Accession Of Crimea To Russia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

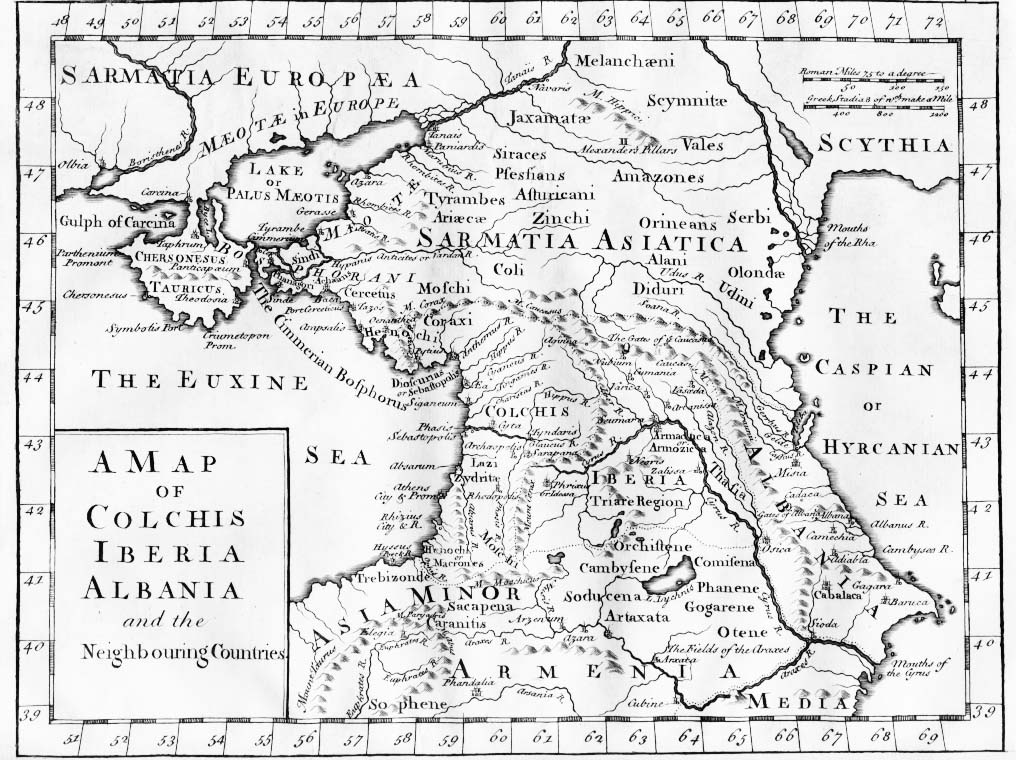

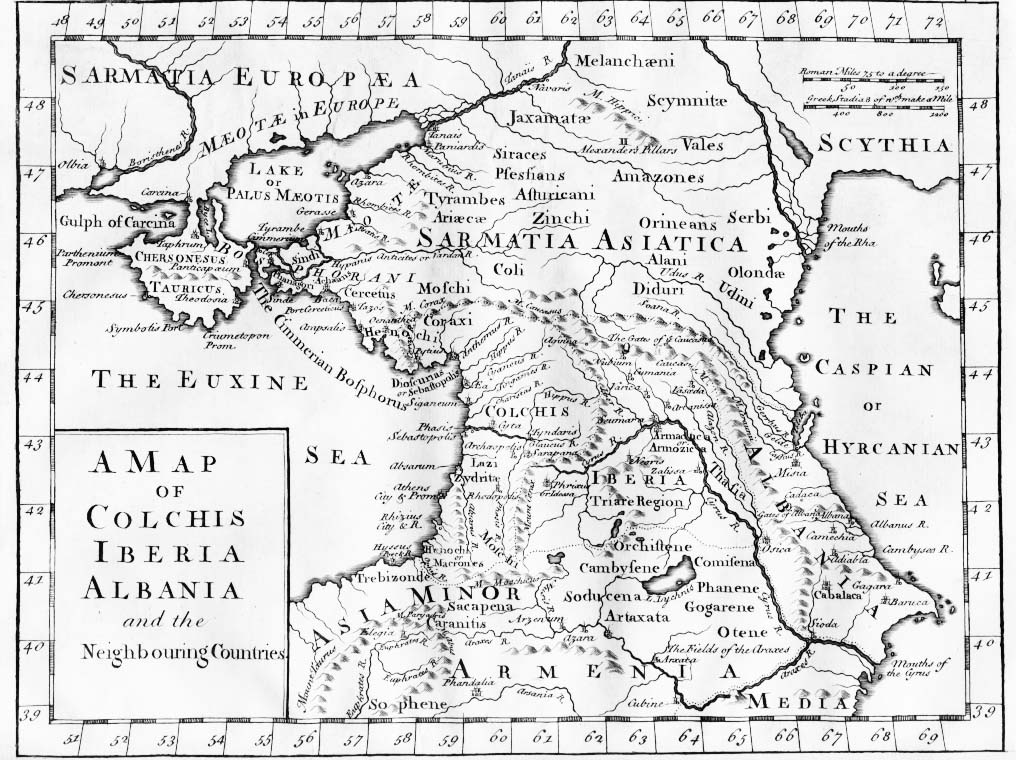

The recorded history of the Crimean Peninsula, historically known as ''Tauris'', ''Taurica'' ( gr, Ταυρική or Ταυρικά), and the ''Tauric Chersonese'' ( gr, Χερσόνησος Ταυρική, "Tauric Peninsula"), begins around the 5th century BCE when several Greek colonies were established along its coast, the most important of which was

The recorded history of the Crimean Peninsula, historically known as ''Tauris'', ''Taurica'' ( gr, Ταυρική or Ταυρικά), and the ''Tauric Chersonese'' ( gr, Χερσόνησος Ταυρική, "Tauric Peninsula"), begins around the 5th century BCE when several Greek colonies were established along its coast, the most important of which was

Greek city-states began establishing colonies along the Black Sea coast of Crimea in the 7th or 6th century BC. Theodosia and

Greek city-states began establishing colonies along the Black Sea coast of Crimea in the 7th or 6th century BC. Theodosia and

The overseas territories of Trebizond, Perateia, had already been subjected to pressure from the Genoese and Kipchaks by the time Alexios I of Trebizond died in 1222, before the Mongol invasions began its western sweep through Volga Bulgaria in 1223.

Kiev lost its hold on the Crimean interior in the early 13th century due to the Mongol invasions. In the summer of 1238 Batu Khan devastated the Crimean peninsula and pacified Mordovia, reaching Kiev by 1240. The Crimean interior came under the control of the Turco-Mongol Golden Horde from 1239 to 1441. The name ''Crimea'' (via Italian, from Turkic ''Qirim'') originates as the name of the provincial capital of the Golden Horde, the city now known as

The overseas territories of Trebizond, Perateia, had already been subjected to pressure from the Genoese and Kipchaks by the time Alexios I of Trebizond died in 1222, before the Mongol invasions began its western sweep through Volga Bulgaria in 1223.

Kiev lost its hold on the Crimean interior in the early 13th century due to the Mongol invasions. In the summer of 1238 Batu Khan devastated the Crimean peninsula and pacified Mordovia, reaching Kiev by 1240. The Crimean interior came under the control of the Turco-Mongol Golden Horde from 1239 to 1441. The name ''Crimea'' (via Italian, from Turkic ''Qirim'') originates as the name of the provincial capital of the Golden Horde, the city now known as

On 28 December 1783 the Ottoman Empire signed an agreement negotiated by the Russian diplomat Bulgakov that recognised the loss of Crimea and other territories that had been held by the Khanate. Crimea went through a number of administrative reforms after Russian annexation, first as the Taurida Oblast in 1784 but in 1796 it was divided into two counties and attached it to the

On 28 December 1783 the Ottoman Empire signed an agreement negotiated by the Russian diplomat Bulgakov that recognised the loss of Crimea and other territories that had been held by the Khanate. Crimea went through a number of administrative reforms after Russian annexation, first as the Taurida Oblast in 1784 but in 1796 it was divided into two counties and attached it to the

Between 56,000 and 150,000 of the Whites were murdered as part of the

Between 56,000 and 150,000 of the Whites were murdered as part of the

Crimea became part of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic on 18 October 1921 as the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, which became part of the Soviet Union in 1922, with a degree of autonomy and run as a Crimean Tatar enclave.

However, this did not protect the Crimean Tatars, who constituted about 25% of the Crimean population, from Joseph Stalin's repressions of the 1930s. The Greeks were another cultural group that suffered. Their lands were lost during the process of collectivisation, in which farmers were not compensated with wages. Schools which taught Greek were closed and Greek literature was destroyed, because the Soviets considered the Greeks as "counter-revolutionary" with their links to capitalist state Greece, and their independent culture.

From 1923 until 1944 there was an effort to create Jewish settlements in Crimea. There were two attempts to establish

Crimea became part of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic on 18 October 1921 as the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, which became part of the Soviet Union in 1922, with a degree of autonomy and run as a Crimean Tatar enclave.

However, this did not protect the Crimean Tatars, who constituted about 25% of the Crimean population, from Joseph Stalin's repressions of the 1930s. The Greeks were another cultural group that suffered. Their lands were lost during the process of collectivisation, in which farmers were not compensated with wages. Schools which taught Greek were closed and Greek literature was destroyed, because the Soviets considered the Greeks as "counter-revolutionary" with their links to capitalist state Greece, and their independent culture.

From 1923 until 1944 there was an effort to create Jewish settlements in Crimea. There were two attempts to establish

With the

With the

. Ukrayinska Pravda. 19 February 2014 At the same time Russian president Vladimir Putin discussed Ukrainian events with security service chiefs remarking that "we must start working on returning Crimea to Russia". On 27 February,

Russia formally incorporated Crimea on 18 March 2014. Following the annexation, Russia escalated its military presence on the peninsula and made

online

* * Kent, Neil (2016). ''Crimea: A History''. Hurst Publishers. . * * Kirimli, Hakan. ''National Movements and National Identity Among the Crimean Tatars (1905 - 1916)'' (E.J. Brill. 1996) * Magocsi, Paul Robert (2014). ''This Blessed Land: Crimea and the Crimean Tatars''. University of Toronto Press. . * Milner, Thomas. ''The Crimea: Its Ancient and Modern History: the Khans, the Sultans, and the Czars. ''Longman, 1855

online

* O'Neill, Kelly. ''Claiming Crimea: A History of Catherine the Great's Southern Empire'' (Yale University Press, 2017). * Ozhiganov, Edward. "The Crimean Republic: Rivalries for Control." in ''Managing Conflict in the Former Soviet Union: Russian and American Perspectives'' (MIT Press. 1997). pp. 83–137. * Pleshakov, Constantine. ''The Crimean Nexus: Putin's War and the Clash of Civilizations'' (Yale University Press, 2017). * Sasse, Gwendolyn. ''The Crimea Question: Identity, Transition, and Conflict'' (2007) * * , recent developments * Williams, Brian Glyn. ''The Crimean Tatars: The Diaspora Experience and the Forging of a Nation'' (Brill 2001

online

excerpt and text search

Historical footage of Crimea, 1918

filmportal.de

On the role of Crimea in the Russian discourse

i

The Crimean Archipelago: A Multimedia Dossier

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Crimea

The recorded history of the Crimean Peninsula, historically known as ''Tauris'', ''Taurica'' ( gr, Ταυρική or Ταυρικά), and the ''Tauric Chersonese'' ( gr, Χερσόνησος Ταυρική, "Tauric Peninsula"), begins around the 5th century BCE when several Greek colonies were established along its coast, the most important of which was

The recorded history of the Crimean Peninsula, historically known as ''Tauris'', ''Taurica'' ( gr, Ταυρική or Ταυρικά), and the ''Tauric Chersonese'' ( gr, Χερσόνησος Ταυρική, "Tauric Peninsula"), begins around the 5th century BCE when several Greek colonies were established along its coast, the most important of which was Chersonesos

Chersonesus ( grc, Χερσόνησος, Khersónēsos; la, Chersonesus; modern Russian and Ukrainian: Херсоне́с, ''Khersones''; also rendered as ''Chersonese'', ''Chersonesos'', contracted in medieval Greek to Cherson Χερσών; ...

near modern day Sevastopol, with Scythians and Tauri

The Tauri (; in Ancient Greek), or Taurians, also Scythotauri, Tauri Scythae, Tauroscythae (Pliny, ''H. N.'' 4.85) were an ancient people settled on the southern coast of the Crimea peninsula, inhabiting the Crimean Mountains in the 1st millenni ...

in the hinterland to the north. The southern coast gradually consolidated into the Bosporan Kingdom which was annexed by Pontus and then became a client kingdom

A client state, in international relations, is a State (polity), state that is economically, politically, and/or militarily subordinate to another more powerful state (called the "controlling state"). A client state may variously be described as ...

of Rome (63 BCE – 341 AD). The south coast remained Greek in culture for almost two thousand years including under Roman successor states, the Byzantine Empire (341 AD – 1204 AD), the Empire of Trebizond

The Empire of Trebizond, or Trapezuntine Empire, was a monarchy and one of three successor rump states of the Byzantine Empire, along with the Despotate of the Morea and the Principality of Theodoro, that flourished during the 13th through to t ...

(1204 AD – 1461 AD), and the independent Principality of Theodoro (ended 1475 AD). In the 13th century, some Crimean port cities were controlled by the Venetians and by the Genovese

Genovese is an Italian surname meaning, properly, someone from Genoa. Its Italian plural form '' Genovesi'' has also developed into a surname.

People

* Alfred Genovese (1931–2011), American oboist

* Alfredo Genovese (born 1964), Argentine ar ...

, but the interior was much less stable, enduring a long series of conquests and invasions. In the medieval period, it was partially conquered by Kievan Rus' whose prince Vladimir the Great was baptised at Sevastopol, which marked the beginning of the Christianization of Kievan Rus'. During the Mongol invasion of Europe, the north and centre of Crimea fell to the Mongol Golden Horde, and in the 1440s the Crimean Khanate formed out of the collapse of the horde but quite rapidly itself became subject to the Ottoman Empire, which also conquered the coastal areas which had kept independent of the Khanate. A major source of prosperity in these times was frequent raids into Russia for slaves.

In 1774, the Ottoman Empire was defeated by Catherine the Great

, en, Catherine Alexeievna Romanova, link=yes

, house =

, father = Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst

, mother = Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp

, birth_date =

, birth_name = Princess Sophie of Anhal ...

. After two centuries of conflict, the Russian fleet had destroyed the Ottoman navy and the Russian army

The Russian Ground Forces (russian: Сухопутные войска �В Sukhoputnyye voyska V, also known as the Russian Army (, ), are the Army, land forces of the Russian Armed Forces.

The primary responsibilities of the Russian Gro ...

had inflicted heavy defeats on the Ottoman land forces. The ensuing Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca forced the Sublime Porte to recognize the Tatars of the Crimea as politically independent. Catherine the Great's incorporation of the Crimea in 1783 from the defeated Ottoman Empire into the Russian Empire increased Russia's power in the Black Sea area. The Crimea was the first Muslim territory to slip from the sultan's suzerainty. The Ottoman Empire's frontiers would gradually shrink, and Russia would proceed to push her frontier westwards to the Dniester. From 1853 to 1856, the strategic position of the peninsula in controlling the Black Sea meant that it was the site of the principal engagements of the Crimean War, where Russia lost to a French-led alliance.

During the Russian Civil War, Crimea changed hands many times and was where Wrangel's anti-Bolshevik White Army made their last stand in 1920, with tens of thousands of those who remained being murdered as part of the Red Terror

The Red Terror (russian: Красный террор, krasnyj terror) in Soviet Russia was a campaign of political repression and executions carried out by the Bolsheviks, chiefly through the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police. It started in lat ...

. In 1921, the Crimean ASSR was created as an autonomous republic of the Russian SFSR. During World War II, Crimea was occupied by Germany until 1944. The ASSR was downgraded to an oblast in 1945 following the deportation of the Crimean Tatars, and in 1954, Crimea was transferred to the Ukrainian SSR on the 300th anniversary of the Treaty of Pereyaslav

The Pereiaslav AgreementPereyaslav Agreement

. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union

The dissolution of the Soviet Union, also negatively connoted as rus, Разва́л Сове́тского Сою́за, r=Razvál Sovétskogo Soyúza, ''Ruining of the Soviet Union''. was the process of internal disintegration within the Sov ...

, the Republic of Crimea was formed in 1992, although the republic was abolished in 1995 with the Autonomous Republic of Crimea

The Autonomous Republic of Crimea, commonly known as Crimea, is a de jure autonomous republic of Ukraine encompassing most of Crimea that was annexed by Russia in 2014. The Autonomous Republic of Crimea occupies most of the peninsula,

established firmly under Ukrainian authority and Sevastopol being administered as a city with special status

City with special status ( uk, місто зі спеціальним статусом, misto zi spetsial'nym statusom), formerly "city of republican subordinance", is a type of first-level administrative division of Ukraine. Kyiv and Sevastopol ...

. A 1997 treaty partitioned the Soviet Black Sea Fleet

Chernomorskiy flot

, image = Great emblem of the Black Sea fleet.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Great emblem of the Black Sea fleet

, dates = May 13, ...

allowing Russia to continue basing its fleet in Sevastopol with the lease extended

Extension, extend or extended may refer to:

Mathematics

Logic or set theory

* Axiom of extensionality

* Extensible cardinal

* Extension (model theory)

* Extension (predicate logic), the set of tuples of values that satisfy the predicate

* Exte ...

in 2010.

Crimea's status is disputed. In 2014 Crimea saw intense demonstrations against the removal of the Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych culminating in pro-Russian forces occupying strategic points in Crimea and the Republic of Crimea declared independence from Ukraine following a disputed referendum supporting reunification. Russia then formally annexed Crimea although most countries recognise Crimea as part of Ukraine.

Prehistory

Archaeological evidence of human settlement in Crimea dates back to theMiddle Paleolithic

The Middle Paleolithic (or Middle Palaeolithic) is the second subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age as it is understood in Europe, Africa and Asia. The term Middle Stone Age is used as an equivalent or a synonym for the Middle Paleoli ...

. Neanderthal remains found at Kiyik-Koba Cave have been dated to about 80,000 BP. Late Neanderthal occupations have also been found at Starosele (c. 46,000 BP) and Buran Kaya III (c. 30,000 BP).

Archaeologists have found some of the earliest anatomically modern human remains in Europe in the Buran-Kaya caves in the Crimean Mountains

The Crimean Mountains ( uk, Кримські гори, translit. ''Krymski hory''; russian: Крымские горы, translit. ''Krymskie gory''; crh, Qırım dağları) are a range of mountains running parallel to the south-eastern coast o ...

(east of Simferopol). The fossils are about 32,000 years old, with the artifacts linked to the Gravettian culture.

During the Last Glacial Maximum

The Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), also referred to as the Late Glacial Maximum, was the most recent time during the Last Glacial Period that ice sheets were at their greatest extent.

Ice sheets covered much of Northern North America, Northern Eur ...

, along with the northern coast of the Black Sea in general, Crimea was an important refuge from which north-central Europe was re-populated after the end of the Ice Age. The East European Plain during this time was generally occupied by periglacial loess

Loess (, ; from german: Löss ) is a clastic, predominantly silt-sized sediment that is formed by the accumulation of wind-blown dust. Ten percent of Earth's land area is covered by loess or similar deposits.

Loess is a periglacial or aeolian ...

-steppe

In physical geography, a steppe () is an ecoregion characterized by grassland plains without trees apart from those near rivers and lakes.

Steppe biomes may include:

* the montane grasslands and shrublands biome

* the temperate grasslands, ...

environments, although the climate was slightly warmer during several brief interstadials and began to warm significantly after the beginning of the Late Glacial Maximum

The Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), also referred to as the Late Glacial Maximum, was the most recent time during the Last Glacial Period that ice sheets were at their greatest extent.

Ice sheets covered much of Northern North America, Northern Eur ...

. Human site occupation density was relatively high in the Crimean region and increased as early as c. 16,000 years before the present.

Proponents of the Black Sea deluge hypothesis believe Crimea did not become a peninsula until relatively recently, with the rising of the Black Sea level in the 6th millennium BC.

The beginning of the Neolithic in Crimea is not associated with agriculture, but instead with the beginning of pottery production, changes in flint tool-making technologies, and local domestication of pigs. The earliest evidence of domesticated wheat in the Crimean peninsula is from the Chalcolithic Ardych-Burun site, dating to the middle of the 4th millennium BC

By the 3rd millennium BC, Crimea had been reached by the Yamna or "pit grave" culture, assumed to correspond to a late phase of Proto-Indo-European culture in the Kurgan hypothesis.

Antiquity

Tauri and Scythians

Early Iron Age Crimea was settled by two groups separated by theCrimean Mountains

The Crimean Mountains ( uk, Кримські гори, translit. ''Krymski hory''; russian: Крымские горы, translit. ''Krymskie gory''; crh, Qırım dağları) are a range of mountains running parallel to the south-eastern coast o ...

, the Tauri

The Tauri (; in Ancient Greek), or Taurians, also Scythotauri, Tauri Scythae, Tauroscythae (Pliny, ''H. N.'' 4.85) were an ancient people settled on the southern coast of the Crimea peninsula, inhabiting the Crimean Mountains in the 1st millenni ...

to the south and the Iranic Scythians in the north.

Taurians intermixed with the Scythians starting from the end of 3rd century BC were mentioned as "Tauroscythians" and "Scythotaurians" in the works of ancient Greek writers. In Geographica

The ''Geographica'' (Ancient Greek: Γεωγραφικά ''Geōgraphiká''), or ''Geography'', is an encyclopedia of geographical knowledge, consisting of 17 'books', written in Ancient Greek, Greek and attributed to Strabo, an educated citizen ...

, Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

refers to the Tauri as a Scythian tribe. However, Herodotus states that the Tauri tribes were geographically inhabited by the Scythians, but they are not Scythians. Also, the Taurians inspired the Greek myths

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the origin and nature of the world, the lives and activities of de ...

of Iphigenia and Orestes.

The Greeks, who eventually established colonies in Crimea during the Archaic Period, regarded the Tauri as a savage, warlike people. Even after centuries of Greek and Roman settlement, the Tauri were not pacified and continued to engage in piracy on the Black Sea. By the 2nd century BC they had become subject-allies of the Scythian king Scilurus.

The Crimean Peninsula north of the Crimean Mountains was occupied by Scythian tribes. Their center was the city of Scythian Neapolis on the outskirts of present-day Simferopol. The town ruled over a small kingdom covering the lands between the lower Dnieper River and northern Crimea. In the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC, Scythian Neapolis was a city "with a mixed Scythian-Greek population, strong defensive walls and large public buildings constructed using the orders of Greek architecture". The city was eventually destroyed in the mid-3rd century AD by the Goths.

Greek settlement

The ancient Greeks were the first to name the region ''Taurica'' after theTauri

The Tauri (; in Ancient Greek), or Taurians, also Scythotauri, Tauri Scythae, Tauroscythae (Pliny, ''H. N.'' 4.85) were an ancient people settled on the southern coast of the Crimea peninsula, inhabiting the Crimean Mountains in the 1st millenni ...

. As the Tauri inhabited only the mountainous regions of southern Crimea, the name Taurica was originally used only for this southern part, but was later extended to refer to the whole peninsula.

Panticapaeum

Panticapaeum ( grc-gre, Παντικάπαιον , from Scythian , "fish-path") was an ancient Greek city on the eastern shore of Crimea, which the Greeks called Taurica. The city lay on the western side of the Cimmerian Bosporus, and was found ...

were established by Milesians. In the 5th century BC, Dorians from Heraclea Pontica founded the sea port of Chersonesos

Chersonesus ( grc, Χερσόνησος, Khersónēsos; la, Chersonesus; modern Russian and Ukrainian: Херсоне́с, ''Khersones''; also rendered as ''Chersonese'', ''Chersonesos'', contracted in medieval Greek to Cherson Χερσών; ...

(in modern Sevastopol).

The Persian Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

under Darius I

Darius I ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his ...

expanded to Crimea as part of his campaigns against the Scythians in 513 BCE.

In 438 BC, the Archon (ruler) of Panticapaeum assumed the title of the King of Cimmerian Bosporus, a state that maintained close relations with Athens, supplying the city with wheat, honey and other commodities. The last of that line of kings, Paerisades V, being hard-pressed by the Scythians, put himself under the protection of Mithridates VI, the king of Pontus, in 114 BC. After the death of this sovereign, his son, Pharnaces II

Pharnaces II of Pontus ( grc-gre, Φαρνάκης; about 97–47 BC) was the king of the Bosporan Kingdom and Kingdom of Pontus until his death. He was a monarch of Persian and Greek ancestry. He was the youngest child born to King Mithridat ...

, was invested by Pompey with the Kingdom of the Cimmerian Bosporus

The Bosporan Kingdom, also known as the Kingdom of the Cimmerian Bosporus (, ''Vasíleio toú Kimmerikoú Vospórou''), was an ancient Greco-Scythian state located in eastern Crimea and the Taman Peninsula on the shores of the Cimmerian Bosporus, ...

in 63 BC as a reward for the assistance rendered to the Romans in their war against his father. In 15 BC, it was once again restored to the king of Pontus, but from then ranked as a tributary state of Rome.

Roman Empire

In the 2nd century BC, the eastern part of Taurica became part of the Bosporan Kingdom, before becoming a client kingdom of the Roman Empire in the 1st century BC. During the AD 1st, 2nd and 3rd centuries, Taurica was host to Roman legions and colonists inCharax, Crimea

Charax ( grc, Χάραξ, gen.: Χάρακος) is the largest Roman military settlement excavated in the Crimea. It was sited on a four-hectare area at the western ridge of Ai-Todor, close to the modern tourist attraction of Swallow's Nest.

The ...

. The Charax colony was founded under Vespasian with the intention of protecting Chersonesos

Chersonesus ( grc, Χερσόνησος, Khersónēsos; la, Chersonesus; modern Russian and Ukrainian: Херсоне́с, ''Khersones''; also rendered as ''Chersonese'', ''Chersonesos'', contracted in medieval Greek to Cherson Χερσών; ...

and other Bosporean trade emporiums from the Scythians. The Roman colony was protected by a vexillatio of the Legio I Italica

Legio I Italica ("First Italian Legion") was a Roman legion, legion of the Imperial Roman army founded by emperor Nero on September 22, 66 (the date is attested by an inscription). The epithet ''Italica'' is a reference to the Italian origin ...

; it also hosted a detachment of the Legio XI Claudia at the end of the 2nd century. The camp was abandoned by the Romans in the mid-3rd century. This de facto province would have been controlled by the legatus of one of the Legions stationed in Charax.

Throughout the later centuries, Crimea was invaded or occupied successively by the Goths (AD 250), the Huns (376), the Bulgars

The Bulgars (also Bulghars, Bulgari, Bolgars, Bolghars, Bolgari, Proto-Bulgarians) were Turkic semi-nomadic warrior tribes that flourished in the Pontic–Caspian steppe and the Volga region during the 7th century. They became known as nomad ...

(4th–8th century), the Khazars (8th century).

Crimean Gothic, an East Germanic language, was spoken by the Crimean Goths in some isolated locations in Crimea until the late 18th century.

Middle Ages

Rus' and Byzantium

In the 9th century CE, Byzantium established theTheme of Cherson

The Theme of Cherson ( el, , ''thema Chersōnos''), originally and formally called the Klimata (Greek: ) and Korsun', was a Byzantine theme (a military-civilian province) located in the southern Crimea, headquartered at Cherson.

The theme was ...

to defend against incursions by the Rus' Khaganate. The Crimean peninsula from this time was contested between Byzantium, Rus' and Khazaria. The area remained the site of overlapping interests and contact between the early medieval Slavic, Turkic and Greek spheres.

It became a center of slave trade. Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

were sold to Byzantium and other places in Anatolia and the Middle East during this period.

In the mid-10th century, the eastern area of Crimea was conquered by Prince Sviatoslav I of Kiev

; (943 – 26 March 972), also spelled Svyatoslav, was Grand Prince of Kiev famous for his persistent campaigns in the east and south, which precipitated the collapse of two great powers of Eastern Europe, Khazars, Khazaria and the First Bulgarian E ...

and became part of the Kievan Rus' principality of Tmutarakan

Tmutarakan ( rus, Тмутарака́нь, p=tmʊtərɐˈkanʲ, ; uk, Тмуторокань, Tmutorokan) was a medieval Kievan Rus' principality and trading town that controlled the Cimmerian Bosporus, the passage from the Black Sea to the Sea ...

. The peninsula was wrested from the Byzantines by the Kievan Rus' in the 10th century; a major Byzantine outpost, Chersonesus was taken in 988 CE. A year later, Grand Prince Vladimir of Kiev accepted the hand of Emperor Basil II's sister Anna

Anna may refer to:

People Surname and given name

* Anna (name)

Mononym

* Anna the Prophetess, in the Gospel of Luke

* Anna (wife of Artabasdos) (fl. 715–773)

* Anna (daughter of Boris I) (9th–10th century)

* Anna (Anisia) (fl. 1218 to 1221)

...

in marriage, and was baptized

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost ...

by the local Byzantine priest at Chersonesus, thus marking the entry of Rus' (later Russia) into the Christian world. Chersonesus Cathedral marks the location of this historic event.

During the collapse of the Byzantine state some cities fell to its creditor the Republic of Genoa who also conquered cities controlled by its rival the Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

. During the entirety of this period, the urban areas were Greek-speaking and eastern Christian.

The Crimean Steppe

Throughout the ancient and medieval period the interior and north of Crimea was occupied by a changing cast of invadingsteppe nomads

The Eurasian nomads were a large group of nomadic peoples from the Eurasian Steppe, who often appear in history as invaders of Europe, Western Asia, Central Asia, Eastern Asia, and South Asia.

A nomad is a member of people having no permanent ...

, such as the Tauri

The Tauri (; in Ancient Greek), or Taurians, also Scythotauri, Tauri Scythae, Tauroscythae (Pliny, ''H. N.'' 4.85) were an ancient people settled on the southern coast of the Crimea peninsula, inhabiting the Crimean Mountains in the 1st millenni ...

, Cimmerians, Scythians, Sarmatians, Crimean Goths, Alans, Bulgars

The Bulgars (also Bulghars, Bulgari, Bolgars, Bolghars, Bolgari, Proto-Bulgarians) were Turkic semi-nomadic warrior tribes that flourished in the Pontic–Caspian steppe and the Volga region during the 7th century. They became known as nomad ...

, Huns, Khazars, Kipchaks

The Kipchaks or Qipchaks, also known as Kipchak Turks or Polovtsians, were a Turkic nomadic people and confederation that existed in the Middle Ages, inhabiting parts of the Eurasian Steppe. First mentioned in the 8th century as part of the Se ...

and Mongols.

The Bosporan Kingdom had exercised some control of the majority of the peninsula at the height of its power, with Kievan Rus' also having some control of the interior of Crimea after the tenth century.

Mongol invasion and later medieval period

The overseas territories of Trebizond, Perateia, had already been subjected to pressure from the Genoese and Kipchaks by the time Alexios I of Trebizond died in 1222, before the Mongol invasions began its western sweep through Volga Bulgaria in 1223.

Kiev lost its hold on the Crimean interior in the early 13th century due to the Mongol invasions. In the summer of 1238 Batu Khan devastated the Crimean peninsula and pacified Mordovia, reaching Kiev by 1240. The Crimean interior came under the control of the Turco-Mongol Golden Horde from 1239 to 1441. The name ''Crimea'' (via Italian, from Turkic ''Qirim'') originates as the name of the provincial capital of the Golden Horde, the city now known as

The overseas territories of Trebizond, Perateia, had already been subjected to pressure from the Genoese and Kipchaks by the time Alexios I of Trebizond died in 1222, before the Mongol invasions began its western sweep through Volga Bulgaria in 1223.

Kiev lost its hold on the Crimean interior in the early 13th century due to the Mongol invasions. In the summer of 1238 Batu Khan devastated the Crimean peninsula and pacified Mordovia, reaching Kiev by 1240. The Crimean interior came under the control of the Turco-Mongol Golden Horde from 1239 to 1441. The name ''Crimea'' (via Italian, from Turkic ''Qirim'') originates as the name of the provincial capital of the Golden Horde, the city now known as Staryi Krym

Staryi Krym (russian: Старый Крым; uk, Старий Крим; crh, Eski Qırım, italic=yes; in all three languages) is a small historical town and former bishopric in Kirovske Raion of Crimea, Ukraine. It has been illegally occupie ...

.

Trebizond's Perateia soon became the Principality of Theodoro and Genoese Gazaria

Gazaria (also Cassaria, Cacsarea, and Gasaria) was the name given to the colonial possessions of the Republic of Genoa in Crimea and around the Black Sea coasts in the territories of the modern regions of Russia, Ukraine and Romania, from the m ...

, respectively sharing control of the south of Crimea until the Ottoman intervention of 1475.

In the 13th century the Republic of Genoa seized the settlements that their rivals, the Venetians, had built along the Crimean coast and established themselves at Cembalo (present-day Balaklava), Soldaia

Sudak (Ukrainian & Russian: Судак; crh, Sudaq; gr, Σουγδαία; sometimes spelled Sudac or Sudagh) is a town, multiple former Eastern Orthodox bishopric and double Latin Catholic titular see. It is of regional significance in Crimea, ...

(Sudak), Cherco (Kerch) and Caffa (Feodosiya), gaining control of the Crimean economy and the Black Sea commerce for two centuries. Genoa and its colonies fought a series of wars with the Mongol states between the 13th and 15th centuries.

In 1346 the Golden Horde army besieging Genoese Kaffa (present-day Feodosiya) catapulted the bodies of Mongol warriors who had died of plague

Plague or The Plague may refer to:

Agriculture, fauna, and medicine

*Plague (disease), a disease caused by ''Yersinia pestis''

* An epidemic of infectious disease (medical or agricultural)

* A pandemic caused by such a disease

* A swarm of pes ...

over the walls of the city. Historians have speculated that Genoese refugees from this engagement may have brought the Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

to Western Europe.

Crimean Khanate (1443–1783)

After Timur destroyed a Mongol Golden Horde army in 1399, the Crimean Tatars founded an independent Crimean Khanate under Hacı I Giray (a descendant ofGenghis Khan

''Chinggis Khaan'' ͡ʃʰiŋɡɪs xaːŋbr />Mongol script: ''Chinggis Qa(gh)an/ Chinggis Khagan''

, birth_name = Temüjin

, successor = Tolui (as regent)Ögedei Khan

, spouse =

, issue =

, house = Borjigin

, ...

) by 1443. Hacı I Giray and his successors reigned first at Qırq Yer, then - from the beginning of the 15th century - at Bakhchisaray.

The Crimean Tatars controlled the steppes that stretched from the Kuban

Kuban (Russian language, Russian and Ukrainian language, Ukrainian: Кубань; ady, Пшызэ) is a historical and geographical region of Southern Russia surrounding the Kuban River, on the Black Sea between the Pontic–Caspian steppe, ...

to the Dniester River

The Dniester, ; rus, Дне́стр, links=1, Dnéstr, ˈdⁿʲestr; ro, Nistru; grc, Τύρᾱς, Tyrās, ; la, Tyrās, la, Danaster, label=none, ) ( ,) is a transboundary river in Eastern Europe. It runs first through Ukraine and th ...

, however, they were unable to take control of the commercial Genoese towns in the Crimea. After the Crimean Tatars asked for help from the Ottomans

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

, an Ottoman invasion of the Genoese towns led by Gedik Ahmed Pasha in 1475 brought Kaffa and the other trading towns under their control.

After the capture of the Genoese towns, the Ottoman Sultan held Khan Meñli I Giray captive, later releasing him in return for accepting Ottoman suzerainty over the Crimean Khans and allowing them rule as tributary princes of the Ottoman Empire. However, the Crimean Khans still had a large amount of autonomy from the Ottoman Empire, and followed the rules they thought best for them.

Crimean Tatars introduced the practice of raids into Ukrainian lands (the Wild Fields), in which they captured slaves

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

for sale. For example, from 1450 to 1586, eighty-six Tatar raids were recorded, and from 1600 to 1647, seventy. In the 1570s close to 20,000 slaves a year went on sale in Kaffa.

Slaves and freedmen formed approximately 75% of the Crimean population. In 1769 a last major Tatar raid, which took place during the Russo-Turkish War of 1768-1774, saw the capture of 20,000 slaves.

Tatar society

The Crimean Tatars as an ethnic group dominated the Crimean Khanate from the 15th to the 18th centuries. They descend from a complicated mixture of Turkic peoples who settled in the Crimea from the 8th century, presumably also absorbing remnants of the Crimean Goths and the Genoese. Linguistically, the Crimean Tatars are related to the Khazars, who invaded the Crimea in the mid-8th century; theCrimean Tatar language

Crimean Tatar () also called Crimean (), is a Kipchak Turkic language spoken in Crimea and the Crimean Tatar diasporas of Uzbekistan, Turkey, Romania, and Bulgaria, as well as small communities in the United States and Canada. It should n ...

forms part of the Kipchak or Northwestern branch of the Turkic languages, although it shows substantial Oghuz influence due to historical Ottoman Turkish presence in the Crimea.

A small enclave of Crimean Karaites, a people of Jewish descent practising Karaism who later adopted a Turkic language, formed in the 13th century. It existed among the Muslim Crimean Tatars, primarily in the mountainous Çufut Qale

__NOTOC__

Chufut-Kale ( crh, Çufut Qale, italic=yes ; Russian language, Russian and Ukrainian language, Ukrainian: Чуфут-Кале - ''Chufut-Kale''; Karaim language, Karaim: Кала - קלעה - ''Kala'') is a medieval city-fortress in the C ...

area.

Cossack incursions

In 1553–1554Cossack

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or ...

Hetman Dmytro Vyshnevetsky (in office: 1550-1557) gathered together groups of Cossacks and constructed a fort designed to obstruct Tatar raids into Ukraine. With this action, he founded the Zaporozhian Sich, with which he would launch a series of attacks on the Crimean Peninsula and the Ottoman Turks.

In 1774, the Ottoman Empire was defeated by Catherine the Great

, en, Catherine Alexeievna Romanova, link=yes

, house =

, father = Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst

, mother = Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp

, birth_date =

, birth_name = Princess Sophie of Anhal ...

. After two centuries of conflict, the Russian fleet had destroyed the Ottoman navy and the Russian army

The Russian Ground Forces (russian: Сухопутные войска �В Sukhoputnyye voyska V, also known as the Russian Army (, ), are the Army, land forces of the Russian Armed Forces.

The primary responsibilities of the Russian Gro ...

had inflicted heavy defeats on the Ottoman land forces. The ensuing Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca forced the Sublime Porte to recognize the Tatars of the Crimea as politically independent, meaning that the Crimean Khans fell under Russian influence with the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca. but did suffered a gradual internal collapse, particularly after a pogrom created a Russian aided exodus of Christian subjects who were overwhelmingly among the urban classes and created cities such as Mariupol. Catherine the Great's later incorporation of the Crimea in 1783 into the Russian Empire increased Russia's power in the Black Sea area. The Crimea was the first Muslim territory to slip from the sultan's suzerainty. The Ottoman Empire's frontiers would gradually shrink, and Russia would proceed to push her frontier westwards to the Dniester.

Russian Empire (1783–1917)

On 28 December 1783 the Ottoman Empire signed an agreement negotiated by the Russian diplomat Bulgakov that recognised the loss of Crimea and other territories that had been held by the Khanate. Crimea went through a number of administrative reforms after Russian annexation, first as the Taurida Oblast in 1784 but in 1796 it was divided into two counties and attached it to the

On 28 December 1783 the Ottoman Empire signed an agreement negotiated by the Russian diplomat Bulgakov that recognised the loss of Crimea and other territories that had been held by the Khanate. Crimea went through a number of administrative reforms after Russian annexation, first as the Taurida Oblast in 1784 but in 1796 it was divided into two counties and attached it to the Novorossiysk Governorate

Novorossiya Governorate (russian: Новороссийская губерния, Novorossiyskaya guberniya, New Russia Governorate; uk, Новоросійська губернія), was a guberniya, governorate of the Russian Empire in the p ...

, with a new Taurida Governorate established in 1802 with its capital at Simferopol. The governorate included both Crimea as well as larger adjacent areas of the mainland. In 1826 Adam Mickiewicz published his seminal work '' The Crimean Sonnets'' after travelling through the Black Sea Coast.

By the late 19th century, Crimean Tatars continued to form a slight plurality of Crimea's still largely rural population and were the predominant portion of the population in the mountainous area and about half of the steppe population. There were large numbers of Russians concentrated in the Feodosiya district and Ukrainians as well as smaller numbers of Jews (including Krymchaks and Crimean Karaites), Belarusians

, native_name_lang = be

, pop = 9.5–10 million

, image =

, caption =

, popplace = 7.99 million

, region1 =

, pop1 = 600,000–768,000

, region2 =

, pop2 ...

, Turks, Armenians, and Greeks and Roma. Germans and Bulgarians settled in the Crimea at the beginning of the 19th century, receiving a large allotment and fertile land and later wealthy colonists began to buy land, mainly in Perekopsky and Evpatoria uyezds.

Crimean War

The Crimean War (1853–1856), a conflict fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of theFrench Empire

French Empire (french: Empire Français, link=no) may refer to:

* First French Empire, ruled by Napoleon I from 1804 to 1814 and in 1815 and by Napoleon II in 1815, the French state from 1804 to 1814 and in 1815

* Second French Empire, led by Nap ...

, the British Empire, the Ottoman Empire, the Kingdom of Sardinia, and the Duchy of Nassau, was part of a long-running contest between the major European powers for influence over territories of the declining Ottoman Empire. Russia and the Ottoman Empire went to war in October 1853 over Russia's rights to protect Orthodox Christians

Orthodoxy (from Greek: ) is adherence to correct or accepted creeds, especially in religion.

Orthodoxy within Christianity refers to acceptance of the doctrines defined by various creeds and ecumenical councils in Antiquity, but different Churc ...

; to stop Russia's conquests France and Britain entered in March 1854. While some of the war was fought elsewhere, the principal engagements were in Crimea.

The immediate cause of the war involved the rights of Christian minorities in Palestine, which was part of the Ottoman Empire. The French promoted the rights of Roman Catholics, and Russia promoted those of the Eastern Orthodox Church. Longer-term causes involved the decline of the Ottoman Empire, the expansion of the Russian Empire in the preceding Russo-Turkish Wars, and the British and French preference to preserve the Ottoman Empire to maintain the balance of power in the Concert of Europe. It has widely been noted that the causes, in one case involving an argument over a key, had never revealed a "greater confusion of purpose" but led to a war that stood out for its "notoriously incompetent international butchery".

Following action in the Danubian Principalities

The Danubian Principalities ( ro, Principatele Dunărene, sr, Дунавске кнежевине, translit=Dunavske kneževine) was a conventional name given to the Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, which emerged in the early 14th ce ...

and in the Black Sea, allied troops landed in Crimea in September 1854 and besieged the city of Sevastopol, home of the Tsar's Black Sea Fleet and the associated threat of potential Russian penetration into the Mediterranean. After extensive fighting throughout Crimea, the city fell on 9 September 1855. The war ended with a Russian loss in February 1856.

The war devastated much of the economic and social infrastructure of Crimea. The Crimean Tatars had to flee from their homeland ''en masse'', forced by the conditions created by the war, persecution, and land expropriations. Those who survived the trip, famine, and disease, resettled in Dobruja, Anatolia, and other parts of the Ottoman Empire. Finally, the Russian government decided to stop the process, as agriculture began to suffer due to the unattended fertile farmland.

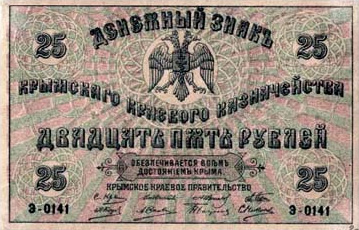

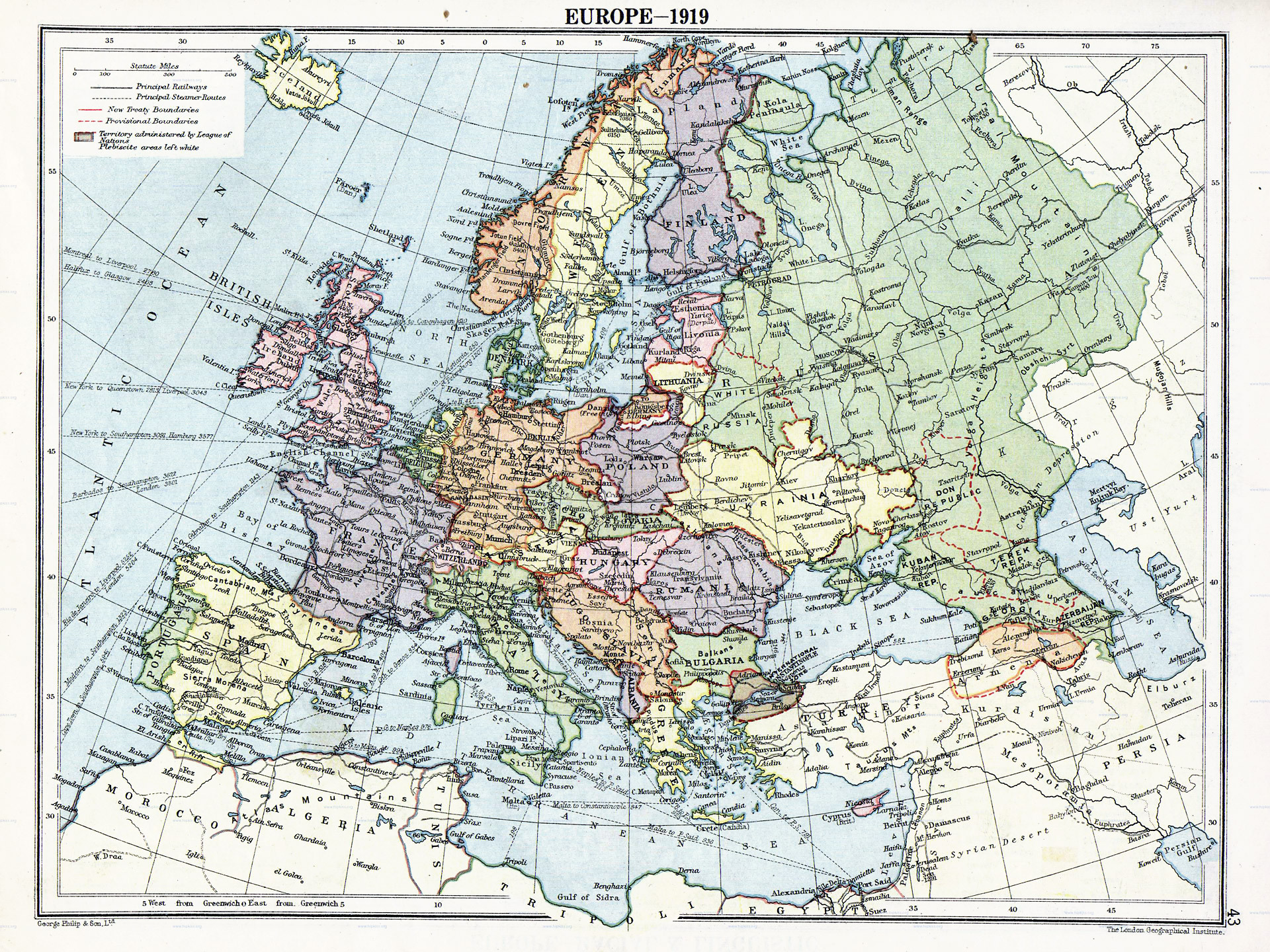

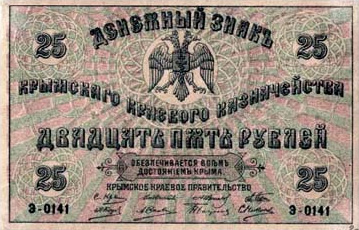

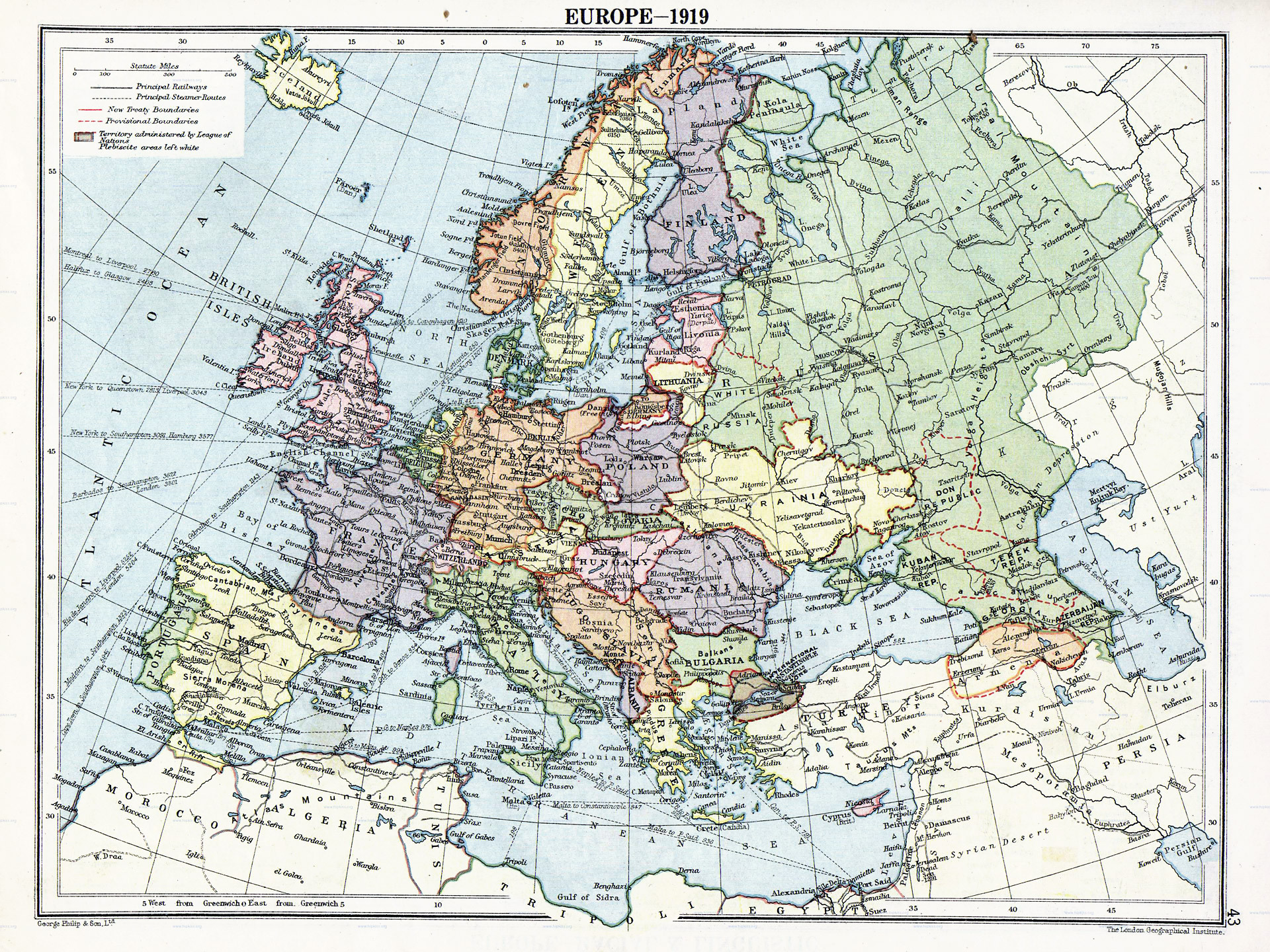

Russian Civil War (1917–1922)

Following the Russian Revolution of 1917, the military and political situation in Crimea was chaotic like that in much of Russia. During the ensuing Russian Civil War, Crimea changed hands numerous times and was for a time a stronghold of the anti-Bolshevik White Army. It was in Crimea that the White Russians led byGeneral Wrangel

Baron Pyotr Nikolayevich Wrangel (russian: Пётр Никола́евич барон Вра́нгель, translit=Pëtr Nikoláevič Vrángel', p=ˈvranɡʲɪlʲ, german: Freiherr Peter Nikolaus von Wrangel; April 25, 1928), also known by his ni ...

made their last stand against Nestor Makhno and the Red Army in 1920. When resistance was crushed, many of the anti-Bolshevik fighters and civilians escaped by ship to Istanbul.

Approximately 50,000 White prisoners of war and civilians were summarily executed by shooting or hanging after the defeat of General Wrangel at the end of 1920. This is considered one of the largest massacres in the Civil War.

Between 56,000 and 150,000 of the Whites were murdered as part of the

Between 56,000 and 150,000 of the Whites were murdered as part of the Red Terror

The Red Terror (russian: Красный террор, krasnyj terror) in Soviet Russia was a campaign of political repression and executions carried out by the Bolsheviks, chiefly through the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police. It started in lat ...

, organized by Béla Kun.

Crimea changed hands several times over the course of the conflict and several political entities were set up on the peninsula. These included:

Soviet Union (1922–1991)

Interbellum

Crimea became part of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic on 18 October 1921 as the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, which became part of the Soviet Union in 1922, with a degree of autonomy and run as a Crimean Tatar enclave.

However, this did not protect the Crimean Tatars, who constituted about 25% of the Crimean population, from Joseph Stalin's repressions of the 1930s. The Greeks were another cultural group that suffered. Their lands were lost during the process of collectivisation, in which farmers were not compensated with wages. Schools which taught Greek were closed and Greek literature was destroyed, because the Soviets considered the Greeks as "counter-revolutionary" with their links to capitalist state Greece, and their independent culture.

From 1923 until 1944 there was an effort to create Jewish settlements in Crimea. There were two attempts to establish

Crimea became part of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic on 18 October 1921 as the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, which became part of the Soviet Union in 1922, with a degree of autonomy and run as a Crimean Tatar enclave.

However, this did not protect the Crimean Tatars, who constituted about 25% of the Crimean population, from Joseph Stalin's repressions of the 1930s. The Greeks were another cultural group that suffered. Their lands were lost during the process of collectivisation, in which farmers were not compensated with wages. Schools which taught Greek were closed and Greek literature was destroyed, because the Soviets considered the Greeks as "counter-revolutionary" with their links to capitalist state Greece, and their independent culture.

From 1923 until 1944 there was an effort to create Jewish settlements in Crimea. There were two attempts to establish Jewish autonomy in Crimea

Jewish autonomy in Crimea was a project in the Soviet Union to create an autonomous region for Jews in the Crimea, Crimean peninsula carried out during the 1920s and 1930s. Following the WWII and the creation of the Jewish Autonomous Oblast i ...

, but both were ultimately unsuccessful.

Crimea experienced two severe famines in the 20th century, the Famine of 1921–1922 and the Holodomor

The Holodomor ( uk, Голодомо́р, Holodomor, ; derived from uk, морити голодом, lit=to kill by starvation, translit=moryty holodom, label=none), also known as the Terror-Famine or the Great Famine, was a man-made famin ...

of 1932–1933. A large Slavic population influx occurred in the 1930s as a result of the Soviet policy of regional development. These demographic changes permanently altered the ethnic balance in the region.

World War II

During World War II, Crimea was a scene of some of the bloodiest battles. The leaders of the Third Reich were anxious to conquer and colonize the fertile and beautiful peninsula as part of their policy of resettling the Germans in Eastern Europe at the expense of the Slavs. In the Crimean campaign, German and Romanian troops suffered heavy casualties in the summer of 1941 as they tried to advance through the narrow Isthmus of Perekop linking Crimea to the Soviet mainland. Once the German army broke through (Operation Trappenjagd

The Battle of the Kerch Peninsula, which commenced with the Soviet Kerch-Feodosia Landing Operation (russian: Керченско-Феодосийская десантная операция, ''Kerchensko-Feodosiyskaya desantnaya operatsiya'') ...

), they occupied most of Crimea, with the exception of the city of Sevastopol, which was besieged and later awarded the honorary title of Hero City Hero City may refer to:

* Hero City (Soviet Union), awarded 1965–1985 to cities now in Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine

* Hero City of Ukraine, awarded 2022

* Hero Cities of Yugoslavia, awarded 1970–1975

* Leningrad Hero City Obelisk, a monument

...

after the war. The Red Army lost over 170,000 men killed or taken prisoner, and three armies (44th, 47th, and 51st) with twenty-one divisions.

Sevastopol held out from October 1941 until 4 July 1942 when the Germans finally captured the city. From 1 September 1942, the peninsula was administered as the ''Generalbezirk Krim'' (general district of Crimea) ''und Teilbezirk'' (and sub-district) ''Taurien'' by the Nazi ''Generalkommissar'' Alfred Eduard Frauenfeld (1898–1977), under the authority of the three consecutive Reichskommissare for the entire Ukraine. In spite of heavy-handed tactics by the Nazis and the assistance of the Romanian

Romanian may refer to:

*anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Romania

**Romanians, an ethnic group

**Romanian language, a Romance language

***Romanian dialects, variants of the Romanian language

**Romanian cuisine, traditional ...

and Italian troops, the Crimean mountains remained an unconquered stronghold of the native resistance (the partisans) until the day when the peninsula was freed from the occupying force.

The Crimean Jews

The history of the Jews in Ukraine dates back over a thousand years; Jewish communities have existed in the territory of Ukraine from the time of the Kievan Rus' (late 9th to mid-13th century). Some of the most important Jewish religious and ...

were targeted for annihilation during the Nazi occupation. According to Yitzhak Arad, "In January 1942 a company of Tatar volunteers was established in Simferopol under the command of '' Einsatzgruppe 11''. This company participated in anti-Jewish manhunts and murder actions in the rural regions." Around 40,000 Crimean Jew were murdered.

The successful Crimean offensive meant that in 1944 Sevastopol came under the control of troops from the Soviet Union. The so-called "City of Russian Glory" once known for its beautiful architecture was entirely destroyed and had to be rebuilt stone by stone. Due to its enormous historical and symbolic meaning for the Russians, it became a priority for Stalin and the Soviet government to have it restored to its former glory within the shortest time possible.

The Crimean port of Yalta hosted the Yalta Conference of Roosevelt, Stalin and Churchill which was later seen as dividing Europe between the Communist and democratic spheres.

Deportation of the Crimean Tatars

On 18 May 1944, the entire population of the Crimean Tatars were forcibly deported in the "Sürgün

Sürgün or verb form sürmek (to displace) was a practice within the Ottoman Empire that entailed the movement of a large group of people from one region to another, often a form of forced migration imposed by state policy or international author ...

" (Crimean Tatar for exile) to Central Asia by Joseph Stalin's Soviet government as a form of collective punishment on the grounds that they allegedly had collaborated with the Nazi occupation forces and formed pro-German Tatar Legion

The Tatar Legions were auxiliary units of the Waffen-SS formed after the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941.

It included:

# Crimean Tatar Legion, comprising Crimean Tatars, Qarays, Nogais

# Volga Tatar Legion, which included also Bashki ...

s. On 26 June of the same year Armenian, Bulgarian

Bulgarian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the country of Bulgaria

* Bulgarians, a South Slavic ethnic group

* Bulgarian language, a Slavic language

* Bulgarian alphabet

* A citizen of Bulgaria, see Demographics of Bulgaria

* Bul ...

and Greek population was also deported to Central Asia, and partially to Ufa and its surroundings in the Ural mountains. A total of more than 230,000 people – about a fifth of the total population of the Crimean Peninsula at that time – were deported, mainly to Uzbekistan. 14,300 Greeks, 12,075 Bulgarians, and about 10,000 Armenians were also expelled. By the end of summer 1944, the ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, and religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making a region ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal, extermination, deportation or population transfer ...

of Crimea was complete. In 1967, the Crimean Tatars were rehabilitated, but they were banned from legally returning to their homeland until the last days of the Soviet Union. The deportation was formally recognized as a genocide by Ukraine and three other countries between 2015 and 2019.

The Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was abolished on 30 June 1945 and transformed into the Crimean Oblast ( province) of the Russian SFSR. A process of De-Tatarization of Crimea was started to remove the memory of the Tartars.

1954 Transfer to Ukraine SSR

On 19 February 1954, the Presidium of theSupreme Soviet

The Supreme Soviet (russian: Верховный Совет, Verkhovny Sovet, Supreme Council) was the common name for the legislative bodies (parliaments) of the Soviet socialist republics (SSR) in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) ...

of the USSR under Nikita Khrushchev issued a decree on the transfer of the Crimean region of the RSFSR to the Ukrainian SSR. The action was attributed to Nikita Khrushchev, then- First Secretary of the Communist Party. This Supreme Soviet Decree states that this transfer was motivated by "the commonality of the economy, the proximity, and close economic and cultural relations between the Crimean region and the Ukrainian SSR". The year 1954 happened to mark the 300th anniversary of the Treaty of Pereyaslav

The Pereiaslav AgreementPereyaslav Agreement

, which was signed in 1654 by representatives of the Ukrainian Cossack Hetmanate and Tsar Alexis of Russia.

The construction of North Crimean Canal, a land improvement canal for irrigation and watering of Kherson Oblast in southern Ukraine, and the Crimean peninsula, was started in 1957 soon after the transfer of Crimea. The canal also has multiple branches throughout Kherson Oblast and the Crimean peninsula. The main project works took place between 1961 and 1971 and had three stages. The construction was conducted by the Komosomol members sent by the Komsomol travel ticket (Komsomolskaya putyovka) as part of shock construction projects and accounted for some 10,000 "volunteer" workers.

In the post-war years, Crimea thrived as a tourist destination, with new attractions and sanatoriums for tourists. Tourists came from all around the Soviet Union and aligned countries, particularly from the German Democratic Republic. In time the peninsula also became a major tourist destination for cruises originating in Greece and Turkey. Crimea's infrastructure and manufacturing also developed, particularly around the sea ports at Kerch and Sevastopol and in the oblast's landlocked capital, Simferopol. Populations of Ukrainians and Russians alike doubled, with more than 1.6 million Russians and 626,000 Ukrainians living on the peninsula by 1989.

Post Soviet Union

Ukraine (de jure since 1991, de facto 1991–2014)

With the

With the dissolution of the Soviet Union

The dissolution of the Soviet Union, also negatively connoted as rus, Разва́л Сове́тского Сою́за, r=Razvál Sovétskogo Soyúza, ''Ruining of the Soviet Union''. was the process of internal disintegration within the Sov ...

and Ukrainian independence the majority ethnic Russian

The Russian diaspora is the global community of ethnic Russians. The Russian-speaking (''Russophone'') diaspora are the people for whom Russian language is the native language, regardless of whether they are ethnic Russians or not.

History

...

Crimean peninsula was reorganized as the Republic of Crimea,,''National Identity and Ethnicity in Russia and the New States of Eurasia'' edited by Roman Szporluk (page 174) after a 1991 referendum with the Crimean authorities pushing for more independence from Ukraine and closer links with Russia. In 1995 the Republic was forcibly abolished by Ukraine with the Autonomous Republic of Crimea

The Autonomous Republic of Crimea, commonly known as Crimea, is a de jure autonomous republic of Ukraine encompassing most of Crimea that was annexed by Russia in 2014. The Autonomous Republic of Crimea occupies most of the peninsula,

established firmly under Ukrainian authority. There were also intermittent tensions with Russia over the Soviet Fleet, although a 1997 treaty partitioned the Soviet Black Sea Fleet

Chernomorskiy flot

, image = Great emblem of the Black Sea fleet.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Great emblem of the Black Sea fleet

, dates = May 13, ...

allowing Russia to continue basing its fleet in Sevastopol with the lease extended

Extension, extend or extended may refer to:

Mathematics

Logic or set theory

* Axiom of extensionality

* Extensible cardinal

* Extension (model theory)

* Extension (predicate logic), the set of tuples of values that satisfy the predicate

* Exte ...

in 2010. As a result of the overthrow

Overthrow may refer to:

* Overthrow, a change in government, often achieved by force or through a coup d'état.

**The 5th October Overthrow, or Bulldozer Revolution, the events of 2000 that led to the downfall of Slobodan Milošević in the former ...

of the relatively pro Russian president Yanukovych

Viktor Fedorovych Yanukovych ( uk, Віктор Федорович Янукович, ; ; born 9 July 1950) is a former politician who served as the fourth president of Ukraine

The president of Ukraine ( uk, Президент Украї� ...

, Russian annexed Crimea in 2014.

Russian annexation

The events in Kyiv that ousted Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych sparkeddemonstrations

Demonstration may refer to:

* Demonstration (acting), part of the Brechtian approach to acting

* Demonstration (military), an attack or show of force on a front where a decision is not sought

* Demonstration (political), a political rally or prote ...

against the new Ukrainian government.In Yalta was organized Euromaidan, in Sevastopol were demanding to imprison the opposition. Ukrayinska Pravda. 19 February 2014 At the same time Russian president Vladimir Putin discussed Ukrainian events with security service chiefs remarking that "we must start working on returning Crimea to Russia". On 27 February,

Russian troops

The Russian Ground Forces (russian: Сухопутные войска �ВSukhoputnyye voyska V}), also known as the Russian Army (, ), are the land forces of the Russian Armed Forces.

The primary responsibilities of the Russian Ground Forces ...

captured strategic sites across Crimea. This led to the installation of the pro-Russian Aksyonov government in Crimea, the Crimean status referendum and the declaration of Crimea's independence on 16 March 2014. Although Russia initially claimed their military was not involved in the events, it later admitted that they were.Russia formally incorporated Crimea on 18 March 2014. Following the annexation, Russia escalated its military presence on the peninsula and made

nuclear

Nuclear may refer to:

Physics

Relating to the nucleus of the atom:

* Nuclear engineering

*Nuclear physics

*Nuclear power

*Nuclear reactor

*Nuclear weapon

*Nuclear medicine

*Radiation therapy

*Nuclear warfare

Mathematics

*Nuclear space

*Nuclear ...

threats to solidify the new status quo on the ground.

Ukraine and many other countries condemned the annexation and consider it to be a violation of international law and Russian agreements safeguarding the territorial integrity of Ukraine. The annexation led to the other members of the then- G8 suspending Russia from the group and introducing sanctions

A sanction may be either a permission or a restriction, depending upon context, as the word is an auto-antonym.

Examples of sanctions include:

Government and law

* Sanctions (law), penalties imposed by courts

* Economic sanctions, typically a b ...

. The United Nations General Assembly also rejected the referendum and annexation, adopting a resolution affirming the "territorial integrity of Ukraine within its internationally recognised borders".

The Russian government opposes the "annexation" label, with Putin defending the referendum as complying with the principle of the self-determination

The right of a people to self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international law (commonly regarded as a ''jus cogens'' rule), binding, as such, on the United Nations as authoritative interpretation of the Charter's norms. It stat ...

of peoples.

Aftermath

Within days of the signing of the accession treaty, the process of integrating Crimea into the Russian federation began with the Russian ruble going into official circulation and later to be the sole currency for legal tender with clocks also moved to Moscow time. A revision of theRussian Constitution

The Constitution of the Russian Federation () was adopted by national referendum on 12 December 1993. Russia's constitution came into force on 25 December 1993, at the moment of its official publication, and abolished the Soviet system of gov ...

was officially released with the Republic of Crimea and the federal city of Sevastopol added to the federal subjects of the Russian Federation

The federal subjects of Russia, also referred to as the subjects of the Russian Federation (russian: субъекты Российской Федерации, subyekty Rossiyskoy Federatsii) or simply as the subjects of the federation (russian ...

, and the Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev

Dmitry Anatolyevich Medvedev ( rus, links=no, Дмитрий Анатольевич Медведев, p=ˈdmʲitrʲɪj ɐnɐˈtolʲjɪvʲɪtɕ mʲɪdˈvʲedʲɪf; born 14 September 1965) is a Russian politician who has been serving as the dep ...

stated that Crimea had been fully integrated into Russia. Since the annexation Russia has supported large migration into Crimea.

Once Ukraine lost control of the territory in 2014, it shut off the water supply of the North Crimean Canal which supplies 85% of the peninsula's freshwater needs from the Dnieper river, the nation's main waterway. Development of new sources of water was undertaken, with huge difficulties, to replace closed Ukrainian sources. In 2022

File:2022 collage V1.png, Clockwise, from top left: Road junction at Yamato-Saidaiji Station several hours after the assassination of Shinzo Abe; 2022 Sri Lankan protests, Anti-government protest in Sri Lanka in front of the Presidential Secretari ...

, Russia conquered

Conquest is the act of military subjugation of an enemy by force of arms.

Military history provides many examples of conquest: the Roman conquest of Britain, the Mauryan conquest of Afghanistan and of vast areas of the Indian subcontinent, t ...

portions of Kherson Oblast, which allowed it to unblock the North Crimean canal by force, resuming water supply into Crimea.

2022 Crimea attacks

Beginning in July 2022, a series of explosions and fires occurred on the Russian-occupied Crimean Peninsula from where the Russian Army had launched its offensive on Southern Ukraine during the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Occupied Crimea was a base for the subsequent Russian occupation of Kherson Oblast andRussian occupation of Zaporizhzhia Oblast

The Russian occupation of Zaporizhzhia Oblast is an ongoing military occupation, which began on 24 February 2022, as Russian forces invaded Ukraine and began capturing the southern portion of Zaporizhzhia Oblast. On 26 February, the city of ...

. The Ukrainian government has not accepted responsibility for all of the attacks.

See also

*Kizil-Koba culture Kizil-Koba is a Middle Paleolithic culture belonging to a people who lived in the 9th–8th millennia BC in the Eastern Crimean territory and ancestral to Tauri. It is known as the first Eastern European settlement, where Neanderthal remains were fo ...

* Cimmerians

*Tauri

The Tauri (; in Ancient Greek), or Taurians, also Scythotauri, Tauri Scythae, Tauroscythae (Pliny, ''H. N.'' 4.85) were an ancient people settled on the southern coast of the Crimea peninsula, inhabiting the Crimean Mountains in the 1st millenni ...

* Scythian Neapolis

* Greeks in pre-Roman Crimea

* Chersonesus

* Bosporan Kingdom

* Kingdom of Pontus

*Crimea in the Roman era The Crimean Peninsula (at the time known as ''Taurica'') was under partial control of the Roman Empire during the period of 47 BC to c. 340 AD.

The territory under Roman control mostly coincided with the Bosporan Kingdom (although under Nero, fro ...

* Akatziri

* Crimean Goths

* Crimean Tatars

* Crimean Khanate

* Khazars

* Crimean Karaites

* Annexation of Crimea by the Russian Empire

* Taurida Oblast

* Novorossiya Governorate

* Taurida Governorate

* Crimean War

* Crimean People's Republic

*Taurida Soviet Socialist Republic

The Taurida Soviet Socialist Republic ( rus, Советская Социалистическая Республика Тавриды, r=Sovetskaya Sotsialisticheskaya Respublika Tavridy) was an unsuccessful attempt to establish a Soviet republic ...

* Crimean Regional Government

*Crimean Socialist Soviet Republic

The Crimean Socialist Soviet RepublicHarold Henry Fisher. The Famine in Soviet Russia, 1919-1923: The Operations of the American Relief Administration.' Ayer Publishing, 1971. p. 278. (russian: Крымская Социалистическая � ...

* South Russian Government

*Government of South Russia

The Government of South Russia (russian: Правительство Юга России, Pravitel'stvo Yuga Rossii) was a White movement government established in Sevastopol, Crimea in April 1920.

It was the successor to General Anton Denikin's ...

*Soviet-era Crimea

During the existence of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, different governments existed within the Crimean Peninsula. From 1921 to 1936, the government in the Crimean Peninsula was known as the Crimean Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic; ...

*Crimean ASSR (1991-1992)

During the existence of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, different governments existed within the Crimean Peninsula. From 1921 to 1936, the government in the Crimean Peninsula was known as the Crimean Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic; ...

*Republic of Crimea (1992-1995)

The Republic of Crimea, translit. ''Respublika Krym'' ; uk, Республіка Крим, translit. ''Respublika Krym'' ; crh, , is an unrecognized federal subject ( republic) of Russia, comprising most of the Crimean Peninsula, excludi ...

*Autonomous Republic of Crimea

The Autonomous Republic of Crimea, commonly known as Crimea, is a de jure autonomous republic of Ukraine encompassing most of Crimea that was annexed by Russia in 2014. The Autonomous Republic of Crimea occupies most of the peninsula,

Notes

Further reading

* Allworth, Edward, ed. ''Tatars of the Crimea. Return to the Homeland'' (Duke University Press. 1998), articles by scholars * * Cordova, Carlos. ''Crimea and the Black Sea: An environmental history.'' (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2015.) * Dickinson, Sara. "Russia's First 'Orient': Characterizing the Crimea in 1787." ''Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History'' 3.1 (2002): 3-25online

* * Kent, Neil (2016). ''Crimea: A History''. Hurst Publishers. . * * Kirimli, Hakan. ''National Movements and National Identity Among the Crimean Tatars (1905 - 1916)'' (E.J. Brill. 1996) * Magocsi, Paul Robert (2014). ''This Blessed Land: Crimea and the Crimean Tatars''. University of Toronto Press. . * Milner, Thomas. ''The Crimea: Its Ancient and Modern History: the Khans, the Sultans, and the Czars. ''Longman, 1855

online

* O'Neill, Kelly. ''Claiming Crimea: A History of Catherine the Great's Southern Empire'' (Yale University Press, 2017). * Ozhiganov, Edward. "The Crimean Republic: Rivalries for Control." in ''Managing Conflict in the Former Soviet Union: Russian and American Perspectives'' (MIT Press. 1997). pp. 83–137. * Pleshakov, Constantine. ''The Crimean Nexus: Putin's War and the Clash of Civilizations'' (Yale University Press, 2017). * Sasse, Gwendolyn. ''The Crimea Question: Identity, Transition, and Conflict'' (2007) * * , recent developments * Williams, Brian Glyn. ''The Crimean Tatars: The Diaspora Experience and the Forging of a Nation'' (Brill 2001

online

Historiography

* Kizilov, Mikhail; Prokhorov, Dmitry. "The Development of Crimean Studies in the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union, and Ukraine," ''Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae'' (Dec 2011), Vol. 64 Issue 4, pp437–452.Primary sources

*; complete text online * Wood, Evelyn. ''The Crimea in 1854, and 1894: With Plans, and Illustrations from Sketches Taken on the Spot by Colonel W. J. Colville'' (2005excerpt and text search

External links

Historical footage of Crimea, 1918

filmportal.de

On the role of Crimea in the Russian discourse

i

The Crimean Archipelago: A Multimedia Dossier

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Crimea