1924 24 Hours Of Le Mans on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The 1924 24 Hours of Le Mans was the 2nd Grand Prix of Endurance, and took place on 14 and 15 June 1924. It was the second part of three consecutive annual races for the

The 1924 24 Hours of Le Mans was the 2nd Grand Prix of Endurance, and took place on 14 and 15 June 1924. It was the second part of three consecutive annual races for the

Racing Sports Cars

nbsp;– Le Mans 24 Hours 1924 entries, results, technical detail. Retrieved 31 Aug 2018

Le Mans History

nbsp;– entries, results incl. photos, hourly positions. Retrieved 31 Aug 2018

nbsp;– results, reserve entries & chassis numbers. Retrieved 31 Aug 2018

nbsp;– results, chassis numbers & hour-by-hour places (in French). Retrieved 31 Aug 2018

Radio Le Mans

nbsp;– Race article and review by Charles Dressing. Retrieved 5 Dec 2018

Unique Cars & Parts

nbsp;– results & reserve entries. Retrieved 31 Aug 2018

nbsp;– Le Mans results & reserve entries. Retrieved 31 Aug 2018 {{DEFAULTSORT:1924 24 Hours Of Le Mans

The 1924 24 Hours of Le Mans was the 2nd Grand Prix of Endurance, and took place on 14 and 15 June 1924. It was the second part of three consecutive annual races for the

The 1924 24 Hours of Le Mans was the 2nd Grand Prix of Endurance, and took place on 14 and 15 June 1924. It was the second part of three consecutive annual races for the Rudge-Whitworth

Rudge Whitworth Cycles was a British bicycle, bicycle saddle, motorcycle and sports car wheel manufacturer that resulted from the merger of two bicycle manufacturers in 1894, Whitworth Cycle Co. of Birmingham, founded by Charles Henry Pug ...

Triennial Cup, as well simultaneously being the first race in the new 1924-25 Rudge-Whitworth

Rudge Whitworth Cycles was a British bicycle, bicycle saddle, motorcycle and sports car wheel manufacturer that resulted from the merger of two bicycle manufacturers in 1894, Whitworth Cycle Co. of Birmingham, founded by Charles Henry Pug ...

Biennial Cup.

With tougher target distances, as well as hot weather, the cars had to be pushed harder and this year only 12 of the 41 starters completed the 24 hours.Spurring 2011, p.92-3 The 4-litre Chenard-Walcker

Chenard-Walcker, also known as Chenard & Walcker, was a French automobile and commercial vehicle manufacturer from 1898 to 1946. Chenard-Walcker then designed and manufactured trucks marketed via Peugeot sales channels until the 1970s. The facto ...

of the 1923 winners René Léonard

René Léonard (23 June 1889 - 15 August 1965) was a French racing driver who, along with André Lagache

André Lagache (21 January 1885 – 2 October 1938) was a French racing driver who, along with René Léonard, won the inaugural 24 Hours ...

and André Lagache

André Lagache (21 January 1885 – 2 October 1938) was a French racing driver who, along with René Léonard, won the inaugural 24 Hours of Le Mans in .

Career

Lagache and Léonard were engineers at automobile manufacturer Chenard et Walcker, ...

had the early lead, for the first three hours, until it caught fire on the Mulsanne Straight. Thereafter it was a battle between the three-car Lorraine-Dietrich

Lorraine-Dietrich was a French automobile and aircraft engine manufacturer from 1896 until 1935, created when railway locomotive manufacturer ''Société Lorraine des Anciens Etablissements de Dietrich et Cie de Lunéville'' (known as ''De Dietri ...

team and the British Bentley

Bentley Motors Limited is a British designer, manufacturer and marketer of luxury cars and SUVs. Headquartered in Crewe, England, the company was founded as Bentley Motors Limited by W. O. Bentley (1888–1971) in 1919 in Cricklewood, North ...

.

The first Lorraine-Dietrich

Lorraine-Dietrich was a French automobile and aircraft engine manufacturer from 1896 until 1935, created when railway locomotive manufacturer ''Société Lorraine des Anciens Etablissements de Dietrich et Cie de Lunéville'' (known as ''De Dietri ...

had been delayed on Saturday night, the second went off the road during the night and the third was held up with two punctures then a blown engine trying to make up the lost time. The Bentley also had its problems but with two hours to go it had a significant lead when it pitted for a precautionary wheel-change. This soon became a big problem as one wheel could not be taken off and half an hour was lost. The delay meant its remaining laps would not be counted according to the new race-regulations, as the average speed would be below that achieved to reach their target distance. Although the remaining two Lorraines pushed hard they fell just one lap short.

The Bentley victory brought international acclaim and cemented the popularity of the race as a significant European event.Laban 2001, p.40

Regulations

After the success of their inaugural 24-hour event, theAutomobile Club de l'Ouest

The Automobile Club de l'Ouest (English: Automobile Club of the West), sometimes abbreviated to ACO, is the largest automotive group in France. It was founded in 1906 by car building and racing enthusiasts, and is most famous for being the organ ...

(ACO) set about making further improvements. Firstly, the race-timing was moved to the summer solstice in late June to make the best use of the extended daylight as well as the higher probability of better weather.Spurring 2011, p.92-3Clausager 1982, p.30 The ACO also recognised that the Triennial Cup format was unworkable after an unexpectedly large number of cars had qualified from the year before. The current trophy stayed active, but not renewed. Émile Coquille, co-organiser and representative of the sponsor Rudge-Whitworth

Rudge Whitworth Cycles was a British bicycle, bicycle saddle, motorcycle and sports car wheel manufacturer that resulted from the merger of two bicycle manufacturers in 1894, Whitworth Cycle Co. of Birmingham, founded by Charles Henry Pug ...

was still keen on a multi-year format, so a compromise Biennial Cup was initiated instead. Teams had to nominate which of their cars would compete for the Triennial Cup, while all entries were eligible for the Biennial Cup.Spurring 2011, p.90Spurring 2011, p.98-9Spurring 2011, p.100-1

Specifications were tightened up on chassis features like windshields, running boards and seats to prevent abuse by manufacturers trying to save weight. It became compulsory to carry one spare wheel on board, exhausts had to be aligned to not blow dust off the road, and cars had to have functioning headlights between designated hours of darkness (8.30pm to 4am). In the original interests of furthering the advance of touring-car technology, convertibles had to come in after 5 laps and put up their hoods. Then after running for at least two laps with hoods up, they would come in and have them officially checked for robustness before dropping them back down. Failure would result in disqualification. Finally, the car companies also had to present written evidence of the requisite 30 production examples.

In the interests of driver safety, protective headgear now had to be worn. A minimum of 20 laps had to be driven before a car could stop to replenish fuel, water or oil fluids, still done solely by the driver.Clausager 1982, p.19 Cars did not need to complete the final lap at the end of the 24 hours if they had met their target distance, but any extra laps had to be done at or above the average speed of the rest of their race to be counted.Spurring 2011, p.96-7 After the lenient minimum target distances of the previous year, these were lifted significantly particularly for the smaller engined cars The distances included the following:

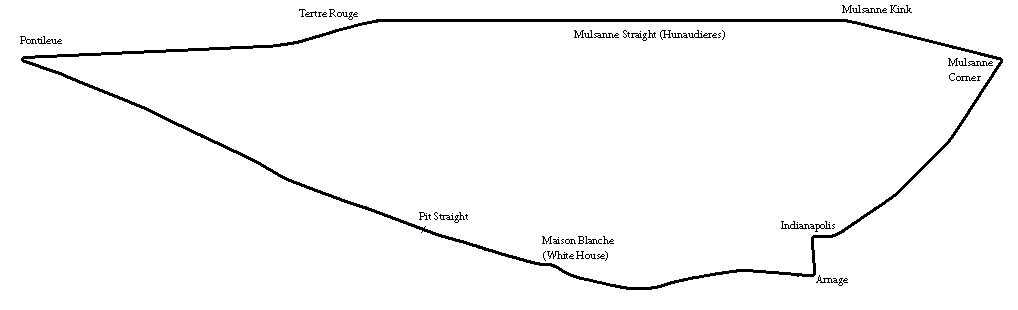

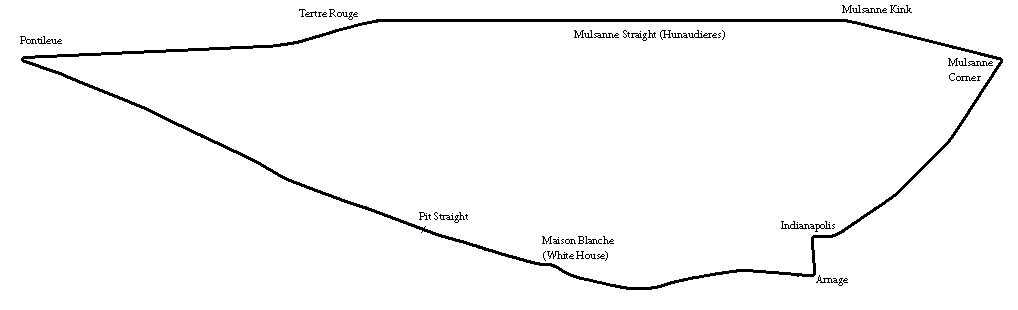

The Track

Once again, an effort was made to apply a temporary mixture of gravel, dirt and tar to the road surface in spring-time. A third layer was put down on the long Hunaudières straight from Le Mans city to Mulsanne (more commonly known as the Mulsanne Straight). For the spectators, further efforts were made to provide entertainment through the event. As well as the cafés and jazz-band, a new dance-hall, a boxing ring and a chapel were built. The first campsite area was also designated for people to stay on-site overnight.Entries

There were 30 finishers from the1923

Events

January–February

* January 9 – Lithuania begins the Klaipėda Revolt to annex the Klaipėda Region (Memel Territory).

* January 11 – Despite strong British protests, troops from France and Belgium occupy the Ruhr area, t ...

eligible for entry in the race, but only 21 were taken up. Six of the eleven manufacturers did not return, however another six French manufacturers stepped in to fill their places, leaving Bentley as the only foreign entry. Sunbeam

A sunbeam, in meteorological optics, is a beam of sunlight that appears to radiate from the position of the Sun. Shining through openings in clouds or between other objects such as mountains and buildings, these beams of particle-scattered sunl ...

had put in an entry, but withdrew it later to focus on the French Grand Prix

The French Grand Prix (french: Grand Prix de France), formerly known as the Grand Prix de l'ACF (Automobile Club de France), is an auto race held as part of the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile's annual Formula One World Championsh ...

racing.

After a winning debut in the 1923 race, Chenard-Walcker

Chenard-Walcker, also known as Chenard & Walcker, was a French automobile and commercial vehicle manufacturer from 1898 to 1946. Chenard-Walcker then designed and manufactured trucks marketed via Peugeot sales channels until the 1970s. The facto ...

returned with a big team of six cars. The biggest car in the field was a 4-litre, rated at 22CV and built by effectively putting two 2-litre engines end to end. It delivered about 125 bhp giving a claimed 170 kp/h (105 mph) top speed. It was given to the previous year's winners René Léonard

René Léonard (23 June 1889 - 15 August 1965) was a French racing driver who, along with André Lagache

André Lagache (21 January 1885 – 2 October 1938) was a French racing driver who, along with René Léonard, won the inaugural 24 Hours ...

and André Lagache

André Lagache (21 January 1885 – 2 October 1938) was a French racing driver who, along with René Léonard, won the inaugural 24 Hours of Le Mans in .

Career

Lagache and Léonard were engineers at automobile manufacturer Chenard et Walcker, ...

. A 3-litre 15CV, similar to the successful 1923 models was raced by the two Bachmann brothers, Raoul and Fernand. For the Triennial Cup, the team entered its smaller cars: a pair of the Type TT 12CV 2-litres as well as one of the two new Type Y 1.5-litre cars present.Spurring 2011, p.101-3

After being initially sceptical the previous year, W. O. Bentley

Walter Owen Bentley, MBE (16 September 1888 – 13 August 1971) was an English engineer who founded Bentley Motors Limited in London. He was a motorcycle and car racer as a young man. After making a name for himself as a designer of aircraft a ...

was now a firm convert, and offered to provide John Duff

John Francis Duff (January 17, 1895 – January 8, 1958) was a Canadian racecar driver who won many races and has been inducted in the Canadian Motorsport Hall of Fame. He was one of only two Canadians who raced and won on England’s famous Br ...

full factory support for a return to Le Mans. Learning from the previous year, his new Bentley 3 Litre

The Bentley 3 Litre was a car chassis manufactured by Bentley. The company's first, it was developed from 1919 and made available to customers' coachbuilders from 1921 to 1929. The Bentley was very much larger than the 1368 cc Bugattis that domin ...

now had four-wheel brakes, and wire mesh put over the headlights and matting wrapped the fuel tank – both measures put in to reduce potential damage from flying stones. The durable Rapson tyres were employed again on the Rudge-Whitworth wheels. Duff also advised changes to make mechanical fixes quicker during the race and recommended some team members be stationed at Mulsanne corner with a telephone so he could signal if he was going to be pitting at the end of the lap. He also did extensive practise putting up and taking down the hood.Spurring 2011, p.94-6

A new range of the La Lorraine-Dietrich

Lorraine-Dietrich was a French automobile and aircraft engine manufacturer from 1896 until 1935, created when railway locomotive manufacturer ''Société Lorraine des Anciens Etablissements de Dietrich et Cie de Lunéville'' (known as ''De Dietri ...

B3-6 3.5-litre cars were unveiled at the end of 1923, including a Sport version deliberately built for racing. Now with a 4-speed gearbox, the new engine put out 115 bhp, getting the car up to 145 kp/h (90 mph). Three cars were entered, two running on Michelin tyres and the other on Englebert.

Bignan

Bignan (; br, Begnen) is a Communes of France, commune in the Morbihan Departments of France, department in Brittany (administrative region), Brittany in northwestern France.

Location

The town is based on the Landes de Lanvaux.

Bignan is locate ...

doubled its team this year to four cars with their distinctive triple headlights. The new 3-litre engine was powerful, putting out 124 bhp and the 2-litre cars were new models, without the expensive “Desmo-chromique”engine. The team had already done well, winning the first post-war Monte Carlo Rally

The Monte Carlo Rally or Rallye Monte-Carlo (officially ''Rallye Automobile de Monte-Carlo'') is a rallying event organised each year by the Automobile Club de Monaco. The rally now takes place along the French Riviera in Monaco and southeast ...

and setting 24-hour endurance records on the new Montlhéry

Montlhéry () is a Communes of France, commune in the Essonne Departments of France, department in Île-de-France in northern France. It is located from Paris.

History

Montlhéry lay on the strategically important road from Paris to Orléans. U ...

circuit.Spurring 2011, p.109

Ariès

The Ariès was a French automobile manufactured by La Société des Automobile Ariès in Asnières-sur-Seine. The firm was founded in 1902 by Baron Charles Petiet. The decision to end production was taken in 1937. Around 20,000 vehicles were pr ...

was a new entrant this year and arrived with four cars. It was founded in 1903 by former Panhard

Panhard was a French motor vehicle manufacturer that began as one of the first makers of automobiles. It was a manufacturer of light tactical and military vehicles. Its final incarnation, now owned by Renault Trucks Defense, was formed ...

et Levassor engineer ''Baron'' Charles Petiet and had competed in the early inter-city races. Two shortened GP versions of the standard Type S were prepared, one with a 3.2-litre and the other with a 3-litre engine. There were also two 1100cc cars entered: an older CC2 and a new CC4 4-seater. Getting back into post-war racing in 1924 Petiet assembled a team of well-known drivers. Fernand Gabriel was leading the ill-fated 1903 Paris-Madrid race when it was stopped. Arthur Duray

Arthur Duray (9 February 1882 – 11 February 1954) was born in New York City of Belgian parents and later became a French citizen. An early aviator, he held Belgian license #3. He is probably best known today for breaking the land speed record on ...

had set land speed records before the war and finished second in the 1914 Indianapolis 500

The 4th International 500-Mile Sweepstakes Race was held at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway on Saturday, May 30, 1914.

René Thomas was the race winner, accompanied by riding mechanic Robert Laly.

Background

Race history

The Indianapolis ...

behind René Thomas. Robert Laly had been Thomas’ riding mechanic in the same race.Spurring 2011, p.105-7

Rolland-Pilain

Rolland-Pilain was a French car maker formally established on 4 November 1905 at 95, rue Victor-Hugo in Tours by François Rolland and Émile Pilain.

The partners

Rolland was already a successful businessman locally who had made a fortune in t ...

again had four cars entered. The latest C23 version had a 2-litre engine capable of 50 bhp and 120 kp/h (75 mph). For the race the company entered lengthened four-seat tourer versions.Spurring 2011, p.110-1 Brasier

Brasier was a French automobile manufacturer, based in the Paris conurbation, and active between 1905 and 1930. The firm began as Richard-Brasier in 1902, and became known as Chaigneau-Brasier in 1926.

__TOC__

Origins

Charles-Henri Brasier wo ...

returned with another pair of its 2.1-litre TB4 model with its 4-speed gearbox.Spurring 2011, p.103 Charles Montier

Charles Pierre Elie Montier (28 June 1879 – June 1952) was a French racing driver and automotive engineer whose race entries included the inaugural 24 Hours of Le Mans.

Montier, with his father Elie and friend Gillet, built a steam car – th ...

also returned with his modified Ford special, now fitted with 4-wheel brakes. Again Montier drove it himself with his brother-in-law Albert Ouriou.Spurring 2011, p.110

Oméga-Six

Automobiles Oméga-Six was a French automobile manufactured in the Paris region by Gabriel Daubeck between 1922 and 1930.Linz, Schrader: ''Die Internationale Automobil-Enzyklopädie.''Georgano: ''The Beaulieu Encyclopedia of the Automobile.''Georg ...

was another new entrant this year. A venture founded in 1922 by Gabriel Daubech, who had made his money in timber. He wanted to get into the mid-range car market with a new option – a high-end 6-cylinder. The cars had a torpédo bodystyle, 4-speed gearbox with a 2-litre engine produced 50 bhp capable of 120 kp/h (75 mph).Spurring 2011, p.114 Louis Chenard (unrelated to Chenard-Walcker) had a small self-named Parisian car-factory. He ran one of his torpedo-style Type E tourers having a 1.2-litre Chapuis-Dornier Chapuis-Dornier was a French manufacturer of proprietary engines for automobiles from 1904 to 1928 in Puteaux near Paris. Between 1919 and 1921 it displayed a prototype automobile, but it was never volume produced.Linz, Schrader: ''Die große Autom ...

engine, with his brother Émile.Spurring 2011, p.118 Likewise Georges and René Pol, who made taxis and delivery vans, wanted to venture into the sports car field. So they built a simple 1.7-litre car, named the GRP, and entered it into the race.

Georges Irat

The Georges Irat was a French automobile manufactured by engine builder Georges Irat from 1921 to 1953.

Between two World Wars

The company's first product was an ohv 1990cc four-cylinder car designed by Maurice Gaultier who had been with Delag ...

arrived with a “Compétition Spéciale” version of the 4A. With a higher-revving 2-litre engine that put out 60 bhp getting it up to 135 kp/h (85 mph).Spurring 2011, p.112 This year Corre La Licorne

Corre La Licorne was a French car maker founded 1901 in Levallois-Perret, at the north-western edge of central Paris, by Jean-Marie Corre. Cars were produced until 1947.

The names

The first cars were named Corre, but racing successes by a driv ...

had three of its new model, the Type V16, now with a 10CV 1.5-litre SCAP

SCAP may refer to:

* S.C.A.P., an early French manufacturer of cars and engines

* Security Content Automation Protocol

* ''The Shackled City Adventure Path'', a role-playing game

* SREBP cleavage activating protein

* Supervisory Capital Assessment ...

engine. The “boat-tail” chassis had a 4-speed gearbox and 4-wheel brakes.Spurring 2011, p.115-7 New entry Alba

''Alba'' ( , ) is the Scottish Gaelic name for Scotland. It is also, in English language historiography, used to refer to the polity of Picts and Scottish people, Scots united in the ninth century as the Kingdom of Alba, until it developed i ...

also used the 1.5-litre SCAP engine, and also had its patented servo-less four-wheel braking also used by the Citroën Type C

Citroën () is a French automobile brand. The "Automobiles Citroën" manufacturing company was founded in March 1919 by André Citroën. Citroën is owned by Stellantis since 2021 and previously was part of the PSA Group after Peugeot acquired 8 ...

.Spurring 2011, p.117

SARA had three of its ATS 2-seater model, one entered in the Triennial Cup and the other two in the Biennial Cup.Spurring 2011, p.112

This year Amilcar

The Amilcar was a French automobile manufactured from 1921 to 1940.

History

Foundation and location

Amilcar was founded in July 1921 by Joseph Lamy and Emile Akar. The name "Amilcar" was an imperfect anagram of the partners' names. The b ...

brought two cars – the same privately owned CV that had done well the previous year, and a new Type C Grans Sport. Its 1074cc engine produced 33 bhp and was driven by works drivers André Morel and Marius Mestivier.Spurring 2011, p.104 Majola had been racing cycle-cars after the war, but arrived at Le Mans with a bigger 1.1-litre 7CV 4-seater tourer.Spurring 2011, p.115

Practice

Once again, with no official practice session, several teams arrived earlier in the week before the scrutineering on Friday to do some practice laps. However, Maurice Rost crashed his Georges Irat and it could not be repaired in time to take the start.Race

Start

The ACO were vindicated for changing the event date, with hot, dry weather over race-week. This carried on into the weekend and dust would prove to be the issue this year.Rudge-Whitworth

Rudge Whitworth Cycles was a British bicycle, bicycle saddle, motorcycle and sports car wheel manufacturer that resulted from the merger of two bicycle manufacturers in 1894, Whitworth Cycle Co. of Birmingham, founded by Charles Henry Pug ...

representative Émile Coquille was the official starter this year. Last away was Charles Montier whose Ford Special proved temperamental to start.Clarke 1998, p.15: Motor Jun17 1924 At the end of the first lap, it was the 3-litre Bignans of de Marne and Ledure with Lagache's big 4-litre Chenard-Walcker between them setting the pace.

Straight away, de Marne easily beat Clement's lap record from the previous year by 15 seconds. Then after five laps, the convertibles had to come in to do their compulsory raising of the hood. Lagache almost missed his pit signal, having to brake heavily and reverse 100 metres to his pit spot. Duff's practicing paid off as he only took 40 seconds to put his up. But fastest of all were Montier and Lucien Erb, in his SARA, who only took 27 seconds.

But many cars were already in the pits early. Two of the Corre-La Licornes, an Alba and Duray's Ariès had already retired with engine troubles. The Bachmann's Chenard-Walcker caught fire while in the pits, the two Oméga-Six then retired as did the leading Bignans, suffering from overheating. De Marne was disqualified when he refilled water too early after the radiator plug came loose.Clarke 1998, p.16: Motor Jun17 1924 Louis Chenard's only appearance at Le Mans also ended early when a stone through the radiator stopped it seven laps before the 20-lap replenishment point.

Duff came in to refuel but was warned by an official he had only done 19 laps. Fortunately, the Bentley still had enough to complete one further lap and avoid disqualification.Spurring 2011, p.96-7 But the Rolland-Pilain

Rolland-Pilain was a French car maker formally established on 4 November 1905 at 95, rue Victor-Hugo in Tours by François Rolland and Émile Pilain.

The partners

Rolland was already a successful businessman locally who had made a fortune in t ...

team was in even direr straits – they had fitted their cars with fuel tanks that were too small. De Marguenat ran out of fuel after 18 laps, and the others (after being frantically told to slow down) only just made their first stop. Thereafter the cars had to be driven very conservatively to make it through to each stop. Marinier miscalculated and ran out of fuel on Sunday morning, but the other cars survived and, from not having been driven hard, ran well and still exceeded their race targets.

So, without close pursuit, Lagache was able to set about building a sizeable lead, while lowering the lap record even further. At the 3-hour mark he was leading from Laly's Ariès, the Lorraine triad, the Georges-Irat then Duff in the Bentley. Then at 8pm as dusk fell, soon after Léonard took over the leading car, the big Chenard-Walcker caught fire going down the Mulsanne Straight. He was able to pull over and get out safely, but the car was destroyed.

Night

After six hours as night fell, there were already only 25 cars left in the race. The Ariès had been leading after the demise of the Chenard-Walcker, then was delayed. The leading four cars had done 33 laps. Duff had to pit to clear a blockage in his gearbox. After half an hour and much hammering it was found to be an electrics staple.Clarke 1998, p.17: Motor Jun17 1924 Just before midnight, Laly's 3.2-litre Ariès had to be retired with a blown head gasket. The two Bignans were now running 5th and 6th, the best of the 2-litre cars. At 2am the two Lorraines still had a narrow lead over the Bentley in third. But at 3am de Courcelles slid off the road and bent his Lorraine's chassis delaying it as repairs were done, and slowing it for the rest of the race. The Bentley moved up when Bloch then had to stop to repair broken rear shock absorbers – the Lorraine's Hartfordduralumin

Duralumin (also called duraluminum, duraluminium, duralum, dural(l)ium, or dural) is a trade name for one of the earliest types of age-hardenable aluminium alloys. The term is a combination of '' Dürener'' and ''aluminium''.

Its use as a tra ...

units not strong enough for the treatment on the rough roads.

With the problems of the bigger cars, the de Tornaco/Barthélémy Bignan then found itself in second place overall at half-time. The 12CV Chenard-Walcker running 7th lost two laps when de Zúñiga burnt his hand doing engine repairs, but his co-driver Dauvergne could not be found to take over and had to be hailed over the loudspeakers.

Morning

As a clear morning dawned the leading two cars were still dicing until a second puncture on the Lorraine at 9am gave the Bentley a solid lead. At 10am, at three-quarter distance, Duff had done 97 laps with a 2 minute-lead over Bloch (96 laps) and further back, de Tornaco's Bignan (93 laps), Pisart's Chenard-Walcker and the other Bignan in 6th. Clement started putting in fast laps, extending his lead by ten seconds a lap, and it started overworking the Lorraine's engine as it struggled to keep up. Overtaken by the other two Lorraines moving back up the field, the Bignans slowed down. Soon after noon the Marie/Springuel car had to retire and the de Tornaco/Barthélémy car was delayed with engine issues. Then, at 1pm, a valve broke in Bloch's engine and his Lorraine had to be retired. Meanwhile, the other two Lorraines, had been going as hard as they could to make up lost time and got themselves back up to second and third after their earlier delays.Finish and post-race

Although the Rapson tyres were still working well, at 2.30pm Bentley called their car in for a precautionary change of the rear wheels. This soon became a major problem when one of the wheels appeared to have tampered with and could not be taken off. When they finally got out the pits with an hour still to run, Duff had done 120 laps (five ahead of their target). The long stop had, however, left the Bentley very close to losing the race as its final five laps (including pit-stop time) would be well below their prior race-average and therefore not be counted per the updated ACO regulations. So although Duff did five more laps over the last hour, they were not included. However, their lead was such that the 120 they had before the stop was just enough to take the victory by just one lap. It also meant the Bentley covered a shorter distance than Lagache/Léonard had covered in the previous year. The two Lorraine-Dietrichs came in second and third, half a lap apart (having only just made their target distances), eight laps clear of the two 2-litre Chenard-Walckers. Neither of those cars were actually running at the end, when both drivers were left marooned when their cars’ brakes locked up solid out on the track in the last hour, however having exceeded their targets they were classified. The little 1-litre Amilcar, after an excellent run the previous year, was the final classified finisher. Doing two laps fewer than 1923 it was still enough to meet its new target and qualify for the third race. The speed and weather had taken its toll on the big cars, and many only just made their assigned target distances. Best performances, winning the second interim leg of the Triennial Cup was the Verpault/Delabarre Brasier, ahead of the 2-litre Chenard-Walcker of Dauvergne/de Zúñiga and the Bentley. Only nine cars, of the twenty-one eligible, qualified for the third leg.Spurring 2011, p.120 As it transpired, Brasier leading the competition would not return to compete for the Cup. Financial troubles meant the company was sold in the early months of 1926. Although neither of the 2-litre Chenard-Walckers were running at the finish they had still met their qualifying distance and were the two leading cars for the Biennial Cup, for which only eight cars qualified. In contrast two of the SARAs were unlucky to break down just laps short of meeting their target distances. Just five weeks later another iconic endurance race had its inaugural race – the Spa 24 hours was won by a privateer 3-litre Bignan, ahead of the Lagache/Pisart Chenard-Walcker. Colomb's Corre-La Licorne won the 2-litre class and a privateer Amilcar won the 1100cc class.Spurring 2011, p.101-3Spurring 2011, p.121Official results

Finishers

Results taken from Quentin Spurring's book, officially licensed by the ACOSpurring 2015, p.2 Although there were no official engine classes, the highest finishers in unofficial categories aligned with the Index targets are in Bold text. *Note *: car also entered in the Triennial Cup. *Note **: Final laps not counted, as average speed was too slow. *Note ***: Unknown why this many laps did not place the car 3rd overall, but still 1st in the Rudge-Whitworth competition. *Note ****: Not Classified because did not meet target distance.Did Not Finish

Did Not Start

Interim Coupe Triennale Rudge-Whitworth Positions

Interim Coupe Biennale Rudge-Whitworth Positions

Footnotes

Highest Finisher in Class

*Note: setting a new class distance record. With no official class divisions, these are the highest finishers in unofficial categories aligned with the Index targets.Statistics

Taken from Quentin Spurring's book, officially licensed by the ACO * Fastest Lap – A. Lagache, #3 Chenard-Walcker Type U 22CV Sport – 9:19secs; * Longest Distance – * Average Speed on Longest Distance – ;CitationsReferences

* Clarke, R.M. - editor (1998) Le Mans 'The Bentley & Alfa Years 1923-1939' Cobham, Surrey: Brooklands Books * Clausager, Anders (1982) Le Mans London: Arthur Barker Ltd * Laban, Brian (2001) Le Mans 24 Hours London: Virgin Books * Spurring, Quentin (2015) Le Mans 1923-29 Yeovil, Somerset: Haynes PublishingExternal links

Racing Sports Cars

nbsp;– Le Mans 24 Hours 1924 entries, results, technical detail. Retrieved 31 Aug 2018

Le Mans History

nbsp;– entries, results incl. photos, hourly positions. Retrieved 31 Aug 2018

nbsp;– results, reserve entries & chassis numbers. Retrieved 31 Aug 2018

nbsp;– results, chassis numbers & hour-by-hour places (in French). Retrieved 31 Aug 2018

Radio Le Mans

nbsp;– Race article and review by Charles Dressing. Retrieved 5 Dec 2018

Unique Cars & Parts

nbsp;– results & reserve entries. Retrieved 31 Aug 2018

nbsp;– Le Mans results & reserve entries. Retrieved 31 Aug 2018 {{DEFAULTSORT:1924 24 Hours Of Le Mans

Le Mans

Le Mans (, ) is a city in northwestern France on the Sarthe River where it meets the Huisne. Traditionally the capital of the province of Maine, it is now the capital of the Sarthe department and the seat of the Roman Catholic diocese of Le Man ...

1924 in French motorsport

24 Hours of Le Mans races