|

R. H. Fowler

Sir Ralph Howard Fowler (17 January 1889 – 28 July 1944) was a British physicist and astronomer. Education Fowler was born at Roydon, Essex, on 17 January 1889 to Howard Fowler, from Burnham, Somerset, and Frances Eva, daughter of George Dewhurst, a cotton merchant from Manchester. He was initially educated at home, going on to attend Evans' preparatory school at Horris Hill and Winchester College. He won a scholarship to Trinity College, Cambridge and studied mathematics, becoming a wrangler in Part II of the Mathematical Tripos. War service In World War I he obtained a commission in the Royal Marine Artillery and was seriously wounded in his shoulder in the Gallipoli campaign. The wound enabled his friend Archibald Hill to use his talents properly. As Hill's second in command he worked on anti-aircraft ballistics in the Anti-Aircraft Experimental Section of HMS ''Excellent'' on Whale Island. He made a major contribution on the aerodynamics of spinning shells. He was aw ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Roydon, Essex

Roydon is a village located in the Epping Forest district of the county of Essex, England. It is located 1.5 miles (2.4 km) west of Harlow, 3.5 miles (5.7 km) east of Hoddesdon and 4.6 miles (7.4 km) northwest of Epping, forming part of the border with Hertfordshire. The village lies on the Stort Navigation and River Stort. Roydon is recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086 as ''Ruindune'', and appears later as ''Reidona'' in ''c.'' 1130, as ''Reindon'' in 1204, and as ''Roindon'' in 1208. The village has a village shop, sub post office, pharmacy and church. The church, St Peter's, dates from the Middle Ages and was given Grade I listed status on 20 February 1967. Briggens House dating back to the 18th century was used as a forgery centre for the WW2 SOE. Transport Train The village is served by Roydon railway station on the West Anglia Main Line, with trains operated by Greater Anglia linking the village to London Liverpool Street and Cambridge. B ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Maurice Pryce

Maurice Henry Lecorney Pryce (24 January 1913 – 24 July 2003) was a British physicist. Pryce was born in Croydon to an Anglo-Welsh father and French mother, and in his teens attended the Royal Grammar School, Guildford. After a few months in Heidelberg to add German to the French that had been his first language at home, he went to Trinity College, Cambridge. In 1935 he went to Princeton University, supported by a Commonwealth Fund Fellowship (now Harkness Fellowship) where he worked with Wolfgang Pauli and John von Neumann, obtaining his Ph.D. with a thesis on ''The wave mechanics of the photon'' under the supervision of Max Born and Ralph Fowler. In 1937 he returned to England as a Fellow of Trinity, until in 1939 he was appointed Reader in Theoretical Physics at Liverpool University under James Chadwick. In 1941 he joined the Admiralty Signals Establishment (now part of the Admiralty Research Establishment) to work on radar. In 1944 he joined the British atomic energy team i ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Obituary Notices Of Fellows Of The Royal Society

The ''Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society'' is an academic journal on the history of science published annually by the Royal Society. It publishes obituaries of Fellows of the Royal Society. It was established in 1932 as ''Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society'' and obtained its current title in 1955, with volume numbering restarting at 1. Prior to 1932, obituaries were published in the '' Proceedings of the Royal Society''. The memoirs are a significant historical record and most include a full bibliography of works by the subjects. The memoirs are often written by a scientist of the next generation, often one of the subject's own former students, or a close colleague. In many cases the author is also a Fellow. Notable biographies published in this journal include Albert Einstein, Alan Turing, Bertrand Russell, Claude Shannon, Clement Attlee, Ernst Mayr, and Erwin Schrödinger. Each year around 40 to 50 memoirs of deceased Fellows of the Royal Societ ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Fellow Of The Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural knowledge, including mathematics, engineering science, and medical science". Fellowship of the Society, the oldest known scientific academy in continuous existence, is a significant honour. It has been awarded to many eminent scientists throughout history, including Isaac Newton (1672), Michael Faraday (1824), Charles Darwin (1839), Ernest Rutherford (1903), Srinivasa Ramanujan (1918), Albert Einstein (1921), Paul Dirac (1930), Winston Churchill (1941), Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar (1944), Dorothy Hodgkin (1947), Alan Turing (1951), Lise Meitner (1955) and Francis Crick (1959). More recently, fellowship has been awarded to Stephen Hawking (1974), David Attenborough (1983), Tim Hunt (1991), Elizabeth Blackburn (1992), Tim Berners-Lee (2001), Venki Ramakrishnan ( ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Royal Medal

The Royal Medal, also known as The Queen's Medal and The King's Medal (depending on the gender of the monarch at the time of the award), is a silver-gilt medal, of which three are awarded each year by the Royal Society, two for "the most important contributions to the advancement of natural knowledge" and one for "distinguished contributions in the applied sciences", done within the Commonwealth of Nations The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the .... Background The award was created by George IV and awarded first during 1826. Initially there were two medals awarded, both for the most important discovery within the year previous, a time period which was lengthened to five years and then shortened to three. The format was endorsed by William IV and Victoria, who had the con ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Adams Prize

The Adams Prize is one of the most prestigious prizes awarded by the University of Cambridge. It is awarded each year by the Faculty of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge and St John's College to a UK-based mathematician for distinguished research in the Mathematical Sciences. The prize is named after the mathematician John Couch Adams. It was endowed by members of St John's College and was approved by the senate of the university in 1848 to commemorate Adams' controversial role in the discovery of the planet Neptune. Originally open only to Cambridge graduates, the current stipulation is that the mathematician must reside in the UK and must be under forty years of age. Each year applications are invited from mathematicians who have worked in a specific area of mathematics. the Adams Prize is worth approximately £14,000. The prize is awarded in three parts. The first third is paid directly to the candidate; another third is paid to the candidate's institution to f ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Degenerate Matter

Degenerate matter is a highly dense state of fermionic matter in which the Pauli exclusion principle exerts significant pressure in addition to, or in lieu of, thermal pressure. The description applies to matter composed of electrons, protons, neutrons or other fermions. The term is mainly used in astrophysics to refer to dense stellar objects where gravitational pressure is so extreme that quantum mechanical effects are significant. This type of matter is naturally found in stars in their final evolutionary states, such as white dwarfs and neutron stars, where thermal pressure alone is not enough to avoid gravitational collapse. Degenerate matter is usually modelled as an ideal Fermi gas, an ensemble of non-interacting fermions. In a quantum mechanical description, particles limited to a finite volume may take only a discrete set of energies, called quantum states. The Pauli exclusion principle prevents identical fermions from occupying the same quantum state. At lowest total ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

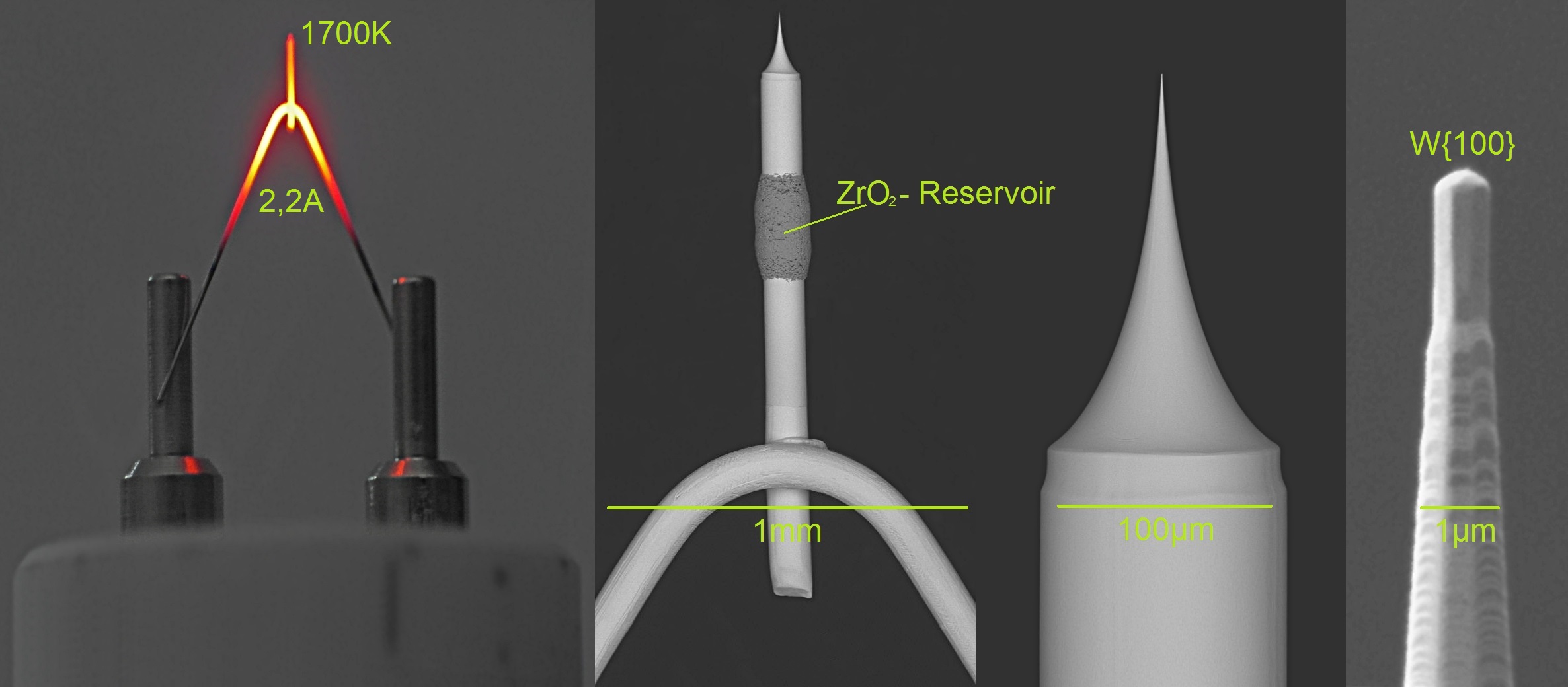

Field Electron Emission

Field electron emission, also known as field emission (FE) and electron field emission, is emission of electrons induced by an electrostatic field. The most common context is field emission from a solid surface into a vacuum. However, field emission can take place from solid or liquid surfaces, into a vacuum, a fluid (e.g. air), or any non-conducting or weakly conducting dielectric. The field-induced promotion of electrons from the valence to conduction band of semiconductors (the Zener effect) can also be regarded as a form of field emission. The terminology is historical because related phenomena of surface photoeffect, thermionic emission (or Richardson–Dushman effect) and "cold electronic emission", i.e. the emission of electrons in strong static (or quasi-static) electric fields, were discovered and studied independently from the 1880s to 1930s. When field emission is used without qualifiers it typically means "cold emission". Field emission in pure metals occurs in high el ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Bernal–Fowler Rules

In chemistry, ice rules are basic principles that govern arrangement of atoms in water ice. They are also known as Bernal–Fowler rules, after British physicists John Desmond Bernal and Ralph H. Fowler who first described them in 1933. The rules state each oxygen is covalently bonded to two hydrogen atoms, and that the oxygen atom in each water molecule forms two hydrogen bonds with other water molecules, so that there is precisely one hydrogen between each pair of oxygen atoms. In other words, in ordinary Ih ice, every oxygen is bonded to the total of four hydrogens, two of these bonds are strong and two of them are much weaker. Every hydrogen is bonded to two oxygens, strongly to one and weakly to the other. The resulting configuration is geometrically a periodic lattice. The distribution of bonds on this lattice is represented by a directed-graph (arrows) and can be either ordered or disordered. In 1935, Linus Pauling used the ice rules to calculate the residual entropy (zero ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Fowler–Nordheim Tunneling

Field electron emission, also known as field emission (FE) and electron field emission, is emission of electrons induced by an electrostatic field. The most common context is field emission from a solid surface into a vacuum. However, field emission can take place from solid or liquid surfaces, into a vacuum, a fluid (e.g. air), or any non-conducting or weakly conducting dielectric. The field-induced promotion of electrons from the valence to conduction band of semiconductors (the Zener effect) can also be regarded as a form of field emission. The terminology is historical because related phenomena of surface photoeffect, thermionic emission (or Richardson–Dushman effect) and "cold electronic emission", i.e. the emission of electrons in strong static (or quasi-static) electric fields, were discovered and studied independently from the 1880s to 1930s. When field emission is used without qualifiers it typically means "cold emission". Field emission in pure metals occurs in ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Fowler–Nordheim-type Equations

Field electron emission, also known as field emission (FE) and electron field emission, is emission of electrons induced by an electrostatic field. The most common context is field emission from a solid surface into a vacuum. However, field emission can take place from solid or liquid surfaces, into a vacuum, a fluid (e.g. air), or any non-conducting or weakly conducting dielectric. The field-induced promotion of electrons from the valence to conduction band of semiconductors (the Zener effect) can also be regarded as a form of field emission. The terminology is historical because related phenomena of surface photoeffect, thermionic emission (or Richardson–Dushman effect) and "cold electronic emission", i.e. the emission of electrons in strong static (or quasi-static) electric fields, were discovered and studied independently from the 1880s to 1930s. When field emission is used without qualifiers it typically means "cold emission". Field emission in pure metals occurs in high ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |