|

SAE2 (yeast)

SAE2 is a gene in budding yeast, coding for the protein Sae2, which is involved in DNA repair. Sae2 is a part of the homologous recombination process in response to double-strand breaks. It is best characterized in the yeast model organism ''Saccharomyces cerevisiae''. Homologous genes in other organisms include Ctp1 in fission yeast, Com1 in plants, and CtIP in higher eukaryotes including humans. Sae2 and its homologs have relatively long low-complexity regions in their primary sequences and appear to have large intrinsically unstructured regions. Sae2 likely forms tetramers through coiled-coil sequences. Proteins of this family are DNA-binding proteins and are involved in DNA end resection and bridging at double-strand breaks. Sae2 has been reported to have endonuclease activity, though it has no bioinformatically recognizable nuclease A nuclease (also archaically known as nucleodepolymerase or polynucleotidase) is an enzyme capable of cleaving the phosphodiester bonds ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

UBA2

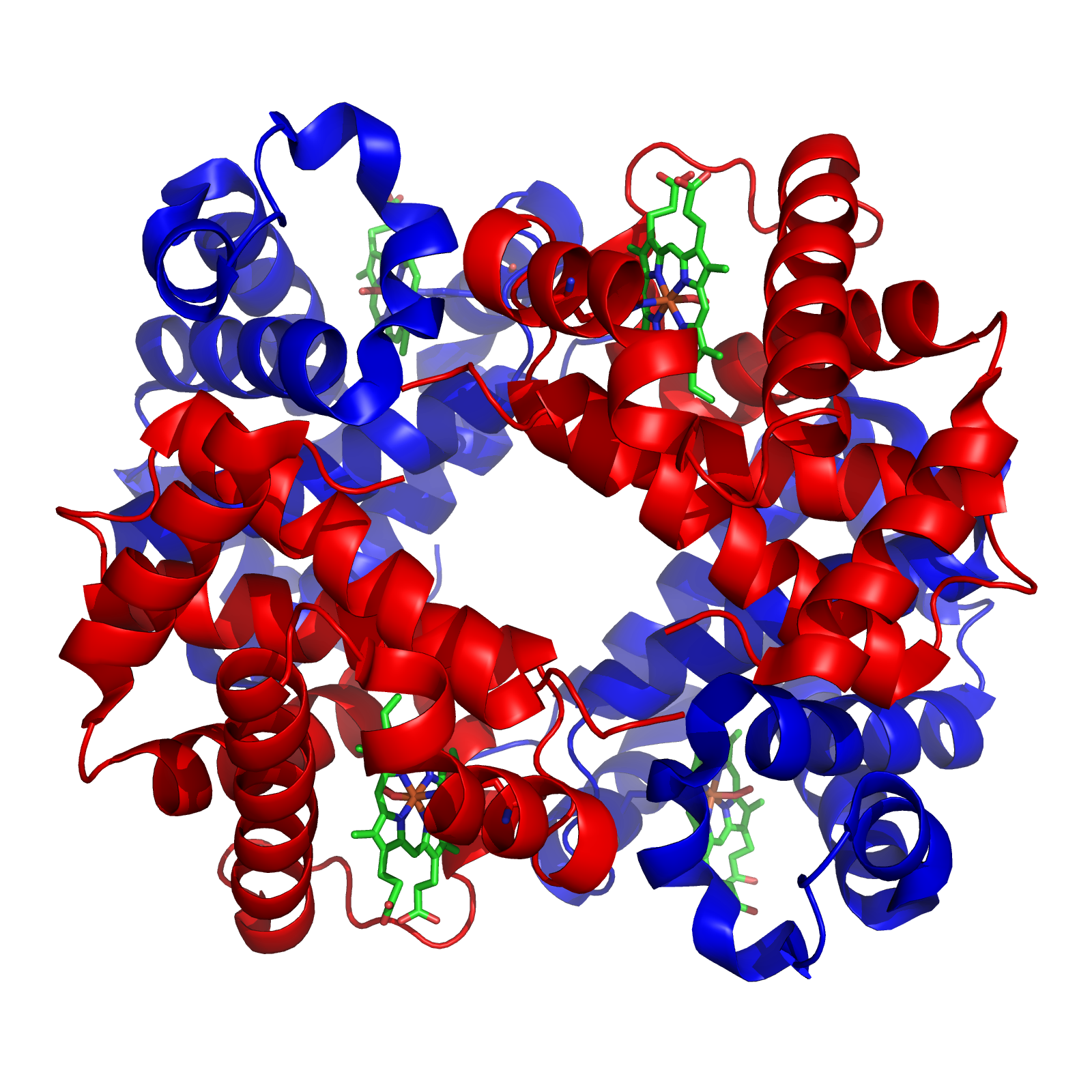

Ubiquitin-like 1-activating enzyme E1B (UBLE1B) also known as SUMO-activating enzyme subunit 2 (SAE2) is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the ''UBA2'' gene. Posttranslational modification of proteins by the addition of the small protein SUMO (see SUMO1), or sumoylation, regulates protein structure and intracellular localization. SAE1 and UBA2 form a heterodimer that functions as a SUMO-activating enzyme for the sumoylation of proteins. Structure DNA The UBA2 cDNA fragment 2683 bp long and encodes a peptide of 640 amino acids. The predicted protein sequence is more analogous to yeast UBA2 (35% identity) than human UBA3 or E1 (in ubiquitin pathway). The UBA gene is located on chromosome 19. Protein Uba2 subunit is 640 aa residues long with a molecular weight of 72 kDa. It consists of three domains: an adenylation domain (containing adenylation active site), a catalytic Cys domain (containing the catalytic Cys173 residue participated in thioester bond formation), and a ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Bioinformatics

Bioinformatics () is an interdisciplinary field that develops methods and software tools for understanding biological data, in particular when the data sets are large and complex. As an interdisciplinary field of science, bioinformatics combines biology, chemistry, physics, computer science, information engineering, mathematics and statistics to analyze and interpret the biological data. Bioinformatics has been used for '' in silico'' analyses of biological queries using computational and statistical techniques. Bioinformatics includes biological studies that use computer programming as part of their methodology, as well as specific analysis "pipelines" that are repeatedly used, particularly in the field of genomics. Common uses of bioinformatics include the identification of candidates genes and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Often, such identification is made with the aim to better understand the genetic basis of disease, unique adaptations, desirable properties (e ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Endonuclease

Endonucleases are enzymes that cleave the phosphodiester bond within a polynucleotide chain. Some, such as deoxyribonuclease I, cut DNA relatively nonspecifically (without regard to sequence), while many, typically called restriction endonucleases or restriction enzymes, cleave only at very specific nucleotide sequences. Endonucleases differ from exonucleases, which cleave the ends of recognition sequences instead of the middle (endo) portion. Some enzymes known as "exo-endonucleases", however, are not limited to either nuclease function, displaying qualities that are both endo- and exo-like. Evidence suggests that endonuclease activity experiences a lag compared to exonuclease activity. Restriction enzymes are endonucleases from eubacteria and archaea that recognize a specific DNA sequence. The nucleotide sequence recognized for cleavage by a restriction enzyme is called the restriction site. Typically, a restriction site will be a palindromic sequence about four to six nucleotides ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

DNA End Resection

DNA end resection, also called 5′–3′ degradation, is a biochemical process where the blunt end of a section of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) is modified by cutting away some nucleotides from the 5' end to produce a 3' single-stranded sequence. The presence of a section of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) allows the broken end of the DNA to line up accurately with a matching sequence, so that it can be accurately repaired.Double-strand breaks (DSBs) can occur at any phase of the cell cycle causing DNA end resection and repair activities to take place, but they are also normal intermediates in mitosis recombination. Furthermore, the natural ends of the linear chromosomes resemble DSBs, and although DNA breaks can cause damage to the integrity of genomic DNA, the natural ends are packed into complex specialized DNA protective packages called telomeres that prevent DNA repair activities. Telomeres and mitotic DSBs have different functionality, but both experience the same 5′–3′ d ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

DNA-binding Protein

DNA-binding proteins are proteins that have DNA-binding domains and thus have a specific or general affinity for DNA#Base pairing, single- or double-stranded DNA. Sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins generally interact with the major groove of B-DNA, because it exposes more functional groups that identify a base pair. However, there are some known minor groove DNA-binding ligands such as netropsin, distamycin, Hoechst 33258, pentamidine, DAPI and others. Examples DNA-binding proteins include transcription factors which Gene modulation, modulate the process of transcription, various polymerases, nucleases which cleave DNA molecules, and histones which are involved in chromosome packaging and transcription in the cell nucleus. DNA-binding proteins can incorporate such domains as the zinc finger, the helix-turn-helix, and the leucine zipper (among many others) that facilitate binding to nucleic acid. There are also more unusual examples such as TAL effector, transcription activa ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Coiled-coil

A coiled coil is a structural motif in proteins in which 2–7 alpha helix, alpha-helices are coiled together like the strands of a rope. (Protein dimer, Dimers and Protein trimer, trimers are the most common types.) Many coiled coil-type proteins are involved in important biological functions, such as the regulation of gene expression — e.g., transcription factors. Notable examples are the oncoproteins c-Fos and c-Jun, as well as the muscle protein tropomyosin. Discovery The possibility of coiled coils for α-keratin was initially somewhat controversial. Linus Pauling and Francis Crick independently came to the conclusion that this was possible at about the same time. In the summer of 1952, Pauling visited the laboratory in England where Crick worked. Pauling and Crick met and spoke about various topics; at one point, Crick asked whether Pauling had considered "coiled coils" (Crick came up with the term), to which Pauling said he had. Upon returning to the United States, Paul ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Tetramer

A tetramer () (''tetra-'', "four" + '' -mer'', "parts") is an oligomer formed from four monomers or subunits. The associated property is called ''tetramery''. An example from inorganic chemistry is titanium methoxide with the empirical formula Ti(OCH3)4, which is tetrameric in solid state and has the molecular formula Ti4(OCH3)16. An example from organic chemistry is kobophenol A, a substance that is formed by combining four molecules of resveratrol. In biochemistry, it similarly refers to a biomolecule formed of four units, that are the same (homotetramer), i.e. as in Concanavalin A or different (heterotetramer), i.e. as in hemoglobin. Hemoglobin has 4 similar sub-units while immunoglobulins have 2 very different sub-units. The different sub-units may have each their own activity, such as binding biotin in avidin tetramers, or have a common biological property, such as the allosteric binding of oxygen in hemoglobin. See also * Cluster chemistry; atomic and molecular clusters ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Intrinsically Unstructured Protein

In molecular biology, an intrinsically disordered protein (IDP) is a protein that lacks a fixed or ordered three-dimensional structure, typically in the absence of its macromolecular interaction partners, such as other proteins or RNA. IDPs range from fully unstructured to partially structured and include random coil, molten globule-like aggregates, or flexible linkers in large multi- domain proteins. They are sometimes considered as a separate class of proteins along with globular, fibrous and membrane proteins. IDPs are a very large and functionally important class of proteins and their discovery has disproved the idea that three-dimensional structures of proteins must be fixed to accomplish their biological functions. For example, IDPs have been identified to participate in weak multivalent interactions that are highly cooperative and dynamic, lending them importance in DNA regulation and in cell signaling. Many IDPs can also adopt a fixed three-dimensional structure after ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Primary Sequence

Biomolecular structure is the intricate folded, three-dimensional shape that is formed by a molecule of protein, DNA, or RNA, and that is important to its function. The structure of these molecules may be considered at any of several length scales ranging from the level of individual atoms to the relationships among entire protein subunits. This useful distinction among scales is often expressed as a decomposition of molecular structure into four levels: primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary. The scaffold for this multiscale organization of the molecule arises at the secondary level, where the fundamental structural elements are the molecule's various hydrogen bonds. This leads to several recognizable ''domains'' of protein structure and nucleic acid structure, including such secondary-structure features as alpha helixes and beta sheets for proteins, and hairpin loops, bulges, and internal loops for nucleic acids. The terms ''primary'', ''secondary'', ''tertiary'', and '' ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Low Complexity Regions In Proteins

Low complexity regions (LCRs) in protein sequences, also defined in some contexts as compositionally biased regions (CBRs), are regions in protein sequences that differ from the composition and complexity of most proteins that is normally associated with globular structure. LCRs have different properties from normal regions regarding structure, function and evolution Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation .... Structure LCRs were originally thought to be unstructured and flexible linkers that served to separate the structured (and functional) domains of complex proteins, but they are also capable of forming secondary structures, like helices (more often) and even sheets. They may play a structural role in proteins such as collagens, myosin, keratins, silk, cell wall protein ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Eukaryote

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacteria and Archaea (both prokaryotes) make up the other two domains. The eukaryotes are usually now regarded as having emerged in the Archaea or as a sister of the Asgard archaea. This implies that there are only two domains of life, Bacteria and Archaea, with eukaryotes incorporated among archaea. Eukaryotes represent a small minority of the number of organisms, but, due to their generally much larger size, their collective global biomass is estimated to be about equal to that of prokaryotes. Eukaryotes emerged approximately 2.3–1.8 billion years ago, during the Proterozoic eon, likely as flagellated phagotrophs. Their name comes from the Greek εὖ (''eu'', "well" or "good") and κάρυον (''karyon'', "nut" or "kernel"). Euka ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |