APSV on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A shell, in a

A shell, in a

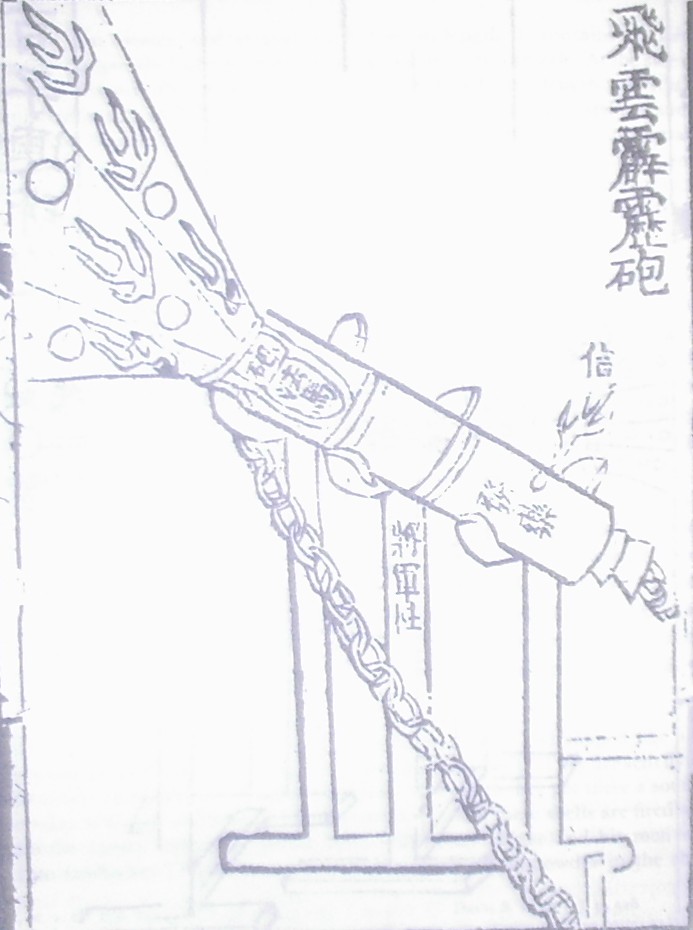

Cast iron shells packed with gunpowder have been used in warfare since at least early 13th century China. Hollow, gunpowder-packed shells made of

Cast iron shells packed with gunpowder have been used in warfare since at least early 13th century China. Hollow, gunpowder-packed shells made of  By the 18th century, it was known that the fuse toward the muzzle could be lit by the flash through the

By the 18th century, it was known that the fuse toward the muzzle could be lit by the flash through the

Advances in metallurgy in the industrial era allowed for the construction of rifled breech-loading guns that could fire at a much greater

Advances in metallurgy in the industrial era allowed for the construction of rifled breech-loading guns that could fire at a much greater

Although an early percussion fuze appeared in 1650 that used a flint to create sparks to ignite the powder, the shell had to fall in a particular way for this to work and this did not work with spherical projectiles. An additional problem was finding a suitably stable "percussion powder". Progress was not possible until the discovery of

Although an early percussion fuze appeared in 1650 that used a flint to create sparks to ignite the powder, the shell had to fall in a particular way for this to work and this did not work with spherical projectiles. An additional problem was finding a suitably stable "percussion powder". Progress was not possible until the discovery of

In 1884,

In 1884,

A variety of fillings have been used in shells throughout history. An incendiary shell was invented by Valturio in 1460. The

A variety of fillings have been used in shells throughout history. An incendiary shell was invented by Valturio in 1460. The

Extended-range shells are sometimes used. These special shell designs may be

Extended-range shells are sometimes used. These special shell designs may be

The

The  Gun calibers have standardized around a few common sizes, especially in the larger range, mainly due to the uniformity required for efficient military logistics. Artillery shells of 105 and 155 mm for artillery with 105 and 120 mm for

Gun calibers have standardized around a few common sizes, especially in the larger range, mainly due to the uniformity required for efficient military logistics. Artillery shells of 105 and 155 mm for artillery with 105 and 120 mm for

There are many different types of shells. The principal ones include:

There are many different types of shells. The principal ones include:

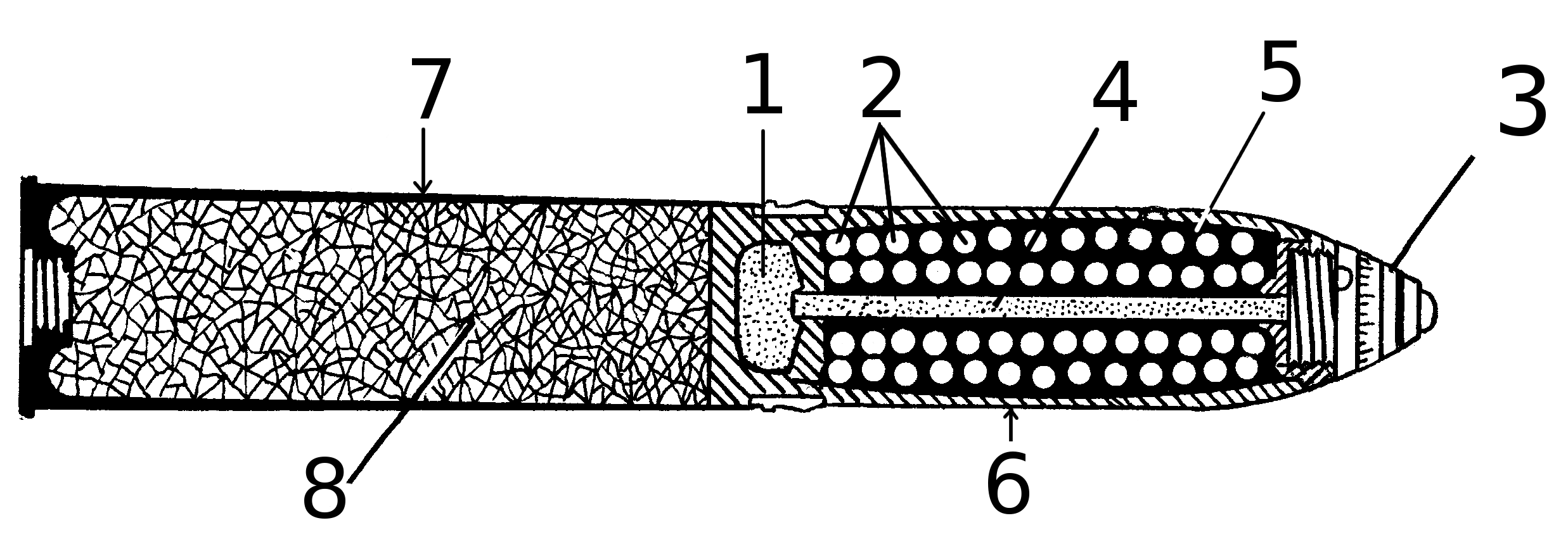

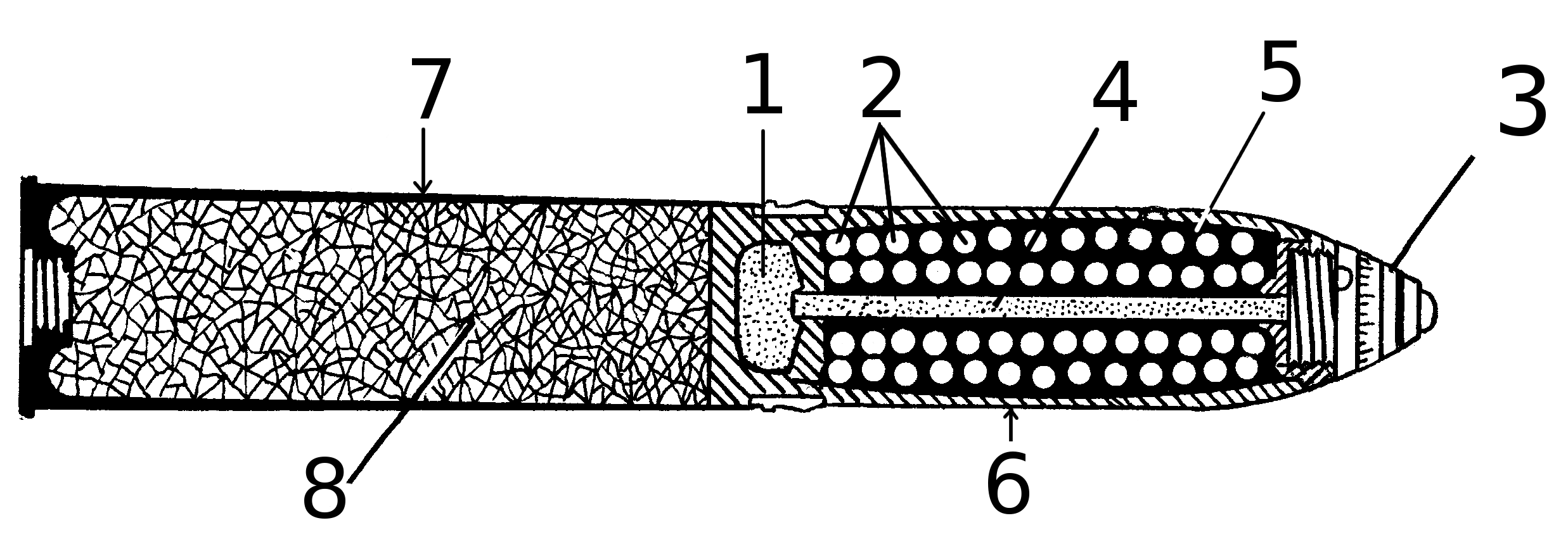

Although smokeless powders were used as a propellant, they could not be used as the substance for the explosive warhead, because shock sensitivity sometimes caused

Although smokeless powders were used as a propellant, they could not be used as the substance for the explosive warhead, because shock sensitivity sometimes caused  The most common shell type is

The most common shell type is

Common shells designated in the early (i.e. 1800s) British explosive shells were filled with "low explosives" such as "P mixture" (gunpowder) and usually with a fuze in the nose. Common shells on bursting (non-detonating) tended to break into relatively large fragments which continued along the shell's trajectory rather than laterally. They had some incendiary effect.

In the late 19th century "double common shells" were developed, lengthened so as to approach twice the standard shell weight, to carry more powder and hence increase explosive effect. They suffered from instability in flight and low velocity and were not widely used.

In 1914, common shells with a diameter of 6-inches and larger were of cast steel, while smaller diameter shells were of forged steel for service and cast iron for practice. They were replaced by "common lyddite" shells in the late 1890s but some stocks remained as late as 1914. In British service common shells were typically painted black with a red band behind the nose to indicate the shell was filled.

Common shells designated in the early (i.e. 1800s) British explosive shells were filled with "low explosives" such as "P mixture" (gunpowder) and usually with a fuze in the nose. Common shells on bursting (non-detonating) tended to break into relatively large fragments which continued along the shell's trajectory rather than laterally. They had some incendiary effect.

In the late 19th century "double common shells" were developed, lengthened so as to approach twice the standard shell weight, to carry more powder and hence increase explosive effect. They suffered from instability in flight and low velocity and were not widely used.

In 1914, common shells with a diameter of 6-inches and larger were of cast steel, while smaller diameter shells were of forged steel for service and cast iron for practice. They were replaced by "common lyddite" shells in the late 1890s but some stocks remained as late as 1914. In British service common shells were typically painted black with a red band behind the nose to indicate the shell was filled.

Common pointed shells, or CP were a type of common shell used in naval service from the 1890s – 1910s which had a solid nose and a percussion fuze in the base rather than the common shell's nose fuze. The ogival two C.R.H. solid pointed nose was considered suitable for attacking shipping but was not armor-piercing – the main function was still explosive. They were of cast or forged (three- and six-pounder) steel and contained a gunpowder bursting charge slightly smaller than that of a common shell, a trade off for the longer heavier nose.

In British service common pointed shells were typically painted black, except 12-pounder shells specific for QF guns which were painted lead colour to distinguish them from 12-pounder shells usable with both BL and QF guns. A red ring behind the nose indicated the shell was filled.

By World War II they were superseded in Royal Navy service by common pointed capped (CPC) and semi-armor piercing (

Common pointed shells, or CP were a type of common shell used in naval service from the 1890s – 1910s which had a solid nose and a percussion fuze in the base rather than the common shell's nose fuze. The ogival two C.R.H. solid pointed nose was considered suitable for attacking shipping but was not armor-piercing – the main function was still explosive. They were of cast or forged (three- and six-pounder) steel and contained a gunpowder bursting charge slightly smaller than that of a common shell, a trade off for the longer heavier nose.

In British service common pointed shells were typically painted black, except 12-pounder shells specific for QF guns which were painted lead colour to distinguish them from 12-pounder shells usable with both BL and QF guns. A red ring behind the nose indicated the shell was filled.

By World War II they were superseded in Royal Navy service by common pointed capped (CPC) and semi-armor piercing (

Common lyddite shells were British explosive shells filled with

Common lyddite shells were British explosive shells filled with

"Shrapnel Shell Manufacture. A Comprehensive Treatise.". New York: Industrial Press, 1915, Page 13

/ref> The effect was of a large shotgun blast just in front of and above the target, and was deadly against troops in the open. A trained gun team could fire 20 such shells per minute, with a total of 6,000 balls, which compared very favorably with rifles and machine-guns. However, shrapnel's relatively flat trajectory (it depended mainly on the shell's velocity for its lethality, and was lethal only in the forward direction) meant that it could not strike trained troops who avoided open spaces and instead used dead ground (dips), shelters, trenches, buildings, and trees for cover. It was of no use in destroying buildings or shelters. Hence, it was replaced during World War I by the high-explosive shell, which exploded its fragments in all directions (and thus more difficult to avoid) and could be fired by high-angle weapons, such as howitzers.

Chemical shells contain just a small explosive charge to burst the shell, and a larger quantity of a

Chemical shells contain just a small explosive charge to burst the shell, and a larger quantity of a

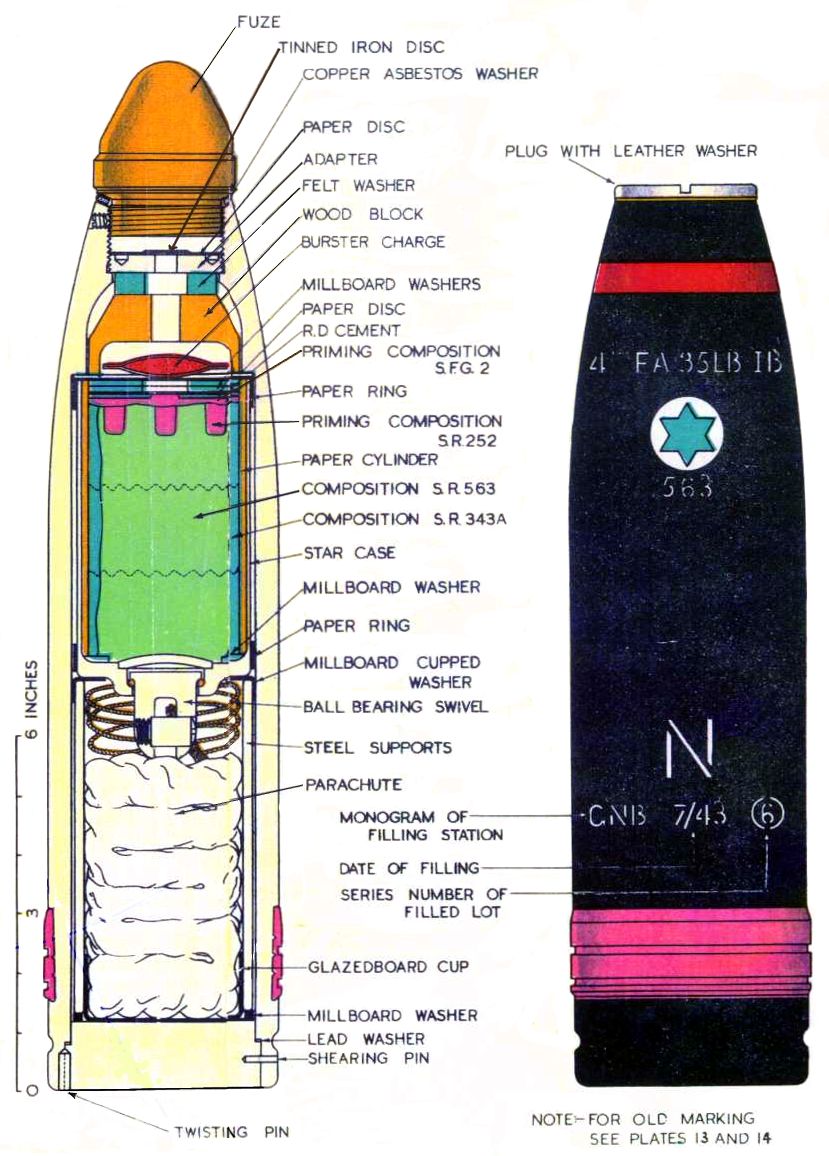

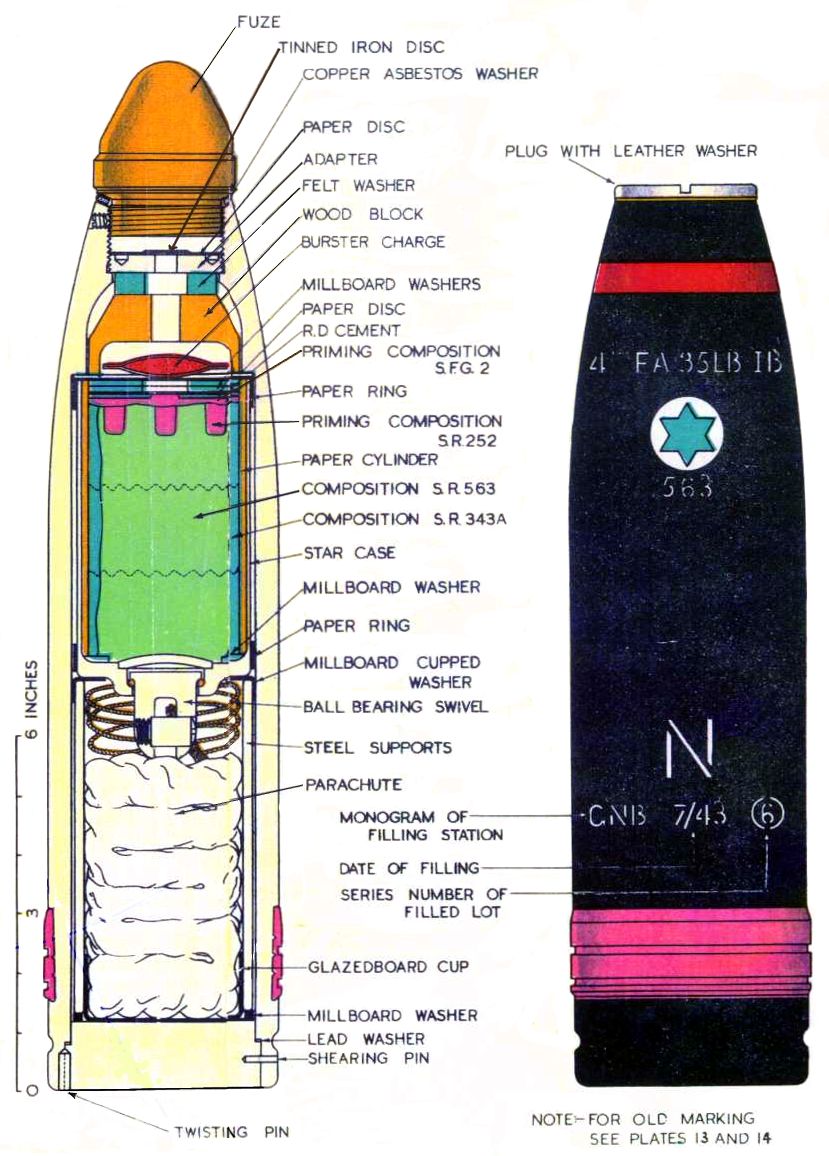

Modern illuminating shells are a type of carrier shell or cargo munition. Those used in World War I were shrapnel pattern shells ejecting small burning "pots".

A modern illumination shell has a time fuze that ejects a flare "package" through the base of the carrier shell at a standard height above ground (typically about 600 metres), from where it slowly falls beneath a non-flammable

Modern illuminating shells are a type of carrier shell or cargo munition. Those used in World War I were shrapnel pattern shells ejecting small burning "pots".

A modern illumination shell has a time fuze that ejects a flare "package" through the base of the carrier shell at a standard height above ground (typically about 600 metres), from where it slowly falls beneath a non-flammable  Typically illumination flares burn for about 60 seconds. These are also known as ''starshell'' or ''star shell''. Infrared illumination is a more recent development used to enhance the performance of night-vision devices. Both white- and black-light illuminating shells may be used to provide continuous illumination over an area for a period of time and may use several dispersed aimpoints to illuminate a large area. Alternatively, firing single illuminating shells may be coordinated with the adjustment of HE shell fire onto a target.

Colored flare shells have also been used for target marking and other signaling purposes.

Typically illumination flares burn for about 60 seconds. These are also known as ''starshell'' or ''star shell''. Infrared illumination is a more recent development used to enhance the performance of night-vision devices. Both white- and black-light illuminating shells may be used to provide continuous illumination over an area for a period of time and may use several dispersed aimpoints to illuminate a large area. Alternatively, firing single illuminating shells may be coordinated with the adjustment of HE shell fire onto a target.

Colored flare shells have also been used for target marking and other signaling purposes.

Image:XM982 Excalibur inert.jpg,

Sometimes, one or more of these arming mechanisms fail, resulting in a projectile that is unable to detonate. More worrying (and potentially far more hazardous) are fully armed shells on which the fuze fails to initiate the HE firing. This may be due to a shallow trajectory of fire, low-velocity firing or soft impact conditions. Whatever the reason for failure, such a shell is called a ''blind'' or ''unexploded ordnance ( UXO)'' (the older term, "dud", is discouraged because it implies that the shell ''cannot'' detonate.) Blind shells often litter old battlefields; depending on the impact velocity, they may be buried some distance into the earth, all the while remaining potentially hazardous. For example, antitank ammunition with a piezoelectric fuze can be detonated by relatively light impact to the piezoelectric element, and others, depending on the type of fuze used, can be detonated by even a small movement. The battlefields of the First World War still claim casualties today from leftover munitions. Modern electrical and mechanical fuzes are highly reliable: if they do not arm correctly, they keep the initiation train out of line or (if electrical in nature) discharge any stored electrical energy.

Sometimes, one or more of these arming mechanisms fail, resulting in a projectile that is unable to detonate. More worrying (and potentially far more hazardous) are fully armed shells on which the fuze fails to initiate the HE firing. This may be due to a shallow trajectory of fire, low-velocity firing or soft impact conditions. Whatever the reason for failure, such a shell is called a ''blind'' or ''unexploded ordnance ( UXO)'' (the older term, "dud", is discouraged because it implies that the shell ''cannot'' detonate.) Blind shells often litter old battlefields; depending on the impact velocity, they may be buried some distance into the earth, all the while remaining potentially hazardous. For example, antitank ammunition with a piezoelectric fuze can be detonated by relatively light impact to the piezoelectric element, and others, depending on the type of fuze used, can be detonated by even a small movement. The battlefields of the First World War still claim casualties today from leftover munitions. Modern electrical and mechanical fuzes are highly reliable: if they do not arm correctly, they keep the initiation train out of line or (if electrical in nature) discharge any stored electrical energy.

"High-explosive shell manufacture; a comprehensive treatise"

New York: Industrial Press, 1916. * Douglas T. Hamilton

"Shrapnel Shell Manufacture. A Comprehensive Treatise"

New York: Industrial Press, 1915. * Hogg, O. F. G. 1970. "Artillery: its origin, heyday and decline". London: C. Hurst and Company.

"What Happens When a Shell Bursts," ''Popular Mechanics'', April 1906, p. 408

– with photograph of exploded shell reassembled * : A website about airdropped, shelled or rocket fired propaganda leaflets. Example artillery shells for spreading propaganda.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Shell (Projectile) Artillery ammunition Explosive projectiles Chinese inventions Gunpowder

A shell, in a

A shell, in a military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

context, is a projectile

A projectile is an object that is propelled by the application of an external force and then moves freely under the influence of gravity and air resistance. Although any objects in motion through space are projectiles, they are commonly found in ...

whose payload contains an explosive

An explosive (or explosive material) is a reactive substance that contains a great amount of potential energy that can produce an explosion if released suddenly, usually accompanied by the production of light, heat, sound, and pressure. An expl ...

, incendiary, or other chemical

A chemical substance is a form of matter having constant chemical composition and characteristic properties. Some references add that chemical substance cannot be separated into its constituent elements by physical separation methods, i.e., wi ...

filling. Originally it was called a bombshell, but "shell" has come to be unambiguous in a military context. Modern usage sometimes includes large solid kinetic projectile

A kinetic energy weapon (also known as kinetic weapon, kinetic energy warhead, kinetic warhead, kinetic projectile, kinetic kill vehicle) is a weapon based solely on a projectile's kinetic energy instead of an explosive or any other kind of payl ...

s that is properly termed shot. Solid shot may contain a pyrotechnic compound if a tracer or spotting charge is used.

All explosive- and incendiary-filled projectiles, particularly for mortars, were originally called ''grenades'', derived from the French word for pomegranate

The pomegranate (''Punica granatum'') is a fruit-bearing deciduous shrub in the family Lythraceae, subfamily Punicoideae, that grows between tall.

The pomegranate was originally described throughout the Mediterranean Basin, Mediterranean re ...

, so called because of the similarity of shape and that the multi-seeded fruit resembles the powder-filled, fragmentizing bomb. Words cognate with ''grenade'' are still used for an artillery or mortar projectile in some European languages.

Shells are usually large-caliber projectiles fired by artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

, armored fighting vehicle

An armoured fighting vehicle (AFV) is an armed combat vehicle protected by armour, generally combining operational mobility with offensive and defensive capabilities. AFVs can be wheeled or tracked. Examples of AFVs are tanks, armoured cars, ...

s (e.g. tank

A tank is an armoured fighting vehicle intended as a primary offensive weapon in front-line ground combat. Tank designs are a balance of heavy firepower, strong armour, and good battlefield mobility provided by tracks and a powerful engin ...

s, assault gun

Assault gun (from german: Sturmgeschütz - "storm gun", as in "storming/assaulting") is a type of self-propelled artillery which uses an infantry support gun mounted on a motorized chassis, normally an armored fighting vehicle, which are designed ...

s, and mortar carrier

A mortar carrier, or self-propelled mortar, is a self-propelled artillery piece in which a mortar is the primary weapon. Simpler vehicles carry a standard infantry mortar while in more complex vehicles the mortar is fully integrated into the ...

s), warship

A warship or combatant ship is a naval ship that is built and primarily intended for naval warfare. Usually they belong to the armed forces of a state. As well as being armed, warships are designed to withstand damage and are usually faster a ...

s, and autocannon

An autocannon, automatic cannon or machine cannon is a fully automatic gun that is capable of rapid-firing large-caliber ( or more) armour-piercing, explosive or incendiary shells, as opposed to the smaller-caliber kinetic projectiles (bull ...

s. The shape is usually a cylinder

A cylinder (from ) has traditionally been a three-dimensional solid, one of the most basic of curvilinear geometric shapes. In elementary geometry, it is considered a prism with a circle as its base.

A cylinder may also be defined as an infin ...

topped by an ogive

An ogive ( ) is the roundly tapered end of a two-dimensional or three-dimensional object. Ogive curves and surfaces are used in engineering, architecture and woodworking.

Etymology

The earliest use of the word ''ogive'' is found in the 13th c ...

-tipped nose cone

A nose cone is the conically shaped forwardmost section of a rocket, guided missile or aircraft, designed to modulate oncoming airflow behaviors and minimize aerodynamic drag. Nose cones are also designed for submerged watercraft such a ...

for good aerodynamic

Aerodynamics, from grc, ἀήρ ''aero'' (air) + grc, δυναμική (dynamics), is the study of the motion of air, particularly when affected by a solid object, such as an airplane wing. It involves topics covered in the field of fluid dyn ...

performance

A performance is an act of staging or presenting a play, concert, or other form of entertainment. It is also defined as the action or process of carrying out or accomplishing an action, task, or function.

Management science

In the work place ...

, and possibly with a tapered boat tail; but some specialized types differ widely.

Background

Gunpowder is alow explosive

An explosive (or explosive material) is a reactive substance that contains a great amount of potential energy that can produce an explosion if released suddenly, usually accompanied by the production of light, heat, sound, and pressure. An expl ...

, meaning it will not create a concussive, brisant explosion unless it is contained, as in a modern-day pipe bomb

A pipe bomb is an improvised explosive device which uses a tightly sealed section of pipe (material), pipe filled with an explosive material. The containment provided by the pipe means that simple Explosive material#Low explosives, low explosi ...

or pressure cooker bomb

A pressure cooker bomb is an improvised explosive device (IED) created by inserting explosive material into a pressure cooker and attaching a blasting cap into the cover of the cooker.

Pressure cooker bombs have been used in a number of attacks ...

. Early grenades

A grenade is an explosive weapon typically thrown by hand (also called hand grenade), but can also refer to a shell (explosive projectile) shot from the muzzle of a rifle (as a rifle grenade) or a grenade launcher. A modern hand grenade gene ...

were hollow cast-iron balls filled with gunpowder, and "shells" were similar devices designed to be shot from artillery in place of solid cannonballs ("shot"). Metonymically

Metonymy () is a figure of speech in which a concept is referred to by the name of something closely associated with that thing or concept.

Etymology

The words ''metonymy'' and ''metonym'' come from grc, μετωνυμία, 'a change of name ...

, the term "shell", from the casing, came to mean the entire munition

Ammunition (informally ammo) is the material fired, scattered, dropped, or detonated from any weapon or weapon system. Ammunition is both expendable weapons (e.g., bombs, missiles, grenades, land mines) and the component parts of other weapo ...

.

In a gunpowder-based shell, the casing was intrinsic to generating the explosion, and thus had to be strong and thick. Its fragments could do considerable damage, but each shell broke into only a few large pieces. Further developments led to shells which would fragment into smaller pieces. The advent of high explosives

An explosive (or explosive material) is a reactive substance that contains a great amount of potential energy that can produce an explosion if released suddenly, usually accompanied by the production of light, heat, sound, and pressure. An exp ...

such as TNT

Trinitrotoluene (), more commonly known as TNT, more specifically 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene, and by its preferred IUPAC name 2-methyl-1,3,5-trinitrobenzene, is a chemical compound with the formula C6H2(NO2)3CH3. TNT is occasionally used as a reagen ...

removed the need for a pressure-holding casing, so the casing of later shells only needs to contain the munition, and, if desired, to produce shrapnel. The term "shell," however, was sufficiently established that it remained as the term for such munitions.

Hollow shells filled with gunpowder needed a fuse that was either impact triggered (percussion

A percussion instrument is a musical instrument that is sounded by being struck or scraped by a beater including attached or enclosed beaters or rattles struck, scraped or rubbed by hand or struck against another similar instrument. Exc ...

) or time delayed.

Percussion fuses with a spherical projectile presented a challenge because there was no way of ensuring that the impact mechanism contacted the target. Therefore, ball shells needed a time fuse that was ignited before or during firing and burned until the shell reached its target.

Early shells

cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impuriti ...

used during the Song dynasty (960-1279) are described in the early Ming Dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last ort ...

Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of va ...

military manual ''Huolongjing

The ''Huolongjing'' (; Wade-Giles: ''Huo Lung Ching''; rendered in English as ''Fire Drake Manual'' or ''Fire Dragon Manual''), also known as ''Huoqitu'' (“Firearm Illustrations”), is a Chinese military treatise compiled and edited by Jiao ...

'', written in the mid 14th century.Needham, Joseph. (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7, Military Technology; the Gunpowder Epic. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd. Pages 24–25, 264. The ''History of Jin'' 《金史》 (compiled by 1345) states that in 1232, as the Mongol general Subutai

Subutai (Classical Mongolian: ''Sübügätäi'' or ''Sübü'ätäi''; Modern Mongolian: Сүбээдэй, ''Sübeedei''. ; ; c. 1175–1248) was a Mongol general and the primary military strategist of Genghis Khan and Ögedei Khan. He directed m ...

(1176–1248) descended on the Jin stronghold of Kaifeng

Kaifeng () is a prefecture-level city in east-central Henan province, China. It is one of the Eight Ancient Capitals of China, having been the capital eight times in history, and is best known for having been the Chinese capital during the Nort ...

, the defenders had a "thunder crash bomb

The thunder crash bomb (), also known as the heaven-shaking-thunder bomb, was one of the first bombs or hand grenades in the history of gunpowder warfare. It was developed in the 12th-13th century Song and Jin dynasties. Its shell was made of cast ...

" which "consisted of gunpowder put into an iron container ... then when the fuse was lit (and the projectile shot off) there was a great explosion the noise whereof was like thunder, audible for more than thirty miles, and the vegetation was scorched and blasted by the heat over an area of more than half a ''mou''. When hit, even iron armour

Iron armour was a type of naval armour used on warships and, to a limited degree, fortifications. The use of iron gave rise to the term ironclad as a reference to a ship 'clad' in iron. The earliest material available in sufficient quantities for ...

was quite pierced through."Needham, Joseph. (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7, Military Technology; the Gunpowder Epic. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd. Pages 24–25, 264. Archeological examples of these shells from the 13th century Mongol invasions of Japan have been recovered from a shipwreck.

Shells were used in combat by the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia, ...

at Jadra in 1376. Shells with fuses were used at the 1421 siege of St Boniface in Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, Còrsega; sc, Còssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

. These were two hollowed hemispheres of stone or bronze held together by an iron hoop.Hogg, p. 164. At least since the 16th century grenades made of ceramics or glass were in use in Central Europe. A hoard of several hundred ceramic grenades dated to the 17th century was discovered during building works in front of a bastion of the Bavarian city of Ingolstadt

Ingolstadt (, Austro-Bavarian: ) is an independent city on the Danube in Upper Bavaria with 139,553 inhabitants (as of June 30, 2022). Around half a million people live in the metropolitan area. Ingolstadt is the second largest city in Upper Bav ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

. Many of the grenades contained their original black-powder loads and igniters. Most probably the grenades were intentionally dumped in the moat of the bastion before the year 1723.

An early problem was that there was no means of precisely measuring the time to detonation reliable fuses did not yet exist, and the burning time of the powder fuse was subject to considerable trial and error. Early powder-burning fuses had to be loaded fuse down to be ignited by firing or a portfire or slow match

Slow match, also called match cord, is the slow-burning cord or twine fuse

Fuse or FUSE may refer to:

Devices

* Fuse (electrical), a device used in electrical systems to protect against excessive current

** Fuse (automotive), a class of fuses ...

put down the barrel to light the fuse. Other shells were wrapped in bitumen

Asphalt, also known as bitumen (, ), is a sticky, black, highly viscous liquid or semi-solid form of petroleum. It may be found in natural deposits or may be a refined product, and is classed as a pitch. Before the 20th century, the term a ...

cloth, which would ignite during the firing and in turn ignite a powder fuse. Nevertheless, shells came into regular use in the 16th century, for example, a 1543 English mortar shell was filled with "wildfire."

By the 18th century, it was known that the fuse toward the muzzle could be lit by the flash through the

By the 18th century, it was known that the fuse toward the muzzle could be lit by the flash through the windage

Windage is a term used in aerodynamics, firearms ballistics, and automobiles.

Usage

Aerodynamics

Windage is a force created on an object by friction when there is relative movement between air and the object. Windage loss is the reduction in e ...

between the shell and the barrel. At about this time, shells began to be employed for horizontal fire from howitzer

A howitzer () is a long- ranged weapon, falling between a cannon (also known as an artillery gun in the United States), which fires shells at flat trajectories, and a mortar, which fires at high angles of ascent and descent. Howitzers, like ot ...

s with a small propelling charge and, in 1779, experiments demonstrated that they could be used from guns with heavier charges.

The use of exploding shells from field artillery became relatively commonplace from early in the 19th century. Until the mid 19th century, shells remained as simple exploding spheres that used gunpowder, set off by a slow burning fuse. They were usually made of cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impuriti ...

, but bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals, such as phosphorus, or metalloids such ...

, lead

Lead is a chemical element with the symbol Pb (from the Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metal that is denser than most common materials. Lead is soft and malleable, and also has a relatively low melting point. When freshly cu ...

, brass

Brass is an alloy of copper (Cu) and zinc (Zn), in proportions which can be varied to achieve different mechanical, electrical, and chemical properties. It is a substitutional alloy: atoms of the two constituents may replace each other with ...

and even glass

Glass is a non-crystalline, often transparent, amorphous solid that has widespread practical, technological, and decorative use in, for example, window panes, tableware, and optics. Glass is most often formed by rapid cooling (quenching) of ...

shell casings were experimented with. The word ''bomb

A bomb is an explosive weapon that uses the Exothermic process, exothermic reaction of an explosive material to provide an extremely sudden and violent release of energy. Detonations inflict damage principally through ground- and atmosphere-t ...

'' encompassed them at the time, as heard in the lyrics of ''The Star-Spangled Banner

"The Star-Spangled Banner" is the national anthem of the United States. The lyrics come from the "Defence of Fort M'Henry", a poem written on September 14, 1814, by 35-year-old lawyer and amateur poet Francis Scott Key after witnessing the b ...

'' ("the bombs bursting in air"), although today that sense of ''bomb'' is obsolete. Typically, the thickness of the metal body was about a sixth of their diameter, and they were about two-thirds the weight of solid shot of the same caliber.

To ensure that shells were loaded with their fuses toward the muzzle, they were attached to wooden bottoms called ''sabots

Sabot may refer to:

* Sabot (firearms), disposable supportive device used in gunpowder ammunitions to fit/patch around a sub-caliber projectile

* Sabot (shoe), a type of wooden shoe

People

* Dick Sabot (1944–2005), American economist and busi ...

''. In 1819, a committee of British artillery officers recognized that they were essential stores and in 1830 Britain standardized sabot thickness as a half-inch. The sabot was also intended to reduce jamming during loading. Despite the use of exploding shells, the use of smoothbore cannons firing spherical projectiles of shot remained the dominant artillery method until the 1850s.

Modern shell

The mid–19th century saw a revolution in artillery, with the introduction of the first practical rifled breech loading weapons. The new methods resulted in the reshaping of the spherical shell into its modern recognizable cylindro-conoidal form. This shape greatly improved the in-flight stability of the projectile and meant that the primitive time fuzes could be replaced with the percussion fuze situated in the nose of the shell. The new shape also meant that further, armor-piercing designs could be used. During the 20th century, shells became increasingly streamlined. In World War I, ogives were typically two circular radius head (crh) – the curve was a segment of a circle having a radius of twice the shell caliber. After that war, ogive shapes became more complex and elongated. From the 1960s, higher quality steels were introduced by some countries for their HE shells, this enabled thinner shell walls with less weight of metal and hence a greater weight of explosive. Ogives were further elongated to improve their ballistic performance.Rifled breech loaders

Advances in metallurgy in the industrial era allowed for the construction of rifled breech-loading guns that could fire at a much greater

Advances in metallurgy in the industrial era allowed for the construction of rifled breech-loading guns that could fire at a much greater muzzle velocity

Muzzle velocity is the speed of a projectile (bullet, pellet, slug, ball/shots or shell) with respect to the muzzle at the moment it leaves the end of a gun's barrel (i.e. the muzzle). Firearm muzzle velocities range from approximately to i ...

. After the British artillery was shown up in the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the de ...

as having barely changed since the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

, the industrialist William Armstrong was awarded a contract by the government to design a new piece of artillery. Production started in 1855 at the Elswick Ordnance Company

The Elswick Ordnance Company (sometimes referred to as Elswick Ordnance Works, but usually as "EOC") was a British armaments manufacturing company of the late 19th and early 20th century

History

Originally created in 1859 to separate William A ...

and the Royal Arsenal

The Royal Arsenal, Woolwich is an establishment on the south bank of the River Thames in Woolwich in south-east London, England, that was used for the manufacture of armaments and ammunition, proofing, and explosives research for the Britis ...

at Woolwich

Woolwich () is a district in southeast London, England, within the Royal Borough of Greenwich.

The district's location on the River Thames led to its status as an important naval, military and industrial area; a role that was maintained throu ...

.

The piece was rifled

In firearms, rifling is machining helical grooves into the internal (bore) surface of a gun's barrel for the purpose of exerting torque and thus imparting a spin to a projectile around its longitudinal axis during shooting to stabilize the proj ...

, which allowed for a much more accurate and powerful action. Although rifling had been tried on small arms since the 15th century, the necessary machinery to accurately rifle artillery only became available in the mid-19th century. Martin von Wahrendorff

Martin von Wahrendorff (1789 – 1861) was a Swedish diplomat and inventor.

His father Anders von Wahrendorff was the owner of the gun foundry at Åker. Wahrendorff was Grand Master of Ceremonies at the Royal Court of Sweden from 1828 to ...

and Joseph Whitworth

Sir Joseph Whitworth, 1st Baronet (21 December 1803 – 22 January 1887) was an English engineer, entrepreneur, inventor and philanthropist. In 1841, he devised the British Standard Whitworth system, which created an accepted standard for scr ...

independently produced rifled cannons in the 1840s, but it was Armstrong's gun that was first to see widespread use during the Crimean War. The cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impuriti ...

shell of the Armstrong gun was similar in shape to a Minié ball

The Minié ball or Minie ball, is a type of hollow-based bullet designed by Claude-Étienne Minié, inventor of the French Minié rifle, for muzzle-loading rifled muskets. It was invented in 1847 and came to prominence in the Crimean War and ...

and had a thin lead coating which made it fractionally larger than the gun's bore and which engaged with the gun's rifling

In firearms, rifling is machining helical grooves into the internal (bore) surface of a gun's barrel for the purpose of exerting torque and thus imparting a spin to a projectile around its longitudinal axis during shooting to stabilize the pro ...

grooves to impart spin to the shell. This spin, together with the elimination of windage

Windage is a term used in aerodynamics, firearms ballistics, and automobiles.

Usage

Aerodynamics

Windage is a force created on an object by friction when there is relative movement between air and the object. Windage loss is the reduction in e ...

as a result of the tight fit, enabled the gun to achieve greater range and accuracy than existing smooth-bore muzzle-loaders with a smaller powder charge.

The gun was also a breech-loader. Although attempts at breech-loading mechanisms had been made since medieval times, the essential engineering problem was that the mechanism couldn't withstand the explosive charge. It was only with the advances in metallurgy

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the sc ...

and precision engineering

Precision engineering is a subdiscipline of electrical engineering, software engineering, electronics engineering, mechanical engineering, and optical engineering concerned with designing machines, fixtures, and other structures that have excepti ...

capabilities during the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

that Armstrong was able to construct a viable solution. Another innovative feature was what Armstrong called its "grip", which was essentially a squeeze bore

A squeeze bore, alternatively taper-bore, cone barrel or conical barrel, is a weapon where the internal gun barrel, barrel diameter progressively decreases towards the muzzle (firearms), muzzle resulting in a reduced final internal diameter. These ...

; the 6 inches of the bore at the muzzle end was of slightly smaller diameter, which centered the shell before it left the barrel and at the same time slightly swage

Swaging () is a forging process in which the dimensions of an item are altered using dies into which the item is forced. Swaging is usually a cold working process, but also may be hot worked.

The term swage may apply to the process (verb) or ...

d down its lead coating, reducing its diameter and slightly improving its ballistic qualities.

Rifled guns were also developed elsewhere – by Major Giovanni Cavalli and Baron Martin von Wahrendorff

Martin von Wahrendorff (1789 – 1861) was a Swedish diplomat and inventor.

His father Anders von Wahrendorff was the owner of the gun foundry at Åker. Wahrendorff was Grand Master of Ceremonies at the Royal Court of Sweden from 1828 to ...

in Sweden, Krupp

The Krupp family (see pronunciation), a prominent 400-year-old German dynasty from Essen, is notable for its production of steel, artillery, ammunition and other armaments. The family business, known as Friedrich Krupp AG (Friedrich Krup ...

in Germany and the Wiard gun

The Wiard rifle refers to several weapons invented by Norman Wiard, most commonly a semi-steel light artillery piece in six-pounder and twelve-pounder calibers. About 60 were manufactured between 1861 and 1862 during the American Civil War, at ...

in the United States. However, rifled barrels required some means of engaging the shell with the rifling. Lead coated shells were used with the Armstrong gun

An Armstrong gun was a uniquely designed type of Rifled breech-loader, rifled breech-loading field and heavy gun designed by William George Armstrong, 1st Baron Armstrong, Sir William Armstrong and manufactured in England beginning in 1855 by the ...

, but were not satisfactory so studded projectiles were adopted. However, these did not seal the gap between shell and barrel. Wads at the shell base were also tried without success.

In 1878, the British adopted a copper " gas-check" at the base of their studded projectiles and in 1879 tried a rotating gas check to replace the studs, leading to the 1881 automatic gas-check. This was soon followed by the Vavaseur copper driving band Russian 122 mm shrapnel shell, which has been fired, showing rifling marks on the copper driving band around its base and the steel bourrelet nearer the front

A driving band or rotating band is a band of soft metal near the base of an artillery ...

as part of the projectile. The driving band rotated the projectile, centered it in the bore and prevented gas escaping forwards. A driving band has to be soft but tough enough to prevent stripping by rotational and engraving stresses. Copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkis ...

is generally most suitable but cupronickel

Cupronickel or copper-nickel (CuNi) is an alloy of copper that contains nickel and strengthening elements, such as iron and manganese. The copper content typically varies from 60 to 90 percent. (Monel is a nickel-copper alloy that contains a minimu ...

or gilding metal

Gilding metal is a form of brass (an alloy of copper and zinc) with a much higher copper content than zinc content. Exact figures range from 95% copper and 5% zinc to “8 parts copper to 1 of zinc” (11% zinc) in British Army Dress Regulations.

...

were also used.Hogg, pp. 165–166.

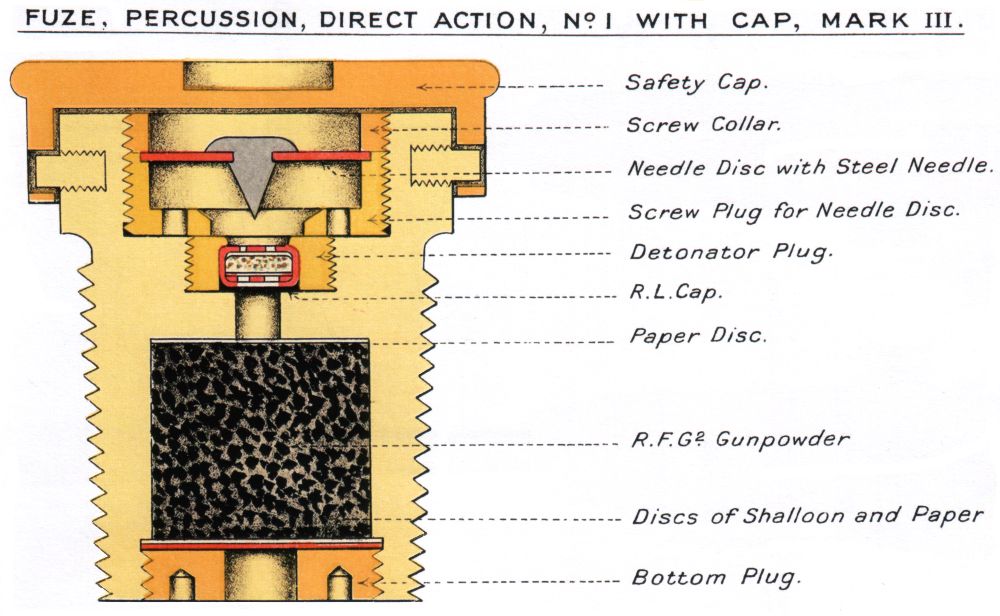

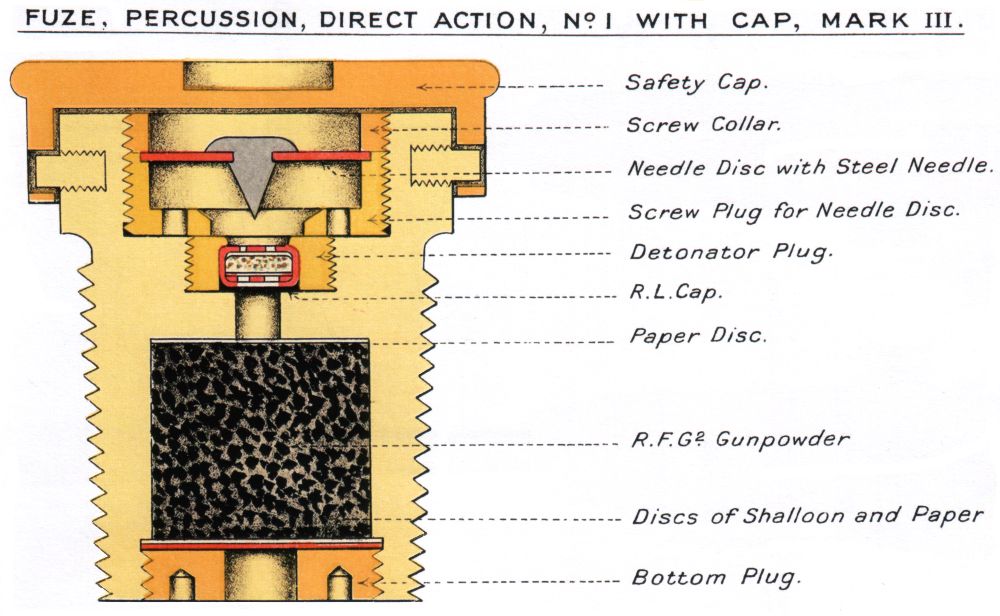

Percussion fuze

Although an early percussion fuze appeared in 1650 that used a flint to create sparks to ignite the powder, the shell had to fall in a particular way for this to work and this did not work with spherical projectiles. An additional problem was finding a suitably stable "percussion powder". Progress was not possible until the discovery of

Although an early percussion fuze appeared in 1650 that used a flint to create sparks to ignite the powder, the shell had to fall in a particular way for this to work and this did not work with spherical projectiles. An additional problem was finding a suitably stable "percussion powder". Progress was not possible until the discovery of mercury fulminate

Mercury(II) fulminate, or Hg(CNO)2, is a primary explosive. It is highly sensitive to friction, heat and shock and is mainly used as a trigger for other explosives in percussion caps and detonators. Mercury(II) cyanate, though its chemical formula ...

in 1800, leading to priming mixtures for small arms patented by the Rev Alexander Forsyth

Alexander John Forsyth (28 December 1768 – 11 June 1843) was a Scottish Church of Scotland minister who first successfully used fulminating (or 'detonating') chemicals to prime gunpowder in fire-arms thereby creating what became known as per ...

, and the copper percussion cap in 1818.

The percussion fuze was adopted by Britain in 1842. Many designs were jointly examined by the army and navy, but were unsatisfactory, probably because of the safety and arming features. However, in 1846 the design by Quartermaster Freeburn of the Royal Artillery was adopted by the army. It was a wooden fuze about 6 inches long and used shear wire to hold blocks between the fuze magazine and a burning match. The match was ignited by propellant flash and the shear wire broke on impact. A British naval percussion fuze made of metal did not appear until 1861.

Types of fuzes

* Percussion fuzes ** Direct action fuzes ** Graze fuzes ** Delay fuzes ** Base fuzes * Airburst fuzes ** Time fuzes ** Proximity fuzes ** Distance measuring fuzes ** Electronic time fuzesSmokeless powders

Gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). ...

was used as the only form of explosive up until the end of the 19th century. Guns using black powder ammunition would have their view obscured by a huge cloud of smoke and concealed shooters were given away by a cloud of smoke over the firing position. Guncotton

Nitrocellulose (also known as cellulose nitrate, flash paper, flash cotton, guncotton, pyroxylin and flash string, depending on form) is a highly flammable compound formed by nitrating cellulose through exposure to a mixture of nitric acid and ...

, a nitrocellulose-based material, was discovered by Swiss

Swiss may refer to:

* the adjectival form of Switzerland

* Swiss people

Places

* Swiss, Missouri

* Swiss, North Carolina

*Swiss, West Virginia

* Swiss, Wisconsin

Other uses

*Swiss-system tournament, in various games and sports

*Swiss Internation ...

chemist Christian Friedrich Schönbein

Christian Friedrich Schönbein H FRSE(18 October 1799 – 29 August 1868) was a German-Swiss chemist who is best known for inventing the fuel cell (1838) at the same time as William Robert Grove and his discoveries of guncotton and ozone.

Lif ...

in 1846. He promoted its use as a blasting explosiveDavis, William C., Jr. ''Handloading''. National Rifle Association of America (1981). p. 28. and sold manufacturing rights to the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central-Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, ...

. Guncotton was more powerful than gunpowder, but at the same time was somewhat more unstable. John Taylor obtained an English patent for guncotton; and John Hall & Sons began manufacture in Faversham. British interest waned after an explosion destroyed the Faversham factory in 1847. Austrian Baron Wilhelm Lenk von Wolfsberg

Nikolaus Wilhelm Freiherr Lenk von Wolfsberg (born March 17, 1809, České Budějovice, Budweis, Austrian Empire, Austria; died October 18, 1894, Opava, Troppau, Austrian Empire, Austria) was an Austrian officer (Feldzeugmeister), owner of the Corp ...

built two guncotton plants producing artillery propellant, but it was dangerous under field conditions, and guns that could fire thousands of rounds using gunpowder would reach their service life after only a few hundred shots with the more powerful guncotton.

Small arms could not withstand the pressures generated by guncotton. After one of the Austrian factories blew up in 1862, Thomas Prentice & Company began manufacturing guncotton in Stowmarket

Stowmarket ( ) is a market town in Suffolk, England,OS Explorer map 211: Bury St.Edmunds and Stowmarket

Scale: 1:25 000. Publisher:Ordnance Survey – Southampton A2 edition. Publishing Date:2008. on the busy A14 road (Great Britain), A14 trunk ...

in 1863; and British War Office

The War Office was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, when its functions were transferred to the new Ministry of Defence (MoD). This article contains text from ...

chemist Sir Frederick Abel

Sir Frederick Augustus Abel, 1st Baronet (17 July 18276 September 1902) was an English chemist who was recognised as the leading British authority on explosives. He is best known for the invention of cordite as a replacement for gunpowder in f ...

began thorough research at Waltham Abbey Royal Gunpowder Mills

The Royal Gunpowder Mills are a former industrial site in Waltham Abbey, England.

It was one of three Royal Gunpowder Mills in the United Kingdom (the others being at Ballincollig and Faversham). Waltham Abbey is the only site to have survive ...

leading to a manufacturing process that eliminated the impurities in nitrocellulose making it safer to produce and a stable product safer to handle. Abel patented this process in 1865, when the second Austrian guncotton factory exploded. After the Stowmarket factory exploded in 1871, Waltham Abbey began production of guncotton for torpedo and mine warheads.Sharpe, Philip B. ''Complete Guide to Handloading''. 3rd edition (1953). Funk & Wagnalls. pp. 141–144.

In 1884,

In 1884, Paul Vieille

Paul may refer to:

*Paul (given name), a given name (includes a list of people with that name)

* Paul (surname), a list of people

People

Christianity

*Paul the Apostle (AD c.5–c.64/65), also known as Saul of Tarsus or Saint Paul, early Chri ...

invented a smokeless powder called Poudre B (short for ''poudre blanche''—white powder, as distinguished from black powder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). Th ...

)Davis, Tenney L. ''The Chemistry of Powder & Explosives'' (1943), pages 289–292. made from 68.2% insoluble nitrocellulose

Nitrocellulose (also known as cellulose nitrate, flash paper, flash cotton, guncotton, pyroxylin and flash string, depending on form) is a highly flammable compound formed by nitrating cellulose through exposure to a mixture of nitric acid and ...

, 29.8% soluble nitrocellusose gelatinized with ether

In organic chemistry, ethers are a class of compounds that contain an ether group—an oxygen atom connected to two alkyl or aryl groups. They have the general formula , where R and R′ represent the alkyl or aryl groups. Ethers can again be c ...

and 2% paraffin. This was adopted for the Lebel rifle.Hogg, Oliver F. G. ''Artillery: Its Origin, Heyday and Decline'' (1969), p. 139. Vieille's powder revolutionized the effectiveness of small guns, because it gave off almost no smoke and was three times more powerful than black powder. Higher muzzle velocity

Muzzle velocity is the speed of a projectile (bullet, pellet, slug, ball/shots or shell) with respect to the muzzle at the moment it leaves the end of a gun's barrel (i.e. the muzzle). Firearm muzzle velocities range from approximately to i ...

meant a flatter trajectory

A trajectory or flight path is the path that an object with mass in motion follows through space as a function of time. In classical mechanics, a trajectory is defined by Hamiltonian mechanics via canonical coordinates; hence, a complete traj ...

and less wind drift and bullet drop, making 1000 meter shots practicable. Other European countries swiftly followed and started using their own versions of Poudre B, the first being Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

and Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

which introduced new weapons in 1888. Subsequently, Poudre B was modified several times with various compounds being added and removed. Krupp

The Krupp family (see pronunciation), a prominent 400-year-old German dynasty from Essen, is notable for its production of steel, artillery, ammunition and other armaments. The family business, known as Friedrich Krupp AG (Friedrich Krup ...

began adding diphenylamine

Diphenylamine is an organic compound with the formula (C6H5)2NH. The compound is a derivative of aniline, consisting of an amine bound to two phenyl groups. The compound is a colorless solid, but commercial samples are often yellow due to oxidized ...

as a stabilizer in 1888.

Britain conducted trials on all the various types of propellant brought to their attention, but were dissatisfied with them all and sought something superior to all existing types. In 1889, Sir Frederick Abel

Sir Frederick Augustus Abel, 1st Baronet (17 July 18276 September 1902) was an English chemist who was recognised as the leading British authority on explosives. He is best known for the invention of cordite as a replacement for gunpowder in f ...

, James Dewar

Sir James Dewar (20 September 1842 – 27 March 1923) was a British chemist and physicist. He is best known for his invention of the vacuum flask, which he used in conjunction with research into the liquefaction of gases. He also studied ato ...

and Dr. W. Kellner patented (No. 5614 and No. 11,664 in the names of Abel and Dewar) a new formulation that was manufactured at the Royal Gunpowder Factory at Waltham Abbey. It entered British service in 1891 as Cordite

Cordite is a family of smokeless propellants developed and produced in the United Kingdom since 1889 to replace black powder as a military propellant. Like modern gunpowder, cordite is classified as a low explosive because of its slow burni ...

Mark 1. Its main composition was 58% nitro-glycerine, 37% guncotton and 3% mineral jelly. A modified version, Cordite MD, entered service in 1901, this increased guncotton to 65% and reduced nitro-glycerine to 30%, this change reduced the combustion temperature and hence erosion and barrel wear. Cordite could be made to burn more slowly which reduced maximum pressure in the chamber (hence lighter breeches, etc.), but longer high pressure – significant improvements over gunpowder. Cordite could be made in any desired shape or size.Hogg, Oliver F. G. ''Artillery: Its Origin, Heyday and Decline'' (1969), p. 141. The creation of cordite led to a lengthy court battle between Nobel, Maxim, and another inventor over alleged British patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an enabling disclosure of the invention."A p ...

infringement.

Other shell types

A variety of fillings have been used in shells throughout history. An incendiary shell was invented by Valturio in 1460. The

A variety of fillings have been used in shells throughout history. An incendiary shell was invented by Valturio in 1460. The carcass shell

Carcass or Carcase (both pronounced ) may refer to:

*Dressed carcass, the body of a livestock animal ready for butchery, after removal of skin, visceral organs, head, feet etc.

*Carrion, the decaying dead body of an animal or human being

*The str ...

was first used by the French under Louis XIV

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Versa ...

in 1672. Initially in the shape of an oblong

An oblong is a non-square rectangle.

Oblong may also refer to:

Places

* Oblong, Illinois, a village in the United States

* Oblong Township, Crawford County, Illinois, United States

* A strip of land on the New York-Connecticut border in the Unit ...

in an iron frame (with poor ballistic properties) it evolved into a spherical shell. Their use continued well into the 19th century.

A modern version of the incendiary shell was developed in 1857 by the British and was known as ''Martin's shell'' after its inventor. The shell was filled with molten iron and was intended to break up on impact with an enemy ship, splashing molten iron on the target. It was used by the Royal Navy between 1860 and 1869, replacing heated shot

Heated shot or hot shot is round shot that is heated before firing from muzzle-loading cannons, for the purpose of setting fire to enemy warships, buildings, or equipment. The use of heated shot dates back centuries; it was a powerful weapon agains ...

as an anti-ship, incendiary projectile.

Two patterns of incendiary shell were used by the British in World War I, one designed for use against Zeppelins.

Similar to incendiary shells were star shells, designed for illumination rather than arson. Sometimes called lightballs they were in use from the 17th century onwards. The British adopted parachute lightballs in 1866 for 10-, 8- and 5-inch calibers. The 10-inch wasn't officially declared obsolete until 1920.Hogg, pp. 174–176.

Smoke balls also date back to the 17th century, British ones contained a mix of saltpetre, coal, pitch, tar, resin, sawdust, crude antimony and sulphur. They produced a "noisome smoke in abundance that is impossible to bear". In 19th-century British service, they were made of concentric paper with a thickness about 1/15th of the total diameter and filled with powder, saltpeter, pitch, coal and tallow. They were used to 'suffocate or expel the enemy in casemates, mines or between decks; for concealing operations; and as signals.

During the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, shrapnel shell

Shrapnel shells were anti-personnel artillery munitions which carried many individual bullets close to a target area and then ejected them to allow them to continue along the shell's trajectory and strike targets individually. They relied almo ...

s and explosive shells inflicted terrible casualties on infantry, accounting for nearly 70% of all war casualties and leading to the adoption of steel combat helmet

A combat helmet or battle helmet is a type of helmet. It is a piece of personal armor designed specifically to protect the head during combat. Modern combat helmets are mainly designed to protect from shrapnel and fragments, offer some protec ...

s on both sides. Frequent problems with shells led to many military disasters with dud shells, most notably during the 1916 Battle of the Somme

The Battle of the Somme ( French: Bataille de la Somme), also known as the Somme offensive, was a battle of the First World War fought by the armies of the British Empire and French Third Republic against the German Empire. It took place bet ...

. Shells filled with poison gas

Gas is one of the four fundamental states of matter (the others being solid, liquid, and plasma).

A pure gas may be made up of individual atoms (e.g. a noble gas like neon), elemental molecules made from one type of atom (e.g. oxygen), or ...

were used from 1917 onwards.

Propulsion

Artillery shells are differentiated by how the shell is loaded and propelled, and the type of breech mechanism.Fixed ammunition

Fixed ammunition has three main components: thefuze

In military munitions, a fuze (sometimes fuse) is the part of the device that initiates function. In some applications, such as torpedoes, a fuze may be identified by function as the exploder. The relative complexity of even the earliest fuze d ...

d projectile, the casing to hold the propellants and primer

Primer may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''Primer'' (film), a 2004 feature film written and directed by Shane Carruth

* ''Primer'' (video), a documentary about the funk band Living Colour

Literature

* Primer (textbook), a t ...

, and the single propellant charge. Everything is included in a ready-to-use package and in British ordnance terms is called fixed quick firing. Often guns which use fixed ammunition use sliding-block or sliding-wedge breeches and the case provides obturation

In the field of firearms and airguns, obturation denotes necessary barrel blockage or fit by a deformed soft projectile (obturation in general is closing up an opening). A bullet or pellet, made of soft material and often with a concave base, wi ...

which seals the breech

Breech may refer to:

* Breech (firearms), the opening at the rear of a gun barrel where the cartridge is inserted in a breech-loading weapon

* breech, the lower part of a pulley block

* breech, the penetration of a boiler where exhaust gases leav ...

of the gun and prevents propellant gasses from escaping. Sliding block breeches can be horizontal or vertical. Advantages of fixed ammunition are simplicity, safety, moisture resistance and speed of loading. Disadvantages are eventually a fixed round becomes too long or too heavy to load by a gun crew. Another issue is the inability to vary propellant charges to achieve different velocities and ranges. Lastly, there is the issue of resource usage since a fixed round uses a case, which can be an issue in a prolonged war if there are metal shortages.

Separate loading cased charge

Separate loading cased charge ammunition has three main components: the fuzed projectile, the casing to hold the propellants and primer, and the bagged propellant charges. The components are usually separated into two or more parts. In British ordnance terms, this type of ammunition is called separate quick firing. Often guns which use separate loading cased charge ammunition use sliding-block or sliding-wedge breeches and duringWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

Germany predominantly used fixed or separate loading cased charges and sliding block breeches even for their largest guns. A variant of separate loading cased charge ammunition is semi-fixed ammunition. With semi-fixed ammunition the round comes as a complete package but the projectile and its case can be separated. The case holds a set number of bagged charges and the gun crew can add or subtract propellant to change range and velocity. The round is then reassembled, loaded, and fired. Advantages include easier handling for larger caliber rounds, while range and velocity can easily be varied by increasing or decreasing the number of propellant charges. Disadvantages include more complexity, slower loading, less safety, less moisture resistance, and the metal cases can still be a material resource issue.

Separate loading bagged charge

Separate loading bagged charge ammunition there are three main components: the fuzed projectile, the bagged charges and the primer. Like separate loading cased charge ammunition, the number of propellant charges can be varied. However, this style of ammunition does not use a cartridge case and it achieves obturation through a screw breech instead of a sliding block. Sometimes when reading about artillery the term separate loading ammunition will be used without clarification of whether a cartridge case is used or not, in which case refer to the type of breech used. Heavy artillery pieces andnaval artillery

Naval artillery is artillery mounted on a warship, originally used only for naval warfare and then subsequently used for naval gunfire support, shore bombardment and anti-aircraft roles. The term generally refers to tube-launched projectile-firi ...

tend to use bagged charges and projectiles because the weight and size of the projectiles and propelling charges can be more than a gun crew can manage. Advantages include easier handling for large rounds, decreased metal usage, while range and velocity can be varied by using more or fewer propellant charges. Disadvantages include more complexity, slower loading, less safety and less moisture resistance.

Range-enhancing technologies

Extended-range shells are sometimes used. These special shell designs may be

Extended-range shells are sometimes used. These special shell designs may be rocket-assisted projectile

A rocket-assisted projectile (RAP) is a cannon, howitzer, Mortar (weapon), mortar, or recoilless rifle round incorporating a rocket motor for independent propulsion. This gives the projectile greater speed and range than a non-assisted Ballistics, ...

s (RAP) or base bleed

Base bleed is a system used on some artillery shells to increase range, typically by about 20–35%. It expels gas into the low pressure area behind the shell to reduce base drag (it does not produce thrust).

Since base bleed extends the ran ...

(BB) to increase range. The first has a small rocket motor built into its base to provide additional thrust. The second has a pyrotechnic device in its base that bleeds gas to fill the partial vacuum created behind the shell and hence reduce base-drag. These shell designs usually have reduced high-explosive filling to remain within the permitted mass for the projectile, and hence less lethality.

Sizes

The

The caliber

In guns, particularly firearms, caliber (or calibre; sometimes abbreviated as "cal") is the specified nominal internal diameter of the gun barrel Gauge (firearms) , bore – regardless of how or where the bore is measured and whether the f ...

of a shell is its diameter

In geometry, a diameter of a circle is any straight line segment that passes through the center of the circle and whose endpoints lie on the circle. It can also be defined as the longest chord of the circle. Both definitions are also valid for ...

. Depending on the historical period and national preferences, this may be specified in millimeter

330px, Different lengths as in respect to the electromagnetic spectrum, measured by the metre and its derived scales. The microwave is between 1 meter to 1 millimeter.

The millimetre (American and British English spelling differences#-re, -er, ...

s, centimeter

330px, Different lengths as in respect to the Electromagnetic spectrum, measured by the Metre and its deriveds scales. The Microwave are in-between 1 meter to 1 millimeter.

A centimetre (international spelling) or centimeter (American spellin ...

s, or inch

Measuring tape with inches

The inch (symbol: in or ″) is a unit of length in the British imperial and the United States customary systems of measurement. It is equal to yard or of a foot. Derived from the Roman uncia ("twelfth") ...

es. The length of gun barrels for large cartridges and shells (naval) is frequently quoted in terms of the ratio of the barrel length to the bore size, also called caliber

In guns, particularly firearms, caliber (or calibre; sometimes abbreviated as "cal") is the specified nominal internal diameter of the gun barrel Gauge (firearms) , bore – regardless of how or where the bore is measured and whether the f ...

. For example, the 16"/50 caliber Mark 7 gun

The 16"/50 caliber Mark 7 – United States Naval Gun is the main armament of the ''Iowa''-class battleships and was the planned main armament of the cancelled .

Description

Due to a lack of communication during design, the Bureau of Ordnance ...

is 50 calibers long, that is, 16"×50=800"=66.7 feet long. Some guns, mainly British, were specified by the weight of their shells (see below).

Explosive rounds as small as 12.7 x 82 mm and 13 x 64 mm have been used on aircraft and armored vehicles, but their small explosive yield have led some nations to limit their explosive rounds to 20mm

20 mm caliber is a specific size of popular autocannon ammunition. It is typically used to distinguish smaller-caliber weapons, commonly called "guns", from larger-caliber "cannons" (e.g. machine gun vs. autocannon). All 20 mm cartridges ha ...

(.78 in) or larger. International Law precludes the use of explosive ammunition for use against individual persons, but not against vehicles and aircraft. The largest shells ever fired during war were those from the German super-railway gun

A railway gun, also called a railroad gun, is a large artillery piece, often surplus naval artillery, mounted on, transported by, and fired from a specially designed railroad car, railway wagon. Many countries have built railway guns, but the ...

s, Gustav and Dora, which were 800 mm (31.5 in) in caliber. Very large shells have been replaced by rocket

A rocket (from it, rocchetto, , bobbin/spool) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using the surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entirely fr ...

s, missiles

In military terminology, a missile is a guided airborne ranged weapon capable of self-propelled flight usually by a jet engine or rocket motor. Missiles are thus also called guided missiles or guided rockets (when a previously unguided rocket i ...

, and bomb

A bomb is an explosive weapon that uses the Exothermic process, exothermic reaction of an explosive material to provide an extremely sudden and violent release of energy. Detonations inflict damage principally through ground- and atmosphere-t ...

s. Today the largest shells in common use are 155 mm

155 mm (6.1 in) is a common, NATO-standard, artillery caliber. It is defined in AOP-29 part 1 with reference to STANAG 4425. It is commonly used in field guns, howitzers, and gun-howitzers.

Land warfare

The caliber originated in France after ...

(6.1 in).

Gun calibers have standardized around a few common sizes, especially in the larger range, mainly due to the uniformity required for efficient military logistics. Artillery shells of 105 and 155 mm for artillery with 105 and 120 mm for

Gun calibers have standardized around a few common sizes, especially in the larger range, mainly due to the uniformity required for efficient military logistics. Artillery shells of 105 and 155 mm for artillery with 105 and 120 mm for tank gun

A tank gun is the main armament of a tank. Modern tank guns are high-velocity, large-caliber artilleries capable of firing kinetic energy penetrators, high-explosive anti-tank, and cannon-launched guided projectiles. Anti-aircraft guns can also ...

s are common in NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

allied countries. Artillery shells of 122, 130, and 152 mm with tank gun ammunition of 100, 115, and 125 mm calibers remain in common usage among the regions of Eastern Europe, Western Asia, Northern Africa, and Eastern Asia. Most common calibers have been in use for many decades, since it is logistically complex to change the caliber of all guns and ammunition stores.

The weight of shells increases by and large with caliber. A typical 155 mm (6.1 in) shell weighs about 50 kg (110 lbs), a common 203 mm (8 in) shell about 100 kg (220 lbs), a concrete demolition 203 mm (8 in) shell 146 kg (322 lbs), a 280 mm (11 in) battleship shell about 300 kg (661 lbs), and a 460 mm (18 in) battleship shell over 1,500 kg (3,307 lbs). The Schwerer Gustav

Schwerer Gustav (English: ''Heavy Gustav'') was a German railway gun. It was developed in the late 1930s by Krupp in Rügenwalde as siege artillery for the explicit purpose of destroying the main forts of the French Maginot Line, the strongest ...

large-calibre gun fired shells that weighed between 4,800 kg (10,582 lbs) and 7,100 kg (15,653 lbs).

During the 19th century, the British adopted a particular form of designating artillery. Field guns were designated by nominal standard projectile weight, while howitzers were designated by barrel caliber. British guns and their ammunition were designated in pounds, e.g., as "two-pounder" shortened to "2-pr" or "2-pdr". Usually, this referred to the actual weight of the standard projectile (shot, shrapnel, or high explosive), but, confusingly, this was not always the case.

Some were named after the weights of obsolete projectile types of the same caliber, or even obsolete types that were considered to have been functionally equivalent. Also, projectiles fired from the same gun, but of non-standard weight, took their name from the gun. Thus, conversion from "pounds" to an actual barrel diameter requires consulting a historical reference. A mixture of designations were in use for land artillery from the First World War (such as the BL 60-pounder gun

The Ordnance BL 60-pounder was a British 5 inch (127 mm) heavy field gun designed in 1903–05 to provide a new capability that had been partially met by the interim QF 4.7 inch Gun Mk I - IV, QF 4.7 inch Gun. It was designed for both ...

, RML 2.5 inch Mountain Gun

The Ordnance RML 2.5-inch mountain gun was a British rifled muzzle-loading mountain gun of the late 19th century designed to be broken down into four loads for carrying by man or mule. It was primarily used by the Indian Army.

History

It was ...

, 4 inch gun, 4.5 inch howitzer) through to the end of World War II (5.5 inch medium gun, 25-pounder gun-howitzer, 17-pounder tank gun), but the majority of naval guns were by caliber. After the end of World War II, field guns were designated by caliber.

Types

There are many different types of shells. The principal ones include:

There are many different types of shells. The principal ones include:

Armor-piercing shells

With the introduction of the firstironclad

An ironclad is a steam engine, steam-propelled warship protected by Wrought iron, iron or steel iron armor, armor plates, constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships ...

s in the 1850s and 1860s, it became clear that shells had to be designed to effectively pierce the ship armor. A series of British tests in 1863 demonstrated that the way forward lay with high-velocity lighter shells. The first pointed armor-piercing shell was introduced by Major Palliser in 1863. Approved in 1867, Palliser shot and shell

upPalliser shot, Mark I, for 9-inch Rifled Muzzle Loading (RML) gun

Palliser shot is an early British armour-piercing artillery projectile, intended to pierce the armour protection of warships being developed in the second half of the 19th centur ...

was an improvement over the ordinary elongated shot of the time. Palliser shot was made of cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impuriti ...

, the head being chilled in casting to harden it, using composite molds with a metal, water cooled portion for the head.

Britain also deployed Palliser shells in the 1870s–1880s. In the shell, the cavity was slightly larger than in the shot and was filled with 1.5% gunpowder instead of being empty, to provide a small explosive effect after penetrating armor plating. The shell was correspondingly slightly longer than the shot to compensate for the lighter cavity. The powder filling was ignited by the shock of impact and hence did not require a fuze."Treatise on Ammunition

''Treatise on Ammunition'', from 1926 retitled ''Text Book of Ammunition'', is a series of manuals detailing all British Empire military and naval service ammunition and associated equipment in use at the date of publication. It was published by ...