|

Gigantothermy

Gigantothermy (sometimes called ectothermic homeothermy or inertial homeothermy) is a phenomenon with significance in biology and paleontology, whereby large, bulky ectothermic animals are more easily able to maintain a constant, relatively high body temperature than smaller animals by virtue of their smaller surface-area-to-volume ratio. A bigger animal has proportionately less of its body close to the outside environment than a smaller animal of otherwise similar shape, and so it gains heat from, or loses heat to, the environment much more slowly. The phenomenon is important in the biology of ectothermic megafauna, such as large turtles, and aquatic reptiles like ichthyosaurs and mosasaurs. Gigantotherms, though almost always ectothermic, generally have a body temperature similar to that of endotherms. It has been suggested that the larger dinosaurs would have been gigantothermic, rendering them virtually homeothermic. Disadvantages Gigantothermy allows animals to maintain body ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Surface-area-to-volume Ratio

The surface-area-to-volume ratio, also called the surface-to-volume ratio and variously denoted sa/vol or SA:V, is the amount of surface area per unit volume of an object or collection of objects. SA:V is an important concept in science and engineering. It is used to explain the relation between structure and function in processes occurring through the surface ''and'' the volume. Good examples for such processes are processes governed by the heat equation, i.e., diffusion and heat transfer by conduction. SA:V is used to explain the diffusion of small molecules, like oxygen and carbon dioxide between air, blood and cells, water loss by animals, bacterial morphogenesis, organism's thermoregulation, design of artificial bone tissue, artificial lungs and many more biological and biotechnological structures. For more examples see Glazier. The relation between SA:V and diffusion or heat conduction rate is explained from flux and surface perspective, focusing on the surface of a body a ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Physiology Of Dinosaurs

The physiology of dinosaurs has historically been a controversial subject, particularly their thermoregulation. Recently, many new lines of evidence have been brought to bear on dinosaur physiology generally, including not only metabolic systems and thermoregulation, but on respiratory and cardiovascular systems as well. During the early years of dinosaur paleontology, it was widely considered that they were sluggish, cumbersome, and sprawling cold-blooded lizards. However, with the discovery of much more complete skeletons in western United States, starting in the 1870s, scientists could make more informed interpretations of dinosaur biology and physiology. Edward Drinker Cope, opponent of Othniel Charles Marsh in the Bone Wars, propounded at least some dinosaurs as active and agile, as seen in the painting of two fighting '' Laelaps'' produced under his direction by Charles R. Knight. In parallel, the development of Darwinian evolution, and the discoveries of '' Archaeoptery ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Homeotherm

Homeothermy, homothermy or homoiothermy is thermoregulation that maintains a stable internal body temperature regardless of external influence. This internal body temperature is often, though not necessarily, higher than the immediate environment (from Greek ὅμοιος ''homoios'' "similar" and θέρμη ''thermē'' "heat"). Homeothermy is one of the three types of thermoregulation in warm-blooded animal species. Homeothermy's opposite is poikilothermy. A poikilotherm is an organism that does not maintain a fixed internal temperature but rather fluctuates based on their environment and physical behaviour. Homeotherms are ''not'' necessarily endothermic. Some homeotherms may maintain constant body temperatures through behavioral mechanisms alone, ''i.e.'', behavioral thermoregulation. Many reptiles use this strategy. For example, desert lizards are remarkable in that they maintain near-constant activity temperatures that are often within a degree or two of their lethal critic ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

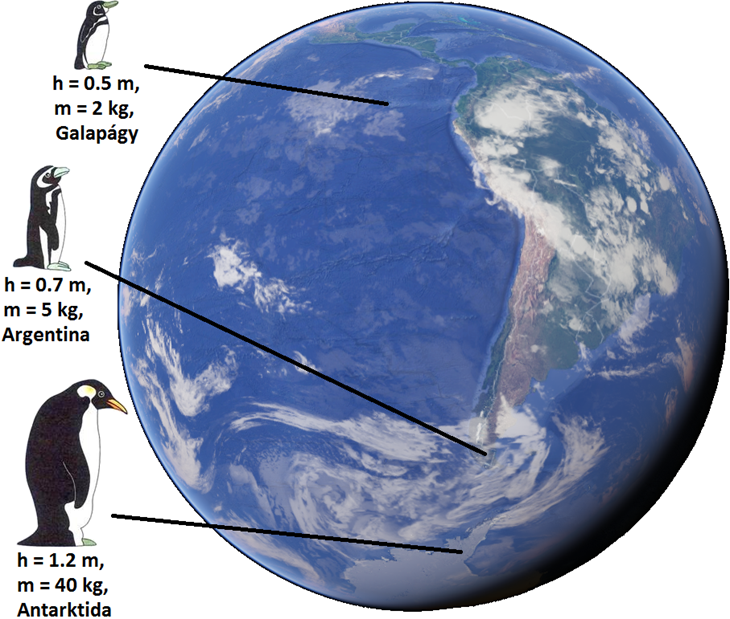

Bergmann's Rule

Bergmann's rule is an ecogeographical rule that states that within a broadly distributed taxonomic clade, populations and species of larger size are found in colder environments, while populations and species of smaller size are found in warmer regions. Bergmann's rule only describes the overall size of the animals, but does not include body parts like Allen's rule does. Although originally formulated in relation to species within a genus, it has often been recast in relation to populations within a species. It is also often cast in relation to latitude. It is possible that the rule also applies to some plants, such as '' Rapicactus''. The rule is named after nineteenth century German biologist Carl Bergmann, who described the pattern in 1847, although he was not the first to notice it. Bergmann's rule is most often applied to mammals and birds which are endotherms, but some researchers have also found evidence for the rule in studies of ectothermic species, such as the ant ''L ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Biology

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditary information encoded in genes, which can be transmitted to future generations. Another major theme is evolution, which explains the unity and diversity of life. Energy processing is also important to life as it allows organisms to move, grow, and reproduce. Finally, all organisms are able to regulate their own internal environments. Biologists are able to study life at multiple levels of organization, from the molecular biology of a cell to the anatomy and physiology of plants and animals, and evolution of populations.Based on definition from: Hence, there are multiple subdisciplines within biology, each defined by the nature of their research questions and the tools that they use. Like other scientists, biologists use the sc ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Animal Physiology

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemical and physical functions in a living system. According to the classes of organisms, the field can be divided into medical physiology, animal physiology, plant physiology, cell physiology, and comparative physiology. Central to physiological functioning are biophysical and biochemical processes, homeostatic control mechanisms, and communication between cells. ''Physiological state'' is the condition of normal function. In contrast, ''pathological state'' refers to abnormal conditions, including human diseases. The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is awarded by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for exceptional scientific achievements in physiology related to the field of medicine. Foundations Cells Although there are differences ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Tachyaerobic

Tachyaerobic is a term used in biology to describe the muscles of large animals and birds that are able to maintain high levels or physical activity because their hearts make up at least 0.5-0.6 percent of their body mass and maintain high blood pressures. A reptile displaying equal size to a tachyaerobic mammal does not have the same capabilities. Tachyaerobic animals' hearts beat more quickly, produce more oxygen, and distribute blood at a quicker rate than reptiles. The use of tachyaerobic muscles is important to animals such as giraffes that need blood circulated through a large body size quickly. See also * Bradyaerobic Bradyaerobic is a term used in biology that describes an animal that has low levels of oxygen consumption. By necessity a bradyaerobic animal can engage in short low or high low-level aerobic exercise Aerobic exercise (also known as endurance ... References {{Reflist Muscular system Thermoregulation ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Bradymetabolism

Bradymetabolism refers to organisms with a high active metabolism and a considerably slower resting metabolism.Bligh, J., and Johnson, K.G., 1973. Glossary for terms for thermal physiology. ''Journal of Applied Physiology'' 35(6):941–961. Bradymetabolic animals can often undergo dramatic changes in metabolic speed, according to food availability and temperature. Many bradymetabolic creatures in deserts and in areas that experience extreme winters are capable of "shutting down" their metabolisms to approach near-death states, until favorable conditions return (see hibernation and estivation). Several variants of bradymetabolism exists. In mammals, the animals normally have a fairly high metabolism, only dropping to low levels in times of little food. In most reptiles, the normal metabolic rate is quite low, but can be raised when needed, typically in short bursts of activity in connection with capturing prey. Etymology The term is from Greek ''brady'' (βραδύ) "slow" and ''me ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Bradyaerobic

Bradyaerobic is a term used in biology that describes an animal that has low levels of oxygen consumption. By necessity a bradyaerobic animal can engage in short low or high low-level aerobic exercise Aerobic exercise (also known as endurance activities, cardio or cardio-respiratory exercise) is physical exercise of low to high intensity that depends primarily on the aerobic energy-generating process. "Aerobic" is defined as "relating to, inv ..., followed by brief anaerobically powered bursts of energy. Bradyaerobes can be sprinters, but not long-distance animals. References {{Reflist Thermoregulation ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Allen's Rule

Allen's rule is an ecogeographical rule formulated by Joel Asaph Allen in 1877, broadly stating that animals adapted to cold climates have thicker limbs and bodily appendages than animals adapted to warm climates. More specifically, it states that the body surface-area-to-volume ratio for homeothermic animals varies with the average temperature of the habitat to which they are adapted (i.e. the ratio is low in cold climates and high in hot climates). Explanation Allen's rule predicts that endothermic animals with the same body volume should have different surface areas that will either aid or impede their heat dissipation. Because animals living in cold climates need to conserve as much heat as possible, Allen's rule predicts that they should have evolved comparatively low surface area-to-volume ratios to minimize the surface area by which they dissipate heat, allowing them to retain more heat. For animals living in warm climates, Allen's rule predicts the opposite: that they shou ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Adenosine Triphosphate

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is an organic compound that provides energy to drive many processes in living cells, such as muscle contraction, nerve impulse propagation, condensate dissolution, and chemical synthesis. Found in all known forms of life, ATP is often referred to as the "molecular unit of currency" of intracellular energy transfer. When consumed in metabolic processes, it converts either to adenosine diphosphate (ADP) or to adenosine monophosphate (AMP). Other processes regenerate ATP. The human body recycles its own body weight equivalent in ATP each day. It is also a precursor to DNA and RNA, and is used as a coenzyme. From the perspective of biochemistry, ATP is classified as a nucleoside triphosphate, which indicates that it consists of three components: a nitrogenous base (adenine), the sugar ribose, and the Polyphosphate, triphosphate. Structure ATP consists of an adenine attached by the 9-nitrogen atom to the 1′ carbon atom of a sugar (ribose), which i ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Mitochondria

A mitochondrion (; ) is an organelle found in the Cell (biology), cells of most Eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and Fungus, fungi. Mitochondria have a double lipid bilayer, membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is used throughout the cell as a source of chemical energy. They were discovered by Albert von Kölliker in 1857 in the voluntary muscles of insects. The term ''mitochondrion'' was coined by Carl Benda in 1898. The mitochondrion is popularly nicknamed the "powerhouse of the cell", a phrase coined by Philip Siekevitz in a 1957 article of the same name. Some cells in some multicellular organisms lack mitochondria (for example, mature mammalian red blood cells). A large number of unicellular organisms, such as microsporidia, parabasalids and diplomonads, have reduced or transformed their mitochondria into mitosome, other structures. One eukaryote, ''Monocercomonoides'', is known to have completely lost its mitocho ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |