Émile Dorand on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Jean-Baptiste Émile Dorand (; 14 May 1866 – 1 July 1922), was a French military engineer and aircraft designer.

On 28 February 1916 the by now Lieutenant-Colonel Dorand was appointed as the first director of the

On 28 February 1916 the by now Lieutenant-Colonel Dorand was appointed as the first director of the

* Dorand 1911 biplane

* Dorand DO.1 (1913)

* Dorand Armoured Interceptor (1913)

* Dorand-Bugatti BU (1915) negative stagger

* Dorand 1911 biplane

* Dorand DO.1 (1913)

* Dorand Armoured Interceptor (1913)

* Dorand-Bugatti BU (1915) negative stagger

Early career

Émile Dorand was born inSemur-en-Auxois

Semur-en-Auxois () is a Communes of France, commune of the Côte-d'Or Departments of France, department in eastern France. The politician François Patriat, the engineers Edmé Régnier L'Aîné (1751–1825) and Émile Dorand (1866-1922), and th ...

in eastern France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

. He attended the École Polytechnique

(, ; also known as Polytechnique or l'X ) is a ''grande Ă©cole'' located in Palaiseau, France. It specializes in science and engineering and is a founding member of the Polytechnic Institute of Paris.

The school was founded in 1794 by mat ...

from 1886 to 1888 in the Latin Quarter

The Latin Quarter of Paris (, ) is an urban university campus in the 5th and the 6th arrondissements of Paris. It is situated on the left bank of the Seine, around the Sorbonne.

Known for its student life, lively atmosphere, and bistros, t ...

of Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

. He then went to the Fontainebleau

Fontainebleau ( , , ) is a Communes of France, commune in the Functional area (France), metropolitan area of Paris, France. It is located south-southeast of the Kilometre zero#France, centre of Paris. Fontainebleau is a Subprefectures in Franc ...

Application School, a military college, which he left after two years as a Lieutenant in the French Army

The French Army, officially known as the Land Army (, , ), is the principal Army, land warfare force of France, and the largest component of the French Armed Forces; it is responsible to the Government of France, alongside the French Navy, Fren ...

. In an engineering regiment, he met the airship

An airship, dirigible balloon or dirigible is a type of aerostat (lighter-than-air) aircraft that can navigate through the air flying powered aircraft, under its own power. Aerostats use buoyancy from a lifting gas that is less dense than the ...

pioneer Charles Renard

Charles Renard (1847–1905) born in Damblain, Vosges, was a French military engineer.

Airships

After the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871 he started work on the design of airships at the French army aeronautical department. Together with A ...

, and was soon authorised to direct free balloon

A balloon is a flexible membrane bag that can be inflated with a gas, such as helium, hydrogen, nitrous oxide, oxygen, or air. For special purposes, balloons can be filled with smoke, liquid water, granular media (e.g. sand, flour or rice), ...

flights. He studied aeronautics and the problems of flight including working to improve kite

A kite is a tethered heavier than air flight, heavier-than-air craft with wing surfaces that react against the air to create Lift (force), lift and Drag (physics), drag forces. A kite consists of wings, tethers and anchors. Kites often have ...

s, long range photography, and flight test methodology.

From 1895 to 1896, he was assigned to the Expeditionary Engineer Corps with whom he managed hydrogen balloons and bridging equipment in Madagascar

Madagascar, officially the Republic of Madagascar, is an island country that includes the island of Madagascar and numerous smaller peripheral islands. Lying off the southeastern coast of Africa, it is the world's List of islands by area, f ...

. He returned to France as a Captain, and was posted to Avignon

Avignon (, , ; or , ; ) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-CĂ´te d'Azur region of southeastern France. Located on the left bank of the river RhĂ´ne, the Communes of France, commune had a ...

, Dijon

Dijon (, ; ; in Burgundian language (Oïl), Burgundian: ''Digion'') is a city in and the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Côte-d'Or Departments of France, department and of the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté Regions of France, region in eas ...

and Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; ) is a former royal residence commissioned by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, Yvelines, Versailles, about west of Paris, in the Yvelines, Yvelines Department of ĂŽle-de-France, ĂŽle-de-France region in Franc ...

.

Aircraft development and design

In 1907 he moved to the Research Laboratory for Military Ballooning which became the Laboratory for Military Aeronautics, where he chaired the Engineering Study Commission in 1908. In that year he patented the design of an undercarriageshock absorber

A shock absorber or damper is a mechanical or hydraulics, hydraulic device designed to absorb and Damping ratio, damp shock (mechanics), shock impulses. It does this by converting the kinetic energy of the shock into another form of energy (typic ...

, which appears to be present on his powered kite or Dirigible Biplane

A biplane is a fixed-wing aircraft with two main wings stacked one above the other. The first powered, controlled aeroplane to fly, the Wright Flyer, used a biplane wing arrangement, as did many aircraft in the early years of aviation. While ...

, possibly named the Laboratoire, of 1909. which completely failed to fly. In 1910 he patented a link between an aircraft and its nacelle

A nacelle ( ) is a streamlined container for aircraft parts such as Aircraft engine, engines, fuel or equipment. When attached entirely outside the airframe, it is sometimes called a pod, in which case it is attached with a Hardpoint#Pylon, pylo ...

(in this context, fuselage

The fuselage (; from the French language, French ''fuselé'' "spindle-shaped") is an aircraft's main body section. It holds Aircrew, crew, passengers, or cargo. In single-engine aircraft, it will usually contain an Aircraft engine, engine as wel ...

). Both of these ideas were probably incorporated into his powered kite projects, where a steerable tractor engine and propeller were attached to a fuselage (nacelle) suspended from a large biplane or triplane kite. Dorand developed these in the period from 1908-1910.

In 1912 he became an engineering battalion commander and head of the Military Aeronautical Laboratory at Chalais-Meudon

Chalais-Meudon is an aeronautical research and development centre in Meudon, to the south-west of Paris. It was originally founded in 1793 in the nearby Château de Meudon and has played an important role in the development of French aviation. ...

. In 1914 he became its director, but it was closed in 1915 because of the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. In 1913 he developed the DO.1 two-seat armoured reconnaissance biplane, which was a successful design but severely underpowered.

On 28 February 1916 the by now Lieutenant-Colonel Dorand was appointed as the first director of the

On 28 February 1916 the by now Lieutenant-Colonel Dorand was appointed as the first director of the Service Technique de l'AĂ©ronautique

The (STAĂ©) was a French state body responsible for coordinating technical aspects of aviation in France. Formed in 1916 as the the STAĂ© continued until 1980 when its functions were distributed among other French governmental bodies, includin ...

(STAĂ©). One of his responsibilities was the drawing up of specifications of aircraft for the French military forces.

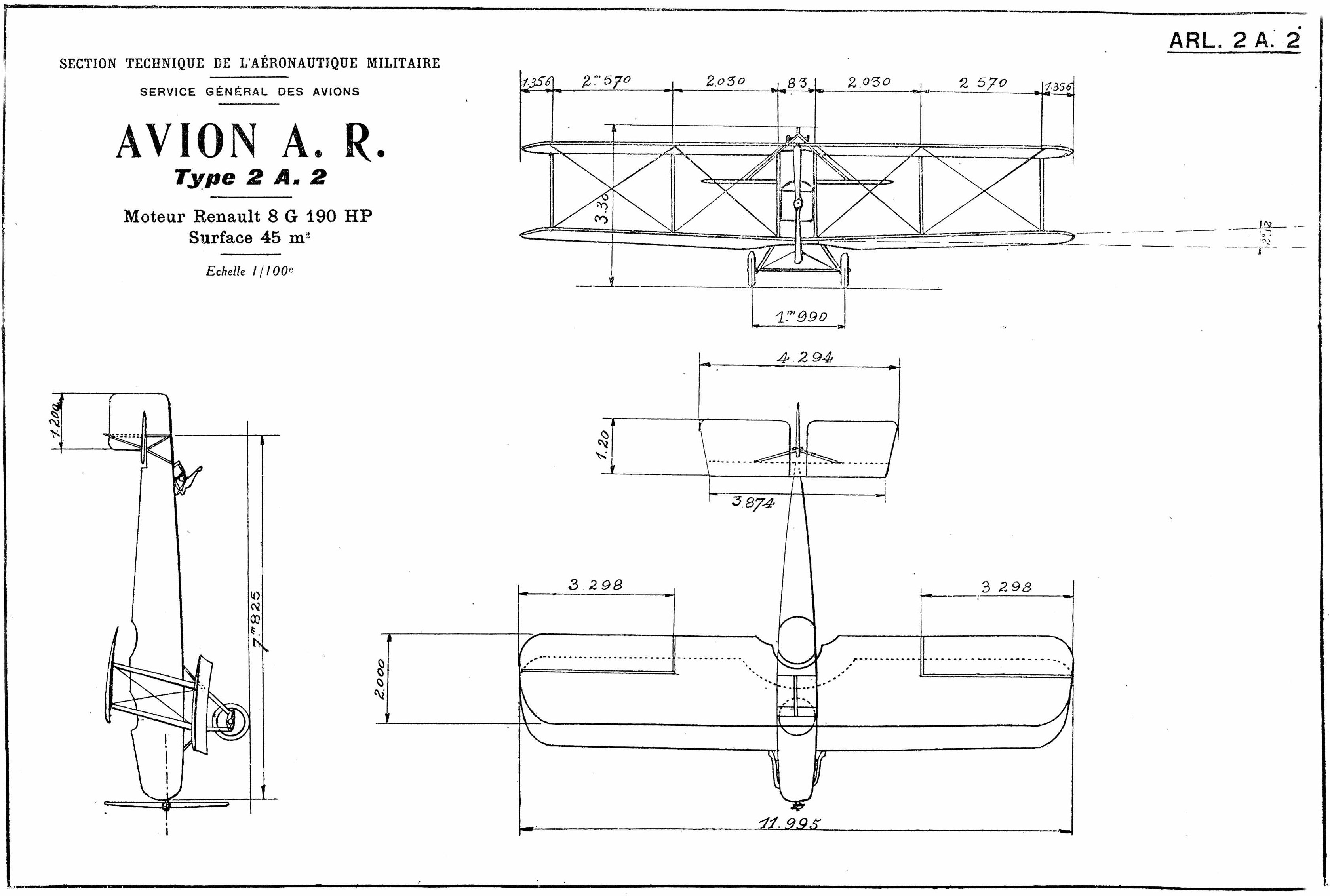

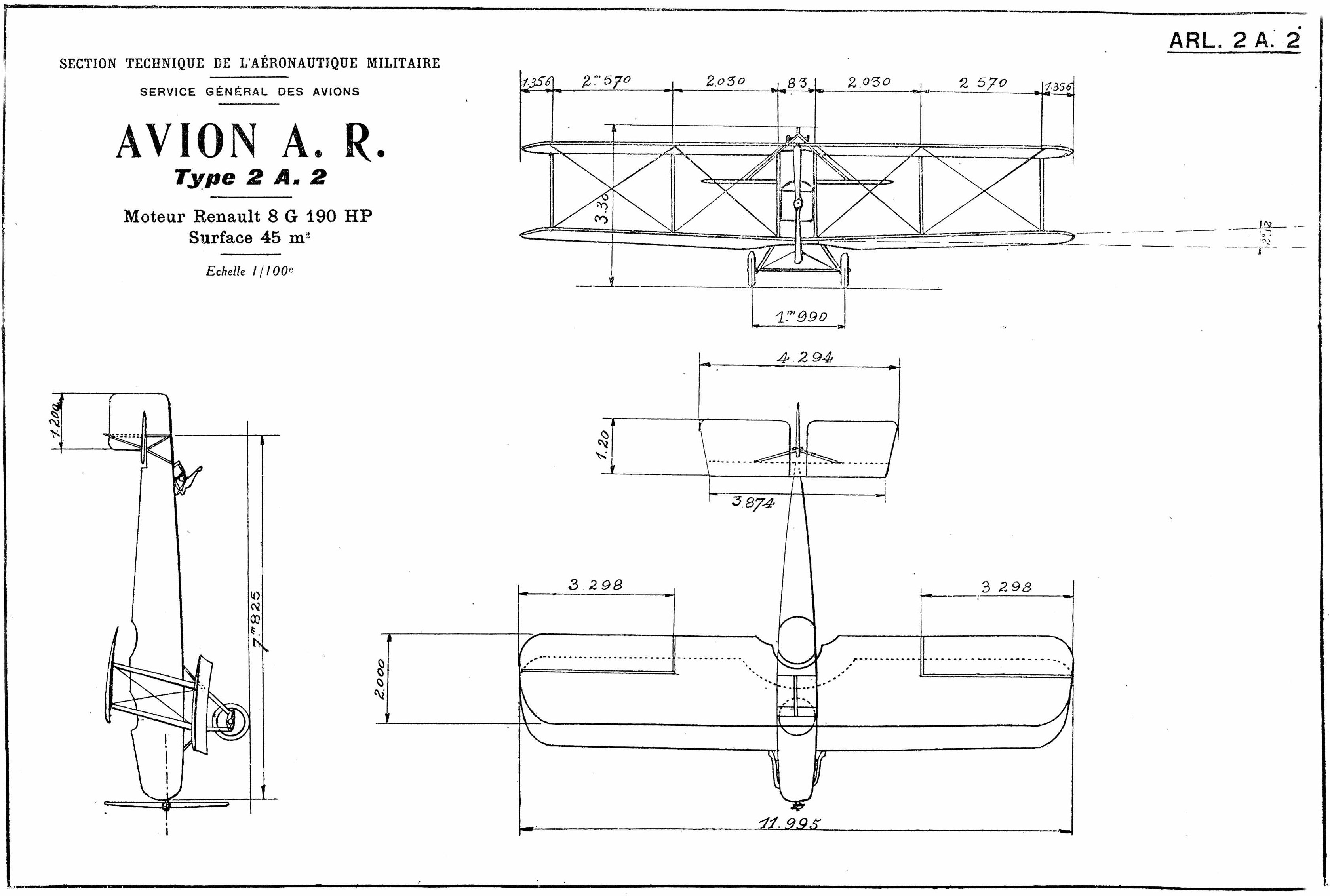

During 1916 he designed, in conjunction with Captain Georges Lepère, the AR.1 and subsequently the AR.2, which had reduced wing span and different engines. The ARs were much more successful than the DO.1, on which they were based. All these aircraft had distinctive negative stagger biplane wings, and the fuselage was mounted on struts between the wings.

In the same year Dorand collaborated with Émile Letord in the design of the Letord Let.1 three-seat twin-engined reconnaissance biplane, which featured Dorand’s negative stagger biplane wings. This led to a successful series of aircraft, built in the government factories at Chalais-Meudon and in the factories of Farman and Letord, ending with the Let.7. Over 250 examples were built by the end of the First World War, including 142 used as trainers by the American Expeditionary Force

The American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) was a formation of the United States Armed Forces on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front during World War I, composed mostly of units from the United States Army, U.S. Army. The AEF was establis ...

.

Postwar career

Dorand left the STAĂ© on 11 January 1918, and was appointed the Inspector General of Tests and Technical Studies at the French Ministry of War. Less than a year later he was promoted to Colonel and became the head of the French delegation of the Interallied Commission for Aeronautical Control inGermany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

. In this role he was responsible for searching the defeated country for anything of aeronautical interest that could be brought to France. He was also responsible for inspecting facilities to ensure that the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace ...

restrictions on German aeronautical activities were being observed.

During these activities he courted controversy by suggesting that Hugo Junkers

Hugo Junkers (3 February 1859 – 3 February 1935) was a German aircraft engineer and aircraft designer who pioneered the design of all-metal airplanes and flying wings. His company, Junkers Flugzeug- und Motorenwerke AG (Junkers Aircraft and ...

be brought to France to assist in the development of metal aircraft construction techniques. The press called into question Dorand's reputation, considering his plans a wasteful expansion of the air fleet for a country that now considered itself to be at peace.

Private life

He married Jeanne Marguerite Devanne in April 1897. They had one son, René Dorand, born in 1898, who from 1931 to 1938 worked withLouis Charles Breguet

Louis Charles Breguet (; 2 January 1880 in Paris – 4 May 1955 in Saint-Germain-en-Laye) was a French aircraft designer and builder, one of the early List of aviation pioneers, aviation pioneers.

Biography

Louis Charles Breguet was the g ...

on the development of helicopters, particularly the Bréguet-Dorand Gyroplane Laboratoire. He also wrote press articles attempting to restore the reputation of his father, recalling his important advances in French aeronautics. Émile died in Paris on 1 July 1922.

List of aircraft designs

*Powered kites series 1908-1911 possibly including the Dorand 1908 Avion Militaire * Dorand Laboratoire series from 1908 to 1912 * Dorand 1911 biplane

* Dorand DO.1 (1913)

* Dorand Armoured Interceptor (1913)

* Dorand-Bugatti BU (1915) negative stagger

* Dorand 1911 biplane

* Dorand DO.1 (1913)

* Dorand Armoured Interceptor (1913)

* Dorand-Bugatti BU (1915) negative stagger triplane

A triplane is a fixed-wing aircraft equipped with three vertically stacked wing planes. Tailplanes and canard (aeronautics), canard foreplanes are not normally included in this count, although they occasionally are.

Design principles

The trip ...

bomber project with two Bugatti

Automobiles Ettore Bugatti was a German then French automotive industry, manufacturer of high performance vehicle, high-performance automobiles. The company was founded in 1909 in the then-German Empire, German city of Molsheim, Alsace, by the ...

engines. The engines were a failure and the project was abandoned.

* Letord Let.1 to Let.7 series (1916)

* Dorand AR series (1916)

* Dorand flying boat (date unknown) A negative stagger biplane project with the engine buried in the streamlined fuselage, driving twin pusher propellers, Probably not built.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Dorand, Émile 1866 births 1922 deaths People from Semur-en-Auxois Aircraft designers French aerospace engineers 20th-century French inventors École Polytechnique alumni