2001 (film) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''2001: A Space Odyssey'' is a 1968

Kubrick told Clarke he wanted to make a film about "Man's relationship to the universe", and was, in Clarke's words, "determined to create a work of art which would arouse the emotions of wonder, awe ... even, if appropriate, terror". Clarke offered Kubrick six of his short stories, and by May 1964, Kubrick had chosen " The Sentinel" as the source material for the film. In search of more material to expand the film's plot, the two spent the rest of 1964 reading books on science and anthropology, screening science fiction films, and brainstorming ideas. They created the plot for ''2001'' by integrating several different short story plots written by Clarke, along with new plot segments requested by Kubrick for the film development, and then combined them all into a single script for ''2001''. Clarke said that his 1953 story "

Kubrick told Clarke he wanted to make a film about "Man's relationship to the universe", and was, in Clarke's words, "determined to create a work of art which would arouse the emotions of wonder, awe ... even, if appropriate, terror". Clarke offered Kubrick six of his short stories, and by May 1964, Kubrick had chosen " The Sentinel" as the source material for the film. In search of more material to expand the film's plot, the two spent the rest of 1964 reading books on science and anthropology, screening science fiction films, and brainstorming ideas. They created the plot for ''2001'' by integrating several different short story plots written by Clarke, along with new plot segments requested by Kubrick for the film development, and then combined them all into a single script for ''2001''. Clarke said that his 1953 story "

Some of the critics' cataclysmic interpretations were informed by Kubrick's prior direction of the Cold War film ''Dr. Strangelove'', immediately before ''2001'', which resulted in dark speculation about the nuclear weapons orbiting the Earth in ''2001''. These interpretations were challenged by Clarke, who said: "Many readers have interpreted the last paragraph of the book to mean that he (the foetus) destroyed Earth, perhaps for the purpose of creating a new Heaven. This idea never occurred to me; it seems clear that he triggered the orbiting nuclear bombs harmlessly...". In response to Jeremy Bernstein's dark interpretation of the film's ending, Kubrick said: "The book does not end with the destruction of the Earth."

Regarding the film as a whole, Kubrick encouraged people to make their own interpretations and refused to offer an explanation of "what really happened". In a 1968 interview with Playboy, ''Playboy'' magazine, he said:

In a subsequent discussion of the film with Joseph Gelmis, Kubrick said his main aim was to avoid "intellectual verbalization" and reach "the viewer's subconscious." But he said he did not strive for ambiguity—it was simply an inevitable outcome of making the film nonverbal. Still, he acknowledged this ambiguity was an invaluable asset to the film. He was willing then to give a fairly straightforward explanation of the plot on what he called the "simplest level," but unwilling to discuss the film's metaphysical interpretation, which he felt should be left up to viewers.

Some of the critics' cataclysmic interpretations were informed by Kubrick's prior direction of the Cold War film ''Dr. Strangelove'', immediately before ''2001'', which resulted in dark speculation about the nuclear weapons orbiting the Earth in ''2001''. These interpretations were challenged by Clarke, who said: "Many readers have interpreted the last paragraph of the book to mean that he (the foetus) destroyed Earth, perhaps for the purpose of creating a new Heaven. This idea never occurred to me; it seems clear that he triggered the orbiting nuclear bombs harmlessly...". In response to Jeremy Bernstein's dark interpretation of the film's ending, Kubrick said: "The book does not end with the destruction of the Earth."

Regarding the film as a whole, Kubrick encouraged people to make their own interpretations and refused to offer an explanation of "what really happened". In a 1968 interview with Playboy, ''Playboy'' magazine, he said:

In a subsequent discussion of the film with Joseph Gelmis, Kubrick said his main aim was to avoid "intellectual verbalization" and reach "the viewer's subconscious." But he said he did not strive for ambiguity—it was simply an inevitable outcome of making the film nonverbal. Still, he acknowledged this ambiguity was an invaluable asset to the film. He was willing then to give a fairly straightforward explanation of the plot on what he called the "simplest level," but unwilling to discuss the film's metaphysical interpretation, which he felt should be left up to viewers.

The reasons for HAL's malfunction and subsequent malignant behaviour have elicited much discussion. He has been compared to Frankenstein's monster. In Clarke's novel, HAL malfunctions because of being ordered to lie to the crew of ''Discovery'' and withhold confidential information from them, namely the confidentially programmed mission priority over expendable human life, despite being constructed for "the accurate processing of information without distortion or concealment". This would not be addressed on film until the 1984 follow-up, ''2010: The Year We Make Contact''. Film critic Roger Ebert wrote that HAL, as the supposedly perfect computer, is actually the most human of the characters. In an interview with Joseph Gelmis in 1969, Kubrick said that HAL "had an acute emotional crisis because he could not accept evidence of his own fallibility".

The reasons for HAL's malfunction and subsequent malignant behaviour have elicited much discussion. He has been compared to Frankenstein's monster. In Clarke's novel, HAL malfunctions because of being ordered to lie to the crew of ''Discovery'' and withhold confidential information from them, namely the confidentially programmed mission priority over expendable human life, despite being constructed for "the accurate processing of information without distortion or concealment". This would not be addressed on film until the 1984 follow-up, ''2010: The Year We Make Contact''. Film critic Roger Ebert wrote that HAL, as the supposedly perfect computer, is actually the most human of the characters. In an interview with Joseph Gelmis in 1969, Kubrick said that HAL "had an acute emotional crisis because he could not accept evidence of his own fallibility".

* ''2001: A Space Odyssey'' essay by Daniel Eagan in America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry, A&C Black, 2010 , pages 635–63

America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry

* * * *

''2001: A Space Odyssey'' Internet Resource Archive

Kubrick ''2001: The Space Odyssey'' Explained

Roger Ebert's Essay on ''2001''

many observations on the meaning of ''2001''

The Kubrick Site

including many works on ''2001'' {{DEFAULTSORT:2001: A Space Odyssey 1960s science fiction films 1968 films Adaptations of works by Arthur C. Clarke American science fiction adventure films Articles containing video clips British science fiction adventure films Cryonics in fiction American epic films Films about evolution 1960s English-language films Films about artificial intelligence Films about astronauts Films about technological impact Films based on science fiction short stories Films adapted into comics Films based on short fiction Films directed by Stanley Kubrick Films produced by Stanley Kubrick Films with screenplays by Stanley Kubrick Films set in prehistory Films set in 1999 Films set in 2001 Films set in the future Films set on spacecraft Films shot in Hertfordshire Films shot in the Outer Hebrides Films shot in Spain Films shot in Surrey Films shot in Utah Films that won the Best Visual Effects Academy Award Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation winning works Jupiter in film Metaphysical fiction films Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films Moon in film Prehistoric people in popular culture Films shot at Shepperton Studios Hard science fiction films American space adventure films IMAX films Space Odyssey United States National Film Registry films Films set in pre-colonial sub-Saharan Africa Films shot at MGM-British Studios 1960s American films 1960s British films

epic

Epic commonly refers to:

* Epic poetry, a long narrative poem celebrating heroic deeds and events significant to a culture or nation

* Epic film, a genre of film with heroic elements

Epic or EPIC may also refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and medi ...

science fiction film

Science fiction (or sci-fi) is a film genre that uses speculative, fictional science-based depictions of phenomena that are not fully accepted by mainstream science, such as extraterrestrial lifeforms, spacecraft, robots, cyborgs, interstellar ...

produced and directed by Stanley Kubrick

Stanley Kubrick (; July 26, 1928 – March 7, 1999) was an American film director, producer, screenwriter, and photographer. Widely considered one of the greatest filmmakers of all time, his films, almost all of which are adaptations of nove ...

. The screenplay

''ScreenPlay'' is a television drama anthology series broadcast on BBC2 between 9 July 1986 and 27 October 1993.

Background

After single-play anthology series went off the air, the BBC introduced several showcases for made-for-television, fe ...

was written by Kubrick and science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke

Sir Arthur Charles Clarke (16 December 191719 March 2008) was an English science-fiction writer, science writer, futurist, inventor, undersea explorer, and television series host.

He co-wrote the screenplay for the 1968 film '' 2001: A Spac ...

, and was inspired by Clarke's 1951 short story " The Sentinel" and other short stories by Clarke. Clarke also published a novelisation of the film, in part written concurrently with the screenplay, after the film's release. The film stars Keir Dullea

Keir Atwood Dullea (; born May 30, 1936) is an American actor. He played astronaut David Bowman in the 1968 film '' 2001: A Space Odyssey'' and its 1984 sequel, '' 2010: The Year We Make Contact''. His other film roles include '' David and Lisa ...

, Gary Lockwood

Gary Lockwood (born John Gary Yurosek; February 21, 1937) is an American actor. Lockwood is best known for his roles as astronaut Frank Poole in the film '' 2001: A Space Odyssey'' (1968), and as Lieutenant Commander Gary Mitchell in the '' Star ...

, William Sylvester

William Sylvester (January 31, 1922 – January 25, 1995) was an American television and film actor. His most famous film credit was Dr. Heywood Floyd in Stanley Kubrick's '' 2001 A Space Odyssey'' (1968).

Life and career

William Sylves ...

, and Douglas Rain

Douglas James Rain (March 13, 1928 – November 11, 2018) was a Canadian actor and narrator. Although primarily a stage actor, he is perhaps best known for his voicing of the HAL 9000 computer in the film '' 2001: A Space Odyssey'' (1968) and i ...

, and follows a voyage by astronauts, scientists and the sentient

Sentience is the capacity to experience feelings and sensations. The word was first coined by philosophers in the 1630s for the concept of an ability to feel, derived from Latin '' sentientem'' (a feeling), to distinguish it from the ability to ...

supercomputer HAL

HAL may refer to:

Aviation

* Halali Airport (IATA airport code: HAL) Halali, Oshikoto, Namibia

* Hawaiian Airlines (ICAO airline code: HAL)

* HAL Airport, Bangalore, India

* Hindustan Aeronautics Limited an Indian aerospace manufacturer of fight ...

to Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the List of Solar System objects by size, largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but ...

to investigate an alien monolith.

The film is noted for its scientifically accurate depiction of space flight, pioneering special effects

Special effects (often abbreviated as SFX, F/X or simply FX) are illusions or visual tricks used in the theatre, film, television, video game, amusement park and simulator industries to simulate the imagined events in a story or virtual wor ...

, and ambiguous imagery. Kubrick avoided conventional cinematic and narrative techniques; dialogue is used sparingly, and there are long sequences accompanied only by music. The soundtrack incorporates numerous works of classical music

Classical music generally refers to the art music of the Western world, considered to be distinct from Western folk music or popular music traditions. It is sometimes distinguished as Western classical music, as the term "classical music" also ...

, by composers including Richard Strauss

Richard Georg Strauss (; 11 June 1864 – 8 September 1949) was a German composer, conductor, pianist, and violinist. Considered a leading composer of the late Romantic and early modern eras, he has been described as a successor of Richard Wag ...

, Johann Strauss II

Johann Baptist Strauss II (25 October 1825 – 3 June 1899), also known as Johann Strauss Jr., the Younger or the Son (german: links=no, Sohn), was an Austrian composer of light music, particularly dance music and operettas. He composed ov ...

, Aram Khachaturian

Aram Ilyich Khachaturian (; rus, Арам Ильич Хачатурян, , ɐˈram ɨˈlʲjitɕ xətɕɪtʊˈrʲan, Ru-Aram Ilyich Khachaturian.ogg; hy, Արամ Խաչատրյան, ''Aram Xačʿatryan''; 1 May 1978) was a Soviet and Armenian ...

, and György Ligeti

György Sándor Ligeti (; ; 28 May 1923 – 12 June 2006) was a Hungarian-Austrian composer of contemporary classical music. He has been described as "one of the most important avant-garde composers in the latter half of the twentieth century" ...

.

The film received diverse critical responses, ranging from those who saw it as darkly apocalyptic to those who saw it as an optimistic reappraisal of the hopes of humanity. Critics noted its exploration of themes such as human evolution

Human evolution is the evolutionary process within the history of primates that led to the emergence of ''Homo sapiens'' as a distinct species of the hominid family, which includes the great apes. This process involved the gradual development of ...

, technology

Technology is the application of knowledge to reach practical goals in a specifiable and reproducible way. The word ''technology'' may also mean the product of such an endeavor. The use of technology is widely prevalent in medicine, science, ...

, artificial intelligence

Artificial intelligence (AI) is intelligence—perceiving, synthesizing, and inferring information—demonstrated by machines, as opposed to intelligence displayed by animals and humans. Example tasks in which this is done include speech re ...

, and the possibility of extraterrestrial life

Extraterrestrial life, colloquially referred to as alien life, is life that may occur outside Earth and which did not originate on Earth. No extraterrestrial life has yet been conclusively detected, although efforts are underway. Such life might ...

. It was nominated for four Academy Awards

The Academy Awards, better known as the Oscars, are awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international film industry. The awards are regarded by many as the most prestigious, significant awards in the entertainment ind ...

, winning Kubrick the award for his direction of the visual effects

Visual effects (sometimes abbreviated VFX) is the process by which imagery is created or manipulated outside the context of

a live-action shot in filmmaking and video production.

The integration of live-action footage and other live-action foota ...

. The film is now widely regarded as one of the greatest and most influential films ever made. In 1991, it was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the United States Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The library is ...

and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry

The National Film Registry (NFR) is the United States National Film Preservation Board's (NFPB) collection of films selected for preservation, each selected for its historical, cultural and aesthetic contributions since the NFPB’s inception i ...

.

Plot

In a prehistoricveldt

Veld ( or ), also spelled veldt, is a type of wide open rural landscape in :Southern Africa. Particularly, it is a flat area covered in grass or low scrub, especially in the countries of South Africa, Lesotho, Eswatini, Zimbabwe and Botswa ...

, a tribe of hominin

The Hominini form a taxonomic tribe of the subfamily Homininae ("hominines"). Hominini includes the extant genera ''Homo'' (humans) and '' Pan'' (chimpanzees and bonobos) and in standard usage excludes the genus ''Gorilla'' (gorillas).

The t ...

s is driven away from its water hole by a rival tribe. The next day, they find an alien monolith has appeared in their midst. They then learn how to use a bone as a weapon and, after their first hunt, return to drive their rivals away with it.

Millions of years later, Dr. Heywood Floyd, Chairman of the United States National Council of Astronautics, travels to Clavius Base, an American lunar outpost. During a stopover at Space Station 5, he meets Russian scientists who are concerned that Clavius seems to be unresponsive. He refuses to discuss rumours of an epidemic at the base. At Clavius, Heywood addresses a meeting of personnel to whom he stresses the need for secrecy regarding their newest discovery. His mission is to investigate a recently found artefact, a monolith buried four million years earlier near the lunar crater Tycho. As he and others examine the object, it is struck by sunlight, upon which it emits a high-powered radio signal.

Eighteen months later, the American spacecraft ''Discovery One

The United States Spacecraft ''Discovery One'' is a fictional spaceship featured in the first two novels of the ''Space Odyssey'' series by Arthur C. Clarke and in the films ''2001: A Space Odyssey (film), 2001: A Space Odyssey'' (1968) directed ...

'' is bound for Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the List of Solar System objects by size, largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but ...

, with mission pilots and scientists Dr. David "Dave" Bowman and Dr. Frank Poole on board, along with three other scientists in suspended animation

Suspended animation is the temporary (short- or long-term) slowing or stopping of biological function so that physiological capabilities are preserved. It may be either hypometabolic or ametabolic in nature. It may be induced by either endogen ...

. Most of ''Discovery''s operations are controlled by HAL, a HAL 9000

HAL 9000 is a fictional artificial intelligence character and the main antagonist in Arthur C. Clarke's ''Space Odyssey'' series. First appearing in the 1968 film '' 2001: A Space Odyssey'', HAL ( Heuristically programmed ALgorithmic computer ...

computer with a human personality. When HAL reports the imminent failure of an antenna control device, Dave retrieves it in an extravehicular activity

Extravehicular activity (EVA) is any activity done by an astronaut in outer space outside a spacecraft. In the absence of a breathable Earthlike atmosphere, the astronaut is completely reliant on a space suit for environmental support. EVA in ...

(EVA) pod, but finds nothing wrong. HAL suggests reinstalling the device and letting it fail so the problem can be verified. Mission Control advises the astronauts that results from their twin 9000 computer indicate that HAL has made an error, but HAL blames it on human error. Concerned about HAL's behaviour, Dave and Frank enter an EVA pod so they can talk without HAL overhearing. They agree to disconnect HAL if he is proven wrong, but HAL follows their conversation by lip reading

The lips are the visible body part at the mouth of many animals, including humans. Lips are soft, movable, and serve as the opening for food intake and in the articulation of sound and speech. Human lips are a tactile sensory organ, and can be ...

.

While Frank is outside the ship to replace the antenna unit, HAL takes control of his pod, setting him adrift. Dave takes another pod to rescue Frank. While he is outside, HAL turns off the life support

Life support comprises the treatments and techniques performed in an emergency in order to support life after the failure of one or more vital organs. Healthcare providers and emergency medical technicians are generally certified to perform basic ...

functions of the crewmen in suspended animation, killing them. When Dave returns to the ship with Frank's body, HAL refuses to let him back in, stating that their plan to deactivate him jeopardises the mission. Dave releases Frank's body and, despite not having a spacesuit helmet, exits his pod, crosses the vacuum and opens the ship's emergency airlock manually. He goes to HAL's processor core

A central processing unit (CPU), also called a central processor, main processor or just processor, is the electronic circuitry that executes instructions comprising a computer program. The CPU performs basic arithmetic, logic, controlling, and ...

and begins disconnecting HAL's circuits, despite HAL begging him not to. When the disconnection is complete, a prerecorded video by Heywood plays, revealing that the mission's objective is to investigate the radio signal sent from the monolith to Jupiter.

At Jupiter, Dave finds a third, much larger monolith orbiting the planet. He leaves ''Discovery'' in an EVA pod to investigate. He is pulled into a vortex of coloured light and observes bizarre cosmological phenomena and strange landscapes of unusual colours as he passes by. Finally he finds himself in a large neoclassical bedroom where he sees, and then becomes, older versions of himself: first standing in the bedroom, middle-aged and still in his spacesuit, then dressed in leisure attire and eating dinner, and finally as an old man lying in bed. A monolith appears at the foot of the bed, and as Dave reaches for it, he is transformed into a foetus enclosed in a transparent orb of light floating in space above the Earth.

Cast

Production

Development

After completing ''Dr. Strangelove

''Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb'', known simply and more commonly as ''Dr. Strangelove'', is a 1964 black comedy film that satirizes the Cold War fears of a nuclear conflict between the Soviet Union and t ...

'' (1964), director Stanley Kubrick

Stanley Kubrick (; July 26, 1928 – March 7, 1999) was an American film director, producer, screenwriter, and photographer. Widely considered one of the greatest filmmakers of all time, his films, almost all of which are adaptations of nove ...

told a publicist from Columbia Pictures

Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. is an American film production studio that is a member of the Sony Pictures Motion Picture Group, a division of Sony Pictures Entertainment, which is one of the Big Five studios and a subsidiary of the mu ...

that his next project would be about extraterrestrial life

Extraterrestrial life, colloquially referred to as alien life, is life that may occur outside Earth and which did not originate on Earth. No extraterrestrial life has yet been conclusively detected, although efforts are underway. Such life might ...

, and resolved to make "the proverbial good science fiction movie". How Kubrick became interested in creating a science fiction film is far from clear. Biographer John Baxter notes possible inspirations in the late 1950s, including British productions featuring dramas on satellites and aliens modifying early humans, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc., also known as Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures and abbreviated as MGM, is an American film, television production, distribution and media company owned by amazon (company), Amazon through MGM Holdings, founded o ...

's big budget CinemaScope

CinemaScope is an anamorphic lens series used, from 1953 to 1967, and less often later, for shooting widescreen films that, crucially, could be screened in theatres using existing equipment, albeit with a lens adapter. Its creation in 1953 by ...

production ''Forbidden Planet

''Forbidden Planet'' is a 1956 American science fiction film from Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, produced by Nicholas Nayfack, and directed by Fred M. Wilcox (director), Fred M. Wilcox from a script by Cyril Hume that was based on an original film story ...

'', and the slick widescreen cinematography and set design of Japanese ''kaiju

is a Japanese media genre that focuses on stories involving giant monsters. The word ''kaiju'' can also refer to the giant monsters themselves, which are usually depicted attacking major cities and battling either the military or other monster ...

'' (monster movie) productions (such as ''Godzilla

is a fictional monster, or '' kaiju'', originating from a series of Japanese films. The character first appeared in the 1954 film ''Godzilla'' and became a worldwide pop culture icon, appearing in various media, including 32 films produc ...

'' and ''Warning from Space

is a Japanese ''tokusatsu'' science fiction film released in January 1956 by Daiei, and was the first Japanese science fiction film to be produced in color. In the film's plot, starfish-like aliens disguised as humans travel to Earth to warn o ...

'').

Kubrick obtained financing and distribution from the American studio Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer with the selling point that the film could be marketed in their ultra-widescreen Cinerama

Cinerama is a widescreen process that originally projected images simultaneously from three synchronized 35mm projectors onto a huge, deeply curved screen, subtending 146° of arc. The trademarked process was marketed by the Cinerama corporati ...

format, recently debuted with their '' How the West Was Won''. It would be filmed and edited almost entirely in southern England, where Kubrick lived, using the facilities of MGM-British Studios

MGM-British was a subsidiary of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer initially established (as MGM London Films Denham) at Denham Film Studios in 1936. It was in limbo during the Second World War; however, following the end of hostilities, a facility was acquired ...

and Shepperton Studios

Shepperton Studios is a film studio located in Shepperton, Surrey, England, with a history dating back to 1931. It is now part of the Pinewood Studios Group. During its early existence, the studio was branded as Sound City (not to be confused w ...

. MGM had subcontracted the production of the film to Kubrick's production company to qualify for the Eady Levy

The Eady Levy was a tax on box-office receipts in the United Kingdom, intended to support the British film industry. It was introduced in 1950 as a voluntary levy as part of the Eady plan, named after Sir Wilfred Eady, a Treasury official. The le ...

, a UK tax on box-office receipts used at the time to fund the production of films in Britain.

Pre-production

Kubrick's decision to avoid the fanciful portrayals of space found in standard popular science fiction films of the time led him to seek more realistic and accurate depictions of space travel. Illustrators such asChesley Bonestell

Chesley Knight Bonestell Jr. (January 1, 1888 – June 11, 1986) was an American painter, designer and illustrator. His paintings inspired the American space program, and they have been (and remain) influential in science fiction art and illustr ...

, Roy Carnon, and Richard McKenna were hired to produce concept drawings, sketches, and paintings of the space technology seen in the film. Two educational films, the National Film Board of Canada

The National Film Board of Canada (NFB; french: Office national du film du Canada (ONF)) is Canada's public film and digital media producer and distributor. An agency of the Government of Canada, the NFB produces and distributes documentary f ...

's 1960 animated short documentary ''Universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the universe. Acc ...

'' and the 1964 New York World's Fair

The 1964–1965 New York World's Fair was a world's fair that held over 140 pavilions and 110 restaurants, representing 80 nations (hosted by 37), 24 US states, and over 45 corporations with the goal and the final result of building exhibits or ...

movie ''To the Moon and Beyond

''To The Moon and Beyond'' is a special motion picture produced for and shown at the 1964/1965 New York World's Fair. It depicted traveling from Earth out to an overall view of the universe and back again, zooming down to the atomic scale. It w ...

'', were major influences.

According to biographer Vincent LoBrutto, ''Universe'' was a visual inspiration to Kubrick. The 29-minute film, which had also proved popular at NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeeding t ...

for its realistic portrayal of outer space, met "the standard of dynamic visionary realism that he was looking for." Wally Gentleman, one of the special-effects artists on ''Universe'', worked briefly on ''2001''. Kubrick also asked ''Universe'' co-director Colin Low about animation camerawork, with Low recommending British mathematician Brian Salt, with whom Low and Roman Kroitor

Roman Kroitor (December 12, 1926 – September 17, 2012) was a Canadian filmmaker who was known as an early practitioner of ''cinéma vérité'', as co-founder of IMAX, and as creator of the Sandde hand-drawn stereoscopic animation system. H ...

had previously worked on the 1957 still-animation documentary '' City of Gold''. ''Universe''s narrator, actor Douglas Rain

Douglas James Rain (March 13, 1928 – November 11, 2018) was a Canadian actor and narrator. Although primarily a stage actor, he is perhaps best known for his voicing of the HAL 9000 computer in the film '' 2001: A Space Odyssey'' (1968) and i ...

, was cast as the voice of HAL.

After pre-production had begun, Kubrick saw ''To the Moon and Beyond'', a film shown in the Transportation and Travel building at the 1964 World's Fair

The 1964–1965 New York World's Fair was a world's fair that held over 140 pavilions and 110 restaurants, representing 80 nations (hosted by 37), 24 US states, and over 45 corporations with the goal and the final result of building exhibits or ...

. It was filmed in Cinerama 360 and shown in the "Moon Dome". Kubrick hired the company that produced it, Graphic Films Corporation—which had been making films for NASA, the US Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the air service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part of the United States Army Signal ...

, and various aerospace clients—as a design consultant. Graphic Films' Con Pederson, Lester Novros

Lester Novros (January 27, 1909 – September 10, 2000) was an American artist, animator, and teacher.

Early life

Lester Novros was born in Passaic, New Jersey on January 27, 1909. Novros studied painting at the National Academy of Design in ...

, and background artist Douglas Trumbull

Douglas Hunt Trumbull (; April 8, 1942 – February 7, 2022) was an American film director and innovative visual effects supervisor. He pioneered methods in special effects and created scenes for '' 2001: A Space Odyssey'', ''Close Encounters o ...

airmailed research-based concept sketches and notes covering the mechanics and physics of space travel, and created storyboard

A storyboard is a graphic organizer that consists of illustrations or images displayed in sequence for the purpose of pre-visualizing a motion picture, animation, motion graphic or interactive media sequence. The storyboarding process, i ...

s for the space flight sequences in ''2001''. Trumbull became a special effects supervisor on ''2001''.

Writing

Searching for a collaborator in thescience fiction

Science fiction (sometimes shortened to Sci-Fi or SF) is a genre of speculative fiction which typically deals with imaginative and futuristic concepts such as advanced science and technology, space exploration, time travel, parallel unive ...

community for the writing of the script, Kubrick was advised by a mutual acquaintance, Columbia Pictures

Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. is an American film production studio that is a member of the Sony Pictures Motion Picture Group, a division of Sony Pictures Entertainment, which is one of the Big Five studios and a subsidiary of the mu ...

staff member Roger Caras

Roger Andrew Caras (May 24, 1928 – February 18, 2001) was an American wildlife photographer, writer, wildlife preservationist and television personality.

Known as the host of the annual Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show, Caras was the author o ...

, to talk to writer Arthur C. Clarke

Sir Arthur Charles Clarke (16 December 191719 March 2008) was an English science-fiction writer, science writer, futurist, inventor, undersea explorer, and television series host.

He co-wrote the screenplay for the 1968 film '' 2001: A Spac ...

, who lived in Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

. Although convinced that Clarke was "a recluse, a nut who lives in a tree," Kubrick allowed Caras to cable the film proposal to Clarke. Clarke's cabled response stated that he was "frightfully interested in working with hat

A hat is a head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorporate mecha ...

''enfant terrible

''Enfant terrible'' (; ; "terrible child") is a French expression, traditionally referring to a child who is terrifyingly candid by saying embarrassing things to parents or others. However, the expression has drawn multiple usage in careers of ...

''", and added "what makes Kubrick think I'm a recluse?" Meeting for the first time at Trader Vic's

Trader Vic's is a restaurant and tiki bar chain headquartered in Emeryville, California, United States. Victor Jules Bergeron, Jr. (December 10, 1902 in San Francisco – October 11, 1984 in Hillsborough, California) founded a chain of Polynesi ...

in New York on 22 April 1964, the two began discussing the project that would take up the next four years of their lives. Clarke kept a diary throughout his involvement with ''2001'', excerpts of which were published in 1972 as ''The Lost Worlds of 2001

''The Lost Worlds of 2001'' is a 1972 book by English writer Arthur C. Clarke, published as an accompaniment to the novel '' 2001: A Space Odyssey''.

The book consists in part of behind-the-scenes notes from Clarke concerning scriptwriting (and ...

''.

Kubrick told Clarke he wanted to make a film about "Man's relationship to the universe", and was, in Clarke's words, "determined to create a work of art which would arouse the emotions of wonder, awe ... even, if appropriate, terror". Clarke offered Kubrick six of his short stories, and by May 1964, Kubrick had chosen " The Sentinel" as the source material for the film. In search of more material to expand the film's plot, the two spent the rest of 1964 reading books on science and anthropology, screening science fiction films, and brainstorming ideas. They created the plot for ''2001'' by integrating several different short story plots written by Clarke, along with new plot segments requested by Kubrick for the film development, and then combined them all into a single script for ''2001''. Clarke said that his 1953 story "

Kubrick told Clarke he wanted to make a film about "Man's relationship to the universe", and was, in Clarke's words, "determined to create a work of art which would arouse the emotions of wonder, awe ... even, if appropriate, terror". Clarke offered Kubrick six of his short stories, and by May 1964, Kubrick had chosen " The Sentinel" as the source material for the film. In search of more material to expand the film's plot, the two spent the rest of 1964 reading books on science and anthropology, screening science fiction films, and brainstorming ideas. They created the plot for ''2001'' by integrating several different short story plots written by Clarke, along with new plot segments requested by Kubrick for the film development, and then combined them all into a single script for ''2001''. Clarke said that his 1953 story "Encounter in the Dawn

"Encounter in the Dawn" (also known as "Expedition to Earth") is a short story by English writer Arthur C. Clarke, first published in 1953 in the magazine ''Amazing Stories''. It was originally collected in the anthology '' Expedition to Ear ...

" inspired the film's "Dawn of Man" sequence.

Kubrick and Clarke privately referred to the project as ''How the Solar System Was Won'', a reference to how it was a follow-on to MGM's Cinerama epic ''How the West Was Won''. On 23 February 1965, Kubrick issued a press release announcing the title as ''Journey Beyond The Stars''. Other titles considered included ''Universe'', ''Tunnel to the Stars'', and ''Planetfall''. Expressing his high expectations for the thematic importance which he associated with the film, in April 1965, eleven months after they began working on the project, Kubrick selected ''2001: A Space Odyssey''; Clarke said the title was "entirely" Kubrick's idea. Intending to set the film apart from the "monsters-and-sex" type of science-fiction films of the time, Kubrick used Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

s ''The Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Iliad'', the ...

'' as both a model of literary merit and a source of inspiration for the title. Kubrick said, "It occurred to us that for the Greeks the vast stretches of the sea must have had the same sort of mystery and remoteness that space has for our generation."

Originally, Kubrick and Clarke had planned to develop a ''2001'' novel first, free of the constraints of film, and then write the screenplay. They planned the writing credits to be "Screenplay by Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke, based on a novel by Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick" to reflect their preeminence in their respective fields. In practice, the screenplay developed in parallel with the novel, with only some elements being common to both. In a 1970 interview, Kubrick said:

In the end, Clarke and Kubrick wrote parts of the novel and screenplay simultaneously, with the film version being released before the book version was published. Clarke opted for clearer explanations of the mysterious monolith and Star Gate in the novel; Kubrick made the film more cryptic by minimising dialogue and explanation. Kubrick said the film is "basically a visual, nonverbal experience" that "hits the viewer at an inner level of consciousness, just as music does, or painting".

The screenplay credits were shared whereas the ''2001'' novel, released shortly after the film, was attributed to Clarke alone. Clarke wrote later that "the nearest approximation to the complicated truth" is that the screenplay should be credited to "Kubrick and Clarke" and the novel to "Clarke and Kubrick". Early reports about tensions involved in the writing of the film script appeared to reach a point where Kubrick was allegedly so dissatisfied with the collaboration that he approached other writers who could replace Clarke, including Michael Moorcock

Michael John Moorcock (born 18 December 1939) is an English writer, best-known for science fiction and fantasy, who has published a number of well-received literary novels as well as comic thrillers, graphic novels and non-fiction. He has work ...

and J. G. Ballard

James Graham Ballard (15 November 193019 April 2009) was an English novelist, short story writer, satirist, and essayist known for provocative works of fiction which explored the relations between human psychology, technology, sex, and mass medi ...

. But they felt it would be disloyal to accept Kubrick's offer. In Michael Benson's 2018 book ''Space Odyssey: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke, and the Making of a Masterpiece'', the actual relation between Clarke and Kubrick was more complex, involving an extended interaction of Kubrick's multiple requests for Clarke to write new plot lines for various segments of the film, which Clarke was expected to withhold from publication until after the release of the film while receiving advances on his salary from Kubrick during film production. Clarke agreed to this, though apparently he did make several requests for Kubrick to allow him to develop his new plot lines into separate publishable stories while film production continued, which Kubrick consistently denied on the basis of Clarke's contractual obligation to withhold publication until release of the film.

Astronomer Carl Sagan

Carl Edward Sagan (; ; November 9, 1934December 20, 1996) was an American astronomer, planetary scientist, cosmologist, astrophysicist, astrobiologist, author, and science communicator. His best known scientific contribution is research on ext ...

wrote in his 1973 book '' The Cosmic Connection'' that Clarke and Kubrick had asked him how to best depict extraterrestrial intelligence

Extraterrestrial intelligence (often abbreviated ETI) refers to hypothetical intelligent extraterrestrial life. The question of whether other inhabited worlds might exist has been debated since ancient times. The modern form of the concept emerged ...

. While acknowledging Kubrick's desire to use actors to portray humanoid aliens for convenience's sake, Sagan argued that alien life forms were unlikely to bear any resemblance to terrestrial life, and that to do so would introduce "at least an element of falseness" to the film. Sagan proposed that the film should simply suggest extraterrestrial superintelligence

A superintelligence is a hypothetical agent that possesses intelligence far surpassing that of the brightest and most gifted human minds. "Superintelligence" may also refer to a property of problem-solving systems (e.g., superintelligent language ...

, rather than depict it. He attended the premiere and was "pleased to see that I had been of some help." Sagan had met with Clarke and Kubrick only once, in 1964; and Kubrick subsequently directed several attempts to portray credible aliens, only to abandon the idea near the end of post-production. Benson asserts it is unlikely that Sagan's advice had any direct influence. Kubrick hinted at the nature of the mysterious unseen alien race in ''2001'' by suggesting that given millions of years of evolution, they progressed from biological beings to "immortal machine entities" and then into "beings of pure energy and spirit" with "limitless capabilities and ungraspable intelligence".

In a 1980 interview (not released during Kubrick's lifetime), Kubrick explains one of the film's closing scenes, where Bowman is depicted in old age after his journey through the Star Gate:

The script went through many stages. In early 1965, when backing was secured for the film, Clarke and Kubrick still had no firm idea of what would happen to Bowman after the Star Gate sequence. Initially all of ''Discovery''s astronauts were to survive the journey; by 3 October, Clarke and Kubrick had decided to make Bowman the sole survivor and have him regress to infancy. By 17 October, Kubrick had come up with what Clarke called a "wild idea of slightly fag robots who create a Victorian

Victorian or Victorians may refer to:

19th century

* Victorian era, British history during Queen Victoria's 19th-century reign

** Victorian architecture

** Victorian house

** Victorian decorative arts

** Victorian fashion

** Victorian literature ...

environment to put our heroes at their ease." HAL 9000 was originally named Athena after the Greek goddess of wisdom and had a feminine voice and persona.

Early drafts included a prologue containing interviews with scientists about extraterrestrial life,. voice-over

Voice-over (also known as off-camera or off-stage commentary) is a production technique where a voice—that is not part of the narrative (non-Diegetic#Film sound and music, diegetic)—is used in a radio, television production, filmmaking, th ...

narration (a feature in all of Kubrick's previous films), a stronger emphasis on the prevailing Cold War balance of terror

The phrase "balance of terror" is usually, but not invariably,Rich Miller, Simon Kennedy'G-20 Plans to End 'Financial Balance of Terror' After Summit,'Bloomberg 27 February 2009. used in reference to the nuclear arms race between the United State ...

, and a different and more explicitly explained breakdown for HAL. Other changes include a different monolith for the "Dawn of Man" sequence, discarded when early prototypes did not photograph well; the use of Saturn as the final destination of the ''Discovery'' mission rather than Jupiter, discarded when the special effects team could not develop a convincing rendition of Saturn's rings

The rings of Saturn are the most extensive ring system of any planet in the Solar System. They consist of countless small particles, ranging in size from micrometers to meters, that orbit around Saturn. The ring particles are made almost entirel ...

; and the finale of the Star Child exploding nuclear weapons carried by Earth-orbiting satellites, which Kubrick discarded for its similarity to his previous film, ''Dr. Strangelove

''Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb'', known simply and more commonly as ''Dr. Strangelove'', is a 1964 black comedy film that satirizes the Cold War fears of a nuclear conflict between the Soviet Union and t ...

''. The finale and many of the other discarded screenplay ideas survived in Clarke's novel.

Kubrick made further changes to make the film more nonverbal, to communicate on a visual and visceral level rather than through conventional narrative. By the time shooting began, Kubrick had removed much of the dialogue and narration. Long periods without dialogue permeate the film: the film has no dialogue for roughly the first and last twenty minutes, as well as for the 10 minutes from Floyd's Moonbus landing near the monolith until Poole watches a BBC newscast on ''Discovery''. What dialogue remains is notable for its banality (making the computer HAL seem to have more emotion than the humans) when juxtaposed with the epic space scenes. Vincent LoBrutto wrote that Clarke's novel has its own "strong narrative structure" and precision, while the narrative of the film remains symbolic, in accord with Kubrick's final intentions.

Filming

Principal photography

Principal photography is the phase of producing a film or television show in which the bulk of shooting takes place, as distinct from the phases of pre-production and post-production.

Personnel

Besides the main film personnel, such as actor ...

began on 29 December 1965, in Stage H at Shepperton Studios

Shepperton Studios is a film studio located in Shepperton, Surrey, England, with a history dating back to 1931. It is now part of the Pinewood Studios Group. During its early existence, the studio was branded as Sound City (not to be confused w ...

, Shepperton

Shepperton is an urban village in the Borough of Spelthorne, Surrey, approximately south west of central London. Shepperton is equidistant between the towns of Chertsey and Sunbury-on-Thames. The village is mentioned in a document of 959 AD ...

, England. The studio was chosen because it could house the pit for the Tycho crater excavation scene, the first to be shot. In January 1966, the production moved to the smaller MGM-British Studios

MGM-British was a subsidiary of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer initially established (as MGM London Films Denham) at Denham Film Studios in 1936. It was in limbo during the Second World War; however, following the end of hostilities, a facility was acquired ...

in Borehamwood

Borehamwood (, historically also Boreham Wood) is a town in southern Hertfordshire, England, from Charing Cross. Borehamwood has a population of 31,074, and is within the London commuter belt. The town's film and TV studios are commonly known ...

, where the live-action and special-effects filming was done, starting with the scenes involving Floyd on the Orion spaceplane; it was described as a "huge throbbing nerve center ... with much the same frenetic atmosphere as a Cape Kennedy blockhouse during the final stages of Countdown." Excerpted in . The only scene not filmed in a studio—and the last live-action scene shot for the film—was the skull-smashing sequence, in which Moonwatcher (Richter) wields his newfound bone "weapon-tool" against a pile of nearby animal bones. A small elevated platform was built in a field near the studio so that the camera could shoot upward with the sky as background, avoiding cars and trucks passing by in the distance. The ''Dawn of Man'' sequence that opens the film was shot at Borehamwood with John Alcott

John Alcott, BSC (27 November 1930 – 28 July 1986) was an English cinematographer known for his four collaborations with director Stanley Kubrick: '' 2001: A Space Odyssey'' (1968), for which he took over as lighting cameraman from Geoffrey ...

as cinematographer after Geoffrey Unsworth

Geoffrey Gilyard Unsworth, Order of the British Empire, OBE, British Society of Cinematographers, BSC (26 May 1914 – 28 October 1978) was a British cinematographer who worked on nearly 90 feature films spanning over more than 40 years. He is b ...

left to work on other projects. The still photographs used as backgrounds for the ''Dawn of Man'' sequence were taken in Namibia

Namibia (, ), officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country in Southern Africa. Its western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Zambia and Angola to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and ea ...

.

Filming of actors was completed in September 1967, and from June 1966 until March 1968, Kubrick spent most of his time working on the 205 special-effects shots in the film. He ordered the special-effects technicians to use the painstaking process of creating all visual effects seen in the film "in camera

''In camera'' (; Latin: "in a chamber"). is a legal term that means ''in private''. The same meaning is sometimes expressed in the English equivalent: ''in chambers''. Generally, ''in-camera'' describes court cases, parts of it, or process wh ...

", avoiding degraded picture quality from the use of blue screen and travelling matte

Mattes are used in photography and special effects filmmaking to combine two or more image elements into a single, final image. Usually, mattes are used to combine a foreground image (e.g. actors on a set) with a background image (e.g. a scenic ...

techniques. Although this technique, known as "held takes", resulted in a much better image, it meant exposed film would be stored for long periods of time between shots, sometimes as long as a year. In March 1968, Kubrick finished the "pre-premiere" editing of the film, making his final cuts just days before the film's general release in April 1968.

The film was announced in 1965 as a "Cinerama

Cinerama is a widescreen process that originally projected images simultaneously from three synchronized 35mm projectors onto a huge, deeply curved screen, subtending 146° of arc. The trademarked process was marketed by the Cinerama corporati ...

" film and was photographed in Super Panavision 70

Super Panavision 70 is the marketing brand name used to identify movies photographed with Panavision 70 mm spherical optics between 1959 and 1983.

Ultra Panavision 70 was similar to Super Panavision 70, though Ultra Panavision lenses were anamorp ...

(which uses a 65 mm negative combined with spherical lenses to create an aspect ratio of 2.20:1). It would eventually be released in a limited "roadshow

Roadshow theatrical release is a practice in which a film opened in a limited number of theaters in large cities.

Road show or Road Show may also refer to:

*''Antiques Roadshow'', a BBC TV series where antiques specialist travel around the country ...

" Cinerama

Cinerama is a widescreen process that originally projected images simultaneously from three synchronized 35mm projectors onto a huge, deeply curved screen, subtending 146° of arc. The trademarked process was marketed by the Cinerama corporati ...

version, then in 70 mm and 35 mm versions. Colour processing and 35 mm release prints were done using Technicolor

Technicolor is a series of Color motion picture film, color motion picture processes, the first version dating back to 1916, and followed by improved versions over several decades.

Definitive Technicolor movies using three black and white films ...

's dye transfer process. The 70 mm prints were made by MGM Laboratories, Inc. on Metrocolor

Metrocolor is the trade name used by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) for films processed at their laboratory. Virtually all of these films were shot on Kodak's Eastmancolor film.

Although MGM used Kodak film products, MGM did not use all of Kodak's proc ...

. The production was $4.5 million over the initial $6 million budget and 16 months behind schedule.

For the opening sequence involving tribes of apes, professional mime

Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions (MIME) is an Internet standard that extends the format of email messages to support text in character sets other than ASCII, as well as attachments of audio, video, images, and application programs. Message ...

Daniel Richter played the lead ape and choreographed the movements of the other man-apes, who were mostly portrayed by his mime troupe.

Kubrick and Clarke consulted IBM on plans for HAL, though plans to use the company's logo never materialised.

Post-production

The film was edited before it was publicly screened, cutting out, among other things, a painting class on the lunar base that included Kubrick's daughters, additional scenes of life on the base, and Floyd buying abush baby

Galagos , also known as bush babies, or ''nagapies'' (meaning "night monkeys" in Afrikaans), are small nocturnal primates native to continental, sub-Sahara Africa, and make up the family Galagidae (also sometimes called Galagonidae). They ar ...

for his daughter from a department store via videophone. A ten-minute black-and-white opening sequence featuring interviews with scientists, including Freeman Dyson

Freeman John Dyson (15 December 1923 – 28 February 2020) was an English-American theoretical physicist and mathematician known for his works in quantum field theory, astrophysics, random matrices, mathematical formulation of quantum m ...

discussing off-Earth life, was removed after an early screening for MGM executives.

Music

From early in production, Kubrick decided that he wanted the film to be a primarily nonverbal experience that did not rely on the traditional techniques ofnarrative

A narrative, story, or tale is any account of a series of related events or experiences, whether nonfictional (memoir, biography, news report, documentary, travel literature, travelogue, etc.) or fictional (fairy tale, fable, legend, thriller (ge ...

cinema, and in which music would play a vital role in evoking particular moods. About half the music in the film appears either before the first line of dialogue or after the final line. Almost no music is heard during scenes with dialogue.

The film is notable for its innovative use of classical music

Classical music generally refers to the art music of the Western world, considered to be distinct from Western folk music or popular music traditions. It is sometimes distinguished as Western classical music, as the term "classical music" also ...

taken from existing commercial recordings. Most feature films, then and now, are typically accompanied by elaborate film scores

A film score is original music written specifically to accompany a film. The score comprises a number of orchestral, instrumental, or choral pieces called cues, which are timed to begin and end at specific points during the film in order to e ...

or songs written specially for them by professional composers. In the early stages of production, Kubrick commissioned a score for ''2001'' from Hollywood composer Alex North

Alex North (born Isadore Soifer, December 4, 1910 – September 8, 1991) was an American composer best known for his many film scores, including ''A Streetcar Named Desire'' (one of the first jazz-based film scores), ''Viva Zapata!'', ''Spa ...

, who had written the score for ''Spartacus

Spartacus ( el, Σπάρτακος '; la, Spartacus; c. 103–71 BC) was a Thracian gladiator who, along with Crixus, Gannicus, Castus, and Oenomaus, was one of the escaped slave leaders in the Third Servile War, a major slave uprising ...

'' and also had worked on ''Dr. Strangelove

''Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb'', known simply and more commonly as ''Dr. Strangelove'', is a 1964 black comedy film that satirizes the Cold War fears of a nuclear conflict between the Soviet Union and t ...

''. During post-production, Kubrick chose to abandon North's music in favour of the now-familiar classical pieces he had earlier chosen as temporary music

''Temporary Music'' is the 1979 debut EP and 1981 debut album by the New York based no wave music group Material.

The band had previously worked with Daevid Allen on New York Gong's 1979 '' About Time'' album. The ''Temporary Music 1'' EP was r ...

for the film. North did not learn that his score had been abandoned until he saw the film's premiere.

Design and special effects

Costumes and set design

Kubrick involved himself in every aspect of production, even choosing the fabric for his actors' costumes, and selecting notable pieces of contemporary furniture for use in the film. When Floyd exits the Space Station5 elevator, he is greeted by an attendant seated behind a slightly modified George Nelson Action Office desk fromHerman Miller

Herman Miller, officially MillerKnoll, Inc., is an American company that produces office furniture, equipment, and home furnishings, including the Aeron chair, Noguchi table, Marshmallow sofa, and the Eames Lounge Chair. Herman Miller is also ...

's 1964 "Action Office

The Action Office is a series of furniture designed by Robert Propst, and manufactured and marketed by Herman Miller. First introduced in 1964 as the ''Action Office I'' product line, then superseded by the ''Action Office II'' series, it is an i ...

" series. Danish designer Arne Jacobsen

Arne Emil Jacobsen, Hon. FAIA () 11 February 1902 – 24 March 1971) was a Danish architect and furniture designer. He is remembered for his contribution to architectural functionalism and for the worldwide success he enjoyed with simple we ...

designed the cutlery used by the ''Discovery'' astronauts in the film.

Other examples of modern furniture in the film are the bright red Djinn chairs seen prominently throughout the space station and Eero Saarinen

Eero Saarinen (, ; August 20, 1910 – September 1, 1961) was a Finnish-American architect and industrial designer noted for his wide-ranging array of designs for buildings and monuments. Saarinen is best known for designing the General Motors ...

's 1956 pedestal tables. Olivier Mourgue

Olivier Mourgue (born 1939) is a French industrial designer best known as the designer of the futuristic Djinn chairs used in the film ''2001: A Space Odyssey (film), 2001: A Space Odyssey''.

Life and career

Mourgue was born in Paris, France. He ...

, designer of the Djinn chair, has used the connection to ''2001'' in his advertising; a frame from the film's space station sequence and three production stills appear on the homepage of Mourgue's website. Shortly before Kubrick's death, film critic Alexander Walker informed Kubrick of Mourgue's use of the film, joking to him "You're keeping the price up". Commenting on their use in the film, Walker writes:

Detailed instructions in relatively small print for various technological devices appear at several points in the film, the most visible of which are the lengthy instructions for the zero-gravity toilet on the Aries Moon shuttle. Similar detailed instructions for replacing the explosive bolts

A pyrotechnic fastener (also called an explosive bolt, or pyro, within context) is a fastener, usually a nut or bolt, that incorporates a Explosive material, pyrotechnic charge that can be initiated remotely. One or more explosive charges embedde ...

also appear on the hatches of the EVA pods, most visibly in closeup just before Bowman's pod leaves the ship to rescue Frank Poole.

The film features an extensive use of Eurostile

Eurostile is a geometric sans-serif typeface designed by Aldo Novarese in 1962. Novarese created Eurostile for one of the best-known Italian foundries, Nebiolo, in Turin.

Novarese developed Eurostile to succeed the similar Microgramma, which ...

Bold Extended, Futura and other sans serif

In typography and lettering, a sans-serif, sans serif, gothic, or simply sans letterform is one that does not have extending features called "serifs" at the end of strokes. Sans-serif typefaces tend to have less stroke width variation than seri ...

typeface

A typeface (or font family) is the design of lettering that can include variations in size, weight (e.g. bold), slope (e.g. italic), width (e.g. condensed), and so on. Each of these variations of the typeface is a font.

There are list of type ...

s as design elements of the ''2001'' world. Computer displays show high-resolution fonts, colour, and graphics that were far in advance of what most computers were capable of in the 1960s, when the film was made.

Design of the monolith

Kubrick was personally involved in the design of the monolith and its form for the film. The first design for the monolith for the ''2001'' film was a transparenttetrahedral

In geometry, a tetrahedron (plural: tetrahedra or tetrahedrons), also known as a triangular pyramid, is a polyhedron composed of four triangular faces, six straight edges, and four vertex corners. The tetrahedron is the simplest of all the o ...

pyramid. This was taken from the short story " The Sentinel" that the first story was based on.

A London firm was approached by Kubrick to provide a transparent plexiglass

Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) belongs to a group of materials called engineering plastics. It is a transparent thermoplastic. PMMA is also known as acrylic, acrylic glass, as well as by the trade names and brands Crylux, Plexiglas, Acrylite, ...

pyramid, and due to construction constraints they recommended a flat slab shape. Kubrick approved, but was disappointed with the glassy appearance of the transparent prop on set, leading art director Anthony Masters to suggest making the monolith's surface matte black.

Models

To heighten the reality of the film, very intricate models of the various spacecraft and locations were built. Their sizes ranged from about two-foot-long models of satellites and the Aries translunar shuttle up to the -long model of the ''Discovery One'' spacecraft. "In-camera" techniques were again used as much as possible to combine models and background shots together to prevent degradation of the image through duplication. In shots where there was no perspective change, still shots of the models were photographed and positive paper prints were made. The image of the model was cut out of the photographic print and mounted on glass and filmed on ananimation stand

An animation stand is a device assembled for the filming of any kind of animation that is placed on a flat surface, including cel animation, graphic animation, clay animation, and silhouette animation.

Traditionally, the flat surface that the a ...

. The undeveloped film was re-wound to film the star background with the silhouette of the model photograph acting as a matte

Matte may refer to:

Art

* paint with a non-glossy finish. See diffuse reflection.

* a framing element surrounding a painting or watercolor within the outer frame

Film

* Matte (filmmaking), filmmaking and video production technology

* Matte pai ...

to block out where the spaceship image was.

Shots where the spacecraft had parts in motion or the perspective changed were shot by directly filming the model. For most shots the model was stationary and camera was driven along a track on a special mount, the motor of which was mechanically linked to the camera motor—making it possible to repeat camera moves and match speeds exactly. Elements of the scene were recorded on the same piece of film in separate passes to combine the lit model, stars, planets, or other spacecraft in the same shot. In moving shots of the long ''Discovery One'' spacecraft, in order to keep the entire model in focus (and preserve its sense of scale), the camera's aperture was stopped down for maximum depth-of-field, and each frame was exposed for several seconds. Many matting techniques were tried to block out the stars behind the models, with filmmakers sometimes resorting to hand-tracing frame by frame around the image of the spacecraft (rotoscoping

Rotoscoping is an animation technique that animators use to trace over motion picture footage, frame by frame, to produce realistic action. Originally, animators projected photographed live-action movie images onto a glass panel and traced ov ...

) to create the matte.

Some shots required exposing the film again to record previously filmed live-action shots of the people appearing in the windows of the spacecraft or structures. This was achieved by projecting the window action onto the models in a separate camera pass or, when two-dimensional photographs were used, projecting from the backside through a hole cut in the photograph.

All of the shots required multiple takes so that some film could be developed and printed to check exposure, density, alignment of elements, and to supply footage used for other photographic effects, such as for matting.

Rotating sets

For spacecraft interior shots, ostensibly containing a giant centrifuge that producesartificial gravity

Artificial gravity is the creation of an inertial force that mimics the effects of a gravitational force, usually by rotation.

Artificial gravity, or rotational gravity, is thus the appearance of a centrifugal force in a rotating frame of r ...

, Kubrick had a rotating "ferris wheel" built by Vickers-Armstrong

Vickers-Armstrongs Limited was a British engineering conglomerate formed by the merger of the assets of Vickers Limited and Sir W G Armstrong Whitworth & Company in 1927. The majority of the company was nationalised in the 1960s and 1970s, w ...

Engineering Group at a cost of $750,000. The set was in diameter and wide. Various scenes in the ''Discovery'' centrifuge were shot by securing set pieces within the wheel, then rotating it while the actor walked or ran in sync with its motion, keeping him at the bottom of the wheel as it turned. The camera could be fixed to the inside of the rotating wheel to show the actor walking completely "around" the set, or mounted in such a way that the wheel rotated independently of the stationary camera, as in the jogging scene where the camera appears to alternately precede and follow the running actor.

The shots where the actors appear on opposite sides of the wheel required one of the actors to be strapped securely into place at the "top" of the wheel as it moved to allow the other actor to walk to the "bottom" of the wheel to join him. The most notable case is when Bowman enters the centrifuge from the central hub on a ladder, and joins Poole, who is eating on the other side of the centrifuge. This required Gary Lockwood to be strapped into a seat while Keir Dullea walked toward him from the opposite side of the wheel as it turned with him.

Another rotating set appeared in an earlier sequence on board the Aries trans-lunar shuttle. A stewardess is shown preparing in-flight meals, then carrying them into a circular walkway. Attached to the set as it rotates 180 degrees, the camera's point of view remains constant, and she appears to walk up the "side" of the circular walkway, and steps, now in an "upside-down" orientation, into a connecting hallway.

Zero-gravity effects

The realistic-looking effects of the astronauts floating weightless in space and inside the spacecraft were accomplished by suspending the actors from wires attached to the top of the set and placing the camera beneath them. The actors' bodies blocked the camera's view of the wires and appeared to float. For the shot of Poole floating into the pod's arms during Bowman's recovery of him, a stuntman on a wire portrayed the movements of an unconscious man and was shot in slow motion to enhance the illusion of drifting through space. The scene showing Bowman entering the emergency airlock from the EVA pod was done similarly: an off-camera stagehand, standing on a platform, held the wire suspending Dullea above the camera positioned at the bottom of the vertically oriented airlock. At the proper moment, the stage-hand first loosened his grip on the wire, causing Dullea to fall toward the camera, then, while holding the wire firmly, jumped off the platform, causing Dullea to ascend back toward the hatch. The methods used were alleged to have placed stuntmanBill Weston

Bill Weston (29 May 1941 - 25 March 2012) was a British stunt performer and actor, whose 40-year career includes credits for ''Saving Private Ryan'', ''Titanic'', '' Raiders of the Lost Ark'', The Living Daylights and ''Batman Begins''.

Filmograp ...

's life in danger. Weston recalled that he filmed one sequence without air-holes in his suit, risking asphyxiation. "Even when the tank was feeding air into the suit, there was no place for the carbon dioxide Weston exhaled to go. So it simply built up inside, incrementally causing a heightened heart rate, rapid breathing, fatigue, clumsiness, and eventually, unconsciousness." Weston said Kubrick was warned "we've got to get him back" but reportedly replied, "Damn it, we just started. Leave him up there! Leave him up there!" When Weston lost consciousness, filming ceased, and he was brought down. "They brought the tower in, and I went looking for Stanley,... I was going to shove MGM right up his... And the thing is, Stanley had left the studio and sent Victor yndon, the associate producerto talk to me." Weston claimed Kubrick fled the studio for "two or three days. ... I know he didn't come in the next day, and I'm sure it wasn't the day after. Because I was going to do him."

"Star Gate" sequence

The coloured lights in the Star Gate sequence were accomplished byslit-scan photography

The slit-scan photography technique is a photographic and cinematographic process where a moveable slide, into which a slit has been cut, is inserted between the camera and the subject to be photographed.

More generally, "slit-scan photography" ...

of thousands of high-contrast images on film, including Op art

Op art, short for optical art, is a style of visual art that uses optical illusions.

Op artworks are abstract, with many better-known pieces created in black and white. Typically, they give the viewer the impression of movement, hidden images ...

paintings, architectural drawings, Moiré pattern

In mathematics, physics, and art, moiré patterns ( , , ) or moiré fringes are large-scale interference patterns that can be produced when an opaque ruled pattern with transparent gaps is overlaid on another similar pattern. For the moiré ...

s, printed circuits, and electron-microscope photographs of molecular and crystal structures. Known to staff as "Manhattan Project", the shots of various nebula-like phenomena, including the expanding star field, were coloured paints and chemicals swirling in a pool-like device known as a cloud tank, shot in slow motion in a dark room. The live-action landscape shots were filmed in the Hebrides, Hebridean islands, the Mountains and hills of Scotland, mountains of northern Scotland, and Monument Valley. The colouring and negative-image effects were achieved with different colour filters in the process of making duplicate negatives in an optical printer.

Visual effects

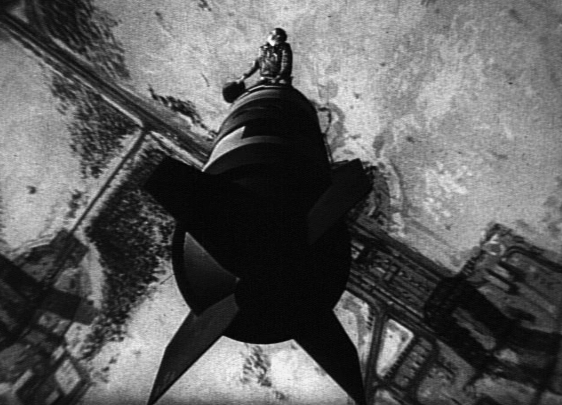

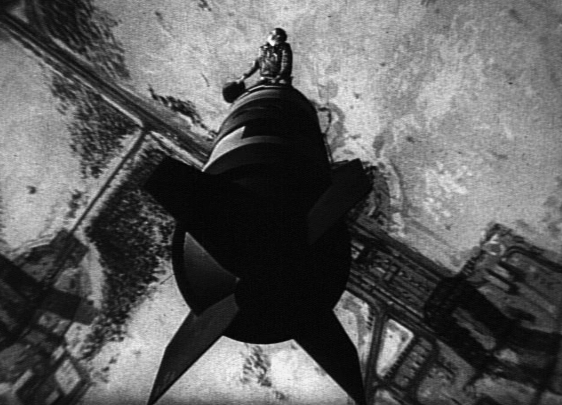

''2001'' contains a famous example of a match cut, a type of cut in which two shots are matched by action or subject matter. After Moonwatcher uses a bone to kill another ape at the watering hole, he throws it triumphantly into the air; as the bone spins in the air, the film cuts to an orbiting satellite, marking the end of the prologue. The match cut draws a connection between the two objects as exemplars of primitive and advanced tools respectively, and demonstrates humanity's technological progress since the time of early hominids. ''2001'' pioneered the use of Front projection effect, front projection with retroreflective matting. Kubrick used the technique to produce the backdrops in the Africa scenes and the scene when astronauts walk on the Moon. The technique consisted of a separate scenery projector set at a right angle to the camera and a half-silvered mirror placed at an angle in front that reflected the projected image forward in line with the camera lens onto a backdrop of retroreflective material. The reflective directional screen behind the actors could reflect light from the projected image 100 times more efficiently than the foreground subject did. The lighting of the foreground subject had to be balanced with the image from the screen, so that the part of the scenery image that fell on the foreground subject was too faint to show on the finished film. The exception was the eyes of the leopard in the "Dawn of Man" sequence, which glowed due to the projector illumination. Kubrick described this as "a happy accident". Front projection had been used in smaller settings before ''2001'', mostly for still photography or television production, using small still images and projectors. The expansive backdrops for the African scenes required a screen tall and wide, far larger than had been used before. When the reflective material was applied to the backdrop in strips, variations at the seams of the strips led to visual artefacts; to solve this, the crew tore the material into smaller chunks and applied them in a random "camouflage" pattern on the backdrop. The existing projectors using transparencies resulted in grainy images when projected that large, so the crew worked with MGM's special-effects supervisor Tom Howard (special effects), Tom Howard to build a custom projector using transparencies, which required the largest water-cooled arc lamp available. The technique was used widely in the film industry thereafter until it was replaced by Chroma key, blue/green screen systems in the 1990s.Soundtrack

The initial MGM soundtrack album release contained none of the material from the altered and uncredited rendition of Ligeti's ''Aventures'' used in the film, used a different recording of ''Also sprach Zarathustra'' (performed by the Berlin Philharmonic conducted by Karl Böhm) from that heard in the film, and a longer excerpt of ''Lux Aeterna (Ligeti), Lux Aeterna'' than that in the film. In 1996, Turner Entertainment/Rhino Records released a new soundtrack on CD that included the film's rendition of "Aventures", the version of "Zarathustra" used in the film, and the shorter version of ''Lux Aeterna'' from the film. As additional "bonus tracks" at the end, the CD includes the versions of "Zarathustra" and ''Lux Aeterna'' on the old MGM soundtrack album, an unaltered performance of "Aventures", and a nine-minute compilation of all of HAL's dialogue. Alex North's unused music was first released in Telarc's issue of the main theme on ''Hollywood's Greatest Hits, Vol. 2'', a compilation album by Erich Kunzel and the Cincinnati Pops Orchestra. All of the music North originally wrote was recorded commercially by his friend and colleague Jerry Goldsmith with the National Philharmonic Orchestra and released on Varèse Sarabande CDs shortly after Telarc's first theme release and before North's death. Eventually, a mono mix-down of North's original recordings was released as a limited-edition CD by Intrada Records.Theatrical run and post-premiere cuts