|

1960 U2 Incident

On 1 May 1960, a United States U-2 spy plane was shot down by the Soviet Air Defence Forces while conducting photographic aerial reconnaissance deep inside Soviet territory. The single-seat aircraft, flown by American pilot Francis Gary Powers, had taken off from Peshawar, Pakistan, and crashed near Sverdlovsk (present-day Yekaterinburg), after being hit by an S-75 Dvina (SA-2 Guideline) surface-to-air missile. Powers parachuted to the ground safely and was captured. Initially, American authorities acknowledged the incident as the loss of a civilian weather research aircraft operated by NASA, but were forced to admit the mission's true purpose a few days later after the Soviet government produced the captured pilot and parts of the U-2's surveillance equipment, including photographs of Soviet military bases. The incident occurred during the tenures of American president Dwight D. Eisenhower and Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, around two weeks before the scheduled opening ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because there was no large-scale fighting directly between the two superpowers, but they each supported major regional conflicts known as proxy wars. The conflict was based around the ideological and geopolitical struggle for global influence by these two superpowers, following their temporary alliance and victory against Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan in 1945. Aside from the nuclear arsenal development and conventional military deployment, the struggle for dominance was expressed via indirect means such as psychological warfare, propaganda campaigns, espionage, far-reaching embargoes, rivalry at sports events, and technological competitions such as the Space Race. The Western Bloc was led by the United States as well as a number of other First W ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Surface-to-air Missile

A surface-to-air missile (SAM), also known as a ground-to-air missile (GTAM) or surface-to-air guided weapon (SAGW), is a missile designed to be launched from the ground to destroy aircraft or other missiles. It is one type of anti-aircraft system; in modern armed forces, missiles have replaced most other forms of dedicated anti-aircraft weapons, with anti-aircraft guns pushed into specialized roles. The first attempt at SAM development took place during World War II, but no operational systems were introduced. Further development in the 1940s and 1950s led to operational systems being introduced by most major forces during the second half of the 1950s. Smaller systems, suitable for close-range work, evolved through the 1960s and 1970s, to modern systems that are man-portable. Shipborne systems followed the evolution of land-based models, starting with long-range weapons and steadily evolving toward smaller designs to provide a layered defence. This evolution of design increasin ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

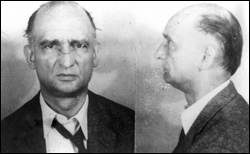

Rudolf Abel

Rudolf Ivanovich Abel (russian: Рудольф Иванович Абель), real name William August Fisher (11 July 1903 – 15 November 1971), was a Soviet intelligence officer. He adopted his alias when arrested on charges of conspiracy by the FBI in 1957. Fisher was born and grew up in Newcastle upon Tyne in the North of England in the United Kingdom to Russian émigré parents. He moved to Russia in the 1920s, and served in the Soviet military before undertaking foreign service as a radio operator in Soviet intelligence in the late 1920s and early 30s. He later served in an instructional role before taking part in intelligence operations against the Germans during World War II. After the war, he began working for the KGB, which sent him to the United States where he worked as part of a spy ring based in New York City. In 1957, the U.S. Federal Court in New York convicted Fisher on three counts of conspiracy as a Soviet spy for his involvement in what became known as the H ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Prisoner Exchange

A prisoner exchange or prisoner swap is a deal between opposing sides in a conflict to release prisoners: prisoners of war, spies, hostages, etc. Sometimes, dead bodies are involved in an exchange. Geneva Conventions Under the Geneva Conventions, prisoners who ''cannot'' contribute to the war effort because of illness or disability are entitled to be repatriated to their home country. That is regardless of number of prisoners so affected; the detaining power cannot refuse a genuine request. Under the Geneva Convention (1929), this is covered by Articles 68 to 74, and the annex. One of the largest exchange programmes was run by the International Red Cross during World War II under these terms. Under the Third Geneva Convention of 1949, that is covered by Articles 109 to 117. The Second World War in Yugoslavia saw a brutal struggle between the armed forces of the Third Reich and the communist-led Partisans. Despite that, the two sides negotiated prisoner exchanges virtually ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Forced Labor In The Soviet Union

Forced labor was used extensively in the Soviet Union as a means of controlling Soviet citizens and foreigners. Forced labor also provided manpower for government projects and for reconstruction after the war. It began before the Gulag and Kolkhoz systems were established, although through these institutions, its scope and severity were increased. The conditions that accompanied forced labor were often harsh and could be deadly. The following closely related categories of forced labor in the Soviet Union may be distinguished. Pre-Gulag Forced Labor of the Early Soviet Russia and Soviet Union On April 4, 1912, a strike formed by the laborers of the Lena Gold Field Company turned violent when an army detachment open-fired on the crowd. In the reports that followed, a muddled version of events, essentially assuming the army and officials were justified in their actions, left many with questions surrounding the circumstances in which the violence occurred. Labor conditions of the ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information (intelligence) from non-disclosed sources or divulging of the same without the permission of the holder of the information for a tangible benefit. A person who commits espionage is called an ''espionage agent'' or ''spy''. Any individual or spy ring (a cooperating group of spies), in the service of a government, company, criminal organization, or independent operation, can commit espionage. The practice is clandestine, as it is by definition unwelcome. In some circumstances, it may be a legal tool of law enforcement and in others, it may be illegal and punishable by law. Espionage is often part of an institutional effort by a government or commercial concern. However, the term tends to be associated with state spying on potential or actual enemies for military purposes. Spying involving corporations is known as industrial espionage. One of the most effective ways to gath ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Stanford University Press

Stanford University Press (SUP) is the publishing house of Stanford University. It is one of the oldest academic presses in the United States and the first university press to be established on the West Coast. It was among the presses officially admitted to the Association of American University Presses (now the Association of University Presses) at the organization's founding, in 1937, and is one of twenty-two current member presses from that original group. The press publishes 130 books per year across the humanities, social sciences, and business, and has more than 3,500 titles in print. History David Starr Jordan, the first president of Stanford University, posited four propositions to Leland and Jane Stanford when accepting the post, the last of which stipulated, “That provision be made for the publication of the results of any important research on the part of professors, or advanced students. Such papers may be issued from time to time as ‘Memoirs of the Leland Stanf ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Pakistani Government

The Government of Pakistan ( ur, , translit=hakúmat-e pákistán) abbreviated as GoP, is a federal government established by the Constitution of Pakistan as a constituted governing authority of the four provinces, two autonomous territories, and one federal territory of a parliamentary democratic republic, constitutionally called the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. Effecting the Westminster system for governing the state, the government is mainly composed of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches, in which all powers are vested by the Constitution in the Parliament, the Prime Minister and the Supreme Court. The powers and duties of these branches are further defined by acts and amendments of the Parliament, including the creation of executive institutions, departments and courts inferior to the Supreme Court. By constitutional powers, the President promulgates ordinances and passes bills. The President acts as the ceremonial figurehead while the people-elected Pr ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Camp David

Camp David is the country retreat for the president of the United States of America. It is located in the wooded hills of Catoctin Mountain Park, in Frederick County, Maryland, near the towns of Thurmont and Emmitsburg, about north-northwest of the national capital city of Washington, D.C.Frequently Asked Questions . Catoctin Mountain Park, Retrieved on February 4, 2011. "10. Where is Camp David? The Presidential Retreat is within the park however, it is not open to the public and its location is not shown on our park maps for both security and privacy. If you're interested in historical information, visit our Presidential Retreat webpage." It is officially known as the Naval Support Facility Thurmont. Because it is technic ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Since the 17th century, Paris has been one of the world's major centres of finance, diplomacy, commerce, fashion, gastronomy, and science. For its leading role in the arts and sciences, as well as its very early system of street lighting, in the 19th century it became known as "the City of Light". Like London, prior to the Second World War, it was also sometimes called the capital of the world. The City of Paris is the centre of the Île-de-France region, or Paris Region, with an estimated population of 12,262,544 in 2019, or about 19% of the population of France, making the region France's primate city. The Paris Region had a GDP of €739 billion ($743 billion) in 2019, which is the highest in Europe. According to the Economist Intelli ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev stunned the communist world with his denunciation of his predecessor Joseph Stalin's crimes, and embarked on a policy of de-Stalinization with his key ally Anastas Mikoyan. He sponsored the early Soviet space program, and enactment of moderate reforms in domestic policy. After some false starts, and a narrowly avoided nuclear war over Cuba, he conducted successful negotiations with the United States to reduce Cold War tensions. In 1964, the Kremlin leadership stripped him of power, replacing him with Leonid Brezhnev as First Secretary and Alexei Kosygin as Premier. Khrushchev was born in 1894 in a village in western Russia. He was employed as a metal worker during his youth, and he was a political commissar during the Russian Civil Wa ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Dwight D

Dwight may refer to: People * Dwight (given name) * Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890–1969), 34th president of the United States and former military officer *New England Dwight family of American educators, military and political leaders, and authors * Ed Dwight (born 1933), American test pilot, participated in astronaut training program * Mabel Dwight (1875–1955), American artist * Elton John (born Reginald Dwight in 1947), English singer, songwriter and musician Places Canada * Dwight, Ontario, village in the township of Lake of Bays, Ontario United States * Dwight (neighborhood), part of an historic district in New Haven, Connecticut * Dwight, Illinois, village in Livingston and Grundy counties * Dwight, Kansas, city in Morris County * Dwight, Michigan, an unincorporated community * Dwight, Nebraska, village in Butler County * Dwight, North Dakota, city in Richland County * Dwight Township, Livingston County, Illinois * Dwight Township, Michigan Institutions * Dwight Correctional ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

.png)