|

Anaerobiosis

An anaerobic organism or anaerobe is any organism that does not require molecular oxygen for growth. It may react negatively or even die if free oxygen is present. In contrast, an aerobic organism (aerobe) is an organism that requires an oxygenated environment. Anaerobes may be unicellular (e.g. protozoans, bacteria) or multicellular. Most fungi are obligate aerobes, requiring oxygen to survive. However, some species, such as the Chytridiomycota that reside in the rumen of cattle, are obligate anaerobes; for these species, anaerobic respiration is used because oxygen will disrupt their metabolism or kill them. Deep waters of the ocean are a common anoxic environment. First observation In his letter of 14 June 1680 to The Royal Society, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek described an experiment he carried out by filling two identical glass tubes about halfway with crushed pepper powder, to which some clean rain water was added. Van Leeuwenhoek sealed one of the glass tubes using a flame and ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

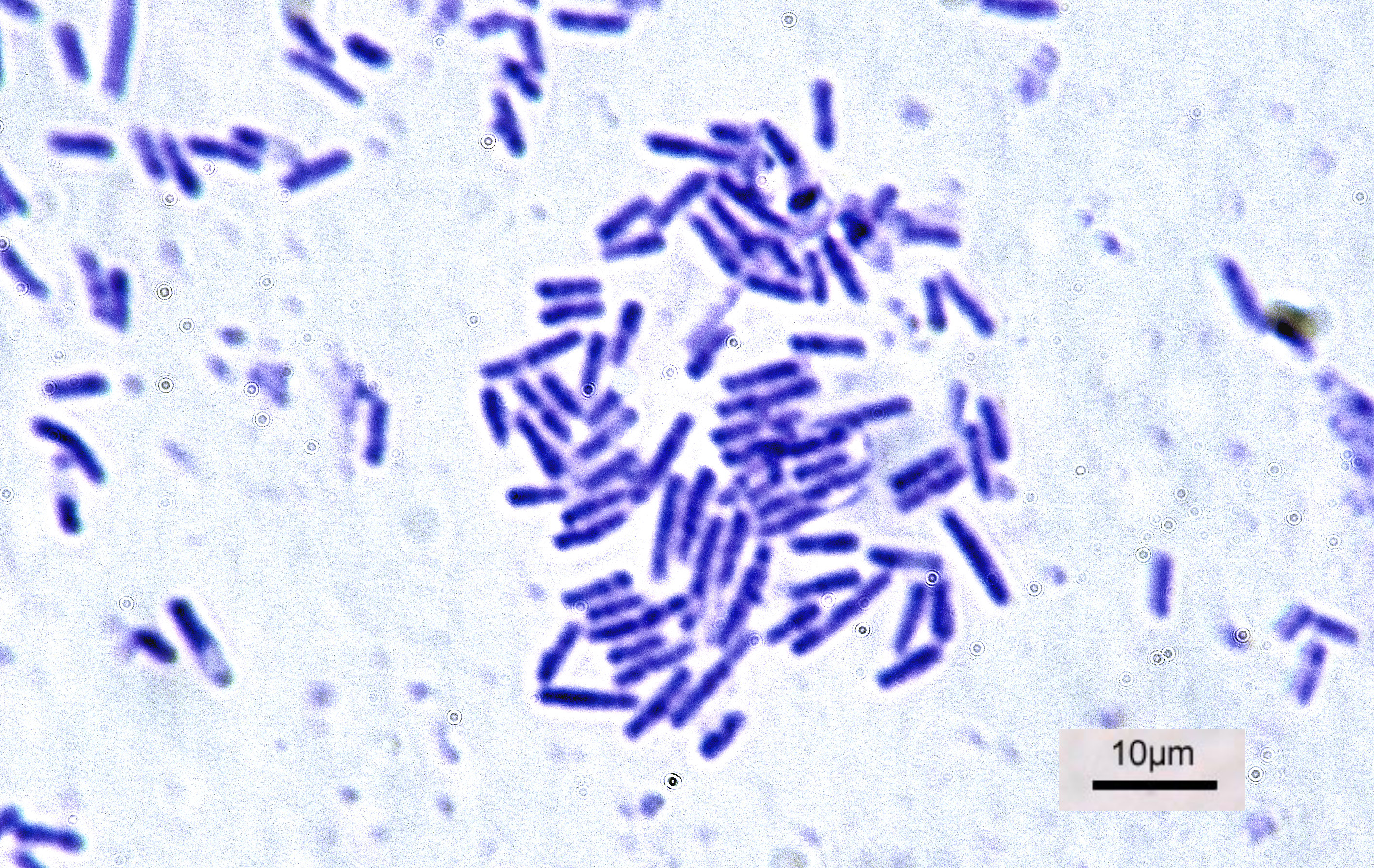

Bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among the first life forms to appear on Earth, and are present in most of its habitats. Bacteria inhabit soil, water, acidic hot springs, radioactive waste, and the deep biosphere of Earth's crust. Bacteria are vital in many stages of the nutrient cycle by recycling nutrients such as the fixation of nitrogen from the atmosphere. The nutrient cycle includes the decomposition of dead bodies; bacteria are responsible for the putrefaction stage in this process. In the biological communities surrounding hydrothermal vents and cold seeps, extremophile bacteria provide the nutrients needed to sustain life by converting dissolved compounds, such as hydrogen sulphide and methane, to energy. Bacteria also live in symbiotic and parasitic re ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Spinoloricus

''Spinoloricus'' is a genus of nanaloricid loriciferans. Its type species is ''S. turbatio'', described in 2007, and another species, native to completely anoxic environment, '' Spinoloricus cinziae'', was described in 2014.Neves, Gambi, Danovaro & Kristensen (2014) ''Spinoloricus cinziae'' (Phylum Loricifera), a new species from a hypersaline anoxic deep basin in the Mediterranean Sea.'' Systematics and Biodiversity'', , 4, . References Loricifera Protostome genera {{Protostome-stub ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Aerobic Respiration

Cellular respiration is the process by which biological fuels are oxidised in the presence of an inorganic electron acceptor such as oxygen to produce large amounts of energy, to drive the bulk production of ATP. Cellular respiration may be described as a set of metabolic reactions and processes that take place in the cells of organisms to convert chemical energy from nutrients into adenosine triphosphate (ATP), and then release waste products. The reactions involved in respiration are catabolic reactions, which break large molecules into smaller ones, releasing energy. Respiration is one of the key ways a cell releases chemical energy to fuel cellular activity. The overall reaction occurs in a series of biochemical steps, some of which are redox reactions. Although cellular respiration is technically a combustion reaction, it is an unusual one because of the slow, controlled release of energy from the series of reactions. Nutrients that are commonly used by animal and pl ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Methanogenesis

Methanogenesis or biomethanation is the formation of methane coupled to energy conservation by microbes known as methanogens. Organisms capable of producing methane for energy conservation have been identified only from the domain Archaea, a group phylogenetically distinct from both eukaryotes and bacteria, although many live in close association with anaerobic bacteria. Other forms of methane production that are not coupled to ATP synthesis exist within all three domains of life. The production of methane is an important and widespread form of microbial metabolism. In anoxic environments, it is the final step in the decomposition of biomass. Methanogenesis is responsible for significant amounts of natural gas accumulations, the remainder being thermogenic. Biochemistry Methanogenesis in microbes is a form of anaerobic respiration. Methanogens do not use oxygen to respire; in fact, oxygen inhibits the growth of methanogens. The terminal electron acceptor in methanogenesis i ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Acetogenesis

Acetogenesis is a process through which acetate is produced either by the reduction of CO2 or by the reduction of organic acids, rather than by the oxidative breakdown of carbohydrates or ethanol, as with acetic acid bacteria. The different bacterial species that are capable of acetogenesis are collectively termed acetogens. Reduction of CO2 to acetate by anaerobic bacteria occurs via the Wood–Ljungdahl pathway and requires an electron source (e.g., H2, CO, formate, etc.). Some acetogens can synthesize acetate autotrophically from carbon dioxide and hydrogen gas. Reduction of organic acids to acetate by anaerobic bacteria occurs via fermentation. Discovery In 1932, organisms were discovered that could convert hydrogen gas and carbon dioxide into acetic acid. The first acetogenic bacterium species, '' Clostridium aceticum'', was discovered in 1936 by Klaas Tammo Wieringa. A second species, ''Moorella thermoacetica'', attracted wide interest because of its ability, rep ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Stickland Fermentation

Stickland fermentation or The Stickland Reaction is the name for a chemical reaction that involves the coupled oxidation and reduction of amino acids to organic acids. The electron donor amino acid is oxidised to a volatile carboxylic acid one carbon atom shorter than the original amino acid. For example, alanine with a three carbon chain is converted to acetate with two carbons. The electron acceptor amino acid is reduced to a volatile carboxylic acid the same length as the original amino acid. For example, glycine with two carbons is converted to acetate. In this way, amino acid fermenting microbes can avoid using hydrogen ions as electron acceptors to produce hydrogen gas. Amino acids can be Stickland acceptors, Stickland donors, or act as both donor and acceptor. Only histidine cannot be fermented by Stickland reactions, and is oxidised. With a typical amino acid mix, there is a 10% shortfall in Stickland acceptors, which results in hydrogen production. Under very l ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Butanediol Fermentation

2,3-Butanediol fermentation is anaerobic fermentation of glucose with 2,3-butanediol as one of the end products. The overall stoichiometry of the reaction is :2 pyruvate + NADH --> 2 CO2 + 2,3-butanediol. Butanediol fermentation is typical for the facultative anaerobes ''Klebsiella'' and '' Enterobacter'' and is tested for using the Voges–Proskauer (VP) test. There are other alternative strains that can be used, talked about in details in the Alternative Bacteria Strains section below. The metabolic function of 2,3-butanediol is not known, although some have speculated that it was an evolutionary advantage for these microorganisms to produce a neutral product that's less inhibitory than other partial oxidation products and doesn't reduce the pH as much as mixed acids. There are many important industrial applications that butanediol can be used for, including antifreeze, food additives, antiseptic, and pharmaceuticals. It also is produced naturally in various places of the en ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Mixed Acid Fermentation

In biochemistry, mixed acid fermentation is the metabolic process by which a six-carbon sugar (e.g. glucose, ) is converted into a complex and variable mixture of acids. It is an anaerobic (non-oxygen-requiring) fermentation reaction that is common in bacteria. It is characteristic for members of the Enterobacteriaceae, a large family of Gram-negative bacteria that includes ''E. coli''. The mixture of end products produced by mixed acid fermentation includes lactate, acetate, succinate, formate, ethanol and the gases and . The formation of these end products depends on the presence of certain key enzymes in the bacterium. The proportion in which they are formed varies between different bacterial species. The mixed acid fermentation pathway differs from other fermentation pathways, which produce fewer end products in fixed amounts. The end products of mixed acid fermentation can have many useful applications in biotechnology and industry. For instance, ethanol is widely ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Butyric Acid

Butyric acid (; from grc, βούτῡρον, meaning "butter"), also known under the systematic name butanoic acid, is a straight-chain alkyl carboxylic acid with the chemical formula CH3CH2CH2CO2H. It is an oily, colorless liquid with an unpleasant odor. Isobutyric acid (2-methylpropanoic acid) is an isomer. Salts and esters of butyric acid are known as butyrates or butanoates. The acid does not occur widely in nature, but its esters are widespread. It is a common industrial chemical and an important component in the mammalian gut. History Butyric acid was first observed in impure form in 1814 by the French chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul. By 1818, he had purified it sufficiently to characterize it. However, Chevreul did not publish his early research on butyric acid; instead, he deposited his findings in manuscript form with the secretary of the Academy of Sciences in Paris, France. Henri Braconnot, a French chemist, was also researching the composition of butter and was pu ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

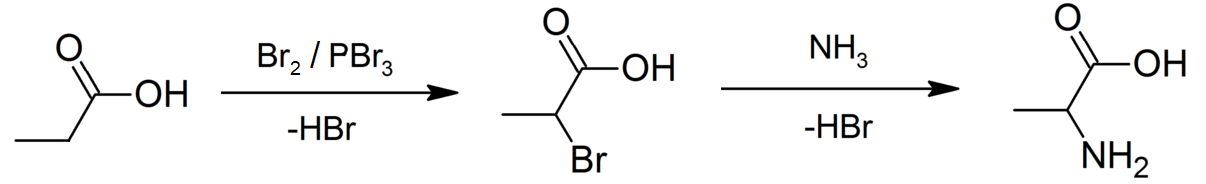

Propionic Acid

Propionic acid (, from the Greek words πρῶτος : ''prōtos'', meaning "first", and πίων : ''píōn'', meaning "fat"; also known as propanoic acid) is a naturally occurring carboxylic acid with chemical formula CH3CH2CO2H. It is a liquid with a pungent and unpleasant smell somewhat resembling body odor. The anion CH3CH2CO2− as well as the salts and esters of propionic acid are known as propionates or propanoates. History Propionic acid was first described in 1844 by Johann Gottlieb, who found it among the degradation products of sugar. Over the next few years, other chemists produced propionic acid by different means, none of them realizing they were producing the same substance. In 1847, French chemist Jean-Baptiste Dumas established all the acids to be the same compound, which he called propionic acid, from the Greek words πρῶτος (prōtos), meaning ''first'', and πίων (piōn), meaning ''fat'', because it is the smallest H(CH2)''n''COOH acid that e ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Archaea

Archaea ( ; singular archaeon ) is a domain of single-celled organisms. These microorganisms lack cell nuclei and are therefore prokaryotes. Archaea were initially classified as bacteria, receiving the name archaebacteria (in the Archaebacteria kingdom), but this term has fallen out of use. Archaeal cells have unique properties separating them from the other two domains, Bacteria and Eukaryota. Archaea are further divided into multiple recognized phyla. Classification is difficult because most have not been isolated in a laboratory and have been detected only by their gene sequences in environmental samples. Archaea and bacteria are generally similar in size and shape, although a few archaea have very different shapes, such as the flat, square cells of '' Haloquadratum walsbyi''. Despite this morphological similarity to bacteria, archaea possess genes and several metabolic pathways that are more closely related to those of eukaryotes, notably for the enzymes invo ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Kilojoule Per Mole

The joule per mole (symbol: J·mol−1 or J/mol) is the unit of energy per amount of substance in the International System of Units (SI), such that energy is measured in joules, and the amount of substance is measured in moles. It is also an SI derived unit of molar thermodynamic energy defined as the energy equal to one joule in one mole of substance. For example, the Gibbs free energy of a compound in the area of thermochemistry is often quantified in units of kilojoules per mole (symbol: kJ·mol−1 or kJ/mol), with 1 kilojoule = 1000 joules. Physical quantities measured in J·mol−1 usually describe quantities of energy transferred during phase transformations or chemical reactions. Division by the number of moles facilitates comparison between processes involving different quantities of material and between similar processes involving different types of materials. The precise meaning of such a quantity is dependent on the context (what substances are involved, circums ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

.jpg)