Ăźles Des Saintes on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Ăles des Saintes (; "Islands of the Female Saints"), also known as Les Saintes, is a group of small islands in the

On 12 April 1782, after the military campaign of January in Basseterre on the island of Saint Christopher, the French fleet of

On 12 April 1782, after the military campaign of January in Basseterre on the island of Saint Christopher, the French fleet of

Guadeloupe island was also conquered on 26 February 1810 by the British.. The French Governor

Guadeloupe island was also conquered on 26 February 1810 by the British.. The French Governor  In 1851, a penitentiary was built on ''Petite Martinique island'', which became renamed ''ßlet à Cabrit''; in 1856 a prison reserved for women replaced it. It was destroyed in 1865 by a hurricane. The fort, begun during Louis-Philippe's reign, was finished in 1867 in the reign of

In 1851, a penitentiary was built on ''Petite Martinique island'', which became renamed ''Ăźlet Ă Cabrit''; in 1856 a prison reserved for women replaced it. It was destroyed in 1865 by a hurricane. The fort, begun during Louis-Philippe's reign, was finished in 1867 in the reign of

In 1969, the first hotel of the island, "Le Bois Joli" opened its doors at ''Anse Ă Cointre'' beach.

In 1972, ''les Saintes'' was equipped with a desalination plant to supply the population. However, distribution costs were too much, so the activity was abandoned in 1993 and replaced by a submarine supply piped from

In 1969, the first hotel of the island, "Le Bois Joli" opened its doors at ''Anse Ă Cointre'' beach.

In 1972, ''les Saintes'' was equipped with a desalination plant to supply the population. However, distribution costs were too much, so the activity was abandoned in 1993 and replaced by a submarine supply piped from

On 7 December 2003, the islands of ''les Saintes'', integrated into the department of Guadeloupe, participated in a referendum on the institutional evolution of that French

On 7 December 2003, the islands of ''les Saintes'', integrated into the department of Guadeloupe, participated in a referendum on the institutional evolution of that French

''Les Saintes'' is a territory of the northern hemisphere situated in

''Les Saintes'' is a territory of the northern hemisphere situated in  ''

'' ''

'' ''

'' ''

'' ''

'' ''

'' ''

'' ''

'' ''

'' ''

''

* Ceroid cacti

* prickly pear (''Opuntia ficus-indica'')

*''

* Ceroid cacti

* prickly pear (''Opuntia ficus-indica'')

*'' The sand of the beaches is dominantly white or golden, although some zones of black sand remain under the white sand. On the semi-submerged rocks, crabs can be found: Ghost crab (''Ocypode quadrata''), hermit crab (''Pagurus bernhardus''), Sally lightfoot (''Grapsus grapsus'').

The sand of the beaches is dominantly white or golden, although some zones of black sand remain under the white sand. On the semi-submerged rocks, crabs can be found: Ghost crab (''Ocypode quadrata''), hermit crab (''Pagurus bernhardus''), Sally lightfoot (''Grapsus grapsus'').

The

The

The life expectancy is 75 years for men and to 82 years for women. The average number of children per woman is 2.32.

The life expectancy is 75 years for men and to 82 years for women. The average number of children per woman is 2.32.

Fishing was for a long time the main activity of ''les Saintes'' and is still an important employment sector. The local fishermen are respected throughout the Lesser Antilles for their bravery and their "hauls".

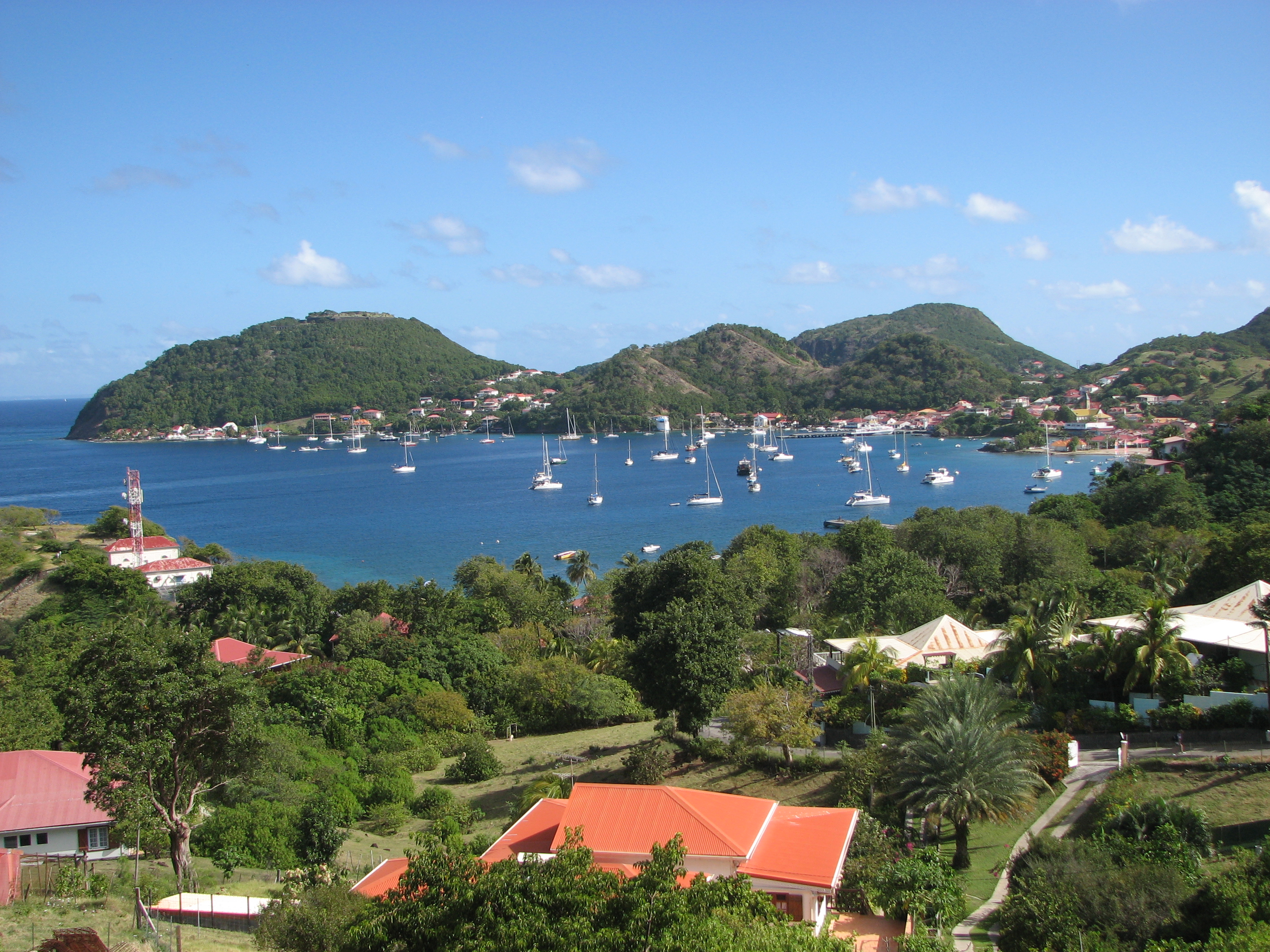

For around thirty years, ''les Saintes'' has become a famous place for tourism and this activity underpins the local economy. Terre-de-Haut welcomes numerous boats which cast anchor in the bay of les Saintes, dubbed "one of the most beautiful bays of the world". The hotel business and guest houses have spread, without disturbing this archipelago which has remained wild. The bay attracts luxury yachts, pleasure boats, cruise ships and big sailboats which cross through the Antilles. (84 stopovers of cruise for 2009) Terre-de-Haut annually receives more than 380,000 visitors who frequent businesses of the archipelago.

Agriculture remains underdeveloped on these dry islands.

An economic approach to all the activities is implemented by the National Institute for Statistics and Economic Studies (INSEE) of Guadeloupe. Economic activity remains relatively low, marked by strong disparities between Terre-de-Haut and Terre-de-Bas. The unemployment rate is 16.5% in Terre-de-Haut, and 34.5% in Terre-de-Bas (2017). The working population consists of a great majority of employees and salaried workers and a small percentage of storekeepers and craftsmen. The number of companies in the archipelago was 316 in 2015.

Fishing was for a long time the main activity of ''les Saintes'' and is still an important employment sector. The local fishermen are respected throughout the Lesser Antilles for their bravery and their "hauls".

For around thirty years, ''les Saintes'' has become a famous place for tourism and this activity underpins the local economy. Terre-de-Haut welcomes numerous boats which cast anchor in the bay of les Saintes, dubbed "one of the most beautiful bays of the world". The hotel business and guest houses have spread, without disturbing this archipelago which has remained wild. The bay attracts luxury yachts, pleasure boats, cruise ships and big sailboats which cross through the Antilles. (84 stopovers of cruise for 2009) Terre-de-Haut annually receives more than 380,000 visitors who frequent businesses of the archipelago.

Agriculture remains underdeveloped on these dry islands.

An economic approach to all the activities is implemented by the National Institute for Statistics and Economic Studies (INSEE) of Guadeloupe. Economic activity remains relatively low, marked by strong disparities between Terre-de-Haut and Terre-de-Bas. The unemployment rate is 16.5% in Terre-de-Haut, and 34.5% in Terre-de-Bas (2017). The working population consists of a great majority of employees and salaried workers and a small percentage of storekeepers and craftsmen. The number of companies in the archipelago was 316 in 2015.

* Corpus Christi: The believers follow a procession through the streets of the island with the priest who protects the

* Corpus Christi: The believers follow a procession through the streets of the island with the priest who protects the

*The ''

*The ''

archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands, or sometimes a sea containing a small number of scattered islands.

Examples of archipelagos include: the Indonesian Archi ...

of Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe (; ; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Gwadloup, ) is an archipelago and overseas department and region of France in the Caribbean. It consists of six inhabited islandsâBasse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Marie-Galante, La DĂ©sirade, and the ...

, an overseas department

The overseas departments and regions of France (french: départements et régions d'outre-mer, ; ''DROM'') are departments of France that are outside metropolitan France, the European part of France. They have exactly the same status as mainlan ...

of France. It is part of the Canton of Trois-RiviĂšres

The canton of Trois-RiviĂšres is an administrative division in the department of Guadeloupe. Its borders were modified at the French canton reorganisation which came into effect in March 2015. Its seat is in Trois-RiviĂšres.

Composition

It cons ...

and is divided into two communes: Terre-de-Haut

Terre-de-Haut (; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, TĂšdĂ©ho) is a commune in the French overseas department of Guadeloupe, including Terre-de-Haut Island and a few other small uninhabited islands of the archipelago (''les Roches PercĂ©es''; ''Ălet Ă ...

and Terre-de-Bas

Terre-de-Bas (; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, TÚdéba) is a commune in the French overseas department and region of Guadeloupe, in the Lesser Antilles. Terre-de-Bas is made up of Terre-de-Bas Island and several uninhabited islands and islets in ...

. It is in the arrondissement

An arrondissement (, , ) is any of various administrative divisions of France, Belgium, Haiti, certain other Francophone countries, as well as the Netherlands.

Europe

France

The 101 French departments are divided into 342 ''arrondissements' ...

of Basse-Terre and also in Guadeloupe's 4th constituency

The 4th constituency of Guadeloupe is a French legislative Constituency in the Overseas department of Guadeloupe. Since 2022, is represented by Ălie Califer of the Socialist Party. Guadeloupe is composed of four Constituencies.

Deputies

...

.

History

Pre-Columbian

''Les Saintes'', due to their location in the heart of the Lesser Antilles, were frequented first by Indian tribes coming fromCaribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la CaraĂŻbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De CaraĂŻben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

and Central America

Central America ( es, América Central or ) is a subregion of the Americas. Its boundaries are defined as bordering the United States to the north, Colombia to the south, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. ...

. ''Caaroucaëra'' (the Arawak

The Arawak are a group of indigenous peoples of northern South America and of the Caribbean. Specifically, the term "Arawak" has been applied at various times to the Lokono of South America and the TaĂno, who historically lived in the Greater ...

name of ''Ăles des Saintes''), although uninhabited due to the lack of spring water, were regularly visited by Arawak peoples

The Arawak are a group of indigenous peoples of northern South America and of the Caribbean. Specifically, the term "Arawak" has been applied at various times to the Lokono of South America and the TaĂno, who historically lived in the Greater ...

then Kalinagos living on the neighbourhood islands of Guadeloupe and Dominica around the 9th century. They went there to practise hunting and fishing. The archaeological remains of war axes and pottery dug up on the site of ''Anse Rodrigue's Beach'' and stored at "Fort Napoléon" museum testify the visits of these populations.

Discovery and colonisation

It was during his second expedition for America, thatChristopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, CristĂłbal ColĂłn

* pt, CristĂłvĂŁo Colombo

* ca, CristĂČfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

discovered the small archipelago, on 4 November 1493. He named them "Los Santos", in reference to All Saints' Day

All Saints' Day, also known as All Hallows' Day, the Feast of All Saints, the Feast of All Hallows, the Solemnity of All Saints, and Hallowmas, is a Christian solemnity celebrated in honour of all the saints of the church, whether they are know ...

which had just been celebrated. Around 1523, along with its neighbours, these islands, which were devoid of precious metals, were abandoned by the Spanish who favoured the Greater Antilles and the South American continent.

On 18 October 1648, a French expedition led by Sir du MĂ©, annexed ''les Saintes'', already under English influence, at the request of the governor of Guadeloupe

(Dates in italics indicate ''de facto'' continuation of office)

Note: currently, the prefect is not the true departmental head, which is the President of the General Council. The prefect is merely the representative of the national government. ...

, Charles Houël. From 1649, the islands became a colony exploited by the French West India Company which tried to establish agriculture. However, the inhospitable ground and the aridity of ''"Terre-de-Haut"'' halted this activity, though it persisted for a while on ''Terre-de-Bas'', which was wetter and more fertile, under the orders of Sir Hazier du Buisson from 1652.

In 1653, the Kalinagos slaughtered the French troops in Marie-Galante. Sir du MĂ© decided to respond to this attack by sending a punitive expedition against the tribes in Dominica. Following these events, the Kalinagos, invaded ''les Saintes'' to take revenge. Sir Comte de l'Etoile tried to repel the Caribs who were definitively chased away in 1658. In the name of the King of France, ''les Saintes'' were acquired in the royal domain by Jean-Baptiste Colbert

Jean-Baptiste Colbert (; 29 August 1619 â 6 September 1683) was a French statesman who served as First Minister of State from 1661 until his death in 1683 under the rule of King Louis XIV. His lasting impact on the organization of the countr ...

when the French West India Company was dissolved in 1664.

On 4 August 1666, while the English were attacking the archipelago, their fleet was routed by the passage of a hurricane

A tropical cyclone is a rapidly rotating storm system characterized by a low-pressure center, a closed low-level atmospheric circulation, strong winds, and a spiral arrangement of thunderstorms that produce heavy rain and squalls. Depend ...

and some British who besieged this "Gibraltar of the Antilles" were quickly expelled by the troops of Sir du Lion and Sir Desmeuriers, helped by the Caribs. The English surrendered on 15 August 1666, the day of the Assumption of Mary

The Assumption of Mary is one of the four Marian dogmas of the Catholic Church. Pope Pius XII defined it in 1950 in his apostolic constitution ''Munificentissimus Deus'' as follows:

We proclaim and define it to be a dogma revealed by Go ...

, and a Te Deum

The "Te Deum" (, ; from its incipit, , ) is a Latin Christian hymn traditionally ascribed to AD 387 authorship, but with antecedents that place it much earlier. It is central to the Ambrosian hymnal, which spread throughout the Latin Chur ...

was intoned at the request of Sir du Lion who founded an annual remembrance in honour to this victory - this is celebrated ardently on the island of Terre-de-Haut to this day. Our-Lady-of-Assumption became the Patron saint of the parish.

To protect the French colonies of the area, the English were repelled to Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of the Americas, and the most easterly of the Caribbean Islands. It occupies an area of and has a population of about 287,000 (2019 estimate). ...

by the governor of Santo Domingo

, total_type = Total

, population_density_km2 = auto

, timezone = AST (UTC â4)

, area_code_type = Area codes

, area_code = 809, 829, 849

, postal_code_type = Postal codes

, postal_code = 10100â10699 (Distrito Nacional)

, websi ...

, Jean-Baptiste Ducasse in 1691.

18th Century

From 1759 to 1763, the British took possession of Les Saintes and a part of Guadeloupe. Les Saintes were restored to the Kingdom of France only after the signature of theTreaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

on 10 February 1763, by which France gave up Ăle Royale

The Salvation Islands (french: Ăles du Salut, so called because the missionaries went there to escape plague on the mainland; sometimes mistakenly called Safety Islands) are a group of small islands of volcano, volcanic origin about off the coa ...

, Isle Saint-Jean

Isle Saint-Jean was a French colony in North America that existed from 1713 to 1763 on what is today Prince Edward Island.

History

After 1713, France engaged in a reaffirmation of its territory in Acadia. Besides the construction of Louisbou ...

, Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17th and early ...

and Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

, the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lakes ...

region and the left bank of the Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

to the British.

To prevent further British ambitions, King Louis XVI ordered the construction of fortifications on Les Saintes. Thus began the construction of "Fort Louis" on the Mire Hill, "Fort de la Reine" on Petite Martinique island, the watchtowers of "Modele tower" on Chameau Hill (the top of the archipelago, 309 m), the artillery batteries of Morel Hill and Mouillage Hill, in 1777.

On 12 April 1782, after the military campaign of January in Basseterre on the island of Saint Christopher, the French fleet of

On 12 April 1782, after the military campaign of January in Basseterre on the island of Saint Christopher, the French fleet of Comte de Grasse

''Comte'' is the French, Catalan and Occitan form of the word 'count' (Latin: ''comes''); ''comté'' is the Gallo-Romance form of the word 'county' (Latin: ''comitatus'').

Comte or Comté may refer to:

* A count in French, from Latin ''comes''

* A ...

, which aimed to capture British Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

, left Martinique

Martinique ( , ; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Matinik or ; Kalinago: or ) is an island and an overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France. An integral part of the French Republic, Martinique is located in th ...

and headed towards the archipelago of ''les Saintes'', where it arrived in the evening. Caught in the Dominica Passage by the British and inferior in number, it was engaged and defeated by the ships of the line of George Brydges Rodney

Admiral George Brydges Rodney, 1st Baron Rodney, KB ( bap. 13 February 1718 â 24 May 1792), was a British naval officer. He is best known for his commands in the American War of Independence, particularly his victory over the French at the ...

aboard the ''Formidable'' and Samuel Hood aboard the ''Barfleur''. According to legend, after he had fired the last of the ammunition of his carronade

A carronade is a short, smoothbore, cast-iron cannon which was used by the Royal Navy. It was first produced by the Carron Company, an ironworks in Falkirk, Scotland, and was used from the mid-18th century to the mid-19th century. Its main func ...

s, de Grasse fired off his silverware. In a little more than five hours, 2,000 French sailors and soldiers were killed and wounded, and 5,000 men and 4 ships of the line captured and one ship of the line sunk. The defeat resulted in ''Ăles des Saintes'' coming under British rule for twenty years.

In 1794, France's National Convention

The National Convention (french: link=no, Convention nationale) was the parliament of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for the rest of its existence during the French Revolution, following the two-year National ...

, represented by Victor Hugues, tried to reconquer the islands but succeeded in occupying them only temporarily, the islands being recaptured away by the powerful British vessel '' Queen Charlotte''.

19th Century

In 1802, the First French Empire under Napoleon launched a successful operation to recapture the archipelago from the British. On 14 April 1809, the British fleet of Admiral Sir Alexander Forrester Inglis Cochrane reconquered the archipelago. Three young people from ''les Saintes'', Mr. Jean Calo, Mr. Cointre and Mr. Solitaire, succeeded in guiding three French vessels ('' Hautpoult'', '' Courageux'', and '' Félicité'') commanded by the infantry division of Admiral Troude which were caught unawares inside the bay and helped them to escape back to France through the North Passage called ''"La baleine"''. These men were decorated with the Legion of Honour for their actions. Guadeloupe island was also conquered on 26 February 1810 by the British.. The French Governor

Guadeloupe island was also conquered on 26 February 1810 by the British.. The French Governor Jean Augustin Ernouf

Jean Augustin Ernouf (Manuel Louis Jean Augustin or Auguste Ernouf) (29 August 1753 â 12 September 1827) was a French general and colonial administrator of the French Revolutionary Wars, Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars. He demonstrated moderat ...

was forced to capitulate.

By a bilateral treaty signed in Stockholm

Stockholm () is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in Sweden by population, largest city of Sweden as well as the List of urban areas in the Nordic countries, largest urban area in Scandinavia. Approximately 980,000 people liv ...

on 3 March 1813, Sweden promised the British that they would make a common front against Napoleon's France. In return, the British would have to support the ambitions of Stockholm on Norway. Pragmatically, Karl XIV Johan indeed understood that it was time for Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

to abandon Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of B ...

(lost in 1809) and to spread the kingdom westward. Besides, Great Britain offered the colony of Guadeloupe to Karl XIV Johan personally to seal this new alliance.

Under the Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

signed on 30 May 1814, the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

accepted to give Guadeloupe back to France. King Karl XIV Johan of Sweden retroceded Guadeloupe to France and earned in exchange the recognition of the Union of Sweden and Norway

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

and the payment to the Swedish royal house of 24 million gold francs in compensation (Guadeloupe Fund The Guadeloupe Fund ( sv, Guadeloupefonden) was established by Sweden's Riksdag of the Estates in 1815 for the benefit of Crown Prince and Regent Charles XIV John of Sweden, (Swedish: ''Karl XIV Johan'') also known as ''Jean Baptiste Jules Bernado ...

). However, the French only came back to ''les Saintes'' on 5 December, when the General Leith, commander in chief of forces in the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

and governor of the Leeward Isles accepted it.

The new governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

of Guadeloupe and dependencies, the Commodore Sir '' Comte de Linois'' and his deputy governor Sir ''EugĂšne-Ădouard Boyer, Baron de Peyreleau'', sent by Louis XVIII

Louis XVIII (Louis Stanislas Xavier; 17 November 1755 â 16 September 1824), known as the Desired (), was King of France from 1814 to 1824, except for a brief interruption during the Hundred Days in 1815. He spent twenty-three years in ...

to repossess the colony were quickly disturbed by the return of Napoleon I

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 â 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

in April 1815 (Hundred Days

The Hundred Days (french: les Cent-Jours ), also known as the War of the Seventh Coalition, marked the period between Napoleon's return from eleven months of exile on the island of Elba to Paris on20 March 1815 and the second restoration ...

). A conflict broke out between Bonapartists and monarchists.

On 19 June 1815, Sir ''Comte de Linois'' (monarchist) forced by Sir ''Boyer de Peyreleau'' (Bonapartist), rejoined the Bonapartists and sent away a British frigate dispatched by the governor of the Windward Islands in Martinique, Sir ''Pierre René Marie, Comte de Vaugiraud'' to bring back the monarchical order of Louis XVIII.

Sir ''Comte de Vaugiraud'' relieved them of their duties and the British took the offensive.

Les Saintes were captured again by the crown of Great Britain on 6 July 1815, Marie-Galante on 18 July and Guadeloupe on 10 August.

Despite the defeat of the Bonapartists and the restoration of Louis XVIII, on the request of the slave planter of Guadeloupe (favourable to the British because of their abolitionist minds) and by order of General Leith the British stayed to purge the colony of Bonapartism. The Bonapartists were judged and deported.

The British troops left the colony to the French on 22 July 1816. Sir ''Antoine Philippe, Comte de Lardenoy'' was named by the King, Governor and Administrator of Guadeloupe and dependencies on 25 July 1816.

It was in 1822 that the ''Chevalier de Fréminville'' legend was born. Christophe-Paulin de la Poix, named ''Chevalier de Fréminville'', a sailor and naturalist in a military campaign to ''les Saintes'' aboard the vessel ''La Néréïde'' shared a dramatic love story with a ''Saintoise'' named Caroline (known as "Princess Caroline" in reference to her legendary beauty). She committed suicide down from the artillery battery

In military organizations, an artillery battery is a unit or multiple systems of artillery, mortar systems, rocket artillery, multiple rocket launchers, surface-to-surface missiles, ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, etc., so grouped to fac ...

of Morel

''Morchella'', the true morels, is a genus of edible sac fungi closely related to anatomically simpler cup fungi in the order Pezizales (division Ascomycota). These distinctive fungi have a honeycomb appearance due to the network of ridges with ...

Hill which bears her name today, thinking her beloved man dead at Saint-Christopher, not seeing him come back from campaign. This condemned the knight to madness; taken by sorrow, he took Caroline's clothes and returned to Brest

Brest may refer to:

Places

*Brest, Belarus

**Brest Region

**Brest Airport

**Brest Fortress

*Brest, Kyustendil Province, Bulgaria

*BĆest, Czech Republic

*Brest, France

**Arrondissement of Brest

**Brest Bretagne Airport

** ChĂąteau de Brest

*Brest, ...

, where he stayed until the end of his days. Engravings and narratives are kept at Fort Napoléon museum.

In 1844, during Louis Philippe I's reign, the construction of a fort began on the ruins of the old Fort Louis. The fortification was built to the technique of Vauban to protect the archipelago against a possible reconquest.

Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

who baptised it ''Fort Napoléon'' in honour of his uncle, Napoleon I

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 â 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

. ''Fort de la Reine'' was renamed ''Fort Joséphine'' at the same time. A lazaretto

A lazaretto or lazaret (from it, lazzaretto a diminutive form of the Italian word for beggar cf. lazzaro) is a quarantine station for maritime travellers. Lazarets can be ships permanently at anchor, isolated islands, or mainland buildings ...

was opened in 1871 instead of the penitentiary.

On 9 August 1882, under Jules Grévy's mandature, at the request of the municipal councillors and following the church's requirements asking for the creation of Saint-Nicholas's parish, the municipality of Terre-de-Bas was created, separating from Terre-de-Haut which also became a municipality. This event marked the end of the municipality of ''les Saintes''. The patron saint's day of Terre-de-Bas was then established on 6 December, St Nicholas'Day.

In 1903, the military and disciplinary garrisons were definitively given up. It was the end of the "Gibraltar of the Antilles", but in honour of its military past, the ships of the navy made a traditional stopover. In 1906, the cruiser '' Duguay-Trouin'' stopped over at ''les Saintes''. In September 1928, ''les Saintes'', like its neighbouringislands of Guadeloupe, were violently struck by a strong cyclone which destroyed an important part of the municipal archives. From 1934 the first inns were built, which marked the beginning of visits to the island by the outside world.

Dissidence and French overseas departmentalisation

In June 1940, answering the appeal of General de Gaulle, the French Antilles entered into aResistance movement

A resistance movement is an organized effort by some portion of the civil population of a country to withstand the legally established government or an occupying power and to disrupt civil order and stability. It may seek to achieve its objective ...

against Vichy

Vichy (, ; ; oc, VichĂši, link=no, ) is a city in the Allier Departments of France, department in the Auvergne-RhĂŽne-Alpes region of central France, in the historic province of Bourbonnais.

It is a Spa town, spa and resort town and in World ...

regime and Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

collaboration. They called it ''Dissidence''. The governor, appointed by Marshal Philippe PĂ©tain, Constant Sorin, was in charge of administering Guadeloupe and its dependencies. ''Les Saintes'' became the Mecca of ''dissidence''.

The French Antilles were affected by the arbitrary power and the authoritarian ideology of PĂ©tain and Pierre Laval

Pierre Jean Marie Laval (; 28 June 1883 â 15 October 1945) was a French politician. During the Third Republic, he served as Prime Minister of France from 27 January 1931 to 20 February 1932 and 7 June 1935 to 24 January 1936. He again occu ...

. The ministry of the colonies of Vichy, by its colonial representatives Mr. Constant Sorin and Admiral Georges Robert, High Commissioner of France, applied its whole legislation including the anti-semitic laws. A strong police state was set up and any resistance was actively repressed. Seeing the rallying of the French Antilles to the regime of Vichy, the islands were embargoed by the British-American forces. Cut from any relationship (in particular the import of fuels and foodstuffs) with France, ''Constant Sorin'' set up a policy of rationing and self-sufficiency, by diversifying and increasing the local production. It was a period of resourcefulness.

On 27 October 1940, the General council General council may refer to:

In education:

* General Council (Scottish university), an advisory body to each of the ancient universities of Scotland

* General Council of the University of St Andrews, the corporate body of all graduates and senio ...

was dissolved and the Mayors of Guadeloupe and its dependencies were relieved of their duties and replaced by prominent citizens appointed by the Vichy government. The mayor of Terre-de-Haut, Théodore Samson, was replaced by a Béké

Béké or beke is an Antillean Creole term to describe a descendant of the early European, usually French, settlers in the French Antilles.

Etymology

The origin of the term is unclear, although it is attested to in colonial documents from as early ...

of Martinique, Mr. de Meynard. Popular gatherings were forbidden and freedom of expression was banned by the regime. A passive resistance to Vichy and its local representatives was organised from 1940 to 1943. More than 4,000 French West Indians left their islands, at the risk of their life, to join the nearby British colonies. Then they rallied the Free French Forces, first by undertaking military training in the United States, Canada or Great Britain. At the same time, '' Fort Napoléon'' became a political jail where the dissidents were locked. The ''Saintois'' boarded their traditional ''Saintoise The saintoise (; Antillean Creole: ''Sentwaz'') or ''canot saintois'' (literally: dinghy from les Saintes) is a fishing boat without a deck, traditionally maneuverable with the sail or the ream. It is native to the les Saintes archipelago where it ...

'' to the Guadeloupean coast to pick up the volunteers for dissidence departure. Then, they were sailed through Dominica Passage

Dominica Passage is a strait in the Caribbean. It separates the islands of Dominica, from Marie-Galante, Guadeloupe. It is a pathway from the Caribbean Sea into the Atlantic Ocean.Ana G. LĂłpez MartĂInternational Straits: Concept, Classification ...

, avoiding the cruisers and patrol boats of Admiral Robert.

In March 1943, the French Guyanese rebelled against the regime and rallied the allies. French West Indians followed the movement and in April, May and June 1943, a civil movement of resistance took weapons and rebelled against Vichy's administration. In Martinique

Martinique ( , ; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Matinik or ; Kalinago: or ) is an island and an overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France. An integral part of the French Republic, Martinique is located in th ...

, the marines of Fort-de-France

Fort-de-France (, , ; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Fodfwans) is a Communes of France, commune and the capital city of Martinique, an overseas department and region of France located in the Caribbean. It is also one of the major cities in the ...

also rebelled against Admiral Robert.

With shortages from the embargo making life more and more difficult, Admiral Robert sent to the Americans his will to capitulate, seeking the end of the blockade, on 30 June 1943.

On 3 July 1943, the American admiral John Howard Hoover came to Martinique

Martinique ( , ; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Matinik or ; Kalinago: or ) is an island and an overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France. An integral part of the French Republic, Martinique is located in th ...

and on 8 July 1943, the American government required an unconditional surrender to the authority of the French Committee of National Liberation

The French Committee of National Liberation (french: Comité français de Libération nationale) was a provisional government of Free France formed by the French generals Henri Giraud and Charles de Gaulle to provide united leadership, organiz ...

and offered asylum to Admiral Robert.

On 15 July 1943, Governor Constant Sorin and Admiral Robert were relieved of their duties by Henri Hoppenot

Henri Hoppenot (; October 25, 1891 â August 10, 1977) was a French diplomat and the last commissioner-general in Indochina (1955â1956). He also served as the French president of the United Nations Security Council from 1952 to 1955.

In August ...

, ambassador of Free French Forces, and the French Antilles also joined the allies. Admiral Robert left the island the same day for the United States.

Many of the dissidents were sent to the North African fronts and participated in Operation Dragoon

Operation Dragoon (initially Operation Anvil) was the code name for the landing operation of the Allied invasion of Provence (Southern France) on 15August 1944. Despite initially designed to be executed in conjunction with Operation Overlord, th ...

beside the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

.

On 19 March 1946, the President of the Provisional Government of the French Republic

The Provisional Government of the French Republic (PGFR; french: Gouvernement provisoire de la République française (''GPRF'')) was the provisional government of Free France between 3 June 1944 and 27 October 1946, following the liberation ...

promulgated the law of departmentalisation, which set up the colonies of Guadeloupe, Martinique, La RĂ©union and French Guiana

French Guiana ( or ; french: link=no, Guyane ; gcr, label=French Guianese Creole, Lagwiyann ) is an overseas departments and regions of France, overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France on the northern Atlantic ...

, as Overseas Department

The overseas departments and regions of France (french: départements et régions d'outre-mer, ; ''DROM'') are departments of France that are outside metropolitan France, the European part of France. They have exactly the same status as mainlan ...

s. From then on, ''les Saintes'', Marie-Galante, La Désirade, Saint-Barthélemy and the French side of Saint-Martin were joined, as municipalities, with Guadeloupe island into the new department of Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe (; ; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Gwadloup, ) is an archipelago and overseas department and region of France in the Caribbean. It consists of six inhabited islandsâBasse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Marie-Galante, La DĂ©sirade, and the ...

. The colonial status up until then was replaced by a policy of assimilation to the rest of the metropolitan territory.

In 1957, in the country's municipal elections, the mysterious death of the mayor of Terre-de-Haut, Théodore Samson, while he was in the office of the National Gendarmerie provoked an uprising of the population against the institution which was attacked with conches and stones. The revolt lasted two days before being quelled by the military and police reinforcements from Guadeloupe whom dissipated the crowd, looked for and arrested the insurgents (mainly of the "Pineau" family, Théodore Samson's political support). A frigate of the navy stayed a few weeks in the harbour of ''les Saintes'' to restore the peace.

Development of tourism

In 1963, the archipelago welcomedSS France

SS ''France'' may refer to:

* , a French steamship chartered by the French Government during the Crimean War

* , a French liner sunk in 1915

* , a French liner scrapped in 1936, and is the only French ship to be one of the four-funnel liners

* , a ...

during its first transatlantic voyage, which moored in the bay like the Italian, Swedish, Norwegian and American cruise ships which continue today to frequent the small archipelago. The era of the luxury yacht began.

Capesterre-Belle-Eau

Capesterre-Belle-Eau is a commune in the French overseas region and department of Guadeloupe, in the Lesser Antilles. It is located in the south-east of Basse-Terre Island. Capesterre-Belle-Eau covers an area of 103.3 km2 (39.884 sq mi). Th ...

. Similarly, for electricity, although an emergency power plant of fuel oil remains active on the island of Terre-de-Bas.

In 1974, ''Fort Napoléon'' was restored by the Club of the Old Manor House and the Saintoise Association of the Protection of Heritage (A.S.P.P), and accommodated a museum of the history and heritage of ''les Saintes''. It became the most visited monument in the archipelago. In 1984, the Jardin Exotique de Monaco

The Jardin Exotique de Monaco ( French for "exotic garden of Monaco") is a botanical garden located on a cliffside in Monaco.

History

The succulent plants were brought back from Mexico in the late 1860s. By 1895, Augustin Gastaud, who served as ...

and Jardin botanique du Montet The Jardin botanique du Montet (27 hectares), sometimes also called the Jardin botanique de Nancy, is a major botanical garden operated by the ''Conservatoire et Jardins Botaniques de Nancy''. It is located at 100, rue du Jardin Botanique, Villers-l ...

sponsored the creation of an exotic garden on the covered way of ''Fort Napoléon''.

In 1990, for "La route des fleurs" ("The road of flowers", a national contest between the municipalities of France which rewards the most flowery municipality), Terre-de-Haut was coupled with the city of Baccarat, famous for its crystal glass-making.

At the same time, the island of Terre-de-Haut was rewarded by an "environment Oscar" (a French award to municipalities protecting their heritage and environment) for the conservation of its heritage and natural housing environment.

On 14 May 1991, the sites of the ''Bay of Pompierre'' and ''Pain de Sucre

Pain is a distressing feeling often caused by intense or damaging stimuli. The International Association for the Study of Pain defines pain as "an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, ...

'' were classified as protected spaces according to the law of 2 May 1930.

In 1994, the tourism office of ''les Saintes'' was created. The island welcomes approximately 300,000 visitors a year and became a destination appreciated by cruises and sailors.

On 20 May 1994, during his travel in the Antilles

The Antilles (; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Antiy; es, Antillas; french: Antilles; nl, Antillen; ht, Antiy; pap, Antias; Jamaican Patois: ''Antiliiz'') is an archipelago bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the south and west, the Gulf of Mex ...

, the Prime Minister of France, Ădouard Balladur, made an official visit to Terre-de-Haut.

In May 2001, ''les Saintes'' joined the Club of the Most Beautiful Bays of the World

Club may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Club (magazine), ''Club'' (magazine)

* Club, a ''Yie Ar Kung-Fu'' character

* Clubs (suit), a suit of playing cards

* Club music

* "Club", by Kelsea Ballerini from the album ''kelsea''

Brands a ...

.

2004 earthquake

On 21 November 2004, the islands of ''les Saintes'' were struck by an earthquake of magnitude 6.3. It was an intraplate earthquake situated on a system of normal faults going from ''les Saintes'' to the north of Dominica. These faults are globally directed 135° (north-west to south-east), with dip north-east (Roseau fault, Ilet fault, Colibri fault, Marigot Fault) or south-west (Souffleur fault, Rodrigues fault, Redonda fault). These faults bound zones of rifts corresponding to an extension located on Roseau volcano (an inactive submarine volcano). The epicentre was offshore, located between the island of Dominica and ''les Saintes'' archipelago, at approximately 15°47'N 61°28'W, on Souffleur fault. The depth of the focus is located on the earth's crust, and is superficial, about . The concussions of the main shock and the numerous aftershocks were powerful, reaching an intensity of VIII (important structural damage) on the MSK scale. Damage to the most vulnerable properties in les Saintes, in Trois-RiviÚres (Guadeloupe) and in the North of Dominica was considerable. In Trois-RiviÚres, a collapsed wall killed a sleeping girl and seriously hurt her sister. In ''les Saintes'', even though no-one was killed or badly wounded, many were traumatised by the strong and numerous aftershocks.Political and institutional evolution

On 7 December 2003, the islands of ''les Saintes'', integrated into the department of Guadeloupe, participated in a referendum on the institutional evolution of that French

On 7 December 2003, the islands of ''les Saintes'', integrated into the department of Guadeloupe, participated in a referendum on the institutional evolution of that French Overseas Department

The overseas departments and regions of France (french: départements et régions d'outre-mer, ; ''DROM'') are departments of France that are outside metropolitan France, the European part of France. They have exactly the same status as mainlan ...

and rejected it by a majority of "No".

During the 2009 French Caribbean general strikes

The 2009 French Caribbean general strikes began in the French overseas region of Guadeloupe on 20 January 2009, and spread to neighbouring Martinique on 5 February 2009. Both islands are located in the Lesser Antilles of the Caribbean. The gener ...

, ''les Saintes'' did not get involved in the movement and were only moderately affected: the supply of stores was very perturbed like other places in Guadeloupe, but these strikes mostly concerned small and medium enterprises

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) or small and medium-sized businesses (SMBs) are businesses whose personnel and revenue numbers fall below certain limits. The abbreviation "SME" is used by international organizations such as the World Bank ...

(SMEs) (weakly presented on these islands). The maritime transport companies tried hard to find some Gasoil to assure most of the connections, and the Guadeloupean tourism was partially transferred to ''les Saintes''.

Nicolas Sarkozy

Nicolas Paul Stéphane Sarközy de Nagy-Bocsa (; ; born 28 January 1955) is a French politician who served as President of France from 2007 to 2012.

Born in Paris, he is of Hungarian, Greek Jewish, and French origin. Mayor of Neuilly-sur-Se ...

declared, at the end of the conflict, the opening of ''Ătats-GĂ©nĂ©raux de l'Outre-mer'' ("Estates-general of the Overseas"). Several study groups were created, one of which looked into the local governance, brought to conceive an institutional modification project or a new status of Guadeloupe with or without emancipation of its last dependencies. The conferences of the "southern islands" (name of the last dependencies of Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe (; ; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Gwadloup, ) is an archipelago and overseas department and region of France in the Caribbean. It consists of six inhabited islandsâBasse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Marie-Galante, La DĂ©sirade, and the ...

) (Marie Galante, ''les Saintes'' and la DĂ©sirade) were opened in parallel. Problems common to these islands were exposed in six study groups: the equality of opportunity, the territorial continuity, the local governance, the local economic development, the insertion by the activity and tourism.

On 12 May 2009, the French overseas Minister, Yves JĂ©go

Yves Jégo (; born 17 April 1961) is a French politician. He was ''Deputy (legislator), député'' for the Seine-et-Marne's 3rd constituency, third constituency of Seine-et-Marne in the National Assembly (France), National Assembly from 2002 ...

, at the end of these conferences, made an official visit to ''les Saintes'' for the seminary of the southern islands of Guadeloupe. He took into account the identical reality and the political hopes of these islands, to improve the territorial continuity, to reduce the effects of the double-insularity, the abolition of the dependence to Guadeloupe, national representation, the development of the attractiveness of the labour pool in the zone, the fight against the depopulation, the tax system and the expensive life. For the moment he announced the signature of a contract baptised COLIBRI ("hummingbird"; Contract for the Employment and the Local Initiatives in the Regional Pond of the Southern Islands of Guadeloupe), a convention of the Grouping of Public Interest for Arrangement and Development (GIPAD) and a proposition of statutory evolution in final, like the study group of governance, the collective of the southern islands of Guadeloupe and the elected representatives asked it, on the basis of the article 74 of the French constitution.

''Les Saintes'', like Marie Galante, aspires to the creation of an Overseas collectivity for each entity of the Southern islands, or combining the three dependences, on the same plan as the ''old northern islands of Guadeloupe'' (Saint-Barthélemy and Saint-Martin). Marie-Luce Penchard

Marie-Luce Penchard (born 14 February 1959, in Gourbeyre) is a French politician from Guadeloupe and member of the UMP. She is the daughter of Lucette Michaux-Chevry, the historical leader of the right in Guadeloupe and the former President of ...

, native of Guadeloupe, brought in a governmental portfolio for overseas on 23 June 2009 and appointed Overseas Minister on 6 November 2009, seems wildly opposed to the initial project of her predecessor and delays applying it.

Geography

Les Saintes is a volcanic archipelago fully encircled by shallow reefs. It arose from the recent volcanic belt of the Lesser Antilles from thePliocene

The Pliocene ( ; also Pleiocene) is the epoch in the geologic time scale that extends from 5.333 million to 2.58Epoch

In chronology and periodization, an epoch or reference epoch is an instant in time chosen as the origin of a particular calendar era. The "epoch" serves as a reference point from which time is measured.

The moment of epoch is usually decided by ...

. It is composed of rocks appeared on the Tertiary

Tertiary ( ) is a widely used but obsolete term for the geologic period from 66 million to 2.6 million years ago.

The period began with the demise of the non-avian dinosaurs in the CretaceousâPaleogene extinction event, at the start ...

age between (4.7 to 2 million years ago). By origin, it was a unique island that the tectonic

Tectonics (; ) are the processes that control the structure and properties of the Earth's crust and its evolution through time. These include the processes of mountain building, the growth and behavior of the strong, old cores of continents k ...

and volcanic

A volcano is a rupture in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often found where tectonic plates a ...

earthquakes separate to create an archipelago due to the subduction zone between the South American plate, the North American plate and the Caribbean plate.

The total surface is . The archipelago has approximately of coast and its highest hill, Chameau ("Camel"), reaches about .

Islands

It is composed of two very mountainous inhabited islands,Terre-de-Haut Island

Terre-de-Haut Island (; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, TĂšdĂ©ho; also formerly known as ''Petite Martinique'') is the easternmost island in the Ăles des Saintes , part of the archipelago of Guadeloupe. Like name of neighboring Terre-de-Bas, nam ...

and Terre-de-Bas Island

Terre-de-Bas Island (officially in French: Terre-de-Bas des Saintes ''(literally: Lowland of les Saintes)'') is an island in the Ăles des Saintes archipelago, in the Lesser Antilles.

It belongs to the communes of France, commune (municipality) of ...

. Grand-Ălet is an uninhabited protected area. There are six other uninhabited Ăźslets.

Les Roches Percées

An uninhabited island characterized by high rocks abrupt which the erosion dug impressive fractures by which the sea rushes. These faults are at the origin of the naming of the island. It is a natural site classified by French law. The entry and the anchorage of motorboats, as well as sailing boats are strictly forbidden.Ălet Ă Cabrit

At at the northwest ofTerre-de-Haut Island

Terre-de-Haut Island (; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, TĂšdĂ©ho; also formerly known as ''Petite Martinique'') is the easternmost island in the Ăles des Saintes , part of the archipelago of Guadeloupe. Like name of neighboring Terre-de-Bas, nam ...

, closing partially the Bay of les Saintes. It is approximately from east to west and from north to south. Its highest mount up to , Morne Joséphine. It creates two passages into the Bay of les Saintes, la Baleine passage to the East and Pain de Sucre passage in the South, which constitute both access roads to the harbours of Mouillage and Fond-du-Curé.

The Pain de sucre peninsula, with the height of () is linked to Terre-de-Haut by an isthmus. It is between two beaches. It is constituted by an alignment of columnar basalt. It is the site of the ruins of the lazaretto and Joséphine Fort''.''

La Redonde

An uninhabited rock at South ofTerre-de-Haut Island

Terre-de-Haut Island (; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, TĂšdĂ©ho; also formerly known as ''Petite Martinique'') is the easternmost island in the Ăles des Saintes , part of the archipelago of Guadeloupe. Like name of neighboring Terre-de-Bas, nam ...

. It is the northern extremity of Grand-Ălet Passage. It is very difficult to berth on it, the swell there is constantly bad.

La Coche

At west of Grand-Ălet from which it is separated from it by the Passe des Dames, and on the east of les Augustins by the Passe des Souffleurs. It is about in wide and long. It spreads out in the length from the southeast headland to the northwest headland and is characterized by a coast of abrupt cliffs towardsDominica Passage

Dominica Passage is a strait in the Caribbean. It separates the islands of Dominica, from Marie-Galante, Guadeloupe. It is a pathway from the Caribbean Sea into the Atlantic Ocean.Ana G. LĂłpez MartĂInternational Straits: Concept, Classification ...

and a sandy hillside opening on Terre-de-Haut Island.

Les Augustins

A small group of rocks near la Coche from which they are separated by the Passe des Souffleurs. They are separated from Terre-de-Bas Island by the Southwest Passage, a major shipping lane. The Rocher de la Vierge, is named for the Immaculate Conception.Le Pùté

An island in shape of a high plateau at of the northern headland ofTerre-de-Bas Island

Terre-de-Bas Island (officially in French: Terre-de-Bas des Saintes ''(literally: Lowland of les Saintes)'') is an island in the Ăles des Saintes archipelago, in the Lesser Antilles.

It belongs to the communes of France, commune (municipality) of ...

, called Pointe à Vache. It opens the Pain de Sucre Passage, the main shipping lane to access to the Bay of les Saintes by the North. Near the islands, there is an exceptional dive site called sec Pùté. It is a submarine mountain, which the base belongs at less deep and the top at less than below sea level. The maritime conditions make this dive difficult and the level 2 is required. The place abounds in a large quantity of diversified fishes, sea turtles, sea fans, corals, gorgonians, lobsters and shellfishes which appropriate the marine domain, around three rock peaks which form the top of the mountain. Fishing of fishes and shells is regulated or forbidden for certain species.

Location

North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

, in the Caribbean islands

Almost all of the Caribbean islands are in the Caribbean Sea, with only a few in inland lakes. The largest island is Cuba. Other sizable islands include Hispaniola, Jamaica, Puerto Rico and Trinidad and Tobago. Some of the smaller islands are re ...

, between the Tropic of Cancer

The Tropic of Cancer, which is also referred to as the Northern Tropic, is the most northerly circle of latitude on Earth at which the Sun can be directly overhead. This occurs on the June solstice, when the Northern Hemisphere is tilted toward ...

and the Equator

The equator is a circle of latitude, about in circumference, that divides Earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, halfway between the North and South poles. The term can als ...

. It is positioned at 15°51' North, the same latitude as Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is bo ...

or Honduras

Honduras, officially the Republic of Honduras, is a country in Central America. The republic of Honduras is bordered to the west by Guatemala, to the southwest by El Salvador, to the southeast by Nicaragua, to the south by the Pacific Oce ...

, and at 61°36' West, the same longitude as Labrador

, nickname = "The Big Land"

, etymology =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Canada

, subdivision_type1 = Province

, subdivision_name1 ...

and the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouzet ...

.

This locality places the archipelago at from metropolitan France; at from the southeast of Florida, at from the coast of South America, and exactly at the heart of the arc of the Lesser Antilles

The Lesser Antilles ( es, link=no, Antillas Menores; french: link=no, Petites Antilles; pap, Antias Menor; nl, Kleine Antillen) are a group of islands in the Caribbean Sea. Most of them are part of a long, partially volcanic island arc betwe ...

.

''Les Saintes'' lies immediately south of the island of Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe (; ; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Gwadloup, ) is an archipelago and overseas department and region of France in the Caribbean. It consists of six inhabited islandsâBasse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Marie-Galante, La DĂ©sirade, and the ...

and west of Marie-Galante. It is separated from Guadeloupe by '' Les Saintes Passage'' and from the north of Dominica

Dominica ( or ; Kalinago: ; french: Dominique; Dominican Creole French: ), officially the Commonwealth of Dominica, is an island country in the Caribbean. The capital, Roseau, is located on the western side of the island. It is geographically ...

by the ''Dominica Passage

Dominica Passage is a strait in the Caribbean. It separates the islands of Dominica, from Marie-Galante, Guadeloupe. It is a pathway from the Caribbean Sea into the Atlantic Ocean.Ana G. LĂłpez MartĂInternational Straits: Concept, Classification ...

''.

* Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

, at ''

* Central America

Central America ( es, América Central or ) is a subregion of the Americas. Its boundaries are defined as bordering the United States to the north, Colombia to the south, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. ...

, at ''

* France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, at ''

* Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, RepĂșblica Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in th ...

, at ''

* New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, at ''

* Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after SĂŁo Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a b ...

, at ''

* Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of the Americas, and the most easterly of the Caribbean Islands. It occupies an area of and has a population of about 287,000 (2019 estimate). ...

, at ''

* Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and Unincorporated ...

, at ''

* Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe (; ; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Gwadloup, ) is an archipelago and overseas department and region of France in the Caribbean. It consists of six inhabited islandsâBasse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Marie-Galante, La DĂ©sirade, and the ...

, at ''

* Dominica

Dominica ( or ; Kalinago: ; french: Dominique; Dominican Creole French: ), officially the Commonwealth of Dominica, is an island country in the Caribbean. The capital, Roseau, is located on the western side of the island. It is geographically ...

, at ''

Climate

The climate of these islands is tropical, tempered by trade winds with moderate-high humidity. Despite its location between Guadeloupe and Dominica, the climate of ''les Saintes'' is different, and is more dry than its neighbours. It tends to get closer to the climate of St. Barts and most little islands of the Lesser Antilles. The archipelago covers an area of . Terre-de-Bas, the western isle, is wetter than Terre-de-Haut, the eastern. Though having 330 days of sunshine, the rainfall could reach but varies very widely. Summer is from May to November which is also the rainy season. Winter, from December to April, is the dry season. Sunshine is very prominent almost throughout the year and even during the rainy season. Humidity, however, is not very high because of the winds. It has an average temperature of with day temperatures rising to . The average temperature in January is while in July it is . The lowest night temperature could be . The Caribbean sea waters in the vicinity generally maintain a temperature of about . The archipelago faces frequent catastrophic threats of cyclonic storms.Environment

''Les Saintes'' extend only over but are characterised by a long coast, enriched by those of four small uninhabited islands. The coast of these islands does not have real cliffs, but their rocky shores are covered with corals. The sandy shores are more-or-less colonised by marinespermatophyte

A spermatophyte (; ), also known as phanerogam (taxon Phanerogamae) or phaenogam (taxon Phaenogamae), is any plant that produces seeds, hence the alternative name seed plant. Spermatophytes are a subset of the embryophytes or land plants. They inc ...

plants. In 2008, the inventory of the natural zones of ecological interest, fauna and flora (ZNIEFF) listed zones covering 381 hectares.

Fauna

Land

There are numerous ground iguanas, including the green iguana which is the heraldic symbol of Terre-de-Haut, and the ''Iguana delicatissima

The Lesser Antillean iguana (''Iguana delicatissima'') is a large arboreal lizard endemic to the Lesser Antilles. It is one of three species of lizard of the genus ''Iguana'' and is in severe decline due to habitat destruction, introduced feral p ...

'', which is threatened by the appearance of a hybrid stemming from the reproduction between the two species. Other reptiles include the Terre-de-Haut racer, Terre-de-Bas racer, the endemic Les Saintes anole, and a lot of species of anole

Dactyloidae are a family of lizards commonly known as anoles () and native to warmer parts of the Americas, ranging from southeastern United States to Paraguay. Instead of treating it as a family, some authorities prefer to treat it as a subfami ...

s.

There are also agoutis, goats, and stick insects

The Phasmatodea (also known as Phasmida, Phasmatoptera or Spectra) are an order of insects whose members are variously known as stick insects, stick-bugs, walking sticks, stick animals, or bug sticks. They are also occasionally referred to as ...

.

Birds include the bananaquit

The bananaquit (''Coereba flaveola'') is a species of passerine bird in the tanager family Thraupidae. Before the development of molecular genetics in the 21st century, its relationship to other species was uncertain and it was either placed with ...

, yellow-headed blackbird, dickcissel, blue-headed hummingbird

The blue-headed hummingbird (''Riccordia bicolor'') is a species of hummingbird in the "emeralds", tribe Trochilini of subfamily Trochilinae. It is found only on the islands of Dominica and Martinique in the Lesser Antilles.Clements, J. F., T. ...

, green-throated carib; purple-throated carib, and blue-tailed emerald

The blue-tailed emerald (''Chlorostilbon mellisugus'') is a hummingbird in the "emeralds", tribe Trochilini of subfamily Trochilinae. It is found in tropical and subtropical South America east of the Andes from Colombia east to the Guianas and ...

.

Ardeidaes rest in salty ponds (snowy egret

The snowy egret (''Egretta thula'') is a small white heron. The genus name comes from Provençal French for the little egret, , which is a diminutive of , 'heron'. The species name ''thula'' is the Araucano term for the black-necked swan, app ...

, green heron

The green heron (''Butorides virescens'') is a small heron of North and Central America. ''Butorides'' is from Middle English ''butor'' "bittern" and Ancient Greek ''-oides'', "resembling", and ''virescens'' is Latin for "greenish".

It was long c ...

, western cattle egret

The western cattle egret (''Bubulcus ibis'') is a species of heron (family Ardeidae) found in the tropics, subtropics and warm temperate zones. Most taxonomic authorities lump this species and the eastern cattle egret together (called the catt ...

, yellow-crowned night heron

The yellow-crowned night heron (''Nyctanassa violacea''), is one of two species of night herons found in the Americas, the other one being the black-crowned night heron. It is known as the ''bihoreau violacé'' in French and the ''pedrete corona ...

, tricolored heron, etc.) and living with the aquatic turtles, the common moorhen, the blue land crab, the blackback land crab, the sand fiddler crab and other species of crabs. The common kestrel is visible and audible during rides into the dry forest, like the zenaida dove, an endemic species of West Indies protected inside the archipelago.

Frogs include the Eleutherodactylus pinchoni

''Eleutherodactylus pinchoni'' is a species of frog in the family Eleutherodactylidae. It is endemic to Guadeloupe and known from the Basse-Terre. Common name Grand Cafe robber frog has been coined for it ( type locality is near "Grand Café").

...

, among others.

Tree bats feed on papayas and other fruits and berries.

Marine

The archipelago shelters a variety of: * Coral fishes (parrotfish

Parrotfishes are a group of about 90 fish species regarded as a Family (biology), family (Scaridae), or a subfamily (Scarinae) of the wrasses. With about 95 species, this group's largest species richness is in the Indo-Pacific. They are found ...

, ''Cephalopholis

''Cephalopholis'' is a genus of marine ray-finned fish, groupers from the subfamily Epinephelinae in the family Serranidae, which also includes the anthias and sea basses. Many of the species have the word "hind" as part of their common name in E ...

'', trumpetfish, mero, ''Epinephelus adscensionis'', cardinalfish, damselfish

Damselfish are those within the subfamilies Abudefdufinae, Chrominae, Lepidozyginae, Pomacentrinae, and Stegastenae within the family Pomacentridae. Most species within this group are relatively small, with the largest species being about 30 ...

, sergeant major fish, queen triggerfish

''Balistes vetula'', the queen triggerfish or old wife, is a reef dwelling triggerfish found in the Atlantic Ocean. It is occasionally caught as a gamefish, and sometimes kept in very large marine aquaria.

Etymology

This fish is called ''coc ...

, sunfish, scrawled cowfish

The scrawled cowfish (''Acanthostracion quadricornis'') is a species of boxfish native to the western tropical and equatorial Atlantic, as well as the Gulf of Mexico. They range in size from , with a maximum length of , and can be found at depths ...

, schoolmaster snapper

The schoolmaster snapper (''Lutjanus apodus''), also known as the dogtooth snapper, is a species of marine ray-finned fish, a snapper belonging to the family Lutjanidae. It is found in the western Atlantic Ocean. Like other snapper species, it i ...

, groupers, moray eels

Moray eels, or Muraenidae (), are a family of eels whose members are found worldwide. There are approximately 200 species in 15 genera which are almost exclusively marine, but several species are regularly seen in brackish water, and a few are fo ...

, conger

''Conger'' ( ) is a genus of marine congrid eels. It includes some of the largest types of eels, ranging up to 2 m (6 ft) or more in length, in the case of the European conger. Large congers have often been observed by divers during t ...

, green moray

The green moray (''Gymnothorax funebris'') is a moray eel of the family Muraenidae, found in the western Atlantic Ocean from New Jersey, Bermuda, and the northern Gulf of Mexico to Brazil, at depths down to . Its length is up to .

The common name ...

, black scorpionfish

The black scorpionfish (''Scorpaena porcus''), also known as the European scorpionfish or small-scaled scorpionfish, is a venomous scorpionfish, common in marine subtropical waters. It is widespread in the Eastern Atlantic Ocean from the British ...

(venomous), red snapper, balloonfishes, Atlantic blue tang surgeonfish

''Acanthurus coeruleus'' is a surgeonfish found commonly in the Atlantic Ocean. It can grow up to long.Figueiredo, J.L. and N.A. Menezes, (2000). ''Manual de peixes marinhos do sudeste do Brasil. VI. Teleostei (5)''. Museu de Zoologia, Universid ...

, etc.);

* Pelagic fishes

* Royal spiny lobsters ('' Panulirus argus'') and Brazilian lobsters (''Panulirus guttatus'')

* Crustaceans ( spiny spider crabs, edible crab, shrimp, slipper lobster, etc.)

* Molluscs (bobtail squid

Bobtail squid (order Sepiolida) are a group of cephalopods closely related to cuttlefish. Bobtail squid tend to have a rounder mantle than cuttlefish and have no cuttlebone. They have eight suckered arms and two tentacles and are generally qui ...

, squid

True squid are molluscs with an elongated soft body, large eyes, eight arms, and two tentacles in the superorder Decapodiformes, though many other molluscs within the broader Neocoleoidea are also called squid despite not strictly fitting t ...

, octopuses

An octopus ( : octopuses or octopodes, see below for variants) is a soft-bodied, eight- limbed mollusc of the order Octopoda (, ). The order consists of some 300 species and is grouped within the class Cephalopoda with squids, cuttlefish ...

)

* Shells ('' Strombus gigas'' renowned for their flesh, helmet shell, clam, whelks

Whelk (also known as scungilli) is a common name applied to various kinds of sea snail. Although a number of whelks are relatively large and are in the family Buccinidae (the true whelks), the word ''whelk'' is also applied to some other mari ...

, etc.)

*Sea anemone

Sea anemones are a group of predation, predatory marine invertebrates of the order (biology), order Actiniaria. Because of their colourful appearance, they are named after the ''Anemone'', a terrestrial flowering plant. Sea anemones are classifi ...

, seahorse

A seahorse (also written ''sea-horse'' and ''sea horse'') is any of 46 species of small marine fish in the genus ''Hippocampus''. "Hippocampus" comes from the Ancient Greek (), itself from () meaning "horse" and () meaning "sea monster" or " ...

, seaweeds, sea urchin

Sea urchins () are spiny, globular echinoderms in the class Echinoidea. About 950 species of sea urchin live on the seabed of every ocean and inhabit every depth zone from the intertidal seashore down to . The spherical, hard shells (tests) of ...

white and black, polyps and other species of cnidarian

Cnidaria () is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic animals found both in freshwater and marine environments, predominantly the latter.

Their distinguishing feature is cnidocytes, specialized cells that th ...

s (jellyfish

Jellyfish and sea jellies are the informal common names given to the medusa-phase of certain gelatinous members of the subphylum Medusozoa, a major part of the phylum Cnidaria. Jellyfish are mainly free-swimming marine animals with umbrella- ...

)

* Corals (diploria, fire corals, etc.) from Caribbean islands, which are prevalent during dives around the archipelago

* Sharks and rays

It is not rare to observe in Les Saintes Passage cetaceans: humpback whale

The humpback whale (''Megaptera novaeangliae'') is a species of baleen whale. It is a rorqual (a member of the family Balaenopteridae) and is the only species in the genus ''Megaptera''. Adults range in length from and weigh up to . The hump ...

s, sperm whale

The sperm whale or cachalot (''Physeter macrocephalus'') is the largest of the toothed whales and the largest toothed predator. It is the only living member of the genus ''Physeter'' and one of three extant species in the sperm whale famil ...

s, killer whales, and dolphin

A dolphin is an aquatic mammal within the infraorder Cetacea. Dolphin species belong to the families Delphinidae (the oceanic dolphins), Platanistidae (the Indian river dolphins), Iniidae (the New World river dolphins), Pontoporiidae (the ...

s, which during their migration reproduce in the warm seas of the Antilles.

Sea birds ( magnificent frigatebird, brown booby

The brown booby (''Sula leucogaster'') is a large seabird of the booby family Sulidae, of which it is perhaps the most common and widespread species. It has a pantropical range, which overlaps with that of other booby species. The gregarious brow ...

, masked booby

The masked booby (''Sula dactylatra''), also called the masked gannet or the blue-faced booby, is a large seabird of the booby and gannet family, Sulidae. First described by the French naturalist René-PrimevÚre Lesson in 1831, the masked bo ...

, terns, double-crested cormorant

The double-crested cormorant (''Nannopterum auritum'') is a member of the cormorant family of water birds. It is found near rivers and lakes, and in coastal areas, and is widely distributed across North America, from the Aleutian Islands in Alas ...

(''Phalacrocorax auritus''), pelican

Pelicans (genus ''Pelecanus'') are a genus of large water birds that make up the family Pelecanidae. They are characterized by a long beak and a large throat pouch used for catching prey and draining water from the scooped-up contents before s ...

, petrels) nest on the cliffs and uninhabited islands. In particular, on Grand-Ălet, a natural reserve of the archipelago which houses species of booby

A booby is a seabird in the genus ''Sula'', part of the family Sulidae. Boobies are closely related to the gannets (''Morus''), which were formerly included in ''Sula''.

Systematics and evolution

The genus ''Sula'' was introduced by the Frenc ...

found nowhere else on ''les Saintes'': red-footed booby

The red-footed booby (''Sula sula'') is a large seabird of the booby family, Sulidae. Adults always have red feet, but the colour of the plumage varies. They are powerful and agile fliers, but they are clumsy in takeoffs and landings. They are f ...

(''Sula sula'') and blue-footed booby

The blue-footed booby (''Sula nebouxii'') is a marine bird native to subtropical and tropical regions of the eastern Pacific Ocean. It is one of six species of the genus '' Sula'' â known as boobies. It is easily recognizable by its distinct ...