also transliterated as Bekaa, Biqâ, and Becaa and known in classical antiquity as Coele-Syria, is a fertile valley in eastern Lebanon. It is Lebanon's most important ...

and Jezzine

Jezzine ( ''Jizzīn'') is a town in Lebanon, located from Sidon and south of Beirut. It is the capital of Jezzine District. Surrounded by mountain peaks, pine forests (like the Bkassine Pine Forest), and at an average altitude of 950 m (3 ...

, while a humbled minority stayed. In 1363, decades later, the Mamluks released an official decree prohibiting Shia rituals practiced among "some of the people of Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

, Sidon

Sidon ( ; he, צִידוֹן, ''Ṣīḏōn'') known locally as Sayda or Saida ( ar, صيدا ''Ṣaydā''), is the third-largest city in Lebanon. It is located in the South Governorate, of which it is the capital, on the Mediterranean coast. ...

and their surrounding villages", threatening punishment and military campaign. The Mamluks punished the town of Machghara

Machghara ( ar, مشغرة), also spelled Mashghara, is a town in the Beqaa Valley of Lebanon, situated in the Western Beqaa District and south of the Beqaa Governorate. It lies just to the northwest of Sohmor and southwest of Lake Qaraoun, south ...

in 1364 for disobedience and religious dissidence. In 1367, the Shias of Burj Beirut rose in armed rebellion against the Mamluks, but the conflict subsided through mediation between the two sides by the Buhturids

The Buhturids, also known as the Banu Buhtur or the Tanukh, were a dynasty whose chiefs served as the emirs (commanders) of the Gharb area southeast of Beirut in Mount Lebanon in the 12th–15th centuries. A branch of the Tanukhid tribal confederat ...

. In 1384, the Mamluks also executed most notable Shia scholar and head of the community at the time, Muhammad Jamaluddin al-Makki al-Amili

Sheikh Abu Abdullah Muhammad Jamal Ad-Deen Al-Makki Al-Amili Al-Jizzeeni (1334–1385), better known as ash-Shahid al-Awwal ( ar, ٱلشَّهِيد ٱلْأَوَّل, ' "The First Martyr") or Shams Ad-Deen (), was a Shi'a scholar and the author o ...

, known as "ash-shahid al-awwal" (the first martyr), on charges of being a ghulat

The ( ar, غلاة, 'exaggerators', 'extremists', 'transgressors', singular ) were a branch of early Shi'i Muslims thus named by other Shi'i and Sunni Muslims for their purportedly 'exaggerated' veneration of the prophet Muhammad (–632) and his ...

and promoting Nusayri

The Alawis, Alawites ( ar, علوية ''Alawīyah''), or pejoratively Nusayris ( ar, نصيرية ''Nuṣayrīyah'') are an ethnoreligious group that lives primarily in Levant and follows Alawism, a sect of Islam that originated from Shia Isla ...

doctrines, falsely claimed by his enemies and former ex-Shia students.

Since 1385 much of Jabal Amel and Safed was ruled by the Bechara family, who occasionally also brought Wadi al-Taym Wadi al-Taym ( ar, وادي التيم, Wādī al-Taym), also transliterated as Wadi el-Taym, is a wadi (dry river) that forms a large fertile valley in Lebanon, in the districts of Rachaya and Hasbaya on the western slopes of Mount Hermon. It ad ...

under their control, until the advent of Ottomans. On the other hand, the Harfush dynasty

The Harfush dynasty (or Harfouche, Harfouch, or most commonly spelled Harfoush dynasty, all varying transcriptions of the same Arabic family name حرفوش) was a dynasty that descended from the Khuza'a tribe, which helped, during the reign of ...

of the Bekaa were first mentioned by Ibn Tawq as muqaddam

( ar, مقدم) is an Arabic title, adopted in other Islamic or Islamicate cultures, for various civil or religious officials.

As per the Persian records of medieval India, muqaddams, along with khots and chowdhurys, acted as hereditary rural i ...

s in the Anti-Lebanon mountains

The Anti-Lebanon Mountains ( ar, جبال لبنان الشرقية, Jibāl Lubnān ash-Sharqiyyah, Eastern Mountains of Lebanon; Lebanese Arabic: , , "Eastern Mountains") are a southwest–northeast-trending mountain range that forms most of th ...

to the east of Baalbek in 1483, and later as deputies (na'ib) of Baalbek. Two members of the two families, Ibn Bechara and Ibn Harfush, reportedly fought on each other's side during civil strife in Damascus between Mamluk governors in 1497. According to contemporary chronicler Ibn Tulun, many Shiites had come to join the battle in aid of one of the Mamluk governors. In the mid-1200s, al-Yunini mentions a few Tanukhid

The Tanûkhids ( ar, التنوخيون, transl=al-Tanūḫiyyūn) or Tanukh ( ar, تنوخ, translit=Tanūḫ) or Banū Tanūkh (, romanized as: ) were a confederation of Arab tribes, sometimes characterized as Saracens. They first rose to prom ...

emirs in Mount Lebanon

Mount Lebanon ( ar, جَبَل لُبْنَان, ''jabal lubnān'', ; syr, ܛܘܪ ܠܒ݂ܢܢ, ', , ''ṭūr lewnōn'' french: Mont Liban) is a mountain range in Lebanon. It averages above in elevation, with its peak at .

Geography

The Mount Le ...

who reportedly followed the Shiite faith, whose domains had also covered Karak Nuh

Karak (also Kerak, Karak Nuh or Karak Noah) ( ar, كرك, Karak) is a village in the municipality of Zahle in the Zahle District of the Beqaa Governorate in eastern Lebanon. It is located on the Baalbek road close to Zahle. Karak contains a sar ...

. Following the disastrous campain in 1305, the Hamada family were among the earliest mentioned families, and reportedly served as tax-collectors in the district of Mamluk Tripoli as early as 1471, in the region Dinniyeh. Bilad Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

were similarly under the jurisdiction of a Shia muqaddam prior to 1407.

Under Ottoman rule

The Levant fell to theOttomans

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

in 1516, bringing about a new period in the region. Often times, Local Shias came into conflict with Ottoman-assigned governors of Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

, Sidon

Sidon ( ; he, צִידוֹן, ''Ṣīḏōn'') known locally as Sayda or Saida ( ar, صيدا ''Ṣaydā''), is the third-largest city in Lebanon. It is located in the South Governorate, of which it is the capital, on the Mediterranean coast. ...

and Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

, who often derogatorily referred to them as Qizilbash

Qizilbash or Kizilbash ( az, Qızılbaş; ota, قزيل باش; fa, قزلباش, Qezelbāš; tr, Kızılbaş, lit=Red head ) were a diverse array of mainly Turkoman Shia militant groups that flourished in Iranian Azerbaijan, Anatolia, the ...

in their documents as a means to delegitimize them or justify punitive campaigns against them. Nevertheless, although considered Heretics

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

by the Ottomans, the latter confirmed tax-collectorship iltizam

An Iltizām (Arabic التزام) was a form of tax farm that appeared in the 15th century in the Ottoman Empire. The system began under Mehmed the Conqueror and was abolished during the Tanzimat reforms in 1856.

Iltizams were sold off by the gove ...

to the local Shia in Jabal Amel

Jabal Amil ( ar, جبل عامل, Jabal ʿĀmil), also spelled Jabal Amel and historically known as Jabal Amila, is a cultural and geographic region in Southern Lebanon largely associated with its long-established, predominantly Twelver Shia Musl ...

, Bekaa valley

The Beqaa Valley ( ar, links=no, وادي البقاع, ', Lebanese ), also transliterated as Bekaa, Biqâ, and Becaa and known in classical antiquity as Coele-Syria, is a fertile valley in eastern Lebanon. It is Lebanon's most important ...

and northern Mount Lebanon

Mount Lebanon ( ar, جَبَل لُبْنَان, ''jabal lubnān'', ; syr, ܛܘܪ ܠܒ݂ܢܢ, ', , ''ṭūr lewnōn'' french: Mont Liban) is a mountain range in Lebanon. It averages above in elevation, with its peak at .

Geography

The Mount Le ...

as part of their efforts of relying on local intermediaries rather than forcibly imposing foreign ones. The Harfush and Hamade families received iltizam over the Bekaa valley

The Beqaa Valley ( ar, links=no, وادي البقاع, ', Lebanese ), also transliterated as Bekaa, Biqâ, and Becaa and known in classical antiquity as Coele-Syria, is a fertile valley in eastern Lebanon. It is Lebanon's most important ...

and northern Mount Lebanon respectively, while Jabal Amel consisted of several nawahi governed by multiple families, until Ali al-Saghirs seized most of Jabal Amel by 1649.

These feudal families were often autonomous and frequently quarrelled with the Ottoman governors to maintain autonomy over their territories, often with mixed results. Comte de Volney

''Comte'' is the French, Catalan and Occitan form of the word 'count' (Latin: ''comes''); ''comté'' is the Gallo-Romance form of the word 'county' (Latin: ''comitatus'').

Comte or Comté may refer to:

* A count in French, from Latin ''comes''

* A ...

, who visited Lebanon between 1783 and 1785, noted this.

"The ''Metoualis'' are almost annihilated due to their revolts; their name is soon to be extinct".

The three Shia principalities underwent different historical trajectories. The Harfush initially did not challenge the new Ottoman authority, but in 1518 the Ottomans executed an anonymous Ibn Harfush, governor of Baalbek, along with the Bedouin Emir Ibn al-Hanash for acting against the state. At their high-point, Harfush domains extended from the Beqaa valley into

The three Shia principalities underwent different historical trajectories. The Harfush initially did not challenge the new Ottoman authority, but in 1518 the Ottomans executed an anonymous Ibn Harfush, governor of Baalbek, along with the Bedouin Emir Ibn al-Hanash for acting against the state. At their high-point, Harfush domains extended from the Beqaa valley into Palmyra

Palmyra (; Palmyrene: () ''Tadmor''; ar, تَدْمُر ''Tadmur'') is an ancient city in present-day Homs Governorate, Syria. Archaeological finds date back to the Neolithic period, and documents first mention the city in the early second ...

far in the Syrian Desert

The Syrian Desert ( ar, بادية الشام ''Bādiyat Ash-Shām''), also known as the North Arabian Desert, the Jordanian steppe, or the Badiya, is a region of desert, semi-desert and steppe covering of the Middle East, including parts of sou ...

and sanjak of Homs

The Homs Sanjak ( tr, Homs Sancağı) was a prefecture (sanjak) of the Ottoman Empire, located in modern-day Syria. The city of Homs was the Sanjak's capital. It had a population of 200,410 in 1914. The Sanjak of Homs shared same region with Sanja ...

in 1568 during Musa Harfush's reign, who was even assigned a unit of 1,000 archers to lead int the Yemen campaign. In 1616, Yunus al-Harfush again asserted Harfush supremacy over Homs and the Bekaa, defeating his Sayfa opponents in battle, and earning iltizam for the Sanjak of Homs. Prior the Battle of Ain Dara

The Battle of Ain Dara took place in the town of Ain Dara in 1711 between the Qaysi and Yamani tribo-political factions. The Qays were led by Emir Haydar of the Shihab dynasty and consisted of the Druze clans of Jumblatt, Talhuq, Imad and Abd a ...

, Haydar Shihab took refuge among the Harfushes, who provided him with 2,500 troops to carry out the battle, which resulted in Shihab's decisive victory.

Further South, the pinnacle of Jabal Amel was at the hands of Nassif al-Nassar (c. 1749–1781) of Ali al-Saghirs during his alliance with Zahir al-Umar

Zahir al-Umar al-Zaydani, alternatively spelled Daher al-Omar or Dahir al-Umar ( ar, ظاهر العمر الزيداني, translit=Ẓāhir al-ʿUmar az-Zaydānī, 1689/90 – 21 or 22 August 1775) was the autonomous Arab ruler of northern Ottom ...

. In 1767, the latter attempted to extend his authority to Shiite villages, but was defeated in battle and captured, eventually entering into an alliance with Nassif and the Shiites. The duo's first decisive battle took place in Lake Huleh in 1771, when the 10,000-strong Ottoman army of Uthman Pasha al-Kurji was virtually annihilated by the duo's forces; about 300-500 Ottoman soldiers survived the battle, and Uthman Pasha returned to Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

with only 3 of his soldiers. Through his 10,000-strong cavalry army, specially noted by a French consul as "excellent fighters", Nassif imposed control on all territories between Sidon

Sidon ( ; he, צִידוֹן, ''Ṣīḏōn'') known locally as Sayda or Saida ( ar, صيدا ''Ṣaydā''), is the third-largest city in Lebanon. It is located in the South Governorate, of which it is the capital, on the Mediterranean coast. ...

and Safed, notwithstanding Zahir's territories within Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

and western Transjordan Transjordan may refer to:

* Transjordan (region), an area to the east of the Jordan River

* Oultrejordain, a Crusader lordship (1118–1187), also called Transjordan

* Emirate of Transjordan, British protectorate (1921–1946)

* Hashemite Kingdom of ...

which Nassif's cavalry forces had an integral part in capturing. Zahir's military potential was significantly boosted by the backing of 10,000 Shiite fighters, who supported him against the sieges and assaults by the overnors of Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

, reportedly participating in fifteen subsequent campaigns against his foes. Thus, Nassif and his allies managed to impose ''grande sécurité'' on the whole region, so much so that Ali Bey al-Kabir of Egypt requested Nassif's help to put down the rebellion at Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metro ...

in 1773, and was sought by nomadic tribes in the Syro-Jordanian desert to help them against their foes.

The Hamada's of northern Mount Lebanon

Mount Lebanon ( ar, جَبَل لُبْنَان, ''jabal lubnān'', ; syr, ܛܘܪ ܠܒ݂ܢܢ, ', , ''ṭūr lewnōn'' french: Mont Liban) is a mountain range in Lebanon. It averages above in elevation, with its peak at .

Geography

The Mount Le ...

, spearheading a rather much smaller community, were virtually in a continuous state of conflict with the Ottomans between 1685 and 1711. In 1686, a joint Harfush-Hamade force managed to defeat and drive the forces of the Ottoman governors of Sidon and Tripoli out of Keserwan, leaving Tripoli susceptible to attack. As a result, they managed to re-affirm themselves as multezims for most of northern Lebanon and parts of Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

as far as Safita

Safita ( ar, صَافِيتَا '; phn, 𐤎𐤐𐤕𐤄, ''Sōpūte'') is a city in the Tartous Governorate, northwestern Syria, located to the southeast of Tartous and to the northwest of Krak des Chevaliers. It is situated on the tops ...

and Krak des Chevaliers

Krak des Chevaliers, ar, قلعة الحصن, Qalʿat al-Ḥiṣn also called Hisn al-Akrad ( ar, حصن الأكراد, Ḥiṣn al-Akrād, rtl=yes, ) and formerly Crac de l'Ospital; Krak des Chevaliers or Crac des Chevaliers (), is a medieva ...

. Upon meeting them in 1686, a French diplomat came acqainted with them as the "men of emir Sirhan", describing them as good hearted people and "iron men" who would not back out to the strongest of janissaries. By 1771, the Hamada's and the Shia community were greatly weakened by the Ottoman governors and Shihabis, and eventually completely fell out of grace, diminishing their political importance in Mount Lebanon. As a result, a second population influx overran the Beqaa valley where the Harfushes welcomed the displaced Shiites, and allotted them land in Hermel

Hermel ( ar, الهرمل) is a town in Baalbek-Hermel Governorate, Lebanon. It is the capital of Hermel District. Hermel is home to a Lebanese Red Cross First Aid Center. Hermel's inhabitants are predominantly Shia Muslims.

There is an ancient ...

and other places.

In 1781, Shia autonomy diminished under

In 1781, Shia autonomy diminished under Ahmad Pasha al-Jazzar

Ahmad Pasha al-Jazzar ( ar, أحمد باشا الجزّار; ota, جزّار أحمد پاشا; ca. 1720–30s7 May 1804) was the Acre-based Ottoman governor of Sidon Eyalet from 1776 until his death in 1804 and the simultaneous governor of D ...

(1776–1804), nicknamed the butcher. Al-Jazzar was initially on good terms with Nassif, but their alliance reached a bad point some time in 1781. Afterward, al-Jazzar defeated and killed Nassif and 470 of his men in battle, proceeding to conquer Shia-held fortress towns and eliminate all the leading Shia sheikhs of Jabal Amel, whose families were allowed to take refuge with the Harfushes in Baalbek. He proceeded to burn down Shia religious libraries, transport Shia religious books to the ovens in Acre, and paraded the heads of the fallen in Sidon

Sidon ( ; he, צִידוֹן, ''Ṣīḏōn'') known locally as Sayda or Saida ( ar, صيدا ''Ṣaydā''), is the third-largest city in Lebanon. It is located in the South Governorate, of which it is the capital, on the Mediterranean coast. ...

. Following their crisis, insurgency commenced at the hands of local militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

s which attacked al-Jazzar's troops in the region. The period witnessed swift uprisings in Chehour

Chehoûr, Shuhur, or Shhur (Arabic language, Arabic: شحور), is a small town on the Litani River in the Tyre District of Southern Lebanon's South Governorate, some 95 kilometres to the south-west of Beirut, the capital city of Lebanon.

Name

Ed ...

in 1784 and Tyre in 1785, and the insurgents managed to temporarily conquer the citadel of Tebnine. Insurgency continued until the end of al-Jazzar's rule in 1804, and famously involved Faris al-Nassif, Nassif al-Nassar's son.

The period between 1781 and 1804 was marked as a period of decline and political defeat among the Shias of Jabal Amel, and persisted in their collective memory well into the early 20th century. Political involvement of Shiites of Jabal Amel recommenced upon the Egyptian invasion of the Levant in 1833, when Shiites resented the Shihabi-Egyptian alliance and assumed a central role in the efforts of expelling the Egyptians from Ottoman Syria. Led by Khanjar Harfush in Baalbek

Baalbek (; ar, بَعْلَبَكّ, Baʿlabakk, Syriac-Aramaic: ܒܥܠܒܟ) is a city located east of the Litani River in Lebanon's Beqaa Valley, about northeast of Beirut. It is the capital of Baalbek-Hermel Governorate. In Greek and Roman ...

, and in Jabal Amel

Jabal Amil ( ar, جبل عامل, Jabal ʿĀmil), also spelled Jabal Amel and historically known as Jabal Amila, is a cultural and geographic region in Southern Lebanon largely associated with its long-established, predominantly Twelver Shia Musl ...

by Hasan al-Shabib and Hamad al-Beik, the Shiites engaged in various battles against the Egyptian army. Khanjar Harfush engaged an Egyptian force of 12,000 in Nabek and Keserwan and was joined by Maronite

The Maronites ( ar, الموارنة; syr, ܡܖ̈ܘܢܝܐ) are a Christian ethnoreligious group native to the Eastern Mediterranean and Levant region of the Middle East, whose members traditionally belong to the Maronite Church, with the larges ...

peasants in Zouk Mikael

Zouk Mikael ( ar, زوق مكايل, also spelled Zuq Mikha'il or Zouk Mkayel) is a town and municipality in the Keserwan District of the Keserwan-Jbeil Governorate in Lebanon. Its inhabitants are predominantly Melkite and Maronite Catholics.

The ...

, while Hamad Beik singlehandedly drove out the Egyptians as far as Safed in northern Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

. In 1841, during a period of brutal Christian-Druze fighting prior the 1860 civil war, the Harfushes gathered forces and came to the aid of Zahle, defeating the Druze

The Druze (; ar, دَرْزِيٌّ, ' or ', , ') are an Arabic-speaking esoteric ethnoreligious group from Western Asia who adhere to the Druze faith, an Abrahamic, monotheistic, syncretic, and ethnic religion based on the teachings of ...

forces besieging the city. The Harfush were eventually deported to Edirne

Edirne (, ), formerly known as Adrianople or Hadrianopolis (Greek: Άδριανούπολις), is a city in Turkey, in the northwestern part of the province of Edirne in Eastern Thrace. Situated from the Greek and from the Bulgarian borders, ...

in 1865 at the behest of Ottoman authority.

During World War I

Between 1914 and 1918, manyArab nationalists

Arab nationalism ( ar, القومية العربية, al-Qawmīya al-ʿArabīya) is a nationalist ideology that asserts the Arabs are a nation and promotes the unity of Arab people, celebrating the glories of Arab civilization, the language and ...

from Lebanon and Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

were arrested by Ottoman authorities and trialed, and some were executed. Two Shiites were among those executed in between August 1915 and May 1916: Abdul-Kareem Khalil from Chyah

Chiyah () is situated in the west region of the Lebanese capital of Beirut and is part of Greater Beirut.

Location

Chiyah is located in the southwest suburbs of the capital Beirut, bordered by Haret Hreik, Ghobeiry, Hadath, Hazmiyeh, Furn-el- ...

and Saleh Haidar from Baalbek

Baalbek (; ar, بَعْلَبَكّ, Baʿlabakk, Syriac-Aramaic: ܒܥܠܒܟ) is a city located east of the Litani River in Lebanon's Beqaa Valley, about northeast of Beirut. It is the capital of Baalbek-Hermel Governorate. In Greek and Roman ...

. The day is commemorated in Lebanon and Syria as Martyrs' Day Martyrs' Day is an annual day observed by nations to salute the martyrdom of soldiers who lost their lives defending the sovereignty of the nation. The actual date may vary from one country to another. Here is a list of countries and Martyrs' Days.

...

. Several others were arrested and imprisoned, including Muhammad Jaber Safa, Sheikh Ahmad Rida

Sheikh Ahmad Rida (also transliterated as Ahmad Reda) (1872–1953) ( ar, الشيخ أحمد رضا) was a Lebanese linguist, writer and politician. A key figure of the Arab Renaissance (known as al-Nahda), he compiled the modern monolingual Ar ...

and Ahmed Aref El-Zein

Sheikh Ahmed Aref El-Zein (10 July 1884 – 13 October 1960) (Arabic: ) was a Shi'a intellectual from the Jabal Amil (جبل عامل) area of South Lebanon. He was a reformist scholar who engaged in the modernist intellectual debates that reso ...

, the latter who participated in several underground Arab societies, and supported the Arab Congress of 1913

The Arab Congress of 1913 (also known as the "Arab National Congress," "First Palestinian Conference," the "First Arab Congress," and the "Arab-Syrian Congress") met in a hall of the French Geographical Society ( Société de Géographie) at 184 B ...

.

Relations with Iranian Shias

During most of the Ottoman period, the Shia largely maintained themselves as 'a state apart'. Towards the end of the eighteenth century the Comte de Volmy described Lebanese Shia as a distinct society. When the Safavids began converting Iran to Shiism by coercion and persuasion, they compensated the lack of established Shia fiqh in Iran by asking Shia clergies fromJabal Amel

Jabal Amil ( ar, جبل عامل, Jabal ʿĀmil), also spelled Jabal Amel and historically known as Jabal Amila, is a cultural and geographic region in Southern Lebanon largely associated with its long-established, predominantly Twelver Shia Musl ...

, Bahrain

Bahrain ( ; ; ar, البحرين, al-Bahrayn, locally ), officially the Kingdom of Bahrain, ' is an island country in Western Asia. It is situated on the Persian Gulf, and comprises a small archipelago made up of 50 natural islands and an ...

and Al-Ahsa to immigrate to Iran. Chief among them was Muhaqqiq al-Karaki, from Karak Nuh

Karak (also Kerak, Karak Nuh or Karak Noah) ( ar, كرك, Karak) is a village in the municipality of Zahle in the Zahle District of the Beqaa Governorate in eastern Lebanon. It is located on the Baalbek road close to Zahle. Karak contains a sar ...

in the Bekaa valley, who achieved limitless power during the reign of Shah Tahmasp I

Tahmasp I ( fa, طهماسب, translit=Ṭahmāsb or ; 22 February 1514 – 14 May 1576) was the second shah of Safavid Iran from 1524 to 1576. He was the eldest son of Ismail I and his principal consort, Tajlu Khanum. Ascending the throne after t ...

such that the Shah told him, “''You are the real king and I am just one of your agents''". These contacts greatly angered the Ottomans. In addition to their different narrative of Islam, the Ottomans suspected Shias of being a stalking horse for the Safavids, and often derogatorily referred to them as Qizilbash

Qizilbash or Kizilbash ( az, Qızılbaş; ota, قزيل باش; fa, قزلباش, Qezelbāš; tr, Kızılbaş, lit=Red head ) were a diverse array of mainly Turkoman Shia militant groups that flourished in Iranian Azerbaijan, Anatolia, the ...

. Thus, the Shia oppression in Lebanon was a marriage of politics and religion.

During the 19th century, the Maronites

The Maronites ( ar, الموارنة; syr, ܡܖ̈ܘܢܝܐ) are a Christian ethnoreligious group native to the Eastern Mediterranean and Levant region of the Middle East, whose members traditionally belong to the Maronite Church, with the largest ...

were supported by the France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, the Druze

The Druze (; ar, دَرْزِيٌّ, ' or ', , ') are an Arabic-speaking esoteric ethnoreligious group from Western Asia who adhere to the Druze faith, an Abrahamic, monotheistic, syncretic, and ethnic religion based on the teachings of ...

by the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

, the Greek Orthodox

The term Greek Orthodox Church (Greek language, Greek: Ἑλληνορθόδοξη Ἐκκλησία, ''Ellinorthódoxi Ekklisía'', ) has two meanings. The broader meaning designates "the Eastern Orthodox Church, entire body of Orthodox (Chalced ...

by the Russians

, native_name_lang = ru

, image =

, caption =

, population =

, popplace =

118 million Russians in the Russian Federation (2002 ''Winkler Prins'' estimate)

, region1 =

, pop1 ...

and the Sunnis