Acetyl-CoA Synthase on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Acetyl-CoA synthase (ACS), not to be confused with

It is now generally accepted that the ACS active site (A-cluster) is a Ni-Ni metal centre with both nickels having a +2

It is now generally accepted that the ACS active site (A-cluster) is a Ni-Ni metal centre with both nickels having a +2  The ACS enzyme contains three main subunits. The first is the active site itself with the NiFeS centre. The second is the portion that directly interacts with CODH in the Wood–Ljungdahl pathway. This part is made up of

The ACS enzyme contains three main subunits. The first is the active site itself with the NiFeS centre. The second is the portion that directly interacts with CODH in the Wood–Ljungdahl pathway. This part is made up of

Two competing mechanisms have been proposed for the formation of acetyl-CoA, the "

Two competing mechanisms have been proposed for the formation of acetyl-CoA, the "

Acetyl-CoA synthetase

Acetyl-CoA synthetase (ACS) or Acetate—CoA ligase is an enzyme () involved in metabolism of acetate. It is in the ligase class of enzymes, meaning that it catalyzes the formation of a new chemical bond between two large molecules.

Reaction

The ...

or Acetate-CoA ligase (ADP forming), is a nickel

Nickel is a chemical element with symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive but large pieces are slow to ...

-containing enzyme involved in the metabolic processes of cells. Together with Carbon monoxide dehydrogenase

In enzymology, carbon monoxide dehydrogenase (CODH) () is an enzyme that catalyzes the chemical reaction

:CO + H2O + A \rightleftharpoons CO2 + AH2

The chemical process catalyzed by carbon monoxide dehydrogenase is similar to the water-gas shif ...

(CODH), it forms the bifunctional enzyme Acetyl-CoA Synthase/Carbon Monoxide Dehydrogenase (ACS/CODH) found in anaerobic organisms such as archaea

Archaea ( ; singular archaeon ) is a domain of single-celled organisms. These microorganisms lack cell nuclei and are therefore prokaryotes. Archaea were initially classified as bacteria, receiving the name archaebacteria (in the Archaebac ...

and bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

. The ACS/CODH enzyme works primarily through the Wood–Ljungdahl pathway

The Wood–Ljungdahl pathway is a set of biochemical reactions used by some bacteria. It is also known as the reductive acetyl-coenzyme A (Acetyl-CoA) pathway. This pathway enables these organisms to use hydrogen as an electron donor, and carb ...

which converts carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide (chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is transpar ...

to Acetyl-CoA

Acetyl-CoA (acetyl coenzyme A) is a molecule that participates in many biochemical reactions in protein, carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. Its main function is to deliver the acetyl group to the citric acid cycle (Krebs cycle) to be oxidized for ...

. The recommended name for this enzyme is CO-methylating acetyl-CoA synthase.

Chemistry

In nature, there are six different pathways where CO is fixed. Of these, theWood–Ljungdahl pathway

The Wood–Ljungdahl pathway is a set of biochemical reactions used by some bacteria. It is also known as the reductive acetyl-coenzyme A (Acetyl-CoA) pathway. This pathway enables these organisms to use hydrogen as an electron donor, and carb ...

is the predominant sink in anaerobic conditions. Acetyl-CoA Synthase (ACS) and carbon monoxide dehydrogenase

In enzymology, carbon monoxide dehydrogenase (CODH) () is an enzyme that catalyzes the chemical reaction

:CO + H2O + A \rightleftharpoons CO2 + AH2

The chemical process catalyzed by carbon monoxide dehydrogenase is similar to the water-gas shif ...

(CODH) are integral enzymes in this one pathway and can perform diverse reactions in the carbon cycle

The carbon cycle is the biogeochemical cycle by which carbon is exchanged among the biosphere, pedosphere, geosphere, hydrosphere, and Earth's atmosphere, atmosphere of the Earth. Carbon is the main component of biological compounds as well as ...

as a result. Because of this, the exact activity of these molecules has come under intense scrutiny over the past decade.

Wood–Ljungdahl pathway

TheWood–Ljungdahl pathway

The Wood–Ljungdahl pathway is a set of biochemical reactions used by some bacteria. It is also known as the reductive acetyl-coenzyme A (Acetyl-CoA) pathway. This pathway enables these organisms to use hydrogen as an electron donor, and carb ...

consists of two different reactions that break down carbon dioxide. The first pathway involves CODH converting carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide (chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is transpar ...

into carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide (chemical formula CO) is a colorless, poisonous, odorless, tasteless, flammable gas that is slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the simple ...

through a two-electron transfer, and the second reaction involves ACS synthesizing acetyl-CoA

Acetyl-CoA (acetyl coenzyme A) is a molecule that participates in many biochemical reactions in protein, carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. Its main function is to deliver the acetyl group to the citric acid cycle (Krebs cycle) to be oxidized for ...

using the carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide (chemical formula CO) is a colorless, poisonous, odorless, tasteless, flammable gas that is slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the simple ...

from CODH together with coenzyme-A (CoA) and a methyl group from a corrinoid iron-sulfur protein, CFeSP. The two main overall reactions are as follows:

The Acetyl-CoA

Acetyl-CoA (acetyl coenzyme A) is a molecule that participates in many biochemical reactions in protein, carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. Its main function is to deliver the acetyl group to the citric acid cycle (Krebs cycle) to be oxidized for ...

produced can be used in a variety of ways depending on the needs of the organism. For example, acetate-forming bacteria use acetyl-CoA

Acetyl-CoA (acetyl coenzyme A) is a molecule that participates in many biochemical reactions in protein, carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. Its main function is to deliver the acetyl group to the citric acid cycle (Krebs cycle) to be oxidized for ...

for their autotroph

An autotroph or primary producer is an organism that produces complex organic compounds (such as carbohydrates, fats, and proteins) using carbon from simple substances such as carbon dioxide,Morris, J. et al. (2019). "Biology: How Life Works", ...

ic growth processes, and methanogenic

Methanogenesis or biomethanation is the formation of methane coupled to energy conservation by microbes known as methanogens. Organisms capable of producing methane for energy conservation have been identified only from the Domain (biology), domai ...

archae such as ''Methanocarcina barkeri'' convert the acetyl-CoA into acetate and use it as an alternative source of carbon instead of CO.

Acetogenic Acetogenesis is a process through which acetate is produced either by the reduction of CO2 or by the reduction of organic acids, rather than by the oxidative breakdown of carbohydrates or ethanol, as with acetic acid bacteria.

The different bacte ...

bacteria use this method to generate acetate and acetic acid

Acetic acid , systematically named ethanoic acid , is an acidic, colourless liquid and organic compound with the chemical formula (also written as , , or ). Vinegar is at least 4% acetic acid by volume, making acetic acid the main component ...

. Since the above two reactions are reversible, it opens up a diverse range of reactions in the carbon cycle. In addition to acetyl-CoA production, the reverse can occur with ACS producing CO and returning the methyl piece back to the corrinoid protein.

Along with the process of methanogenesis

Methanogenesis or biomethanation is the formation of methane coupled to energy conservation by microbes known as methanogens. Organisms capable of producing methane for energy conservation have been identified only from the domain Archaea, a group ...

, organisms can subsequently convert the acetate to methane. Furthermore, the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway allows for the anaerobic oxidation of acetate where ATP is used to convert acetate into acetyl-CoA, which is then broken down by ACS to produce carbon dioxide that is released into the atmosphere.

Other reactions

It has been discovered that the CODH/ACS enzyme in the bacteria ''M. theroaceticum'' can make dinitrogen (N) fromnitrous oxide

Nitrous oxide (dinitrogen oxide or dinitrogen monoxide), commonly known as laughing gas, nitrous, or nos, is a chemical compound, an oxide of nitrogen with the formula . At room temperature, it is a colourless non-flammable gas, and has a ...

in the presence of an electron-donating species. It can also catalyze the reduction of the pollutant, 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT) and catalyze the oxidation

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or a d ...

of ''n''-butyl isocyanide.

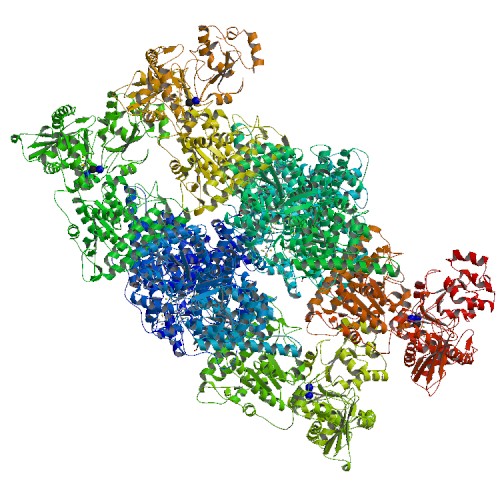

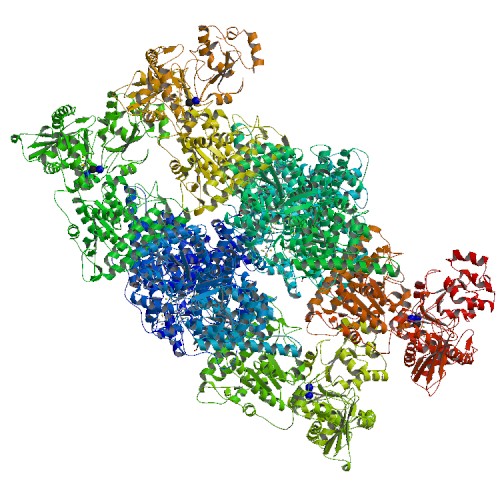

Structure

History

The first, and one of the most comprehensive, crystal structures of ACS/CODH from the bacteria ''M. thermoacetica'' was presented in 2002 by Drennan and colleagues. In this paper they constructed a heterotetramer, with the active site "A-cluster" residing in the ACS subunit and the active site "C-cluster" in CODH subunit. Furthermore, they resolved the structure of the A-cluster active site and found an eSX-Cu-X-Ni centre which is highly unusual in biology. This structural representation consisted of a eSunit bridged to a binuclear centre, where Ni(II) resided in thedistal

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously describe the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position pro ...

position (denoted as Ni) in a square-planar

The square planar molecular geometry in chemistry describes the stereochemistry (spatial arrangement of atoms) that is adopted by certain chemical compounds. As the name suggests, molecules of this geometry have their atoms positioned at the corn ...

conformation and a Cu(I) ion resided in the proximal

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously describe the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position pro ...

position in a distorted tetrahedral

In geometry, a tetrahedron (plural: tetrahedra or tetrahedrons), also known as a triangular pyramid, is a polyhedron composed of four triangular faces, six straight edges, and four vertex corners. The tetrahedron is the simplest of all the o ...

position with ligands of unknown identity.

The debate towards the absolute structure and identity of the metals in the A-cluster active site of ACS continued, with a competing model presented. The authors suggested two different forms of the ACS enzyme, an "Open" form and a "Closed" form, with different metals occupying the proximal

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously describe the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position pro ...

metal site (denoted as M) for each form. The general scheme of the enzyme followed closely with the first study's findings, but this new structure proposed a Nickel ion in the "open" form and a Zinc ion in the "closed" form.

A later review article attempted to reconcile the different observations of M and stated that this proximal position in the active site of ACS was prone to substitution and could contain any one of Cu, Zn and Ni. The three forms of this A-cluster most likely hold a small amount of Ni and a relatively larger amount of Cu.

Present (2014 onwards)

It is now generally accepted that the ACS active site (A-cluster) is a Ni-Ni metal centre with both nickels having a +2

It is now generally accepted that the ACS active site (A-cluster) is a Ni-Ni metal centre with both nickels having a +2 oxidation state

In chemistry, the oxidation state, or oxidation number, is the hypothetical charge of an atom if all of its bonds to different atoms were fully ionic. It describes the degree of oxidation (loss of electrons) of an atom in a chemical compound. C ...

. The eScluster is bridged to the closer nickel, N which is connected via a thiolate bridge to the farther nickel, Ni. Ni is coordinated to two cysteine

Cysteine (symbol Cys or C; ) is a semiessential proteinogenic amino acid with the formula . The thiol side chain in cysteine often participates in enzymatic reactions as a nucleophile.

When present as a deprotonated catalytic residue, sometime ...

molecules and two backbone amide compounds, and is in a square-planar

The square planar molecular geometry in chemistry describes the stereochemistry (spatial arrangement of atoms) that is adopted by certain chemical compounds. As the name suggests, molecules of this geometry have their atoms positioned at the corn ...

coordination. The space next to the metal can accommodate substrates and products. Ni is in a T-shaped environment bound to three sulfur atoms, with an unknown ligand possibly creating a distorted tetrahedral

In geometry, a tetrahedron (plural: tetrahedra or tetrahedrons), also known as a triangular pyramid, is a polyhedron composed of four triangular faces, six straight edges, and four vertex corners. The tetrahedron is the simplest of all the o ...

environment. This ligand has been hypothesized to be a water molecule or an acetyl group in the surrounding area in the cell. Although the proximal nickel is labile and can be replaced with a Cu of Zn centre, experimental evidence suggests that activity of ACS is limited to the presence of nickel only. In addition, some studies have shown that copper can even inhibit the enzyme under certain conditions.

The overall structure of the CODH/ACS enzyme consists of the CODH enzyme as a dimer

Dimer may refer to:

* Dimer (chemistry), a chemical structure formed from two similar sub-units

** Protein dimer, a protein quaternary structure

** d-dimer

* Dimer model, an item in statistical mechanics, based on ''domino tiling''

* Julius Dimer ...

at the centre with two ACS subunits on each side. The CODH core is made up of two Ni-Fe-S clusters (C-cluster), two eSclusters (B-cluster) and one eSD-cluster. The D-cluster bridges the two subunits with one C and one B cluster in each monomer, allowing rapid electron transfer

Electron transfer (ET) occurs when an electron relocates from an atom or molecule to another such chemical entity. ET is a mechanistic description of certain kinds of redox reactions involving transfer of electrons.

Electrochemical processes ar ...

. The A-cluster of ACS is in constant communication with the C-cluster in CODH. This active site is also responsible for the C-C and C-S bond formations in the product acetyl-CoA (and its reverse reaction).

The ACS enzyme contains three main subunits. The first is the active site itself with the NiFeS centre. The second is the portion that directly interacts with CODH in the Wood–Ljungdahl pathway. This part is made up of

The ACS enzyme contains three main subunits. The first is the active site itself with the NiFeS centre. The second is the portion that directly interacts with CODH in the Wood–Ljungdahl pathway. This part is made up of α-helices

The alpha helix (α-helix) is a common motif in the secondary structure of proteins and is a right hand-helix conformation in which every backbone N−H group hydrogen bonds to the backbone C=O group of the amino acid located four residues ear ...

that go into a Rossmann fold

The Rossmann fold is a tertiary fold found in proteins that bind nucleotides, such as enzyme cofactors FAD, NAD+, and NADP+. This fold is composed of alternating beta strands and alpha helical segments where the beta strands are hydrogen bonded ...

. It also appears to interact with a ferredoxin

Ferredoxins (from Latin ''ferrum'': iron + redox, often abbreviated "fd") are iron–sulfur proteins that mediate electron transfer in a range of metabolic reactions. The term "ferredoxin" was coined by D.C. Wharton of the DuPont Co. and applied t ...

compound which may activate the subunit during the CO transferring process from CODH to ACS. The final domain binds CoA and consists of six arginine

Arginine is the amino acid with the formula (H2N)(HN)CN(H)(CH2)3CH(NH2)CO2H. The molecule features a guanidino group appended to a standard amino acid framework. At physiological pH, the carboxylic acid is deprotonated (−CO2−) and both the am ...

residues with a tryptophan

Tryptophan (symbol Trp or W)

is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. Tryptophan contains an α-amino group, an α- carboxylic acid group, and a side chain indole, making it a polar molecule with a non-polar aromatic ...

molecule.

Experiments between the C-cluster of CODH and the A-cluster of ACS reveal a long, hydrophobic

In chemistry, hydrophobicity is the physical property of a molecule that is seemingly repelled from a mass of water (known as a hydrophobe). In contrast, hydrophiles are attracted to water.

Hydrophobic molecules tend to be nonpolar and, th ...

channel connecting the two domains to allow for the transfer of carbon monoxide from CODH to ACS. This channel is most likely to protect the carbon monoxide molecules from the outside environment of the enzyme and to increase efficiency of acetyl-CoA production.

Conformational changes

Studies in literature have been able to isolate the CODH/ACS enzyme in an "open" and "closed" configuration. This has led to the hypothesis that it undergoes four conformational changes depending on its activity. With the "open" position, the active site rotates itself to interact with the CFeSP protein in the methyl transfer step of theWood–Ljungdahl pathway

The Wood–Ljungdahl pathway is a set of biochemical reactions used by some bacteria. It is also known as the reductive acetyl-coenzyme A (Acetyl-CoA) pathway. This pathway enables these organisms to use hydrogen as an electron donor, and carb ...

. The "closed" position opens up the channel between CODH and ACS to allow for the transfer of CO. These two configurations are opposite one another in that access to CO blocks off interaction with CFeSP, and when methylation occurs, the active site is buried and does not allow CO transfer. A second "closed" position is needed to block off water from the reaction. Finally, the A-cluster must be rotated once more to allow for the binding of CoA and release of the product. The exact trigger of these structural changes and the mechanistic details have yet to be resolved.

Activity

Mechanism

Two competing mechanisms have been proposed for the formation of acetyl-CoA, the "

Two competing mechanisms have been proposed for the formation of acetyl-CoA, the "paramagnetic

Paramagnetism is a form of magnetism whereby some materials are weakly attracted by an externally applied magnetic field, and form internal, induced magnetic fields in the direction of the applied magnetic field. In contrast with this behavior, d ...

mechanism" and the "diamagnetic

Diamagnetic materials are repelled by a magnetic field; an applied magnetic field creates an induced magnetic field in them in the opposite direction, causing a repulsive force. In contrast, paramagnetic and ferromagnetic materials are attracted ...

mechanism". Both are similar in terms of the binding of substrates and the general steps, but differ in the oxidation

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or a d ...

state of the metal centre. Ni is believed to be the substrate binding centre which undergoes redox

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate (chemistry), substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of Electron, electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction ...

. The farther nickel centre and the eScluster are not thought to be involved in the process.

In the paramagnetic mechanism, some type of complex (ferrodoxin

Ferredoxins (from Latin ''ferrum'': iron + redox, often abbreviated "fd") are iron–sulfur proteins that mediate electron transfer in a range of metabolic reactions. The term "ferredoxin" was coined by D.C. Wharton of the DuPont Co. and applied to ...

, for example) activates the Ni atom, reducing it from Ni to Ni. The nickel then binds to either carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide (chemical formula CO) is a colorless, poisonous, odorless, tasteless, flammable gas that is slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the simple ...

from CODH or the methyl group donated by the CFeSP protein in no particular order. This is followed by migratory insertion

In organometallic chemistry, a migratory insertion is a type of reaction wherein two ligands on a metal complex combine. It is a subset of reactions that very closely resembles the insertion reactions, and both are differentiated by the mechanism ...

to form an intermediate complex. CoA then binds to the metal and the final product, acetyl-CoA, is formed. Some criticisms of this mechanism are that it is unbalanced in terms of electron count and the activated Ni intermediate cannot be detected with electron paramagnetic resonance

Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) or electron spin resonance (ESR) spectroscopy is a method for studying materials that have unpaired electrons. The basic concepts of EPR are analogous to those of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), but the spin ...

. Furthermore, there is evidence of the ACS catalytic cycle without any external reducing complex, which refutes the ferrodoxin

Ferredoxins (from Latin ''ferrum'': iron + redox, often abbreviated "fd") are iron–sulfur proteins that mediate electron transfer in a range of metabolic reactions. The term "ferredoxin" was coined by D.C. Wharton of the DuPont Co. and applied to ...

activation step.

The second proposed mechanism, the diamagnetic mechanism, involves a Ni intermediate instead of a Ni. After addition of the methyl group and carbon monoxide, followed by insertion to produce the metal-acetyl complex, CoA attacks to produce the final product. The order in which the carbon monoxide molecule and the methyl group bind to the nickel centre has been highly debated, but no solid evidence has demonstrated preference for one over the other. Although this mechanism is electronically balanced, the idea of a Ni species is highly unprecedented in biology. There has also been no solid evidence supporting the presence of a zero-valent Ni species. However, similar nickel species to ACS with a Ni centre have been made, so the diamagnetic mechanism is not an implausible hypothesis.

References

{{Portal bar, Biology, border=no EC 2.3.1 Enzymes of unknown structure