|

Pyruvate Decarboxylase

Pyruvate decarboxylase is an enzyme () that catalyses the decarboxylation of pyruvic acid to acetaldehyde. It is also called 2-oxo-acid carboxylase, alpha-ketoacid carboxylase, and pyruvic decarboxylase. In anaerobic conditions, this enzyme is participates in the fermentation process that occurs in yeast, especially of the genus ''Saccharomyces'', to produce ethanol by fermentation. It is also present in some species of fish (including goldfish and carp) where it permits the fish to perform ethanol fermentation (along with lactic acid fermentation) when oxygen is scarce. Pyruvate decarboxylase starts this process by converting pyruvate into acetaldehyde and carbon dioxide. Pyruvate decarboxylase depends on cofactors thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP) and magnesium. This enzyme should not be mistaken for the unrelated enzyme pyruvate dehydrogenase, an oxidoreductase (), that catalyzes the oxidative decarboxylation of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA. Structure Pyruvate decarboxylase occurs ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as product (chemistry), products. Almost all metabolism, metabolic processes in the cell (biology), cell need enzyme catalysis in order to occur at rates fast enough to sustain life. Metabolic pathways depend upon enzymes to catalyze individual steps. The study of enzymes is called ''enzymology'' and the field of pseudoenzyme, pseudoenzyme analysis recognizes that during evolution, some enzymes have lost the ability to carry out biological catalysis, which is often reflected in their amino acid sequences and unusual 'pseudocatalytic' properties. Enzymes are known to catalyze more than 5,000 biochemical reaction types. Other biocatalysts are Ribozyme, catalytic RNA molecules, called ribozymes. Enzymes' Chemical specificity, specific ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Yeast

Yeasts are eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms classified as members of the fungus kingdom. The first yeast originated hundreds of millions of years ago, and at least 1,500 species are currently recognized. They are estimated to constitute 1% of all described fungal species. Yeasts are unicellular organisms that evolved from multicellular ancestors, with some species having the ability to develop multicellular characteristics by forming strings of connected budding cells known as pseudohyphae or false hyphae. Yeast sizes vary greatly, depending on species and environment, typically measuring 3–4 µm in diameter, although some yeasts can grow to 40 µm in size. Most yeasts reproduce asexually by mitosis, and many do so by the asymmetric division process known as budding. With their single-celled growth habit, yeasts can be contrasted with molds, which grow hyphae. Fungal species that can take both forms (depending on temperature or other conditions) are ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Enol

In organic chemistry, alkenols (shortened to enols) are a type of reactive structure or intermediate in organic chemistry that is represented as an alkene (olefin) with a hydroxyl group attached to one end of the alkene double bond (). The terms ''enol'' and ''alkenol'' are portmanteaus deriving from "-ene"/"alkene" and the "-ol" suffix indicating the hydroxyl group of alcohols, dropping the terminal "-e" of the first term. Generation of enols often involves removal of a hydrogen adjacent (α-) to the carbonyl group—i.e., deprotonation, its removal as a proton, . When this proton is not returned at the end of the stepwise process, the result is an anion termed an enolate (see images at right). The enolate structures shown are schematic; a more modern representation considers the molecular orbitals that are formed and occupied by electrons in the enolate. Similarly, generation of the enol often is accompanied by "trapping" or masking of the hydroxy group as an ether, such as ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Pyruvate Decarboxylase Mechanism

Pyruvic acid (CH3COCOOH) is the simplest of the alpha-keto acids, with a carboxylic acid and a ketone functional group. Pyruvate, the conjugate base, CH3COCOO−, is an intermediate in several metabolic pathways throughout the cell. Pyruvic acid can be made from glucose through glycolysis, converted back to carbohydrates (such as glucose) via gluconeogenesis, or to fatty acids through a reaction with acetyl-CoA. It can also be used to construct the amino acid alanine and can be converted into ethanol or lactic acid via fermentation. Pyruvic acid supplies energy to cells through the citric acid cycle (also known as the Krebs cycle) when oxygen is present (aerobic respiration), and alternatively ferments to produce lactate when oxygen is lacking. Chemistry In 1834, Théophile-Jules Pelouze distilled tartaric acid and isolated glutaric acid and another unknown organic acid. Jöns Jacob Berzelius characterized this other acid the following year and named pyruvic acid because it ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Nucleophile

In chemistry, a nucleophile is a chemical species that forms bonds by donating an electron pair. All molecules and ions with a free pair of electrons or at least one pi bond can act as nucleophiles. Because nucleophiles donate electrons, they are Lewis bases. ''Nucleophilic'' describes the affinity of a nucleophile to bond with positively charged atomic nuclei. Nucleophilicity, sometimes referred to as nucleophile strength, refers to a substance's nucleophilic character and is often used to compare the affinity of atoms. Neutral nucleophilic reactions with solvents such as alcohols and water are named solvolysis. Nucleophiles may take part in nucleophilic substitution, whereby a nucleophile becomes attracted to a full or partial positive charge, and nucleophilic addition. Nucleophilicity is closely related to basicity. History The terms ''nucleophile'' and ''electrophile'' were introduced by Christopher Kelk Ingold in 1933, replacing the terms ''anionoid'' and ''cation ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Carbanion

In organic chemistry, a carbanion is an anion in which carbon is trivalent (forms three bonds) and bears a formal negative charge (in at least one significant resonance form). Formally, a carbanion is the conjugate base of a carbon acid: :R3CH\, + \ddot^- -> \mathbf + HB where B stands for the base. The carbanions formed from deprotonation of alkanes (at an sp3 carbon), alkenes (at an sp2 carbon), arenes (at an sp2 carbon), and alkynes (at an sp carbon) are known as alkyl, alkenyl (vinyl), aryl, and alkynyl ( acetylide) anions, respectively. Carbanions have a concentration of electron density at the negatively charged carbon, which, in most cases, reacts efficiently with a variety of electrophiles of varying strengths, including carbonyl groups, imines/ iminium salts, halogenating reagents (e.g., ''N''-bromosuccinimide and diiodine), and proton donors. A carbanion is one of several reactive intermediates in organic chemistry. In organic synthesis, organolithium reagents an ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Prosthetic Group

A prosthetic group is the non-amino acid component that is part of the structure of the heteroproteins or conjugated proteins, being tightly linked to the apoprotein. Not to be confused with the cofactor that binds to the enzyme apoenzyme (either a holoprotein or heteroprotein) by non-covalent binding a non-protein (non-amino acid) This is a component of a conjugated protein that is required for the protein's biological activity. The prosthetic group may be organic (such as a vitamin, sugar, RNA, phosphate or lipid) or inorganic (such as a metal ion). Prosthetic groups are bound tightly to proteins and may even be attached through a covalent bond. They often play an important role in enzyme catalysis. A protein without its prosthetic group is called an apoprotein, while a protein combined with its prosthetic group is called a holoprotein. A non-covalently bound prosthetic group cannot generally be removed from the holoprotein without denaturating the protein. Thus, the term ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Regulatory Site

In biochemistry, allosteric regulation (or allosteric control) is the regulation of an enzyme by binding an effector molecule at a site other than the enzyme's active site. The site to which the effector binds is termed the ''allosteric site'' or ''regulatory site''. Allosteric sites allow effectors to bind to the protein, often resulting in a conformational change and/or a change in protein dynamics. Effectors that enhance the protein's activity are referred to as ''allosteric activators'', whereas those that decrease the protein's activity are called ''allosteric inhibitors''. Allosteric regulations are a natural example of control loops, such as feedback from downstream products or feedforward from upstream substrates. Long-range allostery is especially important in cell signaling. Allosteric regulation is also particularly important in the cell's ability to adjust enzyme activity. The term ''allostery'' comes from the Ancient Greek ''allos'' (), "other", and ''stereos' ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Conformational Change

In biochemistry, a conformational change is a change in the shape of a macromolecule, often induced by environmental factors. A macromolecule is usually flexible and dynamic. Its shape can change in response to changes in its environment or other factors; each possible shape is called a conformation, and a transition between them is called a ''conformational change''. Factors that may induce such changes include temperature, pH, voltage, light in chromophores, concentration of ions, phosphorylation, or the binding of a ligand. Transitions between these states occur on a variety of length scales (tenths of Å to nm) and time scales (ns to s), and have been linked to functionally relevant phenomena such as allosteric signaling and enzyme catalysis. Laboratory analysis Many biophysical techniques such as crystallography, NMR, electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) using spin label techniques, circular dichroism (CD), hydrogen exchange, and FRET can be used to study macr ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

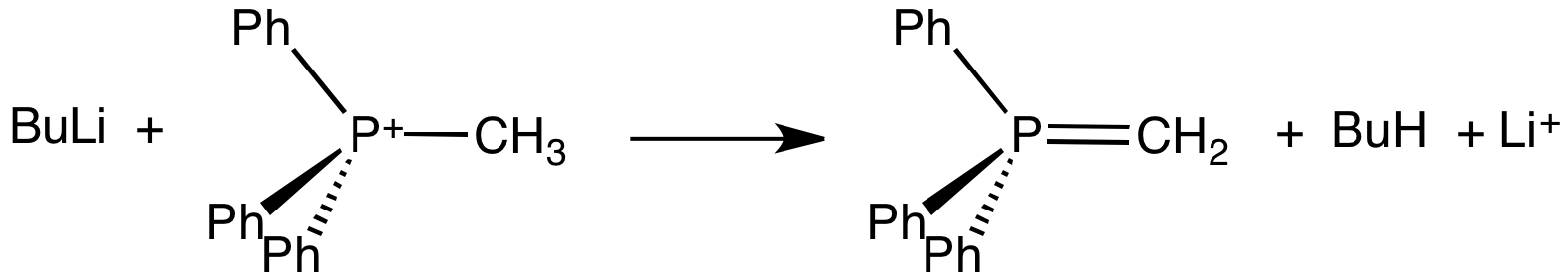

Ylide

An ylide or ylid () is a neutral dipolar molecule containing a formally negatively charged atom (usually a carbanion) directly attached to a heteroatom with a formal positive charge (usually nitrogen, phosphorus or sulfur), and in which both atoms have full octets of electrons. The result can be viewed as a structure in which two adjacent atoms are connected by both a covalent and an ionic bond; normally written X+–Y−. Ylides are thus 1,2- dipolar compounds, and a subclass of zwitterions. They appear in organic chemistry as reagents or reactive intermediates. The class name "ylide" for the compound should not be confused with the suffix "-ylide". Resonance structures Many ylides may be depicted by a multiple bond form in a resonance structure, known as the ylene form, while the actual structure lies in between both forms: : The actual bonding picture of these types of ylides is strictly zwitterionic (the structure on the right) with the strong Coulombic attraction betw ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Acetyl-CoA

Acetyl-CoA (acetyl coenzyme A) is a molecule that participates in many biochemical reactions in protein, carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. Its main function is to deliver the acetyl group to the citric acid cycle (Krebs cycle) to be oxidized for energy production. Coenzyme A (CoASH or CoA) consists of a β-mercaptoethylamine group linked to the vitamin pantothenic acid (B5) through an amide linkage and 3'-phosphorylated ADP. The acetyl group (indicated in blue in the structural diagram on the right) of acetyl-CoA is linked to the sulfhydryl substituent of the β-mercaptoethylamine group. This thioester linkage is a "high energy" bond, which is particularly reactive. Hydrolysis of the thioester bond is exergonic (−31.5 kJ/mol). CoA is acetylated to acetyl-CoA by the breakdown of carbohydrates through glycolysis and by the breakdown of fatty acids through β-oxidation. Acetyl-CoA then enters the citric acid cycle, where the acetyl group is oxidized to carbon dioxid ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |