|

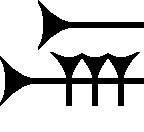

Bat (cuneiform)

The cuneiform bad, bat, be, etc. sign is a common multi-use sign in the mid 14th-century BC Amarna letters, and the ''Epic of Gilgamesh''. In the Epic it also has 5 sumerogram uses (capital letter (majuscule)). From Giorgio Buccellati (Buccellati 1979) 'comparative graphemic analysis' (about 360 cuneiform signs, nos. 1 through no. 598E), of 5 categories of letters, the usage numbers of the ''bad'' sign are as follows: Old Babylonian Royal letters (71), OB non-Royal letters (392), Mari letters (2108), Amarna letters (334), Ugarit letters (39). The following linguistic elements are used for the ''bad'' sign in the 12 chapter (Tablets I-Tablet XII) ''Epic of Gilgamesh'': :bad (not in Epic) :bat :be :mid :mit :sun :til :ziz sumerograms: :BE :IDIM :TIL :ÚŠ :ZIZ The following usage numbers for the linguistic elements of sign ''bad'' in the Epic are as follows: ''bad'', (0 times), ''bat'', (61), ''be'', (16), ''mid'', (7), ''mit'', (8), ''sun'', (1), ''til'', (11), ''ziz'', (8), '' ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Vassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerain. While the rights and obligations of a vassal are called vassalage, and the rights and obligations of a suzerain are called suzerainty. The obligations of a vassal often included military support by knights in exchange for certain privileges, usually including land held as a tenant or fief. The term is also applied to similar arrangements in other feudal societies. In contrast, fealty (''fidelitas'') was sworn, unconditional loyalty to a monarch. European vassalage In fully developed vassalage, the lord and the vassal would take part in a commendation ceremony composed of two parts, the homage and the fealty, including the use of Christian sacraments to show its sacred importance. According to Eginhard's brief description, the ''commenda ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Simo Parpola

Simo Kaarlo Antero Parpola (born 4 July 1943) is a Finnish Assyriologist specializing in the Neo-Assyrian Empire and Professor emeritus of Assyriology at the University of Helsinki (retired fall 2009). Career Simo Parpola studied Assyriology, Classics and Semitic Philology at the University of Helsinki, the Pontifical Biblical Institute and the British Museum in 1961–1968. He completed his PhD in Helsinki and began his academic career as wissenschaftlicher Assistant of Karlheinz Deller at the Seminar für Sprachen und Kulturen des Vorderen Orients of the University of Heidelberg in 1969. Between 1973 and 1976 he was Docent of Assyriology and Research Fellow at the University of Helsinki, and from 1977 to 1979 Associate Professor of Assyriology with tenure at the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. He was appointed Extraordinary Professor of Assyriology at the University of Helsinki in 1978 and has directed the University's Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project since 19 ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

William L

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of England in 1066,All Things William"Meaning & Origin of the Name"/ref> and remained so throughout the Middle Ages and into the modern era. It is sometimes abbreviated "Wm." Shortened familiar versions in English include Will, Wills, Willy, Willie, Bill, and Billy. A common Irish form is Liam. Scottish diminutives include Wull, Willie or Wullie (as in Oor Wullie or the play ''Douglas''). Female forms are Willa, Willemina, Wilma and Wilhelmina. Etymology William is related to the given name ''Wilhelm'' (cf. Proto-Germanic ᚹᛁᛚᛃᚨᚺᛖᛚᛗᚨᛉ, ''*Wiljahelmaz'' > German ''Wilhelm'' and Old Norse ᚢᛁᛚᛋᛅᚼᛅᛚᛘᛅᛋ, ''Vilhjálmr''). By regular sound changes, the native, inherited English form of the name shoul ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Segue

A segue (; ) is a smooth transition from one topic or section to the next. The term is derived from Italian ''segue'', which literally means "follows". In music In music, ''segue'' is a direction to the performer. It means ''continue (the next section) without a pause''. The term attacca is used synonymously. For written music, it implies a transition from one section to the next without any break. In improvisation, it is often used for transitions created as a part of the performance, leading from one section to another. In live performance, a segue can occur during a jam session, where the improvisation of the end of one song progresses into a new song. Segues can even occur between groups of musicians during live performance. For example, as one band finishes its set, members of the following act replace members of the first band one by one, until a complete band swap occurs. In recorded music, a segue is a seamless transition between one song and another. The effect is oft ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Ma (cuneiform)

The cuneiform ma sign, is found in both the 14th century BC Amarna letters and the ''Epic of Gilgamesh''. In the Epic it is also used as the Sumerogram MA, (for Akkadian language "mina", ''manû'', a weight measure, as MA.NA, or MA.NA.ÀM). The ''ma'' sign is often used at the end of words, besides its alphabetic usage inside words as syllabic ''ma'', elsewhere for ''m'', or ''a''. The usage of cuneiform ''ma'' in the ''Epic of Gilgamesh'', is only exceeded by the usage of a (cuneiform) (1369 times, and 58, A (Sumerogram), versus 1047 times for ''ma'', 6 for MA (Sumerogram)). The high usage for ''a'' is partially a result of the prepositional use for ''a-na''-(Akkadian "ana", ''to, for'', etc.); "''i''", also has an increased prepositional use of i (cuneiform), for Akkadian ''ina'', ( i- na), for ''in, into, etc.'' References * Moran, William L. 1987, 1992. ''The Amarna Letters.'' Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987, 1992. 393 pages.(softcover, ) * Parpola, 1971. ''Th ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Nu (cuneiform)

Cuneiform sign nu is a common use syllabic, or alphabetic (for ''n'' or ''u''). It is restricted to "nu", but in the ''Epic of Gilgamesh'', or elsewhere has a Sumerogram (capital letter, majuscule) use NU, and probably mostly for a component in personal names (PN), god's names, or specialized names for specific items that use Sumerograms. It is also a common use syllabic/alphabetic sign in the mid 14th-century BC Amarna letters. Since the letters often discuss 'present conditions' in regions, or in cities of the vassal Canaanite region, a segue adverb meaning ''"now"'', or ''now, at this time...,'' Akkadian language "enūma" is often used, and almost exclusively using ''nu''. The usage numbers for ''nu'' in the ''Epic of Gilgamesh'' are as follows: ''nu''-(317), ''NU''-(2). Two styles of "nu" sign Since the ''nu'' cuneiform sign is in a small category of "2-stroke" signs, it is interesting that there exist two simple varieties of the sign. After the first horizontal stroke ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Di (cuneiform)

The cuneiform di sign, also de, ṭe, ṭi, and sumerograms DI and SÁ is a common-use sign of the ''Epic of Gilgamesh'', the 1350 BC Amarna letters, and other cuneiform texts. In the Akkadian language for forming words, it can be used syllabically for: ''de, di, ṭe, and ṭi''; also alphabetically for letters ''d'', ''ṭ'', ''e'', or ''i''. (All the four vowels in Akkadian are interchangeable for forming words (''a, e, i, u''), thus the many choices of scribes is apparent for composing actual 'dictionary-entry' words.) Some consonant-pairs (d/t), are also interchangeable (for example the ''d'', ''t'', and ''ṭ''). ''Epic of Gilgamesh'' usage The usage numbers for ''di/de'' in the ''Epic of Gilgamesh'' are as follows: ''de''-(8) times, ''di''-(161), ''ṭe''-(7), ''ṭi''-(19), ''DI''-(1), ''SÁ''-(2) times. Besides ''ša'' usage in word components of verbs, nouns, etc., it has a major usage between words. In Akkadian, for English language ''"who"'', it is an interrogati ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

I (cuneiform)

The cuneiform i sign is a common use vowel sign. It can be found in many languages, examples being the Akkadian language of the ''Epic of Gilgamesh'' (hundreds of years, parts of millenniums) and the mid 14th-century BC Amarna letters; also the Hittite language-(see table of Hittite cuneiform signs below). In the ''Epic of Gilgamesh'' it also has a minor usage as a sumerogram, I. The usage numbers from the Epic are as follows: ''i''-(698), ''I''-(1). As ''i'' and one of the four vowels in Akkadian (there is no "o"), scribes can easily use one sign (a vowel, or a syllable with a vowel) to substitute one vowel for another. In the Amarna letters, the segue adverb ''"now"'', or "now, at this time", Akkadian language 'enūma', is seldom spelled with the 'e'; instead its spellings are typically: ''anūma'', ''inūma'', and sometimes ''enūma''. In both the Amarna letters and the ''Epic of Gilgamesh'' another common use of the "i" sign is for the preposition, Akkadian language ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

ù (cuneiform)

The cuneiform ù sign ('u, no. 3'), is found in both the 14th century BC Amarna letters and the ''Epic of Gilgamesh''. Its use is as a conjunction, (translated as for example: ''and, but, else, until,'' etc.), but rarely it is substituted for ''alphabetic u'', but that vowel ''u'' is typically represented by 'u, no. 2', (u prime), ú; occasionally 'u, no. 1', ( u (cuneiform)), , (mostly used for a conjunction, and ''numeral 10''), is also substituted for the "alphabetic u". The use of ''ù'' is often as a "stand-alone" conjunction, for example between two listed items, but it is used especially as a segue in text, (example Amarna letters), when changing topics, or when inserting segue-pausing positions. In the Amarna letters, it is also commonly immediately followed by a preposition: '' a- na'', or '' i- na'', used as ''"...And, to...."'', or ''"...And, in...."''; also ''"...But, for...."'', etc. This usage with a preposition is also a better example of the segue usage. Of ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Anson Rainey

Anson Frank Rainey (January 11, 1930 – February 19, 2011) was professor emeritus of ancient Near Eastern cultures and Semitic linguistics at Tel Aviv University. He is known in particular for contributions to the study of the Amarna tablets, the noted administrative letters from the period of Pharaoh Akhenaten's rule during the 18th Dynasty of Egypt.Rollston, C. (2011)Among the last of the titans: Aspects of Professor Anson Rainey's life and legacy (1930–2011)(February 20, 2011); retrieved May 22, 2017 He authored and edited books and articles on the cultures, languages and geography of the Biblical lands. Early life Anson Rainey was born in Dallas, Texas, in 1930. Upon the death of his father that same year, he was left with his maternal grandparents. He attended Brown Military Academy in San Diego, California, from 1943 to 1946. After one semester of study there – as a cadet battalion commander – he served as assistant commandant at Southern California Mi ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

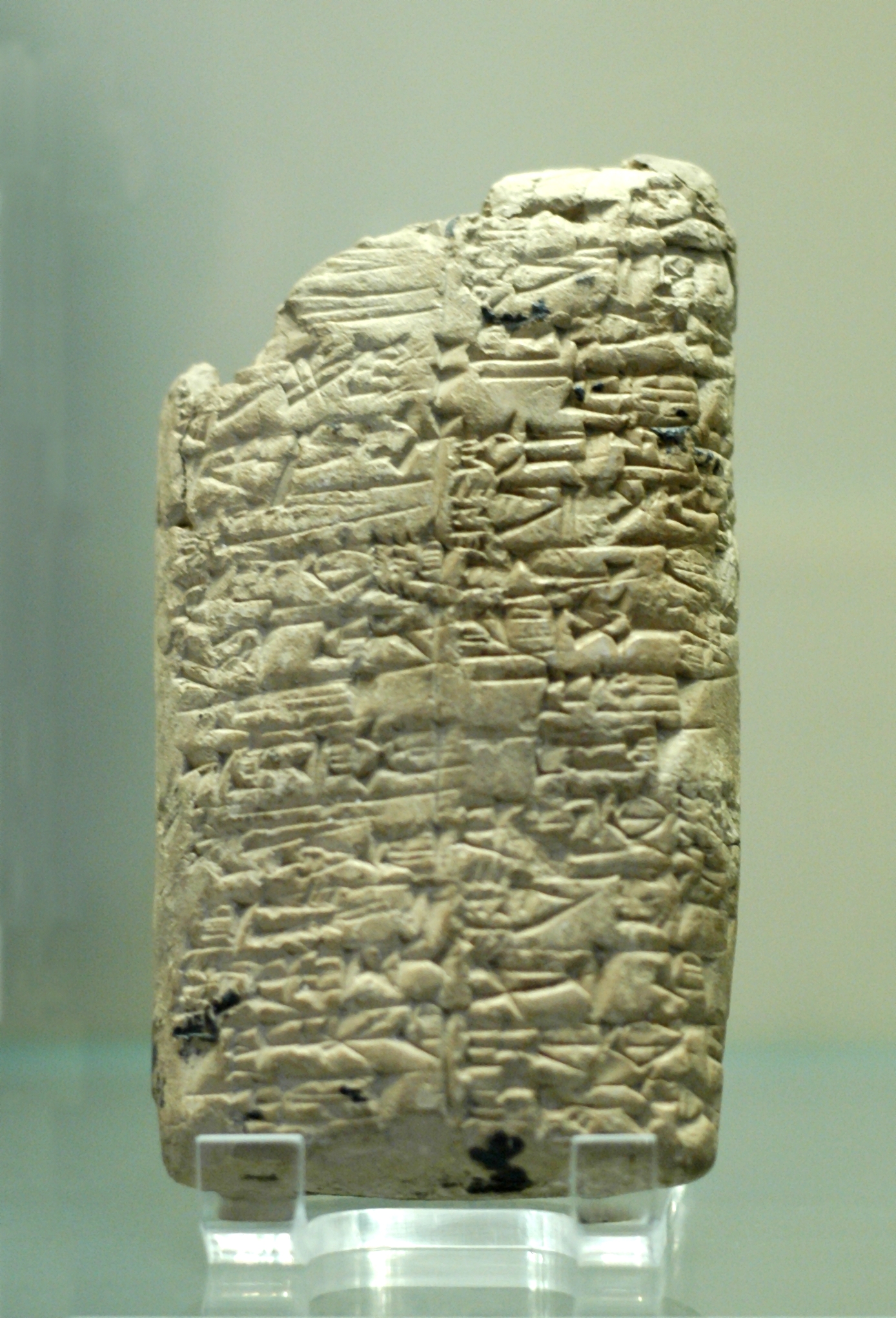

Clay Tablet

In the Ancient Near East, clay tablets (Akkadian ) were used as a writing medium, especially for writing in cuneiform, throughout the Bronze Age and well into the Iron Age. Cuneiform characters were imprinted on a wet clay tablet with a stylus often made of reed (reed pen). Once written upon, many tablets were dried in the sun or air, remaining fragile. Later, these unfired clay tablets could be soaked in water and recycled into new clean tablets. Other tablets, once written, were either deliberately fired in hot kilns, or inadvertently fired when buildings were burnt down by accident or during conflict, making them hard and durable. Collections of these clay documents made up the first archives. They were at the root of the first libraries. Tens of thousands of written tablets, including many fragments, have been found in the Middle East. Surviving tablet-based documents from the Minoan/ Mycenaean civilizations, are mainly those which were used for accounting. Tablets servin ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |