A Soldier's Declaration on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Siegfried Loraine Sassoon (8 September 1886 – 1 September 1967) was an English

Siegfried Sassoon was born to a Jewish father and an

Siegfried Sassoon was born to a Jewish father and an

Siegfried Sassoon and cricket

''

Motivated by patriotism, Sassoon joined the Army just as the threat of a new European war was recognized, and was in service with the

Motivated by patriotism, Sassoon joined the Army just as the threat of a new European war was recognized, and was in service with the

Having lived for a period at

Having lived for a period at

On 11 November 1985, Sassoon was among sixteen Great War poets commemorated on a slate stone unveiled in

On 11 November 1985, Sassoon was among sixteen Great War poets commemorated on a slate stone unveiled in

* ''The Daffodil Murderer'' (John Richmond: 1913)

* '' The Old Huntsman'' (

* ''The Daffodil Murderer'' (John Richmond: 1913)

* '' The Old Huntsman'' (

* ''

* ''

''Siegfried's Journal'': the journal of the Siegfried Sassoon Fellowship.

Sassoon on the War poets from ''Vanity Fair'' magazine (1920

Siegfried Sassoon collection of papers, 1905–1975, bulk (1915–1951)

(669 items) are held at the

Siegfried Sassoon papers, 1894–1966

(3 linear ft. (ca.630 items in 4 boxes & 13 slipcases)) are held at

Siegfried Sassoon papers, 1908–1966

(109 items) are held in the

Profile at Poetry Foundation

1920 *Vanity Fair* magazine article by Sassoon

Profile at Poetry Archive. Biography and poems written and audio

The Siegfried Sassoon Fellowship

Siegfried Sassoon profile and poems at Poets.org

BBC: ''In our time''. (Audio discussion 45 mins)

with bibliography and links. Updated 18-Mar-15

BBC

interview 1 January 1967 (Audio, 7 mins) Dead link Updated 18-Mar-15

WGBH Forum Network lecture

given by Sassoon biographer

Siegfried Sassoon collection of papers, circa 1905–1975, bulk (1915–1951)

(669 items),

Papers of Siegfried Sassoon

Sassoon in the Great War Archive

Oxford University/

BBC Audio slideshow.

Sassoon's papers at Cambridge University Library.

Elizabeth Whitcomb Houghton Collection

Sassoon archive

Sassoon Journals

digitised in

Finding aid to Siegfried Sassoon papers

at Columbia University, Rare Book & Manuscript Library * Siegfried Sassoon Papers. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. {{DEFAULTSORT:Sassoon, Siegfried 1886 births 1967 deaths British Army personnel of World War I English World War I poets People with post-traumatic stress disorder 20th-century male writers Commanders of the Order of the British Empire Converts to Roman Catholicism from Judaism English Catholic poets English diarists English memoirists English people of Indian-Jewish descent English people of Iraqi-Jewish descent English Roman Catholics Fox hunters Fox hunting writers James Tait Black Memorial Prize recipients Bisexual men Bisexual military personnel LGBT Roman Catholics People educated at Marlborough College People from Matfield Recipients of the Military Cross Roman Catholic writers Royal Welch Fusiliers officers Sassoon family Thornycroft family War writers 20th-century English poets Alumni of Clare College, Cambridge English LGBT poets Burials in Somerset Sussex Yeomanry soldiers Bisexual writers British writers of Indian descent Baghdadi Jews Military personnel from Kent

war poet

A war poet is a poet who participates in a war and writes about their experiences, or a non-combatant who writes poems about war. While the term is applied especially to those who served during the First World War, the term can be applied to a p ...

, writer, and soldier. Decorated for bravery on the Western Front, he became one of the leading poets of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. His poetry both described the horrors of the trenches and satirised the patriotic pretensions of those who, in Sassoon's view, were responsible for a jingoism

Jingoism is nationalism in the form of aggressive and proactive foreign policy, such as a country's advocacy for the use of threats or actual force, as opposed to peaceful relations, in efforts to safeguard what it perceives as its national inte ...

-fuelled war. Sassoon became a focal point for dissent within the armed forces when he made a lone protest against the continuation of the war in his "Soldier's Declaration" of 1917, culminating in his admission to a military psychiatric hospital; this resulted in his forming a friendship with Wilfred Owen

Wilfred Edward Salter Owen MC (18 March 1893 – 4 November 1918) was an English poet and soldier. He was one of the leading poets of the First World War. His war poetry on the horrors of trenches and gas warfare was much influenced by ...

, who was greatly influenced by him. Sassoon later won acclaim for his prose work, notably his three-volume fictionalised autobiography, collectively known as the "Sherston trilogy

The Sherston trilogy is a series of books by the English poet and novelist, Siegfried Sassoon, consisting of ''Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man'', '' Memoirs of an Infantry Officer'', and ''Sherston's Progress''. They are named after the protagonist, ...

".

Early life

Siegfried Sassoon was born to a Jewish father and an

Siegfried Sassoon was born to a Jewish father and an Anglo-Catholic

Anglo-Catholicism comprises beliefs and practices that emphasise the Catholic heritage and identity of the various Anglican churches.

The term was coined in the early 19th century, although movements emphasising the Catholic nature of Anglican ...

mother, and grew up in the neo-gothic mansion named "Weirleigh" (after its builder, Harrison Weir

Harrison William Weir (5 May 18243 January 1906), known as "The Father of the Cat Fancy", was a British artist.

He organised the first cat show in England, at the Crystal Palace, London, in July 1871. He and his brother, John Jenner Weir, bo ...

), in Matfield

Matfield is a small village, part of the civil parish of Brenchley and Matfield, in the Tunbridge Wells borough of Kent, England. Matfield was awarded the title of Kent Village of the Year in 2010.

Buildings and amenities

St Luke's Church is ...

, Kent. His father, Alfred Ezra Sassoon (1861–1895), son of Sassoon David Sassoon

Sassoon David Sassoon (August 1832 – 24 June 1867) was a British Indian businessman, banker, and philanthropist.

Biography

Early life

Sassoon was born in August 1832 in Bombay, India.William D. Rubinstein, ''The Palgrave Dictionary of An ...

, was a member of the wealthy Baghdadi Jewish

The former communities of Jewish migrants and their descendants from Baghdad and elsewhere in the Middle East are traditionally called Baghdadi Jews or Iraqi Jews. They settled primarily in the ports and along the trade routes around the Indian ...

Sassoon merchant family. For marrying outside the faith, Alfred was disinherited. Siegfried's mother, Theresa

Teresa (also Theresa, Therese; french: Thérèse) is a feminine given name.

It originates in the Iberian Peninsula in late antiquity. Its derivation is uncertain, it may be derived from Greek θερίζω (''therízō'') "to harvest or re ...

, belonged to the Thornycroft family

The Thornycroft family was a notable English family of sculptors, artists and engineers, connected by marriage to the historic Sassoon family. The earliest known mention of the family is stated in George Ormerod

George Ormerod (20 October ...

, sculptors responsible for many of the best-known statues in London—her brother was Sir Hamo Thornycroft

Sir William Hamo Thornycroft (9 March 185018 December 1925) was an English sculptor, responsible for some of London's best-known statues, including the statue of Oliver Cromwell outside the Palace of Westminster. He was a keen student of classi ...

. There was no German ancestry in Sassoon's family; his mother named him Siegfried because of her love of Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most op ...

's operas. His middle name, Loraine, was the surname of a clergyman with whom she was friendly.

Siegfried was the second of three sons, the others being Michael and Hamo. When he was four years old his parents separated. During his father's weekly visits to the boys, Theresa locked herself in the drawing-room. In 1895 Alfred Sassoon died of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

.

Sassoon was educated at the New Beacon School

, motto_translation = Give light out of darkness

, established =

, closed =

, type = Preparatory School

, religious_affiliation =

, president =

, head_label = Headmas ...

, Sevenoaks

Sevenoaks is a town in Kent with a population of 29,506 situated south-east of London, England. Also classified as a civil parishes in England, civil parish, Sevenoaks is served by a commuter South Eastern Main Line, main line railway into Lon ...

, Kent; at Marlborough College

Marlborough College is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school (English Independent school (United Kingdom), independent boarding school) for pupils aged 13 to 18 in Marlborough, Wiltshire, England. Founded in 1843 for the sons of Church ...

, Wiltshire; and at Clare College, Cambridge

Clare College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge in Cambridge, England. The college was founded in 1326 as University Hall, making it the second-oldest surviving college of the University after Peterhouse. It was refounded ...

, where from 1905 to 1907 he read history. He went down from Cambridge without a degree and spent the next few years hunting, playing cricket and writing verse: some he published privately. Although his father had been disinherited from the Sassoon fortune for marrying a non-Jew, Siegfried had a small private income that allowed him to live modestly without having to earn a living (however, he would later be left a generous legacy by an aunt, Rachel Beer

Rachel Beer (''née'' Sassoon; 7 April 1858 – 29 April 1927) was an Indian-born British newspaper editor. She was editor-in-chief of ''The Observer'' and ''The Sunday Times''.

Early life

Rachel Sassoon was born in Bombay to Sassoon David Sas ...

, allowing him to buy the great estate of Heytesbury House in Wiltshire.) His first published success, ''The Daffodil Murderer'' (1913), was a parody of John Masefield

John Edward Masefield (; 1 June 1878 – 12 May 1967) was an English poet and writer, and Poet Laureate from 1930 until 1967. Among his best known works are the children's novels ''The Midnight Folk'' and ''The Box of Delights'', and the poem ...

's '' The Everlasting Mercy''. Robert Graves

Captain Robert von Ranke Graves (24 July 1895 – 7 December 1985) was a British poet, historical novelist and critic. His father was Alfred Perceval Graves, a celebrated Irish poet and figure in the Gaelic revival; they were both Celtic ...

, in ''Good-Bye to All That

''Good-Bye to All That'' is an autobiography by Robert Graves which first appeared in 1929, when the author was 34 years old. "It was my bitter leave-taking of England," he wrote in a prologue to the revised second edition of 1957, "where I had ...

'', describes it as a "parody of Masefield which, midway through, had forgotten to be a parody and turned into rather good Masefield."

Sassoon expressed his opinions on the political situation before the onset of the First World War thus—"France was a lady, Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

was a bear, and performing in the county cricket

Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of eleven players on a field at the centre of which is a pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two bails balanced on three stumps. The batting side scores runs by striki ...

team was much more important than either of them". Sassoon wanted to play for Kent County Cricket Club

Kent County Cricket Club is one of the eighteen first-class county clubs within the domestic cricket structure of England and Wales. It represents the historic county of Kent. A club representing the county was first founded in 1842 but Ke ...

; the Marchant family were neighbours, and Frank Marchant

Francis Marchant (22 May 1864 – 13 April 1946), known as Frank Marchant, was an English amateur cricketer. He was a right-handed batsman, an occasional wicket-keeper and the captain of Kent County Cricket Club from 1890 to 1897.

Early life

M ...

was captain of the county side between 1890 and 1897. Sassoon often turned out for Bluemantles at the Nevill Ground

The Nevill Ground is a cricket ground at Royal Tunbridge Wells in the English county of Kent. It is owned by Tunbridge Wells Borough Council and is used by Tunbridge Wells Cricket Club in the summer months and by Tunbridge Wells Hockey Club in t ...

, Tunbridge Wells, where he sometimes played alongside Arthur Conan Doyle

Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle (22 May 1859 – 7 July 1930) was a British writer and physician. He created the character Sherlock Holmes in 1887 for ''A Study in Scarlet'', the first of four novels and fifty-six short stories about Ho ...

. He had also played cricket for his house at Marlborough College, once taking 7 wickets for 18 runs. Although an enthusiast, Sassoon was not good enough to play for his county, but he played for Matfield village, and later for a Downside Abbey

Downside Abbey is a Benedictine monastery in England and the senior community of the English Benedictine Congregation. Until 2019, the community had close links with Downside School, for the education of children aged eleven to eighteen. Both t ...

team called "The Ravens", continuing into his seventies.Coldham, James D (1954Siegfried Sassoon and cricket

''

The Cricketer

''The Cricketer'' is a monthly English cricket magazine providing writing and photography from international, county and club cricket.

The magazine was founded in 1921 by Sir Pelham Warner, an ex-England captain turned cricket writer. Warner e ...

'', June 1954. Republished at CricInfo

ESPN cricinfo (formerly known as Cricinfo or CricInfo) is a sports news website exclusively for the game of cricket. The site features news, articles, live coverage of cricket matches (including liveblogs and scorecards), and ''StatsGuru'', a d ...

.

War service

The Western Front: Military Cross

Motivated by patriotism, Sassoon joined the Army just as the threat of a new European war was recognized, and was in service with the

Motivated by patriotism, Sassoon joined the Army just as the threat of a new European war was recognized, and was in service with the Sussex Yeomanry

The Sussex Yeomanry is a yeomanry regiment of the British Army dating from 1794. It was initially formed when there was a threat of French invasion during the Napoleonic Wars. After being reformed in the Second Boer War, it served in the First Wo ...

on 4 August 1914, the day the United Kingdom declared war on Germany. He broke his arm badly in a riding accident and was put out of action before leaving England, spending the spring of 1915 convalescing. He was commissioned into the 3rd Battalion (Special Reserve

The Special Reserve was established on 1 April 1908 with the function of maintaining a reservoir of manpower for the British Army and training replacement drafts in times of war. Its formation was part of the Haldane Reforms, military reforms im ...

), Royal Welch Fusiliers

The Royal Welch Fusiliers ( cy, Ffiwsilwyr Brenhinol Cymreig) was a line infantry regiment of the British Army, and part of the Prince of Wales' Division, that was founded in 1689; shortly after the Glorious Revolution. In 1702, it was designated ...

, as a second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army until ...

on 29 May 1915. On 1 November his younger brother Hamo was killed in the Gallipoli Campaign, dying on board the ship after having had his leg amputated. In the same month Siegfried was sent to the 1st Battalion in France, where he met Robert Graves

Captain Robert von Ranke Graves (24 July 1895 – 7 December 1985) was a British poet, historical novelist and critic. His father was Alfred Perceval Graves, a celebrated Irish poet and figure in the Gaelic revival; they were both Celtic ...

, and they became close friends. United by their poetic vocation, they often read and discussed each other's work. Though this did not have much perceptible influence on Graves' poetry, his views on what may be called 'gritty realism' profoundly affected Sassoon's concept of what constituted poetry. He soon became horrified by the realities of war, and the tone of his writing changed completely: where his early poems exhibit a Romantic, dilettantish sweetness, his war poetry moves to an increasingly discordant music, intended to convey the ugly truths of the trenches to an audience hitherto lulled by patriotic propaganda. Details such as rotting corpses, mangled limbs, filth, cowardice and suicide are all trademarks of his work at this time, and this philosophy of 'no truth unfitting' had a significant effect on the movement towards Modernist

Modernism is both a philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new forms of art, philosophy, an ...

poetry.

Sassoon's periods of duty on the Western Front were marked by exceptionally brave actions, including the single-handed capture of a German trench in the Hindenburg Line

The Hindenburg Line (German: , Siegfried Position) was a German defensive position built during the winter of 1916–1917 on the Western Front during the First World War. The line ran from Arras to Laffaux, near Soissons on the Aisne. In 191 ...

. Armed with grenades, he scattered sixty German soldiers:He went over with bombs in daylight, under covering fire from a couple of rifles, and scared away the occupants. A pointless feat, since instead of signalling for reinforcements, he sat down in the German trench and began reading a book of poems which he had brought with him. When he went back he did not even report. Colonel Stockwell, then in command, raged at him. The attack on Mametz Wood had been delayed for two hours because British patrols were still reported to be out. "British patrols" were Siegfried and his book of poems. "I'd have got you a DSO, if you'd only shown more sense," stormed Stockwell.Sassoon's bravery was so inspiring that soldiers of his company said that they felt confident only when they were accompanied by him. He often went out on night raids and bombing patrols, and demonstrated ruthless efficiency as a company commander. Deepening depression at the horror and misery the soldiers were forced to endure produced in Sassoon a paradoxically manic courage, and he was nicknamed "Mad Jack" by his men for his near-suicidal exploits. On 27 July 1916 he was awarded the

Military Cross

The Military Cross (MC) is the third-level (second-level pre-1993) military decoration awarded to officers and (since 1993) other ranks of the British Armed Forces, and formerly awarded to officers of other Commonwealth countries.

The MC i ...

; the citation read:

Robert Graves described Sassoon as engaging in suicidal feats of bravery. Sassoon was also later recommended for the Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest and most prestigious award of the British honours system. It is awarded for valour "in the presence of the enemy" to members of the British Armed Forces and may be awarded posthumously. It was previously ...

.

War opposition and Craiglockhart

Despite his decorations and reputation, in 1917 Sassoon decided to make a stand against the conduct of the war. One of the reasons for his violent anti-war feeling was the death of his friendDavid Cuthbert Thomas

Second Lieutenant David Cuthbert Thomas (1895 – 18 March 1916) was a Welsh soldier of the British Army who served during the First World War. He is best known for his association with the poet Siegfried Sassoon, who after his death became th ...

, who appears as "Dick Tiltwood" in the Sherston trilogy

The Sherston trilogy is a series of books by the English poet and novelist, Siegfried Sassoon, consisting of ''Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man'', '' Memoirs of an Infantry Officer'', and ''Sherston's Progress''. They are named after the protagonist, ...

. Sassoon would spend years trying to overcome his grief.

In August 1916, Sassoon arrived at Somerville College, Oxford

Somerville College, a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England, was founded in 1879 as Somerville Hall, one of its first two women's colleges. Among its alumnae have been Margaret Thatcher, Indira Gandhi, Dorothy Hodgkin, Ir ...

, which was used as a hospital for convalescing officers, with a case of gastric fever. He wrote: "To be lying in a little white-walled room, looking through the window on to a College lawn, was for the first few days very much like a paradise". Graves ended up at Somerville as well. "How unlike you to crib my idea of going to the Ladies' College at Oxford", Sassoon wrote to him in 1917.

At the end of a spell of convalescent leave, Sassoon declined to return to duty; instead, encouraged by pacifist friends such as Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British mathematician, philosopher, logician, and public intellectual. He had a considerable influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, linguistics, ...

and Lady Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Violet Anne Morrell (16 June 1873 – 21 April 1938) was an English aristocrat and society hostess. Her patronage was influential in artistic and intellectual circles, where she befriended writers including Aldous Huxley, Sieg ...

, he sent a letter to his commanding officer entitled '' Finished with the War: A Soldier’s Declaration''. Forwarded to the press and read out in the House of Commons by a sympathetic member of Parliament, the letter was seen by some as treasonous ("I am making this statement as an act of wilful defiance of military authority") or at best as condemning the war government's motives ("I believe that the war upon which I entered as a war of defence and liberation has now become a war of aggression and conquest"). Rather than court-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

Sassoon, the Under-Secretary of State for War

The position of Under-Secretary of State for War was a British government position, first applied to Evan Nepean (appointed in 1794). In 1801 the offices for War and the Colonies were merged and the post became that of Under-Secretary of State for ...

, Ian Macpherson, decided that he was unfit for service and had him sent to Craiglockhart War Hospital near Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, where he was officially treated for neurasthenia

Neurasthenia (from the Ancient Greek νεῦρον ''neuron'' "nerve" and ἀσθενής ''asthenés'' "weak") is a term that was first used at least as early as 1829 for a mechanical weakness of the nerves and became a major diagnosis in North A ...

("shell shock

Shell shock is a term coined in World War I by the British psychologist Charles Samuel Myers to describe the type of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) many soldiers were afflicted with during the war (before PTSD was termed). It is a react ...

").

At the end of 1917, Sassoon was posted to Limerick

Limerick ( ; ga, Luimneach ) is a western city in Ireland situated within County Limerick. It is in the province of Munster and is located in the Mid-West which comprises part of the Southern Region. With a population of 94,192 at the 2016 ...

, Ireland, where in the New Barracks he helped train new recruits. He wrote that it was a period of respite for him, and allowed him to indulge in his love of hunting

Hunting is the human activity, human practice of seeking, pursuing, capturing, or killing wildlife or feral animals. The most common reasons for humans to hunt are to harvest food (i.e. meat) and useful animal products (fur/hide (skin), hide, ...

. Reflecting on the period years later, he mentioned how trouble was brewing in Ireland at the time, in the few years before the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence () or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces: the British Army, along with the quasi-mil ...

. After only a short period in Limerick he was posted to Egypt, but not until he had several opportunities to hunt.

For many years it had been thought that, before declining to return to active service, Sassoon had thrown his MC ribbon into the River Mersey

The River Mersey () is in North West England. Its name derives from Old English and means "boundary river", possibly referring to its having been a border between the ancient kingdoms of Mercia and Northumbria. For centuries it has formed part ...

at Formby

Formby is a town and civil parish in the Metropolitan Borough of Sefton, Merseyside, England, which had a population of 22,419 at the 2011 Census.

Historically in Lancashire, three manors are recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086 under "For ...

beach. According to his description of this incident in ''Memoirs of an Infantry Officer

''Memoirs of an Infantry Officer'' is a novel by Siegfried Sassoon, first published in 1930. It is a fictionalised account of Sassoon's own life during and immediately after World War I. Soon after its release, it was heralded as a classic and ...

'' he did not do this as a symbolic rejection of militaristic values, but simply out of the need to perform some destructive act in catharsis of the black mood which was afflicting him; his account states that one of his pre-war sporting trophies, had he had one to hand, would have served his purpose equally well. The actual decoration was rediscovered after the death of Sassoon's only son, George, and subsequently became the subject of a dispute among Sassoon's heirs.

At Craiglockhart, Sassoon met Wilfred Owen

Wilfred Edward Salter Owen MC (18 March 1893 – 4 November 1918) was an English poet and soldier. He was one of the leading poets of the First World War. His war poetry on the horrors of trenches and gas warfare was much influenced by ...

, another poet. It was thanks to Sassoon that Owen persevered in his ambition to write better poetry. A manuscript copy of Owen's ''Anthem for Doomed Youth

"Anthem for Doomed Youth" is a poem written in 1917 by Wilfred Owen. It incorporates the theme of the horror of war.

Style

Like a traditional Petrarchan sonnet, the poem is divided into an octave and sestet. However, its rhyme scheme is neither ...

'' containing Sassoon's handwritten amendments survives as testimony to the extent of his influence and is currently on display at London's Imperial War Museum

Imperial War Museums (IWM) is a British national museum organisation with branches at five locations in England, three of which are in London. Founded as the Imperial War Museum in 1917, the museum was intended to record the civil and military ...

. Sassoon became to Owen "Keats

John Keats (31 October 1795 – 23 February 1821) was an English poet of the second generation of Romantic poets, with Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley. His poems had been in publication for less than four years when he died of tuberculos ...

and Christ and Elijah", according to a surviving letter which demonstrates the depth of Owen's love and admiration for him. Both men returned to active service in France, but Owen was killed in 1918, a week before Armistice. Sassoon was promoted to lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

, and, having spent some time out of danger in Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

, eventually returned to the Front. On 13 July 1918, Sassoon was wounded again—by friendly fire

In military terminology, friendly fire or fratricide is an attack by belligerent or neutral forces on friendly troops while attempting to attack enemy/hostile targets. Examples include misidentifying the target as hostile, cross-fire while eng ...

when he was shot in the head by a fellow British soldier who had mistaken him for a German near Arras

Arras ( , ; pcd, Aro; historical nl, Atrecht ) is the prefecture of the Pas-de-Calais Departments of France, department, which forms part of the regions of France, region of Hauts-de-France; before the regions of France#Reform and mergers of ...

, France. As a result, he spent the remainder of the war in Britain. By this time he had been promoted to acting captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

. He relinquished his commission on health grounds on 12 March 1919, but was allowed to retain the rank of captain.

After the war, Sassoon was instrumental in bringing Owen's work to the attention of a wider audience. Their relationship is the subject of Stephen MacDonald

Stephen MacDonald (5 May 1933 – 12 August 2009) was a British actor, director and dramatist.

MacDonald was brought up and educated in Birmingham, where he trained as an actor, but subsequently worked extensively in Scotland as a theatre d ...

's play, '' Not About Heroes''.

Post-war life

Editor and novelist

Having lived for a period at

Having lived for a period at Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, where he spent more time visiting literary friends than studying, Sassoon dabbled briefly in the politics of the Labour movement. In November 1918, he travelled to Blackburn to support the Labour candidate in the general election, Philip Snowden, who had been a pacifist during the war. Though a self-confessed political novice, Sassoon delivered campaign speeches for Snowden, later writing that he ‘felt grateful for nowden'santi-war attitude in parliament, and had been angered by the abuse thrown at him. All my political sympathies were with him.’ While his commitment to politics waned after this, he remained a supporter of the Labour Party, and in 1929 ‘rejoiced that hey

Hey or Hey! may refer to:

Music

* Hey (band), a Polish rock band

Albums

* ''Hey'' (Andreas Bourani album) or the title song (see below), 2014

* ''Hey!'' (Julio Iglesias album) or the title song, 1980

* ''Hey!'' (Jullie album) or the title s ...

had gained seats in the British general election.’ Similarly, ‘news of the massive Labour victory in 1945 pleased him, because many Tories from the class he had loathed during the First World War had gone.’

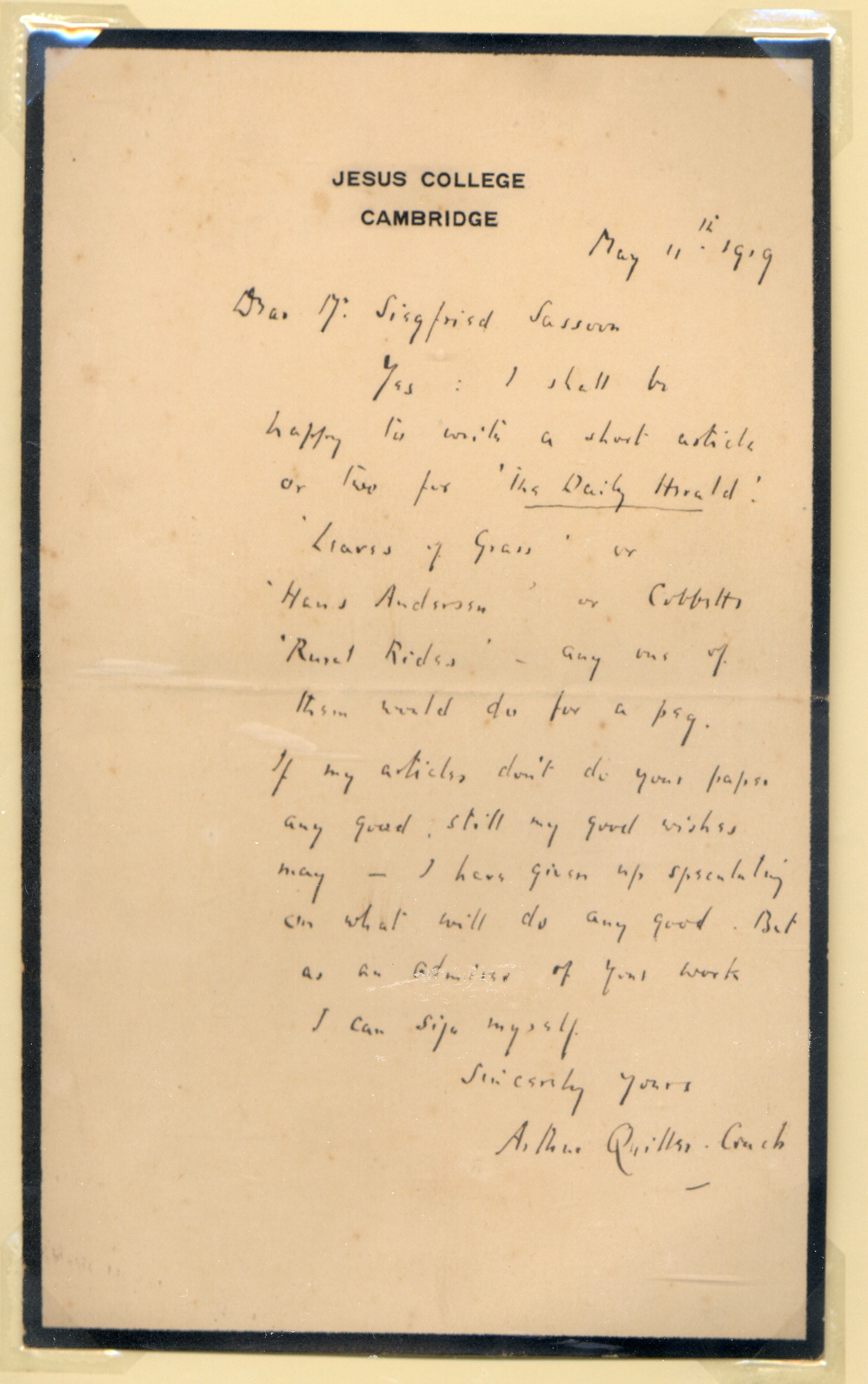

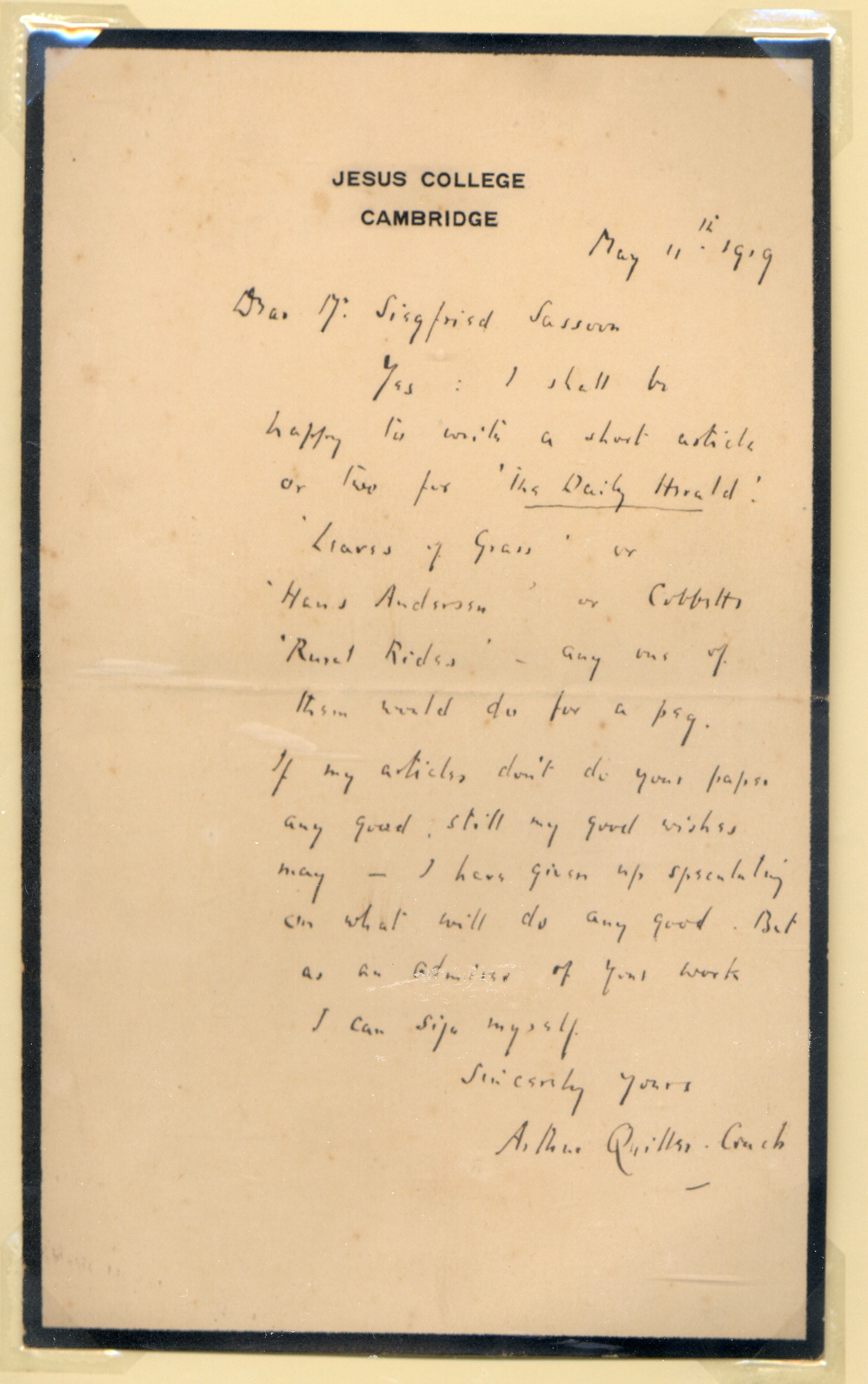

In 1919 took up a post as literary editor of the socialist '' Daily Herald''. He lived at 54 Tufton Street, Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Bu ...

, from 1919 to 1925; the house is no longer standing, but the location of his former home is marked by a memorial plaque.

During his period at the ''Herald'', Sassoon was responsible for employing several eminent names as reviewers, including E. M. Forster

Edward Morgan Forster (1 January 1879 – 7 June 1970) was an English author, best known for his novels, particularly ''A Room with a View'' (1908), ''Howards End'' (1910), and ''A Passage to India'' (1924). He also wrote numerous short stori ...

and Charlotte Mew

Charlotte Mary Mew (15 November 1869 – 24 March 1928) was an English poet whose work spans the eras of Victorian poetry and Modernism.

Early life and education

Mew was born in Bloomsbury, London, daughter of the architect Frederick Mew (18 ...

, and commissioned original material from writers like Arnold Bennett

Enoch Arnold Bennett (27 May 1867 – 27 March 1931) was an English author, best known as a novelist. He wrote prolifically: between the 1890s and the 1930s he completed 34 novels, seven volumes of short stories, 13 plays (some in collaboratio ...

and Osbert Sitwell

Sir Francis Osbert Sacheverell Sitwell, 5th Baronet CH CBE (6 December 1892 – 4 May 1969) was an English writer. His elder sister was Edith Sitwell and his younger brother was Sacheverell Sitwell. Like them, he devoted his life to art and li ...

. His artistic interests extended to music. While at Oxford he was introduced to the young William Walton

Sir William Turner Walton (29 March 19028 March 1983) was an English composer. During a sixty-year career, he wrote music in several classical genres and styles, from film scores to opera. His best-known works include ''Façade'', the cantat ...

, to whom he became a friend and patron. Walton later dedicated his ''Portsmouth Point

Portsmouth Point, or "Spice Island", is part of Old Portsmouth in Portsmouth, Hampshire, on the southern coast of England. The name Spice Island comes from the area's seedy reputation, as it was known as the "Spice of Life". Men were easily found ...

'' overture to Sassoon in recognition of his financial assistance and moral support.

Sassoon later embarked on a lecture tour of the US, as well as travelling in Europe and throughout Britain. He acquired a car, a gift from the publisher Frankie Schuster, and became renowned among his friends for his lack of driving skill, but this did not prevent him making full use of the mobility it gave him.

Sassoon had expressed his growing sense of identification with German soldiers in poems such as "Reconciliation" (1918), and after the war, he travelled extensively in Germany, visiting the country a number of times over the next decade. In 1921 Sassoon went to Rome, where he met the Kaiser’s nephew, Prince Philipp of Hesse. The two became lovers for a while, later taking a holiday together in Munich. While they had become estranged by the mid-1920s, due in part to geographical distance and in part, as Jean Moorcroft Wilson notes, to Sassoon’s increasing discomfort over Philipp’s growing interest in right-wing politics, Sassoon would continue to visit Germany. In 1927 he travelled to Berlin and Dresden with Osbert and Sacheverell Sitwell, and in 1929 he accompanied Stephen Tennant on a trip to a sanatorium in the Bavarian countryside.

Sassoon was a great admirer of the Welsh poet Henry Vaughan

Henry Vaughan (17 April 1621 – 23 April 1695) was a Welsh metaphysical poet, author and translator writing in English, and a medical physician. His religious poetry appeared in ''Silex Scintillans'' in 1650, with a second part in 1655.''Oxfo ...

. On a visit to Wales in 1923, he paid a pilgrimage to Vaughan's grave at Llansantffraed

Llansantffraed (Llansantffraed-juxta-Usk) is a parish in the community of Talybont-on-Usk in Powys, Wales, near Brecon. The benefice of Llansantffraed with Llanrhystud and Llanddeiniol falls within the Diocese of St Davids in the Church in Wale ...

, Powys

Powys (; ) is a Local government in Wales#Principal areas, county and Preserved counties of Wales, preserved county in Wales. It is named after the Kingdom of Powys which was a Welsh succession of states, successor state, petty kingdom and princi ...

, and there wrote one of his best-known peacetime poems, "At the Grave of Henry Vaughan". The deaths within a short space of time of three of his closest friends – Edmund Gosse

Sir Edmund William Gosse (; 21 September 184916 May 1928) was an English poet, author and critic. He was strictly brought up in a small Protestant sect, the Plymouth Brethren, but broke away sharply from that faith. His account of his childhoo ...

, Thomas Hardy

Thomas Hardy (2 June 1840 – 11 January 1928) was an English novelist and poet. A Victorian realist in the tradition of George Eliot, he was influenced both in his novels and in his poetry by Romanticism, including the poetry of William Word ...

and Frankie Schuster – came as another serious setback to his personal happiness.

At the same time, Sassoon was preparing to take a new direction. While in America, he had experimented with a novel. In 1928, he branched out into prose, with ''Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man

''Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man'' is a novel by Siegfried Sassoon, first published in 1928 by Faber and Faber. It won both the Hawthornden Prize and the James Tait Black Memorial Prize, being immediately recognised as a classic of English literat ...

'', the anonymously-published first volume of a fictionalised autobiography, which was almost immediately accepted as a classic, bringing its author new fame as a prose writer. The memoir, whose mild-mannered central character is content to do little more than be an idle country gentleman, playing cricket, riding and hunting foxes, is often humorous, revealing a side of Sassoon that had been little seen in his work during the war years. The book won the 1928 James Tait Black Award

The James Tait Black Memorial Prizes are literary prizes awarded for literature written in the English language. They, along with the Hawthornden Prize, are Britain's oldest literary awards. Based at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, Unit ...

for fiction. Sassoon followed it with ''Memoirs of an Infantry Officer

''Memoirs of an Infantry Officer'' is a novel by Siegfried Sassoon, first published in 1930. It is a fictionalised account of Sassoon's own life during and immediately after World War I. Soon after its release, it was heralded as a classic and ...

'' (1930) and ''Sherston's Progress

''Sherston's Progress'' is the final book of Siegfried Sassoon's semi-autobiographical trilogy. It is preceded by ''Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man'' and '' Memoirs of an Infantry Officer''.

Synopsis

The book starts with his arrival at 'Slateford ...

'' (1936). In later years, he revisited his youth and early manhood with three volumes of genuine autobiography, which were also widely acclaimed. These were ''The Old Century'', ''The Weald of Youth'' and ''Siegfried's Journey''.

Personal life

Affairs

Sassoon, having matured greatly as a result of his military service, continued to seek emotional fulfilment, initially in a succession of love affairs with men, including: * William Park "Gabriel" Atkin, the landscape architectural and figure painter, draftsman and illustrator *Ivor Novello

Ivor Novello (born David Ivor Davies; 15 January 1893 – 6 March 1951) was a Welsh actor, dramatist, singer and composer who became one of the most popular British entertainers of the first half of the 20th century.

He was born into a musical ...

, actor

* Glen Byam Shaw

Glencairn Alexander "Glen" Byam Shaw, CBE (13 December 1904 – 29 April 1986) was an English actor and theatre director, known for his dramatic productions in the 1950s and his operatic productions in the 1960s and later.

In the 1920s and 1930 ...

, actor and Novello's former lover

* Prince Philipp of Hesse

Philipp, Prince and Landgrave of Hesse (6 November 1896 – 25 October 1980) was head of the Electoral House of Hesse from 1940 to 1980.

He joined the Nazi Party in 1930, and, when they gained power with the appointment of Adolf Hitler as Chancel ...

, German aristocrat

* Beverley Nichols

John Beverley Nichols (9 September 1898 – 15 September 1983) was an English writer, playwright and public speaker. He wrote more than 60 books and plays.

Career

Between his first book, the novel, ''Prelude'' (1920) and his last, a book of po ...

, writer

* the Hon. Stephen Tennant, an aristocrat

Though Shaw remained Sassoon's close friend throughout his life, only Tennant made a permanent impression.

Introduced by the Sitwells in 1927, Sassoon and Stephen Tennant fell passionately in love, beginning a relationship which would last nearly six years.

Tennant, however, had recurrent tuberculosis, and the strain which that put on their relationship had started to show by the early 1930s. In May 1933, Tennant, then receiving treatment at a sanatorium in Kent, abruptly broke off the relationship, informing Sassoon via a letter written by his doctor that he never wanted to see him again. Sassoon was devastated. When he met his future wife Hester Gatty a few months later, he was still reeling from his break-up with Tennant. Sensing a sympathetic nature, Sassoon confided in Hester about their relationship and, at her suggestion, wrote Tennant a letter to put the past to rest. Whilst he and Tennant would exchange letters, telephone calls and infrequent visits in the years to come, they never resumed their previous relationship.

Marriage and later life

In September 1931, Sassoon rented Fitz House,Teffont Magna

Teffont Magna, sometimes called Upper Teffont, is a small village and former civil parish in the Nadder valley in the south of the county of Wiltshire, England.

For most of its history Teffont Magna was a chapelry of neighbouring Dinton. In 1 ...

, Wiltshire, and began to live there. In December 1933, he married Hester Gatty (daughter of Stephen Herbert Gatty

Sir Stephen Herbert Gatty (1849-1922) was the Chief Justice of Gibraltar from 16 January 1895 to 1905. He was formerly a judge of the Supreme Court of the Straits Settlements. On December 19, 1904, he was named a Knight Bachelor.

Personal life

...

), who was twenty years his junior, and soon afterwards they moved to Heytesbury House. The marriage led to the birth of a child, something Sassoon had purportedly craved for a long time. Siegfried's son, George Sassoon

George Thornycroft Sassoon (30 October 1936 – 8 March 2006) was a British scientist, electronic engineer, linguist, translator and author.

Early life

Sassoon was the only child of the poet Siegfried Sassoon and Hester Sassoon (née Gatty), and ...

(1936–2006), became a scientist, linguist, and author, and was adored by Siegfried, who wrote several poems addressed to him. Siegfried's marriage broke down after the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, with Sassoon apparently unable to find a compromise between the solitude he enjoyed and the companionship he needed. Separated from his wife in 1945, Sassoon lived in seclusion at Heytesbury

Heytesbury is a village (formerly considered to be a town) and a civil parish in Wiltshire, England. The village lies on the north bank of the Wylye, about southeast of the town of Warminster.

The civil parish includes most of the small neigh ...

in Wiltshire, although he maintained contact with a circle which included E. M. Forster

Edward Morgan Forster (1 January 1879 – 7 June 1970) was an English author, best known for his novels, particularly ''A Room with a View'' (1908), ''Howards End'' (1910), and ''A Passage to India'' (1924). He also wrote numerous short stori ...

and J. R. Ackerley. One of his closest friends was the cricketer Dennis Silk

Dennis Raoul Whitehall Silk (8 October 193119 June 2019) was an English first-class cricketer and a public school headmaster. He was a close friend of the poet Siegfried Sassoon, of whom he spoke and wrote extensively. In the 1990s he chaired ...

who later became Warden (headmaster) of Radley College

Radley College, formally St Peter's College, Radley, is a public school (independent boarding school for boys) near Radley, Oxfordshire, England, which was founded in 1847. The school covers including playing fields, a golf course, a lake, and ...

. He also formed a close friendship with Vivien Hancock, then headmistress of Greenways School

Greenways School, also known as Greenways Preparatory School, was an English prep school, founded at Bognor Regis, Sussex, before the Second World War. In 1940 it moved to Ashton Gifford House, Codford, Wiltshire, where it remained until it w ...

at Ashton Gifford, Wiltshire, where his son George was a pupil. The relationship provoked Hester to make strong accusations against Hancock, who responded with the threat of legal action.

Religion

Towards the end of his life, Sassoon converted toCatholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. He had hoped that Ronald Knox

Ronald Arbuthnott Knox (17 February 1888 – 24 August 1957) was an Catholic Church in England and Wales, English Catholic priest, Catholic theology, theologian, author, and radio broadcaster. Educated at Eton College, Eton and Balliol Colleg ...

, a Catholic priest and writer whom he admired, would instruct him in the faith, but Knox was too ill to do so. The priest Sebastian Moore was chosen to instruct him instead, and Sassoon was admitted to the faith at Downside Abbey

Downside Abbey is a Benedictine monastery in England and the senior community of the English Benedictine Congregation. Until 2019, the community had close links with Downside School, for the education of children aged eleven to eighteen. Both t ...

in Somerset. He also paid regular visits to the nuns at Stanbrook Abbey

Stanbrook Abbey is a Catholic contemplative Benedictine women's monastery with the status of an abbey, located at Wass, North Yorkshire, England.

The community was founded in 1625 at Cambrai in Flanders (then part of the Spanish Netherlands, ...

, and the Abbey press printed commemorative editions of some of his poems. During this time he also became interested in the supernatural

Supernatural refers to phenomena or entities that are beyond the laws of nature. The term is derived from Medieval Latin , from Latin (above, beyond, or outside of) + (nature) Though the corollary term "nature", has had multiple meanings si ...

, and joined the Ghost Club

The Ghost Club is a paranormal investigation and research organization, founded in London in 1862. It is believed to be the oldest such organization in the world, though its history has not been continuous. The club still investigates mainly gho ...

.

Death and awards

Sassoon was appointedCommander of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

(CBE) in the 1951 New Year Honours

The 1951 New Years Honours were appointments in many of the Commonwealth realms of King George VI to various orders and honours to reward and highlight good works by citizens of those countries. They were announced on 1 January 1951 for the Brit ...

. He died from stomach cancer on 1 September 1967, one week before his 81st birthday. He is buried at St Andrew's Church, Mells

St Andrew's Church is a Church of England parish church located in the village of Mells in the English county of Somerset. The church is a grade I listed building.

History

The current church predominantly dates from the late 15th century ...

, Somerset, not far from the grave of Father Ronald Knox, whom he so admired. His CBE, MC and campaign medals are on display at the Royal Welch Fusiliers Museum

The Royal Welch Fusiliers Museum is a museum dedicated to the history of the Royal Welch Fusiliers, a historic regiment of the British Army. The museum is located within Caernarfon Castle in Caernarfon, Gwynedd, North Wales. Admission is include ...

at Caernarfon Castle

Caernarfon Castle ( cy, Castell Caernarfon ) – often anglicised as Carnarvon Castle or Caernarvon Castle – is a medieval fortress in Caernarfon, Gwynedd, north-west Wales cared for by Cadw, the Welsh Government's historic environ ...

.

Legacy

On 11 November 1985, Sassoon was among sixteen Great War poets commemorated on a slate stone unveiled in

On 11 November 1985, Sassoon was among sixteen Great War poets commemorated on a slate stone unveiled in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

's Poet's Corner

Poets' Corner is the name traditionally given to a section of the South Transept of Westminster Abbey in the City of Westminster, London because of the high number of poets, playwrights, and writers buried and commemorated there.

The first poe ...

. The inscription on the stone was written by friend and fellow War poet Wilfred Owen

Wilfred Edward Salter Owen MC (18 March 1893 – 4 November 1918) was an English poet and soldier. He was one of the leading poets of the First World War. His war poetry on the horrors of trenches and gas warfare was much influenced by ...

. It reads: "My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity."

The year 2003 saw the publication of ''Memorial Tablet'', an authorised audio CD of readings by Sassoon recorded during the late 1950s. These included extracts from ''Memoirs of an Infantry Officer

''Memoirs of an Infantry Officer'' is a novel by Siegfried Sassoon, first published in 1930. It is a fictionalised account of Sassoon's own life during and immediately after World War I. Soon after its release, it was heralded as a classic and ...

'' and ''The Weald of Youth'', as well as several war poems including Attack, The Dug-Out, At Carnoy and Died of Wounds, and postwar works. The CD also included comment on Sassoon by three of his Great War contemporaries: Edmund Blunden

Edmund Charles Blunden (1 November 1896 – 20 January 1974) was an English poet, author, and critic. Like his friend Siegfried Sassoon, he wrote of his experiences in World War I in both verse and prose. For most of his career, Blunden was als ...

, Edgell Rickword

John Edgell Rickword, MC (22 October 1898 – 15 March 1982) was an English poet, critic, journalist and literary editor. He became one of the leading communist intellectuals active in the 1930s.

Early life

He was born in Colchester, Essex, ...

and Henry Williamson

Henry William Williamson (1 December 1895 – 13 August 1977) was an English writer who wrote novels concerned with wildlife, English social history and ruralism. He was awarded the Hawthornden Prize for literature in 1928 for his book ''Tarka ...

.

Siegfried Sassoon's only child, George Sassoon

George Thornycroft Sassoon (30 October 1936 – 8 March 2006) was a British scientist, electronic engineer, linguist, translator and author.

Early life

Sassoon was the only child of the poet Siegfried Sassoon and Hester Sassoon (née Gatty), and ...

, died of cancer in 2006. George had three children, two of whom were killed in a car crash in 1996. His daughter by his first marriage, Kendall Sassoon, is Patron-in-Chief of the Siegfried Sassoon Fellowship, established in 2001.

Sassoon's Military Cross

The Military Cross (MC) is the third-level (second-level pre-1993) military decoration awarded to officers and (since 1993) other ranks of the British Armed Forces, and formerly awarded to officers of other Commonwealth countries.

The MC i ...

was rediscovered by his family in May 2007 and was put up for sale. It was bought by the Royal Welch Fusiliers

The Royal Welch Fusiliers ( cy, Ffiwsilwyr Brenhinol Cymreig) was a line infantry regiment of the British Army, and part of the Prince of Wales' Division, that was founded in 1689; shortly after the Glorious Revolution. In 1702, it was designated ...

for display at their museum in Caernarfon

Caernarfon (; ) is a royal town, community and port in Gwynedd, Wales, with a population of 9,852 (with Caeathro). It lies along the A487 road, on the eastern shore of the Menai Strait, opposite the Isle of Anglesey. The city of Bangor is ...

. Sassoon's other service medals went unclaimed until 1985 when his son George obtained them from the Army Medal Office, then based at Droitwich

Droitwich Spa (often abbreviated to Droitwich ) is an historic spa town in the Wychavon district in northern Worcestershire, England, on the River Salwarpe. It is located approximately south-west of Birmingham and north-east of Worcester.

The ...

. The "late claim" medals consisting of the 1914–15 Star

The 1914–15 Star is a campaign medal of the British Empire which was awarded to officers and men of British and Imperial forces who served in any theatre of the First World War against the Central European Powers during 1914 and 1915. The me ...

, Victory Medal and British War Medal

The British War Medal is a campaign medal of the United Kingdom which was awarded to officers and men of British and Imperial forces for service in the First World War. Two versions of the medal were produced. About 6.5 million were struck in si ...

along with Sassoon's CBE

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

and Warrant of Appointment were auctioned by Sotheby's

Sotheby's () is a British-founded American multinational corporation with headquarters in New York City. It is one of the world's largest brokers of fine and decorative art, jewellery, and collectibles. It has 80 locations in 40 countries, and ...

in 2008.

In June 2009, the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

announced plans to purchase an archive of Sassoon's papers from his family, to be added to the university library's Sassoon collection. On 4 November 2009 it was reported that this purchase would be supported by £550,000 from the National Heritage Memorial Fund

The National Heritage Memorial Fund (NHMF) was set up in 1980 to save the most outstanding parts of the British national heritage, in memory of those who have given their lives for the UK. It replaced the National Land Fund which had fulfilled the ...

, meaning that the University still needed to raise a further £110,000 on top of the money already received to meet the full £1.25 million asking price. The funds were raised and in December 2009 it was announced that the University had received the papers. Included in the collection are war diaries kept by Sassoon while he served on the Western Front and in Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

, a draft of "A Soldier's Declaration

Siegfried Loraine Sassoon (8 September 1886 – 1 September 1967) was an English war poet, writer, and soldier. Decorated for bravery on the Western Front, he became one of the leading poets of the First World War. His poetry both describe ...

" (1917), notebooks from his schooldays and post-war journals. Other items in the collection include love letters to his wife Hester and photographs and letters from other writers. Sassoon was an undergraduate at the university, as well as being made an honorary fellow of Clare College

Clare College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge in Cambridge, England. The college was founded in 1326 as University Hall, making it the second-oldest surviving college of the University after Peterhouse. It was refounded ...

; the collection is housed at the Cambridge University Library

Cambridge University Library is the main research library of the University of Cambridge. It is the largest of the over 100 libraries within the university. The Library is a major scholarly resource for the members of the University of Cambri ...

. As well as private individuals, funding came from the Monument Trust, the JP Getty Jr Trust and Sir Siegmund Warburg

Sir Siegmund George Warburg (30 September 1902 – 18 October 1982) was a German-born English banker. He was a member of the prominent Warburg family. He played a prominent role in the development of merchant banking.Cyril Rootham

Cyril Bradley Rootham (5 October 1875 – 18 March 1938) was an English composer, educator and organist. His work at Cambridge University made him an influential figure in English music life. A Fellow of St John's College, where he was also or ...

, who co-operated with the author.

The discovery in 2013 of an early draft of one of Sassoon's best-known anti-war poems had biographers saying they would rewrite portions of their work about the poet. In the poem, 'Atrocities', which concerned the killing of German prisoners by their British counterparts, the early draft shows that some lines were cut and others watered down. The poet's publisher was nervous about publishing the poem and held it for publication in an expurgated version at a later date. Sassoon biographer Jean Moorcroft Wilson

Jean Moorcroft Wilson (born 3 October 1941) is a British academic and writer, best known as a biographer and critic of First World War poets and poetry.

A lecturer in English at Birkbeck, University of London, she has written a two-volume biogra ...

said "This is very exciting material. I want to rewrite my biography and I probably shall be able to get some of it in. It's a treasure trove". In early 2019, it was announced in ''The Guardian'' newspaper that a student from the University of Warwick, whilst looking through Glen Byam Shaw's records at the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, had serendipitously discovered a Sassoon poem addressed to the former, which had not been published in its entirety.

Books

Poetry collections

* ''The Daffodil Murderer'' (John Richmond: 1913)

* '' The Old Huntsman'' (

* ''The Daffodil Murderer'' (John Richmond: 1913)

* '' The Old Huntsman'' (Heinemann Heinemann may refer to:

* Heinemann (surname)

* Heinemann (publisher), a publishing company

* Heinemann Park, a.k.a. Pelican Stadium in New Orleans, Louisiana, United States

See also

* Heineman

* Jamie Hyneman

James Franklin Hyneman (born Se ...

: 1917)

* ''The General'' (Denmark Hill Hospital, April 1917)

* ''Does it Matter?'' (written: 1917)

* '' Counter-Attack and Other Poems'' (Heinemann: 1918)

* ''The Hero'' enry Holt, 1918* ''Picture-Show'' (Heinemann: 1919)

* ''War Poems'' (Heinemann: 1919)

* ''Aftermath'' (Heinemann: 1920)

* ''Recreations'' (privately printed: 1923)

* ''Lingual Exercises for Advanced Vocabularians'' (privately printed: 1925)

* ''Selected Poems'' (Heinemann: 1925)

* ''Satirical Poems'' (Heinemann: 1926)

* ''The Heart's Journey'' (Heinemann: 1928)

* ''Poems by Pinchbeck Lyre'' (Duckworth Duckworth may refer to:

* Duckworth (surname), people with the surname ''Duckworth''

* Duckworth (''DuckTales''), fictional butler from the television series ''DuckTales''

* Duckworth Books, a British publishing house

* , a frigate

* Duckworth, W ...

: 1931)

* ''The Road to Ruin'' (Faber and Faber

Faber and Faber Limited, usually abbreviated to Faber, is an independent publishing house in London. Published authors and poets include T. S. Eliot (an early Faber editor and director), W. H. Auden, Margaret Storey, William Golding, Samuel B ...

: 1933)

* ''Vigils'' (Heinemann: 1935)

* ''Rhymed Ruminations'' (Faber and Faber: 1940)

* ''Poems Newly Selected'' (Faber and Faber: 1940)

* ''Collected Poems'' (Faber and Faber: 1947)

* ''Common Chords'' (privately printed: 1950/1951)

* ''Emblems of Experience'' (privately printed: 1951)

* ''The Tasking'' (privately printed: 1954)

* ''Sequences'' (Faber and Faber: 1956)

* ''Lenten Illuminations'' (Downside Abbey: 1959)

* ''The Path to Peace'' ( Stanbrook Abbey Press: 1960)

* ''Collected Poems 1908–1956'' (Faber and Faber: 1961)

* ''The War Poems'' ed. Rupert Hart-Davis

Sir Rupert Charles Hart-Davis (28 August 1907 – 8 December 1999) was an English publisher and editor. He founded the publishing company Rupert Hart-Davis Ltd. As a biographer, he is remembered for his ''Hugh Walpole'' (1952), as an editor, f ...

(Faber and Faber: 1983)

Prose books

* ''

* ''Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man

''Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man'' is a novel by Siegfried Sassoon, first published in 1928 by Faber and Faber. It won both the Hawthornden Prize and the James Tait Black Memorial Prize, being immediately recognised as a classic of English literat ...

'' (Faber & Gwyer: 1928)

* ''Memoirs of an Infantry Officer

''Memoirs of an Infantry Officer'' is a novel by Siegfried Sassoon, first published in 1930. It is a fictionalised account of Sassoon's own life during and immediately after World War I. Soon after its release, it was heralded as a classic and ...

'' (Faber and Faber: 1930)

* ''Sherston's Progress

''Sherston's Progress'' is the final book of Siegfried Sassoon's semi-autobiographical trilogy. It is preceded by ''Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man'' and '' Memoirs of an Infantry Officer''.

Synopsis

The book starts with his arrival at 'Slateford ...

'' (Faber and Faber: 1936)

* ''The Complete Memoirs of George Sherston'' (Faber and Faber: 1937)

* ''The Old Century and seven more years'' (Faber and Faber: 1938)

* ''On Poetry'' (University of Bristol Press: 1939)

* ''The Weald of Youth'' (Faber and Faber: 1942)

* ''Siegfried's Journey, 1916–1920'' (Faber and Faber: 1945)

* ''Meredith'' (Constable: 1948) – Biography of George Meredith

George Meredith (12 February 1828 – 18 May 1909) was an English novelist and poet of the Victorian era. At first his focus was poetry, influenced by John Keats among others, but he gradually established a reputation as a novelist. ''The Ord ...

In popular culture

A 1970 installment ofThe Wednesday Play

''The Wednesday Play'' is an anthology series of United Kingdom, British television plays which ran on BBC One, BBC1 for six seasons from October 1964 to May 1970. The plays were usually original works written for television, although dramati ...

entitled ''Mad Jack'' based around Sassoon's wartime experiences and their aftermath leading to his renunciation of his Military Cross starred Michael Jayston

Michael James (born 29 October 1935), known professionally as Michael Jayston, is an English actor. He played Nicholas II of Russia in the film ''Nicholas and Alexandra'' (1971). He has also made many television appearances, which have include ...

as Sassoon. The novel ''Regeneration

Regeneration may refer to:

Science and technology

* Regeneration (biology), the ability to recreate lost or damaged cells, tissues, organs and limbs

* Regeneration (ecology), the ability of ecosystems to regenerate biomass, using photosynthesis

...

'', by Pat Barker

Patricia Mary W. Barker, (née Drake; born 8 May 1943) is an English writer and novelist. She has won many awards for her fiction, which centres on themes of memory, trauma, survival and recovery. Her work is described as direct, blunt and pl ...

, is a fictionalised account of this period in Sassoon's life, and was made into a film

A film also called a movie, motion picture, moving picture, picture, photoplay or (slang) flick is a work of visual art that simulates experiences and otherwise communicates ideas, stories, perceptions, feelings, beauty, or atmosphere ...

starring James Wilby

James Jonathon Wilby (born 20 February 1958) is an English actor.

Early life and education

Wilby was born in Rangoon, Burma to a corporate executive father. He was educated at Terrington Hall School, North Yorkshire and Sedbergh School in Cu ...

as Sassoon and Jonathan Pryce

Sir Jonathan Pryce (born John Price; 1 June 1947) is a Welsh actor who is known for his performances on stage and in film and television. He has received numerous awards, including two Tony Awards and two Laurence Olivier Awards. In 2021 he wa ...

as W. H. R. Rivers, the psychiatrist responsible for Sassoon's treatment. Rivers became a kind of surrogate father to the troubled young man, and his sudden death in 1922 was a major blow to Sassoon.

In 2014, John Hurt

Sir John Vincent Hurt (22 January 1940 – 25 January 2017) was an English actor whose career spanned over five decades. Hurt was regarded as one of Britain's finest actors. Director David Lynch described him as "simply the greatest actor in t ...

played the older Sassoon and Morgan Watkins the young Sassoon in '' The Pity of War'', a BBC docu-drama.

A film named ''The Burying Party'' (released August 2018) depicts Wilfred Owen

Wilfred Edward Salter Owen MC (18 March 1893 – 4 November 1918) was an English poet and soldier. He was one of the leading poets of the First World War. His war poetry on the horrors of trenches and gas warfare was much influenced by ...

's final year from Craiglockhart Hospital to the Battle of the Sambre (1918)

The Second Battle of the Sambre (4 November 1918) (which included the Second Battle of Guise (french: 2ème Bataille de Guise) and the Battle of Thiérache (french: Bataille de Thiérache) was part of the final European Allied offensives of Worl ...

, including his meeting with Sassoon at the hospital. Matthew Staite stars as Owen and Sid Phoenix as Sassoon.

Peter Capaldi

Peter Dougan Capaldi (; born 14 April 1958) is a Scottish actor, director, writer and musician. He portrayed the Twelfth Doctor, twelfth incarnation of The Doctor (Doctor Who), the Doctor in ''Doctor Who'' (2013–2017) and Malcolm Tucker in ' ...

and Jack Lowden

Jack Andrew Lowden (born 2 June 1990) is a Scottish actor. Following a four-year stage career, his first major international onscreen success was in the 2016 BBC miniseries '' War & Peace'', which led to starring roles in feature films.

Lowden s ...

portrayed Sassoon in Terence Davies

Terence Davies (born 10 November 1945) is an English screenwriter, film director, and novelist, seen by many critics as one of the greatest British filmmakers of his times. He is best known as the writer and director of autobiographical films ...

' 2021 film ''Benediction

A benediction (Latin: ''bene'', well + ''dicere'', to speak) is a short invocation for divine help, blessing and guidance, usually at the end of worship service. It can also refer to a specific Christian religious service including the expositio ...

''.

Stevan Rimkus portrayed Sassoon in The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles

''The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles'' is an American television series that aired on ABC from March 4, 1992, to July 24, 1993. Filming took place in various locations around the world, with "Old Indy" bookend segments filmed in Wilmington, North ...

episode, ''Somme, Early August 1916''.

Footnotes

References

*Felicitas Corrigan

Dame Felicitas Corrigan OSB (6 March 1908 – 7 October 2003, Kathleen Corrigan) was an English Benedictine nun, author and humanitarian.

Biography

Corrigan was born in Liverpool in 1908 to a large family. She learned to play the organ at an ...

, ''Siegfried Sassoon: Poet's Pilgrimage'' (1973). (A collection of Sassoon's diary-entries and correspondence marking his gradual spiritual development towards Roman Catholicism.)

* Jean Moorcroft Wilson

Jean Moorcroft Wilson (born 3 October 1941) is a British academic and writer, best known as a biographer and critic of First World War poets and poetry.

A lecturer in English at Birkbeck, University of London, she has written a two-volume biogra ...

, ''Siegfried Sassoon: The Making of a War Poet'' (1998).

* Jean Moorcroft Wilson

Jean Moorcroft Wilson (born 3 October 1941) is a British academic and writer, best known as a biographer and critic of First World War poets and poetry.

A lecturer in English at Birkbeck, University of London, she has written a two-volume biogra ...

, ''Siegfried Sassoon: The Journey from the Trenches: a biography (1918–1967)'' (London: Routledge, 2003).

* John Stuart Roberts, ''Siegfried Sassoon'' (1999).

* Max Egremont

John Max Henry Scawen Wyndham, 7th Baron Leconfield, 2nd Baron Egremont FRSL DL (born 21 April 1948), generally known as Max Egremont, is a British biographer and novelist. Egremont is the eldest son of John Edward Reginald Wyndham, 6th Baron ...

, ''Siegfried Sassoon: A Biography'' (2005).

''Siegfried's Journal'': the journal of the Siegfried Sassoon Fellowship.

Sassoon on the War poets from ''Vanity Fair'' magazine (1920

Further reading

* * Roy Pinaki. "''Comrades-in-Arms'': A Very Brief Study of Sassoon and Owen as Twentieth-Century English War Poets". ''Twentieth-century British Literature: Reconstructing Literary Sensibility''. Ed. Nawale, A., Z. Mitra, and A. John. New Delhi: Gnosis, 2013 (). pp. 61–78.Siegfried Sassoon collection of papers, 1905–1975, bulk (1915–1951)

(669 items) are held at the

New York Public Library

The New York Public Library (NYPL) is a public library system in New York City. With nearly 53 million items and 92 locations, the New York Public Library is the second largest public library in the United States (behind the Library of Congress ...

.

Siegfried Sassoon papers, 1894–1966

(3 linear ft. (ca.630 items in 4 boxes & 13 slipcases)) are held at

Columbia University Libraries

Columbia University Libraries is the library system of Columbia University and one of the largest academic library systems in North America. With 15.0 million volumes and over 160,000 journals and serials, as well as extensive electronic resources ...

.

Siegfried Sassoon papers, 1908–1966

(109 items) are held in the

Rutgers University Libraries

Rutgers University (; RU), officially Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, is a public land-grant research university consisting of four campuses in New Jersey. Chartered in 1766, Rutgers was originally called Queen's College, and was a ...

.

* 'The Jewishness of Siegfried Sassoon' by Martin Sugarman (AJEX Archivist) in the Journal of the Siegfried Fellowship

External links

* * * *Profile at Poetry Foundation

1920 *Vanity Fair* magazine article by Sassoon

Profile at Poetry Archive. Biography and poems written and audio

The Siegfried Sassoon Fellowship

Siegfried Sassoon profile and poems at Poets.org

BBC: ''In our time''. (Audio discussion 45 mins)

with bibliography and links. Updated 18-Mar-15

BBC

interview 1 January 1967 (Audio, 7 mins) Dead link Updated 18-Mar-15

WGBH Forum Network lecture

given by Sassoon biographer

Max Egremont

John Max Henry Scawen Wyndham, 7th Baron Leconfield, 2nd Baron Egremont FRSL DL (born 21 April 1948), generally known as Max Egremont, is a British biographer and novelist. Egremont is the eldest son of John Edward Reginald Wyndham, 6th Baron ...

(Audio and video, 1 hour)

Siegfried Sassoon collection of papers, circa 1905–1975, bulk (1915–1951)

(669 items),

New York Public Library

The New York Public Library (NYPL) is a public library system in New York City. With nearly 53 million items and 92 locations, the New York Public Library is the second largest public library in the United States (behind the Library of Congress ...

.

*

Papers of Siegfried Sassoon

Cambridge University Library

Cambridge University Library is the main research library of the University of Cambridge. It is the largest of the over 100 libraries within the university. The Library is a major scholarly resource for the members of the University of Cambri ...

Sassoon in the Great War Archive

Oxford University/

Jisc

Jisc is a United Kingdom not-for-profit company that provides network and IT services and digital resources in support of further and higher education institutions and research as well as not-for-profits and the public sector.

History

T ...

.

BBC Audio slideshow.

Sassoon's papers at Cambridge University Library.

Elizabeth Whitcomb Houghton Collection

Sassoon archive

Sassoon Journals

digitised in

Cambridge Digital Library

The Cambridge Digital Library is a project operated by the Cambridge University Library designed to make items from the unique and distinctive collections of Cambridge University Library available online. The project was initially funded by a donat ...

* Archival material at

Finding aid to Siegfried Sassoon papers

at Columbia University, Rare Book & Manuscript Library * Siegfried Sassoon Papers. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. {{DEFAULTSORT:Sassoon, Siegfried 1886 births 1967 deaths British Army personnel of World War I English World War I poets People with post-traumatic stress disorder 20th-century male writers Commanders of the Order of the British Empire Converts to Roman Catholicism from Judaism English Catholic poets English diarists English memoirists English people of Indian-Jewish descent English people of Iraqi-Jewish descent English Roman Catholics Fox hunters Fox hunting writers James Tait Black Memorial Prize recipients Bisexual men Bisexual military personnel LGBT Roman Catholics People educated at Marlborough College People from Matfield Recipients of the Military Cross Roman Catholic writers Royal Welch Fusiliers officers Sassoon family Thornycroft family War writers 20th-century English poets Alumni of Clare College, Cambridge English LGBT poets Burials in Somerset Sussex Yeomanry soldiers Bisexual writers British writers of Indian descent Baghdadi Jews Military personnel from Kent