1964 New York World’s Fair on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The 1964–1965 New York World's Fair was a

"The World's Fair: It was a disaster from the beginning

. ''American Heritage''. The fair ran for two six-month seasons, April 22 – October 18, 1964, and April 21 – October 17, 1965. Admission price for adults (13 and older) was $2.00 in 1964 ( after calculating for inflation). Admission in 1965 increased to $2.50 ( after calculating for inflation). In both years, children (2–12) admission cost $1.00 ( after calculating for inflation). The fair is noted as a showcase of mid-twentieth-century American culture and technology. The nascent

Reprint

This articles includes a full list of the original members of the Fair committee, mostly corporate and union leaders. Then-New York City mayor,

The BIE withholding official recognition was a serious handicap for fair promoters. The absence of Canada, Australia, most of the major European nations, and the

The BIE withholding official recognition was a serious handicap for fair promoters. The absence of Canada, Australia, most of the major European nations, and the  One of the fair's most popular exhibits was the Vatican Pavilion, which featured

One of the fair's most popular exhibits was the Vatican Pavilion, which featured  Emerging African nations displayed their wares in the Africa Pavilion. Controversy broke out when the

Emerging African nations displayed their wares in the Africa Pavilion. Controversy broke out when the

A United States Space Park was sponsored by

A United States Space Park was sponsored by

Industries played a major role at the New York World's Fair of 1939–1940 by hosting huge, elaborate exhibits. Many of them returned to the New York World's Fair of 1964–1965 with even more elaborate versions of the shows that they had presented 25 years earlier. The most notable of these was

Industries played a major role at the New York World's Fair of 1939–1940 by hosting huge, elaborate exhibits. Many of them returned to the New York World's Fair of 1964–1965 with even more elaborate versions of the shows that they had presented 25 years earlier. The most notable of these was

The

The

(2)

(3) They also contained a "space age" gas station with orbiting gas pumps shaped like rockets, and a marine fuel station in the vicinity of the World's Fair Marina.

. ''The 70mm Newsletter''. The 13-½ minute film ''

The fair is remembered as the venue that

The fair is remembered as the venue that

One of the fair's major crowd-attracting and financial shortcomings was the absence of a midway. The fair's organizers were opposed on principle to the

One of the fair's major crowd-attracting and financial shortcomings was the absence of a midway. The fair's organizers were opposed on principle to the

''Time'' Some spectacles were staged for the newsreel cameras, such as a May 1964 demonstration by Bell Aerosystems where

New York City was left with a much-improved Flushing Meadows–Corona Park following the fair, taking possession of the park from the Fair Corporation in June 1967. Today, the paths and their names remain almost unchanged from the days of the fair.

The Unisphere stands at the center of the park as a symbol of "Man's Achievements on a Shrinking Globe in an Expanding Universe". The Unisphere has become the iconic sculptural feature of the park, as well as a symbol of the borough of

New York City was left with a much-improved Flushing Meadows–Corona Park following the fair, taking possession of the park from the Fair Corporation in June 1967. Today, the paths and their names remain almost unchanged from the days of the fair.

The Unisphere stands at the center of the park as a symbol of "Man's Achievements on a Shrinking Globe in an Expanding Universe". The Unisphere has become the iconic sculptural feature of the park, as well as a symbol of the borough of  The

The

Like its 1939 predecessor, the 1964 World's Fair lost money. It was unable to repay its financial backers their investment, and it became embroiled in legal disputes with its creditors until 1970, when the books were finally closed and the Fair Corporation was dissolved. Most of the pavilions constructed for the fair were demolished within six months following the fair's close. While only a handful of pavilions and exhibits survived, some of them traveled great distances and found new homes following the fair:

* The Austria pavilion became a

Like its 1939 predecessor, the 1964 World's Fair lost money. It was unable to repay its financial backers their investment, and it became embroiled in legal disputes with its creditors until 1970, when the books were finally closed and the Fair Corporation was dissolved. Most of the pavilions constructed for the fair were demolished within six months following the fair's close. While only a handful of pavilions and exhibits survived, some of them traveled great distances and found new homes following the fair:

* The Austria pavilion became a

*

*

After the Fair

',

Peace Through Understanding: The 1964/65 New York World's Fair

', and

Modern Ruin: A World’s Fair Pavilion

'. * The first ''

File:Westinghouse replicas Sep 65.jpg, Westinghouse Time Capsule

File:RCA Pavilion.jpg, RCA Pavilion

File:Johnson Wax Pavilion.jpg, Johnson Wax Pavilion

File:Kodak Pavilion.jpg, Kodak Pavilion

File:Ford Pavilion.jpg, Ford Pavilion

File:Transportation & Travel Pavilion.jpg, Transportation and Travel Pavilion

File:Alaska Pavilion.jpg, Alaska Pavilion

File:Hong Kong Pavilion.jpg, Hong Kong Pavilion

File:Underground World Home exhibit.png, Underground World Home exhibit

File:FlushingMeadowNY HallofScience exterior.jpg, The Hall of Science is a science museum today

File:1964 New York World Fair Stamp.jpg, 19641965 New York World's Fair US postage stamp

File:1964 New York Worlds Fair Ashtray.jpg, Souvenir ashtray

The World's Fair: It was a disaster from the beginning

, ''American Heritage'' Magazine, October 2006, Volume 57, Issue 5.

The website of the 1964/1965 New York World's Fair - nywf64.com

New York State Pavilion Project

New York 1964–1965 World's Fair

{{Authority control Flushing Meadows–Corona Park 1960s in Queens Robert Moses projects 1964 in New York City 1964 in science Futurism 1965 in New York City New York (state) historical anniversaries

world's fair

A world's fair, also known as a universal exhibition or an expo, is a large international exhibition designed to showcase the achievements of nations. These exhibitions vary in character and are held in different parts of the world at a specif ...

that held over 140 pavilions and 110 restaurants, representing 80 nations (hosted by 37), 24 US states

In the United States, a state is a constituent political entity, of which there are 50. Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its sover ...

, and over 45 corporations with the goal and the final result of building exhibits or attractions at Flushing Meadows–Corona Park

Flushing Meadows–Corona Park, often referred to as Flushing Meadows Park, or simply Flushing Meadows, is a public park in the northern part of Queens, New York City. It is bounded by I-678 (Van Wyck Expressway) on the east, Grand Central Par ...

in Queens

Queens is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Queens County, in the U.S. state of New York. Located on Long Island, it is the largest New York City borough by area. It is bordered by the borough of Brooklyn at the western tip of Long ...

, New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

. The immense fair covered on half the park, with numerous pools or fountains, and an amusement park with rides near the lake. However, the fair did not receive official support or approval from the Bureau of International Expositions

The Bureau international des expositions (BIE; English: International Bureau of Expositions) is an intergovernmental organization created to supervise international exhibitions (also known as expos or world expos) falling under the jurisdiction o ...

(BIE).

Hailing itself as a "universal and international" exposition, the fair's theme was "Peace Through Understanding", dedicated to "Man's Achievement on a Shrinking Globe in an Expanding Universe". American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

companies dominated the exposition as exhibitors. The theme was symbolized by a 12-story-high, stainless-steel model of the Earth called the Unisphere

The Unisphere is a spherical stainless steel representation of the Earth in Flushing Meadows–Corona Park in the New York City borough of Queens. The globe was designed by Gilmore D. Clarke as part of his plan for the 1964 New York World's ...

, built on the foundation of the Perisphere

The Trylon and Perisphere were two monumental modernistic structures designed by architects Wallace Harrison and J. Andre Fouilhoux that were together known as the Theme Center of the 1939 New York World's Fair. The Perisphere was a tremendous ...

from the 1939 World's Fair

The 1939–40 New York World's Fair was a world's fair held at Flushing Meadows–Corona Park in Queens, New York, United States. It was the second-most expensive American world's fair of all time, exceeded only by St. Louis's Louisiana Purcha ...

.Gordon, John Steele (October 2006)."The World's Fair: It was a disaster from the beginning

. ''American Heritage''. The fair ran for two six-month seasons, April 22 – October 18, 1964, and April 21 – October 17, 1965. Admission price for adults (13 and older) was $2.00 in 1964 ( after calculating for inflation). Admission in 1965 increased to $2.50 ( after calculating for inflation). In both years, children (2–12) admission cost $1.00 ( after calculating for inflation). The fair is noted as a showcase of mid-twentieth-century American culture and technology. The nascent

Space Age

The Space Age is a period encompassing the activities related to the Space Race, space exploration, space technology, and the cultural developments influenced by these events, beginning with the Sputnik_1#Launch_and_mission, launch of Sputnik 1 ...

, with its vista of promise, was well represented. More than 51 million people attended the fair, though fewer than the hoped-for 70 million. It remains a touchstone for many American Baby Boomers

Baby boomers, often shortened to boomers, are the Western demographic cohort following the Silent Generation and preceding Generation X. The generation is often defined as people born from 1946 to 1964, during the mid-20th century baby boom. Th ...

who visited the optimistic exposition as children, before the turbulent years of the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

and many to be forthcoming cultural changes.

In many ways the fair symbolized a grand consumer show, covering many products then-produced in America for transportation, living, and consumer electronic needs in a way that would never be repeated at future world's fairs in North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

. American manufacturers of pens, chemicals, computers, and automobiles had a major presence. This fair gave many attendees their first interaction with computer equipment. Corporations demonstrated the use of mainframe computer

A mainframe computer, informally called a mainframe or big iron, is a computer used primarily by large organizations for critical applications like bulk data processing for tasks such as censuses, industry and consumer statistics, enterpris ...

s, computer terminal

A computer terminal is an electronic or electromechanical hardware device that can be used for entering data into, and transcribing data from, a computer or a computing system. The teletype was an example of an early-day hard-copy terminal and ...

s with keyboards and CRT display

CRT or Crt may refer to:

Science, technology, and mathematics Medicine and biology

* Calreticulin, a protein

* Capillary refill time, for blood to refill capillaries

* Cardiac resynchronization therapy and CRT defibrillator (CRT-D)

* Catheter- ...

s, teletype

A teleprinter (teletypewriter, teletype or TTY) is an electromechanical device that can be used to send and receive typed messages through various communications channels, in both point-to-point and point-to-multipoint configurations. Initia ...

machines, punch card

A punched card (also punch card or punched-card) is a piece of stiff paper that holds digital data represented by the presence or absence of holes in predefined positions. Punched cards were once common in data processing applications or to di ...

s, and telephone modem

A modulator-demodulator or modem is a computer hardware device that converts data from a digital format into a format suitable for an analog transmission medium such as telephone or radio. A modem transmits data by modulating one or more ca ...

s in an era when computer equipment was kept in back offices away from the public, decades before the Internet and home computers were at everyone's disposal.

Site history

The selected site,Flushing Meadows–Corona Park

Flushing Meadows–Corona Park, often referred to as Flushing Meadows Park, or simply Flushing Meadows, is a public park in the northern part of Queens, New York City. It is bounded by I-678 (Van Wyck Expressway) on the east, Grand Central Par ...

in the borough

A borough is an administrative division in various English-speaking countries. In principle, the term ''borough'' designates a self-governing walled town, although in practice, official use of the term varies widely.

History

In the Middle Ag ...

of Queens

Queens is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Queens County, in the U.S. state of New York. Located on Long Island, it is the largest New York City borough by area. It is bordered by the borough of Brooklyn at the western tip of Long ...

, was originally a natural wetland straddling the Flushing River

The Flushing River, also known as Flushing Creek, is a waterway that flows northward through the borough of Queens in New York City, mostly within Flushing Meadows–Corona Park, emptying into the Flushing Bay and the East River. The river run ...

. Flushing

Flushing may refer to:

Places

* Flushing, Cornwall, a village in the United Kingdom

* Flushing, Queens, New York City

** Flushing Bay, a bay off the north shore of Queens

** Flushing Chinatown (法拉盛華埠), a community in Queens

** Flushing ...

had been a Dutch settlement, named after the city of Vlissingen

Vlissingen (; zea, label=Zeelandic, Vlissienge), historically known in English as Flushing, is a Municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality and a city in the southwestern Netherlands on the former island of Walcheren. With its strategic l ...

(anglicized into "Flushing"). The site was then converted into the Corona Ash Dumps, which were featured prominently in F. Scott Fitzgerald

Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald (September 24, 1896 – December 21, 1940) was an American novelist, essayist, and short story writer. He is best known for his novels depicting the flamboyance and excess of the Jazz Age—a term he popularize ...

's ''The Great Gatsby

''The Great Gatsby'' is a 1925 novel by American writer F. Scott Fitzgerald. Set in the Jazz Age on Long Island, near New York City, the novel depicts First-person narrative, first-person narrator Nick Carraway's interactions with mysterious mil ...

'' as the "Valley of Ashes". The site was used for the 1939-1940 New York World's Fair, and at the conclusion of the fair, was used as a park.

Preceding these fairs was the 1853–1854 Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations

The Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations was a World's Fair held in 1853 in what is now Bryant Park in New York City, in the wake of the highly successful 1851 Great Exhibition in London. It aimed to showcase the new industrial achievements ...

, located in the New York Crystal Palace

New York Crystal Palace was an exhibition building constructed for the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations in New York City in 1853, which was under the presidency of the mayor Jacob Aaron Westervelt. The building stood in Reservoir Squar ...

at what is now Bryant Park

Bryant Park is a public park located in the New York City borough of Manhattan. Privately managed, it is located between Fifth Avenue and Avenue of the Americas ( Sixth Avenue) and between 40th and 42nd Streets in Midtown Manhattan. The e ...

in the New York City borough of Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

.

Beginnings

The 1964–1965 Fair was conceived by a group of New York businessmen who remembered their childhood experiences at the1939 New York World's Fair

The 1939–40 New York World's Fair was a world's fair held at Flushing Meadows–Corona Park in Queens, New York, United States. It was the second-most expensive American world's fair of all time, exceeded only by St. Louis's Louisiana Purchas ...

. Thoughts of an economic boon to the city as the result of increased tourism was a major reason for holding another fair 25 years after the 1939–1940 extravaganza.Reprint

This articles includes a full list of the original members of the Fair committee, mostly corporate and union leaders. Then-New York City mayor,

Robert F. Wagner, Jr.

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, honou ...

, commissioned Frederick Pittera, a producer of international fairs and exhibitions, and author of the history of International Fairs & Exhibitions for the ''Encyclopædia Britannica

The (Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various time ...

'' and ''Compton's Encyclopedia

''Compton's Encyclopedia and Fact-Index'' is a home and school encyclopedia first published in 1922 as ''Compton's Pictured Encyclopedia''. The word "Pictured" was removed from the title with the 1968 edition.Encyclopædia Britannica, 1988. The en ...

'', to prepare the first feasibility studies for the 1964–1965 New York World's Fair. He was joined by Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

n architect Victor Gruen

Victor David Gruen, born Viktor David Grünbaum

retrieved 25 February 2012 (July 18, 1903 – February 1 ...

(creator of the shopping mall) in studies that eventually led the Eisenhower Commission to award the world's fair to New York City in competition with a number of American cities.

The year 1964 was nominally selected for the event to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the naming of New York, after King Charles II sent an English fleet to seize it from the Dutch in 1664. Prince James (the Duke of York) then renamed the former Dutch colony New Amsterdam as New York.

Organizers turned to private financing and the sale of bonds to pay the huge costs to stage the event. The organizers hired New York's "Master Builder" retrieved 25 February 2012 (July 18, 1903 – February 1 ...

Robert Moses

Robert Moses (December 18, 1888 – July 29, 1981) was an American urban planner and public official who worked in the New York metropolitan area during the early to mid 20th century. Despite never being elected to any office, Moses is regarded ...

, to head the corporation established to run the fair because he was experienced in raising money for vast public projects. Moses had been a formidable figure in the city since coming to power in the 1930s. He was responsible for the construction of much of the city's highway infrastructure and, as parks commissioner for decades, the creation of much of the city's park system.

In the mid-1930s, Moses oversaw the conversion of a vast Queens tidal marsh

A tidal marsh (also known as a type of "tidal wetland") is a marsh found along rivers, coasts and estuaries which floods and drains by the tidal movement of the adjacent estuary, sea or ocean. Tidal marshes are commonly zoned into lower marshes ( ...

garbage dump into the fairgrounds that hosted the 1939–1940 World's Fair. Called Flushing Meadows Park

Flushing may refer to:

Places

* Flushing, Cornwall, a village in the United Kingdom

* Flushing, Queens, New York City

** Flushing Bay, a bay off the north shore of Queens

** Flushing Chinatown (法拉盛華埠), a community in Queens

** Flushing ...

, it was Moses' grandest park scheme. He envisioned this vast park, comprising some of land, easily accessible from Manhattan, as a major recreational playground for New Yorkers. When the 1939–1940 World's Fair ended in financial failure, Moses did not have the available funds to complete work on his project. He saw the 1964–1965 Fair as a means to finish what the earlier fair had begun.

To ensure profits to complete the park, fair organizers knew they would have to maximize receipts. An estimated attendance of 70 million people would be needed to turn a profit and, for attendance that large, the fair would need to be held for two years. The World's Fair Corporation also decided to charge site-rental fees to all exhibitors who wished to construct pavilions on the grounds. This decision caused the fair to come into conflict with the Bureau of International Expositions

The Bureau international des expositions (BIE; English: International Bureau of Expositions) is an intergovernmental organization created to supervise international exhibitions (also known as expos or world expos) falling under the jurisdiction o ...

(BIE), as the international body headquartered in Paris that sanctions world's fairs: BIE rules stated that an international exposition could run for one six-month period only, and no rent could be charged to exhibitors. In addition, the rules allowed only one exposition in any given country within a 10-year period, and the Seattle World's Fair

The Century 21 Exposition (also known as the Seattle World's Fair) was a world's fair held April 21, 1962, to October 21, 1962, in Seattle, Washington (state), Washington, United States.Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

to seek official approval for the New York fair. When the BIE balked at New York's bid, Moses, used to having his way in New York, angered the BIE delegates by taking his case to the press, publicly stating his disdain for the BIE and its rules. The BIE retaliated by formally requesting its member nations ''not'' to participate in the New York fair. The 1964–1965 New York World's Fair is the only significant world's fair since the formation of the BIE to be held without its endorsement.

Architecture

Many of the pavilions were built in a Mid-century modern style that was heavily influenced by "Googie architecture

Googie architecture ( ) is a type of futurist architecture influenced by car culture, Jet aircraft, jets, the Atomic Age and the Space Age. It originated in Southern California from the Streamline Moderne architecture of the 1930s, and was pop ...

". This was a futurist architectural style influenced by car culture

Since the start of the twentieth century, the role of cars has become highly important, though controversial. They are used throughout the world and have become the most popular mode of transport in many of the more developed countries. In deve ...

, jet aircraft

A jet aircraft (or simply jet) is an aircraft (nearly always a fixed-wing aircraft) propelled by jet engines.

Whereas the engines in propeller-powered aircraft generally achieve their maximum efficiency at much lower speeds and altitudes, je ...

, the Space Age

The Space Age is a period encompassing the activities related to the Space Race, space exploration, space technology, and the cultural developments influenced by these events, beginning with the Sputnik_1#Launch_and_mission, launch of Sputnik 1 ...

, and the Atomic Age

The Atomic Age, also known as the Atomic Era, is the period of history following the detonation of the first nuclear weapon, The Gadget at the ''Trinity'' test in New Mexico, on July 16, 1945, during World War II. Although nuclear chain reaction ...

, which were all on display at the fair. Some pavilions were explicitly shaped like the product they were promoting, such as the US Royal tire-shaped Ferris wheel, or even the corporate logo

A logo (abbreviation of logotype; ) is a graphic mark, emblem, or symbol used to aid and promote public identification and recognition. It may be of an abstract or figurative design or include the text of the name it represents as in a wordm ...

, such as the Johnson Wax

S. C. Johnson & Son, Inc. (commonly referred to as S. C. Johnson) is an American multinational, privately held manufacturer of household cleaning supplies and other consumer chemicals based in Racine, Wisconsin. In 2017, S. C. Jo ...

pavilion. Other pavilions were more abstract representations, such as the oblate spheroid

A spheroid, also known as an ellipsoid of revolution or rotational ellipsoid, is a quadric surface obtained by rotating an ellipse about one of its principal axes; in other words, an ellipsoid with two equal semi-diameters. A spheroid has circ ...

-shaped IBM pavilion, or the General Electric

General Electric Company (GE) is an American multinational conglomerate founded in 1892, and incorporated in New York state and headquartered in Boston. The company operated in sectors including healthcare, aviation, power, renewable energ ...

circular dome shaped "Carousel of Progress

Walt Disney's Carousel of Progress is a rotating theater audio-animatronic stage show attraction in Tomorrowland at the Magic Kingdom theme park at the Walt Disney World Resort in Bay Lake, Florida just outside of Orlando, Florida. Created ...

".

The pavilion architectures expressed a new-found freedom of form enabled by modern building materials, such as reinforced concrete

Reinforced concrete (RC), also called reinforced cement concrete (RCC) and ferroconcrete, is a composite material in which concrete's relatively low tensile strength and ductility are compensated for by the inclusion of reinforcement having hig ...

, fiberglass

Fiberglass (American English) or fibreglass (Commonwealth English) is a common type of fiber-reinforced plastic using glass fiber. The fibers may be randomly arranged, flattened into a sheet called a chopped strand mat, or woven into glass cloth ...

, plastic

Plastics are a wide range of synthetic or semi-synthetic materials that use polymers as a main ingredient. Their plasticity makes it possible for plastics to be moulded, extruded or pressed into solid objects of various shapes. This adaptab ...

, tempered glass

Tempered or toughened glass is a type of safety glass processed by controlled thermal or chemical treatments to increase its strength compared with normal glass. Tempering puts the outer surfaces into compression and the interior into tension. ...

, and stainless steel

Stainless steel is an alloy of iron that is resistant to rusting and corrosion. It contains at least 11% chromium and may contain elements such as carbon, other nonmetals and metals to obtain other desired properties. Stainless steel's corros ...

. The facade or the entire structure of a pavilion served as a giant billboard

A billboard (also called a hoarding in the UK and many other parts of the world) is a large outdoor advertising structure (a billing board), typically found in high-traffic areas such as alongside busy roads. Billboards present large advertise ...

advertising the country or organization housed inside, flamboyantly competing for the attention of busy and distracted fairgoers.

By contrast, some of the smaller international, US state, and organizational pavilions were built in more traditional styles, such as a Chinese temple

Chinese temple architecture refer to a type of structures used as place of worship of Chinese Buddhism, Taoism or Chinese folk religion, where people revere ethnic Chinese gods and ancestors. They can be classified as:

* '' miào'' () or ''di� ...

or a Swiss chalet

A chalet (pronounced in British English; in American English usually ), also called Swiss chalet, is a type of building or house, typical of the Alpine region in Europe. It is made of wood, with a heavy, gently sloping roof and wide, well-suppo ...

. Countries took this opportunity to showcase culinary aspects of their culture as well, with fondue being promoted at the Swiss Pavilion's Alpine restaurant thanks to the Swiss Cheese Union

The Swiss Cheese Union (german: Schweizer Käseunion AG, ) was a marketing and trading organization in Switzerland, which from 1914 to 1999 served as a cartel to control cheese production. To this end, the Swiss Cheese Union mandated production be ...

. After the fair's final closing in 1965, some pavilions crafted of wood were carefully disassembled and transported elsewhere for re-use.

Other pavilions were "decorated sheds", a building method later described by Robert Venturi

Robert Charles Venturi Jr. (June 25, 1925 – September 18, 2018) was an American architect, founding principal of the firm Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, and one of the major architectural figures of the twentieth century.

Together with h ...

and Denise Scott Brown

Denise Scott Brown (née Lakofski; born October 3, 1931) is an American architect, planner, writer, educator, and principal of the firm Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates in Philadelphia. Scott Brown and her husband and partner, Robert Venturi, ...

, using plain structural shells embellished with applied decorations. This allowed designers to simulate a traditional style while bypassing expensive and time-consuming methods of traditional construction. The expedient was considered acceptable for temporary buildings planned to be used for only two years, and then to be demolished.

The Underground World Home which was designed by architect Jay Swayze was also featured at the fair. Fairgoers could tour the home for the price of one dollar. It was a large underground bunker-home and it was unveiled in response to the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

. The home had ten rooms and and was entirely underground. It featured air conditioning and backlit murals to create the illusion of the outdoor lighting. The murals were hand painted by Mrs. Glenn Smith.

International participation

The BIE withholding official recognition was a serious handicap for fair promoters. The absence of Canada, Australia, most of the major European nations, and the

The BIE withholding official recognition was a serious handicap for fair promoters. The absence of Canada, Australia, most of the major European nations, and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, all members of the BIE, tarnished the image of the fair. Additionally, New York was forced to compete with both Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest regio ...

and Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-most populous city in Canada and List of towns in Quebec, most populous city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian ...

for international participants, with many nations choosing the officially-sanctioned world's fairs of those other North American cities over the New York Fair. The promoters turned to trade and tourism organizations within many countries to sponsor national exhibits in lieu of official government sponsorship of pavilions.

New York City, in the middle of the twentieth century, was at a zenith of economic power and world prestige. Unconcerned by BIE rules, nations with smaller economies (as well as private groups in (or relevant to) some BIE members) saw it as an honor to host an exhibit at the Fair. Therefore, smaller nations made up the majority of the international participation. Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

, Vatican City

Vatican City (), officially the Vatican City State ( it, Stato della Città del Vaticano; la, Status Civitatis Vaticanae),—'

* german: Vatikanstadt, cf. '—' (in Austria: ')

* pl, Miasto Watykańskie, cf. '—'

* pt, Cidade do Vati ...

, Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeast ...

, Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

, Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

, Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

, Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark

...

, Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is bo ...

, Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

, and Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

, and Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

to name some, hosted national presences at the Fair. Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guine ...

sponsored a pavilion, but relations deteriorated rapidly between that nation and the US during 1964, fueled by anti-Western and anti-American rhetoric and policies by Indonesian president Sukarno

Sukarno). (; born Koesno Sosrodihardjo, ; 6 June 1901 – 21 June 1970) was an Indonesian statesman, orator, revolutionary, and nationalist who was the first president of Indonesia, serving from 1945 to 1967.

Sukarno was the leader of ...

, which angered US President Lyndon Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

. Indonesia withdrew from the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

in January 1965, and officially from the Fair in March. The Fair Corporation then seized and shut down the Indonesian pavilion, and it remained closed and barricaded for the 1965 season.

One of the fair's most popular exhibits was the Vatican Pavilion, which featured

One of the fair's most popular exhibits was the Vatican Pavilion, which featured Michelangelo

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (; 6 March 1475 – 18 February 1564), known as Michelangelo (), was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet of the High Renaissance. Born in the Republic of Florence, his work was insp ...

's ''Pietà

The Pietà (; meaning "pity", "compassion") is a subject in Christian art depicting the Virgin Mary cradling the dead body of Jesus after his body was removed from the cross. It is most often found in sculpture. The Pietà is a specific form o ...

'', brought in from St. Peter's Basilica

The Papal Basilica of Saint Peter in the Vatican ( it, Basilica Papale di San Pietro in Vaticano), or simply Saint Peter's Basilica ( la, Basilica Sancti Petri), is a church built in the Renaissance style located in Vatican City, the papal e ...

with the permission of Pope John XXIII

Pope John XXIII ( la, Ioannes XXIII; it, Giovanni XXIII; born Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli, ; 25 November 18813 June 1963) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 28 October 1958 until his death in June 19 ...

; today, a small plaza and exedra

An exedra (plural: exedras or exedrae) is a semicircular architectural recess or platform, sometimes crowned by a semi-dome, and either set into a building's façade or free-standing. The original Greek sense (''ἐξέδρα'', a seat out of d ...

monument mark the spot (and Pope Paul VI

Pope Paul VI ( la, Paulus VI; it, Paolo VI; born Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini, ; 26 September 18976 August 1978) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City, Vatican City State from 21 June 1963 to his ...

's visit in October 1965). People waited in line for hours to view the Michelangelo sculpture; a novel conveyor belt

A conveyor belt is the carrying medium of a belt conveyor system (often shortened to belt conveyor). A belt conveyor system is one of many types of conveyor systems. A belt conveyor system consists of two or more pulleys (sometimes referred to ...

system was used to move them through the viewing in an orderly fashion. A modern replica of the artwork had been transported beforehand to ensure that the statue could be installed without being damaged. The copy is now on view in the Immaculate Conception Seminary in Douglaston, Queens, New York. The exedra monument is now used with permits since 1975 for prayer vigils by Our Lady of the Roses relocated from Bayside, New York.

A recreation of a medieval Belgian

Belgian may refer to:

* Something of, or related to, Belgium

* Belgians, people from Belgium or of Belgian descent

* Languages of Belgium, languages spoken in Belgium, such as Dutch, French, and German

*Ancient Belgian language, an extinct languag ...

village proved very popular. Fairgoers were treated to the "Bel-Gem Brussels Waffle"—a combination of waffle

A waffle is a dish made from leavened batter or dough that is cooked between two plates that are patterned to give a characteristic size, shape, and surface impression. There are many variations based on the type of waffle iron and recipe used ...

, strawberries and whipped cream, sold by a Brussels couple, Maurice Vermersch and his wife.

Fairgoers could also enjoy sampling sandwiches from around the world at the popular 7-Up International Sandwich Garden Pavilion which featured the innovative fiberglass Seven Up

7 Up (stylized as 7up outside North America) is an American brand of lemon-lime-flavored non-caffeinated soft drink. The brand and formula are owned by Keurig Dr Pepper although the beverage is internationally distributed by PepsiCo. 7 Up comp ...

Tower. In addition to all the 7-Up beverages one could drink, fair-goers were invited to sample varied culinary delights representing sixteen countries. While dining, visitors enjoyed live performances on four circular stages from various instrumentalists which included a five piece musical ensemble, the 7-Up Continental Band. The musical programs included popular show tunes from the Broadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

**Broadway Theatre (53rd Stree ...

stage in America, as well as musical favorites from both Europe and Latin America. The soloist John Serry Sr.

John Serry Sr. (born John Serrapica; January 29, 1915 – September 14, 2003) was an American concert accordionist, arranger, composer, organist, and educator. He performed on the CBS Radio and Television networks and contributed to Voic ...

appeared regularly with the orchestra to complement the international flavor of the musical program. The dining pods featured furnishings designed by the futuristic Finnish-American architect Eero Saarinen

Eero Saarinen (, ; August 20, 1910 – September 1, 1961) was a Finnish-American architect and industrial designer noted for his wide-ranging array of designs for buildings and monuments. Saarinen is best known for designing the General Motors ...

and were enclosed by twenty-four futuristic fiberglass domes that were topped by a commanding clock tower that soared more than above the entire pavilion.

Emerging African nations displayed their wares in the Africa Pavilion. Controversy broke out when the

Emerging African nations displayed their wares in the Africa Pavilion. Controversy broke out when the Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

ian pavilion displayed a mural emphasizing the plight of the Palestinian people

Palestinians ( ar, الفلسطينيون, ; he, פָלַסְטִינִים, ) or Palestinian people ( ar, الشعب الفلسطيني, label=none, ), also referred to as Palestinian Arabs ( ar, الفلسطينيين العرب, label=non ...

. The Jordanians also donated an ancient column which still remains at the former fair site.

The city of West Berlin

West Berlin (german: Berlin (West) or , ) was a political enclave which comprised the western part of Berlin during the years of the Cold War. Although West Berlin was de jure not part of West Germany, lacked any sovereignty, and was under mi ...

, a Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

hot-spot, hosted a popular exhibit in a pavilion that was designed by Hans Wehrhahn.

On April 21, 1965, as part of the opening ceremonies for the second season of the 1964–1965 New York World's Fair, Ethiopian long-distance runners Abebe Bikila

''Shambel'' Abebe Bikila ( am, ሻምበል አበበ ቢቂላ; August 7, 1932 – October 25, 1973) was an Ethiopian marathon runner who was a back-to-back Olympic marathon champion. He is the first Ethiopian Olympic gold medalist, winnin ...

and Mamo Wolde

Degaga "Mamo" Wolde ( amh, ማሞ ወልዴ; 12 June 1932 – 26 May 2002) was an Ethiopian long distance runner who competed in track, cross-country, and road running events. He was the winner of the marathon at the 1968 Summer Olympics.

...

participated in an exclusive ceremonial half marathon. They ran from the Arsenal

An arsenal is a place where arms and ammunition are made, maintained and repaired, stored, or issued, in any combination, whether privately or publicly owned. Arsenal and armoury (British English) or armory (American English) are mostly ...

in Central Park

Central Park is an urban park in New York City located between the Upper West Side, Upper West and Upper East Sides of Manhattan. It is the List of New York City parks, fifth-largest park in the city, covering . It is the most visited urban par ...

at 64th Street & Fifth Avenue

Fifth Avenue is a major and prominent thoroughfare in the borough of Manhattan in New York City. It stretches north from Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village to West 143rd Street in Harlem. It is one of the most expensive shopping stre ...

in Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

to the Singer Bowl

The Singer Bowl was the former name for a stadium in the northeastern United States, located in Flushing Meadows–Corona Park in the New York City borough of Queens. It was an early example of naming rights in large venues.

History

The sta ...

at the fair. They carried with them a parchment scroll with greetings from Haile Selassie

Haile Selassie I ( gez, ቀዳማዊ ኀይለ ሥላሴ, Qädamawi Häylä Səllasé, ; born Tafari Makonnen; 23 July 189227 August 1975) was Emperor of Ethiopia from 1930 to 1974. He rose to power as Regent Plenipotentiary of Ethiopia (' ...

.

Federal and state exhibits

United States Pavilion

The United States Pavilion was titled "Challenge to Greatness", and focused on PresidentLyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

's "Great Society

The Great Society was a set of domestic programs in the United States launched by Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964–65. The term was first coined during a 1964 commencement address by President Lyndon B. Johnson at the University ...

" proposals. The main show in the multimillion-dollar pavilion was a 15-minute ride through a filmed presentation of American history. Visitors seated in moving grandstands rode past movie screens that slid in, out, and above the path of the traveling audience.

Elsewhere, there were tributes to the late President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

, who had broken ground for the pavilion in December 1962 but had been assassinated in November 1963 before the fair opened.

A painting of the Belgian artist Luc-Peter Crombé

Luc-Peter Crombé (14 January 1920 – 17 May 2005) was a Belgian, Flemish painter.

Luc-Peter Crombé was painter of landscapes, portraits, figures and religious subjects. He was part of the so-called 4th School of Latem of Flemish art and was k ...

received the main award of the jury. It is a semi-religious presentation of three young men challenging flames.

United States Space Park

A United States Space Park was sponsored by

A United States Space Park was sponsored by NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeeding t ...

, the Department of Defense Department of Defence or Department of Defense may refer to:

Current departments of defence

* Department of Defence (Australia)

* Department of National Defence (Canada)

* Department of Defence (Ireland)

* Department of National Defense (Philipp ...

and the fair. Exhibits included a full-scale model of the aft skirt and five F-1 engines of the first stage of a Saturn V

Saturn V is a retired American super heavy-lift launch vehicle developed by NASA under the Apollo program for human exploration of the Moon. The rocket was human-rated, with multistage rocket, three stages, and powered with liquid-propellant r ...

, a Titan II

The Titan II was an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) developed by the Glenn L. Martin Company from the earlier Titan I missile. Titan II was originally designed and used as an ICBM, but was later adapted as a medium-lift space l ...

booster with a Gemini

Gemini may refer to:

Space

* Gemini (constellation), one of the constellations of the zodiac

** Gemini in Chinese astronomy

* Project Gemini, the second U.S. crewed spaceflight program

* Gemini Observatory, consisting of telescopes in the Northern ...

capsule, an Atlas with a Mercury

Mercury commonly refers to:

* Mercury (planet), the nearest planet to the Sun

* Mercury (element), a metallic chemical element with the symbol Hg

* Mercury (mythology), a Roman god

Mercury or The Mercury may also refer to:

Companies

* Merc ...

capsule and a Thor-Delta

The Thor-Delta, also known as Delta DM-19 or just Delta was an early American expendable launch system used for 12 orbital launches in the early 1960s. A derivative of the Thor-Able, it was a member of the Thor family of rockets, and the first ...

rocket. On display at ground level were ''Aurora 7

Mercury-Atlas 7, launched May 24, 1962, was the fourth crewed flight of Project Mercury. The spacecraft, named ''Aurora 7'', was piloted by astronaut Scott Carpenter. He was the sixth human to fly in space. The mission used Mercury spacecraft No ...

'', the Mercury capsule flown by Scott Carpenter

Malcolm Scott Carpenter (May 1, 1925 – October 10, 2013) was an American naval officer and aviator, test pilot, aeronautical engineer, astronaut, and aquanaut. He was one of the Mercury Seven astronauts selected for NASA's Project Mercury ...

on the second US crewed orbital flight; full-scale models of an X-15

The North American X-15 is a hypersonic rocket-powered aircraft. It was operated by the United States Air Force and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration as part of the X-plane series of experimental aircraft. The X-15 set speed ...

aircraft, an Agena upper stage; a Gemini spacecraft; an Apollo command/service module, and a Lunar Excursion Module

The Apollo Lunar Module (LM ), originally designated the Lunar Excursion Module (LEM), was the lunar lander spacecraft that was flown between lunar orbit and the Moon's surface during the United States' Apollo program. It was the first crewed s ...

. Replicas of uncrewed spacecraft included lunar probe Ranger VII; Mariner II and Mariner IV

Mariner 4 (together with Mariner 3 known as Mariner-Mars 1964) was the fourth in a series of spacecraft intended for planetary exploration in a flyby mode. It was designed to conduct closeup scientific observations of Mars and to transmit thes ...

; Syncom, Telstar I, and Echo II communications satellites; Explorer I

Explorer 1 was the first satellite launched by the United States in 1958 and was part of the U.S. participation in the International Geophysical Year (IGY). The mission followed the first two satellites the previous year; the Soviet Union ...

and Explorer XVI; and Tiros

TIROS, or Television InfraRed Observation Satellite, is a series of early weather satellites launched by the United States, beginning with TIROS-1 in 1960. TIROS was the first satellite that was capable of remote sensing of the Earth, enablin ...

and Nimbus

Nimbus, from the Latin for "dark cloud", is an outdated term for the type of cloud now classified as the nimbostratus cloud. Nimbus also may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Halo (religious iconography), also known as ''Nimbus'', a ring of ligh ...

weather satellites.

New York State Pavilion

New York played host to the fair at its six-million-dollar open-air pavilion called the "Tent of Tomorrow". Designed by famed modernist architectPhilip Johnson

Philip Cortelyou Johnson (July 8, 1906 – January 25, 2005) was an American architect best known for his works of modern and postmodern architecture. Among his best-known designs are his modernist Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut; the pos ...

, the 350-feet-by-250-feet (107 × 76 m) pavilion was supported by sixteen 100-feet-high (30-metre) concrete columns, from which a 50,000-square-foot (4,600 m2) roof of polychrome tiles was suspended. Complementing the pavilion were the fair's three observation tower

An observation tower is a structure used to view events from a long distance and to create a full 360 degree range of vision to conduct long distance observations. Observation towers are usually at least tall and are made from stone, iron, an ...

s, two of which had cafeterias in their in-the-round observation-deck crowns. The pavilion's main floor, used for local art and industry displays including a 26-feet (8-metre) scale reproduction of the New York State Power Authority

The New York Power Authority (NYPA), officially the Power Authority of the State of New York, is a New York State public-benefit corporation. It is the largest state public power utility in the United States. NYPA provides some of the lowest-co ...

's St. Lawrence hydroelectric plant, comprised a 9,000-square-foot (800 m2) terrazzo

Terrazzo is a composite material, poured in place or precast, which is used for floor and wall treatments. It consists of chips of marble, quartz, granite, glass, or other suitable material, poured with a cementitious binder (for chemical bindi ...

replica of the official Texaco

Texaco, Inc. ("The Texas Company") is an American Petroleum, oil brand owned and operated by Chevron Corporation. Its flagship product is its Gasoline, fuel "Texaco with Techron". It also owned the Havoline motor oil brand. Texaco was an Indepe ...

highway map of New York State, displaying the map's cities, towns, routes and Texaco gas stations in 567 mosaic panels.

Other state pavilions

Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

exhibited the "World's Largest Cheese". Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

brought a dolphin show, flamingo

Flamingos or flamingoes are a type of Wader, wading bird in the Family (biology), family Phoenicopteridae, which is the only extant family in the order Phoenicopteriformes. There are four flamingo species distributed throughout the Americas ...

s, a talented cockatoo

A cockatoo is any of the 21 parrot species belonging to the family Cacatuidae, the only family in the superfamily Cacatuoidea. Along with the Psittacoidea (true parrots) and the Strigopoidea (large New Zealand parrots), they make up the ord ...

from Miami

Miami ( ), officially the City of Miami, known as "the 305", "The Magic City", and "Gateway to the Americas", is a East Coast of the United States, coastal metropolis and the County seat, county seat of Miami-Dade County, Florida, Miami-Dade C ...

's Parrot Jungle, and water skiers to New York. Oklahoma

Oklahoma (; Choctaw language, Choctaw: ; chr, ᎣᎧᎳᎰᎹ, ''Okalahoma'' ) is a U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States, bordered by Texas on the south and west, Kansas on the nor ...

gave weary fairgoers a restful park to relax in. Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

displayed the state's space-related industries. Visitors could dine at Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only stat ...

's "Five Volcanoes" restaurant.

New York City Pavilion

At the New York City pavilion, the ''Panorama of the City of New York

The ''Panorama of the City of New York'' is an urban model of New York City that is a centerpiece of the Queens Museum. It was originally created for the 1964 New York World's Fair.

Early history

Commissioned by Robert Moses as a celebratio ...

'' (a huge scale model of the city) was on display, complete with a simulated helicopter ride around the metropolis for easy viewing. Left over from the 1939 Fair, this building had been used partially as a recreational public roller skating rink

A roller rink is a hard surface usually consisting of hardwood or concrete, used for roller skating or inline skating. This includes roller hockey, speed skating, roller derby, and individual recreational skating. Roller rinks can be located i ...

.

Bourbon Street Pavilion

Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

had a pavilion called "Louisiana's Bourbon Street" (later renamed to just "Bourbon Street

Bourbon Street (french: Rue Bourbon, es, Calle de Borbón) is a historic street in the heart of the French Quarter of New Orleans. Extending thirteen blocks from Canal Street to Esplanade Avenue, Bourbon Street is famous for its many bars an ...

"), which was inspired by New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

' Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

French Quarter

The French Quarter, also known as the , is the oldest neighborhood in the city of New Orleans. After New Orleans (french: La Nouvelle-Orléans) was founded in 1718 by Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, the city developed around the ("Old Squ ...

. It started off with financial trouble, not being able to complete its construction and subsequently filing for bankruptcy. A private company, called Pavilion Property, bought up the assets and assumed its debts. This prompted Louisiana Governor

The governor of Louisiana (french: Gouverneur de la Louisiane) is the head of state and head of government of the U.S. state of Louisiana. The governor is the head of the executive branch of Louisiana's state government and is charged with enfor ...

John McKeithen

John Julian McKeithen (May 28, 1918 – June 4, 1999) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 49th governor of Louisiana from 1964 to 1972.

Early life

McKeithen was born in Grayson, Louisiana on May 28, 1918. His father was a ...

to sever all ties and withdraw state's sanction, leaving the pavilion completely to private enterprise.

Special media attention was given to a racially integrated minstrel show

The minstrel show, also called minstrelsy, was an American form of racist theatrical entertainment developed in the early 19th century.

Each show consisted of comic skits, variety acts, dancing, and music performances that depicted people spe ...

that was intended to be a satirical anti-bigotry review, called "America, Be Seated", and produced by Mike Todd Jr.

Michael Henry Todd Jr. (October 8, 1929 – May 5, 2002) was an American film producer. He was involved in innovations such as the movie format Smell-o-vision, and the production of a racially-integrated minstrel show for the 1964 World's Fair ...

During the opening of the fair, several civil rights protests were staged by members of the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E.&nb ...

, who believed that the "minstrel-style" show was demeaning to African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American ...

s.

The pavilion included ten theater restaurants, which served a variety of Creole food, a Jazz club

A jazz club is a venue where the primary entertainment is the performance of live jazz music, although some jazz clubs primarily focus on the study and/or promotion of jazz-music. Jazz clubs are usually a type of nightclub or bar, which is license ...

called "Jazzland" which hosted live jazz artists, miniature Mardi Gras parades, a teenage dancing venue, a voodoo shop, and a doll museum. Due to the presence of the various bars, the pavilion was especially popular at night. Notable go-go dancer

Go-go dancers are dancers who are employed to entertain crowds at nightclubs or other venues where music is played. Go-go dancing originated in the early 1960s at the French bar Whisky a Gogo located in Juan-les-Pins. The bar's name was take ...

Candy Johnson

Candy Johnson (February 8, 1944 – October 20, 2012) was an American singer and dancer who appeared in several films in the 1960s.

Biography

She was born on 8 February 1944 as Vicki Jane Husted in Los Angeles County, California to Jeannette 'J ...

headlined a show at a venue called "Gay New Orleans Nightclub". Near the closure of the fair, the pavilion was reported to have achieved the highest gross income of any single commercial pavilion at the fair. The 26-year-old director of operations, Gordon Novel

Gordon Michael Duane Novel (February 7, 1938 – October 3, 2012) was a private investigator and electronics expert, who was known for several controversial investigations. He was most notable for his conflict with District Attorney Jim Garris ...

, was called an "Entrepreneurial Prodigy & Boy Wonder" in ''Variety

Variety may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Entertainment formats

* Variety (radio)

* Variety show, in theater and television

Films

* ''Variety'' (1925 film), a German silent film directed by Ewald Andre Dupont

* ''Variety'' (1935 film), ...

'' for his accomplishments.

Civil rights protests

TheCongress of Racial Equality

The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) is an African Americans, African-American civil rights organization in the United States that played a pivotal role for African Americans in the civil rights movement. Founded in 1942, its stated mission ...

(CORE) organized a protest during the World's Fair. About 700 protestors participated; of those, 300 were arrested. Demonstrators used walkie-talkie

A walkie-talkie, more formally known as a handheld transceiver (HT), is a hand-held, portable, two-way radio transceiver. Its development during the Second World War has been variously credited to Donald Hings, radio engineer Alfred J. Gross, ...

s to communicate during the protest. Protestors demanded that the Civil Rights Act be passed and criticized the lack of inclusive hiring for the World's Fair. During President Johnson's speech, demonstrators shouted "Jim Crow must go!" and "Freedom now!" and jeered as he outlined his plans for the Great Society. The mayor of New York later publicly apologized on behalf of the city.

More radically, Louis Lomax

Louis Emanuel Lomax (August 16, 1922 – July 30, 1970) was an African-American journalist and author. He was also the first African-American television journalist.

Early years

Lomax was born in Valdosta, Georgia. His parents were Emanuel C. Smi ...

, of the Brooklyn chapter of CORE, had proposed a "stall-in"; 500 drivers would go to the fair and stop or deliberately run out of gas on the way there, creating a traffic jam. Because it would clog the highways, it would also have been a protest against Robert Moses and his newly renovated traffic networks. Henry A. Barnes, the New York City Traffic Commissioner, made it illegal to intentionally run out of gas on a New York roadway. Tactics such as using emergency brakes to stop subways and releasing rats during Johnson's speech were also proposed. James Farmer

James Leonard Farmer Jr. (January 12, 1920 – July 9, 1999) was an American civil rights activist and leader in the Civil Rights Movement "who pushed for nonviolent protest to dismantle segregation, and served alongside Martin Luther King Jr." H ...

, who was the national chair of CORE at the time, suspended the group. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

wrote a letter stating that he did not support the stall-in as a tactic, but also would not condemn it. He wrote: "Which is worse, a ‘Stall-In’ at the World’s Fair or a ‘Stall-In’ in the United States Senate? The former merely ties up the traffic of a single city. But the latter seeks to tie up the traffic of history, and endanger the psychological lives of twenty million people". Despite a ''New York Times'' article stating that "the stall is on", only a few drivers actually showed up. Isaiah Brunson, chair of the Brooklyn chapter, promised future protests, but went into hiding a few days later.

American industry

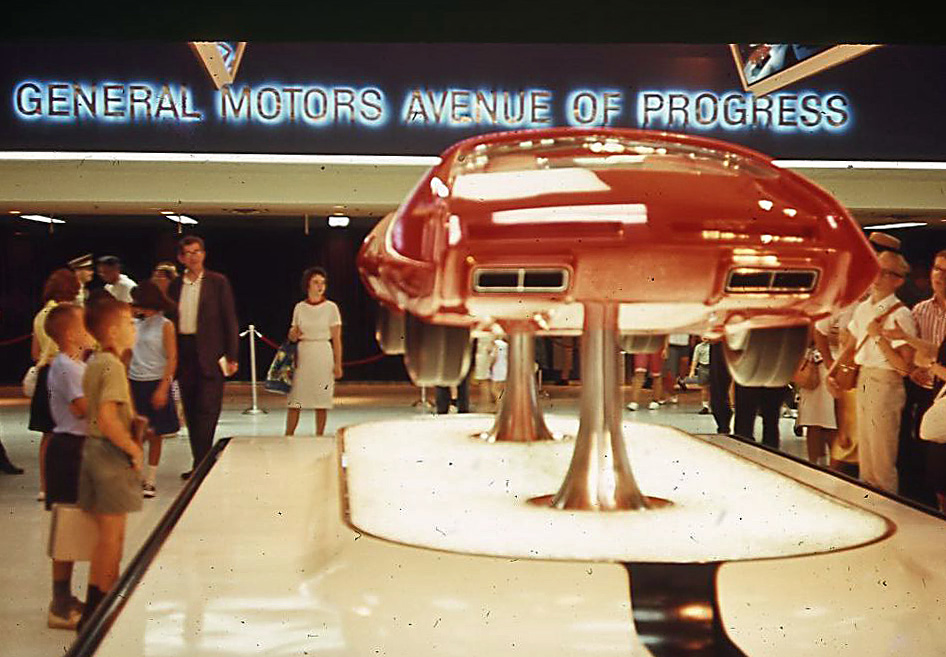

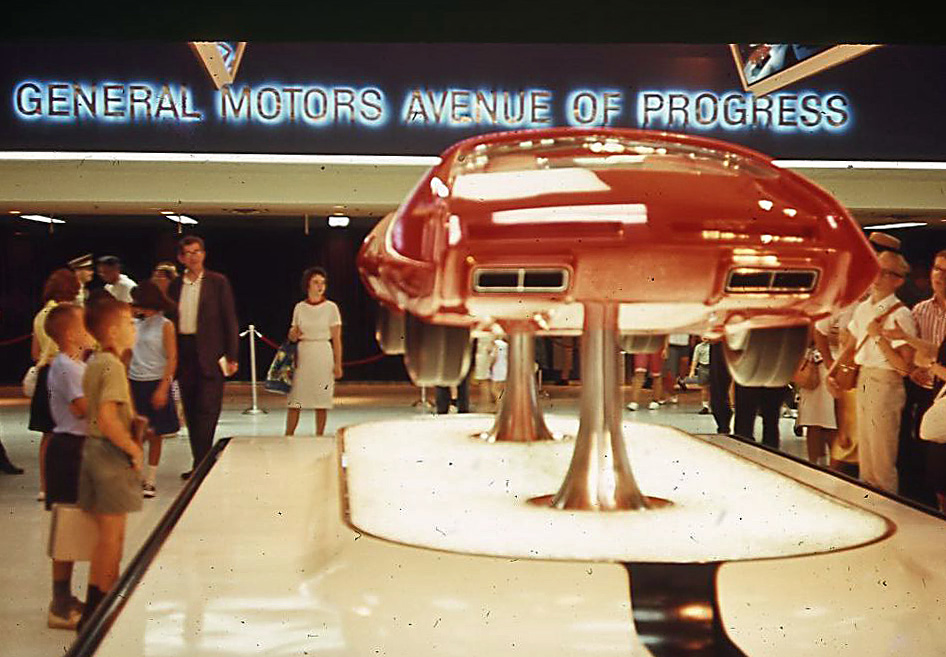

Many of the large US corporations built pavilions to demonstrate their wares, vision, and corporate cultures. These included:General Motors

Industries played a major role at the New York World's Fair of 1939–1940 by hosting huge, elaborate exhibits. Many of them returned to the New York World's Fair of 1964–1965 with even more elaborate versions of the shows that they had presented 25 years earlier. The most notable of these was

Industries played a major role at the New York World's Fair of 1939–1940 by hosting huge, elaborate exhibits. Many of them returned to the New York World's Fair of 1964–1965 with even more elaborate versions of the shows that they had presented 25 years earlier. The most notable of these was General Motors Corporation

The General Motors Company (GM) is an American Multinational corporation, multinational Automotive industry, automotive manufacturing company headquartered in Detroit, Michigan, United States. It is the largest automaker in the United States and ...

whose Futurama

''Futurama'' is an American animated science fiction sitcom created by Matt Groening for the Fox Broadcasting Company. The series follows the adventures of the professional slacker Philip J. Fry, who is cryogenically preserved for 1000 years a ...

proved to be the fair's most popular exhibit, in which visitors seated in moving chairs glided past elaborately detailed miniature 3D model scenery showing what life might be like in the "near-future". Nearly 26 million people took the journey into the future during the fair's two-year run.

IBM

The IBM Corporation had a popular pavilion, where a giant 500-seat grandstand called the "People Wall" was pushed byhydraulic ram

A hydraulic ram, or hydram, is a cyclic water pump powered by hydropower. It takes in water at one "hydraulic head" (pressure) and flow rate, and outputs water at a higher hydraulic head and lower flow rate. The device uses the water hammer ef ...

s high up into an ellipsoidal

An ellipsoid is a surface that may be obtained from a sphere by deforming it by means of directional scalings, or more generally, of an affine transformation.

An ellipsoid is a quadric surface; that is, a surface that may be defined as the z ...

theater designed by Eero Saarinen

Eero Saarinen (, ; August 20, 1910 – September 1, 1961) was a Finnish-American architect and industrial designer noted for his wide-ranging array of designs for buildings and monuments. Saarinen is best known for designing the General Motors ...

. There, a film by Charles and Ray Eames

Charles Eames ( Charles Eames, Jr) and Ray Eames ( Ray-Bernice Eames) were an American married couple of industrial designers who made significant historical contributions to the development of modern architecture and furniture through the work of ...

titled ''Think'' was shown on fourteen projectors on nine screens, illuminating the workings of computer logic. At ground level beneath the theater, visitors could explore '' Mathematica: A World of Numbers... and Beyond'' (an exhibit of mathematical models and curiosities) and view the ''Mathematics Peep Show'' (a series of short films illustrating basic mathematical concepts).

Bell System

TheBell System

The Bell System was a system of telecommunication companies, led by the Bell Telephone Company and later by the American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T), that dominated the telephone services industry in North America for over one hundr ...

(prior to its break up into regional companies) hosted a 15-minute ride in moving armchairs depicting the history of communications in dioramas and film named ''Ride of Communications''. Other Bell exhibits included the Picturephone

The history of videotelephony covers the historical development of several technologies which enable the use of video, live video in addition to telecommunication, voice telecommunications. The concept of videotelephony was first popularized in t ...

as well as a demonstration of the computer modem

A modulator-demodulator or modem is a computer hardware device that converts data from a digital format into a format suitable for an analog transmission medium such as telephone or radio. A modem transmits data by modulating one or more car ...

.

Westinghouse

The

The Westinghouse Corporation

The Westinghouse Electric Corporation was an American manufacturing company founded in 1886 by George Westinghouse. It was originally named "Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company" and was renamed "Westinghouse Electric Corporation" in ...

planted a second time capsule

A time capsule is a historic cache of goods or information, usually intended as a deliberate method of communication with future people, and to help future archaeologists, anthropologists, or historians. The preservation of holy relics dates ba ...

next to an earlier 1939 version; today both Westinghouse Time Capsules

The Westinghouse Time Capsules are two time capsules prepared by the Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company (later Westinghouse Electric Corporation). One was made in 1939 and the other in 1965. They are filled with contemporary articles ...

are marked by a monument southwest of the Unisphere which is to be opened in the year 6939. Some of its contents were a World's Fair Guidebook, an electric toothbrush

An electric toothbrush is a toothbrush that makes rapid automatic bristle motions, either back-and-forth oscillation or rotation-oscillation (where the brush head alternates clockwise and counterclockwise rotation), in order to clean teeth. Motio ...

, credit card

A credit card is a payment card issued to users (cardholders) to enable the cardholder to pay a merchant for goods and services based on the cardholder's accrued debt (i.e., promise to the card issuer to pay them for the amounts plus the o ...

s (relatively new at the time), and a 50-star United States flag

The national flag of the United States of America, often referred to as the ''American flag'' or the ''U.S. flag'', consists of thirteen equal horizontal stripes of red (top and bottom) alternating with white, with a blue rectangle in the ca ...

.

Sinclair Oil

TheSinclair Oil Corporation

Sinclair Oil Corporation was an American petroleum corporation, founded by Harry F. Sinclair on May 1, 1916, the Sinclair Oil and Refining Corporation combined, amalgamated, the assets of 11 small petroleum companies. Originally a New York cor ...

sponsored "Dinoland", featuring life-size replicas of nine different dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

s, including the corporation's signature Brontosaurus

''Brontosaurus'' (; meaning "thunder lizard" from Greek , "thunder" and , "lizard") is a genus of gigantic quadruped sauropod dinosaurs. Although the type species, ''B. excelsus'', had long been considered a species of the closely related ' ...

. The statues were created by Louis Paul Jonas

Louis Paul Jonas (July 17, 1894 – February 16, 1971) was an American sculptor of wildlife, taxidermist, and natural history exhibit designer.

Born in Budapest, Hungary, Jonas moved to the United States at the age of 12 and went to work at ...

Studios in Hudson, New York

Hudson is a city and the county seat of Columbia County, New York, United States. As of the 2020 census, it had a population of 5,894. Located on the east side of the Hudson River and 120 miles from the Atlantic Ocean, it was named for the rive ...

.(1) (2)

(3) They also contained a "space age" gas station with orbiting gas pumps shaped like rockets, and a marine fuel station in the vicinity of the World's Fair Marina.

Ford

TheFord Motor Company

Ford Motor Company (commonly known as Ford) is an American multinational automobile manufacturer headquartered in Dearborn, Michigan, United States. It was founded by Henry Ford and incorporated on June 16, 1903. The company sells automobi ...

introduced the Ford Mustang automobile to the public at its pavilion on April 17, 1964. The Ford pavilion featured the "Magic Skyway" ride, in which guests rode in Ford, Mercury, and Lincoln convertibles past scenes featuring dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...