Akhilleus Aias Staatliche Antikensammlungen 1417 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

In

Some researchers deem the name a

Some researchers deem the name a

Achilles was the son of

Achilles was the son of  According to the ''

According to the '' In the few fragmentary poems of the

In the few fragmentary poems of the

Some post-Homeric sources claim that in order to keep Achilles safe from the war, Thetis (or, in some versions, Peleus) hid the young man dressed as a princess or at least a girl at the court of

Some post-Homeric sources claim that in order to keep Achilles safe from the war, Thetis (or, in some versions, Peleus) hid the young man dressed as a princess or at least a girl at the court of

According to the ''Iliad'', Achilles arrived at Troy with 50 ships, each carrying 50

According to the ''Iliad'', Achilles arrived at Troy with 50 ships, each carrying 50

According to the ''

According to the ''

The Trojans, led by

The Trojans, led by

The '' Aethiopis'' (7th century BC) and a work named ''

The '' Aethiopis'' (7th century BC) and a work named ''

The death of Achilles, even if considered solely as it occurred in the oldest sources, is a complex one, with many different versions. Starting with the oldest account, In the ''Iliad Book XXII'',

The death of Achilles, even if considered solely as it occurred in the oldest sources, is a complex one, with many different versions. Starting with the oldest account, In the ''Iliad Book XXII'',  In the ''

In the ''

Achilles' armour was the object of a feud between Odysseus and

Achilles' armour was the object of a feud between Odysseus and

The tomb of Achilles, extant throughout antiquity in

The tomb of Achilles, extant throughout antiquity in

File:Achilles departure Eretria Painter CdM Paris 851.jpg, Achilles and the

online

. * * Dale S. Sinos (1991), ''The Entry of Achilles into Greek Epic'', PhD thesis, Johns Hopkins University. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University Microfilms International. * Jonathan S. Burgess (2009), ''The Death and Afterlife of Achilles''. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. * Abrantes, M.C. (2016), ''Themes of the Trojan Cycle: Contribution to the study of the greek mythological tradition'' (Coimbra).

* Poem by Florence Earle Coates {{DEFAULTSORT:Achilles Greek mythological heroes Kings of the Myrmidons Achaean Leaders Thessalians in the Trojan War Metamorphoses characters Mythological rapists Demigods in classical mythology LGBT themes in Greek mythology Deeds of Apollo Medea Fictional LGBT characters in literature

In

In Greek mythology

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the origin and nature of the world, the lives and activities o ...

, Achilles ( ) or Achilleus ( grc-gre, Ἀχιλλεύς

In Greek mythology, Achilles ( ) or Achilleus ( grc-gre, Ἀχιλλεύς) was a hero of the Trojan War, the greatest of all the Greek warriors, and the central character of Homer's ''Iliad''. He was the son of the Nereid Thetis and Peleus, ...

) was a hero of the Trojan War

In Greek mythology, the Trojan War was waged against the city of Troy by the Achaeans ( Greeks) after Paris of Troy took Helen from her husband Menelaus, king of Sparta. The war is one of the most important events in Greek mythology and ...

, the greatest of all the Greek warriors, and the central character of Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

's ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Ody ...

''. He was the son of the Nereid

In Greek mythology, the Nereids or Nereides ( ; grc, Νηρηΐδες, Nērēḯdes; , also Νημερτές) are sea nymphs (female spirits of sea waters), the 50 daughters of the ' Old Man of the Sea' Nereus and the Oceanid Doris, sisters ...

Thetis

Thetis (; grc-gre, Θέτις ), is a figure from Greek mythology with varying mythological roles. She mainly appears as a sea nymph, a goddess of water, or one of the 50 Nereids, daughters of the ancient sea god Nereus.

When described as ...

and Peleus

In Greek mythology, Peleus (; Ancient Greek: Πηλεύς ''Pēleus'') was a hero, king of Phthia, husband of Thetis and the father of their son Achilles. This myth was already known to the hearers of Homer in the late 8th century BC.

Bi ...

, king of Phthia

In Greek mythology Phthia (; grc-gre, Φθία or Φθίη ''Phthía, Phthíē'') was a city or district in ancient Thessaly. It is frequently mentioned in Homer's ''Iliad'' as the home of the Myrmidones, the contingent led by Achilles in the ...

.

Achilles' most notable feat during the Trojan War was the slaying of the Trojan prince Hector

In Greek mythology, Hector (; grc, Ἕκτωρ, Hektōr, label=none, ) is a character in Homer's Iliad. He was a Trojan prince and the greatest warrior for Troy during the Trojan War. Hector led the Trojans and their allies in the defense o ...

outside the gates of Troy

Troy ( el, Τροία and Latin: Troia, Hittite: 𒋫𒊒𒄿𒊭 ''Truwiša'') or Ilion ( el, Ίλιον and Latin: Ilium, Hittite: 𒃾𒇻𒊭 ''Wiluša'') was an ancient city located at Hisarlik in present-day Turkey, south-west of Ç ...

. Although the death of Achilles is not presented in the ''Iliad'', other sources concur that he was killed near the end of the Trojan War by Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

, who shot him with an arrow. Later legends (beginning with Statius

Publius Papinius Statius ( Greek: Πόπλιος Παπίνιος Στάτιος; ; ) was a Greco-Roman poet of the 1st century CE. His surviving Latin poetry includes an epic in twelve books, the ''Thebaid''; a collection of occasional poetry, ...

' unfinished epic ''Achilleid

The ''Achilleid'' ( la, Achilleis) is an unfinished epic poem by Publius Papinius Statius that was intended to present the life of Achilles from his youth to his death at Troy. Only about one and a half books (1,127 dactylic hexameters) were co ...

'', written in the 1st century AD) state that Achilles was invulnerable in all of his body except for one heel, because when his mother Thetis dipped him in the river Styx

In Greek mythology, Styx (; grc, Στύξ ) is a river that forms the boundary between Earth (Gaia) and the Underworld. The rivers Acheron, Cocytus, Lethe, Phlegethon, and Styx all converge at the centre of the underworld on a great marsh, ...

as an infant, she held him by one of his heels. Alluding to these legends, the term "Achilles' heel

An Achilles' heel (or Achilles heel) is a weakness in spite of overall strength, which can lead to downfall. While the mythological origin refers to a physical vulnerability, idiomatic references to other attributes or qualities that can lead to ...

" has come to mean a point of weakness, especially in someone or something with an otherwise strong constitution. The Achilles tendon

The Achilles tendon or heel cord, also known as the calcaneal tendon, is a tendon at the back of the lower leg, and is the thickest in the human body. It serves to attach the plantaris, gastrocnemius (calf) and soleus muscles to the calcaneus ...

is also named after him due to these legends.

Etymology

Linear B

Linear B was a syllabic script used for writing in Mycenaean Greek, the earliest attested form of Greek. The script predates the Greek alphabet by several centuries. The oldest Mycenaean writing dates to about 1400 BC. It is descended from ...

tablets attest to the personal name ''Achilleus'' in the forms ''a-ki-re-u'' and ''a-ki-re-we'', Retrieved 5 May 2017. the latter being the dative

In grammar, the dative case ( abbreviated , or sometimes when it is a core argument) is a grammatical case used in some languages to indicate the recipient or beneficiary of an action, as in "Maria Jacobo potum dedit", Latin for "Maria gave Jacob ...

of the former. The name grew more popular, becoming common soon after the seventh century BC and was also turned into the female form Ἀχιλλεία (''Achilleía''), attested in Attica

Attica ( el, Αττική, Ancient Greek ''Attikḗ'' or , or ), or the Attic Peninsula, is a historical region that encompasses the city of Athens, the capital of Greece and its countryside. It is a peninsula projecting into the Aegean ...

in the fourth century BC ( IG II² 1617) and, in the form ''Achillia'', on a stele in Halicarnassus as the name of a female gladiator fighting an "Amazon".

Achilles' name can be analyzed as a combination of (') "distress, pain, sorrow, grief" and (') "people, soldiers, nation", resulting in a proto-form ''*Akhí-lāu̯os'' "he who has the people distressed" or "he whose people have distress". The grief or distress of the people is a theme raised numerous times in the ''Iliad'' (and frequently by Achilles himself). Achilles' role as the hero of grief or distress forms an ironic juxtaposition with the conventional view of him as the hero of ' ("glory", usually in war). Furthermore, ''laós'' has been construed by Gregory Nagy

Gregory Nagy ( hu, Nagy Gergely, ; born October 22, 1942 in Budapest)"CV: Gregory Nagy"

''gr ...

, following ''gr ...

Leonard Palmer

Leonard Robert Palmer (5 June 1906, Bristol – 26 August 1984, Pitney, Somerset) was author and Professor of Comparative Philology at the University of Oxford from 1952 to 1971. He was also a Fellow of Worcester College, Oxford. Palmer made som ...

, to mean "a corps of soldiers", a muster. With this derivation, the name obtains a double meaning in the poem: when the hero is functioning rightly, his men bring distress to the enemy, but when wrongly, his men get the grief of war. The poem is in part about the misdirection of anger on the part of leadership.

Some researchers deem the name a

Some researchers deem the name a loan word

A loanword (also loan word or loan-word) is a word at least partly assimilated from one language (the donor language) into another language. This is in contrast to cognates, which are words in two or more languages that are similar because the ...

, possibly from a Pre-Greek language. Achilles' descent from the Nereid

In Greek mythology, the Nereids or Nereides ( ; grc, Νηρηΐδες, Nērēḯdes; , also Νημερτές) are sea nymphs (female spirits of sea waters), the 50 daughters of the ' Old Man of the Sea' Nereus and the Oceanid Doris, sisters ...

Thetis

Thetis (; grc-gre, Θέτις ), is a figure from Greek mythology with varying mythological roles. She mainly appears as a sea nymph, a goddess of water, or one of the 50 Nereids, daughters of the ancient sea god Nereus.

When described as ...

and a similarity of his name with those of river deities

A water deity is a deity in mythology associated with water or various bodies of water. Water deities are common in mythology and were usually more important among civilizations in which the sea or ocean, or a great river was more important. Anoth ...

such as Acheron

The Acheron (; grc, Ἀχέρων ''Acheron'' or Ἀχερούσιος ''Acherousios''; ell, Αχέροντας ''Acherontas'') is a river located in the Epirus region of northwest Greece. It is long, and its drainage area is . Its source is ...

and Achelous

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, Achelous (also Acheloos or Acheloios) (; Ancient Greek: Ἀχελώϊος, and later , ''Akhelôios'') was the god associated with the Achelous River, the largest river in Greece. According to Hesiod, he ...

have led to speculations about his being an old water divinity . Robert S. P. Beekes has suggested a Pre-Greek origin of the name, based among other things on the coexistence of ''-λλ-'' and ''-λ-'' in epic language, which may account for a palatalized phoneme /ly/ in the original language.Robert S. P. Beekes, ''Etymological Dictionary of Greek'', Brill, 2009, pp. 183ff.

Description

In the account of Dares the Phrygian, Achilles was described having ". . .a large chest, a fine mouth, and powerfully formed arms and legs. His head was covered with long wavy chestnut-colored hair. Though mild in manner, he was very fierce in battle. His face showed the joy of a man richly endowed."Birth and early years

Achilles was the son of

Achilles was the son of Thetis

Thetis (; grc-gre, Θέτις ), is a figure from Greek mythology with varying mythological roles. She mainly appears as a sea nymph, a goddess of water, or one of the 50 Nereids, daughters of the ancient sea god Nereus.

When described as ...

, a Nereid

In Greek mythology, the Nereids or Nereides ( ; grc, Νηρηΐδες, Nērēḯdes; , also Νημερτές) are sea nymphs (female spirits of sea waters), the 50 daughters of the ' Old Man of the Sea' Nereus and the Oceanid Doris, sisters ...

and daughter of The Old Man of the Sea In Greek mythology, the Old Man of the Sea ( grc-gre, ἅλιος γέρων, hálios gérōn; grc-gre, Γέροντας της Θάλασσας, Gérontas tēs Thálassas) was a primordial figure who could be identified as any of several water-god ...

, and Peleus

In Greek mythology, Peleus (; Ancient Greek: Πηλεύς ''Pēleus'') was a hero, king of Phthia, husband of Thetis and the father of their son Achilles. This myth was already known to the hearers of Homer in the late 8th century BC.

Bi ...

, the king of the Myrmidons

In Greek mythology, the Myrmidons (or Myrmidones; el, Μυρμιδόνες) were an ancient Thessalian Greek tribe. In Homer's ''Iliad'', the Myrmidons are the soldiers commanded by Achilles. Their eponymous ancestor was Myrmidon, a king of ...

. Zeus

Zeus or , , ; grc, Δῐός, ''Diós'', label= genitive Boeotian Aeolic and Laconian grc-dor, Δεύς, Deús ; grc, Δέος, ''Déos'', label= genitive el, Δίας, ''Días'' () is the sky and thunder god in ancient Greek relig ...

and Poseidon

Poseidon (; grc-gre, Ποσειδῶν) was one of the Twelve Olympians in ancient Greek religion and myth, god of the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses.Burkert 1985pp. 136–139 In pre-Olympian Bronze Age Greece, he was venerated as ...

had been rivals for Thetis's hand in marriage until Prometheus

In Greek mythology, Prometheus (; , , possibly meaning " forethought")Smith"Prometheus". is a Titan god of fire. Prometheus is best known for defying the gods by stealing fire from them and giving it to humanity in the form of technology, kn ...

, the fore-thinker, warned Zeus of a prophecy (originally uttered by Themis

In Greek mythology and religion, Themis (; grc, Θέμις, Themis, justice, law, custom) is one of the twelve Titan children of Gaia and Uranus, and the second wife of Zeus. She is the goddess and personification of justice, divine order, fai ...

, goddess of divine law) that Thetis would bear a son greater than his father. For this reason, the two gods withdrew their pursuit, and had her wed Peleus.

There is a tale which offers an alternative version of these events: In the ''Argonautica

The ''Argonautica'' ( el, Ἀργοναυτικά , translit=Argonautika) is a Greek epic poem written by Apollonius Rhodius in the 3rd century BC. The only surviving Hellenistic epic, the ''Argonautica'' tells the myth of the voyage of Jas ...

'' (4.760) Zeus' sister and wife Hera

In ancient Greek religion, Hera (; grc-gre, Ἥρα, Hḗrā; grc, Ἥρη, Hḗrē, label=none in Ionic and Homeric Greek) is the goddess of marriage, women and family, and the protector of women during childbirth. In Greek mythology, she ...

alludes to Thetis' chaste resistance to the advances of Zeus, pointing out that Thetis was so loyal to Hera's marriage bond that she coolly rejected the father of gods. Thetis, although a daughter of the sea-god Nereus

In Greek mythology, Nereus ( ; ) was the eldest son of Pontus (the Sea) and Gaia ( the Earth), with Pontus himself being a son of Gaia. Nereus and Doris became the parents of 50 daughters (the Nereids) and a son ( Nerites), with whom Nereus ...

, was also brought up by Hera, further explaining her resistance to the advances of Zeus. Zeus was furious and decreed that she would never marry an immortal.

According to the ''

According to the ''Achilleid

The ''Achilleid'' ( la, Achilleis) is an unfinished epic poem by Publius Papinius Statius that was intended to present the life of Achilles from his youth to his death at Troy. Only about one and a half books (1,127 dactylic hexameters) were co ...

'', written by Statius

Publius Papinius Statius ( Greek: Πόπλιος Παπίνιος Στάτιος; ; ) was a Greco-Roman poet of the 1st century CE. His surviving Latin poetry includes an epic in twelve books, the ''Thebaid''; a collection of occasional poetry, ...

in the 1st century AD, and to non-surviving previous sources, when Achilles was born Thetis tried to make him immortal by dipping him in the river Styx

In Greek mythology, Styx (; grc, Στύξ ) is a river that forms the boundary between Earth (Gaia) and the Underworld. The rivers Acheron, Cocytus, Lethe, Phlegethon, and Styx all converge at the centre of the underworld on a great marsh, ...

; however, he was left vulnerable at the part of the body by which she held him: his left heel . It is not clear if this version of events was known earlier. In another version of this story, Thetis anointed the boy in ambrosia

In the ancient Greek myths, ''ambrosia'' (, grc, ἀμβροσία 'immortality'), the food or drink of the Greek gods, is often depicted as conferring longevity or immortality upon whoever consumed it. It was brought to the gods in Olympus ...

and put him on top of a fire in order to burn away the mortal parts of his body. She was interrupted by Peleus and abandoned both father and son in a rage.

None of the sources before Statius make any reference to this general invulnerability. To the contrary, in the ''Iliad'', Homer mentions Achilles being wounded: in Book 21 the Paeonian

In antiquity, Paeonia or Paionia ( grc, Παιονία, Paionía) was the land and kingdom of the Paeonians or Paionians ( grc, Παίονες, Paíones).

The exact original boundaries of Paeonia, like the early history of its inhabitants, a ...

hero Asteropaeus

In the ''Iliad'', Asteropaios (; Greek: Ἀστεροπαῖος; Latin: ''Asteropaeus'') was a leader of the Trojan-allied Paeonians along with fellow warrior Pyraechmes.

Family

Asteropaios was the son of Pelagon, who was the son of the rive ...

, son of Pelagon, challenged Achilles by the river Scamander

Scamander (; also Skamandros ( grc, Σκάμανδρος) or Xanthos () was a river god in Greek mythology.

Etymology

The meaning of this name is uncertain. The second element looks like it is derived from Greek () meaning 'of a man', but t ...

. He was ambidextrous, and cast a spear from each hand; one grazed Achilles' elbow, "drawing a spurt of blood".

In the few fragmentary poems of the

In the few fragmentary poems of the Epic Cycle

The Epic Cycle ( grc, Ἐπικὸς Κύκλος, Epikòs Kýklos) was a collection of Ancient Greek epic poems, composed in dactylic hexameter and related to the story of the Trojan War, including the '' Cypria'', the ''Aethiopis'', the so-ca ...

which describe the hero's death (i.e. the ''Cypria

The ''Cypria'' (; grc-gre, Κύπρια ''Kúpria''; Latin: ''Cypria'') is a lost epic poem of ancient Greek literature, which has been attributed to Stasinus and was quite well known in classical antiquity and fixed in a received text, but which ...

'', the '' Little Iliad'' by Lesches of Pyrrha, the ''Aithiopis

The ''Aethiopis'' , also spelled ''Aithiopis'' ( Greek: , ''Aíthiopís''; la, Aethiopis), is a lost epic of ancient Greek literature. It was one of the Epic Cycle, that is, the Trojan cycle, which told the entire history of the Trojan War ...

'' and ''Iliou persis

The ''Iliupersis'' (Greek: , ''Iliou persis'', "Sack of Ilium"), also known as ''The Sack of Troy'', is a lost epic of ancient Greek literature. It was one of the Epic Cycle, that is, the Trojan cycle, which told the entire history of the Troj ...

'' by Arctinus of Miletus

Arctinus of Miletus or Arctinus Milesius ( grc, Ἀρκτῖνος Μιλήσιος) was a Greek epic poet whose reputation is purely legendary, as none of his works survive. Traditionally dated between 775 BC and 741 BC, he was said to have been ...

), there is no trace of any reference to his general invulnerability or his famous weakness at the heel. In the later vase paintings presenting the death of Achilles, the arrow (or in many cases, arrows) hit his torso.

Peleus entrusted Achilles to Chiron

In Greek mythology, Chiron ( ; also Cheiron or Kheiron; ) was held to be the superlative centaur amongst his brethren since he was called the "wisest and justest of all the centaurs".

Biography

Chiron was notable throughout Greek mythology ...

the Centaur

A centaur ( ; grc, κένταυρος, kéntauros; ), or occasionally hippocentaur, is a creature from Greek mythology with the upper body of a human and the lower body and legs of a horse.

Centaurs are thought of in many Greek myths as bein ...

, who lived on Mount Pelion, to be reared. Thetis foretold that her son's fate was either to gain glory and die young, or to live a long but uneventful life in obscurity. Achilles chose the former, and decided to take part in the Trojan War. According to Homer, Achilles grew up in Phthia with his companion Patroclus

In Greek mythology, as recorded in Homer's ''Iliad'', Patroclus (pronunciation variable but generally ; grc, Πάτροκλος, Pátroklos, glory of the father) was a childhood friend, close wartime companion, and the presumed (by some later a ...

.

According to Photius

Photios I ( el, Φώτιος, ''Phōtios''; c. 810/820 – 6 February 893), also spelled PhotiusFr. Justin Taylor, essay "Canon Law in the Age of the Fathers" (published in Jordan Hite, T.O.R., & Daniel J. Ward, O.S.B., "Readings, Cases, Materia ...

, the sixth book of the ''New History'' by Ptolemy Hephaestion Ptolemy Chennus or Chennos ("quail") ( grc-koi, Πτολεμαῖος Χέννος ''Ptolemaios Chennos''), was an Alexandrine grammarian during the reigns of Trajan and Hadrian.

According to the ''Suda'', he was the author of an historical drama ...

reported that Thetis burned in a secret place the children she had by Peleus. When she had Achilles, Peleus noticed, tore him from the flames with only a burnt foot, and confided him to the centaur Chiron. Later Chiron exhumed the body of the Damysus, who was the fastest of all the giants, removed the ankle, and incorporated it into Achilles' burnt foot.

Other names

Among the appellations under which Achilles is generally known are the following: * Pyrisous, "saved from the fire", his first name, which seems to favour the tradition in which his mortal parts were burned by his mother Thetis * Aeacides, from his grandfatherAeacus

Aeacus (; also spelled Eacus; Ancient Greek: Αἰακός) was a mythological king of the island of Aegina in the Saronic Gulf. He was a son of Zeus and the nymph Aegina, and the father of the heroes Peleus and Telamon. According to legend, ...

* Aemonius, from Aemonia, a country which afterwards acquired the name of Thessaly

* Aspetos, "inimitable" or "vast", his name at Epirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region

, image_map = Epirus antiquus tabula.jpg

, map_alt =

, map_caption = Map of ancient Epirus by Heinri ...

* Larissaeus, from Larissa

Larissa (; el, Λάρισα, , ) is the capital and largest city of the Thessaly region in Greece. It is the fifth-most populous city in Greece with a population of 144,651 according to the 2011 census. It is also capital of the Larissa regiona ...

(also called Cremaste), a town of Achaia Phthiotis in Thessaly

* Ligyron, his original name

* Nereius, from his mother Thetis, one of the Nereid

In Greek mythology, the Nereids or Nereides ( ; grc, Νηρηΐδες, Nērēḯdes; , also Νημερτές) are sea nymphs (female spirits of sea waters), the 50 daughters of the ' Old Man of the Sea' Nereus and the Oceanid Doris, sisters ...

s

* Pelides, from his father, Peleus

In Greek mythology, Peleus (; Ancient Greek: Πηλεύς ''Pēleus'') was a hero, king of Phthia, husband of Thetis and the father of their son Achilles. This myth was already known to the hearers of Homer in the late 8th century BC.

Bi ...

* Phthius, from his birthplace, Phthia

In Greek mythology Phthia (; grc-gre, Φθία or Φθίη ''Phthía, Phthíē'') was a city or district in ancient Thessaly. It is frequently mentioned in Homer's ''Iliad'' as the home of the Myrmidones, the contingent led by Achilles in the ...

* Podarkes, "swift-footed", due to the wings of Arke

In Greek mythology, Arke or Arce ( grc-gre, Ἄρκη, ''Árkē'', meaning "swift") is one of the daughters of Thaumas and sister to Iris. During the Titanomachy, Arke fled from the Olympians' camp and joined the Titans, unlike Iris who remained ...

being attached to his feet.

Hidden on Skyros

Some post-Homeric sources claim that in order to keep Achilles safe from the war, Thetis (or, in some versions, Peleus) hid the young man dressed as a princess or at least a girl at the court of

Some post-Homeric sources claim that in order to keep Achilles safe from the war, Thetis (or, in some versions, Peleus) hid the young man dressed as a princess or at least a girl at the court of Lycomedes

In Greek mythology, Lycomedes ( grc, Λυκομήδης), also known as Lycurgus, was the most prominent king of the Dolopians in the island of Scyros near Euboea during the Trojan War.

Family

Lycomedes was the father of seven daughters inc ...

, king of Skyros

Skyros ( el, Σκύρος, ), in some historical contexts Latinized Scyros ( grc, Σκῦρος, ), is an island in Greece, the southernmost of the Sporades, an archipelago in the Aegean Sea. Around the 2nd millennium BC and slightly later, the ...

.

There, Achilles, properly disguised, lived among Lycomedes' daughters, perhaps under the name "Pyrrha

In Greek mythology, Pyrrha (; Ancient Greek: Πύρρα) was the daughter of Epimetheus and Pandora and wife of Deucalion of whom she had three sons, Hellen, Amphictyon, Orestheus; and three daughters Protogeneia, Pandora II and Thyia. Accordi ...

" (the red-haired girl), Cercysera or Aissa ("swift"). With Lycomedes' daughter Deidamia, whom in the account of Statius he raped, Achilles there fathered two sons, Neoptolemus

In Greek mythology, Neoptolemus (; ), also called Pyrrhus (; ), was the son of the warrior Achilles and the princess Deidamia, and the brother of Oneiros. He became the mythical progenitor of the ruling dynasty of the Molossians of ancient Ep ...

(also called Pyrrhus, after his father's possible alias) and Oneiros. According to this story, Odysseus learned from the prophet Calchas that the Achaeans would be unable to capture Troy without Achilles' aid. Odysseus went to Skyros in the guise of a peddler selling women's clothes and jewellery and placed a shield and spear among his goods. When Achilles instantly took up the spear, Odysseus saw through his disguise and convinced him to join the Greek campaign. In another version of the story, Odysseus arranged for a trumpet alarm to be sounded while he was with Lycomedes' women. While the women fled in panic, Achilles prepared to defend the court, thus giving his identity away.

In the Trojan War

According to the ''Iliad'', Achilles arrived at Troy with 50 ships, each carrying 50

According to the ''Iliad'', Achilles arrived at Troy with 50 ships, each carrying 50 Myrmidons

In Greek mythology, the Myrmidons (or Myrmidones; el, Μυρμιδόνες) were an ancient Thessalian Greek tribe. In Homer's ''Iliad'', the Myrmidons are the soldiers commanded by Achilles. Their eponymous ancestor was Myrmidon, a king of ...

. He appointed five leaders (each leader commanding 500 Myrmidons): Menesthius, Eudorus, Peisander, Phoenix

Phoenix most often refers to:

* Phoenix (mythology), a legendary bird from ancient Greek folklore

* Phoenix, Arizona, a city in the United States

Phoenix may also refer to:

Mythology

Greek mythological figures

* Phoenix (son of Amyntor), a ...

and Alcimedon.

Telephus

When the Greeks left for the Trojan War, they accidentally stopped inMysia

Mysia (UK , US or ; el, Μυσία; lat, Mysia; tr, Misya) was a region in the northwest of ancient Asia Minor (Anatolia, Asian part of modern Turkey). It was located on the south coast of the Sea of Marmara. It was bounded by Bithynia on th ...

, ruled by King Telephus

In Greek mythology, Telephus (; grc-gre, Τήλεφος, ''Tēlephos'', "far-shining") was the son of Heracles and Auge, who was the daughter of king Aleus of Tegea. He was adopted by Teuthras, the king of Mysia, in Asia Minor, whom he succe ...

. In the resulting battle, Achilles gave Telephus a wound that would not heal; Telephus consulted an oracle, who stated that "he that wounded shall heal". Guided by the oracle, he arrived at Argos

Argos most often refers to:

* Argos, Peloponnese, a city in Argolis, Greece

** Ancient Argos, the ancient city

* Argos (retailer), a catalogue retailer operating in the United Kingdom and Ireland

Argos or ARGOS may also refer to:

Businesses

...

, where Achilles healed him in order that he might become their guide for the voyage to Troy.

According to other reports in Euripides

Euripides (; grc, Εὐριπίδης, Eurīpídēs, ; ) was a tragedian of classical Athens. Along with Aeschylus and Sophocles, he is one of the three ancient Greek tragedians for whom any plays have survived in full. Some ancient scholars a ...

' lost play about Telephus, he went to Aulis pretending to be a beggar and asked Achilles to heal his wound. Achilles refused, claiming to have no medical knowledge. Alternatively, Telephus held Orestes

In Greek mythology, Orestes or Orestis (; grc-gre, Ὀρέστης ) was the son of Clytemnestra and Agamemnon, and the brother of Electra. He is the subject of several Ancient Greek plays and of various myths connected with his madness an ...

for ransom, the ransom being Achilles' aid in healing the wound. Odysseus reasoned that the spear had inflicted the wound; therefore, the spear must be able to heal it. Pieces of the spear were scraped off onto the wound and Telephus was healed.

Troilus

Cypria

The ''Cypria'' (; grc-gre, Κύπρια ''Kúpria''; Latin: ''Cypria'') is a lost epic poem of ancient Greek literature, which has been attributed to Stasinus and was quite well known in classical antiquity and fixed in a received text, but which ...

'' (the part of the Epic Cycle

The Epic Cycle ( grc, Ἐπικὸς Κύκλος, Epikòs Kýklos) was a collection of Ancient Greek epic poems, composed in dactylic hexameter and related to the story of the Trojan War, including the '' Cypria'', the ''Aethiopis'', the so-ca ...

that tells the events of the Trojan War before Achilles' wrath), when the Achaeans desired to return home, they were restrained by Achilles, who afterwards attacked the cattle of Aeneas

In Greco-Roman mythology, Aeneas (, ; from ) was a Trojan hero, the son of the Trojan prince Anchises and the Greek goddess Aphrodite (equivalent to the Roman Venus). His father was a first cousin of King Priam of Troy (both being grandsons ...

, sacked neighbouring cities (like Pedasus

Pedasus (Ancient Greek: Πήδασος) has been identified with several personal and place names in Greek history and mythology.

Persons

In Homer's ''Iliad'', Pedasus was the name of a Trojan warrior, and the son of the naiad Abarbarea and hu ...

and Lyrnessus In Greek mythology, Lyrnessus (; grc, Λυρνησσός) was a town or city in Dardania (Asia minor), inhabited by Cilicians. It was closely associated with the nearby Cilician Thebe. At the time of the Trojan War, it was said to have been ruled ...

, where the Greeks capture the queen Briseis) and killed Tenes

In Greek mythology, Tenes or Tennes (Ancient Greek: Τέννης) was the eponymous hero of the island of Tenedos.

Family

Tenes was the son either of Apollo or of King Cycnus of Colonae by Proclia, daughter or granddaughter of Laomedon.

...

, a son of Apollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label= Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label ...

, as well as Priam's son Troilus

Troilus ( or ; grc, Τρωΐλος, Troïlos; la, Troilus) is a legendary character associated with the story of the Trojan War. The first surviving reference to him is in Homer's ''Iliad,'' composed in the late 8th century BCE.

In Greek myth ...

in the sanctuary of Apollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label= Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label ...

Thymbraios; however, the romance between Troilus and Chryseis described in Geoffrey Chaucer's ''Troilus and Criseyde

''Troilus and Criseyde'' () is an epic poem by Geoffrey Chaucer which re-tells in Middle English the tragic story of the lovers Troilus and Criseyde set against a backdrop of war during the siege of Troy. It was written in '' rime royale'' a ...

'' and in William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

's ''Troilus and Cressida

''Troilus and Cressida'' ( or ) is a play by William Shakespeare, probably written in 1602.

At Troy during the Trojan War, Troilus and Cressida begin a love affair. Cressida is forced to leave Troy to join her father in the Greek camp. Meanwh ...

'' is a medieval invention.

In Dares Phrygius

Dares Phrygius ( grc, Δάρης), according to Homer, was a Trojan priest of Hephaestus. He was supposed to have been the author of an account of the destruction of Troy, and to have lived before Homer. A work in Latin, purporting to be a transla ...

' ''Account of the Destruction of Troy'', the Latin summary through which the story of Achilles was transmitted to medieval Europe, as well as in older accounts, Troilus was a young Trojan prince, the youngest of King Priam's and Hecuba

Hecuba (; also Hecabe; grc, Ἑκάβη, Hekábē, ) was a queen in Greek mythology, the wife of King Priam of Troy during the Trojan War.

Description

Hecuba was described by the chronicler Malalas in his account of the ''Chronography'' as "da ...

's five legitimate sons (or according other sources, another son of Apollo). Despite his youth, he was one of the main Trojan war leaders, a "horse fighter" or "chariot fighter" according to Homer. Prophecies linked Troilus' fate to that of Troy and so he was ambushed in an attempt to capture him. Yet Achilles, struck by the beauty of both Troilus and his sister Polyxena

In Greek mythology, Polyxena (; Greek: ) was the youngest daughter of King Priam of Troy and his queen, Hecuba. She does not appear in Homer, but in several other classical authors, though the details of her story vary considerably. After the ...

, and overcome with lust, directed his sexual attentions on the youth – who, refusing to yield, instead found himself decapitated upon an altar-omphalos of Apollo Thymbraios. Later versions of the story suggested Troilus was accidentally killed by Achilles in an over-ardent lovers' embrace. In this version of the myth, Achilles' death therefore came in retribution for this sacrilege. Ancient writers treated Troilus as the epitome of a dead child mourned by his parents. Had Troilus lived to adulthood, the First Vatican Mythographer claimed, Troy would have been invincible; however, the motif is older and found already in Plautus

Titus Maccius Plautus (; c. 254 – 184 BC), commonly known as Plautus, was a Roman playwright of the Old Latin period. His comedies are the earliest Latin literary works to have survived in their entirety. He wrote Palliata comoedia, the ...

' ''Bacchides''.

In the ''Iliad''

Homer's ''Iliad'' is the most famous narrative of Achilles' deeds in the Trojan War. Achilles' wrath (μῆνις Ἀχιλλέως, ''mênis Achilléōs'') is the central theme of the poem. The first two lines of the ''Iliad'' read: The Homeric epic only covers a few weeks of the decade-long war, and does not narrate Achilles' death. It begins with Achilles' withdrawal from battle after being dishonoured byAgamemnon

In Greek mythology, Agamemnon (; grc-gre, Ἀγαμέμνων ''Agamémnōn'') was a king of Mycenae who commanded the Greeks during the Trojan War. He was the son, or grandson, of King Atreus and Queen Aerope, the brother of Menelaus, the ...

, the commander of the Achaean forces. Agamemnon has taken a woman named Chryseis as his slave. Her father Chryses

In Greek mythology, Chryses (; Greek, Χρύσης ''Khrúsēs'', meaning "golden") was a Trojan priest of Apollo at Chryse, near the city of Troy.

Family

According to a tradition mentioned by Eustathius of Thessalonica, Chryses and Briseus ...

, a priest of Apollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label= Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label ...

, begs Agamemnon to return her to him. Agamemnon refuses, and Apollo sends a plague amongst the Greeks. The prophet Calchas correctly determines the source of the troubles but will not speak unless Achilles vows to protect him. Achilles does so, and Calchas declares that Chryseis must be returned to her father. Agamemnon consents, but then commands that Achilles' battle prize Briseis, the daughter of Briseus In Greek mythology, Briseus (Ancient Greek: Βρισεύς) or Brises (Ancient Greek: Βρίσης) is the father of Briseis (Hippodameia), a maiden captured by the Greeks during the Trojan War, as recorded in the ''Iliad''. Eustathius of Thessalo ...

, be brought to him to replace Chryseis. Angry at the dishonour of having his plunder and glory taken away (and, as he says later, because he loves Briseis), with the urging of his mother Thetis, Achilles refuses to fight or lead his troops alongside the other Greek forces. At the same time, burning with rage over Agamemnon's theft, Achilles prays

''Prays'' is a genus of moths of the family Praydidae, formerly assigned to (depending on the author) Plutellidae or Yponomeutidae.

Selected species

*'' Prays acmonias'' - Meyrick, 1914 (from India)

*''Prays alpha'' - Moriuti, 1977 (from Japan) ...

to Thetis to convince Zeus to help the Trojans gain ground in the war, so that he may regain his honour.

As the battle turns against the Greeks, thanks to the influence of Zeus, Nestor declares that the Trojans are winning because Agamemnon has angered Achilles, and urges the king to appease the warrior. Agamemnon agrees and sends Odysseus and two other chieftains, Ajax

Ajax may refer to:

Greek mythology and tragedy

* Ajax the Great, a Greek mythological hero, son of King Telamon and Periboea

* Ajax the Lesser, a Greek mythological hero, son of Oileus, the king of Locris

* ''Ajax'' (play), by the ancient Gree ...

and Phoenix

Phoenix most often refers to:

* Phoenix (mythology), a legendary bird from ancient Greek folklore

* Phoenix, Arizona, a city in the United States

Phoenix may also refer to:

Mythology

Greek mythological figures

* Phoenix (son of Amyntor), a ...

. They promise that, if Achilles returns to battle, Agamemnon will return the captive Briseis and other gifts. Achilles rejects all Agamemnon offers him and simply urges the Greeks to sail home as he was planning to do.

The Trojans, led by

The Trojans, led by Hector

In Greek mythology, Hector (; grc, Ἕκτωρ, Hektōr, label=none, ) is a character in Homer's Iliad. He was a Trojan prince and the greatest warrior for Troy during the Trojan War. Hector led the Trojans and their allies in the defense o ...

, subsequently push the Greek army back toward the beaches and assault the Greek ships. With the Greek forces on the verge of absolute destruction, Patroclus

In Greek mythology, as recorded in Homer's ''Iliad'', Patroclus (pronunciation variable but generally ; grc, Πάτροκλος, Pátroklos, glory of the father) was a childhood friend, close wartime companion, and the presumed (by some later a ...

leads the Myrmidons

In Greek mythology, the Myrmidons (or Myrmidones; el, Μυρμιδόνες) were an ancient Thessalian Greek tribe. In Homer's ''Iliad'', the Myrmidons are the soldiers commanded by Achilles. Their eponymous ancestor was Myrmidon, a king of ...

into battle, wearing Achilles' armour, though Achilles remains at his camp. Patroclus succeeds in pushing the Trojans back from the beaches, but is killed by Hector before he can lead a proper assault on the city of Troy.

After receiving the news of the death of Patroclus from Antilochus, the son of Nestor, Achilles grieves over his beloved companion's death. His mother Thetis comes to comfort the distraught Achilles. She persuades Hephaestus

Hephaestus (; eight spellings; grc-gre, Ἥφαιστος, Hḗphaistos) is the Greek god of blacksmiths, metalworking, carpenters, craftsmen, artisans, sculptors, metallurgy, fire (compare, however, with Hestia), and volcanoes.Walter B ...

to make new armour for him, in place of the armour that Patroclus had been wearing, which was taken by Hector. The new armour includes the Shield of Achilles

The shield of Achilles is the shield that Achilles uses in his fight with Hector, famously described in a passage in Book 18, lines 478–608 of Homer's ''Iliad''. The intricately detailed imagery on the shield has inspired many different interpr ...

, described in great detail in the poem.

Enraged over the death of Patroclus, Achilles ends his refusal to fight and takes the field, killing many men in his rage but always seeking out Hector. Achilles even engages in battle with the river god Scamander

Scamander (; also Skamandros ( grc, Σκάμανδρος) or Xanthos () was a river god in Greek mythology.

Etymology

The meaning of this name is uncertain. The second element looks like it is derived from Greek () meaning 'of a man', but t ...

, who has become angry that Achilles is choking his waters with all the men he has killed. The god tries to drown Achilles but is stopped by Hera

In ancient Greek religion, Hera (; grc-gre, Ἥρα, Hḗrā; grc, Ἥρη, Hḗrē, label=none in Ionic and Homeric Greek) is the goddess of marriage, women and family, and the protector of women during childbirth. In Greek mythology, she ...

and Hephaestus. Zeus himself takes note of Achilles' rage and sends the gods to restrain him so that he will not go on to sack Troy itself before the time allotted for its destruction, seeming to show that the unhindered rage of Achilles can defy fate itself. Finally, Achilles finds his prey. Achilles chases Hector around the wall of Troy three times before Athena

Athena or Athene, often given the epithet Pallas, is an ancient Greek religion, ancient Greek goddess associated with wisdom, warfare, and handicraft who was later syncretism, syncretized with the Roman goddess Minerva. Athena was regarded ...

, in the form of Hector's favorite and dearest brother, Deiphobus

In Greek mythology, Deiphobus ( grc, , Dēḯphobos) was a son of Priam and Hecuba. He was a prince of Troy, and the greatest of Priam's sons after Hector and Paris. Deiphobus killed four men of fame in the Trojan War.

Description

Deiphob ...

, persuades Hector to stop running and fight Achilles face to face. After Hector realizes the trick, he knows the battle is inevitable. Wanting to go down fighting, he charges at Achilles with his only weapon, his sword, but misses. Accepting his fate, Hector begs Achilles not to spare his life, but to treat his body with respect after killing him. Achilles tells Hector it is hopeless to expect that of him, declaring that "my rage, my fury would drive me now to hack your flesh away and eat you raw – such agonies you have caused me". Achilles then kills Hector and drags his corpse by its heels behind his chariot. After having a dream where Patroclus begs Achilles to hold his funeral, Achilles hosts a series of funeral games in honour of his companion.

At the onset of his duel with Hector, Achilles is referred to as the brightest star in the sky, which comes on in the autumn, Orion's dog (Sirius

Sirius is the brightest star in the night sky. Its name is derived from the Greek word , or , meaning 'glowing' or 'scorching'. The star is designated α Canis Majoris, Latinized to Alpha Canis Majoris, and abbreviated Alpha CM ...

); a sign of evil. During the cremation of Patroclus, he is compared to Hesperus

In Greek mythology, Hesperus (; grc, Ἕσπερος, Hésperos) is the Evening Star, the planet Venus in the evening. He is one of the '' Astra Planeta''. A son of the dawn goddess Eos ( Roman Aurora), he is the half-brother of her other son, ...

, the evening/western star (Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never f ...

), while the burning of the funeral pyre lasts until Phosphorus

Phosphorus is a chemical element with the symbol P and atomic number 15. Elemental phosphorus exists in two major forms, white phosphorus and red phosphorus, but because it is highly reactive, phosphorus is never found as a free element on Ear ...

, the morning/eastern star (also Venus) has set (descended).

With the assistance of the god Hermes

Hermes (; grc-gre, wikt:Ἑρμῆς, Ἑρμῆς) is an Olympian deity in ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology. Hermes is considered the herald of the gods. He is also considered the protector of human heralds, travelle ...

(Argeiphontes), Hector's father Priam goes to Achilles' tent to plead with Achilles for the return of Hector's body so that he can be buried. Achilles relents and promises a truce for the duration of the funeral, lasting 9 days with a burial on the 10th (in the tradition of Niobe

In Greek mythology, Niobe (; grc-gre, Νιόβη ) was a daughter of Tantalus and of either Dione, the most frequently cited, or of Eurythemista or Euryanassa, the wife of Amphion and the sister of Pelops and Broteas.

Her father was the r ...

's offspring). The poem ends with a description of Hector's funeral, with the doom of Troy and Achilles himself still to come.

Later epic accounts: fighting Penthesilea and Memnon

The '' Aethiopis'' (7th century BC) and a work named ''

The '' Aethiopis'' (7th century BC) and a work named ''Posthomerica

The ''Posthomerica'' ( grc-gre, τὰ μεθ᾿ Ὅμηρον, translit. ''tà meth᾿ Hómēron''; lit. "Things After Homer") is an epic poem in Greek hexameter verse by Quintus of Smyrna. Probably written in the 3rd century AD, it tells the sto ...

'', composed by Quintus of Smyrna

Quintus Smyrnaeus (also Quintus of Smyrna; el, Κόϊντος Σμυρναῖος, ''Kointos Smyrnaios'') was a Greek epic poet whose ''Posthomerica'', following "after Homer", continues the narration of the Trojan War. The dates of Quintus Smy ...

in the fourth century CE, relate further events from the Trojan War

In Greek mythology, the Trojan War was waged against the city of Troy by the Achaeans ( Greeks) after Paris of Troy took Helen from her husband Menelaus, king of Sparta. The war is one of the most important events in Greek mythology and ...

. When Penthesilea

Penthesilea ( el, Πενθεσίλεια, Penthesíleia) was an Amazonian queen in Greek mythology, the daughter of Ares and Otrera and the sister of Hippolyta, Antiope and Melanippe. She assisted Troy in the Trojan War, during which she w ...

, queen of the Amazons and daughter of Ares, arrives in Troy, Priam hopes that she will defeat Achilles. After his temporary truce with Priam, Achilles fights and kills the warrior queen, only to grieve over her death later. At first, he was so distracted by her beauty, he did not fight as intensely as usual. Once he realized that his distraction was endangering his life, he refocused and killed her.

Following the death of Patroclus, Nestor's son Antilochus becomes Achilles' closest companion. When Memnon

In Greek mythology, Memnon (; Ancient Greek: Μέμνων means 'resolute') was a king of Aethiopia and son of Tithonus and Eos. As a warrior he was considered to be almost Achilles' equal in skill. During the Trojan War, he brought an army t ...

, son of the Dawn Goddess Eos

In ancient Greek mythology and religion, Eos (; Ionic and Homeric Greek ''Ēṓs'', Attic ''Héōs'', "dawn", or ; Aeolic ''Aúōs'', Doric ''Āṓs'') is the goddess and personification of the dawn, who rose each morning from her home at ...

and king of Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

, slays Antilochus, Achilles once more obtains revenge on the battlefield, killing Memnon. Consequently, Eos will not let the sun rise until Zeus persuades her. The fight between Achilles and Memnon over Antilochus echoes that of Achilles and Hector over Patroclus, except that Memnon (unlike Hector) was also the son of a goddess.

Many Homeric scholars argued that episode inspired many details in the ''Iliad''s description of the death of Patroclus and Achilles' reaction to it. The episode then formed the basis of the cyclic epic '' Aethiopis'', which was composed after the ''Iliad'', possibly in the 7th century BC. The ''Aethiopis'' is now lost, except for scattered fragments quoted by later authors.

Achilles and Patroclus

The exact nature of Achilles' relationship with Patroclus has been a subject of dispute in both the classical period and modern times. In the ''Iliad'', it appears to be the model of a deep and loyal friendship. Homer does not suggest that Achilles and his close friend Patroclus had sexual relations. Although there is no direct evidence in the text of the ''Iliad'' that Achilles and Patroclus were lovers, this theory was expressed by some later authors. Commentators fromclassical antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

to the present have often interpreted the relationship through the lens of their own cultures. In 5th-century BC Athens, the intense bond was often viewed in light of the Greek custom of ''paiderasteia'', which is the relationship between an older male and a younger one, usually a teenager. In Patroclus and Achilles' case, Achilles would have been the younger as Patroclus is usually seen as his elder. In Plato's ''Symposium'', the participants in a dialogue about love assume that Achilles and Patroclus were a couple; Phaedrus argues that Achilles was the younger and more beautiful one so he was the beloved and Patroclus was the lover. However, ancient Greek had no words to distinguish heterosexual

Heterosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction or sexual behavior between people of the opposite sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, heterosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" ...

and homosexual, and it was assumed that a man could both desire handsome young men and have sex with women. Many pairs of men throughout history have been compared to Achilles and Patroclus to imply a homosexual relationship.

Death

Hector

In Greek mythology, Hector (; grc, Ἕκτωρ, Hektōr, label=none, ) is a character in Homer's Iliad. He was a Trojan prince and the greatest warrior for Troy during the Trojan War. Hector led the Trojans and their allies in the defense o ...

predicts with his last dying breath that Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

and Apollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label= Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label ...

will slay him at the Scaean Gates leading to Troy (with an arrow to the heel according to Statius). ''In Book XXIII'', the sad spirit of dead Patroclus visits Achilles just as he drifts off into slumber, requesting that his bones be placed with those of Achilles in his golden vase, a gift of his mother.

In the ''

In the ''Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Iliad'', th ...

Book XI'', Odysseus sails to the underworld and converses with the shades. One of these is Achilles, who when greeted as "blessed in life, blessed in death", responds that he would rather be a slave to the worst of masters than be king of all the dead. But Achilles then asks Odysseus of his son's exploits in the Trojan war, and when Odysseus tells of Neoptolemus' heroic actions, Achilles is filled with satisfaction.

In the ''Odyssey Book XXIV'' we read dead King Agamemnon's ghostly account of his death: Achilles' funeral pyre

A pyre ( grc, πυρά; ''pyrá'', from , ''pyr'', "fire"), also known as a funeral pyre, is a structure, usually made of wood, for burning a body as part of a funeral rite or execution. As a form of cremation, a body is placed upon or under the ...

bleached bones had been mixed with those of Patroclus

In Greek mythology, as recorded in Homer's ''Iliad'', Patroclus (pronunciation variable but generally ; grc, Πάτροκλος, Pátroklos, glory of the father) was a childhood friend, close wartime companion, and the presumed (by some later a ...

and put into his mother's golden vase. Also, the bones of Antilocus, who had become closer to Achilles than any other following Patroclus' death, were separately enclosed. And, the customary funeral games of a hero were performed, and a massive tomb or mound

A mound is a heaped pile of earth, gravel, sand, rocks, or debris. Most commonly, mounds are earthen formations such as hills and mountains, particularly if they appear artificial. A mound may be any rounded area of topographically higher ...

was built on the Hellespont for approaching seagoers to celebrate.

Achilles was represented in the ''Aethiopis'' as living after his death in the island of Leuke

Snake Island, also known as Serpent Island or Zmiinyi Island ( uk, острів Змії́ний, ostriv Zmiinyi; ro, Insula Șerpilor; russian: Змеиный, Zmeinyy), is an island belonging to Ukraine located in the Black Sea, near the D ...

at the mouth of the river Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , p ...

. Another version of Achilles' death is that he fell deeply in love with one of the Trojan princesses, Polyxena

In Greek mythology, Polyxena (; Greek: ) was the youngest daughter of King Priam of Troy and his queen, Hecuba. She does not appear in Homer, but in several other classical authors, though the details of her story vary considerably. After the ...

. Achilles asks Priam for Polyxena's hand in marriage. Priam is willing because it would mean the end of the war and an alliance with the world's greatest warrior. But while Priam is overseeing the private marriage of Polyxena and Achilles, Paris, who would have to give up Helen if Achilles married his sister, hides in the bushes and shoots Achilles with a divine arrow, killing him. According to some accounts, he had married Medea

In Greek mythology, Medea (; grc, Μήδεια, ''Mēdeia'', perhaps implying "planner / schemer") is the daughter of King Aeëtes of Colchis, a niece of Circe and the granddaughter of the sun god Helios. Medea figures in the myth of Jason an ...

in life, so that after both their deaths they were united in the Elysian Fields of Hades – as Hera promised Thetis in Apollonius' ''Argonautica

The ''Argonautica'' ( el, Ἀργοναυτικά , translit=Argonautika) is a Greek epic poem written by Apollonius Rhodius in the 3rd century BC. The only surviving Hellenistic epic, the ''Argonautica'' tells the myth of the voyage of Jas ...

'' (3rd century BC).

Fate of Achilles' armour

Achilles' armour was the object of a feud between Odysseus and

Achilles' armour was the object of a feud between Odysseus and Telamonian Ajax

Ajax () or Aias (; grc, Αἴας, Aíās , ''Aíantos''; archaic ) is a Greek mythological hero, the son of King Telamon and Periboea, and the half-brother of Teucer. He plays an important role, and is portrayed as a towering figure an ...

(Ajax the greater). They competed for it by giving speeches on why they were the bravest after Achilles to their Trojan prisoners, who, after considering both men's presentations, decided Odysseus was more deserving of the armour. Furious, Ajax cursed Odysseus, which earned him the ire of Athena, who temporarily made Ajax so mad with grief and anguish that he began killing sheep, thinking them his comrades. After a while, when Athena lifted his madness and Ajax realized that he had actually been killing sheep, he was so ashamed that he committed suicide. Odysseus eventually gave the armour to Neoptolemus

In Greek mythology, Neoptolemus (; ), also called Pyrrhus (; ), was the son of the warrior Achilles and the princess Deidamia, and the brother of Oneiros. He became the mythical progenitor of the ruling dynasty of the Molossians of ancient Ep ...

, the son of Achilles. When Odysseus encounters the shade of Ajax much later in the House of Hades (''Odyssey'' 11.543–566), Ajax is still so angry about the outcome of the competition that he refuses to speak to Odysseus.

The armour they fought for was made by Hephaestus

Hephaestus (; eight spellings; grc-gre, Ἥφαιστος, Hḗphaistos) is the Greek god of blacksmiths, metalworking, carpenters, craftsmen, artisans, sculptors, metallurgy, fire (compare, however, with Hestia), and volcanoes.Walter B ...

thus making it much stronger and more beautiful than any armour a mortal could craft. He was made the gear because his first set was worn by Patroclus

In Greek mythology, as recorded in Homer's ''Iliad'', Patroclus (pronunciation variable but generally ; grc, Πάτροκλος, Pátroklos, glory of the father) was a childhood friend, close wartime companion, and the presumed (by some later a ...

when he went to battle and taken by Hector

In Greek mythology, Hector (; grc, Ἕκτωρ, Hektōr, label=none, ) is a character in Homer's Iliad. He was a Trojan prince and the greatest warrior for Troy during the Trojan War. Hector led the Trojans and their allies in the defense o ...

when he killed Patroclus. The Shield of Achilles

The shield of Achilles is the shield that Achilles uses in his fight with Hector, famously described in a passage in Book 18, lines 478–608 of Homer's ''Iliad''. The intricately detailed imagery on the shield has inspired many different interpr ...

was also made by the fire god. His legendary spear was given to him by his mentor Chiron

In Greek mythology, Chiron ( ; also Cheiron or Kheiron; ) was held to be the superlative centaur amongst his brethren since he was called the "wisest and justest of all the centaurs".

Biography

Chiron was notable throughout Greek mythology ...

before he participated in the Trojan War

In Greek mythology, the Trojan War was waged against the city of Troy by the Achaeans ( Greeks) after Paris of Troy took Helen from her husband Menelaus, king of Sparta. The war is one of the most important events in Greek mythology and ...

. It was called the Pelian Spear which allegedly no other man could wield.

A relic claimed to be Achilles' bronze-headed spear was preserved for centuries in the temple of Athena on the acropolis of Phaselis

Phaselis ( grc, Φασηλίς) or Faselis ( tr, Faselis) was a Greek and Roman city on the coast of ancient Lycia. Its ruins are located north of the modern town Tekirova in the Kemer district of Antalya Province in Turkey. It lies between ...

, Lycia, a port on the Pamphylian Gulf. The city was visited in 333 BC by Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

, who envisioned himself as the new Achilles and carried the ''Iliad'' with him, but his court biographers do not mention the spear; however, it was shown in the time of Pausanias Pausanias ( el, Παυσανίας) may refer to:

*Pausanias of Athens, lover of the poet Agathon and a character in Plato's ''Symposium''

*Pausanias the Regent, Spartan general and regent of the 5th century BC

* Pausanias of Sicily, physician of t ...

in the 2nd century CE.

Achilles, Ajax and a game of ''petteia''

Numerous paintings on pottery have suggested a tale not mentioned in the literary traditions. At some point in the war, Achilles andAjax

Ajax may refer to:

Greek mythology and tragedy

* Ajax the Great, a Greek mythological hero, son of King Telamon and Periboea

* Ajax the Lesser, a Greek mythological hero, son of Oileus, the king of Locris

* ''Ajax'' (play), by the ancient Gree ...

were playing a board game

Board games are tabletop games that typically use . These pieces are moved or placed on a pre-marked board (playing surface) and often include elements of table, card, role-playing, and miniatures games as well.

Many board games feature a co ...

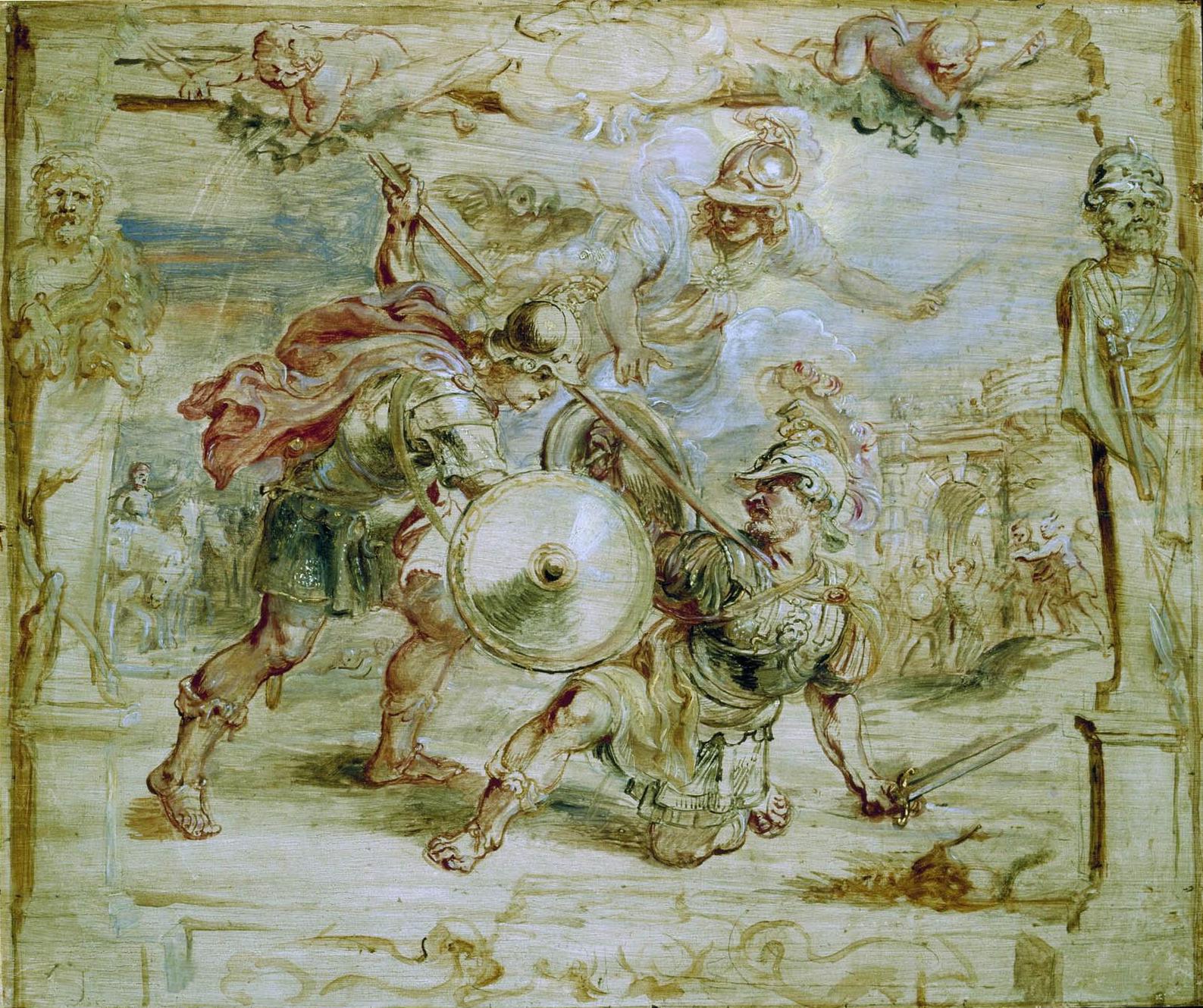

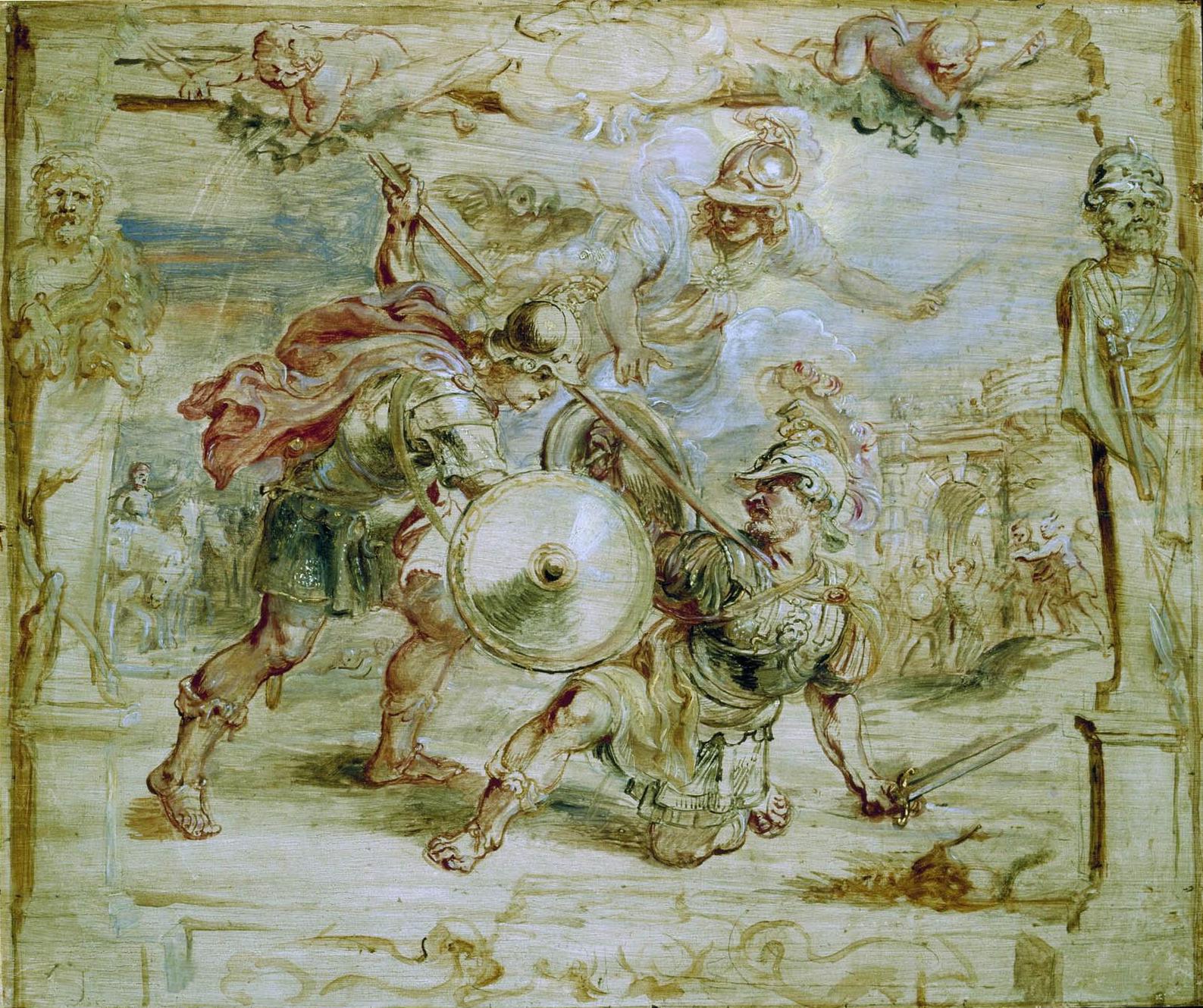

(''petteia''). They were absorbed in the game and oblivious to the surrounding battle. The Trojans attacked and reached the heroes, who were saved only by an intervention of Athena.

Worship and heroic cult

The tomb of Achilles, extant throughout antiquity in

The tomb of Achilles, extant throughout antiquity in Troad

The Troad ( or ; el, Τρωάδα, ''Troáda'') or Troas (; grc, Τρῳάς, ''Trōiás'' or , ''Trōïás'') is a historical region in northwestern Anatolia. It corresponds with the Biga Peninsula ( Turkish: ''Biga Yarımadası'') in the � ...

,Herodotus, '' Histories'' 5.94; Pliny, ''Naturalis Historia

The ''Natural History'' ( la, Naturalis historia) is a work by Pliny the Elder. The largest single work to have survived from the Roman Empire to the modern day, the ''Natural History'' compiles information gleaned from other ancient authors. ...

'' 5.125; Strabo, '' Geographica'' 13.1.32 (C596); Diogenes Laërtius 1.74. was venerated by Thessalians

Thessaly ( el, Θεσσαλία, translit=Thessalía, ; ancient Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic and modern administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, Thessa ...

, but also by Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

expeditionary forces, as well as by Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

and the Roman emperor Caracalla

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (born Lucius Septimius Bassianus, 4 April 188 – 8 April 217), better known by his nickname "Caracalla" () was Roman emperor from 198 to 217. He was a member of the Severan dynasty, the elder son of Emperor S ...

. Achilles' cult was also to be found at other places, e. g. on the island of Astypalaea

In Greek mythology, Astypalaea (Ancient Greek: Ἀστυπάλαια ) or Astypale was a Phoenician princess as the daughter of King Phoenix and Perimede, daughter of Oeneus; thus she was the sister of Europa. In some accounts, her mother was c ...

in the Sporades

The (Northern) Sporades (; el, Βόρειες Σποράδες, ) are an archipelago along the east coast of Greece, northeast of the island of Euboea,"Skyros - Britannica Concise" (description), Britannica Concise, 2006, webpageEB-Skyrosnotes " ...

, in Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referre ...

which had a sanctuary, in Elis

Elis or Ilia ( el, Ηλεία, ''Ileia'') is a historic region in the western part of the Peloponnese peninsula of Greece. It is administered as a regional unit of the modern region of Western Greece. Its capital is Pyrgos. Until 2011 it was ...

and in Achilles' homeland Thessaly

Thessaly ( el, Θεσσαλία, translit=Thessalía, ; ancient Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic and modern administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, The ...

, as well as in the Magna Graecia cities of Tarentum Tarentum may refer to:

* Taranto, Apulia, Italy, on the site of the ancient Roman city of Tarentum (formerly the Greek colony of Taras)

**See also History of Taranto

* Tarentum (Campus Martius), also Terentum, an area in or on the edge of the Camp ...

, Locri

Locri is a town and ''comune'' (municipality) in the province of Reggio Calabria, Calabria, southern Italy. Its name derives from that of the ancient Greek region of Locris. Today it is an important administrative and cultural centre on the Ion ...

and Croton, accounting for an almost Panhellenic cult to the hero.

The cult of Achilles is illustrated in the 500 BC Polyxena sarcophagus

The Polyxena sarcophagus is a late 6th century BCE sarcophagus from Hellespontine Phrygia, at the beginning of the period when it became a Province of the Achaemenid Empire. The sarcophagus was found in the Kızöldün tumulus, in the Granicus r ...

, which depicts the sacrifice of Polyxena near the tumulus of Achilles. Strabo (13.1.32) also suggested that such a cult of Achilles existed in Troad:

The spread and intensity of the hero's veneration among the Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, oth ...

that had settled

A settler is a person who has migrated to an area and established a permanent residence there, often to colonize the area.

A settler who migrates to an area previously uninhabited or sparsely inhabited may be described as a pioneer.

Settle ...

on the northern coast of the Pontus Euxinus

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Roma ...

, today's Black Sea, appears to have been remarkable. An archaic cult is attested for the Milesian colony of Olbia

Olbia (, ; sc, Terranoa; sdn, Tarranoa) is a city and commune of 60,346 inhabitants (May 2018) in the Italian insular province of Sassari in northeastern Sardinia, Italy, in the historical region of Gallura. Called ''Olbia'' in the Roman age ...

as well as for an island in the middle of the Black Sea, today identified with Snake Island (Ukrainian

Ukrainian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Ukraine

* Something relating to Ukrainians, an East Slavic people from Eastern Europe

* Something relating to demographics of Ukraine in terms of demography and population of Ukraine

* So ...

Зміїний, ''Zmiinyi'', near Kiliya

Kiliia or Kilia ( uk, Кілія́, translit=Kiliia, ; ro, Chilia Nouă) is a town in Izmail Raion, Odesa Oblast of southwestern Ukraine. It hosts the administration of Kiliia urban hromada, one of the hromadas of Ukraine. Kiliia is located in t ...

, Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

). Early dedicatory inscriptions from the Greek colonies

Greek colonization was an organised colonial expansion by the Archaic Greeks into the Mediterranean Sea and Black Sea in the period of the 8th–6th centuries BC.

This colonization differed from the migrations of the Greek Dark Ages in that i ...

on the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

(graffiti

Graffiti (plural; singular ''graffiti'' or ''graffito'', the latter rarely used except in archeology) is art that is written, painted or drawn on a wall or other surface, usually without permission and within public view. Graffiti ranges from s ...

and inscribed clay disks, these possibly being votive offering

A votive offering or votive deposit is one or more objects displayed or deposited, without the intention of recovery or use, in a sacred place for religious purposes. Such items are a feature of modern and ancient societies and are generally ...

s, from Olbia, the area of Berezan Island and the Tauric Chersonese) attest the existence of a heroic cult of Achilles from the sixth century BC onwards. The cult was still thriving in the third century CE, when dedicatory stelae

A stele ( ),Anglicized plural steles ( ); Greek plural stelai ( ), from Greek , ''stēlē''. The Greek plural is written , ''stēlai'', but this is only rarely encountered in English. or occasionally stela (plural ''stelas'' or ''stelæ''), whe ...

from Olbia refer to an ''Achilles Pontárchēs'' (Ποντάρχης, roughly "lord of the Sea," or "of the Pontus Euxinus

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Roma ...

"), who was invoked as a protector of the city of Olbia, venerated on par with Olympian gods such as the local Apollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label= Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label ...

Prostates, Hermes

Hermes (; grc-gre, wikt:Ἑρμῆς, Ἑρμῆς) is an Olympian deity in ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology. Hermes is considered the herald of the gods. He is also considered the protector of human heralds, travelle ...

Agoraeus, or Poseidon

Poseidon (; grc-gre, Ποσειδῶν) was one of the Twelve Olympians in ancient Greek religion and myth, god of the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses.Burkert 1985pp. 136–139 In pre-Olympian Bronze Age Greece, he was venerated as ...

.

Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ' ...

(23–79 AD) in his '' Natural History'' mentions a "port of the Achæi" and an "island of Achilles", famous for the tomb of that "man" (), situated somewhat nearby Olbia and the Dnieper-Bug Estuary; furthermore, at 125 Roman mile

The mile, sometimes the international mile or statute mile to distinguish it from other miles, is a British imperial unit and United States customary unit of distance; both are based on the older English unit of length equal to 5,280 Engli ...

s from this island, he places a peninsula "which stretches forth in the shape of a sword" obliquely, called ''Dromos Achilleos'' (Ἀχιλλέως δρόμος, ''Achilléōs drómos'' " the Race-course of Achilles") and considered the place of the hero's exercise or of games instituted by him. This last feature of Pliny's account is considered to be the iconic spit, called today ''Tendra'' (or ''Kosa Tendra'' and ''Kosa Djarilgatch''), situated between the mouth of the Dnieper

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine and ...

and Karkinit Bay, but which is hardly 125 Roman mile

The mile, sometimes the international mile or statute mile to distinguish it from other miles, is a British imperial unit and United States customary unit of distance; both are based on the older English unit of length equal to 5,280 Engli ...

s ( km) away from the Dnieper-Bug estuary, as Pliny states. (To the "Race-course" he gives a length of 80 miles, km, whereas the spit measures km today.)

In the following chapter of his book, Pliny refers to the same island as ''Achillea'' and introduces two further names for it: ''Leuce'' or ''Macaron'' (from Greek �ῆσοςμακαρῶν "island of the blest"). The "present day" measures, he gives at this point, seem to account for an identification of ''Achillea'' or ''Leuce'' with today's Snake Island. Pliny's contemporary Pomponius Mela

Pomponius Mela, who wrote around AD 43, was the earliest Roman geographer. He was born in Tingentera (now Algeciras) and died AD 45.

His short work (''De situ orbis libri III.'') remained in use nearly to the year 1500. It occupies less ...

() tells that Achilles was buried on an island named ''Achillea'', situated between the Borysthenes

Borysthenes (; grc, Βορυσθένης) is a geographical name from classical antiquity. The term usually refers to the Dnieper River and its eponymous river god, but also seems to have been an alternative name for Pontic Olbia, a town situate ...

and the Ister, adding to the geographical confusion. Ruins of a square temple, measuring 30 meters to a side, possibly that dedicated to Achilles, were discovered by Captain Kritzikly () in 1823 on Snake Island. A second exploration in 1840 showed that the construction of a lighthouse had destroyed all traces of this temple. A fifth century BC black-glazed lekythos

A lekythos (plural lekythoi) is a type of ancient Greek vessel used for storing oil (Greek λήκυθος), especially olive oil

Olive oil is a liquid fat obtained from olives (the fruit of ''Olea europaea''; family Oleaceae), a traditiona ...

inscription, found on the island in 1840, reads: "Glaukos, son of Poseidon, dedicated me to Achilles, lord of Leuke." In another inscription from the fifth or fourth century BC, a statue is dedicated to Achilles, lord of Leuke, by a citizen of Olbia, while in a further dedication, the city of Olbia confirms its continuous maintenance of the island's cult, again suggesting its quality as a place of a supra-regional hero veneration.

The heroic cult dedicated to Achilles on ''Leuce'' seems to go back to an account from the lost epic '' Aethiopis'' according to which, after his untimely death, Thetis had snatched her son from the funeral pyre and removed him to a mythical (''Leúkē Nêsos'' "White Island"). Already in the fifth century BC, Pindar

Pindar (; grc-gre, Πίνδαρος , ; la, Pindarus; ) was an Ancient Greek lyric poet from Thebes. Of the canonical nine lyric poets of ancient Greece, his work is the best preserved. Quintilian wrote, "Of the nine lyric poets, Pindar ...

had mentioned a cult of Achilles on a "bright island" (φαεννά νᾶσος, ''phaenná nâsos'') of the Black Sea, while in another of his works, Pindar would retell the story of the immortalized Achilles living on a geographically indefinite Island of the Blest together with other heroes such as his father Peleus

In Greek mythology, Peleus (; Ancient Greek: Πηλεύς ''Pēleus'') was a hero, king of Phthia, husband of Thetis and the father of their son Achilles. This myth was already known to the hearers of Homer in the late 8th century BC.

Bi ...

and Cadmus. Well known is the connection of these mythological Fortunate Isles (μακαρῶν νῆσοι, ''makárôn nêsoi'') or the Homeric Elysium with the stream Oceanus which according to Greek mythology surrounds the inhabited world, which should have accounted for the identification of the northern strands of the Euxine with it. Guy Hedreen has found further evidence for this connection of Achilles with the northern margin of the inhabited world in a poem by Alcaeus, speaking of "Achilles lord of Scythia" and the opposition of North and South, as evoked by Achilles' fight against the Aethiopia