|

DRIP-seq

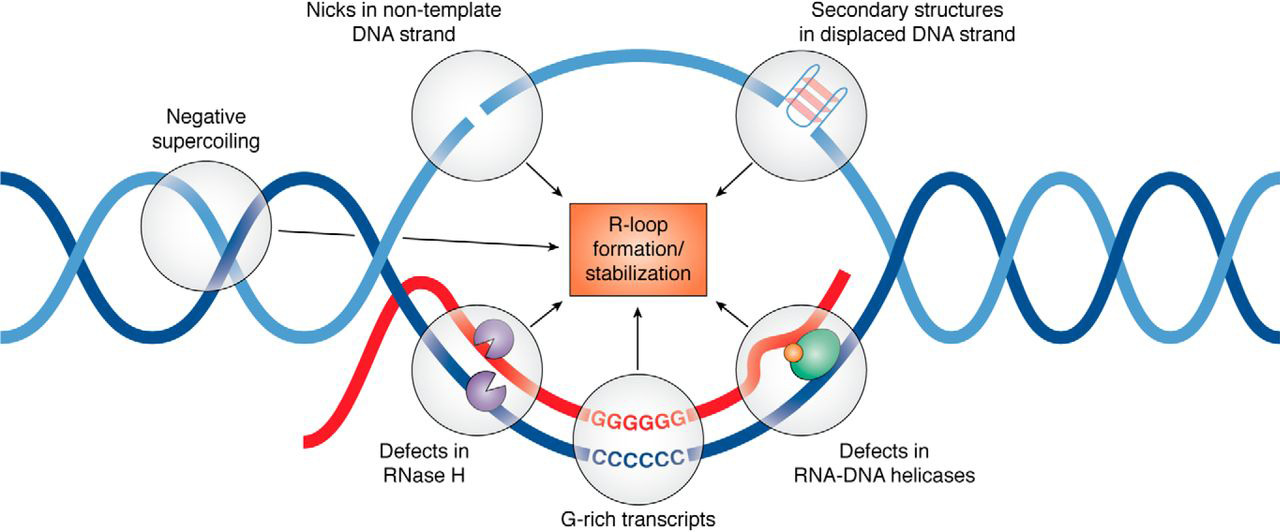

DRIP-seq (DRIP-sequencing) is a technology for genome-wide profiling of a type of DNA-RNA hybrid called an "R-loop". DRIP-seq utilizes a sequence-independent but structure-specific antibody for DNA-RNA immunoprecipitation (DRIP) to capture R-loops for massively parallel DNA sequencing. Introduction An R-loop is a three-stranded nucleic acid structure, which consists of a DNA-RNA hybrid duplex and a displaced single stranded DNA (ssDNA). R-loops are predominantly formed in cytosine-rich genomic regions during transcription and are known to be involved with gene expression and immunoglobulin class switching. They have been found in a variety of species, ranging from bacteria to mammals. They are preferentially localized at CpG island promoters in human cells and highly transcribed regions in yeast. Under abnormal conditions, namely elevated production of DNA-RNA hybrids, R-loops can cause genome instability by exposing single-stranded DNA to endogenous damages exerted by the action ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

R-loop

An R-loop is a three-stranded nucleic acid structure, composed of a DNA:RNA hybrid and the associated non-template single-stranded DNA. R-loops may be formed in a variety of circumstances, and may be tolerated or cleared by cellular components. The term "R-loop" was given to reflect the similarity of these structures to D-loops; the "R" in this case represents the involvement of an RNA moiety. In the laboratory, R-loops may also be created by the hybridization of mature mRNA with double-stranded DNA under conditions favoring the formation of a DNA-RNA hybrid; in this case, the intron regions (which have been spliced out of the mRNA) form single-stranded DNA loops, as they cannot hybridize with complementary sequence in the mRNA. History R-looping was first described in 1976. Independent R-looping studies from the laboratories of Richard J. Roberts and Phillip A. Sharp showed that protein coding adenovirus genes contained DNA sequences that were not present in the mature mRNA. ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

ChIP-sequencing

ChIP-sequencing, also known as ChIP-seq, is a method used to analyze protein interactions with DNA. ChIP-seq combines chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) with massively parallel DNA sequencing to identify the binding sites of DNA-associated proteins. It can be used to map global binding sites precisely for any protein of interest. Previously, ChIP-on-chip was the most common technique utilized to study these protein–DNA relations. Uses ChIP-seq is primarily used to determine how transcription factors and other chromatin-associated proteins influence phenotype-affecting mechanisms. Determining how proteins interact with DNA to regulate gene expression is essential for fully understanding many biological processes and disease states. This epigenetic information is complementary to genotype and expression analysis. ChIP-seq technology is currently seen primarily as an alternative to ChIP-chip which requires a hybridization array. This introduces some bias, as an array is restrict ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Protein G

Protein G is an immunoglobulin-binding protein expressed in group C and G Streptococcal bacteria much like Protein A but with differing binding specificities. It is a ~60-kDA (65 kDA for strain G148 and 58 kDa for strain C40) cell surface protein that has found application in purifying antibodies through its binding to the Fab and Fc region. The native molecule also binds albumin, but because serum albumin is a major contaminant of antibody sources, the albumin binding site has been removed from recombinant forms of Protein G. This recombinant Protein G, either labeled with a fluorophore or a single-stranded DNA strand, was used as a replacement for secondary antibodies in immunofluorescence and super-resolution imaging. Other antibody binding proteins In addition to Protein G, other immunoglobulin-binding bacterial proteins such as Protein A, Protein A/G and Protein L are all commonly used to purify, immobilize or detect immunoglobulins. Each of these immunoglobulin-binding ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Protein A

Protein A is a 42 kDa surface protein originally found in the cell wall of the bacteria ''Staphylococcus aureus''. It is encoded by the ''spa'' gene and its regulation is controlled by DNA topology, cellular osmolarity, and a two-component system called ArlS-ArlR. It has found use in biochemical research because of its ability to bind immunoglobulins. It is composed of five homologous Ig-binding domains that fold into a three-helix bundle. Each domain is able to bind proteins from many mammalian species, most notably IgGs. It binds the heavy chain within the Fc region of most immunoglobulins and also within the Fab region in the case of the human VH3 family. Through these interactions in serum, where IgG molecules are bound in the wrong orientation (in relation to normal antibody function), the bacteria disrupts opsonization and phagocytosis. History As a by-product of his work on type-specific staphylococcus antigens, Verwey reported in 1940 that a protein fraction prepared from ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as regulatory sequences (see non-coding DNA), and often a substantial fraction of 'junk' DNA with no evident function. Almost all eukaryotes have mitochondria and a small mitochondrial genome. Algae and plants also contain chloroplasts with a chloroplast genome. The study of the genome is called genomics. The genomes of many organisms have been sequenced and various regions have been annotated. The International Human Genome Project reported the sequence of the genome for ''Homo sapiens'' in 200The Human Genome Project although the initial "finished" sequence was missing 8% of the genome consisting mostly of repetitive sequences. With advancements in technology that could handle sequenci ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Sonication

A sonicator at the Weizmann Institute of Science during sonicationSonication is the act of applying sound energy to agitate particles in a sample, for various purposes such as the extraction of multiple compounds from plants, microalgae and seaweeds. Ultrasonic frequencies (> 20 kHz) are usually used, leading to the process also being known as ultrasonication or ultra-sonication. In the laboratory, it is usually applied using an ''ultrasonic bath'' or an ''ultrasonic probe'', colloquially known as a ''sonicator''. In a paper machine, an ultrasonic foil can distribute cellulose fibres more uniformly and strengthen the paper. Effects Sonication has numerous effects, both chemical and physical. The chemical effects of ultrasound are concerned with understanding the effect of sonic waves on chemical systems, this is called sonochemistry. The chemical effects of ultrasound do not come from a direct interaction with molecular species. Studies have shown that no direct coupl ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Restriction Enzyme

A restriction enzyme, restriction endonuclease, REase, ENase or'' restrictase '' is an enzyme that cleaves DNA into fragments at or near specific recognition sites within molecules known as restriction sites. Restriction enzymes are one class of the broader endonuclease group of enzymes. Restriction enzymes are commonly classified into five types, which differ in their structure and whether they cut their DNA substrate at their recognition site, or if the recognition and cleavage sites are separate from one another. To cut DNA, all restriction enzymes make two incisions, once through each sugar-phosphate backbone (i.e. each strand) of the DNA double helix. These enzymes are found in bacteria and archaea and provide a defense mechanism against invading viruses. Inside a prokaryote, the restriction enzymes selectively cut up ''foreign'' DNA in a process called ''restriction digestion''; meanwhile, host DNA is protected by a modification enzyme (a methyltransferase) that modifi ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Aspergillus Nuclease S1

Nuclease S1 () is an endonuclease enzyme that splits single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) and RNA into oligo- or mononucleotides. This enzyme catalyses the following chemical reaction : Endonucleolytic cleavage to 5'-phosphomononucleotide and 5'-phosphooligonucleotide end-products Although its primary substrate is single-stranded, it can also occasionally introduce single-stranded breaks in double-stranded DNA or RNA, or DNA-RNA hybrids. The enzyme hydrolyses single stranded region in duplex DNA such as loops or gaps. It also cleaves a strand opposite a nick on the complementary strand. It has no sequence specificity. Well-known versions include S1 found in ''Aspergillus oryzae'' (yellow koji mold) and Nuclease P1 found in ''Penicillium citrinum''. Members of the S1/P1 family are found in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes and are thought to be associated in programmed cell death and also in tissue differentiation. Furthermore, they are secreted extracellular, that is, outside of the cel ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Spin Column-based Nucleic Acid Purification

Spin column-based nucleic acid purification is a solid phase extraction method to quickly purify nucleic acids. This method relies on the fact that nucleic acid will bind to the solid phase of silica under certain conditions. Procedure The stages of the method are lyse, bind, wash, and elute. More specifically, this entails the lysis of target cells to release nucleic acids, selective binding of nucleic acid to a silica membrane, washing away particulates and inhibitors that are not bound to the silica membrane, and elution of the nucleic acid, with the end result being purified nucleic acid in an aqueous solution. For lysis, the cells (blood, tissue, etc.) of the sample must undergo a treatment to break the cell membrane and free the nucleic acid. Depending on the target material, this can include the use of detergent or other buffers, proteinases or other enzymes, heating to various times/temperatures, or mechanical disruption such as cutting with a knife or homogenizer, using ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Proteinase K

In molecular biology Proteinase K (, ''protease K'', ''endopeptidase K'', ''Tritirachium alkaline proteinase'', ''Tritirachium album serine proteinase'', ''Tritirachium album proteinase K'') is a broad-spectrum serine protease. The enzyme was discovered in 1974 in extracts of the fungus ''Engyodontium album'' (formerly '' Tritirachium album''). Proteinase K is able to digest hair (keratin), hence, the name "Proteinase K". The predominant site of cleavage is the peptide bond adjacent to the carboxyl group of aliphatic and aromatic amino acids with blocked alpha amino groups. It is commonly used for its broad specificity. This enzyme belongs to Peptidase family S8 (subtilisin). The molecular weight of Proteinase K is 28,900 daltons (28.9 kDa). Enzyme activity Activated by calcium, the enzyme digests proteins preferentially after hydrophobic amino acids (aliphatic, aromatic and other hydrophobic amino acids). Although calcium ions do not affect the enzyme activity, they do contrib ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Ethanol Precipitation

Ethanol precipitation is a method used to purify and/or concentrate RNA, DNA, and polysaccharides such as pectin and xyloglucan from aqueous solutions by adding ethanol as an antisolvent. DNA precipitation Theory DNA is polar due to its highly charged phosphate backbone. Its polarity makes it water-soluble (water is polar) according to the principle "like dissolves like". Because of the high polarity of water, illustrated by its high dielectric constant of 80.1 (at 20 °C), electrostatic forces between charged particles are considerably lower in aqueous solution than they are in a vacuum or in air. This relation is reflected in Coulomb's law, which can be used to calculate the force acting on two charges q_1 and q_2 separated by a distance r by using the dielectric constant \varepsilon_r (also called relative static permittivity) of the medium in the denominator of the equation (\varepsilon_0 is an electric constant): F = \frac \frac At an atomic level, the reduction ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |