|

Tishpak

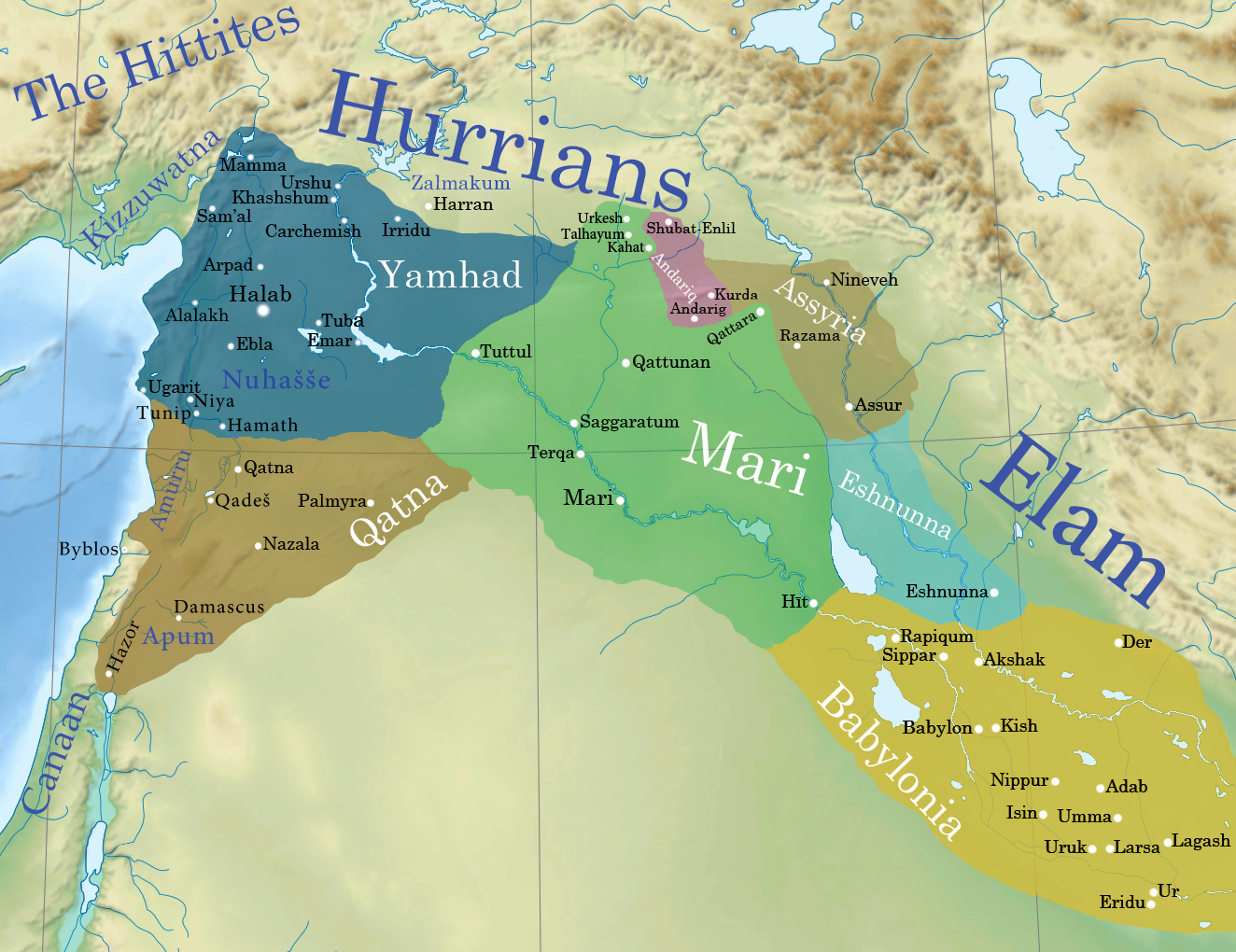

Tishpak (Tišpak) was a Mesopotamian god associated with the ancient city Eshnunna and its sphere of influence, located in the Diyala area of Iraq. He was primarily a war deity, but he was also associated with snakes, including the mythical mushussu and bashmu, and with kingship. Tishpak was of neither Sumerian nor Akkadian origin and displaced Eshnunna's original tutelary god, Ninazu. Their iconography and character were similar, though they were not formally regarded as identical in most Mesopotamian sources. Origin It is commonly assumed that initially the tutelary deity of Eshnunna was Ninazu, worshiped in the temple Esikil. From the Sargonic period onward, Tishpak competed with Ninazu in that location, and the latter finally ceased to be mentioned in documents from it after Hammurabi's conquest. While similar in character, Ninazu and Tishpak were not fully conflated, and unlike Inanna and Ishtar or Enki and Ea were kept apart in god lists. It is generally agreed by scho ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

List Of Mesopotamian Deities

Deities in ancient Mesopotamia were almost exclusively anthropomorphic. They were thought to possess extraordinary powers and were often envisioned as being of tremendous physical size. The deities typically wore ''melam'', an ambiguous substance which "covered them in terrifying splendor" and which could also be worn by heroes, kings, giants, and even demons. The effect that seeing a deity's ''melam'' has on a human is described as ''ni'', a word for the " physical creeping of the flesh". Both the Sumerian and Akkadian languages contain many words to express the sensation of ''ni'', including the word ''puluhtu'', meaning "fear". Deities were almost always depicted wearing horned caps, consisting of up to seven superimposed pairs of ox-horns. They were also sometimes depicted wearing clothes with elaborate decorative gold and silver ornaments sewn into them. The ancient Mesopotamians believed that their deities lived in Heaven, but that a god's statue was a physical embodime ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Kulla (goddess)

Ukulla, also called Ugulla, Kulla or Kullab, was a Mesopotamian goddess regarded as the wife of Tishpak. She was chiefly worshiped in Eshnunna. Based on the variable spelling of her name in cuneiform it has been suggested that much like her husband and their son Nanshak she had neither Sumerian nor Akkadian origin. Name and character The oldest attested form of the name is Ukulla, but multiple variants are attested and the orthography varies between sources. It seems both the ''u'' in the front and a ''b'' in the end were viewed as optional. Manfred Krebernik suggests that the alternate writings were the result of confusion with the brick god Kulla and with the toponym Kullaba. As of 2022 there is no single agreed upon spelling in secondary literature. This article employs the form Ukulla following the corresponding ''Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie'' entry. In early scholarship, attempts were made to connect the name with Sumerian ''u3-gul'' (' ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Ninazu

Ninazu ( sux, ) was a Mesopotamian god of the underworld of Sumerian origin. He was also associated with snakes and vegetation, and with time acquired the character of a warrior god. He was frequently associated with Ereshkigal, either as a son, husband, or simply as a deity belonging to the same category of underworld gods. His original cult centers were Enegi and Eshnunna, though in the later city he was gradually replaced by a similar god, Tishpak. His cult declined after the Old Babylonian period, though in the city of Ur, where it was introduced from Enegi, he retained a number of worshipers even after the fall of the last Mesopotamian empires. Character and iconography According to Julia M. Asher-Greve, Ninazu was initially considered a "high-ranking local god," similar in rank to Ningirsu. His name has Sumerian origin and can be translated as "lord healer," though he was rarely associated with medicine. It is nonetheless agreed that he could be considered a healing ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Ištaran

Ištaran (Ishtaran, sux, ) was a Mesopotamian god who was the tutelary deity of the city of Der, a Sumerian city state positioned east of the Tigris on the border between Sumer and Elam. It is known that he was a judge deity, and his position in the Mesopotamian pantheon was most likely high, but much about his character remains uncertain. He was associated with snakes, especially with the snake god Nirah, and it is possible that he could be depicted in a partially or fully serpentine form himself. Name The reading Ištaran has been established as correct by Wilfred G. Lambert in 1969. Other, now obsolete, proposals included Sataran, Satran, Gusilim, and Eatrana. Also attested are a variant form, Iltaran, and an Emesal one, Ezeran (or Ezzeran). It is commonly assumed that Ištaran's name originated in a Semitic language. It has been proposed that it was etymologically related to Ishtar. Christopher Woods suggests that the suffix ''-an'' should be understood as plural, and ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Eshnunna

Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar in Diyala Governorate, Iraq) was an ancient Sumerian (and later Akkadian) city and city-state in central Mesopotamia 12.6 miles northwest of Tell Agrab and 15 miles northwest of Tell Ishchali. Although situated in the Diyala Valley north-west of Sumer proper, the city nonetheless belonged securely within the Sumerian cultural milieu. It is sometimes, in archaeological papers, called Ashnunnak or Tuplias,. The tutelary deity of the city was Tishpak (Tišpak) (having replaced Ninazu) though other gods, including Sin, Adad, and Inanna of Kititum were also worshiped there. The personal goddess of the rulers were Belet-Šuḫnir and Belet-Terraban. History Early Bronze Inhabited since the Jemdet Nasr period, around 3000 BC, Eshnunna was a major city during the Early Dynastic period of Mesopotamia. It is known, from cuneiform records and excavations, that the city was occupied in the Akkadian period though its extent was noticeably less than it reache ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Milkunni

Milku was a god associated with the underworld who was worshiped in the kingdoms of Ugarit and Amurru in the late Bronze Age. It is possible that he originated further south, as Ugaritic texts indicate he was worshiped in cities located in the northern part of the Transjordan region. He was also incorporated into the Hurrian pantheon under the name Milkunni. There is also evidence that he was worshiped in Hittite religion. It is possible that a closely related deity is also known from Mesopotamia. In the alphabetic script used in Ugarit, which does not always preserve vowels, Milku's name was written the same as the word ''malku,'' "king." As a result it is sometimes difficult to tell which of these two cognate words is meant. However, it is agreed that they were vocalized differently. It has been proposed that one of Milku's epithets was a pun referencing this writing convention. Name and character The name of an underworld deity written as ''mlk'' in the Ugaritic alphabetic scr ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Ancient Mesopotamian Underworld

The ancient Mesopotamian underworld, most often known in Sumerian as Kur, Irkalla, Kukku, Arali, or Kigal and in Akkadian as Erṣetu, although it had many names in both languages, was a dark, dreary cavern located deep below the ground, where inhabitants were believed to continue "a shadowy version of life on earth". The only food or drink was dry dust, but family members of the deceased would pour libations for them to drink. In the Sumerian underworld, there was no final judgement of the deceased and the dead were neither punished nor rewarded for their deeds in life. A person's quality of existence in the underworld was determined by their conditions of burial. The ruler of the underworld was the goddess Ereshkigal, who lived in the palace Ganzir, sometimes used as a name for the underworld itself. Her husband was either Gugalanna, the "canal-inspector of Anu", or, especially in later stories, Nergal, the god of war. After the Akkadian Period ( 2334–2154 BC), Nergal s ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Inshushinak

Inshushinak (Linear Elamite: ''Inšušnak'', Cuneiform: , ''dinšušinakki''; possibly from Sumerian '' en-šušin-a ', "lord of Susa") was one of the major gods of the Elamites and the protector deity of Susa. He was called ''rišar napappair'', "greatest of gods" in some inscriptions. Character and cult Inshushinak is attested for the first time in the treaty of Naram-sin, much like many other Elamite gods. He played an important role as a god connected to royal power in the official ideology of many Elamite dynasties. King Atta-Hushu of the Sukkalmah dynasty called himself "the shepherd of the god Inshushinak." Multiple rulers dedicated new construction projects to Inshushinak using the formula "for his (eg. the king's) life." Shutrukids commonly used the title "(king) whose kingdom Inshushinak loves." He was also a divine witness of contracts, similar to Mesopotamian Shamash. Sometimes he shared this role with both Shamash and the Elamite god Simut in documents fro ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Gaṯaru

Gaṯaru (Ugaritic: ''gṯr'') or Gašru (Akkadian: '' dgaš-ru'', ''dga-aš-ru'') was a god worshiped in Ugarit, Emar and Mari in modern Syria, and in Opis in historical Babylonia in Iraq. While he is relatively sparsely attested, it is known that in Ugarit he was associated with the underworld, while in Mesopotamia he was understood as similar in character to Lugalirra or Erra. The name and cognates of it could also be used as an epithet of other deities, meaning "strong" or "powerful." The Ugaritic texts also attest the existence of dual and plural forms, Gaṯarāma and Gaṯarūma, used to refer to Gaṯaru himself in association with other deities, such as the moon god Yarikh and the sun goddess Shapash. In Ugarit The name of the god Gaṯaru (''gṯr'') is an ordinary Ugaritic adjective meaning "powerful," a cognate of Akkadian ''gašru'', "strong." No further cognates are known from any other Semitic languages. Gaṯaru was most likely associated with the underworl ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Mušḫuššu

The ''mušḫuššu'' (; formerly also read as or ) or mushkhushshu ( or ), is a creature from ancient Mesopotamian mythology. A mythological hybrid, it is a scaly animal with hind legs resembling the talons of an eagle, lion-like forelimbs, a long neck and tail, a horned head, a snake-like tongue, and a crest. The most famously appears on the reconstructed Ishtar Gate of the city of Babylon, dating to the sixth century BCE. The form is the Akkadian nominative of sux, MUŠ.ḪUŠ, 'reddish snake', sometimes also translated as 'fierce snake'. One author, possibly following others, translates it as 'splendor serpent' ( is the Sumerian term for 'serpent'). The reading is due to a mistransliteration of the cuneiform in early Assyriology. History Mušḫuššu already appears in Sumerian religion and art, as in the " Libation vase of Gudea", dedicated to Ningishzida by the Sumerian ruler Gudea (21st century BCE short chronology). The was the sacred animal of Marduk and ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Elamite Language

Elamite, also known as Hatamtite and formerly as Susian, is an extinct language that was spoken by the ancient Elamites. It was used in what is now southwestern Iran from 2600 BC to 330 BC. Elamite works disappear from the archeological record after Alexander the Great entered Iran. Elamite is generally thought to have no demonstrable relatives and is usually considered a language isolate. The lack of established relatives makes its interpretation difficult. A sizeable number of Elamite lexemes are known from the trilingual Behistun inscription and numerous other bilingual or trilingual inscriptions of the Achaemenid Empire, in which Elamite was written using Elamite cuneiform (circa 400 BC), which is fully deciphered. An important dictionary of the Elamite language, the ''Elamisches Wörterbuch'' was published in 1987 by W. Hinz and H. Koch. The Linear Elamite script however, one of the scripts used to write the Elamite language circa 2000 BC, has remained elusive until recen ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

_-_EnKi_(Sumerian).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)